Abstract

Grape seed procyanidin extract (GSE) had been reported to exert antineoplastic properties in preclinical studies. A modified phase I, open-label, dose-escalation clinical study was conducted to evaluate the safety, tolerability, maximum tolerated dose (MTD), and potential chemopreventive effects of leucoselect phytosome (LP), a standardized GSE complexed with soy phospholipids to enhance bio-availability, in heavy active and former smokers. Eight subjects age 46 – 68 were enrolled into the study and treated with escalating oral doses of LP for 3 months. Bronchoscopies with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) and bronchial biopsies were performed before and after 3 months of LP treatment. H&E stain for histopathology grading and immunohistochemical examination for Ki-67 proliferative labeling index (KI-67 LI) were carried out on serially matched bronchial biopsy samples from each subject to determine responses to treatment. Two subjects were withdrawn due to issues unrelated to the study medication, and a total of 6 subjects completed the full study course. In general, three months of LP, reaching the highest dose per study protocol was well tolerated and no dosing adjustment was necessary. Such a treatment regimen significantly decreased bronchial Ki-67 LI by an average of 55% (p = 0.041), with concomitant decreases in serum microRNA (miR) -19a, -19b and -106b, which were oncomirs previously reported to be downregulated by GSE, including LP, in pre-clinical studies. In spite of not reaching the original enrollment goal of 20, our findings nonetheless support the continued clinical translation of GSE as an anti-neoplastic and chemopreventive agent against lung cancer.

Keywords: leucoselect phytosome, bronchial Ki-67, serum miRNA, oncomir, eicosanoids

INTRODUCTION

Grape seed procyanidin extract (GSE) have been used as a health food supplement for decades to promote cardiovascular health, such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, atherosclerosis, and chronic venous insufficiency (1). In a randomized control study (GSE group n = 146 and control group n = 141), GSE treatment inhibited the progression of mean maximum carotid intima-media thickness, reduced carotid plaque size and lower rates of clinical vascular events (2). Another small, randomized double-blind placebo-controlled crossover study involving 22 mildly hyperlipidemic individuals showed significant reduction of total cholesterol, low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and oxidized low-density lipoprotein particles (Ox-LDL) (3). GSE has antioxidant capabilities significantly higher than that of vitamin C and E (4). Preclinical studies have demonstrated a variety of antineoplastic effects of GSE against lung cancer (5–9), providing us the impetus to translate the findings into clinical trials. It is well known that the absorption of GSE appears to be affected by molecular wt. and the variable compositions of GSE polyphenols in various commercial products further contribute to low and erratic bioavailability (10, 11). An inexpensive GSE preparation (leucoselect), standardized to smaller size oligomeric procyanidins (OPC) that has been complexed with soy phospholipids into phytosomes to improve bioavailability, is available over the counter. This Leucoselect phytosome (LP) has been shown to improve oxidative status in several clinical trials, including the total antioxidant capacity of plasma, and reduce LDL susceptibility to oxidative stress in heavy smokers (12). As such, it has been selected for our preclinical studies, which demonstrated antineoplastic efficacy against human lung cancer xenografts growth on nude mice in vivo. Our encouraging preclinical findings (7–9) set the stage for this modified phase I lung cancer chemoprevention trial with LP.

As a part of a pilot, modified phase I study to evaluate the feasibility of LP as a chemopreventive agent for lung cancer, heavy current and former smokers were recruited and treated with a 3-months course of oral LP, to determine the safety, tolerability and optimal dose. To determine the effects of LP on altering various surrogate endpoint biomarker (SEBM) of carcinogenesis in the lung, serial bronchoscopies with bronchoalveolar lavages (BAL) and bronchial biopsies were performed. According to the field cancerization concept, key molecular and biochemical events are thought to occur before altered cellular morphology is apparent. In fact, data suggests that histologic response to chemoprevention may not be sufficient in determining their efficacy (13). In addition to modulation of histopathology, many chemopreventive trials have used various markers known to be causally linked to lung cancer as SEBM, including the assessment of cell proliferation with Ki-67. Ki-67 is a proliferation marker expressed in all phases of the cell cycle except in resting cells (14). Because abnormal epithelial proliferation is a hallmark of tumorigenesis, the measurement of Ki-67 labeling indices (Ki-67 LI) in bronchial tissues as a SEBM for lung cancer chemoprevention trials has attracted interests. Elevated bronchial Ki-67 levels can be detected in areas where squamous metaplasia is lacking (13). As such, high Ki-67 LI may also be a useful marker for lung cancer risk. Indeed, elevated Ki-67 LI has been reported to be an unfavorable prognostic factor in non–small cell lung cancers (15), and has been used as the primary endpoint in successful phase II lung cancer chemoprevention trials (16–18).

In the present report, we evaluated the safety, tolerability, and the effect of oral LP on modulating bronchial Ki-67 LI and histopathology in bronchial biopsies, as well as modulations of serum oncomirs miR-19a, -19b, and -106b (these 3 miRNAs were pre-specified secondary endpoints based on our preclinical studies). Our findings support the hypothesis that oral administration of LP can reach the target organ of interest and modulate Ki-67 LI in the bronchial tissues of heavy current and former smokers. We further demonstrate that LP treatment significantly down-regulates blood oncomirs miR-19a, -19b and -106b in the subjects, consistent with our preclinical findings in mouse xenograft models.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Leucoselect Phytosome Clinical Study Design.

A single arm, dose escalation, modified phase I lung cancer chemoprevention study of 3 months of oral LP, comprised of standardized oligomeric procyanidins complexed with soy phospholipid (1:2.6 w/w; Indena, Milan, Italy), was conducted in high risk heavy active or ex-smokers 21 years of age or older with a smoking history of at least 30 pack-years (pky). The primary endpoint was safety and tolerability. Written informed consent was obtained in accordance with the New Mexico VA Health Care System (NMVAHCS) Institutional Review Board (IRB). Participants were screened with history and physical examination (H&P), spirometry, Chest X-ray, 12-lead EKG, routine blood tests [complete blood count (CBC); Chemistry panel; Prothrombin time (PT), partial thromboplastin (PTT); lipid panel: total cholesterol, high density lipoprotein (HDL), low density lipoprotein (LDL), and triglyceride], serum cotinine, standardized respiratory/general health questionnaires that detailed subjects’ demographic information, smoking behavior, occupation, and medical conditions; chest X-ray, fluorescence bronchoscopy with BAL and bronchial biopsies to rule out the presence of lung cancer and for collections of samples at baseline. Qualified participants meeting all entry criteria (Table 1A) were enrolled and treated with 1 capsule (cap), 450 mg/cap/day for week one, 2 caps/day for week 2, 3 caps/day for week 3, then 4 cap/day for the rest of the treatment duration as tolerated. Repeat fluorescence bronchoscopy was performed at the end of 3 months treatment when samples were collected for comparative biomarker analysis. All subjects were assessed with a phone visit at the end of week 3 after receiving 3 caps/day for a week to ensure safety and tolerability, before escalating to the final dose of 4 caps/day, followed by in person clinic visits at the end of week 4/month 1, then at the end of month 2 and month 3, with H & P, routine blood tests, serum cotinine, and a final 1 month post-treatment phone follow up at the end of month 4. The safety and side effects of oral LP were monitored at each visit using the modified NCI common toxicity criteria scale and adverse reaction questionnaires.

Table 1A.

Study entry criteria

| Inclusion: |

| • Age over 21. |

| • Smoking history > 30 pack years. |

| Exclusion: |

| • Inability to provide informed consent (e.g. cognitive impairment, severe psychiatric disorders). |

| • Hypersensitivity to grapes and related products. |

| • Liver dysfunction (abnormal liver function tests). |

| • Renal dysfunction (abnormal serum creatinine). |

| • End stage respiratory disease (FEV1<0.8 liters, resting or exertional hypoxemia, to select patients with adequate reserve to undergo bronchoscopy and complete the study). |

| • Unstable angina. |

| • Malignancy within 5 years, excluding non-melanoma type skin cancer or stage I NSCLC post curative resection without evidence of recurrence. |

| • Pregnancy. |

| • Systemic corticoid steroid therapy. |

| • Coagulopathy. |

| • Concurrent use of grapes or grape related products. |

| • Unwilling to refrain from drinking more than 1 glass of wine a day. |

| • Patients with concurrent medical conditions that may interfere with completion of tests, therapy, or the follow up schedule. |

Bronchoscopy, BAL, and bronchial biopsy.

Bronchoscopies were performed as previously described (Onco-Life, Novadaq Technologies, Inc. Ontario, Canada) (16, 18). Briefly, subjects were prepped with a combination of topical anesthesia (4% lidocaine atomized to posterior pharynx plus 1-2% aliquots of topical lidocaine along the laryngo-tracheo-bronchial tree as needed), and moderate sedation using incremental doses of midazolam and fentanyl according to institutional guidelines. A fiberoptic bronchoscope (BF 20D, Olympus America) was advanced transorally under direct visualization and the airways were inspected systematically first with white light followed by autofluorescence examination. BAL was performed by wedging the bronchoscopy into the subsegment of the right middle lobe, followed by inistallions of four 60-ml aliquots of room temperature saline serially and recovered by manual syringe suction. Recovered fluid was passed through a 100-micron sterile nylon filter (Becton Dickinson) to remove mucus and particulates, pooled, and centrifuged at 300 × g for 8 minutes at 4°C. The BAL fluid was then harvested, aliquoted and stored at −80°C until analyzed as previously described (18). Bronchial biopsies were obtained from predetermined sites (main carina, carina between right upper lobe and bronchus intermedius, right middle lobe and right lower lobe, right lower lobe anterior and medial basal segment, lingua and upper division bronchus, left upper lobe and left lower lobe), as well as additional sites that appeared abnormal. Bronchial biopsies were first fixed in formalin fixative, processed routinely, then embedded in paraffin.

Histopathology grading.

Four-micrometer serial sections were obtained from each biopsy specimen and processed for routine Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain examination. All biopsies were classified and scored by an investigator (L. M.) without knowledge of the treatment time point, according to the WHO criteria (1, normal; 2, reserve cell hyperplasia; 3, squamous metaplasia; 4, mild dysplasia; 5, moderate metaplasia; 6, severe metaplasia; 7, carcinoma in situ). When more than one histologic grade was present in a biopsy, the scoring was made based on the most advanced histology present.

Expression of Ki-67on bronchial biopsies.

All bronchial epithelial cells present in the biopsy samples were evaluated at high-magnification. Ki-67 was recorded as the percentage of bronchial cells that showed nuclear staining in the parabasal layer. Up to five high-magnification fields were examined until 400 bronchial epithelial cells were counted. Using the DAKO Envision Flex system and Autostainer (Aligent, Santa Clara, CA), the slides were processed per manufacturer’s instructions and incubated serially with the primary Ki-67 antibody (1:50 dilution; DAKO Corp., Carpenteria, CA) for 30 minutes, followed by a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled polymer conjugated with a secondary antibody for 30 minutes at room temperature and 5 minutes in Diaminobenzidine as the chromogen for the immunoperoxidase reaction. A semiquantitative method was used to evaluate the intensity and frequency of immunostaining. A scoring system of 0, 1, 2, and 3 (0 being below the level of detection and 3 being intense staining) was used. For each tissue section, the percentage of bronchial epithelial cells staining at each intensity was determined, followed by generation of a composite score for that section. For immunohistochemical (IHC) staining, batch processing and analyses were carried out on paired sections from matched biopsies obtained pre- and post-treatment from each subject to eliminate interassay variability. Negative controls using nonimmune sera showed no staining.

Measurements of serum MiR-19a, -19b, and -106b.

Total RNA in matched pre- and post-treatment serum from baseline and Month 3 were isolated using the miRNA easy kit and spiked with a synthetic Syn-cel-mir-39 miRNA mimic. The RNA was then converted into cDNA, and miR-specific quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) were performed using specific primers from SA Bioscience per manufacturer’s instruction (Qiagen Inc.) as previously described (9). Any raw threshold cycle (Ct) greater than 35 was considered a negative call. The values were first normalized to Syn-cel-mir-39, then to control, using ΔΔCt based fold-change calculations from raw Ct data. Data were depicted in fold changes normalized to control. Negative fold change represented down-regulation; a reduction of 50% or 75% from control (baseline) was equivalent to −2 or −3 fold changes, respectively.

Outcomes.

The primary endpoint of the study was safety and tolerability of the LP study dosing regimen. Secondary endpoints included modulation of Ki-67 LI and histopathology grading in bronchial biopsies, and modulations of blood miR-19a, -19b, and -106b by LP.

Statistical Analysis.

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize participant characteristics. The effects of 3 months of LP treatment on Ki-67 LI and histopathology grading of bronchial biopsies, serum miR-19a, -19b, and -106b levels were determined by comparing baseline values with those obtained at 3 months of treatment using paired t tests and/or ANOVA. Batch analyses were performed for each comparison group to eliminate interassay variability. Data were expressed as the mean ± SEM in all circumstances where mean values were compared. Differences were considered significant when p <0.05.

RESULTS

Subject characteristics, treatment course and adverse events.

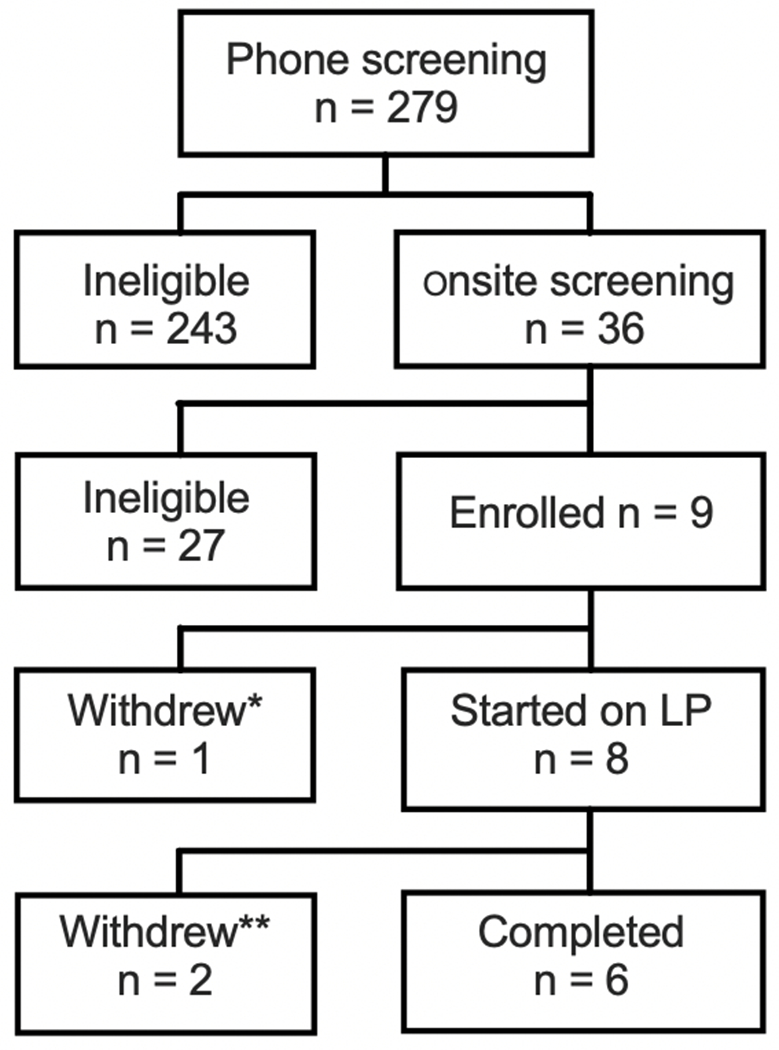

We performed phone screening on 279 subjects, invited and consented 36 subjects for onsite screening. Nine of the 36 subjects passed all screening, including bronchoscopy and were officially enrolled to receive study intervention/medication. However, one subject withdrew from the study prior to initiation of study medication due to relocation to another state (Figure 1). Eight subjects, consisted of 5 males and 3 females with a mean age of 58.6, all Caucasian (Table 1B), were treated with study medication. Two of these subjects had evidence of airflow obstruction defined as forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) < 80% predicted with FEV1/ forced vital capacity (FVC) < 0.70. Two subjects had at least one family member with a history of lung cancer.

Fig. 1.

Consort flow diagram of subject accrual into the trial. * The patient withdrew prior to starting on study medication due to relocation to another state. ** withdrew by MD due to adverse event deemed not related to study medication.

Table 1B.

Baseline subject characteristics

| Variables | Mean (range) | n |

|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 58.6 (46 - 68) | |

| Smoking history (pack years)* | 40.4 (30 - 55) | |

| Gender (M/F) | 5/3 | |

| Ethnicity (Caucasian) | 8 | |

| COPD (n) | 2 | |

| Family history of lung cancer (n) | 2 |

three subjects were active smokers

Two of the subjects were withdrawn from the study by the principle investigator (PI) during the treatment phase, one due to vasovagal reaction during blood draw (this subject had a history of such events with blood draws), the other due to significant epistaxis (this subject had a past history of such significant, recurrent epistaxis requiring cauterization, and a family history of telangiectasia that he did not disclose during screening visit). In the end, a total of 6 subjects completed the entire 3 months treatment course and 1 month post-treatment follow up of the study (Fig. 1). One of the 6 subjects had an isolated, mild (grade 1) increase in SGOT at the month 3 visit (last scheduled blood draw; there was a substantial delay in processing the blood chemistry sample due to labeling issues, which could have affected the result). By the time the abnormality was acknowledged (within a week), repeat SGOT was within normal limits. The smoking status of the subjects did not change during study participation as confirmed by serum cotinine.

In general, LP was well tolerated at the maximum dose of 4 caps/day, no dose adjustment had been necessary. Interestingly, one subject reported that her hair and nails seemed to be growing faster and stronger, another reported subjectively better circulations in the hands. No significant changes were observed in blood pressure, heart rate nor lipid panels.

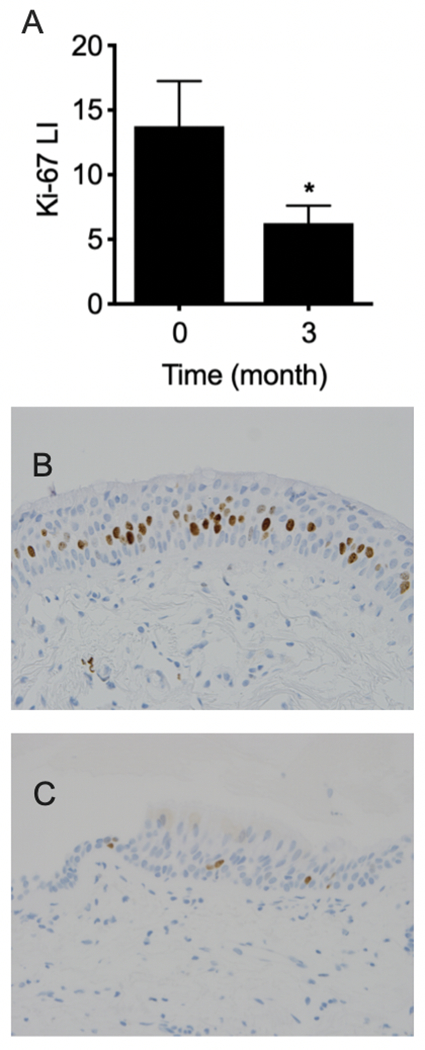

Effects of 3 months of oral LP treatment on bronchial Ki-67 LI.

To determine the effects of oral LP on epithelial cell proliferation, Ki-67 expression at matched biopsy sites were compared before and after treatment. A total of 48 paired biopsies were available for evaluation. On average, 3 months of LP decreased Ki-67 LI by 55% (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Ki-67 expression at matched biopsy sites were compared before and after 3 months of oral LP treatment. A total of 48 paired biopsies were available for evaluation. A) On average, 3 months of LP decreased Ki-67 LI by 55% (13.8 ± 3.50 at baseline versus 6.25 ± 1.36 at 3 months). Columns, mean; bars, SEM. *, P < 0.041. Representative photomicrographs of matched bronchial Ki-67 IHC staining B) before treatment, C) after 3 months of oral LP; magnification: 400×.

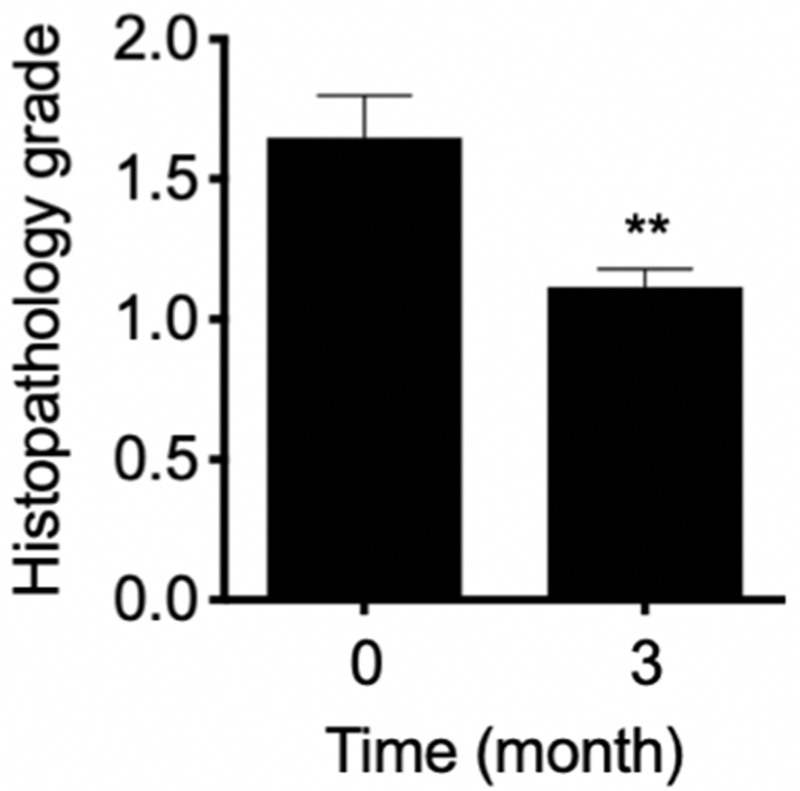

Effects of 3 months of oral LP treatment on bronchial histopathology grading.

To determine the effect of LP treatment on bronchial histopathology, histopathology grading scores of matched bronchial biopsies were assessed and compared pre- and post-treatment. At baseline, of the 48 paired bronchial biopsies, only 4 biopsies showed squamous metaplasia (grade 3, highest grade), 9 biopsies showed reserve hyperplasia (grade 2), and 11 biopsies were normal (grade 1). At 3 months, only 3 biopsies showed grade 2 changes, the rest were grade 1 (Fig. 3). Although statistically LP treatment significantly reduced bronchial histopathology grading, the clinical significance of such a modulation was unclear.

Fig. 3.

Histopathology grading scores from pre- and post-treatment bronchial biopsies were compared. At baseline, of the 48 paired bronchial biopsies, only 4 biopsies showed squamous metaplasia (grade 3, highest grade), 9 biopsies showed reserve hyperplasia (grade 2), and 11 biopsies were normal (grade 1). At 3 months, only 3 biopsies showed grade 2 changes, the rest were grade 1. On average, 3 months of LP decreased histopathology grade by 32% (1.630 ± 0.143 at baseline vs. 1.115 ± 0.064 at 3 months). Columns, mean; bars, SEM. **, P < 0.002.

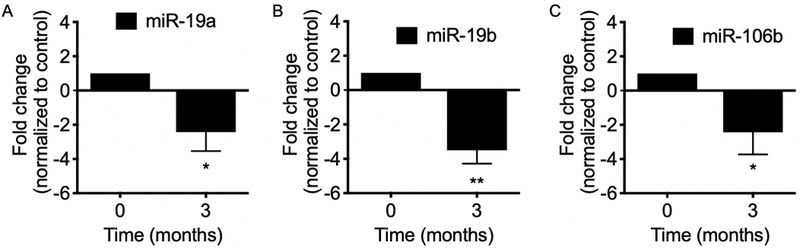

Three months of oral LP treatment downregulated serum oncomirs miR-19a, -19b, and -106b.

To determine the effects of oral LP on these oncomirs in the blood, total RNA was isolated from serum. MiR-specific qPCR were performed on matched pre- and post - LP treatment serum samples. Three months of LP treatment significantly downregulated the expressions of miR-19a, miR-19b and miR-106b in serum (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Total RNA was isolated from serum before and after 3 months LP treatment. MiR-19a, -19b, and -106b specific qPCR were performed on matched pre- and post - LP treatment serum samples. Three months of LP treatment significantly downregulated the expressions of miR-19a, miR-19b and miR-106b in serum. Mean; bars, SEM (n = 6). *, P < 0.05. **, P < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

In this modified phase 1 pilot study with LP, we demonstrate, for the first time, the safety, tolerability, and the dose of a standardized GSE that corresponded to favorable modulations of SEBM for lung cancer chemoprevention, including bronchial Ki-67 LI, and serum oncomirs miR-19a, -19b, and -106b.

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death in the world, accounting for an estimated 2.09 million deaths in 2018 (19). Despite significant advancements in anti-cancer treatments, the 5-year survival rate for lung cancer remains dismal. The lack of effective therapy provides the impetus to search for alternative, safe and efficacious agents for lung cancer chemoprevention, to impede the driving forces of cancerization, and prevent the development of lung cancer in at-risk individuals (20). Whereas chemopreventive approaches have been proven successful for various cancers such as breast and colon cancer (21, 22), successes in phase III lung cancer chemoprevention trials have remained elusive.

Most phase I and II lung cancer chemoprevention studies used preneoplastic bronchial histopathology as primary end points; without a doubt persistent bronchial dysplasias are the best characterized precancerous lesions and validated risk markers for invasive squamous cell carcinoma (23). However, with the shift of the most prevalent lung cancer cell type from squamous cell carcinoma to adenocarcinoma, the utility of bronchial histopathology as primary SEBM for lung cancer chemoprevention studies has been increasingly challenged. Squamous cell carcinoma mostly arises from the bronchial epithelium in the central airway and evolves from bronchial preneoplasia via the multi-step carcinogenesis processes, whereas adenocarcinoma mostly arises peripherally with alveolar adenomatous hyperplasia as the precursor lesion (24, 25). Another concern regarding the use of bronchial histopathology is the potential mechanical removal of preneoplastic lesions on baseline bronchoscopies, thereby falsely increasing the response rate. Bronchial Ki-67, a marker of cell proliferation, while subject to the same mechanical issue from biopsy, may partially bypass this epiphenomenon, as the time required for reemergence of such a molecular marker in a procarcinogenic microenvironment should be much shorter then histopathology. To this end, we and others have used bronchial Ki-67 LI as the primary endpoint for phase IIb lung cancer chemoprevention trials (17, 18). Moreover, in a phase IIb lung cancer chemoprevention trial with celecoxib in heavy ex-smokers, reduction of bronchial Ki-67 LI have appeared to correlate with resolution of lung nodules in response to treatment (18). As such, the utility of bronchial Ki-67 as a SEBM to detect favorable treatment responses in lung cancer chemoprevention studies may extend beyond the central airways to include peripheral lesions, thereby reflecting favorable modulations of the entire lung microenvironment (18). Although true validation of bronchial Ki-67 as a SEBM can only be achieved in larger, randomized control trials with sufficient sample sizes and longitudinal follow up.

It is noteworthy that even with the potential advantage of using bronchial Ki-67 Li as a SEBM, there are major challenges associated with the use of bronchoscopy for monitoring the effects of lung cancer chemoprevention in clinical trials, including 1) the invasive nature of the bronchoscopy procedure, 2) the peri-procedural time investment required from the participants, and 3) the requirement of having a family member or trusted individual to transport the participant pre- and post-procedure, leading to difficulties in recruitment. Therefore, it may be more practical to design future larger scale, randomized phase IIb lung cancer chemoprevention studies with LP using lung nodules detected on CT scans as the primary endpoint, especially in view of the fact that adenocarcinoma is now the most prevalent lung cancer cell type. Acknowledging the less definitive nature of lung nodules, the specificity of such a SEBM may be enhanced by combining with correlative serum oncomirs MIR-19a, -19b, and -106b levels.

Aberrant expressions of miRNA have been implicated as drivers of tumorigenesis/promotion, including classical cancer pathways such as increases in cell proliferation, angiogenesis and resistance to apoptosis. MiR-19a, -19b and -106b are among the oncomirs that have been reported to play a role in tumors of many organs including lung (26–28). Previously in preclinical studies, we reported the effects of GSE on down-regulating well-known oncomirs miR-19a, -19b, and -106b (7, 9), which correlated with inhibition of human lung tumor xenograft growth by LP in athymic nude mice in vivo. Reductions of these oncomirs also correlated with decreased cell proliferation and induction of apoptosis. Decreases in MiR-19a and -19b up-regulated insulin-like growth factor II receptor (IGF2R), phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) mRNA expressions, and their respective protein products. Furthermore, GSE increased PTEN activity and decreased phosphorylation of AKT – a key procarcinogenic driver in lung cancer. Both PTEN and IGF2R are tumor suppressors and predicted targets of miR-19a and -19b (TargetScanHuman, http://www.targetscan.org/vert_61). In addition, we demonstrated that down-regulation of miR-106b resulting in up-regulation of its downstream target, the tumor suppressor cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A (CDKN1A) mRNA and protein (p21) levels, further contributed to the antineoplastic effects of GSE. Our findings from this phase 1 study with LP are consistent with those from the preclinical studies.

The encouraging findings from prior phase IIb lung cancer chemoprevention trials with the cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitor, celecoxib (17, 18), and a synthetic analogue of prostacyclin (PGI2), iloprost (29), engendered discussions on developing a study using a combination of the two agents, so that iloprost might negate the increased cardiovascular risk associated with pharmaceutical COX-2 inhibitors, while exerting synergistic anti-neoplastic effects. In the end, various issues associated with both agents prevented further investigation in phase III trials.

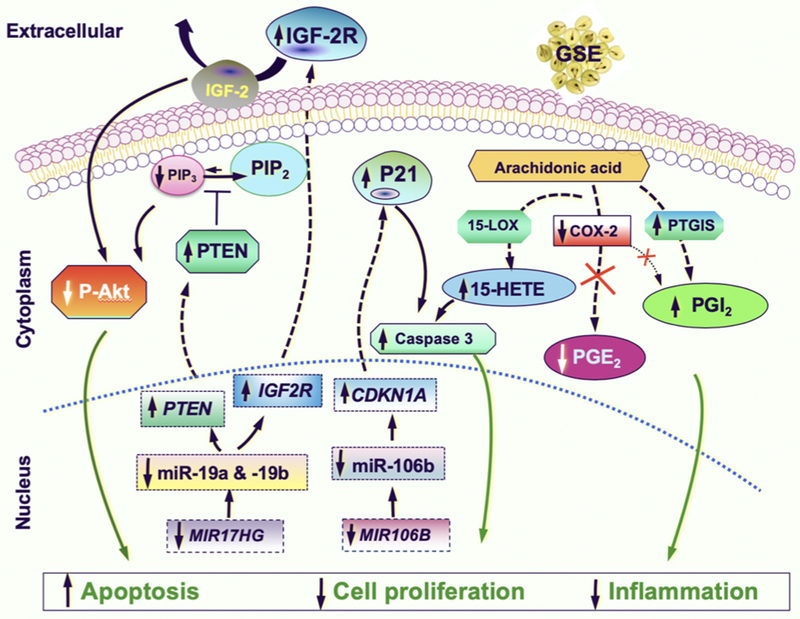

Whereas the molecular mechanisms underlying the cardiovascular benefits of GSE are incompletely understood, on the basis that GSE has been reported to inhibit the proinflammatory and procarcinogenic COX-2/PGE2 pathways, yet widely used to promote cardiovascular health, we hypothesize that GSE may simultaneously increase PGI2, thereby functioning both as a natural COX-2 inhibitor and PGI2 inducer. Furthermore, inhibition of COX-2 may lead to shunting of arachidonic acid precursors toward the 15-lipoxygenase (15-LOX) and 15-Hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (15-HETE) pathways. Such assertions are supported by findings from our recent report, demonstrating that ex vivo treatment of baseline BAL cells from subjects participating in this trial with GSE significantly increases the production of PGI2 and 15-HETE, and co-culture with these GSE-treated BAL cell culture supernatants decreases lung premalignant and malignant cell proliferations. Moreover, co-culturing with post-LP treatment BAL fluid significantly reduces proliferation of lung premalignant and malignant cells in comparison with matched, pre-treatment BAL fluid from the same subjects in this phase 1 trial with LP (8). BAL is a relatively non-invasive accessory bronchoscopic procedure that allows sampling of the peripheral lung microenvironment, where the cellular/molecular biology is quite distinct from the proximal airways. Because conventional endobronchial biopsies can only sample the central airways, BAL adds another dimension to the analysis of treatment effects. The ability for post-treatment BAL fluids to significantly inhibit growth of lung cancer cell lines (8), combined with the significant reduction of Ki-67 LI in the proximal bronchi, further supports the notion that systemic administration of LP is capable of dampening the driving forces of cancerizations in the entire lung fields. Figure 5 summarizes these molecular mechanisms involved in mediating the multi-faceted, anti-neoplastic effects of GSE against lung cancer.

Fig. 5.

Proposed mechanistic diagram of the multi-faceted, anti-neoplastic effects of GSE against lung cancer. Through downregulating oncomirs miR19-a, -19b, -106b and modulating their respective downstream targets (increases in tumor suppressors PTEN, IGF2R and decrease in activated p-Akt by miR-19a/b; increase in the tumor suppressor P21 by miR-106b), as well as modulating major eicosanoids signaling pathways (decreases in PGE2 and PGI2 due to COX-2 inhibition, while an increase in PTGIS results in an overall increase in PGI2, and an increase in 15-HETE likely due to shunting of the arachidonic acid precursor toward the 15-LOX pathway in the setting of COX-2 inhibition), GSE increases apoptosis, decreases cell proliferation, decreases inflammation, thereby reduces the driving forces of cancerization.

Our study design deviates from the conventional phase I escalation schema, in which subjects are recruited into different, escalating dose cohorts (typically 3 + 3 rule method). As the primary objective of a phase I study is to define the recommended phase II dose, various innovative phase 1 trial designs beyond the conventional design have been proposed, guided by the principle of slow escalation in the face of toxicity and rapid dose increases in the setting of minimal or no adverse events. In other words, when the toxicity of a drug is uncertain, and a narrow therapeutic window is suggested by preclinical testing, then a conservative 3 + 3 method should be used. If, however, the therapeutic window of the agent is wide, and the expected toxicity is low, then rapid escalation with a novel rule- or model-based design should be used (30). Therefore, we selected the study design based on our preclinical data and the general experiences from over the counter use of LP (typically 1-2 capsules a day). All subjects were assessed with a phone visit at the end of week 3 after receiving 3 capsules a day for a week to ensure safety and tolerability prior to the final escalation to 4 capsules a day. This study schema is different from a phase IIa study in which the dose regimen is reasonably defined in terms of safety/tolerability, and the dose escalation over time is solely used to build up tolerance to the drug. Our modified phase I study design aims to use a single cohort with relatively rapid intrasubject dose escalations to efficiently define the MTD, and in the event MTD is not reached, significant modulations of SEBM of sufficient functional significance, including bronchial Ki-67 LI, can be used to define the recommended phase II dose. Such a design also helps minimize the chance of participants being treated at subtherapeutic doses and maximize the sample sizes for secondary, efficacy endpoint analysis to identify the recommended phase II dose.

In summary, findings from our modified phase I feasibility study define the appropriate dosing of LP for phase II studies, and support our hypothesis that GSE-mediated anti-neoplastic mechanisms involve modulations of oncomirs miR-19a, -19b, and 106b, in addition to modulations of major eicosanoid signaling pathways previously reported (8). Further explorations of the potential utility of a natural COX-2 inhibitor with favorable side effect profiles that may also be cardio-protective, such as LP, for treatment and prevention of lung cancer is clearly justified. Despite not reaching the recruitment goal of 20, interim and final analysis still indicated significant modulations of SEBM. As such, our findings support further clinical investigations of LP as an anti-neoplastic and chemopreventive agent against lung cancer.

Acknowledgement

We wish to thank A. Vargas, K. Park, and E. Martinez for their excellent technical assistance; Indena, Inc. and Thorne research, Inc., for generously supplying the LP. This work has been supported by grants from National Cancer Institute (R21CA173211 to J. T. Mao), and VA Merit Review (BX002258, and BX004092 to J. T. Mao).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interests: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. Grape Seed extract. https://nccih.nih.gov/health/grapeseed/ataglance.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cao AH, Wang J, Gao HQ, Zhang P, Qiu J. Beneficial clinical effects of grape seed proanthocyanidin extract on the progression of carotid atherosclerotic plaques. J Geriatr Cardiol 2015;12(4):417–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Razavi SM, Gholamin S, Eskandari A, Mohsenian N, Ghorbanihaghjo A, Delazar A, Rashtchizadeh N, Keshtkar-Jahromi M, Argani H. Red grape seed extract improves lipid profiles and decreases oxidized low-density lipoprotein in patients with mild hyperlipidemia. J Med Food 2013;16(3):255–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bagchi D, Bagchi M, Stohs SJ, Das DK, Ray SD, Kuszynski CA, Joshi SS, Pruess HG. Free radicals and grape seed proanthocyanidin extract: importance in human health and disease prevention. Toxicology 2000;148(2-3):187–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharma S, Meeran S, Katiyar S. Proanthocyanidins inhibit in vitro and in vivo growth of human non-small cell lung cancer cells by inhibiting the prostaglandin E (2) and prostaglandin E (2) receptors. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics 2010; 9:569–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akhtar S, Meeran S, Katiyar N, Katiyar S. Grape seed proanthocyanidins inhibit the growth of human non-small cell lung cancer xenografts by targeting insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3, tumor cell proliferation, and angiogenic factors. Clinical Cancer Research 2009; 15:821–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mao JT, Xue B, Smoake J, Lu QY, Park H, Henning SM, et al. MicroRNA-19a/b mediates grape seed procyanidin extract-induced anti-neoplastic effects against lung cancer. J Nutr Biochem 2016; 34:118–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mao JT, Smoake J, Park HK, Lu QY, Xue B. Grape Seed Procyanidin Extract Mediates Antineoplastic Effects against Lung Cancer via Modulations of Prostacyclin and 15-HETE Eicosanoid Pathways. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2016; 9(12):925–932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xue B, Lu QY, Massie L, Qualls C, Mao JT. Grape seed procyanidin extract against lung cancer: the role of microrna-106b, bioavailability, and bioactivity. Oncotarget 2018; 9(21):15579–15590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deprez S, Mila I, Huneau J, Tome D, Scalbert A. Transport of proanthocyanidin dimer, trimer, and polymer across monolayers of human intestinal epithelial caco-2 cells. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling 2001; 3:957–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scalbert A, Williamson G. Dietary intake and bioavailability of polyphenols. J Nutr 2000; 130:2073S–85S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vigna GB, Costantini F, Aldini G, Carini M, Catapano A, Schena F, et al. Effect of a standardized grape seed extract on low-density lipoprotein susceptibility to oxidation in heavy smokers. Metab Clin Exp 2003; 52:1250–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mao L, Papadimitrakopoulou V, Shin DM, Fan YH, Zhou X, Lee JS, et al. Phenotype and genotype of advanced premalignant head and neck lesions after chemopreventive therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst 1998; 90:1545–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee JJ, Liu D, Lee JS, Kurie JM, Khuri FR, Ibarguen H, et al. Long-term impact of smoking on lung epithelial proliferation in current and former smokers. J Natl Cancer Inst 2001; 93:1081–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martin B, Paesmans M, Mascaux C, Berghmans T, Lothaire P, Meert AP, et al. Ki-67 expression and patients survival in lung cancer: systematic review of the literature with meta-analysis. Br J Cancer 2004; 91:2018–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mao JT, Fishbein MC, Adams B, Roth MD, Goodglick L, Hong L, et al. Celecoxib decreases Ki-67 proliferative index in active smokers. Clin Cancer Res 2006;12(1):314–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim ES, Hong WK, Lee JJ, Mao L, Morice RC, Liu DD, et al. Biological activity of celecoxib in the bronchial epithelium of current and former smokers. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2010; 3:148–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mao JT, Roth MD, Fishbein MC, Aberle DR, Zhang ZF, Rao JY, et al. Lung cancer chemoprevention with celecoxib in former smokers. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2011; 4:984–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization factsheet on cancer. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mao JT, Durvasula R. Lung cancer chemoprevention: Current status and future direction. Current Respiratory Care Reports 2012; 1:9–20. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fisher B, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, Cecchini RS, Cronin WM, Robidoux A, et al. Tamoxifen for the prevention of breast cancer: current status of the national surgical adjuvant breast and bowel project P-1 study. J Natl Cancer Inst 2005; 97(22):1652–1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meyskens FL Jr, Mukhtar H, Rock CL, Cuzick J, Kensler TW, Yang CS, et al. Cancer Prevention: Obstacles, Challenges and the Road Ahead. J Natl Cancer Inst 2015;108(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Merrick DT, Gao D, Miller YE, Keith RL, Baron AE, Feser W, et al. Persistence of bronchial dysplasia is associated with development of invasive squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2016; 9(1):96–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ishizumi T, McWilliams A, MacAulay C, Gazdar A, Lam S. Natural history of bronchial preinvasive lesions. Cancer Metastasis Rev 2010; 29:5–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lortet-Tieulent J, Soerjomataram I, Ferlay J, Rutherford M, Weiderpass E, Bray F. International trends in lung cancer incidence by histological subtype: adenocarcinoma stabilizing in men but still increasing in women. Lung Cancer 2014; 84:13–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hammond SM, RNAi, microRNAs, and human disease. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2006; 58: Suppl 1:s63–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mitchell PS, Parkin RK, Kroh EM, Fritz BR, Wyman SK, Pogosova-Agadjanyan EL, et al. Circulating microRNAs as stable blood-based markers for cancer detection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2008; 105:10513–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boeri M, Verri C, Conte D, Roz L, Modena P, Facchinetti F, et al. MicroRNA signatures in tissues and plasma predict development and prognosis of computed tomography detected lung cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2011; 08:3713–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keith RL, Blatchford PJ, Kittelson J, Minna JD, Kelly K, Massion PP, et al. Oral iloprost improves endobronchial dysplasia in former smokers. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2011; 4(6):793–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hansen AR, Graham DM, Pond GR, Siu LL. Phase 1 trial design: is 3 + 3 the best? Cancer Control 2014; 21(3):200–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]