Abstract

Understanding transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 informs infection prevention practices. Air sampling devices were placed in patient hospital rooms for consecutive collections with and without masks. With patient mask use, no virus was detected in the room. High viral load and fewer days from symptom onset were associated with viral particulate dispersion.

Keywords: COVID-19, infection prevention and hospital epidemiology, viral pneumonia

Public health and infection control strategies regarding the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic are informed by our understanding of the spread of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) virus. Viral spread, as defined by dispersion of viral particulates, correlates to the period of infectiousness for person-to-person transmission [1]. Viral load rapidly declines during the first week after symptom onset, and while shedding of viral particles may persist for several weeks, live virus has been cultured only early in the course of infection [1, 2]. The significance of transmission via aerosolized droplet nuclei (<5 μm in diameter), which may remain airborne as infectious particles for several hours, has prompted investigation [3–5]. However, a meta-analysis described large respiratory droplets as the primary mode of transmission, in accordance with Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines [2, 6]. Furthermore, certain patient characteristics and biomarkers have been associated with worse disease course and higher viral loads [6, 7]. With limited exceptions, the current literature infrequently describes patient clinical features associated with environmental detection of virus [4]. We measured the impact of source-control mask use and the associated patient clinical characteristics on environmental burden of SARS-CoV-2 in hospitalized patients.

METHODS

This was a single-arm nonrandomized controlled trial to study the effect of mask use on environmental spread of SARS-CoV-2 virus. Participants included SARS-CoV-2-positive adults admitted to a single academic center from April 13 to May 22, 2020. Participants provided written consent as approved by the Wake Forest Institutional Review Board (00064866). Patients were selected on a rolling basis using the Epic electronic health record (EHR) to identify adults with clinical laboratory–confirmed reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)–positive status for SARS-CoV-2 (Epic Systems Co, Verona, WI, USA). Patients requiring mechanical ventilatory support at the time of enrollment were excluded.

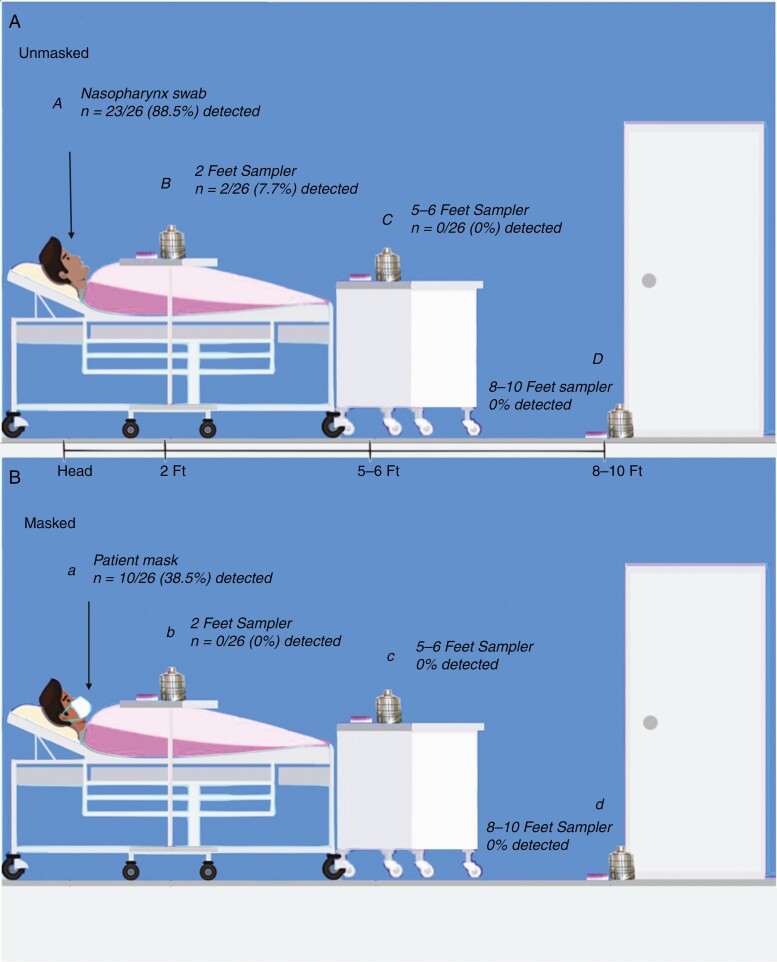

Sample collection took place in hospital rooms with heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems exchanging room air 6 times per hour using MERV-14 filters with the capacity to filter 90% of particles 1–3 microns in diameter [8]. Following enrollment, a nasopharynx (NP) swab was obtained from each participant for viral load before air sampling. Andersen air sampling devices and surface sedimentation plates were placed at 3 locations in patient hospital rooms (Figure 1). To study the effect of source-control mask use on environmental contamination of virus, 2 air sample runs of 30 minutes each were obtained for each study participant. During the first run, the patient was not wearing a mask, followed by a second run with patients wearing a nonmedical 3-ply procedural mask (Haowei Weiye Technology Development, Harbin, China). Viral transport media (VTM) on sedimentation plates from Anderson air samplers were pooled from stages 1 and 2 (filter sizes ≥5 μm) and stages 3–6 (filter sizes <5 μm) to separate large droplets from aerosols. Following a standard pattern, a 3x3-inch cutting from the center of patient masks was stored in VTM. Participants had 20 samples each: 9 samples from both environmental sampling runs (3 stations with 1 surface sample and 2 pooled samples from air sampling devices), patient mask, and NP swab. SARS-CoV-2 RNA was extracted from VTM, reverse-transcribed into cDNA for viral amplification, and quantified by qPCR with CDC N1 and N2 detection assays. The viral load was reported as the threshold cycle (Ct), with lower Ct values representing higher viral loads. Our lower detection limit was ~75 viral genome copies per site measured, which falls below the infectious dose of coronaviruses [9]. Clinical characteristics including comorbidities and biomarkers were recorded from the EHR and patient interview. Using R statistical software, we assessed the association of NP viral load and days since symptom onset with positive detection in the mask or environment using 2-sample t tests. Random Forest imputation was used to impute 2 missing symptom onset values. We used Firth logistic regression in independent models to investigate the odds of positive detection of viral spread with clinical factors of interest (eg, diabetes, hypertension, etc.), each controlling for days since symptom onset. This model accurately detects significance but is imprecise with magnitude of association in small samples.

Figure 1.

A, Unmasked patient sample collection with polymerase chain reaction (PCR) detection of virus in nasopharynx swab (A) and samplers located at 2 feet, 5–6 feet, and 8–10 feet (B, C, and D) from the patient’s head. B, Masked patient sample collection with PCR virus detection in patient mask (a) and sampler placement the same as above (b, c, and d). Sampler stations included an air sampler and a surface sedimentation plate.

RESULTS

The study population included 26 adults with a mean age (SD) of 58.4 (15.9) years (male 62%), with comorbidities including hypertension (73%), obesity (62%), type 2 diabetes (46%), and heart disease (35%). Viral spread, as defined by detection of viral particulate dispersion in the patient mask or environment, was present in 11 of 26 patients (42%) (Table 1). Viral particles in large respiratory droplets were recovered adjacent to the head from 2 of 26 patients (8%; droplet sizes ≥5 μm) who were closer to symptom onset (2 and 4 days). No aerosol-sized particles were detected in air samplers for masked or unmasked runs. No virus was recovered from air samplers or surface plates from runs with patients wearing masks. Detection of virus in masks or the environment was significantly associated with higher NP viral loads (mean, 20.6; 95% CI, 17.9–13.2) for positive emission (for negative emission: mean, 31.3; 95% CI, 29.1–33.6; P < .001). Furthermore, viral dispersion was linked to fewer days from symptom onset (mean, 5.09; 95% CI, 2.03–8.15) for positive emission patients (vs negative emission patients: mean, 10.23; 95% CI, 7.61–12.85; P = .015). From our Firth logistic regression models controlling for time from symptom onset, clinical features associated with viral spread, as defined above, included diabetes (P = .02), hypertension (P = .04), heart disease (P = .01), obesity (P = .06), acute kidney injury (AKI; P = .01), and leukocytosis (P = .02). There was no significant difference between viral spreaders and nonspreaders in vital signs or level of care during collections (Supplementary Data).

Table 1.

Clinical Features Associated With Spread of SARS-CoV-2a

| Overall (n = 26) | Positive Spread (n = 11) | Negative Spread (n = 15) | P Valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 58.35 (15.90) | 63.18 (10.28) | 54.80 (18.54) | .21 |

| Sex, male, No. (%) | 16 (61.5) | 8 (72.7) | 8 (53.3) | .35 |

| Race/ethnicity, No. (%) | .625 | |||

| Black | 5 (19.2) | 3 (27.3) | 2 (13.3) | |

| Hispanic | 12 (46.2) | 5 (45.5) | 7 (46.7) | |

| White | 9 (34.6) | 3 (27.3) | 6 (40.0) | |

| Clinical features, mean (SD) [95% CI] | ||||

| NP viral load Ct | 26.76 (6.83) | 20.55 [17.9–13.2] | 31.32 [29.1–33.6] | <.001 |

| Days from symptom onset | 8.06 (5.47) | 5.09 [2.03–8.15] | 10.23 [7.61–12.85] | .015 |

| Days from lab diagnosis | 3.58 (3.50) | 1.91 (1.58) | 4.80 (4.04) | .034 |

| Comorbidities, No. (%) | ||||

| Type 2 diabetes | 12 (46.2) | 9 (81.8) | 3 (20.0) | .024 |

| Hypertension | 19 (73.1) | 11 (100.0) | 8 (53.3) | .039 |

| Heart disease | 9 (34.6) | 7 (63.6) | 2 (13.3) | .008 |

| Obesity | 16 (61.5) | 8 (72.7) | 8 (53.3) | .058 |

| Laboratory biomarkers, No. (%) | ||||

| Acute kidney injury | 13 (50.0) | 9 (81.8) | 4 (26.7) | .012 |

| Leukocytosis | 10 (38.5) | 6 (54.5) | 4 (26.7) | .016 |

Abbreviations: Ct, cycle threshold; NP, nasopharynx; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

aSpread defined by detection of SARS-CoV-2 viral particles in the patient mask or hospital room.

b P values for demographics, viral load Ct, days from symptom onset, and days from lab diagnosis are from univariate t tests. All other P values are from a logistic regression model using Firth’s bias correction, controlling for days from symptom onset.

DISCUSSION

In a limited sample of 26 hospitalized patients, SARS-CoV-2 was detected only within large respiratory droplet range in unmasked patients (≤2 feet from the head of the patient), using air sampling methods validated on airborne viruses [10]. These findings support the use of contact and droplet precautions in routine clinical scenarios in hospitals. We demonstrated that patient mask use stopped environmental dispersion of virus over 30-minute collections, which confirms low risk of viral transmission from infected hosts while using masks [11]. Viral load (Ct ≤25), followed by shorter duration from symptom onset (≤8 days), had the strongest association with spread of viral particles, which supports recent CDC strategies for decreased quarantine time following infection [12]. Clinical factors associated with severe disease course were linked to viral spread, including diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, obesity, AKI, and leukocytosis [7]. Given limitations on sample size, we are unable to conclude whether comorbidities are independently associated with increased transmission or if people with more comorbidities have increased viral shedding due to greater severity of infection. The other main limitation of this study was decreased sensitivity of detection limits compared with other environmental sampling studies [3, 4]. Our findings may lead to future investigations including use of patient masks as a cost-effective method to describe patient characteristics associated with viral spread.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Open Forum Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Financial support. Funding for this work came from internal sources.

Potential conflicts of interest. None of the authors has any conflicts of interest to report.

Patient consent. Patients’ written consent was obtained. This work was approved by Wake Forest School of Medicine IRB ethical committee under IRB# 00064866.

References

- 1. He X, Lau EHY, Wu P, et al. Temporal dynamics in viral shedding and transmissibility of COVID-19. Nat Med 2020; 26:672–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Meyerowitz, EA, Richterman A, Gandhi RT, Sax PE. Transmission of SARS-CoV-2: a review of viral, host, and environmental factors. Ann Intern Med. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lednicky JA, Lauzardo M, Fan ZH, et al. Viable SARS-CoV-2 in the air of a hospital room with COVID-19 patients. Int J Infect Dis 2020; 100:476–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chia PY, Coleman KK, Tan YK, et al. ; Singapore 2019 Novel Coronavirus Outbreak Research Team . Detection of air and surface contamination by SARS-CoV-2 in hospital rooms of infected patients. Nat Commun 2020; 11:2800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. van Doremalen N, Bushmaker T, Morris DH, et al. Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS-CoV-1. N Engl J Med 2020; 382:1564–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. How COVID-19 spreads. Available at: www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/how-covid-spreads.html. Accessed 11 October 2020. [PubMed]

- 7. Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2020; 395:1054–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Environmental Protection Agency. What is a MERV rating?https://www.epa.gov/indoor-air-quality-iaq/what-merv-rating-1. Accessed 31 December 2020.

- 9. Schröder I. COVID-19: a risk assessment perspective. ACS Chem Health Safety. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bischoff WE, McNall RJ, Blevins MW, et al. Detection of measles virus RNA in air and surface specimens in a hospital setting. J Infect Dis 2016; 213:600–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Baker MA, Fiumara K, Rhee C, et al. Low risk of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) among patients exposed to infected healthcare workers. Clin Infect Dis. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Options to reduce quarantine for contacts of persons with SARS-CoV-2 infection using symptom monitoring and diagnostic testing. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/more/scientific-brief-options-to-reduce-quarantine.html. Accessed 7 December 2020. [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.