Abstract

Here, we report on a rare case of gastric hyperplastic polyps which disappeared after the discontinuation of proton pump inhibitor (PPI). The patient was an 83-year-old woman with liver cirrhosis and portal hypertension, along with gastroesophageal reflux disease treated by PPI. An initial upper gastrointestinal endoscopy showed unique polypoid lesions in the greater curvature of the stomach. Biopsy specimens of the lesions were diagnosed as hyperplastic polyps and she was followed. One year later, a second endoscopy showed that the lesions had increased in number and size, and an endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) was performed for the main polyps. The resected specimens indicated a proliferation of foveolar epithelium cells with an increase of capillary ectasia and parietal cell hyperplasia, which was thought to be induced by hypergastrinemia from the PPI. Three months after the EMR, she was admitted because of bleeding from the remaining polyps along with an increase in new polyps. After conservative treatment, PPI was stopped and rebamipide was used. One year and 6 months later, an endoscopy showed the complete disappearance of all gastric polyps.

Keywords: Gastric hyperplastic polyp, Proton pump inhibitor, Hypergastrinemia

Introduction

The pathogenesis of gastric hyperplastic polyps is still unknown, but it is suggested that the exaggerated repair of mucosal damage, antral hypercontraction, and hypergastrinemia may play a role in the development of polyps. In general, gastric hyperplastic polyps develop from the atrophic gastric mucosa with inflammation induced by Helicobacter pylori (HP) infection [1] or autoimmune gastritis [2]. Moreover, several recent studies have reported that the long-term use of proton pump inhibitor (PPI) may cause not only fundic gland polyps [3, 4] but also hyperplastic polyps through hypergastrinemia [5]. The clinical significance of gastric hyperplastic polyps is whether they have malignant potential and cause anemia or not [6].

Although large or hemorrhagic gastric hyperplastic polyps can be removed endoscopically, endoscopic therapy is not a fundamental treatment for gastric hyperplastic polyps because the cause of the polyps has not been eliminated. Outside of endoscopic therapy, several recent studies have demonstrated that a regression or disappearance of gastric hyperplastic polyps is found after HP eradication therapy and/or the discontinuation of PPI [7, 8, 9].

Here, we report on a rare case of gastric hyperplastic polyps and show the unique endoscopic and pathological findings in which the gastric polyps disappeared naturally after the discontinuation of PPI in a patient with liver cirrhosis and portal hypertension.

Case Presentation

An 83-year-old woman had been treated for liver cirrhosis due to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), with essential hypertension and gastro-esophageal reflux (GERD) at our hospital and at another outside hospital. In March 2014, an initial upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (UGE) showed multiple reddish polypoid lesions in the greater curvature of the stomach. The endoscopic finding of main polyps was unique, and a part of the mucosal folds of the greater curvature was swollen like a sausage, with a reddish surface. A red ridge on the fold beside the main lesion was also recognized. Two consecutive raised lesions on the fold beside the main lesion were also recognized. In addition, a broad-based reddish polypoid lesion was observed on the anterior wall side next to the two lesions, with a clot adhering to part of it. In addition, two small fundic gland polyps were noted (Fig. 1a).

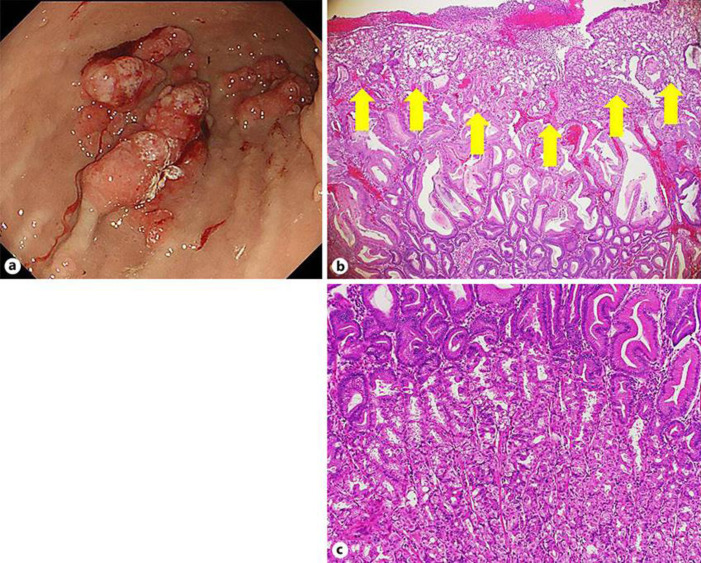

Fig. 1.

A part of the mucosal folds of the greater curvature of the stomach was swollen like a sausage, with a red surface (arrows). A red ridge on the fold beside the main lesion was also recognized. Two consecutive raised lesions on the fold beside the main lesion were also recognized. In addition, a broad-based reddish polypoid lesion was observed on the anterior wall side next to the two lesions, with a clot adhering to part of it. In addition, two small fundic gland polyps were noted (a). Biopsy specimens of gastric polyps show hyperplasia of the foveolar epithelium cells with edema of lamina propria and an increase of capillaries (H&E stain, ×100) (b).

Biopsy specimens of the lesion indicated hyperplasia of the foveolar epithelium and was diagnosed as gastric hyperplastic polyps (Fig. 1b). We suspected that those hyperplastic polyps were associated with PPI because no atrophic change was found in the stomach as a whole, all HP tests (Ig G antibody, rapid urease test, and urea breath test) were negative, and she had a long-term history of PPI use (rabeprazole 10 mg/day). Her fasting serum gastrin level was 776 pg/dL (normal range: 50–150 pg/dL).

One year later, she was diagnosed with pneumonia and admitted to our hospital. At that time, she had an additional diagnosis of autoimmune hemolytic anemia (Hb, 8.0 g/dL). More than 2 years after that, she was admitted to our hospital with appetite loss, dizziness, and severe anemia (Hb, 5.0 g/dL). A UGE indicated multiple gastric polyps with a granular surface and natural bleeding in the curvature, the number and size of the polyps had increased compared to previous exams. In addition, new adjacent polypoid lesions were found in the greater curvature of the antrum (Fig. 2a).

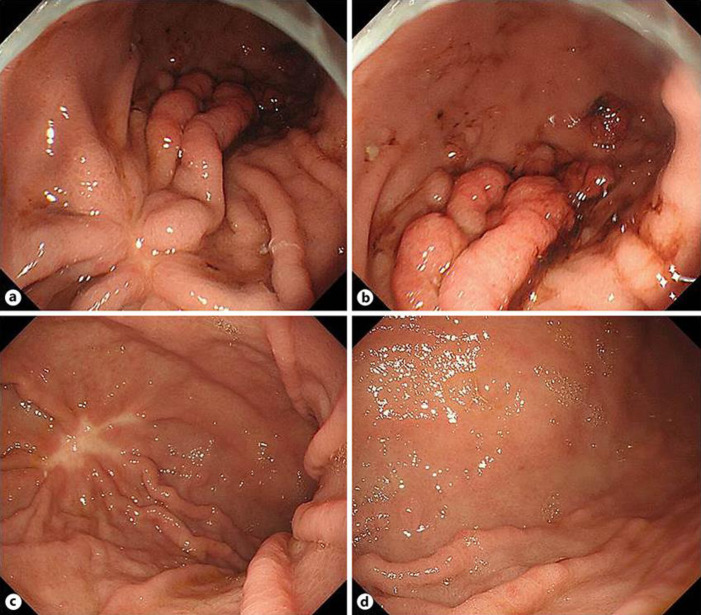

Fig. 2.

Compared with the previous findings, the morphology of the polypoid lesions has obviously changed. The swelling has increased, the number of lesions has also increased, and there are white mossy surface nodules with clots attached. Additionally, ridged lesions were found on the pylorus side in line with the mucosal folds (a). Pathological findings of the resected polyps showed the crypt hyperplasia with an edematous lamina propria containing prominent ectasia in the vessels of the surface epithelium (arrows) (H&E stain, ×200) (b). The deep layer of the resected polyps shows cystic dilation of the fundic glands and a remarkable hyperplasia of the parietal cells (H&E stain, ×400) (c).

An EMR was performed on the main gastric polyps and she was followed. Pathological findings of the resected polyps showed the crypt hyperplasia with an edematous lamina propria containing prominent ectasia in the vessels of the surface epithelium (Fig. 2b). In addition, there was cystic dilation of the fundic glands and a remarkable hyperplasia of the parietal cells deep in the hyperplastic polyps (Fig. 2c).

Three months after the EMR, she was admitted with hematemesis, and an emergency endoscopy revealed bleeding from the remaining gastric polyps and also from renewed polyps (Fig. 3a, b). After conservative treatment, the PPI rabeprazole (10 mg/day) was stopped and the mucoprotective agent rebamipide (300 mg/day) was started. She was followed at another outside hospital and her anemia was stable (Hb, 7.0∼9.0 g/dL) for the next 1 year and 6 months.

Fig. 3.

The area resected by EMR scarred and no ridge formation was observed (a). However, the ridge on the fold side on the pylorus side increased, and there were many raised lesions with blood clots on the pylorus side (b). Endoscopic findings 1 year and 6 months after the discontinuation of PPI and with the use of rebamipide are shown. Although post-EMR scarring with conversing folds is found in the middle of corpus (c), the welling of mucosal folds and surface redness are not found. All previous polypoid lesions in the antrum completely disappeared (d).

She was re-admitted due to uncontrolled ascites and hepatic encephalopathy from cirrhosis. A UGE showed a post-EMR scar in the middle of the corpus and all polyps in the antrum and the lower part of the corpus had completely disappeared (Fig. 3c, d). She was treated for liver failure but died of progression of the disease 28 days after admission.

Discussion/Conclusion

Here, we reported on a rare case of gastric hyperplastic polyps with unique endoscopic and pathological findings which disappeared completely after the discontinuation of PPI. Furthermore, it was possible to stop the refractory anemia which was thought to be caused by the bleeding from the gastric polyps.

The gastric polyps in this case showed unique endoscopic findings of a sausage-like swelling of parts of the mucosal folds and broad-based reddish polyps with a relatively smooth surface. The sub-pedunculated and pedunculated dome-shaped forms were different from other more common gastric hyperplastic polyps.

Gastric hyperplastic polyps in patients with portal hypertension are known as portal hypertensive polyps or portal hypertension associated polyps. Published endoscopic findings of portal hypertensive polyps show them to be reddish, slender, with a tendency for tandem lesions with an earthworm-like swelling on the surface [10]. In general, the most common locations are in the antrum or the greater curvature; however, they are also found in the lower corpus [11]. One specific pathological finding of portal hypertensive polyps is a remarkable increase of capillary vessels in the surface of the polyp [10]. In this case, the polyps were located in the greater curvature and showed a remarkable increase of capillary vessels in the surface of the hyperplastic polyps that corresponded to those of portal hypertensive polyps.

In this case, the gastric polyps developed from non-atrophic mucosa without HP infection and disappeared completely after the discontinuation of PPI and the use of rebamipide. In general, gastric hyperplastic polyps arise from the atrophic gastric mucosa with inflammation induced by HP infection or autoimmune gastritis [1, 2]. Recently, several reports have demonstrated the development of gastric hyperplastic polyps as well as fundic gland polyps in patients with long-term PPI use [5]. The polyps are suspected to be associated to hypergastrinemia induced by the prolonged use of PPI [3, 12, 13]. In our case, HP infection was negative, and the endoscopy found no hypergastrinemia-related gastric mucosa atrophy (776 pg/dL). Our previous studies about the pathogenesis of gastric hyperplastic and other types of polyps demonstrated that hypergastrinemia induced by severe atrophic gastritis of the corpus or the prolonged use of PPI might play a role in the development of gastric hyperplastic polyps [14]. It is well known that gastrin has a trophic effect on gastrointestinal mucosa [12]. The rebamipide was used to decrease the gastrin level in the blood as well as to assist in repairing the gastric mucosal tissue [15].

It is well known that the disappearance or regression of fundic gland polyps is found in patients after the discontinuation of prolonged PPI use [13]. Moreover, two reports from Japan have demonstrated a similar phenomenon in patients with gastric hyperplastic polyps caused by PPI [7, 8]. Okazaki et al. [7]reported that gastric hyperplastic polyps disappeared 1 year after switching from PPI to an H2 receptor antagonist in an HP-negative patient with GERD. While the serum gastrin level was not indicated, Anjiki et al. [8] also reported on an HP-positive case of multiple hyperplastic polyps with adenocarcinoma. In that case, hypergastrinemia induced by PPI was found and after discontinuing PPI, the gastric polyps disappeared with the normalization of gastrin level. HP eradication therapy was also performed after discontinuing PPI. It is well known that HP eradication therapy normalizes serum gastrin levels which allows gastric hyperplastic polyps to disappear. Therefore, it is difficult to conclude whether the eradication of HP or the discontinuation of PPI might be responsible for the disappearance of gastric polyps.

In general practice, PPI is commonly used for long periods of time as therapy for reflux esophagitis, peptic ulcer diseases and their prevention, and HP eradication therapy. If gastric hyperplastic polyps with complications, such as bleeding or anemia are observed, as they were in this case, it is necessary to consider whether hypergastrinemia is being caused by PPI, and to decide to decrease the dose of PPI, switch to an H2 receptor antagonist, or discontinue the PPI altogether.

Statement of Ethics

We have reported this case in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient and her next of kin for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

No authors have declared any specific grant for this article.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Ayumi Iwata for revising this article, including English expressions.

References

- 1.Abraham SC, Singh VK, Yardley JH, Wu TT. Hyperplastic polyps of the stomach: associations with histologic patterns of gastritis and gastric atrophy. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001 Apr;25((4)):500–7. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200104000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yamanaka K, Miyatani H, Yoshida Y, Ishii T, Asabe S, Takada O, et al. Malignant transformation of a gastric hyperplastic polyp in a context of Helicobacter pylori-negative autoimmune gastritis: a case report. BMC Gastroenterol. 2016 Oct;16((1)):130. doi: 10.1186/s12876-016-0537-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hongo M, Fujimoto K, Gastric Polyps Study Group Incidence and risk factor of fundic gland polyp and hyperplastic polyp in long-term proton pump inhibitor therapy: a prospective study in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 2010 Jun;45((6)):618–24. doi: 10.1007/s00535-010-0207-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zelter A, Fernández JL, Bilder C, Rodríguez P, Wonaga A, Dorado F, et al. Fundic gland polyps and association with proton pump inhibitor intake: a prospective study in 1,780 endoscopies. Dig Dis Sci. 2011 Jun;56((6)):1743–8. doi: 10.1007/s10620-010-1493-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miyamoto S, Kato M, Matsuda K, Abiko S, Tsuda M, Mizushima T, et al. Gastric hyperplastic polyps associated with proton pump inhibitor use in a case without a history of Helicobacter pylori infection. Intern Med. 2017;56((14)):1825–9. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.56.8040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stockbrügger RW, Menon GG, Beilby JO, Mason RR, Cotton PB. Gastroscopic screening in 80 patients with pernicious anaemia. Gut. 1983 Dec;24((12)):1141–7. doi: 10.1136/gut.24.12.1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Okazaki Y, Kotani K, Higashi Y. Vanishing gastric hyperplastic polyps. BMJ Case Rep. 2019:12e231341. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2019-231341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anjiki H, Mukaisho KI, Kadomoto Y, Doi H, Yoshikawa K, Nakayama T, et al. Adenocarcinoma arising in multiple hyperplastic polyps in a patient with Helicobacter pylori infection and hypergastrinemia during long-term proton pump inhibitor therapy. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2017 Apr;10((2)):128–36. doi: 10.1007/s12328-017-0714-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ji F, Wang ZW, Ning JW, Wang QY, Chen JY, Li YM. Effect of drug treatment on hyperplastic gastric polyps infected with Helicobacter pylori: a randomized, controlled trial. World J Gastroenterol. 2006 Mar;12((11)):1770–3. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i11.1770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amarapurkar AD, Amarapurkar D, Choksi M, Bhatt N, Amarapurkar P. Portal hypertensive polyps: distinct entity. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2013 May;32((3)):195–9. doi: 10.1007/s12664-013-0324-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kara D, Hüsing-Kabar A, Schmidt H, Grünewald I, Chandhok G, Maschmeier M, et al. Portal hypertensive polyposis in advanced liver cirrhosis: the unknown entity? Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Aug;2018:2182784. doi: 10.1155/2018/2182784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haruma K, Kamada T, Manabe N, Suehiro M, Kawamoto H, Shiotani A. Haruma k, Kamada T, Manabe N,Suehiro M, Kawamoto H, and Shiotani A. Old and new gut hormone, gastrin and acid suppressive therapy. Digestion. 2018;97((4)):340–4. doi: 10.1159/000485734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tanaka M, Kataoka H, Yagi T. Proton-pump inhibitor-induced fundic gland polyps with hematemesis. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2019 Apr;12((2)):193–5. doi: 10.1007/s12328-018-0908-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haruma K, Yoshihara M, Sumii K, Tari A, Watanabe C, Kodoi A, et al. Gastric acid secretion, serum pepsinogen I, and serum gastrin in Japanese with gastric hyperplastic polyps or polypoid-type early gastric carcinoma. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1993 Jul;28((7)):633–7. doi: 10.3109/00365529309096102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haruma K, Ito M. Review article: clinical significance of mucosal-protective agents: acid, inflammation, carcinogenesis and rebamipide. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003 Jul;18(Suppl 1):153–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.18.s1.17.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]