Abstract

All metazoans depend on the consumption of O2 by the mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation system (OXPHOS) to produce energy. In addition, the OXPHOS uses O2 to produce reactive oxygen species that can drive cell adaptations1–4, a phenomenon that occurs in hypoxia4–8 and whose precise mechanism remains unknown. Ca2+ is the best known ion that acts as a second messenger9, yet the role ascribed to Na+ is to serve as a mere mediator of membrane potential10. Here we show that Na+ acts as a second messenger that regulates OXPHOS function and the production of reactive oxygen species by modulating the fluidity of the inner mitochondrial membrane. A conformational shift in mitochondrial complex I during acute hypoxia11 drives acidification of the matrix and the release of free Ca2+ from calcium phosphate (CaP) precipitates. The concomitant activation of the mitochondrial Na+/Ca2+ exchanger promotes the import of Na+ into the matrix. Na+ interacts with phospholipids, reducing inner mitochondrial membrane fluidity and the mobility of free ubiquinone between complex II and complex III, but not inside supercomplexes. As a consequence, superoxide is produced at complex III. The inhibition of Na+ import through the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger is sufficient to block this pathway, preventing adaptation to hypoxia. These results reveal that Na+ controls OXPHOS function and redox signalling through an unexpected interaction with phospholipids, with profound consequences for cellular metabolism.

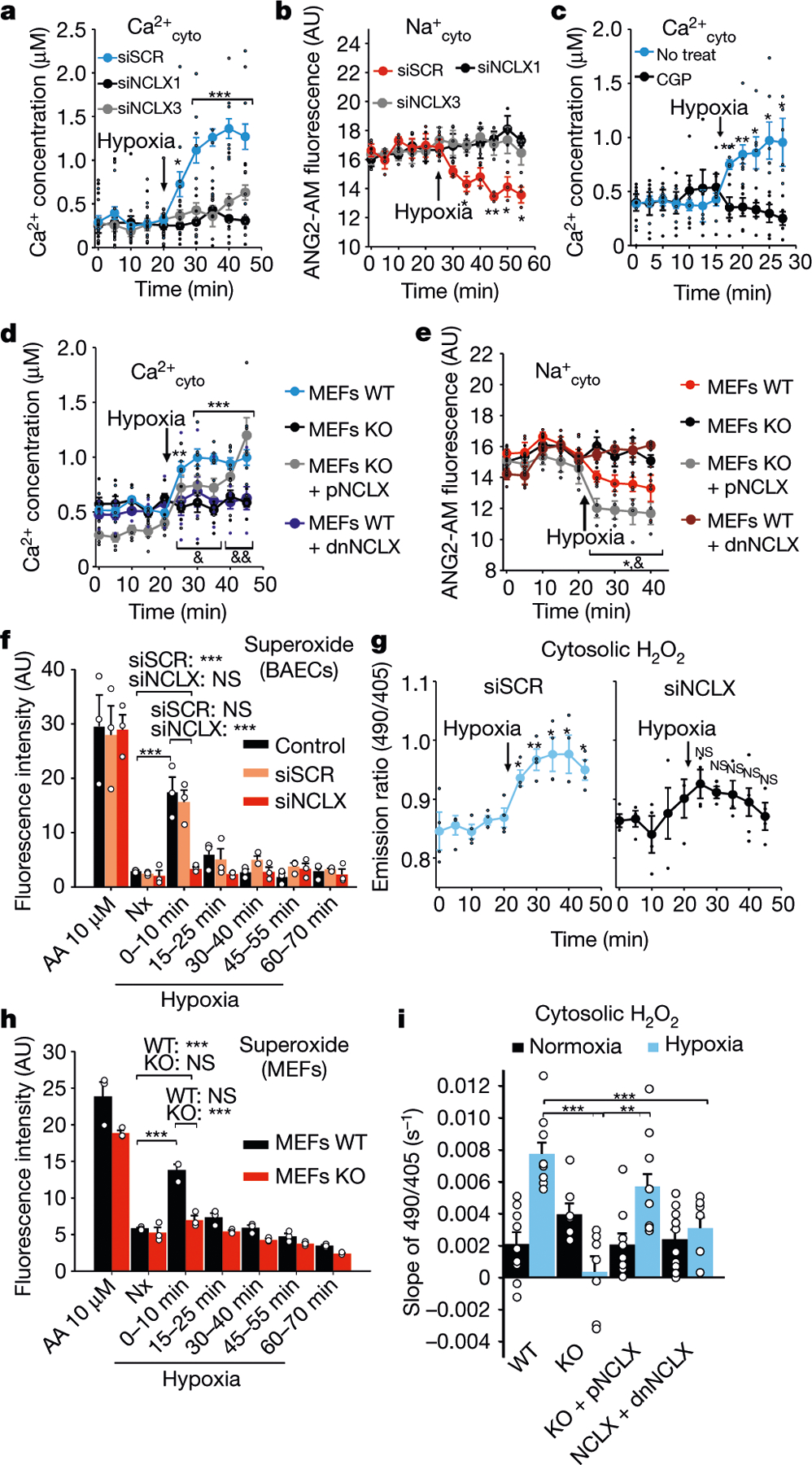

Cells and tissues produce a superoxide burst as an essential feature of several adaptive responses, including hypoxia7,11. Given the importance of the mitochondrial Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCLX) in ischaemia–reperfusion injury12, we studied whether this exchanger may have a role in hypoxic redox signalling. Primary bovine aortic endothelial cells (BAECs) and mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) exposed to acute hypoxia showed an increase in cytosolic Ca2+ concentration (Ca2+cyto) and a decrease in cytosolic Na+ concentration (Na+cyto) that were prevented by NCLX knockdown with small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), NCLX genetic deletion, overexpression of a dominant negative form of NCLX (dnNCLX) or its pharmacological inhibition with CGP-37157 (Fig. 1a–e, Extended Data Figs. 1a–j, 2), an effect rescued by expression of human NCLX (pNCLX) in NCLX knockout (KO) MEFs (Fig. 1d, e, Extended Data Fig. 1e–g). Notably, NCLX inhibition did not interfere with mitochondrial membrane potential or respiration (Extended Data Fig. 1k, l). Thus, acute hypoxia induces NCLX activation. The hypoxic reactive oxygen species (ROS) burst was blocked by NCLX knockdown by siRNA (hereafter referred to as siNCLX) and shRNA, NCLX genetic deletion, overexpression of dnNCLX or inhibition with CGP-37157 (Fig. 1f–i, Extended Data Fig. 3), and rescued by expression of human NCLX in KO MEFs (Fig. 1i). Therefore, NCLX activity is necessary for mitochondrial ROS production during hypoxia.

Fig. 1 |. Hypoxia activates Na+/Ca2+ exchange and enhances ROS production through NCLX.

a–e, Ca2+cyto (Cyto-GEM-GECO) or Na+cyto (Asante NaTRIUM-2 AM (ANG2-AM)) measured by live-cell confocal microscopy in normoxia and after induction of hypoxia (1% O2) in the following: BAECs transfected with scrambled siRNA (siSCR), siNCLX1 or siNCLX3 (a, b); untreated BAECs (No treat) or treated with CGP-37157 (CGP; c); and wild-type (WT), NCLX KO (KO), NCLX KO + pNCLX or NCLX WT + dnNCLX MEFs (d, e). f–i, ROS production measured by live-cell confocal microscopy (g, i) or fixed-cell fluorescence microscopy (f, h) in normoxia (Nx) or hypoxia (Hp; 1% O2). Superoxide detection after incubation with dihydroethidium (DHE) in 10-min time windows in non-treated (Control), siSCR-treated or siNCLX-treated BAECs (f). AA, antimycin A. Detection of H2O2 with CytoHyPer in siSCR-treated or siNCLX-treated BAECs (g). Same as f in WT or NCLX KO immortalized MEFs (h). Same as g in WT, NCLX KO, KO + pNCLX or WT + dnNCLX immortalized MEFs (i). In a–e, time-course traces of three (a, b), six (c) or four (d, e) independent experiments, in f, h, the mean intensity of three independent experiments, in g, time-course traces of four independent experiments, and in i, the slopes of nine independent experiments (except for NCLX KO, n = 7; WT + dnNCLX, n = 10) are shown. All data are represented as mean ± s.e.m. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons (f, h, i) and two-tailed Student’s t-test (last normoxia time versus hypoxia times; a–e, g): *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Two-tailed Student’s t-test (last normoxia time versus hypoxia times in KO + pNCLX; d, e): &P < 0.05, &&P < 0.01. In f, h, statistical comparisons are shown only for normoxia versus 0–10 groups. AU, arbitrary units; NS, not significant.

Hypoxia dissolves CaP granules

To date, mitochondrial complex III (CIII) and CI have been reported to be necessary for ROS production and cellular adaptation to hypoxia5,6,13. To examine their contribution, we knocked down either the CI subunit NDUFS4 or the CIII subunit RISP, or pharmacologically inhibited CI, CIII or CIV, but only CI inhibition abrogated Na+/Ca2+ exchange in hypoxia (Extended Data Fig. 4). Thus, CI is necessary for NCLX activation during acute hypoxia.

Next, we evaluated how CI influenced NCLX activity during hypoxia. CI presents two functionally different conformation states, active and deactive (D-CI)14–16, and we previously reported that the D-CI conformation is favoured in acute hypoxia11. As the D-CI conformation exposes Cys39 of the ND3 subunit14, allowing fluorescent labelling of this residue11, we confirmed that 5 min of hypoxia increased the D-CI conformation; in parallel, the CI reactivation rate diminished, regardless of NCLX inhibition (Extended Data Fig. 5a–d). We also confirmed that hypoxia promotes mitochondrial matrix acidification, an effect anticipated by CI inhibition or genetic ablation (Extended Data Fig. 5e, f), but that was independent of NCLX activity (Extended Data Fig. 5g, h). Moreover, the fact that Na+/Ca2+ exchange was inhibited by rotenone (Extended Data Fig. 5i, j) further identifies D-CI formation as a necessary step in NCLX activation. Acute hypoxia increased the mitochondrial matrix Ca2+ concentration (Ca2+mito) and this was augmented by NCLX knockdown (Fig. 2a). Thus, the increase in Ca2+mito drives NCLX activation and Ca2+ efflux to the cytosol. Intriguingly, cells lacking the mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter (MCU) still displayed a normal increase in Ca2+cyto and a less sustained but conspicuous increase in Ca2+mito (Fig. 2b, c). This behaviour may be explained by the existence of a potential intra-organelle source of Ca2+mito. It has been known for decades that mitochondria harbour electron-dense spots composed of CaP precipitates, which are extremely sensitive to acidification17, but whose function remains obscure9. Transmission electron microscopy and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (TEM–EDX) analysis showed that the mitochondrial electron-dense spots were enriched in Ca2+ (Extended Data Fig. 6a). We found that CaP precipitates decreased in both size and frequency upon pharmacological induction of matrix acidification (Fig. 2d, Extended Data Fig. 6b). We also observed that acute hypoxia promoted a decrease in the size of the precipitates (Fig. 2d), which correlated with an increase in soluble Ca2+mito (Fig. 2a, b). This observation strongly indicates that the primary burst in Ca2+mito that activates the NCLX derives from the solubilization of the intramitochondrial CaP precipitates.

Fig. 2 |. Mitochondrial CaP precipitates are the source of mitochondrial Ca2+ raise and of NCLX activation.

a, Ca2+mito (Cepia 2mt) measured by live-cell confocal microscopy in BAECs transfected with siSCR or siNCLX during normoxia and hypoxia (1% O2; n = 4). b, Same as a in WT or MCU KO human breast cancer cells during normoxia and hypoxia (1% O2; n = 3). c, Ca2+cyto (Cyto-GEM-GECO) measured by live-cell confocal microscopy in MCU WT or KO human breast cancer cells subjected to normoxia and hypoxia (1% O2; n = 6). d, Representative transmission electron microscopy images and the mean area of mitochondrial CaP precipitates during normoxia (64 precipitates), 10-min hypoxia (1% O2; 70 precipitates) or 30-min treatment with 1 μM FCCP (40 precipitates) in three independent experiments. The yellow asterisks mark the mitochondrial CaP precipitates. The box plots show the median and the first and third quartiles. e, Ca2+ content of mitochondria extracted from MEFs, which had been subjected to 10 min of normoxia or hypoxia (1% O2), measured in a hypotonic buffer at pH 6.8 (total mitochondrial Ca2+) or pH 7.5 (soluble mitochondrial Ca2+; n = 8). f, Same as a in BAECs treated or not treated with 1 μM rotenone during normoxia and acute hypoxia (1% O2; untreated n = 6 and rotenone n = 5). g, Same as a in WT or CI KO cybrids during normoxia and acute hypoxia (1% O2; n = 8). All data are represented as mean ± s.e.m., except in d. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons (b, d) and two-tailed Student’s t-test (last normoxia time versus hypoxia times in a; normoxia versus hypoxia in e): *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Two-tailed Student’s t-test (siSCR versus siNCLX in a): &P < 0.05, &&P < 0.01, &&&P < 0.001.

To obtain an independent, additional and quantitative estimation of the amount of Ca2+ that can be mobilized from these deposits, we measured Ca2+ concentration in mitochondrial preparations at both pH 7.5 and pH 6.8. We observed that the Ca2+ concentration was higher when the measurement was performed at pH 6.8 than at pH 7.5, indicating that we were indeed able to measure the acid-sensitive Ca2+ stored in mitochondrial precipitates (Fig. 2e). In addition, mitochondria purified from cells that had been exposed to normoxia showed higher Ca2+ levels at pH 6.8 than those exposed to hypoxia, confirming that hypoxia enables the partial dissolution of the mitochondrial CaP precipitates. By contrast, Ca2+ measured at pH 7.5 in mitochondria from hypoxic cells was slightly higher than normoxic samples (Fig. 2e; pH 7.5), confirming our previous results (Fig. 2a, b). Pharmacological acidification of the mitochondrial matrix produced a decrease in the acid-sensitive CaP pool (Extended Data Fig. 6c). Concomitantly, CI inhibition, which also acidifies the matrix, elicited an increase in mitochondrial soluble Ca2+, independently of the presence of the MCU (Extended Data Fig. 6d, e). Thus, if the increase in mitochondrial free Ca2+ levels is due to a CI-dependent acidification, chronic CI inhibition would anticipate the dissolution of the mitochondrial CaP precipitates and preclude the increase in mitochondrial Ca2+ levels upon acute hypoxia. Indeed, rotenone pre-treatment or genetic CI ablation abolished the elevation of mitochondrial soluble Ca2+ levels during hypoxia (Fig. 2f, g). Altogether, these results indicated that the CI active/deactive transition during hypoxia promotes mitochondrial matrix acidification, which, in turn, partially dissolves the CaP precipitates, and the concomitant increase in mitochondrial soluble Ca2+ levels activates the NCLX.

However, at longer times of hypoxia, intramitochondrial CaP deposits recovered (Extended Data Fig. 6f). In addition, MCU KO cell lines displayed a reduced increase in Ca2+mito (Fig. 2b), indicating that extramitochondrial Ca2+ contributes to the amplitude of the Ca2+mito raise. To evaluate its origin, we removed extracellular Ca2+ and, although we found no effect on the hypoxic dissolution of the acid-sensitive Ca2+ pool (Extended Data Fig. 6g), it had a very noticeable effect on the hypoxic raise of cytosolic Ca2+ levels (compare Extended Data Fig. 6h with Fig. 1d, light blue traces). Hypoxia also elicited a vast increase in endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ levels, which diminished, but not disappeared, upon extracellular Ca2+ removal (Extended Data Fig. 6i). All of these data indicate that extracellular Ca2+ is a relevant source of cellular Ca2+ during hypoxia. This prompted us to investigate whether mitochondrial Ca2+ entry, enabled by MCU, contributes to the hypoxic redox signal. We found that MCU ablation lowered the superoxide production during the first 10 min of hypoxia (Extended Data Fig. 6j), confirming that the MCU is involved in the amplification of the hypoxic redox signal through the facilitation of Ca2+ entry into the mitochondria. Taken together, our results show that the primary Ca2+ source for the first NCLX-dependent ROS wave is the CaP precipitates, which dissolve during hypoxia in a CI-dependent manner. Such initial ROS induce extracellular Ca2+ entry, which, in turn, enters the mitochondria through the MCU, further promoting NCLX-dependent ROS in a positive-feedback loop.

Mitochondrial Na+ regulates IMM fluidity

Next, we tested how NCLX activation triggered mitochondrial ROS production in acute hypoxia. RISP knockdown (siRISP) abolished the superoxide burst in acute hypoxia18,19 (Fig. 3a) without affecting NCLX activation (Extended Data Fig. 4b–d). This effect was reproduced by myxothiazol, an inhibitor of the CIII Qo site (Fig. 3b). ROS production by isolated mitochondria transiently increased upon NCLX activation after sequential addition of Na+ and Ca2+ (refs20,21) (Extended Data Fig. 7a).

Fig. 3 |. NCLX governs superoxide production and OXPHOS function in hypoxia through Na+-dependent alteration of IMM fluidity.

a, b, Superoxide detection with DHE with siSCR and siRISP (a), and untreated (No treat) or 1 μM myxothiazol-treated (Myxo) BAECs (n = 3) (b). c, d, Effect of NCLX activation on succinate-based respiration in BAECs (c; n = 5) or WT and NCLX KO (KO) MEFs (d; n = 6). e, f, Succinate-cytochrome c (CytC) activity in mitochondrial membranes from BAECs with or without NaCl (e; n = 4) and from hypoxic or normoxic WT or NCLX KO MEFs (f; 1% O2; n = 3). g, ROS production on succinate-CytC activity in BAEC mitochondrial membranes with or without NaCl (n = 10; AA n = 9). The box plots show the median, the first and third quartiles, and 5th and 95th percentiles of the data. h, NADH-CytC activity in BAEC mitochondrial membranes with or without NaCl (n = 3). i, G3PD-CytC activity in BAEC mitochondrial membranes with or without NaCl (n = 3). j, k, Effect of hypoxia (1% O2) on Na+mito content in WT and NCLX KO MEFs, measured with CoroNa red by life-cell confocal miscroscopy ( j; n = 8, except KO + pNCLX and WT + dnNCLX n = 4), or with SBFI fluorescence after mitochondrial isolation (k; n = 5). l, m, FRAP of siSCR or siNCLX BAECs (l; n = 16) and WT, NLCX KO, KO + pNCLX or WT + dnNCLX MEFs (m; n = 14; except WT Hp and KO pNCLX Hp n = 15) expressing mitoRFP in normoxia or hypoxia (20 min; 1% O2). n, NAO FRAP quench signal of siSCR or siNCLX BAECs exposed to normoxia or hypoxia (15 min; 1% O2; n = 5). o, Anisotropy of PC liposomes with increasing concentrations of NaCl by diphenyl-1,3,5-hexatriene (DPH) fluorescence (mean ± s.d.; n = 2). p, IR absorption spectra of the carbonyl group of PC with or without NaCl (n = 2). All data are represented as mean ± s.e.m., except in g and o. Two-tailed Student’s t-test (a, e, h–j) and one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test (b–d, f, g, k–o): NS, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Two-tailed Student’s t-test ( j): &P < 0.05. In a, b, statistics are shown only for normoxia versus 0–10 groups.

The contribution of the different electron transport chain complexes to respiration was measured in isolated mitochondria upon addition of different substrates and inhibitors22, in the absence or presence of Na+ and Ca2+, with and without the NCLX, or in the absence or presence of CGP-37157. In contrast to CIV-dependent or CI-dependent respiration, only CII-dependent respirations were decreased upon NaCl and CaCl2 addition in a NCLX-dependent manner (Fig. 3c, d, Extended Data Fig. 7b–e). CII + CIII activity in isolated mitochondrial membranes was unaffected by the addition of Ca2+ (Extended Data Fig. 7f), but clearly decreased after Na+ addition (Fig. 3e, Extended Data Fig. 7g), which also increased ROS production (Fig. 3g). CII + CIII activity was decreased in mitochondrial membranes of wild-type (WT) MEFs that had been subjected to hypoxia, an effect abolished by loss of the NCLX (Fig. 3f). Dimethylmalonate (a CII inhibitor) did not affect NCLX activity, but decreased the superoxide burst during hypoxia (Extended Data Fig. 7h–j). Surprisingly, individual CII or CIII activities showed no variation after Na+ addition (Extended Data Fig. 7k, l), neither did CI + CIII activity (Fig. 3h). Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (G3PD) + CIII activity also decreased in the presence of Na+ (Fig. 3i). In summary, while the individual activity of the different electron transport chain complexes is not affected by Na+, the combined activities of different electron donors to coenzyme Q (CoQ) with CIII behave differently based on the source of the reducing equivalents FADH2 (CII and G3PDH) or NADH (CI).

Electron transfer between CII and CIII (and between G3PD and CIII) is limited by CoQ diffusion through the inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM), which depends on its fluidity23,24. We assessed whether IMM fluidity was affected by NCLX activation and Na+ import during hypoxia. Acute hypoxia markedly increased Na+mito content through the NCLX (Fig. 3j, k, Extended Data Fig. 7m–p). Employing fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) of a red fluorescent protein targeted to the IMM (mitoRFP), we found that acute hypoxia reduced membrane fluidity; this effect was abolished by NCLX inhibition by siRNA, genetic deletion, overexpression of dnNCLX or CGP-37157 (Fig. 3l, m, Extended Data Fig. 8a, Supplementary Videos 1–8) and restored after ectopic expression of human NCLX in KO cells (Fig. 3m). We confirmed these results by using the lipophilic quenchable fluorescent probe 10-N-nonyl acridine orange (NAO) that preferentially binds to cardiolipin25, an abundant phospholipid of the IMM26,27 (Fig. 3n, Extended Data Fig. 8b). Reduced CoQH2 diffusion at the IMM matrix side would slow electron transfer from CII to CIII, and from CIII to oxidized CoQ in the CIII Qi site during Q cycle turnover28. Accordingly, we observed that hypoxic NCLX activity promoted an increase in oxidized CoQ10 (Extended Data Fig. 8c). The fact that Na+ exerts its effect when it is concentrated in the mitochondrial matrix highlights the physiological relevance of the asymmetric distribution of phospholipids between the two leaflets of the IMM.

To further explore the mechanism by which Na+ affects IMM fluidity, we measured the anisotropy of fluorescent probes in phosphatidylcholine (PC) or PC–cardiolipin liposomes. We observed that Na+ addition reduced the phospholipid bilayer fluidity (Fig. 3o, Extended Data Fig. 8d, e), a result supported by electron spin resonance experiments29, which further suggested that Na+–PC interaction occurs at the phospholipid headgroups (Extended Data Fig. 8f–i). Infrared (IR) spectroscopy of NaCl-treated PC liposomes showed a distinct shift in the absorption peak of the carbonyl group (Fig. 3p, Extended Data Fig. 8j). Inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry showed that the stoichiometry of the interaction is 0.29 ± 0.04 (Na+:PC). These results demonstrate that Na+ specifically interacts with phospholipids such as PC at the level of its carbonyl group, at a ratio of 3:1 (PC: Na+), which is in full agreement with previous estimations30,31, and suggests that this is responsible for reduced membrane fluidity during hypoxia.

Altogether, our data demonstrate that acute hypoxia promotes CI active/deactive transition and mitochondrial matrix acidification11, which partially solubilizes mitochondrial CaP precipitates to increase matrix free Ca2+ levels. The NCLX then exports Ca2+ and imports Na+ into the matrix. Matrix Na+ directly binds to IMM phospholipids and reduces membrane fluidity. This diminishes CoQ diffusion in the IMM matrix side and effectively uncouples the Q cycle of free CIII, increasing the half-life of the semiquinone form in the CIII Qo site and promoting superoxide anion formation28.

To study the physiological relevance of this pathway, we investigated whether its manipulation altered hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction. Rat pulmonary arteries exposed to hypoxia perform a rapid contractile response (peak contraction), which reaches a plateau (steady-state contraction). The latter is dependent on mitochondrial ROS32–34. NCLX silencing inhibited the hypoxic superoxide burst in rat pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (Extended Data Fig. 9a, b). Concomitantly, NCLX inhibition markedly reduced the steady-state component of pulmonary arterial hypoxic contraction (Extended Data Fig. 9c, d), similarly to antioxidants35. These observations suggest a physiological role for the NCLX in matching lung ventilation with perfusion through hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction, which is crucial for cardiovascular homeostasis.

Discussion

So far, the role ascribed to Na+ has been restricted to the support of membrane potentials and ion exchange (Na+/K+, Na+/Ca2+, among others). Here we show that Na+ directly modulates mitochondrial OXPHOS and ROS signalling with profound implications in tissue homeostasis. We also identify mitochondrial CaP precipitates as a relevant source of mitochondrial soluble Ca2+ in physiological conditions (Extended Data Fig. 10).

Notably, we observed that Na+ only exerted its effect on CII + CIII or G3PDH + CIII activities, but not on CI + CIII activity. CoQ10 transfer from CI to CIII may not decrease in the presence of Na+ because CI + CIII supercomplex activity does not depend as much on membrane fluidity, as it may utilize the CoQ (CoQNADH) partially trapped in the supercomplex microenvironment24,36,37. Conversely, CoQ10 transfer from either CII or G3PD to CIII strongly relies on membrane fluidity and, consequently, both CII + CIII and G3PD + CIII (CoQFAD) activities are lower in the presence of Na+. Therefore, the partial segmentation of the CoQ pool into CoQNADH and CoQFAD allows specific CIII-dependent ROS generation upon interaction of Na+ with the IMM matrix side in response to acute hypoxia, meanwhile respiration can be maintained by means of super complex function.

A recent report described the beneficial role of the NCLX by decreasing ROS production in a murine model of cardiac ischaemia–reperfusion12. During cardiac ischaemia, succinate accumulates, which causes superoxide production at reperfusion by reverse electron transport through CI4. There are three ways by which NCLX activation could hinder ROS production by reverse electron transport during reperfusion: (1) Na+–phospholipid interaction would restrain CoQH2 diffusion towards CI through the reduction of IMM fluidity; (2) the CoQH2/CoQ ratio drops during hypoxia in a NCLX-dependent manner, which would decrease reverse electron transport during reoxygenation; and (3) Ca2+ extrusion by the NCLX would prevent further tricarboxylic acid cycle dehydrogenase activation, limiting the production of reducing equivalents to OXPHOS complexes. Thus, our model fully supports the role of the NCLX in attenuating potential ROS production and injury upon cardiac reperfusion12 while promoting an adaptive short-time elevation of CIII-dependent ROS production during acute hypoxia.

Methods

Animals, cell culture and transfection

All animal experiments were performed following the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animal and were approved by the institutional ethics committee of the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid or the Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Spain, in accordance with the European Union Directive of 22 September 2010 (2010/63/UE) and with the Spanish Royal Decree of 1 February 2013 (53/2013). All efforts were made to minimize the number of animals used and their suffering. Sample size was not determined before experimentation.

Cells were routinely maintained in cell culture incubators (95% air, 5% CO2 in gas phase, at 37 °C).BAECs were isolated as previously described38 and cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 15% heat-inactivated FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. C57BL/6J MEFs, Slc8b1 (NCLX)fl/fl and C57BL/6J mouse adult fibroblasts (MAFs) were isolated as described previously39. Human breast cancer cells (provided by R. Rizzuto and D. De Stefani, University of Padova), WT cybrids, CI KO cybrids, MEFs and MAFs were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were isolated as previously described40 and cultured in Medium 199 supplemented with 20% heat-inactivated FBS, 16 U/mL heparin, 100 mg/L endothelial cell growth factor (ECGF), 20 mM HEPES, 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. BAECs were used between passages three and nine and HUVECs between passages three and seven. For MEFs, MAFs and human breast cancer cells were correctly identified visually. CI WT and KO cybrids were correctly recognized as per CI assembly by Blue Native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (BN-PAGE). Endothelial morphology was assessed by visual inspection, and cross-contamination/invasion with fibroblasts or other cell types was tested negative by checking endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) expression.

Rat pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (PASMCs) were isolated as previously described33 and cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 1.1 g/L pyruvate, 1% non-essential amino acids, 100 μg/mL streptomycin and 100 U/mL penicillin. PASMCs were used between passages two and three.

The hepatoma cell line HepG2 was cultured at 37 °C in DMEM supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 20 mM HEPES, 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. Identification was performed visually.

Transfection of 30 nM siRNA or 0.25 μg Cyto-GEM-GECO, Cepia 2mt, human NCLX (pNCLX; Addgene), S468T NCLX (dnNCLX), C199S pHyPer-Myto (mitosypHer), pHyPer-cyto (cytohyper) or pDsRed2-Mito (mitoRFP) vector DNA per 0.8 cm2 well was carried out using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Acute ablation in Slc8b1fl/fl MEFs was obtained by infection with adenoviruses expressing cytomegalovirus (CMV)-Cre (ad-CRE; 300 plaque-forming units (p.f.u.) per cell; Vector Biolabs). In PASMCs, 10 nM siRNA was transfected using Lipofectamine RNA iMAX (Invitrogen); in parallel experiments, siRNA efficiency was measured by PCR with reverse transcription (RT–PCR) using commercially available primers (TaqMan Gene Expression Assay Rn01481405_ m1, Applied Biosystems). Experiments were carried out 48–72 h after transfection.

Immortalization of HUVECs and MEFs was performed by retrovirus infection. 293T cells were transfected with 12 μg pCL-Ampho and 12 μg pBABE-SV40-puro using Lipofectamine RNA iMAX (Invitrogen). Two days later, 1/2 dilution of 293T cell media and 8 μg/mL polybrene were added on MEF or HUVEC cultures for 4 h. Then, the infection was repeated, but adding 4 μg/mL polybrene overnight. The next day, the first infection was repeated and, after 4 h, MEFs or HUVECs were passaged with 1/1,000 of puromycin.

All cultures were routinely checked for mycoplasma contamination and tested negative.

siRNA preparation

Four double-stranded siRNA against bovine NCLX were designed and purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies and Dharmacon (sense sequences of siNCLX1:AGCGGCCACUCAACUGCCU;siNCLX2:GUUUGGA ACUGAAACACU and UUCCGUAAGUGUUUCAGU mixed; siNCLX3: AAAGGUGGAAGUAAUCAC and ACGUAUUGUGAUUACUUC mixed; siNCLX4: GAAUUUGGAGUGAUUCAC and UUUUCAAGUGAAUCACUC mixed). Double-stranded siRNAs against bovine NDUFS4 and RISP were designed and purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (NDUFS4 sense sequence GCUGCCGUUUCCGUUUCCAAGGUUUTT; RISP sense sequence CCAAGAAUGUCGUCUCUCAGUUUTT). siSCR was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology.

siRNA against rat NCLX (Slc8b1 gene) was purchased from OriGene (Slc8b1 Trilencer-27 rat siRNA).

Detection of superoxide by fluorescence microscopy in fixed cells

Cells were seeded on glass coverslips 1 day before experimentation. In some experiments, 1 μM rotenone or 10 μM 7-chloro-5-(2-chlorophenyl)-1,5-dihydro-4,1-benzothiazepin-2(3H)-one (CGP-37157) was added 30 min before experimentation and maintained during the experiment. For treatments in hypoxia, all of the solutions were pre-equilibrated in hypoxic conditions before use; plated cells were introduced into an Invivo2 400 workstation (Ruskinn) set at 1% O2 and 5% CO2 at 37 °C, and incubated for the indicated times (0, 15, 30, 45 and 60 min) in fresh medium, washed three times with Hank’s balanced salt solution with Ca2+/Mg2+ (HBSS + Ca/Mg) and incubated with 5 μM DHE in HBSS + Ca/Mg for 10 min in the dark. Excess probe was removed by three washes with HBSS + Ca/Mg, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) and incubated in the dark at 4 °C for 15 min. After fixation, the cells were again washed three times with HBSS + Ca/Mg and coverslips were placed on slides. For normoxic treatments, the medium was changed to fresh normoxic medium, and cells were treated as for hypoxic cells but in a standard cell incubator. Images (three images per each coverslip; the number of independent experiments is described in the figure legends) were taken with a Leica DMR fluorescence microscope with a ×63 objective, using the 546–12/560 excitation/emission filter pairs, and quantified using ImageJ software (NIH). The same threshold was set for all of the images and the mean value from histograms was averaged for the three images of each coverslip.

Detection of intracellular Ca2+, Na+, ROS and mitochondrial membrane potential by live-imaging fluorescence microscopy

Cells were seeded in six-well plates 1 day before experimentation. Plated cells were washed three times with HBSS + Ca/Mg ± glucose and incubated with 30 nM tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester (TMRM), 1 μM Fluo-4 AM, 10 μM CoroNa Green AM or 10 μM 6-carboxy-2’,7’-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (CDCFDA) for 20 min at 37 °C in the dark. CDCFDA, CoroNa Green AM and Fluo-4 AM were then washed out and new HBSS + Ca/Mg was added. In some experiments, 10 μM CGP-37157 or 10 μM dimethylmalonate (DMM) was also added and maintained during the remainder of the experiment. For Fluo-4 AM imaging, cells were further incubated for 30 min at 37 °C in the dark to allow complete de-esterification of the probe. After this time, the plate was placed into a Leica DM 16000B fluorescence microscope equipped with a Leica DFC360FX camera, an automated stage for live imaging and a thermostated hypoxic cabinet. The planes were focused for image capture, and images were taken with a ×20 objective every 2 min during 40 min, providing a total of 21 cycles. Normoxia experiments started and ended at 20% O2 and 5% CO2, whereas hypoxia experiments started at 20% O2 and 5% CO2 and then were switched to 2% O2 and 5% CO2 in cycle two. The excitation/emission filter pairs used were as follows: 510–560/570–620 nm for TMRM, and 480–40/505 for CDCFDA, Fluo-4 AM and CoroNa Green AM. Images were quantified with Leica Las-AF software. Three independent experiments were performed for each condition. For each experiment and condition, four regions of interest (ROIs) were created, each ROI surrounding an individual cell, and the mean fluorescence of each ROI for each time cycle was collected. In some analyses, for each experiment and condition, four identical linear ROIs were created and the maximum peak value of cycles 0, 5, 10, 15 and 20 were collected for each ROI.

Detection of cytosolic Ca2+, Na+ and H2O2, endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ and intramitochondrial pH, Ca2+ and Na+ by live-imaging confocal microscopy

To detect intracellular Ca2+ and Na+, cells were seeded 1 day before experimentation, washed three times with HBSS + Ca/Mg + glucose and, in some experiments, incubated with 1 μM Fluo-4 AM, CoroNa Red or 5 μM CoroNa Green AM, ANG2 AM for 30 min at 37 °C in the dark. In some experiments, 10 μM CGP-37157, 10 μM DMM, 1 μM antimycin A, 1 mM KCN or 1 μM rotenone were also added and maintained during the remainder of the experiment. Histamine (100 μM) was added acutely in control experiments. CoroNa Green AM, ANG2 AM, CoroNa Red and Fluo-4 AM were then washed out and new HBSS + Ca/Mg plus 25 mM glucose was added. For Fluo-4 AM and ANG2 AM imaging, cells were further incubated for 30 min at 37 °C in the dark to allow complete de-esterification of the probe. After this time, the plate was placed into a Leica SP-5 confocal microscope, an automated stage for live imaging and a thermostated hypoxic cabinet. The planes were focused for image capture and images were taken with a ×63 objective. In some experiments, images were taken every 2 min during a 40-min period, providing a total of 21 cycles, and in others every 5 min. Normoxia experiments started and ended at 20% O2 and 5% CO2, whereas hypoxia experiments started at 20% O2 and 5% CO2 and then were switched to 1% O2 and 5% CO2 in cycle one. In other experiments, hypoxia conditions were set at the middle of the protocol, allowing the quantification of the same cells during normoxia and hypoxia. Loaded cells were excited with an argon/krypton laser using the 496-nm line, except CoroNa Red, which was excited with the 514-nm line. Fluorescence emission of Fluo-4 AM, ANG2 AM and CoroNa Green AM was detected in the 515–575-nm range, and the 555–575-nm range for CoroNa Red AM.

To detect intramitochondrial pH, cells were transfected with the ratiometric probe mitosypHer in eight-well plates the day before the experiment. The same protocol as above was used, except that the objective was ×63 and imaging time was 30 min, with 7 cycles of 5 min. Excitation was performed with a 405 diode laser for the 405-nm line and an argon/krypton laser for the 488-nm line, and fluorescence emission was recorded at the 515–535-nm range. Calibration was performed in situ with buffers at pH 6.8, 7, 7.5, 8 and 8.8 in the presence of 5 μM nigericin and 1 μM monensin.

For H2O2 detection, cells were transfected with the non-targeted version of HyPer (pHyPer-cyto) following the same procedure for live imaging as with mitosypHer.

Images were quantified with ImageJ software. A minimun of three independent experiments were performed for each condition. For each experiment and condition in loaded cells, four identical linear ROIs were quantified, and for each time point, the mean of these ROIs was obtained.

For cytosolic Ca2+ detection, cells were transfected with the non-targeted version of GEM-GECO (cyto-GEM-GECO) and seeded in eight-well plates the day before the experiment. In some experiments, HBSS + Ca/Mg + glucose was replaced by HBSS + Mg + glucose osmotically compensated with KCl. The objective was ×63 and the imaging time was 45 min, with 9 cycles of 5 min. Excitation was performed with a 405-diode laser for the 405-nm line, and the fluorescence emission was recorded at 460-nm and 510-nm lines.

For mitochondrial Ca2+ detection, cells were transfected with the mitochondrial-targeted Cepia 2mt and seeded in eight-well plates the day before the experiment. The objective was ×63 and the imaging time was 40 min, with 20 cycles of 2 min. Samples were excited with an argon/krypton laser using the 488-nm line, and the fluorescence emission was detected in the 515–535-nm range.

For endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ detection, cells were transfected with the endoplasmic reticulum-targeted GAP3 (pcDNA3-erGAP3) and seeded in eight-well plates the day before the experiment41. The objective was ×63 and the imaging time was 40 min, with 8 cycles of 5 min. Excitation was performed with a 405-diode laser for the 405-nm line and an argon/krypton laser for the 488-nm line, and the fluorescence emission was recorded at the 495–535-nm range. In some experiments, HBSS + Ca/Mg + glucose was replaced by HBSS + Mg + glucose osmotically compensated with KCl.

Ca2+ calibration was performed in situ by subsequent additions of 100 μM digitonin and 2.5 mM EDTA.

For mitochondrial Na+ detection, cells were washed three times with HBSS + Ca/Mg + glucose, incubated for 1 h with 10 μM CoroNa Green AM, washed three times again with HBSS + Ca/Mg + glucose and incubated for a further hour in HBSS + Ca/Mg + glucose. During this period, CoroNa Green is actively pumped out from the cytosol. Then, after washing three more times with HBSS + Ca/Mg + glucose, cells were placed in the microscope. The objective was ×63 and the imaging time was 25 min, with 15 cycles of 2.5 min. Samples were excited with an argon/krypton laser using the 488-nm line, and the fluorescence emission was detected in the 500–575-nm range.

Calibrations in Ca2+ measurements were performed as previously described42.

Western blot analysis

Protein samples were extracted with non-reducing Laemmli buffer without bromophenol blue and quantified by Bradford assay. Extracts were loaded onto 10% standard polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis after adding 5% 2-mercaptoethanol, and subsequently transferred to nitrocellulose membranes or PVDF membranes. The following antibodies were used: polyclonal anti-NCLX (ab136975, Abcam; ARP44042_P050, Aviva Systems Biology), monoclonal anti-Fp70 (459200, Invitrogen), monoclonal anti-NDUFS4 (ab87399, Abcam), monoclonal anti-RISP (UQCRFS1) (ab14746, Abcam), polyclonal anti-MCU (HPA016480, Sigma-Aldrich) and monoclonal anti-α-tubulin (T6199, Sigma). Antibody binding was detected by chemiluminescence with species-specific secondary antibodies labelled with horseradish peroxidase (HRP), and visualized on a digital luminescent image analyser (Fujifilm LAS-4000), with the exception of ab136975 and 459200, which were detected by fluorescence as previously described43.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from PASMCs using TRIzol reagent (Vitro) and 0.5 μg was reverse-transcribed (Gene Amp Gold RNA PCR Core Kit, Applied Biosystems). PCR was performed with GotaqqPCR Master Mix (Promega) with 1 μL

cDNA and specific primer pairs (Rn01481405_m1). mRNA encoding β-actin was measured as an internal sample control.

Measurement of cellular oxygen consumption

The oxygen consumption rate (OCR) was measured using an XF24 Extracellular Flux Analyzer (Seahorse Bioscience). BAECs, 6 × 104 per well (6–7 wells per treatment for each independent experiment), were plated 1 day before the experiment. Cells were preincubated with unbuffered DMEM supplemented with 25 mM glucose, 1 mM pyruvate and 2 mM glutamine for 1 h at 37 °C in an incubator without CO2 regulation. OCR measurements were programmed with successive injections of unbuffered DMEM, 5 μg/mL oligomycin, 300 nM carbonyl cyanide 4-(trifluoromethoxy) phenylhydrazone (FCCP) and 1 μM rotenone plus 1 μM antimycin A. DMSO or 10 μM CGP-37157 were added before starting the measurements. In experiments using silenced cells, as proliferation and cell growth may vary after plating, protein concentration was quantified by the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay to normalize the OCR. Calculations were performed following the manufacturer’s instructions. After measuring basal respiration, oligomycin was added to inhibit respiration (by blocking H+-ATPase); therefore, the amount of oxygen used to produce ATP by OXPHOS is estimated from the difference with basal oxygen consumption (that is, coupling efficiency). FCCP uncouples OXPHOS by translocating H+ from the intermembrane space to the matrix, thus maximizing electron flux through the electron transport chain (ETC), giving the maximal respiration rate. This treatment provides information about the stored energy in mitochondria that a cell could use in an energetic crisis (that is, reserve capacity). Antimycin A and rotenone block CIII and CI, respectively, consequently inhibiting electron flux through the ETC and eliminating any H+ translocation; thus, the leftover value is non-mitochondrial respiration, that is, the oxygen consumed by other enzymes in the cell.

Fluorescent labelling of ND3 Cys39 from isolated mitochondrial membranes

Mitoplasts were prepared as previously described11. Mitoplasts protein amount was determined by BCA assay and then proteins were solubilized with 4 g/g digitonin, incubated for 5 min on ice and centrifuged for 30 min at 16,000g at 4 °C. Samples were split into two parts: one part was incubated at 37 °C for 60 min to fully deactivate CI and the other part was kept on ice. Samples were then incubated with Bodipy-TMR C5-maleimide (Invitrogen) for 20 min at 15 °C in the dark; then, 1 mM cysteine was added and the samples were further incubated for 5 min. After this time, the samples were precipitated twice with acetone, centrifuged at 9,500g for 10 min at 4 °C in the dark, and the resulting pellet was resuspended in non-reducing Laemmli loading buffer. For each sample, 100 μg were loaded onto 10% tricine-SDS–PAGE gels as previously described44. Total protein staining was performed with Sypro Ruby (Invitrogen). The images of the different fluorophores were obtained using a digital fluorescent image analyser (Fujifilm LAS-4000). Images were quantified using ImageQuant TL7.0 software.

Mitochondria isolation, measurement of total and soluble mitochondrial Ca2+ content and measurement of H2O2 and O2 consumption

Mitochondria were isolated from BAECs with a protocol adapted for cell culture36. Briefly, after resuspending BAECs or MEFs with a sucrose buffer in a glass Elvehjem potter, homogenization was performed by up and down strokes using a motor-driven Teflon pestle. Successive homogenization–centrifugation steps yielded the mitochondria-containing fraction.

Mitochondrial Ca2+ content was measured by incubating isolated mitochondrial fractions from cells that had been subjected to normoxia or hypoxia, in a hypotonic buffer (pH 6.8 for total Ca2+ or pH 7.5 for soluble Ca2+) for 5 min. Then, the amount of Ca2+ was determined by Calcium Green (C3737, Thermo Fisher) fluorescence and calibrated with a CaCl2 calibration curve set at the same pH of the measurement. Excitation/acquisition was performed three times with a 488/535 filter cube in a Fluoroskan Ascent fluorimeter (Thermo Labsystems).

H2O2 production from isolated rat heart mitochondria was performed in an O2k Oxygraph instrument (Oroboros Instruments). Isolated rat heart mitochondria (500 μg) were loaded in KCl buffer with Amplex Red: 150 mM KCl, 10 mM K2HPO4, 1 mM EDTA, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mg/mL BSA, 15 μg/mL HRP, 15 μg/mL superoxide dismutase (SOD) and 25 μM Amplex Red. Recordings started before the addition of substrates: 5 mM glutamate and 5 mM malate; and the indicated amounts of NaCl and/or CaCl2 were subsequently added.

Oxygen consumption was determined with an oxytherm Clark-type electrode (Hansatech) as previously described36. Briefly, isolated mitochondria from BAECs (150 μg), WT MEFs or KO MEFs were resuspended in MAITE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 25 mM sucrose, 75 mM sorbitol, 100 mM KCl, 10 mM K2HPO4, 0.05 mM EDTA, 5 mM MgCl2, and 1 mg/mL BSA) either untreated, treated with 20 mM NaCl and 100 μM CaCl2 or with 20 mM NaCl, 100 μM CaCl2 and 10 μM CGP-37157. Substrates and inhibitors were then successively added: 5 mM glutamate and 5 mM malate, 1 μM rotenone, 10 mM succinate, 2.5 μg/mL antimycin A, 10 mM N,N,N’,N’-tetramethyl-p-phenylenediamine and 10 mM sodium azide. The OCR was obtained by calculating the slope after each treatment. Values for specific complex input were acquired from the subtraction of substrate-less-specific inhibitor rates.

Mitochondrial membrane isolation and complex activity measurement

Mitochondrial membranes from BAECs were obtained after freezing–thawing isolated mitochondria, and OXPHOS enzyme activity was measured as previously described36, using around 50 μg per sample. Briefly, rotenone-sensitive NADH-ubiquinone Q1 oxidoreduction (CI activity) was measured by changes in absorbance at 340 nm. Succinate dehydrogenase (CII) activity was recorded in a buffer containing mitochondrial membranes, succinate and 2,6-dichlorophenol-indophenol (DCPIP) by changes in absorbance at 600 nm. Rotenone-sensitive NADH-cytochrome c activity (CI + CIII activity) was measured by changes in absorbance at 550 nm after NADH addition. Antimycin A-sensitive succinate-CytC activity (CII + CIII activity) was calculated after measuring changes in absorbance at 550 nm. ROS production in CII + CIII activity was monitored by fluorescence of a dichlorofluorescein (DCF) probe. Antimycin A-sensitive ubiquinone 2-cytochrome c activity (CIII activity) was measured by following changes in absorbance at 550 nm. G3PD + CIII activity was measured as for CII + CIII activity but with glycerol-3-phosphate (10 mM) as the electron donor. NaCl was added up to 10 mM and CaCl2 up to 0.1 mM.

Measurement of mitochondrial Na+

In some experiments, cells were preincubated with 10 μM CGP-37157 for 30 min. Then, cells were treated with normoxia or hypoxia (1% O2) for 10 min. Mitochondria were isolated on ice and resuspended in Milli-Q water. The samples were split, one part incubated with benzofuran isophthalate tetra-ammonium salt (SBFI) and the other was used to quantify protein amount by BCA. For SBFI measurements, a calibration curve was used in every measurement and the fluorescence was recorded at 340 nm/380 nm and emission at 520 nm in a FLUOstar Omega Microplate Reader (BMG Labtech).

FRAP

Cells were transfected with pDsRed2-Mito vector (Clontech). Growing media were changed for HBSS + Ca/Mg + glucose ± 10 μM CGP-37157 and the plate placed into a Leica SP-5 confocal microscope, an automated stage for live imaging and a thermostated hypoxic cabinet. The planes were focused for image capture and images were taken with a ×63 objective with ×13 zoom.

Samples were excited with an argon/krypton laser using the 514-nm line and emission was detected in the 565–595-nm range. Images were collected using TCS software (Leica). MitoRFP was scanned five times and then bleached using 15 scans at 40% laser power. To image the recovery of fluorescence intensity after photobleaching, we recorded 60 scans every 1 s. FRAP in normoxia was performed at 20% O2 and 5% CO2, the chamber was then switched to 1% O2 and 5% CO2 and after 25 min FRAP was performed in hypoxia.

Fluorescence quenching recovery after photobleaching

The medium of BAECs was changed for HBSS + Ca/Mg + glucose with 50 nM NAO. In some experiments, 10 μM CGP-37157 was added. The plate placed into a Leica SP-5 confocal microscope, an automated stage for live imaging and a thermostated hypoxic cabinet. The planes were focused for image capture and images were taken with a ×63 objective with ×13 zoom.

Samples were excited with an argon/krypton laser using the 488-nm line and emission was detected in the 515–535-nm range. Images were collected using TCS software (Leica). NAO was scanned two times and then bleached using 15 scans at 20% laser power. To image the quench of fluorescence intensity after photobleaching, we recorded 30 scans every 0.372 s. Quenching recording in normoxia was performed at 20% O2 and 5% CO2, the chamber was then switched to 1% O2 and 5% CO2 and the quench was again recorded after 15 min in hypoxia.

Fourier-transform IR spectroscopy

PC liposomes were prepared using the thin-film hydration method followed by extrusion with filters of decreasing diameter (400, 200 and 100 nm)45. Lipids were hydrated with water with minimal metal impurities (Optima LC/MS Grade, Fisher Chemical). Liposomes were concentrated by filtration up to 72 mg/mL of lipid content. Lipid concentration was determined through the Rouser assay46. Sodium salt was mixed and incubated at 37 °C (for 2 h) with the liposomes at a ratio of 16 mM X+:0.5 mg/mL lipids. Fourier-transform IR spectra of liposomes and liposomes incubated with alkali metals were collected afterwards with a Nicolet 6700 Fourier-transform IR spectrometer (Thermo Scientific) in transmission mode in liquid samples. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Inductively coupled plasma mass spectroscopy

PC liposomes were mixed and incubated at 37 °C (for 2 h) with sodium chloride salt at a ratio of 16 mM X+:0.5 mg/mL lipids. Thereafter, solutions were washed by filtration with Optima LC/MS Grade water and digested with HNO3 acid ([Na+] = 13 ppt, nitric acid Optima, for ultra-trace elemental analysis, Fisher Chemicals). The number of alkali cations bound to each lipid within the liposomes, after three washing steps, was determined with inductively coupled plasma mass spectroscopy iCAP-Q from Thermo Scientific equipped with a collision/reaction cell and kinetic energy discrimination. Lipid concentration was determined through the Rouser assay46. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Transmission electron microscopy

Electron microscopy of cells and isolated mitochondria were performed as previously described47 and thin sections were imaged on a Tecnai-20 electron microscope (Philips-FEI). Quantification of area and frequency of electron-dense spots was performed manually and using ImageJ software.

TEM–EDX analysis

Cell samples were fixed using 4% formaldehyde (EMS) and 2.5% glutaraldehyde (Sigma) in 0.1 M HEPES for 4 h at 4 °C. Samples were post-fixed 1 h at room temperature in a 2% osmium tetroxide (EMS) and 3% potassium ferrocyanide (Sigma) solution. Cell preparations were dehydrated through graded acetone series and embedded in Spurr’s low viscosity embedding mixture (EMS). Ultrathin sections (70 nm) were then mounted on formvar-coated copper grids and stained with lead citrate. Samples were examined on a JEOL JEM 1400 with silicon drift detector) and elemental content estimation was performed under 80,000–100,000 magnification and using 50–100-s lifetime acquisition. Data on oxygen (O), carbon (C), lead (Pb) and calcium (Ca) were collected from the TEM–EDX analysis. C, O and Pb were used as controls.

Measurement of the redox state of ubiquinone

The ratio of the oxidized and reduced forms of ubiquinone (CoQ) were measured as described48–50. CGP-37157 or antimycin A (10 μM) was added 30 min before the experiment and maintained throughout. HUVECs with or without CGP-37157 were subjected to 10 min of hypoxia (1% O2) or normoxia. Antimycin A was used in normoxic cells as a control. Plates were washed three times with ice-cold PBS and the cells were transferred to ice-cold tubes, which were subsequently centrifuged at 2,000g for 5 min at 4 °C. Cell pellets were resuspended in 95 μL PBS from which 91.5 μL was taken and mixed with 3.5 μL of 14.3 μM 2-mercaptoethanol. 5 μL of 10 μM CoQ6 were added as internal standard. Then, 330 μL 1-propanol was added, the sample vortexed for 30 s, incubated for 3 min at room temperature, vortexed again for 20 s and centrifuged at 14,000g for 5 min. Supernatant (100 μL) was immediately injected into a 166–126 HPLC system (Beckman Coulter) equipped with an UV/Vis detector (System Gold R 168, Beckman Coulter) and an electrochemical (Coulochem III ESA) detector. Separation was carried out in a 15-cm Kromasil C18 column (Scharlab) at 40 °C with a mobile phase 20 mM ammonium acetate, pH 4.4, in methanol (solvent A) and 20 mM ammonium acetate, pH 4.4, in propanol (solvent B). A gradient method was used with a 85:15 solvent mixture (A:B ratio) and a flow rate of 1.2 mL/min as the starting conditions. The mobile phase turns to a 50:50 A:B ratio starting at minute 6 and completed in minute 8, and the flow rate decreases in parallel to 1.1 mL/min. After 20 min (run time), the columns are re-equilibrated to the initial conditions for 3 additional min. UV-spectrum was used to identify the different forms of ubiquinone (oxidized CoQ10 with maximum absorption at 275 nm) and ubiquinol (reduced CoQ, CoQ10H2, with maximum absorption at 290 nm) using specific standards. Quantification was carried out with electrochemical detector readings (channel 1 set to −700 mV and channel 2 set to +500 mV, conditioning guard cell after injection valve).

ESR of lipid vesicles

ESR spectroscopy is particularly useful to investigate the rotational dynamics of labelled molecules in solutions or membranes. The rotational dynamics timescale, τc, is inversely related to the fluidity of the microenvironment of the probe. ESR experiments were carried out with a 9.5 GHz ESR Bruker spectrometer (RSE Bruker EMX). DOPC unilamellar vesicles (2 mM) were obtained by ultrasonication. The spin labels (0.25% mol of total lipid composition) were added to the dry lipids before vesicle formation to obtain a symmetrical distribution of probes in the two leaflets. We used 5-doxyl palmitoyl PC (5-doxyl PC), 12-doxyl PC and 16-doxyl PC. The different position of the probe along the alkyl chain determines the local motional profiles in the three main regions of the lipidic bilayer, near the polar head group (5-doxyl PC), at the middle region of the hydrophobic chain (12-doxyl PC) or at the end of the hydrophobic chain (16-doxyl PC). The ESR spectrum of 5-doxyl PC incorporated into the lipid membranes made of DOPC shows an anisotropic (slow) motion, whereas those of both 12-doxyl PC and 16-doxyl PC reflects an isotropic motion of the acyl chain. The τc of 5-doxyl PC is proportional to the outermost separation between the spectral extrema, 2Amax, whereas the τc of 12-doxyl PC and 16-doxyl PC were calculated by the semiempirical formula previously established51: τc = 6.5 × 10−10 ΔB0 (√(h0/h−1) − 1), where ΔB0 is the width of the central line in Gauss, and h0 and h−1 are the heights of the mid-field and high-field lines, respectively. 2Amax, ΔB0, h0 and h−1 were obtained from the first derivative of each absorption spectrum.

Steady-state fluorescence emission anisotropy of DPH or TMA-DPH incorporated into lipid vesicles

Mixtures of 1–3 mg of egg PC (Avanti Polar Lipids Inc.), cardiolipin (CL; Avanti Polar Lipids Inc.) to a final molar PC:CL molar ratio of 4:1 (when present), and the fluorescent lipid probes diphenyl-1,3,5-hexatriene (DPH; Sigma-Aldrich) or 1-(4(trimethylammonium)-phenyl)-6-DPH (TMA-DPH; Sigma-Aldrich), at a lipid:probe molar ratio of 1:100, were dissolved in 200 μL of chloroform:methanol (2:1) and dried under flow of nitrogen for at least 60 min. The resulting dry lipid film was then resuspended in 1.5 mL of Milli-Q-degree water and vortexed vigorously for 1 min. This suspension of multilamellar vesicles was then incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. Large unilamellar vesicles were then prepared by extrusion of this lipid dispersion through polycarbonate filters of controlled 100-nm diameter pore size. These vesicles were maintained at 37 °C for no more than 3 h before being used52. The steady-state fluorescence emission anisotropy experiments were carried out on a SLM Aminco 8000C spectrofluorimeter (SLM Aminco), as previously described53. Fluorescence anisotropy (r) of DPH or TMA-DPH incorporated into the liposomes described above was recorded at 37 °C using excitation and emission wavelengths of 350 or 356 and 452 or 451 nm, respectively.

Measurement of pulmonary artery contraction

Third division branches of the pulmonary arteries were isolated from male Wistar rats (250–275 g of body weight; obtained from Envigo) and mounted in a wire myograph. Contractile responses were recorded as reported54. The chambers were filled with Krebs buffer containing 118 mM NaCl, 4.75 mM KCl, 25 mM NaHCO3, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 2 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM KH2PO4 and 11 mM glucose, maintained at 37 °C and aerated with 21% O2, 5% CO2 and 74% N2 gas (pO2 17–19 kPa). After an equilibration period of 30 min, pulmonary arteries (internal diameter of 300–400 μm) were distended to a resting tension corresponding to a transmural pressure of 2.66 kPa. Preparations were initially stimulated by raising the K+ concentration of the buffer (to 80 mM) in exchange for Na+. Vessels were washed three times and allowed to recover. Then, following randomization, each vessel was exposed to two hypoxic challenges (95% N2, 5% CO2; pO2 = 2.6–3.3 kPa), the second one after 40 min of incubation with vehicle (control) or CGP-37157 (30 μM).

Statistics

Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m., except where otherwise stated. Normality and homoscedasticity tests were carried out before applying parametric tests. For comparison of multiple groups, we performed one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s or Bonferroni’s tests for all of the groups of the experiment. For comparison of two groups, we used Student’s two-tailed t-test; when the data did not pass the normality test, we used a non-parametric t-test (Mann–Whitney U-test). Linear correlation was estimated by calculating the Pearson’s correlation coefficient. Variations were considered significant when the P value was less than 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed with SigmaPlot 11.0 or GraphPad Prism 8 software.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this paper.

Data availability

Data generated in this study are available in a public repository at Mendeley Data (https://doi.org/10.17632/5wmggsb5vh.1). Source data are provided with this paper.

Extended Data

Extended Data Fig. 1 |. Interference of Slc8b1 affects NCLX function, but inhibition of the NCLX has no effect on general mitochondrial function.

a–c, Assessment of the effect of different siRNAs against Slc8b1 mRNA (siNCLX) on mitochondrial Ca2+ influx and efflux rates in BAECs transfected with the mitochondria-directed Ca2+ reporter protein Cepia 2mt (siSCR n = 4, siNCLX1 n = 5, siNCLX2 n = 4, siNCLX3 n = 3, siNCLX4 n = 5), after addition of histamine; mean traces plotted as fluorescence change relative to initial fluorescence (F/F0) (a); mitochondrial Ca2+ peak amplitude (calculated from the highest value of fluorescence minus the first basal value of fluorescence, from panel a) (b); percentage of mitochondrial Ca2+ efflux (calculated from the highest value of fluorescence minus the lowest value of fluorescence after histamine application, relative to percental siSCR values, from panel a) (c). d, Assessment of NCLX protein amount after interference in whole-cell extracts from BAECs, by western blot (Representative image of three independent experiments). e–g, Mitochondrial Ca2+ influx and efflux rates in WT, NCLX KO, KO+pNCLX or WT+dnNCLX MEFs transfected with Cepia 2mt (n = 4, except WT n = 5 and KO+pNCLX n = 3) after addition of histamine, as in a–c. h–j, Assessment of NCLX protein amount in MEFs mitochondrial extracts by western blot (representative images of n = 4 in h and n = 2 in i and j). k, Mitochondrial membrane potential in BAECs measured with 20 nM TMRM in non-quenching mode (n = 3). l, Oxygen consumption rate (OCR) in BAECs with NCLX inhibition by 10 μM CGP-37157 (upper panel, n = 4), or NCLX interference with siNCLX1 (lower panel, n = 3). All data are represented as mean ± s.e.m. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test (f, g and k for the siNCLX inset) and two-tailed Student’s t-test (b, c, k for the CGP inset). For gel source data, see Supplementary Fig. 1.

Extended Data Fig. 2 |. Hypoxia activates Na+/Ca2+ exchange through the NCLX.

Cytosolic Ca2+ (Ca2+i) or Na+ (Na+i) were measured by live imaging fluorescence microscopy with Fluo-4 AM or CoroNa Green AM, respectively, in normoxia or acute hypoxia (2% O2). a–d, BAECs not treated (No treat) or transfected with siSCR or siNCLX. e–h, BAECs treated or not with the NCLX inhibitor CGP-37157 (10 μM). a, c, e, g, time-course traces; b, d, f, h, slopes. All data are represented as mean ± s.e.m. of n = 3 independent experiments. Two-tailed Student’s t-test (b, d, f, h): * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, n.s. not significant.

Extended Data Fig. 3 |. Inhibition of the NCLX prevents the increase in ROS production triggered by hypoxia.

a–c, Superoxide detection by fluorescence microscopy after incubation with DHE in 10-min time windows in normoxia (Nx) or hypoxia (1% O2); AA = antimycin A. BAECs treated or not with 10 μM CGP-37157, images of one experiment (a) and mean intensity of three independent experiments (b). HUVECs treated or not with 10 μM CGP-37157, mean intensity of three independent experiments (c). d, Detection of H2O2 by live confocal microscopy in CytoHyPer-transfected BAECs either not treated or treated with 10 μM CGP-37157 in normoxia (Nx) or acute hypoxia (1% O2, Hp); representative images and time-course traces as mean of four independent experiments. e, Detection of ROS by live fluorescence microscopy with DCFDA in normoxia or acute hypoxia (2% O2); time-course traces and slopes, mean of three independent experiments. f, g, Superoxide detection by fluorescence microscopy with DHE in normoxia (Nx) or 10 min hypoxia (1% O2) or normoxia with AA in primary (f) or immortalized (g) HUVECs; mean of three independent experiments. All data are represented as mean ± s.e.m. Two-tailed Student’s t-test for pairwise comparisons (d, e) and one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons (b, c, f, g): n.s. not significant, * P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001. In b, c, statistical comparisons shown only for Nx vs 0–10 groups.

Extended Data Fig. 4 |. NCLX activation in acute hypoxia depends on mitochondrial CI.

a, b, Assessment of interference of subunits of CI (NDUFS4) or CIII (RISP) by western blot in whole-cell extracts from BAECs. Representative images of two independent experiments. c, d, Cytosolic Ca2+ (Ca2+i; c) or Na+ (Na+i; d) measured by live imaging confocal microscopy with Fluo-4 AM or CoroNa Green AM, respectively, in normoxia or acute hypoxia (1% O2); time-course traces and slopes, n = 4 (c), n = 3 (d). e, f, Effect of OXPHOS inhibitors on cytosolic Ca2+ (e; n = 3) or Na+ (f; n = 6) measured as in c and d. All data are represented as mean ± s.e.m. Two-tailed Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney U test (c; siSCR). n.s. not significant, * P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. For gel source data, see Supplementary Fig. 1.

Extended Data Fig. 5 |. Acute hypoxia promotes A/D transition in CI and matrix acidification independently of NCLX activity.

a–c, ND3·Cys39 exposure, which reflects the D conformation of CI, measured as the ratio between TMR signal (Cys39 labelling) and Sypro Ruby staining (total protein for the ND3 band, identified by mass spectrometry11). Thermal deactivation is used as a positive control of CI D state. Scheme of the technique11 (a); BAECs (b; n = 5 and n = 4 for de-activated samples) or HepG2 (c; n = 2) exposed to normoxia (Nx), 5 min of hypoxia (1% O2, H5), normoxia with CGP-37157 (NxCGP), 5 min of hypoxia with CGP-37157 (H5CGP). d, Complex I reactivation rate measured in the presence of Mg2+ in isolated mitochondrial membranes from BAECs subjected to normoxia, 10 min of hypoxia (1% O2) and NCLX inhibition with CGP-37157 (n = 4). e–g, Mitochondrial matrix pH measured using calibrated mitosypHer in WT or CI KO cybrid cell lines (e; n = 8), MEFs preincubated or not with rotenone (f; n = 4) or NCLX WT or KO MEFs (g; n = 8). h, Mitochondrial matrix acidification using mitosypHer in BAECs in normoxia or acute hypoxia (1% O2) treated or not with NCLX inhibitor CGP-37157; time-course traces and slopes (n = 4). i, j, Effect of the CI inhibitor rotenone on cytosolic Ca2+ (i) or cytosolic Na+ ( j) measured by live confocal microscopy with Fluo-4 AM or CoroNa Green AM, respectively, in BAECs in normoxia or acute hypoxia (1% O2), n = 3. All data are represented as mean ± s.e.m. Two-tailed Student’s t-test (b, d, h, i, j): n.s. not significant, * P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001.

Extended Data Fig. 6 |. Mitochondrial matrix acidification promotes mitochondrial Na+/Ca2+ exchange via the NCLX.

a, TEM-EDX determination of calcium element (Ca) versus carbon (C), oxygen (O) and lead (Pb) content in regions of mitochondria with (empty circles) or without (filled circles) electron dense spots (n = 7). b, Frequency of CaP precipitates per mitochondrion in BAECs, seen by TEM during normoxia (741 mitochondria), 10 min of hypoxia (1% O2; 619 mitochondria) or 30 min with 1 μM FCCP (393 mitochondria), three independent experiments. c, Total Ca2+ content of mitochondria extracted from mouse adult fibroblasts (MAFs) which had been treated for 10 min with 1 μM FCCP or 1 μM rotenone, measured in a hypotonic buffer at pH 6.8 (n = 4). d, Western blot showing MCU and Fp70 in CRISPR Control, MCU KO2 and MCU KO3 cells (representative image of two independent experiments). e, Mitochondrial Ca2+ measured by live cell confocal microscopy in MCU WT or KO human breast cancer cells transfected with Cepia2mt (fluorescence signal relative to starting signal –F/F0–, representative traces of n = 5 for WT, n = 9 for MCU KO2 and n = 5 for KO3, independent experiments). f, Total Ca2+ content of mitochondria extracted from MAFs which had been subjected to normoxia or 10, 30 or 60 min of hypoxia (1% O2), measured in a hypotonic buffer at pH 6.8 (n = 5). g, Ca2+ content of mitochondria extracted from MAFs which had been subjected to 10 min normoxia or 10 min hypoxia (1% O2) in a medium without Ca2+, measured in a hypotonic buffer at pH 6.8 (total mitochondrial Ca2+) or pH 7.5 (soluble mitochondrial Ca2+; n = 4). h, Cytosolic Ca2+ measured by live cell confocal microscopy in MEFs transfected with cyto-GEM-GECO in the absence of Ca2+ in the incubation medium (n = 4). i, Endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ measured by live cell confocal microscopy in MEFs transfected with erGAP3 in the presence or absence of Ca2+ in the incubation medium (n = 8). j, Superoxide detection with DHE in MCU WT or MCU KO immortalized breast cancer cells in normoxia (Nx) or after 10 min of hypoxia (1% O2; Hp; n = 4). All data except e are represented as mean ± s.e.m. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test (c and f) and two-tailed Student’s t-test (a, b, g and j): n.s. not significant, * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01. Two-tailed Student’s t-test (CRISPR Control Hp vs MCU KOs Hp in j): & P < 0.05, && P < 0.01. For gel source data, see Supplementary Fig. 1.

Extended Data Fig. 7 |. Mitochondrial Na+ import decreases OXPHOS and produces ROS.

a, Effect of NaCl and/or CaCl2 additions on H2O2 production detected with Amplex Red in isolated rat heart mitochondria (500 μg) respiring after addition of glutamate/malate (GM) in KCl-EGTA buffer. Representative traces of five independent experiments. b–e, Effect of NCLX activation by 10 mM NaCl/0.1 mM CaCl2 on glutamate/malate- (b, d) or TMPD-based (c, e) oxygen consumption rate (OCR) in isolated coupled mitochondria from BAECs (b, c; n = 5) or MEFs (d, e; n = 6). f, g, Effect of 0.1 mM CaCl2 (f; n = 5) or NaCl (g; n = 4) additions on CII+III activity in isolated mitochondrial membranes from BAECs. h, i, Cytosolic Ca2+ (h) or cytosolic Na+ (i) measured by live cell confocal microscopy of BAECs transfected with cyto-GEM-GECO (h) or treated with ANG2-AM (i), either not treated (No treat) or treated with 10 μM DMM during normoxia and hypoxia (1% O2; n = 4). j, Superoxide detection by fluorescence microscopy after incubation with DHE in 10-min time windows in non-treated BAECs (No treat) or treated with 10 μM DMM during normoxia (Nx) or hypoxia (1% O2; n = 3, except AA n = 2). k, l, Effect of 10 mM NaCl addition on succinate dehydrogenase activity (k) or ubiquinone 2-cytochrome c activity in the presence of n-Dodecyl β-D-maltoside (DDM; l) from BAECs mitochondrial membranes (n = 4). m, n, Effect of hypoxia (1% O2) in mitochondrial Na+ content measured with SBFI in BAECs transfected with siSCR or siNCLX (m) or treated with CGP-37157 (n) (n = 4). o, Effect of hypoxia (1% O2) in mitochondrial Na+ content in WT and KO MEFs, measured with CoroNa Green adapted for mitochondrial loading and live fluorescence (n = 10 MEFs WT and n = 12 MEFs KO). p, Representative images of three independent experiments showing colocalization of CoroNa Green-AM and TMRM signals after application of a long incubation protocol for CoroNa Green AM. All data are represented as mean ± s.e.m. Two-tailed Student’s t-test (f, k, l) and one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons (b–e, h–j, m–o): n.s. not significant, * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001. Student’s t-test (No treat vs DMM; h, i): n.s. not significant, & P < 0.05. j, statistical comparisons shown only for Nx vs 0–10 groups. Pearson correlation coefficient in g: R = −0.9753.

Extended Data Fig. 8 |. Mitochondrial Na+ import decreases IMM fluidity.

a, FRAP of BAECs expressing mitoRFP in normoxia or hypoxia for 20 min (1% O2), with or without CGP-37157 (n = 15 for Nx, n = 16 for Hp, n = 13 for NxCGP and n = 10 for HpCGP, obtained from four independent experiments). b, NAO quench FRAP signal of BAECs exposed to normoxia or hypoxia for 15 min (1% O2; n = 5), with or without CGP-37157. c, CoQ10 redox state of HUVECs subjected to normoxia (Nx), 10 min of hypoxia (Hp 10 min; 1% O2), or normoxia with antimycin A (AA), n = 4. d, e, Anisotropy of phosphatydilcholine (PC) or PC:cardiolipin (PC:CL) liposomes treated with increasing concentrations of NaCl measured by TMA-DPH (d; n = 3) or DPH (e; n = 4) fluorescence. f–i, ESR spectra of 5-, 12- and 16-Doxyl PC in DOPC liposomes. 5-Doxyl PC exhibited an increased restricted motion (broadening of the hyperfine splitting, 2Amax) as a function of the NaCl concentration whereas the correlation time for 12- and 16-Doxyl PC remained unchanged. Hyperfine splitting (2Amax) of 5-Doxyl PC measured by ESR in PC liposomes treated with increasing concentrations of NaCl (n = 2) (f). Chemical structures of 5-, 12- and 16-Doxyl PC (g). ESR of 5-, 12- and 16-Doxyl PC in PC liposomes (h) and rotational times (i), τc, of 12- and 16-Doxyl PC in PC liposomes treated with increasing concentrations of NaCl as measured by ESR (n = 2). j, IR spectroscopy absorption spectra of PC liposomes treated or not with 16 mM NaCl (n = 2). Data are represented as mean ± s.e.m., except mean ± s.d. in d–f and i. Two-tailed Student’s t-test (c) and one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test (a, b, d, e): n.s. not significant, * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001.

Extended Data Fig. 9 |. Mitochondrial Na+ influx inhibition abolishes hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction.

a, Effectiveness of NCLX silencing in mice pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (PASMCs) measured by quantitative RT–PCR analysis, n = 3. b, Superoxide detection by fluorescence microscopy after incubation with DHE in PASMCs treated with siSCR or siNCLX in normoxia (Nx) or hypoxia (Hp; 1% O2), n = 4 (except AA, n = 2). c, d, Representative traces (c) and average values (d) of hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction (HPV) measured in rat pulmonary arteries in the absence of pretone (precontraction). Each artery was exposed twice to hypoxia, and the second hypoxic challenge was performed in the absence or the presence of 30 μM CGP-37157, n = 7 (except peak CGP, n = 8; steady state CGP, n = 9). All data are represented as mean ± s.e.m. One-group t-test vs. 1 (a), two-tailed Student’s t-test (a, d) and one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test (b): * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001. In b, statistical comparisons shown only for Nx vs 0–10 groups.

Extended Data Fig. 10 |. Scheme of the molecular pathway driving ROS production in acute hypoxia.

a, Complex I undergoes the A/D transition, this leads to mitochondrial matrix acidification and free Ca2+ release from the CaP precipitates. b, The increase in mitochondrial matrix free Ca2+ activates NCLX which introduces Na+ into the mitochondrial matrix. c, Na+ interacts with phospholipids in the inner leaflet of the inner mitochondrial membrane, decreasing diffusion of CoQH2, uncoupling CoQ cycle only in free complex III and promoting superoxide production at the Qo site of complex III. d, Mitochondrial ROS in hypoxia activate downstream targets. In addition, the entry of extracellular Ca2+ promotes a positive feed-back loop that further increases mitochondrial Na+ import and ROS production in hypoxia.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank M. Kowalewski (Institute of Veterinary Anatomy, UZH) for allowing us the use of the microscope for live-cell imaging; A. Alfuzzi, J. Prieto, A. Mellado (IIS-IP) and B. Barreira (CIBERES) for collaboration in experiments; E. Fuertes-Yebra (IIS-IP) for technical assistance; M. E. Soriano and F. Caicci (University of Padova) for performing electron microscopy; R. Rizzuto and D. De Stefani (University of Padova) for MCU KO and control cell lines; M. T. Alonso (IBGM, University of Valladolid and CSIC) for the pcDNA3-erGAP3 plasmid; J. Langer from CIC biomaGUNE for fruitful discussion and support with the IR spectroscopy measurements; I. Sekler (Ben-Gurion University), C. Rueda and J. Satrústegui (CMBSO, UAM-CSIC) for providing plasmids and other material and for helpful discussions; M. Cano and A. G. García (IIS-IP and UAM), M. Murphy (MRC and University of Cambridge), I. Wittig (Goethe Universität), J. Miguel Mancheño (IQFR, CSIC), A. Pascual and J. López-Barneo (IBIS, US-CSIC) for helpful discussions; and L. del Peso (UAM) and F. Sánchez-Madrid (IIS-IP and UAM) for their support. This research has been financed by Spanish Government grants (ISCIII and AEI agencies, partially funded by the European Union FEDER/ERDF) CSD2007–00020 (RosasNet, Consolider-Ingenio 2010 programme to A.M.-R. and J.A.E.); CP07/00143, PS09/00101, PI12/00875, PI15/00107 and RTI2018–094203-B-I00 (to A.M.-R.); CP12/03304 and PI15/01100 (to L.M.); CP14/00008, CPII19/00005 and PI16/00735 (to J.E.); SAF2016–77222-R (to A. Cogolludo); PI17/01286 (to P.N.); SAF2015–65633-R, RTI2018–099357-B-I00 and CB16/10/00282 (to J.A.E.); RTI2018–095793-B-I00 (to M.G.L.); and SAF2017–84494-2-R (to J.R.-C.), by the European Union (ITN GA317433 to J.A.E. and MC-CIG GA304217 to R.A.-P.), by grants from the Comunidad de Madrid B2017/BMD-3727 (to A. Cogolludo) and B2017/BMD-3827 (to M.G.L.), by a grant from the Fundación Domingo Martínez (to M.G.L. and A.M.-R.), by the Human Frontier Science Program grant HFSP-RGP0016/2018 (to J.A.E.), by grants from the Fundación BBVA (to R.A.-P. and J.R.-C.), by the UCM-Banco Santander grant PR75/18–21561 (to A.M.-d.-P.), by the Programa Red Guipuzcoana de Ciencia, Tecnología e Información 2018-CIEN-000058–01 (to J.R.-C.) and from the Basque Government under the ELKARTEK Program (grant no. KK-2019/bmG19 to J.R.-C.), by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNF) grant 310030_124970/1 (to A.B.), by a travel grant from the IIS-IP (to P.H.-A.) and by the COST actions TD0901 (HypoxiaNet) and BM1203 (EU-ROS). The CNIC is supported by the Pro-CNIC Foundation and is a Severo Ochoa Center of Excellence (Spanish Government award SEV-2015–0505). CIC biomaGUNE is supported by the María de Maeztu Units of Excellence Program from the Spanish Government (MDM-2017–0720). P.H.-A. was a recipient of a predoctoral FPU fellowship from the Spanish Government. E.N. is a recipient of a predoctoral FPI fellowship from the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid (UAM). A.M.-R., L.M. and J.E. are supported by the I3SNS or ‘Miguel Servet’ programmes (ISCIII, Spanish Government; partially funded by the FEDER/ERDF).

Footnotes

Online content

Any methods, additional references, Nature Research reporting summaries, source data, extended data, supplementary information, acknowledgements, peer review information; details of author contributions and competing interests; and statements of data and code availability are available at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2551-y

Competing interests The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2551-y.

Peer review information Nature thanks Israel Sekler and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

References

- 1.Sena LA & Chandel NS Physiological roles of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Mol. Cell 48, 158–167 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shadel GS & Horvath TL Mitochondrial ROS signaling in organismal homeostasis. Cell 163, 560–569 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dan Dunn J, Alvarez LA, Zhang X & Soldati T Reactive oxygen species and mitochondria: a nexus of cellular homeostasis. Redox Biol 6, 472–485 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chouchani ET et al. Ischaemic accumulation of succinate controls reperfusion injury through mitochondrial ROS. Nature 515, 431–435 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guzy RD & Schumacker PT Oxygen sensing by mitochondria at complex III: the paradox of increased reactive oxygen species during hypoxia. Exp. Physiol 91, 807–819 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fernández-Agüera MC et al. Oxygen sensing by arterial chemoreceptors depends on mitochondrial complex I signaling. Cell Metab 22, 825–837 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hernansanz-Agustín P et al. Acute hypoxia produces a superoxide burst in cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med 71, 146–156 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sylvester JT, Shimoda LA, Aaronson PI & Ward JP Hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction. Physiol. Rev 92, 367–520 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wolf SG et al. 3D visualization of mitochondrial solid-phase calcium stores in whole cells. eLife 6, e29929 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bers DM, Barry WH & Despa S Intracellular Na+ regulation in cardiac myocytes. Cardiovasc. Res 57, 897–912 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hernansanz-Agustín P et al. Mitochondrial complex I deactivation is related to superoxide production in acute hypoxia. Redox Biol 12, 1040–1051 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luongo TS et al. The mitochondrial Na+/Ca2+ exchanger is essential for Ca2+ homeostasis and viability. Nature 545, 93–97 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamanaka RB & Chandel NS Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species regulate cellular signaling and dictate biological outcomes. Trends Biochem. Sci 35, 505–513 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Babot M, Birch A, Labarbuta P & Galkin A Characterisation of the active/de-active transition of mitochondrial complex I. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1837, 1083–1092 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhu J, Vinothkumar KR & Hirst J Structure of mammalian respiratory complex I. Nature 536, 354–358 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fiedorczuk K et al. Atomic structure of the entire mammalian mitochondrial complex I. Nature 538, 406–410 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greenawalt JW, Rossi CS & Lehninger AL Effect of active accumulation of calcium and phosphate ions on the structure of rat liver mitochondria. J. Cell Biol 23, 21–38 (1964). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chandel NS et al. Reactive oxygen species generated at mitochondrial complex III stabilize hypoxia-inducible factor-1α during hypoxia: a mechanism of O2 sensing. J. Biol. Chem 275, 25130–25138 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]