Abstract

Introduction

As Earth's population is rapidly aging, the question of how best to care for its older adults suffering from psychiatric disorders is becoming a constant and growing preoccupation. Depression is one of the most common psychiatric disorders among older adults, and depressed nursing home residents are at a particularly high risk of a decreased quality of life. The complex requirements of supporting and caring for depressed older adults in nursing homes demand the development and implementation of innovative clinical and organizational models that can ensure early identification of the disorder and high-quality multidisciplinary services for dealing with it. This perspective article aims to provide an overview of the literature and the state of the art of and the urgent need for research on the epidemiology and clinical treatment of depression among older adults.

Method

In collaboration with a medical librarian, we conducted literature and bibliometric reviews of published articles in Medline Ovid SP from inception until September 30, 2020, to identify studies related to depression, depressive symptoms, mood disorders, dementia, cognitive disorders, and health complications in long-term care facilities and nursing homes.

Results

We had 38,777 and 40,277 hits for depression and dementia, respectively, in long-term care facilities or nursing homes. The search equation found 536 and 1,447 studies exploring depression and dementia, respectively, and their related health complications in long-term care facilities or nursing homes.

Conclusion

Depression's relationships with other health complications have been poorly studied in long-term care facilities and nursing homes. More research is needed to understand them better.

Keywords: Older adults, Long-term residential care facilities, Depression, Evidence-based practice, Research, Bibliometrics

Introduction

The world's population is ageing rapidly, and unprecedented numbers of people are living well into old age [1, 2]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the total number of people aged 65 years or older will roughly double from 900 million in 2010 to 2 billion in 2030, or from around 12% of the population to 22% [3]. Switzerland is also feeling the effects of this global demographic transition, and by 2030 there should be 1,500,000 people aged 65 years or older in the country. Most older adults currently age in relatively good health [1, 4]. Some of them, however, will be highly exposed to different health problems which can lead to physiological decline, an increased prevalence of debilitating chronic diseases, and a loss of autonomy [5]. There are numerous reasons for and origins of older adults' greater exposure to health problems. In addition to debilitating somatic comorbidities, older adults are at a much greater risk of developing such significant mental pathologies as depression and dementia, which lead to a further loss of autonomy [4, 5]. In comparison to dementia, what is the body of knowledge in the literature on the relationship between depression or depressive symptoms and other health complications in long-term care facilities and nursing homes?

To provide a robust answer to our research question, we conducted our literature and bibliometric reviews in collaboration with a medical librarian. We examined published articles in Medline Ovid SP, from inception until September 30, 2020, to identify studies involving depression, depressive symptoms, mood disorders, dementia, and related health complications among older adults, aged 65 years or older, living in long-term care facilities and nursing homes. Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-methods studies were included; no language restrictions were applied. The following MeSH terms were employed to construct the search equations:

“Depression” OR “Depressive Disorder” OR “Depressive Disorder, Treatment-Resistant” OR “Depressive Disorder, Major” OR “Dysthymic Disorder” OR “Seasonal Affective Disorder” AND “Residential Facilities” AND “Health Status” OR “Health Status Indicators” OR “Health Surveys” OR “Health” OR “Mental Health” OR “Physical Fitness” OR “Physical Functional Performance” OR “Veterans Health” OR “Health Surveys” OR “Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System.”

“Dementia” NOT “AIDS Dementia Complex” AND “Residential Facilities” AND (“Health Status” OR “Health Status Indicators” OR “Health Surveys” OR “Health” OR “Mental Health” OR “Physical Fitness” OR “Physical Functional Performance” OR “Veterans Health” OR “Health Surveys” OR “Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System” OR “Health Status Indicators.” A total of 38,777 and 40,277 hits were found for depression and dementia, respectively, in long-term care facilities or nursing homes. The search equation found 536 and 1,447 studies exploring depression and dementia, respectively, and their related health complications in long-term care facilities or nursing homes.

Depression Epidemiology and Consequences

Dementia and depression are the most common psychiatric disorders among older adults. Depression will affect 7% of older adults around the world at least once in their lives, and one quarter of suicides involve people aged 65 years or older [6]. The International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems − 10th edition (ICD-10) defines a depressive episode as an affective mood disorder that is part of the group of mental and behavioral disorders. Depression can present with different levels of severity − i.e., mild, moderate, or severe depression − and can occur on one unique occasion during a life course or be recurring and chronic.

It is characterized by a fall in mood, energy, activity, and the capacity to concentrate, with a loss of interest, in general, and difficulty feeling pleasure. This is frequently associated with marked fatigue, sleep problems, a loss of appetite and self-esteem, or even feelings of guilt and worthlessness [7]. The WHO recently announced that depression is a very common mental disorder and the principal cause of disability worldwide, affecting more than 300 million people [8]. Depression is a particularly complex mood disorder among older adults, with diverse etiologies and high rates of comorbidity with other psychiatric and physical illnesses as well as with cognitive decline [9]. Depression increases older adults' perceptions of having an overall worse state of health and raises their rates of use of medical services and overall expenditure on healthcare. Although the majority of older adults suffering from one or more chronic diseases is treated at home [4], the physical and psychological weakening that these persistent health problems engender can eventually endanger their ability to remain in the community. These are associated with a high likelihood of institutionalization and mortality [10]. Older adults suffering from psychopathological and psychiatric problems face a significant risk of admission into a long-term residential care facility (LTCF) [10, 11].

Depression and LTCF

LTCF make up a significant part of the social care and healthcare system in numerous societies, particularly in high-income countries, where they provide for the needs of older adults who are losing their autonomy [12]. These LTCF ensure that the most dependent older adults receive care following their loss of functional capacities, which might result in multiple falls, undernutrition, isolation and loneliness, and psychological suffering.

Being placed in an LTCF is a significant challenge to an older adult. Individuals will have to face up and adapt as well as possible to the very different circumstances and conditions of living in such an institution. They will have to be resilient if they wish to integrate satisfactorily into this new lifestyle [13]. Even in well-managed LTCF, with support services and person-centered care, most residents would prefer to continue living autonomously in their own homes. [14].

Autonomy is often used interchangeably with the experience of having choices and being in control. A perceived lack of control is detrimental to physical and mental health. When nursing home residents feel that they have control over their activities, this has a positive influence on their health and well-being. Research findings support the idea that older people who perceive that they have a good quality of life also feel autonomous [15, 16]. Dependency is defined as receiving human assistance in at least 1 activity of daily living (ADL) or instrumental ADL (IADL). ADL are the basic personal functions of bathing, dressing, eating, getting in or out of a bed or chair, mobility, using the toilet, and continence. IADL are everyday activities that enable an individual to live independently in the community, i.e., preparing meals, shopping, managing money, using the telephone, or doing housework [17, 18, 19]. Research has demonstrated that it is possible to be autonomous while being dependent on assistance and that older people's perception of independence changes as they go through the process of functional decline. Therefore, it is not only their actual performance of activities that is important but also their ability to make meaningful choices and decisions.

Moving into an LTCF implies not only a potentially permanent change of domicile but also a very public transition from a state of self-sufficiency to some degree of dependency, perhaps in addition to fears about the loss of one's long-standing social network and friends after the move − indeed, these would all be significant stress factors at any age [20].

Residents have to face many simultaneous challenges, including medical problems, disability, disconnection from their homes and communities, and a great uncertainty about their future. At this stage, depression may occur or be reinforced among older adults who already have a history of mood disorders [21]. The institutionalization of older adults is very often associated with medical comorbidities, a reduced ability to perform the activities of daily living, greater levels of perceived pain, and even increased mortality [11]. Depression is a significant cause of weight loss and increased numbers of falls in LTCF [22, 23]; it can also be mistaken for apathy [24, 25]. Depressed persons often become less able to function, and the condition sometimes speeds them toward functional disability with a substantial loss of autonomy.

Depression is an extremely widespread psychiatric disorder in nursing homes; it has a negative impact on the quality of life and affects more than one fifth of nursing home residents. [26, 27]. Depending on the study, the measurement instruments used, and the country involved, the prevalence of depression reported among older adults in LTCF varies between 15 and 48% [6, 28, 29, 30]. Depression leads to mental and physical decline in innumerable older adults who could otherwise thrive and enjoy a better quality of life [8, 13]. Given that the prognosis for long-term care residents with depressive symptoms and disorders is poor, notably with lower recovery rates and higher mortality rates, this is a serious public health issue [20, 30]. Despite a clear depressive symptomatology, mental health problems are poorly recognized and diagnosed not only by the older adults themselves but also by the healthcare professionals working in LTCF [28]. The potential stigma surrounding mental illness can create some reticence to talking about it and difficulties in detecting and caring for psychological suffering [6]. The tools for detecting depression are both insufficiently known and inadequately employed. Far too many treatable people suffering from depression slip through the net of evaluation processes and settle into a slow functional decline [27]. Depression often goes undiagnosed in persons who already have probable dementia or behavioral disorders [29], yet detecting depression in these conditions is particularly important because appropriate treatment can reduce suffering, cognitive problems, and behavioral issues [6, 29]. Depression needs to be identified and treated rapidly upon entry into an LTCF so that the new resident can have the chance “to put up a fight” and so as to implement strategies to help them adapt optimally throughout their transition period [31]. Depression does not evolve linearly, and treatments must be adapted to the individual patient's needs [7]. Unfortunately, this is rarely the case [13, 26]. Failure to identify and adequately treat depression is a significant failing in many LTCF. Particular attention should be paid to identifying and planning for professional guidance, support, and specialized care.

Older adults in LTCF require constant, scientifically rigorous monitoring of their health status, especially for depression, and thus healthcare personnel in LTCF require greater knowledge and skills in the field of mental health [13]. Current practices require some rethinking and the development of a more holistic and evidence-based approach to caring for depressed older adults in LTCF.

Recognizing and adequately evaluating a depressive symptomology are indispensable aspects of healthcare monitoring − particularly in an LTCF − for ensuring that older adults receive quality services and that their preferences and needs are met [22]. All healthcare staff, but particularly nurses, need specific education and training on depression and how to recognize and treat it [7].

LTCF exist to help older adults to maintain and possibly reach the best attainable level of overall emotional and mental well-being [32]. This is a part of person-centered care, which should consider each resident's individual needs, rather than symptom-centered care, which can lead to inappropriate overmedication or polymedication [33]. The vast majority of care is aimed at residents' somatic complaints, even though psychiatric disorders, particularly depression, are very widespread [13]. Moreover, because depression can negatively affect the treatment efficacy for numerous other medical disorders, even the most well-intentioned medical interventions can end up being less effective and more expensive [12].

By its very nature, depression is an insidious psychiatric disease and, in long-term care settings, it can become part of a vicious circle. The combination of increased distance and isolation from one's former life together with living in a communal environment, perhaps even sharing a room, can stretch an older adult's resilience and capacity to deal with change. In this context, healthcare professionals must be given the time and ability to understand each resident's emotional and social needs in order to help them maintain their highest possible level of function. Although there are numerous, predictive factors of depression that are a part of the normal ageing process, depression among the residents of LTCF can also be a lead indicator of violence − particularly physical, emotional, and sexual violence [13].

Staff in LTCF should be aware of the prevalence of depression and have a range of appropriate interventions available to them [34]. Maintaining high levels of care can improve the quality of life and alleviate or prevent the symptoms of depression [22]. LTCF that do not make adequate mental health interventions a priority will not attain appropriate standards of care, despite the existence of evidence-based recommendations [7, 35]. Given that levels of depression are regularly underestimated in LTCF, the proper management of depression should include screening and diagnostic procedures (assessments of depression). This rarely happens, however, although structured evaluations of depression using best practice recommendations for appraising its management and consequences do exist [36]. The rigorous identification and treatment of depression would be an excellent place to start.

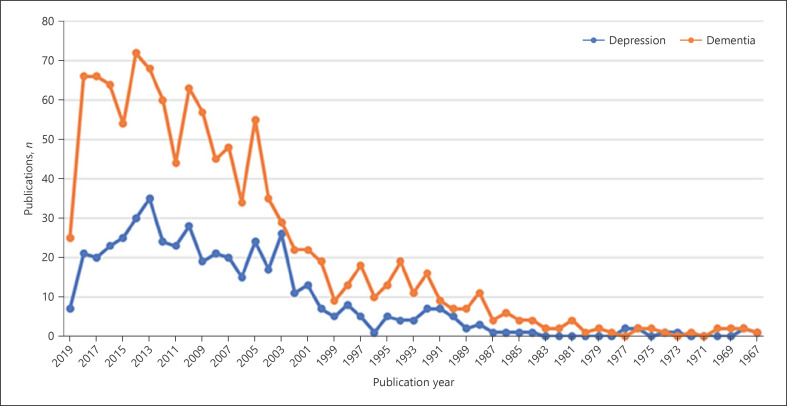

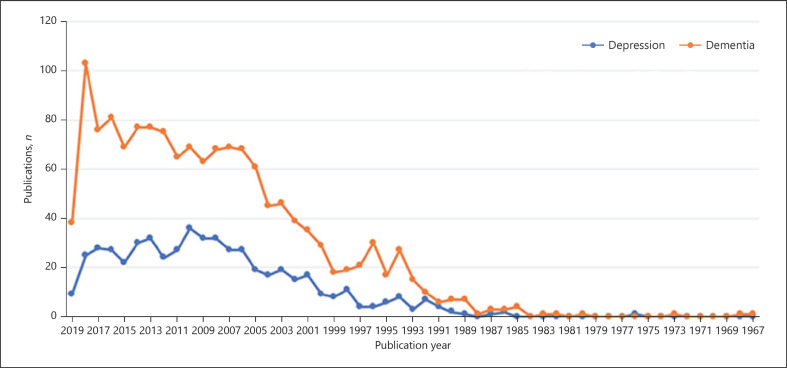

Although the last few decades have seen a lot of research on ensuring the physical well-being of nursing home residents with dementia, there has been comparatively little investigation of depression in LTCF [37]. Figures 1 and 2 present the bibliometric review conducted in Medline. They include the number of published scientific studies involving depression and dementia and studies involving their related health consequences in LTCF.

Fig. 1.

PubMed database publications (since its creation) examining the epidemiology of depression and dementia in LTCF. Note: (PubMed equation (“Depression”[Mesh] OR “Depressive Disorder”[Mesh: NoExp] OR “Depressive Disorder, Treatment-Resistant”[Mesh] OR “Depressive Disorder, Major”[Mesh] OR “Dysthymic Disorder”[Mesh] OR “Seasonal Affective Disorder”[Mesh]) AND (“Residential Facilities”[Mesh]) AND (“Epidemiology”[Mesh] OR “epidemiology”[Subheading]); (“Dementia”[Mesh] NOT “AIDS Dementia Complex”[Mesh]) AND (“Residential Facilities”[Mesh]) AND (“Epidemiology”[Mesh] OR “epidemiology”[Subheading]).

Fig. 2.

PubMed database publications (since its creation) examining the associations between health complications/health status and depression and dementia in LTCF. Note: (PubMed equation (“Depression”[Mesh] OR “Depressive Disorder”[Mesh: NoExp] OR “Depressive Disorder, Treatment-Resistant”[Mesh] OR “Depressive Disorder, Major”[Mesh] OR “Dysthymic Disorder”[Mesh] OR “Seasonal Affective Disorder”[Mesh]) AND (“Residential Facilities”[Mesh]) AND (“Health Status”[Mesh] OR “Health Status Indicators”[Mesh] OR “Health Surveys”[Mesh] OR “Health”[Mesh: NoExp] OR “Mental Health”[Mesh] OR “Physical Fitness”[Mesh: NoExp] OR “Physical Functional Performance”[Mesh: NoExp] OR “Veterans Health”[Mesh] OR “Health Surveys”[Mesh: NoExp] OR “Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System”[Mesh] OR (“Health Status Indicators”[Mesh] NOT “APACHE”[Mesh])); pubmed − (“Dementia”[Mesh] NOT “AIDS Dementia Complex”[Mesh]) AND (“Residential Facilities”[Mesh]) AND (“Health Status”[Mesh] OR “Health Status Indicators”[Mesh] OR “Health Surveys”[Mesh] OR “Health”[Mesh: NoExp] OR “Mental Health”[Mesh] OR “Physical Fitness”[Mesh: NoExp] OR “Physical Functional Performance”[Mesh: NoExp] OR “Veterans Health”[Mesh] OR “Health Surveys”[Mesh: NoExp] OR “Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System”[Mesh] OR (“Health Status Indicators”[Mesh] NOT “APACHE”[Mesh]))).

Conclusion and Recommendations

Our commentary has some limitations. Firstly, the literature and bibliometric reviews were limited to the Medline scientific database. Secondly, our review's nonexhaustive list of descriptors related to the epidemiology of depression and depressive symptoms, which did not extend to pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatments for depression, probably missed some interesting intervention studies. There is an urgent need to better understand depression among institutionalized older adults; new approaches must be developed and their efficacy rigorously evaluated in terms of both improving older adults' quality of life and enhancing cost-efficiency for healthcare and social security systems. More research is needed to better understand the epidemiology of depression, its clinical treatment, and how it moderates and mediates health complications and hospitalizations among older adults in LTCF. There is a demographic imperative requiring the conduction of retrospective, prospective, and interventional clinical research projects that will develop our understanding and increase our knowledge of nursing home residents' health pathways. We will then be able to act effectively and prescribe more appropriate treatments for older adults suffering from depression.

Statement of Ethics

This is a commentary paper including previously conducted research; accordingly, it does not constitute human subject research and does not require an ethics review.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Funding Sources

No funding was received for this study.

Author Contributions

A.M.Q., A.G., M.M., N.I.H.W., and H.V. conceived this article and read and approved the final version. A.M.Q. and H.V. analyzed the data and drafted this paper.

Acknowledgement

The main author expresses her gratitude to the other authors who took part in the writing of this paper.

References

- 1.Office Fédéral de la Statistique . Encyclopédie statistique de la Suisse. OFS; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Organisation de Coopération et de Développement Economiques . Base de données de l'OCDE sur la santé. Paris: OCDE; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO . In: United Nations Demographic Yearbook. WHO, editor. New York: Department of Economic and Social Affairs; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Office Fédéral de la Santé Publique . Vieillir en bonne santé: Aperçu et perspectives pour la Suisse. Berne: OFSP; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kingston A, Wohland P, Wittenberg R, Robinson L, Brayne C, Matthews FE, et al. Cognitive Function and Ageing Studies collaboration Is late-life dependency increasing or not? A comparison of the Cognitive Function and Ageing Studies (CFAS) Lancet. 2017 Oct;390((10103)):1676–84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31575-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chun A, Reinhardt JP, Ramirez M, Ellis JM, Silver S, Burack O, et al. Depression recognition and capacity for self-report among ethnically diverse nursing homes residents: evidence of disparities in screening. J Clin Nurs. 2017 Dec;26((23-24)):4915–26. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thakur M, Blazer DG. Depression in long-term care. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2008 Feb;9((2)):82–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2007.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.WHO . Dépression. Geneva: WHO; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Comijs HC, Nieuwesteeg J, Kok R, van Marwijk HW, van der Mast RC, Naarding P, et al. The two-year course of late-life depression; results from the Netherlands study of depression in older persons. BMC Psychiatry. 2015 Feb;15((1)):20. doi: 10.1186/s12888-015-0401-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diebold M, Widmer M. Indicateurs de santé des personnes âgées en Suisse. Neuchatel: OFS; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Höglinger M, Seiler S, Ehrler F, Maurer J. Gesundheit der älteren Bevölkerung in der Schweiz. In: Schweiz S, editor. Lausanne et Winterthour: ZHAW-WIG, FORS. UNIL; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghanmi L, Sghaier S, Toumi R, Zitoun K, Zouari L, Maalej M. Depression in the elderly with chronic medical illness. Eur Psychiatry. 2017 Apr;41(S1):S651–51. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Juman R, Figlerski R. Depression in Nursing Homes. Today's Geriatric Medicine. 2019;10:34. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosenberg PB, Mielke MM, Samus QM, Rosenblatt A, Baker A, Brandt J, et al. Transition to nursing home from assisted living is not associated with dementia or dementia-related problem behaviors. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2006 Feb;7((2)):73–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hughes JC. Dependence and autonomy in old age: an ethical framework for long term care. J Med Ethics. 2005;31((1)):e3–3. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wulff I, Kölzsch M, Kalinowski S, Kopke K, Fischer T, Kreutz R, et al. Perceived enactment of autonomy of nursing home residents: A German cross-sectional study. Nurs Health Sci. 2012;10:15. doi: 10.1111/nhs.12016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dencker K, Gottfries CG. Activities of daily living ratings of elderly people using Katz' ADL Index and the GBS-M scale. Scand J Caring Sci. 1995;9((1)):35–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.1995.tb00263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Graf C. The Lawton instrumental activities of daily living scale. Am J Nurs. 2008 Apr;108((4)):52–62. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000314810.46029.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tabali M, Ostermann T, Jeschke E, Dassen T, Heinze C. Does the care dependency of nursing home residents influence their health-related quality of life?-A cross-sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013 Mar;11((1)):41. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-11-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anstey KJ, von Sanden C, Sargent-Cox K, Luszcz MA. Prevalence and risk factors for depression in a longitudinal, population-based study including individuals in the community and residential care. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007 Jun;15((6)):497–505. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31802e21d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Samus QM, Mayer L, Onyike CU, Brandt J, Baker A, McNabney M, et al. Correlates of functional dependence among recently admitted assisted living residents with and without dementia. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2009 Jun;10((5)):323–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crogan NL, Evans BC. Quality Improvement in Nursing Homes: Identifying Depressed Residents is Critical to Improving Quality of Life. Ariz Geriatr Soc J. 2008 May;13((1)):15–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smoliner C, Norman K, Wagner KH, Hartig W, Lochs H, Pirlich M. Malnutrition and depression in the institutionalised elderly. Br J Nutr. 2009 Dec;102((11)):1663–7. doi: 10.1017/S0007114509990900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Byers AL, Sheeran T, Mlodzianowski AE, Meyers BS, Nassisi P, Bruce ML. Depression and risk for adverse falls in older home health care patients. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2008 Oct;1((4)):245–51. doi: 10.3928/19404921-20081001-03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leontjevas R, Teerenstra S, Smalbrugge M, Vernooij-Dassen MJ, Bohlmeijer ET, Gerritsen DL, et al. More insight into the concept of apathy: a multidisciplinary depression management program has different effects on depressive symptoms and apathy in nursing homes. Int Psychogeriatr. 2013 Dec;25((12)):1941–52. doi: 10.1017/S1041610213001440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morley JE. Depression in nursing home residents. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2010 Jun;11((5)):301–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2010.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iden KR, Engedal K, Hjorleifsson S, Ruths S. Prevalence of depression among recently admitted long-term care patients in Norwegian nursing homes: associations with diagnostic workup and use of antidepressants. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2014;37((3-4)):154–62. doi: 10.1159/000355427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ell K. Depression care for the elderly: reducing barriers to evidence-based practice. Home Health Care Serv Q. 2006;25((1-2)):115–48. doi: 10.1300/J027v25n01_07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Volicer L, Van der Steen JT, Frijters DH. Modifiable factors related to abusive behaviors in nursing home residents with dementia. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2009 Nov;10((9)):617–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nelluri S, Rodriguez-Suarez MM, Rahaman Z, Cabrera K, Priyadarshni S, Pamarthi M, et al. Coexisting Frailty and Depression in Older Veterans: Effects on Health Care Utilization. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;26((3)):S138–9. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kramer D, Allgaier AK, Fejtkova S, Mergl R, Hegerl U. Depression in nursing homes: prevalence, recognition, and treatment. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2009;39((4)):345–58. doi: 10.2190/PM.39.4.a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levin CA, Wei W, Akincigil A, Lucas JA, Bilder S, Crystal S. Prevalence and treatment of diagnosed depression among elderly nursing home residents in Ohio. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2007 Nov;8((9)):585–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boorsma M, Joling K, Dussel M, Ribbe M, Frijters D, van Marwijk HW, et al. The incidence of depression and its risk factors in Dutch nursing homes and residential care homes. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012 Nov;20((11)):932–42. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31825d08ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leontjevas R, Gerritsen DL, Smalbrugge M, Teerenstra S, Vernooij-Dassen MJFJ, Koopmans RTCM. A structural multidisciplinary approach to depression management in nursing- home residents: a multicentre, steppedwedge cluster-randomised trial. Lancet. 2013 Jun;381((9885)):2255–64. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60590-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wagenaar D, Colenda C, Kreft M, Sawade J, Gardiner J, Poverejan E. Treating depression in nursing homes: practice guidelines in the real world. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2003 11/01;103:465–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Simning A, Simons KV. Treatment of depression in nursing home residents without significant cognitive impairment: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2017 Feb;29((2)):209–26. doi: 10.1017/S1041610216001733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O'Neill M, Ryan A, Slater P, Ferry F, Bunting B. Mental Health, Quality of Life and Medication Use Among Care Home Residents and Community Dwelling Older People. Int J Res Nurs. 2019;10:10–23. [Google Scholar]