Abstract

Background

Recent climate and environmental changes have resulted in the geographical expansion of Mediterranean Leishmania infantum vectors towards northern latitudes and higher altitudes in different European countries, including Italy, where new foci of canine leishmaniasis have been observed in the northern part of the country. Northern Italy is also an endemic area for mosquito-borne diseases. During entomological surveillance for West Nile virus, mosquitoes and other hematophagous insects were collected, including Phlebotomine sand flies. In this study, we report the results of Phlebotomine sand fly identification during the entomological surveillance conducted from 2017 to 2019.

Methods

The northeastern plain of Italy was divided by a grid with a length of 15 km, and a CO2-CDC trap was placed in each geographical unit. The traps were placed ~ 15 km apart. For each sampling site, geographical coordinates were recorded. The traps were operated every two weeks, from May to November. Sand flies collected by CO2-CDC traps were identified by morphological and molecular analysis.

Results

From 2017 to 2019, a total of 303 sand flies belonging to the species Phlebotomus perniciosus (n = 273), Sergentomyia minuta (n = 5), P. mascittii (n = 2) and P. perfiliewi (n = 2) were collected, along with 21 unidentified specimens. The trend for P. perniciosus collected during the entomological surveillance showed two peaks, one in July and a smaller one in September. Sand flies were collected at different altitudes, from −2 m above sea level (a.s.l.) to 145 m a.s.l. No correlation was observed between altitude and sand fly abundance.

Conclusions

Four Phlebotomine sand fly species are reported for the first time from the northeastern plain of Italy. Except for S. minuta, the sand fly species are competent vectors of Leishmania parasites and other arboviruses in the Mediterranean Basin. These findings demonstrate the ability of sand flies to colonize new environments previously considered unsuitable for these insects. Even though the density of the Phlebotomine sand fly population in the plain areas is consistently lower than that observed in hilly and low mountainous areas, the presence of these vectors could herald the onset of epidemic outbreaks of leishmaniasis and other arthropod-borne diseases in areas previously considered non-endemic.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13071-021-04652-2.

Keywords: Phlebotomus perniciosus, Phlebotomus mascittii, Phlebotomus perfiliewi, Sergentomyia minuta, Lowland, Italy

Background

Phlebotomine sand flies (Diptera: Psychodidae) are hematophagous insects and vectors of leishmaniasis and other bacterial and viral diseases [1–3]. In the Mediterranean region, they are the main vector of Leishmania infantum, the causative agent of canine leishmaniasis (CanL) and zoonotic human cutaneous (CL) and visceral leishmaniasis (VL) [2, 4, 5].

Different species of the genus Phlebotomus are implicated in the transmission of Mediterranean Leishmania infantum, including Phlebotomus ariasi, P. balcanicus, P. kandelakii, P. langeroni, P. neglectus, P. perfiliewi, P. perniciosus, P. sergenti and P. tobbi [2, 6, 7].

Phlebotomine sand fly abundance and distribution are closely related to climate and environmental factors [8–10]. Recent climate and environmental changes have resulted in the geographical expansion of Mediterranean L. infantum vectors towards northern latitudes and higher altitudes in different European countries [2, 6].

In Italy, CanL is endemic in the central and southern regions and the islands. Since the 1990s, new foci of CanL have been observed in the northern part of the country, previously considered non-endemic [11–17]. Entomological surveys conducted in these regions have confirmed the geographical expansion of Phlebotomine sand flies to northern latitudes: P. perniciosus was the most widespread species in both pre-Alpine and pre-Apennine territories, while P. neglectus was present only in pre-Alpine and P. perfiliewi in pre-Apennine sites [14]. These studies confirmed the most suitable habitat for these vectors is represented by hilly and low mountainous areas [11–13, 15, 18–20].

Among arthropod-borne diseases, mosquito-borne diseases (MBD) are endemic in northern Italy, in particular West Nile virus (WNV), a primarily avian virus, which has caused endemic outbreaks resulting in human and animal mortality [21]. After the first outbreak of West Nile disease [22], the Italian government developed an integrated surveillance plan that targeted birds, domestic poultry, horses, humans and mosquitoes [21], with the aim of early detection of viral circulation and reducing the risk of infection in humans [23, 24].

An entomological surveillance for WNV and other mosquito-borne viruses (Usutu, Dengue, Zika and mosquito-borne flaviviruses) was carried out by collecting host-seeking mosquitoes by traps. During the surveillance, other hematophagous insects were accidentally collected, including Phlebotomine sand flies. Following the first findings of sand fly specimens, we decided to keep them aside for identification. We did not perform any investigation to see whether the collected specimens were infected by Leishmania parasites, because VL, CL and CanL are notifiable diseases according to Italian Health Ministry regulations, and during the surveillance period there were no reported cases of Leishmania infection in the study area.

Herein, we report the results of Phlebotomine sand fly collection and identification during entomological surveillance for WNV conducted in the Friuli Venezia Giulia (FVG) and Veneto regions from 2017 to 2019.

Materials and methods

Study area

The study was conducted in the plain area (altitude below 300 m above sea level [a.s.l.]) of the FVG and Veneto regions. This area is characterized by a continental climate with hot summers and generally cold winters. Temperatures exceed 30 °C in summer and drop to values under −10 °C in winter, remaining under 0 °C even during the day. Precipitation levels range between 600 and 800 mm/year [19].

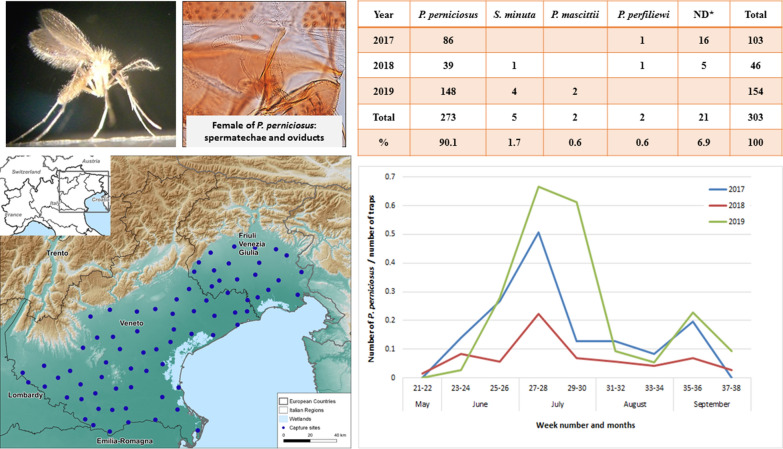

The area was divided into a grid with a length of 15 km. A trap for collecting host-seeking mosquitoes was placed in each geographical unit. The traps were placed ~ 15 km apart. The number of traps was adjusted each year according to WNV epidemiology, with 71, 72 and 75 traps in operation in 2017, 2018 and 2019, respectively. An example of the distribution of the traps is reported in Fig. 1. Waypoints were included in the map using QGIS software [25].

Fig. 1.

Geographical location of CO2-CDC traps in northeastern Italy in 2019

The geographical coordinates and a brief description of the environment (farm, rural or urbanized area) were recorded for each site.

Sand fly collection and identification

Collections were carried out using a CO2-CDC trap (IMT®—Italian Mosquito Trap, Cantù, Italy). CDC traps were filled with dry ice pellets as a source of carbon dioxide in order to attract hematophagous insects and powered by a 12-V battery. Traps were operated from sunset to sunrise, every two weeks. The entomological surveillance started each year from the second week of May and continued until the first week of November. Insects were delivered to the laboratory in dry ice, to preserve the integrity of the viral RNA in mosquito vectors.

From 2017 to 2019, all collected sand flies were systematically preserved in 70% ethanol and morphologically identified at the end of the monitoring season. In addition to morphological identification, sand flies collected in 2019 were also identified by molecular assay.

For morphological identification, the heads and genitalia of each sand fly were dissected, clarified using chloral hydrate and acetic acid, and slide-mounted in Hoyer’s solution, as described by Dantas-Torres et al. [26]. Sand flies were examined with an optical microscope and identified using morphological keys [26] based on specific features of the pharynx and genitalia (spermathecae in females and external genitalia in males).

For molecular identification, the thorax, wings and legs were maintained on a petri dish at room temperature (20 °C) for at least 1 hour and rinsed twice with phosphate-buffered solution (PBS) to remove the alcohol. After rinsing, the specimens were transferred to a 2 ml Eppendorf® tube with a sterile steel ball and stored at −20 °C, before proceeding with DNA extraction. DNA was extracted from each specimen using the MagMAX™ Pathogen RNA/DNA Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and Hamilton Microlab STARlet automated extraction instrument. Amplification and sequencing were performed according to the procedure described by Jalali et al. [27].

Statistical analysis

Since the number of Phlebotomine sand flies other than P. perniciosus was very low, this species was considered for statistical analysis. Linear regression was carried out with the independent variable (altitude) plotted against the abundance of P. perniciosus as the dependent variable, while the chi-square test was used to compare the percentages of environments positive for P. perniciosus.

Results

The geographical coordinates (longitude, latitude and altitude) for each sampling site and a brief description of the environment (farms, rural or urbanized area) are reported in Additional file 1: Table S1.

Regarding species identification, a total of 303 sand flies belonging to the species P. perniciosus (n = 273), S. minuta (n = 5), P. mascittii (n = 2) and P. perfiliewi (n = 2) were collected. Morphological identification of 21 specimens (collected in 2017 and 2018) was not possible due to damage to anatomical structures needed for this purpose (Table 1).

Table 1.

Species and number of Phlebotomine sand flies collected per year

| Year | P. perniciosus | S. minuta | P. mascittii | P. perfiliewi | ND | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 86 | 1 | 16 | 103 | ||

| 2018 | 39 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 46 | |

| 2019 | 148 | 4 | 2 | 154 | ||

| Total | 273 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 21 | 303 |

| % | 90.1 | 1.7 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 6.9 | 100 |

ND not determined

Molecular identification, performed on all 154 specimens collected in 2019, confirmed the results of morphological identification (Table 1) and it was very helpful for the identification of damaged samples.

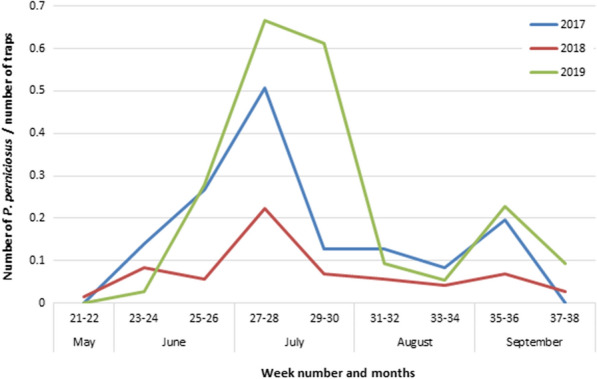

Sand flies were collected from late May to September, with a peak in July (weeks 27–28 in 2017 and 2018, weeks 27–30 in 2019) and a smaller peak in September (weeks 35–36 in 2017 and 2019). The trend for P. perniciosus collected during entomological surveillance is shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Trend of P. perniciosus in 2017, 2018 and 2019

Sand flies were collected at different altitudes, from −2 m a.s.l. (Porto Viro, Rovigo) to 145 m a.s.l. (Thiene, Vicenza). No correlation was observed (correlation coefficient = 0.20) between altitude and P. perniciosus abundance, as shown in Additional file 2: Figure S1.

Sand flies were collected from farms, rural and urbanized areas. The number of sites positive for Phlebotomine sand flies for each environmental type is reported in Additional file 3: Table S2.

Discussion

In this study, we report for the first time the presence of Phlebotomine sand flies in the northeastern plain of Italy. Although other studies have reported sand flies in these regions, they were collected from hilly and low mountainous areas [11–13, 15, 18–20]. An increase in the distribution area of sand flies was observed only in the neighboring region, Emilia-Romagna, where P. perfiliewi and P. perniciosus were collected from the whole regional territory [28, 29].

In this study, P. perniciosus was the dominant species, while P. neglectus was not isolated during the entomological surveillance, although it is considered quite a common species in northern Italy [11–14, 18, 19]. Phlebotomus mascittii was observed for the first time in FVG (Premariacco, 112 m a.s.l.), and P. perfiliewi was detected for the first time in the FVG (Caneva, 33 m a.s.l.) and Veneto regions (Badia Polesine, 8 m a.s.l.). Sergentomyia minuta was also reported for the first time in the FVG region, in the village of Budoia (135 m a.s.l.); this species was previously found in the Veneto region in the locality of Calaone (178 m a.s.l.) [18, 19], but in this study it was observed in sites at lower altitudes, such as Porto Viro (2 m a.s.l.) and Albignasego (8 m a.s.l.).

Since S. minuta is a herpetophilic sand fly, its role in the transmission of L. infantum is not important [30], unlike P. perfiliewi, P. mascittii and P. perniciosus.

It is noteworthy that P. perfiliewi had never been reported in these regions, although it is the most abundant species in the neighboring region (Emilia Romagna) [31] and in central [32] and southern Italy [33].

Phlebotomus perfiliewi is a proven vector of L. infantum and its presence was documented in several outbreaks of CanL in the Emilia Romagna region [28, 29]. The presence of P. perfiliewi was also observed in outbreaks of human VL, caused by L. infantum strains other than those isolated from dogs [31]. This finding suggests the involvement of P. perfiliewi in a sylvatic cycle of leishmaniasis in which wildlife plays the role of reservoir [34] rather than dogs [31].

In the Emilia Romagna region, P. perfiliewi is a vector of the Toscana virus (TOSV) and other phleboviruses [35, 36] and it was also found to be positive for a trypanosome related to Trypanosoma theileri (Kinetoplastea: Trypanosomatidae) [37]. However, in the FVG and Veneto regions, P. perfiliewi abundance is so limited that it is unlikely to play a role as vector of Leishmania parasites or arboviruses.

Phlebotomus mascittii is not a proven vector of leishmaniasis [38], although recent detection of L. infantum DNA in specimens of P. mascittii from Austria [39] and Italy [40] may support possible competence in the transmission [41]. Thus, its role as Leishmania vector should be considered, at least in areas where it is abundant and Leishmania-infected dogs are imported from endemic countries [42].

Phlebotomus perniciosus is an efficient vector of L. infantum in Italy [43] and in southwestern European countries [6]. In experimental conditions, it is a competent vector of L. tropica, causing CL [41, 44]. It is also a vector of arboviruses such as TOSV [45].

In the study area, the trend in P. perniciosus during the entomological surveillance was bimodal, with a peak at the beginning and the end of the warm season. A bimodal trend in P. perniciosus was observed in Mediterranean sites located at low latitudes; at intermediate or higher latitudes, single large peaks or two partially confluent peaks have been recorded [6]. However, there are examples of variable P. perniciosus distribution patterns even at higher latitudes and a sharp bimodal trend, attributable to climate warming, was recently reported in southern France. Climate change might enhance the risk of pathogen transmission because of the higher sand fly density and the longer activity season [46].

It is common knowledge that the distribution of sand flies is heavily influenced by altitude [47].

Considering the difference in sand fly abundance, the number of specimens collected in 2019 was higher than in previous years because of the addition of new sites, with a higher number of sand flies collected.

In northern Italy, P. perniciosus was detected at high densities in hilly and low mountains sites [14]. This finding was confirmed by the ecological niche model described by Signorini et al. [19], where the highest relative probability of P. perniciosus occurrence was predicted in hilly areas between 100 and 300 m a.s.l. In our study, P. perniciosus was also present in the lowlands at 7 m a.s.l. (Brugine, Veneto region), indicating that altitude alone is an inadequate predictor variable of sand fly abundance [48]. Our findings also suggest an adaptation of sand flies to new environments, characterized by low-altitude sites with a continental climate and peri-urban environment.

The ability of Phlebotomine sand flies to adapt to environmental changes was observed in southern France, where Prudhomme et al. [49] observed that the sand fly population did not differ significantly from what was reported by previous studies conducted in the same area, even though the habitat has been transformed by urbanization, with reduced host abundance and increased temperature over the years.

The adaptation of Phlebotomine sand flies to human dwellings was also observed in southern Italy, enhancing the potential risk of exposure to L. infantum among local inhabitants [33].

Certainly, some critical points are identified in the collection method: although CO2-CDC traps are considered more effective than others (i.e. sticky traps or CDC-light traps) in collecting sand flies [18], sampling sites were not located in areas suitable for these insects. Therefore, entomological surveillance focusing on sand fly detection is needed to have a more realistic picture of its distribution in the plain area.

The detection of sand flies in new areas traditionally considered as non-endemic represents important data for public health. In light of the growing movement of dogs from or to endemic areas (adoptions or tourism) [42], in addition to a proper awareness among veterinarians and public health authorities, dog owners should be aware of the health risk and should be adequately educated in the correct use of preventive measures against sand fly bites. Although outbreaks of L. infantum are more frequently described in non-endemic areas, dog owner education programs on the correct use of preventive measures against sand fly bites are found to achieve successful results in controlling the spread of the infection [12, 20].

Conclusions

Phlebotomine sand flies are reported for the first time from the northeastern plain of Italy. Except for S. minuta, the sand fly species are competent vectors of L. infantum and other arboviruses in the Mediterranean Basin.

Although the density of the Phlebotomine sand fly population in the plain areas is consistently lower than that observed in hilly and low mountainous areas, the presence of the vector in these environments could herald the onset of epidemic outbreaks of leishmaniasis and other diseases in areas previously considered non-endemic.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1. List of sampling sites, with geographical coordinates and environmental description and monitoring years.

Additional file 2: Figure S1. Scatter plot of altitude (m) and mean number of P. perniciosus.

Additional file 3: Table S2. Number of sites positive for Phlebotomine sand flies in each environmental type.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Sonia Accordi (IZSVe), Francesca Bruno (IZSVe), Valentina Fin (IZSVe), Francesco Gradoni (IZSVe), Sara Gisella Omodeo (EFSA) and Maria Luisa Vitale (Entostudio) for their help in sampling and Paolo Mulatti (IZSVe) for creating the map.

Abbreviations

- CanL

Canine leishmaniasis

- CL

Cutaneous leishmaniasis

- VL

Visceral leishmaniasis

- MBD

Mosquito-borne diseases

- WNV

West Nile virus

- FVG

Friuli Venezia Giulia

- a.s.l.

Above sea level

Authors’ contributions

AM and FM conceived the study. AM and MB carried out the sampling. AM and MG performed morphological identification, and FT and SR performed molecular analysis. AM wrote the first draft of the manuscript. FM, MG, GS and MB reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Regional Prevention Plans entitled “Entomological Surveillance of vector-borne diseases” in the Veneto and Friuli Venezia Giulia Regions.

Availability of data and materials

The data supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its additional file.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Depaquit J, Grandadam M, Fouque F, Andry PE, Peyrefitte C. Arthropod-borne viruses transmitted by Phlebotomine sandflies in Europe: a review. Eurosurveillance. 2010;15:40–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maroli M, Feliciangeli MD, Bichaud L, Charrel RN, Gradoni L. Phlebotomine sandflies and the spreading of leishmaniases and other diseases of public health concern. Med Vet Entomol. 2013;27:123–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.2012.01034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ready PD. Biology of phlebotomine sand flies as vectors of disease agents. Annu Rev Entomol. 2013;58:227–250. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-120811-153557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Killick-Kendrick R. Phlebotomine vectors of the leishmaniasis: a review. Med Vet Entomol. 1990;4:1–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.1990.tb00255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ready PD. Leishmaniasis emergence in Europe. Eurosurveillance. 2010;15:29–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alten B, Maia C, Afonso MO, Campino L, Jiménez M, González E, et al. Seasonal dynamics of Phlebotomine sand fly species proven vectors of Mediterranean Leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania infantum. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:1–22. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Antoniou M, Gramiccia M, Molina R, Dvorak V, Volf P. The role of indigenous phlebotomine sandflies and mammals in the spreading of leishmaniasis agents in the Mediterranean region. Eurosurveillance. 2013;18:1–8. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES2013.18.30.20540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dujardin JC, Campino L, Cañavate C, Dedet JP, Gradoni L, Soteriadou K, et al. Spread of vector-borne diseases and neglect of leishmaniasis. Europe Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:1013–1018. doi: 10.3201/eid1407.071589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ready PD. Leishmaniasis emergence and climate change. OIE Rev Sci Tech. 2008;27:399–412. doi: 10.20506/rst.27.2.1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fischer D, Moeller P, Thomas SM, Naucke TJ, Beierkuhnlein C. Combining climatic projections and dispersal ability: a method for estimating the responses of sandfly vector species to climate change. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5:e1407. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Capelli G, Baldelli R, Ferroglio E, Genchi C, Gradoni L, Gramiccia M, et al. Monitoring of canine leishmaniasis in northern Italy: an update from a scientific network. Parassitologia. 2004;46:193–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cassini R, Signorini M, di Regalbono AF, Natale A, Montarsi F, Zanaica M, et al. Preliminary study of the effects of preventive measures on the prevalence of Canine Leishmaniosis in a recently established focus in northern Italy. Vet Ital. 2013;49:157–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferroglio E, Maroli M, Gastaldo S, Mignone W, Rossi L. Canine leishmaniasis, Italy. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:1618–1620. doi: 10.3201/eid1110.040966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maroli M, Rossi L, Baldelli R, Capelli G, Ferroglio E, Genchi C, et al. The northward spread of leishmaniasis in Italy: evidence from retrospective and ongoing studies on the canine reservoir and phlebotomine vectors. Trop Med Int Heal. 2008;13:256–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2007.01998.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morosetti G, Bongiorno G, Beran B, Scalone A, Moser J, Gramiccia M, et al. Risk assessment for canine leishmaniasis spreading in the north of Italy. Geospat Health. 2009;4:115–127. doi: 10.4081/gh.2009.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Otranto D, Capelli G, Genchi C. Changing distribution patterns of canine vector-borne diseases in Italy: Leishmaniosis vs. dirofilariosis. Parasit Vect. 2009;2:1–8. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-2-S1-S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Romi R. Arthropod-borne diseases in Italy: from a neglected matter to an emerging health problem. Ann Ist Super Sanità. 2010;46:436–443. doi: 10.4415/ANN_10_04_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Signorini M, Drigo M, Marcer F, di Regalbono AF, Gasparini G, Montarsi F, et al. Comparative field study to evaluate the performance of three different traps for collecting sand flies in northeastern Italy. J Vector Ecol. 2013;38:374–378. doi: 10.1111/j.1948-7134.2013.12053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Signorini M, Cassini R, Drigo M, di Regalbono AF, Pietrobelli M, Montarsi F, et al. Ecological niche model of Phlebotomus perniciosus, the main vector of canine leishmaniasis in north-eastern Italy. Geospat Health. 2014;9:193–201. doi: 10.4081/gh.2014.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simonato G, Marchiori E, Marcer F, Ravagnan S, Danesi P, Montarsi F, et al. Canine Leishmaniosis control through the promotion of preventive measures appropriately adopted by citizens. J Parasitol Res. 2020;2020:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2020/8837367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Engler O, Savini G, Papa A, Figuerola J, Groschup MH, Kampen H, et al. European surveillance for West Nile virus in mosquito populations. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2013;10:4869–4895. doi: 10.3390/ijerph10104869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Autorino GL, Battisti A, Deubel V, Ferrari G, Forletta R, Giovannini A, et al. West Nile virus epidemic in horses, Tuscany region. Italy Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8:1372–1378. doi: 10.3201/eid0812.020234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pisani G, Cristiano K, Pupella S, Liumbruno GM. West Nile virus in Europe and safety of blood transfusion. Transfus Med Hemotherapy. 2016;43:158–167. doi: 10.1159/000446219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paternoster G, Tomassone L, Tamba M, Chiari M, Lavazza A, Piazzi M, et al. The degree of one health implementation in the West Nile virus integrated surveillance in northern Italy, 2016. Front Public Heal. 2017;5:1–10. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2017.00236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.QGIS. https://www.qgis.org. Accessed 20 Jan 2021.

- 26.Dantas-Torres F, Tarallo VD, Otranto D. Morphological keys for the identification of Italian Phlebotomine sand flies (Diptera: Psychodidae: Phlebotominae) Parasit Vect. 2014;7:1–6. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-7-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jalali SK, Ojha R, Venkatesan T. New horizons in insect science: towards sustainable pest management. New Delhi: Springer; 2015. pp. 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baldelli R, Piva S, Salvatore D, Parigi M, Melloni O, Tamba M, et al. Canine leishmaniasis surveillance in a northern Italy kennel. Vet Parasitol (Elsevier B.V) 2011;179:57–61. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.01.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Santi A, Renzi M, Baldelli R, Calzolari M, Caminiti A, Dell’anna S, et al. A surveillance program on canine leishmaniasis in the public kennels of Emilia-Romagna region, northern Italy. Vect Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2014;14:206–211. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2013.1362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barón SD, Morillas-Márquez F, Morales-Yuste M, Díaz-Sáez V, Irigaray C, Martín-Sánchez J. Risk maps for the presence and absence of Phlebotomus perniciosus in an endemic area of leishmaniasis in southern Spain: implications for the control of the disease. Parasitology. 2011;138:1234–1244. doi: 10.1017/S0031182011000953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Calzolari M, Carra E, Rugna G, Bonilauri P, Bergamini F, Bellini R, et al. Isolation and molecular typing of Leishmania infantum from Phlebotomus perfiliewi in a reemerging focus of leishmaniasis, northeastern Italy. Microorganisms. 2019;7:644. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms7120644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maresca C, Scoccia E, Barizzone F, Catalano A, Mancini S, Pagliacci T, et al. A survey on canine Leishmaniasis and Phlebotomine sand flies in central Italy. Res Vet Sci Elsevier Ltd. 2009;87:36–38. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dantas-Torres F, Tarallo VD, Latrofa MS, Falchi A, Lia RP, Otranto D. Ecology of phlebotomine sand flies and Leishmania infantum infection in a rural area of southern Italy. Acta Trop (Elsevier B.V.) 2014;137:67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2014.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Millán J, Ferroglio E, Solano-Gallego L. Role of wildlife in the epidemiology of Leishmania infantum infection in Europe. Parasitol Res. 2014;113:2005–2014. doi: 10.1007/s00436-014-3929-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Calzolari M, Angelini P, Finarelli AC, Cagarelli R, Bellini R, Albieri A, et al. Human and entomological surveillance of Toscana virus in the Emilia-Romagna region, Italy, 2010 to 2012. Eurosurveillance. 2014;19:14–22. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES2014.19.48.20978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Calzolari M, Chiapponi C, Bellini R, Bonilauri P, Lelli D, Moreno A, et al. Isolation of three novel reassortant phleboviruses, Ponticelli I, II, III, and of Toscana virus from field-collected sand flies in Italy. Parasit Vect Parasites Vect. 2018;11:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s13071-017-2573-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Calzolari M, Rugna G, Clementi E, Carra E, Pinna M, Bergamini F, et al. Isolation of a trypanosome related to Trypanosoma theileri (Kinetoplastea: Trypanosomatidae) from Phlebotomus perfiliewi (Diptera: Psychodidae) Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2018/2597074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Melaun C, Krüger A, Werblow A, Klimpel S. New record of the suspected leishmaniasis vector Phlebotomus (Transphlebotomus) mascittii Grassi, 1908 (Diptera: Psychodidae: Phlebotominae)—the northernmost phlebotomine sandfly occurrence in the Palearctic region. Parasitol Res. 2014;113:2295–2301. doi: 10.1007/s00436-014-3884-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Obwaller AG, Karakus M, Poeppl W, Töz S, Özbel Y, Aspöck H, et al. Could Phlebotomus mascittii play a role as a natural vector for Leishmania infantum? New data. Parasit Vect. 2016;9:1–6. doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1750-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zanet S, Sposimo P, Trisciuoglio A, Giannini F, Strumia F, Ferroglio E. Epidemiology of Leishmania infantum, Toxoplasma gondii, and Neospora caninum in Rattus rattus in absence of domestic reservoir and definitive hosts. Vet Parasitol Elsevier B.V. 2014;199:247–249. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2013.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vaselek S, Volf P. Experimental infection of Phlebotomus perniciosus and Phlebotomus tobbi with different Leishmania tropica strains. Int J Parasitol. 2019;49:831–835. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2019.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Naucke TJ, Lorentz S, Rauchenwald F, Aspöck H. Phlebotomus (Transphlebotomus) mascittii Grassi, 1908, in Carinthia: first record of the occurrence of sandflies in Austria (Diptera: Psychodidae: Phlebotominae) Parasitol Res. 2011;109:1161–1164. doi: 10.1007/s00436-011-2361-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maroli M, Gramiccia M, Gradoni L, Read PD, Smith DF, Aquino C. Natural infections of phlebotomine sandflies with Trypanosomatidae in central and south Italy. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1988;82:227–228. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(88)90421-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bongiorno G, Di Muccio T, Bianchi R, Gramiccia M, Gradoni L. Laboratory transmission of an Asian strain of Leishmania tropica by the bite of the southern European sand fly Phlebotomus perniciosus. Int J Parasitol Aust Soc Parasitolog Inc. 2019;49:417–421. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2018.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Charrel RN, Berenger JM, Laroche M, Ayhan N, Bitam I, Delaunay P, et al. Neglected vector-borne bacterial diseases and arboviruses in the Mediterranean area. N Microbes N Infect Elsevier Ltd. 2018;26:S31–S36. doi: 10.1016/j.nmni.2018.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cotteaux-Lautard C, Leparc-goffart I, Berenger JM, Plumet S, Pages F. Phenology and host preferences Phlebotomus perniciosus (Diptera: Phlebotominae) in a focus of Toscana virus (TOSV) in South of France. Acta Trop Elsevier B.V. 2016;153:64–69. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2015.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guernaoui S, Boumezzough A, Laamrani A. Altitudinal structuring of sand flies (Diptera: Psychodidae) in the High-Atlas mountains (Morocco) and its relation to the risk of leishmaniasis transmission. Acta Trop. 2006;97:346–351. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Risueño J, Muñoz C, Pérez-Cutillas P, Goyena E, Gonzálvez M, Ortuño M, et al. Understanding Phlebotomus perniciosus abundance in south-east Spain: assessing the role of environmental and anthropic factors. Parasit Vect. 2017;10:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s13071-017-2135-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Prudhomme J, Rahola N, Toty C, Cassan C, Roiz D, Vergnes B, et al. Ecology and spatiotemporal dynamics of sandflies in the Mediterranean Languedoc region (Roquedur area, Gard, France) Parasit Vect. 2015;8:1–14. doi: 10.1186/s13071-015-1250-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. List of sampling sites, with geographical coordinates and environmental description and monitoring years.

Additional file 2: Figure S1. Scatter plot of altitude (m) and mean number of P. perniciosus.

Additional file 3: Table S2. Number of sites positive for Phlebotomine sand flies in each environmental type.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its additional file.