Abstract

Rosacea is a chronic inflammatory skin disease of unknown etiology. We noticed a series of patients who were diagnosed with rosacea as well as obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS), for which they used a continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) mask. This case series aims to give insight in the possible relationship between rosacea and the use of a CPAP mask for OSAS. We present five patients with OSAS who developed or worsened rosacea symptoms after use of a CPAP mask covering nose and mouth. Two patients showed centrofacial symptoms consistent with the shape of the CPAP mask; three patients had nasal cutaneous symptoms. It is postulated that the occlusive effect of the CPAP mask, increasing skin humidity and temperature, can induce primary symptoms in patients with an underlying sensibility for rosacea. This could have implications for choice of CPAP mask type and topical therapeutic options for rosacea.

Keywords: Continuous positive airway pressure, Obstructive sleep apnea, Rhinophyma, Rosacea

INTRODUCTION

Rosacea is a common chronic inflammatory skin disease presenting with erythema, papules, pustules and telangiectasias of predominantly the cheeks, forehead, chin and nose1,2. Four rosacea subtypes are described; erythematotelangiectatic rosacea (ETR), papulopustular rosacea (PPR), phymatous rosacea, and ocular rosacea. The exact pathophysiology of rosacea remains unknown; many factors seem to play a role in disease development3. In addition, it is associated with various chronic systemic diseases, like gastroesophageal reflux disease, and hypertension4. We noticed multiple rosacea patients at our outpatient clinic with concurrent obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS) using a continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) mask. In OSAS, the upper airways collapse repetitively during sleep, causing hypoxia, sleep disruption, and daily fatigue5. A CPAP mask serves as a pneumatic stabilizer in moderate to severe OSAS. Here, we report five patients with rosacea and OSAS with use of a CPAP mask. We propose mechanisms to explain a possible causality between these two entities.

CASE REPORT

Case 1

A 60-year-old female with OSAS, obesity (body mass index, 36.8 kg/m2) and hypertension (for which she was prescribed a thiazide diuretic), experienced sunlight-aggravated periodical facial sensations of burning, tightness, itching, pain, erythema, pustules and periorbital edema since 2010. She also started full-face CPAP ventilation (covering nose and mouth) every night in 2010. Clinical examination in 2016 revealed perioral erythematous papules consistent with the shape of her CPAP mask, and excoriated papules on the cheeks and forehead. Histology showed chronical focal active perivascular and perifollicular infiltrates without signs of contact dermatitis; consistent with rosacea and/or folliculitis. Based on the clinical picture, the diagnosis PPR was made. Previous treatments included topical metronidazole, azelaic acid and ivermectin, and oral tetracyclines, all giving short-term improvement of skin symptoms. She stated that her facial symptoms started after initial use of the mask, with symptom deterioration after prolonged usage. Topical metronidazole application in the evening was difficult because it caused displacement of the CPAP mask and consequently air leakage. After discontinuing CPAP ventilation in 2017 due to the disappearance of apnea complaints caused by substantial weight reduction, symptoms of rosacea improved drastically. Topical ivermectin monotherapy was provided since then.

Case 2

A 61-year-old female with mild OSAS suffered from mild heat-aggravated ETR and PPR since the age of 30. This patient was referred in 2015 because of development of an elevated spot on the right nasal ala. Also in 2015, this patient starting using a full-face CPAP mask every other night. Clinical examination revealed a mildly edematous right nasal ala, and mild erythema and telangiectasias on cheeks and forehead. No papules, pustules or signs of rhinophyma were present. The nasal edema was linked to active rosacea (morbus Morbihan) and expanded to both alae during follow-up in 2016. Treatment with topical metronidazole and azelaic acid and oral tetracyclines were non-effacious; manual lymphatic drainage is currently being considered. Nowadays, this patient is still using the full-face CPAP mask. (Intra)nasal devices were tried but not successful (less effective and painful).

Case 3

A 74 year-old-male with mild-severe OSAS, hypertension and coronary heart disease (for which he was prescribed a statin, angiotensin-converting enzyme [ACE]-inhibitor, thiazide diuretic and a beta-blocker), started using a full-face CPAP mask in 2012. This patient suffered from recurrent nasal inflammation since multiple years with periodical nasal thickening, erythema, pain, and outflow of pus. Symptoms aggravated in 2017. Physical examination in 2018 revealed prominent nasal follicle openings, sebum gland hypertrophy and open comedones, consistent with rhinophyma, together with multiple telangiectasias on the cheeks and forehead. Oral doxycyclin was prescribed, followed by surgical dermabrasion of the nasal skin one month later. This regimen resulted in decrease of nasal pustules and erythema. Metronidazole maintenance therapy was provided one month after surgery. In the same period, CPAP therapy was discontinued due to air leakage and replaced by a mandibular reposition device. The patient could not clearly indicate whether the change of device influenced rhinophyma symptoms.

Case 4

A 59-year-old male with OSAS and hypercholesterolemia (for which no therapy was used) experienced a sunlight-aggravated fatty skin of the nose for approximately 20 years. He used a serotonin-reuptake inhibitor for depression. He started wearing a full-face CPAP mask every night in 2015. Since 2017, small bumps on the nose, roughening of nasal skin and periodical pustules were noticed. Previous topical therapies (corticosteroids, metronidazole) were ineffective. Clinical examination in 2018 revealed diffuse nasal fatty erythema, telangiectasias, pustules and fibrosis, and mild diffuse erythema and yellowish desquamation at the nasolabial folds and eyebrows. Patient's rhinophyma with concurrent seborrheic dermatitis were treated with topical ivermectin and ketoconazol and oral doxycyclin, resulting in improvement of skin symptoms.

Case 5

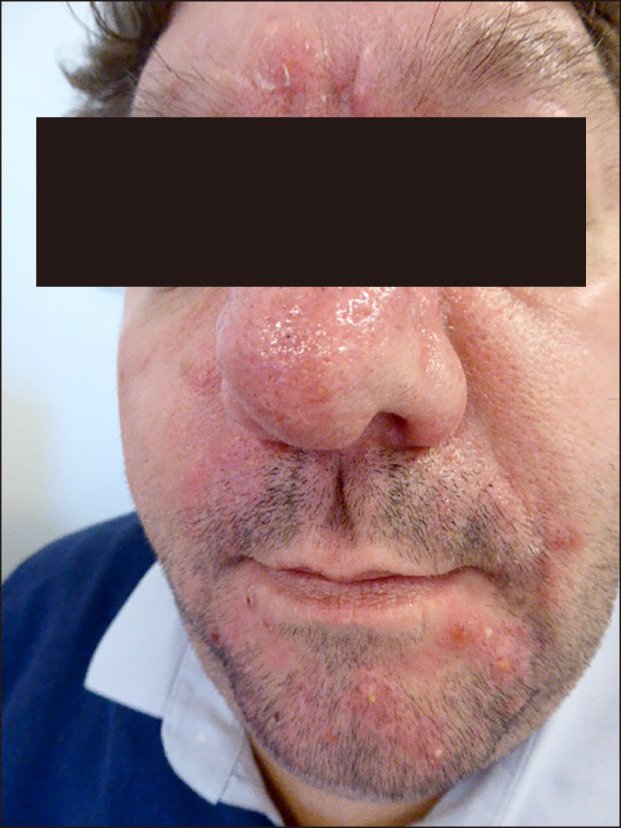

A 48-year-old male with OSAS, obesity, hypertension and diabetes mellitus type 2 (for which he used blood glucose lowering drugs, and a statin, ACE-inhibitor, thiazide diuretic, calcium antagonist, beta-blocker, and low-dose acetylic acid) started using a full-face CPAP mask in 2015. In the same period, symptoms of recurrent pustules, nasal thickening, and dermal inflammation of the perioral region and nose appeared. Clinical examination in 2017 revealed erythema, papules and pustules between the eyebrows, on the nose and in the nasolabial fold; moreover, nasal fibrosis was present. Aforementioned skin symptoms were consistent with the shape of the CPAP mask (Fig. 1). The clinical diagnosis PPR with rhinophyma was made. Initial treatment with topical metronidazole was ineffective; oral tetracyclines reduced skin inflammation thereafter. As nasal fibrosis remained, surgical dermabrasion of nasal skin was performed. He suggested that his skin symptoms were caused by inadequate cleaning of his CPAP mask; nowadays, he cleans his mask more frequently. Moreover, he is actively trying to lose weight.

Fig. 1. Patient with rhinophyma and papulopustular rosacea. Skin symptoms were consistent with the shape of the continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) mask. Informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of the photographic materials.

A summary of the cases is presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Summary of reported cases of rosacea and CPAP mask for OSAS.

| Case | Age/sex | Rosacea type (since) | Mask type (since) | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 60/female | PPR (2010) | Full-face (2010)* | Stopped using CPAP in 2017, rosacea improved since then |

| 2 | 61/female | ETR, morbus Morbihan (2016) | Full-face, nasal, intranasal (2015) | Mild ETR and PPR since 90’s |

| 3 | 74/male | Rhinophyma, mild (2018) | Full-face (2012) | Mild nasal symptoms for several years, stopped using CPAP in 2018 |

| 4 | 59/male | Rhinophyma (2017) | Full-face (2015) | Fatty nasal skin for 20 years |

| 5 | 48/male | PPR, rhinophyma (2015) | Full-face (2015) | Skin symptoms consistent with shape of CPAP mask |

CPAP: continuous positive airway pressure, OSAS: obstructive sleep apnea syndrome, PPR: papulopustular rosacea, ETR: erythematotelangiectatic rosacea. *Covering nose and mouth.

DISCUSSION

We presented five patients with development or worsening of rosacea after use of full-face CPAP masks covering nose and mouth for OSAS. Two patients were diagnosed with PPR, one with ETR with morbus Morbihan and three patients with rhinophyma. Three patients had nasal skin symptoms and two patients showed centrofacial symptoms consistent with the shape of the CPAP mask. Here, several hypotheses are proposed to explain the surprising similarities between our cases.

First, temperature may play a role; a significant higher rosacea frequency was found in females exposed to tandoor heat6. Possibly, full-face CPAP masks cause a warm facial environment, inducing heat-specific transient receptor potential (TRP) receptors on keratinocytes, resulting in inflammation and vasodilatation1,3. Also Demodex mites, part of normal facial skin flora, may be involved in this process, as they seem to play a role in the development of rosacea3. Previous work showed increased immune-stimulatory protein production by Demodex-containing bacteria at higher temperatures7.

Secondly, occlusion could be a factor. A CPAP device is equipped with a humidifier pumping water into the mask to reduce dry mouth and nasal congestion. This water may cause a humid, occlusive layer onto facial skin. This effect can be enhanced by application of topical therapies or bad mask hygiene, resulting in sebum gland obstruction and inducing primary symptoms of an underlying sensibility for rosacea. We therefore advice to apply topical therapies as far as possible before putting on the mask. Furthermore, we recommend patients to follow the general cleaning guidelines for the CPAP apparatus.

Lastly, comorbidities may play a role. OSAS is associated with metabolic syndrome, and diabetes and hypertension are frequent comorbitities8,9. In OSAS patients with those comorbidities, changed cortisole levels and inflammatory mediators have been found that could declare an altered sensitivity for general inflammation10,11. Interestingly, rosacea is also associated with cardiovascular risk factors and metabolic syndrome4,12,13. In our cases, four of five patients had cardiovascular and/or metabolic comorbidities. Possibly, those comorbidities are an important link between CPAP use for OSAS and rosacea.

It is important to note that other co-factors could influence rosacea symptoms. Due to the retrospective character and limited amount of subjects of this report, we did not study those factors in more detail. First, various food components like pepper, alcohol, and hot beverages can aggravate rosacea by upregulating TRP channels1,3,14. Dietary factors did not seem to be of influence in our patients, as skin symptoms diminished after removal of the CPAP mask. Second, photosensitizing medication, e.g., chlorthalidone and metoprolol, could increase rosacea severity. Lastly, contact allergies coexist in rosacea15, but no clinical/histological signs of contact dermatitis were present in our patients. In conclusion, we reported five patients with development or worsening of rosacea symptoms after use of a full-face CPAP mask covering nose and mouth for OSAS. We propose an occlusive effect of the CPAP mask on the skin, increasing skin humidity and temperature, which induces primary symptoms of an underlying sensibility for rosacea. In addition, OSAS and its cardiovascular/metabolic comorbidities could play a role in the development of rosacea symptoms. In future, more attention should be paid to patients who develop rosacea when using CPAP masks. This could have implications for choice of CPAP mask type and topical therapeutic treatment for rosacea.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST: Jade G. M. Logger has received a research grant from Galderma. She carried out clinical trials for Abbvie, Novartis, Janssen and LEO Pharma. Rieke J. B. Driessen has received a research grant from Galderma. She carried out clinical trials for Cutanea Life Sciences, Galderma, Abbvie, Novartis and Janssen. She has received reimbursement for attending meetings from Abbvie and Galderma. She has served as a consultant for Abbvie, Galderma and Novartis. Fees were paid directly to the institution. Malou Peppelman and Roel van Vugt have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Two AM, Wu W, Gallo RL, Hata TR. Rosacea: part I. Introduction, categorization, histology, pathogenesis, and risk factors. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:749–758. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.08.028. quiz 759-760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gallo RL, Granstein RD, Kang S, Mannis M, Steinhoff M, Tan J, et al. Standard classification and pathophysiology of rosacea: the 2017 update by the National Rosacea Society expert committee. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:148–155. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holmes AD, Steinhoff M. Integrative concepts of rosacea pathophysiology, clinical presentation and new therapeutics. Exp Dermatol. 2017;26:659–667. doi: 10.1111/exd.13143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rainer BM, Fischer AH, Luz Felipe da Silva D, Kang S, Chien AL. Rosacea is associated with chronic systemic diseases in a skin severity-dependent manner: results of a case-control study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:604–608. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwartz M, Acosta L, Hung YL, Padilla M, Enciso R. Effects of CPAP and mandibular advancement device treatment in obstructive sleep apnea patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Breath. 2018;22:555–568. doi: 10.1007/s11325-017-1590-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ozkol HU, Calka O, Akdeniz N, Baskan E, Ozkol H. Rosacea and exposure to tandoor heat: is there an association? Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:1429–1434. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dahl MV, Ross AJ, Schlievert PM. Temperature regulates bacterial protein production: possible role in rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:266–272. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2003.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qian Y, Xu H, Wang Y, Yi H, Guan J, Yin S. Obstructive sleep apnea predicts risk of metabolic syndrome independently of obesity: a meta-analysis. Arch Med Sci. 2016;12:1077–1087. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2016.61914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hopps E, Caimi G. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: links betwen pathophysiology and cardiovascular complications. Clin Invest Med. 2015;38:E362–E370. doi: 10.25011/cim.v38i6.26199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karaca Z, Ismailogullari S, Korkmaz S, Cakir I, Aksu M, Baydemir R, et al. Obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome is associated with relative hypocortisolemia and decreased hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis response to 1 and 250µg ACTH and glucagon stimulation tests. Sleep Med. 2013;14:160–164. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2012.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sozer V, Kutnu M, Atahan E, Calıskaner Ozturk B, Hysi E, Cabuk C, et al. Changes in inflammatory mediators as a result of intermittent hypoxia in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Clin Respir J. 2018;12:1615–1622. doi: 10.1111/crj.12718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akin Belli A, Ozbas Gok S, Akbaba G, Etgu F, Dogan G. The relationship between rosacea and insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome. Eur J Dermatol. 2016;26:260–264. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2016.2748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duman N, Ersoy Evans S, Atakan N. Rosacea and cardiovascular risk factors: a case control study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:1165–1169. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weiss E, Katta R. Diet and rosacea: the role of dietary change in the management of rosacea. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2017;7:31–37. doi: 10.5826/dpc.0704a08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diczig B, Németh I, Sárdy M, Pónyai G. Contact hypersensitivity in rosacea - a report on 143 cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:e347–e349. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]