Abstract

Effective delivery to the brain limits the development of novel glioblastoma therapies. Here, we introduce conjugation between platinum(IV) prodrugs of cisplatin and perfluoroaryl peptide macrocycles to increase brain uptake. We demonstrate that one such conjugate shows efficacy against glioma stem-like cells. We investigate the pharmacokinetics of this conjugate in mice and show that the amount of platinum in the brain after treatment with the conjugate is 15-fold greater than with cisplatin after 5 h.

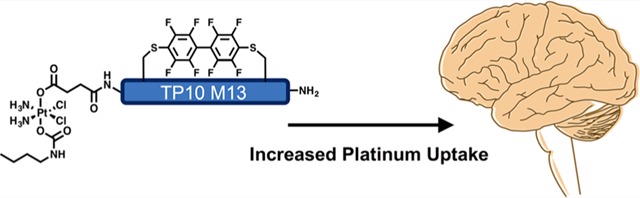

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Glioblastoma (GBM) is the most common primary malignant brain tumor. Even with the current standard of care, which involves maximal safe surgical resection followed by radiation concurrent with temozolomide, the median survival from time of diagnosis is fifteen months.1,21 Radical resection of the primary mass is not curative because of infiltrating tumor cells present throughout the whole brain. These infiltrating cells enable recurrence of the disease.2 Although many experimental drugs have been tested in clinical trials for GBM over the past few decades, none have changed disease progression in a meaningful way. One limitation in the development of new drugs is poor drug delivery across the blood–brain tumor barrier (BBTB).3–5

Transition-metal complexes have been of significant interest both for their anticancer activity and their luminescent properties.6–10 Notably, platinum-based chemotherapeutics such as cisplatin, carboplatin, and oxaliplatin have widespread clinical use for the treatment of malignancies.11 Cisplatin, for example, contains a square-planar platinum(II) center with two ammonia and two chloride ligands. The mechanism of action for cisplatin involves exchange of one of the chloride ligands with water, followed by preferential platination of the nucleophilic N7 atom of a purine nucleobase. Another ligand substitution then occurs with a nearby guanine base forming a DNA cross-link.11,12 The cells are arrested at the G2/M transition of the cell cycle in an attempt to repair the DNA lesion. If DNA repair is unsuccessful, the cells initiate apoptosis. Platinum-based agents also react with off-target nucleophiles, which can lead to significant toxic side effects, such as nephrotoxicity.13

One solution to mitigate off-target toxicity and improve the therapeutic index of Pt(II) chemotherapeutics is to administer them as Pt(IV) prodrugs. The Pt(II) center of cisplatin is oxidized to Pt(IV) upon addition of two axial ligands. Following internalization into cells, the Pt(IV) prodrug is reduced and enables the in situ generation of the native Pt(II) species inside a cancer cell. The oxidative addition of two ligands to Pt(II) complexes makes the resulting Pt(IV) complexes much more inert to ligand substitution than the corresponding Pt(II) complex and consequently improves the efficiency of delivering platinum to tumor cells by reducing off-target platinum sequestration and deactivation. Unfortunately, premature reduction in the bloodstream often limits the clinical utility of Pt(IV) prodrugs. The serum stability of Pt(IV) prodrugs has been increased by modifying the axial ligands to have affinity for human serum albumin.14 In this same study, Pt(IV) prodrugs with shorter alkyl ligands had lower efficacy.

Bioactive functional groups can be appended to the Pt(IV) center through the axial ligands.15–19 For example, the Pt(IV) prodrug can be functionalized symmetrically with ligands containing carboxylic acid groups. These functionalities can then be used to covalently attach peptides that improve cellular uptake or target the drug to a particular cell type.16,17 Peptides have also been connected to other transition-metal complexes such as those of iridium(III) to serve as imaging probes for specific cell surface receptors.20–22

For recurrent GBM, carboplatin has been a part of several clinical trials either as a single-agent or in combination with other chemotherapies, affording little improvement in disease prognosis.23–25 We propose that the inability to cross the BBTB may be one reason for the limited efficacy of platinum(II) therapeutics against GBM. To address this challenge, we prepared conjugates between Pt(IV) prodrugs and perfluoroaryl macrocyclic peptides. Perfluoroaryl macrocyclic peptides have increased uptake into brain endothelial cells, increased stability in mouse serum, and can enhance the delivery of a small molecule organic dye across the blood–brain barrier.26 These studies suggest that macrocyclic peptides could potentially improve the delivery of Pt(IV) prodrugs to the brain.

Here, we report the synthesis of a Pt(IV) prodrug—perfluoroaryl macrocyclic peptide conjugate (PtIV-M13) with efficacy against glioma stem-like cells, improved serum stability, and improved brain uptake in vivo.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

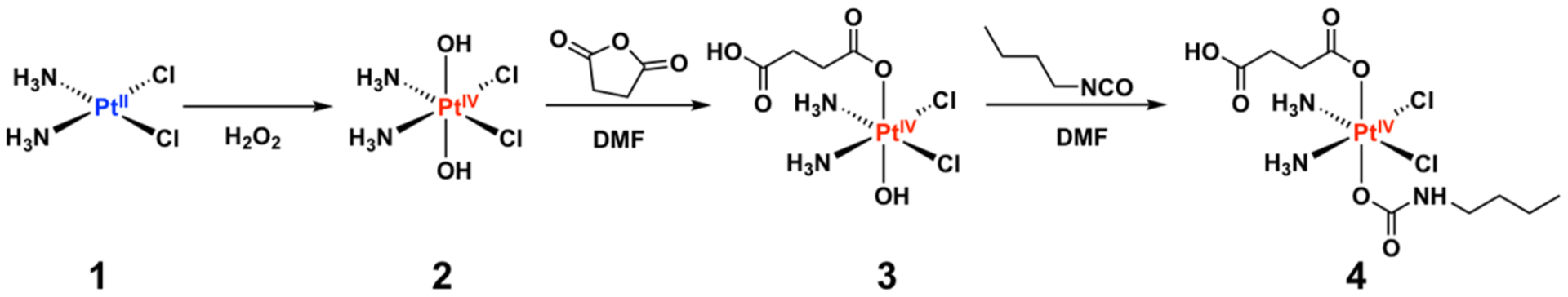

Pt(IV) prodrug synthesis involves first the oxidation of cisplatin (1) with hydrogen peroxide in water to form 2 (Scheme 1).27 Reaction with succinic anhydride in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) generates the monosuccinate Pt(IV) complex 3. 3 was allowed to react with n-butyl isocyanate to afford the final Pt(IV) prodrug 4, which has a single carboxylate for subsequent functionalization. The single carboxylate can be used for coupling to a peptide immobilized on a solid support. The Pt(IV) prodrug 4 was fully characterized by NMR spectroscopy, electrospray ionization mass spectrometry, and elemental analysis.

Scheme 1.

Synthetic Route for Preparing 4 from Cisplatin

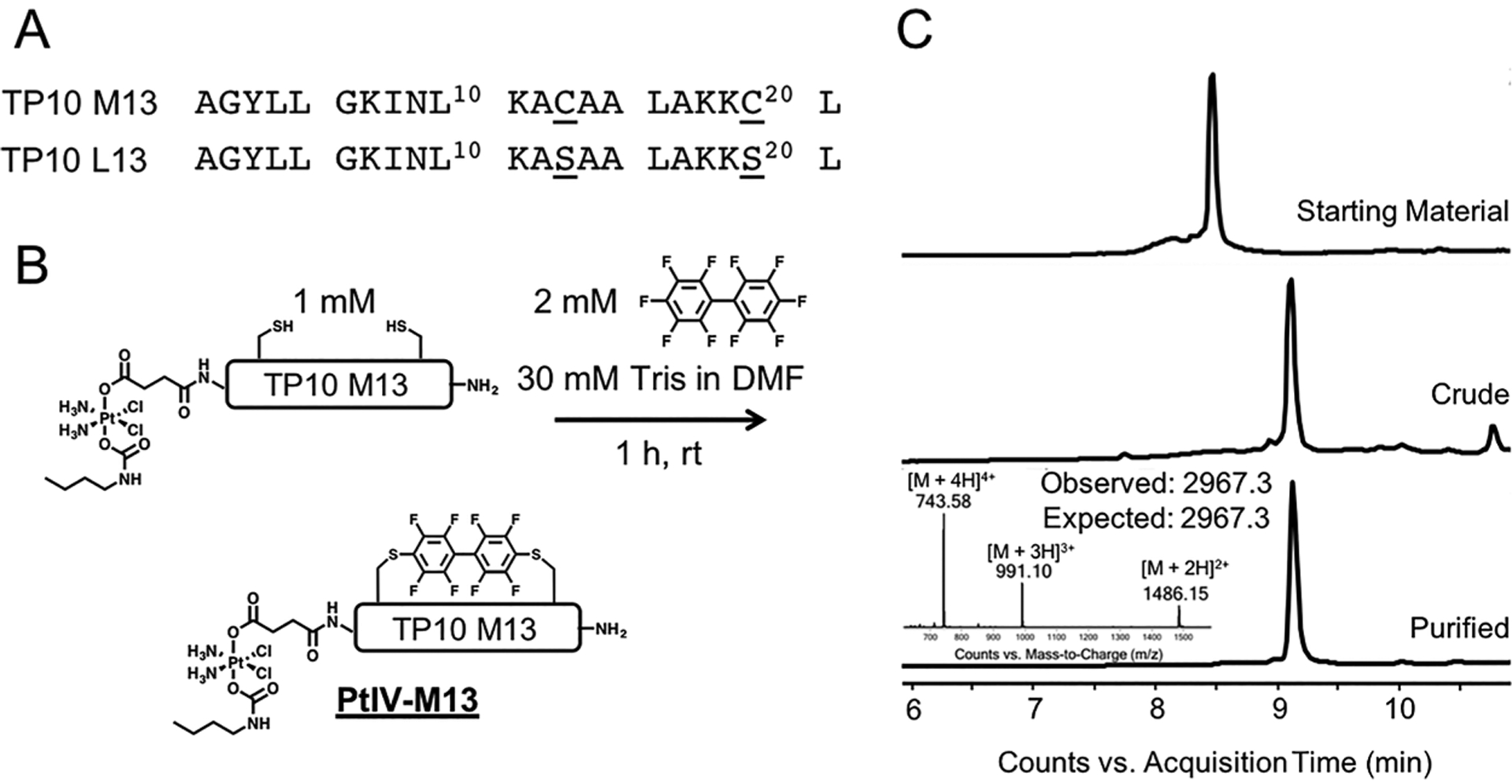

For conjugation, we chose the peptide TP10 M13, which exhibits the highest uptake into the brain.26 TP10 M13, a variant of TP10 containing two cysteine residues for cyclization, was prepared by automated fast-flow peptide synthesis.28 Additionally, a linear control sequence (TP10 L13) was synthesized in which serine was substituted for cysteine (Figure 1A). Prodrug 4 was coupled to the N-terminus of each resin-bound peptide with 0.4 M 1-[bis(dimethylamino)methylene]-1H-1,2,3-triazolo[4,5-b]-pyridinium 3-oxid hexafluorophosphate (HATU) and N,N-diisopropylethylamine in dimethylformamide. The prodrug-peptide conjugates were cleaved from the resin with trifluoro-acetic acid (TFA) and purified by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC). Next, the cysteine residues of the prodrug-peptide conjugate were cyclized using decafluorobiphenyl. The product (PtIV-M13) was characterized by liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS) (Figure 1C) and was found to be 95.7% pure by analytical HPLC. No reduction of the prodrug was observed during the perfluoroaryl cyclization reaction.

Figure 1.

Pt(IV)-prodrug peptides undergo efficient cysteine arylation. (A) Amino acid sequences of TP10 M13 and the linear control TP10 L13. (B) Perfluoroaryl cyclization of Pt(IV)-prodrug functionalized peptide. Incubating the precyclized, prodrug-functionalized TP10 M13 peptide (containing two thiols) at a concentration of 1 mM with 2 mM decafluorobiphenyl in the presence of base for 1 h yields the macrocyclic PtIV-M13 conjugate. (C) LC–MS analysis of the starting material, crude reaction, and purified material after RP-HPLC. All chromatograms are total ion currents. The observed peaks in the mass spectrum of the final conjugate are consistent with the values calculated for the desired conjugate containing an intact Pt(IV) prodrug.

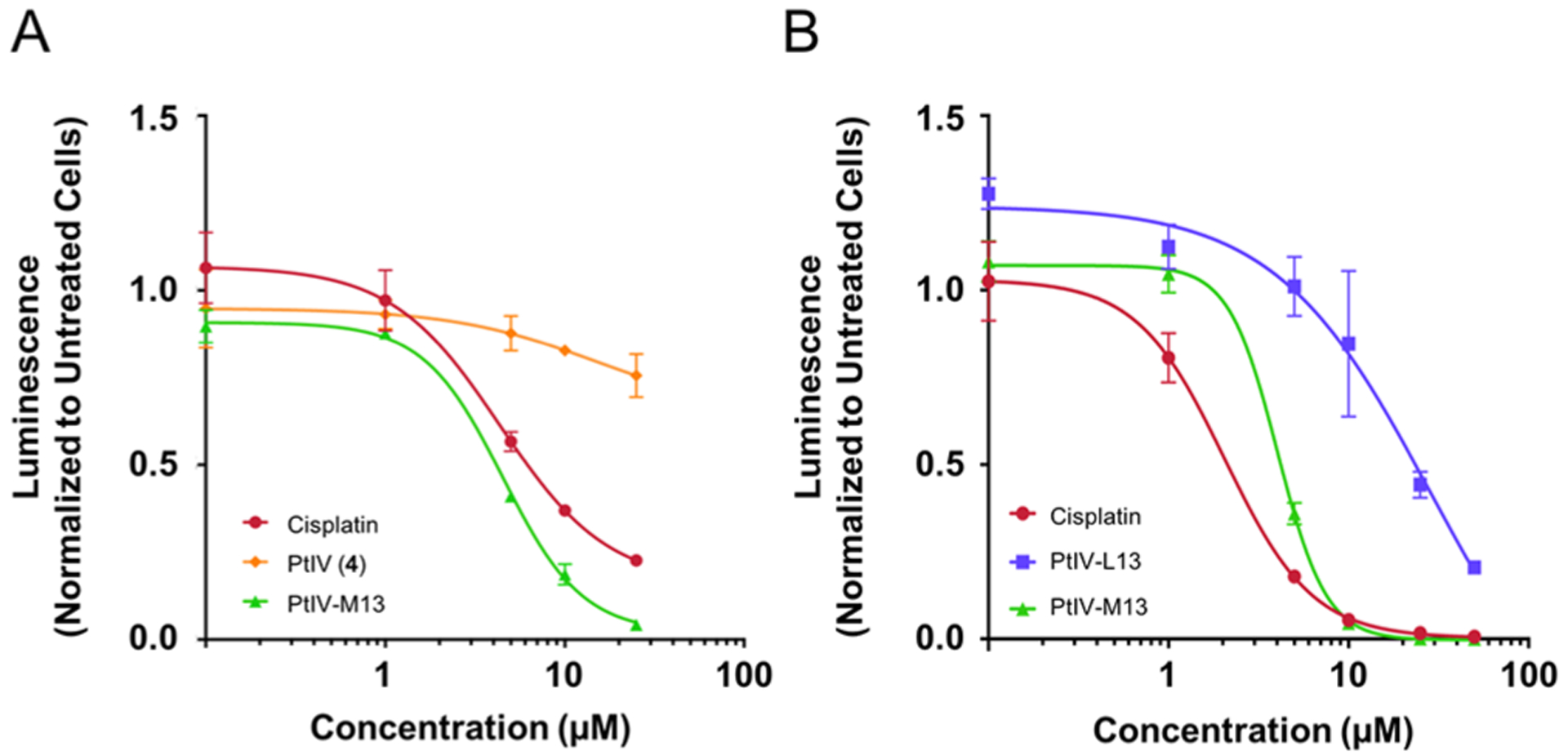

The cytotoxicity of the PtIV-M13 conjugate was evaluated against glioma stem-like cells (GSCs).29,30 To test the in vitro efficacy of the conjugate, G9 neurospheres were treated with PtIV-M13, prodrug 4, or cisplatin for 80 h. After treatment, the potency of the compounds was assessed by the CellTiter-Glo luminescent cell viability assay (Figure 2A). The assay involves lysis of the cells and quantitation of the amount of ATP present, which is directly proportional to the number of living cells in culture. The IC50 of PtIV-M13 against the G9 cells was determined to be ~5 μM, a value similar to that of cisplatin (IC50 = 4 μM). Under the same conditions, prodrug 4 was not active, presumably due to its inability to permeate the plasma membrane (Figure 2A). Although the mechanism of cellular death with PtIV-M13 was not investigated, these data suggest that the cytotoxicity is comparable to that of cisplatin.

Figure 2.

Peptide macrocycle PtIV-M13 has similar efficacy to cisplatin against glioma stem-like cells. (A) G9 neurospheres were treated with cisplatin, PtIV-M13, or prodrug 4 (PtIV). After 80 h, cell viability was measured by the CellTiter Glo assay. The data are shown in terms of luminescence normalized to untreated cells. The error bars are the standard deviation of three replicates. (B) G30 neurospheres were treated with cisplatin, PtIV-M13, or the linear control PtIV-L13. After 72 h, cell viability was measured by the CellTiter Glo assay. The data are shown in terms of luminescence normalized to untreated cells. The error bars are the standard deviation of three replicates.

Next, we performed a similar experiment but with conditions that may translate to future in vivo studies. We switched to G30 cells stably transfected with a luciferase construct that allows for luminescence as a read-out of tumor volume in vivo. We also added the linear control conjugate, PtIV-L13. Given that we have previously shown that the perfluoroaryl macrocycle is critical for crossing the blood–brain barrier, for in vivo applications, we included a linear control conjugate in which a peptide is attached to the prodrug without a perfluoroaryl cycle. In G30 GSCs, the PtIV-M13 conjugate had similar potency (IC50) of 4 μM and cisplatin had an IC50 of 2 μM. The linear control conjugate PtIV-L13 was not as potent, with an IC50 of 29 μM, suggesting that the perfluoroaryl macrocycle helps improve the potency of the prodrug-peptide conjugate (Figure 2B).

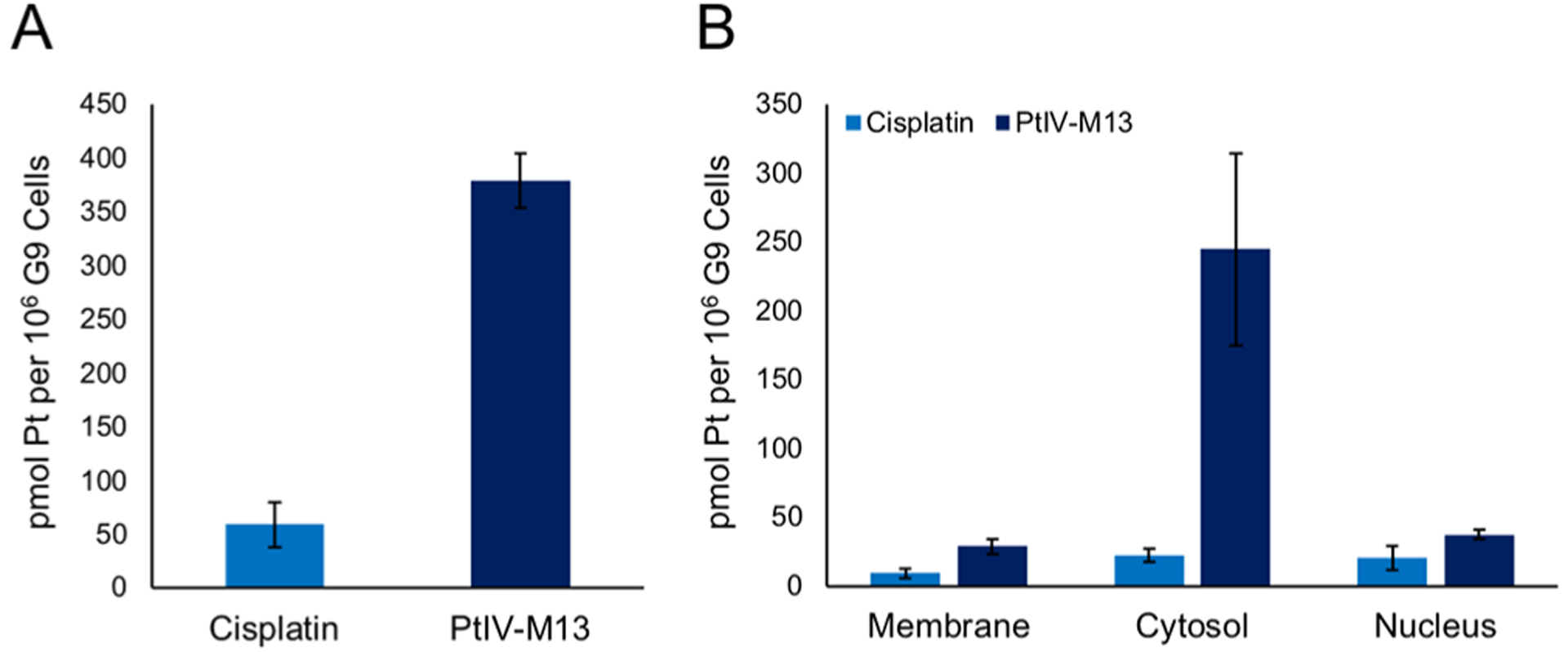

To further evaluate the properties of the conjugate in vitro, we investigated the cellular uptake and cellular localization of PtIV-M13. G9 GSCs were treated with a 5 μM solution of cisplatin or the PtIV-M13 conjugate for 5 h. The whole cell concentration of platinum was then evaluated by graphite furnace atomic absorption spectroscopy (GFAAS). Under these conditions, the amount of platinum in the cells after treatment with the PtIV-M13 conjugate was six times greater than that following cisplatin treatment, suggesting that the PtIV-M13 conjugate promotes increased uptake of the Pt(IV) prodrug into cells (Figure 3A). The subcellular distribution was examined by fractionating the different cellular components. Most of the platinum from cells treated with PtIV-M13 is present in the cytosol. The amount of nuclear platinum is relatively similar between cells treated with the PtIV-M13 conjugate and cisplatin (Figure 3B). Given that the mechanism of action of the prodrug involves intracellular reduction, the platinum quantified in this assay is most likely a mixture of conjugate, free cisplatin, and adducts with cellular components such as nuclear DNA.

Figure 3.

PtIV-M13 conjugate increases the uptake of platinum into cells compared with cisplatin. (A) G9 GSCs were treated with a 5 μM solution of cisplatin or the PtIV-M13 conjugate for 5 h. The whole cell concentration of platinum was then evaluated by GFAAS. The error bars represent the standard deviation of three replicate wells. (B) G9 GSCs were treated with a 5 μM solution of cisplatin or the PtIV-M13 conjugate for 5 h. The cells were fractionated into different components, and the amount of platinum was quantified by GFAAS. The error bars represent the standard deviation of three different wells treated with the compound.

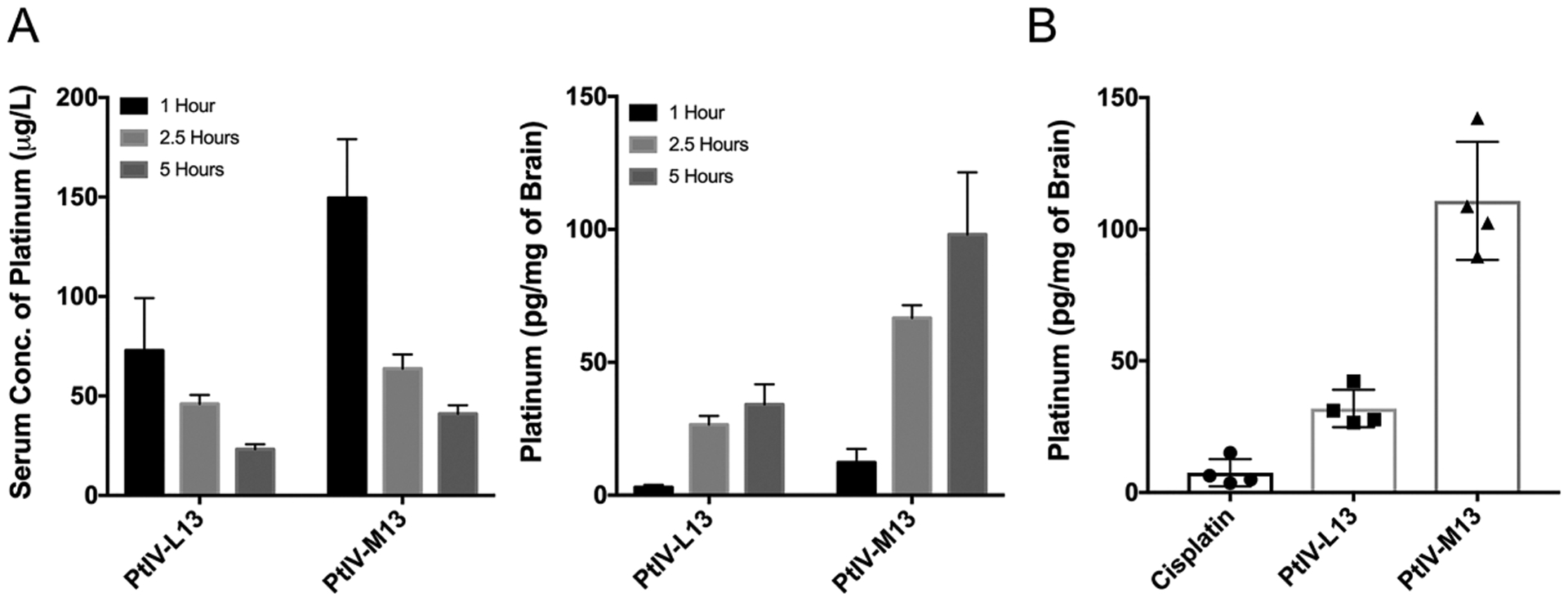

Finally, to evaluate PtIV-M13 in vivo, we performed pharmacokinetic and biodistribution studies in healthy mice. For pharmacokinetics, 100 μL of a 100 μM solution of PtIV-M13 or PtIV-L13 dissolved in saline (corresponding to a dose of ~2.5 mg/kg) were injected into the tail veins of mice. The brain and a blood sample were isolated at 1, 2.5, and 5 h. A portion of the brain was dissolved in nitric acid, and the amounts of platinum in the brain and serum were quantified by GFAAS. For both PtIV-M13 and PtIV-L13, the serum concentration decreased over time and the brain distribution increased over time (Figure 4A). Although the read-out is platinum, unbound platinum(II) has an initial half-life of around 30 min, suggesting that the majority of the quantified platinum in the serum comes from intact conjugates.31–33 Therefore, the results suggest that PtIV-M13 is more stable in serum. Additionally, mice treated with PtIV-M13 have more brain uptake of platinum than mice treated with the linear control.

Figure 4.

PtIV-M13 conjugate enhances uptake of platinum into the brain. (A) The left plot is the concentration of platinum in serum at 1, 2.5, and 5 h after treatment with either PtIV-M13 or the linear control PtIV-L13 (n = 3 animals for each time point). The error bars are the standard deviation from three different animals injected with the compound. The right plot is the brain concentration of platinum at 1, 2.5, and 5 h after treatment with either PtIV-M13 or the linear control PtIV-L13 (n = 3 animals for each time point). The error bars are the standard deviation from three different animals injected with the compound. (B) Concentration of platinum in the brains of mice 5 h after treatment with either PtIV-M13, PtIV-L13, or cisplatin (n = 4 animals for each treatment group). The results are significant with a p-value of less than 0.0001 by a One-Way ANOVA test. After treatment with PtIV-M13, the amount of platinum in the brain at 5 h is 15-fold greater than cisplatin.

To study the biodistribution, 100 μL of a 100 μM solution of PtIV-M13, PtIV-L13, or cisplatin dissolved in normal saline were injected into the tail veins of mice. After 5 h, the mice were sacrificed and the brain, heart, lungs, kidney, spleen, and liver were removed. The amount of platinum in each organ was measured by dissolving a portion of the respective organ in nitric acid and then quantifying the amount of platinum by GFAAS (Supporting Information). The brains of the mice treated with the PtIV-M13 conjugate exhibited a 15-fold increase in the amount of platinum (~110 pg/mg of brain) compared with cisplatin, indicating that attachment of a perfluoroaryl macrocyclic peptide is a valuable strategy for significantly increasing the amount of platinum that reaches the brain (Figure 4B).

Notably, the amount of platinum also increased in the spleen and liver after treatment with the conjugate (Figure S15). Future work will be necessary to understand the metabolism of these conjugates and any potential toxicity.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, the covalent attachment of a Pt(IV) prodrug to a brain-penetrant perfluoroaryl macrocyclic peptide increases the in vivo stability of the prodrug and enhances the uptake of platinum into the brain. The PtIV-M13 conjugate is the first compound to combine the benefits of oxidized Pt(IV) prodrugs and perfluoroaryl macrocyclic peptides. The observed cytotoxicity against glioma stem-like cells is promising, and future work will focus on whether conjugates of this nature are efficacious against GBM in vivo. We expect that this new approach will be of immediate utility to the chemotherapeutic drug development and oncology communities. Given the devastating nature of GBM, original approaches are needed to address treatment challenges and broaden the scope of available therapeutic agents. This work highlights the potential of Pt (IV)-perfluoroaryl macrocyclic peptide conjugates as a unique and efficient modality for GBM therapy.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Materials and Instrumentation.

H-Rink Amide-ChemMatrix resin was obtained from PCAS BioMatrix Inc. (St-Jean-sur-Richelieu, Quebec, Canada). 1-[Bis(dimethylamino)methylene]-1H-1,2,3-triazolo[4,5-b]pyridinium-3-oxid-hexafluorophosphate (HATU) and Fmoc-protected amino acids were purchased from Chem-Impex International (Wood Dale, IL). Peptide synthesis-grade N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF), CH2Cl2, diethyl ether, t-butanol, and HPLC-grade acetonitrile were obtained from VWR International (Radnor, PA). Decafluorobiphenyl was purchased from Oakwood Products, Inc. (Estill, SC). Glioma stem cell lines G9 and G30 were previously described. The neurobasal media and GlutaMax, B-27, EGF, and FGF supplements were all obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA). The G9 cells were transduced with copepod GFP using pCDH from Systems Biosciences (Mountain View, CA) and the G30 cells were transduced with firefly luciferase using LPP-hLUC from GeneCopoeia (Rockville, MD). The CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Cell Viability Assay was obtained from Promega (Madison, WI). Athymic mice were obtained from Envigo (South Easton, MA). All other reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), Strem (Newburyport, MA), or Alfa Aesar (Tewksbury, MA), water was deionized before use, and reactions were conducted in the open air on the benchtop. Deuterated solvents were purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories (Andover, MA). 1HNMR spectra were recorded on a Varian Inova 500 NMR spectrometer with an Oxford Instruments Ltd. superconducting magnet in the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Department of Chemistry Instrumentation Facility (MIT DCIF). Electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) of small molecules was performed on an Agilent Technologies 1100 series liquid chromatography/MS instrument. Graphite furnace atomic absorption spectroscopic (GFAAS) measurements were taken on a Perkin Elmer AAnalyst 600 spectrometer.

LC–MS Analysis.

LC–MS analysis was conducted on an Agilent 6520 ESI-Q-TOF mass spectrometer equipped with a C3 Zorbax column (300SB C3, 2.1 × 150 mm, 5 μm) for characterization of all peptides and peptide-prodrug conjugates. Mobile phases were: 0.1% formic acid in water (solvent A) and 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (solvent B). Method: 1% B from 0 to 2 min, linear ramp from 1% B to 61% B from 2 to 11 min, 61% B to 99% B from 11 to 12 min and finally 3 min of post-time at 1% B for equilibration, flow rate: 0.8 mL/min.

All data were processed by using the Agilent MassHunter software package. Y-axis in all chromatograms depicted represents total ion current (TIC) unless otherwise noted.

Analytical RP-HPLC Analysis.

RP-HPLC analysis was conducted on an Agilent 1260 HPLC equipped with a C3 Zorbax column (300SB C3, 2.1 × 150 mm, 5 μm) for characterization of the peptide-prodrug conjugate. Mobile phases were 0.1% TFA in water (solvent A) and 0.08% TFA in acetonitrile (solvent B). Method: 5% B from 0 to 3 min, linear ramp from 5% B to 65% B from 3 to 63 min, and finally 3 min of 65% B flow rate: 0.4 mL/min.

All data were processed by using the Agilent software package. The peaks at 214 nm were integrated by setting a manual baseline, and the percent purity is the area of the desired peak over the total integrated area *100.

cis,cis,trans-[Pt(NH3)2Cl2(OH)2] (2).

Synthesized as previously described.27

cis,cis,trans-[Pt(NH3)2Cl2(O2CCH2CH2COOH)(OH)] (3).

Synthesized by modifying a published procedure.34 cis,cis,trans-[Pt- (NH3)2Cl2(OH)2] (167 mg, 0.50 mmol) was stirred in anhydrous DMSO (10 mL) in a glove box. Succinic anhydride (50 mg, 0.50 mmol) was added to the above suspension in one portion. The reaction was stirred at room temperature in the dark for 24 h, after which a small amount of insoluble yellow material remained. The insoluble material was removed by suction filtration and washed with acetone (20 mL). The filtrate was passed through a 0.2 μm PTFE syringe filter and further diluted with acetone (900 mL). The solution was stored in the dark at 5 °C for 12 h and then at −40 °C for 12 h. The fine white particles were collected by centrifugation (4500 rpm, 5 min). The solid was suspended in cold acetone (20 mL) and centrifuged (4500 rpm, 5 min). This process was repeated twice. The solid was dried under vacuum to afford a white solid (85 mg, 39% yield). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 6.47 (br, 1H), 6.14–5.71 (m, 6H), 2.44–2.34 (m, 4H). One of the hydroxyl groups was not observable in the 1H NMR spectrum. MS (ESI−): m/z calcd for [M − H]−, 432.0; found, 432.7.

cis,cis,trans-[Pt(NH3)2Cl2(O2CCH2CH2COOH)(n-butyl Carba-mate)] (4).

To a solution of cis , cis , t r a n s - [P t - (NH3)2Cl2(O2CCH2CH2COOH) (OH)] (60.0 mg, 0.138 mmol) in anhydrous DMF (1.5 mL) was added n-butyl isocyanate (27.4 mg, 31.1 μL, 0.276 mmol). The reaction was stirred in the dark at room temperature for 24 h. The insoluble material was removed by passage through a 0.2 μm PTFE syringe filter. The filtrate was layered with Et2O (20 mL) in a test tube at room temperature. After four days, a pale-yellow oil formed at the bottom of the tube. The solvent was decanted. The oil was dissolved in DMF (1.0 mL), and this solution was added dropwise to Et2O (50 mL). The solid was isolated by centrifugation (4500 rpm, 5 min). The precipitate was suspended in Et2O (50 mL) and centrifuged (4500 rpm, 5 min). This process was repeated twice. The solid was dissolved in water and lyophilized to give a fluffy white solid (31.0 mg, 42% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 6.56 (br, exchangeable protons, 8H), 2.90 (q, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H), 2.49–2.41 (m, 2H), 2.35 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H), 1.34 (quintet, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 1.25 (sextet, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H), 0.85 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 179.8, 174.1, 163.9, 40.7, 32.0, 30.7, 30.3, 19.6, 13.8. 195Pt NMR (108 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 1254 (s), 1224 (s). The presence of two signals in the 195Pt NMR spectrum was previously observed for structurally analogous compounds.14 The two signals may correspond to two conformational isomers due to the slow rotation around the amide bond. MS (ESI+): m/z calcd for [M + H]+, 533.1; found, 533.0. MS (ESI−): m/z calcd for [M − H]−, 531.0; found, 531.7. Anal. Calcd for C9H21Cl2N3O6Pt·(H2O)3: C, 18.41; H, 4.63; N, 7.15%. Found: C, 18.84; H, 4.19; N, 7.28%.

PtIV-L13 and PtIV-M13 Synthesis and Prodrug Conjugation.

Peptides were synthesized on a 0.1 mmol scale using an automated flow peptide synthesizer.28 After completion of the synthesis, the resins were washed three times with DCM and dried under vacuum. A 100 mg portion of the peptidyl resin was transferred to a 3 mL Torviq fritted syringe and subsequently swelled in DMF. Prodrug 4 (50 mg, 94 μmol, ~ 4 equivalents with respect to the theoretical loading of resin) was dissolved in 625 μL of 0.4 M HATU in a scintillation vial, and 50 μL of diisopropylethylamine was added to the vial. The vial was briefly sonicated and the coupling solution was transferred to the fritted syringe containing the peptidyl resin, after draining the DMF from the resin. The syringe was capped and mixed on a nutating mixer for 1 h. Following the 1 h incubation, the coupling solution was removed from the resin and the resin was washed 5 times with DMF, 5 times with DCM, and dried under vacuum.

PtIV-L13 and PtIV-M13 Peptide Cleavage and Deprotection.

Each peptide was subjected to simultaneous global side-chain deprotection and cleavage from resin by treatment with 4 mL of 95% (v/v) TFA, 2.5% (v/v) water, and 2.5% (v/v) triisopropylsilane (TIPS) for 2 h at room temperature. Note: with PtIV-L13, some reduction of the prodrug was observed upon cleavage. We hypothesize this occurrence to be due to TIPS in the cleavage cocktail with a peptide having fewer trityl-protected residues than PtIV-M13. For general use, researchers may want to omit TIPS from their cleavage cocktail. After cleavage, the TFA was evaporated by bubbling N2 through the mixture until only an oil and the resin remained. Then, ~35 mL of cold ether was added to precipitate and wash the peptide (chilled at −80 °C). The crude product and resin were pelleted by centrifugation for 3 min at 4000 rpm and the ether was decanted. The ether precipitation and centrifugation steps were repeated two more times. After the third wash, the pellet was redissolved in 50% water and 50% acetonitrile containing 0.1% TFA and the resulting solution lyophilized.

PtIV-L13 and Precyclization PtIV-M13 Purification.

After lyophilization, the peptides were redissolved in water and acetonitrile containing 0.1% TFA, filtered through a 0.22 μm, nylon filter, and purified by mass-directed semi-preparative reversed-phase HPLC. Solvent A was water containing 0.1% TFA, and solvent B was acetonitrile containing 0.1% TFA. A linear gradient that changed at a rate of 0.5%/min was used from 15% solvent B to 55% solvent B over 80 min. The peptides were purified on an Agilent Zorbax SB C3 column: 9.4 × 250 mm, 5 μm. With the use of mass spectrometric data about each fraction from the instrument, only pure fractions were pooled and lyophilized. The purity of the fraction pool was confirmed by LC–MS (Figures S5, S6).

PtIV-M13 Macrocyclization and Purification.

The purified, precyclization PtIV-M13 peptide was dissolved in DMF, and stock solutions of decafluorobiphenyl in DMF and Tris in DMF were added such that the final concentrations in the reaction vessel were 1 mM of peptide, 2 mM decafluorobiphenyl, and 30 mM Tris. After 1 h, the reaction was quenched by diluting the reaction by a factor of ten with 85:15 water/acetonitrile containing 2% TFA. The crude reaction product was purified by mass-directed semi-preparative reversed-phase HPLC (Agilent Zorbax SB C3 column: 9.4 × 250 mm, 5 μm). Solvent A was water containing 0.1% TFA, and solvent B was acetonitrile containing 0.1% TFA. A linear gradient that changed at a rate of 0.5%/min was run from 20% B to 60% B. By using mass spectrometric data about each fraction from the instrument, the pure fractions were pooled and lyophilized. The purity of the fraction pool was confirmed by LC–MS and analytical HPLC (Figures S7, S8).

G9 Cytotoxicity Assay.

At 20 h before treatment, G9 cells were plated at a density of 10,000 cells per well in a 96-well plate (100 μL/well). Note: the cells must be incubated with Accutase prior to counting to disrupt the spheres and generate a single cell suspension. Stocks (2.5 mM) of PtIV-M13 and prodrug 4 were prepared in DMSO, and a 2.5 mM stock of cisplatin was prepared in PBS. The stock concentrations of the compounds were determined by GFAAS. Treatment media stocks were prepared by serial dilution with the supplemented neurobasal media such that there were treatment wells with concentrations of 150, 75, 30, 15, 3, and 0.3 μM. To treat the cells, 50 μL of each treatment medium stock were added to the overnight growth media, such that the final volume in the well was 150 μL and the final treatment concentrations were 50, 25, 10, 5, 1, and 0.1 μM respectively. Cells were incubated for 80 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2. At 80 h, the plate was removed from the incubator and the cells were allowed to equilibrate to room temperature. Then, 130 μL of CellTiter-Glo reagent was added to each well. The plate was incubated for 10 min away from light. After incubation, 10 μL from each well were transferred to a new plate and each well in the new plate was diluted with 90 μL of PBS. The luminescence was read on a Perkin Elmer 1450 MicroBeta TriLux Microplate Scintillation and Luminescence Counter. The luminescence of each sample was normalized to untreated control wells, and the data were plotted in GraphPad Prism.

G30 Cytotoxicity Assay.

For the G30 cytotoxicity assay, the conditions were identical to the G9 assay. The only differences were the following: G30 GSCs were used instead of G9 GSCs, a stock (2.5 mM) of PtIV-L13 in DMSO was used as a control, rather than prodrug 4, and finally, the total treatment time with compound was 72 h instead of 80 h.

Whole Cell Uptake Assay.

At 12 h before treatment, G9 cells were plated at a density of 300,000 cells per well in a 6-well plate (2.5 mL/well). Stocks (2.5 mM) of PtIV-M13 in DMSO and cisplatin in PBS were used to prepare 30 μM treatment solutions in supplemented neurobasal media, and 0.5 mL of treatment medium were added to each well such that the final treatment concentration was 5 μM. The cells were incubated for 6 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Each well of cells was transferred to its own 15 mL conical tube and centrifuged at 500 rcf for 3 min. The media were aspirated, and the cells were treated with Accutase (1 mL) for 10 min at room temperature. After quenching the Accutase with 4 mL of PBS, the cell number was counted with a hemocytometer. The cells were centrifuged, the PBS aspirated, and then, the cells were resuspended in 5 mL of PBS. This PBS wash was repeated one additional time, and then, the amount of platinum was quantified by GFAAS.

Cellular Distribution Assay.

At 12 h before treatment, G9 cells were plated at a density of 370,000 cells per well in a 6-well plate (2 mL/well). Stocks (2.5 mM) of PtIV-M13 in DMSO and cisplatin in PBS were used to prepare 15 μM treatment solutions in supplemented neurobasal media, and 1 mL of treatment medium was added to each well for a final treatment concentration of 5 μM. The cells were incubated for 6 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Each well of cells was transferred to its own 15 mL conical tube and centrifuged at 500 rcf for 3 min. The medium was aspirated, and the cells were treated with Accutase (1 mL) for 10 min at room temperature. After quenching the Accutase with 4 mL of PBS, the cells were counted with a hemocytometer. The cells were centrifuged, the PBS aspirated, and then, the cells were resuspended in 5 mL of PBS. This PBS wash was repeated one additional time, and then, the cytoplasm, nucleus, and membrane fractions were isolated using the Thermo Scientific NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction kit. The platinum content in the cytoplasm, nucleus, and membrane was analyzed by GFAAS.

In Vivo Pharmacokinetics.

PtIV-M13 and PtIV-L13 powders were dissolved to a final concentration of 10 mM in DMSO (determined by GFAAS). Each peptide was then diluted to a concentration of 100 μM in 0.9% sodium chloride (v/v) irrigation solution. A 100 μL dose of each peptide solution was administered intravenously via the tail vein into healthy 5–6-week old atyhmic, female nude mice. At 1, 2.5, and 5 h, the mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation, blood was collected periorbitally, and the brains were excised and frozen on dry ice immediately. The blood samples were allowed to coagulate at room temperature for 30 to 60 min. The blood was subsequently spun at 2,500 rcf for 10 min at 4 °C. The serum was collected with a pipette and frozen in a −20 °C freezer for storage. The concentration of platinum in each serum sample was determined by GFAAS. Additionally, a portion of each brain was dissolved in 500 μL of nitric acid and the amount of platinum was quantified by GFAAS.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants CA034992 to S.J.L., CA034992, AG045144, CA211184 toÖ.H.Y, and GM110535 to B.L.P., as well as the Sontag Foundation Distinguished Scientist Award to B.L.P. C.M.F. is supported by the David H. Koch Graduate Fellowship Fund and by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under award number F30HD093358. J.M.W. is supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship under grant no. 1122374. C-F.C. is supported by the Department of Defense and the Brigham Research Institute. N. vS. is supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Research Fellowship grant no. 400975596. Y.-C.L. is supported by the Deutsch Forschungsgemeinschaft (LE 4224/1–1). We thank Rebecca Holden and Nicholas Truex for assistance with characterization of the peptide-prodrug conjugate, Fang Wang for assistance with synthesis and characterization of the prodrug, Rachel Zane for cryosectioning the livers, and Andrei Loas for helpful discussions and comments during manuscript preparation.

ABBREVIATIONS

- GBM

glioblastoma

- BBTB

blood–brain tumor barrier

- HATU

1-[bis(dimethylamino)methylene]-1H-1,2,3-triazolo-[4,5-b]pyridinium 3-oxid hexafluorophosphate

- GSC

glioma stem-like cells

- TIC

total-ion current

- GFAAS

graphite furnace atomic absorption spectroscopy

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00022.

Prodrug and conjugate characterization data and supplemental figures (PDF)

Molecular formula strings of the target compounds (CSV)

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00022

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Contributor Information

Wen Zhou, Department of Chemistry and The Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139, United States.

Choi-Fong Cho, Harvey Cushing Neuro-Oncology Laboratories, Department of Neurosurgery, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts 02115, United States.

Niklas von Spreckelsen, Harvey Cushing Neuro-Oncology Laboratories, Department of Neurosurgery, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts 02115, United States; Department of Neurosurgery, Center for Neurosurgery, Faculty of Medicine and University Hospital, University of Cologne, 50937 Cologne, Germany.

Kathryn T. Hutchinson, Harvey Cushing Neuro-Oncology Laboratories, Department of Neurosurgery, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts 02115, United States

Yen-Chun Lee, Department of Chemistry, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139, United States.

Omer H. Yilmaz, The Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139, United States

Stephen J. Lippard, Department of Chemistry, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139, United States.

Bradley L. Pentelute, Department of Chemistry and The Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139, United States.

REFERENCES

- (1).Stupp R; Mason WP; van den Bent MJ; Weller M; Fisher B; Taphoorn MJB; Belanger K; Brandes AA; Marosi C; Bogdahn U; Curschmann J; Janzer RC; Ludwin SK; Gorlia T; Allgeier A; Lacombe D; Cairncross JG; Eisenhauer E; Mirimanoff RO Radiotherapy plus Concomitant and Adjuvant Temozolomide for Glioblastoma. N. Engl. J. Med 2005, 352, 987–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Wong ET; Hess KR; Gleason MJ; Jaeckle KA; Kyritsis AP; Prados MD; Levin VA; Yung WK Outcomes and Prognostic Factors in Recurrent Glioma Patients Enrolled Onto Phase II Clinical Trials. J. Clin. Oncol 1999, 17, 2572–2578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Sarin H; Kanevsky AS; Wu H; Brimacombe KR; Fung SH; Sousa AA; Auh S; Wilson CM; Sharma K; Aronova MA; Leapman RD; Griffiths GL; Hall MD Effective Transvascular Delivery of Nanoparticles across the Blood-Brain Tumor Barrier into Malignant Glioma Cells. J. Transl. Med 2008, 6, 80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).van Tellingen O; Yetkin-Arik B; de Gooijer MC; Wesseling P; Wurdinger T; de Vries HE Overcoming the Blood–Brain Tumor Barrier for Effective Glioblastoma Treatment. Drug Resist. Updates 2015, 19, 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Neuwelt E; Abbott NJ; Abrey L; Banks WA; Blakley B; Davis T; Engelhardt B; Grammas P; Nedergaard M; Nutt J; Pardridge W; Rosenberg GA; Smith Q; Drewes LR Strategies to Advance Translational Research into Brain Barriers. Lancet Neurol. 2008, 7, 84–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Ndagi U; Mhlongo N; Soliman M Metal Complexes in Cancer Therapy - an Update from Drug Design Perspective. Drug Des. Dev. Ther 2017, 11, 599–616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Khan T; Ahmad R; Azad I; Raza S; Joshi S; Khan AR Computer-Aided Drug Design and Virtual Screening of Targeted Combinatorial Libraries of Mixed-Ligand Transition Metal Complexes of 2-Butanone Thiosemicarbazone. Comput. Biol. Chem 2018, 75, 178–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Liang J-X; Zhong H-J; Yang G; Vellaisamy K; Ma D-L; Leung C-H Recent Development of Transition Metal Complexes with in Vivo Antitumor Activity. J. Inorg. Biochem 2017, 177, 276–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Baggaley E; Weinstein JA; Williams JAG Lighting the Way to See inside the Live Cell with Luminescent Transition Metal Complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev 2012, 256, 1762–1785. [Google Scholar]

- (10).Ma D-L; He H-Z; Leung K-H; Chan DS-H; Leung C-H Bioactive Luminescent Transition-Metal Complexes for Bimedical Applications. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2013, 52, 7666–7682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Wang D; Lippard SJ Cellular Processing of Platinum Anticancer Drugs. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 2005, 4, 307–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Blommaert FA; van Dijk-Knijnenburg HCM; Dijt FJ; den Engelse L; Baan RA; Berends F; Fichtinger-Schepman AMJ Formation of DNA Adducts by the Anticancer Drug Carboplatin: Different Nucleotide Sequence Preferences in Vitro and in Cells. Biochemistry 1995, 34, 8474–8480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Miller RP; Tadagavadi RK; Ramesh G; Reeves WB Mechanisms of Cisplatin Nephrotoxicity. Toxins 2010, 2, 2490–2518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Zheng Y-R; Suntharalingam K; Johnstone TC; Yoo H; Lin W; Brooks JG; Lippard SJ Pt(IV) Prodrugs Designed to Bind Non-Covalently to Human Serum Albumin for Drug Delivery. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 8790–8798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Dhar S; Gu FX; Langer R; Farokhzad OC; Lippard SJ Targeted Delivery of Cisplatin to Prostate Cancer Cells by Aptamer Functionalized Pt(IV) Prodrug-PLGA–PEG Nanoparticles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2008, 105, 17356–17361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Abramkin S; Valiahdi SM; Galanski M; Keppler N; Metzler-Nolte N; Keppler K Solid-Phase Synthesis of Oxaliplatin – TAT Peptide Bioconjugates. Dalton Trans. 2012, 41, 3001–3005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Mukhopadhyay S; Barnés CM; Haskel A; Short SM; Barnes KR; Lippard SJ Conjugated Platinum(IV)–Peptide Complexes for Targeting Angiogenic Tumor Vasculature. Bioconjugate Chem. 2008, 19, 39–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Wong DYQ; Yeo CHF; Ang WH Immuno-Chemotherapeutic Platinum(IV) Prodrugs of Cisplatin as Multimodal Anticancer Agents. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2014, 53, 6752–6756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Gaviglio L; Gross A; Metzler-Nolte N; Ravera M Synthesis and in Vitro Cytotoxicity of cis, cis ,trans - Diamminedichloridodisuccinatoplatinum(IV)–Peptide Bioconjugates. Metallomics 2012, 4, 260–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Kang T-S; Wang W; Zhong H-J; Dong Z-Z; Huang Q; Mok SWF; Leung C-H; Wong VKW; Ma D-L An Anti-Prostate Cancer Benzofuran-Conjugated Iridium(III) Complex as a Dual Inhibitor of STAT3 and NF-KB. Cancer Lett. 2017, 396, 76–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Vellaisamy K; Li G; Wang W; Leung C-H; Ma D-L A Long-Lived Peptide-Conjugated Iridium(III) Complex as a Luminescent Probe and Inhibitor of the Cell Migration Mediator, Formyl Peptide Receptor 2. Chem. Sci 2018, 9, 8171–8177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Lee S; Xie J; Chen X Peptide-Based Probes for Targeted Molecular Imaging. Biochemistry 2010, 49, 1364–1376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Yung WK; Mechtler L; Gleason MJ Intravenous Carboplatin for Recurrent Malignant Glioma: A Phase II Study. J. Clin. Oncol 1991, 9, 860–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Reardon DA; Desjardins A; Peters KB; Gururangan S; Sampson JH; McLendon RE; Herndon JE; Bulusu A; Threatt S; Friedman AH; Vredenburgh JJ; Friedman HS Phase II Study of Carboplatin, Irinotecan, and Bevacizumab for Bevacizumab Naïve, Recurrent Glioblastoma. J. Neurooncol 2012, 107, 155–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Francesconi AB; Dupre S; Matos M; Martin D; Hughes BG; Wyld DK; Lickliter JD Carboplatin and Etoposide Combined with Bevacizumab for the Treatment of Recurrent Glioblastoma Multiforme. J. Clin. Neurosci 2010, 17, 970–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Fadzen CM; Wolfe JM; Cho C-F; Chiocca EA; Lawler SE; Pentelute BL Perfluoroarene–Based Peptide Macrocycles to Enhance Penetration Across the Blood–Brain Barrier. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 15628–15631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Johnstone TC; Lippard SJ Reinterpretation of the Vibrational Spectroscopy of the Medicinal Bioinorganic Synthon c,c,t- [Pt(NH3)2Cl2(OH)2]. JBIC J. Biol. Inorg. Chem 2014, 19, 667–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Mijalis AJ; Thomas DA; Simon MD; Adamo A; Beaumont R; Jensen KF; Pentelute BL A Fully Automated Flow-Based Approach for Accelerated Peptide Synthesis. Nat. Chem. Biol 2017, 13, 464–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Berger G; Grauwet K; Zhang H; Hussey AM; Nowicki MO; Wang DI; Chiocca EA; Lawler SE; Lippard SJ Anticancer Activity of Osmium(VI) Nitrido Complexes in Patient-Derived Glioblastoma Initiating Cells and in Vivo Mouse Models. Cancer Lett. 2018, 416, 138–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Williams SP; Nowicki MO; Liu F; Press R; Godlewski J; Abdel-Rasoul M; Kaur B; Fernandez SA; Chiocca EA; Lawler SE Indirubins Decrease Glioma Invasion by Blocking Migratory Phenotypes in Both the Tumor and Stromal Endothelial Cell Compartments. Cancer Res. 2011, 71, 5374–5380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Erdlenbruch B; Nier M; Kern W; Hiddemann W; Pekrun A; Lakomek M Pharmacokinetics of Cisplatin and Relation to Nephrotoxicity in Paediatric Patients. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol 2001, 57, 393–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Urien S; Lokiec F Population Pharmacokinetics of Total and Unbound Plasma Cisplatin in Adult Patients. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol 2004, 57, 756–763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Daley-Yates PT; McBrien DCH The Mechanism of Renal Clearance of Cisplatin (cis-Dichlorodiammine Platinum II) and Its Modification by Furosemide and Probenecid. Biochem. Pharmacol 1982, 31, 2243–2246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Thiabaud G; Arambula JF; Siddik ZH; Sessler JL Photoinduced Reduction of PtIV within an Anti-Proliferative PtIV-Texaphyrin Conjugate. Chemistry 2014, 20, 8942–8947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.