Abstract

The Corona pandemic poses major demands for long-term care, which might have impacted the intention to quit the profession among managers of long-term care facilities. We used cross-sectional data of an online survey of long-term care managers from outpatient and inpatient nursing and palliative care facilities surveyed in April 2020 (survey cycle one; n = 532) and between December 2020 and January 2021 (survey cycle two; n = 301). The results show a significant association between the perceived pandemic-specific and general demands and the intention to leave the profession. This association was significantly stronger for general demands in survey cycle two compared with survey cycle one. The results highlight the pandemic’s immediate impact on long-term care. In view of the increasing number of people in need of care and the already existing scarcity of specialized nursing staff, the results highlight the need for initiatives to ensure the provision of long-term care, also and especially in such times of crisis.

Keywords: carers, management and policy, work environment

Introduction

The Corona pandemic poses major demands for long-term care. Inpatient nursing care facilities and hospices face a variety of demands such as visiting and contact bans, isolation and separation of SARS-CoV-2 infected patients, extended use and reuse of personal protective equipment, and fears of infections.1,2 The same applies to outpatient nursing and palliative care facilities which are affected by different demands such as corona precautions at close range, and hygiene and distance requirements.1,2 Accordingly, international studies indicate higher risks of mental and physical health burdens among health care workers during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.3,4 These demands are accompanied by a number of other challenges affecting German long-term care facilities in general such as the discrepancy between the availability and need for nursing specialist or individual performance and remuneration.5,6 This results in a continuously high sense of stress and occupational illnesses, and an early exit from the job among the nursing workforce.5 In this study, we examine the relationship between long-term care managers’ intentions to quit their profession and demands that affect long-term care facilities during the Corona pandemic.

Methods

Study population and analytical sample

We used cross-sectional data of an online survey of long-term care managers from outpatient and inpatient nursing and palliative care facilities surveyed in April 2020 (first survey) and between December 2020 and January 2021 (second survey). For the first survey cycle, of 4333 eligible managers, 765 participated in the survey, of which 533 fully and 207 partly completed, and 25 did not agree to be interviewed. For the second survey cycle, of 4185 eligible managers, 520 participated in the survey, of which 299 fully and 192 partly completed, and 29 did not agree to be interviewed. The analytical sample consisted of 532 managers at the first survey cycle and 301 managers at the second survey cycle after the exclusion of cases with missing information.

Measurements

Intention to quit the profession was measured by asking managers to indicate how often they have considered quitting their profession since the outbreak of the pandemic: ‘Since the outbreak of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, how many times have you considered quitting your profession?’. From this item, we created a dichotomous outcome measure (never/seldom/sometimes versus often/very often).

Demands of long-term care facilities were separated into pandemic-specific and general demands. Pandemic-specific demands consisted of 10 items (see, Supplementary Table 1) and were assessed via the following question: ‘What demands have affected your organization since the outbreak of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic and to what extent do they distressed you?’ The items showed a high internal consistency reliability (cronbachs α: 0.81). The general demands consisted of 12 items (see, Supplementary Table 1) and were assessed via the following question: ‘What other demands affects your organization currently and to what extent do they distressed you?’ The items showed a high internal consistency reliability (cronbachs α: 0.86). The response categories for items of the pandemic-specific and general demands were ‘No, does not affect us’, ‘Yes, but does not distressed us’, ‘Yes, distressed us moderately’, ‘Yes, distressed us strongly’ and ‘Yes, distressed us very strongly’. For the analyses, an additive score of pandemic-specific and general demands were created and standardized on a 0–100 scale with higher values indicating higher levels of demands.

Control variables were age groups, gender, direct involvement in nursing care, state, total number of patients in care and organizational type. Sample characteristics are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics by survey cycle

| First survey cycle | Second survey cycle | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total n (%) | 532 | (100%) | 301 | (100%) |

| Intention to quit the profession n (%) | ||||

| never/seldom/sometimes | 464 | (87.2%) | 240 | (79.7%) |

| often/very often | 68 | (12.8%) | 61 | (20.3%) |

| Pandemic-specific demands mean (sd) | 64.6 | (15.5) | 67.9 | (15.2) |

| General demands mean (sd) | 55.5 | (15.2) | 60.4 | (16.4) |

| Age groups n (%) | ||||

| <26 years | 48 | (9%) | 25 | (8%) |

| 26–35 years | 140 | (26%) | 82 | (27%) |

| 26–45 years | 196 | (37%) | 102 | (34%) |

| 46–55 years | 142 | (27%) | 89 | (30%) |

| >65 years | 6 | (1%) | 3 | (1%) |

| Gender n (%) | ||||

| male | 176 | (33%) | 94 | (31%) |

| female | 356 | (67%) | 207 | (69%) |

| Activity status in patient care n (%) | ||||

| active | 249 | (47%) | 110 | (36%) |

| not active | 283 | (53%) | 191 | (64%) |

| Organization type n (%) | ||||

| inpatient care facility | 106 | (20%) | 73 | (24%) |

| hospice | 16 | (3%) | 8 | (3%) |

| outpatient care service | 348 | (65%) | 197 | (65%) |

| outpatient hospice service | 25 | (5%) | 9 | (3%) |

| others | 37 | (7%) | 14 | (5%) |

| State n (%) | ||||

| Baden-Wuerttemberg | 53 | (10%) | 30 | (10%) |

| Bavaria | 73 | (14%) | 43 | (14%) |

| Berlin | 6 | (1%) | 7 | (2%) |

| Brandenburg | 15 | (3%) | 4 | (1%) |

| Bremen | 8 | (2%) | 3 | (1%) |

| Hamburg | 12 | (2%) | 12 | (4%) |

| Hesse | 92 | (17%) | 50 | (17%) |

| Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania | 7 | (1%) | 3 | (1%) |

| Lower Saxony | 38 | (7%) | 21 | (7%) |

| North Rhine-Westphalia | 109 | (20%) | 69 | (23%) |

| Rhineland-Palatinate | 33 | (6%) | 18 | (6%) |

| Saarland | 6 | (1%) | 2 | (1%) |

| Saxony | 30 | (6%) | 17 | (6%) |

| Saxony-Anhalt | 13 | (2%) | 2 | (1%) |

| Schleswig-Holstein | 19 | (4%) | 10 | (3%) |

| Thuringia | 18 | (3%) | 10 | (3%) |

| Total number of patients in care mean (sd) | 116.0 | (250.0) | 135.0 | (261.9) |

Statistical analyses

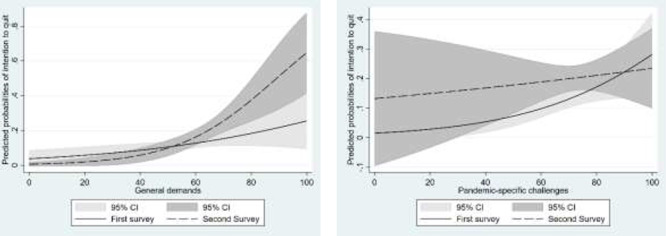

Descriptive analyses and multivariate logistic regression analyses for the prediction of intention to quit the profession by pandemic-specific and general demands of care long-term facilities, survey cycle, an interaction term between demands and survey cycle, and the control variables were performed in Stata V.16.0 (StataCorp 2019). From the logged odds obtained in the regression analyses, we calculated predicted probabilities of intention to quit the profession for the first and second survey cycle by pandemic-specific and general demands.7

Results

Intention to quit the profession often or very often since the outbreak of the pandemic increased significantly (P = 0.004) from 12.8% in survey cycle one to 20.3% in survey cycle two. Similarly, the perceived extent of demands increased between the two survey cycles. Mean levels of pandemic-specific demands significantly (P = 0.004) rose from 64.6 to 67.9, and mean levels of general demands significantly (P ≤ 0.001) rose from 55.5 to 60.4 between survey cycle one and survey cycle two.

Results from the multivariate logistic regression analysis, including all variables simultaneously, showed that the pandemic-specific demands [OR = 1.034; CI = 1.011–2.057, P = 0.003] and the general demands [OR = 1.023; CI = 1.001–1.045, P = 0.042] were significantly associated with the intention to quit the profession. The interaction term between survey cycle and demands indicated that the association between general demands and the intention to quit the profession significantly rose between survey cycle one and two [OR = 1.036; CI = 1.000–1.072, P = 0.047], whereas the association between pandemic specific demands and intention to quit the profession did not significantly vary by survey cycle [OR = 0.975; CI = 0.940–1.012, P = 0.182]. Accordingly, in Fig. 1, predicted probabilities of intention to quit the profession increased with higher levels of pandemic-specific and general demands and rose stronger in survey cycle two for general demands. Survey cycle, age, gender, direct involvement in nursing care, state, total number of patients in care and organizational type were not significantly associated with the intention to quit the profession (see, Supplementary Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Predicted probabilities of intention to quit the profession for the first and second survey cycle by pandemic-specific and general demands.

Discussion

This study found that intention to quit the profession among German managers of long-term care facilities has significantly increased during the SARS-CoV-2-pandemic. In the same time period, the perceived general demands as well as those directly related to the pandemic have increased significantly. There was a significant association between intention to quit the profession and pandemic-specific and general demands. The association was stronger in survey cycle two for general demands. Results might be affected by a selection bias due to time constraints of nursing care managers in light of the current demands or due to a greater motivation to participate by those managers who felt more likely to be affected by the current demands. The current analyses should be continued over time in future studies, should also focus on staff nurses and should consider the actual quitting behavior of managers and staff nurses.

Supplementary Material

Timo-Kolja Pförtner, Research Associate

Holger Pfaff, Professor and Head

Kira Isabel Hower, Research Associate

Contributor Information

Timo-Kolja Pförtner, Institute of Medical Sociology, Health Services Research, and Rehabilitation Science, Faculty of Human Sciences and Faculty of Medicine, University of Cologne, Cologne, DE-50933 Germany.

Holger Pfaff, Institute of Medical Sociology, Health Services Research, and Rehabilitation Science, Faculty of Human Sciences and Faculty of Medicine, University of Cologne, Cologne, DE-50933 Germany.

Kira Isabel Hower, Institute of Medical Sociology, Health Services Research, and Rehabilitation Science, Faculty of Human Sciences and Faculty of Medicine, University of Cologne, Cologne, DE-50933 Germany.

Funding

This work was supported by the German Research Foundation in connection with the research project ‘Forms of precarious employment and subjective health’ in Germany (grant number PF 897/3–1).

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

- 1. Hower KI, Pfaff H, Pförtner T-K. Pflege in Zeiten von COVID-19: Onlinebefragung von Leitungskräften zu Herausforderungen, Belastungen und Bewältigungsstrategien. Pflege 2020;33:207–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Halek M, Reuther S, Schmidt J. Herausforderungen für die pflegerische Versorgung in der stationären Altenhilfe: corona-pandemie 2020. MMW Fortschr Med 2020;162(9):51–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. White EM, Wetle TF, Reddy A, Baier RR. Front-line nursing home staff experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2021;22:199–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. González-Gil MT, González-Blázquez C, Parro-Moreno AI et al. Nurses' perceptions and demands regarding COVID-19 care delivery in critical care units and hospital emergency services. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2021;102966:62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Günther L. Psychische belastungen in Pflegeberufen. In: Ressourcenorientierte Gesundheitsforderung durch die Betriebliche Sozialarbeit. München: GRIN Publishing, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schmucker R. Arbeitsbedingungen in Pflegeberufen. In: Jacobs K, Kuhlmey A, Greß S et al. (eds). Pflege-Report 2019. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2020, 49–60. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Buis ML. Direct and indirect effects in a logit model. Stata J 2010;10(1):11–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.