Abstract

Cutaneous lesions of leukemia cutis (LC) by chronic neutrophilic leukemia (CNL) have been merely reported due to the rare occurrences of CNL. Furthermore cutaneous lesions in relation to clinical severity have been far less studied. A 70-year-old man presented with multiple violaceous papules and excoriations on both lower extremities. The diagnosis was LC based on histologic and laboratory evaluation and the origin was elaborated as CNL with the confirmation of colony stimulating factor 3 receptor (CSF3R) mutation. Interestingly, the patient presented clinical severity in a parallel manner to the hematologic abnormality. To the best of our knowledge, there has been no reported case of CSF3R confirmed LC in CNL featuring explicit skin eruption in relation to laboratory findings.

Keywords: Colony-stimulating factors 3 receptor; Leukemia cutis; Leukemia, neutrophilic, chronic

INTRODUCTION

Leukemia cutis (LC) is characterized as infiltration of leukemic cells into the skin resulting in various cutaneous lesions1. While the incidence of LC varies on the underlying malignancy, its association with chronic neutrophilic leukemia (CNL) is extremely rare, limited to only a few case reports2. Moreover, previous cases of LC undervalued the hematologic correlation to the severity of skin presentation since LC often arises in advanced stages with short survival periods. Although, colony stimulating factor 3 receptor (CSF3R) mutation has further elucidated the nature of CNL, its association with the clinical significance of LC was not underscored3. Herein, we report the first case of LC associated with CNL confirmed through CSF3R gene mutation, featuring explicit skin eruption in a paralleled manner to hematologic abnormality.

CASE REPORT

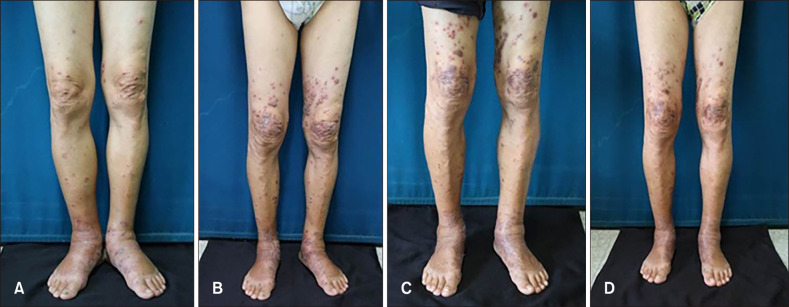

A 70-year-old man presented with multiple erythematous to violaceous papules and excoriations on both lower extremities for two weeks. The lesions started as pea-sized papules on both ankles and had spread to the entire lower extremities. The nature of excoriation occasionally bled and had been macerated. Subsequent oral steroid and empiric antibiotics failed to alleviate the lesions. The patient had no medical condition or family history of skin cancer and was otherwise in good health. Vital signs were stable and numerous non-tender 1 to 2 cm sized papules overlying erythema with pitting edema were present on physical examination (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1. Serial clinical images. (A) Skin lesion at initial visit featuring multiple red to violaceous papules and plaques with severe oozing and edema on the feet, leukocyte count (63,500/mm3) (B) Aggravation of skin lesion after dosage reduction of hydroxyurea (hydroxycarbamide 0.5 g) leukocyte count (113,000/mm3) (C) Aggravation of skin lesion despite initial dosage of hydroxyurea (hydroxycarbamide 1 g) leukocyte count (98,150/mm3) (D) Improvement of skin lesion after double of initial hydroxyurea dosage (hydroxycarbamide 2 g) with concomitant improvement of leukocytosis, leukocyte count (22,000/mm3).

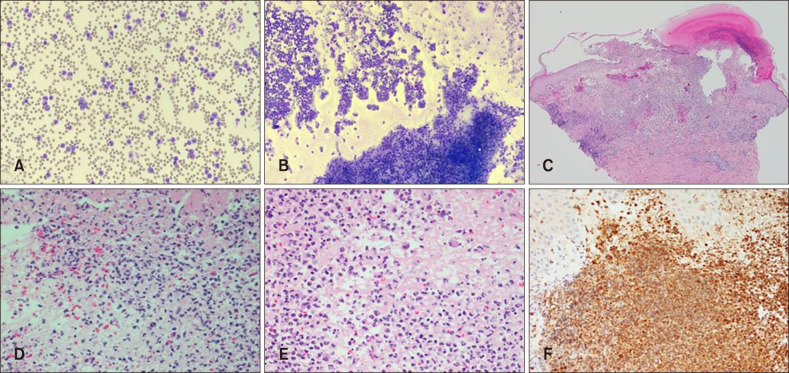

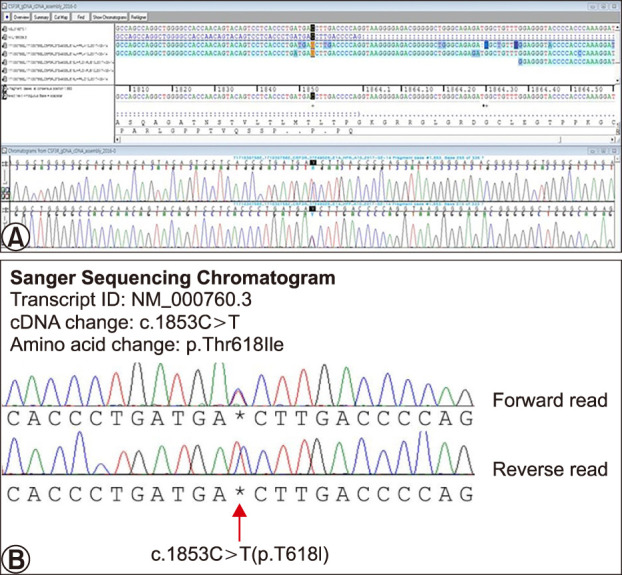

Laboratory results revealed severe leukocytosis (63,500/mm3), elevated erythrocyte sedimentary rate (41 mm/h), elevated C-reactive protein (24.3 mg/L) with high turnover markers including alkaline phosphatase (458 U/L) and lactate dehydrogenase (1,067 U/L). Splenomegaly and hepatomegaly were observed on enhanced abdominal computed tomography. Peripheral blood smear revealed major percentages of neutrophils with all stages of neutrophilic precursor cells including promyelocytes, myelocytes and metamyelocytes (Fig. 2A). Counting of peripheral blood smear revealed over 90% of segmental neutrophils with 4.6% of neutrophilic precursor cells. Bone marrow biopsy remarked hypercellular nature with abundant neutrophils and scanty erythroid cells and megakaryocytes (Fig. 2B). Skin biopsy performed on the latest erupted lesion revealed diffuse dermal infiltration of inhomogeneous neutrophils with pustules on scanning magnification (Fig. 2C). Higher magnification showed variable sizes and shapes in nucleus with both mature and immature neutrophilic components. Atypia and mitotic figures were also pronounced (Fig. 2D). Bizarrely large cells with multiple segmented bands are dispersed with heavy infiltration of neutrophils (Fig. 2E). Staining of myeloperoxidase was consistent with the leukemic nature of the infiltrates (Fig. 2F). The patient was initially diagnosed with chronic myelogenous leukemia. However, evaluation of CSF3R gene mutation was performed when negative results were confirmed in BCL-ABR, JAK2, and V617F tests. The pathologic variant was observed at the 1,853th base-sequence, where cytosine was transferred to thymine, leading to subsequent substitution of threonine to isoleucine (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2. (A) Peripheral blood smear exhibits dominantly abundant nature of segmented and band form neutrophils with all stages of neutrophil precursors including promyelocytes, myelocyte and metamyelocyte. (B) Bone marrow biopsy reveals hypercellularity of cells and red marrow with dominant number of neutrophilic granulocytes bearing normal maturation. Myelobastic cells are less than 5% on the captured microscopic field. (C) Scanning magnification of the skin biopsy revealed diffuse infiltration of inhomogenous neutrophils with pustular formation (H&E, ×40). (D) Higher magnification reveals variable sizes and shapes of both the nucleus and the cells with characteristics (H&E, ×400). (E) Both immature and mature neutrophilic components are shown with low degree of atypia in size and shapes (H&E, ×400). (F) Positive immunohistochemical staining result to myeloperoxidase stain is observed (MPO, ×200).

Fig. 3. Genetic study of the colony stimulating factor 3 receptor through Sanger gene deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) sequencing chromatogram analysis. (A) Original transcript of the sequenced data (SCLLAB 20170209-310878). (B) Extracted sequence of the abnormality exhibiting pathologic variant at the 1,853th base-sequence, where cytosine was transferred to thymine, leading to subsequent substitution of threonine to isoleucine (red arrow).

Oral hydroxyurea at a dose of 500mg twice a day and daily cefazolin 2 g was given to the patient. After one week, both the leukocyte count and skin lesions improved. Antibiotics were withdrawn and hydroxyurea was reduced to half of the initial dosage. After two weeks, the previously improved skin lesions aggravated in response to marked increase of leukocyte count (Fig. 1B). Hydroxyurea was raised to the initial dosage, however, cutaneous lesions and leukocytosis showed no improvements (Fig. 1C). Dosage of hydroxyurea was doubled for two weeks and the severity of skin lesion mitigated as the level of leukocytosis decreased (Fig. 1D). After two months, the patient was administered with interferon alpha and no further drastic fluctuation in both skin lesion and leukocyte counts were observed since then. All photographic materials for the purpose of publication were displayed with the patient's consent.

DISCUSSION

According to the revised 2016 World Health Organization (WHO) diagnostic criteria for CNL, the addition of CSFRT618I or other membrane proximal CSF3R mutations play a significant role in redefining of the disease4,5 (Table 1). Previous diagnostic criteria were limited based on laboratory and clinical characteristics and mainly exclusions of other myeloproliferative diseases6. The patient in the case presented features consistent to LC regardless of the CSF3R gene analysis.

Table 1. WHO 2016 Revised Diagnostic Criteria for chronic neutrophilic leukemia.

| 1. Peripheral blood WBC ≥25×109/L |

| Segmented neutrophils plus band forms ≥80% of WBC |

| Neutrophil precursors (promyelocytes, myelocytes, and metamyelocytes) <10% of WBC |

| Myeloblasts rarely observed |

| Monocyte count <1×109/L |

| No dysgranulopoiesis |

| 2. Hypercellular bone marrow |

| Neutrophil granulocytes increased in percentage and number |

| Normal neutrophil maturation |

| Myeloblasts <5% of nucleated cells |

| 3. Not meeting WHO criteria for BCR-ABL+ CML, PV, ET, or PMF |

| 4. No rearrangement of PDGFRA, PDGFRB, or FGFR1, or PCM1-JAK2 |

| 5. Presence of CSF3RT618I or other activating CSF3R mutation |

| In the absence of a CSFR3R mutation, persistent neutrophilia (at least 3 months), splenomegaly, and no identifiable cause of reactive neutrophilia including absence of a plasma cell neoplasm or, if present, demonstration of clonality of myeloid cells by cytogenetic or molecular studies |

WHO: World Health Organization, WBC: white blood cells, CML: chronic myeloid leukemia, PV: polycythemia vera, ET: essential thrombocythemia, PMF: primary myelofibrosis.

Infectious or reactive natures of the disease was unlikely due to ineffectiveness of steroids and antibiotics therapies. Gradual onset without tenderness were distant from the characteristics of reactive neutrophilic dermatosis, especially that of the Sweet's syndrome. Abnormal laboratory results and pathologic expression to myeloperoxidase staining with good response to chemotherapy were conclusive clues to diagnosing malignant leukemic cells. However instead of further immunohistochemical stains to differentiate the origin from other myeloid disorders, the patient was confirmed directly of CNL with positive mutation finding of the CSF3R gene.

While cutaneous presentation in CNL has been seldom reported, usual manifestations are erythematous to violaceous papules on varying parts of the body. A similar case of CNL without evaluation CSF3R gene mutation revealed red to violaceous plaques on whole body. Gingival hypertrophy or purpura was also reported but these lesions required differential diagnoses with other myeloid malignancies including leukemic vasculitis and malignancy-associated Sweet's syndrome3,7. There are no carefully carried studies regarding cutaneous distinction of LC of CNL.

Interestingly, the present case showed some level of paralleled pattern between hematologic abnormality and cutaneous presentation. As anti-inflammatory regimen including oral systemic steroids was not shown to be effective, direct and a more constant stimulation triggering neutrophilia other than reactive nature was more explanatory regarding this phenomenon. In general, skin manifestations in the context of myeloid malignancy may represent disease progression and often portends a poor prognosis8. The correlations are usually manifested through histopathogic evaluation which also signifies leukemic blastic phase and herald the transformation into acute leukemia in cases of myelodysplastic syndrome8,9,10,11. However, an emphasis on hematologic correlation has been undervalued. The present case underscores the comparative relation between the number of immature leukocytes and its subsequent cutaneous presentation. The nature of this parallelism is usually exhibited in reactive neutrophilic dermatoses such as Sweet's syndrome and pyoderma gangrenosum12,13.

Upon the discovery of CSF3R, cutaneous lesions in consequence to the downstream effects of CSF3R stimulation can be construed. The CSF3R, belonging to the granulocyte-colony-stimulating-factor-receptor, is critical for neutrophils at both steady and granulopoietic states14. Such stimulation were reported to be associated with various cytokines leading to heavy infiltration of neutrophils which resulted in various neutrophilic dermatosis15. Recently, the murine model transplanted with CSF3RT618I-expressing hematopoietic cells was manifested with granulocytic infiltration of the spleen and liver16.

Even though, the precise pathophysiology of genetic role and the distinction between pathogenesis of LC and cutaneous presentations remain to be elucidated, this is the first case to report the lesions of LC in accordance to the revised 2016 WHO criteria associated with the genetic mutation of CSF3R. Previous case of LC in CNL lacked evaluation of CSF3R and the nature of mature segmented neutrophils was not dominant6. As LC in CNL lacks specific clinical distinction, confusing cases demonstrating clinical, hematologic and pathologic correlation may consider the CSF3R gene analysis after all markers of hematologic malignancy fails to reach a diagnosis. Furthermore, elucidation of CSF3R gene analysis limits unnecessary diagnostic measures and inappropriate treatments caused by unwariness of the disease or the diagnosis. Finalized diagnosis with the inclusionary criterion of the gene abnormality with further understanding of the downstream effects may generate a better understanding of the disease and promote sounder treatment options based on causative grounds.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Cronin DM, George TI, Sundram UN. An updated approach to the diagnosis of myeloid leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009;132:101–110. doi: 10.1309/AJCP6GR8BDEXPKHR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li AW, Yin ES, Stahl M, Kim TK, Panse G, Zeidan AM, et al. The skin as a window to the blood: cutaneous manifestations of myeloid malignancies. Blood Rev. 2017;31:370–388. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2017.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elliott MA, Tefferi A. Chronic neutrophilic leukemia 2016: update on diagnosis, molecular genetics, prognosis, and management. Am J Hematol. 2016;91:341–349. doi: 10.1002/ajh.24284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maxson JE, Tyner JW. Genomics of chronic neutrophilic leukemia. Blood. 2017;129:715–722. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-10-695981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian R, Thiele J, Borowitz MJ, Le Beau MM, et al. The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood. 2016;127:2391–2405. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-03-643544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Willard RJ, Turiansky GW, Genest GP, Davis BJ, Diehl LF. Leukemia cutis in a patient with chronic neutrophilic leukemia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44(2 Suppl):365–369. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.103996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elliott MA, Hanson CA, Dewald GW, Smoley SA, Lasho TL, Tefferi A. WHO-defined chronic neutrophilic leukemia: a long-term analysis of 12 cases and a critical review of the literature. Leukemia. 2005;19:313–317. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cho-Vega JH, Medeiros LJ, Prieto VG, Vega F. Leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;129:130–142. doi: 10.1309/WYACYWF6NGM3WBRT. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patel LM, Maghari A, Schwartz RA, Kapila R, Morgan AJ, Lambert WC. Myeloid leukemia cutis in the setting of myelodysplastic syndrome: a crucial dermatological diagnosis. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:383–388. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.05297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Avivi I, Rosenbaum H, Levy Y, Rowe J. Myelodysplastic syndrome and associated skin lesions: a review of the literature. Leuk Res. 1999;23:323–330. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(98)00161-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaddu S, Zenahlik P, Beham-Schmid C, Kerl H, Cerroni L. Specific cutaneous infiltrates in patients with myelogenous leukemia: a clinicopathologic study of 26 patients with assessment of diagnostic criteria. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40(6 Pt 1):966–978. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70086-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rochet NM, Chavan RN, Cappel MA, Wada DA, Gibson LE. Sweet syndrome: clinical presentation, associations, and response to treatment in 77 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:557–564. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen PR, Holder WR, Tucker SB, Kono S, Kurzrock R. Sweet syndrome in patients with solid tumors. Cancer. 1993;72:2723–2731. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19931101)72:9<2723::aid-cncr2820720933>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manz MG, Boettcher S. Emergency granulopoiesis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14:302–314. doi: 10.1038/nri3660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maalouf D, Battistella M, Bouaziz JD. Neutrophilic dermatosis: disease mechanism and treatment. Curr Opin Hematol. 2015;22:23–29. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0000000000000100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fleischman AG, Maxson JE, Luty SB, Agarwal A, Royer LR, Abel ML, et al. The CSF3R T618I mutation causes a lethal neutrophilic neoplasia in mice that is responsive to therapeutic JAK inhibition. Blood. 2013;122:3628–3631. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-06-509976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]