Abstract

Introduction.

We have hypothesized that biofabrication of appendiceal tumor organoids allows for a more personalized clinical approach and facilitates research in a rare disease.

Methods.

Appendiceal cancer specimens obtained during cytoreduction with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy procedures (CRS/HIPEC) were dissociated and incorporated into an extracellular matrix-based hydrogel system as three-dimensional (3D), patient-specific tumor organoids. Cells were not sorted, preserving tumor heterogeneity, including stroma and immune cell components. Following establishment of organoid sets, chemotherapy drugs were screened in parallel. Live/dead staining and quantitative metabolism assays recorded which chemotherapies were most effective in killing cancer cells for a specific patient. Maintenance of cancer phenotypes were confirmed by using immunohistochemistry.

Results.

Biospecimens from 12 patients were applied for organoid development between November 2016 and May 2018. Successful establishment rate of viable organoid sets was 75% (9/12). Average time from organoid development to chemotherapy testing was 7 days. These tumors included three high-grade appendiceal (HGA) and nine low-grade appendiceal (LGA) primaries obtained from sites of peritoneal metastasis. All tumor organoids were tested with chemotherapeutic agents exhibited responses that were either similar to the patient response or within the variability of the expected clinical response. More specifically, HGA tumor organoids derived from different patients demonstrated variable chemotherapy tumor-killing responses, whereas LGA organoids tested with the same regimens showed no response to chemotherapy. One LGA set of organoids was immune-enhanced with cells from a patient-matched lymph node to demonstrate feasibility of a symbiotic 3D reconstruction of a patient matched tumor and immune system component.

Conclusions.

Development of 3D appendiceal tumor organoids is feasible even in low cellularity LGA tumors, allowing for individual patient tumors to remain viable for research and personalized drug screening.

Personalized medicine through next-generation sequencing (NGS) analysis relates tumor genomic mutations with available chemotherapy agents. The scarce cellularity of low-grade appendiceal tumors (LGA) establishes them as difficult NGS target and partially explains why culturing these tumors in vitro or developing LGA cell lines has been an elusive proposal. Furthermore, identification of a specific mutation on NGS analysis does not necessarily mean that the mutation is a prominent participant in genesis and progression or a “driver mutation” of the specific malignancy. In rare diseases, such as appendiceal cancer, the limited clinical outcomes are derived from statistical analysis of heterogeneous cohorts with similar, but not identical, disease characteristics.

Attempting to develop more clinical precision at the level of the individual patient, we have previously reconstructed several different types of tumor of epithelial and mesenchymal origin, including melanomas, sarcomas, lung cancer, colorectal cancer, and rare mesothelioma variants, in the form of three-dimensional (3D) tumor organoids.1,2 Using established biofabrication methodologies, reconstructing the patient’s own tumor in the laboratory, in the form of tumor organoids, is an effective model for capturing tumor heterogeneity and possibly predicting response to chemotherapy and immunotherapy before delivering chemotherapy to the patient.1-5 These tumor organoids recapitulate the tumor microenvironment by incorporating not only tumor cells but also associated stroma and tumor infiltrating leucocytes (TILs) and are supported by a naturally-derived extracellular matrix (ECM) hydrogels.1,6-10

We have hypothesized that 3D organoid biofabrication from appendiceal tumors is feasible even from notoriously low cellularity tumors, such as LGA primaries, allowing for individual patient tumor and stroma to remain viable for personalized drug screening.

METHODS

Biospecimens were obtained from nine patients with low-grade and three patients with high-grade appendiceal primaries during CRS/HIPEC procedures from November 2016 to May 2018 in adherence to the guidelines of the Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center institutional review board protocols. The specimens were placed in RPMI and transferred fresh to the laboratory by a dedicated tissue procurement manager.

Tumor Biospecimen Procurement and Cell Processing

Fresh tumor tissue biospecimens were delivered within 1 h of removal to the lab for cell processing. Once received, tumors were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 2% penicillin–streptomycin for three 5-min cycles and then washed in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) with 2% penicillin–streptomycin for two 5-min cycles. Tumors were individually minced and placed into DMEM with 2% penicillin–streptomycin and 10% collagenase/hyaluronidase for up to 2 h on a shaker plate in 37 °C (10X Collagenase/Hyaluronidase in DMEM, STEMCELL Technologies, Seattle, WA). Digested tumors were then filtered through a 100-μm cell filter and centrifuged to create a cell pellet. Plasma and noncellular material was removed, and the pellet was resuspended in 1 mL of BD PharmLyse with 9 mL of deionized water for 5 min (BD PharmLyse, San Diego, CA). The conical was filled to 50 mL with deionized water and centrifuged, lyse buffer with lysed cells was aspirated, and the cell number was counted for use. From one patient, a lymph node also was removed and processed in the same manner to retrieve immunocompetent cells.

Extracellular Matrix Hydrogel Preparation and Tumor Organoid Formation

An ECM-mimicking HA/collagen-based hydrogel was prepared, modified from an HA/gelatin system (HyStem-HP, ESI-BIO, Alameda, CA) that has been previously described.3,5,8 Briefly, a thiolated HA component (Glycosil, ESI-BIO) and a methacrylated collagen component (Advanced BioMatrix, San Diego, CA) were dissolved in sterile water containing 0.05% w/v of the photoinitiator 2-Hydroxy-4′-(2-hydroxyethoxy)-2-methylpropiophenone (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) to make 2-mg/mL and 6-mg/mL solutions, respectively. The collagen solution was then neutralized using manufacturer provided neutralization solution at 85 μL of solution per milliliter of collagen. The HA and collagen solutions were then mixed in a 3:1 ratio by volume and mixed thoroughly. The resulting mixture was employed to suspend the unsorted cell populations from either HGA or LGA biospecimens at a cell density of 10 million cells/mL hydrogel precursor solution. Organoids (cells supported by the ECM hydrogel) were formed by pipetting 5 μL of hydrogel precursor cell suspension into 48-well plates previously coated with a thin layer of polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) to form consistently round droplets, which were subsequently photocrosslinked by ultraviolet light exposure (365 nm, 18 W cm−2) for 1 s, initiating crosslinking through thiol-methacrylate and methacrylate–methacrylate bond formation. As an optional addition, organoids could be integrated into microfluidic devices as recently described.11 Organoids were subsequently maintained in DMEM with 10% FBS (Hyclone, Logan, UT), 1% penicillin–streptomycin, and 1% l-glutamine. In one set of additional “immune-enhanced” organoids, the whole population of cells derived from a lymph node from one patient was used to supplement the cells from the tumor biospecimen. In these organoids, the lymph node cells were added as an additional 2 million cells/mL.

Tumor Organoid Viability Assessment

LIVE/DEAD staining (LIVE/DEAD Viability/Cytotoxicity Kit for mammalian cells, ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA) was performed on day 7 for initial assessment and at the end of the drug exposure period (4 days in total). Spent media was first aspirated from wells, after which a 100-μL mixture of PBS and DMEM (1:1) containing 2 μM of calcein-AM and 2 μM of ethidium homodimer-1 was introduced. Constructs were incubated for 60 min after which spent media was again aspirated and replaced with clean PBS. Fluorescent imaging was performed using a Leica TCS LSI macro confocal microscope. Also, 100-μm z-stacks were obtained for each construct using filters appropriate for both red and green fluorescence (594 nm and 488 nm, respectively) and then overlaid.

Organoid Tissue Characterization

On day 7, HGA and LGA tumor organoids were washed twice with DPBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 1 h and then additionally washed twice with DPBS. Cultures were histologically processed, paraffin embedded, and sectioned at 5-μm thickness. Tissue sections on microscope slides were then stained with hemotoxylin and eosin (H&E).

IHC was used to visualize biomarkers mucin 2 (MUC2) and cytokeratin 20 (CK20). Blocking was performed by incubation under Dako Protein Block for 15 min. Primary antibodies MUC2 (ab11197, abcam, raised in mouse), CK20 (ab76126, abcam, raised in rabbit), or CD44 (ab157107, abcam, raised in rabbit) were applied to the sections on the slides at a 1:200 dilution in Dako Antibody Diluent and incubated at room temperature for 1 h. Next, secondary Alexa Fluor 488 or Alexa Fluor 594 antibodies (ThermoFisher) with appropriate species reactivity were applied to all samples at 1:200 in Dako Antibody Diluent and left at room temperature for 1 h (anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488 and anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 594, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, A-11070). Sections were then incubated with Dapi for 5 min before coverslipping. Sections were imaged on a Leica upright fluorescent microscope.

Drug Studies

Organoids were employed in chemosensitivity screens during which they were subjected to treatment with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), oxaliplatin, FOLFOX, FOLFIRI, or regorafenib. Stock solutions of 10 μM were prepared for 5-FU (F6627, Sigma), oxaliplatin (O9512, Sigma), irinotecan (I1406, Sigma), and regorafenib (S1178, Selleckchem, Houston, TX) by dissolving in DMSO. Stock solutions were diluted in DMEM cell culture media to the following concentrations: 5FU–10 μM; Oxaliplatin—1 μM; FOLFOX (Folinic acid:5-FU:oxaliplatin)—1:10:1 μM; FOLFIRI (Folinic acid:5-FU:irinotecan)—1:10:1 μM Folinic acid:5-FU:oxaliplatin; and regorafenib—10 μM.

On day 7 in culture, spent media was aspirated from the wells, after which fresh media containing each drug combination was added to the wells. Organoids were maintained in drug-containing media for 4 days, after which the effects of the drugs were assessed.

LIVE/DEAD staining was performed on the fourth day following initiation of drug incubation, as described above. Relative mitochondrial metabolism was quantified as an indicator of cellular response to drug treatments by MTS assays. MTS assays (CellTiter 96 One Solution Reagent Promega, Madison, WI) determined relative cell number by quantification of cell-driven reduction of MTS tetrazolium compound to a soluble colored formazan product. Absorbance values were determined on a Molecular Devices SpectrumMax M5 (Molecular Devices) tunable plate reader system at a wavelength of 490 nm.

One set of LGA organoids (tumor cells only and an additional immune-enhanced subset) were subjected to treatment with nivolumab (A2002, Selleckchem), pembrolizumab (A2005, Selleckchem), or no drug. This set of organoids was smaller than other studies, so only MTS assays were performed after 24 h and 4 days after initiation of treatment. Mitochondrial metabolism was quantified as described above.

Statistical Analysis

Data were expressed for each experimental group as mean ± SD and statistical significance determined using statistical analysis methods (GraphPad Prism, GraphPad Software Inc., USA). A number of three or more was used for all studies. Histological, immunohistochemical, or fluorescent images presented in figures are representative of their respective experimental groups. Student’s t tests were performed to compare the means of a normally distributed interval dependent variable for two independent groups. Confidence intervals of 95% or better were considered significant.

RESULTS

Organoid Generation Workflow and Metrics

Tumor tissues were transported to the lab generally within an hour of resection, after which the duration of dissociation with collagenase/hyaluronidase varied from specimen to specimen, but never exceeded 2 h. Biofabrication of the tumor organoids using the supportive ECM hydrogel biomaterials (Fig. 1a) required an additional 30–60 min following dissociation depending on number of cells available, which determined the number of total organoids fabricated. From the biospecimens received in this study, 75–100 organoids were generated in each instance. Of the three HGA and nine LGA patients, viable organoid set were generated from three HGA and six LGA patients, resulting in a total success rate of 75% (9/12). Notably, of these biospecimens only one HGA-derived cell population successfully adhered to plastic tissue 2D culture dishes. The biofabrication workflow also supports the opportunity to generate patient-specific “tumor-on-a-chip” systems as we have recently described, which add the capability to perform staged infusions (e.g., FOLFOX and FOLFIRI treatments via a catheter) as well as linking the tumor organoids to other tissue organoid types.1,3,11

FIG. 1.

Appendiceal tumor organoid fabrication and characterization. a Tumor specimen is dissociated and biofabricated into organoids using ECM-based hyaluronic acid and collagen hydrogels. Optionally, organoids can be integrated with microfluidic devices, thus forming “tumor-on-a-chip” devices that can be linked to other organoids or can be employed for staged drug infusions. The methodology described herein results in (b) high-grade appendiceal tumor organoids and c low-grade appendiceal tumor organoids. Green—calcein AM-stained viable cells; Red—ethidium homodimer-stained dead cells. d H&E staining and e IHC staining of MUC2 and CK20 in HGA organoids. f H&E staining and g IHC staining of MUC2 and CK20 in LGA organoids. h IHC staining of CD44 in a group of aggregated cells in an HGA organoid. Scale bar—50 μm

Patient Characteristics

One of six (17%) developed appendiceal organoids was originating from a LAMN primary, whereas the remaining five of six (83%) developed organoids were developed from well differentiated adenocarcinomas. Of the three specimens that did not produce tumor organoids, one was LAMN, and two were well-differentiated adenocarcinomas.

One of three HGA patients elected not to receive systemic chemotherapy. The second patient had signet ring features and received 14 cycles of neoadjuvant FOLFOX prior to switching to FOLFIRI due to progression. The third HGA patient responded to FOLFOX also in the neoadjuvant setting.

Organoid Viability and Characterization

Following establishment of tumor organoids in culture, organoid viability was determined by LIVE/DEAD staining. Figure 1b shows a high percentage of the cells in HGA organoids remained viable in culture, with minimal cell death. Likewise, Fig. 1c shows the same outcome for LGA organoids. Histological analyses by H&E staining showed that cells in the HGA organoid formed more tissue-like, high cell density structures (Fig. 1d) compared with cells in the LGA organoids, which remained more spread out through the hydrogel (Fig. 1f). This is despite the same starting number of cells during organoid biofabrication. The difference could be explained by the ability of more metabolically active and mesenchymal phenotype cells to reorganize and deposit extracellular matrix, a phenomenon observed in many higher-grade tumors.12 Immunohistochemistry staining using antibodies for MUC2 and CK20, common biomarkers of appendiceal tumor cells, were positive in both HGA and LGA organoids, verifying that the organoids were indeed tumor organoids and not simply containing stromal cells, such as fibroblasts. Figure 1h shows expression of CD44 in a cluster of cells within an HGA organoid, indicating likely preservation of activated tumor fibroblasts.13

Chemosensitivity Data

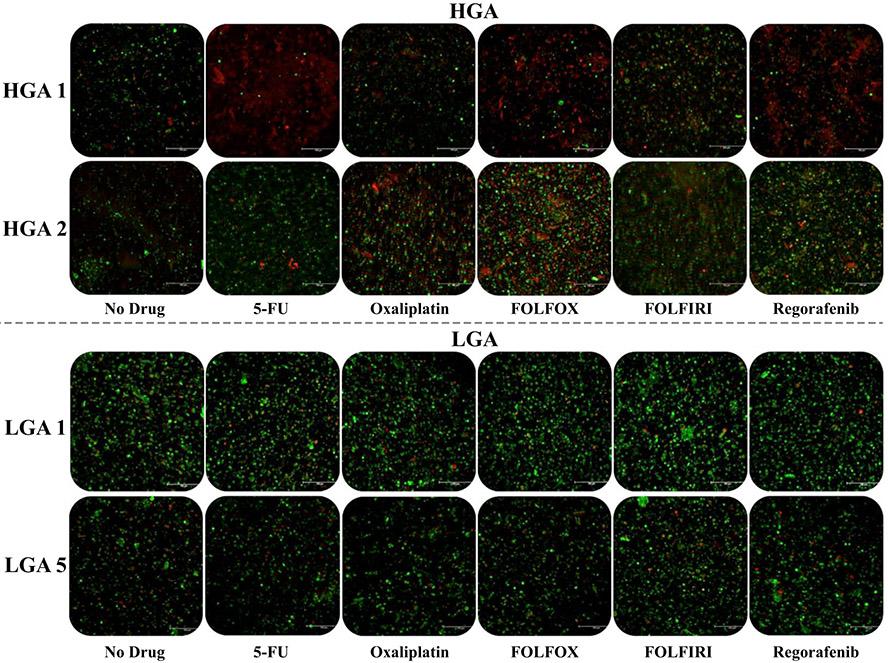

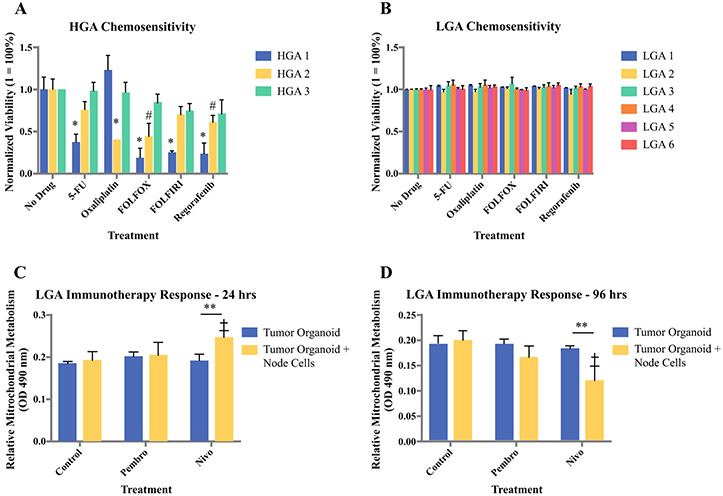

Chemosensitivity studies consisted of 4-day exposures to 5-FU, oxaliplatin, FOLFOX, FOLFIRI, or regorafenib. Figure 2 shows representative LIVE/DEAD-stained images of two sets of HGA organoids and LGA organoids following the chemosensitivity screening. Notably, HGA organoids exhibit an extent of response that varies between patients. Conversely, LGA organoids show no response to any treatment group. Mitochondrial metabolism quantification by MTS assays further demonstrates these trends (Fig. 3a, b). All three HGA and six LGA organoid sets are compiled by normalized metabolic activity. Again, the HGA organoids exhibit variable response to chemotherapy (Fig. 3a), while all six LGA organoid sets show no chemotherapy response (Fig. 3b). Notably, within the HGA data set, HGA 1 showed the most susceptibility to treatment with statistically significant decreases in metabolic activity in response to all treatments except for oxaliplatin alone. HGA 2 and HGA 3 show less relative susceptibility, but there was still some response to most treatments. Importantly, these data, summarized in Table 1, demonstrate (1) patient-to-patient heterogeneity in chemotherapy response, which often is the case in patients with high-grade tumors, and (2) a lack of response to chemotherapy in LGA primaries, which often is observed clinically.

FIG. 2.

Live/dead staining images of HGA and LGA tumor organoids following chemosensitivity screens using 5-FU, oxaliplatin, FOLFOX, FOLFIRI, and regorafenib. HGA tumor organoids exhibit variable chemotherapy response between patient organoid sets. Conversely, LGA tumor organoids do not respond to the same drugs. Green—calcein AM-stained viable cells; Red—ethidium homodimer-stained dead cells

FIG. 3.

Compilation of the a three HGA and b six LGA tumor organoids chemosensitivity data using normalized mitochondrial metabolism to quantify drug responsiveness. Values of “1” indicate high viability without drug response, while values close to 0 indicate drug response. Statistical significance: *p < 0.01 between indicated treatment and same-group control; #p < 0.05 between indicated treatment and same-group control. Preliminary immunotherapy drug screening using immune checkpoint inhibitors pembrolizumab and nivolumab in LGA organoids immune-enhanced with cells from a lymph node from the same patient. Mitochondrial metabolism was assessed at c 24 h and d 96 h after administration of the immunotherapy agents. Statistical significance: **p < 0.05 between tumor cell-only and immune-enhanced organoids; †p < 0.05 between drug treatment and control of the same group

TABLE 1.

Summary of tumor biospecimens and observed tumor organoid viability after chemosensitivity trials

| Patient | Grade | Specimen site | Summary of tumor organoid viability post chemotherapy |

|---|---|---|---|

| HGA 1 | High | Appendix | 5FU 38%, Oxaliplatin 100%, FOLFOX 18%, FOLFIRI 25%, Regorafenib 22% |

| HGA 2 | High | Omentum | 5FU 75%, Oxaliplatin 40%, FOLFOX 42%, FOLFIRI 70%, Regorafenib 62% |

| HGA 3 | High | Omentum | 5FU 98%, Oxaliplatin 97%, FOLFOX 85%, FOLFIRI 75%, Regorafenib 70% |

| LGA 1 | Low | Peritoneum | > 95% viable |

| LGA 2 | Low | Omentum | > 95% viable |

| LGA 3 | Low | Appendix | > 95% viable |

| LGA 4 | Low | Spleen | > 95% viable |

| LGA 5 | Low | Peritoneum | > 95% viable |

| LGA 6 | Low | Appendix | > 95% viable |

Lastly, as a preliminary exploration of whether or not patient-derived tumor organoids can also support immunotherapy-based drug screens, we “immune-enhanced” a set of LGA organoids by incorporating cells from a dissociated lymph node, obtained from the same patient at the same time the LGA tumor biospecimen was obtained. As controls, we also created LGA organoids without the lymph node cell population. These two sets of LGA organoids from the same patient—immune-enhanced and tumor only—were then subjected to pembrolizumab, nivolumab, or no treatment. After 24 h and 72 h, organoids were assessed for mitochondrial metabolism by MTS assays. Interestingly, at the 24-h time point, mitochondrial metabolism was increased in both the pembrolizumab (not statistically significant) and nivolumab (statistically significant) treatments, but only in the organoid set that was enriched with lymph node cells, suggesting activation of T cells in these organoids (Fig. 3c). It is well understood that upon activation, T cell mitochondrial metabolism increases to support the immune response. In comparison, at the 96-h timepoint after drug administration, the mitochondrial metabolism of the immune-enhanced organoids treated with either the immune checkpoint inhibitors was significantly decreased, suggesting a decreased number of metabolically active cells throughout the organoids, likely due to tumor cell killing (Fig. 3d). Notably, these decreases were not observed in organoids without lymph node cells, nor in the control no drug condition.

DISCUSSION

Appendiceal primaries exhibit a variability in outcomes that cannot be predicted by the current classification systems. In the clinical setting, both colon and HAG cancers are treated with the same chemotherapy lines, even though the two primaries have distinct molecular profiles.14 In addition, precision medicine through next-generation sequencing often is not successful in analyzing LGA primaries due to poor cellularity.

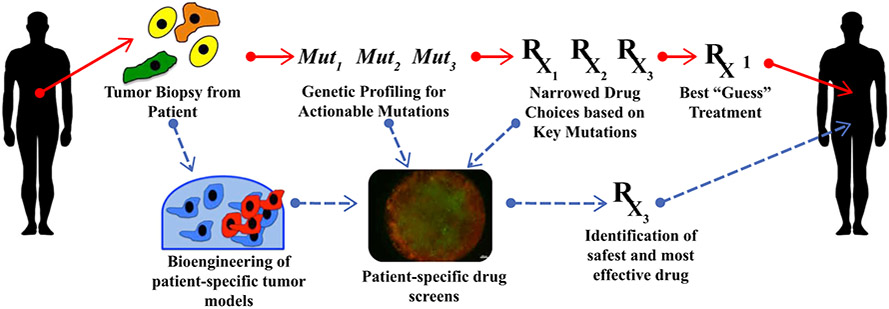

Reconstructing the patient’s own tumor in the form of organoids inclusive of tumor’s own stroma and TILs is an attractive model to bypass the above problems, by capturing tumor heterogeneity while allowing for individualized approach at the single patient level (Fig. 4). Recently, it was shown that in 110 specimens obtained from heavily pretreated colorectal and gastroesophageal junction cancer patients, tumor organoids exhibited chemosensitivities correlated with the patient’s response to chemotherapy with 88% positive predictive value and 100% negative predictive value. When the organoid was responding to chemotherapy, 88% of the corresponding patients also were responding, whereas when the organoid showed no response the patient never responded.15

FIG. 4.

Implementation of tumor organoids within a typical precision medicine workflow. Typical precision medicine approaches (red arrows) employ next generation sequencing to identify targetable mutations. Integrating organoid technology (blue arrows) would allow testing of a variety of chemotherapy agents, resulting in patient-specific empirical drug response data

We hypothesized and have found that 3D organoid biofabrication is feasible from rare tumors, such as the appendiceal primaries as well as from low cellularity LGA tumors allowing for individual patient tumor and stroma to remain viable for personalized drug screening and subsequently better understanding of this rare disease. The herein presented success rate in developing HGA organoids reflects the increased cellularity of the HGA specimens. Low-grade mucinous appendiceal primaries had a take rate of close to 66% (6/9), reflecting the acellular mucin load that was comprising the majority of the surgically obtained specimens. Nevertheless, this is the first time to our knowledge that LGAs are successfully reconstructed ex vivo, possibly opening a new avenue in understanding the specific disease.

The scope of this work was not to establish clinical correlation between appendiceal organoid response to chemotherapy and clinical response of the patient to the same chemotherapy. Despite this, we observed that none of the LGA organoids responded to standard chemotherapy agents or combinations of the agents used. In clinical practice, we do not recommend systemic chemotherapy to LGA patients, because we have not yet seen a clinical effect of systemic chemotherapy for these patients.16 Possibly, these LGA tumor organoids provide the first ex vivo evidence to support our clinical observation.

HGA organoids showed a variable response to chemotherapy as seen in HGA patients treated with systemic chemotherapy. It was interesting that one of the patient’s HGA organoids were more susceptible to a third-line chemotherapy option, such as regorafenib, than first-line chemotherapy agents, suggesting that what is considered as first-line chemotherapy for a cohort of patients may not necessarily be considered as first line for the individual patient. The implications upon establishing correlation on the ability to select therapy based on response and not based on statistics is obvious.

Importantly, while preliminary in nature, we also demonstrate that we can induce what appears to be an immune checkpoint inhibitor response in LGA organoids that were “immune-enhanced” and symbiotically reconstructed with lymph node-derived cells from the same patient. Admittedly, this data will require additional validation, including running similar immune checkpoint inhibitor drug studies with organoids from additional patients, more in-depth viability quantification, IHC, or flow cytometry verification of T-cell presence, education, activation, and evaluation of PD-L1/PD-1 expression on the cells within the organoid. Nevertheless, this is an exciting result, which suggests that in addition to standard chemotherapies, perhaps we can perform patient-specific predictive tests with immunotherapy-based treatments.

Three-dimensional tumor organoids provide a substantially more usable platform to study cancer, as well as for predictive drug screening compared with traditional models. Conventional 2D cultures typically are associated with a take rate of less than 25%, while patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models are successful approximately in 25–33% of attempts with an average time of 6–8 months that makes their incorporation in the clinical setting challenging.17 Additionally, while PDX models can be attractive, because they have the complexities of an organism, such as mouse stroma and a mouse immune system, which further reduce the similarities of the model to the human patient from which they were derived. The time needed to engineer patient-specific tumor organoids and complete chemosensitivity panels is less than 12 days, allowing for this methodology the potential to be incorporated into routine clinical practice without causing delays in treatment planning either in the adjuvant or neoadjuvant setting. We envision that in case of progression on chemotherapy, the progressing lesion can be rebiopsied and new organoids can be developed followed by chemosensitivity screens, potentially capturing tumor clonality and adjusting therapy accordingly. It also is noteworthy that from a 1 cm3 of tissue with average cellularity, up to a few hundred of tumor organoids can be generated for high output concurrent drug testing, including compounds under drug development that have never been tested before on a clinical setting.

A potential limitation for this technology is the influence of the patient being administered upfront chemotherapy on the availability of cells from which the organoids would be made. In our team’s work with other tumor types, we have observed this in several cases. We are typically still able to create organoids, but the total number of organoids could be decreased, thus placing a limit on the breadth of chemosensitivity screening that could be performed.

The undeniable limitation of this study is the modest number of specimens. Nevertheless, this is the first time that tumor organoids are reliably and repeatedly developed directly from both low- and high-grade appendiceal cancer patients. This suggests that this model represents a viable approach to a rare and difficult to study disease.

In conclusion, 3D organoid biofabrication from appendiceal tumors is feasible even from low cellularity LGA primaries. This allows for individual patient tumor and stroma to remain viable for personalized drug screening and providing with an alternative or potentially complementary avenue to analyze and study the genomic profile of a rare disease.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors thank Libby McWilliams (Procurement Manager), Kathleen Cummings (Protocol and Data Manager) and the Wake Forest Advanced Tumor Bank Shared Resource.

FUNDING AS acknowledges funding through the Wake Forest Clinical and Translational Science Institute Open Pilot Program. AS and KV acknowledge funding through the Comprehensive Cancer Center at Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center’s Clinical Research Associate Director Pilot Funds.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Presented at the Society of Surgical Oncology, 13th International Symposium on Regional Cancer Therapies, Jacksonville, FL, February 19, 2018.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mazzocchi AR, Rajan SAP, Votanopoulos KI, Hall AR, Skardal A. In vitro patient-derived 3D mesothelioma tumor organoids facilitate patient-centric therapeutic screening. Sci Rep. 2018;8:2886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mazzocchi A, Soker S, Skardal A. Biofabrication technologies for developing in vitro tumor models. In: Soker S, Skardal A (eds). Tumor organoids. Cancer Drug Discovery and Development. Cham: Humana Press; 2018. pp. 51–70. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Skardal A, Devarasetty M, Forsythe S, Atala A, Soker SA. Reductionist metastasis-on-a-chip platform for in vitro tumor progression modeling and drug screening. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2016;113:2020–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Skardal A, Devarasetty M, Kang HW, Mead I, Bishop C, Shupe T, et al. A hydrogel bioink toolkit for mimicking native tissue biochemical and mechanical properties in bioprinted tissue constructs. Acta Biomater. 2015;25:24–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Skardal A, Devarasetty M, Soker S, Hall AR. In situ patterned micro 3D liver constructs for parallel toxicology testing in a fluidic device. Biofabrication. 2015;7:031001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Skardal A Extracellular matrix-like hydrogels for applications in regenerative medicine. In: Connon CJ, Hamley IW (eds). Hydrogels in cell-based therapies. London: Royal Society of Chemistry; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Skardal A, Murphy SV, Crowell K, Mack D, Atala A, Soker S. A tunable hydrogel system for long-term release of cell-secreted cytokines and bioprinted in situ wound cell delivery. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2016;105(7):1986–2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Skardal A, Smith L, Bharadwaj S, Atala A, Soker S, Zhang Y. Tissue specific synthetic ECM hydrogels for 3-D in vitro maintenance of hepatocyte function. Biomaterials. 2012;33:4565–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Skardal A, Zhang J, McCoard L, Xu X, Oottamasathien S, Prestwich GD. Photocrosslinkable hyaluronan-gelatin hydrogels for two-step bioprinting. Tissue Eng Part A. 2010;16:2675–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Skardal A, Zhang J, Prestwich GD. Bioprinting vessel-like constructs using hyaluronan hydrogels crosslinked with tetrahedral polyethylene glycol tetracrylates. Biomaterials. 2010;31:6173–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Skardal A, Murphy SV, Devarasetty M, Mead I, Kang HW, Seol YJ, et al. Multi-tissue interactions in an integrated three-tissue organ-on-a-chip platform. Sci Rep. 2017;7:8837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Devarasetty M, Skardal A, Cowdrick K, Marini F, Soker S. Bioengineered submucosal organoids for in vitro modeling of colorectal cancer. Tissue Eng Part A. 2017;23:1026–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spaeth EL, Labaff AM, Toole BP, Klopp A, Andreeff M, Marini FC. Mesenchymal CD44 expression contributes to the acquisition of an activated fibroblast phenotype via TWIST activation in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Res. 2013;73:5347–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levine EA, Blazer DG, Kim MK, Shen P, Stewart JH, Guy C, et al. Gene expression profiling of peritoneal metastases from appendiceal and colon cancer demonstrates unique biologic signatures and predicts patient outcomes. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;214:599–606 (discussion 606–7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vlachogiannis G, Hedayat S, Vatsiou A, Jamin Y, Fernández-Mateos J, Khan K, et al. Patient-derived organoids model treatment response of metastatic gastrointestinal cancers. Science. 2018;359:920–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Votanopoulos KI, Russell G, Randle RW, Shen P, Stewart JH, Levine EA. Peritoneal surface disease (PSD) from appendiceal cancer treated with cytoreductive surgery (CRS) and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC): overview of 481 cases. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:1274–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hidalgo M, Amant F, Biankin AV, Budinská E, Byrne AT, Caldas C, et al. Patient-derived xenograft models: an emerging platform for translational cancer research. Cancer Discov. 2014;4:998–1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]