Abstract

Background

The anthropogenic increase of atmospheric CO2 concentration (ca) is impacting carbon (C), water, and nitrogen (N) cycles in grassland and other terrestrial biomes. Plant canopy stomatal conductance is a key player in these coupled cycles: it is a physiological control of vegetation water use efficiency (the ratio of C gain by photosynthesis to water loss by transpiration), and it responds to photosynthetic activity, which is influenced by vegetation N status. It is unknown if the ca-increase and climate change over the last century have already affected canopy stomatal conductance and its links with C and N processes in grassland.

Results

Here, we assessed two independent proxies of (growing season-integrating canopy-scale) stomatal conductance changes over the last century: trends of δ18O in cellulose (δ18Ocellulose) in archived herbage from a wide range of grassland communities on the Park Grass Experiment at Rothamsted (U.K.) and changes of the ratio of yields to the CO2 concentration gradient between the atmosphere and the leaf internal gas space (ca – ci). The two proxies correlated closely (R2 = 0.70), in agreement with the hypothesis. In addition, the sensitivity of δ18Ocellulose changes to estimated stomatal conductance changes agreed broadly with published sensitivities across a range of contemporary field and controlled environment studies, further supporting the utility of δ18Ocellulose changes for historical reconstruction of stomatal conductance changes at Park Grass. Trends of δ18Ocellulose differed strongly between plots and indicated much greater reductions of stomatal conductance in grass-rich than dicot-rich communities. Reductions of stomatal conductance were connected with reductions of yield trends, nitrogen acquisition, and nitrogen nutrition index. Although all plots were nitrogen-limited or phosphorus- and nitrogen-co-limited to different degrees, long-term reductions of stomatal conductance were largely independent of fertilizer regimes and soil pH, except for nitrogen fertilizer supply which promoted the abundance of grasses.

Conclusions

Our data indicate that some types of temperate grassland may have attained saturation of C sink activity more than one century ago. Increasing N fertilizer supply may not be an effective climate change mitigation strategy in many grasslands, as it promotes the expansion of grasses at the disadvantage of the more CO2 responsive forbs and N-fixing legumes.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12915-021-00988-4.

Keywords: 13C discrimination, Grassland, Hay yield, Last-century climate change, N and P nutrition status, Oxygen isotope composition of cellulose, Park Grass Experiment, Plant functional groups, Stomatal conductance, Water use efficiency

Background

Atmospheric CO2 increase and related climate change are altering fundamentally the terrestrial biogeochemical cycles of carbon (C), water, and nitrogen (N) across grasslands, forests, and croplands [1–5]. At local scales, these cycles are linked by processes at plant surfaces of leaves [6–12] and roots [3, 13, 14], critical interfaces in the soil-plant-atmosphere continuum. The uptake of CO2 by photosynthesis and evaporative loss of water vapor in transpiration occur through the same path, the stomata [8]. These small pores in the leaf epidermis adjust their conductance in response to environmental conditions [9, 10], such as atmospheric CO2 concentration (ca) [7, 11], and internal cues that include photosynthetic activity [7, 15–17] which correlates with leaf nitrogen status [7, 15, 16, 18]. When stomata open for CO2 uptake, they simultaneously expose the leaf internal moisture to a comparatively dry atmosphere. This leaf-to-air vapor pressure gradient drives transpiration [10]. The ratio of canopy-scale photosynthesis (A) and transpiration (E) determines vegetation water use efficiency (W) (Eq. 1) [12, 19]. The control function of stomatal conductance, and its implication for changes of water use efficiency (W) in the face of increasing ca, becomes evident when A and E are expressed as the products of stomatal conductance (gs) and the concentration gradients of the respective gases [12, 19]:

| 1 |

where ca and va are the CO2 and water vapor mole fractions in air, ci and vi that in the substomatal cavity, and 1.6 is the ratio of the diffusivities of CO2 and water vapor in air. If transpiration is altered by a change of stomatal conductance, the resulting change of the advective flux of soil water to roots may modify mass flow-dependent nutrient uptake [13, 14]. Such a change may alter the nitrogen nutrition status of vegetation [20]. Also, reduced transpiration has been identified as one of the controls limiting N acquisition in elevated CO2 studies in the field [3]. Understanding relationships between stomatal conductance, photosynthesis, transpiration and N acquisition are fundamental for explaining why for some temperate humid grasslands the CO2 fertilization responses in aboveground biomass production have been small or absent [4, 21]. That such interactions may have already operated in the last century is indicated by an investigation of herbage yields in 1891–1992 on several unlimed plots of the Park Grass Continuous Hay Experiment (Rothamsted, U.K.), which found no significant trend [22], although water use efficiency has increased [23]. It has been hypothesized from elevated CO2 studies in the field that the limited fertilization effect of elevated ca in temperate grassland communities is connected with stronger reduction of stomatal conductance in the grasses, and greater photosynthetic acclimation, in comparison with forbs and legumes, or by nutrient limitation, especially for N [4, 7, 21]. Here, we examine evidence from the Park Grass Experiment to see in how far these mechanisms have already operated to shape grassland communities’ responses to the increase of ca and associated climate change in the last century.

The Park Grass Experiment [24] (hereafter referred to as Park Grass) is the oldest permanent grassland experiment in the world. As a field resource, it enables not only exploration of the relationships between grassland community composition, nutrient status, and herbage yields, but also canopy stomatal conductance, water use efficiency, and N acquisition by ways of elemental and isotopic analysis of samples stored in the Rothamsted Sample Archive (the “Methods” section). In this analysis, we also expand on the temporal scope of earlier studies on yield trends [22] and intrinsic water use efficiency [23], by investigating changes during the last 100 years by using two periods in the early twentieth (1917–1931) and twenty-first century (2004–2018), each of 15 years. Over that time span (1917 to 2018), atmospheric CO2 concentration (ca) increased by c. 30% or 100 μmol mol−1 [25, 26].

Results and discussion

Between periods, daily mean temperature increased by c. 1.5 °C at Rothamsted, but atmospheric vapor pressure deficit and rainfall during the main spring growth period (1 April to 30 June) did not change significantly (Additional file 1: Fig. S1).

We analyzed hay samples (the “Methods” section) from selected plots that had received different annual fertilizer treatments (n = 12) for over a century, starting in 1856. Treatments included limed and unlimed “control” plots given no fertilizer and plots receiving nitrate- or ammonia-nitrogen (N) at different rates amended with or without lime plus phosphorus and potassium (PK) fertilizer. These treatments have caused a great diversity of plant species richness [24, 27] (2–43 species) in associated grass- (80–100% grass biomass, n = 6 treatments) and dicot-rich communities (32–52% dicots, with 2–25% legumes, n = 6), and variable total herbage yields [22, 27] (100–560 g dry biomass m−2 year−1) in the 1st annual yield cut taken around mid-June each year (Table 1). High yields (yields > 80% of the highest yielding treatment) were obtained over the full range of N fertilizer application (0–14.4 g N m−2 year−1) in the limed treatments, providing that plots also received P and K fertilizers (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Summary characteristics of selected treatments from the Park Grass Experiment

| Treatment | Plot No. (subplot) | P/K input (g m−2 year−1) | N input (g m−2 year−1) | Functional group composition (%-G/%-F/%-L) | Species richness | pH | Total herbage yield (g m−2) | NNI | PNI | N to P | Nutrient limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No nitrogen | |||||||||||

| CONTROL.L | 2/2(a), 3(a) | 0/0 | 0 | Dicot-rich (48/40/12) | 43 | 7.2 | 224 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 11.3 | Co-limitation |

| CONTROL.U | 3(d) | 0/0 | 0 | Dicot-rich (63/33/4) | 41 | 5.2 | 149 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 12.9 | Co-limitation |

| PK.L | 7/2(a) | 3.5/22.5 | 0 | Dicot-rich (54/21/25) | 29 | 6.8 | 501 | 0.5 | 1.2 | 4.9 | N-limitation |

| Sodium nitrate | |||||||||||

| N*1.L | 17(a) | 0/0 | 4.8 | Dicot-rich (62/36/2) | 36 | 7.1 | 244 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 14.9 | Co-limitation |

| N*1PK.L | 16(a) | 3.5/22.5 | 4.8 | Dicot-rich (68/20/12) | 26 | 6.7 | 496 | 0.5 | 1.2 | 4.8 | N-limitation |

| N*2.PK.L | 14/2(a) | 3.5/22.5 | 9.6 | Grass-rich (80/17/3) | 31 | 6.9 | 487 | 0.5 | 1.2 | 5.2 | Co-limitation |

| Ammonium sulfate | |||||||||||

| N1.L | 1(b) | 0/0 | 4.8 | Dicot-rich (66/33/1) | 30 | 6.2 | 208 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 15.6 | Co-limitation |

| N1.U | 1(d) | 0/0 | 4.8 | Grass-rich (97/3/0) | 6 | 4.1 | 100 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 20.1 | Co-limitation |

| N2PK.L | 9/2(b) | 3.5/22.5 | 9.6 | Grass-rich (90/7/3) | 19 | 6.3 | 545 | 0.5 | 1.1 | 5.3 | N-limitation |

| N2PK.U | 9/2(d) | 3.5/22.5 | 9.6 | Grass-rich (99/1/0) | 5 | 3.7 | 355 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 7.9 | N-limitation |

| N3PK.L | 11/1(b) | 3.5/22.5 | 14.4 | Grass-rich (91/9/0) | 16 | 6.2 | 560 | 0.6 | 1.1 | 6.0 | N-limitation |

| N3PK.U | 11/1(d) | 3.5/22.5 | 14.4 | Grass-rich (100/0/0) | 2 | 3.6 | 374 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 9.9 | Co-limitation |

Lime application is represented with the letters “L” (limed) or “U” (unlimed) in the treatment name. Ground chalk was applied as necessary to maintain soil at pH 7 or 6 on sub-plots “a” and “b”, respectively; P amount applied to the plots was decreased from 3.5 to 1.7 g P m−2 year−1 since 2017; functional group composition was estimated from botanical separation data between 1915 and 1976, 1991 and 2000, and 2010 and 2012 (e-RA); species richness data report on a 10-year period from 1991 to 2000; total herbage yields and nitrogen nutrition index (NNI) data are given for the last 15 years of the study (2004–2018); phosphorus nutrition index (PNI) and N to P ratios are presented for a 10-year period (2000–2009); soil pH corresponds to samples taken in 1995; NNI was calculated as in Lemaire et al. [28], with parameters for C3 temperate grassland if yield > 100 g m−2 and Ncrit = 4.8%-N in dry matter if yield < 100 g m−2. PNI was calculated according to Liebisch et al. [29]. Nutrient limitation was defined based on N to P ratios according to Güsewell [30], with N to P ratios < 10 and > 20 corresponding to N- and P-limitation and N to P ratios between 10 and 20 indicating N and P co-limitation

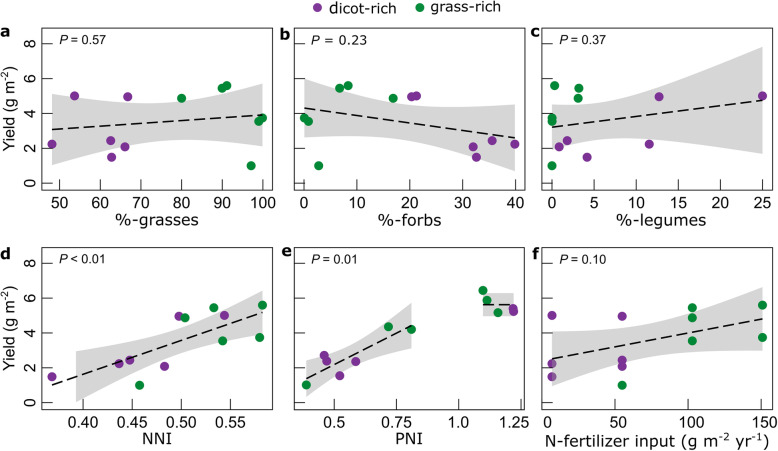

Fig. 1.

Relationship between yield and botanical traits and nutrition. Total herbage yield as a function of the percentage of grasses (a), percentage of forbs (b) percentage of legumes (c), nitrogen nutrition index (NNI) (d), phosphorus nutrition index (PNI) (e), and N fertilizer input (f). Values present the 15-year averages (2004–2018) of individual treatments, except for PNI, which was determined for samples collected between 2000 and 2009. The continuous lines and the shaded areas indicate the regression line for the relationship ± CI95%. The PNI linear regression was calculated for values < 1 only, as yields for PNI values > 1 are assumed independent of phosphorus nutrition status

We determined intrinsic water use efficiency (Wi), the physiological, i.e., non-climatic component of water use efficiency, that accounts separately for atmospheric water demand (va – vi) [12, 19]:

| 2 |

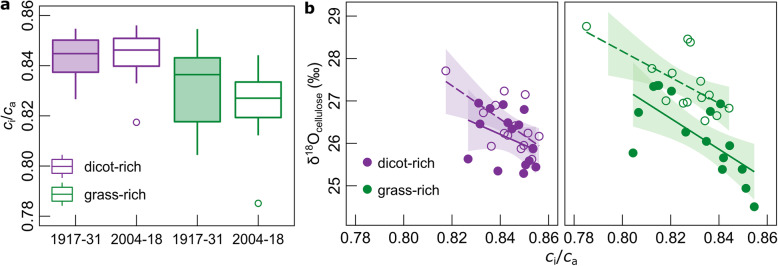

ci/ca was determined from 13C discrimination (the “Methods” section), in accounting for effects of mesophyll conductance and photorespiration [31], factors that were not previously considered [23]. Equations 1 and 2 show that water use efficiency depends principally on photosynthesis and stomatal conductance, if atmospheric water demand is constant, as was approximately the case at Park Grass (Additional file 1: Fig. S1). Additionally, water use efficiency increases in proportion to ca if 1 − ci/ca, the relative CO2 concentration gradient between the atmosphere and the leaf intercellular space, does not vary. Our results demonstrated that ci/ca did not change significantly between the start and the end of the century in the dicot-rich communities, but decreased by 0.01 in grass-rich communities (P < 0.01). Besides, ci/ca was slightly higher (and varied less within periods) in dicot-rich relative to grass-rich treatments, both at the beginning (+ 0.01, P < 0.001) and at the end of the century (+ 0.02, P < 0.001) (Fig. 2). The modest observed variation of ci/ca across the century agrees with other 13C-based observations over geological timescales with greatly varying ca [11] and with plant responses from seasonal- to century-scale changes of climatic, edaphic, and nutritional stresses in forests and grasslands, including at Park Grass [5, 23, 32]. Modest variation of ci/ca is an expected result of coordinated reciprocal adjustments of photosynthesis and stomatal conductance that serve to optimize photosynthetic C gain relative to water loss by transpiration [5, 12, 18, 33]. On average, intrinsic water use efficiency at Park Grass increased by + 9.6 μmol mol−1 or c. 31% compared to the beginning of the century (Fig. 3a, P < 0.001), mainly due to the increase of ca. However, the increase of intrinsic water use efficiency was c. 33% greater in the grass-rich swards than dicot-rich plant communities, due to the small decrease of ci/ca.

Fig. 2.

ci/ca variation during the last century. ci/ca variation for 15-year periods at the beginning (1917–1931) and the end (2004–2018) of the last century (a) and its relationship with δ18Ocellulose variation (b). ci/ca, the ratio of substomatal to atmospheric CO2 concentration, was calculated from the C isotope composition of hay samples using the model of Ma et al. [28] (the “Methods” section). Values represent the yearly averages of samples during the two periods of analysis (1917–1931, filled symbols; 2004–2018, empty symbols). The lines in b (1917–1931, continuous line; 2004–2018, dashed line) and the shaded areas indicate the regression line for the relationship ± CI95%

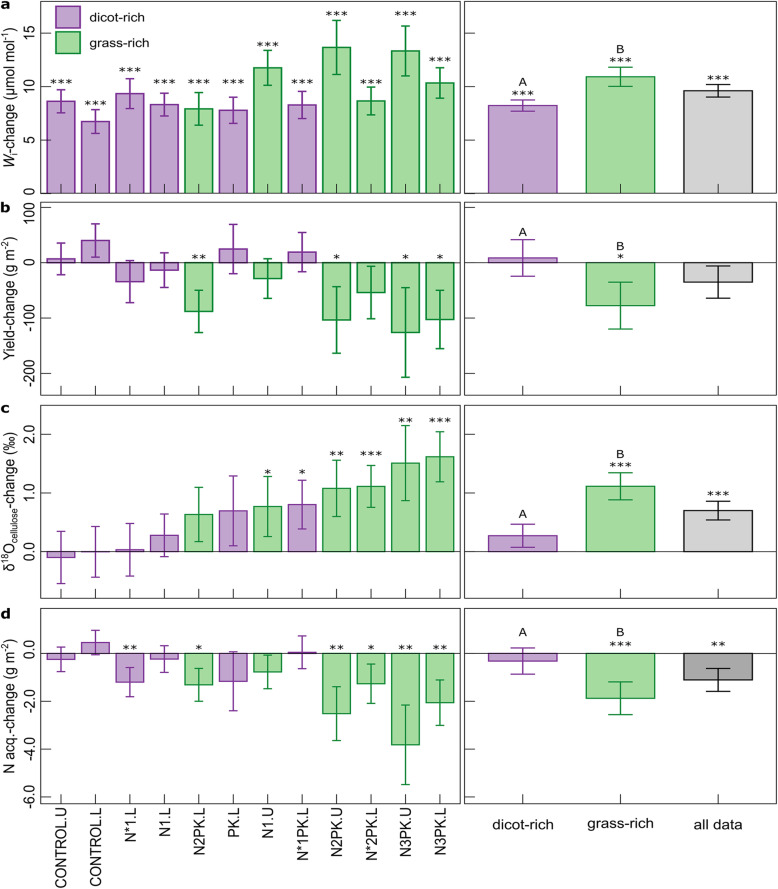

Fig. 3.

Long-term changes in physiological parameters at the Park Grass Experiment. Intrinsic water-use efficiency-change (Wi-change) (a), hay yield-change (b), δ18Ocellulose-change (c), and nitrogen acquisition-change (d) during the last century. Changes were calculated as the difference between period 2 (2004–2018) and period 1 (1917–1931). Results are presented for each fertilizer treatment (in the order of the treatment effect on the long-term δ18Ocellulose-change), the mean of all dicot-rich and grass-rich treatments, and all treatments combined. Bar plots and error bars represent the calculated difference ± SE (SE calculated as SE from period 1 + SE from period 2; n = 11–15 in each period for each treatment depending on data availability; see Additional file 1: Table S1 for details). t tests were used for determining if the long-term changes were statistically significant and significance is presented when P < 0.05. Significance levels: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. Significant differences between grass-rich and dicot-rich treatments are designated with different capital letters

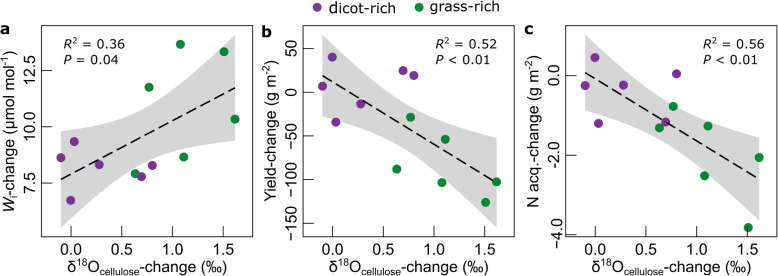

Yield trends over the century diverged for the dicot- and grass-rich treatments (Fig. 3b, P < 0.001). While the yields of the grass-rich treatments decreased by 16% on average, yield trends of the dicot-rich plots and the average of all plots were not significant, aligning with the previous observation that annual yields of the Park Grass plots have not increased systematically in the twentieth century [22]. Changes of yield (Y) are linked to changes of growing season-integrated water use efficiency via canopy photosynthesis as Y = A (1 –ϕ) (1 – r) [19], with ϕ the proportion of carbon respired and r that allocated to roots and non-harvested or senesced shoot biomass. Growing season-integrated canopy photosynthesis of the different treatments may have changed over the century in response to rising ca, warming (and associated earlier spring growth) and precipitation patterns and weather dynamics in intricate but unknown ways. Also, there is some uncertainty about long-term and treatment effects on ϕ and r (but see the “Methods” section). Interestingly, however, yield trends were closely negatively related to intrinsic water use efficiency (R2 = 0.53; P < 0.01). That negative relationship points to stomatal conductance (integrated over the growing season and canopy) as the likely primary control of treatment-dependent yield trends in the last century.

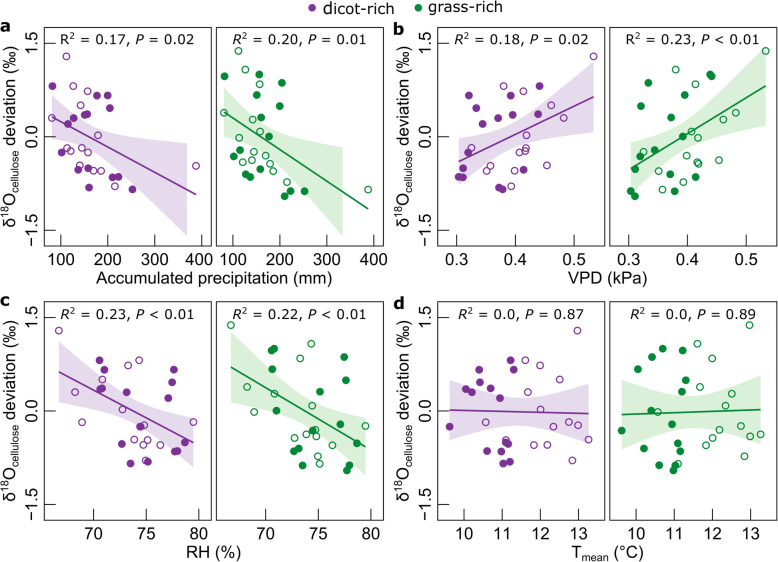

Indeed, treatment effects on yield trends also correlated negatively with trends of δ18O of cellulose (δ18Ocellulose, the “Methods” section) (Fig. 4b, R2 = 0.52, P < 0.01). Increases of δ18Ocellulose in plant biomass are indicative of decreases of stomatal conductance, under otherwise equal environmental conditions [34, 35], including rainfall, atmospheric humidity, soil conditions affecting plant-water relations, and isotopic inputs of rain (δ18Orain) and atmospheric moisture (δ18Ovapour) (the “Methods” section). Climate warming should increase δ18Orain [36] and has caused an increase of vapor pressure deficit in Europe, which contributes to reduce stomatal conductance [37]. Yet, vapor pressure deficit and rainfall during spring growth have not changed significantly at Park Grass. Secondly, measurements at a 55 km-distant station (Wallingford) and predictions from global circulation models provide no indication for significant trends of annual δ18Orain (Additional file 1: Fig. S2). And thirdly, the long-term trends of δ18Ocellulose were independent of interannual variations of meteorological variables (such as vapor pressure deficit), which were very similar at the beginning of the 20th and the twenty-first century (Fig. 5). Most importantly, the century-scale divergence of δ18Ocellulose between treatments was not attributable to eventual changes of δ18Orain or environmental conditions, as all treatments experienced the same site and weather conditions.

Fig. 4.

Physiological correlates of long-term δ18Ocellulose-change: relationship between long-term change in δ18Ocellulose and change in intrinsic water use efficiency (Wi) (a), hay yield (b), and nitrogen acquisition (c), for individual treatments. Long-term changes were calculated as in Fig. 3. The dashed lines and the shaded areas represent the regression line ± CI95%

Fig. 5.

Effect of spring meteorology on δ18Ocellulose. Relationship between δ18Ocellulose deviation from period mean and accumulated annual precipitation (a), average vapor pressure deficit (VPD) (b), average relative humidity (RH) (c), and average temperature (d) during the spring growing period (1 April to 30 June). δ18Ocellulose deviation values represent the difference between yearly averages of all samples from grass-rich or dicot-rich treatments and their respective 15-year averages during period 1 (1917–1931, filled circles) and period 2 (2004–2018, empty circles). The continuous lines and the shadowed areas indicate the regression line for the relationship ± CI95%

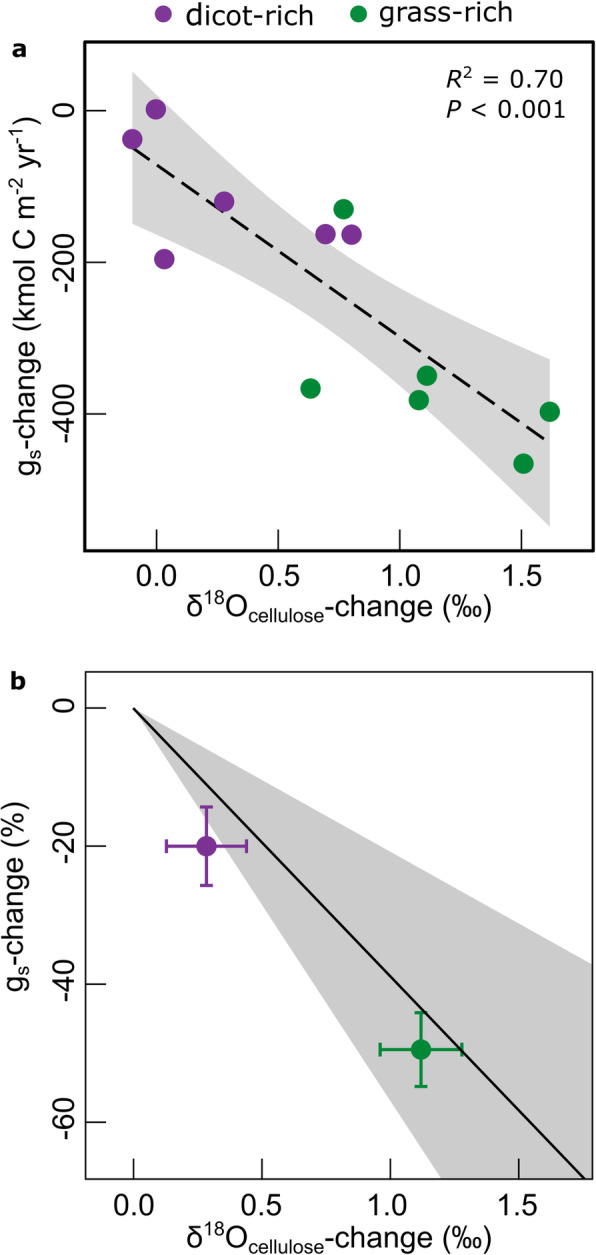

On average of all treatments, δ18Ocellulose increased over the century (Fig. 3c, average + 0.7‰, P < 0.001), consistent with a general long-term decrease of stomatal conductance. The increase of δ18Ocellulose was much stronger in grass-rich (+ 1.1‰; P < 0.001) than dicot-rich (+ 0.3‰; P = 0.06) plots. The trends of δ18Ocellulose were closely proportional (R2 = 0.70; P < 0.001) to trends in the ratio of hay yield to the CO2 concentration gradient between the atmosphere and the leaf internal gas space, ca – ci (Fig. 6a), another proxy of stomatal conductance integrated over the growing season and canopy (the “Methods” section). The proportionality indicated that a long-term change in δ18Ocellulose only occurred when stomatal conductance changed. Additionally, the sensitivity of δ18Ocellulose changes to changes of stomatal conductance estimated for Park Grass agreed with sensitivities observed by others (the “Methods” section) in leaf- or canopy-scale stomatal conductance studies with a range of plant species or genotypes in different environmental conditions (Fig. 6b), instilling further confidence in δ18Ocellulose change as a well-grounded measure of long-term canopy-scale stomatal conductance variation at the Park Grass site in the past century. It is also notable in that context, that interannual variation of δ18Ocellulose correlated negatively with ci/ca, both at the beginning and end of the century (P < 0.001), with greater ranges of variation in grass-rich than dicot-rich plots (Fig. 2b). This relationship also points to stomatal conductance-variation as an important cause for interannual variation of intrinsic WUE at Park Grass, particularly in the grass-rich plots.

Fig. 6.

Sensitivity of stomatal conductance (gs) to δ18Ocellulose. Relationship between the long-term change in δ18Ocellulose and the long-term change in stand-scale, growing season-integrated stomatal conductance, estimated as the ratio of C-yield of hay to the CO2 concentration gradient between the atmosphere and the leaf internal gas space (the “Methods” section) of individual treatments (a), and relationship between relative stomatal conductance change (in % gs change) and δ18O-increase (in permil) at the Park Grass Experiment for dicot-rich (n = 6) or grass-rich (n = 6) treatments (mean ± SE) compared to reports of δ18Ocellulose change versus leaf- or canopy-scale stomatal conductance change over a range of plant species or genotypes in different environmental conditions (see Additional file 1: Table S2 for details on reported studies) (b). The dashed line and the shaded area in a represent the regression line ± CI95%, while the continuous black line and the shaded area in b represent the mean sensitivity ± CI95% calculated from the reported studies

Negative yield trends in grass-rich communities over the century were connected with decreased net rates of N acquisition (Fig. 3d, − 1.9 g N m−2 year−1, P < 0.001). Similar decreases of N acquisition were generally not observed in dicot-rich treatments (− 0.3 g m−2 year−1, P = 0.4), that received little or no N fertilizer. These observations match observations in elevated CO2 studies, which found consistently decreased rates of N acquisition in grassland, forests and crops under conditions where elevated CO2 failed to enhance yields [3]. The Park Grass data indicate that such ca- and climate change-induced reductions of N acquisition may have occurred mainly in grass-rich grassland communities in the last century. At Park Grass, these decreases in N acquisition were closely correlated with increases of δ18Ocellulose (Fig. 4c, R2 = 0.56; P < 0.01), in agreement with stomatal conductance-mediated reductions of transpiration and associated mass flow-dependent N acquisition [3, 13, 14]. Absence of significant reductions of N acquisition in the non-N-fertilized (dicot-rich) communities agrees with much smaller (if any) reductions of stomatal conductance, but may also be influenced by the fact that N acquisition in N-poor soils is more closely controlled by diffusion [14], and atmospheric deposition of N and biological N fixation account for a larger proportion of total N acquisition in these plots on average [24]. But, regardless of the mechanism underlying the reduced N acquisition [3] in grass-rich plots, any impairment of N status would reduce photosynthetic capacity and feedback on stomatal conductance to adjust ci/ca for optimization of C gain per unit water loss by transpiration [6, 7, 10, 15, 16, 18].

N fertilizer addition was the strongest experimental determinant of grass dominance at Park Grass (P < 0.001). Meanwhile, PK fertilization had a much greater effect on yields, although all plots remained N limited or N and P co-limited (Table 1). N limitation [2, 20, 28] is a well-known factor limiting the CO2 fertilizer effect in grassland [4, 21]. During the century, the reduction of N acquisition aggravated the N limitation of the grass-rich communities, as evidenced by a decreasing nitrogen nutrition index [28] (− 0.08, P < 0.001). Conversely, the nitrogen nutrition index decreased much less in the dicot-rich communities (− 0.04, P = 0.01). That difference must have contributed to the convergence of yields of grass- and dicot-rich plots over the century. For example, among the high-yielding, limed and PK-fertilized plots, the dicot-rich, non-N-fertilized plot yielded 22% less than its grass-rich, N-fertilized counterparts at the beginning of the twentieth century, but only 6% less at the end of the twenty-first century. Thus, the yield enhancement generated by N fertilizer addition decreased by 78% over the century. At the same time, the apparent efficiency of N fertilizer uptake (net N acquisition per unit of added N fertilizer) decreased by 16% in the grass-rich (P < 0.001) but not in the dicot-rich communities (P = 0.2). Although the cutting frequency (two cuts per year) at Park Grass does not represent a very intensive utilization practice, the decreasing N fertilizer uptake efficiency of grass-rich communities does raise questions concerning the fate of N in the ecosystem and the future sustainability of high inputs of N fertilizer in such grasslands [38]. Much of the Western European grassland receives very high N inputs [39].

Conclusions

The present work provides evidence for an interaction between plant functional groups and the ca- and related climate change-response of temperate-humid permanent grassland in the last century, managed under a hay-cutting regime with a range of fertilizer inputs. While part of that evidence is correlative, its interpretation is underpinned by empirical knowledge and mechanistic understanding obtained in more controlled experimental conditions, although these were mainly concerned with the effects of future elevated CO2 and changed climate [3, 6, 7, 21]. The observed interactions between plant functional group composition and climate change responses in the last century appeared to be associated primarily with the much greater ca-sensitivity of grasses in terms of their stomatal conductance compared with that of forbs and legumes, resulting in effects on grassland vegetation water use efficiency [23], N acquisition and aboveground biomass production, central features of the role of vegetation in biogeochemical cycles and feedbacks to the climate system. Our work also shows that key predictions drawn from free-air CO2 enrichment experiments concerning ca-saturation of the CO2 fertilizer effect on aboveground biomass production [4, 6, 21], N acquisition [3] and the lesser competitive ability of grasses relative to forbs and legumes [6, 21] have already taken hold in some temperate grasslands in the last century or before.

Methods

The Park Grass Experiment

The Park Grass Experiment (hereafter referred to as Park Grass), located at the Rothamsted Research Station in Hertfordshire, U.K., approx. 40 km north of London (0°22′ West, 51°48′ North), is the oldest grassland experiment in the world. It was started in 1856 on c. 2.8 ha of old grassland, and its original purpose was to investigate the effect of fertilizers and organic manures on hay yields of permanent grassland [40]. The experiment comprises 20 main plots with different fertilizer inputs; most plots have been divided into subplots “a”–“d” and receive different lime inputs. Since the beginning of the experiment, herbage has been cut in mid-June and made into hay (first cut). Herbage regrowth of the sward was grazed by sheep during the first 15 years, but in each year since 1875, a second cut has been taken and removed from the plot. Originally, total herbage yields were determined in situ by weighing the dried material (hay) for whole plots. Since 1960, one or two sample strips, depending on the plot size, were cut on each plot using a forage harvester. The fresh material was weighed and yields were calculated after drying. Since 1856, representative hay samples from each harvest have been stored in the Rothamsted Sample Archive [41].

For this study, we used dried hay or herbage samples from the first cut (spring growth) of 13 plots (12 different treatments), with contrasting fertilizer and lime inputs (Table 1). The treatments included four nitrogen levels (0, 4.8, 9.6, and 14.4 g N m−2 year−1, with nitrogen added either as ammonium sulfate or sodium nitrate), lime application (chalk applied as necessary to maintain soil at pH 7, 6, and 5 on sub-plots “a,” “b,” and “c”), one sodium/potassium level (3.5 g P m−2 year−1 as triple superphosphate and 22.5 g K m−2 year−1 as potassium sulfate; P was applied at 1.7 g m−2 year−1 since 2017), and the control plots (no fertilizer application). The plots that received P and K also received 1.5 g Na m−2 year−1 as sodium sulfate and 1 g Mg m−2 year−1 as magnesium sulfate. N was applied in spring and P and K in autumn.

Functional group composition

Plant functional group (PFG) composition was strongly altered by fertilization and lime inputs on Park Grass. The original vegetation was classified post-hoc as dicotyledon-rich Cynosurus cristatus-Centaurea nigra grassland [42], but it changed rapidly following the introduction of the different treatments, creating very contrasting community compositions, which have reached a dynamic equilibrium since 1910 [41]. We consider the functional group composition (%-grasses, %-forbs and %-legumes in standing dry biomass) of each treatment to have remained relatively constant during the past 100 years. The average functional group composition was calculated from individual datasets sampled between 1915 and 1976, 1991 and 2000, and 2010 and 2012 (e-RA, http://www.era.rothamsted.ac.uk/). Given the high but variable proportion of grasses (48–100% of standing dry biomass, depending on treatment), we used this characteristic to represent the functional composition heterogeneity among treatments. Treatments with a grass proportion > 80% were termed grass-rich, and the other treatments (grass proportion 50–68%) dicot-rich (Table 1).

Sample preparation and analysis

Representative subsamples (2–3 g) of plant material from the first cut were taken from the Rothamsted sample archive. Two 15-year periods were selected, corresponding to the beginning (1917–1931, period 1) and the end (2004–2018, period 2) of the last 100 years. The period length was selected to account for the interannual variability in δ18O of α-cellulose (δ18Ocellulose), which is associated with interannual variation of meteorological conditions (see the “Stomatal conductance” section and Fig. 5). The subsamples were used to determine the δ13C of bulk plant material (δ13Cp) and δ18Ocellulose. Carbon and oxygen isotope composition were expressed as:

| 3 |

with Rsample the 13C/12C (or 18O/16O) ratio of the sample and Rstandard that in the international standard (Vienna Pee Dee Belemnite, V-PDB for carbon or Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water, V-SMOW for oxygen isotope ratio).

α-cellulose was extracted from 50 mg of dry sample material by following the Brendel et al. [43] protocol as modified by Gaudinski et al. [44]. The extracted cellulose was re-dried at 40 °C for 24 h; 0.7 ± 0.05 mg aliquots were weighed into silver cups (size 3.3 × 5 mm, IVA Analysentechnik e.K., Meerbusch, Germany) and stored in an exsiccator vessel containing Silica Gel Orange (ThoMar OHG, Lütau, Germany) prior to analysis. Samples were pyrolyzed at 1400 °C in a pyrolysis oven (HTO, HEKAtech, Wegberg, Germany), equipped with a helium-flushed zero blank auto-sampler (Costech Analytical technologies, Valencia, CA, USA) and connected via an interface (ConFlo III, Finnigan MAT, Bremen, Germany) with a continuous-flow isotope ratio mass spectrometer (Delta Plus, Finnigan MAT). Solid internal laboratory standards (SILS, cotton powder) were run each time after the measurement of four samples. Both cellulose samples and SILS were measured against a laboratory working standard carbon monoxide gas, previously calibrated against a secondary isotope standard (IAEA-601, accuracy of calibration ± 0.25‰ SD). The precision for the laboratory standard was < 0.3‰ (SD for repeated measurements).

For measurement of δ13Cp, the plant material was dried at 40 °C for 48 h, ball milled to a fine powder, re-dried during 24 h at 60 °C, and aliquots of 0.7 ± 0.05 weighed into tin cups (size 3.3 × 5 mm, LüdiSwiss, Flawil, Switzerland). Samples were combusted in an elemental analyzer (NA 1110; Carlo Erba, Milan, Italy) interfaced (Conflo III; Finnigan MAT, Bremen, Germany) with an isotope ratio mass spectrometer (Delta Plus; Finnigan MAT) and measured against a laboratory working standard CO2 gas, previously calibrated against a secondary isotope standard (IAEA-CH6 for δ13C, accuracy of calibration 0.06% SD). As a control, SILS which were previously calibrated against the secondary standard and had a similar C/N ratio as the samples (a fine wheat flour) were run after every tenth sample. The long-term precision for the SILS was < 0.2‰. C and N elemental concentration (%C and %N in dry biomass) were also measured in the same sequence. Additionally, P elemental concentration (%P in dry biomass) was determined on 20–25 mg of dry sample material for a 10-year period (2000–2009) using a modified phosphovanado-molybdate colorimetric method following acid digestion [45].

Meteorological and yield data

Meteorology and yield datasets were obtained from the electronic Rothamsted Archive (e-RA, http://www.era.rothamsted.ac.uk/). Rainfall data have been collected continuously since 1853 at the Rothamsted Weather Station, temperature since 1873 and additional meteorological variables have been added gradually. We calculated a yearly spring value for the last 100 years (1917–2018) by averaging all daily values between 1 April and 30 June for the following meteorological variables: maximum air temperature (Tmax, °C), average air temperature (Tmean, °C), average relative humidity of air (RH, %), and average vapor pressure deficit (VPD, kPa). In the case of precipitation (rain, mm), we used the cumulative rain amount for the same period. Yearly spring values were used for the analysis of long-term climatic changes.

Total herbage yield data from the first cut between 1917 and 2018 (expressed in g dry biomass m−2 year−1) were used to determine long-term yield trends during spring growth and for the calculation of (1) the yearly nitrogen acquisition (N acquisition, g m−2 year−1), calculated as dry matter yield × N content of dry biomass, and (2) a yield-weighted canopy stomatal conductance (see the “Stomatal conductance” section), for each of the 12 selected treatments. Given the change in the harvest method since 1960 [22, 46], we calculated an offset-correction for yield estimates pre-1960 to permit estimation of yield changes over the century on the same methodological basis. The offset-correction was based on the relationship between atmospheric CO2 concentration (as a long-term proxy for climate change) and measured yields from 1917 to 2018. For this, we fitted the following multiple linear regression to the data of every treatment:

| 4 |

with Y denoting measured yield, β and γ the coefficients to be determined, period a dummy variable coded with 0 for yields before 1960 and 1 for yields after 1960 and ε the random error. The treatment-specific estimated γ parameter was used as the offset-correction for spring yield determinations before 1960 (Additional file 1: Fig. S3 and Table S3).

Intrinsic water use efficiency

Intrinsic water use efficiency (Wi) is a physiological efficiency [47] that represents the ratio of net photosynthesis rate (A) and stomatal conductance to water vapor (gw):

| 5 |

That relationship is controlled by the CO2 concentration gradient between the atmosphere (ca) and the leaf internal gas space (ci), ca - ci, and the ratio of the diffusivities of water vapor and CO2 (1.6) [19, 47]. The CO2 concentration gradient can also be expressed as the product of ca and the relative CO2 concentration gradient between the atmosphere and the leaf internal gas space (1 – ci/ca) (Eq. 5). Thus, solving the equation required two parameters, ca, known from measurements of free air and air bubbles separated from ice cores [25], and ci/ca, that we estimated according to Ma et al. [31] (the bracketed term in Eq. 5). In that term, a is the 13C discrimination during diffusion of CO2 in air through the stomatal pore (4.4‰), am (1.8‰) the fractionation associated with CO2 dissolution and diffusion in the mesophyll, and b (29‰) and f (11‰) the fractionations due to carboxylation and photorespiration, respectively; Г* is the CO2 compensation point in the absence of mitochondrial respiration calculated following Brooks and Farquhar [48], and gs/gm the ratio of stomatal and mesophyll conductance [31]. Relying on theory developed by Farquhar et al. [49] and Farquhar and Richards [19], this model accounts for the effects of mesophyll conductance and photorespiration on Δ13C-based estimations of intrinsic water use efficiency. Traditionally, estimations of Wi from Δ13C have used a more abbreviated version of the Farquhar model of photosynthetic carbon isotope discrimination (Δ13C) in C3 plants. That version neglected the photorespiration term and was based on the simplifying assumption that mesophyll conductance is infinite. However, Wi estimated from Δ13C using the abbreviated model systematically overestimates gas exchange-based estimates of Wi, an error that can be corrected by using a constant gs/gm ratio (0.79) based on measurements on a wide range of plant species from different functional groups (including grasses and herbaceous legumes), in moist and dry conditions [31]. Also, global scale effects of mesophyll conductance and photorespiration of C3 vegetation on 13C discrimination of the terrestrial biosphere have been evident for the last four decades of atmospheric CO2 increase and concurrent change of the 13CO2/12CO2 ratio [50]. Estimates of intrinsic water use efficiency at Park Grass calculated following Ma et al. [31] were closely correlated (R2 = 0.97) with those presented by Köhler et al. [23] using the abbreviated Wi model for the same treatments and time spans.

Δ13C was obtained from the measured δ13Cp of samples and the δ13C of atmospheric CO2 (δ13Ca), as

| 6 |

Estimates of ca and δ13Ca were obtained as in Wittmer et al. [51] and Köhler et al. [52]. The time series generated by Köhler et al. [52] with ca and δ13Ca yearly average values during spring (April–June, 1917–2009) was updated until 2018. Monthly values between 2010 and 2018 from the NOAA ESRL atmospheric stations Mauna Loa, Mace Head, and Storhofdi Vestmannaeyjar [26, 53] were used for ca and δ13Ca estimation. Calculations of Δ13C and Wi were performed for each treatment, individually.

As intrinsic water use efficiency was estimated from a representative sample of a hay harvest, it represents a growing-season assimilation- and allocation-weighted measure.

Stomatal conductance

Extrapolating from elevated CO2 studies [7], we hypothesized that the atmospheric CO2 increase had already caused partial stomatal closure in grassland vegetation during the last century. This would also contribute to explain why intrinsic water use efficiency has increased at Park Grass [23] although herbage dry matter yields have not, generally, shown a similar increase. We used two independent approaches to estimate changes of stomatal conductance at Park Grass: one based on changes of yields, atmospheric CO2 concentration and 13C discrimination, and the other on the concurrent changes of the oxygen isotope composition of cellulose, as we explain below.

Following reasoning in Farquhar and Richards [19], canopy-scale, growing season-integrated stomatal conductance to CO2 (gs, in mol m−2 s−1) can be estimated as:

| 7 |

with Y denoting yield (in moles of C in harvested biomass per ground area and per year), ϕ the proportion of carbon respired and r that allocated to roots and non-harvested shoot biomass. As measurements of A were unavailable, we used the yield data as a proxy and assumed that ϕ (0.35) and r (0.4) were constants across treatments and during the century. From estimates of stomatal conductance for every year, we then calculated the percent change of stomatal conductance (%gs-change) between the beginning (period 1, subscript 1) and end (period 2, subscript 2) of the century for every treatment as:

| 8 |

Note that this procedure eliminated the constants for ϕ and r, so that the estimated %gs-changes were independent of ϕ and r, except if they had changed during the century.

For the 18O-based inference, theory [34, 54] and observations [35, 55–57] demonstrate that changes of stomatal conductance (gs) cause inverse changes of 18O-enrichment of cellulose above source water (Δ18Ocellulose, with Δ18Ocellulose ≈ δ18Ocellulose − δ18Osource). If the δ18O of source water (δ18Osource) – the water taken up by the root system – is invariant, then an increase of Δ18Ocellulose implies a parallel increase of δ18Ocellulose. Given that δ18Osource is determined by the δ18O of precipitation (δ18Orain) and plots at Park Grass receive the same precipitation, we presumed that any divergence in the δ18Ocellulose changes was independent of δ18Osource and hence attributable to changes of Δ18Ocellulose. Indeed, no long-term changes were detected for δ18Orain at Park Grass, estimated using yearly averages from the nearest monitoring station (Wallingford GNIP, c. 55 km west-southwest of Park Grass, data since 1982) [58] and outputs from the ECHAM5 global circulation model [59] for the location of the Park Grass Experiment (pixel resolution 1.125° × 1.12°, data since 1958) (Additional File 1: Fig. S2).

The effect of stomatal conductance on Δ18Ocellulose is primarily determined by three factors: (1) all oxygen in cellulose originates from water [60, 61], (2) a high proportion of that water is leaf water, which is evaporatively 18O-enriched during daytime and imprints its 18O-signal on photosynthetic products used in cellulose synthesis [62], and (3) evaporative 18O-enrichment of leaf water decreases with increasing stomatal conductance [63]. The δ18Ocellulose of a representative hay sample is a canopy-scale, growing season-integrated signal reflecting assimilation over the total time span that contributed substrate for cellulose synthesis in the tissues that comprise the sample [64]. However, the relation between stomatal conductance and Δ18Ocellulose is influenced by multiple morpho-physiological vegetation characteristics and environmental variables [65], so that stomatal conductance cannot be simply and quantitatively estimated from Δ18Ocellulose or δ18Ocellulose at present [66]. As no direct measurements of stomatal conductance were available at Park Grass during the last century, we compared δ18Ocellulose changes during the century with concurrent changes of stomatal conductance as estimated by Eqs. (7) and (8), to obtain an estimate of the stomatal conductance sensitivity of a unit change of δ18Ocellulose. Further, we compared the δ18Ocellulose change versus %gs-change relation with published data [35, 55–57] and one unpublished data set. The published data covered a wide range of plant species or genotypes in different environmental conditions in controlled environments and in the field. The data from the graphic displays of the different studies were digitized using ImageJ [67]. In this analysis, we also included (1) the relationship between Δ18Ocellulose and canopy-scale stomatal conductance predicted by a process-based 18O-enabled soil-plant-atmosphere model for a multi-seasonal data set of grassland [64] and (2) an unpublished data set from monocultures of Lolium perenne grown at CO2 concentrations of 200, 400, or 800 μmol mol−1 in controlled environments with air temperature controlled at 20 °C:16 °C and relative humidity at 50%:75% during the 16:8 h day to night cycle, and a photosynthetic photon flux density of 800 μmol m−2 s−1 during the photoperiod [68].

Individual sensitivities for each study were calculated as the slopes of ordinary least-squares linear regressions. We then calculated a mean sensitivity ± CI95% (expressed as the decrease of stomatal conductance per unit increase in δ18Ocellulose) based on the sensitivities in the individual studies (n = 6, Additional file 1: Table S2). Additionally, we used an analogous procedure to calculate the stomatal conductance-sensitivity in terms of %gs-decrease (Eq. 8) per unit increase in δ18Ocellulose. In that, we took the mean stomatal conductance value of each study as the reference for calculating the %-decreases of stomatal conductance using the stomatal conductance versus δ18Ocellulose relationship of that study. On average of all the studies, stomatal conductance decreased by 39% per 1‰ increase of δ18Ocellulose.

Statistical analysis

We tested the long-term response of intrinsic water use efficiency, yield, δ18Ocellulose, and N acquisition by comparing the average values of 15-year periods at the beginning (1917–1931, period 1) and the end (2004–2018, period 2) of the last 100 years. The long-term change was calculated as the difference between the averages from period 1 and 2, for (1) every treatment individually (n = 26–30), (2) grouping the data into dicot-rich (n = 164–173) and grass-rich (n = 161–174) treatments, and (3) combining all data together (n = 330–348) (see Additional file 1: Table S1 for detailed information about the sample size). t tests were used for testing the differences between periods. Additional t tests were performed to determine whether the long-term response of the analyzed variables differed between treatments with different plant functional group composition (dicot-rich vs. grass-rich communities). For this, data corresponding to period 2 were normalized by subtracting the average value from period 1, for every individual treatment (thus obtaining the net long-term change). Additionally, the relationship between the long-term changes of different variables (e.g., change in intrinsic water use efficiency vs. change in δ18Ocellulose) was tested using ordinary least-squares linear regressions. Regression analysis was also used to test the effect of multiple parameters on yield. All statistical analyses were conducted in R v.4.0.2 [69]. The R package ggplot2 [70] was used for data plotting.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Spring (April–June) meteorological data during the last 100 years. Figure S2. δ18Orain long-term trends. Figure S3. Yields at Park Grass 1917–2018. Table S1. Sample size for all treatments. Table S2. List of publications used for estimation of the average sensitivity of stomatal conductance (gs) to δ18Ocellulose. Table S3. Pre-1960 yield offset-correction.

Acknowledgements

We thank Iris H. Köhler for preliminary analyses and discussions, Jianjun Zhu for the support with sampling, Monika Michler for sample preparation, Anja Schmidt for the cellulose extraction, and the Rothamsted data curators for access to data from the Electronic Rothamsted Archive (e-RA).

Consent to participate

Not applicable

Authors’ contributions

J.C.B.C. and H.S. designed the study. A.M. guided the sampling in the Rothamsted archive. R.S. performed the carbon and oxygen isotope and carbon and nitrogen elemental analyses. R.T.H. performed the phosphorus analyses. J.C.B.C. analyzed all data. J.C.B.C. and H.S. interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG SCHN 557/9-1). The Rothamsted Long-term Experiments National Capability (LTE-NC) is supported by the UK BBSRC (Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, BBS/E/C/000 J0300) and the Lawes Agricultural Trust. Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Craine JM, Elmore AJ, Wang L, Aranibar J, Bauters M, Boeckx P, et al. Isotopic evidence for oligotrophication of terrestrial ecosystems. Nat Ecol Evol. 2018;2:1735–1744. doi: 10.1038/s41559-018-0694-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Du E, Terrer C, Pellegrini AFA, Ahlström A, van Lissa CJ, Zhao X, et al. Global patterns of terrestrial nitrogen and phosphorus limitation. Nat Geosci. 2020;13:221–226. doi: 10.1038/s41561-019-0530-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feng Z, Rütting T, Pleijel H, Wallin G, Reich PB, Kammann CI, et al. Constraints to nitrogen acquisition of terrestrial plants under elevated CO2. Glob Chang Biol. 2015;21:3152–3168. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Körner C. Plant CO2 responses: an issue of definition, time and resource supply. New Phytol. 2006;172:393–411. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01886.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lavergne A, Voelker S, Csank A, Graven H, de Boer HJ, Daux V, et al. Historical changes in the stomatal limitation of photosynthesis: empirical support for an optimality principle. New Phytol. 2020;225:2484–2497. doi: 10.1111/nph.16314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ainsworth EA, Long SP. What have we learned from 15 years of free-air CO2 enrichment (FACE)? A meta-analytic review of the responses of photosynthesis, canopy properties and plant production to rising CO2. New Phytol. 2005;165:351–372. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.01224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ainsworth EA, Rogers A. The response of photosynthesis and stomatal conductance to rising [CO2]: mechanisms and environmental interactions. Plant Cell Environ. 2007;30:258–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2007.01641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berry JA, Beerling DJ, Franks PJ. Stomata: key players in the earth system, past and present. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2010;13:232–239. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2010.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hetherington AM, Woodward FI. The role of stomata in sensing and driving environmental change. Nature. 2003;424:901–908. doi: 10.1038/nature01843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Medlyn BE, Duursma RA, Eamus D, Ellsworth DS, Prentice IC, Barton CVM, et al. Reconciling the optimal and empirical approaches to modelling stomatal conductance. Glob Chang Biol. 2011;17:2134–2144. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2010.02375.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Franks PJ, Adams MA, Amthor JS, Barbour MM, Berry JA, Ellsworth DS, et al. Sensitivity of plants to changing atmospheric CO2 concentration: from the geological past to the next century. New Phytol. 2013;197:1077–1094. doi: 10.1111/nph.12104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cernusak LA, Ubierna N, Winter K, Holtum JAM, Marshall JD, Farquhar GD. Environmental and physiological determinants of carbon isotope discrimination in terrestrial plants. New Phytol. 2013;200:950–965. doi: 10.1111/nph.12423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McGrath JM, Lobell DB. Reduction of transpiration and altered nutrient allocation contribute to nutrient decline of crops grown in elevated CO2 concentrations. Plant Cell Environ. 2013;36:697–705. doi: 10.1111/pce.12007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oyewole OA, Inselsbacher E, Näsholm T. Direct estimation of mass flow and diffusion of nitrogen compounds in solution and soil. New Phytol. 2014;201:1056–1064. doi: 10.1111/nph.12553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kattge J, Knorr W, Raddatz T, Wirth C. Quantifying photosynthetic capacity and its relationship to leaf nitrogen content for global-scale terrestrial biosphere models. Glob Chang Biol. 2009;15:976–991. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2008.01744.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith NG, Keenan TF. Mechanisms underlying leaf photosynthetic acclimation to warming and elevated CO2 as inferred from least-cost optimality theory. Glob Chang Biol. 2020;26:5202–5216. doi: 10.1111/gcb.15212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wright IJ, Reich PB, Westoby M. Least-cost input mixtures of water and nitrogen for photosynthesis. Am Nat. 2003;161:98–111. doi: 10.1086/344920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buckley TN. Modeling stomatal conductance. Plant Physiol. 2017;174:572–582. doi: 10.1104/pp.16.01772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farquhar GD, Richards RA. Isotopic composition of plant carbon correlates with water-use efficiency in wheat genotypes. Aust J Plant Physiol. 1984;11:539–552. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kunrath TR, Lemaire G, Sadras VO, Gastal F. Water use efficiency in perennial forage species: interactions between nitrogen nutrition and water deficit. Field Crops Res. 2018;222:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.fcr.2018.02.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lüscher A, Daepp M, Blum H, Hartwig UA, Nösberger J. Fertile temperate grassland under elevated atmospheric CO2—role of feed-back mechanisms and availability of growth resources. Eur J Agron. 2004;21:379–398. doi: 10.1016/j.eja.2003.10.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jenkinson DS, Potts JM, Perry JN, Barnett V, Coleman K, Johnston AE. Trends in herbage yields over the last century on the Rothamsted Long-term continuous Hay experiment. J Agric Sci. 1994;122:365–374. doi: 10.1017/S0021859600067290. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Köhler IH, Macdonald AJ, Schnyder H. Last-century increases in intrinsic water-use efficiency of grassland communities have occurred over a wide range of vegetation composition, nutrient inputs, and soil pH. Plant Physiol. 2016;170:881–890. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.01472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Storkey J, Macdonald AJ, Poulton PR, Scott T, Köhler IH, Schnyder H, et al. Grassland biodiversity bounces back from long-term nitrogen addition. Nature. 2015;528:401–404. doi: 10.1038/nature16444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Friedli H, Lötscher H, Oeschger H, Siegenthaler U, Stauffer B. Ice core record of the 13C/12C ratio of atmospheric CO2 in the past two centuries. Nature. 1986;324:237–238. doi: 10.1038/324237a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dlugokencky EJ, Mund JW, Crotwell AM, Crotwell MJ, Thoning KW. Atmospheric carbon dioxide dry air mole fractions from the NOAA ESRL carbon cycle cooperative global air sampling network, 1968-2018. NOAA ESRL. 2019. 10.15138/wkgj-f215.

- 27.Crawley MJ, Johnston AE, Silvertown J, Dodd M, de Mazancourt C, Heard MS, et al. Determinants of species richness in the Park Grass Experiment. Am Nat. 2005;165:179–192. doi: 10.1086/427270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lemaire G, Jeuffroy M-H, Gastal F. Diagnosis tool for plant and crop N status in vegetative stage: theory and practices for crop N management. Eur J Agron. 2008;28:614–624. doi: 10.1016/j.eja.2008.01.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liebisch F, Bünemann EK, Huguenin-Elie O, Jeangros B, Frossard E, Oberson A. Plant phosphorus nutrition indicators evaluated in agricultural grasslands managed at different intensities. Eur J Agron ronomy. 2013;44:67–77. doi: 10.1016/j.eja.2012.08.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Güsewell SN. P ratios in terrestrial plants: variation and functional significance. New Phytol. 2004;164:243-66. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Ma WT, Tcherkez G, Wang XM, Schäufele R, Schnyder H, Yang Y, et al. Accounting for mesophyll conductance substantially improves 13C-based estimates of intrinsic water-use efficiency. New Phytol. 2021;229:1326–1338. doi: 10.1111/nph.16958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cornwell WK, Wright IJ, Turner J, Maire V, Barbour MM, Cernusak LA, et al. Climate and soils together regulate photosynthetic carbon isotope discrimination within C3 plants worldwide. Glob Ecol Biogeogr. 2018;27:1056–1067. doi: 10.1111/geb.12764. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cowan IR, Farquhar GD. Stomatal function in relation to leaf metabolism and environment. In: Jennings DH, editor. Integration of activity in the higher plant. Cambridge: University Press; 1977. pp. 471–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Farquhar GD, Barbour MM, Henry BK. Interpretation of oxygen isotope composition of leaf material. In: Griffiths H, editor. Stable isotopes: integration of biological, ecological and geochemical processes. Oxford: BIOS Scientific Publishers; 1998. pp. 27–61. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barbour MM, Fischer RA, Sayre KD, Farquhar GD. Oxygen isotope ratio of leaf and grain material correlates with stomatal conductance and grain yield in irrigated wheat. Funct Plant Biol. 2000;27:625–637. doi: 10.1071/PP99041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bowen GJ, Cai Z, Fiorella RP, Putman AL. Isotopes in the water cycle: regional- to global-scale patterns and applications. Annu Rev Earth Planet Sci. 2019;47:453–479. doi: 10.1146/annurev-earth-053018-060220. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grossiord C, Buckley TN, Cernusak LA, Novick KA, Poulter B, Siegwolf RTW, et al. Plant responses to rising vapor pressure deficit. New Phytol. 2020;226:1550–1566. doi: 10.1111/nph.16485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Robertson GP, Vitousek PM. Nitrogen in agriculture: balancing the cost of an essential resource. Annu Rev Environ Resour. 2009;34:97–125. doi: 10.1146/annurev.environ.032108.105046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cheng L, Zhang L, Wang Y-P, Canadell JG, Chiew FHS, Beringer J, et al. Recent increases in terrestrial carbon uptake at little cost to the water cycle. Nat Commun. 2017;8:110. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00114-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lawes JB, Gilbert JH. Report of experiments with different manures on permanent meadow land: part II: produce of constituents per acre. J R Agric Soc Engl. 1859;20:228–246. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Silvertown J, Poulton P, Johnston E, Edwards G, Heard M, Biss PM. The Park Grass Experiment 1856–2006: its contribution to ecology. J Ecol. 2006;94:801–814. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2745.2006.01145.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dodd ME, Silvertown J, McConway K, Potts J, Crawley M. Application of the British national vegetation classification to the communities of the Park Grass Experiment through time. Folia Geobot. 1994;29:321–334. doi: 10.1007/BF02882911. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brendel O, Iannetta PPM, Stewart D. A rapid and simple method to isolate pure alpha-cellulose. Phytochem Anal. 2000;11:7–10. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1565(200001/02)11:1<7::AID-PCA488>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gaudinski JB, Dawson TE, Quideau S, Schuur EAG, Roden JS, Trumbore SE, et al. Comparative analysis of cellulose preparation techniques for use with 13C, 14C, and 18O isotopic measurements. Anal Chem. 2005;77:7212–7224. doi: 10.1021/ac050548u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hanson WC. The photometric determination of phosphorus in fertilizers using the phosphovanado-molybdate complex. J Sci Food Agric. 1950;1:172–173. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.2740010604. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bowley HE, Mathers AW, Young SD, Macdonald AJ, Ander EL, Watts MJ, et al. Historical trends in iodine and selenium in soil and herbage at the Park Grass Experiment, Rothamsted research. UK Soil Use Manag. 2017;33:252–262. doi: 10.1111/sum.12343. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ehleringer JR, Hall AE, Farquhar GD. Stable isotopes and plant carbon-water relations. San Diego: Academic Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brooks A, Farquhar GD. Effect of temperature on the CO2/O2 specificity of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase and the rate of respiration in the light. Planta. 1985;165:397–406. doi: 10.1007/BF00392238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Farquhar GD, Oleary MH, Berry JA. On the relationship between carbon isotope discrimination and the intercellular carbon dioxide concentration in leaves. Aust J Plant Physiol. 1982;9:121–137. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Keeling RF, Graven HD, Welp LR, Resplandy L, Bi J, Piper SC, et al. Atmospheric evidence for a global secular increase in carbon isotopic discrimination of land photosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2017;114:10361–10366. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1619240114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wittmer MHOM, Auerswald K, Tungalag R, Bai YF, Schäufele R, Bai CH, et al. Carbon isotope discrimination of C3 vegetation in Central Asian grassland as related to long-term and short-term precipitation patterns. Biogeosciences. 2008;5:913–924. doi: 10.5194/bg-5-913-2008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Köhler IH, Poulton PR, Auerswald K, Schnyder H. Intrinsic water-use efficiency of temperate seminatural grassland has increased since 1857: an analysis of carbon isotope discrimination of herbage from the Park Grass Experiment. Glob Chang Biol. 2010;16:1531–1541. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2009.02067.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.White J, Vaughn B, Michel S. https://www.esrl.noaa.gov/gmd/dv/data/. Stable isotopic composition of atmospheric carbon dioxide (13C and 18O) carbon cycle cooperative global air sampling network, 1990–2014. ftp://aftp.cmdl.noaa.gov/data/trace_gases/co2c13/flask/ (2020). Accessed 10 Oct 2020.

- 54.Scheidegger Y, Saurer M, Bahn M, Siegwolf R. Linking stable oxygen and carbon isotopes with stomatal conductance and photosynthetic capacity: a conceptual model. Oecologia. 2000;125:350–357. doi: 10.1007/s004420000466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sullivan PF, Welker JM. Variation in leaf physiology of Salix arctica within and across ecosystems in the High Arctic: test of a dual isotope (Δ13C and Δ18O) conceptual model. Oecologia. 2006;151:372. doi: 10.1007/s00442-006-0602-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Grams TEE, Kozovits AR, Häberle K-H, Matyssek R, Dawson TE. Combining δ13C and δ18O analyses to unravel competition, CO2 and O3 effects on the physiological performance of different-aged trees. Plant Cell Environ. 2007;30:1023–1034. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2007.01696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Moreno-Gutiérrez C, Dawson TE, Nicolás E, Querejeta JI. Isotopes reveal contrasting water use strategies among coexisting plant species in a Mediterranean ecosystem. New Phytol. 2012;196:489–496. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2012.04276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Global Network of Isotopes in Precipitation. The GNIP Database. IAEA/WMO https://nucleus.iaea.org/wiser/index.aspx. Accessed 25 Oct 2020.

- 59.Werner M. ECHAM5-wiso simulation data- present-day, mid-Holocene, and last glacial maximum. PANGAEA; 2019. 10.1594/PANGAEA.902347.

- 60.DeNiro MJ, Epstein S. Relationship between the oxygen isotope ratios of terrestrial plant cellulose, carbon dioxide, and water. Science. 1979;204:51–53. doi: 10.1126/science.204.4388.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liu HT, Gong XY, Schäufele R, Yang F, Hirl RT, Schmidt A, et al. Nitrogen fertilization and δ18O of CO2 have no effect on 18O-enrichment of leaf water and cellulose in Cleistogenes squarrosa (C4) – is VPD the sole control? Plant Cell Environ. 2016;39:2701–2712. doi: 10.1111/pce.12824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cernusak LA, Barbour MM, Arndt SK, Cheesman AW, English NB, Feild TS, et al. Stable isotopes in leaf water of terrestrial plants. Plant Cell Environ. 2016;39:1087–1102. doi: 10.1111/pce.12703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Barbour MM. Stable oxygen isotope composition of plant tissue: a review. Funct Plant Biol. 2007;34:83–94. doi: 10.1071/FP06228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hirl RT, Ogée J, Ostler U, Schäufele R, Baca Cabrera JC, Zhu J, et al. Temperature-sensitive biochemical 18O-fractionation and humidity-dependent attenuation factor are needed to predict δ18O of cellulose from leaf water in a grassland ecosystem. New Phytol. 2021;229:3156–3171. doi: 10.1111/nph.17111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Song X, Farquhar GD, Gessler A, Barbour MM. Turnover time of the non-structural carbohydrate pool influences δ18O of leaf cellulose. Plant Cell Environ. 2014;37:2500–2507. doi: 10.1111/pce.12309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Roden JS, Farquhar GD. A controlled test of the dual-isotope approach for the interpretation of stable carbon and oxygen isotope ratio variation in tree rings. Tree Physiol. 2012;32:490–503. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tps019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9:671–675. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Baca Cabrera JC, Hirl RT, Zhu J, Schäufele R, Schnyder H. Atmospheric CO2 and VPD alter the diel oscillation of leaf elongation in perennial ryegrass: compensation of hydraulic limitation by stored-growth. New Phytol. 2020;227:1776–1789. doi: 10.1111/nph.16639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria. 2020. https://www.R-project.org/. Accessed 8 Jun 2020.

- 70.Wickham H. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. New York: Springer Verlag; 2016. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Spring (April–June) meteorological data during the last 100 years. Figure S2. δ18Orain long-term trends. Figure S3. Yields at Park Grass 1917–2018. Table S1. Sample size for all treatments. Table S2. List of publications used for estimation of the average sensitivity of stomatal conductance (gs) to δ18Ocellulose. Table S3. Pre-1960 yield offset-correction.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.