Dear editor,

The emergence of new SARS-CoV-2 variants, especially those of concerns, and their rapid dispersal emphasize the importance of active surveillance for SARS-CoV-2 variants worldwide.1 , 2

In the morning of 28th January 2021, after 55 days without SARS-CoV-2 community transmission in Vietnam, two PCR-confirmed cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection were reported. They came from two neighboring provinces, Hai Duong (HD) and Quang Ninh (QN), in the north of Vietnam.3 By the end of the day, 88 cases had been confirmed in these two provinces.

On the 28th of January 2021, a 28-year old man (patient 1) presented to a local district hospital in Ho Chi Minh city (HCMC) in southern Vietnam. He had just flown back from HD, where he had attended a relative's wedding party on 18th January. One of his relatives in HD tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 on the 28th January. As per the control measures in Vietnam,4 a nasopharyngeal throat swab (NTS) was obtained from patient 1 and tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 by RT-PCR5 on 29th January. Because the strain of the virus responsible for the outbreak in the north was unknown, we whole genome sequenced SARS-CoV-2 directly from the NTS of patient 1 using the ARTIC protocol,6 and obtained a complete genome on 31st January. Lineage analysis using Pangolin7 returned B.1.1.7, representing the first report of B.1.1.7 from a case of locally-acquired infection in Vietnam.3 Contact tracing identified a total of 162 close contacts of patient 1, but none were positive for SARS-CoV-2 by RT-PCR on 4th February.

The rapid expansion of the outbreak in the north, possibly caused by variant B.1.1.7, raised concerns about a nationwide outbreak (Supplementary Figure 1A). This prompted HCMC to conduct enhanced surveillance for SARS-CoV-2, primarily focusing on high-risk groups, including those working at Tan Son Nhat (TSN) international and domestic airport in HCMC. Subsequently, a baggage handler (patient 2) working at the airport and his brother (not working at the airport) were found positive for SARS-CoV-2 on 6th February. The next day, four co-workers (patients 3–6) of patient 2 also tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, while all contacts of patient 2′s brother were negative. At this time, the outbreak in the north had expanded to another 10 provinces/cities (Supplementary Figure 1B).

To dissect the epidemiological picture of the ongoing outbreak, we whole genome sequenced SARS-CoV-2 from the NTS of patients 2–6 using the ARTIC protocol. We obtained 3 complete genomes (1 from patient 2 on 8th February, and 2 from patients 3 and 4 on 10th February). All were assigned to sub-lineage A.23.1 (Pangolin).

After the detection of these six confirmed cases, contact tracing and testing detected 30 additional PCR confirmed cases, totaling 36 infected cases, including 9 members of TSN airport staff in total.3 The remaining cases were contacts of these 9 individuals (data not shown). Two additional SARS-CoV-2 whole genomes were successfully obtained from a brother of patient 6 and one of the airport staff; all belonged to A.23.1.

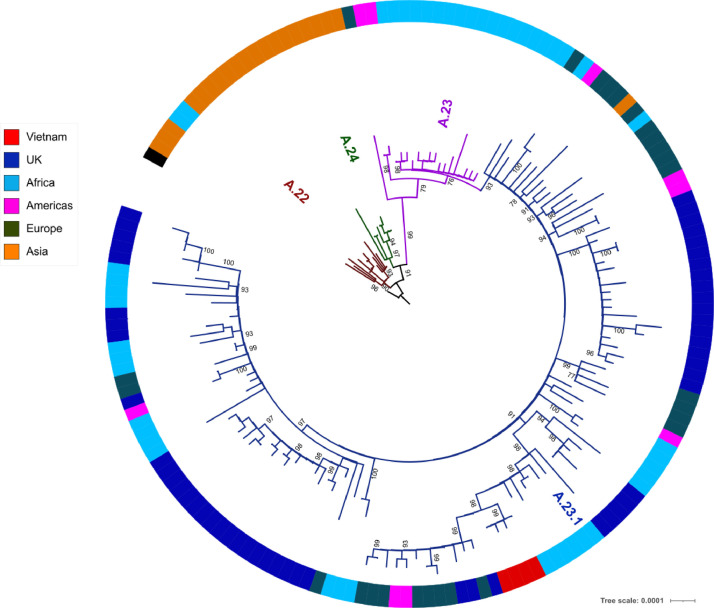

The 5 obtained whole-genome sequences of sub-lineage A.23.1 clustered tightly on a phylogenetic tree, and were closely related to A.23.1 strains collected from other countries (Fig. 1 ). Our findings suggest the TSN airport-associated cluster was caused by a single introduction of A.23.1 into the airport, although the origin of the infection remains unknown. As of the 17th March HCMC had gone 35 days without any new community transmissions.3

Fig. 1.

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree showing the relatedness between the Vietnamese SARS-CoV-2 sub-lineage A.23.1 (in red) obtained from the present study and representatives of global A.23.1 strains (B). Continents or countries from where A.23.1 has been documented are color-coded. Africa includes Rwanda, Uganda and Ghana. Europe covers non-UK countries, including Switzerland, Belgium and Denmark. Asia includes United Arab Emirates. Americas includes Canada and United States. Similar to A.23.1 strains identified elsewhere, all the Vietnamese strains carried the four defining single nucleotide polymorphisms (F157L, V367F, Q613H and P681R) in the spike protein.

Nine PCR-confirmed cases, including the 5 patients from whom a complete genome of A.23.1 was obtained, consented to have their clinical features reported.8 Two had mild symptoms and 7 were asymptomatic (Table 1 and Supplementary Figure 2).

Table 1.

Demographics of the study participants and contact details between RT-PCRconfirmed cases of the TSN airport associated cluster.

| Patient | Age | Gender | Geographic locations | Occupation | Lineage determinatio n | Symptomatic* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 28 | Male | Hai Duong | Not available | B.1.1.7 | Yes |

| 2 | 28 | Male | HCMC | Baggage handler | A.23.1 | No |

| 3 | 28 | Male | HCMC | Baggage handler, a co-worker of patient 2 | A.23.1 | Yes |

| 4 | 30 | Male | HCMC | Baggage handler, a co-worker of patient 2 | A.23.1 | No |

| 5 | 41 | Male | HCMC | Baggage handler, a co-worker of patient 2 | NA | No |

| 6 | 30 | Male | HCMC | A co-worker of patient 2 | NA | No |

| 7 | 23 | Male | HCMC | A brother of patient 6 | A.23.1 | No |

| 8 | 29 | Male | HCMC | Baggage handler, a co-worker of patient 2 | A.23.1 | No |

| 9 | 25 | Male | HCMC | Baggage handler, a co-worker of patient 2 | NA | No |

NA: not available, sequencing attempts were not successful. *Mild respiratory symptoms without requirement of oxygen supplement. HCMC: Ho Chi Minh City.

Since its first detection in Rwanda in October 2020, as of 19th March 2021, A.23.1 has been reported in 23countries worldwide.9 Notably, recently, A.23.1 has emerged and become a predominant sub-lineage circulating in Kampala, Uganda.2 Viruses of A.23.1 carry four defining mutations in spike protein (F157L, V367F, Q613H and P681R). Of these, Q613H is predicted to be biologically equivalent to the D614G, which emerged in early 2020, and has been shown to increase the transmisibility. As a consequnence, A.23.1 is now listed as one of the five variants (B.1.1.7, P1, B.1.351, and B.1.525) to be tracked globally.9

The turn-around time from RT-PCR diagnosis to SARS-CoV-2 lineage determination by whole-genome sequencing was between 1.5–3 days. This was achievable because of pre-existing sequencing infrastructure and expertise, and helped by the low prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in Vietnam. The sequencing findings were critical to informing rapid public health responses in HCMC. Indeed, the detection of the B.1.1.7 variant in the north led to enhanced surveillance in the south and the detection of the TSN airport cluster, which may otherwise have gone unnoticed.

Active surveillance for SARS-CoV-2 variants has been applied in developed countries since the beginning of the pandemic.10 It is now one of the top priorities of the WHO. However, success stories from a resource-constrained setting like Vietnam remain uncommon. Thus, enhancing the sequencing capacity in these recognized hotspots of pathogen emergence is of vital importance for both the global COVID-19 research agenda and the control of future emerging infections.

In summary, while our findings have expanded the geographic distributions of B.1.1.7 and A.23.1 variants, the data emphasize the importance of active surveillance for SARS-CoV-2 worldwide. The sequencing capacity in low- and middle-income countries must be strengthened to address the challenges of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and future emerging infections.

OUCRU COVID-19 research group

Hospital for Tropical Diseases, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam: Nguyen Van Vinh Chau, Nguyen Thanh Dung, Le Manh Hung, Huynh Thi Loan, Nguyen Thanh Truong, Nguyen Thanh Phong, Dinh Nguyen Huy Man, Nguyen Van Hao, Duong Bich Thuy, Nghiem My Ngoc, Nguyen Phu Huong Lan, Pham Thi Ngoc Thoa, Tran Nguyen Phuong Thao, Tran Thi Lan Phuong, Le Thi Tam Uyen, Tran Thi Thanh Tam, Bui Thi Ton That, Huynh Kim Nhung, Ngo Tan Tai, Tran Nguyen Hoang Tu, Vo Trong Vuong, Dinh Thi Bich Ty, Le Thi Dung, Thai Lam Uyen, Nguyen Thi My Tien, Ho Thi Thu Thao, Nguyen Ngoc Thao, Huynh Ngoc Thien Vuong, Huynh Trung Trieu Pham Ngoc Phuong Thao, Phan Minh Phuong

Oxford University Clinical Research Unit, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam: Dong Thi Hoai Tam, Evelyne Kestelyn, Donovan Joseph, Ronald Geskus, Guy Thwaites, Ho Quang Chanh, H. Rogier van Doorn, Ho Van Hien, Ho Thi Bich Hai, Huynh Le Anh Huy, Huynh Ngan Ha, Huynh Xuan Yen, Jennifer Van Nuil, Jeremy Day, Joseph Donovan, Katrina Lawson, Lam Anh Nguyet, Lam Minh Yen, Le Dinh Van Khoa, Le Nguyen Truc Nhu, Le Thanh Hoang Nhat, Le Van Tan, Sonia Lewycka Odette, Louise Thwaites, Maia Rabaa, Marc Choisy, Mary Chambers, Motiur Rahman, Ngo Thi Hoa, Nguyen Thanh Thuy Nhien, Nguyen Thi Han Ny, Nguyen Thi Kim Tuyen, Nguyen Thi Phuong Dung, Nguyen Thi Thu Hong, Nguyen Xuan Truong, Phan Nguyen Quoc Khanh, Phung Le Kim Yen, Phung Tran Huy Nhat, Sophie Yacoub, Thomas Kesteman, Nguyen Thuy Thuong, Tran Tan Thanh, Tran Tinh Hien, Vu Thi Ty Hang

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the Wellcome Trust of Great Britain (106680/B/14/Z and 204904/Z/16/Z).

We are indebted to Ms Le Kim Thanh, Lam Anh Nguyet and the Molecular Diagnostic Group of the Hospital for Tropical Diseases for their logistic/laboratory support. We thank the patients for their participations in this study,

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2021.03.017.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Toovey O.T.R., Harvey K.N., Bird P.W., Tang J.W.W. Introduction of Brazilian SARS-CoV-2 484 K.V2 related variants into the UK. J Infect. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2021.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bugembe D.L., Phan M.V.T., Ssewanyana I., Semanda P., Nansumba H., Dhaala B., Nabadda S., O'Toole Á.N., Rambaut A., Kaleebu P., Cotten M. A SARS-CoV-2 lineage A variant (A.23.1) with altered spike has emerged and is dominating the current Uganda epidemic. MedRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1038/s41564-021-00933-9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.02.08.21251393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.ncov.moh.gov.vn, an official website of the Vietnamese Ministry of Health providing update information about COVID-19. accessed on 6 March 2021.

- 4.Van Tan L. COVID-19 control in Vietnam. Nat Immunol. 2021;22(3):261. doi: 10.1038/s41590-021-00882-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corman V.M., Landt O., Kaiser M., Molenkamp R., Meijer A., Chu D.K., Bleicker T., Brunink S., Schneider J., Schmidt M.L., Mulders D.G., Haagmans B.L., van der Veer B., van den Brink S., Wijsman L., Goderski G., Romette J.L., Ellis J., Zambon M., Peiris M., Goossens H., Reusken C., Koopmans M.P., Drosten C. Detection of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) by real-time RT-PCR. Euro Surveill. 2020;25(3) doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.3.2000045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.https://artic.network/ncov-2019, Version 3.2020.

- 7.Rambaut A., Holmes E.C., O'Toole A., Hill V., McCrone J.T., Ruis C., du Plessis L., Pybus O.G. A dynamic nomenclature proposal for SARS-CoV-2 lineages to assist genomic epidemiology. Nat Microbiol. 2020;5(11):1403–1407. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0770-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chau N.V.V., Thanh Lam V., Thanh Dung N., Yen L.M., Minh N.N.Q., Hung L.M., Ngoc N.M., Dung N.T., Man D.N.H., Nguyet L.A., Nhat L.T.H., Nhu L.N.T., Ny N.T.H., Hong N.T.T., Kestelyn E., Dung N.T.P., Xuan T.C., Hien T.T., Thanh Phong N., Tu T.N.H., Geskus R.B., Thanh T.T., Thanh Truong N., Binh N.T., Thuong T.C., Thwaites G., Tan L.V. The natural history and transmission potential of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(10):2679–2687. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.https://cov-lineages.org/lineages/lineage_A.23.1.html. accessed on 6 March 2021.

- 10.COVID-19, 2020, Genomics UK Consortium, https://www.cogconsortium.uk/.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.