Abstract

Objective.

Children in low-income, urban neighborhoods are at high risk of exposure to violence (ETV) across settings and subsequent posttraumatic stress symptoms (PTSS). Little research has examined how multiple forms of ETV co-occur and relate to variations in children’s posttraumatic responses. Furthermore, previous research primarily uses variable-centered methods, which can obscure person-level differences. The current study used person-centered methods to derive commonly occurring patterns of ETV by examining frequency of witnessing and victimization across family, school, and community contexts. The current study related profiles of ETV to demographic variables and PTSS, with the goal of obtaining nuanced representations of urban children’s experiences of, risk factors for, and responses to violence.

Method.

Patterns of ETV were examined in a sample of 239 African American 7th grade youth using latent profile analysis. Profiles were related to demographic variables and PTSS using logistic regression.

Results.

Results showed three profiles: Low (N = 130, 54.4%), Moderate (N = 87; 36.4%), and High (N = 22; 9.2%) Exposure groups. The High Exposure group showed the highest levels of PTSS. The Moderate group showed the lowest levels of all PTSS, except dissociation. In contrast, the Low Exposure group showed significantly higher numbing and hypervigilance than the Moderate Exposure group.

Conclusions.

Results support a dose-response model of ETV and PTSS, but implicate situational factors (e.g., setting) as important in understanding posttraumatic responses. The systematic variation in ETV and subsequent differences in PTSS expression illustrate the need for individualized trauma-informed intervention and thorough screenings in low-income, urban neighborhoods.

Keywords: children, African American urban adolescents, interpersonal violence, posttraumatic stress symptoms, latent profile analysis

Urban African American youth experience disproportionately higher risk for exposure to violence (ETV) compared to their peers (Sumner, Mercy, Dahlberg, Hillis, Klevens, & Houry, 2015). Rates of community ETV are especially high, with some estimates suggesting African American youth in high-risk neighborhoods experience one violent incident per week in their community, on average (Richards et al., 2015). Following ETV, children are at risk for developing posttraumatic stress symptoms (PTSS), such as numbing, hypervigilance, avoidance, intrusive thoughts, and dissociation (Finkelhor, Ormrod, & Turner, 2007). Prevention and intervention efforts can reduce children’s risk of developing PTSS; yet, these efforts are dependent upon how well researchers and clinicians understand children’s experiences of ETV, their responses, and the variability across individuals. The current study seeks to present a cohesive, comprehensive representation of children’s ETV across settings, incorporating individual differences in ETV (including proximity to exposure [i.e., witnessing or victimization] and frequency of exposure), with the goal of understanding patterns of ETV that frequently co-occur for high-risk youth and their related PTSS profiles through a person-oriented framework.

ETV across Contexts

The ecological-transactional model posits that different environments are “nested” within each other in a way that allows each environment to exert influences on individuals and to interact with the other systems, with individuals also exerting their own influence on their environments (Cicchetti & Lynch, 1993). When applied to children’s ETV, this model emphasizes the need to consider children’s contexts simultaneously, rather than in isolation. Although it is well-recognized that family, school, and community settings are three of the most salient contexts for children’s development, ETV within these contexts is often studied separately to ascertain the unique etiology or consequences of each type of exposure (Hamby & Grych, 2013). Underlying this compartmentalization of different types of ETV is the assumption that these phenomena are “theoretically distinct” from each other, each stemming from singular risk factors and creating its own set of effects (Bidarra, Lessard, & Dumont, 2016). However, certain risk factors, such as low socioeconomic status (SES), male gender, and single-parent households, increase children’s risk for ETV across multiple environments, or polyvictimization (Finkelhor, Ormrod, & Turner, 2007). When only one environment is examined, it is difficult to understand how ETV across environments may add to or interact with one another to produce negative outcomes. As a result, such studies may inflate the contribution of one type of ETV to poor mental health. In addition, single-setting studies lack the ability to identify groups of children who are multiply victimized due to overlapping risk factors, such as low SES. Given that up to 48% of children in the United States qualify as polyvictims, there is a pressing need to accurately represent children’s ETV (Finkelhor, Ormrod, & Turner, 2007).

Effects of polyvictimization on PTSS.

Researchers and clinicians also must have an accurate understanding of how these exposures impact children’s PTSS. In general, research supports a dose-response relation between ETV and PTSS (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). In fact, experiencing multiple victimizations is more predictive of PTSS than any single victimization experience, regardless of the severity (Finkelhor, Ormrod, & Turner, 2007). Similarly, closer proximity to a trauma (i.e., victimization vs. witnessing) generally predicts higher risk of PTSS (May & Wisco, 2016), although findings have been mixed (Fowler, Tompsett, Braciszewski, Jacques-Tiura, & Baltes, 2009). In addition to predicting overall PTSS, frequency of and proximity to trauma may predict the presence and severity of specific symptom clusters, as trauma-related disorders are heterogeneous in symptom expression across individuals (APA, 2013). For example, dissociation is more common following a severe, prolonged, or repeated traumatic event, and when present, constitutes a distinct subtype of PTSD (APA, 2013).

Beyond frequency and proximity, researchers have hypothesized that heterogeneity in symptom severity and expression may be related to the type of trauma sustained (Bal & Jensen, 2007). For example, early childhood emotional abuse predicted symptoms of avoidance, re-experiencing, and arousal, whereas early sexual abuse only predicted re-experiencing symptoms (Sullivan, Fehon, Andres‐Hyman, Lipschitz, & Grilo, 2006). Yet, little research has expanded upon these theories to illustrate how the type of ETV across settings may relate to PTSS expression. This becomes especially important when examining a group of youth who are multiply exposed to violence, as different types of ETV can add to or interact with one another to exacerbate (or ameliorate) the effects of a single ETV. In one study, witnessing community violence actually attenuated the effects of witnessing domestic violence on depression, anxiety, and delinquency, likely due to desensitization (Mrug & Windle, 2010). Studies such as this suggest that a “dose-response” model alone may provide an over-simplistic representation of how distinct constellations of ETV can impact PTSS severity and expression. If PTSS expression varies predictably based on factors such as duration and type of ETV, researchers and clinicians can better understand how to predict, evaluate, and treat PTSS (Martin, Ryzin & Dishion, 2016).

Accounting for Diverse Experiences of ETV: Person-Centered Methods

Effective analysis of the co-occurrence of different types of ETV must account for two sources of variability: variation across contexts and across people. The former can be understood by using an ecological framework, which delineates between various settings, while nesting them within each other. Alternative methods for examining variation across contexts include examining cross-contextual interactions, which clarify the extent to which environments impact each other and the individual. The latter source of variability can be addressed by utilizing person-centered methods (Hamby & Grych, 2013). Person-centered analyses have been identified as a method that can elucidate whether subgroups exist for the exposure to and/or effects of violence (Gaylord-Harden, Dickson, & Pierre, 2016). Traditional variable-centered methods focus on the structure of a variable across persons, assuming comparable predictor-outcome associations across persons. In contrast, person-centered methods focus on response patterns within a person, with an underlying assumption of heterogeneity within a group (Laursen & Hoff, 2006). While variable-centered methods are well-suited to examine a wide range of associations across persons, person-centered methods may be more appropriate when considering multivariate outcomes, as these methods provide unique insight into the ways in which a diverse set of experiences can exist simultaneously and interact within an individual (Copeland-Linder, Lambert, & Ialongo, 2010).

Several studies have utilized person-centered methods to understand how violence can affect youth on an individual level (e.g., Copeland-Linder, Lambert, & Ialongo, 2010; Gaylord-Harden, Dickson, & Pierre, 2016; Ronzio, Mitchell, & Wang, 2011; Russell, Nurius, Herting, Walsh, & Thompson, 2010). The majority of these studies have focused on the experience of community violence. In each one, different predictors have been included to develop profiles of violence exposure, making it difficult to compare across studies. Lambert, Nylund-Gibson, Copeland-Linder, and Ialongo (2010) examined classes of community violence exposure, including witnessing and victimization, in a sample of low income, African American youth (mean age = 11.76 years). They found that 25% of the sample comprised a low exposure group, while 75% comprised a high exposure group. Depression and impulsive behavior were significantly higher for students in the high exposure group than the low exposure group in sixth grade; yet, these effects did not persist across time. Contrary to previous research, the authors found no gender differences in chronically high or low exposure to community violence. A later study examining witnessing community violence in a sample of African American mothers supported the high and low exposure groups, also finding depression and anxiety to be higher for the high exposure group (Ronzio, Mitchell, & Wang, 2011).

Building on this work, Gaylord-Harden, Dickson, and Pierre (2016) examined witnessing, direct victimization, and indirect victimization in a sample of low-income, urban African American adolescents (ages 11–15), and found three distinct classes of community victimization: 1) victimization, but low rates of witnessing; 2) a low exposure class, exhibiting low witnessing and low victimization; and 3) a high exposure class, exhibiting high witnessing, and both indirect and direct victimization. The victimization class constituted the majority of the sample (39%), and older students were more likely to be members of the high exposure class, with no gender differences between classes. Furthermore, while no anxiety differences emerged, depression was significantly higher for low exposure and victimization classes compared to the high exposure class, but not between low exposure and victimization classes, suggesting that desensitization may occur for those adolescents exposed to the highest levels of violence (Gaylord-Harden, Dickson, & Pierre, 2016). In a similar vein, Nylund, Bellmore, Nishina, & Graham (2007) examined witnessing and victimization of peer-to-peer violence, finding three distinct groups: high, low, and medium probability of peer victimization. In accordance with previous research, they found that the higher exposure groups reported higher levels of depression compared to the lower exposure group. Together, these results suggest frequently recurring patterns of high, moderate, and low levels of ETV within single categories of ETV, with worse outcomes associated with higher levels of ETV. Yet, many of them point toward a highly nuanced understanding of ETV, as different groups emerge depending on whether youth were victims, witness, or some combination of both.

While these studies offer a strong foundation for person-centered research for children’s ETV, gaps remain in the field’s understanding of how ETV varies across individuals during early adolescence. First, many of these studies used dichotomized violence exposure variables (e.g., Copeland-Linder, Lambert, & Ialongo, 2010; Gaylord-Harden, Dickson, & Pierre, 2016; Ronzio, Mitchell, & Wang, 2011; Russell, Nurius, Herting, Walsh, & Thompson, 2010), implicitly suggesting that a one-time victimization can be equated with re-victimization, or the re-occurrence of a particular type of violence over time (Hamby & Grych, 2013). Second, few of these studies examined both witnessing and victimization (e.g., Ronzio, Mitchell, & Wang, 2011); yet, both can impact youth and can do so in different ways. Third, few of these studies examined ETV across multiple relevant settings, with many focusing on only one form of violence (e.g., Gaylord-Harden, Dickson, & Pierre, 2016; Nylund Bellmore, Nishina, & Graham, 2007). By addressing these limitations, researchers and clinicians can be provided with more realistic and representative portrayals of children’s experiences of and responses to ETV.

Current Study

First, the current study aimed to examine patterns of ETV in a sample of low-income, urban African American youth to determine distinct profiles of frequency of witnessing and victimization across family, school, and community settings. Second, the current study aimed to relate ETV profiles to demographic variables (i.e., gender, SES, family structure) and PTSS, with the goal of elucidating risk factors and providing an in-depth understanding of how patterns of ETV are associated with trauma symptom clusters. By using person-centered methods, the current study sought to examine common patterns of ETV for African American youth in high-risk urban neighborhoods, as well as PTSS expression according to patterns of ETV.

Given participant demographics, community ETV was expected to be the most frequently reported ETV. Our hypotheses were as follows: Hypothesis 1: Four patterns of ETV would emerge: (A) High witnessing and victimization across all three settings, (B) Low witnessing and victimization across all three settings, (C) High community witnessing and victimization, (D) High community witnessing only. The four hypothesized groups reflect a commonly recurring theme in person-centered research of high, moderate, and low ETV groups, with differences according to how the ETV is experienced. Hypothesis 2: Groups A and C would include more males, more single parent households, fewer parent figures, and lower SES relative to Groups B and D. Due to the limited (and conflicting) findings for these correlates in person-oriented research, Hypothesis 2 reflects the current understanding from variable-centered research that the aforementioned variables may serve as risk factors for polyvictimization (Finkelhor, Ormrod, & Turner, 2007). Hypothesis 3: Group A and C would show the highest levels of PTSS (i.e., dissociation, numbing, avoidance, intrusion, hypervigilance), followed by Group D, and finally by Group B, reflecting an additive effect of ETV on PTSS across symptom clusters. Given the lack of specificity in the literature examining the effects of ETV on PTSS, no specific predictions were made regarding how level of specific symptom clusters would vary according to group.

Method

Participants

A sample of 268 low-income, urban African American 6th grade students (59.0% female, M = 11.65 years) was recruited from six urban public schools for a three-year longitudinal study examining community ETV. The preceding year’s published crime statistics were used to select schools based on location in low-income, high-crime neighborhoods. Data were collected once each school year from 1999–2001, with the current study examining data collected in 2000. About 58% of students approached agreed to participate, which is consistent with previous studies utilizing a similar sample (Cooley-Quille, Turner, & Beidel, 1995), and 95% of students continued into the second year of the study (N = 254, M = 12.57 years). The current study examines only data from year two of the larger study, as this was when the measures of interest were administered, with 239 students completing the ETV measure (59.0% female, M = 12.55 years, SD = 0.68). Consistent with neighborhood demographics, the median annual family income was between $10,000 and $20,000. Most parents reported having at least a high school degree (83%), with 10% having a college, post-graduate, or professional degree. The median household size was 5 people, and 48% of participants came from one-parent homes. There were no significant group differences in parents’ education, marital status, annual income, baseline PTSS, or baseline community ETV between students who continued in the study and those lost to attrition (Deane, Richards, Mozley, Scott, Rice, & Garbarino, 2018; Goldner, Peters, Richards, & Pearce, 2011).

Procedures

The study was approved by the IRB at Loyola University Chicago. After written child assent and parent consent were obtained, students responded to questionnaires administered by trained research assistants over the course of five consecutive days in exchange for a $20 gift card or toy. At the same time, parents completed a survey in exchange for a $20 gift card.

Measures

Demographics.

Family structure and parent income were obtained through parent-report surveys. Due to high amounts of missing data, relevant child-report variables were utilized to supplement parent-reported information for family structure and parent income. Parent- and child-report variables were examined separately and were not combined. Child-report variables included gender, number of people residing in the child’s home, number of commodities (e.g., TV, radio) owned by the family, and whether the child shared a bedroom.

Exposure to violence.

A 25-item revised version of the My Exposure to Violence Scale was used (Buka, Selner-O’Hagan, Kindlon, & Earls, 1997), which asked participants to rate the frequency of their lifetime exposure to a series of violent events on a scale from 0 (never) to 4 (four or more). The witnessing subscale consisted of 13 items (e.g., “Have you seen someone else being hit, kicked, or beat up?”), and the victimization scale consisted of 12 items (e.g., “Have you been threatened with a knife or a gun?”). After the initial question, the measure included follow-up questions (i.e., “Who did it?” and “Where?”). The original measure demonstrated good test-retest reliability (r =.75 to .94) and construct validity (Selner‐O’Hagan, Kindlon, Buka, Raudenbush, & Earls, 1998). The 25-items examined in the current study assessed categories of exposure including; physical abuse and fighting, sexual assault, injury resulting from weapons, being chased, target of gun violence, discovering a corpse, and verbal threats of violence. An item regarding hearing gunshots was specific to the witnessing subscale.

In the current study, responses to follow-up questions were used to code the type of violent act into (1) family violence, (2) school violence, or (3) community violence using a coding scheme developed by the first author and reviewed by the second author. Violence was determined to be family violence if it occurred inside the child’s home/yard or in a relative’s home and by someone the child knew (either immediate family or other person with whom the child had a relationship). The variable was not limited strictly to biological family. School violence was determined to be violent acts committed on school grounds and perpetrated by someone the child knew (CDC, 2016). Community violence was comprised of acts that were committed outside of home and school. Additionally, acts that occurred inside the home/yard, a relative’s home, or school grounds and were perpetrated by someone the child did not know were considered to be community violence (WHO, 2002), in recognition that community violence often permeates private residences and educational settings. Of note, the ETV measure allowed children to report only one perpetrator and place, even in instances where the event may have occurred with more than one perpetrator or in more than one place. The witnessing and victimization subscales were preserved within each setting, producing six distinct count variables: family witnessing, family victimization, school witnessing, school victimization, community witnessing, and community victimization. Internal consistency was low for both scales (αwitnessing = .746, αvictimization = .491), but low internal reliability should not discourage the use of these scales, as internal reliability for ETV measures is potentially misleading because ETV is not a unitary construct (Netland, 2001).

Posttraumatic stress symptoms.

PTSS were assessed using the Trauma Symptom Questionnaire (TSQ), a measure adapted from Checklist of Child Distress Symptoms (CCDS; Richters & Martinez, 1993) and the Trauma Symptom Checklist for Children (TSCC; Briere, 1996) in order to include items across 5 symptom clusters considered clinically important for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The original TSCC displayed good concurrent and discriminant validity (Brierre, 1996), while the CCDS displayed good concurrent validity and test-retest reliability (Martinez & Richters, 1993). The final measure included 25 items and 5 subscales: dissociation (5 items, α = .880), numbing (5 items, α = .800), avoidance (2 items, α = .858), hypervigilance (5 items, α = .762), and intrusion (8 items, α = .915). Participants rated their levels of PTSS each day for five consecutive days on a scale ranging from 0 (not true at all) to 3 (very true for me), and their responses were averaged to obtain scores within each domain. Data were collected in this manner to examine daily PTSS, which was the focus of the larger project (Ortiz, Richards, Kohl, & Zaddach, 2008). Although the measure does not provide a clinical cut-off score, the clinical significance of each symptom cluster can be best understood within the context of current Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition criteria, which require either one or two persistent symptoms for each cluster (DSM-5; APA, 2013). While the symptom clusters described in the DSM-5 differ slightly from the ones included in this measure, it is suggested that participants who reported at least one persistent symptom in each category (e.g., ratings of 2 or 3 on item per cluster) were more likely to meet criteria for PTSD. If a participant were to endorse one symptom in each cluster as the maximum value of 3 (very true for me), the average score for each cluster would be: Dissociation = 0.6; Numbing = 0.6; Avoidance = 1.5; Hypervigilance = 0.6; and Intrusion = 0.34.

Data Analysis

Of the 244 students who completed the ETV measure, 16.6% did not complete the follow-up items on 1 or 2 items, which prevented ETV from being coded into setting. These 1 or 2 items were excluded from the total ETV scores for these participants. In addition, 2.0% of the sample (n = 5) did not complete follow-up items to 3 or more items, precluding coding into setting. The ETV scores for these 5 participants were determined to misrepresent their total ETV, and these participants were excluded from analyses, for a final sample of 239 participants. Mplus analyses for Hypotheses 2 and 3 used listwise deletion. For Hypothesis 2, parent-report data was available for 69.0% of participants (N = 165). In the vast majority of cases, data were missing for the entire wave, rather than for a single variable. As such, data imputation was inappropriate. Child-report proxy variables were used to supplement parent-report data when available, as there were no missing data for these variables. For Hypothesis 3, PTSS variables were missing for two participants. Missing data for income, marital status, family structure, parent education, or PTSS did not depend upon participants’ level of ETV.

Profiles of ETV were obtained using latent profile analysis (LPA) in Mplus (Version 7.4, Muthén & Muthén, 2015), which uses underlying latent classes to explain the relationship among observed, continuous dependent variables (latent indicators) (Muthén & Muthén, 2015). The current study utilized the six ETV variables as predictors to identify similar response patterns among individuals, beginning with a one-profile solution and adding on until the best fitting solution was reached. A series of statistics were examined to choose the most appropriate number of profiles, including Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC), sample-size adjusted BIC, entropy, and bootstrap parametric likelihood ratio test (BLRT) (Ram & Grimm, 2009; Nylund, Asparouhov, & Muthén, 2007). Consistent with past studies (e.g., Műllerová, Hansen, Contractor, Elhai, & Armour, 2016), the correct number of classes also was based on the smallest derived class size. Any solution with a class less than 5% of the sample was rejected as it may be “over-fitting” the data and less likely to be replicated. The sample size was likely adequate to detect medium to large effects with 80% power for BLRT but significantly underpowered to detect small effects (Dziak, Lanza, & Tan, 2014).

To achieve the second aim of the study, the demographic correlates of group membership were examined as auxiliary variables using the recommended multinomial logistic regression procedures in Mplus (Asparouhov & Muthén, 2015). Categorical variables (e.g., gender, parent marital status), were treated as covariates in the model to estimate the distribution across classes using the procedure DCAT in Mplus. To assess continuous distal variables (e.g., SES, number of people in home, PTSS), the recommended three-step estimation procedure (DU3STEP) was used, which estimates the means of continuous variables across classes, accounting for uncertainty in group membership by correcting for classification-error. When significant changes in group membership occurred, BCH was used instead of DU3STEP, which uses a weighted multiple group analysis that makes class shifting impossible (Asparouhov & Muthén, 2015). Both methods of difference testing have performed relatively well with non-normal continuous distal outcomes (Asparouhov & Múthen, 2015; Zhu, Steele, & Moustaki, 2017).

Results

Hypothesis 1: Latent Profile Analysis (LPA)

Descriptive statistics for ETV and PTSS variables are summarized in Table 1. It was hypothesized that a 4-class solution would best fit the data. LPA using maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors and chi-square showed the three-class solution resulted in lower AIC, BIC, and adjusted BIC, as well as a significant BLRT compared to the two-class solution, indicating that three classes fit better than two (Table 2). Entropy was slightly lower for three-class solution, though still very high (.90 vs. .91). Compared to the three-class solution, the four-class solution showed slightly lower AIC, BIC, and adjusted BIC, as well as slightly higher entropy. However, one of the four classes contained only 9 individuals (3.8%), putting it below the previously determined 5% threshold for the smallest acceptable group size. As such, the four-class solution was rejected, and the three-class solution was adopted as the best fitting model.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations for Exposure to Violence and PTSS Variables (N = 239)

| Variables | Range | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Fam. Wit. | 0–4 | 0.17 | 0.70 | - | |||||||||

| 2. School Wit. | 0–10 | 0. 50 | 1.36 | −.013 | - | ||||||||

| 3. Com. Wit. | 0–27 | 1.63 | 2.98 | .077 | .375** | - | |||||||

| 4. Fam. Vic. | 0–8 | 0.15 | 0.81 | .097 | .145* | .203** | - | ||||||

| 5. School Vic. | 0–5 | 0.12 | 0.55 | −.030 | .256** | .071 | −.031 | - | |||||

| 6. Com. Vic. | 0–14 | 0.59 | 1.48 | .013 | .382** | .649** | .271** | −.040 | - | ||||

| 7. Dissociation | 0–3 | 0.32 | 0.48 | .085 | .060 | .233** | .027 | −.036 | .089 | - | |||

| 8. Numbing | 0–2.48 | 0.31 | 0.42 | .014 | −.006 | .156* | .114 | −.009 | .115 | .629** | - | ||

| 9. Avoidance | 0–3 | 0.55 | 0.70 | .104 | −.059 | .145* | .072 | .005 | .054 | .479** | .535** | - | |

| 10. Hypervigilant | 0–2.40 | 0.38 | 0.44 | −.005 | −.039 | .146* | .090 | −.013 | .074 | .620** | .647** | .655** | - |

| 11. Intrusion | 0–2.88 | 0.29 | 0.47 | .026 | −.036 | .165* | .084 | −.048 | .097 | .731** | .693** | .629** | .826** |

Note.

p < .05,

p < .01

Table 2.

Fit Information for Latent Profile Analysis Models with 1–4 Classes

| Classes | Free parameters | Chi Square | df | AIC | BIC | Adj. BIC | Entropy | BLRT (p) | Smallest class size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6 | 921.99 | 38840 | 3157.12 | 3177.98 | 3158.96 | -- | -- | 100.0% |

| 2 | 13 | 1049.31 | 38840 | 2503.64 | 2548.83 | 2507.62 | 0.91 | <.001 | 40.2% |

| 3 | 20 | 1066.96 | 38836 | 2345.24 | 2414.77 | 2351.37 | 0.90 | <.001 | 9.0% |

| 4 | 27 | 861.52 | 38834 | 2228.53 | 2322.40 | 2236.82 | 0.91 | <.001 | 3.8% |

Note. AIC=Akaike Information Criterion, smaller is better; BIC=Bayesian Information Criteria, smaller is better; adjusted BIC=Sample-adjusted BIC, smaller is better; Entropy closer to 1 is better, BLRT=bootstrapped parametric likelihood ratio test (p values reported here).

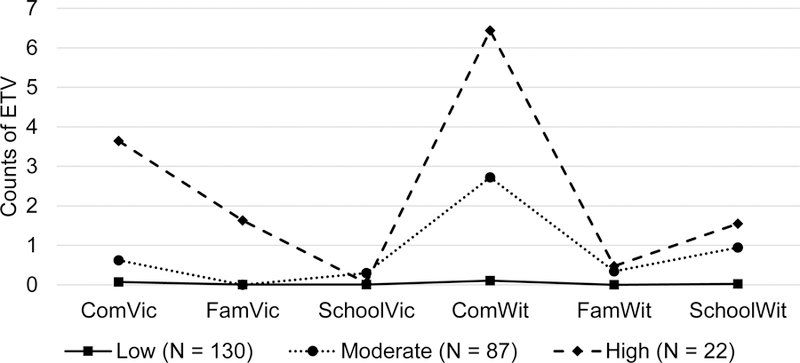

The final solution reflected three distinct profiles of children’s ETV, with the average counts of violence for each group illustrated in Figure 1. The largest profile (N = 130, 54.4% of the sample) was comprised of individuals reporting very low rates of witnessing and victimization across settings (Low Exposure group). The next largest group, (N = 87; 36.4% of the sample) was comprised of individuals who experienced relatively low to moderate rates of all forms of ETV, with moderate to high rates of witnessing community violence (Moderate Exposure group). The third and smallest group (N = 22; 9.2% of the sample) was characterized by high levels of both community witnessing and victimization, as well as moderate levels of school witnessing and family victimization (High Exposure group). This group showed rates of school victimization and family witnessing comparable to the other two groups.

Figure 1.

Latent profiles of ETV based on the 3-class solution

For the Low Exposure group, all types of ETV were significant indicators of group membership, except for family witnessing, as no one in this group endorsed witnessing violence in the family, resulting in zero variability for that indicator. For the Moderate Exposure group, only school victimization, community witnessing, and family witnessing were significant indicators of group membership. For the High Exposure group, community victimization and witnessing, along with school victimization were significant indicators.

Hypothesis 2: Demographic Correlates of Profiles

The hypothesis that gender, family structure, and income differ across profiles was examined using the Mplus procedures previously described. Results are summarized below.

Gender.

No gender differences across profiles emerged (N = 237; χ2(2) = 3.49, p = .18). The distribution of males and females appeared to be similar across the Low (conditional probability for males = .45), Moderate (conditional probability for males = .33), and High (conditional probability for males = .50) Exposure groups.

Family structure.

Parent-reported marital status (single parent vs. two parent homes) was reported by 165 parents. Results showed no significant differences across profiles (χ2(2) = 2.12, p = .346). Examination of the number of parent figures in the home (N = 155), including individuals such as grandparents, aunts, or uncles, showed no significant difference across groups (χ2(2) = 1.47, p = .480). However, the number of individuals in the home, as reported by the child (N = 222), showed significant difference across groups (χ2(2) = 7.57, p = .023). Post-hoc tests showed a significant difference between the Low and Moderate Exposure groups (χ2(1) = 7.33, p = .007), with the Low Exposure group having significantly more people in the home (M = 5.95) compared to the Moderate Exposure group (M = 4.84). Of note, there were no significant differences in the rates of missing parent data across ETV profiles.

Income.

Parent-reported total annual household income (N = 165) showed no significant differences across groups (χ2(2) = 0.86, p = .650). In addition, household annual income was divided by the number of people in the home to account for how many people the income supported. This showed no significant differences across groups (χ2(2) = 2.28, p = .320).

Child-report variables were used to approximate family SES (N = 239). Significant differences were found in the likelihood of children sharing a bedroom (χ2(2) = 14.04, p = .001). Post-hoc examination indicated the High Exposure group was most likely to share a room (conditional probability = .866), followed by the Moderate Exposure group (conditional probability = .581), and the Low Exposure group (conditional probability = .446). The High Exposure group differed significantly from the Low Exposure group (χ2(1) = 13.23, p < .001), and the Moderate Exposure group (χ2(1) = 4.67, p = .031), with the Low and Moderate Exposure groups trending towards significance (χ2(1) = 3.36, p = .067).

Children also reported on the number of commodities owned by their family (e.g., phone, television, computer). This was divided by the number of people in each house to account for differences in household size. Results showed a significant difference across groups (χ2(2) = 12.21, p = .002). Post-hoc tests showed that the Low Exposure group reported owning significantly more commodities per person than the Moderate Exposure group (χ2(1) = 7.28, p = .007) and the High Exposure group (χ2(1) = 11.64, p = .001). No significant differences were found between the Moderate and High Exposure groups in the number of commodities owned.

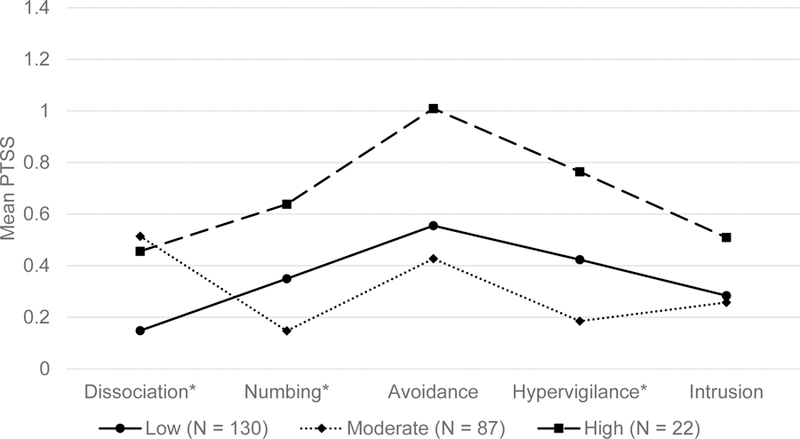

Hypothesis 3: Differences in PTSS across Profiles

The three-step estimation procedure for continuous variables (DU3STEP) was used to estimate the level of each PTSS cluster across profiles in Mplus, correcting for classification-error (N = 237). This procedure significantly changed group membership for the intrusion cluster, so the BCH procedure was used instead, as recommended by Asparouhov and Muthén (2015). Results, including group PTSS means, are illustrated in in Figure 2. Significant skew and kurtosis were observed for PTSS variables within the total sample and within profiles. Additional description of the distribution of the PTSS variables is provided as supplemental material.

Figure 2.

Mean levels of PTSS by latent profile. To better understand the clinical relevance of average scores, consider the following: If a participant were to endorse one symptom in each cluster as the maximum value of 3 (or “very true for me”), the average score for each cluster would be: Dissociation = 0.6; Numbing = 0.6; Avoidance = 1.5; Hypervigilance = 0.6; and Intrusion = 0.34.

Results indicated significant differences across groups for dissociation (χ2(2) = 27.70, p < .001), numbing (χ2(2) = 22.46, p < .001), and hypervigilance (χ2(2) = 31.49, p < .001). Post-hoc tests showed significant differences in dissociation between the Low and Moderate Exposure groups (χ2(1) = 20.55, p < .001) and between the Low and High Exposure groups (χ2(1) = 5.72, p = .017). For numbing, significant differences were found between the Low and Moderate Exposure groups (χ2(1) = 10.04, p = .002), and between the Moderate and High Exposure groups (χ2(1) = 10.84, p = .001). The difference between the Low and High Exposure groups was trending towards significance (χ2(1) = 3.01, p = .083). For hypervigilance, significant differences were found between the Low and Moderate Exposure groups (χ2(1) = 16.52, p < .001), between the Moderate and High Exposure groups (χ2(1) = 17.40, p < .001), and between the Low and High Exposure groups (χ2(1) = 5.43, p = .020). No differences across groups were found for avoidance (χ2(2) = 4.69, p = .096) or intrusion (χ2(2) = 4.17, p = .107).

Discussion

The rates of ETV found in the current study are comparable to other studies (e.g., Finkelhor, Turner, Shattuck, & Hamby, 2013), with community violence as the most commonly reported form of ETV. Hypothesis 1 posited that four distinct groups would emerge. The three distinct profiles of ETV that were found resembled the four hypothesized groups, though not perfectly. First, the Low Exposure group (54.4%) showed very low ETV across all settings, again consistent with studies that have found roughly 50% of children to report very low rates of ETV (e.g., Finkelhor, Turner, Shattuck, & Hamby, 2013). Second, the Moderate Exposure group (36.4%) showed moderate to high rates of witnessing community violence, with slightly higher rates of family witnessing and school victimization compared to the Low Exposure group. Third, the High Exposure group (9.2%) exhibited high community witnessing and victimization, with moderate school witnessing.

While the four-class solution displayed slightly better fit compared to the three-class solution, it was rejected based on small class size. The four-class solution had Low and High Exposure classes similar to the three-class solution, but it separated the Moderate group into two distinct classes: one with higher community exposure and one with higher school exposure. The current study’s sample size likely lacked the power to distinguish between these two classes given their low separation. Although the addition of a fourth class may enhance our theoretical understanding of children’s ETV, the three-class solution provides greater clinical utility. While other person-oriented studies have found similar groups (e.g., Low Exposure class, Gaylord-Harden, Dickson, & Pierre, 2016), direct comparisons across studies are difficult, as each study included a unique set of predictors and few examined ETV across contexts.

The demographic correlates of the profiles provide some support for the external validity of the three profiles, offering partial support for Hypothesis 2 (i.e., demographic correlates would vary across profiles). Although no differences in parent-reported income were found, children in the High Exposure group were significantly more likely to share a bedroom compared to the Low and Moderate Exposure groups, and children in the Low Exposure group owned significantly more commodities per person (e.g., television) than children in the Moderate or High Exposure groups. Together, these suggest meaningful differences in economic risk across profiles. The Moderate and High Exposure groups appear to experience similar levels of economic hardship, with the Low Exposure group experiencing less economic hardship, comparatively. This follows a logical pattern, especially given the link between poverty and ETV (Sumner et al., 2015). However, it must be noted that child-report proxy variables are imperfect indicators of SES; thus, results should be interpreted with caution. In general, parent-report variables are preferred for SES variables; yet, the current study failed to find differences in parent-report income and marital status. This likely was due to missing data, but it also may have been due to limited variability in actual income levels, as participants were chosen based on their residence in low-income areas. In either case, the limited group differentiation based on SES and proxy SES variables suggests explanations for ETV cannot be limited to SES and must be understood as multifactorial, intersecting, and highly complex. It is also imperative to consider the reality and ubiquity of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) for youth in this population. Evidence suggests that ACEs (e.g., emotional neglect, child maltreatment, incarcerated family members) often cluster in a child’s life and can co-occur with ETV, thus making them important to incorporate into this multifactorial model (Cronholm et al., 2015).

The High Exposure group displayed markedly higher rates of community ETV compared to the other two groups. Given the higher rates of community ETV for this profile, it was surprising that no gender differences were found. However, this finding mimics the results reported by Gaylord-Harden, Dickson, and Pierre (2016), which showed no gender differences in community witnessing or victimization when using person-centered methods. Compared to variable-centered methods, person-centered methods may more accurately reflect naturally occurring patterns of ETV within children’s environment (Gaylord-Harden, Dickson, & Pierre, 2016). By encompassing violence across multiple ecosystems, the current study also may have occluded gender differences that exist for community ETV, especially given that males and females tend to demonstrate similar levels of ETV in family and school settings.

The levels of school and family ETV appeared to vary within the High Exposure group, as not all ETV in these settings were significant indicators of group membership. Most notably, family victimization was not a significant indicator, despite the higher mean score for this group compared to the other two. These results suggest that while some forms of ETV may cluster together to show distinct profiles of ETV for subgroups of children, significant variability exists for risk in certain domains within each group. Of note, the low rates of family violence reported in the current study may be due, in part, to differential reporting bias for certain types of ETV. One challenge in measuring children’s lifetime ETV is bias in recalling early life events. Family violence, which tends to have an earlier age of onset compared to other forms of violence (Graham-Bermann, & Perkins, 2010), may be less likely to be recalled by adolescents. In contrast, community violence, which becomes more salient as youth spend increased amounts of time outside the home, may be more likely to be recalled.

As expected, the High Exposure group showed the highest levels of all PTSS, with the exception of dissociation. This offers support for Hypothesis 3, which posited a dose-response model of ETV and PTSS, with trauma symptoms increasing as ETV increases. However, the findings of the current study do not provide unbounded support for the dose-response model. The Moderate Exposure group, which consisted of youth primarily reporting moderate community witnessing, endorsed lower levels of PTSS than the Low Exposure group, except dissociation. It may be that the Moderate Exposure group experienced desensitization to violence, leading to reduced distress. While desensitization typically applies to children with the most severe ETV, many factors (e.g., proximity to and specific combinations of ETV) are crucial in determining desensitization response (Mrug & Windle, 2010). Alternatively, the relatively low levels of PTSS for the Moderate Exposure group may represent a resilient response to ETV. These youth may possess personal strengths and external supports that allow them to cope with distress in a healthy, positive manner that arrests the development of clinically significant symptomology. In fact, a proportion of participants in the Low and Moderate Exposure groups endorsed no symptoms (9.2% and 5.7%, respectively), suggesting resilience despite low to moderate ETV. In contrast, 100% of participants in the High Exposure group reported at least one symptom.

It must be noted that, despite the lower levels of some PTSS, the Moderate Exposure group displayed levels of dissociation comparable to the High Exposure group. Dissociative symptoms, including derealization and depersonalization, are correlated with increased frequency and severity of traumatic experiences (APA, 2013). Although the Moderate Exposure group may not meet full diagnostic criteria for PTSD, the presence of heightened dissociative symptoms for 36.4% of the sample is sobering, as this conveys increased risk for PTSD (APA, 2013). The presence of dissociation for the High Exposure group (roughly 10% of the sample) also is of concern, as children who display dissociative features in PTSD show poorer prognosis, including higher risk of suicide and greater functional impairment (Stein et al., 2013).

No significant differences in avoidance were found across groups, suggesting that ETV type and frequency may not be determining factors in the development of avoidance. Rather, children residing in high-violence communities may learn to avoid thinking about trauma and visiting dangerous areas of their neighborhoods, simply as a matter of self-preservation and safety. Similarly, no differences were found for intrusion. Previous research has found avoidance and intrusion symptoms to be more strongly related to early childhood emotional abuse than physical abuse (Sullivan et al., 2006). The ETV measure focused on physical abuse; as such, it may have obscured differences based on emotional abuse.

Determining exact clinical relevance of the PTSS findings is somewhat complicated by the fact that the PTSS measure did not provide clinical cut-off scores for symptom clusters. Yet, by understanding these average scores in the context of current DSM-5 criteria, it is possible to conjecture regarding the average functioning of each group. Current DSM-5 criteria require the following for a diagnosis of PTSD: one stressor, one intrusion symptom, one avoidance symptom, two negative alterations in cognition/mood, and one alteration in arousal that have been present for more than one month and create functional impairment or distress. In the current study, a participant who endorsed one intrusion symptom at the highest possible value (3) would have shown an average score of .38 for the intrusion cluster. While this may seem low, the participant actually endorsed sufficient intrusion symptoms to qualify for a diagnosis of PTSD, assuming all other criteria were met. With this understanding, it is possible that many members of the High Exposure group met criteria for PTSD, and many of the members of the Low and Moderate Exposure groups were functioning in the “at-risk” range. Unfortunately, the percent of youth who met full criteria for PTSD in the current study is impossible to determine with any certainty, given the limited evaluation of several criteria.

Finally, the presence of a Low Exposure group comprised of over half of the sample is interpreted as a positive finding for organizations with limited resources struggling to attend to the needs of youth in high-risk, urban communities. Yet, despite low levels of direct witnessing and victimization experiences across settings, these children still appeared affected by violence, as many of their self-reported PTSS were higher than those of the Moderate Exposure group. Many of these children may experience the effects of chronic violence in their communities implicitly, by fearing for their safety while walking to school or learning about victimizations of friends or family. In this way, even distal exposures can create a culture of fear and destabilize children’s perceptions of safety and control, leading to the development of PTSS and other detrimental outcomes (Fowler et al., 2009). These children may not demonstrate the need for the most intensive interventions; yet, practitioners should consider which resources may benefit these children, as even their distal proximity to ETV may put them at risk for developing PTSD or other another disorder (May & Wisco, 2016).

Limitations

By examining frequency of ETV across three settings and two modes of exposure (i.e., witnessing and victimization) using a person-oriented framework, the current study was sensitive to differences between single and chronic exposures. The current study expanded upon previous research by incorporating three separate settings to provide a more comprehensive picture of how ETV is present in the lives of African American youth residing in high violence, low-income neighborhoods, a historically underrepresented group in research. The profiles obtained reflect the interplay between multiple ecosystems for each individual, in line with the ecological-transactional approach, which underscores the relatedness between systems and the individual.

The current study was subject to limitations, as well. The format of the ETV measure may have caused children to report only the most salient or recent ETV, resulting in under-reporting of their total ETV. In addition, certain forms of ETV were not explicitly studied (e.g., dating or police violence), nor were other adverse experiences that could have impacted PTSS (e.g., natural disasters, neglect). Future studies should incorporate these variables. Furthermore, the 58% response rate during participant recruitment, while consistent with previous studies, also poses a limitation. It may be that youth who refused to participate were at higher risk for ETV and more likely to live in poverty. Although we found no differences in several important variables between those who continued and those who were lost to attrition, it may be that those who were lost experienced significant stressors following the first wave of data collection. Thus, the results may not represent the experiences of very high-risk youth.

Small sample size was a significant limitation, as well, as the current study was significantly underpowered to detect small differences in group membership. As such, the current study was limited in its ability to identify classes with few members and/or low separation from other classes. Future studies with larger samples may be better equipped to detect such classes. The current study also used an archival data set from approximately 20 years ago. While rates of violence in the United States have decreased since the early 1990s, the burden of violence continues to be disproportionately experienced by African American adolescents in urban areas (Sumner et al., 2015). Many urban youth today may experience slightly lower rates of ETV than the youth in the current study; yet, the results provide a foundation upon which future studies can build so as to better address the epidemic of violence for high-risk youth. Additional limitations include missing data, cross-sectional design, and limited generalizability to populations beyond African American adolescents from low income communities. Further research should evaluate stability of profiles across demographic groups and engage very high-risk individuals in order to ensure a representative sample.

Clinical Implications

The High Exposure group, roughly 10% of the sample, reported significantly higher rates of numbing, dissociation, and hypervigilance compared to their peers, which appears to be in direct proportion to the comparatively higher rates of violence. It is clear that the High Exposure group would benefit most from mental health resources; however, this group also showed lower indicators of SES, suggesting they may have the least access to resources. Interventions should continue to develop creative ways to provide resources to the most vulnerable populations, as well as services that are readily accessible in the midst of high poverty.

Comparatively, the Moderate Exposure group (36%) did not display elevated PTSS across the board, despite high community witnessing. If this proportion of children do, in fact, express limited PTSS after witnessing community ETV, it may be difficult to identify them as “trauma-exposed” in school or clinical settings. Yet, their elevated levels of dissociation indicate they are at risk of developing PTSD. This underscores the need for prevention efforts in high-risk, urban communities to assess both witnessing and victimization across settings (in particular, the community) in order to accurately gauge children’s risk of developing PTSD.

The current study also draws attention to the heterogeneity of ETV within a high-risk sample. Even within profiles, certain forms of ETV appeared to be less salient, such that there was no “characteristic” level of exposure for the profile in those domains. Interventions that target high-risk community samples must recognize that children likely require varying degrees of resources and intervention, and they should tailor programs to meet individual needs. The lack of significance for family victimization as a predictor for the High Exposure group serves as a reminder that even children who are at high risk of ETV may not be exposed to ETV across all settings. As such, practitioners should seek to understand which environments may serve as strengths and safe spaces for youth and capitalize on them in designing treatments for youth.

Research Implications

The current study provided support for the theory that multiple forms of ETV vary systematically for African American youth in high violence, low-income communities. The current study, and person-centered methods, in general, advocate for the perspective that individual differences within a population are not negligible; rather, understanding such heterogeneity can guide theory and inform clinical approaches to best serve children affected by violence. Future studies should continue to explore the interrelations of ETV across perpetrators and settings, incorporating factors such as proximity to, frequency of, and variability in ETV. This includes explicit examination of cross-contextual interactions, which were beyond the scope of the current study. Future studies should seek to replicate the current findings with significantly larger sample sizes of high-risk youth in order to maximize the potential of finding small effects that may not have been detectible by the current study. In addition, future studies should examine conditions under which children display desensitization, resilience, or dose-response effects following ETV, incorporating a diverse sample to test generalizability across groups. In doing so, future research will continue to elucidate challenges faced by vulnerable youth while simultaneously pushing the field toward a more integrated understanding of ETV and its effects.

Supplementary Material

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Asparouhov T & Muthén B (2015). Auxiliary variables in mixture modeling: Using the BCH method in Mplus to estimate a distal outcome model and an arbitrary secondary model. Mplus Web Notes: No. 21. Retrieved from https://www.statmodel.com [Google Scholar]

- Bal A, & Jensen B (2007). Posttraumatic stress disorder symptom clusters in Turkish child and adolescent trauma survivors. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 16, 449–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bidarra Z, Lessard G, & Dumont A (2016). Co-occurrence of intimate partner violence and child sexual abuse: Prevalence, risk factors and related issues. Child Abuse & Neglect, 55, 10–21. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briere J (1996). Psychometric review of the Trauma Symptom Checklist−40. In Stamm BH (Ed.), Measurement of Stress, Trauma, and Adaptation Lutherville, MD: Sidran Press. [Google Scholar]

- Buka S, Selner-O’Hagan M, Kindlon D, & Earls F (1997). “My Exposure to Violence Interview” Admin & Scoring Manual, v. 3 Boston: Harvard School of Public Health. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2016). Understanding school violence Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/schoolviolence-factsheet.pdf

- Cooley-Quille MR, Turner SM, & Beidel DC (1995). Emotional impact of children’s exposure to community violence: A preliminary study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 34, 1362–1368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland-Linder N, Lambert S, & Ialongo N (2010). Community violence, protective factors, and adolescent mental health: A profile analysis. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology,39, 176–186. doi: 10.1080/15374410903532601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronholm P, Forke C, Wade R, Bair-Merritt M, Davis M, Harkins-Schwarz M, … Fein J (2015). Adverse childhood experiences: Expanding the concept of adversity. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 49, 354–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deane K, Richards M, Mozley M, Scott D, Rice C, & Garbarino J (2018). Posttraumatic stress, family functioning, and externalizing in adolescents exposed to violence: A moderated mediation model. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 47, 176–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dziak J, Lanza S, & Tan X (2014). Effect size, statistical power and sample size requirements for the bootstrap likelihood ratio test in latent class analysis. Structural Equation Modeling, 21, 534–552. doi: 10.1080/10705511.2014.919819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Ormrod R, & Turner H (2007). Polyvictimization: A neglected component in child victimization trauma. Child Abuse & Neglect 31:7–26. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Turner H, Shattuck A, & Hamby S (2013). Violence, crime, and abuse exposure in a national sample of children and youth: An update. JAMA Pediatrics, 167, 614–621. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler P, Tompsett C, Braciszewski J, Jacques-Tiura A, & Baltes B (2009). Community violence: A meta-analysis on the effect of exposure and mental health outcomes of children and adolescents. Development and Psychopathology, 21, 227–259. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409000145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaylord-Harden N, Dickson D, & Pierre C (2016). Profiles of community violence exposure among African American youth. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 31, 2077–2101. doi: 10.1177/0886260515572474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldner J, Peters TL, Richards MH, & Pearce S (2011). Exposure to community violence and protective and risky contexts among low income urban African American Adolescents: A prospective study. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40, 174–186. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9527-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham-Bermann S, & Perkins S (2010). Effects of early exposure and lifetime exposure to intimate partner violence (IPV) on child adjustment. Violence and Victims, 25(4), 427–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamby S, & Grych J (2013). The Web of Violence: Exploring Connections Among Different Forms of Interpersonal Violence and Abuse Springer: Dordrecht, NY. doi: 10.1007/97894-007-5596-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laursen B, & Hoff E (2006). Person-centered and variable-centered approaches to longitudinal data. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly (1982-), 52, 377–389. [Google Scholar]

- Martin CG, Van Ryzin MJ, & Dishion TJ (2016). Profiles of childhood trauma: Betrayal, frequency, and psychological distress in late adolescence. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice and Policy, 8, 206–213. doi: 10.1037/tra0000095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez P, & Richters J (1993). The NIMH community violence project: II. Children’s distress symptoms associated with violence exposure. Psychiatry, 56, 7–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May C, & Wisco B (2016). Defining trauma: How level of exposure and proximity affect risk for posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 8, 233–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrug S, & Windle M (2010). Prospective effects of violence exposure across multiple contexts on early adolescents’ internalizing and externalizing problems. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 51, 953–961. doi: 0.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02222.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Műllerová J, Hansen M, Contractor A, Elhai J, & Armour C (2016). Dissociative features in posttraumatic stress disorder: A latent profile analysis. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy doi: 10.1037/tra0000148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L, & Muthén B, (2015). Mplus User’s Guide: 7th Edition. Los Angeles, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Netland M (2001). Assessment of exposure to political violence and other potentially traumatizing events: A critical review. Journal of Traumatic Stress,14, 311–326. doi: 10.1023/A:1011164901867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nylund K, Asparouhov T, & Muthén B (2007). Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 14, 535–569. doi: 10.1080/10705510701575396 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nylund K, Bellmore A, Nishina A, & Graham S (2007). Subtypes, severity, and structural stability of peer victimization: What does latent class analysis say? Child Development, 78(6), 1706–1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz V, Richards M, Kohl K, & Zaddach C (2008). Trauma symptoms among urban African American young adolescents: A study of daily experience. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 1, 135–152. [Google Scholar]

- Richards M, Romero E, Zakaryan A, Carey D, Deane K, Quimby D, Patel N, & Burns M (2015). Assessing urban African American youths’ exposure to community violence through a daily sampling method. Psychology of Violence, 5, 275–284. [Google Scholar]

- Richters J, & Martinez P (1990). Checklist of Child Distress Symptoms: Parent Report National Institutes of Mental Health. [Google Scholar]

- Ronzio CR, Mitchell SJ, & Wang J (2011). The structure of witnessed community violence amongst urban African American mothers: Latent class analysis of a community sample. Urban Studies Research, 2011, 1–9. doi: 10.1155/2011/867129 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Russell PL, Nurius PS, Herting JR, Walsh E, & Thompson EA (2010). Violent victimization and perpetration: Joint and distinctive implications for adolescent development. Victims & Offenders, 5, 329–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein D, Koenen K, Friedman M, Hill E, McLaughlin K, … & Kessler R (2013). Dissociation in posttraumatic stress disorder: Evidence from the world mental health surveys. Biological Psychiatry, 73, 302–312. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.08.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan T, Fehon D, Andres‐Hyman R, Lipschitz D, & Grilo C (2006). Differential relationships of childhood abuse and neglect subtypes to PTSD symptom clusters among adolescent inpatients. Journal of Traumatic Stress,19, 229–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumner S, Mercy J, Dahlberg L, Hillis S, Klevens J, & Houry D (2015). Violence in the United States: Status, challenges, and opportunities. JAMA, 314, 478–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Report on Violence and Health: Summary Geneva: World Health Organization, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Steele F, & Moustaki I (2017). A general 3-step maximum likelihood approach to estimate the effects of multiple latent categorical variables on a distal outcome. Structural Equation Modeling, 1–14. doi: 10.1080/10705511.2017.1324310 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.