Abstract

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is an autoimmune disorder characterized by the fibrosis of skin, heart, lung, and kidney as well. Excessive activation of fibroblasts is associated with higher expression of Notch1 and/or Notch3 genes. The constitutive expression of NOTCH genes was described in epithelial cells: epidermal keratinocytes, hair follicle cells and sebaceous glands. The NOTCH signalling pathway may be involved in the development of fibrosis, myofibroblast formation and the process of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Activation of the NOTCH pathway leads to morphological, phenotypic and functional changes in epithelial cells. Furthermore, inhibition of Notch signalling prevent the development of fibrosis in different models, among them, bleomycin-induced fibrosis and in the Task-1 mause model. Molecular mechanisms, including the role of NOTCH signaling pathway, associated with fibrosis in SSc have not been completely recognized.

Keywords: Fibrosis, NOTCH genes, NOTCH pathway, Scleroderma, systemic, Transforming growth factor beta

INTRODUCTION

Fibrosis is often accompanied by repair and/or remodelling of tissues, activation of fibroblasts, formation of myofibroblasts and increase in the volume of extracellular matrix (ECM)1,2. Progressive interstitial and perivascular fibrosis is observed in systemic sclerosis (scleroderma, SSc)3. SSc is classified into limited SSc (lcSSc) and diffuse SSc (dcSSc) forms. Both types differ in the extent of cutaneous involvement, in which fibroblasts produce significant amounts of collagen (type I, III, VI, and VII)4. In lcSSc fibrosis is restricted to skin on fingers, digital extremities and face. Whereas in dcSSc are also affected truncal and peripheral skin areas, as well as visceral organs including interstitial lung disease (ILD), scleroderma renal crisis (SRC), gastrointestinal disease and myocardial involvement5.

Increased fibrosis of the skin and visceral organs leads to progression of SSc3. NOTCH signalling pathway may be involved in the development of fibrosis6,7,8,9. Nowadays there are no clinical trials to treat SSc/fibrosis by modulating NOTCH pathway.

NOTCH PATHWAY

In mammals, the NOTCH pathway is conservative and consists of four receptors (NOTCH 1∼4) and five ligands: delta-like 1, 3, and 4 (DLL-1, 3, 4) and Jagged 1 and 2 (JAG-1, 2)10. The proteins DLL and JAG can effect on NOTCH receptors by cis-(synthesis of the ligand and receptor occurs in the same cell) or trans-interaction (the ligand and receptor are synthesized by different cells)11. Post-translational modifications may have a major impact on the function of NOTCH pathway proteins. Biochemical processes, like glycosylation and/or phosphorylation, may determine the specificity of a receptor to a ligand, and vice versa12. Post-translational modifications of NOTCH receptors occur in the endoplasmic reticulum. Appropriately modified receptor proteins are cut in the Golgi apparatus and transported in the form of heterodimer to the cell membrane13. Each receptor consists of three domains: extracellular, transmembrane and intracellular12,14. The ligand binding domain involves the epidermal growth factor (EGF)-like repeats, which are present in the extracellular domain14,15.

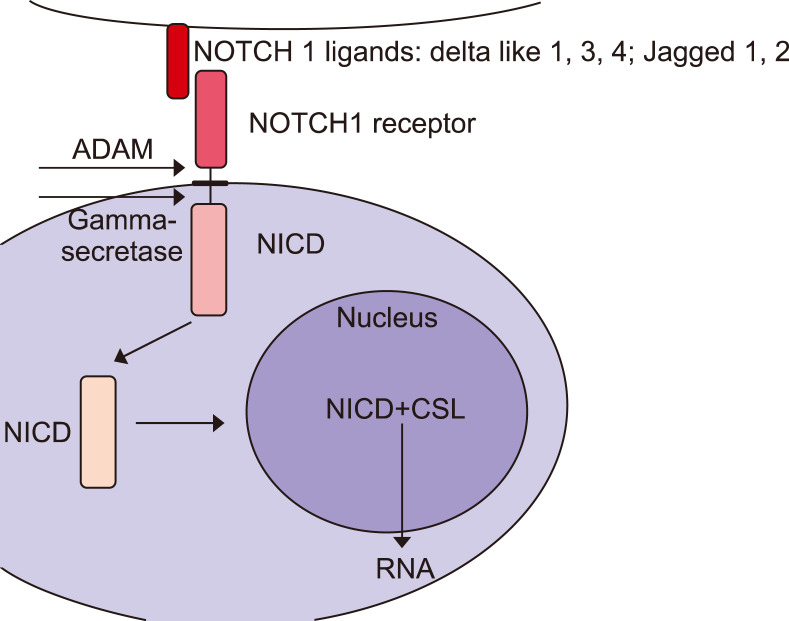

Once attached to the ligand, the NOTCH receptors are subject to cleavage catalysed by the metalloproteinase A Digestirn and Metalloproteinase 17 and γ-secretase. This causes the disconnection of the NOTCH intracellular domain (NICD), which is transferred into the cell nucleus, joins with the transcription factor-CSL (C-repeat/DRE binding factor 1 [CBF1]/suppressor of hairless/Lag1) and inhibits or stimulates the expression of target genes (Fig. 1)7,13. The CSL protein is a suppressor of transcription, while its connection to NICD results in the activation of RNA synthesis16. Low or no NICD expression is observed in normal skin fibroblasts. Its constitutive expression was described in epithelial cells: epidermal keratinocytes, hair follicle cells and sebaceous glands17,18,19,20.

Fig. 1. Cross-talk between NOTCH and transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) pathways. Activation of NOTCH receptors by ligand binding causes the cleavage by an A Digestirn and Metalloproteinase 17 (ADAM) metalloprotease (α-secretase) producing the Notch extracellular truncation fragment. Another cleavage by γ-secretase of transmembrane fragment releases the NOTCH intracellular domain (NICD). It translocates to the nucleus and acts as a co-transcription factor in association with the CSL (C-repeat/DRE binding factor 1/suppressor of hairless/Lag1) and other transcription factors including SMAD3. This protein translocates to the nulceus in the phosphorylated form as a result of TGF-β receptor activation.

The NOTCH pathway regulates the final stage of epidermal cells differentiation and maintains the homeostasis of hair follicle cells17,18,19. In the mouse, Notch1-deficient embryos show severe vascular developmental defects, which are more severe in double mutant Notch1 and Notch4 embryos21.

SYSTEMIC SCLEROSIS

The activation of the NOTCH pathway is observed under physiological conditions, like organogenesis, and has been described in the pathogenesis of diseases associated with abnormal fibrosis, including the development of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, kidney fibrosis and SSc22,23,24,25. NOTCH pathway has an effect on cell differentiation, proliferation, survival and apoptosis22.

Abnormal microcirculation, fibrosis, as well as, autoimmune inflammatory processes are observed in SSc26,27. Perivascular inflammation reduces vascular density, and later the ECM accumulates27,28. A positive correlation between the number of T lymphocytes and the NOTCH1 gene expression in endothelial fibroblasts was found29. The differentiation of T-helper cells (Th) is affected by the NOTCH pathway ligands, including JAG-1 and JAG-2, which stimulate the immune response with Th2 cells, while DLL proteins, predominantly DLL-4, are responsible for the activation of Th1 cells4. It is assumed, that the direct interaction between T-cells expressing JAG-1 and fibroblasts showing high expression of the NOTCH1 receptor may be the main mechanism of the NOTCH pathway activation in SSc8. For example overexpression of JAG-1, Notch ligand, is observed is SSc skin and in hypertrophic scars. It induces an accumulation of NICD in SSc fibroblasts following higher expression of genes whose products are involved in fibroblast activation and collagen release24.

MYOFIBROBLAST FORMATION

The phenotype of myofibroblasts is typical for fibroblasts and smooth muscle cells30. Myofibroblasts show increased expression of collagen type I and III collagen, α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) and lower expression of genes encode ECM-degrading enzymes31,32.

Myofibroblasts synthesize the largest amounts of ECM in tissues, where the repair or remodelling process takes place33. If the repair is completed and these cells do not enter the apoptosis, then the remaining myofibroblasts may cause scarring and fibrosis development33.

The myofibroblasts can originate from various cells, including bone marrow fibrocytes, pericytes, perivascular fibroblasts, white adipocytes, vascular endothelial cells, cholangiocytes and hepatocytes29,34,35,36,37,38. Moreover, Dees et al.24 demonstrated that the stimulation of normal fibroblasts with recombinant human Jag-1-Fc chimera leads to a change in their phenotype, increased collagen release, differentiation of resting fibroblasts into myofibroblasts and further for development of fibrosis.

EPITHELIAL-MESENCHYMAL TRANSITION

The differentiation of epithelial cells into myofibroblasts is called epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT). It is a process in which epithelial cells lose their properties and show alterations in morphology, cellular architecture, adhesion and migration capacity39,40. EMT occurs during organ development and in pathological conditions, e.g., in tumours or other diseases originating from fibroblasts37. EMT in kidney epithelial and intercalated cells was also described. It is the cause of tubulo-interstitial fibrosis34,41,42. Moreover Manetti et al.43 found that EMT may take a place in the skin of patients with SSc and may have therefore a role in the pathogenesis of dermal fibrosis. They characterized the phenotype of dermal microvascular endothelial cells, which was associated with reduction in the expression of epithelial markers CD31 and vascular endothelial cadherin and an upregulation of mesenchymal markers, including α-SMA+ stress fibers, fibroblast specific protein-1 (FSP1/S100A4), type I collagen and Snail1 protein43.

Activation of the NOTCH pathway in the endothelium leads to EMT and to morphological, phenotypic and functional changes in epithelial cells44. During EMT is observed loss of expression of some genes, whose products are involved in regulation of cellular adhesion (claudins and E-cadherin) and inhibition of cytoskeletal proteins (for example SMAD6/7) to promote the mesenchymal phenotype30. Markers typical for EMT include increased expression of N-cadherin, vimentin, FSP1 and α-SMA, nuclear localization of β-catenin, decreased expression of E-cadherins and CD31 molecules39. Cytoskeletal changes promote increased cytosol mobility and the acquisition of a phenotype typical for myofibroblasts42.

Many signalling pathways, are involved in the activation of fibroblasts and EMT including transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1), bone morphogenic protein, EGF, fibroblast growth factor, platelet-derived growth factor, Wnt, Sonic Hedgehog and integrin signalling6,45,46,47,48,49,50,51. These signalling pathways activate, trough intracellular kinases, transcription factors that activate the expression of EMT-associated genes52.

Several transcription factors can be involved in the induction of EMT, among them, are the zinc-finger binding proteins Snail1 and Snail2 (also known as Slug)53. Notch signalling can regulate expression of Snail1 in a non-direcive way through induction of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α, which binds to promoter of lysyl oxidase gene following transcription of Snail1 gene54. Snail2 interacts with NOTCH receptors and is essential for Notch-mediated inhibition of E-cadherin and β-catenin genes expression55.

In addition to EMT mediated by many signalling pathways, NOTCH regulates indirectly EMT through nuclear factor kappa B, β-catenin pathways, as well as, through the action of various microRNAs56. For example JAG-2, NOTCH ligand, promotes EMT through the expression of GATA3 gene (GATA-binding protein 3), which encodes transcription factor inhibiting the cluster of microRNA-20056. Activation of the NOTCH pathway by JAG-1 in epithelial cells of breast cancer induces EMT, which leads to promoting the invasion and dissemination of malignant cells57.

INHIBITORS OF NOTCH AND NOTCH-ASSOCIATED PATHWAYS

Ligands endocytosis of the NOTCH pathway has the inhibitory effect on signal transduction. In mammals, four E3 ubiquitin ligases are involved in the process of endocytosis: neuralized-1 (Neur1), neuralized-2 (Neur2), mind bomb-1 (Mib1) and mind bomb-2 (Mib2)58. The Mib1 enzyme plays the essential role in inhibiting the NOTCH pathway, while the other ligases play an auxiliary role59. Taking into above, Choi et al.25 demonstrated that deletion of gene encoding Mib1 in kidney intercalated cells leads to increased expression of TGF-β1 and ECM volume. TGF-β1 may intensify fibrosis, for example in patients with SSc, it increases the expression of NICD and the hes family basic Helix-Loop-Helix transcription factor 1 (HES-1) protein in dermal fibroblasts (Fig. 1)24,60,61.

Inhibition of the NOTCH pathway can be carried out by suppressing the activity of γ-secretase and blocking or reduction of the synthesis of ligands (DLL and JAG)61. The inhibitor of γ-secretase activity–DAPT (N-[N-(3,5-difluorophenacetyl)- L-alanyl]-S-phenylglycine t-butyl ester) can reduce the intensity of fibrosis62. DAPT reduces the expression of fibrosis-promoting cytokines interleukin (IL)-4, IL-6, TGF-β1 and connective tissue growth factor; and reduces the number of myofibroblasts in mice61. Moreover, Chen et al.63 demonstrated that DAPT reduced the number of cells with characteristics of myofibroblasts and inhibited the expression of TGF-β1. In SSc, blocking the NOTCH pathway by applying DAPT prevents the development of skin fibrosis (bleomycin-induced) in in vitro models dependent on inflammation (dermal fibrosis in inflammation-dependent models) or in animal models, e.g., the tight skin 1 (Tsk-1) mice24,61. Targeting of NOTCH pathway trough anti-sense RNAs or by DAPT can reduce the collagen release in SSc fibroblasts, without any negative effects on wild type fibroblasts24. Furthermore, inhibition of Notch signalling prevent the development of fibrosis in different models, among them, bleomycin-induced fibrosis and in the Tsk-1 mause model7,61.

In SSc skin is observed JAG-1 overexpression, which increased expression of targeted genes in various tissues16. Inhibition of the NOTCH pathway by knockdown of JAG-1 leads to the inhibition of keloid fibroblast proliferation and migration, and has antiangiogenic activity64. The direct effect on the NOTCH pathway results in the reduction of collagen synthesis by fibroblasts and may be effective both in the early proinflammatory stages of SSc and in later phases not related to the inflammatory process24,61.

LIVER FIBROSIS

The mechanism of tissue fibrosis has been well understood in the liver. Its fibrosis occurs as a result of chronic liver disease. In SSc is observed excessive fibrosis in the viscera and activation of hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) after liver injury65. Activated HSCs are characterised by increased expression of α-SMA and can be transformed into myofibroblasts66. Activation/auto-activation of HSCs increases fibrosis and biosynthesis of JAG-1 ligand and the expression of the Notch3 gene63. Unactivated HSCs do not show an expression of both JAG-1/2 ligands67. All four types of NOTCH receptors are expressed on the surface of healthy liver cells. Liver fibrosis increases expression of NOTCH3 protein/Notch3 gene68,69. The expression of Notch1, Notch2 and Notch4 genes is at a similar level in both healthy and fibrotic liver cells69.

KIDNEY FIBROSIS

Kidney involvement is SSc is primarily manifested by SRC. It is defined as the accelerated arterial hypertension and/or rapidly progressive oliguric renal failure. The primary process, associated with SRC, is injury to the endothelial cells70. These cells are found in vascular, glomerular and peritubular capillary (PTC) beds71. Kidney endothelial cells, which underwent EMT, play an important role in the fibrosis of this organ72.

Kidney fibrosis is the hallmark of chronic kidney disease (CKD). It is characterized by the accumulation of myofibroblasts and excessive deposition of ECM components and the tubulo-interstitial fibrosis25,73,74. The kidney fibrosis process is accompanied by the process of repairing PTCs. However, renal PTCs are very susceptible to atrophy occurring after this organ has been damaged75. The concomitance of PTCs with interstitial fibrosis is one of the main symptoms of CKD. Animal models showed a negative correlation between the density of PTCs and the intensity of fibrosis75. In patients with CKD, the increased loss of PTCs is a factor associated with increased interstitial fibrosis and kidney failure42,76. The repression of Notch1 signalling counteracts PTC rarefaction75.

NOTCH pathway is involved in the development of tubulointerstitial fibrosis and the differentiation or pathological changes of kidney podocytes and tubular cells6,67,77,78. Reduced NOTCH signalling is observed in the healthy adult kidney67. The expression of JAG-1 and HES-1 increases in CKD79,80.

LUNG FIBROSIS

ILD is observed in up to 50% of SSc patients28,81. Pulmonary fibrosis is associated with dysfuntion of epithelial cells, accumulation of fibroblasts, increased production of TGF-β1, excessive deposition in ECM and abnormal lung remodeling82,83. Idiopathic pulmonary disease is characterized by myofibroblast formation (by EMT), which is facilitated by activation of NOTCH pathway84. Liu et al.9 indicated, that TGF-β1 stimulated expression of JAG-1, Notch1, NICD and HES-1 following the differentiation of rat primary lung fibroblasts.

HEART FIBROSIS

NOTCH pathway is a key mechanism of normal heart morphogenesis. It regulates cardiomyocyte proliferation, formation of valves, atrioventricular canal, outflow tract and coronary vessels85,86.

Cardiac fibrosis is characterized by excessive deposition of scar tissue Cross-talk between NOTCH and TGF-β pathways play an important role during the development of the heart. Furthermore, NOTCH pathway is involved in the heart fibrosis after myocardial infarction (MI), primarily through myofibroblast differentiation87.

NOTCH receptors and their ligands are localized to the vasculature, as well as, are observed in endocardium. JAG-1, which is NOTCH ligand, is present on endocardial and periendocardial cells of the cardiac cushions88,89,90. In vivo study of Boopathy et al.91, showed that delivery of JAG-1 ligand through intramyocardial injection in rats with MI reduced cardiac fibrosis. The inhibition of NOTCH receptors expression-1, 3, and 4 promotes fibroblast- myofibroblast transition87. Moreover, Zhang et al.92 found in animal model that overexpression of Notch3 receptor (as a result of cDNA lentivirus inections) increased mice survival rate, improved cardiac function and minimized MI-induced increase in cardiac fibrosis.

SUMMARY

The ever growing evidence suggests that the NOTCH pathway is involved in the development of fibrosis in various organs7,61. However, the molecular mechanisms associated with this process have not been fully recognised. It is possible that inhibitors of NOTCH receptors or their ligands will be used in the future in new therapeutic strategies in SSc patients. Furthermore, there is insufficient data on the expression of NOTCH receptors, the occurrence of polymorphisms and possible mutations in genes which encode the above receptors in fibrotic tissues. The research in this area is still to be continued.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST: The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Wilson MD. Fibrogenesis: mechanisms, dynamics and clinical implications. Iran J Pathol. 2015;10:83–88. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hernandez-Gea V, Friedman SL. Pathogenesis of liver fibrosis. Annu Rev Pathol. 2011;6:425–456. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pattanaik D, Brown M, Postlethwaite BC, Postlethwaite AE. Pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis. Front Immunol. 2015;6:272. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beyer C, Distler O, Distler JH. Innovative antifibrotic therapies in systemic sclerosis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2012;24:274–280. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e3283524b9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.LeRoy EC, Black C, Fleischmajer R, Jablonska S, Krieg T, Medsger TA, Jr, et al. Scleroderma (systemic sclerosis): classification, subsets and pathogenesis. J Rheumatol. 1988;15:202–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bielesz B, Sirin Y, Si H, Niranjan T, Gruenwald A, Ahn S, et al. Epithelial Notch signaling regulates interstitial fibrosis development in the kidneys of mice and humans. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:4040–4054. doi: 10.1172/JCI43025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kavian N, Servettaz A, Mongaret C, Wang A, Nicco C, Chéreau C, et al. Targeting ADAM-17/notch signaling abrogates the development of systemic sclerosis in a murine model. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:3477–3487. doi: 10.1002/art.27626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amsen D, Blander JM, Lee GR, Tanigaki K, Honjo T, Flavell RA. Instruction of distinct CD4 T helper cell fates by different notch ligands on antigen-presenting cells. Cell. 2004;117:515–526. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00451-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu Y, Huang G, Mo B, Wang C. Artesunate ameliorates lung fibrosis via inhibiting the Notch signaling pathway. Exp Ther Med. 2017;14:561–566. doi: 10.3892/etm.2017.4573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maillard I, Adler SH, Pear WS. Notch and the immune system. Immunity. 2003;19:781–791. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00325-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D'Souza B, Miyamoto A, Weinmaster G. The many facets of Notch ligands. Oncogene. 2008;27:5148–5167. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.D'Souza B, Meloty-Kapella L, Weinmaster G. Canonical and non-canonical Notch ligands. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2010;92:73–129. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(10)92003-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kovall RA, Blacklow SC. Mechanistic insights into Notch receptor signaling from structural and biochemical studies. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2010;92:31–71. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(10)92002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mazzone M, Selfors LM, Albeck J, Overholtzer M, Sale S, Carroll DL, et al. Dose-dependent induction of distinct phenotypic responses to Notch pathway activation in mammary epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:5012–5017. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000896107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zheng S, Zhang P, Chen Y, Zheng S, Zheng L, Weng Z. Inhibition of Notch signaling attenuates schistosomiasis hepatic fibrosis via blocking macrophage M2 polarization. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0166808. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0166808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yuan X, Wu H, Han N, Xu H, Chu Q, Yu S, et al. Notch signaling and EMT in non-small cell lung cancer: biological significance and therapeutic application. J Hematol Oncol. 2014;7:87. doi: 10.1186/s13045-014-0087-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim JE, Lee JH, Jeong KH, Kim GM, Kang H. Notch intracellular domain expression in various skin fibroproliferative diseases. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:332–337. doi: 10.5021/ad.2014.26.3.332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin HY, Kao CH, Lin KM, Kaartinen V, Yang LT. Notch signaling regulates late-stage epidermal differentiation and maintains postnatal hair cycle homeostasis. PLoS One. 2011;6:e15842. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Okuyama R, Tagami H, Aiba S. Notch signaling: its role in epidermal homeostasis and in the pathogenesis of skin diseases. J Dermatol Sci. 2008;49:187–194. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2007.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shih B, Garside E, McGrouther DA, Bayat A. Molecular dissection of abnormal wound healing processes resulting in keloid disease. Wound Repair Regen. 2010;18:139–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2009.00553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krebs LT, Xue Y, Norton CR, Shutter JR, Maguire M, Sundberg JP, et al. Notch signaling is essential for vascular morphogenesis in mice. Genes Dev. 2000;14:1343–1352. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fiúza UM, Arias AM. Cell and molecular biology of Notch. J Endocrinol. 2007;194:459–474. doi: 10.1677/JOE-07-0242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garrison G, Huang SK, Okunishi K, Scott JP, Kumar Penke LR, Scruggs AM, et al. Reversal of myofibroblast differentiation by prostaglandin E(2) Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2013;48:550–558. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2012-0262OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dees C, Tomcik M, Zerr P, Akhmetshina A, Horn A, Palumbo K, et al. Notch signalling regulates fibroblast activation and collagen release in systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:1304–1310. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.134742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Choi A, Nam SA, Kim WY, Park SH, Kim H, Yang CW, et al. Notch signaling in the collecting duct regulates renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis induced by unilateral ureteral obstruction in mice. Korean J Intern Med. 2018;33:774–782. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2016.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ciechomska M, van Laar J, O'Reilly S. Current frontiers in systemic sclerosis pathogenesis. Exp Dermatol. 2015;24:401–406. doi: 10.1111/exd.12673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Varga J, Abraham D. Systemic sclerosis: a prototypic multisystem fibrotic disorder. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:557–567. doi: 10.1172/JCI31139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gabrielli A, Avvedimento EV, Krieg T. Scleroderma. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1989–2003. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0806188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gao H, Zhang J, Liu T, Shi W. Rapamycin prevents endothelial cell migration by inhibiting the endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition and matrix metalloproteinase-2 and -9: an in vitro study. Mol Vis. 2011;17:3406–3414. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gonzalez DM, Medici D. Signaling mechanisms of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Sci Signal. 2014;7:re8. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2005189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hinz B, Phan SH, Thannickal VJ, Prunotto M, Desmoulière A, Varga J, et al. Recent developments in myofibroblast biology: paradigms for connective tissue remodeling. Am J Pathol. 2012;180:1340–1355. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hu B, Phan SH. Myofibroblasts. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2013;25:71–77. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e32835b1352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baum J, Duffy HS. Fibroblasts and myofibroblasts: what are we talking about? J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2011;57:376–379. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3182116e39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grgic I, Duffield JS, Humphreys BD. The origin of interstitial myofibroblasts in chronic kidney disease. Pediatr Nephrol. 2012;27:183–193. doi: 10.1007/s00467-011-1772-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xia JL, Dai C, Michalopoulos GK, Liu Y. Hepatocyte growth factor attenuates liver fibrosis induced by bile duct ligation. Am J Pathol. 2006;168:1500–1512. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rygiel KA, Robertson H, Marshall HL, Pekalski M, Zhao L, Booth TA, et al. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition contributes to portal tract fibrogenesis during human chronic liver disease. Lab Invest. 2008;88:112–123. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zeisberg M, Yang C, Martino M, Duncan MB, Rieder F, Tanjore H, et al. Fibroblasts derive from hepatocytes in liver fibrosis via epithelial to mesenchymal transition. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:23337–23347. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700194200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dooley S, Hamzavi J, Ciuclan L, Godoy P, Ilkavets I, Ehnert S, et al. Hepatocyte-specific Smad7 expression attenuates TGF-beta-mediated fibrogenesis and protects against liver damage. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:642–659. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee JM, Dedhar S, Kalluri R, Thompson EW. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition: new insights in signaling, development, and disease. J Cell Biol. 2006;172:973–981. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200601018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Teng Y, Zeisberg M, Kalluri R. Transcriptional regulation of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:304–306. doi: 10.1172/JCI31200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.LeBleu VS, Taduri G, O'Connell J, Teng Y, Cooke VG, Woda C, et al. Origin and function of myofibroblasts in kidney fibrosis. Nat Med. 2013;19:1047–1053. doi: 10.1038/nm.3218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Choi YJ, Chakraborty S, Nguyen V, Nguyen C, Kim BK, Shim SI, et al. Peritubular capillary loss is associated with chronic tubulointerstitial injury in human kidney: altered expression of vascular endothelial growth factor. Hum Pathol. 2000;31:1491–1497. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2000.20373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Manetti M, Romano E, Rosa I, Guiducci S, Bellando-Randone S, De Paulis A, et al. Endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition contributes to endothelial dysfunction and dermal fibrosis in systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:924–934. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Noseda M, McLean G, Niessen K, Chang L, Pollet I, Montpetit R, et al. Notch activation results in phenotypic and functional changes consistent with endothelial-to-mesenchymal transformation. Circ Res. 2004;94:910–917. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000124300.76171.C9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schnaper HW, Jandeska S, Runyan CE, Hubchak SC, Basu RK, Curley JF, et al. TGF-beta signal transduction in chronic kidney disease. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2009;14:2448–2465. doi: 10.2741/3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McCormack N, O'Dea S. Regulation of epithelial to mesenchymal transition by bone morphogenetic proteins. Cell Signal. 2013;25:2856–2862. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2013.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Heldin CH, Vanlandewijck M, Moustakas A. Regulation of EMT by TGFβ in cancer. FEBS Lett. 2012;586:1959–1970. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Espinoza I, Miele L. Deadly crosstalk: Notch signaling at the intersection of EMT and cancer stem cells. Cancer Lett. 2013;341:41–45. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Al Moustafa AE, Achkhar A, Yasmeen A. EGF-receptor signaling and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in human carcinomas. Front Biosci (Schol Ed) 2012;4:671–684. doi: 10.2741/s292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Katoh Y, Katoh M. FGFR2-related pathogenesis and FGFR2-targeted therapeutics (Review) Int J Mol Med. 2009;23:307–311. doi: 10.3892/ijmm_00000132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Taipale J, Beachy PA. The Hedgehog and Wnt signalling pathways in cancer. Nature. 2001;411:349–354. doi: 10.1038/35077219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thiery JP, Acloque H, Huang RY, Nieto MA. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in development and disease. Cell. 2009;139:871–890. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Peinado H, Portillo F, Cano A. Transcriptional regulation of cadherins during development and carcinogenesis. Int J Dev Biol. 2004;48:365–375. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.041794hp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sahlgren C, Gustafsson MV, Jin S, Poellinger L, Lendahl U. Notch signaling mediates hypoxia-induced tumor cell migration and invasion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:6392–6397. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802047105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Timmerman LA, Grego-Bessa J, Raya A, Bertrán E, Pérez-Pomares JM, Díez J, et al. Notch promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition during cardiac development and oncogenic transformation. Genes Dev. 2004;18:99–115. doi: 10.1101/gad.276304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yang Y, Ahn YH, Gibbons DL, Zang Y, Lin W, Thilaganathan N, et al. The Notch ligand Jagged2 promotes lung adenocarcinoma metastasis through a miR-200-dependent pathway in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:1373–1385. doi: 10.1172/JCI42579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Leong KG, Niessen K, Kulic I, Raouf A, Eaves C, Pollet I, et al. Jagged1-mediated Notch activation induces epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition through Slug-induced repression of E-cadherin. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2935–2948. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Le Borgne R. Regulation of Notch signalling by endocytosis and endosomal sorting. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2006;18:213–222. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Itoh M, Kim CH, Palardy G, Oda T, Jiang YJ, Maust D, et al. Mind bomb is a ubiquitin ligase that is essential for efficient activation of Notch signaling by Delta. Dev Cell. 2003;4:67–82. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00409-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kavian N, Servettaz A, Weill B, Batteux F. New insights into the mechanism of notch signalling in fibrosis. Open Rheumatol J. 2012;6:96–102. doi: 10.2174/1874312901206010096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dees C, Zerr P, Tomcik M, Beyer C, Horn A, Akhmetshina A, et al. Inhibition of Notch signaling prevents experimental fibrosis and induces regression of established fibrosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:1396–1404. doi: 10.1002/art.30254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Xiao Z, Zhang J, Peng X, Dong Y, Jia L, Li H, et al. The Notch γ-secretase inhibitor ameliorates kidney fibrosis via inhibition of TGF-β/Smad2/3 signaling pathway activation. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2014;55:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2014.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chen Y, Zheng S, Qi D, Zheng S, Guo J, Zhang S, et al. Inhibition of Notch signaling by a γ-secretase inhibitor attenuates hepatic fibrosis in rats. PLoS One. 2012;7:e46512. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Syed F, Bayat A. Notch signaling pathway in keloid disease: enhanced fibroblast activity in a Jagged-1 peptide-dependent manner in lesional vs. extralesional fibroblasts. Wound Repair Regen. 2012;20:688–706. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2012.00823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Friedman SL. Hepatic stellate cells: protean, multifunctional, and enigmatic cells of the liver. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:125–172. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00013.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lee UE, Friedman SL. Mechanisms of hepatic fibrogenesis. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;25:195–206. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sawitza I, Kordes C, Reister S, Häussinger D. The niche of stellate cells within rat liver. Hepatology. 2009;50:1617–1624. doi: 10.1002/hep.23184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chen YX, Weng ZH, Zhang SL. Notch3 regulates the activation of hepatic stellate cells. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:1397–1403. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i12.1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nijjar SS, Crosby HA, Wallace L, Hubscher SG, Strain AJ. Notch receptor expression in adult human liver: a possible role in bile duct formation and hepatic neovascularization. Hepatology. 2001;34:1184–1192. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.29399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Steen VD, Mayes MD, Merkel PA. Assessment of kidney involvement. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2003;21(3 Suppl 29):S29–S31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zeisberg EM, Potenta SE, Sugimoto H, Zeisberg M, Kalluri R. Fibroblasts in kidney fibrosis emerge via endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:2282–2287. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008050513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhao Y, Qiao X, Tan TK, Zhao H, Zhang Y, Liu L, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase 9-dependent Notch signaling contributes to kidney fibrosis through peritubular endothelial-mesenchymal transition. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2017;32:781–791. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfw308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sutariya B, Jhonsa D, Saraf MN. TGF-β: the connecting link between nephropathy and fibrosis. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 2016;38:39–49. doi: 10.3109/08923973.2015.1127382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yan J, Zhang Z, Jia L, Wang Y. Role of bone marrow-derived fibroblasts in renal fibrosis. Front Physiol. 2016;7:61. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2016.00061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Basile DP. Rarefaction of peritubular capillaries following ischemic acute renal failure: a potential factor predisposing to progressive nephropathy. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2004;13:1–7. doi: 10.1097/00041552-200401000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Serón D, Alexopoulos E, Raftery MJ, Hartley B, Cameron JS. Number of interstitial capillary cross-sections assessed by monoclonal antibodies: relation to interstitial damage. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1990;5:889–893. doi: 10.1093/ndt/5.10.889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kida Y, Zullo JA, Goligorsky MS. Endothelial sirtuin 1 inactivation enhances capillary rarefaction and fibrosis following kidney injury through Notch activation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016;478:1074–1079. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.08.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tung CW, Hsu YC, Cai CJ, Shih YH, Wang CJ, Chang PJ, et al. Trichostatin A ameliorates renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis through modulation of the JNK-dependent Notch-2 signaling pathway. Sci Rep. 2017;7:14495. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-15162-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sirin Y, Susztak K. Notch in the kidney: development and disease. J Pathol. 2012;226:394–403. doi: 10.1002/path.2967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Walsh DW, Roxburgh SA, McGettigan P, Berthier CC, Higgins DG, Kretzler M, et al. Co-regulation of Gremlin and Notch signalling in diabetic nephropathy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1782:10–21. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Meyer OC, Fertig N, Lucas M, Somogyi N, Medsger TA., Jr Disease subsets, antinuclear antibody profile, and clinical features in 127 French and 247 US adult patients with systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol. 2007;34:104–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Loomis-King H, Flaherty KR, Moore BB. Pathogenesis, current treatments and future directions for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2013;13:377–385. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2013.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zhou Y, Liao S, Zhang Z, Wang B, Wan L. Astragalus injection attenuates bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis via down-regulating Jagged1/Notch1 in lungs. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2016;68:389–396. doi: 10.1111/jphp.12518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Liu T, Hu B, Choi YY, Chung M, Ullenbruch M, Yu H, et al. Notch1 signaling in FIZZ1 induction of myofibroblast differentiation. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:1745–1755. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.MacGrogan D, Nus M, de la Pompa JL. Notch signaling in cardiac development and disease. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2010;92:333–365. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(10)92011-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Luxán G, D'Amato G, MacGrogan D, de la. Endocardial Notch signaling in cardiac development and disease. Circ Res. 2016;118:e1–e18. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.305350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Fan YH, Dong H, Pan Q, Cao YJ, Li H, Wang HC. Notch signaling may negatively regulate neonatal rat cardiac fibroblast-myofibroblast transformation. Physiol Res. 2011;60:739–748. doi: 10.33549/physiolres.932149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Iso T, Hamamori Y, Kedes L. Notch signaling in vascular development. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:543–553. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000060892.81529.8F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Loomes KM, Taichman DB, Glover CL, Williams PT, Markowitz JE, Piccoli DA, et al. Characterization of Notch receptor expression in the developing mammalian heart and liver. Am J Med Genet. 2002;112:181–189. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.10592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Loomes KM, Underkoffler LA, Morabito J, Gottlieb S, Piccoli DA, Spinner NB, et al. The expression of Jagged1 in the developing mammalian heart correlates with cardiovascular disease in Alagille syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:2443–2449. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.13.2443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Boopathy AV, Martinez MD, Smith AW, Brown ME, García AJ, Davis ME. Intramyocardial delivery of Notch ligand-containing hydrogels improves cardiac function and angiogenesis following infarction. Tissue Eng Part A. 2015;21:2315–2322. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2014.0622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zhang M, Pan X, Zou Q, Xia Y, Chen J, Hao Q, et al. Notch3 ameliorates cardiac fibrosis after myocardial infarction by inhibiting the TGF-β1/Smad3 pathway. Cardiovasc Toxicol. 2016;16:316–324. doi: 10.1007/s12012-015-9341-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]