Abstract

Background:

Both cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) and paroxetine (PX) are the preferred treatments for social anxiety disorder (SAD). However, in literature, there have been divided opinions for the efficacy of the combination of these treatments. This study intended to evaluate whether the combination of CBT and PX would be superior to monotherapy of PX in the treatment of SAD.

Methods:

This was a single centre, rater-blind, non randomised study which included 40 consenting adult participants who received CBT+PX or PX only. The Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale, Social Interaction Anxiety Scale, and Brief Fear of Negative Evaluation scale (BFNE) were assessed at baseline (0 weeks), immediate posttreatment (16–18 weeks for CBT + PX and 16–20 weeks for PX only), and at follow-ups 2 months after posttreatment.

Results:

Both the treatment groups have a statistically significant difference in mean scores in all outcome measures in posttreatment and follow-up stages compared with pretreatment scores. However, CBT + PX has a better treatment and maintenance gain as compared to PX alone in the posttreatment and follow-up stages.

Conclusions:

In SAD management, combinations of CBT + PX are superior to PX alone, and the treatment gains are also better maintained in former than latter.

Keywords: CBT, cognitive behavioral therapy, fear, negative evaluation, nonrandomized, paroxetine, social anxiety disorder

Social anxiety disorder (SAD) is considered to be highly prevalent, with a prevalence that ranges from 8% to 13%.[1] It is a chronic clinical condition that is associated with severe[2] functional impairment. The frontline treatments of SAD include cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)[3] and pharmacotherapy involving selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI)[4,5] like paroxetine (PX) and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs).[6] However, the use of MAOIs has declined due to some potential side effects, food and drug interactions, and the introduction of other classes of drugs.[7] Hence, in general, PX (an SSRI) is preferred pharmacotherapy for the management of SAD in India.[8] Considering the significant findings with CBT of its effectiveness in maintenance of the gains after the end of treatment,[9] a common trend in clinical practice is recommending a combination of both CBT and PX together for SAD.

Despite the reported effectiveness of both pharmacological and cognitive behavioral interventions, the studies involving a combination of these have not shown any substantial improvements in outcome relative to either strategy alone. Some studies[3] found no evidence of combined therapies having better effectiveness than each monotherapy alone. In a study, active treatments of fluoxetine (an SSRI), group CBT, CBT plus fluoxetine, and CBT plus pill placebo are found to have found greater efficacy than pill placebo, but there were no differences among the active treatments.[10] One of the reasons for such could be due to the attenuation of glucocorticoid activity by anxiolytic medications which may interfere with extinction learning[11] in exposure-based therapies; as recent reports have supported the effects of cortisol on learning of emotional material. However, in another study,[4] sertraline, another SSRI, and CBT combination produced greater benefits, suggesting that such combination may enhance treatment in primary care.

Due to such divided opinions in literature, the objective of the current study was to evaluate whether a combination of two efficacious treatments, CBT and PX, with different mechanisms of action, would be superior to monotherapy of PX in the treatment of SAD.

METHODS

This was a single-center, rater-blind, nonrandomized, prospective observational study. The study took place at a tertiary care hospital attached to a medical college. The study was approved by the institutional ethical committee. The study was registered on the ISRCTN registry and the ID is ISRCTN96218088. Informed written consent was obtained from the participants, and their rights and options to opt out were clearly explained to them.

Sampling involved two groups of participants, one receiving CBT + PX and other PX only.

The inclusion criteria for selection of participants were (a) a diagnosis of social phobia (SAD) based on the International Classification of Disease (ICD-10) classification of mental and behavioral disorders: diagnostic criteria for research,[12] (b) informed consent, and (c) minimum 18 years of age. Exclusion criteria were (a) current level of severe depression with suicidal ideation, (b) substance dependence, and (c) comorbid psychosis.

All the consecutive SAD patients attending the study center were assessed and informed about both treatment modalities in SAD. Treatment decisions of PX alone or PX + CBT were taken by the treating team involving consultant psychiatrists and clinical psychologists following discussion with the patients. Patients were given a choice to choose the treatment modalities. The study was undertaken from August 2017 and continued until February 2019 till there were 20 participants in each arm of the study. A final sample of 40 participants was available following 52 screenings for the study. The reasons for nonparticipation were a long distance of travel to the treatment center and three were concerned about the stigma of repeated attendance in psychiatry.

Interventions

CBT was based on Rapee's model for SAD[13] and used metaphor-based conceptualization.[14] The main steps in treatment were as follows (a) cognitive conceptualization, (b) use of cognitive restructuring for the challenging negative thoughts as well as for the coping during exposure/experiments, (c) in-session exposure/behavioral experiments avoiding safety behaviors and comparison with presumed audience standards, (d) extensive homework tasks focusing on both exposure and restructuring, which were reviewed at the beginning of the next session. In the CBT + PX group, each participant was exposed to eight sessions for CBT approximately 60 min. These were delivered by a master level trainee pursuing a master's in philosophy in clinical psychology under the supervision of clinical psychologist with over 5 years of experience of CBT supervision. The other group received PX only. In both the groups, the initial dosage of PX 12.5 mg per day in a controlled release formulation and which later increased upto 50 mg/day. All the participants were followed up and monitored by consultant psychiatrists for the entire duration of the study.

Outcome measures

All included patients were first assessed and diagnosed using the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule-IV[15] and ICD-10.[12] Then, the following outcome measures were assessed at baseline (0 weeks), and immediate posttreatment (16–20 weeks for SSRI only), and at follow-ups 2 months after posttreatment.

The Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS),[16] consisting of 24 items, was used to assess the fear or anxiety and avoidance of various social interaction and performance situations. The reported reliabilities of the LSAS scales for fear and social interaction were 0.94 and 0.92, respectively.

Social Interaction Anxiety Scale (SIAS),[17] a self-report scale having high levels of internal consistency and discriminant validity, was also used to assess the level of anxiety related to social interaction.

Brief Fear of Negative Evaluation scale (BFNE),[18] a 12-item scale, was used to measure the extent of worries related to unfavorable views by others. Participants are asked to rate on a scale ranging from 1 (not at all characteristic of me) to 5 (extremely characteristic of me). The scale demonstrates good internal consistency.[19]

Statistical analysis

Descriptive data were analyzed by percentage, mean, and standard deviation (SD). Chi-square test was used for analyzing categorical variables. Independent t-test was used to identify any differences between mean values of primary outcome measures of treatment groups at posttreatment and follow-up periods. Paired t-tests were used to identify significance within treatment changes in both the groups. Statistical significance was set at a standard P < 0.05 level. Cohen's d formula was used to calculate effect sizes for both treatment groups at the post, end of the booster, and follow-ups stages. All the data analyses were done using Microsoft Excel software and the SPSS for Windows, version 20. 0 (SPSS, IBM, Chicago, USA).

RESULTS

Participants

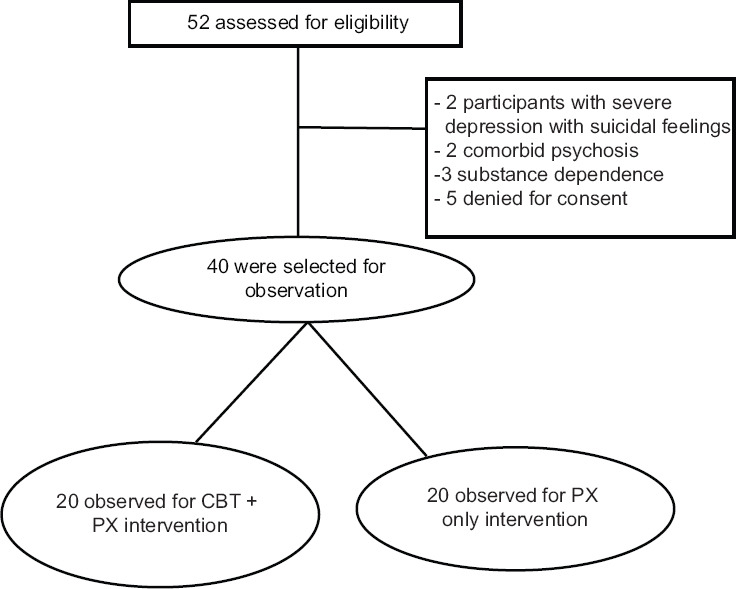

Figure 1 shows the recruitment flowchart of participants during the study period. A total of 52 participants were screened initially for the study. Two participants had severe depression with suicidal feelings, two with comorbid psychosis, three with comorbid substance dependence, and five who denied for the consent were excluded from the study. The final sample size was 40 for the study.

Figure 1.

Recruitment flowchart

Characteristics of patients

Patients' mean age was 31 years (SD = 8.2). The sample was predominantly male (69.0%), married (54.0%), with graduate education (86.0%), and dwelled in urban areas (78.0%). No significant differences in any of these characteristics were found between the treatment groups.

Analysis of group differences over the study period

There were no significant differences in all the measures between the two treatment groups at the baseline stage. Table 1 depicts the differences between the two groups over the study period.

Table 1.

Comparison of cognitive behavior therapy+paroxetine group with paroxetine-only group across the study period

| Baseline | Postintervention | Follow-up | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBT+PX | PX only | CBT+PX | PX only | CBT+PX | PX only | |

| SIAS | 38.1 (8.7) | 41.7 (5.9) | 32.4 (7.9) | 38.9 (5.0)** | 31.7 (7.3) | 39.2 (2.9)*** |

| LSAS | 69.2 (16.3) | 75.8 (9.9) | 57.5 (14.2) | 70.7 (8.9)** | 58.6 (9.2) | 71.0 (7.3)*** |

| BFNE | 37.0 (6.9) | 38.3 (5.9) | 30.9 (9.1) | 35.6 (4.3)* | 32.2 (5.5) | 35.4 (4.5)# |

Figures in parenthesis are SD; *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001; #0.053. SD – Standard deviation; SIAS – Social Interaction Anxiety Scale; LSAS – Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale; BFNE – Brief Fear of Negative Evaluation scale; CBT – Cognitive behavior therapy; PX – Paroxetine

Analysis of the changes within each of the groups

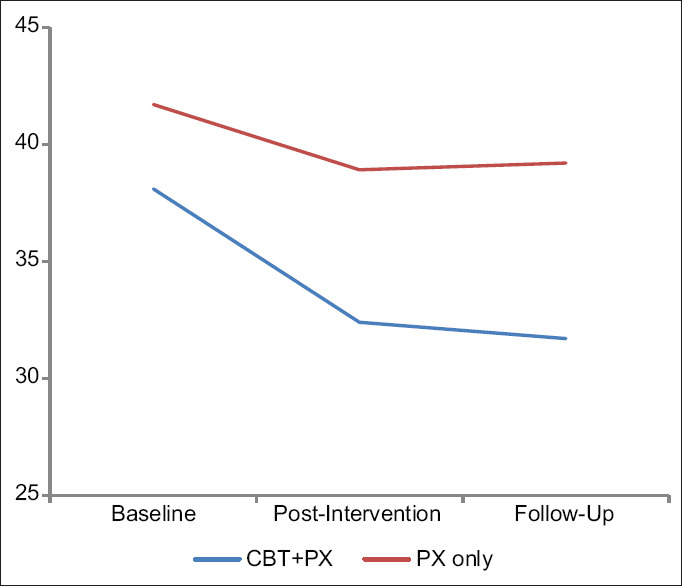

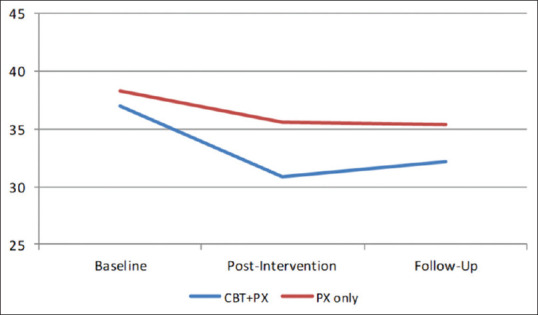

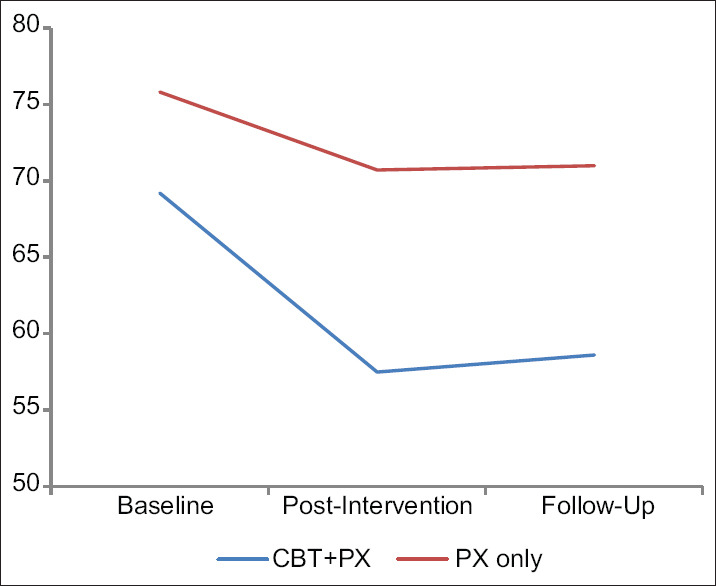

To study within the group changes over the study period, we conducted pair-wise calculations to analyze the changes within the groups CBT + PX group with PX only separately [Figures 2–4].

Figure 2.

Changes in the social interaction anxiety scale score in three periods in CBT+paroxetine group with paroxetine-only group

Figure 4.

Changes in the BFNE score in three periods in CBT+ paroxetine group with paroxetine-only group

Figure 3.

Changes in the Liebowitz social anxiety scale score in three periods in CBT + paroxetine group with paroxetine-only group

In the experimental CBT + PX group, a statistically significant difference (P < 0.001) was observed between baseline compared with post-CBT and followup on all the measures studied. The comparison was not significant for LSAS and BFNE scores between post-CBT and follow-up assessments; however, it was significant for the SIAS.

In the control group, a statistically significant difference was observed between baseline compared with postintervention and follow-up on all measures. However, the postintervention and follow-up measurements of all three measures were not significant.

Maintenance of treatment gains

Following the intervention, on SIAS, there was a statistically significant difference in the CBT + PX group in the follow-up. No other measures were significantly different in either group.

Treatment effectiveness

Cohen's d formula was used to determine the magnitude of the improvement in both the treatment conditions which is determined by calculating the mean difference between the two treatment groups and then by dividing the result by the pooled SD. Cohen's d = (M2 − M1)/SDpooled where SDpooled= √(SD12 + SD22)/2. We used Cohen's threefold classification of effect sizes: small (0.20–0.49), medium (0.50–0.79), and large (0.80 and above). Data are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Effect sizes for outcome measures at posttreatment and follow-up

| CBT+PX | PX only | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Posttreatment | Follow-up | Posttreatment | Follow-up | |

| SIAS | 0.68 | 0.79 | 0.51 | 0.53 |

| LSAS | 0.76 | 0.8 | 0.54 | 0.55 |

| BFNE | 0.75 | 0.76 | 0.52 | 0.55 |

| COM | 0.73 | 0.78 | 0.52 | 0.54 |

COM – Combined effect size; CBT – Cognitive behavior therapy; PX – Paroxetine; SIAS – Social Interaction Anxiety Scale; LSAS – Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale; BFNE – Fear of Negative Evaluation-Brief Version

DISCUSSION

The results of this comparative study showed that both CBT + PX combined and PX alone are effective treatments of SAD as there was a significant improvement in symptoms at immediate posttreatment and follow-up stages in both the groups. However, CBT + SSRI has a better treatment and maintenance gain as compared to SSRI alone in posttreatment and follow-up stages. The effect sizes of combined intervention (CBT + PX) in various measures were better than PX alone.

There are possible reasons to support our main finding that combined treatment of CBT and pharmacotherapy is superior to the general practice of SSRI alone. It has been suggested that the possible mechanisms behind the additive or synergistic effect of these treatment modalities could either be their different mechanisms of action or by mutually facilitating the other's effect.[20] Comparison of our findings with that of Blanco et al.'s study[20] should be made with caution as they used different classes of substance such as phenelzine, a MAOI, and different form of CBT (group format). Similar results too were seen in a study by Blomhoff et al.[4] where combined treatment of sertraline, an SSRI, and CBT was suggested to produce greater benefits which may be a result of additive treatment effects, as also suggested in treatment studies in anxiety disorders performed in other health care settings.[21,22] The present study supported the findings that combined treatment of psychotherapy and an antidepressant medication appears to be more effective than treatment with antidepressant alone and such findings may indicate that the effects of CBT and antidepressant may be independent of each other and additive rather not interfering with each other.[21]

In contrast to the present findings, an interesting observation is seen in the study of Davidson et al.[10] where both fluoxetine alone and CBT alone were better than the combination of these treatments. These studies differed from ours in lack of randomized design, sample characteristics, lack of a CBT-alone group, and longer follow-up phase which may account for some of the different findings.

The present study has also supported the consistent finding that, after treatment completion, gains achieved with treatment involving CBT during are better maintained than with pharmacotherapy alone.[23] In the present study, the combined treatment of CBT and PX has better maintenance of treatment gains than SSRI-alone group in follow-up stages. However, the present study has taken a very short period of follow-up as compared to other studies that have taken 6–12 months.

Limitations and future directions

Interpretations of the present study must be done considering the following limitations. One of the obvious limitations is the limited strength of generalization of an observational study compared with randomized controlled trials. In future studies, a complete factorial design involving CBT only, SSRI only, or a combination of both and placebo would be more beneficial for studying the role of CBT's maintenance of treatment gains. The study has the limitations of a comparatively shorter period of follow-up than other studies that have taken 6–12 months. In addition to PX, the role of other SSRIs may be studied in future.

CONCLUSIONS

PX alone and combined treatment of CBT + PX are effective for SAD, but the combination of CBT + PX is superior to PX alone. Cognitive conceptualization delivered with the use of metaphor is an effective strategy for so. The treatment gains are better maintained during follow-up in the CBT + PX group than PX alone. Hence, a combined treatment may be considered as optimal care for SAD and should be preferred over the monotherapy of PX.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The authors are thankful for the support received from the Quality of Life Research and Development Foundation and the Institute of Insight, UK.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bandelow B, Michaelis S. Epidemiology of anxiety disorders in the 21st century. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2015;17:327–35. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2015.17.3/bbandelow. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aderka IM, Hofmann SG, Nickerson A, Hermesh H, Gilboa-Schechtman E, Marom S. Functional impairment in social anxiety disorder. J Anxiety Disord. 2012;26:393–400. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2012.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mayo-Wilson E, Dias S, Mavranezouli I, Kew K, Clark DM, Ades AE, et al. Psychological and pharmacological interventions for social anxiety disorder in adults: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1:368–76. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70329-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blomhoff S, Haug TT, Hellstrom K, Holme I, Humble M, Madsbutt P, et al. Randomized controlled general practice trial of sertraline, exposure therapy and combined treatment in generalized social phobia. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;179:23–30. doi: 10.1192/bjp.179.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blanco C, Bragdon LB, Schneier FR, Liebowitz MR. The evidence-based pharmacotherapy of social anxiety disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;16:235–49. doi: 10.1017/S1461145712000119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prasko J, Dockery C, Horacek J, Houbova P, Kosova J, Klaschka J, et al. Moclobemide and cognitive behavioral therapy in the treatment of social phobia. A six-month controlled study and 24 months follow up. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2006;27:473–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tripathi AC, Upadhyay S, Paliwal S, Saraf SK. Privileged scaffolds as MAO inhibitors: Retrospect and prospects. Eur J Med Chem. 2018;145:445–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tripathi A, Avasthi A, Desousa A, Bhagabati D, Shah N, Kallivayalil RA, et al. Prescription pattern of antidepressants in five tertiary care psychiatric centres of India. Indian J Med Res. 2016;143:507–13. doi: 10.4103/0971-5916.184289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heimberg RG, Salzman DG, Holt CS, Blendell KA. Cognitive – Behavioral group treatment for social phobia: Effectiveness at five-year follow up. Cognit Ther Res. 1993;17:325–39. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davidson JR, Foa EB, Huppert JD, Keefe FJ, Franklin ME, Compton JS, et al. Fluoxetine, comprehensive cognitive behavioral therapy, and placeboin generalized social phobia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:1005–13. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.10.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Otto MW, McHugh RK, Kantak KM. Combined pharmacotherapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders: Medication effects, glucocorticoids, and attenuated treatment outcomes. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2010;17:91–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2010.01198.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Diagnostic Criteria for Research. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rapee RM, Heimberg RG. A cognitive-behavioral model of anxiety in social phobia. Behav Res Ther. 1997;35:741–56. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(97)00022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Samantaray NN, Kar N, Singh P. Four-session cognitive behavioral therapy for the management of obsessive-compulsive disorder using a metaphor for conceptualization: A case report. Indian J Psychiatry. 2019;61:424–6. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_92_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Di Nardo PA, Brown TA, Barlow DH. Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule: Lifetime Version (ADIS-IV-L) Client Interview Schedules. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fresco DM, Coles ME, Heimberg RG, Liebowitz MR, Hami S, Stein MB, et al. The liebowitz social anxiety scale: A comparison of the psychometric properties of self-report and clinician-administered formats. Psychol Med. 2001;31:1025–35. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701004056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mattick RP, Clarke JC. Development and validation of measures of social phobia scrutiny fear and social interaction anxiety. Behav Res Ther. 1998;36:455–70. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(97)10031-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Collins KA, Westra HA, Dozois DJ, Stewart SH. The validity of the brief version of the fear of negative evaluation scale. J Anxiety Disord. 2005;19:345–59. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duke D, Krishnan M, Faith M, Storch EA. The psychometric properties of the brief fear of negative evaluation scale. J Anxiety Disord. 2006;20:807–17. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blanco C, Heimberg RG, Schneier FR, Fresco DM, Chen H, Turk CL, et al. A placebo-controlled trial of phenelzine, cognitive behavioral group therapy, and their combination for social anxiety disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:286–95. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cuijpers P, Sijbrandij M, Koole SL, Andersson G, Beekman AT, Reynolds CF., 3rd Adding psychotherapy to antidepressant medication in depression and anxiety disorders: A meta-analysis. World Psychiatry. 2014;13:56–67. doi: 10.1002/wps.20089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Samantaray NN, Chaudhury S, Singh P. Efficacy of inhibitory learning theory-based exposure and response prevention and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor in obsessive-compulsive disorder management: A treatment comparison. Ind Psychiatry J. 2018;27:53. doi: 10.4103/ipj.ipj_35_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katzman MA, Bleau P, Blier P, Chokka P, Kjernisted K, Van Ameringen M. Canadian clinical practice guidelines for the management of anxiety, posttraumatic stress and obsessive-compulsive disorders. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:S1. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-14-S1-S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]