Abstract

Glioblastoma (GBM) is the highest-grade form of glioma, as well as one of the most aggressive types of cancer, exhibiting rapid cellular growth and highly invasive behavior. Despite significant advances in diagnosis and therapy in recent decades, the outcomes for high-grade gliomas (WHO grades III-IV) remain unfavorable, with a median overall survival time of 15–18 months. The concept of cancer stem cells (CSCs) has emerged and provided new insight into GBM resistance and management. CSCs can self-renew and initiate tumor growth and are also responsible for tumor cell heterogeneity and the induction of systemic immunosuppression. The idea that GBM resistance could be dependent on innate differences in the sensitivity of clonogenic glial stem cells (GSCs) to chemotherapeutic drugs/radiation prompted the scientific community to rethink the understanding of GBM growth and therapies directed at eliminating these cells or modulating their stemness. This review aims to describe major intrinsic and extrinsic mechanisms that mediate chemoradioresistant GSCs and therapies based on antineoplastic agents from natural sources, derivatives, and synthetics used alone or in synergistic combination with conventional treatment. We will also address ongoing clinical trials focused on these promising targets. Although the development of effective therapy for GBM remains a major challenge in molecular oncology, GSC knowledge can offer new directions for a promising future.

Keywords: Chemoradioresistance, Clinical trials, Glial stem cell, Initiating cells, Therapeutic strategies, Natural products

Introduction

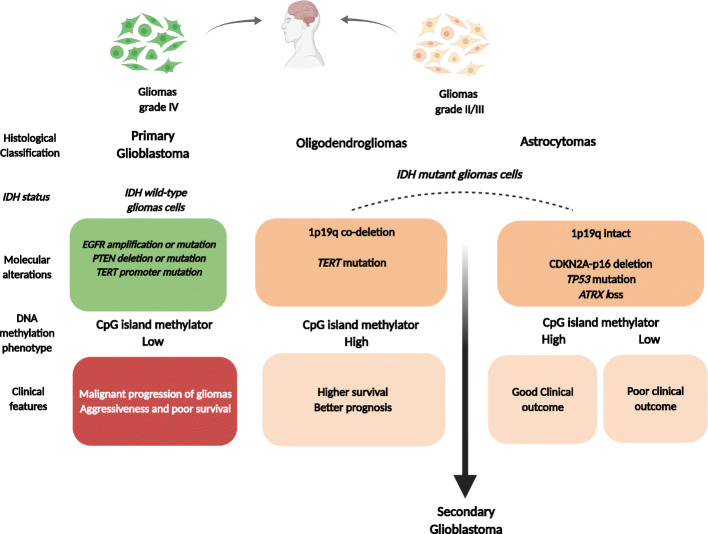

Gliomas are the most frequent primary brain tumors in adults, accounting for more than 80% of all malignant cerebral neoplasms [1]. Among these tumors, glioblastoma (GBM) is the most common primary intracranial tumor with a very poor prognosis (WHO grade IV), representing 57.3% of all gliomas [1, 2]. These tumors can be divided into IDH wild type, clinically defined as primary or de novo glioblastoma, which corresponds to approximately 90% of GBM cases and generally occurs in patients aged 62 or older, and IDH mutant, corresponding to secondary glioblastoma (approximately 10% of cases) that progressively develops from low-grade astrocytoma and frequently manifests in patients aged 40–50 years old (Fig. 1) [2, 3]. Currently, the most frequent molecular alterations associated with primary GBM are epidermal growth factor (EGFR) amplification or mutation, loss of heterozygosity (LOH) of chromosome 10q at the phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) locus, and TERT gene promoter mutation (Fig. 1). Moreover, combined deletion of the complete 1p and 19q after unbalanced translocation between chromosomes 1 and 19 resulting in the 1p19q codeletion, homozygous deletion of CDKN2A-p16, loss of tumor suppressor genes such as TP53 and ATRX, and IDH1/2 gene mutations are common molecular alterations found in secondary GBM (Fig. 1) [2, 4]. The amplification of the EGFR gene affects the development and progression of gliomas, conferring more aggressive properties, and can be used as a therapeutic target (Fig. 1) [3, 5]. Recent studies showed that the TERT promoter mutation essentially accounted for primary GBM and was associated with aggressiveness and poor survival (Fig. 1) [6, 7]. Although the presence of the 1p19q codeletion is associated with higher survival [8], CDKN2A-p16 deletion was associated with poor prognosis [8]. The association of TP53 mutation in GBM and ATRX mutation has not been consistent. So far, it is known that both can co-occur [9]. Importantly, IDH mutations are well-established markers of better prognosis [3, 8]. Genomic studies have also described five molecular subclasses (mesenchymal, classical (or proliferative), proneural, neural, and G-CIMP) [10]. Despite improvements in the knowledge and molecular characterization of glioblastomas, no significant difference in patient survival has been observed between primary and secondary glioblastomas, with both showing a mean survival of 12 to 15 months and a high frequency of tumor relapse [11].

Fig. 1.

Gliomas classification regarding the mutation status of isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH-1) gene. See text for details (created with Biorender.com)

The gold standard treatment for GBM patients is surgical resection combined with radiotherapy and adjuvant chemotherapy with the alkylating agent temozolomide (TMZ) [3, 12]. Although some molecular features have been proposed as predictive biomarkers of the treatment response to alkylating agents, such as the methylation status of the O6-methylguanine-DNA-methyltransferase (MGMT) promoter, the clinical utility of these markers is minimal [12, 13]. Some reasons proposed for this resistance may include the diffuse infiltrative nature to the surrounding brain, which hinders total resection; the high heterogeneity of GBM, involving distinct molecular pathways; and, more recently, the presence of stem cell-like tumorigenic features, including inducing angiogenesis, uncontrolled cellular proliferation, resisting cell death, and genome instability and mutation [3, 12].

Evidence of small populations of tumor cells that are similar to stem cells, known as cancer stem cells (CSCs) or tumor-initiating cells, has been known as a cause of tumor initiation and development since the nineteenth century and was first described in hematologic malignancies in 1994 [14].

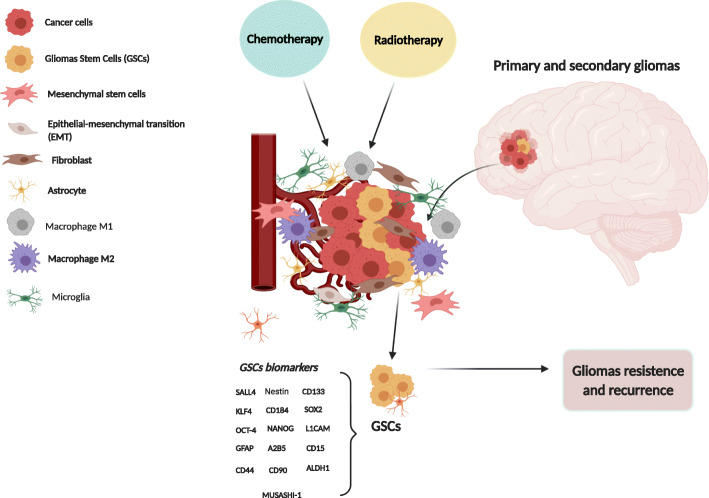

The first evidence of brain stem cells was shown by Ignatova et al. [15] and later supported by several other groups [16–18]. In glioblastoma, glioblastoma stem cells (GSCs) were first identified by Singh et al. as a population of cells capable of initiating tumor growth in vivo [19]. The first accepted GSC surface marker was CD133 [18]. This marker allows the subdivision of stem cells into two groups: CD133-positive cells (CD133+), or cancer stem cells, and CD133-negative cells (CD133−), or non-cancer stem cells [20]. CD133 expression also enables the characterization of cell self-renewal capacity, as there is a decrease in the expression of this surface marker during cell differentiation [21]. Another critical feature of CD133+ cells is the capacity to generate neurospheres in vitro and induce brain tumor formation in in vivo models [19, 22]. Other markers have also been associated with GSCs that together classify a signature of these cells. According to Dirks and coworkers, CD15 and CD133 are the most useful surface markers of GSCs reported to date and stand out compared to other markers [23]. The presence of dual CD133+/Ki-67+ cells and associated Nestin or HOX genes is an adverse prognostic factor for GBM progression [24–26]. Another marker highly expressed in GSCs is the CXCR4 chemokine receptor (CD184), which is associated with CD133+ cells and increased expression of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF-1-α) [27, 28]. The same importance should be assigned to the MUSASHI-1 protein, a regulator of translation and cellular fate [29]. Other markers, including the cell-surface glycoprotein CD44; the cell-surface gangliosides A2B5, CD90, and SOX2; and ALDH1, L1CAM, KLF4, SALL4, and GFAP, have also been also used for the identification of GSCs [29–35]. However, the specificity of the surface marker CD133 remains unclear, with groups reporting the identification of GSCs that are CD133 negative [36]. Therefore, it is also noteworthy that although CD133 and CD44 persist on genetically diverse clones [37], the presence of more primitive markers, such as OCT-4, SALL4, and NANOG, among others, needs to be better defined and may be key to developing novel and effective treatments for GBMs [38]. The main biomarkers are summarized in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Schematic overview of the cellular components of the microenvironment of glioblastoma (GBM). GSC: glial stem cell; Tumor microenvironment is a complex network composed of stromal cells (fibroblasts, microglia, astrocyte), mesenchymal cells, stem cells, and immune and inflammatory cells (macrophages). The main biomarkers of glial stem cells are indicated (created with Biorender.com)

Therefore, the promising GSC hypothesis offers new insight into cancer diagnosis and adds complexity in the management of brain tumors. The concept that GBM resistance could be dependent on innate differences in the sensitivity of clonogenic GSCs to chemotherapeutic drugs/radiation stimulated the scientific community to rethink the understanding of GBM growth and therapies designed to be directed at eliminating these cells or modulating their stemness [31, 39]. So far, the research strategies involve the development of drugs that target cancer stemness, directly or indirectly, in order to target multiple molecules, either alone or in combination.

This review aims to report intrinsic and extrinsic mechanisms that mediate chemoradioresistance in GSCs and therapies based on antitumor agents from natural sources, derivatives, and synthetics used alone or in synergistic combinations with conventional treatments. We will also summarize ongoing clinical trials focused on these promising targets. Although the development of effective therapies for GBM remains a major challenge in molecular oncology, GSC knowledge can offer new directions for a promising future.

Radioresistance

Role of repair mechanism in mediating radioresistance

Ionizing radiation (IR) from radiotherapy induces different types of DNA damage, especially DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs). Depending on the type of injury caused, DNA repair mechanisms and DNA damage checkpoints can be triggered, allowing cells to repair DNA damage and proliferate again [40]. The cellular response to DNA damage has been considered as one of the leading survival mechanisms of tumor cells after radiotherapy [40, 41].

Preclinical evidence demonstrates that many of these protection mechanisms are activated in CSC populations, possibly resulting in treatment resistance [42]. Bao et al. showed that CD133+ cell subpopulations are resistant to IR due to a more efficient repair system (phosphorylation of CHK1, CHK2, and H2AX form γ-H2AX foci) than the bulk of tumor cells and undergo apoptosis less frequently [31]. Moreover, an increase in CD133+ cells was also evidenced in clinical samples from recurrent tumors after high-dose radiotherapy treatment [43, 44]. Among other DNA repair-related genes, RAD51 overexpression is observed in GSCs, and BRCA1 and BRCA2 showed upregulation in glioblastoma cell lines, which led to reduced DNA damage after irradiation [45, 46]. The activation of ataxia-telangiectasia mutated (ATM) and ATM- and Rad3-related (ATR) also mediates radioresistance [47, 48]. In addition, other authors have reported that, in vitro, CD133+ primary cells are more radiosensitive than established glioma cell lines, with a reduced capacity to repair DNA double-strand breaks and an intact G2 checkpoint but no intra-S-phase checkpoint [21]. Therefore, the applicability of CD133+ GBM as a model of radioresistance is still unclear. These data highlight the heterogeneity of the in vitro radiosensitivity that exists among primary cell lines and reveal that radioresistance may be independent of the intrinsic GSC characteristics.

Role of microenvironment in radioresistance

One parameter that may influence radioresponse is the tumor microenvironment. Tumors are comprised of multiple components other than tumor cells (endothelial cells and multiple infiltrating inflammatory and immune cells, together with the extracellular matrix, cytokines, nitric oxide, and oxygen levels) which are also exposed to radiation during therapy, and their crosstalk might influence tumor stem cells’ response to radiation [42, 49]. The critical role of the microenvironment, along with GSCs, is supported directly and indirectly by the observation that GSCs reside in specific niches, distinct compartmentalized regions that present morphologically and functionally distinct functions (Fig. 2) [50]. The stem cell niche plays an indispensable role in homeostasis, regeneration, maintenance, and repair. There are at least three specialized tumor niches in GBM that include the vasculature as an integral regulatory component, including the perivascular tumor niche, vascular-invasive tumor niche, and hypoxic-necrotic tumor niche. These niches are dependent not only on normal cell components in the tumor microenvironment but also on the genetic and epigenetic profiles of GSCs. The different combinations of cell components and functional statuses of the vasculature promote specific features and functions in the niches, as reviewed by Hambardzumyan and Bergers [50]. In addition to GSC maintenance, the niches could undergo dynamic alterations in a temporal and spatial manner and create a succession of tumor microenvironments to accommodate the aggressive growth of a tumor such as GBM into normal tissue, both during tumor progression and in response to therapeutic agents. In this context, some therapies could convert a tumor niche into another niche type instead of eliminating it, thereby losing their effectiveness. According to Hambardzumyan and Bergers, it is likely, for instance, that therapies such as radiation and cytotoxic chemotherapies, which create hypoxia and necrosis, may enhance hypoxic niches that will transition into perivascular tumor niches during tumor relapse [50]. Therefore, the understanding of the crosstalk between GSCs and their niches, which supports GSC self-renewal, tumor invasion, and metastasis, as well as GSC escape from therapy, has become a promising target. In this sense, Mannino and Chalmers proposed that radioresistance is a result of interactions between these cells and microenvironmental factors, i.e., the “microenvironment - stem cell unit” [51]. Brain hypoxia is known to be one of the most critical characteristics in the tumor microenvironment and is associated with the promotion of tumor progression and facilitation of angiogenesis, metabolism, and tumor radioresistance [52, 53], in addition to triggering mechanisms such as hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) signaling and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT). HIF signaling was also reported to be pivotal in GSC regulation [54]. Low oxygen levels were observed to prevent GSC differentiation, induce neurospheres, and maintain the potential of pluripotent embryonic and stemness markers [55, 56]. The link between hypoxic responses and GSCs was suggested by Li and coworkers, who found a differential response of GSCs to the HIF family of transcription factors, including promotion of their self-renewal [57]. Likewise, a proof-of-concept study using HIF knockdown in GSCs resulted in reduced stemness in vitro and in vivo [57]. It has also been described that hypoxia induced the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in HIF1- and HIF2-dependent GSCs [58]. A close relationship between CD133+ cells and vascular structures was also found in a study by Christensen and coworkers [59].

Moreover, two independent groups showed that the CD133+ subpopulation is capable of de novo tumor vascularization through direct differentiation into endothelial cells, suggesting that a therapy targeting angiogenic factors would be required to inhibit GBM stem cells and tumor neovascularization [60, 61]. Finally, it has also been shown that GBM cells irradiated under orthotopic conditions have a higher capacity for DSB repair than GBM cells irradiated in vitro, which resulted in the induction of fewer γH2AX and 53BP1 foci in CD133+ cells than in CD133− cells [62]. The authors also showed an increase in the percentage of CD133+ cells at 7 days after radiation, which persisted at the onset of neurologic symptoms, suggesting that CD133+ cells are relatively radioresistant under intracerebral growth conditions [62].

Role of autophagy in mediating radioresistance

Autophagy is a conserved cellular process that is crucial for maintaining cellular homeostasis and survival and differentiation. Therefore, it is associated with a variety of pathologies [63]. In contrast to apoptosis, autophagy is a double-edged sword that could be either protective or detrimental to cells, depending on the nature of the stimulus (nutrient and growth factor deprivation or an external insult like radiation) and the extent of autophagy induction [64]. Recent studies suggest that autophagy has been recognized as frequently activated in cancer and mediates tumor cells’ response to anticancer therapy, especially radiotherapy, decreasing its efficacy by contributing to GSC maintenance and reducing ROS-associated DNA damage [65, 66]. Moreover, radiation preferentially activates autophagy in CD133+ cells and increases the levels of the autophagy-related proteins LC3, ATG5, and ATG12 [67]. The same was found in the radioresistant cell line, in which enhanced autophagic flux and silencing of the LC3A gene sensitized mouse xenografts to radiation [68]. However, in a study examining the induction of autophagy by radiation and its role in the radioresistance of GSCs, the authors found that GSCs expressed lower levels of autophagy-related protein LC3 and radiation induced a low degree of autophagy in these cells [69]. Moreover, a recent study showed that autophagy induction by the mammalian targets of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor rapamycin triggers GSC differentiation and enhances their radiosensitization in vitro and in vivo, with rapamycin thus becoming a promising tool for radiosensitization in glioma [70, 71].

Chemoresistance

Role of repair mechanism mediating chemoresistance

The resistance of GSCs to chemotherapeutic drugs has been well documented, yet the importance of DNA repair remains unclear. A recent study calls into question whether the differential and more efficient DNA repair system is specific to all CSCs, since the effects of TMZ require efficient DNA repair (mismatch repair system) [72, 73]. Moreover, the extensive heterogeneity within GBM can complicate the role of the DNA repair system in GSCs [72]. The DNA repair protein MGMT is the best-characterized repair protein and is a crucial modulator of TMZ chemoresistance in GBM [74–76]. MGMT is expressed in GBM at various levels, and reports of its expression in the GSC compartments remain conflicting [77, 78]. Nevertheless, there is consensus that MGMT expression substantially increases the resistance of GSC [77–79]. A recent report showed MGMT expression in half of the CD133+ cell lines tested, and the majority of these cell lines were resistant to TMZ. This result may suggest the presence of an alternative MGMT-independent mechanism of therapeutic resistance [80].

Role of multidrug mediating chemoresistance

Another mechanism involved in chemoresistance is multidrug resistance. However, its role in GSCs remains an open question. Normal and cancer stem cells have higher expression levels of several ABC transporters, which confer them with efflux ability for the fluorescent dye Hoechst 33342 and helps GBMs with the efflux of antineoplastic drugs [81]. In line with this, increased ABCG1 expression was reported in TMZ-induced cells (the side population cells in flow cytometry that present the GSC phenotype) [82], and enhanced expression of multidrug resistance 1 (MDR1) was found in the chemoresistant phenotype of CD133+ GSCs compared to bulk CD133− [83, 84]. Although ABCB1 can be an independent predictor for TMZ responsiveness [85], there is conflicting data regarding TMZ transport by these proteins. Bleu and coworkers showed that TMZ is not a substrate for the ABCG1 transporter [72, 86] in murine glioma cells.

On the other hand, ABCG2/BCRP and ABCB1/MDR1 overexpression in GSCs was correlated with higher resistance of GSCs to chemotherapeutic drugs. Accordingly, the use of an ABC transporter inhibitor, such as verapamil, can decrease temozolomide, doxorubicin, and mitoxantrone resistance in GSCs [87]. Besides, melatonin (N-acetyl-5-methoxytryptamine) increased methylation levels of the ABC transporter ABCG2/BCRP promoter, promoting a synergistic toxic effect with TMZ on GSCs and A172 malignant glioma cells [87]. Moreover, reversan, an inhibitor of the MRP1 protein, increased the sensitivity of primary and recurrent GBM cells to TMZ treatment; however, this effect has not yet been evaluated exclusively in GSCs [88].

Role of apoptosis and autophagy in mediating chemoresistance

The mechanisms of action of TMZ, such as apoptosis, senescence, and autophagy, have also been described in GSCs [72, 89]. Prolonged treatment with TMZ can induce p53 and p21WAF1/Cip1 and cell cycle arrest (G2/M arrest), although genetic background dependence is observed in GBM cell lines. Continued treatment also promotes apoptosis, but senescence is the major process observed in glioma and melanoma tumors or cell lines [72, 89, 90]. Concerning apoptosis, following TMZ exposure, higher expression levels of antiapoptotic genes were observed in GSCs than in differentiated cell lines, suggesting a possible link between GSC chemoresistance and antiapoptotic factors [84, 91]. It was also reported that drug resistance observed in GSCs might depend on abnormalities in the cell death pathway, such as the overexpression of antiapoptotic factors or silencing of key death effectors [92]. The autophagy process or autophagic cell death induction can also be observed in response to TMZ and contributes to glioma chemoresistance and TMZ treatment failure [93, 94].

Moreover, in GSCs obtained from freshly resected GBM specimens, the expression of autophagy-related proteins (i.e., Beclin-1, ATG55, and LC3) was decreased in CD133+ cells compared with CD133− cells after TMZ exposure. The authors suggested that GSCs might not be susceptible to classical pathways of autophagy [95]. On the other hand, rapamycin induces the differentiation of GSCs by activating autophagy [96, 97]. Increased rates and numbers of neurospheres in the rapamycin group compared with other groups were also reported. Additionally, stem/progenitor cell and differentiation markers were downregulated and upregulated in rapamycin-treated cells, respectively [97]. These data suggest that apoptosis and autophagy might contribute to GSC chemoresistance.

Role of Notch and Sonic hedgehog pathways in mediating chemoresistance

The increased expression of proteins of the Notch and Sonic hedgehog (SHH) pathways in CD133+ cells compared with GBM cells has already been described [98]. The comparison between treated and non-treated CD133+ primary GBM cells showed upregulated expression of the NOTCH 1, NCOR2, HES1, HES5, and GLI1 genes after TMZ treatment, suggesting the increased activity of these pathways [99]. Moreover, the use of Notch or SHH inhibitors with TMZ reversed the resistance to TMZ [99].

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) mediates GBM chemoresistance

The epithelial-mesenchymal transition process can also contribute to GBM chemoresistance. This was exploited through the gene ZEB1, an EMT regulator, and a known regulator of stemness and SOX2 in solid tissue cancers [100]. In GBM, the overexpression of the ZEB1 gene induced the expression of MGMT, resulting in greater tumor chemoresistance and also induced the expression of SOX2 and OLIG2, resulting in greater stemness and higher capacity for tumor formation [101].

Other mechanisms mediating chemoresistance—extrinsic pathways

Previous studies reported that TMZ might eliminate CSCs under in vitro conditions [72, 77]. However, patients treated with TMZ, present no stabilized disease or recurrence, leading to fatal relapses [74], suggesting that other mechanisms, such as residual CSC survival, may occur in vivo. Other extrinsic factors, such as the microenvironment, contribute to the chemoresistance of solid tumors [72]. Hjelmeland and coworkers demonstrated that exposure to an acidic pH environment promoted malignancy in GBM through the induction of a GSC phenotype [102]. Moreover, cell-cell interactions and IL-6 protein expression constitute indirect evidence suggesting that these mechanisms may be relevant for GSCs [72, 103]. Several reports suggest that tumor cell stemness could be induced by tumor microenvironments such as hypoxia [57, 79, 104] and drugs such as TMZ [80]. In line with this, tumor cells can acquire CSC properties [80, 105]. A recent report showed essential data concerning the origin, development, and maintenance of the GSC population after TMZ treatment. In this study, the authors achieve the conversion of non-GSCs to GSCs, both in vitro and in vivo, after long-term exposure to clinically relevant doses of TMZ. They showed that newly formed GSCs expressed molecular markers associated with parental GSCs, displayed a high rate of tumor engraftment and had a more invasive phenotype. These data suggest that the stemness of GSCs may be governed by cellular plasticity and that TMZ can stimulate the dedifferentiation of non-GSCs, explaining the high rates of tumor recurrence after conventional therapy [80].

Current strategies targeting cancer stem cells

The discovery of pathways essential for modulating stemness properties has contributed to the identification of several molecules that could eliminate GSCs, including new antineoplastic agents from natural sources [106–113]. A summary of current potential treatments is presented in Table 1 and Fig. 3.

Table 1.

Summary of current therapeutic strategies for some natural products and their chemical derivatives in GSCs. The structure, biological targets, analysis methods, clinical phase andchanism of 38 natural compounds/or derivatives are described

| Compound | Therapeutic/structure | Biological targets/mechanism of action | Evaluated | Clinical trials | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

Cyclopamine (11-deoxojervine)

|

Target Hedgehog pathway. Promote inhibition of side and aldefluor-positive populations. |

In vitro and in vivo | No |

PubChem CID: 442972 |

| 2 |

Guggulsterone

|

Promote intrinsic apoptosis of GSCs and sensitize cells to SANT-1. Targeting Ros/NF-κB and Hedgehog. |

In vitro | No |

PubChem CID: 6450278 |

| 3 |

CX-4945 (Silmitasertib)

|

Target several GSC factors and markers Casein kinase 2 selective inhibitor. |

In vitro and in vivo | Yes |

PubChem CID: 24748573 |

| 4 |

SCH 900776

|

DNA repair inhibitors Promote radio-chemosensitivity. Promote CHK1 inhibition. |

In vitro and in vivo | Yes |

PubChem CID: 46239015 |

| 5 |

SAR-020106

|

DNA repair inhibitor Promote CHK1 inhibition |

In vitro and in vivo | Yes |

PubChem CID: 44203948 |

| 6 |

AZD7762

|

DNA repair inhibitor Promote radio-chemosensitivity. Promote CHK1, CHK2, and ATM protein inhibition. |

In vitro and in vivo | Yes |

PubChem CID: 11152667 |

| 7 |

Debromohymenialdisine (DBH)

|

DNA inhibitors Promote radio-chemosensitivity. Promote CHK1, CHK2, and ATM protein inhibition. |

In vitro and in vivo | Yes |

PubChem CID: 135451156 |

| 8 |

Erlotinib

|

EGFR inhibitors Promote proliferation and self-renewal inhibition. Promote cell death. |

In vitro and in vivo | Yes |

PubChem CID: 176870 |

| 9 |

Gefitinib

|

EGFR inhibitors Promote proliferation and self-renewal inhibition. Promote cell death. |

In vitro and in vivo | Yes |

PubChem CID: 123631 |

| 10 |

Rapamycin (Sirolimus)

|

Promote GSC differentiation. Reduce stem cell markers. Promote radiosensitivity. |

In vitro and in vivo | Yes |

[36, 67, 69, 97, 130, 133–135] PubChem CID: 5284616 |

| 11 |

Chloroquine (CQ)

|

Promote radiosensitivity Inhibit autophagy process. |

In vitro and in vivo | Yes |

PubChem CID: 2719 |

| 12 |

Cilengitide

|

Promote αv integrin inhibition. Promote GSCs autophagy, cytotoxicity, and cell death Promote radiosensitivity. |

In vitro and in vivo | Yes |

[138] PubChem CID: 176873 |

| 13 |

AZD2014 (Vistusertib)

|

Promote mTORC1/2 inhibition. Promote radiosensitivity. Promote DNA double-strand break repair inhibition. |

In vitro and in vivo | Yes |

PubChem CID: 25262792 |

| 14 |

Eckol

|

Promote radiosensitivity and TMZ sensitivity. Reduce neurosphere formation and stem cell markers Target PI3-kinase-Akt and Ras-Raf-1-Erk signaling pathways. |

In vitro and in vivo | No |

[107] PubChem CID: 145937 |

| 15 |

Nordy

|

Promote GSC differentiation. Reduce proliferation, stem cell markers, and self-renewal Target ALOX5 |

In vitro and in vivo | No |

[108] PubChem CID: 319062914 |

| 16 |

Resveratrol

|

Promote radiosensitivity and differentiation of GSCs. HIF inhibitor. Induce apoptosis of CD133+ cells. Target STAT3 pathway |

In vitro and in vivo | No |

PubChem CID: 445154 |

| 17 |

STX-0119

|

Promote inhibition of GSCs proliferation. Reduce stem cell markers. STAT3 inhibitor. |

In vitro and in vivo | Yes |

[142] PubChem CID: 4253236 |

| 18 |

ER400583-00

|

HIF inhibitors Reduce neurosphere formation and stem cell markers Inhibit VEGF signaling Promote microenvironment modulation. Reduce HIF-1 expression. |

In vitro and in vivo | No |

Not available on PubChem |

| 19 |

WP1193

|

Analog of natural product caffeic acid benzyl ester Reduce proliferation and stem cell markers Induce apoptosis Promote G1 arrest decrease of cyclin D1 and p21(Cip1/Waf-1) increase Inhibit JAK2/STAT3 |

In vitro and in vivo | No |

[112] Not available on PubChem |

| 20 |

All-trans-retinoic acid (Vitamin A acid)

|

Promote differentiation Reduce proliferation and nestin stem cell markers Promote apoptosis Target ERK1/2 signaling |

In vitro and in vivo | No |

PubChem CID: 444795 |

| 21 |

Tanshinone IIA

|

Promote suppression of GSC proliferation. Reduce stem cell markers. Promotes the increase of GSCs differentiation markers. Induce GSCs apoptosis. Reduce the IL6/STAT3 signaling pathway. |

In vitro and in vivo | No |

[155] PubChem CID: 164676 |

| 22 |

Oleanolic acid

|

Promote suppression of JAK-STAT3 activation in M2 polarization of tumor-associated macrophages. | In vitro | No |

[156] PubChem CID: 10494 |

| 23 |

WP1066

|

Promote STAT3 inhibition Decrease the surviving fraction of GSC |

In vitro and in vivo | Yes |

Not available on PubChem |

| 24 |

Bevacizumab >Bevacizumab light chain DIQMTQSPSSLSASVGDRVTITCSASQDISNYLNWYQQKPGKAPKVLIYFTSSLHSGVPSRFSGSGSGTDFTLTISSLQPEDFATYYCQQYSTVPWTFGQGTKVEIKRTVAAPSVFIFPPSDEQLKSGTASVVCLLNNFYPREAKVQWKVDNALQSGNSQESVTEQDSKDSTYSLSSTLTLSKADYEKHKVYACEVTHQGLSSPVTKSFNRGEC >Bevacizumab heavy chain EVQLVESGGGLVQPGGSLRLSCAASGYTFTNYGMNWVRQAPGKGLEWVGWINTYTGEPTYAADFKRRFTFSLDTSKSTAYLQMNSLRAEDTAVYYCAKYPHYYGSSHWYFDVWGQGTLVTVSSASTKGPSVFPLAPSSKSTSGGTAALGCLVKDYFPEPVTVSWNSGALTSGVHTFPAVLQSSGLYSLSSVVTVPSSSLGTQTYICNVNHKPSNTKVDKKVEPKSCDKTHTCPPCPAPELLGGPSVFLFPPKPKDTLMISRTPEVTCVVVDVSHEDPEVKFNWYVDGVEVHNAKTKPREEQYNSTYRVVSVLTVLHQDWLNGKEYKCKVSNKALPAPIEKTISKAKGQPREPQVYTLPPSREEMTKNQVSLTCLVKGFYPSDIAVEWESNGQPENNYKTTPPVLDSDGSFFLYSKLTVDKSRWQQGNVFSCSVMHEALHNHYTQKSLSLSPGK |

Promote disruption of vascular niche and reduce tumor proliferation. Promote radiosensitivity. Reduce proliferation and block GSC ability to induce endothelial cell migration. VEGF inhibitor |

In vitro and in vivo | Yes |

DrugBank: DB00112 |

| 25 |

Cediranib (AZD2171)

|

Promote disruption of the vascular niche and reduce tumor proliferation. Promote radiosensitivity. Reduce proliferation and block GSC ability to induce endothelial cell migration. VEGF inhibitor |

In vitro and in vivo | Yes |

PubChem CID: 9933475 |

| 26 |

Honokiol

|

Promote PI3K/mTOR signaling inhibition. Promote proliferation inhibition of side positive populations. Promote TMZ-resistant cell sensitivity. Promote DNA double-strand break repair inhibition. |

In vitro and in vivo | Yes |

PubChem CID: 72303 |

| 27 |

Manassantin B

|

Target hypoxia-inducible factor-1. | In vitro | No |

[111] PubChem CID: 10439828 |

| 28 |

Curcumin

|

Induce GSCs apoptosis. Target hypoxia-inducible factor-1. |

In vitro and in vivo | No |

PubChem CID: 969516 |

| 29 |

SU5416 (Semaxinib)

|

Reduce neurosphere formation and stem cell markers Reduce HIF-1 expression Inhibit VEGF signaling Target PI3K/AKT/p70S6K1 signaling pathway |

In vitro and in vivo | No |

[147] PubChem CID: 5329098 |

| 30 |

Cannabinoids therapies

|

Promote differentiation. Inhibit gliomagenesis. Target cannabinoid type 1 (CB1) and type 2 (CB2) receptors. |

In vitro and in vivo | No |

[157] PubChem CID: 9852188 |

| 31 |

Vorinostat (SAHA)

|

Promote GSC differentiation. Promote G1/S arrest of GSCs. Inhibit histone deacetylases (HDACs). |

In vitro and in vivo | Yes |

PubChem CID: 5311 |

| 32 |

Sahaquine

|

Promote HDAC inhibition Reduce GSC viability Reduce invasiveness |

In vitro | No |

[138] Not available on PubChem |

| 33 |

VX680

|

Pan-AURK inhibitor Induce apoptosis Reduce tumor growth |

In vitro and in vivo | No |

[172] PubChem CID 5494449 |

| 34 |

MLN8237 (Alisertib)

|

Promote GSC colony formation inhibition. Promote radiosensitivity and TMZ sensitivity. Aurora-A kinase inhibitor. |

In vitro and in vivo | No |

PubChem CID: 24771867 |

| 35 |

Metformin

|

Promote inhibition of GSC self-renewal. Reduce GSC viability. Promote inhibition of CD133+ proliferation. |

In vitro and in vivo | No |

PubChem CID: 4091 |

| 36 |

Telomestatin

|

Polyketide component Induce apoptosis and impair the migration potential of GSCs. Promote telomeric and nontelomeric DNA damage in GSCs. |

In vitro and in vivo | No |

[182] PubChem CID: 443590 |

| 37 |

Harmine

|

Alkaloid component Promote self-renewal inhibition. Promote GSC differentiation. Promote neurosphere formation inhibition. |

In vitro and in vivo | No |

[183] PubChem CID: 5280953 |

* For chemical structures, SDF files were retrieved from PubChem [184], and 2D structures were built on MarvinSketch (MarvinSketch 19.27.0, 2019, ChemAxon (http://www.chemaxon.com)

Fig. 3.

A schematic representation of the molecular signaling hallmarks of glial stem cell (CSC) and the effect of natural compounds and synthetic drugs on these molecular targets. In the dark red circle are represented natural compounds that target each hallmark. In light red are represented chemicals/synthetic drugs that targeted each hallmark in GSC. See text for details (created with Biorender.com)

Given the requirement for hedgehog (Hh) signaling in GSCs, a recent study investigated cyclopamine (11-deoxojervine) (1) and guggulsterone (2) [114, 185]. Cyclopamine can specifically inhibit the Hh pathway [117] as well as the side and aldefluor-positive populations, resulting in cultures unable to form colonies in preclinical studies and GSCs sensitized to radiation [118, 185]. Another important protein able to target different pathways (Hedgehog, Notch, and β-catenin) is casein kinase 2 (CK2) [119]. In GBM, CK2 expression and activity lead to tumor suppressor inhibition and oncogene activation contributing to gliomagenesis [119]. Moreover, CK2 inhibition promotes O6-methylguanine-DNA-methyltransferase downregulation and sensitizes glioma cells to TMZ [121]. CX-4945 (3) is potent, selective, and highly bioavailable compared to other CK2 inhibitors [121]. This novel molecule and its analogs target several GSC factors and markers and exhibit promising results in preclinical studies of several types of tumors, in vivo models and human clinical trials [121, 186].

Regarding the cell cycle and DNA damage repair [122, 123], there are several CHK1 and CHK2 inhibitors; CHK1 inhibitors in clinical development include SCH 900776 (NCT00779584) (4) and SAR-020106 (5) [124, 125]. AZD7762 (NCT00413686) (6) and debromohymenialdisine (DBH) (7) are novel potent checkpoint kinase inhibitors that inhibit both CHK1 and CHK2. AZD7762 was shown to potentiate chemotherapy response in several different settings and resulted in the abrogation of DNA damage-induced cell cycle arrest in vitro and in vivo in combination with DNA-damaging agents [126, 127]. The use of DBH and radiation treatment is synergistic: together they are able to abrogate the radioresistance of CD133+ cells, suggesting new options for combination radiotherapy [31, 128].

EGFR is a crucial receptor in the protocols described for growing GSCs, making clear that this pathway is necessary for GSC survival [129, 130]. Thus, it would be rational to use EGFR inhibitors to promote the inhibition of GSC proliferation and self-renewal and induce cell death [129, 137]. First-generation EGFR inhibitors such as erlotinib (8) and gefitinib (9) have been used in the clinical treatment of glioma patients, although less than 20% of patients presented a response to these treatments. However, EGFR inhibition has been observed to enhance the chemo- and radiosensitivity of human glioma CSCs [136, 137]. It is believed that the low response to these inhibitors is associated with loss of the tumor suppressor PTEN, which is usually deleted or mutated in gliomas and plays a critical role in maintaining neural precursor cells via activation of the mTOR pathway [133, 139]. Clinical results with rapamycin (10) have been described in patients with high-grade GBM [140, 141] and have demonstrated that treatment with rapamycin or combination with EGFR inhibitors may provide an alternative treatment for TMZ-resistant gliomas, regardless of EGFR status [134, 142].

Related to autophagy, the cell death and survival response can be influenced to favor cell death through several therapies that inhibit autophagy processes [155]. Chloroquine (CQ) (11) is an applicable autophagy inhibitor known to trigger apoptosis in conventional autophagic tumor cells and to improve mid-term survival in glioma when administered in addition to conventional therapy [187, 188]. Regarding GSCs, triple combinations of γIR, low-dose CQ, and PI3K/Akt pathway inhibitors or high-dose CQ alone induced strong cytotoxic effects in radioresistant GSCs [187]. Moreover, inhibitors such as bafilomycin A1 or beclin 1 and ATG5 shRNAs also sensitize GSCs to radiation and reduce their viability and capacity to form neurospheres [134, 189]. Likewise, radiation and the inhibition of αv integrin by cilengitide (12), which is currently in clinical evaluation, induce autophagy in GSCs, increasing cytotoxicity and reducing cell survival [190].

In addition, the association of mTOR inhibitors and radiation led authors to evaluate the effects of AZD2014 (13) [156], a competitive dual mTORC1/2 inhibitor, unlike rapamycin, an allosteric inhibitor, on the radiosensitivity of GSCs in in vitro and in vivo studies [191]. Beyond these properties, AZD2014 also penetrates the blood-brain barrier and has been reported in a Phase I clinical trial as a single agent [156, 159, 160]. The authors showed that AZD2014-mediated radiosensitization in GSCs promoted the inhibition of DSB repair as evaluated by a clonogenic assay according to γH2AX foci. Additionally, in GSC-initiated orthotopic xenografts, AZD2014, when combined with radiation, significantly prolonged mouse survival even when administered for only 3 days. These data indicate that AZD2014 may be a radiosensitizer applicable to GBM therapy [192].

Moreover, other molecules can decrease the stemness properties of GSCs, including eckol (14) [107], Nordy (15) [108], resveratrol (16) [109], STX-0119 (17) [161], ER400583-00 (18) [110], WP1193 (19) [111], angiogenesis inhibitors [143], all-trans-retinoic acid (20) [144], and Tanshinone IIA (21) [145]. Some of these molecules are linked to targets the microenvironment and thus indirectly modulate the stemness properties of cancer cells. However, these drugs cannot be used for a specific tumor type because the role of each niche in different tumor types and how they differ from one another is not yet known. This class includes molecules that primarily target angiogenesis and hypoxia [107, 108, 110, 111, 145].

Eckol (14), a phlorotannin compound from Ecklonia species, has been shown to attenuate in vitro anchorage-independent growth on soft agar and reduce sphere formation and GSC markers. Moreover, the CD133+ subpopulation and self-renewal-related proteins were decreased in response. The authors suggested that eckol activity could target PI3K/Akt and MAPK signaling pathways. Importantly, eckol treatment also decreases the resistance of GSCs to IR and TMZ and tumor formation in xenograft mice [107, 146].

The synthetic dl-nordihydroguaiaretic acid compound Nordy (15) was also shown to inhibit self-renewal properties, induce GSC differentiation, and decrease the GSC pool in vitro and in vivo. Alox-5 is a Nordy target that promotes the invasion and proliferation inhibition of GSCs. Moreover, Nordy promotes GFAP upregulation, angiogenesis inhibition, and stemness marker downregulation [108, 147].

Regarding pluripotency, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3), which is associated with the cell cycle and survival, regulation, immune response, and differentiation, has been described as a critical initiator and regulator of tumorigenic transformation in GBM and implicated among GSC maintenance factors. STAT3 has been related to oncogenic or tumor-suppressive roles in GBM depending on the tumor genotype [111, 167]. These novel therapies may be the basis for the next generation of GBM treatment. STAT3 signaling includes small molecules such as oleanolic acid (22) [168], STX-0119 (13) [161], and WP1066 (23) [157]. Resveratrol (16) (RV), a polyphenol in grapes, is known to be a potential noncytotoxic tumor-preventive drug targeting STAT3 signaling. In glioma, RV can induce apoptosis, enhance radiosensitivity in the CD133+ cell population, and decrease tumorigenicity in xenotransplant experiments. Furthermore, RV was able to inhibit cell proliferation and decrease cell motility by modulating the Wnt signaling pathway and EMT activators [109, 193].

Another novel molecule recently investigated is WP1066 (23), an analog of the natural product caffeic acid benzyl ester and a potent STAT3 pathway inhibitor. In glioma, this potent small-molecule inhibitor showed promise as a therapeutic agent by targeting GSCs and will be investigated in a clinical trial for patients with recurrent malignant glioma and brain metastasis from melanoma (recruiting, ClinicalTrials.gov). In addition, WP1066 can cross the blood-brain barrier and is orally bioavailable [157, 194].

Antiangiogenic agents that disrupt GBM-initiating cell maintenance have been widely investigated, but so far, only modest results have been obtained. Moreover, some reports have indicated that glioma develops resistance to the employed antiangiogenic treatments [195, 196]. To date, in highly vascular tumors such as gliomas [149, 197], angiogenesis inhibition has improved progression-free survival, although no cure has been achieved. Clinical trials using bevacizumab (BEV) (24) and cediranib (AZD2171) (25) (Phase I) alone or in combination have demonstrated efficacy in GBM patients [164, 165]. In in vivo experimental studies with mice, BEV treatment decreased GSCs and the growth rate of GBMs [2].

Regarding clinical trials, BEV (24) has been combined with irinotecan (Phase II) and pazopanib, also an oral multitarget angiogenesis inhibitor (GW786034) (Phases I and II) [143, 164, 165]. A study also demonstrated that BEV or interferon-beta could enhance radiosensitivity in orthotopic GBM [171]. However, recent studies suggest that inhibition of angiogenesis is even a driving force for tumor conversion to a higher malignancy state, inducing a phenotypic change from single-cell infiltration to migration of cell clusters along normal blood vessels, which is reflected in higher invasion, enhanced metastatic activity and dissemination [150, 196].

Moreover, antiangiogenic therapy changes tumor vasculature, leading to hypoxia [196]. The hypoxia phenotype has been demonstrated as a marker of antiangiogenic therapy resistance by HIF-1α and stromal-cell derived factor-1α (SDF-1α) upregulation leading to the recruitment of various pro-angiogenic bone marrow-derived cells [196]. For hypoxia modulation, compelling data demonstrate that the downregulation of HIF2-α can increase stem cell/pluripotency markers, neurosphere formation, and the VEGF pathway [57, 151]. Thus, several molecules that inhibit or indirectly modulate the expression of HIF-1 have been investigated, although they showed little efficacy either alone or in combination with standard antitumor agents [152]. For instance, honokiol (26), manassantin (27) B from Saururus cernuus and Saururus chinensis, curcumin from Curcuma spp. (28), resveratrol (16), SU5416 (29), and ER400583-00 (18) are inhibitors that have been developed [106, 109, 110, 153, 164, 198, 199].

Honokiol (26) is one of the biphenolic bioactive compounds isolated from Magnolia officinalis, possessing multifunctional activities in addition to crossing the blood-brain barrier [173, 174]. Honokiol specifically inhibits PI3K/mTOR signaling activation in gliomas [173, 175], promotes the elimination of GSCs, and reverses TMZ resistance using GBM8401 SP cells, which appear to have higher expression of MGMT and to be more resistant to TMZ. This inhibition is accompanied by a greater induction of apoptosis and reduced expression levels of EGFR, CD133, and Nestin, suggesting that honokiol might have clinical benefits for GBM patients, mainly those who are refractory to TMZ treatment [75, 173, 176].

Furthermore, several agents, such as cannabinoids (30), are known to exert antitumor action on GBM by apoptosis induction and tumor angiogenesis inhibition and have been recently evaluated in GSC differentiation control. The study provides further support for the hypothesis that cannabinoid changes reduce glioma initiation (neurosphere formation and cell proliferation) in vivo. These effects were greater in combination with TMZ and correlated with an increase in cell differentiation [177, 200]. Another strategy to reduce the tumorigenic potential of GSCs and promote differentiation is to induce bone morphogenic proteins (BMP) signaling [165, 178]. The potential of BMP induction of astrocyte differentiation from normal neural precursors has been reported in vitro and in vivo [149, 205]. Most importantly, BMP4 has been shown to trigger a significant decrease in GSCs [165, 178, 179]. Even with BMP signaling, it was identified that BMP2 heightens sensitivity to TMZ in GSCs in which MGMT expression was described as directly downregulated by HIF-1α at the transcriptional level [180, 201].

The epigenetic modulation of histone acetylation by histone deacetylase (HDAC) activity has been associated with several cancer types [182, 202]. The HDAC inhibitor, vorinostat (suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid, SAHA) (31), and sahaquine (32) are currently in Phase I clinical trials [138, 183, 203] in GBM. In vitro, SAHA has shown antiproliferative effects by blocking G1/S phase progression, increasing the levels of apoptosis-related genes and inducing the expression of cleaved PARP and p-γH2AX in GSCs [204]. Sahaquine inhibits HDAC6, leading to a reduction in the viability and invasiveness of glioblastoma tumors and brain tumor stem cells [138]. Most importantly, HDAC inhibitor treatment under culture proliferation conditions suggests the induction of differentiated cell states in adult mouse neural stem cells [205].

In addition, all-trans-retinoic acid (ATRA) (20), a differentiating agent used in clinical practice, is a natural compound derivative of retinoic acid, also known as vitamin A [202, 206]. Some findings reported its capacity for differentiating stem cells as well as normal neural progenitor cells and downregulating the expression of the stem cell marker nestin [207, 208]. An additional study revealed that a combination of ATRA and paclitaxel was able to synergistically reduce GBM tumor growth in both in vivo and in vitro models [209]. GSCs differentiated into glial and neuronal lineages even at low concentrations of ATRA. Moreover, ATRA decreased proliferation and self-renewal of neurospheres and promoted apoptosis at high concentrations, targeted ERK1/2 signaling, induced cell cycle arrest at the G1/G0 to S transition, decreased cyclin D1 expression, and increased p27 expression [206, 210].

Another agent with antiproliferative and prodifferentiation effects in GSCs is aurora-A kinase (AURK), a crucial serine-threonine kinase [211, 212] observed to be variably overexpressed in gliomas [211, 213]. AURK is also a vital kinase that governs self-renewal capacity in GBM tumorsphere cultures [172]. These authors used a pan-AURK inhibitor, VX680 (33), followed by radiation, in cell culture and xenograft models, and demonstrated the induction of apoptosis and reduction of tumor growth [172]. Hong and coworkers also demonstrated that MLN8237 (alisertib) (34) [214–216], a highly selective AURK inhibitor, inhibits colony formation in GSCs and potentiates the effects of radiation and TMZ in glioblastoma monolayers and GSCs [217]. Importantly, MLN8237 is relatively non-toxic to normal human astrocytes.

Another emerging antiglioma drug is metformin (35), a drug used mainly for the therapy of type 2 diabetes and polycystic ovary syndrome [218, 219]. Metformin treatment in vitro was able to block cell cycle progression (G0/G1 phase), although cell death was not observed in GBMs [220]. In a recent report, metformin selectively and remarkably affects GSC viability in vitro [221]. The authors showed that AKT and the transcription factor forkhead box O3 (FOXO3) are involved in the molecular mechanism of metformin activity in GSCs [222, 223]. The effects of metformin were also validated in preclinical glioma orthotopic animal models, in which metformin administration resulted in a decrease of the self-renewing properties and tumor-initiating subpopulation [162, 224]. Clinical trials on the use of metformin alone and cancer treatment (including glioma) and prevention are ongoing [219, 224].

Maruccia and coworkers reviewed exciting results obtained with forty-nine different natural products, including flavonoids, alkaloids, polyketides, and acid derivatives [225]. One terpene or terpenoid compound class that has been reported in GSCs is the retinoic acids (all-trans), which are potent differentiating agents [144, 226]. The retinoic acids induce the in vitro differentiation of GSCs and impair the secretion of angiogenic cytokines and GSC motility, promoting synergistic therapy. The antitumor mechanism is associated with the downregulation of Wnt/-catenin signaling [166]. Well-characterized polyketides are telomestatin (36) and derivatives from Streptomyces anulatus, able to induce apoptosis and impair migration potential of GSCs in vitro and in vivo and to moderately change non-GSCs and normal neural precursors. Moreover, these macrocyclic compounds also promoted telomeric and nontelomeric DNA damage in GSCs [227, 228]. Two different alkaloids have been reported to be active against GSCs: cyclopamine (1) from Veratrum californicum and harmine (37) from Peganum harmala [55, 115, 170]. It was demonstrated that harmine inhibits self-renewal and induces GSC differentiation. In particular, harmine inhibits neurosphere formation of human primary glioblastoma GSCs and AKT phosphorylation [229].

Conclusion

The development of effective therapy for GBM remains a significant challenge in molecular oncology due to several questions mentioned above. Here, we have discussed several bioactive products that have been reported to modulate GSCs and shown to be essential for therapeutic applications. Although the detailed underlying mechanisms are unknown, bioactive products hold promise for the development of new drugs to treat glioma. Advances in understanding the pathomechanisms of glioma and the identification of GSC properties and therapeutic targets in the GSC subpopulation offer new directions for the development of novel therapies, either isolated or in combination, using personalized targeting for primary brain tumors, which is further emphasized in strategies for basic and translational research with natural compounds.

Papers of special note have been highlighted as either of interest (76, 93) or of considerable interest (15, 39, 78, 112) to readers

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge Tatiana Honda Morais for discussion of the manuscript and Caio Fernando Oliveira for the excellent assistance in using the Biorender platform.

Abbreviations

- ATM

Ataxia-telangiectasia mutated

- ATRA

All-trans retinoic acid

- ATR

Ataxia-telangiectasia and Rad3 related

- ATRX

Alpha-thalassemia/mental retardation syndrome X-linked

- BMP

Bone morphogenic proteins

- Bev

Bevacizumab

- CSC

Cancer stem cell

- CXCR4

C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 4

- CDKN2A

Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A

- CD184

CXCR4 chemokine receptor

- CQ

Chloroquine

- DBH

Debromohymenialdisine

- DSBs

DNA double-strand breaks

- FOXO3

Forkhead box O3

- GBM

Glioblastoma

- GFAP

Glial fibrillary acidic protein

- GSC

Glial stem cell

- EMT

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition

- HDACs

Histone deacetylase

- HIF

Hypoxia-inducible factor

- IDH-1

Isocitrate dehydrogenase 1

- TP53

Tumor protein P53

- IR

Ionizing radiation

- EFGR

Epidermal growth factor receptor

- LC3

Microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3

- MGMT

O6-methylguanine-DNA-methyltransferase

- MDR1

Expression of multidrug resistance 1

- mTOR

Mammalian targets of rapamycin

- PTEN

Phosphatase and tensin homolog

- TERT

Telomerase reverse transcriptase

- Rv

Resveratrol

- STAT3

Activator of transcription 3

- SDF1 α

Stromal-cell derived factor-1α

- TMZ

Temozolomide

- VEGF

Vascular endothelial growth factor

Authors’ contributions

ACC, VAOS, and RMR contributed to the conceptualization. ALVA, INFG, ACC, MNR, LSdS, AFE, and VAOS contributed to the investigation and wrote the original draft of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by FAPESP (Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo) (grants 2019/05142-4 – A.L.V.A; 2017/22305-9- I.N.F.G), Public Ministry of Labor Campinas (Research, Prevention and Education of Occupational Cancer) – L.S.S, CAPES and Barretos Cancer Hospital, all from Brazil.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Ana Laura V. Alves and Izabela N. F. Gomes contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Ostrom QT, Cioffi G, Gittleman H, et al. CBTRUS Statistical Report: primary brain and other central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2012–2016. Neuro Oncol. 2019;21(Supplement_5):v1–v100. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noz150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, et al. The 2016 World Health Organization classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131(6):803–20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Patterson JD, Wongsurawat T, Rodriguez A. A glioblastoma genomics primer for clinicians. Med Res Arch. 2020;8(2):1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Hanif F, Muzaffar K, Perveen K, et al. Glioblastoma Multiforme: a review of its epidemiology and pathogenesis through clinical presentation and treatment. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2017;18(1):3–9. doi: 10.22034/APJCP.2017.18.1.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xu H, Zong H, Ma C, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor in glioblastoma. Oncol Lett. 2017;14(1):512–516. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.6221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eckel-Passow JE, Lachance DH, Molinaro AM, et al. Glioma groups based on 1p/19q, IDH, and TERT promoter mutations in tumors. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(26):2499–2508. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1407279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Foote MB, Papadopoulos N, Diaz LA., Jr Genetic classification of gliomas: refining histopathology. Cancer Cell. 2015;28(1):9–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brat DJ, Aldape K, Colman H, et al. cIMPACT-NOW update 5: recommended grading criteria and terminologies for IDH-mutant astrocytomas. Acta Neuropathol. 2020;139(3):603–608. doi: 10.1007/s00401-020-02127-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chaurasia A, Park SH, Seo JW, et al. Immunohistochemical analysis of ATRX, IDH1 and p53 in glioblastoma and their correlations with patient survival. J Korean Med Sci. 2016;31(8):1208–1214. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2016.31.8.1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lathia JD, Mack SC, Mulkearns-Hubert EE, et al. Cancer stem cells in glioblastoma. Genes Dev. 2015;29(12):1203–1217. doi: 10.1101/gad.261982.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, Truitt G, et al. CBTRUS Statistical Report: primary brain and other central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2011–2015. Neuro Oncol. 2018;20(suppl_4):iv1–iv86. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noy131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aparicio-Blanco J, Sanz-Arriazu L, Lorenzoni R, et al. Glioblastoma chemotherapeutic agents used in the clinical setting and in clinical trials: Nanomedicine approaches to improve their efficacy. Int J Pharm. 2020;581:119283. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2020.119283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taylor OG, Brzozowski JS, Skelding KA. Glioblastoma Multiforme: an overview of emerging therapeutic targets. Front Oncol. 2019;9:963. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.00963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lapidot T, Sirard C, Vormoor J, et al. A cell initiating human acute myeloid leukaemia after transplantation into SCID mice. Nature. 1994;367(6464):645–648. doi: 10.1038/367645a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ignatova TN, Kukekov VG, Laywell ED, et al. Human cortical glial tumors contain neural stem-like cells expressing astroglial and neuronal markers in vitro. Glia. 2002;39(3):193–206. doi: 10.1002/glia.10094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hemmati HD, Nakano I, Lazareff JA, et al. Cancerous stem cells can arise from pediatric brain tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(25):15178–15183. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2036535100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kondo T, Setoguchi T, Taga T. Persistence of a small subpopulation of cancer stem-like cells in the C6 glioma cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(3):781–786. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307618100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh SK, Clarke ID, Terasaki M, et al. Identification of a cancer stem cell in human brain tumors. Cancer Res. 2003;63(18):5821–5828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singh SK, Hawkins C, Clarke ID, et al. Identification of human brain tumour initiating cells. Nature. 2004;432(7015):396–401. doi: 10.1038/nature03128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pollard SM, Yoshikawa K, Clarke ID, et al. Glioma stem cell lines expanded in adherent culture have tumor-specific phenotypes and are suitable for chemical and genetic screens. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4(6):568–580. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCord AM, Jamal M, Williams ES, et al. CD133+ glioblastoma stem-like cells are radiosensitive with a defective DNA damage response compared with established cell lines. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(16):5145–5153. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Galli R, Binda E, Orfanelli U, et al. Isolation and characterization of tumorigenic, stem-like neural precursors from human glioblastoma. Cancer Res. 2004;64(19):7011–7021. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dirks PB. Brain tumor stem cells: the cancer stem cell hypothesis writ large. Mol Oncol. 2010;4(5):420–430. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pallini R, Ricci-Vitiani L, Banna GL, et al. Cancer stem cell analysis and clinical outcome in patients with glioblastoma multiforme. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(24):8205–8212. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tomita T, Akimoto J, Haraoka J, et al. Clinicopathological significance of expression of nestin, a neural stem/progenitor cell marker, in human glioma tissue. Brain Tumor Pathol. 2014;31(3):162–171. doi: 10.1007/s10014-013-0169-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang M, Song T, Yang L, et al. Nestin and CD133: valuable stem cell-specific markers for determining clinical outcome of glioma patients. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2008;27:85. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-27-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bjerkvig R, Tysnes BB, Aboody KS, et al. Opinion: the origin of the cancer stem cell: current controversies and new insights. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5(11):899–904. doi: 10.1038/nrc1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ehtesham M, Mapara KY, Stevenson CB, et al. CXCR4 mediates the proliferation of glioblastoma progenitor cells. Cancer Lett. 2009;274(2):305–312. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.09.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Persano L, Rampazzo E, Basso G, et al. Glioblastoma cancer stem cells: role of the microenvironment and therapeutic targeting. Biochem Pharmacol. 2013;85(5):612–622. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soehngen E, Schaefer A, Koeritzer J, et al. Hypoxia upregulates aldehyde dehydrogenase isoform 1 (ALDH1) expression and induces functional stem cell characteristics in human glioblastoma cells. Brain Tumor Pathol. 2014;31(4):247–256. doi: 10.1007/s10014-013-0170-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bao S, Wu Q, McLendon RE, et al. Glioma stem cells promote radioresistance by preferential activation of the DNA damage response. Nature. 2006;444(7120):756–760. doi: 10.1038/nature05236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ma J, Yao Y, Wang P, et al. MiR-152 functions as a tumor suppressor in glioblastoma stem cells by targeting Kruppel-like factor 4. Cancer Lett. 2014;355(1):85–95. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang L, Yan Y, Jiang Y, et al. The expression of SALL4 in patients with gliomas: high level of SALL4 expression is correlated with poor outcome. J Neuro-Oncol. 2015;121(2):261–268. doi: 10.1007/s11060-014-1646-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Di Tomaso T, Mazzoleni S, Wang E, et al. Immunobiological characterization of cancer stem cells isolated from glioblastoma patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(3):800–813. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jung CS, Foerch C, Schanzer A, et al. Serum GFAP is a diagnostic marker for glioblastoma multiforme. Brain. 2007;130(Pt 12):3336–3341. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clement V, Dutoit V, Marino D, et al. Limits of CD133 as a marker of glioma self-renewing cells. Int J Cancer. 2009;125(1):244–248. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stieber D, Golebiewska A, Evers L, et al. Glioblastomas are composed of genetically divergent clones with distinct tumourigenic potential and variable stem cell-associated phenotypes. Acta Neuropathol. 2014;127(2):203–219. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1196-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bradshaw A, Wickremsekera A, Tan ST, et al. Cancer stem cell hierarchy in Glioblastoma Multiforme. Front Surg. 2016;3:21. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2016.00021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rosenblum ML, Gerosa M, Dougherty DV, et al. Age-related chemosensitivity of stem cells from human malignant brain tumours. Lancet. 1982;1(8277):885–887. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(82)92154-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morgan MA, Lawrence TS. Molecular pathways: overcoming radiation resistance by targeting DNA damage response pathways. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(13):2898–2904. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-3229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pilie PG, Tang C, Mills GB, et al. State-of-the-art strategies for targeting the DNA damage response in cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2019;16(2):81–104. doi: 10.1038/s41571-018-0114-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schulz A, Meyer F, Dubrovska A, et al. Cancer stem cells and Radioresistance: DNA repair and beyond. Cancers. 2019;11(6):1–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Tamura K, Aoyagi M, Ando N, et al. Expansion of CD133-positive glioma cells in recurrent de novo glioblastomas after radiotherapy and chemotherapy. J Neurosurg. 2013;119(5):1145–1155. doi: 10.3171/2013.7.JNS122417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tamura K, Aoyagi M, Wakimoto H, et al. Accumulation of CD133-positive glioma cells after high-dose irradiation by Gamma Knife surgery plus external beam radiation. J Neurosurg. 2010;113(2):310–318. doi: 10.3171/2010.2.JNS091607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Balbous A, Cortes U, Guilloteau K, et al. A radiosensitizing effect of RAD51 inhibition in glioblastoma stem-like cells. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:604. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2647-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.King HO, Brend T, Payne HL, et al. RAD51 is a selective DNA repair target to Radiosensitize Glioma stem cells. Stem Cell Rep. 2017;8(1):125–139. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2016.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ahmed SU, Carruthers R, Gilmour L, et al. Selective inhibition of parallel DNA damage response pathways optimizes radiosensitization of glioblastoma stem-like cells. Cancer Res. 2015;75(20):4416–4428. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-3790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Carruthers R, Ahmed SU, Strathdee K, et al. Abrogation of radioresistance in glioblastoma stem-like cells by inhibition of ATM kinase. Mol Oncol. 2015;9(1):192–203. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2014.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hambardzumyan D, Gutmann DH, Kettenmann H. The role of microglia and macrophages in glioma maintenance and progression. Nat Neurosci. 2016;19(1):20–27. doi: 10.1038/nn.4185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hambardzumyan D, Bergers G. Glioblastoma: defining tumor niches. Trends Cancer. 2015;1(4):252–265. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2015.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mannino M, Chalmers AJ. Radioresistance of glioma stem cells: intrinsic characteristic or property of the 'microenvironment-stem cell unit'? Mol Oncol. 2011;5(4):374–386. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Peitzsch C, Perrin R, Hill RP, et al. Hypoxia as a biomarker for radioresistant cancer stem cells. Int J Radiat Biol. 2014;90(8):636–652. doi: 10.3109/09553002.2014.916841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fidoamore A, Cristiano L, Antonosante A, et al. Glioblastoma stem cells microenvironment: the paracrine roles of the niche in drug and radioresistance. Stem Cells Int. 2016;2016:6809105. doi: 10.1155/2016/6809105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang P, Lan C, Xiong S, et al. HIF1alpha regulates single differentiated glioma cell dedifferentiation to stem-like cell phenotypes with high tumorigenic potential under hypoxia. Oncotarget. 2017;8(17):28074–28092. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bar EE, Lin A, Mahairaki V, et al. Hypoxia increases the expression of stem-cell markers and promotes clonogenicity in glioblastoma neurospheres. Am J Pathol. 2010;177(3):1491–1502. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.091021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.De Miguel MP, Alcaina Y, de la Maza DS, et al. Cell metabolism under microenvironmental low oxygen tension levels in stemness, proliferation and pluripotency. Curr Mol Med. 2015;15(4):343–359. doi: 10.2174/1566524015666150505160406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li Z, Bao S, Wu Q, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factors regulate tumorigenic capacity of glioma stem cells. Cancer Cell. 2009;15(6):501–513. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang G, Wang JJ, Fu XL, et al. Advances in the targeting of HIF-1alpha and future therapeutic strategies for glioblastoma multiforme (review) Oncol Rep. 2017;37(2):657–670. doi: 10.3892/or.2016.5309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Christensen K, Schroder HD, Kristensen BW. CD133 identifies perivascular niches in grade II-IV astrocytomas. J Neuro-Oncol. 2008;90(2):157–170. doi: 10.1007/s11060-008-9648-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang R, Chadalavada K, Wilshire J, et al. Glioblastoma stem-like cells give rise to tumour endothelium. Nature. 2010;468(7325):829–833. doi: 10.1038/nature09624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ricci-Vitiani L, Pallini R, Biffoni M, et al. Tumour vascularization via endothelial differentiation of glioblastoma stem-like cells. Nature. 2010;468(7325):824–828. doi: 10.1038/nature09557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jamal M, Rath BH, Tsang PS, et al. The brain microenvironment preferentially enhances the radioresistance of CD133(+) glioblastoma stem-like cells. Neoplasia. 2012;14(2):150–158. doi: 10.1593/neo.111794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yoshida GJ, Saya H. Therapeutic strategies targeting cancer stem cells. Cancer Sci. 2016;107(1):5–11. doi: 10.1111/cas.12817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Khandia R, Dadar M, Munjal A, et al. A comprehensive review of autophagy and its various roles in infectious, non-infectious, and lifestyle diseases: current knowledge and prospects for disease prevention, novel drug design, and therapy. Cells. 2019;8(7):1–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 65.Rouschop KM, van den Beucken T, Dubois L, et al. The unfolded protein response protects human tumor cells during hypoxia through regulation of the autophagy genes MAP 1LC3B and ATG5. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(1):127–141. doi: 10.1172/JCI40027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hou J, Han ZP, Jing YY, et al. Autophagy prevents irradiation injury and maintains stemness through decreasing ROS generation in mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Death Dis. 2013;4:e844. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lomonaco SL, Finniss S, Xiang C, et al. The induction of autophagy by gamma-radiation contributes to the radioresistance of glioma stem cells. Int J Cancer. 2009;125(3):717–722. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mitrakas AG, Kalamida D, Giatromanolaki A, et al. Autophagic flux response and glioblastoma sensitivity to radiation. Cancer Biol Med. 2018;15(3):260–274. doi: 10.20892/j.issn.2095-3941.2017.0173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhuang W, Li B, Long L, et al. Knockdown of the DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit radiosensitizes glioma-initiating cells by inducing autophagy. Brain Res. 2011;1371:7–15. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Liu Y, Shen Y, Sun T, et al. Mechanisms regulating radiosensitivity of glioma stem cells. Neoplasma. 2017;64(5):655–665. doi: 10.4149/neo_2017_502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Woo Y, Lee HJ, Jung YM, et al. mTOR-mediated antioxidant activation in solid tumor Radioresistance. J Oncol. 2019;2019:5956867. doi: 10.1155/2019/5956867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Beier D, Schulz JB, Beier CP. Chemoresistance of glioblastoma cancer stem cells--much more complex than expected. Mol Cancer. 2011;10:128. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-10-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ropolo M, Daga A, Griffero F, et al. Comparative analysis of DNA repair in stem and nonstem glioma cell cultures. Mol Cancer Res. 2009;7(3):383–392. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Stupp R, Hegi ME, Mason WP, et al. Effects of radiotherapy with concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide versus radiotherapy alone on survival in glioblastoma in a randomised phase III study: 5-year analysis of the EORTC-NCIC trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(5):459–466. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70025-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hegi ME, Diserens AC, Gorlia T, et al. MGMT gene silencing and benefit from temozolomide in glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(10):997–1003. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chinot OL, Barrie M, Fuentes S, et al. Correlation between O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase and survival in inoperable newly diagnosed glioblastoma patients treated with neoadjuvant temozolomide. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(12):1470–1475. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.4807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Beier D, Rohrl S, Pillai DR, et al. Temozolomide preferentially depletes cancer stem cells in glioblastoma. Cancer Res. 2008;68(14):5706–5715. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Liu G, Yuan X, Zeng Z, et al. Analysis of gene expression and chemoresistance of CD133+ cancer stem cells in glioblastoma. Mol Cancer. 2006;5:67. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-5-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pistollato F, Abbadi S, Rampazzo E, et al. Intratumoral hypoxic gradient drives stem cells distribution and MGMT expression in glioblastoma. Stem Cells. 2010;28(5):851–862. doi: 10.1002/stem.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Auffinger B, Tobias AL, Han Y, et al. Conversion of differentiated cancer cells into cancer stem-like cells in a glioblastoma model after primary chemotherapy. Cell Death Differ. 2014;21(7):1119–1131. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2014.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Anna Ciechomska I, Kocyk M, Kaminska B. Glioblastoma stem-like cells–isolation, biology and mechanisms of chemotherapy resistance. Curr Signal Transduct Ther. 2013;8(3):256–267. doi: 10.2174/1574362409666140206223501. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chua C, Zaiden N, Chong KH, et al. Characterization of a side population of astrocytoma cells in response to temozolomide. J Neurosurg. 2008;109(5):856–866. doi: 10.3171/JNS/2008/109/11/0856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nakai E, Park K, Yawata T, et al. Enhanced MDR1 expression and chemoresistance of cancer stem cells derived from glioblastoma. Cancer Investig. 2009;27(9):901–908. doi: 10.3109/07357900801946679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yamada K, Tso J, Ye F, et al. Essential gene pathways for glioblastoma stem cells: clinical implications for prevention of tumor recurrence. Cancers. 2011;3(2):1975–1995. doi: 10.3390/cancers3021975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Schaich M, Kestel L, Pfirrmann M, et al. A MDR1 (ABCB1) gene single nucleotide polymorphism predicts outcome of temozolomide treatment in glioblastoma patients. Ann Oncol. 2009;20(1):175–181. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bleau AM, Hambardzumyan D, Ozawa T, et al. PTEN/PI3K/Akt pathway regulates the side population phenotype and ABCG2 activity in glioma tumor stem-like cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4(3):226–235. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Martin V, Sanchez-Sanchez AM, Herrera F, et al. Melatonin-induced methylation of the ABCG2/BCRP promoter as a novel mechanism to overcome multidrug resistance in brain tumour stem cells. Br J Cancer. 2013;108(10):2005–2012. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tivnan A, Zakaria Z, O'Leary C, et al. Inhibition of multidrug resistance protein 1 (MRP1) improves chemotherapy drug response in primary and recurrent glioblastoma multiforme. Front Neurosci. 2015;9:218. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2015.00218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hirose Y, Berger MS, Pieper RO. Abrogation of the Chk1-mediated G (2) checkpoint pathway potentiates temozolomide-induced toxicity in a p53-independent manner in human glioblastoma cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61(15):5843–5849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mhaidat NM, Zhang XD, Allen J, et al. Temozolomide induces senescence but not apoptosis in human melanoma cells. Br J Cancer. 2007;97(9):1225–1233. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hsieh A, Ellsworth R, Hsieh D. Hedgehog/GLI1 regulates IGF dependent malignant behaviors in glioma stem cells. J Cell Physiol. 2011;226(4):1118–1127. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Eramo A, Ricci-Vitiani L, Zeuner A, et al. Chemotherapy resistance of glioblastoma stem cells. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13(7):1238–1241. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kanzawa T, Germano IM, Komata T, et al. Role of autophagy in temozolomide-induced cytotoxicity for malignant glioma cells. Cell Death Differ. 2004;11(4):448–457. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Yan Y, Xu Z, Dai S, et al. Targeting autophagy to sensitive glioma to temozolomide treatment. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2016;35:23. doi: 10.1186/s13046-016-0303-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]