Abstract

Introduction

During the COVID-19 pandemic period, the structure of the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) activities changed fast. It was observed that the mental and physical health of the frontline workers reached levels of extreme clinical and psychological concern.

Objective

Understand the impact that COVID-19 is having on the front-line clinical team in the ICU environment, as well as reveal what proposals are being made to mitigate the clinical and psychological impacts that this group experiences.

Method

A systematic review was made following the PRISMA protocol (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis). We included any type of study on health workers during the COVID-19 pandemic, with results about their mental health. We were, therefore, interested in quantitative studies examining the prevalence of problems and effects of interventions, as well as qualitative studies examining experiences. We had no restrictions related to study design, methodological quality or language.

Results

Twenty-one studies reported on the urgent need for interventions to prevent or reduce mental health problems caused by COVID-19 among health professionals in ICU. Eleven studies demonstrated possibilities for interventions involving organizational adjustments in the ICU, particularly linked to emotional conflicts in the fight against COVID-19.

Conclusion

The disproportion between the need for technological supplies of intensive care medicine and their scarcity promotes, among many factors, high rates of psychological distress. Anxiety, irritability, insomnia, fear and anguish were observed during the pandemic, probably related to extremely high workloads and the lack of personal protective equipment.

Keywords: COVID-19, Intensive care unit (ICU), Health workers in ICU, Experiences and perceptions from health professionals in ICU, Clinical and psychological aspects

1. Introduction

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19), in which the etiologic agent is the SARS-CoV-2 virus, belonging to the b-coronavirus family, has been classified as a pandemic since March 11, 2020, by the World Health Organization (WHO). This new pathology causes severe respiratory problems, leading the infected person, often, to need support in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU). [Dost et al., 2020; Raurell-Torredà et al., 2020].

Due to the high virulence and infectivity, the disease in question soon made victims in figures so high that the number of ICU beds was depleting and causing chaos both in the scientific team and in the public [Zaka et al., 2020]. On the other hand, one of the measures found to try to alleviate this situation was the creation of field hospitals, as well as the relocation of ICUs specialized in certain pathologies for the care of individuals with COVID-19 complications. Same examples are the Cardiology Unit of Bergamo, in which 60% of its beds were occupied by COVID-19 positive patients [Senni, 2020], and the reuse of the 14 beds of the pediatric ICU of the General Children's Hospital in Massachusetts for adults [Yager et al., 2020].

Still, the level of stress is increasing in the front-line team, which includes doctors, nurses, and physiotherapists from the ICU. We are living in a period of war, in which suffering and death shine, both for those who live and for those who die, resulting from the disproportion between the needs of the sick ones and the available resources [Romanò, 2020]. From this point of view, stress is defined as the organic, psychological, and social response to harmful developers that the individual experiences [Wu et al., 2020].

In this circumstance, it is noted that the health team is guided by physical and emotional resistance to face life and death situations, even if their integrity is at risk [Santarone et al., 2020]. Such commitment, especially from doctors, is remoted from the Hammurabi Code and the Hippocratic Oath. Nowadays, the main relationship of this group with society is based on the social contract, putting in question the expectations of the people for care, competence, altruism, integrity, responsibility, and the generation of the common good by the doctor. Given that, the doctor expects trust, autonomy, social recognition, self-regulation, and financial support of an own health system for the full exercise of his activity. However, the COVID-19 pandemic puts the contract at the extreme by asking us: do the risks experienced by these professionals do not have a limit? [Ferreira et al., 2020].

In this context, it is necessary to remember that the history of humanity is marked by big outbreaks and epidemics as deadly as the current COVID-19, with devastating results on the psychic-organic health of the workers involved. For example, in 2003, in China and Canada, SARS-CoV-1 generated, in at least 10% of front-line professionals, an increase in the level of stress, with mental problems lasting up to 3 years after the trauma, with a focus on the sum of symptoms (dizziness, headache, breathing difficulties), burnout, anxiety, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), fear of future, outbreak, and, especially, depression [El-Hage et al., 2020; Zaka et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020; Hou et al., 2020; Blake et al., 2020].

Another relevant infectious and contagious disease was the Influenza A (H1N1) epidemic, in 2009. Such illness had psychiatric consequences in the health team, as, for example, the increase in anxiety, feelings of anguish, and addictions (nicotine and alcohol) [Blake et al., 2020; El-Hage et al., 2020]. Recently, in 2013–2016, Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia experienced an outbreak of the Ebola virus, causing significant psychological symptoms for health professionals, such as depression, paranoid ideation, fear of death or having another similar experience, and PTSD. Such consequences had a relevant impact on the quality of life and work of these individuals [Hou et al., 2020; Zaka et al., 2020; Maben and Bridges, 2020].

Thus, it is clear that the mental and physical health of front-line workers has been already pushed to the limit in past situations. Given the normal time of society, it is known that at least 50% of the doctors fight against burnout or emotional exhaustion due to the stress experienced at work [Santarone et al., 2020]. Consequently, it is observed that the professionals from health team in the ICU environment brings with them scars and marks of personal battles that they fight daily with each other, and the accomplishment of their craft in the fight against COVID-19. [Blake et al., 2020].

Therefore, the objective of this work is to understand the impact that COVID-19 is having on the front-line clinical team in the ICU environment, as well as to reveal which proposals are being made to mitigate the clinical and psychological impacts that this group experiences.

We elaborated the PICO strategy so that we could reach the guiding research question, being P (Patient or Problem): Frontline Clinical Team in the ICU environment; I (Intervention): Impact of Covid-19; C (Control or Comparison): Frontline Clinical Team in an ICU environment that are suffering clinical and psychological impacts to Covid-19; O (Outcome): Proposals that are being elaborated at the clinical and psychological level in facing Covid 19.

Based on this assumption, the following research question was mapped: What are the impacts that Covid-19 is providing to frontline teams in an ICU environment? It takes into account the proposals that are being elaborated to face the clinical and psychological impacts of these professionals.

2. Method

A systematic revision was made, following the PRISMA protocol (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis), in the period from January 2020 to January 2021.

2.1. Inclusion criteria

We included any type of study on health care workers in ICU during the COVID-19 pandemic, with results related to their mental health. We were, therefore, interested in quantitative studies examining problems and effects of interventions, as well as qualitative studies examining experiences. We had no restrictions related to study design, methodological quality, or language. The language problem was solved through a reasonable degree of comparability, which allowed us to systematically analyze the selected evidence, its critical evaluation process, and its success in including relevant studies in other languages.

We classify assessments according to their level of inclusion of studies in other languages. Reviews that excluded non-English studies with an explicit justification in the research question or research objectives were categorized as justified by R1 (that is, justified in English), while those that excluded non-English studies without justification were categorized as restricted to RR1 (that is, languages that are not restricted to English). Reviews that did not explicitly exclude studies that were not in English were categorized as RR1-open, unless they successively included studies that were not in English, in which case they were RR1-inclusive. Finally, revisions that did not declare language criteria were considered to be RR1-open.

2.2. Literature research and selection of articles

To search for studies, the following databases were used: Pubmed, Scopus, ScienceDirect, Web of Science and Embase. We identified categorized references for the population “Intensive Care Units”, and for the topic “Health Personnel” and Health Care Workers” and “Mental Health” and “Mental Disorders” and “Psychiatry” and “Coranavirus” and “Coronavirus Infection”. Besides, we identified references by searching (title/abstract) in the database, using the keywords: psych *, stress *, ans *, depr *, mental *, sleep, worry, and somatic symptoms. We selected all references identified specifically for the inclusion criteria for this systematic review.

2.3. Data extraction and methodological quality assessment

We have developed a data extraction form to collect data on participants and exposure to COVID-19, intervention, if relevant, and results related to mental health. We extracted data on mental health problems, as well as related ones (that is, risk/resilience factors); strategies implemented or accessed by health professionals with the objective to treat their own mental health; perceived need and preferences related to interventions designed to prevent or reduce negative mental health consequences; and experience and understanding of the healthy mindset and related interventions.

One researcher (FCTS) extracted data and another verified the extraction. Two researchers (CPB and FCTS) independently assessed the methodological quality of systematic reviews using the AMSTAR tool (Shea et al., 2017) and qualitative studies using the CASP checklist (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme – CASP, 2018). A researcher (FT) assessed the quality of cross-sectional studies using the JBI Prevalence or the JBI Cross-sectional analytical checklist and longitudinal studies using the JBI Cohort checklist (Johanna Briggs Institute 2020).

2.4. Data presentation and analysis

We summarized the results narratively. We described interventions and outcomes based on the information provided in the studies. When studies showed mental health results in numbers without numbers, we extracted them using an online software (https://apps.automeris.io/wpd/). We decided not to perform a quantitative analysis of summaries of the associations between the various correlates and health factors, due to a combination of heterogeneity in the measures and lack of control groups, and an embraced lack of descriptions necessary to confirm sufficient homogeneity. We rated the certainty of the evidence using the GRADE approach – (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluations (Guyatt et al., 2011).

3. Results

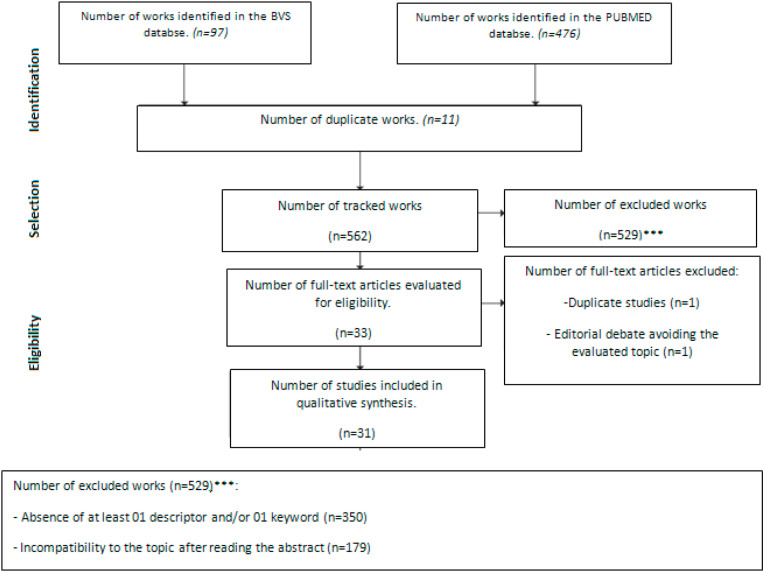

Altogether, 573 evidences were found. With the subsequent application of the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 31 studies were included for qualitative foundations. Fig. 1 and Table 1 summarize the main methodological characteristics for inclusion or exclusion of the studies.

Fig. 1.

Prisma 2009 flow diagram.

Table 1.

Information from selected studies.

| AUTHOR/YEAR | TITLE | INDEXED JOURNAL | MAIN FOUNDED TOPICS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dost et al. (2020) | Attitudes Of Anesthesiology Specialists And Residents Toward Patients Infected With The Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19): A National Survey Study | Surg. Infect. (Larchmt) | Anesthesiology specialists and residents should be protected during the performance of procedures with exposure to aerosols, associated with the incorporation of guidelines and fluxograms assisting in the approaches addressed, such as maintenance in ventilatory support; the promotion of courses aimed at technical improvement in orotracheal intubation to guarantee the safety of professionals and the patient, as well as reducing panic to health care team, which causes anxiety and psychological distress. |

| Raurell-Torredà et al. (2020) | Reflexiones Derivadas De La Pandemia COVID-19 | Enferm. Intensiva | Recommendations for the correct handling of PPE and measures to reduce the contagion of the nursing staff during the management of patients are described, such as how to keep a short time during the performance of invasive measures and with exposure material that can be potentially contaminating. It is also recognized as an error faced by the Spanish health system during the pandemic the failure to recognize the medical-surgeon specialty of nurses in intensive care, the shortage of PPE, and the work overload faced by active nurses. |

| Zaka et al. (2020) | COVID-19 Pandemic As A Watershed Moment: A Call For Systematic Psychological Health Care For Frontline Medical Staff |

Journal Health Psychology | Front-line professionals express a high risk of developing burnout, psychological suffering, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder, among other psychological traumas, because of the exhaustive routine in which they are experiencing, and it is necessary to carry out personal-psychological monitoring, directed to the demands of each subject and in the long term to avoid or mitigate these impacts on the social life of this group. |

| Senni (2020) | COVID-19 experience in Bergamo, Italy | European Heart Journal | Doctors have been experiencing a lot of stress' situations in which the maintenance of the safety of these workers is made a priority, with the adequate supply of personal safety materials, the adjustment of the hospital organization for the care of positive COVID-19 patients, changing the way of screening these patients, and the acquisition of telemedicine in the care, and monitoring of cardiac patients who were managed in the service |

| Yager et al. (2020) | Repurposing a Pediatric ICU for Adults | The New England Journal Of Medicine | The modification of the care provided by the pediatric ICU team to approach COVID-19 adult patients was seen as a great challenge, with gaps in the technical knowledge for approaching new patients. This situation was remedied by the acquisition of therapeutic measures directed at these patients and, mainly, by the preservation of the constitution of the ICU team, which was fundamental for the success in the rapid transition and for maintaining the team's morale. |

| Romanò (2020) | Fra cure intensive e cure palliative ai tempi di CoViD-19 | Recenti Progressi In Medicina | The disproportion in the requirement and availability of ventilators and ICU beds is causing anguish in the medical team. The change in the way the patient is selected and admitted to the ICU in this pandemic moment is the best way to mitigate and try to adapt the work performed to the demand. Clinical criteria such as clinical severity, presence of comorbidities, age, cognitive and functional status, and the presence of organ failure are parameters evaluated in association with ethical aspects such as equity, equality, and distributive justice. In this sense, patients who do not meet these criteria and reveal a poor prognosis should be submitted to the best palliative treatment, as well as maintaining psychological support to the families of these victims and workers to avoid psychological problems such as PTSD. |

| Wu et al. (2020) | Psychological stress of medical staffs during outbreak of COVID-19 and adjustment strategy | Journal of medical virology | Comparing the level of psychological stress between 2110 medical teams and 2158 university students across Chinese territory, Wuhan health professionals demonstrated higher levels of stress compared to workers in other provinces and students. A higher score was highlighted for aspects such as thinking of being sick or in constant danger, unsatisfactory sleep, concern for the health of family members, need for psychological counseling, and less hope for the victory of the situation experienced. |

| Santarone et al. (2020) | Preserving mental health and resilience in frontline healthcare workers during COVID-19 | The American journal of emergency medicine | Experiencing a high number of deaths of friends and patients leads to mental exhaustion, which is associated with the social self-isolation of the family and which contributes negatively to the psychological health of front-line workers. This situation creates a risk for the development of depression and suicide. In this sense, attitudes such as reducing the workload and providing individualized psychological support and conditions for rest to mitigate these impacts are imperative. |

| Ferreira et al. (2020) | Profissionalismo Médico e o Contrato Social: Reflexões acerca da Pandemia de COVID-19 | Acta Med Port | It is believed to be the duty of the doctor to be ready in times of crisis. This idea is consolidated through the social contract, which governs the rights and duties of the doctor-society binomial. Thus, support and social recognition are relevant characteristics to stimulate and preserve the resilience of these professionals, enabling the full performance of their work activities, even when their integrity is at risk. |

| El-Hage et al. (2020) |

El-Hage et al. (2020) Les professionnels de santé face à la pandémie de la maladie à coronavirus (COVID-19): quels risques pour leur santé mentale ? |

Encephale | The identification of factors linked to the pathogen, such as high virulence and little scientific knowledge about it, conditions associated with work dynamics, such as the scarcity of PPE and technologies for the management of affected patients, as well as the psychological implications in which professionals of the front-line are likely to develop, such as depression, PTSD, suicide, anxiety, and others, are relevant to dictate the measures that should be taken to help this group in facing the pandemic and to enable the planning and the construction of models of primary and secondary prevention of psychological damage in health workers in the face of future situations of crises. |

| Hou et al. (2020) | Social support and mental health among health care workers during Coronavirus Disease 2019 outbreak: A moderated mediation model | PloS one | Resilience is seen as an individual protective factor and as a mediator in the relationship between social support and mental well-being of health workers. Besides, among the 1472 professionals interviewed, there were a greater dependence and correlation between resilience and psychological integrity in young people compared to middle-aged workers, who demonstrated that social recognition and experience acquired in other epidemics are relevant factors to face the COVID-19 pandemic. |

| Blake et al. (2020) | Mitigating the Psychological Impact of COVID-19 on Healthcare Workers: A Digital Learning Package | International journal of environmental research and public health | The development of a digital package aimed at the immediate needs of the health team and their families during the pandemic period, containing knowledge about communication between leaders and staff, social support, self-care strategies, emotion management, and provision of individual psychological support was well evaluated by users and it was indicated as a model for other environments owing to the benefits created, as practicality and low cost. |

| Maben and Bridges (2020) | Covid-19: Supporting nurses' psychological and mental health | Journal of clinical nursing | Nurses are considered the most negatively affected group in their physical, social, and mental aspects in the face of the pandemic, given their close contact with patients and the development of risk tasks, such as changing the position and collecting secretion from the airways of patients. . Thus, despite the importance of social support, the premises required by nurses must be recognized and changed by their superiors, such as the provision of places for rest, the reduction of work shifts, the guarantee of PPE, and the preservation of the constitution of the team to guarantee the dialogue between its members, the trust, and to reinforce the resilience. |

| Greenberg et al. (2020) | Managing mental health challenges faced by healthcare workers during covid-19 pandemic | BMJ (Clinical research ed.) | Health professionals are more susceptible to moral injury and the development of mental problems due to the actions taken against COVID-19. In this context, health managers must act for the well-being of the team, for example, being direct and sincere to maintain a bond of trust and to reduce the tensions of the health care team, being open and listening to the needs identified by them, and promoting long-term psychological monitoring of professionals, to identify and treat such psychological problems. Employees who maintain a good relationship with each other are able to face this moment in a better way, and it is important to the maintenance of the team. |

| Piccinni et al. (2020) | Considerazioni etiche, deontologiche e giuridiche sul Documento SIAARTI “Raccomandazioni de ética clinica per I'ammissone a trattamenti intensivi e per la loro sospensione, in condizioni eccezionali di squilibrio tra necessità e risorse disponibili” | Recenti Prog Med | Due to the imbalance between the need and availability of resources in ICU, the document SIAARTI guides the medical team to the conducts addressed, relieving them of the responsibility regarding the reallocation of resources, and exposing to society which criteria is evaluated in these decisions, such as the age of the patient, his comorbidities and current prognosis. This allows the current medical conduct to be considered in the light of ethics and justice that focus on the possibility of saving the biggest number of patients who present clinical conditions for this, given the scarcity of materials and high demand experienced today. |

| Shen et al. (2020) | Psychological stress of ICU nurses in the time of COVID-19 | Critical care (London, England) | Because of the heavy workload, the fatigue, the disagreements with family members of patients, and the social discrimination due to contact with Sars-CoV-2 carriers, nurses, especially the youngest, are more vulnerable to depression, anxiety, suicidal thoughts, and low income at work. To change this reality, psychological interventions, stimulation to express feelings, familiarization with some procedures, encouragement to social support, creation of online groups to debate behaviors, and adaptation of working hours interspersed with moments of leisure, are attitudes consistent in promoting mental well-being. |

| Shah et al. (2020) | How Essential Is to Focus on Physician's Health and Burnout in Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic? | Cureus | Naturally, doctors are the professionals with the highest Burnout rates, and COVID-19 is increasing the feeling of exhaustion and mental problems, such as anxiety, in this group. Thus, the provision of subsidies to rest, to study, and to protect the health of doctors is essential, associated with the improvement in the screening of patients, the acquisition of updated guidelines orienting about conducts, and the new members to compose the medical team, as well as the promotion of the telemedicine, the telepsychiatry, and the support to resident physicians are ways to overcome the adversities experienced in this pandemic. |

| Rana et al. (2020) | Mental health of medical workers in Pakistan during the pandemic COVID-19 outbreak | Asian journal of psychiatry | Fears, anxieties, panic attacks, social stigmatization, depressive tendencies, and sleep problems are some manifestations that Pakistani doctors demonstrate and can last in the short as well as the long term. Thus, to appease these negative conditions in the short term, and to promote mental quality, hospitals have modified the shift system, offering accommodation conditions and psychological counseling, while ways of screening these professionals are implemented for a long-term approach supported by a specialized health mental team. |

| Pappa et al. (2020) | Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis | Brain, behavior, and immunity | After the start of the pandemic, the prevalence of anxiety in front-line workers is around 23.2%, while depression is 22.8%, and insomnia is 38.9%. Besides, it is observed that the subgroup of female nurses is the most affected when compared to men and the medical staff. In this sense, is ratified the importance of promoting actions aimed at preserving the physical and mental health of health care team. |

| Zerbo et al. (2020) | The medico-legal implications in medical malpractice claims during Covid-19 pandemic: Increase or trend reversal? | Medico-Legal Journal | The difficulty faced in current public health encompasses structural issues, knowledge about the activity and manifestations of the coronavirus, shortage of PPE, low experience of the team in the management of the clinical conditions that COVID-19 causes, and lack of ICU supplies for all patients. In this way, some medical practices considered neglectful, such as the reallocation of resources to save those patients with a better clinical picture at the expense of the others, are reviewed and must be adapted to the crisis reality experienced. At this moment, it is not up to judge medical conduct based on a non-pandemic situation. |

| Walton et al. (2020) | Mental health care for medical staff and affiliated healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic | European heart journal. Acute cardiovascular care, | Acute stress reactions, moral injury, and PTSD are some characteristics that the front-line team can reveal at this time of pandemic. However, these manifestations should be approached with care and attention, and should not be considered diseases because they are typical attitudes of those who face a crisis. In this sense, promoting resilience and addressing the team's requirements, through open dialogue with health managers, is essential to overcome these impacts today; associated with the creation of psychological support and screening during and after a pandemic to remedy the persistence of psychological problems reported by these workers. |

| Mukhtar (2020) | Mental health and emotional impact of COVID-19: Applying Health Belief Model for medical staff to general public of Pakistan | Brain, behavior, and immunity | The belief model developed in Pakistan aims to promote and increase the resilience of the health team, allowing them to face the adverse conditions of the new routine while the individual has the autonomy to perceive the conditions that can cause him mental suffering, to formulate ways to express their emotions and to create tactics to overcome the obstacles found. |

| Raurell-Torredà (2020) | Management of icu nursing teams during the covid-19 pandemic. Gestión de los equipos de enfermería de uci durante la pandemia covid-19 | Enfermeria intensiva | The disproportion in the number of patients seen during the pandemic and the small number of nurses is one of the main conditions that mark the exhaustion of these professionals. Thus, a new dynamic must be carried out to equalize the number of patients to the number of nurses, as well as the hiring of physiotherapists, specialized in intensive care, to reduce the number of tasks performed by nurses. |

| Rubio et al. (2020) | Recomendaciones éticas para la toma de decisiones difíciles en las unidades de cuidados intensivos ante la situación excepcional de crisis por la pandemia por COVID-19: revisión rápida y consenso de expertos | Med Intensiva | The allocation of resources or the prioritization of treatment in ICUs becomes a crucial element, and it is relevant to have an ethical reference structure in order to be able to make the necessary clinical decisions. Therefore, algorithms with norms are formulated to improve organizational conditions, availability of inputs, characteristics and health status of the patients approached and ethical decisions made; such as the formulation of contingency plans, holistic analysis of the patient, considering not only biological age, and actions based on the principle of distributive justice and proportionality. |

| Cai et al. (2020) | A cross-sectional study on mental health among health care workers during the outbreak of Corona Virus Disease (2019 | Asian journal of psychiatry | Front-line health care professionals are experiencing a high tendency to a psychological abnormality with a focus on interpersonal sensitivity and photic anxiety. Among the 1521 health professionals approached, it is noticed that such impacts are more common in the ones with less training and professional experience, and so being more dependent on the maintaining of resilience and the social support, as assistants in mental well-being. |

| Lian et al., 2020 | Screening for Chinese medical staff mental health by SDS and SAS during the outbreak of COVID-19 | Journal of psychosomatic research | The use of self-assessment scales is a practical and low-cost method to assist in the screening of psychological manifestations such as anxiety and depression. This was perceived among the younger doctors, 30 years old or less, who manifest higher levels of depression. More attention and guidance from doctors are required to help and cope with their fears and anxieties generated by working in this pandemic. |

| Chen et al. (2020) | Mental health care for medical staff in China during the COVID-19 outbreak | The lancet. Psychiatry | The use of psychological approaches was not immediately accepted by medical teams, who denied that they were victims of the mental damage that emerged from overwork during the pandemic. This situation shows that it is important that health managers initially create an active listening approach to the difficulties faced by workers and, from there, formulate strategies consistent with the immediate needs of the team, such as availability of adequate places to stay during the pandemic interchange to family social isolation and not to affect them with the coronavirus, as well as having a range of options in psychological approaches to allow each health professional to choose for themselves the most comfortable way to participate in these activities. |

| Kang et al. (2020) | The mental health of medical workers in Wuhan, China dealing with the 2019 novel coronavirus | The lancet. Psychiatry | The situation of fighting against coronavirus has been causing stress, anxiety, depressive symptoms, changes in sleep, denial, anger, and fear in medical teams. Because of this, organizing online platforms to provide psychological counseling, psychiatric care, exchange of ideas to manage critical patients, reduce the social distance from friends and family is an alternative to assist in the mental health care of these professionals, making it possible to avoid permanent psychic injuries and to maintain a good productivity. |

| González-Castro et al. (2020) | Síndrome post-cuidados intensivos después de la pandemia por SARSCoV- 2 | Med Intensiva | The coronavirus pandemic brings waves with an impact on global public health, starting with a high rate of morbidity and mortality due to the disease, impacts on the restriction of ICU resources, and the interruption of care for patients with chronic diseases. Finally, it also causes moral damages and psychological problems to front-line professionals, such as a significant increase in depression/anxiety and suicidal thoughts. |

| Neto et al. (2020) | When health professionals look death in the eye: the mental health of professionals who deal daily with the 2019 coronavirus outbreak | Psychiatry research | The stress caused by the activities of health professionals in the fight against the coronavirus is associated with an increase in anxiety, depression, and both physical and mental exhaustion symptoms. The ICU teams are more associated with the conditions mentioned above, given their contact with dying patients, the changes in their usual work structure, and the decision-making that has a high cost to the psychological of these workers, in the face of resource reallocation during this crisis. In an attempt to reduce these consequences, the creation of specialized networks for mental care, with psychologists and psychiatrists, the willingness to use psychotropic drugs, the improvement in working conditions, and the encouragement for team support are some suitable ways to change these impacts promoted by COVID-19 in the health professionals' psyche. |

| Pinto and Carvalho (2020) | SARS CoV-2 (COVID-19): lessons to be learned by Brazilian Physical Therapists | Brazilian journal of physical therapy | Faced with a pandemic in which the majority of patients require ventilatory management in ICUs, the importance of having physiotherapists specialized in intensive care and effective members of the multidisciplinary team of an ICU is perceived in the public health system to improve dynamics in this environment. It avoids overload other professionals and develops updated and continuous activities to the ventilatory support and the complications caused by the coronavirus. |

3.1. Evaluation of the methodological quality of the included studies

The most common methodological weaknesses in all the studies arose from insufficient reporting: samples, scenarios, and recruitment procedures were often not fully described.

3.2. Interventions in mental health

Twenty-one studies reported the urgent need to implement interventions in order to prevent or reduce mental health problems caused by COVID-19 among health professionals in ICU. Eleven studies demonstrate the need for interventions to organizational adjustments in the ICU, especially related to the emotional conflicts involved in fighting COVID-19.

3.3. Changes in mental health during the pandemic

None of the studies that implemented mental health interventions reported the effects of interventions on health professionals in the ICU due to the rapid entry and exit of patients versus death. The only data available to connect the impact of the pandemic on the mental health of health workers in the ICU came from two longitudinal research studies, that report changes over time, both of low-quality methodological value.

The summary of the results table below shows the studies that contribute to each mental health result. We evaluate that the certainty of the reported results of levels of anxiety, depression, distress, and sleep problems in health care professionals in the ICU during the COVID-19 pandemic, using the GRADE approach, is moderate. 3.7.

3.4. Strategies and resources used

Twenty studies reported that health professionals in the ICU did not use other resources or had individual strategies to deal with their own mental health except the formal interventions. Professional and informal help were strategies reported by eight studies each. A minority (03 studies) of professionals demonstrated that seeking help from a psychologist was important (Fig. 1).

4. Discussion

The impacts of COVID-19 today encompass the social, political, economic, and, above all, the health of the whole society. Concerning the health aspect, it is known that the pandemic is restructuring the cognitive system of individuals, in which its function concerns the self-referenced control of information and responses to the interaction of external social afferents and the person's physiological systems. Consequently, the way the current reality is faced in which the indecision of tomorrow, the fear of death, the mourning of loss, the lack of freedom, and internal anguish are experienced uniquely by each person, who, automatically, responds to the stimulus with changes in both physical and mental health [Wu et al., 2020].

In the face of this emotional pain, the feeling of guilt is humanly understandable. The fact of witnessing unacceptable situations leads the individual to react by blaming himself, either for the choices made or for the inability to perform some actions, such as looking for non-existent answers when blaming the activities of others, for example, government actions or new medical guidelines [El-Hage et al., 2020]. In this perspective, it is seen that the paradox of negative and positive emotions coexists, and the psychic-organic integrity is determined by how each one feeds these emotions. In this sense, not everyone submitted to the same stressor factor will respond negatively. However, everyone involved is vulnerable, especially those who are on the front lines in the fight against COVID-19 [Greenberg et al., 2020].

For army doctors, maintaining sanity is the result, among many aspects, of the number of battles experienced. In this way, the most relevant characteristics of the group in question are promoting the patient's psychophysical protection, exercising the most humanized care, selecting the severity of each situation in the light of current scientific knowledge, and acting with the greatest efficiency in the help of as many as possible people [Piccinni et al., 2020]. However, we are experiencing a global health crisis that most closely resembles a war in which the best-prepared fighters are less susceptible to mental damage, while those facing their first battle suffer such ills early, particularly nurses [Maben and Bridges, 2020].

Because of this, ever since the COVID-19 pandemic appeared, the imbalance between need and availability of resources marks all areas of medicine, especially in intensive care. ICU workers are playing the role of heroes and victims. As they fight for their patients' lives, the change in routine has harmed their health [Piccinni et al., 2020]. The increase in the workload of doctors and nurses [Shen et al., 2020; Maben and Bridges, 2020; Shah et al., 2020], associated with the exorbitant function of breaking bad news [Greenberg et al., 2020; El-Hage et al., 2020], are changing the sleep-wake cycle, with reports of insomnia [Wu et al., 2020; Shah et al., 2020]. This situation has as impact the bad development of work activities, marked by physical and psychological exhaustion [Shen et al., 2020; Rana et al., 2020; Blake et al., 2020; El-Hage et al., 2020].

In a connected way, the lack of personal protective equipment (PPE) is a coefficient of anxiety and fear experienced by the front-line team [Shen et al., 2020; Maben and Bridges, 2020; Rana et al., 2020; Blake et al., 2020]. In this circumstance, restrictive measures for the release of PPE and screening tests created by the United Kingdom were interpreted by second-line nurses as a discriminatory act [Maben and Bridges, 2020]. Given this, there is a close exposure of workers to the virus, which puts their lives at risk by maintaining the health of others. It is known that, in stressful pre-pandemic situations, it was common to seek support and comfort within the family. However, currently, for fear of exposing their family members to COVID-19, the ICU team is performing self-isolation, intensifying the social support reduction and harming themselves [Shen et al., 2020; Maben and Bridges, 2020; Rana et al., 2020; Santarone et al., 2020; Pappa et al., 2020; Shah et al., 2020; El-Hage et al., 2020; Zerbo et al., 2020; Zaka et al., 2020].

At the same time, the increase in the number of deaths [El-Hage et al., 2020], reinforced by the news of the positive diagnosis of co-workers or their death, is commented on in the current literature as accessory causes of the psychic condition of the ICU team [Santarone et al., 2020; Blake et al., 2020; Zerbo et al., 2020]. Despite this situation, this group of professionals, especially the nurses, has been victims of social stigmas in which they are rated as carriers or vectors of the coronavirus [Maben and Bridges, 2020; Blake et al., 2020; El-Hage et al., 2020].

While the use of PPE is essential in preventing the disease, doctors and nurses report difficulties in communicating with patients using these tools [Walton et al., 2020; Shah et al., 2020]. Despite this, moments of conflict are extended beyond the doctor-patient binomial. Because of the high infectivity, the hospital team follows new guidelines that make it impossible to maintain the practice of family visits to hospitalized patients and the presentation of the deceased to relatives is abolished. Given this, disagreements arise between the patient's family, motivated by premature grief, and the ICU team [Shen et al., 2020; Mukhtar, 2020; El-Hage et al., 2020].

Thus, the professionals of the ICU are seen by patients as the only human and affective bond in the impossibility of contact with their loved ones. This fact is relevant for both sides, whereas patients create insecure patterns of affable support in care professionals, and the last develop sentimental connections to the first. Consequently, when there is evidence of a cure for someone hospitalized in the ICU, this is a cause for celebration and joy for everyone who has followed this process with care. However, the ineffectiveness of the therapies performed and the patient's clinical decline promotes pain, grief, and anguish in everyone at the ICU, who no longer look at that individual as a mere patient, but as a member of the new family cycle created in the melancholy reality of COVID -19 [Maben and Bridges, 2020; El-Hage et al., 2020; Zerbo et al., 2020].

In addition, most nurses report difficulties in adapting to the new protocols of the ICU services, which have become more rigid in the face of the current situation [Maben and Bridges, 2020; Blake et al., 2020; El-Hage et al., 2020]. This condition is connected to the multiple tasks that these professionals perform and to the unbalanced distribution of patients under the supervision of a professional [Wu et al., 2020; Shah et al., 2020]. Under usual ICU conditions, the proportion is one nurse to two or even four patients, and another backup nurse for every four beds, with the function of providing support in the face of excessive workload or for possible changes, if any professional becomes ill [Walton et al., 2020; Greenberg et al., 2020].

In the meantime, a criticism mentioned by the Spanish Society of Intensive Nursing and Coronary Units concerns the lack of recognition of this group's specialty in intensive care and the negligence on the part of the services in hiring a sufficient number of physiotherapists. It has, generally, one physiotherapist per unit, who also suffers from work overload [Raurell-Torredà, 2020; Raurell-Torredà et al., 2020].

However, in a conflict situation, effective leadership is imperative. Thus, another relevant complaint from the ICU team is the negative lead of managers in certain sectors and, even with an increased workload and amount of work, the financial reward is considered insufficient [Shah et al., 2020].

At the same time, the fear of lack of technical skills and knowledge about the SARS-CoV-2 virus are significant coefficients in the mental well-being of health care professionals [Shah et al., 2020; El-Hage et al., 2020]. To portray these aspects, a study in Turkey involving 346 people, including anesthesiologists and residents of the area, stated that the residents called to act in the ICU against COVID-19 were more indecisive, with a tendency to make wrong decisions, because of the small professional experience. [Dost et al., 2020]. A similar situation occurred with the pediatric ICU team of a hospital in Massachusetts, which started to accommodate adult patients with COVID-19 positive. As if the scarcity of information related to the disease in question was not enough, these professionals were challenged in the management of patients with biotype and clinical-laboratory parameters totally different from the usual [Yager et al., 2020].

On the other hand, the reorganization of the physical spaces of the ICUs directly influences the team's dynamics. It happens because many professionals were relocated to other ICUs, having to work with people who were not their professional colleagues and because of new ones hired to enhance the teams. Such factors made the old team feel uncomfortable with the new member, with whom they did not maintain a cohesive bond in the coexistence relationship, having reports of the feeling that it did not have an open space to talk about their own emotions, a shame to question, and a fear of making any mistake and being judged by this. [Maben and Bridges, 2020; El-Hage et al., 2020; Zerbo et al., 2020].

However, one of the main factors in the mental integrity of front-line health care professionals is the new ethical dilemmas that the pandemic has brought with it. Doctors, mainly, have their cognitive abilities and memory required repeatedly, quickly, and under circumstances of high psychological tension. This situation results in the common selflessness of these workers about their own health [Blake et al., 2020; El-Hage et al., 2020].

In this circumstance, allocation and screening of resources for the management of the patient in the ICU create uncertainties and self-questions from the doctors about the principles that govern their activity. Thus, acting with justice is not only giving the sick person access to available therapies but also rationalizing resources. Therefore, some ethical criteria, such as beneficence, non-maleficence, autonomy to make patient decisions, and shared justice, assists in the selection of beneficiaries for use of the ICU. However, the pandemic means that these parameters can no longer be reconciled, causing stress to the doctor. Many professionals revealed that the uncertainty in the level of management is proportional to the clinical complexity that patients have. Consequently, for them, it is considered as an attitude of high negative psychological impact the suspension of ventilatory support therapy in ICU, in comparison to the nonactivational of it and the aggregation of the patient in this environment [Rubio et al., 2020; Romanò, 2020].

Ratifying this reality, several institutions are selecting health professionals intending to assess the psychic impacts of the pandemic. Thus, a cross-sectional survey using the Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC) and the Social Support Rating Scale (SSRS), applied to 1521 professionals, obtained a prevalence of 14.1% of psychological imbalances [Cai et al., 2020]. Similarly, a Chinese hospital, using the Zung Self-Assessment Depression Scale (SDS) and the Zung Self-Assessment Anxiety Scale (SAS) in a group of 23 doctors and 36 nurses, revealed that doctors under the age of 30 years had high scores for depression compared to older people [Lian et al., 2020].

Therefore, it is clear that the consequences of COVID-19 in the ICU team are diverse. Among the reported outcomes are found: stress, anxiety, depression, anguish, anger, fear, guilt, insomnia and abuse of substances [Chen et al., 2020; Kang et al., 2020; Rana et al., 2020; Blake et al., 2020; González-Castro et al., 2020; Senni, 2020], as well as a deficit in labor productivity [Greenberg et al., 2020] and manifestations of compulsive-obsessive attitudes, such as excessive hand washing [Cai et al., 2020]. In this sense, a study evaluating the mental integrity of 85 nurses at the ICU had as a quotient that 59% had reduced eating habits, 55% had fatigue, 45% sleep-related problems, 28% irritability, 26% constant crying and 2% suicidal ideations [Shen et al., 2020].

The high predisposition for suicide among doctors is recognized. In the United States, the percentage of doctors showing typical Burnout symptoms reaches 54.4% [Shah et al., 2020]. In this sense, the fear of discrimination and of being labeled associated with the feeling of shame and denial, lead doctors to avoid talking about their feelings and stressors, as well as not seeking psychological and psychiatric support. Therefore, these attitudes are decisive in the poor outcomes found for this group [Rana et al., 2020; Greenberg et al., 2020].

Even so, the feeling of guilt is not restricted to the team that actively works in the ICU. That means the risks are beyond the walls of this environment. The professionals of this place, who have underlying diseases or are in a pregnant situation and were released from their work practice, report guilt for not being present during this pandemic moment. In addition, the risk of developing PTSD in the ICU team is above 10% of the range considered normal [Walton et al., 2020]. Besides, front-line female health professionals, young and exercising the position of nurses, when compared to doctors, showed symptoms of anxiety, depression and PTSD more frequently. The second-line professionals, on the other hand, show conditions similar to Munchausen syndrome by proxy [El-Hage et al., 2020].

Given this situation, a systematic review with a meta-analysis of 13 cross-sectional surveys with 33062 participants was carried out to assess the prevalence of anxiety, depression and insomnia in health professionals. It was found that while the Chinese population, during the same study period, had fluctuating rates of 22.6%–36.3% for anxiety and 16.5%–48.3% for depression, health professionals had similar numbers for anxiety (23.2%) and depression (22.8%), and also an average of 38.9% of insomnia after the emergence of the pandemic. In addition, it clarifies the high prevalence of psychological problems in nurses because the majority of the members of this profession are women, but, also because they have a more intimate contact with the patient and the routine provision of invasive services, such as sputum collection [Pappa et al., 2020].

Despite these alarming numbers, not everyone who makes up the ICU team will develop such conditions. It means that, while it is relevant to analyze and evaluate the current psychological situation of front-line professionals, the individual's physiological responses, such as fear and anxiety, should not be conceptualized as a disease when the person is exposed to a stressful situation. Therefore, even if everyone experiences a challenging moment, both in their activity and in their personal integrity, most professionals exhibit resilience and, consequently, the chance of developing or maintain psychic-organic changes in the long term is small [Maben and Bridges, 2020; Walton et al., 2020].

Thus, resilience is defined as the human capacity to face and recover from significant tribulations. Therefore, the characteristics expressed by resilient people are resistance, perseverance and hope. This demonstrates that psychological resilience is a protective factor, acting as a mean of primary prevention against mental pathologies and that results in aggrandizing the person that faces the adversities [Hou et al., 2020; Cai et al., 2020].

In this sense, when studying psychological stress in 2110 medical teams and 2158 students called to act against COVID-19 in Wuhan, it was noticed that the first group showed a feeling of confidence superior to the second one [Wu et al., 2020]. This analysis validates the hypothesis that the relationship between resilience and mental health is attenuated as the person gets older. In other words, middle-aged professionals are less dependent on this aspect, given that they have more technical experience, longer employment, and had experienced outbreaks and previous epidemics that have conditioned them to a mental state less susceptible to stress and fear. On the other hand, younger people show more anxiety-depression disorders. They, however, also show more willingness to seek help from mental services actively. In this way, young professionals are more likely to be conditioned to increase their resilience through techniques for managing stress and meditation, being, therefore, a priority group in the actions developed to improve the psychic-organic health of the ICU team [Hou et al., 2020].

At the same time, another factor related to resilience is social support. In this logic, social support denotes the experience that the individual has of belonging to a group of people who reciprocally help each other. Therefore, the maintenance of the integrity of the ICU team is a reason that helps to raise the levels of individual resilience, as the friendship with more experienced colleagues makes the professional believe in the possibility of obtaining the necessary help to face what makes them feel stressed, increasing, consequently, the belief that they can face the adversities by themselves. Therefore, the cohesion between colleagues and their respective managers is decisive in the way in which the coronavirus will act in the resilience and the health of these people [Maben and Bridges, 2020; Hou et al., 2020; Cai et al., 2020; Rubio et al., 2020; Yager et al., 2020].

Based on what was exposed above, health systems take actions daily intending to prevent psychological damage to their members. One of the main actions is to encourage social support, whether by family members of health professionals or by their bosses. The way to shorten social distance and avoid viral load is through online methods, such as video calls [Shen et al., 2020; Walton et al., 2020; Blake et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020]. At the same time, good leadership should be encouraged, based on an active communication between boss and workers. A fair leader is considered to be the one who shares his knowledge, anxieties and doubts honestly and shows empathy to others, as well as one that motivates the encouragement of its workers to maintain self-care, and shows humanity and humility in his attitudes [Walton et al., 2020; Blake et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020; Shah et al., 2020]. Therefore, the effectiveness in trying to maintain the current team is undeniable [Shen et al., 2020; Maben and Bridges, 2020; Zaka et al., 2020; Yager et al., 2020]. In case this is not possible, it is necessary to hire new members, associated with actions that make them familiar with the team and service dynamics [Shah et al., 2020]. Thus, it is clear that an extensive apparatus is not necessary to improve positively the performance of the front-line team. Chinese works report that nurses' felt gratitude from the general public that donated moisturizing hand creams [Maben and Bridges, 2020; El-Hage et al., 2020].

In addition to these changes, other alternatives are suggested by health workers. It is asked to hospitals, in a general way, to provide adequate environments so the teams can rest, especially because they are trying to maintain family isolation and do not have other places to rest [Chen et al., 2020; Walton et al., 2020; Rana et al., 2020; Pappa et al., 2020; Zaka et al., 2020]. Besides this, it is suggested to redefine the equivalence between patients and nurses, seeking proportions such as 1: 1 or 1: 2, respectively, as well as the stimulus for hiring physiotherapists, specialized in intensive care [Raurell-Torredà, 2020].

Given this, several ICUs readjusted their shift dynamics. Thus, it was adopted a shift rotation model, in which, after 4–6 h of continuous work, the health care team must rest [Shen et al., 2020; Kang et al., 2020; Walton et al., 2020; Rana et al., 2020; Pappa et al., 2020; Blake et al., 2020; El-Hage et al., 2020]. At the same time, the reduction in daily working hours to less than 16 h per day revealed a drop of 18% in the rate of medical errors [Santarone et al., 2020]. Among the suggested mechanisms to reduce stress, it was well accepted practices as drawing, talking, singing, exercising, breathing deeply, and looking out the window [Shen et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2020; Neto et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020].

At the same time, to remedy the insecurity of technical and scientific knowledge, refresher courses are executed. In this way, as indicated by workers, hospitals provide courses for equipment management, biosafety [Chen et al., 2020; Pappa et al., 2020; Shah et al., 2020], and training for physiotherapists about the best parameters in the approach to mechanical ventilation in hospitalized patients [Pinto and Carvalho, 2020]. As for the group of physicians residing in anesthesiology, it focuses on offering simulations directed to the techniques of orotracheal intubation and other duties specific to the specialty [Dost et al., 2020]. If it is not enough, many hospitals also develop education courses in palliative care, helping teams to have a more humanized and appropriate management of the emotional state of patients [Santarone et al., 2020; Zaka et al., 2020; Romanò, 2020].

Despite this, it is necessary to have specialized support for the mental care of the ICU team. In this context, a psychologist, a psychiatrist, and professionals’ family members constitute the mental health team. Some measures are recommended to achieve therapeutic success, such as starting the therapy process in comfortable spaces that reminiscent of good feelings - to obtain confidence in the tasks to be performed -, and encouraging teams to perform functions in pairs, with the exchange of emotional experiences or doubts about the job with those who they have a friendly relationship [Chen et al., 2020; Kang et al., 2020; Walton et al., 2020; Rana et al., 2020; Santarone et al., 2020]. It is also essential that each team has its psychologist, either for individualized approaches or for group actions [Shen et al., 2020].

However, management through virtual platforms is more indicated for health care teams that won by the trust of their therapists or in situations focused on discussing common team challenges [Kang et al., 2020; Greenberg et al., 2020; Neto et al., 2020; Zaka et al., 2020]. It is relevant to emphasize that not all members of health care teams immediately accept psychological help due to the prejudices and fears brought with them. Thus, there may be obstacles in the implementation of this approach. They need to be analyzed and changed according to the people's particularities [Chen et al., 2020]. In addition, it is necessary to demystify and offer to everyone, through telemedicine, consultations with psychiatrists, and the use of psychotropics, if it is necessary [Neto et al., 2020].

In order to preserve mental integrity, several psychological approaches are reported in the literature. The coping model based on anticipating, planning, and dissuading [El-Hage et al., 2020] serves the same purpose as the health belief model applied to ICU teams in Pakistan. This psychotherapeutic instrument offers to the individual the possibility of identifying situations of susceptibility, assessing its severity, perceiving which factors are threatening, looking for what barriers exist and the benefits arising from overcoming them, and, finally, stratifying the ways in which the individual will use them. Therefore, the primary focus of psychological therapies means acting as a way of primary prevention from the impacts generated by COVID-19 on mental health, promoting in health care teams the maintenance of resilience [Mukhtar, 2020].

Despite this, the impact generated by the coronavirus on medical ethics is substantial. In an attempt to improve the moral damage to the ICU doctors, several hospitals create guidelines to conduct decisions. It is also relevant that the leaders of the institutions reinforce that the medical decision is not an individual attitude, but the result of the ideals of a team [Rubio et al., 2020; Walton et al., 2020; Blake et al., 2020; Shah et al., 2020]. Because of this, one of the documents used as a reference is the one from the Italian Society for Anesthesia Analgesia and Intensive Care (SIAARTI). This document, published in an update on March 03, 2020, draws up guidelines for the hospitalization of patients in ICU. It also talks about the discontinuation of therapies in the face of the imbalance between their availability and their insufficiency [Romanò, 2020]. Through these paths, it is possible to relieve doctors of their responsibilities, which today has a high emotional cost, and create explicit tactics for allocating instruments at a time of unavailability [Piccinni et al., 2020].

Finally, it is relevant that these actions must not be more harmful to the health of the ICU team. Given this, all the measures that the services carry out need to be adapted to the reality and the immediate need of the professionals. In this sense, taking into account psychological stress, the performance of psychological interrogations reveals a poor prognosis when compared to the benefits brought by the institution of deadening and mental reprocessing practices [Maben and Bridges, 2020; Greenberg et al., 2020]. Thus, it was seen in the literature that the health care team stated that they dislike self-questioners because they prefer the passive reception of information made available for longer periods for personal use when required, rather than being tested [Blake et al., 2020].

Therefore, it is imperative to monitor the ICU team. In this circumstance, nowadays, it is necessary to identify the most affected or susceptible individuals to work on primary methods of prevention of mental damage [Greenberg et al., 2020; Shah et al., 2020; El-Hage et al., 2020]. At the same time, this monitoring should be extended to post-pandemic periods, to hierarchically screen professionals, giving priority to the front-line team. Thus, after this moment, it is possible to use questionnaires aimed at identifying characteristic manifestations of anxiety, depression, exhaustion, impact, and mental suffering. The psychic vulnerability resulting from calamities, such as the current one, is a provider for pathological grief and PTSD. Therefore, it must be done an extra investment to carry out psychological follow-up from 6 to 12 months post-pandemic properly [Maben and Bridges, 2020; El-Hage et al., 2020].

5. Limitations

Among the limitations found doing this work, the small number of published studies with the application of standardized questionnaires for the assessment of the psychological consequences in the evaluated subjects stands out. Consequently, the results found were heterogeneous. Besides, some studies have their methodology based on the acquisition of self-reports and this can be a bias factor. So, their results should be analyzed with caution. In this sense, future research must be done to demonstrate the ways that the actions of protection of the medical team are having effects, such as a more detailed assessment of the physical, mental and social repercussions that the pandemic will promote in the lives of these individuals.

6. Conclusion

During the COVID-19 pandemic period, the structure of the ICU activities changed rapidly. The disproportion between the need for technological supplies in intensive care and their scarcity, promotes, among many factors, higher levels of psychological stress. Anxiety, irritability, insomnia, fear, and anguish were observed during the pandemic, probably related to extremely high workloads and the lack of personal protective equipment. In this sense, promoting actions to mitigate such psychic-organic impacts is essential. It is necessary to reflect on the quality of planning for the preparation of health professionals in the ICU for the most diverse clinical and psychological barriers linked to the pandemic.

Funding

School of Medicine of ABC – FMABC and Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) – institution linked to the Brazilian Department of Science, Technology and Innovation to encourage research in Brazil.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Flaviane Cristine Troglio da Silva: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Modesto Leite Rolim Neto: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank the School of Medicine of ABC – FMABC and Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) – institution linked to the Brazilian Department of Science, Technology.

References

- Blake H., Bermingham F., Johnson G., Tabner A. Mitigating the psychological impact of COVID-19 on healthcare workers: a digital learning package. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2020;17(9):2997. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17092997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai W., Lian B., Song X., Hou T., Deng G., Li H. A cross-sectional study on mental health among health care workers during the outbreak of Corona Virus Disease 2019. Asian journal of psychiatry. 2020;51:102111. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102111. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q., Liang M., Li Y., Guo J., Fei D., Wang L., He L., Sheng C., Cai Y., Li X., Wang J., Zhang Z. Mental health care for medical staff in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. The lancet. Psychiatry. 2020;7(4):e15–e16. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30078-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (Casp) CASP checklist for qualitative research. 2018. https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists [20 March 2020]. Available from:

- Dost B., Koksal E., Terzi Ö., Bilgin S., Ustun Y.B., Arslan H.N. Attitudes of anesthesiology specialists and residents toward patients infected with the novel coronavirus (COVID-19): a national survey study. Surg. Infect. 2020;21(4):350–356. doi: 10.1089/sur.2020.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Hage W., Hingray C., Lemogne C., Yrondi A., Brunault P., Bienvenu T., Etain B., Paquet C., Gohier B., Bennabi D., Birmes P., Sauvaget A., Fakra E., Prieto N., Bulteau S., Vidailhet P., Camus V., Leboyer M., Krebs M.-O., Aouizerate B. Les professionnels de santé face à la pandémie de la maladie à coronavirus (COVID-19) : quels risques pour leur santé mentale ? Encephale. 2020;46(3S):S73–S80. doi: 10.1016/j.encep.2020.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira M.A., Carvalho Filho M.A., Franco G.S., Franco R.S. Profissionalismo Médico e o Contrato Social: reflexões acerca da Pandemia de COVID-19. Acta Med. Port. 2020;33(6):362–364. doi: 10.20344/amp.13769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Castro A., Lorenzo A.G., Escudero-Acha P., Rodriguez-Borregan J.C. Síndrome post-cuidados intensivos después de la pandemia por SARS-CoV-2. Med. Intensiva. 2020;44(8):522–523. doi: 10.1016/j.medin.2020.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg N., Docherty M., Gnanapragasam S., Wessely S. Managing mental health challenges faced by healthcare workers during covid-19 pandemic. BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 2020;368:m1211. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyatt G., Oxman A.D., Akl E.A., et al. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011;64(4):383–394. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.026. published Online First: 2011/01/05] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou T., Zhang T., Cai W., Song X., Chen A., Deng G., Ni C. Social support and mental health among health care workers during Coronavirus Disease 2019 outbreak: a moderated mediation model. PloS One. 2020;15(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0233831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johanna Briggs Institute Critical appraisal tools. 2018. http://joannabriggs-webdev.org/research/critical-appraisal-tools.html [Available from:

- Kang L., Li Y., Hu S., Chen M., Yang C., Yang B.X., Wang Y., Hu J., Lai J., Ma X., Chen J., Guan L., Wang G., Ma H., Liu Z. The mental health of medical workers in Wuhan, China dealing with the 2019 novel coronavirus. The lancet. Psychiatry. 2020;7(3):e14. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30047-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maben J., Bridges J. Covid-19: supporting nurses' psychological and mental health. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020;29(15–16):2742–2750. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhtar S. Mental health and emotional impact of COVID-19: applying Health Belief Model for medical staff to general public of Pakistan. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020;87:28–29. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neto M., Almeida H.G., Esmeraldo J.D., Nobre C.B., Pinheiro W.R., de Oliveira C., Sousa I., Lima O., Lima N., Moreira M.M., Lima C., Júnior J.G., da Silva C. When health professionals look death in the eye: the mental health of professionals who deal daily with the 2019 coronavirus outbreak. Psychiatr. Res. 2020;288:112972. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappa S., Ntella V., Giannakas T., Giannakoulis V.G., Papoutsi E., Katsaounou P. Advance online publication; 2020. Prevalence of Depression, Anxiety, and Insomnia Among Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, S0889-1591(20)30845-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piccinni M., Aprile A., Benciolini P., Busatta L., Cadamuro E., Malacarne P., Marin F., Orsi L., Palermo Fabris E., Pisu A., Provolo D., Scalera A., Tomasi M., Zamperetti N., Rodriguez D. Considerazioni etiche, deontologiche e giuridiche sul Documento SIAARTI “Raccomandazioni de ética clinica per I’ammissone a trattamenti intensivi e per la loro sospensione, in condizioni eccezionali di squilibrio tra necessità e risorse disponibili”. Recenti Prog. Med. 2020;111(4):212–222. doi: 10.1701/3347.33184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto T.F., Carvalho C. SARS CoV-2 (COVID-19): lessons to be learned by Brazilian Physical Therapists. Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2020;24(3):185–186. doi: 10.1016/j.bjpt.2020.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rana W., Mukhtar S., Mukhtar S. Mental health of medical workers in Pakistan during the pandemic COVID-19 outbreak. Asian journal of psychiatry. 2020;51:102080. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102080. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raurell-Torredà M. Management OF ICU nursing teams during the COVID-19 pandemic. Gestión de los EQUIPOS de enfermería de UCI durante la PANDEMIA COVID-19. Enfermería Intensiva. 2020;31(2):49–51. doi: 10.1016/j.enfi.2020.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raurell-Torredà M., Martínez-Estalella G., Frade-Mera M.J., Carrasco Rodríguez-Rey L.F., Romero de San Pío E. Reflexiones derivadas de la pandemia COVID-19. Reflexiones derivadas de la pandemia COVID-19. Enfermería Intensiva. 2020;31(2):90–93. doi: 10.1016/j.enfi.2020.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanò M. Fra cure intensive e cure palliative ai tempi di CoViD-19. Recenti Prog. Med. 2020;111(4):223–230. doi: 10.1701/3347.33185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubio O., Estella A., Cabre L., Saralegui-Reta I., Martin M.C., Zapata L., Esquerda M., Ferrer R., Castellanos A., Trenado J., Amblas J. Recomendaciones éticas para la toma de decisiones difíciles en las unidades de cuidados intensivos ante la situación excepcional de crisis por la pandemia por COVID-19: revisión rápida y consenso de expertos. Med. Intensiva. 2020 Oct;44(7):439–445. doi: 10.1016/j.medin.2020.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santarone K., McKenney M., Elkbuli A. Preserving mental health and resilience in frontline healthcare workers during COVID-19. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2020;38(7):1530–1531. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.04.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senni M. COVID-19 experience in Bergamo, Italy. Eur. Heart J. 2020;41(19):1783–1784. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah K., Chaudhari G., Kamrai D., Lail A., Patel R.S. How essential is to focus on physician's health and burnout in coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic? Cureus. 2020;12(4) doi: 10.7759/cureus.7538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shea B.J., Reeves B.C., Wells G., et al. Amstar 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358:j4008. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j4008. published Online First: 2017/09/25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen X., Zou X., Zhong X., Yan J., Li L. Psychological stress of ICU nurses in the time of COVID-19. Crit. Care. 2020;24(1):200. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-02926-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton M., Murray E., Christian M.D. Mental health care for medical staff and affiliated healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. European heart journal. Acute cardiovascular care. 2020;9(3):241–247. doi: 10.1177/2048872620922795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu W., Zhang Y., Wang P., Zhang L., Wang G., Lei G., Xiao Q., Cao X., Bian Y., Xie S., Huang F., Luo N., Zhang J., Luo M. Psychological stress of medical staffs during outbreak of COVID-19 and adjustment strategy. J. Med. Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25914. 10.1002/jmv.25914. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yager P.H., Whalen K.A., Cummings B.M. Repurposing a pediatric ICU for adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382(22):e80. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2014819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaka A., Shamloo S.E., Fiorente P., Tafuri A. COVID-19 pandemic as a watershed moment: a call for systematic psychological health care for frontline medical staff. J. Health Psychol. 2020;25(7):883–887. doi: 10.1177/1359105320925148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerbo C.B.S., Perrone G., Malta G., Argo A. The medico-legal implications in medical malpractice claims during Covid-19 pandemic: increase or trend reversal? Med. Leg. J. 2020 doi: 10.1177/0025817220926925. 25817220926925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]