Abstract

Background

Eccrine porocarcinoma (EPC) is a rare malignant cutaneous adnexal tumor. Other than several scattered case reports, no comprehensive review on EPC has been conducted in Korea.

Objective

To clinicopathologically review all EPC cases from our institutions as well as those reported in Korea.

Methods

Medical records and histopathological slides of EPC cases in the skin biopsy registries of our institutions were retrospectively reviewed. Additionally, EPC cases reported in Korea before June 2019 were retrieved by searching the PubMed, KoMCI, KoreaMed, and KMbase databases.

Results

Nine EPC cases from our institutions were included in the study. In addition, 27 reports of 28 patients with EPC were reported in Korea. A total of 37 patients with EPC were identified, consisting of 19 males (male:female ratio, 1.06:1; mean age at diagnosis, 65.6 years). The most common site of primary tumor was the head and neck (29.7%). Wide excision was the most common (78.4%) treatment method. Initial metastasis work-up imaging studies were performed in 18 patients (48.6%), and metastasis was confirmed in eight patients (21.6%).

Conclusion

EPC is a rare cutaneous carcinoma in Korea. EPC usually affects elderly patients, with no sexual predilection. Due to possible metastasis, careful diagnosis and appropriate metastasis work-ups are warranted in EPC.

Keywords: Eccrine porocarcinoma, Malignant eccrine poroma, Porocarcinoma

INTRODUCTION

Eccrine porocarcinoma (EPC) is a rare malignant cutaneous adnexal tumor1,2. The reported frequency of EPC is 0.005% to 0.01% of all cutaneous tumors, making it the most common malignant eccrine tumor3. Since EPC is notoriously known for being mis- or overdiagnosed, its actual prevalence remains unknown1. It can arise de novo or from long-standing pre-existing eccrine poroma (EP)2,4. Chronic light exposure and immunosuppression have been suggested as factors that contribute to the transformation of EP to EPC2. Malignant transformation is often heralded by spontaneous bleeding, ulceration, itching, pain, and sudden growth5.

According to a recent systematic review of 206 cases, which included only two Korean patients, the mean age at diagnosis was 63.6 years, and EPC occurred in both sexes equally2. The most common location was the lower limbs (33%), followed by the head and neck (32%)2. Since the two official case reports in 19986,7, only scattered reports of EPC have been made in Korea, and no overall review has been conducted. This study aimed to comprehensively review EPC cases in Korea.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Multicenter retrospective study: patient and data collection

The skin biopsy registries of department of dermatology at three university hospitals (Korea University Anam, Guro, and Ansan Hospital) were searched for patients with EPC from January 2000 to June 2019. Medical records and clinical photographs were reviewed retrospectively. Data on patient age, sex, tumor location, tumor size, duration, clinical impression, metastasis work-up imaging studies, surgical methods with results, follow-up duration, and any pre-existing lesions were identified. All available histopathological slides were re-examined by an experienced dermatopathologist (AK). EPC is diagnosed when a proliferation of medium-sized cells with intercellular bridges, duct formation (including intracytoplasmic ducts), nuclear atypia, increased mitoses, and apoptosis are observed5. For the histopathological review, the following features were evaluated: mature duct formation, necrosis (comedonecrosis or diffuse necrosis), melanocytic colonization, squamous/clear cell/spindle cell/mucus cell differentiation, associated benign components, mitotic counts, perineural/lymphovascular invasion, and immunohistochemistry results.

Review of the literatures in Korea: search strategy and data collection

Two authors (HJK, YSB) searched for reports of EPC in Korea before June 2019 in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement guidelines. Literatures were searched in the PubMed, KoMCI, KoreaMed, and KMbase databases. The search terms were “porocarcinoma” and “malignant eccrine poroma.”

Two authors (HJK, YSB) independently assessed the eligibility of each study. Any type of study from Korea in English or Korean regarding EPC was initially included. The following were excluded: 1) any studies without information on the individual patient or tumor characteristics; 2) cases with collision of EPC and other carcinomas; 3) in situ cases. Data on patient age, sex, primary tumor site, initial metastasis work-up imaging studies, confirmed metastasis (lymph node or distant), treatment method with results, and any associated benign lesion were collected from the literature. Since this literature search identified only case studies, we were unable to assess the risk of bias of individual studies.

Ethics

All clinical investigations were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki principles. This study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Korea University Medical Center (K2019-1634-001). Requirement of informed consent was waived by the IRB. However, we received the patient's consent form about publishing all photographic materials.

RESULT

Multicenter retrospective study

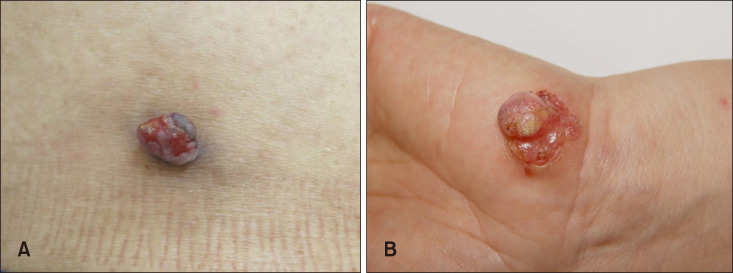

Nine patients with EPC were identified through the skin biopsy registries (Supplementary Table 1, Fig. 1)8,9,10. Among them, three cases8,9,10 have already been reported in the literature, consisting of five males (male:female ratio 1.25:1), and the mean age at diagnosis was 65.9±16.0 years. The most common tumor site was the head and neck (3 patients). Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) was the most common clinical impression, and EPC was not initially suspected in all cases. Interestingly, all patients had a unique clinical history indicating that the lesion had persisted for several years and had changed recently (bleeding, size growth, or ulceration). Five patients had metastasis work-up imaging studies. However, none had metastatic disease. Two patients were treated with Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS), and the remaining patients underwent wide excision.

Fig. 1. Representative clinical examples of eccrine porocarcinoma. (A) Case 1, a 61-year-old male patient with an erythematous erosive pedunculated mass on the right flank. (B) Case 5, a 62-year-old male patient with an erythematous protruding nodule on the left palm.

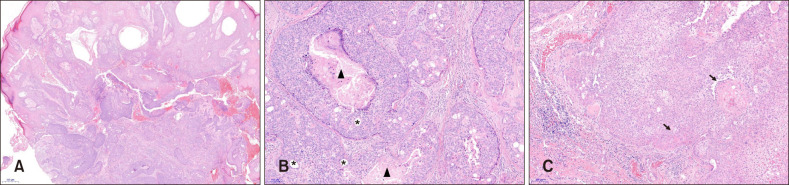

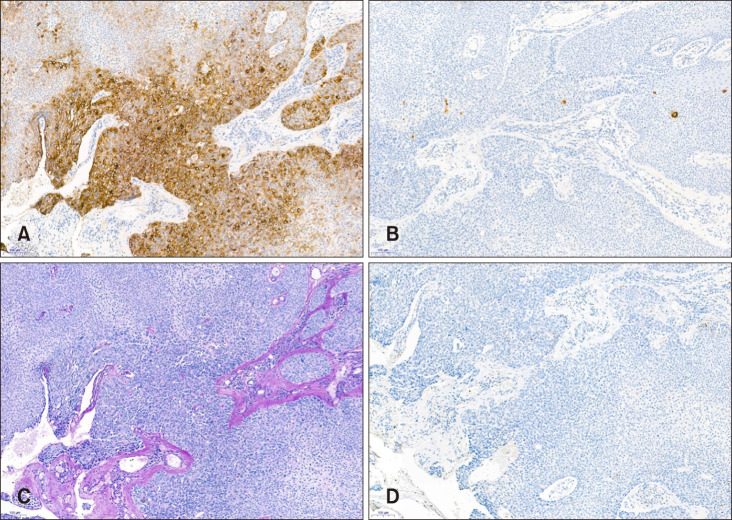

In the histopathological review, mature duct formation (66.7%), necrosis (66.7%), and squamous differentiation (55.6%) were common findings (Fig. 2). In contrast, melanocytic colonization (22.2%) and clear cell differentiation (11.1%) were observed less often. No spindle cell differentiation, mucus cell differentiation, or perineural or lymphovascular invasion were observed in our case series. Associated benign components were found in 77.8% of our series, with EP as the most common (Table 1). Mitotic counts ranged from 3 to 22 mitoses per high-power field. Five patients underwent additional immunohistochemical stains. Epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) and periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stains were positive in four patients. Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) also tested positive in three patients, whereas S-100 in three patients was all negative (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2. Representative histopathological features of eccrine porocarcinoma. (A) Note the infiltrative irregularly shaped basaloid tumor nests (H&E, original magnification: ×20). (B) Cellular pleomorphism, mature duct formation (asterisks), and comedonecrosis (black arrowheads) can be noted in a high-power field (H&E, original magnification: ×100). (C) Squamous differentiation (black arrows) was also noted (H&E, original magnification: ×100).

Table 1. Summary of histopathological features of nine patients with eccrine porocarcinoma (EPC) from our institutions.

| Histopathological feature | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Mature duct formation | 6 (66.7) |

| Necrosis (comedonecrosis/diffuse necrosis) | 6 (66.7) |

| Melanocytic colonization | 2 (22.2) |

| Differentiation | |

| Squamous | 5 (55.6) |

| Clear cell | 1 (11.1) |

| Spindle cell | 0 (0) |

| Mucus cell | 0 (0) |

| Associated benign component | |

| Eccrine poroma | 5 (55.6) |

| Hidroacanthoma simplex | 1 (11.1) |

| Epidermal nevus | 1 (11.1) |

| Perineural invasion | 0 (0) |

| Lymphovascular invasion | 0 (0) |

Fig. 3. Representative immunohistochemical staining results of eccrine porocarcinoma. (A) Epithelial membrane antigen staining showed focal positivity within the tumors nests as well as ductal differentiation (original magnification: ×100). (B) Carcinoembryonic antigen staining highlightened ductal formation (original magnification: ×100). (C) The presence of ducts was also shown in periodic acid-Schiff with diastase staining (original magnification: ×100). (D) The tumor cells showed negative staining for S-100 (×100).

Review of the literatures in Korea

The initial search revealed 524 articles after removing duplications. After a screening process, 38 articles from Korea regarding EPC were assessed for eligibility in full-text. However, eight articles were excluded because they met the exclusion criteria (Supplementary Fig. 1). As a result, 30 articles were included in the study. Since three reports8,9,10 were from our institutions and were previously included in the multicenter retrospective study, 27 reports of 28 patients with EPC were analyzed in this section (Supplementary Table 2)6,7,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35. Twenty-six patients presented with a primary skin lesion. The other two presented with symptoms of metastatic lesions (one with mental change and the other with dyspnea). There were 14 males (male:female ratio 1:1), with a mean age at diagnosis of 65.5±16.6 years. The most common site for primary tumors was the head and neck (8 patients) and trunk (8 patients), followed by the lower limb (seven patients). Thirteen patients had initial metastasis work-up imaging studies. The majority of patients were initially managed with wide excision. Other treatment methods included partial excision, chemotherapy, and palliative care. Metastasis was eventually diagnosed in eight patients (six during initial work-up, and two during the follow-up period at three months and 17 months, respectively). Six patients had distant and regional lymph node metastases. Associated benign lesions were EP (5 patients), hidroacanthoma simplex (2 patients), seborrheic keratosis (1 patient), and ganglion cyst (1 patient).

Summary of 37 cases

Combining nine cases from our institutions and 28 from the literature search, a total of 37 patients with EPC were analyzed, which consisted of 19 males (male:female ratio 1.06:1), with a mean age at diagnosis of 65.6±16.4 years. The most common site for a primary tumor was the head and neck (11 patients, 29.7%), followed by the trunk (10 patients, 27.0%) and lower limb (9 patients, 24.3%). Initial metastasis work-up imaging studies were performed in 18 patients (48.6%). Wide excision was the most common surgical method (29 patients, 78.4%). Among them, only three patients (8.1%) underwent lymph node dissection (LND), and none underwent a sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB). MMS was performed in two patients (5.4%). Adjuvant radiation therapy was initiated in three patients (8.1%; two after wide excision and one after partial excision). One patient (2.7%) had adjuvant chemotherapy after wide excision and LND. Metastasis was confirmed in eight patients (21.6%). The most common metastatic site was the regional lymph node (8 patients), followed by the lung (5 patients) and bone, including the spine (3 patients). Associated benign lesions were found in 16 patients (43.2%), with EP (27.0%) as the most commonly found (Table 2).

Table 2. Summary of characteristics of 37 patients with eccrine porocarcinoma included in the present study.

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Sex (male:female) | 1.06:1 |

| Age at diagnosis (yr) | 65.6±6.4 |

| Primary tumor site | |

| Head and neck | 11 (29.7) |

| Trunk | 10 (27.0) |

| Lower limb | 9 (24.3) |

| Upper limb | 4 (10.8) |

| Pelvis | 3 (8.1) |

| Metastasis work-up imaging study* | |

| CT | 11 (29.7) |

| PET-CT | 7 (18.9) |

| MRI | 3 (8.1) |

| None | 19 (51.4) |

| Initial management | |

| Wide excision | 24 (64.9) |

| Wide excision and adjuvant radiation therapy | 2 (5.4) |

| Wide excision and lymph node dissection | 2 (5.4) |

| Wide excision, lymph node dissection, and adjuvant chemotherapy | 1 (2.7) |

| Mohs micrographic surgery | 2 (5.4) |

| Others | 6 (16.2) |

| Metastasis | |

| Regional lymph node metastasis only | 2 (5.4) |

| Distant metastasis with regional lymph node involvement | 6 (16.2) |

| Associated benign lesion | |

| Eccrine poroma | 10 (27.0) |

| Hidroacanthoma simplex | 3 (8.1) |

| Seborrheic keratosis | 1 (2.7) |

| Epidermal nevus | 1 (2.7) |

| Ganglion cyst | 1 (2.7) |

Values are presented as ratio, mean±standard deviation, or number (%). CT: computed tomography, MRI: magnetic resonance imaging, PET-CT: positron emission tomography-computed tomography. *Some patients had combination of imaging studies.

DISCUSSION

In this study, EPC in Korea affected both sexes equally, with a mean age of 65.6 years. The most common primary locations of EPC are known to be the lower extremities and head and neck, with upper extremities as the least common sites2. However, in our study, EPC in Korea most commonly occurred on the head and neck, followed by the trunk.

Due to its polymorphous presentation and rarity, it is generally difficult to suspect EPC as initial clinical diagnosis. For instance, none of patients with EPC in our institutions were clinically suspected as having EPC before biopsy, but were considered to have “SCC”, “pyogenic granuloma”, or “EP”. The clinical clue for EPC is a long-term history of a previously benign-looking lesions with recent secondary changes (size growth, bleeding, or ulceration). A prudent histopathological evaluation including immunohistochemical staining of EPC is therefore mandatory. Since a substantial percentage of EPC shows squamous differentiation, SCC is the most important differential diagnosis5,36. In fact, >50% of patient with EPC from our institutions showed squamous differentiation, which is a higher percentage compared with previous studies (5%~42%)4,36,37. Mature duct formation, identified as the presence of ducts lined by cuboidal epithelial cells commonly with an eosinophilic cuticle, was found in 66.7% of our patients with EPC, which is similar to the findings of previous studies (62%~68%)4,36. This characteristic is considered a significant indicator for a diagnosis of EPC4. However, caution is needed not to overlook the possibility of a poorly differentiated EPC that may not have easily recognizable mature ducts, but only less well-developed ducts4,37. Immunohistochemical staining is necessary when EPC diagnosis is unclear37. CEA, EMA, and PAS, which highlight ductal differentiation foci, are commonly performed2,36. However, careful interpretation is required, because some SCC can be positive for these stains36. EP is another important differential diagnosis of EPC. Invasive architectural patterns and significant cytological pleomorphisms are important findings that distinguish EPC from EP4,37.

As for the metastasis work-up, 48.6% of EPC patients in Korea had undergone imaging studies, with computed tomography as the most common. Metastasis eventually occurred in 21.6% of patients with EPC in Korea. Most of them were found initially; however, two metastases were found during the follow-up period (3 and 17 months). This is consistent with the results of recent studies demonstrating that approximately 20% to 30% of EPC patients had metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis2,38. Also consistent with a previous study, the most common metastatic site of EPC was the regional lymph node followed by the lungs38. Due to a relatively high risk of metastasis, we recommend initial imaging studies as work-up for EPC metastasis.

The majority of patients with EPC in Korea were managed with a surgical wide excision. Only two patients were managed with MMS, whereas 20% of patients worldwide are treated with MMS2. Recent studies highlight the advantages of MMS for EPC over a wide excision with fewer metastases (2.4% vs. 18%)1,2,5. LND was performed in 8.1% of Korean patients with EPC. Although none of patients with EPC in Korea underwent SLNB, it was performed in 16 patients with EPC worldwide, achieving an 81.3% positive rate2. Therefore, SNLB can also be considered in patients with EPC who are highly at risk for metastasis without palpable lymphadenopathy.

Chemotherapy and radiation therapy are less effective for EPC and are usually reserved for metastatic diseases. In this study, only three patients received chemotherapy, which was administered as an initial management (combination of 5-fluorouracil [5-FU] and cisplatin)19, adjuvant chemotherapy (5-FU)6, or management after the recurrence and metastasis (5-FU→adriamycin→paclitaxel)18. Radiation therapy was used as an adjuvant therapy7,17,18, for palliative care18,24, or for management of regional lymph node metastasis11.

Associated benign components (EP, hidroacanthoma simplex, seborrheic keratosis, epidermal nevus, and ganglion cyst) were noted in 43.2% of 37 patients with EPC. This rate is much higher than that reported in two studies (12% and 18%)4,36. The most common concomitant benign tumor was EP (27.0%), indicating that a substantial proportion of EPCs are malignant transformation of EP. In addition to the present study, EPC has been reported to arise within seborrheic keratosis39,40,41,42,43 or epidermal nevus44. Although malignant transformation of these benign lesions is rare, dermatologists should be aware of the possibility. However, caution is necessary when diagnosing ‘EPC arising from seborrheic keratosis’. It is possible to misdiagnose hidroacanthoma simplex as clonal seborrheic keratosis, especially when the lesion is pigmented and cystic or ductal structure is not definite. It might be reasonable to make a diagnosis of hidroacanthoma simplex rather than seborrheic keratosis if the lesion coexists with one of poroid neoplasms such as EPC45.

In conclusion, EPC is a rare cutaneous adnexal tumor in Korea, found in only 37 cases in our institutions' data and literature search. EPC usually affects the elderly without sexual predilection. Although a wide excision was most commonly used to treat EPC in Korea, MMS can also be a useful alternative surgical method, considering recent studies showing its advantages over wide excision. Metastasis was eventually confirmed in 21.6% of patients with EPC. Due to the possibility of EPC metastasis, careful diagnosis and appropriate initial imaging studies are warranted.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was supported by a Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF-2018R1D1A1B07045088).

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST: The authors have nothing to disclose.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary data can be found via http://anndermatol.org/src/sm/ad-32-223-s001.pdf.

Clinical characteristics of nine patients with eccrine porocarcinoma from our institutions

Flow diagram of the searching strategy and results.

Clinical characteristics of 28 eccrine porocarcinoma cases reported in Korea

References

- 1.Xu YG, Aylward J, Longley BJ, Hinshaw MA, Snow SN. Eccrine porocarcinoma treated by Mohs micrographic surgery: over 6-year follow-up of 12 cases and literature review. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:685–692. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000000382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nazemi A, Higgins S, Swift R, In G, Miller K, Wysong A. Eccrine porocarcinoma: new insights and a systematic review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:1247–1261. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000001566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mehregan AH, Hashimoto K, Rahbari H. Eccrine adenocarcinoma. A clinicopathologic study of 35 cases. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:104–114. doi: 10.1001/archderm.119.2.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robson A, Greene J, Ansari N, Kim B, Seed PT, McKee PH, et al. Eccrine porocarcinoma (malignant eccrine poroma): a clinicopathologic study of 69 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:710–720. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200106000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tolkachjov SN, Hocker TL, Camilleri MJ, Baum CL. Treatment of porocarcinoma with Mohs micrographic surgery: the Mayo Clinic experience. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:745–750. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000000763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park JJ, Choi YH, Choi KC, Park YE. Malignant eccrine poroma of abdomen brief case report. Korean J Pathol. 1998;32:312–314. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim JS, Ro YS, Park CK. A case of malignant eccrine poronta. Korean J Dermatol. 1998;36:717–721. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yoon HS, Seo SH, Kim AR, Kye YC. A case of eccrine porocarcinoma. Korean J Dermatol. 2001;39:1310–1312. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shin JB, Ko NY, Seo SH, Kim A, Kye YC, Kim SN. A case of eccrine porocarcinoma on the scalp. Korean J Dermatol. 2006;44:1084–1087. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jeon J, Kim JH, Baek YS, Kim A, Seo SH, Oh CH. Eccrine poroma and eccrine porocarcinoma in linear epidermal nevus. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:430–432. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0000000000000012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seo BF, Choi HJ, Jung SN. Eccrine porocarcinoma on the cheek. Arch Craniofac Surg. 2019;20:48–50. doi: 10.7181/acfs.2018.02180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park IH, Kim TH, Kwon ST, Park JU. Porocarcinoma arising in a ganglion cyst: a case report and review of the literature. Arch Reconstr Microsurg. 2016;25:56–59. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim SM, Lee JB, Lee SC, Won YH, Yun SJ, Kim SJ. Pigmented eccrine porocarcinoma. Korean J Dermatol. 2014;52:574–579. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jeon SP, Kang SJ, Jung SJ. Rapidly growing eccrine porocarcinoma of the face in a pregnant woman. J Craniofac Surg. 2014;25:715–717. doi: 10.1097/01.scs.0000436739.52418.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choi SH, Kim YJ, Kim H, Kim HJ, Nam SH, Choi YW. A rare case of abdominal porocarcinoma. Arch Plast Surg. 2014;41:91–93. doi: 10.5999/aps.2014.41.1.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee KT, Kim JH, Park SW, Shin HT, Yang JM, Lee JH, et al. Pedunculated eccrine porocarcinoma. Korean J Dermatol. 2013;51:196–198. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim WH, Kim JT, Park CK, Kim YH. Successful reconstruction after resection of malignant eccrine poroma using retroauricular artery perforator-based island flap. J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23:e579–e582. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e31826befbb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee JH, Lim JH, Kim L, Kim CS, Yi HG, Nah SY, et al. A case of metastatic eccrine porocarcinoma with a review of the literatures. Korean J Head Neck Oncol. 2011;27:222–225. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choi CM, Cho HR, Lew BL, Sim WY. Eccrine porocarcinoma presenting with unusual clinical manifestations: a case report and review of the literature. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23 Suppl 1:S79–S83. doi: 10.5021/ad.2011.23.S1.S79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hong YJ, Oh JE, Choi YW, Myung KB, Choi HY. A case of clear cell eccrine porocarcinoma. Ann Dermatol. 2010;22:330–332. doi: 10.5021/ad.2010.22.3.330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choi YJ, Lee GY, Kim WS, Kim KJ. A case of eccrine porocarcinoma that showed squamous differentiation on the palm. Korean J Dermatol. 2009;47:861–864. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Choi SM, Kim CH, Kang SG, Tark MS, Park SM, Jin SY. A case of eccrine porocarcinoma on back. J Korean Soc Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;35:99–102. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park J, Kwon H, Cho MK, Park YL, Lee SY, Lee JS, et al. A case of malignant eccrine poroma developing on the suprapubic area. Ann Dermatol. 2008;20:37–40. doi: 10.5021/ad.2008.20.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim JW, Oh DJ, Kang MS, Lee D, Hwang SW, Park SW. A case of metastatic eccrine porocarcinoma. Acta Derm Venereol. 2007;87:550–552. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oh SH, Lee WJ, Chang SE, Lee MW, Choi JH, Moon KC, et al. Two cases of eccrine porocarcinoma. Korean J Dermatol. 2007;45:503–506. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee YH, Kim SH, Suh MK, Park SK, Jang TJ. Malignant eccrine poroma of the left upper eyelid resembling cutaneous horn. Korean J Dermatol. 2006;44:1469–1471. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cho SB, Roh MR, Yun M, Yun SK, Lee MG, Chung KY. (18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography detection of eccrine porocarcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:372–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park YK, Kim MO, Park SS, Shin DH, Yoon HJ, Sohn JW, et al. A case of lung metastasis of malignant eccrine poroma. Korean J Med. 2004;66:302–306. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee JB, Oh CK, Jang HS, Kim MB, Jang BS, Kwon KS. A case of porocarcinoma from pre-existing hidroacanthoma simplex: need of early excision for hidroacanthoma simplex? Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:772–774. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.2003.29195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim HJ, Kim JR, Kim YW, Burm JS, Cho MS. Case report of malignant eccrine poroma on lower abdomen. J Korean Soc Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;30:664–667. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim YJ, Kim CW, Kim SY, Kim SS, Huh D, Lee JJ. A Case of malignant eccrine poroma. Korean J Dermatol. 2002;40:442–444. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Han KS, Choi JY, Min HG, Kim JM. A case of malingant eccrine poroma. Korean J Dermatol. 2001;39:247–250. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee JH, Ahn SK, Lee ES, Lee SH. Eccrine porocarcinoma associated with seborrheic keratosis. Korean J Dermatol. 2001;39:101–103. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee HJ, Jeong SH, Seo EJ, Ha SJ, Kim JW. Melanocyte colonization associated with malignant transformation of eccrine poroma. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:582–583. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.03070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jung DY, Bae JH, Lee SK, Lee WW. A case of malignant eccrine poroma. Korean J Dermatol. 1999;37:660–664. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mahalingam M, Richards JE, Selim MA, Muzikansky A, Hoang MP. An immunohistochemical comparison of cytokeratin 7, cytokeratin 15, cytokeratin 19, CAM 5.2, carcinoembryonic antigen, and nestin in differentiating porocarcinoma from squamous cell carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 2012;43:1265–1272. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2011.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Riera-Leal L, Guevara-Gutiérrez E, Barrientos-García JG, Madrigal-Kasem R, Briseño-Rodríguez G, Tlacuilo-Parra A. Eccrine porocarcinoma: epidemiologic and histopathologic characteristics. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:580–586. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Salih AM, Kakamad FH, Baba HO, Salih RQ, Hawbash MR, Mohammed SH, et al. Porocarcinoma; presentation and management, a meta-analysis of 453 cases. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2017;20:74–79. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2017.06.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johr R, Saghari S, Nouri K. Eccrine porocarcinoma arising in a seborrheic keratosis evaluated with dermoscopy and treated with Mohs' technique. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:653–657. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2003.01779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lozano Orella JA, Valcayo Peñalba A, San Juan CC, Vives Nadal R, Castro Morrondo J, Tuñon Alvarez T. Eccrine porocarcinoma. Report of nine cases. Dermatol Surg. 1997;23:925–928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Madan V, Cox NH, Gangopadhayay M. Porocarcinoma arising in a broad clonal seborrhoeic keratosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:350–351. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2007.02659.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hoshina D, Akiyama M, Hata H, Aoyagi S, Sato-Matsumura KC, Shimizu H. Eccrine porocarcinoma and Bowen's disease arising in a seborrhoeic keratosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007;32:54–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2006.02260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miura K, Namiki T, Otsuki Y, Yokozeki H. Porocarcinoma with hidroacanthoma simplex-like features in association with seborrheic keratosis. Eur J Dermatol. 2017;27:405–406. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2017.3013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hamanaka S, Otsuka F. Multiple malignant eccrine poroma and a linear epidermal nevus. J Dermatol. 1996;23:469–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.1996.tb04057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu HN, Chang YT, Chen CC. Differentiation of hidroacanthoma simplex from clonal seborrheic keratosis--an immunohistochemical study. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004;26:188–193. doi: 10.1097/00000372-200406000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Clinical characteristics of nine patients with eccrine porocarcinoma from our institutions

Flow diagram of the searching strategy and results.

Clinical characteristics of 28 eccrine porocarcinoma cases reported in Korea