Abstract

Objectives

Estimates of depression prevalence in pregnancy and postpartum are based on the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) more than on any other method. We aimed to determine if any EPDS cutoff can accurately and consistently estimate depression prevalence in individual studies.

Methods

We analyzed datasets that compared EPDS scores to Structured Clinical Interview for DSM (SCID) major depression status. Random‐effects meta‐analysis was used to compare prevalence with EPDS cutoffs versus the SCID.

Results

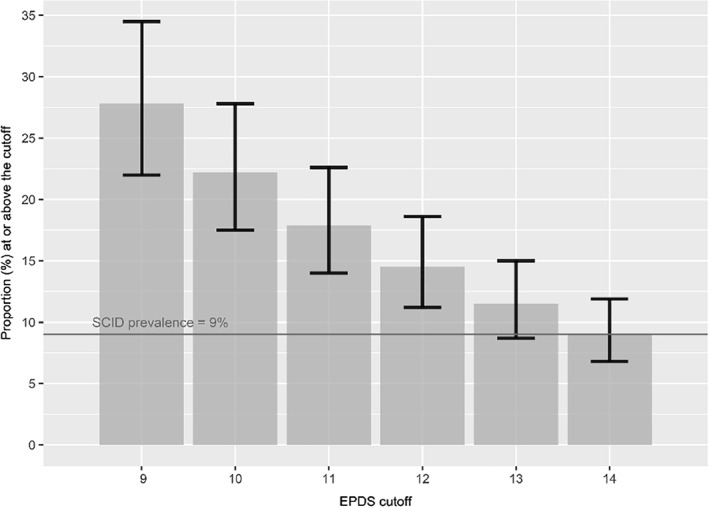

Seven thousand three hundred and fifteen participants (1017 SCID major depression) from 29 primary studies were included. For EPDS cutoffs used to estimate prevalence in recent studies (≥9 to ≥14), pooled prevalence estimates ranged from 27.8% (95% CI: 22.0%–34.5%) for EPDS ≥ 9 to 9.0% (95% CI: 6.8%–11.9%) for EPDS ≥ 14; pooled SCID major depression prevalence was 9.0% (95% CI: 6.5%–12.3%). EPDS ≥14 provided pooled prevalence closest to SCID‐based prevalence but differed from SCID prevalence in individual studies by a mean absolute difference of 5.1% (95% prediction interval: −13.7%, 12.3%).

Conclusion

EPDS ≥14 approximated SCID‐based prevalence overall, but considerable heterogeneity in individual studies is a barrier to using it for prevalence estimation.

Keywords: depression prevalence, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale, structured clinical interview for DSM, individual participant data meta‐analysis, major depression

1. INTRODUCTION

Accurate estimates of depression prevalence are necessary to understand disease burden and allocate healthcare resources. Validated diagnostic interviews, such as the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (Wittchen, 1994) and the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM (SCID) (First & Gibbon, 2004) are designed to classify major depression and estimate depression prevalence in a manner consistent with diagnostic criteria. However, administering validated diagnostic interviews to samples that are large enough to estimate prevalence is resource‐intensive. Thus, many researchers administer self‐report depression symptom questionnaires, or screening tools, instead, and report the percentage above a cutoff threshold as the prevalence of depression (Levis et al., 2019b; Thombs, Kwakkenbos, Levis, & Benedetti, 2018).

Some items included in self‐report questionnaires address similar symptoms as those evaluated in validated diagnostic interviews, but most questionnaires do not evaluate all relevant symptoms, and most include other items that are not part of diagnostic criteria. Furthermore, unlike validated diagnostic interviews, self‐report questionnaires do not include historical information necessary for differential diagnosis, investigate non‐psychiatric medical conditions that can cause similar symptoms to those of depression, assess functional impairment related to symptoms, or verify that symptoms are not an expected reaction to losses or stressors (Thombs et al., 2018).

Depression screening tools are designed to cast a wide net and identify individuals who may have depression. Individuals who screen positive on depression screening tools must be further evaluated by a trained health care professional to confirm whether diagnostic criteria are met. Based on sensitivity and specificity estimates for common depression screening tools and cutoff thresholds, if depression screening tools are used to attempt to estimate prevalence rather than identify individuals who may have depression, most would be expected to overestimate prevalence compared to actual diagnoses (Levis et al., 2019b; Thombs et al., 2018).

A recent study that examined 69 meta‐analyses of depression prevalence found that 44% of pooled prevalence estimates in meta‐analysis abstracts were based solely on screening or rating tools and 46% on a combination of screening tools and other methods (e.g., unstructured interviews, medical charts); only 10% were based solely on diagnostic interviews (Levis et al., 2019b). Among 2094 primary studies included in the meta‐analyses, 77% used screening or rating tools, whereas only 13% used validated diagnostic interviews exclusively. Meta‐analyses based solely on screening or rating tools reported an average depression prevalence of 31% compared to 17% in meta‐analyses based solely on diagnostic interviews.

The degree to which screening questionnaires overestimate the true prevalence depends on the specific depression screening tool and cutoff threshold used (Levis et al., 2019b; Thombs et al., 2018). To date, we are aware of only one study that has directly compared prevalence based on a specific screening tool and cutoff threshold to prevalence based on a validated diagnostic interview for major depression (Levis et al., 2020). That study, an individual participant data meta‐analysis (IPDMA), included 9242 participants from 44 primary studies who were administered both the Patient Health Questionnaire‐9 (PHQ‐9) and the SCID diagnostic interview and found that prevalence based on the standard PHQ‐9 cutoff of ≥10 was 25% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 21%–30%), compared to 12% (95% CI: 10%–15%) based on the SCID. The study also reported that no PHQ‐9 cutoff consistently matched prevalence based on the SCID in individual studies.

The 10‐item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) (Cox, Holden, & Sagovsky, 1987) is the most commonly used depression screening tool for women in pregnancy or postpartum (Hewitt et al., 2009; Howard et al., 2014). It was designed for assessing symptoms continuously, for providing information for discussion for patients, and to identify women who may benefit from formal mental health assessment (Cox et al., 1987). We reviewed 53 recently published studies that stated in their title or abstract that they assessed prevalence of “depression”, “depressive disorders”, “major depression” or “major depressive disorder”. We excluded any that stated that they reported the prevalence of “depressive symptoms” or similar terms. We found that only 6 (11%) used a validated diagnostic interview designed for this purpose. There were 26 (49%) studies that used the EPDS and 21 studies that used other methods, mostly other questionnaires. Studies that reported prevalence based on the EPDS used cutoff thresholds from ≥9 to ≥14, with the majority using cutoffs of ≥10 and ≥ 13 (see Supplementary material, Methods S1 and Table S1). The extent to which prevalence estimates based on different EPDS cutoffs may differ from prevalence based on validated diagnostic interviews, however, is unknown.

The aim of the present study was to use an IPDMA approach to (1) determine the degree to which EPDS cutoffs that are commonly used to report depression prevalence may deviate from prevalence based on a validated semi‐structured diagnostic interview, the SCID; and (2) to use a prevalence matching approach (Kelly, Dunstan, Lloyd, & Fone, 2008; Thombs et al., 2018) to determine whether any cutoff threshold on the EPDS matches SCID major depression prevalence closely and with sufficiently low heterogeneity to be used for estimating major depression prevalence in individual studies.

2. METHODS

We used a subset of data accrued for an IPDMA on EPDS diagnostic accuracy. The IPDMA was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42015024785), and a protocol was published (Thombs et al., 2015). The present study was not included in the protocol for the main EPDS IPDMA, but a separate protocol was published on the Open Science Framework prior to initiating the study (https://osf.io/7gy6p/).

2.1. Identification of eligible studies

In the main IPDMA, datasets from articles in any language were eligible for inclusion if (1) they included EPDS scores for women who were pregnant or in the postpartum period, defined as within 12 months of birth; (2) they included diagnostic classifications for current Major Depressive Episode or Major Depressive Disorder based on DSM (American Psychiatric Association, 1987, 1994, 2000, 2013) or International Classification of Diseases (World Health Organization, 1992) criteria, using a validated semi‐structured or fully structured interview; (3) the EPDS and diagnostic interview were administered within 2 weeks of each other, since diagnostic criteria for major depression are for symptoms in the last 2 weeks; (4) participants were ≥18 years and not recruited from youth or school‐based settings; and (5) participants were not recruited from psychiatric settings or because they were identified as having symptoms of depression, since screening is done to identify unrecognized cases. Datasets where not all participants were eligible were included if primary data allowed selection of eligible participants.

For the present study, in our main analyses, we included only primary studies that based major depression diagnoses on the SCID (First & Gibbon, 2004). The SCID is a semi‐structured diagnostic interview intended to be conducted by an experienced diagnostician; it requires clinical judgment and allows rephrasing questions and probes to follow up responses. The reason for including only studies that administered the SCID is because semi‐structured interviews replicate diagnostic standards more closely than other types of interviews, and the SCID is by far the most commonly used semi‐structured diagnostic interview for depression research (Levis et al., 2018, 2019a; Wu et al., 2020). In recent analyses using three large IPDMA databases (Levis et al., 2018, 2019a; Wu et al., 2020), compared to semi‐structured interviews, fully structured interviews, which are designed for administration by lay interviewers, identified more patients with low‐level depressive symptoms as depressed but fewer patients with high‐level symptoms. These results are consistent with the idea that semi‐structured interviews most closely replicate clinical interviews done by trained professionals. Fully structured interviews are less resource‐intensive options because they are completely scripted and allow for minimal or no judgment, since they are designed to be administered by research staff without diagnostic skills. They may, however, misclassify major depression in substantial numbers of patients. In the EPDS IPDMA database, the SCID was the most common semi‐structured interview. In a sensitivity analysis, we included two additional studies from the database that used semi‐structured interviews other than the SCID.

2.2. Data sources, search strategy, and study selection

A medical librarian searched Medline, Medline In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations and PsycINFO via OvidSP, and the Web of Science Core Collection via ISI Web of Knowledge from inception to June 10, 2016, using a peer‐reviewed search strategy (McGowan et al., 2016) (see Supplementary material, Methods S2). We also reviewed reference lists of relevant reviews and queried contributing authors to attempt to identify non‐published studies. Search results were uploaded into RefWorks (RefWorks‐COS). After de‐duplication, remaining citations were uploaded into DistillerSR (Evidence Partners) for processing review results.

Two investigators independently reviewed titles and abstracts for eligibility. If either deemed a study potentially eligible, full‐text review was done by two investigators, independently, with disagreements resolved by consensus, consulting a third investigator when necessary. Translators were consulted for languages other than those for which team members were fluent.

2.3. Data contribution and synthesis

Authors of eligible datasets were invited to contribute de‐identified primary data, including EPDS scores and major depression classification status. We emailed corresponding authors of eligible primary studies at least three times, as necessary, with at least 2 weeks between each email. If we did not receive a response, we emailed co‐authors and attempted to contact corresponding authors by phone.

Prior to integrating individual datasets into our synthesized dataset, we compared published participant characteristics and diagnostic accuracy results with results from raw datasets and resolved any discrepancies in consultation with the original investigators. The number of participants and the number of cases from a primary study in the IPDMA dataset differed from the originally published primary study reports for some studies. There are several reasons for this. First, in some primary studies, some, but not all, participants met the inclusion criteria for the main IPDMA. For instance, we required administration of the EPDS index test and reference standard to be within a 2‐week period and only included participants aged 18 or older recruited from non‐psychiatric settings. We only included data from participants in primary studies who met these criteria. Second, the reference standard diagnostic category for the main IPDMA differed from that used in some published reports of primary studies. Some primary studies reported accuracy results for depression diagnoses broader than major depression, such as “major + minor depression” or “any depressive disorder”. We restricted our depression variable to major depression classification. Third, as part of our data verification process, we compared published participant characteristics and diagnostic accuracy results with results obtained using the raw datasets. When primary data that we received from investigators and original publications were discrepant, we identified and corrected errors in consultation with the original primary study investigators.

When primary datasets included statistical weights to reflect sampling procedures, we used the weights provided. For studies where sampling procedures merited weighting, but the original study did not weight, we constructed weights using inverse selection probabilities. This occurred, for instance, when all participants with positive screens and a random subset of participants with negative screens were administered a diagnostic interview.

2.4. Statistical analyses

First, for each primary study, we estimated three values: (1) the percentage of participants classified as having major depression based on the SCID, (2) the percentage of participants who scored above the cutoff threshold for all possible EPDS cutoffs (≥0 through ≥ 30), and (3) the difference of these percentages. Then, across all studies, we pooled prevalence for each EPDS cutoff, prevalence for the SCID, and the difference in prevalence from each study.

Second, we identified the EPDS cutoff with the smallest pooled difference. Then, for each included study, in addition to already estimated difference in prevalence based on the cutoff versus SCID major depression, we also estimated the ratio of prevalence based on the cutoff to that of the SCID. We plotted study‐level differences by sample size and determined the mean and median absolute difference and the range of differences across all studies. To illustrate the range of difference values that would be expected if a new study were to compare prevalence based on the prevalence match scoring approach to prevalence based on SCID major depression, we estimated a 95% prediction interval for the difference.

All meta‐analyses incorporated sampling weights and were conducted in R (R version R 3.6.0 and R Studio version 1.1.453) using the lme4 package (Bates, Mächler, Bolker, & Walker, 2015). To estimate pooled prevalence values, generalized linear mixed‐effects models with a logit link function were fit using the glmer function. To estimate pooled difference values, linear mixed‐effects models were fit using the lmer function. To account for correlation between subjects within the same primary study, random intercepts were fit for each primary study. To quantify heterogeneity, for each analysis, we calculated τ 2, which is the estimate of between‐study variance, and I 2, which quantifies the proportion of total variability due to the between‐study heterogeneity.

We conducted two sets of post‐hoc analyses. First, we repeated the prevalence match analysis excluding studies with SCID‐based prevalence >20% and >15%, separately, in order to assess results without studies that reported very high prevalence and ensure that results were consistent when only studies with more typical prevalence were included. For each subset of studies, we (1) identified the EPDS cutoff with the smallest pooled difference and (2) estimated the 95% prediction interval for the difference. Second, we investigated whether differences in prevalence for the EPDS prevalence match scoring approach and SCID were associated with study and participant characteristics in order to attempt to explain the heterogeneity we found. To do this, we fit additional linear mixed‐effects models for pooled prevalence difference, including age, pregnant versus postpartum status, country human development index (“very high”, “high”, or “low‐medium”) (United Nation's Development Programme, 2020), and study sample size as fixed‐effect covariates.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Search results and inclusion of primary study datasets

For the main IPDMA, of the 3417 unique titles and abstracts identified from the search, 3097 were excluded after title and abstract review and 212 after full‐text review. The 108 remaining articles comprised data from 73 unique samples, of which 49 (67%) contributed individual participant data. One additional study, which was subsequently published, was provided by the authors of an included study, for a total of 50 datasets. For our main analyses, we excluded 21 studies that classified major depression using a diagnostic interview other than the SCID, such that the sample for those analyses included 7315 participants (1017 major depression cases; prevalence 14%) from 29 primary studies (see Figure 1). Table 1 shows characteristics of each included study.

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of the study selection process. CI, confidence interval; EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; SCID, Structured Clinical Interview for DSM

TABLE 1.

Difference between EPDS ≥14 prevalence and SCID prevalence for each included study

| Author, Year | Country | N Total | N (%) EPDS ≥ 14 | N (%) Major depression | % Difference EPDS ≥ 14—Major Depression | Ratio: EPDS ≥ 14/Major depression |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aceti et al. (2012) a | Italy | 44 | 16 (14.1%) | 22 (19.4%) | −5.3% | 0.7 |

| Barnes, Senior, and MacPherson (2009) | UK | 347 | 33 (9.5%) | 25 (7.2%) | 2.3% | 1.3 |

| Bavle et al. (2016) | India | 318 | 13 (4.1%) | 6 (1.9%) | 2.2% | 2.2 |

| Beck and Gable (2001) | USA | 150 | 15 (10.0%) | 18 (12.0%) | −2.0% | 0.8 |

| Bunevicius, Kusminskas, Pop, Pedersen, and Bunevicius (2009) | Lithuania | 230 | 11 (4.8%) | 12 (5.2%) | −0.4% | 0.9 |

| Chaudron et al. (2010) | USA | 187 | 39 (20.9%) | 70 (37.4%) | −16.6% | 0.6 |

| de Figueiredo et al. (2015) a | Brazil | 241 | 73 (20.8%) | 94 (29.4%) | −8.6% | 0.7 |

| Garcia‐Esteve, Ascaso, Ojuel, and Navarro (2003) a | Spain | 334 | 66 (6.9%) | 36 (3.8%) | 3.1% | 1.8 |

| Giardinelli et al. (2012) | Italy | 588 | 39 (6.6%) | 28 (4.8%) | 1.9% | 1.4 |

| Helle et al. (2015) | Germany | 224 | 29 (12.9%) | 12 (5.4%) | 7.6% | 2.4 |

| Hickey, Boyce, Ellwood, and Morris‐Yates (1997) a | Australia | 72 | 16 (4.7%) | 31 (9.1%) | −4.4% | 0.5 |

| Howard et al. (2018) a | UK | 527 | 114 (8.4%) | 130 (9.6%) | −1.2% | 0.9 |

| Leonardou et al. (2009) | Greece | 81 | 10 (12.3%) | 4 (4.9%) | 7.4% | 2.5 |

| Navarro et al. (2007) a | Spain | 401 | 108 (8.1%) | 84 (8.1%) | 0.0% | 1 |

| Phillips, Charles, Sharpe, and Matthey (2009) | Australia | 158 | 46 (29.1%) | 42 (26.6%) | 2.5% | 1.1 |

| Prenoveau et al. (2013) a | UK | 219 | 33 (9.7%) | 20 (6.0%) | 3.7% | 1.6 |

| Quispel, Schneider, Hoogendijk, Bonsel, and Lambregtse‐van den Berg (2015) | Netherlands | 36 | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.0% | Not applicable |

| Radoš, Tadinac, and Herman (2013) | Croatia | 272 | 19 (7.0%) | 10 (3.7%) | 3.3% | 1.9 |

| Robertson‐Blackmore et al. (2013) | USA | 358 | 62 (17.3%) | 29 (8.1%) | 9.2% | 2.1 |

| Rochat, Tomlinson, Newell, and Stein (2013) | South Africa | 104 | 37 (35.6%) | 50 (48.1%) | −12.5% | 0.7 |

| Siu, Leung, Ip, Hung, and O'hara (2012) | China | 805 | 86 (10.7%) | 126 (15.7%) | −5.0% | 0.7 |

| Stewart, Umar, Tomenson, and Creed (2013) a | Malawi | 186 | 25 (5.3%) | 34 (10.1%) | −4.8% | 0.5 |

| Tandon, Cluxton‐Keller, Leis, Le, and Perry (2012) | USA | 89 | 20 (22.5%) | 25 (28.1%) | −5.6% | 0.8 |

| Tendais, Costa, Conde, and Figueiredo (2014) a | Portugal | 141 | 13 (4.9%) | 18 (7.6%) | −2.7% | 0.6 |

| Töreki et al. (2013) | Hungary | 219 | 3 (1.4%) | 7 (3.2%) | −1.8% | 0.4 |

| Töreki et al. (2014) | Hungary | 265 | 10 (3.8%) | 8 (3.0%) | 0.8% | 1.2 |

| Tran et al. (2011) | Vietnam | 359 | 8 (2.2%) | 52 (14.5%) | −12.3% | 0.2 |

| Turner et al. (2009) | Italy | 54 | 4 (7.4%) | 5 (9.3%) | −1.9% | 0.8 |

| Vega‐Dienstmaier, Mazzotti Suárez, and Campos Sánchez (2002) | Peru | 306 | 75 (24.5%) | 19 (6.2%) | 18.3% | 3.9 |

| Studies from IPDMA that used other semi‐structured interviews and were included in sensitivity analysis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pawlby, Sharp, Hay, and O'Keane (2008) b | UK | 190 | 17 (8.9%) | 34 (17.9%) | −8.9% | 0.5 |

| Tissot, Favez, Frascarolo‐Moutinot, and Despland (2015) c | Switzerland | 65 | 5 (7.7%) | 4 (6.2%) | 1.5% | 1.2 |

Abbreviations: EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; IPDMA, individual participant data meta‐analysis; SCID, Structured Clinical Interview for DSM.

Sampling weights were applied. Counts are based on actual numbers whereas percentages are weighted.

Diagnostic interview: The Clinical Interview Schedule.

Diagnostic interview: The Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies.

In sensitivity analyses, we included data from two additional studies that used a semi‐structured diagnostic interview other than the SCID (N participants: 255; N major depression cases: 38; prevalence 15%). This resulted in inclusion of data from 31 primary studies (N participants: 7570; N major depression cases: 1055; prevalence 14%). See Table 1.

3.2. Depression prevalence based on EPDS cutoffs and the SCID

Pooled prevalence estimates ranged from 27.8% (95% CI: 22.0%–34.5%, τ 2: 0.71, I 2: 96.5%) for EPDS cutoff ≥ 9 to 9.0% (95% CI: 6.8%–11.9%, τ 2: 0.66, I 2: 96.3%) for cutoff ≥ 14 (Figure 2, Table S2). The most commonly used cutoffs for estimating prevalence of ≥10 and ≥ 13 provided pooled prevalence estimates of 22.2% (95% CI: 17.5%–27.8%, τ 2: 0.64, I 2: 95.5%) and 11.5% (95% CI: 8.7%–15.0%, τ 2: 0.66, I 2: 96.4%), respectively. The pooled SCID major depression prevalence was 9.0% (95% CI: 6.5%–12.3%, τ 2: 0.87, I 2: 96.4%). See Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Prevalence estimates and 95% CI based on each EPDS cutoff threshold from ≥ 9 to ≥ 14. CI, confidence interval; EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; SCID, Structured Clinical Interview for DSM

3.3. Prevalence matching

The pooled difference between the proportion of participants with EPDS ≥14 and SCID major depression prevalence across all studies was the smallest of all cutoff thresholds (−0.7%, 95% CI: −3.2% to 1.9%, τ 2: 0.004, I 2: 95.8%; Table S2). Across the 29 individual studies, however, differences ranged from −16.6% to 18.3% using that cutoff score (mean absolute difference: 5.1%; median absolute difference: 3.3%, Figure 3). Specifically, 20 (69%) studies using that cutoff were ≤0.75 times or ≥ 1.25 times the actual SCID‐based prevalence (Table 1). The 95% prediction interval for the difference between EPDS ≥14 and SCID‐based prevalence was −13.7% to 12.3%. Results were similar in the sensitivity analyses that included the two additional non‐SCID datasets (pooled EPDS ≥ 14 prevalence: 9.0%, 95% CI: 6.9%–11.7%, τ 2: 0.61, I 2: 96.5%; pooled major depression prevalence: 9.1%, 95% CI: 6.7%–12.3%, τ 2: 0.84, I 2: 96.6%; pooled difference: −0.9%, 95% CI: −3.4% to 1.6%; τ 2: 0.004, I 2: 96.0%; mean absolute difference: 5.1%; median absolute difference: 3.3%).

FIGURE 3.

Dispersion of the differences between the prevalence estimates based on EPDS ≥ 14 and SCID major depression for each study, considering the study sample size. EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; SCID, Structured Clinical Interview for DSM

In post‐hoc analyses, for the 24 studies with SCID‐based prevalence ≤20%, prevalence based on the SCID was 6.8% (95% CI: 5.3%–8.5%, τ 2: 0.31, I 2: 95.1%). EPDS ≥14 was the closest match (pooled difference [95% CI]: 0.7% [−1.8% to 3.2%], τ 2: 0.003, I 2: 94.8%), and the 95% prediction interval for the difference was −10.8% to 12.2%. For the 22 studies with SCID‐based prevalence ≤15%, prevalence based on the SCID was 6.2% (95% CI: 5.0%–7.6%, τ 2: 0.21, I 2: 94.2%). EPDS ≥15 was the closest match (pooled difference [95% CI]: −0.2% [−2.3% to 1.9%], τ 2: 0.002, I 2: 93.6%), and the 95% prediction interval for the difference was −9.2% to 8.8%. Using data from all 29 included studies, no study or participant characteristics were significantly associated with differences in prevalence based on EPDS ≥14 versus SCID, with the exception of age, for which a one‐year increase in age was associated with 0.2% (95% CI: 0.1%–0.3%) decrease in “EPDS ≥ 14 minus SCID” prevalence.

4. DISCUSSION

The developers of the EPDS intended it to be a questionnaire that could detect symptoms of depression that are commonly experienced by women in the postpartum period but that would not be picked up by other scales (Cox et al., 1987). It was not intended to classify cases or estimate prevalence. Most studies that report the prevalence of depression in pregnancy or postpartum, however, are based on the proportion of women in the study who score above a cutoff threshold on a depression screening questionnaire, most commonly the EPDS. The EPDS cutoffs used to estimate prevalence in recently published studies ranged from ≥9 to ≥14, with ≥10 and ≥ 13 being the cutoffs most commonly used for this purpose. We found that, compared to SCID major depression prevalence, commonly used EPDS cutoffs overestimated prevalence. A cutoff of ≥10 on the EPDS generated a prevalence of 22%, and a cutoff of ≥13 generated prevalence of 11%, compared to 9% with the SCID.

Overall, the pooled prevalence based on an EPDS cutoff of ≥14 (9%) was closest to the pooled SCID major depression prevalence (9%). However, differences between prevalence based on the EPDS and SCID varied substantially across individual studies. The difference between EPDS‐ and SCID‐based prevalence ranged from −17% to 18%, and the estimated 95% prediction interval indicated that in the next study using both tools, the difference in prevalence could fall anywhere between −14% and 12%. Thus, although overall prevalence with EPDS ≥14 is similar to that of the SCID, if used to estimate prevalence in individual studies, it could considerably under or overestimate the true major depression prevalence in any given study. Differences between EPDS and SCID‐based estimates were not associated with sample size. We found that age was statistically significantly associated with the difference between EPDS ≥14 and SCID‐based prevalence, but a 1‐year difference in age was associated with only a 0.2% difference in prevalence; given the general similarity in ages of pregnant and postpartum women, this would not explain the large differences we found.

The results from this study are similar to findings from Levis et al. (2020) that compared prevalence based on the PHQ‐9 screening tool and the SCID. The most commonly used cutoff of PHQ‐9 ≥10 overestimated the SCID prevalence by approximately 12%. Prevalence matching for PHQ‐9 revealed that PHQ‐9 ≥14 provided a pooled prevalence estimate closest to SCID major depression prevalence. However, as in the present study, the difference in prevalence between PHQ‐9 ≥14 and the SCID varied considerably across individual studies.

It is common to report the proportion scoring at or above the cutoff threshold as prevalence of “depressive symptoms” or “clinically significant depressive symptoms” rather than suggesting that prevalence of depression has been reported. However, this does not resolve the problem. Diagnostic thresholds are designed to identify individuals with a condition or with a level of impairment that warrants attention, and there is no evidence that impairment from symptoms of depression becomes meaningful at or above these thresholds, which have been set for the purpose of screening, not for delineating impairment. Furthermore, while people with symptom scores above these thresholds have greater symptom impairment on average than those below the threshold, that would be the case for whatever threshold is set. Reporting percentages of women who score above different cutoffs may be useful for comparing levels of symptoms across samples, for instance. It should not, however, be characterized as “prevalence” or as a percentage of women who have “symptoms of depression” versus not having those symptoms.

This study was designed to evaluate how accurately the EPDS is for estimating prevalence; it did not evaluate the accuracy of the tool to identify individuals who may have depression and screen out those less likely to have depression. A strength of the present study is that it included data from 29 studies that fulfilled rigorous inclusion criteria and administered both the EPDS and the SCID. This made a direct comparison of prevalence estimates possible. A limitation is that the heterogeneity of the pooled prevalence based on both the SCID and EPDS was very high, despite well‐defined inclusion criteria and the narrow population of interest (women in pregnancy or postpartum). Furthermore, we compared prevalence based on two methods, but the estimation of the true depression prevalence in pregnancy and postpartum was out of the scope of this IPDMA, and the set of included primary studies may not be representative. Additionally, there were few studies with very large sample sizes (e.g., >400), and our examination of the association between sample size and differences between estimation methods may have been limited by this. Another was that the search included studies only through June 2016.

In conclusion, our findings show that EPDS is not able to accurately and reliably estimate depression prevalence in individual studies. Estimates based on the most commonly used cutoffs of ≥10 and ≥ 13 overestimate prevalence. Estimates based on a cutoff ≥14 were similar overall to SCID‐based estimates. However, there was variation between studies, and this cutoff could substantially under or overestimate prevalence in individual studies compared to prevalence based on a diagnostic interview. Thus, the proportion above a cutoff threshold on the EPDS should not be reported as prevalence of depression. Instead, validated diagnostic interviews, which are designed to classify case status based on standard diagnostic criteria, should be used for this purpose. Clinicians should be aware that studies that estimate prevalence based on standard cutoffs of ≥10 and ≥13 will tend to generate estimates that are higher than what they might expect to see in their practice.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

All authors have completed the ICJME uniform disclosure form and declare: no support from any organization for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years with the following exceptions: Dr. Tonelli declares that he has received a grant from Merck Canada, outside the submitted work. Dr. Vigod declares that she receives royalties from UpToDate, outside the submitted work. Dr. Beck declares that she receives royalties for her Postpartum Depression Screening Scale published by Western Psychological Services. Dr. Boyce declares that he receives grants and personal fees from Servier, grants from Lundbeck, and personal fees from AstraZeneca, all outside the submitted work. Dr. Howard declares that she has received personal fees from NICE Scientific Advice, outside the submitted work. No funder had any role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Anita Lyubenova, Dipika Neupane, Brooke Levis, Yin Wu, Jill T. Boruff, John P. A. Ioannidis, Pim Cuijpers, Simon Gilbody, Lorie A. Kloda, Scott B. Patten, Ian Shrier, Roy C. Ziegelstein, Liane Comeau, Nicholas D. Mitchell, Marcello Tonelli, Simone N. Vigod, Andrea Benedetti, and Brett D. Thombs were responsible for the study conception and design. Jill T. Boruff and Lorie A. Kloda designed and conducted database searches to identify eligible studies. Franca Aceti, Jacqueline Barnes, Amar D. Bavle, Cheryl T. Beck, Carola Bindt, Philip M. Boyce, Andrea Bunevicius, Linda H. Chaudron, Nicolas Favez, Barbara Figueiredo, Lluïsa Garcia‐Esteve, Lisa Giardinelli, Nadine Helle, Louise M. Howard, Jane Kohlhoff, Laima Kusminskas, Zoltán Kozinszky, Lorenzo Lelli, Angeliki A. Leonardou, Valentina Meuti, Sandra N. Radoš, Purificación N. García, Susan J. Pawlby, Chantal Quispel, Emma Robertson‐Blackmore, Tamsen J. Rochat, Deborah J. Sharp, Bonnie W. M. Siu, Alan Stein, Robert C. Stewart, Meri Tadinac, S. Darius Tandon, Iva Tendais, Annamária Töreki, Anna Torres‐Giménez, Thach D. Tran, Kylee Trevillion, Katherine Turner, Johann M. Vega‐Dienstmaier were responsible for collection of primary data included in this study. Anita Lyubenova, Dipika Neupane, Brooke Levis, Ying Sun, Chen He, Ankur Krishnan, Parash M. Bhandari, Zelalem Negeri, Mahrukh Imran, Danielle B. Rice, Marleine Azar, Matthew J. Chiovitti, Nazanin Saadat, Kira E. Riehm, and Brett D. Thombs contributed to the title and abstract and full‐text review processes and data extraction for the meta‐analysis. Anita Lyubenova, Dipika Neupane, Brooke Levis, Yin Wu, Andrea Benedetti, and Brett D. Thombs contributed to the data analysis and interpretation. Anita Lyubenova, Dipika Neupane, Brooke Levis, Yin Wu, Andrea Benedetti, and Brett D. Thombs contributed to drafting the manuscript. All authors provided a critical review and approved the final manuscript. Andrea Benedetti and Brett D. Thombs are guarantors.

Supporting information

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR, KRS‐140994). Ms. Lyubenova was supported by the Mitacs Globalink Research Internship Program. Ms. Neupane was supported by G.R. Caverhill Fellowship from the Faculty of Medicine, McGill University. Drs. Levis and Wu were supported by Fonds de recherche du Québec‐Santé (FRQS) Postdoctoral Training Fellowships. Mr. Bhandari was supported by a studentship from the Research Institute of the McGill University Health Centre. Ms. Rice was supported by a Vanier Canada Graduate Scholarship. Ms. Azar was supported by a FRQS Masters Training Award. The primary study by Barnes et al. was supported by a grant from the Health Foundation (1665/608). The primary study by Beck et al. was supported by the Patrick and Catherine Weldon Donaghue Medical Research Foundation and the University of Connecticut Research Foundation. The primary study by Helle et al. was supported by the Werner Otto Foundation, the Kroschke Foundation, and the Feindt Foundation. Prof. Robertas Bunevicius, MD, PhD (1958‐2016) was Principal Investigator of the primary study by Bunevicius et al., but passed away and was unable to participate in this project. The primary study by Chaudron et al. was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (grant K23 MH64476). The primary study by Tissot et al. was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant 32003B 125493). The primary study by Tendais et al. was supported under the project POCI/SAU‐ESP/56397/2004 by the Operational Program Science and Innovation 2010 (POCI 2010) of the Community Support Board III and by the European Community Fund FEDER. The primary study by Garcia‐Esteve et al. was supported by grant 7/98 from the Ministerio de Trabajo y Asuntos Sociales, Women's Institute, Spain. The primary study by Howard et al. was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under its Programme Grants for Applied Research Programme (Grant Reference Numbers RP‐PG‐1210‐12002 and RP‐DG‐1108‐10012) and by the South London Clinical Research Network. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. The primary study by Phillips et al. was supported by a scholarship from the National Health and Medical and Research Council (NHMRC). The primary study by Nakić Radoš et al. was supported by the Croatian Ministry of Science, Education, and Sports (134‐0000000‐2421). The primary study by Navarro et al. was supported by grant 13/00 from the Ministry of Work and Social Affairs, Institute of Women, Spain. The primary study by Pawlby et al. was supported by a Medical Research Council UK Project Grant (number G89292999N). The primary study by Quispel et al. was supported by Stichting Achmea Gezondheid (grant number z‐282). Dr. Robertson‐Blackmore was supported by a Young Investigator Award from the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation and NIMH grant K23MH080290. The primary study by Rochat et al. was supported by grants from the University of Oxford (HQ5035), the Tuixen Foundation (9940), the Wellcome Trust (082384/Z/07/Z and 071571), and the American Psychological Association. Dr. Rochat receives salary support from a Wellcome Trust Intermediate Fellowship (211374/Z/18/Z). The primary study by Prenoveau et al. was supported by The Wellcome Trust (grant number 071571). The primary study by Stewart et al. was supported by Professor Francis Creed's Journal of Psychosomatic Research Editorship fund (BA00457) administered through University of Manchester. The primary study by Tandon et al. was funded by the Thomas Wilson Sanitarium. The primary study by Tran et al. was supported by the Myer Foundation who funded the study under its Beyond Australia scheme. Dr. Tran was supported by an early career fellowship from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council. The primary study by Vega‐Dienstmaier et al. was supported by Tejada Family Foundation, Inc, and Peruvian‐American Endowment, Inc. Drs. Benedetti and Thombs were supported by FRQS researcher salary awards.

Andrea Benedett and Brett D. Thombs are co‐senior authors.

Contributor Information

Andrea Benedetti, Email: andrea.benedetti@mcgill.ca.

Brett D. Thombs, Email: brett.thombs@mcgill.ca.

REFERENCES

- Aceti, F. , Aveni, F. , Baglioni, V. , Carluccio, G. M. , Colosimo, D. , Giacchetti, N. , … Biondi, M. (2012). Perinatal and postpartum depression: From attachment to personality. A pilot study. Journal of Psychopathology, 18, 328–334. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . (1987). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM‐III (3rd ed., revised). Washington, DC:American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM‐IV (4th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM‐IV (4th ed., text revised). Washington, DC:American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, J. , Senior, R. , & MacPherson, K. (2009). The utility of volunteer home‐visiting support to prevent maternal depression in the first year of life. Child: Care, Health and Development, 35(6), 807–816. 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2009.01007.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates, D. , Mächler, M. , Bolker, B. , & Walker, S. (2015). Fitting linear mixed‐effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software, 67(1), 1–48. 10.18637/jss.v067.i01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bavle, A. D. , Chandahalli, A. S. , Phatak, A. S. , Rangaiah, N. , Kuthandahalli, S. M. , & Nagendra, P. N. (2016). Antenatal depression in a tertiary care hospital. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine, 38(1), 31–35. 10.4103/0253-7176.175101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck, C. T. , & Gable, R. K. (2001). Comparative analysis of the performance of the Postpartum Depression Screening Scale with two other depression instruments. Nursing Research, 50(4), 242–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunevicius, A. , Kusminskas, L. , Pop, V. J. , Pedersen, C. A. , & Bunevicius, R. (2009). Screening for antenatal depression with the Edinburgh Depression Scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynecology, 30(4), 238–243. 10.3109/01674820903230708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudron, L. H. , Szilagyi, P. G. , Tang, W. , Anson, E. , Talbot, N. L. , Wadkins, H. I. M. , … Wisner, K. L. (2010). Accuracy of depression screening tools for identifying postpartum depression among urban mothers. Pediatrics, 125(3), e609–e617. 10.1542/peds.2008-3261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox, J. L. , Holden, J. M. , & Sagovsky, R. (1987). Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10‐item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. British Journal of Psychiatry, 150, 782–786. 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Figueiredo, F. P. , Parada, A. P. , Cardoso, V. C. , Batista, R. F. L. , Silva, A. A. M. d. , Barbieri, M. A. , … Del‐Ben, C. M. (2015). Postpartum depression screening by telephone: A good alternative for public health and research. Archives of Women's Mental Health, 18(3), 547–553. 10.1007/s00737-014-0480-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First, M. B. , & Gibbon, M. (2004). The structured clinical interview for DSM‐IV Axis I disorders (SCID‐I) and the structured clinical interview for DSM‐IV Axis II disorders (SCID‐II). In Hilsenroth M. J., & Segal D. L. (Eds.), Comprehensive handbook of psychological assessment: Vol. 2. Personality assessment (pp. 134–143). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia‐Esteve, L. , Ascaso, C. , Ojuel, J. , & Navarro, P. (2003). Validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) in Spanish mothers. Journal of Affective Disorders, 75(1), 71–76. 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00020-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giardinelli, L. , Innocenti, A. , Benni, L. , Stefanini, M. C. , Lino, G. , Lunardi, C. , … Faravelli, C. (2012). Depression and anxiety in perinatal period: Prevalence and risk factors in an Italian sample. Archives of Women's Mental Health, 15(1), 21–30. 10.1007/s00737-011-0249-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helle, N. , Barkmann, C. , Bartz‐Seel, J. , Diehl, T. , Ehrhardt, S. , Hendel, A. , … Bindt, C. (2015). Very low birth‐weight as a risk factor for postpartum depression four to six weeks postbirth in mothers and fathers: Cross‐sectional results from a controlled multicentre cohort study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 180, 154–161 10.1016/j.jad.2015.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt, C. , Gilbody, S. , Brealey, S. , Paulden, M. , Palmer, S. , Mann, R. , … Richards, D. (2009). Methods to identify postnatal depression in primary care: An integrated evidence synthesis and value of information analysis. Health Technology Assessment, 13(36), 1–145, 147–230. 10.3310/hta13360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickey, A. R. , Boyce, P. M. , Ellwood, D. , & Morris‐Yates, A. D. (1997). Early discharge and risk for postnatal depression. The Medical Journal of Australia, 167(5), 244–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard, L. M. , Molyneaux, E. , Dennis, C.‐L. , Rochat, T. J. , Stein, A. , & Milgrom, J. (2014). Non‐psychotic mental disorders in the perinatal period. The Lancet, 384(9956), 1775–1788. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61276-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard, L. M. , Ryan, E. G. , Trevillion, K. , Anderson, F. , Bick, D. , Bye, A. , … Pickles, A. (2018). Accuracy of the Whooley questions and the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale in identifying depression and other mental disorders in early pregnancy. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 212(1), 50–56. 10.1192/bjp.2017.9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, M. J. , Dunstan, F. D. , Lloyd, K. , & Fone, D. L. (2008). Evaluating cutpoints for the MHI‐5 and MCS using the GHQ‐12: A comparison of five different methods. BMC Psychiatry, 8, 10. 10.1186/1471-244X-8-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonardou, A. A. , Zervas, Y. M. , Papageorgiou, C. C. , Marks, M. N. , Tsartsara, E. C. , Antsaklis, A. , … Soldatos, C. R. (2009). Validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale and prevalence of postnatal depression at two months postpartum in a sample of Greek mothers. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 27(1), 28–39. 10.1080/02646830802004909 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Levis, B. , Benedetti, A. , Ioannidis, J. P. A. , Sun, Y. , Negeri, Z. , He, C. , … Thombs, B. D. (2020). Patient Health Questionnaire‐9 scores do not accurately estimate depression prevalence: Individual participant data meta‐analysis. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 122, 115–128.e1. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levis, B. , Benedetti, A. , Riehm, K. E. , Saadat, N. , Levis, A. W. , Azar, M. , … Thombs, B. D. (2018). Probability of major depression diagnostic classification using semi‐structured versus fully structured diagnostic interviews. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 212(6), 377–385. 10.1192/bjp.2018.54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levis, B. , McMillan, D. , Sun, Y. , He, C. , Rice, D. B. , Krishnan, A. , … Thombs, B. D. (2019a). Comparison of major depression diagnostic classification probability using the SCID, CIDI, and MINI diagnostic interviews among women in pregnancy or postpartum: An individual participant data meta‐analysis. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 28(4), e1803. 10.1002/mpr.1803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levis, B. , Yan, X. W. , He, C. , Sun, Y. , Benedetti, A. , & Thombs, B. D. (2019b). Comparison of depression prevalence estimates in meta‐analyses based on screening tools and rating scales versus diagnostic interviews: A meta‐research review. BMC Medicine, 17(1), 65. 10.1186/s12916-019-1297-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGowan, J. , Sampson, M. , Salzwedel, D. M. , Cogo, E. , Foerster, V. , & Lefebvre, C. (2016). Press peer review of electronic search strategies: 2015 guideline statement. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 75, 40–46. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro, P. , Ascaso, C. , Garcia‐Esteve, L. , Aguado, J. , Torres, A. , & Martín‐Santos, R. (2007). Postnatal psychiatric morbidity: A validation study of the GHQ‐12 and the EPDS as screening tools. General Hospital Psychiatry, 29(1), 1–7. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2006.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawlby, S. , Sharp, D. , Hay, D. , & O'Keane, V. (2008). Postnatal depression and child outcome at 11 years: The importance of accurate diagnosis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 107(1–3), 241–245. 10.1016/j.jad.2007.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, J. , Charles, M. , Sharpe, L. , & Matthey, S. (2009). Validation of the subscales of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale in a sample of women with unsettled infants. Journal of Affective Disorders, 118(1–3), 101–112. 10.1016/j.jad.2009.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prenoveau, J. , Craske, M. , Counsell, N. , West, V. , Davies, B. , Cooper, P. , … Stein, A. (2013). Postpartum GAD is a risk factor for postpartum MDD: The course and longitudinal relationships of postpartum GAD and MDD. Depression and Anxiety, 30(6), 506–514. 10.1002/da.22040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quispel, C. , Schneider, T. A. J. , Hoogendijk, W. J. G. , Bonsel, G. J. , & Lambregtse‐van den Berg, M. P. (2015). Successful five‐item triage for the broad spectrum of mental disorders in pregnancy—A validation study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 15, 51. 10.1186/s12884-015-0480-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radoš, S. N. , Tadinac, M. , & Herman, R. (2013). Validation study of the Croatian version of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS). Suvremena Psihologija/Contemporary Psychology, 16, 203–218. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson‐Blackmore, E. , Putnam, F. W. , Rubinow, D. R. , Matthieu, M. , Hunn, J. E. , Putnam, K. T. , … O'Connor, T. G. (2013). Antecedent trauma exposure and risk of depression in the perinatal period. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 74(10), e942–8. 10.4088/JCP.13m08364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochat, T. J. , Tomlinson, M. , Newell, M.‐L. , & Stein, A. (2013). Detection of antenatal depression in rural HIV‐affected populations with short and ultrashort versions of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS). Archives of Women's Mental Health, 16(5), 401–410. 10.1007/s00737-013-0353-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siu, B. W. M. , Leung, S. S. L. , Ip, P. , Hung, S. F. , & O'hara, M. W. (2012). Antenatal risk factors for postnatal depression: A prospective study of Chinese women at maternal and child health centres. BMC Psychiatry, 12, 22. 10.1186/1471-244X-12-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, R. C. , Umar, E. , Tomenson, B. , & Creed, F. (2013). Validation of screening tools for antenatal depression in Malawi—A comparison of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale and Self Reporting Questionnaire. Journal of Affective Disorders, 150(3), 1041–1047. 10.1016/j.jad.2013.05.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tandon, S. D. , Cluxton‐Keller, F. , Leis, J. , Le, H.‐N. , & Perry, D. F. (2012). A comparison of three screening tools to identify perinatal depression among low‐income African American women. Journal of Affective Disorders, 136(1–2), 155–162. 10.1016/j.jad.2011.07.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tendais, I. , Costa, R. , Conde, A. , & Figueiredo, B. (2014). Screening for depression and anxiety disorders from pregnancy to postpartum with the EPDS and STAI. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 17, E7. 10.1017/sjp.2014.7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thombs, B. D. , Benedetti, A. , Kloda, L. A. , Levis, B. , Riehm, K. E. , Azar, M. , … Vigod, S. (2015). Diagnostic accuracy of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) for detecting major depression in pregnant and postnatal women: Protocol for a systematic review and individual patient data meta‐analyses. BMJ Open, 5(10), e009742. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thombs, B. D. , Kwakkenbos, L. , Levis, A. W. , & Benedetti, A. (2018). Addressing overestimation of the prevalence of depression based on self‐report screening questionnaires. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal = Journal De L'Association Medicale Canadienne, 190(2), E44–E49. 10.1503/cmaj.170691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tissot, H. , Favez, N. , Frascarolo‐Moutinot, F. , & Despland, J.‐N. (2015). Assessing postpartum depression: Evidences for the need of multiple methods. Revue Européenne de Psychologie Appliquée/European Review of Applied Psychology, 65(2), 61–66. 10.1016/j.erap.2015.02.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Töreki, A. , Andó, B. , Dudas, R. B. , Dweik, D. , Janka, Z. , Kozinszky, Z. , & Keresztúri, A. (2014). Validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale as a screening tool for postpartum depression in a clinical sample in Hungary. Midwifery, 30(8), 911–918. 10.1016/j.midw.2014.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Töreki, A. , Andó, B. , Keresztúri, A. , Sikovanyecz, J. , Dudas, R. B. , Janka, Z. , … Pál, A. (2013). The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale: Translation and antepartum validation for a Hungarian sample. Midwifery, 29(4), 308–315. 10.1016/j.midw.2012.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran, T. , Tran, T. , La, B. , Lee, D. , Rosenthal, D. , & Fisher, J. R. (2011). Screening for perinatal common mental disorders in women in the north of Vietnam: A comparison of three psychometric instruments. Journal of Affective Disorders, 133(1–2), 281–293. 10.1016/j.jad.2011.03.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner, K. , Piazzini, A. , Franza, A. , Marconi, A. M. , Canger, R. , & Canevini, M. P. (2009). Epilepsy and postpartum depression. Epilepsia, 50(Suppl. 1), 24–27. 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01965.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Programme . (2020). Human Development Report 2019 . Retrieved from http://hdr.undp.org/en/2019-report

- Vega‐Dienstmaier, J. M. , Mazzotti Suárez, G. , & Campos Sánchez, M. (2002). Validación de una versión en español de la Escala de Depresión Postnatal de Edimburgo [Validation of a Spanish version of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale]. Actas Espanolas de Psiquiatria, 30(2), 106–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen, H. U. (1994). Reliability and validity studies of the WHO‐Composite International diagnostic interview (CIDI): A critical review. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 28(1), 57–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . (1992). The ICD‐10 classifications of mental and behavioural disorder. Clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y. , Levis, B. , Sun, Y. , Krishnan, A. , He, C. , Riehm, K. E. , … Thombs, B. D. (2020). Probability of major depression diagnostic classification based on the SCID, CIDI and MINI diagnostic interviews controlling for Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale‐Depression subscale scores: An individual participant data meta‐analysis of 73 primary studies. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 129, 109892. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2019.109892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material