Abstract

Genome engineering of bacteriophages provides opportunities for precise genetic dissection and for numerous phage applications including therapy. However, few methods are available for facile construction of unmarked precise deletions, insertions, gene replacements and point mutations in bacteriophages for most bacterial hosts. Here we describe CRISPY-BRED and CRISPY-BRIP, methods for efficient and precise engineering of phages in Mycobacterium species, with applicability to phages of a variety of other hosts. This recombineering approach uses phage-derived recombination proteins and Streptococcus thermophilus CRISPR-Cas9.

Subject terms: Prokaryote, Microbial genetics, Bacterial genetics, Mutagenesis, Bacteriophages

Introduction

Bacteriophage genomics reveals massive genetic diversity and a vast abundance of functionally ill-defined genes1. Efficient and precise phage genome engineering is a critical step in understanding phage biology and in developing phages as effective therapeutics, diagnostics, and for numerous other applications2–4. We previously described Bacteriophage Recombineering of Electroporated DNA (BRED) as a method for engineering Mycobacterium smegmatis phages5, which has been subsequently adapted for phages of Klebsiella6, Escherichia coli7, and Salmonella8. In BRED, phage genomic DNA and a synthetic DNA substrate containing the desired mutation are co-electroporated into bacterial cells that express phage Che9c RecET-like recombination genes, 60 and 619, and plated for infectious centers on a bacterial lawn. Recombination is sufficiently efficient to enable identification of plaques containing mutant phage genomes by PCR without genetic selection, although these primary plaques typically contain both mutant and wild type phage particles and require further purification and screening5. Deletion of non-essential genes is often simple and relatively efficient using BRED; we previously showed that mixed primary plaques could be recovered from such deletions at an average frequency of 14% (range 4–60%)5. However, other types of recombinants such as larger deletions, replacements, and insertions are recovered at somewhat lower frequencies, demanding extensive screening of dozens or even hundreds of plaques. This is also observed when genome editing has deleterious impacts on phage growth10.

CRISPR-Cas systems provide defense against viral attack and are present in numerous bacterial and archaeal species11. Spacer sequences between repeat motifs in long arrays are transcribed to produce short RNAs (crRNAs) that together with Cas proteins target invading phage DNA for destruction through recognition of a protospacer corresponding to the crRNA. CRISPR-Cas systems are thus readily adapted for phage engineering, and have been used to modify phages that infect Escherichia coli12, Streptococcus thermophilus13 and Vibrio cholerae14 among others (Reviewed in Hatoum-Aslan, 2018)15. These previously described methods primarily rely on host-derived recombination functions and/or CRISPR-Cas15. The combination of highly efficient recombineering systems and CRISPR-Cas selection has been described for engineering of bacterial genomes16, and we describe a similar approach here for engineering phage genomes, taking advantage of the active and inactive Cas proteins described for genome editing and gene silencing (CRISPRi) in Mycobacterium17,18.

Results

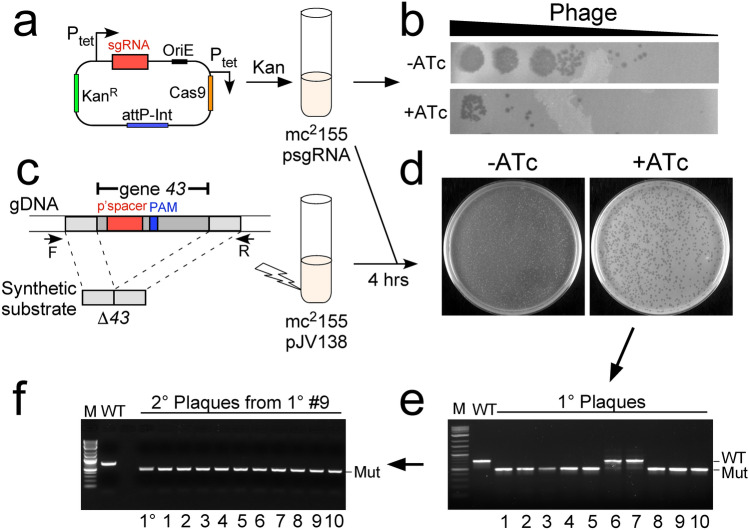

We have combined BRED technology with CRISPR-Cas9 to facilitate efficient and precise phage genome engineering. In this approach, recombineering promotes recombinant formation and CRISPR-Cas9 targeting is used to counter-select against the parental (non-recombinant) phage (Fig. 1a). First, a plasmid derivative of pIRL53 (e.g. psgRNA) is constructed in which a single guide RNA (sgRNA) sequence is fused to an anhydrotetracycline (ATc)-inducible Ptet promoter. The plasmid contains a Streptococcus thermophilus cas9 gene17, a kanamycin resistance gene, an E. coli replication origin, and an attP-Int cassette for chromosomal integration in mycobacteria19. The sgRNA component is typically 20 bp long and is designed to target either DNA strand within the parent phage only. The sgRNA sequence must be positioned 5′ to a Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM), and a variety of PAM sites with their relative activity in gene silencing has been described17. The efficiency of sgRNA targeting can be readily determined by reduction in plaque formation of the target phage on lawns of ATc-induced psgRNA-containing cells relative to uninduced cells (Fig. 1b). The reduction in plating efficiency varies from two to five orders of magnitude depending on the phage and the PAM/sgRNA (Fig. 1b, Table 1); the example shown in Fig. 1b indicates a reduction of 10–3 with induction of sgRNA expression. There is little or no difference in selection level if the transcribed or non-transcribed strand is targeted (Table 1).

Figure 1.

CRISPY-BRED phage engineering. (a). In the first step of the CRISPY-BRED strategy, a CRISPR-Cas9 plasmid is constructed expressing a single guide RNA (sgRNA, red box) corresponding to a phage gene targeted for deletion or replacement (BuzzLyseyear gene 43 in this example); sgRNA expression is driven by a Ptet promoter and is inducible by addition of anhydrotetracycline (ATc). This plasmid is then introduced into M. smegmatis mc2155 selecting for kanamycin resistant transformants. (b) The sgRNA interference of phage infection is demonstrated by plating tenfold serial BuzzLyseyear dilutions on lawns of M. smegmatis transformants carrying the sgRNA plasmid (psgRNA) with (+ ATc) or without (-ATc) the inducer of sgRNA expression. In this example, the sgRNA reduces the efficiency of BuzzLyseyear plaquing approximately three orders of magnitude. (c) Two DNAs-BuzzLyseyear genomic DNA (gDNA) and a 500 bp synthetic DNA containing the sequences flanking gene 43-are co-electroporated into M. smegmatis mc2155 carrying the recombineering plasmid pJV138 (mc2155pJV138). (d) After four hours recovery, the progeny are plated with M. smegmatis mc2155psgRNA cells in the presence of kanamycin (to counter select against the recombineering strain) to yield primary plaques in the presence or absence of ATc inducer. (e) Ten individual primary plaques from the + ATc plate were screened by PCR using forward and reverse primers (F, R, panel c), eight of which show a product corresponding to the desired mutant. (f) Phage particles from primary plaque #9 were diluted, replated on M. smegmatis mc2155 and ten secondary plaques screened by PCR, all of which have a mutant-sized product. CRISPY-BRIP differs in this overall strategy only in that the recombineering cells in panel c are electroporated with synthetic DNA substrate only, and the cell mixture is then infected with phage particles. Original gel images are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Table 1.

Recovery of engineered phages using CRISPY-BRED.

| Phage1 | Mut2 | Gene Targets3 | PAM4 | sgRNA (strand)5 | EOP6 | 1° plaq mut/tot7 | 2° plaq mut/tot8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alma∆ori9 | ∆497 bp | ori ncRNA, 35 | NNAGAAA | sgRNA-1( +) | 10–2 | 1/1 | 4/4 |

| Alma∆ori9 | ∆497 bp | ori ncRNA, 35 | NNAGAAG | sgRNA-2(+ /−)2 | 10–2 | ND | ND |

| BPs∆32-33_HRM10 | ∆1603 bp | 32 (int), 33 (rep) | NNAGAAT | sgRNA-3( +) | 10–3 | 5/20 | 2/2 |

| BPs∆32-33_HRM10 | ∆1603 bp | 32 (int), 33 (rep) | NNAGAAT | sgRNA-3( +) | 10–3 | 18/20 | ND |

| BuzzLyseyear∆41 | ∆117 bp | 41 | NNGGAAG | sgRNA-4( +) | 10–2 | 10/10 | 10/10 |

| BuzzLyseyear∆42 | ∆150 bp | 42 | NNGGAAC | sgRNA-5(-) | 10–2 | 10/10 | 10/10 |

| BuzzLyseyear∆43 | ∆240 bp | 43 | NNAGAAC | sgRNA-6( +) | 10–3 | 8/10 | 10/10 |

| BuzzLyseyear∆43 | ∆240 bp | 43 | NNAGGAT | sgRNA-7( +) | 10–3 | 6/10 | 10/10 |

| LadyBird∆ori9 | ∆400 bp | ori ncRNA, 34 | NNAGAAG | sgRNA-8(+ /−)2 | 10–3 | ND | ND |

| LadyBird∆ori9 | ∆400 bp | ori ncRNA, 34 | NNAGCAT | sgRNA-9(+ /−)2 | 10–4 | 3/12 | 5/5 |

| Miko∆repA9 | ∆870 bp | 36 (repA) | NNAGAAA | sgRNA-10( +) | 10–2 | 0/8 | ND |

| Miko∆repA9 | ∆870 bp | 36 (repA) | NNAGAAG | sgRNA-11( +) | 10–2 | 3/8 | 12/12 |

| phiFW111 | ∆279 bp | 14 (capsid) | NNAGAAA | sgRNA-12( +) | 10–4 | 1/12 | 4/4 |

| Fionnbharth_ F52mut3 | ∆360 bp/ins. 273 bp | 47 (rep)/ F52mut3 | NNGGAAA | sgRNA-13( +) | 10–3 | 22/24 | ND |

| Fionnbharth∆45–47 mCherry | ∆2509/ins. 1216 bp | 45 (int), 46, 47 (rep)/ mCherry | NNGGAAA | sgRNA-13( +) | 10–3 | 16/16 | ND |

| BPs∆32-33_HRM10 mCherry | ∆1603/ins. 1216 bp | 32 (int), 33 (rep)/ mCherry | NNAGAAT | sgRNA-3( +) | 10–3 | 14/18 | ND |

| Adephagia∆41–43 mCherry | ∆2123/ins. 1216 bp | 41 (int), 42, 43 (rep)/ mCherry | NNAGAAG | sgRNA-14( +) | 10–3 | 1/1 | 26/26 |

1Name of the desired phage recombinant.

2Mutation (Mut) indicates the type of mutation (∆; deletion, ins; insertion) and sizes thereof.

3Deleted/ inserted genes with putative gene functions in parentheses (int, integrase; rep, immunity repressor).

4The PAM site for each sgRNA is shown.

5For some constructions two sgRNA were tested for the same target genome; ( +) or (−) indicates whether the template ( +) or non-template (−) strand is targeted; (+ /−) indicates RNA transcripts are present on both strands. See Supplementary Table 1 for sequences.

6EOP, Efficiency of plaquing, as determined by differences in phage titers on ATc induced and uninduced media.

7Number of primary mutant plaques from the total tested. ND, Not Determined.

8Number of secondary mutant plaques from the total tested. ND, Not Determined.

9As described in reference 2525.

10Two slightly different BPs derivatives that carry host range mutations were engineered to have the same deletion.

11Phage phiFW1 is a derivative of phiTM4526, a derivative of Bxb1.

The synthetic dsDNA substrate used for BRED typically contains 150–250 bp of homologous sequence to the phage target on either side of the mutation, whether it is a deletion, replacement, or insertion (Fig. 1c). The dsDNA substrate and relevant phage genomic DNA (gDNA) are co-electroporated into recombineering-proficient cells that express recombination genes derived from phage Che9c (e.g. M. smegmatis mc2155pJV138) (Fig. 1d). Recovery is allowed for about 4 h, which is sufficient for completion of one round of viral lytic growth and the release of phage particles, which have either wild type or mutant genomes. This is a departure from the BRED method where recovery is shorter than a lytic cycle of growth. The mixture of recombineering cells and phage is then plated together with the selective M. smegmatis mc2155psgRNA strain onto solid media containing kanamycin to prevent growth of the recombineering strain (Fig. 1d). Plating this mixture onto solid media lacking ATc permits replication and plaquing by both wild type and mutant phage derivatives, but plating onto solid media containing ATc induces expression of the CRISPR-Cas system and selects against replication of wild type phage genomes. In the absence of ATc plaques derived from both wild type and mutant particles are efficiently recovered (and can give near-confluence lysis as in Fig. 1c), but sgRNA-expression reduces wild type growth, enriching for desired recombinant phage and any other variants escaping CRISPR-Cas selection. Thus, plating in the presence and absence of ATc indicates the strength of counter-selection against the parent phage. The number of plaques recovered on the ATc plate depends on the efficiency of both electroporation and recombination, but is usually from dozens up to several hundred. Individual plaques are picked from the ATc plate and screened by PCR to detect the mutant allele (Fig. 1e). The proportion of mutant plaques varies somewhat from 20–100% but typically requires screening of not more than a dozen plaques, which by PCR appear to be homogenous (Fig. 1e, Table 1). This is another departure from BRED, where these primary (1°) plaques are always mixtures of wild type and mutant alleles, requiring at least one more round of purification and screening. In contrast, re-plating and re-screening of secondary (2°) plaques generated by CRISPY-BRED confirms that all are mutant and that the primary plaques are homogenous (Fig. 1f, Table 1). Table 1 describes the generation of thirteen phages with deletions or insertions by CRISPY-BRED. Genome sequencing of four of these (Alma∆ori, LadyBird∆ori, Miko∆ori, and BuzzLyseyear∆43), and several other CRISPY-BRED recombinants have revealed no off-target mutations, suggesting that untargeted additional mutations are uncommon.

As shown in Fig. 1e, a small proportion of primary plaques can give the PCR product expected from the parent phage. These plaques reflect one of two outcomes: phenotypic escape of the parental genome from CRISPR-Cas selection, or non-recombineering-directed mutants (such as point mutations or small insertions/deletions) that reduce or eliminate CRISPR-selection but give parental-sized PCR products. Such mutations could pre-exist in the population, or result from repair events after post-CRISPR-Cas cleavage20.

The primary advantage of CRISPY-BRED over BRED is that it simplifies recovery of recombinants when recombination is less efficient. For the phages described in Table 1, recombination efficiencies were calculated for five of them. For BuzzLyseyear∆41 and BuzzLyseyear∆42, recombination occurred readily, with efficiencies of 2 × 10–1 and 3 × 10–1; to isolate these mutants, typical BRED would likely have been sufficient. However, phages Alma∆ori, LadyBird∆ori, and Miko∆repA were generated at efficiencies of 6 × 10–2, 8 × 10–3 and 2 × 10–3, respectively, such that CRISPR-Cas selection against parental phage permitted identification of the desired mutants in screening of a handful of plaques, rather than tens or hundreds otherwise.

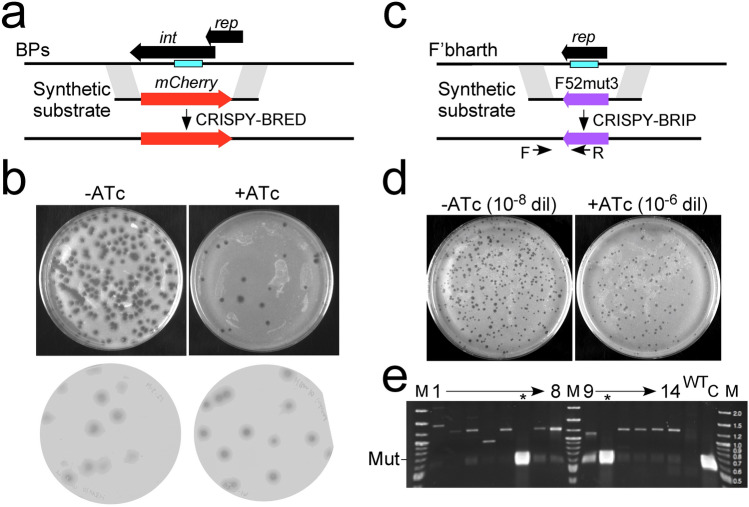

An additional example of CRISPY-BRED utility is the construction of fluorescent reporter phages, such as replacement of the immunity cassette (int-rep) of phage BPs with mCherry (Fig. 2a). Recombineering alone yields desired recombinant progeny at < 3% of the primary plaques, which would require extensive plaque screening (Fig. 2a, b). In contrast, > 90% of the plaques recovered by CRISPY-BRED are recombinant (Fig. 2b). Although in this instance fluorescence indicates the desired recombinants, this broadly reflects the benefit of CRISPY-BRED in constructions where recombinants are formed at low efficiency and a visual marker is not available. An example is provided by phiFW1, a capsid variant of phage Bxb1, which is viable but still rare among CRISPY-BRED progeny (Table 1). This is facilitated by strong counter-selection, and this derivative could not have been readily constructed using BRED alone (Table 1). We note that in this example, sequencing of non-recombineering directed survivors showed they are CRISPR-escape mutants with protospacer mutations or deletions (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Construction of engineered phages. (a) Scheme for constructing an mCherry reporter derivative of phage BPs. A synthetic substrate containing the mCherry gene and sequences flanking the BPs integrase-repressor (int-rep) was designed to replace the int-rep region. The blue box indicates the position of the protospacer and PAM site to which a sgRNA was designed. (b) Primary plaques (top) were recovered with (+ ATc) or without (-ATc) inducer following co-electroporation of the synthetic DNA substrate and phage BPs genomic DNA into M. smegmatis recombineering cells and plated with M. smegmatis psgRNA cells (see Fig. 1). Fluorescent images of the plaques (bottom) show similar numbers of mCherry recombinants (dark plaques) in the presence (+ ATc) or absence (−ATc) of inducer, but these represent > 90% of all plaques recovered when the sgRNA is expressed (+ ATc). (c) CRISPY-BRIP engineering, illustrated by construction of a recombinant Fionnbharth phage carrying Fruitloop 52mut3 (F52mut3). A synthetic substrate containing Fruitloop 52mut3 (F52mut3) and sequences flanking the repressor (rep) gene of Fionnbharth (F’bharth) was constructed such as to replace the Fionnbharth repressor gene. The blue box indicates the position of the protospacer and PAM site to which a sgRNA was designed. (d) Primary plaques were recovered with (+ ATc) or without (-ATc) inducer following electroporation of the synthetic DNA substrate into M. smegmatis recombineering cells, followed by infection of Fionnbharth particles, incubation to allow a round of lytic growth, and plating with M. smegmatis psgRNA cells (see Fig. 1); samples were diluted 108-fold or 106-fold and plated with or without ATc, respectively. (e) PCR of 14 plaques from the + ATc plate using forward and reverse primers (F and R, panel c) primers identified two recombinant plaques (asterisks); wild type phage (wt) and control (C) DNAs are shown. Original gel images are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1.

The combination of CRISPR-mediated counter-selection and recombineering also provides an opportunity for engineering phages that transfect inefficiently. Instead, phage genomes are provided by infection, as has been described previously to recombineer E. coli phages21. To evaluate this adaptation (BRIP: Bacteriophage Recombineering with Infectious Particles), we electroporated a synthetic DNA substrate into recombineering cells, infected these with phage particles, and incubated for 4.5 h to allow a cycle of lytic growth (Fig. 2c). The parental phage was Fionnbharth and the DNA substrate was designed to replace gene 47 (rep) with a gene 52 variant from Fruitloop (F52mut3)22. Plaque recovery was reduced by 100-fold when plated on solid medium with ATc (Fig. 2d), and PCR screening of 14 plaques identified two desired recombinants (Fig. 2e). Using the same configuration with CRISPY-BRED (co-electroporating gDNA and mutant substrate), 22 of 24 plaques screened were recombinant (Table 1). CRISPY-BRIP is less efficient than CRISPY-BRED, as expected, but useful when gDNA electroporation is inefficient. The CRISPR-mediated counter-selection greatly enhances the ease of recombinant identification.

CRISPY-BRED and CRISPY-BRIP have been used to construct many phage recombinants using different phages and different types of mutations (Table 1). Not all mutants are viable (data not shown), but viability is simpler to determine with CRISPY-BRED relative to BRED alone, because if CRISPR selection is strong, then all of the plaques recovered are either CRISPR escape mutants or the desired recombinants. For example, an attempt to modify the C-terminus of the tail tube protein (gp19) of Bxb1 resulted in 16/16 plaques with protospacer deletions but none of the desired mutant, suggesting it is non-viable (data not shown). The strength of CRISPR-mediated counter-selection is somewhat variable, and for some phages is minimal (< 10%); expression of anti-CRISPR proteins could account for this, but have yet to be identified in mycobacteriophages. A variety of PAM and sgRNA sequences could be evaluated to optimize counter-selection for a particular phage if needed.

Discussion

A potential limitation of CRISPY-BRED are the constraints imposed by PAM site choice. There is a 5 bp requirement for this Cas9 system and although many variants can be used17 these may not be present at precise locations where it is desired. For deletions and replacements where there is a reasonably long DNA region (> 300 bp) for targeting, this should not be problematic, but for point mutations and precise insertions (rather than replacements), PAM site choice could be limiting. Alternative CRISPR-Cas systems with more lax PAM requirements23 could be adapted for more facile CRISPY-BRED applications. A second potential disadvantage of CRISPY-BRED relative to BRED is the necessity to design, construct and transform the sgRNA plasmid. In practice, this does not take substantially longer than the design, synthesis, and amplification of the dsDNA substrate, and has the substantial advantage of simplifying recombinant identification.

We note that the magnitude of phage interference by CRISPR-Cas varies substantially depending on the phage and the sgRNA used (Table 1). The reason for this is not clear but presumably reflects at least in part the efficiency of PAM site recognition17; however, it could also potentially be influenced by phage-encoded anti-CRISPR genes24. It seems unlikely that plaques escaping selection have altered or mutant protospacer or PAM sequences, when plaquing is only reduced 100-fold. However, even a modest (100-fold) reduction in plaquing with CRISPR-selection greatly increases the ease with which desired recombinants can be identified.

CRISPY-BRED and CRISPY-BRIP should be applicable to bacteriophages for a variety of other bacterial hosts. CRISPR-Cas systems are readily adaptable11 and counter-selection can be relatively poor (two orders of magnitude reduction) and still be effective for mutant enrichment. Recombineering systems may be more limiting for other bacteria, but many phages code for their own lambda Red-like or RecET-like recombination systems, and can be co-opted for recombineering system development as for the mycobacteria9. Some phages-especially those with relatively large genomes-do not efficiently transfect their bacterial hosts, and the CRISPY-BRIP adaptation offers a useful approach to precisely and efficiently engineer these phages.

Methods

Detailed methods for CRISPY-BRED and CRISPY-BRIP strategies are described in the online Methods section.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We thank Becky Garlena for excellent technical assistance and Travis Mavrich for providing phage phiTM45. This work was supported by grants 1R35 GM131729 and 1R21AI151264 from the National Institute of Health, and 54308198 and GT12053 from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Author contributions

K.S.W., C.G.B., R.M.D., C.C.K., K. G. F. and G. F. H. designed the experiments, K.S.W., C.G.B., R.M.D., C.C.K., K. G. F., H. A. G., A. M. D. and K. M. Z. performed the experiments and interpreted the data, J.R. provided critical reagents and input, K. S. W. and G. F. H wrote the manuscript, and all authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Data availability

The genome sequences of mycobacteriophages referenced here are available at phagesdb.org.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Katherine S. Wetzel, Carlos A. Guerrero-Bustamante, Rebekah M. Dedrick.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-86112-6.

References

- 1.Hatfull GF. Dark matter of the biosphere: the Amazing World of bacteriophage diversity. J. Virol. 2015;89:8107–8110. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01340-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Payaslian F, Gradaschi V, Piuri M. Genetic manipulation of phages for therapy using BRED. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2020;68:8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2020.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harada LK, et al. Biotechnological applications of bacteriophages: State of the art. Microbiol. Res. 2018;212–213:38–58. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2018.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dedrick RM, et al. Engineered bacteriophages for treatment of a patient with a disseminated drug-resistant Mycobacterium abscessus. Nat. Med. 2019;25:730–733. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0437-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marinelli LJ, et al. BRED: a simple and powerful tool for constructing mutant and recombinant bacteriophage genomes. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e3957. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pan YJ, et al. Klebsiella phage PhiK64-1 encodes multiple depolymerases for multiple host capsular types. J. Virol. 2017;91:10. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02457-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feher T, Karcagi I, Blattner FR, Posfai G. Bacteriophage recombineering in the lytic state using the lambda red recombinases. Microb. Biotechnol. 2012;5:466–476. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7915.2011.00292.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shin H, Lee JH, Yoon H, Kang DH, Ryu S. Genomic investigation of lysogen formation and host lysis systems of the Salmonella temperate bacteriophage SPN9CC. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014;80:374–384. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02279-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Kessel JC, Hatfull GF. Mycobacterial recombineering. Methods Mol. Biol. 2008;435:203–215. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-232-8_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gentile GM, et al. More evidence of collusion: a new prophage-mediated viral defense system encoded by mycobacteriophage Sbash. MBio. 2019 doi: 10.1128/mBio.00196-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doudna JA, Charpentier E. Genome editing. The new frontier of genome engineering with CRISPR-Cas9. Science. 2014;346:1258096. doi: 10.1126/science.1258096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kiro R, Shitrit D, Qimron U. Efficient engineering of a bacteriophage genome using the type I-E CRISPR-Cas system. RNA Biol. 2014;11:42–44. doi: 10.4161/rna.27766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martel B, Moineau S. CRISPR-Cas: an efficient tool for genome engineering of virulent bacteriophages. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:9504–9513. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Box AM, McGuffie MJ, O'Hara BJ, Seed KD. Functional analysis of bacteriophage immunity through a Type I-E CRISPR-cas system in vibrio cholerae and its application in bacteriophage genome engineering. J. Bacteriol. 2016;198:578–590. doi: 10.1128/JB.00747-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hatoum-Aslan A. Phage genetic engineering using CRISPR(-)Cas systems. Viruses. 2018 doi: 10.3390/v10060335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang W, Bikard D, Cox D, Zhang F, Marraffini LA. RNA-guided editing of bacterial genomes using CRISPR-Cas systems. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013;31:233–239. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rock JM, et al. Programmable transcriptional repression in mycobacteria using an orthogonal CRISPR interference platform. Nat. Microbiol. 2017;2:16274. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meijers AS, et al. Efficient genome editing in pathogenic mycobacteria using Streptococcus thermophilus CRISPR1-Cas9. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2020;124:101983. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2020.101983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee MH, Pascopella L, Jacobs WR, Jr, Hatfull GF. Site-specific integration of mycobacteriophage L5: integration-proficient vectors for Mycobacterium smegmatis, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and bacille Calmette-Guerin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1991;88:3111–3115. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.8.3111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tao P, Wu X, Rao V. Unexpected evolutionary benefit to phages imparted by bacterial CRISPR-Cas9. Sci. Adv. 2018;4:4134. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aar4134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oppenheim AB, Rattray AJ, Bubunenko M, Thomason LC, Court DL. In vivo recombineering of bacteriophage lambda by PCR fragments and single-strand oligonucleotides. Virology. 2004;319:185–189. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2003.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ko CC, Hatfull GF. Mycobacteriophage Fruitloop gp52 inactivates Wag31 (DivIVA) to prevent heterotypic superinfection. Mol. Microbiol. 2018 doi: 10.1111/mmi.13946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pausch P, et al. CRISPR-CasPhi from huge phages is a hypercompact genome editor. Science. 2020;369:333–337. doi: 10.1126/science.abb1400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Borges AL, Davidson AR, Bondy-Denomy J. The discovery, mechanisms, and evolutionary impact of anti-CRISPRs. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2017 doi: 10.1146/annurev-virology-101416-041616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wetzel KS, Aull HG, Zack KM, Garlena RA, Hatfull GF. Protein-mediated and RNA-based origins of replication of extrachromosomal mycobacterial prophages. mBio. 2020 doi: 10.1128/mBio.00385-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mavrich TN, Hatfull GF. Evolution of superinfection immunity in cluster a mycobacteriophages. MBio. 2019 doi: 10.1128/mBio.00971-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The genome sequences of mycobacteriophages referenced here are available at phagesdb.org.