Abstract

Patients with end stage kidney disease receiving in-center hemodialysis (ICHD) have had high rates of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Following infection, patients receiving ICHD frequently develop circulating antibodies to SARS-CoV-2, even with asymptomatic infection. Here, we investigated the durability and functionality of the immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients receiving ICHD. Three hundred and fifty-six such patients were longitudinally screened for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies and underwent routine PCR-testing for symptomatic and asymptomatic infection. Patients were regularly screened for nucleocapsid protein (anti-NP) and receptor binding domain (anti-RBD) antibodies, and those who became seronegative at six months were screened for SARS-CoV-2 specific T-cell responses. One hundred and twenty-nine (36.2%) patients had detectable antibody to anti-NP at time zero, of whom 127 also had detectable anti-RBD. Significantly, at six months, 71/111 (64.0%) and 99/116 (85.3%) remained anti-NP and anti-RBD seropositive, respectively. For patients who retained antibody, both anti-NP and anti-RBD levels were reduced significantly after six months. Eleven patients who were anti-NP seropositive at time zero, had no detectable antibody at six months; of whom eight were found to have SARS-CoV-2 antigen specific T cell responses. Independent of antibody status at six months, patients with baseline positive SARS-CoV-2 serology were significantly less likely to have PCR confirmed infection over the following six months. Thus, patients receiving ICHD mount durable immune responses six months post SARS-CoV-2 infection, with fewer than 3% of patients showing no evidence of humoral or cellular immunity.

Keywords: COVID-19, hemodialysis, SARS-CoV-2, serology

Graphical abstract

The efficacy results from several severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) vaccine trials provided welcome news at the end of 2020, as the rollout of effective vaccination programs set to mark the beginning of the end of the pandemic.1, 2, 3 The Moderna (mRNA-1273), Pfizer/BioNTech (BNT162b2 mRNA), and Oxford/AstraZeneca (ChAdOx1 nCoV-19) vaccines have all been shown to induce robust humoral and cellular immune responses against the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2, which importantly protect individuals from the risk of subsequent infection.4 , 5 However, given the logistical issues associated with supply, distribution, and administration of vaccines globally, adjunct prevention and control measures are going to need to be continued in the months to come.

Patients with end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) have been identified as having a poor prognosis after SARS-CoV-2 infection.6, 7, 8 In addition, it is recognized that patients receiving in-center hemodialysis (ICHD) are at a higher risk of acquiring infection owing to the inability to shield effectively.8 Using serological methods, we have previously shown that patients with ESKD readily seroconvert after confirmed SAR-CoV-2 infection; we have also shown that asymptomatic seroconversion is common in the high exposure setting of ICHD units.7 What is not currently known in this population is the durability of detectable immune responses and whether the presence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies protects an individual with ESKD from reinfection.

In this study, we report the longitudinal serological status of a large cohort of patients receiving ICHD. The aim of our study was to compare the longevity of the antibodies to the different SARS-CoV-2 antigenic targets, namely, the nucleocapsid and receptor-binding domain of the spike protein. We investigate cellular immune responses in patients in whom antibody responses have waned, and finally we evaluate whether immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 infection protect patients receiving dialysis from subsequent reinfection.

Methods

Patient selection

Three hundred fifty-six patients receiving ICHD within 2 units affiliated with Imperial College Renal and Transplant Centre as previously reported were included.7 Patients were followed up from 24 February 2020 until 1 January 2021. All patient samples (n = 356) at time 0 were tested for nucleocapsid protein (anti-NP) and RBD (anti-RBD) antibodies. At 6 months, all available samples (n = 301) were retested for anti-NP (Supplementary Figure S1). In addition, samples were tested for anti-RBD if any of the following criteria were met: patients were anti-NP+ at 6 months or patients had an equivocal anti-NP result (i.e., a cutoff index [S/C] of 0.25–1.39) or were anti-NP− (i.e., an S/C of ≤0.24) at 6 months but were either anti-NP+ and/or anti-RBD+ at baseline.

Patient outcomes, including all new SARS-CoV-2 infections confirmed by viral detection, were recorded up until 1 January, which incorporate data from the second wave of infections in the United Kingdom. A diagramatic overview of the outcome of patients by serological and symptomatic status is shown in Figure 1 . The study was approved by the Health Research Authority Research Ethics Committee (Reference: 20/WA/0123 - The Impact of COVID-19 on Patients with Renal disease and Immunosuppressed Patients).

Figure 1.

Patient cohort flow diagram by nucleocapsid antibody (anti-NP) and receptor-binding domain antibody (anti-RBD) status after the first wave of infection. ICHD, in-center hemodialysis; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

SARS-CoV-2 antibody detection

Baseline serum from all patients were tested for both anti-NP and anti-RBD antibodies. The presence of anti-NP was assessed using the commercially available Abbott Architect SARS-CoV-2 IgG II step chemiluminescent immunoassay according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For this study, samples were interpreted as positive or negative according to the manufacturer’s instructions with a cutoff index value of 1.4.9 Anti-RBD was detected using an in-house double-antigen binding enzyme-linked immunoassay (Imperial SARS-CoV-2 Hybrid DABA, Imperial College London, London, UK), which detects total RBD antibodies.10 The in-house assay cutoff was calculated from receiver operating characteristic curve analysis, and serum reactivity was normalized by using the signal-to-cutoff ratio. For this study, a sample was considered antibody positive if the signal-to-cutoff ratio was >1.2. An RBD assay was used in addition to an anti-NP assay, as anti-RBD has been shown to correlate with anti-neutralizing antibodies.11

Detection of SARS-CoV-2 T-cell responses

T-cell responses were investigated in cases where serological evidence of infection, both anti-NP and anti-RBD, had waned at 6 months. SARS-CoV-2–specific T-cell responses were detected using T-SPOT Discovery SARS-CoV-2 (Oxford Immunotec) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated from whole blood samples using T-Cell Select (Oxford Immunotec) where indicated. A total of 250,000 peripheral blood mononuclear cells were plated in individual wells of a T-SPOT Discovery SARS-CoV-2 plate. The assay measures immune responses to 5 different overlapping SARS-CoV-2 structural peptide pools: spike protein, nucleocapsid protein, membrane protein, and a mix of structural proteins, as well as positive and negative controls. Cells were incubated, and interferon-γ–secreting T cells were detected. The sum of T-SPOT immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 structural peptides was calculated. Counts >12 spots per 250,000 peripheral blood mononuclear cells were reported as positive.12

Diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection

Infection with SARS-CoV-2 was confirmed through reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay of nasopharyngeal swab specimens, either after routine screening or after acute presentation. Reverse transcriptase PCR was performed as per Public Health England guidelines by using certification marked assays with primers directed against multiple targets of SARS-CoV-2 genes.13 Between March and June 2020, patients underwent reverse transcriptase PCR testing of nasopharyngeal swabs when they presented for dialysis with symptoms. In June, all patients in our center were screened regardless of symptoms, as part of a single surveillance exercise to ascertain prevalent infection. From the start of the second wave in November 2020, all patients receiving ICHD underwent weekly routine reverse transcriptase PCR testing of nasopharyngeal swabs.

Statistical analysis

Statistical and graphical analyses were performed with MedCalc v19.2.1 (STATA Corporation). The 2-sided level of significance was set at P < 0.05. The chi-square test was used for proportional assessments. Nonparametric data were compared using the Mann-Whitney test. The Wilcoxon test was used to compare antibody levels of paired samples. Using the log-rank test, Kaplan-Meier analyses were used to estimate and compare the risk of infection (or reinfection) by serological status. We recorded any positive PCR test at >60 days after a positive serological test at time 0 to prevent capture of persistent viral detection of the primary infection.14 As we were not routinely PCR swabbing all asymptomatic cases at the time of first serological sampling, we also used only the PCR results taken >60 days post–serological screening in the antibody-negative group. Subsequent PCR-positive free survival was censored for death in the absence of PCR confirmation and transplantation.

Results

At time 0, 129 of 356 patients (36.2%) had detectable anti-NP and 134 of 356 (37.6%) had detectable anti-RBD. Discordance between anti-NP and anti-RBD detection was seen in only 9 of 356 patients (0.3%). The clinical characteristics of patients by anti-NP status has been described previously and are summarized in Table 1 .7

Table 1.

Patient characteristics by anti-NP antibody status at time 0

| Variable | Anti-NP+ (n = 129) | Anti-NP− (n = 227) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.98 | ||

| Female | 47 (36.4) | 83 (36.6) | |

| Male | 82 (63.6) | 144 (63.4) | |

| Age, yr | 65 (55–73) | 68 (57–77) | 0.05 |

| Ethnicity | 0.36 | ||

| Black | 18 (14.0) | 28 (12.3) | |

| White | 29 (22.5) | 61 (26.9) | |

| Indoasian | 60 (46.5) | 94 (41.4) | |

| Other | 22 (17.1) | 44 (19.4) | |

| Cause of ESKD | 0.90 | ||

| APKD | 6 (4.7) | 13 (5.7) | |

| Diabetic nephropathy | 48 (37.2) | 86 (37.9) | |

| Glomerulonephritis | 19 (14.7) | 42 (18.5) | |

| Other | 12 (9.3) | 37 (16.3) | |

| Unknown | 38 (29.5) | 42 (18.5) | |

| Urological | 6 (4.7) | 7 (3.1) | |

| Time at ESKD, yr | 1.7 (0.9–3.2) | 2.2 (0.9–4.0) | 0.18 |

| Immunosuppressed – yes | 14 (10.9) | 41 (18.0) | 0.07 |

| Symptomatic – yes | 85 (65.9) | 36 (15.9) | <0.0001 |

Anti-NP, nucleocapsid protein; APKD, autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease; ESKD, end-stage kidney disease.

Data are expressed as median (interquartile range) or n (%). Statistically significant P values are shown in bold.

Serostatus and antibody levels at 6 months

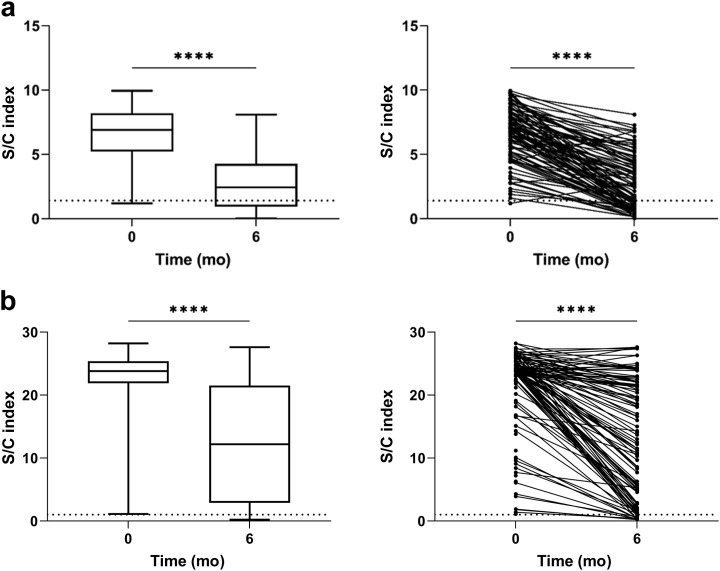

Three hundred one patients had a sample available at 6 months after the initial sampling. Of the 190 patients who were anti-NP− at time 0, 6 (3.2%) had detectable anti-NP by month 6, of whom 3 had PCR-proven disease in the intervening period. In patients who were anti-NP+ at time 0; the S/C was significantly higher in symptomatic patients than in asymptomatic patients, with a median value of 7.3 (interquartile range [IQR] 6.1–8.5) and 6.2 (IQR 3.2–7.1), respectively (P = 0.0006). One hundred eleven of 129 patients who were anti-NP+ at time 0 had a sample available at 6 months. Forty of 111 (36.0%) were subsequently found to be anti-NP− at 6 months. In patients who were anti-NP+ at both time 0 and 6 months, the median S/C was significantly lower at 6 months than at time 0 at 2.3 (IQR 0.9–4.3) and 6.9 (IQR 5.2–8.2) respectively (P < 0.0001) (Figure 2 ).

Figure 2.

Comparison of nucleocapsid protein (anti-NP) and receptor-binding domain (anti-RBD) antibody levels at time 0 and 6 months. (a) Anti-NP antibody. Plots show summary and individual patient data. Forty of 111 patients with detectable anti-NP at time 0 (36.0%) became anti-NP− at 6 months. For those retaining antibodies, the anti-NP index (S/C) was significantly higher at time 0 than at 6 months post-testing, with a median S/C of 6.9 (interquartile range [IQR] 5.2–8.2) and 2.3 (IQR 0.9–4.3), respectively (P < 0.0001). (b) Anti-RBD antibody. Plots show summary and individual patient data. Ninety-seven of 111 patients with anti-RBD at time 0 (87.4%) retained their antibodies at 6 months. For those retaining antibodies, the anti-RBD index (S/CO) was significantly higher at time 0 than at 6 months post-testing, with a median S/CO of 23.9 (IQR 23.4–26.1) and 23.4 (IQR 8.9–24.1), respectively (∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001).

Of the 129 patients who were anti-NP+ at time 0, 127 patients (98.4%) were anti-RBD+. Of the 227 patients who were anti-NP− at time 0, 7 (3.1%) were anti-RBD+. In anti-RBD+ patients, the antibody index at time 0 was also significantly higher in symptomatic patients that in asymptomatic patients, with a median signal-to-cutoff ratio of 23.9 (IQR 23.4–26.1) and 23.4 (IQR 11.0–24.1), respectively (P = 0.0011). Of the 116 patients with anti-RBD at baseline with samples available for testing at 6 months, 99 patients (85.3%) remained anti-RBD+. Anti-RBD durability was significantly longer than anti-NP durability (P = 0.0002); and of the 40 patients who became anti-NP−, 28 (70.0%) remained anti-RBD+ at 6 months. Similarly to anti-NP, for those patients retaining antibody, the anti-RBD index value was significantly higher at time 0 than at 6 months, with a median signal-to-cutoff ratio of 23.8 (IQR 23.3–25.4) and 14.7 (IQR 5.7–21.7), respectively (P < 0.0001).

T-cell responses at 6 months

Twelve patients who were anti-NP+ at time 0 were seronegative for both anti-NP and anti-RBD at 6 months. One of these patients had received a transplant in the intervening period, and so T-cell responses were investigated in the 11 remaining patients. Of these 11 patients, 8 had positive enzyme-linked immune absorbent spot (ELISpot) readouts, as shown in Table 2 . Three patients were found to have nonreactive antigen–specific T-cell responses; all were older than 70 years; 1 had a history of bladder cancer, but none were iatrogenically immunosuppressed. All 3 patients had previous asymptomatic infection; 2 of the 3 had both detectable anti-NP and anti-RBD at diagnosis, whereas 1 of the 3 had anti-NP but was anti-RBD−. T-cell responses were not available in patients who were anti-NP− but anti-RBD+ at time 0.

Table 2.

Characteristics of 11 patients who were seronegative by anti-NP and anti-RBD antibodies at 6 months

| Sex | Age range, yr | Ethnicity | Cause of ESKD | Baseline SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis | First serology |

ELISpot readout | Subsequent PCR+ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-NP | Ab index | Anti-RBD | Ab index | |||||||

| M | 40–49 | Indoasian | GN | Serology | + | 5.62 | + | 3.9 | + | No |

| M | 40–49 | Black | HIV | Serology | + | 1.61 | + | 1.8 | + | No |

| M | 60–69 | White | APKD | Serology | + | 6.16 | + | 16.5 | + | No |

| M | 60–69 | Indoasian | APKD | Serology | + | 2.76 | + | 1.9 | + | No |

| F | 60–69 | White | Unknown | Serology | + | 2.81 | + | 9.1 | + | No |

| M | 60–69 | Indoasian | DM | Serology | + | 5.73 | + | 22.4 | + | No |

| F | 70–79 | Other | APKD | Serology | + | 5.18 | + | 10.1 | − | No |

| M | 60–69 | Indoasian | Unknown | Serology | + | 7.62 | + | 6.1 | + | No |

| F | 70–79 | Indoasian | DM | PCR | + | 3.32 | + | 4.3 | + | No |

| M | 70–79 | White | Urological | Serology | + | 9.21 | + | 23.8 | − | No |

| M | 70–79 | Indoasian | Unknown | Serology | + | 1.88 | − | − | No | |

Ab, antibody; APKD, autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease; ESKD, end-stage kidney disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; F, female; GN, glomerulonephritis; M, male; anti-NP, nucleocapsid protein; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; anti-RBD, receptor-binding domain; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

Combining the results of the above immunological assessment, of the original 129 patients who were anti-NP+, 126 (97.7%) had evidence of persistence of either serological or cellular immune responses against SARS-CoV-2 at 6 months.

Clinical outcomes associated with seroconversion

Finally, we investigated the clinical relevance of these immune responses in terms of the risk of a subsequent diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Within the first 60 days of the time 0 serological test, 4 anti-NP− and 1 anti-NP+ patients died and 3 anti-NP− and 3 anti-NP+ patients had a positive PCR test. From >60 days after initial serological testing, anti-NP+ patients were at a significantly lower risk of being diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 compared with anti-NP− patients (log-rank, P = 0.0005), as shown in Figure 3 . The 2 patients who were anti-NP+ at baseline who went on to have subsequent PCR-confirmed infection both had prior asymptomatic infection; one of the patients had subsequent asymptomatic infection diagnosed by surveillance swabbing, whereas the other patient had symptomatic infection and died 28 days postdiagnosis. Of the remaining 27 patients who had a positive PCR test at >60 days after the first serological test, 11 (40.7%) had follow-up for >28 days after PCR testing, of whom 2 (18.2%) had died.

Figure 3.

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) polymerase chain reaction (PCR)–positive free survival at 60 days after the first serological testby antibody status. (a) Nucleocapsid (anti-NP) antibody. From >60 days after initial serological testing, anti-NP+ patients were at a significantly lower risk of being diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 than anti-NP− patients (log-rank, P = 0.0005). (b) Receptor-binding domain (anti-RBD) antibody. From >60 days after initial serological testing, anti-RBD+ patients were also at a lower risk of being diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 by PCR testing compared with anti-RBD− patients (log-rank, P = 0.0051).

Anti-RBD+ patients were also at a lower risk of being diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 by PCR testing compared with anti-RBD− patients (log-rank, P = 0.0051), as shown in Figure 3. Of the 7 anti-RBD+ patients who were anti-NP− at time 0, 2 subsequently went on to have a PCR-positive test at >60 days; the first was diagnosed at day 74 after the serological test, and this may represent persistent viral carriage rather than reinfection. The second case was a male patient in his 70s who was diagnosed at day 112 after a symptomatic infection who has subsequently made a full recovery.

Discussion

We have shown that immune responses to natural SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients receiving ICHD are durable for up to 6 months, even in patients who had mild or asymptomatic infection. Furthermore, we have provided data that show that an immune response to SARS-CoV-2 infection may help provide protection against “infection” or reinfection in patients receiving dialysis in the medium term. Using serological status to determine previous exposure in populations receiving ICHD may therefore help identify patients at a higher risk of primary infection while awaiting vaccine administration.

A recent large longitudinal study of health care workers has shown that the presence of anti-spike or anti-NP antibodies was associated with a reduced risk of reinfection over a 6-month period.14 , 15 These data are consistent with the relative sparsity of reports of reinfection in the literature.16 , 17 However, given this study included health care workers, who are likely to be significantly younger and lack comorbidity, translating these findings to patients with ESKD in the absence of data would be injudicious. However, a separate report, which investigated the medium term humoral and cellular responses in patients with SARS-CoV-2 and a range of comorbidities, has also shown that robust immune responses may persist for at least 8 months postinfection.18 Although this may be more comparable data for patients receiving dialysis, a further study from this same research group showed there was a disparity in adaptive immune responses in older persons.19 This is of concern for the nephrology community, as patients receiving dialysis are also known to have impairment of both the innate and adaptive immune responses that correlate with premature aging.20

Our study, which is the first to investigate longevity of SARS-CoV-2 immune responses in patients receiving dialysis, is therefore of clinical importance. Like others, we have shown that antibody levels wane over time and the rate of decay correlates with infection severity.21 We found that symptomatic infection is associated with higher antibody “titers,” and it was reassuring to demonstrate that the distribution of S/C values in patients receiving dialysis postinfection is comparable with that in health care workers as reported in other studies using the same serological assay.22 Furthermore, consistent with data in health care workers, we have shown that an anti-RBD immune response is more durable than an anti-NP response.22 However, we acknowledge that the use of seroprevalence alone may underestimate ongoing immunity to SARS-CoV-2, with data showing that robust T-cell responses can be detected in patients who have had mild or asymptomatic disease, even in the absence of antibodies.23 In our cohort of patients receiving dialysis, we have shown that <3% of patients lacked evidence of either serological or T-cell responses at 6 months postinfection. Of upmost clinical relevance, we have also shown that a detectable serological response to SARS-CoV-2 infection appears to be protective against reinfection in patients receiving dialysis, even at 6 months postinfection. These data are encouraging given the high rates of infection seen during the early stages of pandemic, as, although patients receiving dialysis await vaccination, previous exposure to infection may offer some protection. In our cohort, serological analysis certainly enabled the identification of patients with prior infection, which may have otherwise been underestimated, given we were not routinely testing for PCR-positive infections in asymptomatic cases during the first wave.

It is worth noting that of the 2 patients with serological evidence of anti-NP who had subsequent viral detection by reverse transcriptase PCR at days 142 and 205 after the initial detection of seroconversion, one patient has HIV and the other patient previously had a kidney transplant (Supplementary Table S1). In addition, the 3 patients with no serological or cellular evidence of immunity at 6 months, all were older than 70 years. Therefore, although we have shown that patients receiving dialysis per se appear to mount an immunological response to SARS-CoV-2, there may be additional recognized clinical factors that may impair immunity and influence outcome in patients receiving dialysis, which requires further study.

The efficacy of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in patients with ESKD is currently not known as such patients were excluded from the preliminary SARS-CoV-2 vaccine trials. Patients receiving dialysis are recognized to have lower rates of seroprotection to vaccinations compared with healthy controls, which in part is due to the effect of uremic toxins on the immune response.24 This immune deficiency appears to be related to responses to new antigenic pathogens, which is of vital importance in the outcome to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination.25 Extrapolation from the knowledge that immunosenescence associated with aging is seen prematurely in patients receiving dialysis and that older people had significantly lower levels of anti-spike protein antibody and neutralizing antibody levels at 28 days after the BNT162b2 injection than did younger patients suggests the urgent need for some prospective data in this vulnerable population.5 , 26 Reasurringly, data are now emerging that neutralizing antibodies developed in response to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination are more durable than immunity from natural infection.27 This coupled with the data we present on sustained serological responses and protection from reinfection akin to those in health care workers provides hope for comparable vaccine responses in patients with ESKD.14 , 27 Furthermore, baseline serological status of patients from previous exposure may be of relevance in patients with ESKD given the high prevalence of infection in patients receiving ICHD, and it will be of interest to evaluate whether vaccine responses are less robust in infection-naïve patients.28

This study has several limitations, in part because of the time-sensitive nature of the results that have led us to take a pragmatic approach to sample processing. The study would have been strengthened by the addition of more laboratory data on viral loads over time. Certainly, there have been case reports of prolonged viral shedding, which may be more common in immunosuppressed patients.29 , 30 However, we used a 60-day cutoff for “new” PCR positivity, as used by others previously.14 It is also relevant to highlight that all patients did subsequently undergo routine asymptomatic PCR swabbing after this time point. A further limitation is that we do not have data available on viral genetic sequencing of infected patients, and it is possible that “reinfections” are due to new variants of SARS-CoV-2, which may evade immune responses to previous strains.31 However, if this was the case, we would have expected to see equal amounts of new “variant infection” across all patients. Our serological data may have been strengthened by screening all patients at 6 months for RBD antibodies, which have been shown to more closely correlate with neutralizing antibody titer.11 Finally, we performed T-cell ELISpot assays in only selected cases as time and resource limitations prevented further testing at this stage. However, the major strengths of our study are that, to our knowledge, this is the first report of longitudinal immunological responses in patients receiving dialysis, which in addition have been correlated with clinical outcome data in asymptomatic and symptomatic infections.

In conclusion, we have shown that patients receiving dialysis mount durable immune responses 6 months after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Fewer than 3% of infected patients had no detectable serological or T-cell responses at 6 months. We have also shown that the risk of subsequent PCR-positive confirmed infection was significantly lower in patients who have had detectable antibodies. Together, these data suggest that immune responses postinfection may be protective against reinfection. Given the high prevalence of primary SARS-CoV-2 infection during the first wave in ICHD units, this is important information for the nephrology community while vaccination programs roll out.

Disclosure

PK and MW have received support to use the T-SPOT Discovery SARS-CoV-2 by Oxford Immunotec. All the other authors declared no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre based at Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust (ICHNT) and Imperial College London. The authors would like to thank the West London Kidney Patientsʼ Association, all the patients and staff at ICHNT (the ICHNT Renal COVID Group and dialysis staff), and staff in the North West London Pathology laboratories. The authors are also grateful for the support from Hari and Rachna Murgai and Milan and Rishi Khosla. CLC was supported by an Auchi fellowship. MP was supported by an NIHR clinical lectureship. MW was supported by a donation from the Burnham family.

Footnotes

see commentary on page 1275

Figure S1. Schematic diagram of criteria to test samples by assay type at Time 0 (T0) and at Time 6 (T6) months.

Table S1. Characteristics of 5 seropositive patients who were subsequently found to be SARS-CoV-2 positive.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Polack F.P., Thomas S.J., Kitchin N. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2603–2615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Folegatti P.M., Ewer K.J., Aley P.K. Safety and immunogenicity of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine against SARS-CoV-2: a preliminary report of a phase 1/2, single-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2020;396:467–478. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31604-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baden L.R., El Sahly H.M., Essink B. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:403–416. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2035389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barrett J.R., Belij-Rammerstorfer S., Dold C. Phase 1/2 trial of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 with a booster dose induces multifunctional antibody responses. Nat Med. 2021;27:279–288. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-01179-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walsh E.E., Frenck R.W., Jr., Falsey A.R. Safety and immunogenicity of two RNA-based Covid-19 vaccine candidates. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2439–2450. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2027906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Valeri A.M., Robbins-Juarez S.Y., Stevens J.S. Presentation and outcomes of patients with ESKD and COVID-19. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;31:1409–1415. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2020040470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clarke C., Prendecki M., Dhutia A. High prevalence of asymptomatic COVID-19 infection in hemodialysis patients detected using serologic screening. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;31:1969–1975. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2020060827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corbett R.W., Blakey S., Nitsch D. Epidemiology of COVID-19 in an urban dialysis center. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;31:1815–1823. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2020040534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Public Health England Evaluation of the Abbott SARS-CoV-2 IgG for the detection of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/887221/PHE_Evaluation_of_Abbott_SARS_CoV_2_IgG.pdf Available at: Accessed December 15, 2020.

- 10.Rosadas C., Randell P., Khan M. Testing for responses to the wrong SARS-CoV-2 antigen? Lancet. 2020;396:e23. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31830-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Premkumar L., Segovia-Chumbez B., Jadi R. The receptor-binding domain of the viral spike protein is an immunodominant and highly specific target of antibodies in SARS-CoV-2 patients. Sci Immunol. 2020;5 doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abc8413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wyllie D, Mulchandani R, Jones HE, et al. SARS-CoV-2 responsive T cell numbers are associated with protection from COVID-19: a prospective cohort study in keyworkers [e-pub ahead of print]. medRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.11.02.20222778. Accessed December 15, 2020.

- 13.Public Health England. Guidance and standard operating procedure COVID-19 virus testing in NHS laboratories. Available at: https://www.rcpath.org?uploads?assets?90111431-8aca-4614-b06633d07e2a3dd9/Guidance-and-SOP-COVID-19-Testing-NHS-Laboratories.pdf. Accessed December 15, 2020.

- 14.Lumley S.F., O’Donnell D., Stoesser N.E. Antibody status and incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in health care workers. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:533–540. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hall V, Foulkes S, Charlett A, et al. Do antibody positive healthcare workers have lower SARS-CoV-2 infection rates than antibody negative healthcare workers? Large multi-centre prospective cohort study (the SIREN study), England: June to November 2020 [e-pub ahead of print]. medRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.01.13.21249642. Accessed December 15, 2020.

- 16.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control Reinfection with SARS-CoV-2: considerations for public health response. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/Re-infection-and-viral-shedding-threat-assessment-brief.pdf Available at: Accessed December 15, 2020.

- 17.Iwasaki A. What reinfections mean for COVID-19. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21:3–5. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30783-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dan J.M., Mateus J., Kato Y. Immunological memory to SARS-CoV-2 assessed for up to 8 months after infection. Science. 2021;371:eabf4063. doi: 10.1126/science.abf4063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rydyznski Moderbacher C., Ramirez S.I. Antigen-specific adaptive immunity to SARS-CoV-2 in acute COVID-19 and associations with age and disease severity. Cell. 2020;183:996–1012.e19. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.09.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Betjes M.G. Immune cell dysfunction and inflammation in end-stage renal disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2013;9:255–265. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2013.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ibarrondo F.J., Fulcher J.A., Goodman-Meza D. Rapid decay of anti–SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in persons with mild Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1085–1087. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2025179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lumley SF, Wei J, O’Donnell D, et al. The duration, dynamics and determinants of SARS-CoV-2 antibody responses in individual healthcare workers [e-pub ahead of print]. Clin Infect Dis. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciab004. Accessed January 16, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Sekine T., Perez-Potti A., Rivera-Ballesteros O. Robust T cell immunity in convalescent individuals with asymptomatic or mild COVID-19. Cell. 2020;183:158–168.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khan S.F., Bowman B.T. Vaccinating the patient with ESKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;14:1525–1527. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02210219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wall N.A., Dominguez-Medina C.C., Faustini S.E. Humoral immunity to memory antigens and pathogens is maintained in patients with chronic kidney disease. PLoS One. 2018;13 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0195730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meijers R.W., Litjens N.H., de Wit E.A. Uremia causes premature ageing of the T cell compartment in end-stage renal disease patients. Immun Ageing. 2012;9:19. doi: 10.1186/1742-4933-9-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Widge A.T., Rouphael N.G., Jackson L.A. Durability of responses after SARS-CoV-2 mRNA-1273 vaccination. N Engl J Med. 2020;384:80–82. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2032195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eiselt J., Kielberger L., Rajdl D. Previous vaccination and age are more important predictors of immune response to influenza vaccine than inflammation and iron status in dialysis patients. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2016;41:139–147. doi: 10.1159/000443416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lacson E., Jr., Weiner D., Majchrzak K. Prolonged live SARS-CoV-2 shedding in a maintenance dialysis patient. Kidney Med. 2021;3:309–311. doi: 10.1016/j.xkme.2020.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Avanzato V.A., Matson M.J., Seifert S.N. Case study: prolonged infectious SARS-CoV-2 shedding from an asymptomatic immunocompromised individual with cancer. Cell. 2020;183:1901–1912.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.10.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tea F, Stella AO, Aggarwal A, et al. SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies; longevity, breadth, and evasion by emerging viral variants [e-pub ahead of print]. medRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.19.20248567. Accessed January 16, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.