Abstract

Purpose

Ixekizumab is a high-affinity monoclonal antibody that selectively targets interleukin-17A. The objective of this study was to assess the long-term efficacy and safety (to week 156) of ixekizumab in patients with active psoriatic arthritis and inadequate response or intolerance to one or two tumor necrosis factor inhibitors.

Methods

In the SPIRIT-P2 study (ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT02349295), patients were randomized to placebo or ixekizumab 80 mg every 4 weeks (IXE Q4W) or every 2 weeks (IXE Q2W) following a 160-mg starting dose. During the extension period (weeks 24–156), patients maintained their original ixekizumab dose, and placebo patients received IXE Q4W or IXE Q2W (1:1). Exposure-adjusted incidence rates (IRs) per 100 patient-years (PY) are presented.

Results

Of 363 patients enrolled in the study, 310 entered the extension period. In all patients treated with IXE Q4W and IXE Q2W at week 0, responses persisted to week 156. At week 156, clinical responses (observed) in patients treated with IXE Q4W and IXE Q2W were assessed [American College of Rheumatology (ACR) response criteria and minimal disease activity (MDA) criteria]: 84 and 85% showed 20% improvement (ACR20); 60 and 58% showed 50% improvement (ACR50); 35 and 47% showed 70% improvement (ACR70), respectively; and 48 and 54% showed MDA. Placebo patients re-randomized to ixekizumab also demonstrated sustained efficacy, as measured by ACR and MDA responses. In the All Ixekizumab Exposure Safety Population (n = 337), with 644 PY of ixekizumab exposure, treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were reported by 286 patients (44.4 IR). The most common TEAEs were upper respiratory tract infection (9.80 IR), nasopharyngitis (8.2 IR), sinusitis (6.2 IR), and bronchitis (4.5 IR). Serious adverse events were reported by 42 (6.5 IR) patients (included 3 deaths and 10 infections).

Conclusion

In this 156-week study of ixekizumab, improvements in signs and symptoms of psoriatic arthritis and the safety profile remained consistent with those in previous reports.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02349295.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s40744-020-00261-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Efficacy, Interleukin-17A, Ixekizumab, Psoriatic arthritis, Safety

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| In the phase 3 SPIRIT-P2 trial of 363 patients with active psoriatic arthritis (PsA) who had an inadequate response or an intolerance to one or two tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors, ixekizumab improved the signs and symptoms of PsA with superiority to placebo at 24 weeks. |

| Furthermore, clinical improvements persisted up to 1 year during the extension period. |

| The objective of this study was to assess the long-term efficacy and safety (to week 156) of ixekizumab in the SPIRIT-P2 trial. |

| What was learned from this study? |

| The significant improvements observed with ixekizumab at week 24 in SPIRIT-P2 were sustained for up to 156 weeks across multiple endpoints in patients with inadequate response or intolerance to one or two TNF inhibitors and adverse events were consistent with the known safety profile of ixekizumab. |

| The findings from SPIRIT-P2 suggest that ixekizumab is a long-term treatment option for patients with PsA who have shown intolerance or had an inadequate response to one or two TNF inhibitors. |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including a summary slide, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.13241459.

Introduction

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is an inflammatory, chronic, immune-mediated disorder present in 20–30% of patients with psoriasis [1, 2] and in 0.05–1% of the general population [2]. PsA can lead to disease progression with musculoskeletal and extra-articular manifestations [3], resulting in impaired function, reduced quality of life, and increased mortality [3, 4]. Treatments for PsA include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, intra-articular or systemic glucocorticoids, conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (csDMARDs), and biologic agents, such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors [5, 6]. Although TNF inhibitors are often effective, 30–40% of patients with PsA have only a partial response or become resistant or intolerant to treatment [7, 8]. Furthermore, patients with an inadequate response to their first TNF inhibitor generally have lower response on their second or third TNF inhibitor [9]. For this substantial proportion of patients with prior inadequate response, intolerance, or contraindication to TNF inhibitors, well-tolerated treatments targeting an alternative mechanism of action and with persistent efficacy are of significant clinical value [10].

Ixekizumab is a high-affinity monoclonal antibody that selectively targets interleukin (IL)-17A, a pro-inflammatory cytokine that mediates joint damage [11]. Ixekizumab is approved for use in active PsA, moderate-to-severe psoriasis, pediatric psoriasis (≥ 6 years with body weight ≥ 25 kg), ankylosing spondylitis, and non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis [12, 13].

Persistent efficacy over 3 years was observed in the SPIRIT-P1 trial, a phase 3 trial investigating ixekizumab treatment in patients with active PsA who had not previously received biologic therapy for PsA or psoriasis [14]. SPIRIT-P2 is a phase 3 trial of 363 patients with active PsA who had an inadequate response or an intolerance to one or two TNF inhibitors. In this study, ixekizumab improved the signs and symptoms of PsA with superiority to placebo (PBO) at 24 weeks [15]. Furthermore, clinical improvements persisted up to 1 year during the extension period [16]. In this article, the authors report their evaluation of the long-term efficacy and safety profile of ixekizumab in patients with prior inadequate response or intolerance to TNF inhibitors through 3 years of treatment in SPIRIT-P2.

Methods

Patients

Complete inclusion and exclusion criteria for SPIRIT-P2 have been reported previously [15]. Briefly, study participants were adults meeting the Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis (CASPAR) with active PsA [17], defined as at least three of 68 tender and three of 66 swollen joints at screening and baseline, with active or documented history of plaque psoriasis. Eligible patients had been treated previously with at least one csDMARD and had an inadequate response (based on a minimum of 12 weeks of therapy) or intolerance to one or two TNF inhibitors. Reasons for TNF inhibitor failure were not systematically collected.

Study Design

SPIRIT-P2 is a phase 3, randomized, double-blind, PBO-controlled clinical study that comprised two treatment periods: the double-blind (weeks 0–24) and extension (weeks 24–156) periods. The methods have been reported in detail previously [in brief, see the electronic supplementary material (ESM) file] [15, 18]. Patients who participated in the extension periods received ixekizumab 80 mg every 2 weeks (IXE Q2W) or every 4 weeks (IXE Q4W) until study completion or treatment discontinuation. Starting at week 32, and at all subsequent visits during the extension period, patients were discontinued from study treatment for lack of efficacy if they failed to demonstrate ≥ 20% improvement from baseline in tender and swollen joint counts.

The trial described was conducted in accordance with the Good Clinical Practice guidelines of the International Conference on Harmonisation and with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol and documentation was approved by the institutional review board or independent ethics committee at each investigational site prior to patient screening (see ESM). All patients provided written informed consent prior to receiving investigational product or undergoing study procedures. SPIRIT-P2 is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02349295).

Outcomes

Prespecified efficacy and health outcomes measures were described previously [15, 16] and include the percentage of patients achieving the following responses: American College of Rheumatology (ACR) response criteria improvement of 20%, 50%, or 70% from baseline (ACR20/50/70); Leeds Enthesitis Index (LEI = 0) and Leeds Dactylitis Index-Basic (LDI-B = 0); ≥ 0.35-point improvement in Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index (HAQ-DI) score of [minimal clinically important difference (MCID)]; as well as skin and nail outcomes, minimal disease activity (MDA; ≥ 5 of 7 of the Coates criteria [19]), and patient-reported outcomes.

Safety outcomes included the assessment of adverse events (AEs), serious adverse events (SAEs), and findings from physical examinations, vital signs, and laboratory studies. Adverse events of special interest (AESIs) were prespecified and previously discussed [20]. Additional details on the efficacy and safety outcomes assessed are available in the ESM file.

Statistical Analyses

Power calculations for the primary endpoint have been described previously [15]. The Extension Period Population (EPP) included patients originally randomized to PBO who were inadequate responders at week 16 and any patients remaining on PBO at week 24, all of who were re-randomized 1:1 to receive IXE Q2W or IXE Q4W (PBO/IXE Q2W and PBO/IXE Q4W groups, respectively) for the duration of the study or until discontinuation. Efficacy analyses were conducted on the intent-to-treat (ITT) population (ad hoc) randomly assigned to IXE Q2W or IXE Q4W at week 0 and on the EPP, which included all patients who received at least one dose of ixekizumab during the extension period (weeks 24–156). Efficacy results are summarized through week 156 as the number and percentage of patients meeting response criteria for categorical variables or as the mean (standard deviation) change from baseline for continuous variables. There were no comparisons made between treatment groups. For efficacy variables, data were reported as observed. Patients who received rescue therapy at week 16 were imputed as nonresponders (NRI) between weeks 16 and 24. As secondary analyses, missing data were imputed using modified NRI (mNRI) for categorical outcomes or modified baseline observation carried forward (mBOCF) for continuous efficacy variables at all other timepoints.

Safety analyses were performed on the All Ixekizumab Exposure Safety Population (AIESP; IXE Q4W, IXE Q2W), which included all patients who received at least one dose of ixekizumab at any time during the 156-week study period, with baseline defined as the time of first exposure to ixekizumab. Safety results were summarized as the frequency and incidence rate (IR) per 100 patient-years (PY) of exposure to ixekizumab, using the entire duration of exposure for the treatment period and expressed as a number of unique patients within a particular category of event.

Additional statistical methods, including detailed definitions for imputation methods, are described in the ESM. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 or higher (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Patients

Of 363 patients randomized to the PBO (n = 118), IXE Q4W (n = 122), or IXE Q2W (n = 123) study arms, 314 patients (87%) completed the double-blind treatment period and 310 entered the extension treatment period (weeks 24–156; ESM Fig. S1), as previously described [15]. Of the 310 patients who entered the extension treatment period, 168 (54.2%) completed 156 weeks of treatment. Discontinuation due to lack of efficacy was the most common reason for patient discontinuation (94 patients, 30.3%), with 75.5% of discontinuations due to the mandatory discontinuation criteria (MDC; failure to demonstrate ≥ 20% improvement from baseline in tender and swollen joint counts [ACR20]) from baseline beginning at week 32. The majority of patients who discontinued due to MDC did so within the first year of treatment. At week 32, 23 of 310 patients (7.4%) discontinued due to MDC; between weeks 36 and 52, an additional 37 (11.9%) patients discontinued due to MDC; a further nine (2.9%) and two (0.6%) patients discontinued due to MDC between weeks 52 and 108 and weeks 108 and 156, respectively.

Baseline characteristics for the ITT population [15] and for those who entered the extension period [16] have been previously published. In general, demographics and clinical characteristics for the ITT population were well balanced among the study arms. Demographics and clinical characteristics for the EPP were comparable to those for the ITT population. Briefly, patients entering the extension period were, on average, 51.8 years old, the majority were white (92%), and slightly more than half were female (53%). Mean tender joint count was 23 (of 68 joints) and swollen joint count was 12 (of 66 joints). Within the EPP, 55% of patients were inadequate responders to one TNF inhibitor, 37% of patients were inadequate responders to two TNF inhibitors, and 9% of patients showed intolerance to a TNF inhibitor [16].

Efficacy Outcomes

Endpoints for the ITT population at week 108 and week 156 are summarized in Table 1 (observed) and ESM Table S1 (mNRI). As observed, ACR20, ACR50, and ACR70 response rates in the ITT population were 84, 60, and 35%, respectively, in the IXE Q4W group and 85, 58, and 47%, respectively, in the IXE Q2W group at week 156 (Fig. 1; Table 1). By mNRI analysis, the ACR20, ACR50, and ACR70 response rates were sustained to week 156: 55, 40, and 23% of IXE Q4W-treated patients and 48, 34, and 25% of IXE Q2W-treated patients, respectively (ESM Table S1; Fig. 1). At week 156, patients on PBO who were re-randomized to ixekizumab at week 16 or 24 demonstrated ACR responses relatively comparable with those of patients receiving continuous IXE treatment. ACR20, ACR50, and ACR70 response rates were 54, 41, and 24% of PBO/IXE Q4W-treated patients and 47, 36, and 12% of PBO/IXE Q2W-treated patients, respectively (ESM Table S2).

Table 1.

Overview of efficacy at week 108 and week 156 (ITT population, observed data)

| Efficacy outcomes | Week 108 | Week 156 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IXE Q4W (n = 122) | IXE Q2W (n = 123) | IXE Q4W (n = 122) | IXE Q2W (n = 123) | |

| Response rate, n/Nx (%) | ||||

| ACR20 | 64/78 (82.1) | 52/62 (83.9) | 56/67 (83.6) | 45/53 (84.9) |

| ACR50 | 47/74 (63.5) | 36/62 (58.1) | 39/65 (60.0) | 31/53 (58.5) |

| ACR70 | 25/79 (31.7) | 26/61 (42.6) | 24/68 (35.3) | 24/51 (47.1) |

| PASI 75a | 39/47 (83.0) | 29/32 (90.6) | 34/43 (79.1) | 27/28 (96.4) |

| PASI 90a | 33/47 (70.2) | 24/32 (75.0) | 28/43 (65.1) | 21/28 (75.0) |

| PASI 100a | 23/47 (48.9) | 21/32 (65.6) | 22/43 (51.2) | 18/28 (64.3) |

| NAPSI = 0b | 37/62 (60.0) | 24/40 (60.0) | 33/55 (60.0) | 24/35 (68.6) |

| LEI = 0c | 30/44 (68.2) | 28/43 (65.1) | 24/38 (63.2) | 30/38 (79.0) |

| LDI-B = 0d | 17/17 (100.0) | 12/13 (92.3) | 17/17 (100.0) | 11/12 (91.7) |

| MDAe | 38/80 (47.5) | 32/63 (50.8) | 33/69 (47.8) | 29/54 (53.7) |

| VLDAe | 14/80 (17.5) | 11/63 (17.5) | 16/70 (22.9) | 11/55 (20.0) |

| DAPSA LDA (> 4 and ≤ 14) | 36/78 (46.2) | 27/63 (42.9) | 28/69 (40.6) | 19/54 (35.2) |

| DAPSA remission (≤ 4) | 17/78 (21.8) | 19/63 (30.2) | 23/69 (33.3) | 20/54 (37.0) |

| HAQ-DI ≥ 0.35f | 39/70 (55.7) | 35/56 (62.5) | 37/60 (61.7) | 30/50 (60.0) |

| Itch NRS = 0a | 10/47 (21.3) | 12/32 (37.5) | 12/42 (28.6) | 11/27 (40.7) |

| Change from baseline, mean (SD) | ||||

| NAPSIb | − 15.9 (20.5) | − 19.7 (20.1) | − 16.6 (21.5) | − 19.6 (20.3) |

| LEIc | − 2.0 (2.1) | − 2.3 (1.6) | − 1.8 (1.8) | − 2.5 (1.6) |

| LDI-Bd | − 28.7 (21.2) | − 54.7 (37.0) | − 28.7 (21.2) | − 54.7 (40.2) |

| DAPSA | − 38.1 (22.0) | − 38.5 (22.7) | − 38.7 (23.3) | − 38.9 (23.5) |

| DAS28-CRP | − 2.7 (1.2) | − 2.4 (1.1) | − 2.8 (1.3) | − 2.4 (1.1) |

| Joint pain VAS | − 33.4 (26.4) | − 34.3 (25.8) | − 37.9 (25.9) | − 35.1 (26.0) |

| HAQ-DI | − 0.4 (0.6) | − 0.5 (0.6) | − 0.5 (0.6) | − 0.5 (0.6) |

| Itch NRS | − 3.0 (3.0) | − 4.2 (3.3) | − 3.2 (3.1) | − 4.4 (3.5) |

| Fatigue severity NRS | − 2.1 (2.8) | − 3.3 (2.9) | − 2.4 (2.9) | − 2.5 (2.9) |

| EQ-5D VAS | 16.0 (21.8) | 18.8 (17.8) | 18.6 (20.1) | 16.9 (18.7) |

| WPAI-SHP | ||||

| Absenteeism | − 3.9 (17.9) | 2.1 (38.5) | − 5.6 (23.4) | 0.8 (30.5) |

| Presenteeism | − 30.0 (24.7) | − 26.0 (24.0) | − 28.3 (31.0) | − 25.0 (20.2) |

| Work productivity | − 29.9 (26.7) | − 26.9 (27.9) | − 26.8 (35.3) | − 18.7 (27.1) |

| Activity impairment | − 27.3 (28.3) | − 24.3 (28.1) | − 25.4 (30.0) | − 24.0 (26.4) |

| SF-36 MCS | 3.8 (11.4) | 4.9 (10.0) | 4.4 (10.5) | 5.6 (8.2) |

| SF-36 PCS | 8.1 (10.6) | 10.0 (10.3) | 9.1 (9.8) | 10.3 (9.0) |

ACR American College of Rheumatology, BSA body surface area, DAPSA Disease Activity in Psoriatic Arthritis, DAS28-CRP 28-joint DAS using C-reactive protein, EQ-5D EuroQol 5-dimensions, HAQ-DI Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index, ITT intent-to-treat; IXE Q2W ixekizumab 80 mg every 2 weeks, IXE Q4W ixekizumab 80 mg every 4 weeks, LDA low disease activity, LDI-B Leeds Dactylitis Index-Basic, LEI Leeds Enthesitis Index, MCS mental component summary, MDA minimal disease activity, NAPSI Nail Psoriasis Severity Index, NRS numeric rating scale, Nx number of patients with nonmissing data, PASI Psoriasis Area and Severity Index, PCS physical component summary, SD standard deviation, SF-36 Medical Outcomes Survey Short Form (36 items), VAS visual analog scale, VLDA very low disease activity, WPAI-SHP Work Productivity Activity Impairment-Specific Health Problem

aAmong patients with psoriasis and BSA involvement of ≥ 3% at baseline

bAmong patients with baseline fingernail involvement

cAmong patients with baseline LEI > 0

dAmong patients with baseline LDI-B > 0

eMDA defined as achieving 5/7 of the following MDA components: tender joint count ≤ 1, swollen joint count ≤ 1, PASI ≤ 1 or BSA ≤ 3%, patient pain VAS ≤ 15, patient global disease activity VAS ≤ 20, HAQ-DI ≤ 0.5, and ≤ 1 tender entheseal points. VLDA is defined as achieving 7/7 of of these components

fAmong patients with baseline HAQ-DI ≥ 0.35

Fig. 1.

American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and minimal disease activity (MDA) responses up to week 156, as observed and modified nonresponder imputation (mNRI). Intent-to-treat population randomized to ixekizumab at week 0. Starting at week 32, and at all subsequent visits during the extension period, patients were discontinued from study treatment if they failed to demonstrate ≥ 20% improvement from baseline in tender (TJC) and swollen (SJC) joint counts. MDA defined as achieving five of the seven following MDA components: TJC ≤ 1, SJC ≤ 1, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index ≤ 1 or body surface area ≤ 3%, patient pain visual analog scale (VAS) ≤ 15, patient global disease activity VAS ≤ 20, Health Assessment Questionnaire–Disability Index ≤ 0.5, and ≤ 1 tender entheseal points. ACR20/50/70 ACR response criteria improvement of 20, 50, or 70%, respectively, IXE Q2W ixekizumab 80 mg every 2 weeks, IXE Q4W ixekizumab 80 mg every 4 weeks

At week 156, MDA (5 of 7 MDA components) was achieved by approximately 50% of the IXE Q4W- and IXE Q2W-treated patients (Fig. 1). Very low disease activity (7 of 7 MDA components) response rates were also numerically similar between the IXE Q4W- and IXE Q2W-treated patients (23 and 20%, respectively; ESM Fig. S2). As measured by Disease Activity Index for Psoriatic Arthritis (DAPSA), at week 156, 41% of IXE Q4W- and 35% of IXE Q2W-treated patients achieved low disease activity (LDA) and 33% of IXE Q4W- and 37% of IXE Q2W-treated patients achieved remission (ESM Fig. S2). As determined by a 28-joint Disease Activity Score using C-reactive protein < 2.6, at week 156, 67% of IXE Q4W-treated patients and 59% of IXE Q2W-treated patients had achieved remission (ESM Fig. S2). Response rates for composite endpoints were lower but followed a similar pattern using the more conservative mNRI approach (ESM Fig. S2).

In patients with baseline dactylitis (LDI-B > 0) and baseline enthesitis (LEI > 0), IXE Q4W- and IXE Q2W-treated patients demonstrated persistent reductions through week 156 (Fig. 2). Complete resolution of dactylitis was achieved by 100% of IXE Q4W- and 91.7% of IXE Q2W-treated patients; however, observed data from the ITT population with baseline LDI-B > 0 are available for only 17 and 12 patients in the IXE Q4W and IXE Q2W groups, respectively. Complete resolution of enthesitis was achieved by 63% of IXE Q4W- and 79% of IXE Q2W-treated patients (Table 1). Changes from baseline in LDI-B and LEI followed similar patterns when missing data were imputed with mBOCF (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Enthesitis, dactylitis, and nail psoriasis up to week 156 [observed and modified baseline observation carried forward (mBOCF)]. Intent-to-treat population randomized to ixekizumab at week 0. Leeds Enthesitis Index (LEI) and Leeds Dactylitis Index–Basic (LDI-B) were assessed in patients with baseline LEI score > 0 and LDI-B score > 0, respectively. Nail Area Psoriasis Severity Index (NAPSI) was assessed in patients with fingernail psoriasis at baseline. Starting at week 32, and all subsequent visits during the extension, patients not demonstrating ≥ 20% improvement from baseline in both tender and swollen joint counts were discontinued . IXE Q2W ixekizumab 80 mg every 2 weeks, IXE Q4W ixekizumab 80 mg every 4 weeks

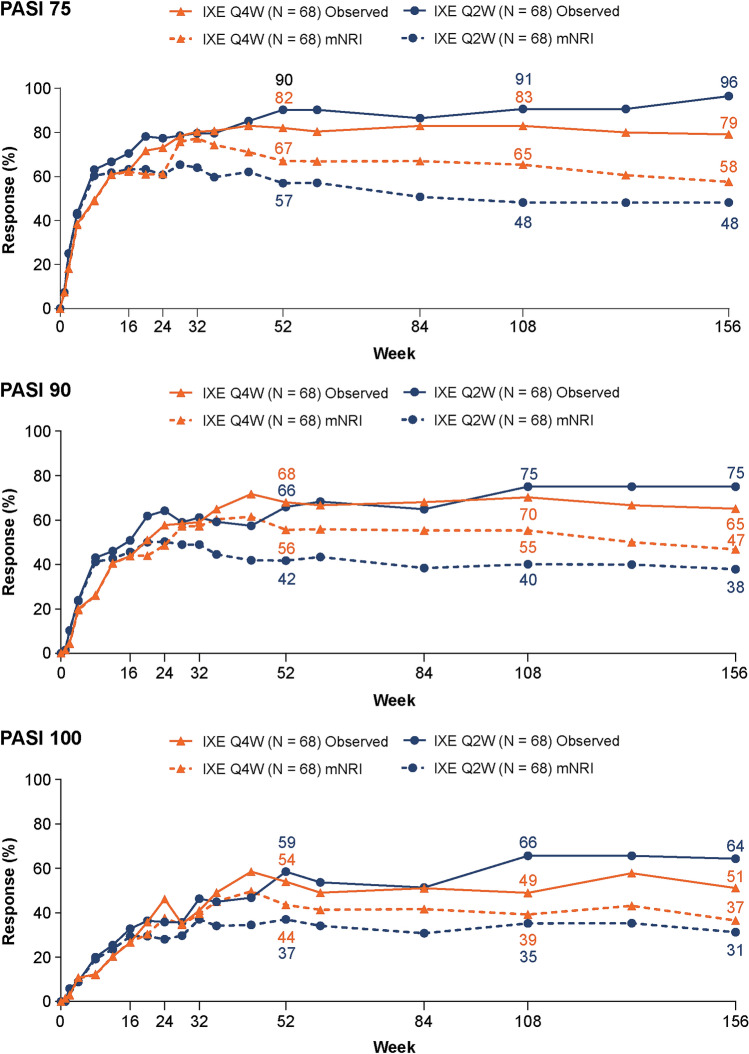

Among patients with baseline psoriasis, body surface area (BSA) involvement ≥ 3%, 79% of patients receiving IXE Q4W and 96% of those receiving IXE Q2W achieved at least a 75% reduction in the baseline Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI 75); 65 and 75% reached PASI 90; and 51 and 64% attained PASI 100, respectively, at week 156 (Table 1). PASI responses achieved at week 24 were maintained through the extension period (Fig. 3). Complete resolution of itch [Itch numeric rating scale (NRS) = 0] in the ITT population with baseline psoriatic lesions involving ≥ 3% BSA was achieved by 29 and 41% of IXE Q4W- and IXE Q2W-treated patients, respectively, at week 156 (Table 1). In patients with baseline fingernail psoriasis, measured by a modified version of the Nail Psoriasis Severity Index (NAPSI) that includes only fingernails (score range 0–40), improvements in NAPSI observed at week 24 persisted through week 156 (Fig. 2). At week 156, 60 and 69% of patients treated with IXE Q4W and IXE Q2W, respectively, achieved complete resolution of fingernail psoriasis (Table 1).

Fig. 3.

Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) responses (observed and with mNRI). Intent-to-treat population randomized to ixekizumab at week 0 with ≥ 3% body surface area of disease at baseline. Starting at week 32, and at all subsequent visits during the extension period, patients were discontinued from study treatment if they failed to demonstrate ≥ 20% improvement from baseline in tender and swollen joint counts. IXE Q2W ixekizumab 80 mg every 2 weeks, IXE Q4W ixekizumab 80 mg every 4 weeks, PASI 75/90/100 75/90/100% improvement from baseline on the PASI, respectively

At week 156, improvements in physical function measured by HAQ-DI MCID (≥ 0.35 improvement from baseline) occurred in 62% of IXE Q4W- and 60% of IXE Q2W-treated patients (with baseline HAQ-DI ≥ 0.35) (Table 1). Improvements from baseline in HAQ-DI observed in the double-blind period persisted through 156 weeks of extension-period ixekizumab treatment (Fig. 4). Responses in additional patient-reported quality-of-life outcomes, including Fatigue NRS, EuroQol 5-dimensions visual analog scale (VAS), and Work Productivity Activity Impairment-Specific Health Problem, were also sustained through week 156 (Table 1). On average, about 10-point improvements from baseline in the Medical Outcomes Survey Short Form (36 items) (SF-36)–physical component summary and approximately 5-point improvements in the SF-36–mental component summary were reported by IXE-treated patients at week 156 (Table 1). Improvements in the individual domains of the SF-36 at week 108 and week 156 were also observed (ESM Table S3). Improvements in the SF-36 vitality domain were consistent with improvements in the Fatigue NRS. Similarly, improvements in the SF-36 bodily pain domain correlated with improvements in joint pain VAS, with an approximate 37-point improvement from baseline in joint pain at week 156 (Table 1).

Fig. 4.

Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index (HAQ-DI) minimal clinically important difference (MCID; observed and with mNRI) and HAQ-DI change from baseline (observed and mBOCF) up to week 156. Intent-to-treat population randomized to ixekizumab at week 0. MCID was assessed in patients with baseline HAQ-DI ≥ 0.35. Starting at week 32, and all subsequent visits during the extension period, patients not demonstrating ≥ 20% improvement from baseline in tender and swollen joint counts were discontinued. IXE Q2W ixekizumab 80 mg every 2 weeks, IXE Q4W ixekizumab 80 mg every 4 weeks

Safety

A total of 337 patients with prior intolerance or inadequate response to one or two TNF inhibitors were included through the 3-year extension period of SPIRIT-P2. Patients treated with IXE Q4W (n = 168) and IXE Q2W (n = 169) accounted for 345.1 and 298.9 PY of exposure, respectively (Table 2). Overall, 85% of patients who received at least one dose of study medication reported one or more treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) throughout 3 years of the study, with an IR of 44.4, with a similar distribution of patients in each treatment group (IXE Q4W, n = 141; IXE Q2W, n = 145). Most TEAEs were mild or moderate in severity. The most common TEAEs (occurring in ≥ 5% of patients in the AIESP; n = 337; IR per 100 PY) were upper respiratory tract infection (IXE Q4W, 9.0 IR; IXE Q2W, 10.7 IR), nasopharyngitis (IXE Q4W, 8.4 IR; IXE Q2W, 8.0 IR), sinusitis (IXE Q4W, 6.4 IR; IXE Q2W, 6.0 IR), bronchitis (IXE Q4W, 4.1 IR; IXE Q2W, 5.0 IR), and urinary tract infection (IXE Q4W, 4.6 IR; IXE Q2W, 2.7 IR).

Table 2.

Adverse events per 100 patient-years of exposure

| Incidence ratea | IXE Q4W (n = 168) | IXE Q2W (n = 169) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (345.1 PY) | Years 0–1 (143.4 PY) | Years 1–2 (113.2 PY) | Years 2–3 (87.4 PY) | Overall (298.9 PY) | Years 0–1 (133.9 PY) | Years 1–2 (92.9 PY) | Years 2–3 (71.8 PY) | |

| TEAEs |

141 (83.9) [40.9] |

133 (79.2) [92.7] |

84 (50.0) [74.2] |

57 (33.9) [65.2] |

145 (85.8) [48.5] |

136 (80.5) [101.6] |

72 (42.6) [77.5] |

48 (28.4) [66.8] |

| Mild |

41 (24.4) [11.9] |

60 (35.7) [41.8] |

40 (23.8) [35.3] |

26 (15.5) [29.7] |

43 (25.4) [14.4] |

54 (32.0) [40.3] |

24 (14.2) [25.8] |

22 (13.0) [30.6] |

| Moderate |

85 (50.6) [24.6] |

66 (39.3) [46.0] |

37 (22.0) [32.7] |

27 (16.1) [30.9] |

74 (43.8) [24.8] |

69 (40.8) [51.5] |

34 (20.1) [36.6] |

24 (14.2) [33.4] |

| Severe |

15 (8.9) [4.3] |

7 (4.2) [4.9] |

7 (4.2) [6.2] |

4 (2.4) [4.6] |

28 (16.6) [9.4] |

13 (7.7) [9.7] |

14 (8.3) [15.1] |

2 (1.2) [2.8] |

| Discontinuations due to adverse eventb |

17 (10.1) [4.9] |

7 (4.2) [4.9] |

7 (4.2) [6.2] |

3 (1.8) [3.4] |

21 (12.4) [7.0] |

14 (8.3) [10.5] |

7 (4.1] [7.5] |

0 |

| Serious adverse eventsb |

19 (11.3) (5.5) |

7 (4.2) [4.9] |

10 (6.0) [8.8] |

5 (3.0) [5.7] |

23 (13.6) [7.7] |

9 (5.3) [6.7] |

12 (7.1) [12.9] |

3 (1.8) [4.2] |

| Deaths |

1 (0.6) [0.3] |

0 | 0 |

1 (0.6) [1.1] |

2 (1.2) [0.7] |

0 |

2 (1.2) [2.2] |

0 |

| Infections |

112 (66.7) [32.5] |

91 (54.2) [63.4] |

52 (31.0) [45.9] |

32 (19.0) [36.6] |

101 (59.8) [33.8] |

84 (49.7) [62.7] |

49 (29.0) [52.8] |

31 (18.3) [43.2] |

| Serious infections |

5 (3.0) [1.4] |

2 (1.2) [1.4] |

2 (1.2) [1.8] |

1 (0.6) (0.6) [1.1] |

5 (3.0) (3.0) [1.7] |

3 (1.8) [2.2] |

3 (1.8) [3.2] |

0 |

| Allergic reactions and hypersensitivities |

17 (10.1) [4.9] |

14 (8.3) [9.8] |

3 (1.8) [2.7] |

2 (1.2) [2.3] |

16 (9.5) [5.4] |

13 (7.7) [9.7] |

4 (2.4) [4.3] |

1 (0.6) [1.4] |

| Anaphylaxis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Injection-site reactions |

25 (14.9) [7.2] |

23 (13.7) [16.0] |

4 (2.4) [3.5] |

1 (0.6) [1.1] |

42 (24.9) [14.1] |

42 (24.9) [31.4] |

5 (3.0) [5.4] |

3 (1.8) [4.2] |

| Cerebrocardiovascular eventsc |

2 (1.2) [0.6] |

0 | 0 |

2 (1.2) [2.3] |

7 (4.1) [2.3] |

0 |

7 (4.1) [7.5] |

0 |

| Malignancies |

7 (4.2) [2.0] |

3 (1.8) [2.1] |

3 (1.8) [2.7] |

2 (1.2) [2.3] |

2 (1.2) [0.7] |

0 |

2 (1.2) [2.2] |

0 |

| Depression |

6 (3.6) [1.7] |

4 (2.4) [2.8] |

2 (1.2) [1.8] |

0 |

4 (2.4) [1.3] |

2 (1.2) [1.5] |

2 (1.2) [2.2] |

0 |

| Inflammatory bowel diseased | ||||||||

| Reported by investigator |

1 (0.6) [0.3] |

0 |

1 (0.6) [0.9] |

0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Confirmed by adjudicatione | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cytopenias |

3 (1.8) [0.9] |

2 (1.2) [1.4] |

0 |

1 (0.6) [1.1] |

1 (0.6) [0.3] |

1 (0.6) [0.7] |

0 | 0 |

| Hepatic events |

14 (8.3) [4.1] |

8 (4.8) [5.6] |

6 (3.6) [5.3] |

2 (1.2) [2.3] |

12 (7.1) [4.0] |

8 (4.7) [6.0] |

2 (1.2) [2.2] |

2 (1.2) [2.8] |

Values in table are presented as a number, with the percentage in parentheses and the IR per 100 PY in square brackets

IR incidence rate, PY patient-years, TEAE treatment-emergent adverse event

aPatients may have multiple events per category

bDeaths are also included as serious adverse events and study treatment discontinuations due to adverse events

cCerebro-cardiovascular events have been adjudicated

dInflammatory bowel disease includes the following narrow terms: inflammatory bowel disease, Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis, and ulcerative proctitis

eCases were reviewed by an independent committee of experts for adjudication and classified as ‘probable’ or ‘definite’ by Registre Epidemiologique des Maladies de l’Appareil Digestif (EPIMAD) criteria

The frequency of AEs leading to discontinuation was slightly lower with IXE Q4W than with IXE Q2W overall (n = 17 vs. n = 21). The IR of discontinuations was also reasonably stable over time in the IXE Q4W group (IR range 4.9–6.2) but more variable in the IXE Q2W group (IR range 0–10.5), with no events in the 2- to 3-year timeframe for IXE Q2W (Table 2). Except for psoriatic arthropathy reported by two patients in the IXE Q4W group, all other AEs resulting in discontinuation were reported in one patient each (ESM Table S4). SAEs were reported by 19 (5.5 IR) IXE Q4W-treated patients and 23 (7.7 IR) IXE Q2W-treated patients (ESM Table S5). Three deaths were recorded in the extension period. One female patient aged 64 years (IXE Q4W group) died from metastatic renal cell carcinoma on day 503 of treatment. One male patient aged 65 years (PBO/IXE Q2W group) with a history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and hypertension died as a result of cardiopulmonary arrest on day 334 of treatment. One female patient aged 75 years (IXE Q2W group) died from myocardial infarction on day 765 of treatment. This patient had a history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, coronary artery disease, hyperlipidemia, hypercholesterolemia, transient ischemic attack, and previous myocardial infarction. None of the deaths were considered by the investigator to be related to the study drug.

The IR of infections, reported as n (IR per 100 PY), was 112 (32.5) and 101 (33.8) for IXE Q4W- and IXE Q2W-treated patients, respectively. Infections were more common during the first year of treatment, after which the IR decreased over time. Ten serious infections were reported, five in each IXE treatment group. These included pneumonia (one patient in each ixekizumab arm); diverticulitis, latent tuberculosis, lower respiratory tract infection, oral candidiasis (one patient each in the IXE Q4W arm); jaw abscess, anal abscess, perirectal abscess, and esophageal candidiasis (one patient each in the IXE Q2W arm). Fifteen patients had Candida infections (high-level term): one patient (0.3 IR) in the IXE Q4W arm and five patients (1.7 IR) in the IXE Q2W arm had oral candidiasis; two patients in each arm had vulvovaginal candidiasis (1.2 IR per 100 PY each); one patient in each arm had genital candidiasis (0.6 IR IXE Q4W and 0.3 IR IXE Q2W); one patient in the IXE Q2W arm had esophageal candidiasis (0.3 IR); and two patients in the IXE Q4W arm had skin candida (0.6 IR). Nine patients had fungal infections (high-level term): five patients (1.4 IR) in the IXE Q4W arm and four (1.3 IR) in the IXE Q2W arm. No case of Candida or fungal infection resulted in discontinuation; all were mild to moderate and without deep organ involvement. Five (1.7 IR) cases of herpes zoster in the IXE Q2W treatment group were observed, none of which resulted in treatment discontinuation. No cases of active tuberculosis were reported.

The IR of hypersensitivity events, reported as n (IR per 100 PY), in the IXE Q4W and IXE Q2W treatment groups was 17 (4.9) and 16 (5.4), respectively, and generally decreased from year 1 to year 3. There were no reports of anaphylaxis. A total of 67 injection-site reaction (ISR) events were observed: 25 (7.2 IR) in the IXE Q4W treatment group and 42 (14.1 IR) in the IXE Q2W treatment group. The IR of ISRs decreased after the first year of treatment.

There were nine patients with malignancies: seven (2.0 IR) in the IXE Q4W treatment group and two (0.7 IR) in the IXE Q2W treatment group. The IRs of malignancies were constant over time. Four patients in the IXE Q4W group and one patient in the IXE Q2W group had nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC). Malignancies excluding NMSC occurred in four patients in the IXE Q4W group and one patient in the IXE Q2W group.

Previously, a patient was reported in the double-blind treatment period as having SAEs of anal abscess and anal fistula considered by the sponsor to be consistent with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Upon post hoc adjudication by an external committee of IBD specialists, the event was determined to not be a confirmed event of IBD [15]. A second patient, a 47-year-old woman (with a medical history consistent with the presence of ulcerative colitis) who was randomized to PBO at baseline and received IXE Q4W in the extension period, reported an event of ulcerative colitis. The external adjudication committee determined that this event was not a confirmed event of IBD.

Nine patients (2 [0.6 IR] in the IXE Q4W group and 7 [2.3 IR] in the IXE Q2W group) had a cerebro-cardiovascular event confirmed by external adjudication. All cerebrocardiovascular events in the IXE Q4W group occurred in years 2–3, and all events in the IXE Q2W group occurred during years 1–2 of the extension period. Depression was reported in ten patients (6 in the IXE Q4W arm and 4 in the IXE Q2W arm), with a similar IR across both treatment groups (Table 2).

Discussion

The data reported in this study covers up to 3 years of continuous treatment with ixekizumab in a difficult-to-treat population of patients with PsA who had an inadequate response or were intolerant to one or two TNF inhibitors. Treatment with ixekizumab resulted in improvements in the signs and symptoms of PsA that persisted from week 24 through week 156. ACR20 responses (primary study endpoint) at week 24 (IXE Q4W, 71% and IXE Q2W, 67%; observed), were maintained to week 156 (IXE Q4W, 84% and IXE Q2W, 85%; observed). Ixekizumab treatment was also associated with resolution of enthesitis and improvement of patient-reported physical and mental outcomes and plaque and nail psoriasis over the study duration. High rates of dactylitis resolution were also achieved in both groups, but the small number of patients with dactylitis at baseline limits the scope of conclusions that can be drawn from these data.

The treat-to-target goals of MDA, DAPSA LDA, and DAPSA remission were achieved by approximately 50, 38, and 35% of patients, respectively, treated with ixekizumab through week 156. Patients taking PBO who were re-randomized to ixekizumab treatment at week 16 or 24 demonstrated comparable efficacy at week 156 in joint and skin endpoints to patients on continuous ixekizumab treatment. Although this clinical trial was not powered to detect statistical differences between the IXE Q2W and IXE Q4W treatment arms, there was no apparent increased benefit with IXE Q2W relative to IXE Q4W (the approved dose for the treatment of active PsA in patients who do not have coexisting moderate-to-severe psoriasis [12, 13]) in arthritis-related measures. These 3-year data, both observed as well as mNRI, support the long-term continued efficacy of ixekizumab for the treatment of active PsA.

The safety profile of ixekizumab was generally consistent with that previously observed in patients with active PsA or moderate-to-severe psoriasis who received ixekizumab and with the double-blind treatment period of this study [15, 16, 21–23]. Most TEAEs were mild or moderate in severity and the IR tended to decrease over time. Overall, the exposure-adjusted IR of discontinuations due to AEs was low and similar between ixekizumab treatment arms.

Treatments that modulate immune response may increase susceptibility to infection, but this typically reduces after the first 6 months to 1 year of treatment [24–27]. Throughout the 156-week treatment period, there were no unexpected infections, and the IR tended to decrease over time. Cases of candidiasis were more frequent with IXE Q2W than IXE Q4W, and no event led to discontinuation. The overall IR for serious infections was low (IR range 1.4–1.8) and was comparable to overall rates observed with ixekizumab treatment across several indications [27]. Furthermore, the IRs for serious infections were comparable to those observed with the IL-17A inhibitor secukinumab (IR 1.9 in PsA) [28] and the TNF inhibitors adalimumab (IR 2.8 in PsA) [29] and golimumab (IR 1.0 across indications) [30].

ISRs have been noted with all US Food and Drug Administration-approved self-injectable biological agents [31]. None of the ISRs with ixekizumab were considered to be serious and all were mild or moderate in severity in this study. ISRs were numerically higher in the IXE Q2W (14.1 IR) arm than in the IXE Q4W (7.2 IR) arm, with one discontinuation due to ISRs in each arm. In agreement with other studies of ISRs with ixekizumab, reactions were typically tolerable, manageable, and decreased over time [32].

People with PsA have a two- to three-fold increased risk of IBD [33, 34], and IBD is an AESI for the IL-17 inhibitor class of biologics [35, 36]. In this study, IBD events were infrequent (IXE Q4W, 0.3 IR; IXE Q2W, 0 IR). This is in line with the expected IR of IBD (Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis) in patients with PsA (0.03–0.11 IR) [33, 37, 38] and is consistent with an integrated analysis demonstrating that among 8228 ixekizumab-treated patients with psoriasis, PsA, or axial spondyloarthritis, IBD was reported in < 1% of the population [27].

The SPIRIT clinical trial program was unique in assessing the efficacy of ixekizumab in two distinct patient populations. Three-year data from SPIRIT-P1, a phase 3 trial investigating ixekizumab treatment in patients with active PsA who had not previously received biologic therapy for PsA or psoriasis, have recently been published [14]. Patients with inadequate response to one TNF inhibitor typically have decreased response to a second TNF inhibitor [9, 39]. This population of patients with PsA, over half of whom were inadequate responders to one TNF inhibitor and over a third were inadequate responders to two TNF inhibitors, presents specific challenges to clinicians but has not been studied extensively in dedicated clinical trials. Efficacy data from SPIRIT-P2 assessing multiple characteristics of PsA, including enthesitis, dactylitis, skin and nail psoriasis, and patient-reported outcomes support ixekizumab as a viable treatment option in this population of patients with refractory disease. The efficacy and safety findings of SPIRIT-P2 are similar with the observations from SPIRIT-P1; however, as is expected in the more difficult patient population of SPIRIT P2, levels of response are slightly lower than in SPIRIT P1 [14]. Long-term efficacy and safety data from SPIRIT-P1 and -P2 indicate that ixekizumab is an effective treatment option for patients with active PsA across the multiple disease domains, even among patients who have had an inadequate response to one or two TNF inhibitors.

One of the inherent limitations to the study design of this trial was the implementation of MDC at week 32. These criteria limit the generalizability of these data as they do not allow for fluctuation in PsA disease activity that is often managed in the clinic with concomitant csDMARDs or steroids before discontinuing or switching a biologic DMARD. It should also be acknowledged that the resulting patient population may partially contribute to the favorable outcomes observed in this study. This trial also did not include an assessment of radiographic progression, the inhibition of which has been shown previously with ixekizumab [21, 23], and the prevention of which is important for joint integrity. However, in a PsA population with a high proportion of TNF inadequate responders, baseline X-ray data may be difficult to interpret.

Conclusion

In conclusion, ixekizumab provided sustained and clinically meaningful improvement in the signs and symptoms of active PsA for up to 156 weeks among patients with an inadequate response or intolerance to one or two TNF inhibitors. The safety findings were consistent with the known safety profile of ixekizumab. Overall, these results support the long-term use of ixekizumab among patients with PsA, including those who may be more difficult to treat due to prior inadequate response to TNF inhibitors.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the patients for their involvement in the study.

Funding

The studies described in this manuscript were sponsored by Eli Lilly and Company, which was involved in the study design, data collection, data analysis, and preparation of the manuscript. Eli Lilly and Company also funded the journal’s Rapid Service Fees.

Medical Writing and Other Assistance

Medical writing assistance was provided by Samantha Forster, PhD, CMPP, of ProScribe – Envision Pharma Group, and was funded by Eli Lilly and Company. ProScribe’s services complied with international guidelines for Good Publication Practice (GPP3).

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Authorship Contributions

All authors participated in the interpretation of study results and in the drafting, critical revision, and approval of the final version of the manuscript.

Disclosures

Ana-Maria Orbai is a Jerome L. Greene Foundation Scholar and is supported in part by a research grant from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under award number P30-AR070254; is a consultant for Eli Lilly and Company, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB Pharma; has received research funding from Celgene, Janssen, and Novartis; and has been an investigator for AbbVie, Celgene, Eli Lilly and Company, Gilead Sciences, and Novartis. Jordi Gratacós has received research grants or consulting fees from AbbVie, Celgene, Eli Lilly and Company, Janssen, Novartis, and Pfizer. Anthony Turkiewicz has received research grants or consulting fees from AbbVie, Eli Lilly and Company, Janssen, Novartis, and Pfizer and is on the speakers bureau for AbbVie, Eli Lilly and Company, Janssen, Novartis, and Pfizer. Stephen Hall has received research funding from AbbVie, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Eli Lilly and Company, Janssen, Pfizer, and UCB Pharma. Eva Dokoupilova received grant/research support from AbbVie, Affibody AB, Eli Lilly and Company, Galapagos, Gilead Sciences, GSK, Hexal AG, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, R-Pharm, Sanofi-Aventis, and UCB Biopharma SPRL. Bernard Combe has received grant/research support from Novartis, Pfizer, and Roche-Chugai; is a consultant for AbbVie, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly and Company, Janssen, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Roche-Chugai, and UCB Pharma; and is on the speakers bureau of Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly and Company, Gilead Sciences, Merck Sharp & Dohme, and Pfizer. Peter Nash is a consultant for AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Eli Lilly and Company, Hospira, Janssen, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi, and UCB Pharma; is on the speakers bureau of AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Eli Lilly and Company, Hospira, Janssen, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi, and UCB Pharma; and has received research funding from AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Eli Lilly and Company, Hospira, Janssen, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi, and UCB Pharma. Gaia Gallo, Clinton C. Bertram, Amanda M. Gellett, Aubrey Trevelin Sprabery, Julie Birt, Lisa Macpherson, and Vladimir J. Geneus are employees and shareholders of Eli Lilly and Company. Arnaud Constantin has received consulting fees from AbbVie, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Janssen, Eli Lilly and Company, Gilead Sciences, Medac, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Nordic Pharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi, and UCB Pharma.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The trial described was conducted in accordance with the Good Clinical Practice guidelines of the International Conference on Harmonisation and with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol and documentation was approved by the institutional review board or independent ethics committee at each investigational site prior to patient screening (see ESM). All patients provided written informed consent prior to receiving investigational product or undergoing study procedures. SPIRIT-P2 is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02349295).

Data Availability

Eli Lilly and Company provides access to all individual participant data collected during the trial, after anonymization, with the exception of pharmacokinetic or genetic data. Data are available to request 6 months after the indication studied has been approved in the US and EU and after primary publication acceptance, whichever is later. No expiration date of data requests is currently set once data are made available. Access is provided after a proposal has been approved by an independent review committee identified for this purpose and after receipt of a signed data sharing agreement. Data and documents, including the study protocol, statistical analysis plan, clinical study report, and blank or annotated case report forms, will be provided in a secure data sharing environment. For details on submitting a request, see the instructions provided at http://www.vivli.org.

References

- 1.Alinaghi F, Calov M, Kristensen LE, et al. Prevalence of psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational and clinical studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:251–265.e19. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ritchlin CT, Colbert RA, Gladman DD. Psoriatic arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:957–970. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1505557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gladman DD, Antoni C, Mease P, Clegg DO, Nash P. Psoriatic arthritis: epidemiology, clinical features, course, and outcome. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64:ii14–ii17. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.032482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Veale DJ, Fearon U. The pathogenesis of psoriatic arthritis. Lancet. 2018;391:2273–2284. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30830-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coates LC, Kavanaugh A, Mease PJ, et al. Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis 2015 treatment recommendations for psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:1060–1071. doi: 10.1002/art.39573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gossec L, Smolen JS, Ramiro S, et al. European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) recommendations for the management of psoriatic arthritis with pharmacological therapies: 2015 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:499–510. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Menegatti S, Bianchi E, Rogge L. Anti-TNF therapy in spondyloarthritis and related diseases, impact on the immune system and prediction of treatment responses. Front Immunol. 2019;10:382. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mease P. A short history of biological therapy for psoriatic arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2015;33:S104–S108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Merola JF, Lockshin B, Mody EA. Switching biologics in the treatment of psoriatic arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2017;47:29–37. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2017.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh JA, Guyatt G, Ogdie A, et al. Special article: 2018 American College of Rheumatology/National Psoriasis Foundation guideline for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71:5–32. doi: 10.1002/art.40726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kirkham BW, Kavanaugh A, Reich K. Interleukin-17A: a unique pathway in immune-mediated diseases: psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. Immunology. 2014;141:133–142. doi: 10.1111/imm.12142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eli Lilly and Company. Taltz (ixekizumab) injection, for subcutaneous use [prescribing information]. https://pi.lilly.com/us/taltz-uspi.pdf. Accessed 29 Oct 2019.

- 13.European Medicines Agency. Taltz 80 mg solution for injection in pre-filled syringe [summary of product characteristics]. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/7233/smpc. Accessed 29 Oct 2019.

- 14.Chandran V, van der Heijde D, Fleischmann RM, et al. Ixekizumab treatment of biologic-naïve patients with active psoriatic arthritis: 3-year results from a phase III clinical trial (SPIRIT-P1) Rheumatology (Oxford) 2020;59:2774–2784. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kez684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nash P, Kirkham B, Okada M, et al. Ixekizumab for the treatment of patients with active psoriatic arthritis and an inadequate response to tumour necrosis factor inhibitors: results from the 24-week randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled period of the SPIRIT-P2 phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389:2317–2327. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31429-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Genovese MC, Combe B, Kremer JM, et al. Safety and efficacy of ixekizumab in patients with PsA and previous inadequate response to TNF inhibitors: week 52 results from SPIRIT-P2. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2018;57:2001–2011. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/key182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taylor W, Gladman D, Helliwell P, et al. Classification criteria for psoriatic arthritis: development of new criteria from a large international study. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2665–2673. doi: 10.1002/art.21972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Genovese MC, Combe B, Kremer JM, et al. Safety and efficacy of ixekizumab in patients with PsA and previous inadequate response to TNF inhibitors: week 52 results from SPIRIT-P2. Rheumatology (Oxford. 2018;57:2001–2011. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/key182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coates LC, Fransen J, Helliwell PS. Defining minimal disease activity in psoriatic arthritis: a proposed objective target for treatment. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:48–53. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.102053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mease P, Roussou E, Burmester GR, et al. Safety of ixekizumab in patients with psoriatic arthritis: results from a pooled analysis of three clinical trials. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2019;71:367–378. doi: 10.1002/acr.23738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mease PJ, van der Heijde D, Ritchlin CT, et al. Ixekizumab, an interleukin-17A specific monoclonal antibody, for the treatment of biologic-naive patients with active psoriatic arthritis: results from the 24-week randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled and active (adalimumab)-controlled period of the phase III trial SPIRIT-P1. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:79–87. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strober B, Leonardi C, Papp KA, et al. Short- and long-term safety outcomes with ixekizumab from 7 clinical trials in psoriasis: etanercept comparisons and integrated data. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76(432–40):e17. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van der Heijde D, Gladman DD, Kishimoto M, et al. Efficacy and safety of ixekizumab in patients with active psoriatic arthritis: 52-week results from a phase III study (SPIRIT-P1) J Rheumatol. 2018;45:367–377. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.170429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kalb RE, Fiorentino DF, Lebwohl MG, et al. Risk of serious infection with biologic and systemic treatment of psoriasis: results from the Psoriasis Longitudinal Assessment and Registry (PSOLAR) JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:961–969. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.0718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Listing J, Gerhold K, Zink A. The risk of infections associated with rheumatoid arthritis, with its comorbidity and treatment. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2013;52:53–61. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kes305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Combe B, Rahman P, Kameda H, et al. Safety results of ixekizumab with 1822.2 patient-years of exposure: an integrated analysis of 3 clinical trials in adult patients with psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2020;22:14. doi: 10.1186/s13075-020-2099-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Genovese MC, Mysler E, Tomita T, et al. Safety of ixekizumab in adult patients with plaque psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis and axial spondyloarthritis: data from 21 clinical trials. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2020. 10.1093/rheumatology/keaa189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Deodhar A, Mease PJ, McInnes IB, et al. Long-term safety of secukinumab in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis: integrated pooled clinical trial and post-marketing surveillance data. Arthritis Res Ther. 2019;21:111. doi: 10.1186/s13075-019-1882-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burmester GR, Panaccione R, Gordon KB, McIlraith MJ, Lacerda AP. Adalimumab: long-term safety in 23 458 patients from global clinical trials in rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, psoriasis and Crohn's disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:517–524. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-201244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thomas K, Flouri I, Repa A, et al. High 3-year golimumab survival in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis and psoriatic arthritis: real world data from 328 patients. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2018;36:254–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thomaidou E, Ramot Y. Injection site reactions with the use of biological agents. Dermatol Ther. 2019;32:e12817. doi: 10.1111/dth.12817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shear NH, Paul C, Blauvelt A, et al. Safety and tolerability of ixekizumab: integrated analysis of injection-site reactions from 11 clinical trials. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17:200–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Egeberg A, Mallbris L, Warren RB, et al. Association between psoriasis and inflammatory bowel disease: a Danish nationwide cohort study. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:487–492. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Makredes M, Robinson D, Bala M, Kimball AB. The burden of autoimmune disease: a comparison of prevalence ratios in patients with psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:405–410. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hueber W, Sands BE, Lewitzky S, et al. Secukinumab, a human anti-IL-17A monoclonal antibody, for moderate to severe Crohn's disease: unexpected results of a randomised, double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Gut. 2012;61:1693–1700. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Targan SR, Feagan B, Vermeire S, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 study of brodalumab in patients with moderate-to-severe Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:1599–1607. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2016.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Charlton R, Green A, Shaddick G, et al. Risk of uveitis and inflammatory bowel disease in people with psoriatic arthritis: a population-based cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77:277–280. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-212328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li W-Q, Han J-L, Chan AT, Qureshi AA. Psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis and increased risk of incident Crohn's disease in US women. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:1200–1205. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mease PJ, Karki C, Liu M, et al. Discontinuation and switching patterns of tumour necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFis) in TNFi-naive and TNFi-experienced patients with psoriatic arthritis: an observational study from the US-based Corrona registry. RMD Open. 2019;5:e000880. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2018-000880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schoels MM, Aletaha D, Alasti F, Smolen JS. Disease activity in psoriatic arthritis (PsA): defining remission and treatment success using the DAPSA score. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:811–818. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-207507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Anderson J, Caplan L, Yazdany J, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis disease activity measures: American College of Rheumatology recommendations for use in clinical practice. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012;64:640–647. doi: 10.1002/acr.21649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Coates LC, Gottlieb AB, Merola JF, Boone C, Szumski A, Chhabra A. Comparison of different remission and low disease definitions in psoriatic arthritis and evaluation of their prognostic value. J Rheumatol. 2019;46:160–165. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.180249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Eli Lilly and Company provides access to all individual participant data collected during the trial, after anonymization, with the exception of pharmacokinetic or genetic data. Data are available to request 6 months after the indication studied has been approved in the US and EU and after primary publication acceptance, whichever is later. No expiration date of data requests is currently set once data are made available. Access is provided after a proposal has been approved by an independent review committee identified for this purpose and after receipt of a signed data sharing agreement. Data and documents, including the study protocol, statistical analysis plan, clinical study report, and blank or annotated case report forms, will be provided in a secure data sharing environment. For details on submitting a request, see the instructions provided at http://www.vivli.org.