Abstract

Purpose

To identify published literature regarding cancer survivorship education programs for primary care providers (PCPs) and assess their outcomes.

Methods

PubMed, Embase, and CINAHL databases were searched between January 2005 and September 2020. The Quality of Cancer Survivorship Care Framework and Kirkpatrick’s 4-level evaluation model were used to summarize program content and outcomes, respectively. Data extraction and critical appraisal were conducted by two authors.

Results

Twenty-one studies were included, describing self-directed online courses (n=4), presentations (n=2), workshops and training sessions (n=6), placement programs (n=3), a live webinar, a fellowship program, a referral program, a survivorship conference, a dual in-person workshop and webinar, and an in-person seminar and online webinar series. Eight studies described the use of a learner framework or theory to guide program development. All 21 programs were generally beneficial to PCP learners (e.g., increased confidence, knowledge, behavior change); however, methodological bias suggests caution in accepting claims. Three studies reported positive outcomes at the patient level (i.e., satisfaction with care) and organizational level (i.e., increased screening referrals, changes to institution practice standards).

Conclusions

A range of cancer survivorship PCP education programs exist. Evidence for clinical effectiveness was rarely reported. Future educational programs should be tailored to PCPs, utilize an evidence-based survivorship framework, and evaluate patient- and system-level outcomes.

Implications for Cancer Survivors

PCPs have an important role in addressing the diverse health care needs of cancer survivors. Improving the content, approach, and evaluation of PCP-focused cancer survivorship education programs could have a positive impact on health outcomes among cancer survivors.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11764-021-01018-6.

Keywords: Cancer, Education, Evaluation, Primary care, Survivorship, Theory

Background

Advances in early detection, diagnostics, and treatment have resulted in an increase in cancer survivors living with and beyond cancer. As of 2018, there were approximately 43.8 million cancer survivors worldwide [1], a number that is projected to grow substantially over the next 15 years [2]. In addition to the risk of subsequent primary cancer and cancer recurrence, many cancer survivors will experience late and long-term side effects as a result of their cancer and treatment, along with new and pre-existing comorbidities [3]. As global cancer survival rates continue to improve, the need to address the range of physical, psychological, and psychosocial needs of survivors through continuous follow-up support is paramount. The challenges of addressing the long-term health care needs of an increasing number of cancer survivors, along with the projected shortage and pressure on the specialist oncology workforce [4–6], have led to a call for primary care providers (PCPs) to move beyond the traditional focus on cancer prevention and early detection [7], to the provision of post-treatment follow-up survivorship care [7–12].

The benefits of integrating primary care into cancer survivorship follow-up care are well established, resulting in enhanced continuity and satisfaction of care [13, 14], as well as improved or similar physical and psychosocial well-being of cancer survivors [15–18]. Despite the clear importance of the primary care team in survivorship care, limited data on the engagement of PCPs in survivorship care exist. Moreover, several studies have demonstrated a need for quality cancer survivorship education within the primary care workforce, with PCPs often reporting a lack of appropriate knowledge [19–21], training [22, 23], and confidence [19, 20, 24–26] in providing adequate cancer survivorship support. Additionally, there is a critical need for cancer survivorship curricula, relevant to the primary care provider role, to be formally integrated into primary care residency training (e.g., internal/general medicine) as deficiencies in existing programs and syllabuses (e.g., self-reported unpreparedness for practice in cancer survivorship, low levels of survivorship training or education) have been widely reported in literature [27–30]. Despite several calls to action [7, 9], a recent cross-sectional study [27] identified that among 249 family medicine programs in the USA, only 9.2% reported having a cancer survivorship curriculum or program.

Primary care providers are well placed to deliver quality patient-centered survivorship follow-up care; and thus, competency in cancer survivorship is essential. While studies have investigated perspectives of PCPs in providing survivorship care and have highlighted the importance of addressing training deficiencies, a systematic evaluation of existing survivorship education programs targeted towards the primary care workforce has not been completed. This is necessary to determine the impact and outcomes of education program components as well as to establish more specific, actionable recommendations. Accordingly, this systematic review was conducted to identify and evaluate existing PCP cancer survivorship programs in published literature and answer the following questions: (1) What are the behavioral/learning theories, pedagogy, and/or frameworks used in PCP survivorship education programs? (2) What are the effects of PCP survivorship education programs on outcomes for PCPs (e.g., knowledge, attitude, behaviors) and for cancer survivors (e.g., health and clinical outcomes, self-efficacy)?

Methods

This systematic review was prepared and reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [31] (Supplementary 1). The review was registered with PROSPERO (No. CRD42021223836), where a protocol was submitted. The current review has been conducted in accordance with that protocol.

The Quality of Cancer Survivorship Care Framework [32] was used to define survivorship care and guide article inclusion. This framework is similar to the ASCO Core Curriculum for Cancer Survivorship but provides more detailed information to guide the classification and categorization of survivorship content [33]. Education programs were considered “survivorship care programs” if they described or contained at least one of the following core domains: (1) cancer and cancer treatment (prevention and surveillance for recurrences and new cancers; surveillance and management of physical effects; surveillance and management of psychosocial effects; surveillance and management of psychosocial effects); (2) general health care (surveillance and management of chronic medical conditions; health promotion and disease prevention); and (3) contextual domains (clinical structure; communication and decision-making; care coordination; patient/caregiver experience). A description of these domains is displayed in Supplementary 2. Further, in accordance with this framework, palliative and end-of-life care were not included under this scope of survivorship care.

For this review, an educational program was defined using the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization’s (UNESCO) International Standard of Classification of Education [34]. In this classification an education program is defined as:

A coherent set or sequence of educational activities designed and organized to achieve pre-determined learning objectives or accomplish a specific set of educational tasks over a sustained period. Within an education programme, educational activities may also be grouped into sub-components variously described in national contexts as ‘courses’, ‘modules’, ‘units’ and/or ‘subjects’. A programme may have major components not normally characterized as courses, units or modules – for example, play-based activities, periods of work experience, research projects and the preparation of dissertations.

This includes, but is not limited to workshops, curricula, seminars, webinars, courses, training sessions, modules, coaching sessions, role-play sessions, fellowships, placement programs, self-based learning, and lectures.

Selection criteria

Study titles were considered eligible for inclusion if the study or program evaluated met the following criteria: (1) describe a “survivorship care program” as per the above definition, (2) describe and evaluate an education program, (3) report outcomes of the evaluation, (4) explicitly specify PCPs as the intended participants of the program or include PCPs as a learner type, and (5) be written in English. Only studies published after 2005 were included as this was the year the Institute of Medicine (IOM) published the seminal From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition report [8]. Further, only articles or abstracts with published evaluated outcomes were eligible for inclusion. To ensure review comprehensiveness, original research articles (any methods), conference abstracts, and other grey literature with evaluated outcomes (e.g., online modules, institutional training programs, e-learning programs) were included. No restrictions were placed on setting or modality of survivorship education programs (i.e., web-based, face-to-face, telephone).

Search strategy

Three databases (PubMed, Embase, and CINAHL) were searched between January 2005 and September 2020 using the search strategy listed in Supplementary File 3. Reference lists of all full text articles were checked for potentially relevant programs and studies. Google Scholar was also searched for additional studies. Titles and abstracts of articles retrieved from the search strategy were independently screened by two authors (RC, OAA). The same two authors then assessed the eligibility of relevant full-text articles for inclusion in the review. Disagreements were resolved through consensus among the two authors, with a third author (LN) as arbiter where required.

Data extraction

Data extraction was conducted by one author (OAA) and checked for accuracy by a second author (MC and RC). Key information extracted included author, publication year, study type, research methods, program/resource objectives, curriculum content, pedagogy, learning theories used, course participants, and survivorship components. Survivorship components were included if they were explicitly listed in the study or were attained via external information (e.g., ancillary documents, internet resources, education program website, study author confirmation, review team knowledge). Study outcomes were categorized and synthesized using Barr’s adaptation (the addition of two sub-domains) of Kirkpatrick’s 4-level model of evaluation [35] displayed in Supplementary File 4. This model specifies four levels of training evaluation: reaction, views on learning experience; learning, the modification of learner attitudes and acquisition of knowledge and skills; behavior change, the transfer of learning to the workplace; and results, changes in organizational practice or benefits to patients. Survivorship program content was independently categorized by two authors (OAA and RC) using the Quality of Cancer Survivorship Care Framework, with inclusion of special populations considerations (e.g., adolescents and young adults, geriatric populations). Disagreements regarding data extraction were discussed and resolved between the two authors.

Quality assessment and analysis

Quality assessment of pre-test, post-test studies was undertaken using the NIH “quality assessment tool for before-after (pre-post) studies with no control group” [36]. Post-test only studies were also appraised using this tool, with items pertaining to pre-test, post-test differences recorded as “not applicable.” Mixed-methods studies were appraised using the mixed-methods appraisal tool [37]. Disagreements regarding methodological quality of the studies were discussed and resolved between two authors (OAA and MC). If consensus was not reached, a third author (RC) acted as arbiter. Review findings were presented in narrative form due to study heterogeneity.

Results

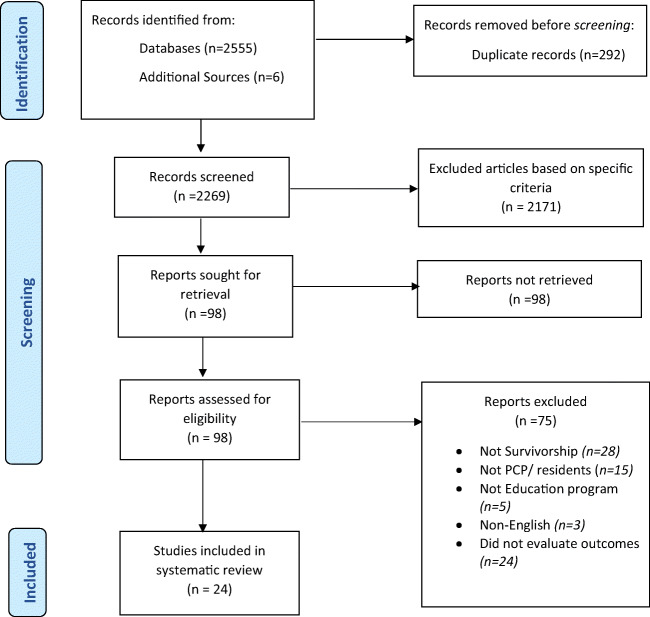

Database searches resulted in 2555 potentially eligible records. Of these, 24 articles (seven abstracts and 17 full text studies) representing 21 studies and evaluating 21 unique survivorship education programs [38–58] met the inclusion criteria and were included in the review (see PRISMA flow chart: Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for systematic reviews

Characteristics of included studies

Studies characteristics are detailed in Table 1. All 21 studies utilized single-group designs with no comparators. Thirteen studies [38–40, 42, 43, 45, 46, 48, 51, 55–58] used a pre-test, post-test design. Five studies used a post-test only design [41, 47, 49, 53, 54], two studies used a mixed-methods approach [44, 52], and one study had an unspecified methodology [50]. Of the 21 survivorship education programs evaluated within these studies, 15 were developed in the USA [38, 39, 41–50, 52, 55, 57], three were developed in Australia [51, 56, 58], one in Germany [54], and two in Canada [40, 53]. Target learners for these programs were PCPs or residents in primary care training, including internal medicine residents [46], pediatric physician residents [55], PCPs only [38–43, 45, 47, 48, 51, 56, 58], and mixed health professional groups including PCPs [44, 49, 50, 52–54, 57].

Table 1.

Summary of included articles

| Study Type | Research Methods (sample size, evaluation methods) |

Participants | Objective/ Aims/ Research Questions | Theories, Mode, Pedagogy | Content/ Curriculum | Outcomes | Kirkpatrick Level | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Berrett-Abebe et al. 2018 & 2019 [38] Cost: NR Country: USA |

Pre-test, post-test |

Methods: pre-test, post-test questionnaire on knowledge, self-efficacy, program satisfaction (5-point Likert scale; 1=strongly disagree, 5=strongly agree), and confidence (11-point Likert scale; 0=not confident at all, 10=extremely confident) Sample: n=46 (Physicians (n=28); Physician’s assistant (n=5); nurse practitioners (n=3); nurses (n=8); social workers (n=2) who practiced in primary care settings.) |

PCPs involved in care of cancer survivors | Increase knowledge and self-efficacy of inter-professional PCP on identifying and addressing fear of cancer recurrence in clinical practice |

Mode: Face-to-face training session (approx. 30 minutes) Framework/Theory: Social Cognitive Theory and Kirkpatrick’s Evaluation of Training Programs |

• 30-minute session with 6 core components. Curriculum: • Patient FCR narrative (3-min video) • PowerPoint presentation on cancer survivorship, late effects and psychosocial distress • Information on FCR (i.e., prevalence, clinical significance, etc.) • Interventions to manage FCR (i.e., education, normalisation, lifestyle, referrals to other resources, etc.) • Information on screening for FCR • Additional resources |

• Increase in pre- to post-test scores in FCR knowledge (mean composite knowledge score: pre-test M= 3.21/5, SD= .71 and post-test M=4.03/5, SD =.56, t = − 7.10, df= 45, p < .001) • Increase in learner FCR self-efficacy (mean composite self-efficacy scores: pre-test M= 2.95/5, SD = .69 and post-test M= 3.95/5, SD = .44, t = − 9.58, df= 45, p <.001.) |

2b |

| • Increased confidence in applying training to practice (M=7.67/10, SD = 1.25, p NR) | 2a, 3 | |||||||

| • Learners reported training session was relevant and useful to clinical practice, provided enough time for discussion and participants would recommend to other PCPs. | 1 | |||||||

|

Buriak et al. 2014 [39] Cost: Free Program Name: Cancer Survivorship: A Primer for Primary Care Program Link: https://www.medscape.org/qna/preactivity/24653?formid=4&dest_url=https://www.medscape.org/viewarticle/763570 Country: USA |

Pre-test, post-test |

Methods: Four question multiple choice survivorship pre-test, post-test. Questions addressed the following: 1. Risk factors of breast cancer survival 2. Late effects of prostate treatment 3. Surveillance and follow-up for subsequent primary cancers 4. Knowledge on the use of CAM for survivors Included a program evaluation survey (5 point Likert scale; 1=strongly agree, 5=strongly disagree). Sample: n=1,521 [MDs (n =126), NPs (n =183) and RNs (n =1,168), PAs (n =31), and DOs (n =13)] |

United States clinicians voluntarily seeking online CME/CE credit | To address the survivorship knowledge gap in breast cancer, prostate cancer and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (e.g., identification of late effects, survivor surveillance, prevention methods & management stratinformation into practice) |

Mode: Online, web-based: via the “Medscape Education (WebMD) platform” Framework/Theory: Analysis, Design, Development, Implementation, Evaluation Mayer's 12 evidence-based principles for multimedia–modality, interactivity, and spatial contiguity Pedagogy: Educational material constructed using the Gagne ‘nine-step’ Gagne model: (1) gain attention, (2) present learning objectives, (3) stimulate recall of prior knowledge, (4) present educational content, (5) provide learner guidance, (6) measure performance, (7) provide feedback, (8) assess knowledge, (9) enhance retention and transfer. Also utilised the revised version of Bloom’s taxonomy for creating educational objectives. |

Curriculum: Online course covered: • Epidemiology of each condition (breast, prostate cancer & non- Hodgkin’s lymphoma) - Prevalence, lifetime risk, mortality, incidence, late effects, psychosocial stressors, survivor concerns • Survivor issues - Survivor stories (videos) - IOM video clips from survivorship experts - Case scenarios (w/discussion regarding diagnosis, patient evaluation and management strategies) - Practice non-graded questions with targeted feedback • Links to relevant resources & guidelines (using patient cases) - SCP templates - Links to: AAFP, ASCO, NCCN, NCI, and PDR surveillance and follow-up guidelines |

• Increase in knowledge (from pre-test to post-test) with a large effect size (d=1.72, p<0.0005). • Significant knowledge gain observed across all four questions. |

2b |

|

• 99% stated the course promoted improvement in survivorship care. • 97% reported the course was designed effectively. |

1 | |||||||

| Pre-test, post-test | United States clinicians voluntarily seeking online CME/CE credit |

Intent to implement changes based on program participation: • 63% reported they would adopt alternative communication strategies with patients and families. • 14% would modify treatment plans. • 12% would incorporate different diagnostic strategies into patient evaluation. • 11% would change screening/ prevention practice. |

3 | |||||

|

Buriak et al. 2015 [59] Cost: Free Program Name: Cancer Survivorship: A Primer for Primary Care Program Link: https://www.medscape.org/qna/preactivity/24653?formid=4&dest_url=https://www.medscape.org/viewarticle/763570 Country: USA |

Methods: Post-course questionnaire to obtain info about years of experience in clinical practice, clinical perception of barriers, identification of barriers, survivorship status and level of intent to provide survivorship care. Self-reported intention to change questionnaire Sample: 1809 [physicians (n = 229), NPs (n = 213) and RNs (n = 1367)]. |

Evaluation of intention to provide PCP survivorship care & identification of PCP barriers to provision of survivorship care. |

• Clinicians with 6-10 years’ experience were almost 3 times more likely to intend to provide survivorship care (OR = 2.86, p = .045, 95% CI 1.02, 7.98). • Clinicians were 1.8 times more likely to have diminished intent when they perceived presence of a barrier (OR = 1.89, p = .035; 95% CI, 1.04, 3.42). • MDs and DOs experienced more barriers to providing survivorship care and were less likely to have intent to provide survivorship care than RNs. |

3 | ||||

|

* Chaput et al. 2018 [40] Cost: NR Country: Canada |

Pre-test, post-test |

Methods: one pre-program questionnaire, one questionnaire at program completion and one questionnaire three months post-program completion (Likert scale & short answer questions) Sample: 167 PCPs |

PCPs | Increase PCP confidence and knowledge of survivorship care. |

Mode: In person, face-to-face Framework/Theory: Workshop measures targeted 3 levels of Kirkpatrick’s learning model: satisfaction, knowledge, and behaviour. |

A 60-minute survivorship workshop. Curriculum: based on the NCCN’s eight common survivor issues (i.e., anxiety and depression, cognitive decline pain, female and male sexual dysfunction, immunisations and prevention of infections, fatigue, sleep disorders, and exercise). |

• Immediately post-workshop: Significantly more likely to be able to the list the standards of survivorship, t (108)=5.52, p<0.001. |

2b |

| • 95% of learners reported high workshop satisfaction. | 1 | |||||||

| • 99% of learners expressed intent to incorporate information learned into practice. | 3 | |||||||

|

• 3 months post-workshop: Confidence remained higher than pre-intervention levels for knowledge of late physical effects (Z=6.08, p<0.001, n=60) and adverse psychosocial outcomes of cancer and treatments (Z=4.26, p<0.001, n=62) |

2a | |||||||

|

*Daly et al. 2016 [41] Cost: NR Program Name: Fox Chase Cancer Center (FCCC) Care Connect Program Country: USA |

Post-test only |

Methods: 3-month pilot Sample: PCPs across 5 PCP practices. |

PCPs | To connect PCPs with cancer centre providers. | Mode: In-person, placement program |

• Placement program required PCP learners to attend 2 of 4 targeted professional programs and participate in quality screening measures for cervical, breast and colon cancer. • Learners then received access to cancer centre disease navigation services via a physician portal to coordinate clinical needs of patients. • Cancer survivors were then directed from oncologists to PCP learners to manage clinical needs and implement survivorship plans. Curriculum: Content based on NCCN’s 8 common survivor issues - anxiety and depression; cognitive decline; pain; female and male sexual dysfunction; immunizations and prevention of infections; fatigue; sleep disorders; exercise. |

• 91% of PCP learners reported intent to change current practice by implementing a new procedure, discussing new information or seeking additional information. | 3 |

|

• Post program completion: one PCP practice referred three patients to a lung cancer screening program. • 19 patients referred to learner PCPs. Median time from referral to PCP appointment was 16 days (24% below regional average). |

4a | |||||||

|

Donohue et al. 2019 [42] Cost: NR Country: USA |

Pre-test, post-test |

Methods: pre- and post-session 10 question survey assessing: • Knowledge about which cancer patients and/or PCP receive/use SCPs • Timing of SCP provision • Expected SCP content • Location of SCPs in the UW Health system Free text questions on program improvement. Sample: 287 physicians and APPs providers (203 family medicine providers and 84 General Internal Medicine providers). |

PCPs from the University of Wisconsin Division of General Internal Medicine and the Department of Family Medicine and Community Health | Increased PCP and advanced practice providers knowledge of SCP content and use. |

Mode: Face-to-face. 191 (66.6%) participants attended an in-person session. All participants (n=287) also received copy of the program presentation. |

Three sessions delivered over 3 weeks. • Session 1: 15-minute primary care-directed education program. • Session 2: 10-minute PowerPoint presentation consisting of: • What is a survivorship care plan? • Why do we use SCPs? • What information does an SCP contain? • Who receives a SCP? • When do we give SCPs to patients? • Where are they located (on health link)? • Session 3: Five-minute discussion and question session. |

• Out of the participants that completed both the baseline and follow-up survey (n=39) there was a statistically significant increase in: • Ability to identify SCP location in intranet system: 10% vs 67% (p<0.0001) • Knowledge on timing of SCP provision: 26% vs 69% (p<0.0001) • Knowledge on which patients can receive a SCP: 36% vs 69% (p=0.0008) • Between the baseline and follow-up survey there was no significant increase learner’s knowledge of intended SCP recipients (both the patient and primary care team) 90% vs 92% (p=0.65) |

2b |

| • Respondents provided recommendations on SCP improvement. | 1 | |||||||

|

Evans et al. 2016 [58] Cost: NA Country: Australia |

Pre-test. Post-test |

Methods: pre-placement and post-placement semi-structured interviews. Sample: 16 GPs and 12 General Practice Nurses |

PCPs | To provide opportunity for knowledge and skills transfer. | Mode: In-person clinical placement program |

10-hour placement at a tertiary cancer centre. Placement incorporated attendance and participation at multidisciplinary meetings and outpatient clinics to observe decision-making and treatment planning of cancer survivors. Pre-placement material included general survivorship care information relevant to primary care and videos describing relevant cancer survivor issues. |

• PCP learners felt learning was relevant to practice. Personal and program goals were partially or completely met. • PCP learners requested: more structured education and quality improvement activities. • Need for education in new therapies & treatment options, their side effects and impact on co-morbidities. |

1 |

|

• Creation of collaborative relationships between specialists and PCPs • Confidence to work in shared care. • Increased awareness of the need to facilitate cancer survivor care chronic disease management protocols that support post-treatment survivorship care, and knowledge gaps. |

2a | |||||||

| • Perceived knowledge and skills transfer | 2b, 3 | |||||||

|

Fullbright et al. 2020 [43] Cost: Registration cost “Less than $5 USD per CME credit hour per person)” Program Name: Cancer Survivorship Training for Healthcare Professionals Program Link: https://www.cancersurvivorshiptraining.com/longtermfollowup Country: USA |

Pre-test, post-test |

Methods: Stepwise process consisting of 3 different educational platforms (in-person seminar, live webinar series & an online course). Pre-post-test assessment on general long-term follow-up, pulmonary late effects, secondary malignant neoplasms & cardiac late effects. Sample: Seminar n=35 (mostly oncology providers). Webinar n=46 (1 PCP, 45: NR). Online Course: n=90 (12.5% PCPs). |

Primary care teams and specialists. | To increase clinician knowledge regarding care for adult childhood cancer survivors |

Mode: in person, face-to-face seminar. Online, web-based webinar series & online course/learning system. Theories/Frameworks: Adult Learning Theory |

One day seminar on prevalent late effects and management strategies for childhood cancer survivors (CCS). Content: • Overview of caring for adult CCS (from PCP perspective) • Secondary malignancy & genetic testing • Common late effects affecting cardiovascular, pulmonary and endocrine function (with case-based examples) • Monitoring and screening for late effects • Intervention and management strategies Online webinar series: 14 live one-hour long webinar provided over a 5-month period. Content: • Common secondary malignancies, cardiac dysfunction, cardiovascular disease, fertility problems and options for male/female CCS, emotional late effects, practical and financial challenges, educational and vocational challenges, metabolic risks & bone health, thyroid dysfunction, gonadal failure, pituitary dysfunction, coordinated approach to care. • Children’s Oncology Group Long-term follow up Guidelines guided content. |

• One-day seminar: 35% improvement in secondary malignancy knowledge between pre- and post-seminar. |

2b |

|

• Webinar: • 78% of learners reported that ≥50% of the information provided was new. • Participants conveyed intention to change practice (identification of cancer survivors in their practice to implement follow-up guidelines, improved referrals, and identification of gonadal dysfunction during scheduled appointments, provision of management strategies, discussion fertility, and provision of routine screening for psychosocial late effects). |

3 | |||||||

|

• Online Learning System (course): • Significant improvement of mean pre-tests to post-test knowledge scores (73.85% to 95.3%). |

2b | |||||||

| • Learners found course content and learning experience favourable. | 1 | |||||||

|

Grant et al. 2012 [44] Cost: NR Program Name: Survivorship Education for Quality Cancer Care Country: USA |

Mixed methods approach |

Methods: Survey Telephone interviews held 6, 12- and 18-months post-course to determine/evaluate goal progress and provide support. Institutional 7-item survey five 10-point Likert scale questions; 2 free text) Sample: 408 individual participants [Admin n=131 (32%); social workers N=66 (16%); NP n=59 (15%); RN n=57 (14%); Physicians n=36 (9%); PhD n=13 (3%)] 204 multidisciplinary teams [community cancer centres; n=133 (65%), academic centres n=54; (27%); paediatric centre n=9 (4%); ambulatory/ physician offices n=4 (2%); free-standing cancer centre n=4 (2%)]. |

HCPs | To provide HCPs with training to improve survivorship care for cancer survivors. To create a cancer survivorship curriculum for health care professionals |

Mode: In person, face-to-face Framework/Theories: Institutional change theory and Adult learning principles |

Two and a half day in-person course (organised annually). Course participants attended in teams (groups of two). Curriculum: • Course content included: overview of survivorship care, integrating survivorship care into the continuum of care; health outcomes after paediatric cancer; survivorship for AYA; physical wellbeing, psychological well-being; NCCS and survivorship movement; cancer survivor perspective; starting a survivorship clinic; social wellbeing and survivorship; spirituality and survivorship; institutional change & support opportunities for survivorship programs. • The Quality-of-Life Model for Cancer Survivors (four domains: physical, psychological, social & spiritual) and IOM recommendations guided content. |

• Participants reported the course was well-planned and well provided. | 1 |

| • Increase in scores for the effectiveness (4.51 vs 7.06; p<0.05) and comfort (5.79 vs 7.82; p<0.05) of staff (and their respective institutional settings) in providing survivorship care. | 2a, 3 | |||||||

| • Participating institutions reported significant changes to institution vision and management, practice standards, psychosocial and social care, communication, quality improvement, patient and family education and communication networks as survivorship goals were implemented. | 3, 4a | |||||||

|

• 98% of participants reported that attending the course motivated survivorship care in their respective institutional settings. • Learners reported a lack of administrative support and financial constraints as barriers to improving survivorship care at institutions |

4a | |||||||

|

Harvey et al 2018 [45] Cost: Free Program Name: The Cancer survivorship E-Learning Series for Primary Care Providers Program Link: http://gwcehp.learnercommunity.com/elearning-series Country: USA |

Pre-test, post test |

Methods: Learners completed a pre- and post-assessment (5-point Likert scale; 1=strongly disagree, 5=strongly agree) for each learning module (10 modules total). Each assessment rated the learner’s confidence to meet the learning objectives of the specific module (3-to-4 different learning objectives per module). Free text open-ended question to offer program feedback. Sample: 1341 HCPs [oncology n=985 (74.68%); primary care n=153 (11.6%); public health n=21 (1.59%); other n=101 (7.66%); did not wish to specify n=59 (4.47%)]. |

Physicians, physicians’ assistants, nurses, and Certified Health Education Specialists HCPs |

To provide continuing cancer survivorship training, education & credits/contact hours to health care professionals (with a focus on PCPs) |

Mode: Online, web-based Framework: Kirkpatrick Evaluation Model |

Program originally intended for PCPs but later expanded to include all HCPs. 10-module (self-paced) online course. Learners complete modules based on their needs/interests. Approx. 1 hour per module. Curriculum: • The Current State of Survivorship Care and the Role of Primary Care Providers • Managing Comorbidities and Coordinating with Specialty Providers • Meeting the Psychosocial Health Care Needs of Survivors • The Importance of Prevention in Cancer Survivorship: Empowering Survivors to Live Well • Survivorship Care Coordination & Advancing Patient-Centred Cancer Survivorship Care • Cancer Recovery and Rehabilitation Course also included links to additional resources (not specified). Modules 7,8,9,10 addressed Clinical Follow-Up Care Guidelines for Primary Care Providers for prostate, colorectal, breast and, head and neck cancer respectively. Modules 7, 8,9,10 based on the American Cancer Society Survivorship Clinical Care Guidelines. |

• Increase in mean pre- to post- assessment of self-confidence rating for aggregated learning objectives (0.66 to 0.92, p<0.0001) | 2a |

|

• Change in mean confidence rating for all modules (p<0.0001) • Change in mean confidence for each individual learning objective in each module (p<0.0001). • 92% of learners reported their knowledge was enhanced. • 83% of learners reported they had gained new skills/strategies/information that could be applied to practice. |

2b | |||||||

| • 75.38% of learners planned to implement skills/strategies/information into practice | 3 | |||||||

|

Jacob et al. 2018 [46] Cost: N/A Country: USA |

Pre-test, post test |

Methods: Learners given a multi-choice knowledge questionnaire (4 questions on survivorship terminology/ treatment side effects) & two questions on comfort in managing survivors) the first and last day of workshop. Sample: 87 internal medicine residents |

Internal medicine residents | To inform internal medicine residents of cancer survivorship concepts. | Mode: Face-to-face, in-person |

3-session workshop (sessions 50 minutes each) Curriculum: residents followed a simulated case (geriatric breast cancer survivor) through to outpatient primary care. • Session 1: creating a SCP, discussing breast cancer surveillance & subsequent primary cancer screening. • Session 2: Discussion of physical symptoms, long term side effects of treatment, primary tumour recurrence & secondary malignancy. • Session 3: review of case progression, provision/discussion of mental health assessment & late recurrence. • Review article: “In the Clinic: Care of the Adult Cancer Survivor” given to residents prior to workshop as preparation. • American Cancer Society/ American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Breast Cancer Survivorship Care Guideline informed curriculum. • Residents used ASCO Treatment Summary and Survivorship Care Plan as a SCP template. |

• Residents reported improvement in knowledge of how to find or create a SCP. • Improvement in comfort with screening for excess mortality (long term side effects). |

2a |

| • Minimal change in general knowledge before and after the curriculum. | 2b | |||||||

|

Meachem et al. 2012 [47] Cost: Free Program Name: Cancer SurvivorLink (provider portal) Program Link: www.cancerSurvivorlink.org Country: USA |

Post-test evaluation |

Methods: Online program informed by PCP interviews and feedback from in-person lecture sessions (feedback methods not specified) Sample. In-person lecture sessions: 58 nurses, 57 physicians, 21 social workers Online SurvivorLink Program: 12 months after online launch – 471 unique visitors and 1,129 total visits. |

Primary and non-oncology speciality providers | Increasing PCP awareness and knowledge of best practices in paediatric survivorship care. |

Mode: Lecture sessions - in-person, face-to-face. SurvivorLink Program - online |

Web-based survivorship education tools were on the provider portal of the SurvivorLink online program. Resources included: • QuickFacts – brief summaries indicating the late effects associated with each type of cancer therapy • CE modules: SurvivorCare 101 (introduction to childhood cancer survivorship – neurocognitive late effects, endocrine late effects); Gonadal dysfunction of childhood cancer; growth and weight problems after treatment; thyroid problems after treatment; video modules – living beyond cancer • Additional Resources – links to educational resources & guidelines (e.g., Children’s Oncology Group, Livestrong, American Cancer Society). • Access to a patient’s SurvivorLink Health Record Curriculum: Children’s Oncology Group Long Term Follow Up Guidelines |

In-person education sessions • Attendees felt the information received was useful to practice. • 95% of attendees would recommend the session to others. SurvivorLink Website • Most frequently viewed pages were the QuickFacts pages – SurvivorCare 101., neurocognitive, & endocrine late side effects pages. |

1 |

|

In-person education sessions • 98% of attendees believed the lectures increased their awareness of healthcare needs in survivors and ability to describe a survivor health care plan. |

2a | |||||||

|

*Merriam et al. 2018 [48] Cost: NR Country: USA |

Pre-test, post-test |

Methods: pre- and post-intervention 5-item knowledge quiz and survey. Sample: 43 medical providers; 21 completed pre- and post-survey (38% physicians and 62% APPs). Majority of sample trained in internal medicine. |

PCPs | To improve PCPs knowledge comforts, attitudes, and skills to communicate, identify and manage common sexual problems in female cancer survivors. |

Mode: in-person, face-to-face workshop Framework/Theory: 5A’s communication skills framework |

Half day educational workshop. Included a role play session with standardised (simulated) patients, post workshop to practice the 5A’s communication skills taught. Content: Not recorded |

• No difference in performance on knowledge-based quiz post-workshop. | 2b |

|

• Increased comfort with providing survivorship care (p=0.04) • Increased comfort exploring causes of sexual dysfunction (p=0.01) • Increased knowledge of treatment options for issues contributing to sexual dysfunction (p=0.01) |

2a | |||||||

|

• Agreement PCPs should explore problems with sexual function (p=0.02) • Increased use of 5A’s communication skills during post-workshop skills evaluation. |

3 | |||||||

|

Nolan et al. 2019 [49] Cost: NR Country: USA |

Post-test only |

Methods: APP fellows completed a 6-item evaluation post-clinical rotation. Sample: 10 APPs & 10 program facilitators |

APPs | To provide oncology-specific experience and clinical experiences/ skills. | Mode: In-person, face-to-face clinical rotation |

Fellowship program incorporating a 2-week cancer survivorship rotation at a survivorship clinic. Content: • Survivorship lecture: introduction to survivorship care (ASCO, NCCN, COC), treatment summaries and SCPs, available supportive care services and referral guides • Experiences with survivors: shadowing an APP; creating and delivering treatment summary/SCPs; shadowing speciality supportive care visits (e.g., counselling, physical therapy). • ‘Literature libraries’: Binder provided that contained evidence-based guidelines, instructions on SCP construction; relevant journal articles • Other resources: Completion of the “Cancer Survivorship E-learning Series for Primary Care Providers” (from GWU) • Familiarisation with the available supportive care services and resources |

• All fellows and program facilitators reported that the program benefited participants. • 5 program facilitators agreed the two weeks clinical rotation was sufficient and 4 preferred four weeks duration. |

1 |

|

• Program facilitators very satisfied (n=9/10) or mostly satisfied (n=1/10) with fellows’ clinical performance during rotations. • Facilitators reported fellows were more well-rounded and had sufficient knowledge of survivorship care principles. |

2b | |||||||

|

*Perloff et al. 2019 [50] Cost: NR Country: USA |

Unspecified |

Methods: Curriculum developed by oncology specialist, nurse, social worker and patient and delivered as a webinar. Sample: 149 learners (49% oncology) |

HCPs | To educate multidisciplinary care teams on survivorship care practices for patients undergoing immunotherapy | Mode: online, web-based |

Live online 1-hour webcast consisting of presentation slides, panel discussion and learner questions. The webinar was made available online. Content: Not Recorded |

• Estimated 590 patients per month impacted by webinar | 4b |

| • Learners engaged for 35 minutes out of 52 minutes. | 1 | |||||||

|

• 97% reported improvements in their ability to identify solutions for immunotherapy survivorship care planning. • 88% reported improvements in their ability to handle nuances related to survivorship. • Learners demonstrated increased identification of side effects. |

2b | |||||||

|

Piper et al. 2019 [51] Cost: NR Country: Australia |

Mixed methods approach |

Methods: participants completed pre- and post-placement surveys Sample Size: 90 PCPs (53 GPs; 15 practice nurses; 15 allied health professionals). Allied health professionals included: dietitians, exercise physiologists, occupational therapists, osteopaths, physiotherapists, podiatrists, psychologists, and speech pathologists |

PCPs | To increase PCP knowledge & confidence to deliver survivorship care. To increase PCP understanding of discipline-specific roles required for shared care & to enhance relationship between primary care and hospital-based professionals. | Mode: In-person placement program |

Observational placements at tertiary oncology departments. Curriculum: At a minimum, PCP learners were required to attend: • One multidisciplinary team meeting • One outpatient session focused on decision making and treatment planning for patients with new cancer diagnoses. • One outpatient session centred on survivorship, follow-up, or post treatment care. GPs attended up to three sessions (approx. 7 to 10 hours), NPs & AHPs attended two sessions (approximately 7 h). |

• 92% of learners reported increased knowledge and confidence in providing survivorship care. • 87% of learners reported opportunities to enhance clinical relationships with specialist teams. • 93% of learners reported that the program was relevant to their practice. |

2a, 2b |

|

• 99% of learners reported partially or entirely meeting their learning goals through program participation. • 31% of learners reported that the duration of placement program was not enough to facilitate achievement of learning goals. – • 81% of learners agreed that the program we well organised |

1 | |||||||

|

Risendal et al. 2020 [52] Cost: NR Program Name: iSURVIVE Program Country: USA |

Mixed methods design |

Methods: Triangulated Mixed Methods design consisting of a pre-, post-curriculum questionnaire (to assess changes in knowledge and awareness), and an interview (delivered a minimum of 1-year post education) to determine the impact and utility of the curriculum. Sample: 32 rural primary care practices (n=8 Federally Qualified Health Centre’s; n=17 Hospital Affiliate; n=8 private practice; n=1 university affiliate). 255 unique participants [n=67 clinician prescribers (MD, DO, PA, NP); n=104 patient interactive staff (medical assistant, nurse staff, patient navigator/facilitator, pharmacist, behavioural health care provider, and others who interact with patients during care encounters); n=17 other staff (administrator, front office medical records, billing). |

Rural primary care practice teams & unique participants who interact with patients | To produce short-term impacts (knowledge and awareness) as well as promote intention for behaviour change in survivorship care delivery in rural primary practice. |

Mode: Online & in-person, face-to-face. Framework/Theory: ‘Appreciative inquiry’ was a key strategy deployed in curriculum delivery. |

Cancer survivorship curriculum delivered as four in-person sessions. • Session 1 (2h): introduction of clinical scenarios (adult & childhood) & SCP. Identification of charts for review • Session 2 (90-min): assessment of functional & psychosocial status. Distress screening, survivorship focused medical history • Session 3 (90-min): lifestyle recommendations (focus on exercise/physical activity); risk-based surveillance; health maintenance with PCPs • Session 4 (2h): General review & review of changes made in practice (via interview) Program also included a supplementary series of 12 monthly webinars. Curriculum: based off content outlined by the IOM (i.e. long-term sequelae; statistics in health access, psychosocial concerns; QA, models of care; prevention; detection; rehabilitation; treatment of recurrence and secondary malignancies). |

Immediate post-program evaluation • Increase in percent of correct knowledge scores between baseline and post-program across all topics (25% vs 46%, p<0.001). |

2b |

|

Interview (approx. 12 months post-program) • Positive perspective and immediate changes: PCP learners found the training curriculum informative, educational, and useful in clinical practice. Curriculum increased empathy and awareness of cancer survivor needs. PCP learners reported increased comfort and thoroughness during tasks (e.g., taking patient history, asking questions) |

1, 2a | |||||||

|

• Practice change: Training created intention to make changes to survivorship care practice. Small changes up to immediate practice changes (e.g., more comprehensive history taking, ordering PET scan for patients). |

3, 4a | |||||||

|

Rushton et al. 2015 [53] Cost: NR Program Name: The Wellness Beyond Cancer Program (WBCP) Country: Canada |

Post-program evaluation only |

Methods: Survey sent to PCPs and patients 1 year-post referral to program. (5-point Likert scale; 1=strongly agree, 5=strongly disagree). Sample: 113 PCPs, 129 breast & colorectal patients |

PCPs and breast & colorectal patients. | Provide care to breast cancer and colorectal cancer patients, improve cancer program efficiency; and improve health provider knowledge of cancer survivor assessment and management. | Mode: In-person |

Patients from main hospital discharged and referred to the WBCP program. Patients are referred to one of 3 pathways; survivorship care provided by PCP only; shared care by a Wellness program NP with a PCP; care by primary oncologist with PCP shared care. Content: PCPs receive SCPs which contain: • Patient disease details • Treatment summary • Info on patient’s cancer team • Recommended follow-up surveillance • Outstanding self-identified needs |

PCP evaluation • Program was received positively by PCPs (care plan educational, transition of care process was clear). |

1 |

| • Program assisted in the coordination of patient care. PCPs comfortable in ordering follow-up tests. | 2a, 3 | |||||||

|

Patient evaluation • Patients found the wellness care plan useful. Most patients were satisfied with the program (satisfied with support received, care received; quality of provided information) |

4b | |||||||

|

*Schilling et al. 2016 [54] Cost: NR Country: Germany |

Post-test only |

Methods: Evaluation and knowledge test completed after program completion. Sample: GPs |

GPs | To increase GP knowledge and awareness of survivorship concepts | Mode: In-person face-to-face. |

6-hr training program. Curriculum: physical side effects and late complications after treatment; prevention and management of side effects, fatigue and self-management; CAM; management of chronic pain; recommendations for tertiary prevention; physical activity and nutrition; guidelines for follow-up. |

• All GP participants welcomed the program and found the training program useful for daily practice. • GPs requested further support in the format of defined SCPs and follow-up schedules. |

1 |

|

Schwartz et al. 2018 [55] Cost: NR Country: USA |

Pre-test, post-test |

Methods: pre- and post-clinic questionnaire on learner’s attitudes, knowledge, and/or skill level (5-likert scale – forced choice). Option for free text comments available. Sample: 34 paediatric resident physicians [14 PGY-1 (41%), 13 PGY-2 (38%), 7 PGY-3 (21%)] |

Paediatric Resident Physicians | To increase paediatric resident knowledge, clinical skills, comfort and attitude in providing survivorship care for childhood cancer survivors. |

Mode: Face-to-face, in person Framework: Kern’s Six-step Model (used to integrate curriculum into existing educational structure), Learning objectives formulated according to Bloom’s taxonomy |

Cancer survivorship curriculum integrated into UCLA’s existing outpatient continuity clinic curriculum. Curriculum delivered via small weekly group case-based learning (each clinic session followed the same case study). Clinic sessions aimed to enhance the following: knowledge (of short- and long-term morbidities, incidence of drug use and sexual behaviours, understanding of ethnicity and gender disparities); skills (of taking a medical history, managing pain disorders and neurocognitive deficits), and comfort in counselling patients and parents (on fertility, immunisations, long term effects of treatment, effects on family). Content: American Academy of Pediatrics Healthy Children, “Chronic Conditions”; IOM recommendations for survivorship training for health care providers; The Children’s Oncology Group, “Long-Term Follow-Up Guidelines for Survivors of Childhood, Adolescent, and Young Adult Cancers, content from UCLA’s Pediatric Residency Training Program. |

• Residents would recommend the program to other residency programs (M=3.24/5; SD=0.69). • Residents sought more fertility information, additional training in counselling and further cancer survivorship education opportunities. |

1 |

|

• Residents reported enhanced knowledge in general paediatrics (M=3.24/5; SD=0.65). • Residents reported significant increase in level of competence of childhood survivorship knowledge and clinical skills in each assessment item (p<0.05) except the ability to take a survivor’s medical history (p=0.06). |

2b | |||||||

| • Residents reported significant increase in level of comfort with counselling survivors and their families in all assessment items (p<0.05). | 2a | |||||||

|

*Smith et al. 2018 [56] Cost: NR Program Name: Cancer Survivorship for Primary Care Practitioners Program Link: https://www.viccompcancerctr.org/what-we-do/education-and-training/cancer-survivorship-for-pcps/ Country: Australia |

Paired test (pre-test, post-test) (Ongoing study) |

Methods: pre- and post-test survey. Sample: N/A (Ongoing study) launched to over 500 participants. |

PCPs and allied health professionals | Increase/enhance PCP knowledge and skills in transition of survivors from oncology into treatment shared care. | Mode: Web-based, online. | 4-week open online course consisting of seven program modules: (1) survivorship fundamentals; (2) communication and coordination of care; (3) supportive care; (4) surveillance; (5) long term and late effects; (6) new cancer therapies; (7) delivery method |

• Online course received high engagement. • Workshops were positively evaluated. |

1 |

| • Learners reported they were confident to apply key messages to practice. | 2a | |||||||

|

*Tan et al. 2016 [57] Cost: NR Country: USA |

Post-test only |

Methods: post-conference evaluation completed by participants Sample: 21 Filipino nurses (case management, intensive care, medical/surgical floor/research, primary care and one in oncology) with 21-40 years nursing experience. |

Nurses | To assess knowledge and retention of survivorship conference topics. | Mode: In-person conference |

Annual one-day nurse conference. Content: nutrition, genomics, neuropathic pain; survivorship issues; psychological/spiritual issues; targeted treatment & personalised cancer care. |

• Good immediate recall of topics. | 2b |

| • Topics considered actionable or pertinent to practice by nurse participants: cancer prevention through vaccination & screening (62%); pathogenesis of cancer (48%); novel biomarkers and targeted pill treatment instead of intravenous chemotherapy (71%); nutrition (10%); emotional and spiritual support (10%). | 1 |

Quality of the evidence

All studies were susceptible to bias due to the lack of comparison groups. The quality of most pre-test, post-test and post-test studies was rated poor, with one rating fair (see Supplementary File 5). In addition to the inherently high risk of repeat testing bias, observer bias, the Hawthorne effect, and attrition bias of these types of studies, most of these studies presented limited information about eligibility criteria, sample size calculation, loss to follow-up, fidelity of intervention delivery, and the definition and reliability of outcome measures. Of the two mixed-methods studies, one was of high methodological quality [52] and the other received a poor rating [44], presenting issues such as unspecified qualitative methodology, sampling strategy, and statistical methods (see Supplementary 5). Across all studies, outcome measures generally consisted of non-validated self-response measures, increasing risk of self-rater bias. Further, only eight [38–40, 42, 44, 48, 52, 55] of 21 studies included a statistical analysis of results and specified the magnitude of change.

Content and modality of cancer survivorship programs

Survivorship care components and content of each program are outlined in Table 2. Intended cancer survivorship content differed across education programs and included clinician education targeted towards the management of fear of cancer recurrence [38]; utilization of survivorship care plans (SCPs) [42, 53]; management of sexual complications in female cancer survivors [48]; survivorship management specifically for Hodgkin’s lymphoma, breast cancer and prostate cancer survivors [39], and cervical, breast, and colon cancer survivors [41]; childhood cancer survivors [43, 47, 55]; survivors undergoing immunotherapy [50]; and “general cancer survivorship” across all populations [40, 44–46, 49, 51, 52, 54, 56–58]. A variety of approaches to survivorship education were described across studies including self-directed online courses [39, 45, 47, 56], in-person presentations [38, 42, 58], workshops and training sessions [40, 44, 46, 48, 54, 55], placement and clinical rotation programs [41, 51, 58], a fellowship program [49], a referral program [53], a live webcast [50], a survivorship conference [57], an in-person workshop and online webinar [52], and an in-person seminar and online webinar series [43].

Table 2.

Survivorship care components of education programs

| Articles (surname, year, country) | Prevention and surveillance for recurrences and new cancers | Surveillance and management of physical effects | Surveillance and management of psychosocial effects | Surveillance and management of chronic medical conditions | Health promotion and Disease prevention | Clinical structure | Communication and decision-making | Care coordination | Patient/caregiver experience | Special populations (e.g., AYA, pediatrics) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Program described in full-text study | ||||||||||

| Berrett-Abebe et al., 2018 and 2019 [38] | * | * | * | * | ||||||

| Buriak et al., 2014 & 2015 [39] | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||||

| Donohue et al., 2019 [42] | * | * | * | * | ||||||

| Evans et al., 2016 [58] | * | |||||||||

| Fullbright et al, 2020 [43] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |

| Grant et al., 2012 [44] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |||

| Harvey et al, 2018 [45] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||

| Jacob et al., 2018 [46] | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||||

| Meachem et al., 2012 [47] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |

| Nolan et al., 2019 [49] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||

| Piper et al., 2019 [51] | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||||

| Rushton et al., 2015 | * | * | * | |||||||

| Risendal et al., 2020 [52] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |

| Schwartz et al., 2018 [55] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |||

| Program described in abstract | ||||||||||

| Chaput et al., 2018 [40] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |||

| Daly et al., 2016 [41] | * | * | * | * | * | |||||

| Merriam et al., 2018 [48] | * | * | * | * | * | |||||

| Perloff et al., 2019 NR [50] | ||||||||||

| Schilling et al., 2016 [55] | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||||

| Smith et al., 2018 [56] | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||||

| Tan et al., 2016 [57] | * | * | * | * | * | |||||

*Survivorship component explicitly reported.

Cancer survivorship program curricula

A range of sources and guidelines were used to inform survivorship education curricula and content. Eight [43–48, 52, 55] of 21 programs specified the utilization of at least one specific recognized guideline or framework to inform survivorship program content or curricula. These guidelines/frameworks included the Children’s Oncology Group Long-Term Follow-up Guidelines [43, 47, 55]; the Quality of Life Model for Cancer Survivors [44]; the American Cancer Society Clinical Care Guidelines [45]; the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Breast Cancer Survivorship Care Guidelines and ASCO Treatment Summary Survivorship Care Plan [46]; the Institute of Medicine (IOM) survivorship recommendations [52]; and the 5A’s communication framework [48]. One study [39] did not explicitly specify the foundation of curriculum content but described the utilization of videos from the IOM in their program and linked additional resources from the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), National Cancer Institute (NCI), the Physicians’ Desk Reference (PDR) and ASCO. Lecture content for one fellowship program was informed by the Commission on Cancer (COC), ASCO, and NCCN guidelines [49]. One study described the use of an interdisciplinary committee (incorporating cancer survivor representatives) along with literature, to inform their survivorship curriculum [53]. Two studies engaged clinical stakeholders in informing curricula [38, 50], but did not specify the engagement of cancer survivors. One study engaged a stakeholder group consisting of clinicians, community outreach, marketing, and business development staff in informing program curriculum content [41]. Seven studies did not specify what informed survivorship program content or curricula [40, 42, 51, 54, 56–58].

Teaching or learning frameworks and theories underpinning the survivorship programs

Eight [38–40, 43–45, 52, 55] of 21 survivorship education programs explicitly described the use of a teaching or learning framework or theory to guide program development or evaluation. Buriak and colleagues [39] used the Analysis, Design, Development, Implementation, and Evaluation (ADDIE) instructional systems process model and a revised version of Bloom’s taxonomy to design their educational program. The same authors also used Gagne’s “Nine Events of Instruction” and Mayer’s principles of multimedia modality to facilitate effective learning. Berrett-Abebe, Chaput, Harvey, and colleagues [38, 40, 45] described the use of Kirkpatrick’s Training Evaluation Framework. Of these three studies, Chaput and colleagues [40] utilized three levels of the framework (satisfaction, knowledge, and behavior) to develop the outcome measures of their education program, and the remaining two studies [38, 45] used the framework to guide program evaluation. Berrett-Abebe and colleagues [38] also described use of social cognitive theory to guide the development of their training program. Fulbright and colleagues [43] used adult learning theory in curriculum development (and in case-based examples). Grant and colleagues [44] described the utilization of adult learning principles and institutional change theory. Risendal and colleagues [52] utilized Boot Camp Translation methodology and appreciative inquiry to develop and implement their curriculum, while Schwartz and colleagues [55] used Kern’s six-step model to integrate their survivorship curriculum into an existing educational structure. The same study also used Bloom’s taxonomy to inform learning objectives. Thirteen studies [41, 42, 46–51, 53, 54, 56, 57] did not describe the use of a teaching or learning framework/theory.

Cancer survivorship program evaluation

Education program outcomes are reported in Table 1 as informed by the Kirkpatrick framework. Program outcomes and final interpretations were the same after removal of abstract studies from analysis; thus, outcomes described in full-text papers and conference abstracts were appropriate to be combined during narrative synthesis.

Kirkpatrick level 1—reaction to program

Sixteen studies [38–40, 42–44, 46, 47, 49, 51–55, 57, 58] evaluated level 1 outcomes. Views on learning experience were mostly measured using a Likert scale (from strongly disagree to strongly agree) with certain studies also incorporating open text [42, 44, 55] and interview feedback [44, 47, 52, 53, 58]. Across all 16 survivorship programs, learner experience and program content were generally reported to be favorable. Outcomes reported included program usefulness and relevance to practice [38, 47, 51, 52, 54, 55, 57]; satisfaction with program design and organization [39, 51]; satisfaction with program content and delivery [39, 40, 43, 44, 49, 51, 53, 58]; recommendations for program improvement [42, 58]; and the recommendation of the program to others [38, 46, 55]. Critical reports on learning experience included insufficient program duration to facilitate the achievement of learning goals [51, 58]; the request for further training in survivorship counseling, additional onco-fertility information, and survivorship training opportunities [55]; limited exposure to long-term follow-up care and the request for more structured education and quality improvement activities [58]; and additional support in acquiring well-defined SCPs and follow-up schedules [54].

Kirkpatrick level 2—learning

Thirteen studies [38, 40, 44–48, 51–53, 55, 56, 58] reported positive level 2a outcomes, including increased awareness of cancer survivor needs [47, 52, 58] and increased confidence [38, 40, 45, 51, 56, 58], self-efficacy [38], and comfort [44, 46, 48, 52, 53, 55] in providing cancer survivorship care. Most outcomes were measured using self-reported questionnaires with three studies utilizing interviews [44, 52, 58]. Fourteen studies [38–40, 42, 43, 45, 46, 49–52, 55, 57, 58] evaluated level 2b outcomes assessing improvements in knowledge, competency [55], and the recall of topics [57]. Eleven of the fourteen studies evaluated knowledge outcomes using pre-tests and post-tests that were delivered immediately after program cessation (immediate post-test) (e.g. questionnaires, surveys); two studies used a pre-test and immediate post-test followed by a 3 month [40] or 12 month [52] delayed post-test; and one study utilized feedback from fellowship program facilitators to determine that learners had sufficient increase in cancer survivorship knowledge [49].

Kirkpatrick level 3—transfer of learning/behavior change

Nine studies [38, 39, 41, 43, 44, 48, 52, 53, 58] evaluated PCP learner behavior change as a result of survivorship education. Of the eight studies, only two [44, 53] evaluated the transfer of cancer survivorship learning to clinical practice (e.g., increased PCP confidence ordering follow-up tests; self-reported behavior change due to education intervention), both of which also provided follow-up evaluation 12 months post-program commencement. The remaining six studies [38, 39, 41, 43, 48, 52, 58] only measured outcomes immediately post-program; and thus, only evaluated the intention of PCPs to change practice (e.g., implement follow-up guidelines, improve referrals, provision of routine screening, etc.).

Kirkpatrick level 4—program impact/results

Two studies evaluated level 4a outcomes assessing survivorship changes in organizational practice [41, 44]. Daly and colleagues [41] reported that one PCP practice referred three patients onto lung surveillance and screening because of PCP education sessions within their program. Nearly all (98.1%) participants in Grant and colleagues study [44] reported that program participation resulted in the uptake of cancer survivorship care at their respective institutions, though specific detail on changes were not provided. Institutional assessments and surveys completed 18-month post-program commencement found significant change and improvement in organization vision and management standards; practice standards; psychosocial, emotional, and social care; communication standards; quality improvement standards; patient and family education; and community network partnerships. However, despite reporting statistical significance, the specific magnitude of change was unclear.

Three studies [50, 52, 53] assessed level 4b outcomes which indicate survivorship program impact at the patient level. Risendal and colleagues’ mixed-methods study [52] found that training sessions led to varied survivorship care changes across participating rural practices, including more comprehensive history taking, improved referral of patient surveillance scans, and other unspecified immediate changes. Rushton and colleagues [53] reported that 1 year after initial transfer to their PCP cancer survivorship referral program, patients were satisfied with the overall support, care, and quality of information received and were more knowledgeable about treatment received, potential late effects, and the latent symptoms to report to their primary care providers. Perloff and colleagues [50] estimated that 590 patients per month were “impacted” by their PCP survivorship webinar; however, it was not specified how authors measured this outcome or whether the impact was positive or negative. Notably, all three studies [50, 52, 53] did not quantify the magnitude of change in outcomes reported.

Discussion

Primary care providers are integral in the provision of acute and follow-up care to cancer survivors, yet many PCPs report being unprepared to offer adequate cancer survivorship care. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review evaluating cancer survivorship education programs targeted towards PCPs in published literature.

Cancer survivorship program content

Survivorship program content and aims varied across studies with some programs focusing on specific symptoms (e.g., fear of cancer recurrence) or cancer groups (e.g., neurological cancers) and other programs providing a more complete overview of survivorship care. In an ideal circumstance, PCPs should have access to high quality programs that provide a broad overview of survivorship, as well as those that focus on a specialized topic such as management of specific symptoms. While it is recommended that survivorship education programs for PCPs address all core survivorship competencies [9, 33] (e.g., surveillance for recurrence and second malignancies, management of late and long-term effects, management of psychosocial wellbeing, and health promotion), it is essential that the specific programs are “pitched” at the right level for the targeted PCPs. Risendal and colleagues [52] raised the possibility that the curriculum developed for their PCP cancer survivorship training program can be too broad and that important learning points may not have been emphasized strongly enough; as despite improving from baseline, PCP learners still recorded “poor” test results. In contrast, overcomplexity can be a key barrier to learning uptake through hindering information recall and limiting the transfer of learnings to practice [60]. Therefore, a one-size-fits-all approach is likely inappropriate. To address this issue, an evidence-based approach to establish the minimum cancer survivorship educational requirements needed for PCPs is crucial. Moreover, the ASCO Core Curriculum for Cancer Survivorship Education [33] could potentially provide a framework which could be contextualized to the scope and practice of PCPs. Additionally, comprehensive survivorship education programs should be made adaptable to the local context and learning needs of individual PCPs (e.g., determination of prior knowledge, adaptation of content to learning characteristics, adaptive navigation, altering the sequence of program content) to improve learning outcomes [61, 62].

In the 21 included studies, only 14 studies described the sources used to inform survivorship content or curricula. Of the 14 studies, only eight studies specified the use of recognized survivorship guidelines. To ensure PCPs are competent in survivorship care, it is paramount that education programs are based on current, quality evidence. While we acknowledge that information on content development is often omitted from publication, study authors should endeavor to highlight education content is evidenced-based, to increase learner confidence in program quality.

Teaching and learning approaches

The use of learning and teaching theories across all twenty-one survivorship programs were minimal, with only eight studies describing the use of a specific learning framework to guide program development. The ultimate aim of survivorship education programs is to facilitate clinical behavior change that will impact the care of cancer survivors [63, 64]. Greater attention is needed to incorporate behavior learning frameworks and theories into survivorship programs to promote tangible and sustainable changes in clinician practice [7, 65].

Our systematic review also identified that cancer survivorship programs can be delivered in a variety of modalities (fellowship programs, online modules, didactic lectures, presentation, workshops, etc.) depending on needs and context—all resulting in perceived positive learning outcomes. While this review does not allow the comparison of the efficacy of different learning modalities, the choice of delivery mode for any education program can directly impact learning outcomes and knowledge retention. Further investigation of the impact of various learning and teaching approaches in the context of cancer survivorship education is required [60, 61]. For example, in a recent review on cancer education in medical schools [66], education programs which promoted interactive educational experiences such as clinical simulation, role play, summer programs, and interaction with multidisciplinary teams were highly effective and had the most positive impact on learners, while intensive block programs, lectures, small group discussions, and computer or web-based education were not as effective [66]. Additionally, when compared to traditional learning, web-based education programs have been shown to have little to no difference on health professionals’ knowledge and behaviors or outcomes of patients [67].

Although interactive survivorship education programs may be ideal, lack of clinician time has been highlighted as a significant barrier to PCP delivery of cancer survivorship care [14, 68], with providers indicating a preference for online programs [69]. Another consideration is the rapid development and innovation in learning technology and access limitations as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic [70]. Interestingly, twelve survivorship education programs in our review were delivered over 1 day or more with reported learner satisfaction and positive feedback—suggesting that PCPs are also willing to dedicate ample time to survivorship learning. As the current literature in this area does not allow evaluation of the most optimal mode of delivery, future research should be conducted to identify the optimal and most appropriate modality depending on needs, context, and setting to ensure practical consideration are accounted for, content is tailored to the appropriate primary care audience, and that positive learning outcomes are amplified. In particular, survivorship program developers seeking to introduce additional modalities to existing programs (particularly in residency programs) should regularly measure program learning outcomes through education assessments (at a minimum pre- and post-education), differentiate assessment results by modality, and then examine any differences in performance [71].

Cancer survivorship program outcomes

Learning outcomes (e.g., PCP satisfaction, transfer of behavior change, knowledge, confidence) across all 21 programs were generally reported to favorable and beneficial to PCPs. While promising, it should be noted that most studies only assessed outcomes immediately after program completion, meaning the long-term impact of survivorship education on clinical practice was not evaluated. For instance, although nine of 21 programs reported that PCPs had increased willingness and intent to change practice, only two studies actually evaluated whether PCP learners had implemented the skills learned during survivorship education into practice. Similarly, few studies evaluated the impact of survivorship education programs on organizational practice (n=3) and patient outcomes (n=2); and those that did, did not quantify or provide evidence of these results. These deficiencies highlight the need for more rigorous and robust study designs that incorporate adequate follow-up to better identify the long-term impact of survivorship programs on survivorship care delivery and PCP behavioral change.

Limitations

Several limitations of this systematic review exist. First, all included studies were published in English, and most included cancer survivorship programs were developed in the USA. Therefore, such programs may not be applicable for other use in other countries especially countries where the culture, language, and health systems are vastly different. Second, while it is common in the education literature, the high risk of bias across the included studies (due to self-reporting, lack of follow-up testing, study design, etc.) suggests that caution should be taken when interpreting the findings from these studies. Nevertheless, this review provides some direction for future research in this area. Third, only the published literature was searched for this review, and hence, we did not include many educational programs, both in-person and online that have been developed and conducted over the past decade (e.g., ASCO Continuing Medical Education). Although this approach limits the inclusion of such programs, the lack of detailed evaluation data available for these programs in a published report precludes us from addressing the aim of this review.

Future implications and conclusions

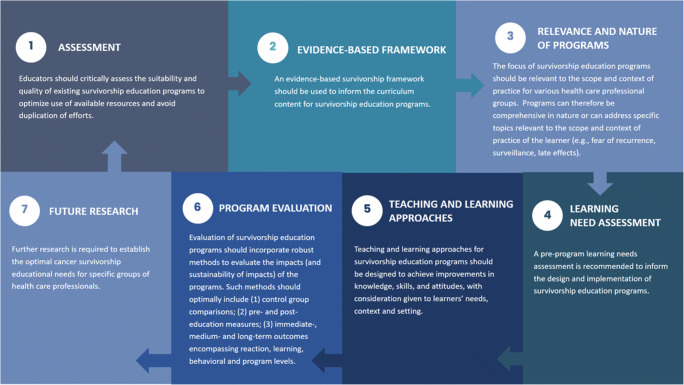

A plethora of cancer survivorship education programs targeted towards PCPs currently exist; however, we could only identify 21 studies that evaluated education outcomes in the published literature in this review. In Fig. 2, we propose the following recommendations for developing and evaluating survivorship education program. Our review highlights significant limitations of existing survivorship programs; therefore, we suggest that survivorship education program content should be based on evidence-based survivorship frameworks and incorporate evidence-based learning and teaching approaches. Further, survivorship program content should be tailored to PCPs through the establishment of minimum educational requirements to increase the utility and relevance of survivorship education to primary care practice. Additionally, our literature search highlighted extensive duplication of content across PCP survivorship education programs. While acknowledging the necessity of contextual considerations (e.g., profit, prestige, varying health systems), we posit that education developers should first identify other appropriate education programs before “re-inventing the wheel” and duplicating efforts. Further collaborative efforts should be dedicated to the development of studies which incorporate robust evaluations of survivorship programs and measure the impact (and sustainability of impacts) of education on survivorship care delivery and patient outcomes.

Fig. 2.

Recommendations for developing and evaluating survivorship education program

Supplementary information

(DOCX 22 kb)

(DOCX 14 kb)

(DOCX 15 kb)

(DOCX 15 kb)

(DOCX 55 kb)

Author contribution

All authors made substantial contributions to the interpretation of data; drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and final approval of the version to be submitted.

Funding

RJC receives salary support from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) through an NHMRC Investigator Grant (APP1194051)

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Raymond J. Chan and Oluwaseyifunmi Andi Agbejule are co-first authors.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Ervik M, Colombet M, Mery L, Pineros M. Global cancer observatory: cancer today. 2019.

- 2.Bray F, Jemal A, Grey N, Ferlay J, Forman D. Global cancer transitions according to the Human Development Index (2008-2030): a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(8):790–801. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70211-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]