Abstract

Suicide is a significant health disparity among Alaska Native youth, which is linked to cultural disruptions brought about by colonialism and historical trauma. Many Indigenous suicide prevention efforts center on revitalizing and connecting youth to their culture to promote mental health and resilience. A common cultural approach to improve psychosocial outcomes is youth culture camps, but there has been little evaluation research to test this association. Here, we conduct a pilot evaluation of a 5-day culture camp developed in two remote regions of Alaska. The camps bring together Alaska Native youth from villages in these regions to take part in subsistence activities, develop new relationships, develop life skills, and learn traditional knowledge and values. This pilot evaluation of the culture camps uses a quantitative pre/post design to examine the outcomes of self-esteem, emotional states, belongingness, mattering to others, and coping skills among participants. Results indicate that culture camps can significantly increase positive mood, feelings of belongingness, and perceived coping of participants. Culture camps are a common suicide prevention effort in Indigenous circumpolar communities, and although limited in scope and design, this pilot evaluation offers some evidence to support culture camps as a health promotion intervention that can reduce suicide risk.

Keywords: culture camps, rural, Alaska Native youth, Indigenous youth, suicide prevention, wellness, culture, protective factors, psychosocial outcomes

THE BURDEN OF SUICIDE IN NORTHWESTERN ALASKA

In 2016, the age-adjusted rate of suicide in Alaska was twice the national rate, with 25.3 suicides per 100,000 population (National Institute of Mental Health, 2017). Rates of suicide in Alaska are highest among young American Indian and Alaska Native males living in rural areas (Alaska Department of Health and Human Services, 2016). Predominantly Alaska Native, the Bering Strait and the Northwest Arctic regions of Alaska have higher rates of suicide compared to the United States (see Table 1). The age-adjusted suicide rate in the Bering Strait region has risen from 66.2 to 78.0 per 100,000 population over the past two decades. This rate is over 3 times that of the state (Alaska Department of Health and Human Services, 2016) and over 6 times the national rate (National Institute of Mental Health, 2017). The age-adjusted rate is even higher for youth and young adults aged 10 to 24 years, at 145.1 per 100,000 population (Gibson, 2017). In the Northwest Arctic Borough, the rate of suicide has been similarly high, but decreases have been observed in recent years (Wexler, Barnett, Trout, & Moto, 2018).

TABLE 1.

Age-Adjusted Suicide Rates Per 100,000 Population in the United States and Alaska

| Geographic Area | 1995-1999 | 2000-2004 | 2005-2009 | 2010-2014 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| U.S. totala | — | 10.8 | 11.3 | 12.5 |

| Alaska total | 21.1 | 20.2 | 21.0 | 22.7 |

| Bering Strait region | 66.2 | 66.9 | 63.2 | 78.0 |

| Northwest Arctic region | 70.3 | 68.2 | 70.1 | 46.7 |

U.S. totals derived from age-adjusted rates averaged in 5-year brackets. Rates are not available for 1995-1998 (National Institute of Mental Health, 2017). Alaska, Bering Strait, and Northwest Arctic data received through a special request (Gibson, 2017).

BACKGROUND

Regional Geographic and Demographic Profile of Northwestern Alaska

Nome is the transportation and service hub to the 15 small villages surrounding it, which together comprise the Bering Strait region (also known as Nome Census Area) with a total population of 9,921 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2017). The Northwest Arctic’s total population is 7,684, and its hub city is Kotzebue, servicing the 11 small nearby villages ranging in size from 100 to 800 people. Currently, over three quarters of the population in both regions are Alaska Native (U.S. Census Bureau, 2017). Cultural groups in Bering Strait include Iñupiaq, Central Yup’ik, and Saint Lawrence Island Yupik, while the Northwest Arctic population is primarily Iñupiaq.

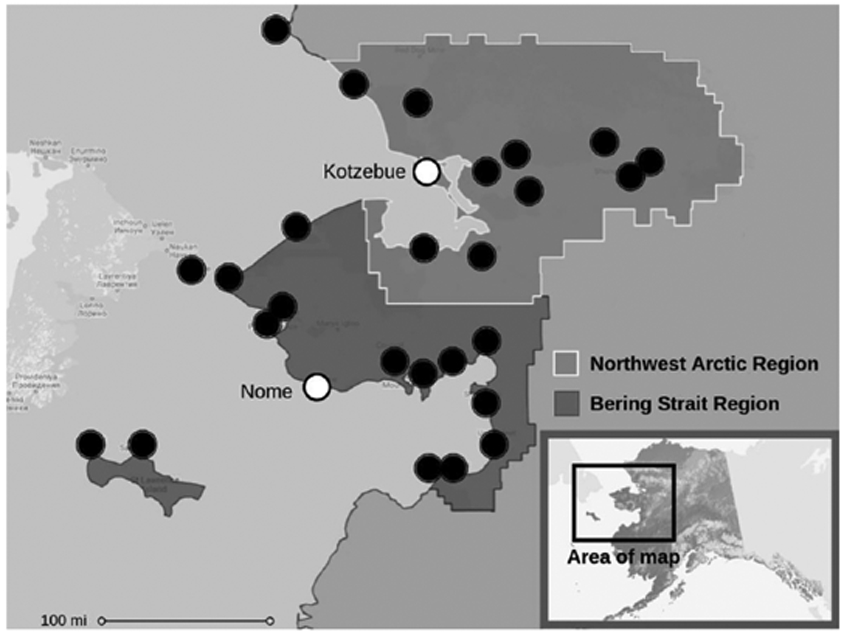

The two adjacent regions cover a 70,000 square mile area above and below the Arctic Circle, which is larger than the state of Oklahoma (see Figure 1). Although the 26 villages are unique, geographic isolation and extreme weather create similar barriers. Life off the connecting road system is challenging and expensive. Village residents must fly in a small commuter plane to Nome and Kotzebue in order to reach regional hospitals and other areas of the state.

FIGURE 1. Map of the Bering Strait and Northwest Arctic Regions of Alaska.

NOTE: Black circles indicate the location of all villages in each region. White circles indicate the larger hub community in each region.

Access to clinical mental health services is also limited in villages, where services are frequently provided by non-Native itinerant mental health counselors who often lack the cultural understanding and local knowledge to adequately intervene (Wexler & Gone, 2012). Therapeutic services are provided by village-based counselors who are local residents and trained paraprofessionals, supported by itinerant mental health clinicians. Fear of stigma and overlapping social relationships can be barriers to accessing local therapeutic services available in small villages. When serious mental health emergencies such as a suicide attempt occur, and individuals cannot be treated using local resources or remote care technology, patients are flown from the village to Nome, Kotzebue, or Anchorage for mental health assessment and, in severe cases, in-patient treatment. Given the challenges to reliable and culturally congruent mental health services in the villages, there is a significant need for locally driven strategies to prevent suicide and foster wellness.

Community and Cultural Factors Associated With Suicide in Indigenous Communities

Colonialism and historical trauma have been linked to disproportionately high rates of suicide in Indigenous communities (Czyzewski, 2011; Sotero, 2006), which is the complex trauma of groups that share a specific identity or affiliation and theorizes a causal explanation for the trauma responses among oppressed peoples (Evans-Campbell, 2008; Griffiths, Coleman, Lee, & Madden, 2016). This trauma includes the prohibition of cultural expression and forced assimilation, which are harms that have collectively and cumulatively affected communities in Alaska (Mohatt, Thompson, Thai, & Tebes, 2014; Sotero, 2006; Whitbeck, Adams, Hoyt, & Chen, 2004). These collective experiences challenge traditional sources of resilience and can reduce local and Indigenous protective factors and increase suicide risk.

Current mental health inequalities among Indigenous people are associated with historical trauma, such as colonialism, epidemic disease, genocide, and the current social, political, and economic implications of systemic marginalization (Czyzewski, 2011; Griffiths et al., 2016; Sotero, 2006). At the community level, historical trauma, imposed rapid social change, and ongoing structural violence combine to increase the risk of physical illness, internalized racism, alcoholism, loss of traditional values and rites of passage, and impaired family functioning, poor mental health, and suicide (Bjerregaard, 2001; Evans-Campbell, 2008). These factors can cause stress and identity conflicts among Alaska Native youth (Allen, Hopper, et al., 2014; Wexler, 2006, 2009).

Western cultural values impose sociocultural priorities, assumptions, and expectations on Indigenous youth, which can be incongruent with Indigenous history, identity, and tradition (Wexler, 2009). Higher rates of suicide in tribal communities are linked to a lack of cultural continuity, while lower rates have been associated with efforts to preserve and rejuvenate culture (Chandler & Lalonde, 1998). In response, some communities have begun cultural revitalization, decolonization, and healing efforts as a way to prevent suicide. In Alaska, culture experiences are documented sources of resilience to suicide (DeCou, Skewes, & López, 2013), and recent community research projects develop further cultural strategies for suicide prevention (Allen, Mohatt, Beehler, & Rowe, 2014; Wexler et al., 2016).

Reviews of Indigenous health research reflect a consensus regarding the importance of community and culture in supporting positive mental health (Lehti, Niemelä, Hoven, Mandell, & Sourander, 2009). Intervention and prevention strategies that are culturally grounded are also more likely to be acceptable to Indigenous communities (Wexler, White, & Trainor, 2015). Although the association between cultural activities and well-being is well-documented (Lehti et al., 2009; MacDonald, Ford, Willox, & Ross, 2013; Redvers et al., 2015; Sahota & Kastelic, 2012), we currently know little about the efficacy of such activities for strengthening youth wellness. Research is needed to better understand the impact of culturally based interventions on Indigenous youth wellness.

Individual Factors Associated With Suicide in Indigenous Communities

There are documented individual risk and protective factors for suicidality among Alaska Native and American Indian youth (Hensen, Sabo, Trujillo, & Teufel-Shone, 2016). Individual protective factors positively associated with health and social outcomes among Alaska Native and American Indian youth include having current and future aspirations, physical and emotional health, positive self-image, self-efficacy, interpersonal connectedness, positive opportunities, positive social norms, and cultural connectedness (Hensen et al., 2016). The interpersonal theory of suicidal behavior describes a lack of belongingness and perceived burdensomeness as individual-level risk factors for suicide (Van Orden et al., 2010).

Youth Culture Camps to Increase Wellness Among Alaska Native Youth

Community, relationships, and culture are recurring themes in the limited literature on reducing suicide in circumpolar regions to date (MacDonald et al., 2013). Building on Indigenous sources of resilience (Allen, Hopper, et al., 2014) and local cultural revitalization efforts, leaders in northwestern Alaska offer culture camps as one component of locally driven youth suicide prevention efforts since 2010. Each year, 12 to 25 youth from villages in each region travel to a remote site for 5 days to participate in cultural activities, develop relationships with other youth and adult role models, and talk about their struggles. Camps are advertised to the public and specifically to village adults who interact with youth. While some youth apply on their own, most are encouraged to apply by school staff or other adults who feel they would benefit.

Youth are selected by camp leaders based on flexible criteria that seeks to create a cohesive group and give as many teens as possible the opportunity to attend. Youth who have never attended a previous camp and youth experiencing challenges (e.g., foster care, recent violence in the community, or grieving a death by suicide) are given priority. Program staff members ensure a balance of male and female participants and representation from different villages. Camp participants who demonstrate leadership potential and express interest are invited back as staff in future years.

During the 5-day camp, Elders and guest presenters share cultural knowledge and stories, teach traditional skills, and wellness practitioners teach suicide prevention and other life skill topics such as substance abuse prevention, healthy relationships, and bullying prevention. Supervisors range in age from early 20s to Elders. While camps vary somewhat in content and structure from year to year, morning and early afternoon are scheduled for instruction via teaching, traditional storytelling, and team-building exercises. Late afternoon and early evening hours include unstructured time for youth to swim, canoe, play basketball, or pick berries. In the evening, group cultural activities include sauna, or maqii, and beading and skin sewing. Camp Pigaaq often incorporates time for subsistence activities. All camps close with a talking circle.

METHOD

Pilot Evaluation of Youth Culture Camps in Northwestern Alaska

The evaluation used a pre/post survey design among the youth who attended culture camps to examine the psychosocial outcomes of self-esteem, emotional states, belongingness, mattering to others, and perceived coping skills. We believe these outcomes will result from connecting Alaska Native youth to their Indigenous culture through stories, skill building, and strengthening interpersonal relationships between other youth and adult mentors and Elders. All evaluation activities were approved by the University of Alaska Anchorage Institutional Review Board and the Alaska Area institutional Review Board prior to data collection. Parental consent and youth assent were obtained from all participants prior to administering surveys.

Setting and Participants

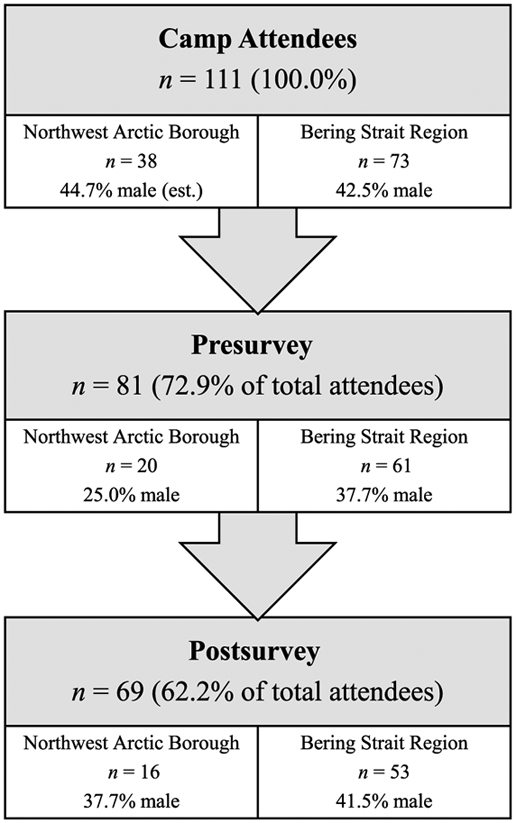

During 2012 and 2013, 111 Alaska Native youth aged 13 to 18 years attended culture camps; 43.25% were male and 56.75% were female. Pre- and post-surveys were distributed by camp staff to youth with parental consent immediately before and at the end of the camp. Eighty-one youth completed the presurvey (72.9%) and 69 youth (62.2%) completed the postsurvey (see Figure 2). To protect confidentiality, participants placed their completed surveys with ID numbers into individual sealed envelopes. Reasons for noncompletion included a lack of signed parental consent form, arriving late due to delayed flights, leaving early from the camp due to injury, or refusal to complete the survey.

FIGURE 2.

Camp Participation and Survey Attrition

Measures

Surveys included demographic questions and five scales and inventories designed to measure psychosocial outcomes associated with suicide risk. Surveys were reviewed and approved by camp leaders for cultural appropriateness and pilot tested with youth.

The Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) is used to assess positive and negative emotional states (Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988). However, the shorter 10-item International Positive and Negative Affect Schedule–Short-Form (I-PANAS-SF) was used due to its adequate reliability and validity and to reduce survey fatigue. Items about feelings experienced over the past week were scored on a 4-point Likert-type scale (α = .65) from 1 (not at all) to 4 (a lot). This is a change from the 1- (never) to 5- (always) point scale used in the validated I-PANAS-SF (Thompson, 2007). A maximum total score of 40 is possible, with higher scores indicating more favorable affect.

The Multicultural Mastery Scale (MMS) for Youth is designed for Alaska Native youth to measure problem-focused coping. The MMS has three foci (family, friends, self) subsumed under a higher, first-order overall mastery factor (Fok, Allen, Henry, Mohatt, & People Awakening Team, 2012). It consists of 13 items (α = .76) scored from 1 (not at all) to 5 (a lot). Higher scores indicate greater coping skills.

The Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire is a 25-item Likert-type scale survey derived from the interpersonal theory of suicide. It measures thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness, which are both considered proximal contributors to suicide. The constructs are related but distinct and can be reliably measured separately (Van Orden, Cukrowicz, Witte, & Joiner, 2012). Only the Belongingness subscale was used due to tribal partners’ preference to focus on wellness rather than risk, with 13 scale items (α = .85) scored from 1 (not at all true) to 7 (very true).

The General Mattering Scale measures the extent to which youth feel they matter to others, which can protect against suicide risk. It has five items, with a 4-point Likert-type scale (α = .78) ranging from 1 (not at all) to 4 (very much). Higher scores reflect stronger beliefs about mattering (DeForge & Barclay, 1997).

The Rosenburg Self-Esteem Scale is a 10-item, 4-point Likert-type scale (α = .72) ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree), and measures perceived self-worth. Higher scores indicate greater self-esteem (Rosenburg, 1965), reducing the risk for suicide.

Analysis

Survey analysis used IBM SPSS Statistics, Version 24. All data were cleaned, checked for outliers, and tested for assumptions of normality. Missing values were replaced with the sample mean for the scale, which was conducted separately in the presurvey and postsurvey data sets. Missing values among individual items ranged from 0% to 9% on the presurvey. Most items (78%) had fewer than 5% of values missing. All survey items on the postsurvey had fewer than 3% of values missing.

Changes in psychosocial measures were measured using a repeated-measures multivariate analysis of variance with dependent measures as scales described above. Effect sizes for all univariate comparisons were measured using partial eta-square and interpreted as 0.01 ≈ small, 0.06 ≈ medium, and 0.14 ≈ large (Cohen, 1988).

RESULTS

To test the assumptions of a multivariate analysis of variance, a Pearson product–moment bivariate correlation coefficient was computed to assess the linear relationship between presurvey measures (see Table 2). Moderate linear correlations (.30 to .70) were found between most survey measures with no multicollinearity present. The I-PANAS-SF was found to be the least correlated with other survey measures, likely due to its short-term and state-based construct.

TABLE 2.

Pearson Product–Moment Correlations Between Survey Measure Scores (r)

| Measure | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. I-PANAS-SF | — | .12 | .27* | .02 | .37** |

| 2. Multicultural Mastery | — | .68** | .40** | .08 | |

| 3. Interpersonal Needs: Belongingness | — | .55** | .38** | ||

| 4. General Mattering | — | .37* | |||

| 5. Rosenburg Self-Esteem | — |

NOTE. I-PANAS-SF = International Positive and Negative Affect Schedule–Short Form.

p < .05.

p < .001.

A significant within-subjects multivariate effect was found over time, F(5, 62) = 4.00, p < .01; Wilks’s Λ = 0.691, . Univariate tests identified significant improvements in mood scores on the I-PANAS-SF, an increased sense of belonging on the Belongingness subscale of the Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire, and increased ability to cope with life stressors on the Self subscale of the MMS (see Table 3). No significant differences were found on other survey measures over time.

TABLE 3.

Pre to Post Change in Psychosocial Measures

|

Pre |

Post |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scale | M | SD | M | SD | F | |

| I-PANAS-SF | 30.72 | 4.00 | 33.18 | 4.01 | 21.50*** | 0.24 |

| Multicultural Mastery: Friends | 3.57 | 0.74 | 3.63 | 0.75 | 0.43 | 0.01 |

| Multicultural Mastery: Family | 4.03 | 0.81 | 4.10 | 0.79 | 0.88 | 0.01 |

| Multicultural Mastery: Self | 3.64 | 0.77 | 3.83 | 0.77 | 5.40* | 0.07 |

| Interpersonal Needs: Belongingness | 5.10 | 0.96 | 5.40 | 1.13 | 4.53* | 0.06 |

| General Mattering | 2.97 | 0.56 | 3.05 | 0.66 | 1.20 | 0.02 |

| Rosenburg Self-Esteem | 2.91 | 0.39 | 2.98 | 0.42 | 3.14 | 0.04 |

NOTE. I-PANAS-SF = International Positive and Negative Affect Schedule–Short Form.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Gender was added to the analysis as a between-subjects factor and was found to be significant, F(5, 61) = 3.30, p < .01; Wilks’s Λ = 0.725, . Pairwise comparisons by gender revealed that males had significantly higher scores than females overall on the I-PANAS-SF (p< .01), the General Mattering Scale (p < .05), and the Rosenburg Self-Esteem Scale (p < 001). There was no significant interaction of gender over time, F(5, 61) = 0.686, p = .68; Wilks’s Λ = 0.927, , and the multivariate effect of time from pre- to postcamp remained significant, F(5, 61), 3.51, p < .01; Wilks’s Λ = 0.713, .

DISCUSSION

Summary of Main Findings

As culture camps increase in popularity within Alaska Indigenous communities, understanding their role in supporting youth protective factors and wellness is crucial for broader suicide prevention programing. While males reported more favorable scores overall, all participants of the weeklong culture camps in two regions reported more positive mood, an increased sense of belongingness, and greater perceived internal ability to handle potential life stressors. Surveys did not document significant changes pre- to postcamp in participants’ perception of mattering to others, self-esteem, or perceived support for coping with life stressors from friends or family.

Interpretation of Results

This evaluation is an important first step in the research literature to explore the upstream effectiveness of Indigenous youth culture camps on wellness. While a weeklong camp is not enough to undo the impact of colonialism, historical and current trauma, and suicide disparities on Alaska Native youth, the results show positive psychosocial outcomes related to wellness and suicide risk. Youth reported feeling better at the end of camp than when they arrived and reported increased ability to cope with potential life stressors. Coping self-efficacy is predictive of psychosocial well-being in marginalized youth and is associated with a lower risk for symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress (Melato, van Eeden, Rothmann, & Bothma, 2017). The culture camps also provide an opportunity for the development of positive relationships between youth and their peers and with caring adults due to the frequency of structured and unstructured interactions in a cooperative living environment. Studies have highlighted caring connections as an important mechanism for youth wellness (Anderson-Butcher, Cash, Saltzburg, Midle, & Pace, 2004; Wyman, 2014), which may increase feelings of belongingness among youth from pre- to postcamp. This greater sense of belonging has the ability to offer protection against suicide according to the interpersonal theory of suicide (Joiner et al., 2009).

While moving in the expected direction, the lack of statistically significant change in the Family and Friend subscales of the MMS, General Mattering Scale, and Rosenburg Self-Esteem Scale may be due to several contributing factors. Possibly, there was no true change on these measures. It is also possible that these measures did not adequately capture the full impact of the experience due to the pre–post design. Last, the weeklong duration of the intervention may not be enough to measurably change these dimensions. Future evaluations could measure other aspects of Indigenous youth wellness such as cultural connectedness (Snowshoe, Crooks, Tremblay, Craig, & Hinson, 2015) and include measures to assess change in knowledge and attitudes related to educational content, document the impact of different camp lengths, and use a longitudinal design. In-depth qualitative interviews with youth camp participants could also provide valuable insight about how youth perceive the experience, what resonated with them as Alaska Native youth, and how they incorporated the experience into their lives.

Limitations

The study assessed pre–post change in psychosocial outcomes over 1 week, which limits our understanding about the durability of improvements over time. However, we feel this evaluation has taken a first step in building incremental knowledge about the benefits of these camps for Indigenous youth. An incentivized online follow-up survey and brief interviews were administered 3 to 5 months after camp; however, a low response rate precluded these data from the analysis. The low response rate was due to geographic challenges with participants residing in 24 remote communities, phone numbers changing, and lack of e-mail use. Additional measures of substance use and feelings of hopelessness and depression over the past 3 months could not be included in the current analysis since they are applicable only if compared between pre and follow-up. Finding novel ways to successfully contact and conduct follow-up surveys with youth is important for future work in rural Alaska.

Other survey measures such as the Modified Self-Concept Clarity Scale were cut from the analysis due to extensive changes by camp staff for cultural appropriateness, both in question wording and questions omitted, which ultimately compromised measure validity. Finding culturally appropriate yet valid measures for this population is needed for future evaluation efforts.

Other study limitations include a lack of funding and programmatic design challenges to allow for an adequate control group to compare and account for other possible influences. The psychosocial measures used are intermediate, rather than direct, measures of suicide risk or protection. Feelings of hopelessness or depression are good proxy measures of suicide risk but were excluded from the analysis for reasons described above.

Broader Implications

Culture camps are an important part of cultural revitalization efforts in Alaska, and tribal communities frequently implement them as a component of suicide prevention programming. This pilot evaluation is a first attempt to measure psychosocial outcomes of youth who participated in a weeklong culture camp. These findings suggest that culture camps are a positive emotional experience with youth participants gaining confidence to handle life stressors and reflecting increased feelings of belongingness, an important condition of interpersonal suicide prevention (Joiner et al., 2009). More research is needed to identify other potential risk and protective factors culture camps may influence and to describe the most salient elements of the experience. These results suggest that developing connections with peers, learning life skills, enhancing positive cultural identity self-reflections, and developing meaningful relationships with Alaska Native adults are important elements of culture camps that helped to improve the psychosocial outcomes among Alaska Native youth that were measured in this evaluation.

CONCLUSIONS

Culture camps are a positive experience for Alaska Native youth and have the ability to improve psychosocial outcomes based on our evaluation findings. Alone, it is unlikely that these camps can repair decades of cultural disruption within Northwestern Alaska implicated in the health inequity of Alaska Native youth suicide. However, results indicate that culture camps have an important place in locally driven and multilevel suicide prevention efforts that, collectively, have the ability to reduce suicide rates within Indigenous communities over many years (Wexler et al., 2018).

Acknowledgments

This research project was funded by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Garrett Lee Smith Grant (Award No. SM11001) to Kawerak, Inc.

REFERENCES

- Alaska Department of Health and Human Services. (2016). Health indicator report of suicide mortality rate, 5-year average, 2011-2015. Retrieved from http://ibis.dhss.alaska.gov/indicator/view/Suic1524.SEX.html [Google Scholar]

- Allen J, Hopper K, Wexler L, Kral M, Rasmus S, & Nystad K (2014). Mapping resilience pathways of Indigenous youth in five circumpolar communities. Transcultural Psychiatry, 51, 601–631. doi: 10.1177/1363461513497232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen J, Mohatt GV, Beehler S, & Rowe HL (2014). People awakening: Collaborative research to develop cultural strategies for prevention in community intervention. American Journal of Community Psychology, 54, 100–111. doi: 10.1007/s10464-014-9647-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson-Butcher D, Cash S, Saltzburg S, Midle T, & Pace D (2004). Institutions of youth development: The significance of supportive staff-youth relationships. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 9(1-2), 83–99. doi: 10.4324/9781315044118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bjerregaard P (2001). Rapid socio-cultural change and health in the Arctic. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 60, 102–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler MJ, & Lalonde CE (1998). Cultural continuity as a hedge against suicide in Canada’s First Nations. Transcultural Psychiatry, 35, 191–219. doi: 10.1177/136346159803500202 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Czyzewski K (2011). Colonialism as a broader social determinant of health. International Indigenous Policy Journal, 2(1). doi: 10.18584/iipj.2011.2.1.5. Retrieved from http://ir.lib.uwo.ca/iipj/vol2/iss1/5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DeCou CR, Skewes MC, & López EDS (2013). Traditional living and cultural ways as protective factors against suicide: Perceptions of Alaska Native university students. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 72. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v72i0.20968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeForge BR, & Barclay DM III. (1997). The internal reliability of a general mattering scale in homeless men. Psychological Reports, 80, 429–430. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1997.80.2.429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Campbell T (2008). Historical trauma in American Indian/Native Alaska communities: A multilevel framework for exploring impacts on individuals, families, and communities. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 23, 316–338. doi: 10.1177/0886260507312290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fok CCT, Allen J, Henry D, Mohatt GV, & People Awakening Team. (2012). Multicultural Mastery Scale for youth: Multidimensional assessment of culturally mediated coping strategies. Psychological Assessment, 24, 313–327. doi: 10.1037/a0025505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson DA (2017). Suicide death rates from 1995-2014: Alaska, Northwest Arctic Borough, and the Bering Strait Region [Special data request]. Alaska Department of Health and Social Services, Alaska Division of Public Health, Section of Health Analytics and Vital Records. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths K, Coleman C, Lee V, & Madden R (2016). How colonisation determines social justice and Indigenous health: A review of the literature. Journal of Population Research, 33(1), 9–30. doi: 10.1007/s12546-016-9164-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hensen M, Sabo S, Trujillo A, & Teufel-Shone M (2016). Identifying protective factors to promote health in American Indian and Alaska Native adolescents: A literature review. Journal of Primary Prevention, 38(5), 5–26. doi: 10.1007/s10935-016-0455-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE Jr., Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Selby EA, Ribeiro JD, Lewis R, & Rudd MD (2009). Main predictions of the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior: Empirical tests in two samples of young adults. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 118, 634–646. doi: 10.1037/a0016500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehti V, Niemelä S, Hoven C, Mandell D, & Sourander A (2009). Mental health, substance use and suicidal behaviour among young indigenous people in the Arctic: A systematic review. Social Science & Medicine, 69, 1194–1203. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.07.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald JP, Ford JD, Willox AC, & Ross NA (2013). A review of protective factors and causal mechanisms that enhance the mental health of indigenous circumpolar youth. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 72, 21775. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v72i0.21775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melato SR, van Eeden C, Rothmann S, & Bothma E (2017). Coping self-efficacy and psychosocial well-being of marginalised South African youth. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 27, 338–344. doi: 10.1080/14330237.2017.1347755 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mohatt NV, Thompson AB, Thai ND, & Tebes JK (2014). Historical trauma as public narrative: A conceptual review of how history impacts present-day health. Social Science & Medicine, 106, 128–136. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.01.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Mental Health. (2017). Age-adjusted suicide rates in the United States (1999-2014). Retrieved from www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/suicide/index.shtml#part_153200

- Redvers J, Bjerregaard P, Eriksen H, Fanian S, Healey G, Hiratsuka V, … Chatwood S (2015). A scoping review of Indigenous suicide prevention in circumpolar regions. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 74(1). doi: 10.3402/ijch.v74.27509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenburg M (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sahota PC, & Kastelic S (2012). Culturally appropriate evaluation of tribally based suicide prevention programs: A review of current approaches. Wicazo Sa Review, 27(2), 99–127. doi: 10.5749/wicazosareview.27.2.0099 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Snowshoe A, Crooks CV, Tremblay PF, Craig WM, & Hinson RE (2015). Development of a cultural connectedness scale for First Nations youth. Psychological Assessment, 27, 249–259. doi: 10.1037/a0037867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotero MM (2006). A conceptual model of historical trauma: Implication for public health practice research. Journal of Health Disparities Research and Practice, 1, 93–108. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson ER (2007). Development and validation of an internationally reliable short-form of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS). Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 38, 227–242. doi: 10.1177/0022022106297301 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2017). Quick facts. Retrieved from www.census.gov/quickfacts/

- Van Orden KA, Cukrowicz KC, Witte TK, & Joiner TE Jr. (2012). Thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness: Construct validity and psychometric properties of the Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire. Psychological Assessment, 24, 197–215. doi: 10.1037/a0025358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Cukrowicz KC, Braithwaite SR, Selby EA, & Joiner TE Jr. (2010). The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychological Review, 117, 575–600. doi: 10.1037/a0018697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, & Tellegen A (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS Scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 1063–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wexler L (2006). Inupiat youth suicide and culture loss: Changing community conversations for prevention. Social Science & Medicine, 63, 2938–2948. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.07.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wexler L (2009). Identifying colonial discourses in Inupiat young people’s narratives as a way to understand the no future of Inupiat youth suicide. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research, 16, 1–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wexler L, Barnett J, Trout L, & Moto R (2018). Making a difference: How Northwest Alaska is working to reduce youth suicide. Northern Public Affairs, 5(3), 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Wexler L, & Gone J (2012). Examining cultural incongruities in western and Indigenous suicide prevention to develop responsive programming. American Journal of Public Health, 105, 800–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wexler L, McEachern D, DiFulvio GT, Smith C, Graham LF, & Dombrowski K (2016). Creating a community of practice to prevent suicide through multiple channels: Describing the theoretical foundations and structured learning of PC CARES. International Quarterly of Community Health Education, 36, 115–122. doi: 10.1177/0272684x16630886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wexler L, White J, & Trainor B (2015). Why an alternative to suicide prevention gatekeeper training is needed for rural Indigenous communities: Presenting an empowering community storytelling approach. Critical Public Health, 25, 205–217. doi: 10.1080/09581596.2014.904039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitbeck LB, Adams GW, Hoyt DR, & Chen X (2004). Conceptualizing and measuring historical trauma among American Indian people. American Journal of Community Psychology, 33, 119–130. doi: 10.1023/B:AJCP.0000027000.77357.31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyman PA (2014). Developmental approach to prevent adolescent suicides: Research pathways to effective upstream preventive Interventions. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 47(3 Suppl. 2), S251–S256. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.05.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]