Abstract

Objectives:

Research has shown that yoga may be an effective adjunctive treatment for persistent depression, the benefits of which may accumulate over time. The objectives of this study were to evaluate the following in a sample of persistently depressed individuals: whether yoga increases mindfulness and whether yoga attenuates rumination. Rumination and mindfulness both represent attentional processes relevant for onset and maintenance of depressive episodes.

Methods:

One-hundred-ten individuals who were persistently depressed despite ongoing use of pharmacological treatment were recruited into an RCT comparing yoga with a health education class. Mindfulness and rumination were assessed at baseline and across 3 time points during the ten-week intervention.

Results:

Findings demonstrate that, compared to health education, yoga was associated with higher mean levels of the observe facet of mindfulness relative to the control group during the intervention period (p =.004, d =0.38), and that yoga was associated with a faster rate of increase in levels of acting with awareness over the intervention period (p= .03, f2=0.027). There were no differences between intervention groups with respect to rumination.

Conclusions:

Results suggest a small effect of yoga on components of mindfulness during a 10-week intervention period. Previous research suggests that continued assessment after the initial 10 weeks may reveal continued improvement. Future research may also examine moderators of the impact of yoga on mindfulness and rumination, including clinical factors such as depression severity or depression chronicity, or demographic factors such as age.

Keywords: yoga, depression, persistent depression, mindfulness, rumination

Incomplete response to the pharmacological treatment of depression is a common problem. For example, almost 50% of participants in a large-scale trial of pharmacotherapy for depression were classified as non-responders (Corey-Lisle et al., 2004). Because of insufficient responses to initial pharmacological depression treatment, identifying effective adjunctive treatments for depression is important. A variety of adjunctive treatments for depression have been investigated, including additional pharmacological intervention and various forms of psychotherapy (e.g., Cuijpers, 2017; Papadimitropoulou, Vossen, Karabis, Donatti, & Kubitz, 2017). For example, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) demonstrated equivalent effectiveness for the treatment of depression as pharmacotherapy (Cuijpers et al., 2013). When specifically examining augmentation of pharmacological treatment with either additional pharmacological treatment or psychotherapy in the STAR*D trial, investigators found no difference in outcome between augmentation with additional pharmacological treatment or with psychotherapy (Warden, Rush, Trivedi, Fava, & Wisniewski, 2007). Further, with either augmentation strategy, some people still had an incomplete treatment response. Therefore, investigation of additional augmentation strategies – strategies that may target different mechanisms or appeal to different people -- appears warranted.

Hatha yoga represents one particularly promising adjunctive treatment. Hatha yoga is a group of practices – physical and mental – which can promote good physical and mental health. The practices of hatha yoga include physical postures (asanas), breath control (pranayama), and meditation (dhyana). Hatha yoga can promote mindfulness, (i.e., non-judgmental attention to the present moment), for example, by linking physical movement with the breath and by encouraging participants to notice physical sensations in the moment and let go of judgments their minds produce. Hatha yoga also includes physical movement and can be a moderate-intensity physical activity; physical activity has demonstrated efficacy for depression as well although the mechanisms are unclear (Schuch et al., 2016). The evidence base for yoga’s impact on depressive symptoms is growing. A meta-analysis of 12 randomized controlled trials of yoga for depression found that yoga intervention resulted in greater reductions in depression symptoms compared with the following interventions: usual care, relaxation, or aerobic exercise (Cramer et al. 2013). A subsequent review of the evidence of yoga for psychiatric disorders posited similarly that yoga may improve depressive symptoms (Duan-Porter et al., 2016).

Because depression can be a chronic and episodic illness, with recurrent episodes and an unknown course, treatments that alter factors associated with maintenance of current episodes and onset of new episodes are especially desirable. Hatha yoga may be capable of altering attentional processes relevant to onset and maintenance of depression, including mindfulness. Mindfulness is a commonly employed tool in relapse prevention for depression (Segal, Williams, & Teasdale, 2012) and has shown associations with shorter duration of depressive episodes (Finucane & Mercer 2006). Practitioners of yoga have reported that development of mindfulness is one of the psychosocial benefits of the practice (Park, Riley, & Braun, 2016). Hatha yoga has been shown to increase mindfulness relative to control groups in both non-depressed samples and in samples with anxiety and/or depression (Falsafi, 2016; Semich, 2012). Specifically, research has shown that among a sample of treatment-receiving college students with anxiety and/or depression, hatha yoga was effective at increasing mindfulness while the control group was not (Falsafi 2016).

Hatha yoga may also be capable of altering rumination. Rumination is an attentional process associated with both the development and maintenance of depressive episodes (Aldao, Nolen-Hoeksema, & Schweizer 2010; Nolen-Hoeksema 2000). Rumination is also associated with the severity of depression symptoms (D’Avanzato, Joormann, Siemer, & Gotlib, 2013). Rumination is a mode of engaging with distress wherein individuals repetitively and passively focus on the symptoms of distress and the possible causes and consequences of this distress (Gross & Thompson, 2007; Nolen-Hoeksema 1991). Initial research on the impact of yoga on rumination suggested a role for yoga in decreasing rumination among depressed females, wherein benefits appeared to be gained gradually over time (e.g., Kinser et al. 2013, 2014).

The present study is an analysis of hatha yoga’s impact on mindfulness and rumination in the context of a larger clinical trial which examined the impact of yoga versus control on persistent depression despite adequate pharmacological treatment. Primary analyses from this study found that yoga resulted in lower depression symptoms relative to the control group over the entire intervention and at the follow-up period, but not specifically at the 10-week intervention endpoint (Uebelacker et al., 2017). The aim of the present study is to replicate and extend previous research by examining whether hatha yoga is associated with change over time in mindfulness and rumination among a sample with persistent depression despite adequate pharmacological treatment. We hypothesize that yoga participants will show greater mindfulness and lower rumination over time relative to the control group. Depending on whether differences between groups occurred early in the intervention (i.e., at 3.3 weeks) or grew steadily over time, this might be represented as a) differences between group mean values over the intervention period; or b) differences between rates of change in the outcome variable over the intervention period, with yoga showing greater increases.

Method

Participants

Inclusion criteria were: 1) met criteria for major depressive disorder in the 2 years prior to the study, as assessed by the Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders -IV (DSM-IV) (SCID; First et al., 2001); 2) had a QIDS score greater than or equal to 8 (8 is in the range of mild depression symptoms) and less than or equal to 17 (i.e., in the severe range) ; 3) had no history of bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, or psychotic symptoms also assessed via the SCID; 4) were not engaging in current hazardous drug or alcohol use as assessed by the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (Babor et al., 2001; Berman et al., 2005); 5) did not have current suicidal ideation or behaviors requiring immediate attention; 6) were currently taking an antidepressant at a dose that has demonstrated effectiveness as per the American Psychiatric Association practice guidelines (Gelenberg et al., 2010) for at least 8 weeks; 7) the anti-depressant dose remained unchanged for 4 weeks prior and there were no plans to change the dose over the 10 week intervention phase; 8) if the participant was currently in psychotherapy, the frequency of this had not changed for 6 weeks prior and there were no plans to change the frequency over the 10 week intervention phase; 9) were medically cleared for moderate physical activity by their primary care providers; 10) were not pregnant or planning to become pregnant; 11) were not currently or recently engaged in yoga, tai chi, mindfulness based stress reduction, or health education classes or home practice sessions; 12) did not have a weekly meditation practice ; 13) were fluent in English; 14) were age 18 or older.

One-hundred-and-twenty-two participants met inclusion criteria for the parent study. Please see (Uebelacker et al., 2017) for consort diagram and power analysis conducted for the parent study. In order to be included in the current analyses, participants had to have provided data on at least one of the three intervention timepoints. One-hundred-and-ten participants met this additional criterion; 61 were randomized to the yoga group and 49 to the HLW group. Participants in the yoga condition attended an average of 9.1 classes (SD=5.0) and HLW participants attended an average of 8.2 classes (SD =5.5), t(108)=0.89, p =.38. In both conditions, a small number of participants never attended a single class, (1 in the yoga group and 3 in the HLW group). See Table 1 for information about missing data at each assessment point.

Table 1:

Raw Means and Standard Deviations By Treatment Group and Time Point

| Baseline (n= 110)* | 3.3 weeks (n=103)* | 6.6 weeks (n=94) | 10 weeks (n=102)* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FMQ Observe - Yoga | 23.31 (6.19) | 25.16 (5.85)a | 25.81 (6.18)a | 25.71 (7.01)a |

| FMQ Observe - HLW | 21.62 (6.75) | 21.47(7.30)b | 22.53 (6.96)b | 21.52(7.58)b |

| FMQ Describe - Yoga | 23.97 (8.71) | 25.56(8.38) | 25.59(8.08) | 27.24 (8.44) |

| FMQ Describe - HLW | 25.90 (7.43) | 26.09 (7.51) | 27.16 (7.78) | 27.01 (8.53) |

| FMQ Awareness - Yoga | 23.05 (6.78) | 23.85 (5.64) | 24.85 (5.94) | 26.58 (7.11) |

| FMQ Awareness -HLW | 24.29 (7.21) | 24.21 (6.64) | 24.76 (7.06) | 25.13 (6.85) |

| FMQ Nonjudgment -Yoga | 26.48 (7.44) | 25.94 (7.61) | 27.20 (7.23) | 29.43 (8.06) |

| FMQ Nonjudgment - HLW | 25.40 (7.92) | 26.81 (7.57) | 28.22 (7.54) | 29.64 (7.24) |

| FMQ Nonreact - Yoga | 18.69 (4.70) | 19.74 (3.94) | 19.44 (4.31) | 19.67 (4.75) |

| FMQ Nonreact - HLW | 19.04 (4.36) | 18.15 (4.40) | 19.43 (4.35) | 18.72 (4.82) |

| FMQ Total - Yoga | 127.70 (18.92) | 120.25 (19.32) | 122.89 (20.05) | 128.64 (23.91) |

| FMQ Total - HLW | 128.45 (19.39) | 116.74 (20.99) | 122.10 (22.82) | 122.03 (23.07) |

| Rumination - Yoga | 12.21 (2.80) | 11.37 (2.80) | 10.71 (2.77) | 10.93 (3.43) |

| Rumination - HLW | 12.46 (3.14) | 12.25 (2.92) | 11.03 (3.03) | 10.93 (3.19) |

Note: numbers with different superscripts indicate a statistically significant difference in group means

Due to missing data, the sample size for rumination was slightly smaller: n= 109 at baseline, n=102 at 3.3 weeks and 101 at 10 weeks.

Participants (n=110) had a mean age of 47.2 (SD = 11.8) and were predominantly female (86%), white/Caucasian (86%), non-Latino (96%), and had college or graduate degrees (60%). Participants did not differ significantly in their demographic characteristics across groups. Please see (Uebelacker et al., 2017) for additional demographic information for the entire sample (n=122). Many participants in this sample (n=110) met criteria for chronic depression (n=66, or 63% of those with data available for this variable, i.e., n = 104), with 41 (69%) yoga participants and 25 (56%) HLW participants having chronic depression χ2 (1, N=66) = 2.14, p = 0.14). Chronic depression was defined as having mood and other symptoms for at least 2 years, more than half the days, with no more than 2 months of feeling okay.

Procedure

The Institutional Review Board of Butler Hospital approved the procedures for the study. The trial is registered at clinicaltrials.gov (identifier: NCT01384916).

In order to participate in the study, individuals were screened via telephone. If individuals were potentially eligible, they came for an in-person interview (baseline 1) which included a structured depression interview (Quick Interview of Depression Symptomatology - Clinician Rating Scale (QIDS) (Rush et al., 2003) to determine eligibility. At this session, they also completed assessments of mindfulness and rumination. After the initial in-person interview, study personnel obtained medical clearance from the individuals’ PCPs, administered a second QIDS assessment (baseline 2), and randomized the participant.

Participants were randomized to groups with a 1:1 ratio via a computer program which performed urn randomization (Stout, Wirtz, Carbonari, & Del Boca, 1994). Randomization was stratified on the basis of three factors: gender, depression severity, and whether patient was receiving psychotherapy. Study personnel were blind to the condition to which the next participant would be randomized.

After randomization, participants were enrolled in the intervention phase of the study. The intervention phase lasted 10 weeks, during which participants were encouraged to attend classes in their assigned group. Participants were followed up with at 3-months and 6-months after the intervention period to assess depressive symptoms. Outcomes assessed in this study, i.e., mindfulness and rumination, were not assessed at 3 and 6 months follow ups.

Interventions.

Both interventions were manualized and individuals in both intervention groups had an individual meeting with their group’s instructor prior to attending their first class. Individuals in both groups were expected to attend at least one of two offered classes in their assigned intervention group per week over the 10-week intervention phase. Individuals were given the option of attending both classes in their assigned group during the week should they elect to do so.

Each yoga class was 80 minutes in duration and included breathing exercises (pranayama), seated meditation, warm-ups and half sun salutations, standing postures (asanas), seated postures, an inversion and a twist, relaxation (shavasana), and a wrap up and discussion of the home practice. The pace of the class was fit to those who were present and generally the class followed a gentle pace. In order to facilitate home practice, participants were given supportive materials (e.g., yoga mat, videos).

The instructor manual for the yoga group included guidance on how to teach the class as well as specific content. With regard to the concept of mindful attention, the manual included the following: “Frequently demonstrate and encourage mindfulness. This involves focusing on one’s experience in the present moment (thoughts, feelings, physical sensations, environment) in a non-judgmental way…” along with specific examples about how to do so, including “instruct participants to focus on feelings in specific parts of their body as they move into particular asanas, as they practice pranayama, or as they meditate…. For example, you might say, ‘Sense into your face, your lips, your arms, your hands. Feel the sensation in your palms.’” Additionally, the manual included guidance on repeatedly connecting breath with movement. Thus, these instructions relate most clearly to the mindfulness facets of observing and acting with awareness. The manual also included guidance on discussing and modeling acceptance of one’s own physical abilities. Instructors were rated on adherence to the manual, including on adherence to these three items: “mindfulness instruction,” “acceptance of one’s own physical abilities,” and “connection between breath and movement,” and of the sample of 55 classes rated, all were rated as acceptable on these three items. Please see (Uebelacker et al., 2017) for more information.

HLW classes were held in a group format and were concurrent with yoga classes. FILW classes followed a manual adapted from prior work with psychiatric patients and smokers (Abrantes et al. 2012, 2014). Each class was 60 minutes in duration and included slides, audio or video clips, and/or demonstrations. Course content included topics ranging from diabetes to physical activity to prevalence and causes of depression. While classes were interactive, personal problems of participants were not a focus. In order to facilitate learning between sessions, participants were given supportive materials (e.g., handouts and lists of websites with relevant information).

Measures

Assessment of depression occurred at baseline 1 (eligibility assessment), at baseline 2 (randomization) and every subsequent time point, 3.3 weeks, 6.6 weeks, and 10 weeks (end of intervention phase). Assessment of mindfulness and rumination occurred for the first time at baseline 1, and then again at 3.3 weeks, 6.6 weeks, and 10 weeks. Mindfulness and rumination were not assessed at 3 or 6 months follow-up point. To assess diagnoses for exclusion criteria, PhD level psychologists and trained research assistants supervised by a psychologist administered the SCID (First et al., 2001).

Depression.

Trained, treatment-blinded interviewers administered the QIDS (Rush et al., 2003). The QIDS assesses nine DSM symptoms of depression; scores of 6-10 reflect mild depression symptoms, 11-15 moderate, and 16 or greater reflect severe, and 21 or greater very severe symptoms. A subset (61) of the interviews were reviewed for reliability by a second rater; reliability was excellent (intraclass correlation coefficient = 0.96).

Mindfulness.

Mindfulness was assessed via self-report using the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ; Baer et al., 2006). The FFMQ consists of 39 items that assess five facets of mindfulness, including observing (noticing one’s internal and external experiences), describing (describing one’s experiences with words), acting with awareness (paying attention to what one is doing in the moment), non-judging of inner experience (not positively or negatively evaluating one’s own thoughts and feelings), and non-reactivity to inner experience (not clinging to or pushing away one’s own thoughts and feelings). Each item is rated on a Likert scale from 1 (never or very rarely true) to 5 (very often or always true). A total mindfulness score is also calculated. Internal consistency ranged from .70-,94 across the subscales and total score; average Cronbach’s alpha was .88.

Rumination.

The brooding subscale of the Response Styles Questionnaire was used to assess rumination (RSQ; Nolen-Hoeksema and Morrow 1991; Treynor, Gonzalez, & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2003). Relative to the ruminative reflection subscale, the ruminative brooding subscale was chosen as it shows a greater, positive association with depression concurrently and longitudinally (Treynor et al., 2003). The brooding subscale contains 5 items which participants rate on a l(never) −4 (always) Likert scale; average Cronbach’s alpha was .79 and ranged across time points from .76-.83.

Data Analyses

We examined the effects of treatment group (represented with a dummy coded variable) on outcomes via linear mixed effects models (LME) that nest observations within participants. We employed a random intercept and an unstructured covariance matrix. The linear mixed effects model we used estimates change trajectories for all participants with the outcome data available for at least one intervention timepoint (of 3 possible – i.e., 3.3 weeks, 6.6 weeks, or 10 weeks). The effect of this is to limit our sample size to 110 participants, as described above.

We investigated the effect of treatment group on each of the seven possible (secondary) outcomes (i.e., facets of mindfulness including: observing, describing, nonjudgment, nonreactivity, acting with awareness, as well as total mindfulness, and rumination). To examine the effect of treatment group independent of the influence of baseline depression severity, we included the first baseline depression score as a covariate. To analyze whether the effect of treatment group indicated significant mean differences between groups across all non-baseline time points, the baseline value of the outcome variable was not included as part of the dependent variable and was instead included as a covariate. Time was centered at half-way through the intervention period. To understand whether there was a difference between groups in rate of change in a given outcome variable over time, we also tested treatment group by time interactions. Thus, each model included the following variables: intercept, baseline depression, baseline value of the outcome variable, time by treatment group interaction, treatment group, and time. All analyses were conducted in Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) Version 25 and all figures were generated in Microsoft Excel.

To calculate effect size estimates for significant main effects, we divided the parameter estimate representing the group effect by the pooled SD for that variable at baseline. This is interpretable as a Cohen’s d; values of 0.20, 0.50, and 0.80 represent small, medium, and large effects respectively. To calculate effect size estimates for significant interaction effects, we calculated a pseudo-R2 (Singer & Willett, 2003) for the model with and without the interaction term included, and then calculated Cohen’s f-squared statistic. For this statistic, values of 0.02,0.15, and 0.35 represent small, medium, and large effects respectively.

Results

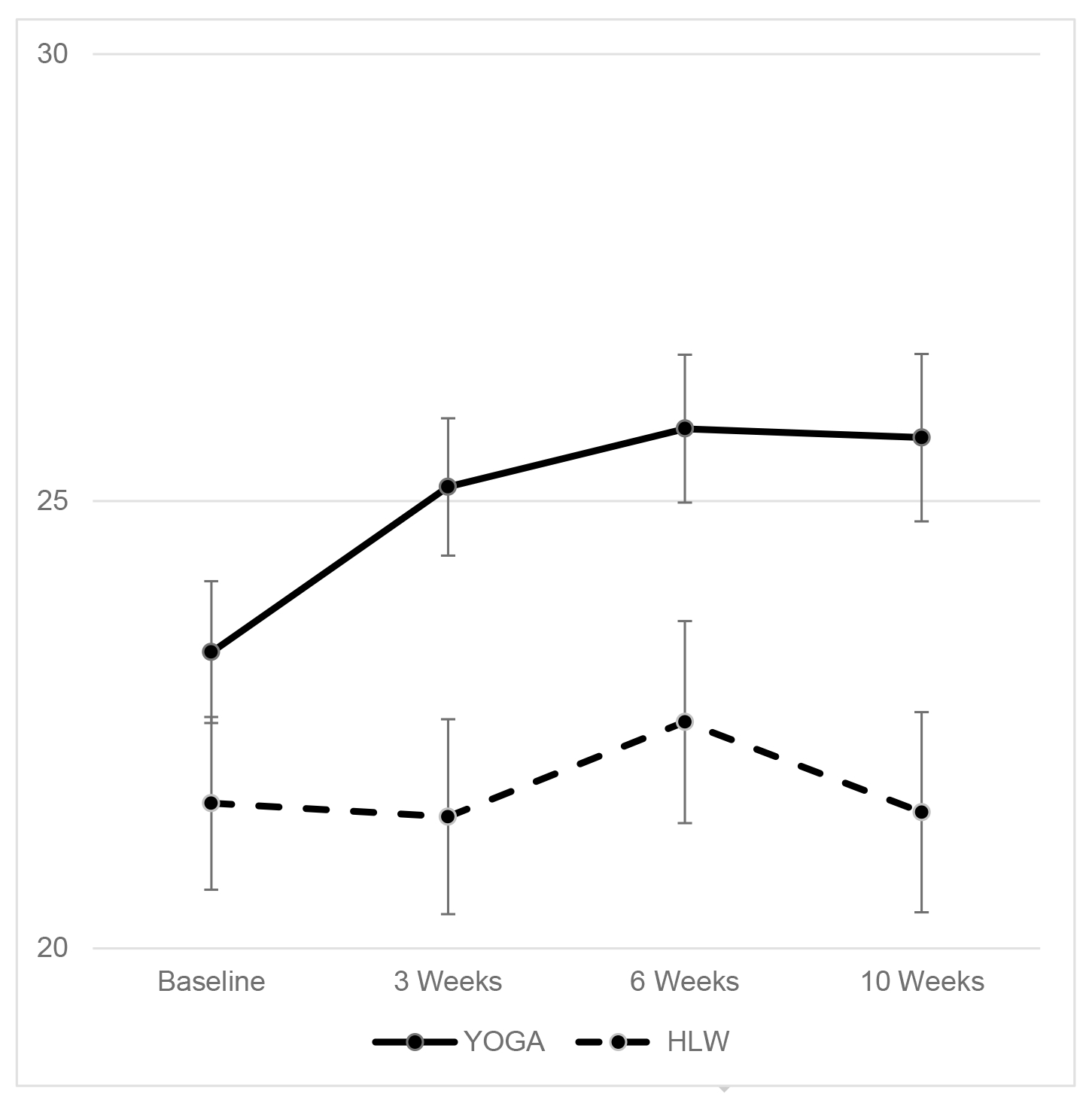

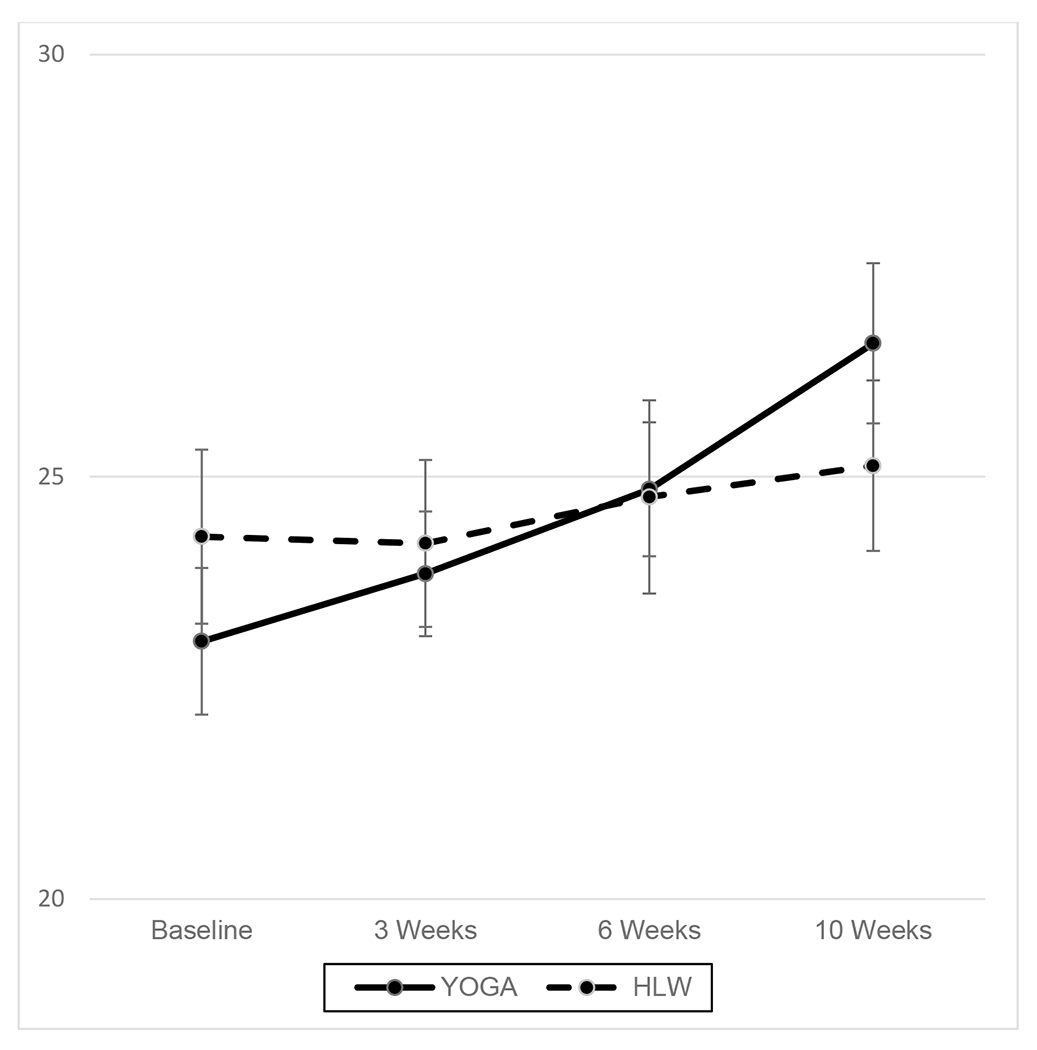

First, we analyzed the impact of treatment group on facets of mindfulness. We found mixed results in the impact of yoga on the different facets of mindfulness relative to HLW and with respect to the importance of the rate of change. When analyzing the impact of yoga v HLW on the observe facet of mindfulness, we found no significant treatment group x time effect, but did find that there was a significant difference between treatment groups on average over the entire intervention period, b= 2.46, p =.004 (see figure 1 for plotted actual mean values), individuals in the yoga group showed consistently higher scores on the observe subscale across weeks 3.3, 6.6, and 10. The effect size for this finding is interpretable as Cohen’s d and is = 0.38. This is a small-moderate effect size. With respect to awareness, we found a significant time by treatment group interaction, b = .92, p = .03, indicating that there was a significant difference between groups in the rate of change in awareness over time (see figure 2 for plotted actual mean values). The effect size for this finding is interpretable as Cohen’s f2 and is = 0.027, a small effect size. Individuals in the yoga group showed steady increases in awareness over time, whereas those in the HLW group stayed at approximately the same level over time. The two groups did not differ in mean levels of awareness consistently over the entire intervention period. Finally, with respect to the describe, nonjudgment, and nonreactivity facets of mindfulness and the mindfulness total score, we found no significant effects of treatment group or time by treatment group.

Fig.1.

Mean Values and Standard Errors (SEs) of Observe Across Time

Fig. 2.

Mean Values and Standard Errors (SEs) of Acting with Awareness Across Time

Next, we examined treatment group differences in intervention modalities for rumination. We found no significant difference between treatment groups over the entire intervention period on average and no significant treatment group by time interaction (see table 2 for this and all other non-significant results).

Table 2:

Results of LME Models

| Parameter Estimate (95% CI) | Standard Error | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| FMQ Observe | |||

| Intercept | 10.73 (5.61 to 15.85) | 2.60 | .00 |

| Time | .11 (−.52 to .74) | .32 | .73 |

| Baseline FMQ Observe | .70 (.57 to .83) | 0.07 | .00 |

| Baseline Depression | −.31 (−.61 to −.02) | 0.15 | .039 |

| Group: Yoga v HLW | 2.46 (.79 to 4.13) | 0.84 | .004 |

| Time X Group Interaction | 0.48 (−.36 to 1.32) | 0.43 | .26 |

| FMQ Describe | |||

| Intercept | 9.51(4.81 to 14.21) | 2.37 | .00 |

| Time | .53 (−.06 to 1.12) | .30 | .08 |

| Baseline FMQ Describe | .82 (.72 to .91) | 0.05 | .00 |

| Baseline Depression | −.33 (−.60 to −.05) | 0.14 | .021 |

| Group: Yoga V HLW | 1.21 (−.34 to 2.77) | 0.79 | .13 |

| Time X Group Interaction | .09 (−.70 to .88) | 0.4 | .83 |

| FMQ Awareness | |||

| Intercept | 13.80 (8.62 to 18.98) | 2.61 | .00 |

| Time | .38 (−.23 to .99) | .31 | .22 |

| Baseline FMQ Awareness | .64 (.52 to .75) | 0.06 | .00 |

| Baseline Depression | −.36 (−.63 to −.08) | 0.14 | .011 |

| Group: Yoga v HLW | 1.11 (−.36 to 2.58) | 0.74 | .14 |

| Time X Group Interaction | .92 (.10 to 1.74) | 0.41 | .028 |

| FMQ Nonjudgment | |||

| Intercept | 17.64 (12.07 to 23.22) | 2.81 | .00 |

| Time | 1.31 (.50 to 2.12) | .41 | .002 |

| Baseline FMQ Nonjudgment | .64 (.52 to .75) | 0.06 | .00 |

| Baseline Depression | −.41 (−.72 to −.10) | 0.16 | .01 |

| Group: Yoga v HLW | −1.7 (−.34 to .04) | 0.87 | .06 |

| Time X Group Interaction | .24 (−.85 to 1.32) | 0.55 | .67 |

| FMQ Nonreact | |||

| Intercept | 10.28 (6.25 to 14.30) | 2.03 | .00 |

| Time | .44 (−.04 to .92) | .24 | .07 |

| Baseline FMQ Nonreact | .57 (.45 to .70) | 0.06 | .00 |

| Baseline Depression | −.19 (−.40 to .01) | 0.1 | .07 |

| Group: Yoga v HLW | 1.03 (−.11 to 2.18) | 0.58 | .08 |

| Time X Group Interaction | −.49 (−1.14 to .14) | 0.33 | .13 |

| FMQ Total | |||

| Intercept | 65.20 (42.92 to 87.50) | 11.25 | .00 |

| Time | 2.77 (.86 to 4.70) | .97 | .005 |

| Baseline FMQ Total | .61 (.49 to .73) | 0.06 | .00 |

| Baseline Depression | −1.76 (−2.70 to −.82) | 0.48 | .00 |

| Group: Yoga v HLW | 2.62 (−2.50 to 7.75) | 2.59 | .31 |

| Time X Group Interaction | 1.27 (−1.29 to 3.81) | 1.3 | .33 |

| Rumination | |||

| Intercept | −.36 (−2.41 to 1.70) | 1.04 | .73 |

| Time | −.62 (−.96 to −.28) | 0.17 | .00 |

| Baseline Rumination | .63 (.52 to .75) | 0.06 | .00 |

| Baseline Depression | .31 (.19 to .43) | 0.06 | .00 |

| Group: Yoga v HLW | −.30 (−.97 to .38) | 0.34 | .38 |

| Time X Group Interaction | .43 (−.03 to .88) | 0.23 | .06 |

As mentioned above, baseline depression level was included as a covariate. Across all models, baseline depression significantly predicted the average value of the outcome variable across the non-baseline time points in all but one model. Higher depression scores at baseline predicted lower average levels of mindfulness and higher average levels of rumination.

Discussion

Prior studies utilizing clinical samples indicate that yoga may be an intervention capable of altering attentional processes relevant to major depressive disorder, specifically mindfulness and rumination. Mindfulness and rumination can be important resilience and risk factors for major depression and, therefore, the aim of the present study was to extend prior findings into a sample with persistent depression who were all taking antidepressants for depression.

In the present study, we found that yoga had an impact on two specific aspects of mindfulness. First, we found that hatha yoga, relative to control, was associated with greater tendency to observe across all intervention time points, while controlling for the baseline observe score. This finding suggests that there was a significant difference between groups that emerged relatively early in the intervention and was sustained. As the observe facet of mindfulness assesses an individual’s tendency to notice experiences (sensations, sights, emotions), the observe facet may be directly targeted by instructions given in yoga classes to observe sensations, emotions, and experiences with curiosity.

Second, we found a significant interaction between treatment group and time with respect to acting with awareness. This finding suggests that the interventions fostered a different rate of change in acting with awareness between the yoga group and the HLW group. That is, acting with awareness increased between week 3.3 and week 10 in the yoga group but not in the HLW group. The lack of significant main effect indicates that there was not a significant difference in mean values of acting with awareness between the groups on average over the intervention period despite the difference in rate of change. Similar to the observe facet, the acting with awareness facet is directly remarked upon in yoga classes with instructions to intentionally bring awareness to each action. As shown in figure 2, acting with awareness may be a skill that continuously improves with time and repeated practice.

Current findings will require further replication to be confirmed. However, if individuals are able to gain the ability to observe thoughts, feelings, and body sensations with curiosity and direct awareness, the increased elaboration of negative information which can characterize depression may be attenuated (Everaert, Podina, & Koster, 2017; Gotlib & Joorman, 2010). Likewise, if individuals are able to show increases in acting with awareness, they may be able to generalize this skill to day to day life and step out of autopilot actions which can also characterize depression (e.g., Marchand, 2016; Segal et al., 2012). Further, if individuals are able to act with awareness and pay more attention to pleasant things while they do them, instead of being mentally elsewhere, they may be more able to experience subjective enjoyment, thus decreasing anhedonia.

There are several possible reasons we did not see significant differences on some of the mindfulness facets. In yoga classes, instructors did give direct instructions to observe the breath or body, or to act with awareness – i.e., to pay attention to movements of the body in the moment. This direct instruction may result in the desired skill acquisition. In contrast, instructors were unlikely to ask participants to describe their experiences with words. Further, although instructors may have asked participants to be non-judgmental and non-reactive to internal experiences in classes, and certainly modeled acceptance (particularly of the physical body), these facets of mindfulness may be more complicated and cognitively demanding than the observe and acting with awareness facets. Thus, it may take more time to learn and generalize these challenging skills; this may be especially difficult for individuals with persistent depression.

Unlike prior research, we did not find that yoga was more effective at increasing an individual's total mindfulness than a control group (cf. Falsafi, 2016). In both the current study and in the study by Falsafi, total mindfulness scores increased over time. The difference is that we did not see a significant difference between groups in the current study. These differing results might be explained by many factors: differences in measurement (different assessment tools were used), samples (our sample had more severe mental health symptoms and were of an older age), or, potentially, control groups (i.e., we used an active control group, whereas their control group did not receive any intervention). Additional research is needed to better understand the conditions under which a composite mindfulness score may be favorably altered.

A second aim of the present study was to examine the impact of yoga relative to control on rumination. Our findings were consistent with some previous research (e.g. Kinser et al., 2013) but not other research (Kinser et al., 2014). In addition to the potential for random variation to produce these mixed findings, mixed findings could also be explained by the amount of time that has elapsed since yoga intervention. In our study and Kinser et al.’s 2013 study, rumination was assessed immediately post-intervention; however, in Kinser et al.’s 2014 study, rumination was assessed at a one-year follow up point. Further supporting the notion that the impact of yoga may take time to develop, the parent study found differences between yoga and control group in depression scores only after the end of the study intervention period, across the follow-up period (Uebelacker et al., 2017).

Across our outcome variables, we found that baseline depression was always either significantly or marginally associated with the outcome variable. These findings are consistent with prior longitudinal research showing that depressive symptoms were prospectively associated with rumination (Calvete, Orue, & Hankin, 2015; Nolen-Hoeksema, Stice, Wade, & Bohon, 2007) and with most facets of mindfulness (Barnhofer et al. 2011). The association between depression and our outcome variables indicates that depression influences how much benefit someone can gain from the intervention. In controlling for depression’s influence, however, we found that on average yoga can still be a helpful intervention for those struggling with persistent depression. This remains an important area to examine in future research, especially because prior research indicates that these effects may emerge over time after the intervention period has ended (e.g., Kinser et al., 2014; Uebelacker et al., 2017). Depression significantly interferes with attention and concentration, and thus, the ability to crystalize and extend these skills may take time.

Limitations and Future Research

A limitation of the current study includes the lack of assessments of mindfulness and rumination after the classes ended, as prior literature illustrates that some of yoga’s more promising effects may emerge after the treatment period elapses. Further, assessments of mindfulness and rumination are based on self-report. This is the current standard in the field; however, it would be useful to have robust behavioral measures of these concepts. Future studies may address these limitations. Future research may also examine moderators of the impact of yoga on mindfulness and rumination, including clinical factors such as depression severity or depression chronicity, or demographic factors such as age.

Acknowledgements:

Research described in this article was financially supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research of the National Institutes of Health, award number RO1NR012005. The randomized controlled trial is registered at clinicaltrials.gov (identifier: NCT01384916).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

Disclosures: L.A.U.’s spouse is employed by Abbvie pharmaceuticals.

Butler Hospital: 345 Blackstone Blvd, Providence, RI 02906

Rhode Island Hospital: 593 Eddy St, Providence RI 02903

Conflict of interests: L.A.U.’s spouse is employed by Abbvie pharmaceuticals. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The institutional review board of Butler Hospital approved the study. All persons gave their informed consent prior to inclusion in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- Abrantes AM, Bloom EL, Strong DR, Riebe D, Marcus BH, Desaulniers J, Fokas K, & Brown RA (2014). A preliminary randomized controlled trial of a behavioral exercise intervention for smoking cessation. Nicotine and Tobacco Research, 16(8), 1094–1103. 10.1093/ntr/ntu036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abrantes AM, McLaughlin N, Greenberg BD, Strong DR, Riebe D, Mancebo M, Rasmussen S, Desaulniers J, & Brown RA (2012). Design and rationale for a randomized controlled trial testing the efficacy of aerobic exercise for patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Mental Health and Physical Activity,5(2), 155–165. 10.1016/j.mhpa.2012.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldao A, Nolen-Hoeksema S, & Schweizer S (2010). Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(2), 217–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer RA, Smith GT, Hopkins J, Krietemeyer J, & Toney L (2006). Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment, 13(1), 27–45. 10.1177/1073191105283504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG (2001). The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) Manual. World Heath Organization: Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- Barnhofer T, Duggan DS, & Griffith JW (2011). Dispositional mindfulness moderates the relation between neuroticism and depressive symptoms. Personality and Individual Differences,51(8), 958–962. 10.1016/j.paid.2011.07.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman AH, Bergman H, Palmstierna T, & Schlyter F (2005). Drug Use Disorder Identification Test, Version 1.0 Karolinska Institutet, Department of Clinical Neuroscience: Stockholm [Google Scholar]

- Calvete E, Orue I, & Hankin BL (2015). Cross-lagged associations among ruminative response style, stressors, and depressive symptoms in adolescents. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 34(3), 203–220. [Google Scholar]

- Corey-Lisle PK, Nash R, Stang P, & Swindle R (2004). Response, partial response, and nonresponse in primary care treatment of depression. Archives of Internal Medicine, 164(11), 1197–1204. 10.1001/archinte.164.11.1197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer H, Lauche R, Haller H, & Dobos G (2013). A systematic review and meta-analysis of yoga for low back pain. The Clinical Journal of Pain, 29(5), 450–460. 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31825e1492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers P (2017). Four decades of outcome research on psychotherapies for adult depression: An overview of a series of meta-analyses. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne, 58(1), 7–19. [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers P, Berking M, Andersson G, Quigley L, Kleiboer A, & Dobson KS (2013). A meta-analysis of cognitive-behavioural therapy for adult depression, alone and in comparison with other treatments. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 58(7), 376–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Avanzato C, Joormann J, Siemer M, & Gotlib IH (2013). Emotion regulation in depression and anxiety: examining diagnostic specificity and stability of strategy use. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 37(5), 968–980. [Google Scholar]

- Duan-Porter W, Coeytaux RR, McDuffie JR, Goode AP, Sharma P, Mennella H,… & Williams JW Jr (2016). Evidence Map of Yoga for Depression, Anxiety, and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 13(3), 281–288. 10.1123/jpah.2015-0027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everaert J, Podina IR, & Koster EH (2017). A comprehensive meta-analysis of interpretation biases in depression. Clinical Psychology Review, 58, 33–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falsafi N (2016). A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness versus yoga: effects on depression and/or anxiety in college students. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 22(6), 483–497. 10.1177/1078390316663307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finucane A, & Mercer SW (2006). An exploratory mixed methods study of the acceptability and effectiveness of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for patients with active depression and anxiety in primary care. BMC Psychiatry, 6(1), 14. 10.1186/1471-244X-6-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, & Williams JBW (2001). Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, research version, patient edition with psychotic screen (SCID-I/P W/ PSY SCREEN). Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute: New York. [Google Scholar]

- Gelenberg AJ, Freeman MP, Markowitz JC, Rosenbaum JF, Thase ME, Trivedi MH, & Van Rhoads RS (2010). Work Group on Major Depressive Disorder. Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Major Depressive Disorder, 3rd ed.. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association: [Google Scholar]

- Gotlib IH, & Joormann J (2010). Cognition and Depression: Current Status and Future Directions. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 6, 285–312. 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ, & Thompson RA (2007). Emotion regulation: Conceptual foundations. In Gross JJ (Ed.), Handbook of emotion regulation (pp. 3–24). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kinser PA, Bourguignon C, Whaley D, Hauenstein E, & Taylor AG (2013). Feasibility, acceptability, and effects of gentle hatha yoga for women with major depression: findings from a randomized controlled mixed-methods study. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 27(3), 137–147. 10.1016/j.apnu.2013.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinser PA, Elswick RK, & Kornstein S (2014). Potential long-term effects of a mind-body intervention for women with major depressive disorder: Sustained mental health improvements with a pilot yoga intervention. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 28(6), 377–383. 10.1016/j.apnu.2014.08.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchand WR (2016). Mindfulness for the treatment of depression. In Shonin E, Gordon WV, & Grififiths M (Eds). Mindfulness and buddhist-derived approaches in mental health and addiction (pp. 139–163). Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S (1991). Responses to depression and their effects on the duration of depressive episodes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100(4), 569. 10.1037/0021-843X.100.4.569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S (2000). The role of rumination in depressive disorders and mixed anxiety/depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109(3), 504. 10.1037/0021-843X.109.3.504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, & Morrow J (1991). A prospective study of depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms after a natural disaster: the 1989 Loma Prieta Earthquake. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(1), 115. 10.1037/0022-3514.61.1.115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Stice E, Wade E, & Bohon C (2007). Reciprocal relations between rumination and bulimic, substance abuse, and depressive symptoms in female adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 116(1), 198–207. 10.1037/0021-843X.116.1.198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadimitropoulou Katerina, Vossen Carla, Karabis Andreas, Donatti Christina & Kubitz Nicole (2017) Comparative efficacy and tolerability of pharmacological and somatic interventions in adult patients with treatment-resistant depression: a systematic review and network meta-analysis, Current Medical Research and Opinion, 33(4), 701–711, DOI: 10.1080/03007995.2016.1277201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CL, Riley KE, & Braun TD (2016). Practitioners’ perceptions of yoga’s positive and negative effects: Results of a national united states survey. Journal of Bodywork & Movement Therapies, 20(2), 270–279. 10.1016/j.jbmt.2015.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush AJ, Trivedi ΜH, Ibrahim HM, Carmody TJ, Arnow B, Klein DN,… & Thase ME (2003). The 16-Item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS), clinician rating (QIDS-C), and self-report (QIDS-SR): a psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic major depression. Biological Psychiatry, 54(5), 573–583. 10.1016/S0006-3223(02)01866-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuch FB, Vancampfort D, Richards J, Rosenbaum S, Ward PB, & Stubbs B (2016). Exercise as treatment for depression: a meta-analysis adjusting for publication bias. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 77, 42–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal ZV, Williams JMG, & Teasdale JD (2012). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression (2nd ed). New York: Guilford Press [Google Scholar]

- Semich AM (2012). Effects of two different hatha yoga interventions on perceived stress and five facets of mindfulness (Doctoral dissertation, Northcentral University; ). [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD & Willett JB (2003). Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stout RL, Wirtz PW, Carbonari JP, & Del Boca FK (1994). Ensuring balanced distribution of prognostic factors in treatment outcome research. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, Supplement, (s12), 70–75. 10.15288/jsas.1994.s12.70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treynor W, Gonzalez R, & Nolen-Hoeksema S (2003). Rumination reconsidered: A psychometric analysis. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 27(3), 247–259. [Google Scholar]

- Uebelacker LA, Tremont G, Gillete LT, Epstein-Lubow G, Strong DR, Abrantes AM,… & Miller IW (2017). Adjunctive yoga v health education for persistent major depression: a randomized controlled trial. Psychological Medicine, 47(12), 2130–2142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warden D, Rush A, Trivedi MH, Fava M, & Wisniewski SR, (2007). The STAR*D Project results: a comprehensive review of findings. Current Psychiatry Reports, 9(6), 449–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]