Abstract

Previous studies on the effect of cartoon hardly consider the moderating role of colour. Additionally, studies on the use of social media for health promotion pay less attention to sustainability of health behaviour. In this study, we examined the moderating role of colour on the effectiveness of COVID-19 YouTube animated cartoons on health behaviour of social media users in Nigeria. We survey a total of 470 social media users in Nigeria who reported exposure to YouTube COVID-19 animated cartoons. It was found that colour significantly predict recall of YouTube animated cartoons on COVID-19. In addition, the result of the study revealed that colour significantly moderate impact ofCOVID-19 YouTube animated cartoons on health behaviour of social media users. The result further showed that exposure to COVID-19 YouTube animated cartoons will significantly predict knowledge of the virus. The result also showed that recall of messages theme in COVID-19 YouTube animated cartoons significantly predicts health behaviour of social media users. Finally, the result of the study showed that self-efficacy, task self-efficacy, coping self-efficacy, and outcome expectancy significantly predict health behaviour sustainability among social media users who are exposed to COVID-19 YouTube animated cartoon. We highlighted the implications of these results on health promotions.

Keywords: animated cartoons; COVID-19; health behaviour; social media, YouTube

INTRODUCTION

The objective of this study was to advance literature on the role of social media in health promotion and health advocacy by recognizing the moderating role of colour on the effectiveness of YouTube animated cartoons on health behaviour. In addition, the current study took into account the contribution of exposure to health messages on knowledge of health issues. The study equally aimed to ascertain if message recall is linked to health behaviour. Finally, health behaviour sustainability was explored with the utilization of social cognitive theory. Therefore, a model was developed to drive the study objectives.

Colour is an important component of visual communication because of its attention catching ability. Colour also has the capacity of sustaining the attention of message receivers as well as revealing the details of the message to the receivers. Artists make use of colour to emphasize some aspects of messages as well as communicate desired messages. Within the context of health promotion, colour has been regarded as essential, especially in the use of posters to communicate health messages to the target receivers. Colour equally has the potential of evoking emotions from people. Lee et al. (2020) conducted an experiment wherein they set to ascertain how colour evokes peoples’ emotions based on if it is an object or light in colour such as blue, yellow, red, or green. The researcher examined 30 participants and reported that colour significantly influences people’s emotions. Their results point to the fact that colour plays a role in evoking emotions from message receivers. Yang and Wei (2020) also reported that colour was an essential feature in visual communication. It is perhaps in consideration of the critical role of colour that they carefully considered it in visual arts in areas like television broadcasting, arts works, movie production, illustrations, as well as cartoons.

Generally, cartoons are considered as a comic way of presenting serious issues. Cartoons provide an opportunity to communicate messages to the target receivers in a manner that entertains them, educates them, and inform them at the same time. Abraham (2009) notes further that through the instrumentality of cartoon, serious issues of public interest can be framed in ways that assist the general public to understand the issue better. He adds that cartoons offer information with an opportunity for people to engage in deep reflection on the issues contained in the cartoon messages. In the views of Onakpa (Onakpa 2014), the success or otherwise of cartoon messages is dependent on how familiar the target receivers are with the issues communicated. Onakpa notes further that cartoons have classifications. These are editorial, the comic strip, and animated cartoons. The focus of the current study was on animated cartoons which Onuora et al. (2020) described as dramatized cartoons.

According to Onuora et al. (2020), animated cartoons can be defined as moveable images that make effort to communicate information regarding an issue of public interest. They add that the dichotomy between animated cartoons and other forms of cartoons is largely because while the former are fleeting, the latter are still. Michelsen (2009) says that animated cartoons are mostly associated with lively and usually humorous images. Oyero and Oyesomi (2014, p. 94) conceptualize animated cartoons as movies that are filmed with the utilization of sequence of drawings which slightly differ in manners that make them appear as though they are moving. Hitherto, animated cartoons are mainly communicated through television. However, there appears to be a change because of the emergence of YouTube, which is a social media platform.

The YouTube has been found as a viable venue for animated cartoons. Animated cartoons focusing on different messages are usually communicated to social media users through YouTube. Such messages cover areas like politics, education, marketing, health, among others. However, in the current study, attention was paid to health, and in particular, Coronavirus disease (COVID-19). This is because since the outbreak of COVID-19 in December, 2019, YouTube has been used to communicate meaning related to the virus to social media users. These animated cartoons come in different colours and languages such as English, Hausa, Igbo, and Yoruba. In this study, we examined how cartoon colour moderate the effectiveness of such messages on health behaviour as related to COVID-19 using a sample in Nigeria.

COVID-19 in perspective

COVID-19 was first reported in a city called Wuhan, the Republic of China in December 2019. At first, it was regarded as a Chinese problem and as such, no one imagined that the virus had the propensity to spread across the world and bring economic and political activities to a standstill. Gever and Ezeah (2020) note that from the small city of Wuhan, the virus spilled over to other areas of the country and started spreading to other countries of the world to a level that borders of countries were shut down. In worst cases, inter-city movements among countries were restricted, schools were shutdown, places of worship were also affected, and public gatherings were discouraged. Peoples’ lives and livelihood have been greatly affected by COVID-19.

The most disturbing aspect of the virus is that it currently has no known cure; thus making prevention one of the most reliable ways of combating it. The virus is deadly because it has the potential of killing those who contract it. According to Wu et al. (2020), COVID-19 has a low to moderate (estimated 2–5%) mortality rate while contracting the virus may occur as a result of contacts with infected persons. For example, when a droplet from an infected person is inhaled, it can transmit the virus to another. In addition, an infected person can infect an object and other unsuspecting persons who come in contact with such an object can as well get infected. Scholars (Ale, 2020; Melugbo et al., 2020; Odii et al., 2020) agree that COVID-19 has resulted to significant changes in human activities with varying degrees of impact.

Since the outbreak of the virus in December last year, many people have lost their lives while cases have continued to increase across the world. For example, the World Health Organization (WHO, 2020a) says that as at July 28, 2020, a total of 16 341 920 cases have been confirmed globally, while 650 805 casualties have been recorded for the virus. In Nigeria, a total of 41 180 cases have been confirmed as at July 28, 2020, with 860 deaths. These figures imply that the number of casualties has continued to grow and appropriate health behaviour is the only way forward because of lack of a definite cure for the virus. The recommended health behaviour by WHO are: regular hand washing, use of alcohol-based hand sanitizers, avoiding public gathering, practising physical distancing, use of facemask, avoiding handshake, among others. These preventive health behaviour have been identified as crucial for the success of the fight against the spread of the virus. It is on this note that different communication approaches have been adopted with a view to making sure that the masses have accurate and up to date information that will assist them in preventing and contracting the virus. Consequently, different communication platforms have been used to communicate information on the virus to the general public. The social media such as YouTube has also featured feasibly in these efforts to combat COVID-19.

The effect of animated cartoons and the power of colour

Behaviour change is one of the aims of communication. To effectively change behaviour through communication, different message elements are utilized. The effect of cartoons has been examined in literature. Maranzana (2014) did a study to determine the impact of using animated cartoons through drawings to assist learning, and also to help the learners improve on their learning. The study was carried out by exposing the participants to episodes of animated cartoon in the classroom by first removing captions and eventually including captions. Maranzana subsequently requested the participants in the study to take note of the words that they did not know and make efforts to assume their meaning from the context. Maranzana then requested the participants to provide information regarding their experiences. The outcome of the study showed that animated cartoons were effective in supporting students’ learning efforts. Rai et al. (2016) utilized an observational approach to ascertain the effect of animated cartoons on children aged 5–15 and found that 33% of children who are exposed to cartoons revealed an increase in their violent behaviour. They also reported that cartoons were effective in attracting and sustaining the attention of the sample examined. James et al. (2012) carried out a quasi experimental study to determine the effectiveness of animated cartoons on children who were within the ages of 3 to 6 years and were going through venipuncture to know how effective animated cartoons can be as a distraction strategy to reduce the perception of pain. The researcher reported that animated cartoons were effective as a distraction strategy to relieve children from pains. Although these researchers have reported that, cartoons are effective in behaviour change, they paid less attention to the moderating role of colour. Marcus et al. (2011) conducted a study to determine the effect of visuals on warning health information and reported that the visual attention of the sample was more towards health warnings than to brand information on plain packs versus branded packs. The only aspect that was not examined by the study of Marcus et al., was the moderating role of colour in determining the visual attention of the study sample.

In visual communication, colour is one of the important elements that is considered with the hope that behaviour change will be achieved. Brown et al. (2013) hold the view that colour is as important in visual communication as the storyline itself. The implication of the view of Brown is that in making decisions regarding a storyline that will best assist in behaviour change, there is the need to also look at the colour combination. Kuhbandner and Pekrun (2013) corroborate that colour is known to have effect on people in manners which cannot be too obvious and as such, colour combination is essential in visual communication. Researchers (Aslam, 2006; Cheng et al., 2009) report that marketers recognize the power of colour in visual communication, hence they utilize it in their online marketing to increase sales. Berens (2014) reveals that the perception which people have about colour, its combinations, as well as colour memory are not universal among people, rather, they are determined largely by the language people speak, their cultural values and orientation, as well as their environment and gender. Berens further did a study to ascertain the effect of colour and found out that colour has a significant effect on peoples’ emotions, influences their behaviour, as well as how they feel. Berens particularly reported that colours that are bright, saturated, and of long wavelength are likely to be more stimulating and arousing than less saturated, darker, and shorter wavelengths of light. Guéguen and Jacob (2014) examined how colour impact on the looks of workers in the hospitality industry and reported that colour significantly impact on the beauty of waitresses, with waitresses who dress in red looking more beautiful than their counterparts who dress in other colours. Based on their result, the researchers concluded that colour significantly impact on the beauty of workers in hotels. Bagchi and Cheema (2013) examined the effect of background colour and the willingness to pay during auctions and negotiations. The researchers collected data online and reported that background colour plays an essential role in influencing the behaviour of people. Although these studies have provided evidence on the effect of colour, the researchers did not conduct studies within the context of health promotion. The current study extends literature in this direction by examining how colour of cartoons moderate the effect of COVID-19 animated cartoons on social media users. Based on the above studies, the researchers hypothesized:

H1: Colour will significantly predict recall of YouTube animated cartoons on COVID-19.

H2: Colour will significantly moderate impact of COVID-19 YouTube animated cartoons on health behaviour of social media users.

Social media and health promotion

It will not be too hasty to assert that we are now in a social media dominated era. This is largely because of the fundamental roles that social media platforms are now playing in our lives. In addition to changing the way people interact, social media platforms have also made communication affordable and available to everyone. Message options have equally been widened as a result of social media. For example, message elements can now include text, video, illustrations, voice, and picture among others. These elements can as well be combined. Animated cartoons are good examples of current diversity in message elements. Social media can be defined as Internet-based communication platforms that are based on the ideology of web 2.0. Such Internet-based media allow for instantaneous exchange of information in a manner that allows persons involved to serve as sender and receiver at the same time. Researchers (Ugwuanyi et al., 2019; Wogu et al., 2019; Gever & Okoro, 2020) are in consensus that social media platforms are evident of advancement in technology. Examples of social media platforms include: Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp, YouTube, among others. There is growing acceptance of social media as their usage has continued to grow globally. Figures put together by Smart Insight (Smart Insight 2019) revealed that as at 2019, the total number of Internet users reached 4.388 billion people. This figure suggests an increase of 9.1% year-on-year. The data further showed that the global statistics of social media users was 3.484, implying an increase of 9% year-on-year. In addition, the number of mobile phone users went up by 2% as the number reached 5.112 billion. The situation is the same in Nigeria because the number of social media users has continued to increase. For example, as at 2019, a total of 24 million Nigerians have access to social media accounts. Nigerians also spend an average time of 3 hours, 17 minutes on social media. This duration is higher than the global average of 3 hours, 14 minutes (Pulse, 2019). The social media platforms have been found useful in health promotion in the areas of awareness creation, health education, and behaviour change. Zühlke and Engel (2013) aver that awareness is an essential strategy in public health education, and control. Seymour (2018) holds the view that awareness is critical for health promotion. Lyson et al. (2019) investigated the utilization of social media platforms as channels to create awareness and reported that social media platforms are important for health awareness creation.

In addition to awareness, social media platforms also have been found useful for education efforts. This is because through the instrument of social media, people will gain knowledge about the symptoms of diseases, the causes, treatments, as well as preventive measures. Gough et al. (2017) conducted a study and reported that social media use results to improvements in knowledge of health issues. From the discussion above, evidence point to the fact that social media results to improved awareness and knowledge of health issues. However, the issues of exposure and recall were not substantially considered and linked to awareness and knowledge. This is because when social media users are exposed to health messages and they recall it, it is likely to result to higher level of knowledge of the health issue. Consequently, the researchers hypothesized:

H3: Exposure to COVID-19 YouTube animated cartoons will significantly predict knowledge of the virus.

Health behaviour in the social media era

Change in behaviour is one of the driving forces for health promotions. Each time there is a health promotion effort, it is premise on the fact that people need to adapt to certain health behaviour as preventive measures. Health behaviour can be broadly classified into two namely: positive health behaviour and negative health behaviour. Within the context of health promotion, behaviour that exposes a person to the risk of contracting disease and is at variance with healthy living is called negative health behaviour. On the other hand, behaviour that makes a person less vulnerable to contracting disease is called positive health behaviour. Conner (2002) corroborates that in explaining health behaviour, it is helpful to offer a dichotomy between health enhancing behaviour and health impairing behaviour. Conner says that health enhancing behaviour promotes safety of those who engaged in it whereas health impairing behaviour has negative consequences on health or exposes individuals to disease. In this study, attention was paid to health enhancing behaviour like: regular hand washing, use of face mask, use of alcohol-based hand sanitizers, physical distancing, among others. WHO (2020b) notes that appropriate health behaviour is one of the surest ways of ending the carnage of COVID-19 globally. Laranjo et al. (2015) conducted a study with a view to understanding how social media influences health behaviour. Their results point to the fact that social media interventions are significantly associated with change in health behaviour. Ikpi and Undelikwo (2019) did a study to ascertain if social media utilization is linked to health behaviour using a student sample in Nigeria. Their result revealed that social media utilization is significantly correlated with health behaviour. One aspect which has rarely been considered by previous researchers is that of recall. When social media users are exposed to health messages, they need to recall the contents so that they will be able to modify their health behaviour. Based on this assumption, the researchers hypothesized:

H4: Recall of messages theme in COVID-19 YouTube animated cartoons significantly predicts health behaviour of social media users.

Theoretical framework

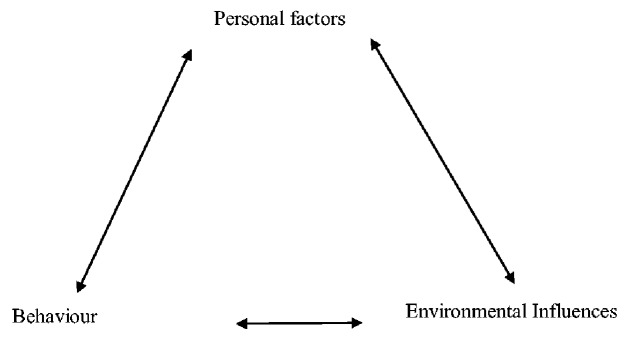

The theoretical framework that was used in this study was social cognitive theory. The theory was suggested by Bandura (Bandura 1986). The fundamental assumption of the theory is that people adopt new bahviour better when they observe others demonstrate it. Animated cartoons on COVID-19 usually demonstrate the desired health behaviour for social media users to learn through observation. This is unlike other health messages like written texts of still pictures. Bandura (2001) notes that SCT is appropriate for examining health behaviour; this is because of the interactions between individual, their environment, and behaviour, with a corresponding implication on healthy living. The interaction that occurs between the people, their environment and behaviour is illustrated below:

Figure 1 below explains the interaction among the components of social cognitive theory.

Fig. 1:

Interaction among the dynamics of the theory.

The theory has some construct which assist in explaining its assumptions. Among these constructs are: self-efficacy, which describes the belief that a person has concerning his or her ability to effectively carry out a particular behaviour and get the needed results. Shamizadeh et al. (2019) avers that self-efficacy is an essential requirement for behaviour modification. The theory equally has task as another fundamental construct. It describes the confidence that a person has to carry out an action. Other constructs of the theory include: planning, coping self-efficacy, goal setting, and outcome expectancy. On the other hand, coping self-efficacy is the confidence that a person has when executing a task under a challenging circumstance. Goal setting is the desired outcome and it helps to improve self-regulation, which has an impact on self-efficacy. In addition, outcome expectancy describes beliefs that are linked to a certain behaviour which results to definite outcome (Bandura, 1991, 1998; Young et al., 2014). Although SCT has been applied to examine how it is linked to health behaviour, researchers hardly consider this theory within the context of health behaviour sustainability. In the current study, we filled this gap as we hypothesized:

H5: Self-efficacy, task self-efficacy, coping self-efficacy, goal setting, and outcome expectancy will significantly predict health behaviour sustainability among social media users who are exposed to COVID-19 YouTube animated cartoon.

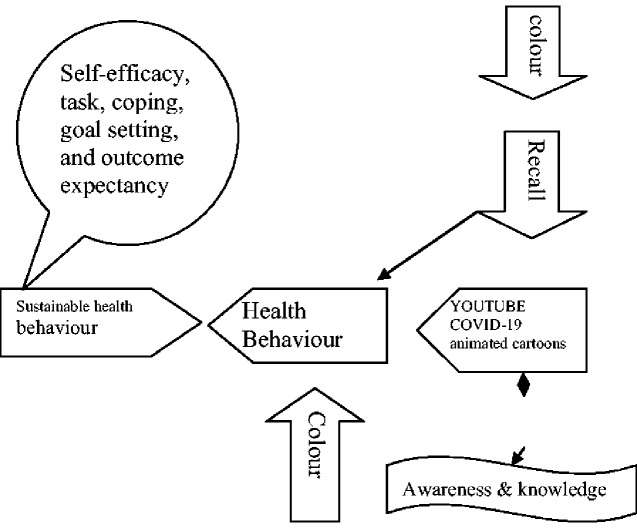

The four hypotheses in this study are presented in a model as illustrated below:

Figure 2 above presents the study model. It was hypothesized that: cartoon colour will significantly predict recall of YouTube animated cartoons on COVID-19; cartoon colour will significantly moderate impact of COVID-19 YouTube animated cartoons on health behaviour of social media users; exposure to COVID-19 YouTube animated cartoons will significantly predict awareness and knowledge of the virus; recall of messages theme in COVID-19 YouTube animated cartoons significantly predict health behaviour of social media users and finally, self-efficacy, task self-efficacy, coping self-efficacy, goal setting, and outcome expectancy will significantly predict health behaviour sustainability among social media users who are exposed to COVID-19 YouTube animated cartoon.

Fig. 2:

Study model.

MATERIALS AND METHOD

To conduct this study, the researchers made use of survey research design to be able to explain and describe the moderating role of colour on the impact of COVID-19 YouTube animated cartoons on health behaviour of social media users in Nigeria. All the social media users in Nigeria constituted the population for the study. Nigeria currently has a total of 24 million social media users (Pulse, 2019). The researchers did a priori power analysis to determine the sample size that was sufficient for the study. We utilized G*power program (Faul et al., 2007) and the parameters were power (1−β) at 0.90, 0.30 effect size f, and α=0.05. The outcome of the priori power analysis showed that 470 sample of social media users were needed to measure statistical differences at 0.05. This means that the sample size for the study was 470. We utilized respondent-driven sampling (RDS) chain referrals [see (Heckathorn, 2002; Johnston et al., 2008)] to select a sample for the study. Usually, RDS begins by sampling initial participants known as ‘seeds’. The researchers selected the seeds through Facebook announcements that were pasted on the Facebook pages of all the researchers. Interested persons were told to contact any of the researchers through personal messages for participation. The ‘seeds’ are required to have characteristics of interest. Social media users were the seeds for the study. The initial seeds further recruited persons from their existing network for participation in the study. This process continued until the needed number of participants was sampled. The instrument for data collection in this study was the questionnaire which was developed by the researchers. There was an introductory question on the questionnaire that sought to ascertain if respondents were exposed to YouTube animated cartoons on COVID-19 or not. Only respondents who indicated ‘yes’ were able to proceed to fill the questionnaire. The response format for the questionnaire was a combination of multiple option and four-point likert scale. The researchers collected data for the study using a time frame of two weeks. A total of three experts were contacted to validate the questionnaire. The views of the experts were used to prepare a final draft of the questionnaire. Concerning reliability, the researchers made use of test re-test approach using two weeks interval. The correlation coefficient was 0.89, suggesting that the instrument was reliable. The researchers made use of descriptive statistics like simple percentages and mean to analyse the result for the study. In addition, inferential statistics like multiple regression analysis and multiple hierarchical regressions were used to test the hypotheses for the study. All the analysis was carried out with the utilization of SPSS version 22. Tables were used to present the results.

RESULTS

The chain referral sampling yielded the required sample size of 470 social media users who equally said that they were exposed to COVID-19 YouTube animated cartoons. There was no significantly statistical difference among the age (p>0.05), education (p>0.05), gender (p>0.05), and years of experience (p >0.05) with social media. The result of the study is presented in accordance with the hypotheses of the study as shown below:

H1: Colour will significantly predict recall of YouTube animated cartoons messages on COVID-19.

In Table 1 below, the researcher examined colour as a predictor of recall of COVID-19 YouTube animated cartoon messages. It was found that while bright, saturated, and long wavelength colours are likely to enhance recall, less saturated, darker, and shorter wavelengths of light are less likely to enhance recall. The first assumption was supported and the researchers concluded with 95% confidence that cartoon colour play a significant role in enhancing message recall among social media users in Nigeria.

H2: Colour will significantly moderate impact of COVID-19 YouTube animated cartoons on health behaviour of social media users.

Table 1:

Regression analysis of colour as predictors of recall of COVID-19 YouTube animated cartoons

| Colour | Constant | β value | R 2 | F-value | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bright colour | 3.121 | 0.513 | 0.407 | 12.2039 | 0.002** |

| Saturated colour | 0.509 | 0.001** | |||

| long wavelength colour | 0.403 | 0.002** | |||

| less saturated | 0.201 | 0.123* | |||

| Darker colour | 0.108 | 0.203* | |||

| Short wavelength colour | 0.128 | 0.432* |

Note: **Significant; *insignificant.

In Table 2 below, a hierarchical multiple regression model was computed to ascertain the capacity of COVID-19 YouTube animated cartoons to predict health behaviour of social media users. Therefore, we first entered exposure to COVID-19 YouTube animated cartoons and this accounted for 9% variance in health berhaviour of the respondents. After adding colour at step 2, the total variance explained by the model as a whole was 73%, F (2,421)=13 473, p ≤ 0.001. Therefore, we conclude that colour significantly moderate the impact of COVID-19 YouTube animated cartoons on health behaviour like regular hand washing, use of alcohol-based hand sanitizers, use of face mask, physical distancing, and avoiding handshake. The second assumption was also supported.

Table 2:

Hierarchical regression analysis of the moderating effect of colour on the influence of COVID-19 YouTube animated cartoons on health behaviour

| Socialmedia use | R 2 | R 2 change | F-value | Fchange | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | 0.091 | 0.73 | 2,421 | 2,421 | 0.001 |

| Model 2 | 0.578 | 0.539 | 8,719 | 13 473 | 0.001 |

Table 5:

Regression analysis of self-efficacy, task self-efficacy, coping self-efficacy, goal setting, and outcome expectancy as predictors of health behaviour sustainability of social media users who are exposed to COVID-19 YouTube animated cartoon

| Colour | Constant | β value | R 2 | F-value | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-efficacy | 3.920 | 0.509 | 0.415 | 14.223 | 0.001** |

| Task self-efficacy | 0.521 | 0.001** | |||

| Coping self-efficacy | 0.803 | 0.002** | |||

| Goal setting | 0.201 | 0.113* | |||

| Outcome expectancy | 0.401 | 0.003* |

Note: **Significant; *insignificant.

H3: Exposure to COVID-19 YouTube animated cartoons will significantly predict knowledge of the virus.

In Table 3 below, a multiple regression was conducted to ascertain if exposure to COVID-19 YouTube animated cartoons significantly predict knowledge of the virus. It was found that the analysis yielded an overall p-value of 0.001 with R. Square value of 0.574. This means that our model explains 57% variance in predicting knowledge of COVID-19 as a result of exposure to YouTube animated cartoons. We further found that irregular exposure did not contribute in predicting knowledge of the virus such as: how it is contracted, ways of preventing it, as well as its symptoms. Furthermore, it was found that daily exposure contributed more (β=0.702) in predicting knowledge of the virus. The result of the study supports the third assumption of the study.

H4: Recall of messages theme in COVID-19 YouTube animated cartoons significantly predicts health behaviour of social media users.

Table 3:

Regression analysis of exposure to COVID-19 YouTube animated cartoons as predictors of knowledge of the virus

| Exposure | Constant | β-value | R 2 | F-value | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Irregular | 4.421 | 0.242 | 0.574 | 12.442 | 0.122 |

| 1–3 times weekly | 0.193 | 0.002 | |||

| Daily | 0.702 | 0.001 |

The objective of Table 4 below was to determine if three levels of message recall predict health behaviour of social media users who are exposed to COVID-19 YouTube animated cartoons. The outcome of the analysis yielded p-value of 0.001 with R. Square value of 0.524, an indication that the model explains 52% variance in predicting health behaviour of the respondents as a result of recall of COVID-19 YouTube animated cartoons. However, low recall did not significantly contribute to change in health behaviour whereas high recall was found to have contributed more (β=0.801) in predicting knowledge of the virus. The result of the study supports the fourth assumption of the study.

Table 4:

Regression analysis of recall of COVID-19 YouTube animated cartoons as predictors of health behaviour

| Exposure | Constant | β value | R 2 | F-value | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low recall | 3.223 | 0.291 | 0.524 | 13.142 | 0.120 |

| Moderate recall | 0.191 | 0.002 | |||

| High recall | 0.801 | 0.001 |

H5: Self-efficacy, task self-efficacy, coping self-efficacy, goal setting, and outcome expectancy will significantly predict health behaviour sustainability among social media users who are exposed to COVID-19 YouTube animated cartoon.

Table 5 below examined self-efficacy, task self-efficacy, coping self-efficacy, goal setting, and outcome expectancy as predictors of health behaviour sustainability among social media users who are exposed to COVID-19 YouTube animated cartoon. It was found that apart from goal setting, all the other predictors examined were found to significantly predict health behaviour sustainability. Further analysis point to the fact that coping self-efficacy (β=0.803) had the highest beta value, an indication that it contributes more in health behaviour sustainability vis-à-vis COVID-19. The last assumption was partly supported as goal setting did not significantly predict health behaviour sustainability.

Discussion of findings

In this study, we examined the moderating role of colour in a model that explains the impact of COVID-19 YouTube animated cartoons on health behaviour of social media users in Nigeria. Specifically, we hypothesized that colour will significantly predict recall of YouTube animated cartoons on COVID-19. This assumption was supported and we found that bright and saturated colours with long wavelength are better in enhancing recall of YouTube animated cartoons than darker, dull, and short wavelength colours. It was also found that colour significantly moderates the impact of COVID-19 YouTube animated cartoons on health behaviour of social media users. This aspect of the finding has extended the study of Berens (2014); Guéguen and Jacob (2014); Bagchi and Cheema (2013); Maranzana (2014); Rai et al. (2016) who examined the impact of colour on perception without paying attention to health messages. This addition is important because it has offered fresh information that will shape future debates on the impact of colour in visual communication. Additionally, the current study examined the role of colour within the context of animated cartoons. This is an aspect that has not been sufficiently examined by previous researchers (Abraham, 2009; Onakpa, 2014; Onuora et al., 2020) that examined the impact of cartoons on behaviour change. In this direction, the current study has also extended argument on the impact of cartoons by also looking at how cartoon elements like colour plays a role on its effectiveness.

In addition,it washypothesized that exposure to COVID-19 YouTube animated cartoons will significantly predict knowledge of the virus. The result of the current study supported that assumption. This means that the more people are exposed to animated cartoons such as daily, the more the likelihood that they will have sufficient knowledge about the virus. In addition, we found that recall of messages theme in COVID-19 YouTube animated cartoons significantly predict health behaviour of social media users. The areas (exposure and recall) have not sufficiently been investigated by other researchers (Ugwuanyi et al., 2019; Wogu et al., 2019; Gever & Okoro, 2020) who investigated the impact of social media on behaviour. Such an omission may not offer sufficient guide on how to utilize social media for behaviour change communication. Even studies (Gough et al., 2017; Lyson et al., 2019) that examined the use of social media for health campaign, sufficient attention was not paid to the issue of exposure and recall.

Finally, the result of the current study showed that self-efficacy, task self-efficacy, coping self-efficacy and outcome expectancy significantly predict health behaviour sustainability among social media users who are exposed to COVID-19 YouTube animated cartoon. However, goal setting did not significantly predict health behaviour sustainability. The outcome of the current study has extended previous studies by researchers that have examined health behaviour (Conner, 2002; Laranjo et al., 2014; Ikpi and Undelikwo, 2019) without looking at the sustenance of the behaviour. It is one thing to engage in a behaviour, it is another thing to sustain that behaviour. This is an aspect that has rarely been investigated even by researchers (Bandura, 1991, 1998; Young et al., 2014; Shamizadeh et al., 2019) that examined the social cognitive theory to investigate health behaviour. Therefore, this study has provided a fresh perspective to the social cognitive theory by showing that its constructs can be utilized to examine health behaviour sustainability.

CONCLUSION

Our conclusion in this study is that colour plays a significant moderating role on the effectiveness of animated cartoons on the health behaviour of social media users in Nigeria. It is also our conclusion that colour enhances message recall while recall also plays a role on message effectiveness. Additionally, it is concluded that exposure predict knowledge while self-efficacy, task self-efficacy, coping self-efficacy, goal setting, and outcome expectancy will significantly predict health behaviour sustainability among social media users who are exposed to COVID-19 YouTube animated cartoon. This study has made contribution to literature as well as theory, and practice. In the area of literature, the current study has extended previous studies in three areas. First, it has provided information on the moderating role of colour on the effectiveness of animated cartoons. In the second place, it has provided information on the important role of colour on message recall, and lastly, it has shown predictors of health behaviour sustainability. Concerning theory, the current study has shown how constructs from social cognitive theory can be used to explain health behaviour sustainability. This is an aspect that has not been examined, especially from the perspective of developing countries. The result also has implications on health education practice by showing how new media and elements of visual communication can be combined during public health emergency.

Implications on health promotion

The result of this study has four broad implications on health promotion in the following ways:

First, it means that health promotions experts can creatively deploy animated cartoons during public health emergencies with a view to educating the masses on the health issues.

Social media in general and YouTube are effective platforms for health promotions.

The result equally makes a strong case for the use of bright, saturated and long wavelength colours in health promotions regarding public health issues.

Construct from social cognitive theory can offer a reliable way of ensuring sustainability in health behaviour.

Limitation/suggestion for further study

Despite the above contributions, the current study has some limitations. The first limitation is that the researchers made use of survey. Therefore, the impact of colour and health behaviour was based on the reported views of the respondents. Another limitation of the study is the use of only one social media platform. There may be a need to also examine other social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and WhatsApp for better understanding. In addition, the current study did not provide information on how colour was differentiated form other visual artifacts. Therefore, the researchers recommend that further studies should address these limitations.

REFERENCES

- Abraham L. (2009) Effectiveness of cartoons as a uniquely visual medium for orienting social issues.

- Ale V. (2020) A library-based model for explaining information exchange on coronavirus disease in Nigeria. Ianna Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies, 2, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Aslam M. (2006) Are you selling the right colour? A cross‐cultural review of colour as a marketing cue. Journal of Marketing Communications, 12, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Bagchi R., Cheema A. (2013) The effect of red background color on willingness-to-pay: the moderating role of selling mechanism. Journal of Consumer Research, 39, 947–980. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. (1991) Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50, 248–287. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. (2001) Social cognitive theory: an agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 1–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. (1998) Health promotion from the perspective of social cognitive theory. Psychology & Health, 13, 623–649. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. (1986) Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Prentice-Hall, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- Berens J. (2014) The Role of Colour in Films: Influencing the Audience’s Mood. https://www.danberens.co.uk/uploads/3/0/0/6/30067935/daniel_berens_dissertation_may2014.pdf (last accessed 20 November 2020).

- Brown S., Street S., Watkins L. (2013) Color and the Moving Image: History, Theory, Aesthetics, Archive: Routledge, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng F., Chin-Shan W., David Y. (2009) The effect of online store atmosphere on consumer’s emotional responses—an experimental study of music and colour. Behaviour & Information Technology, 28, 323–334. [Google Scholar]

- Conner M. (2002) Health Behaviors.http://userpage.fu-berlin.de/∼schuez/folien/conner2002.pdf.

- Ezeah G., Okwumba E., Ohia C., Gever V. C. (2020) Measuring the effect of interpersonal communication on awareness and knowledge of COVID-19 among rural communities in Eastern Nigeria. Health Education Research, 35, 481–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faul F., Erdfelder E., Buchner A. and Lang A. G. (2007) G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39, 175–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gever V., Okoro N. (2020) Influence of Facebook users’ self-presentation tactics on their response to persuasive political messages. LibraryPhilosophy and Practice,1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Gever V. C., Ezeah G. (2020) The media and health education: did Nigerian media provide sufficient warning messages on Coronavirus disease? Health Education Research, 35, 460–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gough A., Hunter R. F., Ajao O., Jurek A., McKeown G., Hong J. et al. (2017) Tweet for behavior change: using social media for the dissemination of public health Messages. Jmir Public Health and Surveillance, 3, e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guéguen N., Jacob C. (2014) Clothing color and tipping: gentlemen patrons give more tips to waitresses with red clothes. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 38, 275–280. [Google Scholar]

- Heckathorn D. (2002) Respondent-driven sampling II. Deriving valid population estimates from chain-referral samples of hidden populations. Social Problems, 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Ikpi N., Undelikwo V. (2019) Social media use and students’ health-lifestyle modification in University of Calabar, Nigeria. European Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies, 5, 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- James J., Ghai S., Rao K., Sharma N. (2012) Effectiveness of animated cartoons as a distraction strategy on behavioural response to pain perception among children undergoing venipuncture. Nursing and Midwifery Research Journal, 8, 198–209. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston L. G., Malekinejad M., Kendall C., Iuppa I. M. and Rutherford G. W. (2008) Implementation Challenges to Using Respondent-Driven Sampling Methodology for HIV Biological and Behavioral Surveillance: Field Experiences in International Settings. AIDS AND Behavior, 12, 131–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhbandner C., Pekrun R. (2013) Joint effects of emotion and color on memory. American Psychological Association, 13 (3), 375–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laranjo L., Arguel A., Neves A. L., Gallagher A. M., Kaplan R., Mortimer N et al. (2015) The influence of social networking sites on health behavior change: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 22, 243–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H., Park J., Lee J. (2020) Comparison between psychological responses to “object colour produced by paint colour” and “object colour produced by light source”. Indoor and Built Environment, 1420326X1989710. [Google Scholar]

- Lyson H. C., Le G. M., Zhang J., Rivadeneira N., Lyles C., Radcliffe K. et al. (2019) Social media as a tool to promote health awareness: results from an Online Cervical Cancer Prevention Study. Journal of Cancer Education, 34, 819–822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maranzana S. (2014) Using YouTube to Enhance l2 Listening Skills: Animated Cartoonsin the Italian Classroom.https://repository.arizona.edu/handle/10150/604160 (last accessed 20 November 2020).

- Melugbo D., Ogbuakanne M., Jemisenia J. (2020) Entrepreneurial potential self-assessment in times of COVID-19: assessing readiness, involvement, motivation and limitations among young adults in Nigeria. Ianna Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies, 2, 12–28. [Google Scholar]

- Michelsen E. (2009) Animated Cartoons, from the Old to the New: Evolution for the Past 100 Years. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.461.791&rep=rep1&type=pdf (last accessed 20 November 2020).

- Marcus M., Roberts N., Bauld L., Ute L. (2011) Plain packaging increases visual attention to health warnings on cigarette packs in non-smokers and weekly smokers but not daily smokers. Addiction, 106, 1505–1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odii A., Ngwu O., Aniakor C., Owelle C., Aniagboso C., Uzuanwu W. (2020) Effect of COVID-19 lockdown on poor urban households in Nigeria: where do we go from here? Ianna Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies, 2, 75–85. [Google Scholar]

- Onakpa M. (2014) Cartoons, cartoonists and effective communication in the Nigeria print media. African Research Review, 8, 32–41. [Google Scholar]

- Onuora C., Ezeah G., Obasi N., Gever V. C. (2020) Effect of dramatized health messages: modeling predictors of the impact of COVID-19 YouTube animated cartoons on health behaviour of social media users in Nigeria. International Sociology, 36, 124–140. [Google Scholar]

- Oyero O., Oyesomi O. (2014) Perceived Influence of Television Cartoons on Nigerian Children’s Social Behaviour. http://www.ec.ubi.pt/ec/17/pdf/n17a05.pdf (last accessed 20 November 2020).

- Pulse (2019) HereisHowNigeriansareusingtheInternetin2019. https://www.pulse.ng/bi/tech/hownigeriansareusingtheinternetin2019/kz097rg (last accessed 20 November 2020).

- Rai R., Waskel B., Sakalle S., Dixit S., Mahore R. (2016) Effects of cartoon programs on behavioural, habitual and communicative changes in children. International Journal of Community Medicine and Public Health, 3, 1375–1378. [Google Scholar]

- Seymour J. (2018) The Impact of public health awareness campaigns on the awareness and quality of palliative care. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 21, S-30–S-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamizadeh T., Jahangiry L., Sarbakhsh P., Ponnet K. (2019) Social cognitive theory-based intervention to promote physical activity among prediabetic rural people: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Trials, 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smart Insight (2019) Global Social Media Research Summary 2019. https://www.smartinsights.com/social-media-marketing/social-media-strategy/new-global-social-media-research/

- Ugwuanyi C., Gever V. C., Olijo I. (2019) Social media as tools for political views expressed in the visuals Shared among social media users. Library Philosophy and Practice, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Wogu J., Ezeah G., Gever V. C., Ugwuanyi C. (2019) Politicking in the digital Age: engagement in computer-mediated political communication and citizens’ perception of political parties, politicians and the government. LibraryPhilosophy and Practice, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2020a) Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Report—66. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200326-sitrep-66-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=81b94e61_2 (last accessed 20 November 2020).

- World Health Organization (2020b) WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. https://covid19.who.int/?gclid=CjwKCAjwmf_4BRABEiwAGhDfSfDYZXDsfK0BEdjfjyRnp5oqMEho45w2fgaL4zUYNU0enWXgW2CAQRoCoH0QAvD_BwE (last accessed 20 November 2020).

- Wu Y. C., Chen C. S., Chan Y. J. (2020) The outbreak of COVID-19: an overview. Journal of the Chinese Medical Association, 83, 217–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang B., Wei M. (2020) Road lighting: a pilot study investigating improvement of visual performance using light sources with a larger gamut area. Lighting Research and Technology, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Young M. D., Plotnikoff R. C., Collins C. E., Callister R., Morgan P. J. (2014) Social cognitive theory and physical activity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity Reviews, 15, 983–995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zühlke L. J., Engel M. E. (2013) The importance of awareness and education in prevention and control of Rhd. Global Heart, 8, 235–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]