Abstract

This is the case report of a 50-year-old female with no systemic comorbidities who presented to the eye clinic with a 1-month history of right-sided eye pain and visual loss. Examination revealed no signs of inflammation in the right eye, with no proptosis or conjunctival injection. A relative afferent pupillary defect was present with no inflammatory cells in the vitreous. On fundoscopy, there was a swollen disc, a large superior creamy white subretinal mass associated with a shallow overlying retinal detachment. B-scan ultrasonography confirmed the presence of a subretinal mass. Hematological investigations revealed an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Infective and autoimmune markers were negative. A diagnosis was made of nodular posterior scleritis and the patient was treated with intravenous corticosteroids initially, and subsequently switched to oral corticosteroids. There was complete resolution of the mass with optic atrophy as a result. Posterior nodular scleritis is an extremely rare potentially vision-threatening ocular condition that requires multimodal investigations to diagnose and treat appropriately.

Keywords: Nodular scleritis, posterior scleritis, subretinal mass

Introduction

Posterior scleritis is a rare, potentially blinding inflammatory ocular condition that is often underdiagnosed.[1,2,3] There are two clinical forms of the condition, namely a diffuse and a nodular form.[1] The nodular form of this scleral inflammation is extremely rare (13% of posterior scleritis over 22 years)[1] and the diagnosis is often delayed due to the overlap in clinical presentation with other clinical entities.[2] Nodular posterior scleritis is often confused with choroidal tumors such as melanomas and haemangiomas as well as inflammatory masses such as granulomas.[4] The aim of publishing our case report was to report the unique findings of this rare presentation of posterior scleritis and to review the available literature on nodular posterior scleritis.

Case Report

A 50-year-old dark skin female with no comorbidities presented to the eye clinic at Charlotte Maxeke Johannesburg Academic Hospital complaining of a 1-month history of right-sided eye pain associated with a decrease in visual acuity. The pain radiated to the side of her head. The rest of the patient's history was unremarkable. On examination, her unaided visual acuity was hand movements and 6/9 in her right and left eyes, respectively. There was no associated proptosis, conjunctival injection, or diplopia. Her extraocular movements were mildly restricted in abduction and elevation. She had a relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD) with no vitritis in her right eye. She had normal intraocular pressures (IOPs). Her fundus examination revealed a swollen optic disc with a shallow retinal detachment overlying a large creamy white superior subretinal mass [Figure 1a and b]. B-scan ultrasonography revealed an approximately 3 mm by 6 mm subretinal mass with overlying subretinal fluid [Figure 2]. Blood workup revealed an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 123 mm/h (normal <20 mm/h) with a normal full blood count, urea and electrolytes, and liver function tests. Auto-immune markers were also negative. The patient had a nonreactive tuberculin skin test, syphilis serology was negative, and a normal chest X-ray. Computed tomography scan of the brain and orbits revealed a rim-enhancing multiseptated, well-defined hypodense soft-tissue mass. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) on admission is shown in Figure 3.

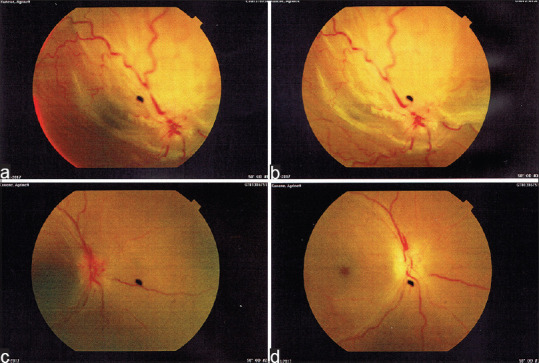

Figure 1.

(a and b) Fundus pictures of subretinal mass on admission. (c) After 3 days of intravenous steroid treatment. (d) After 1 month of steroid treatment (initially intravenous and subsequently oral treatment)

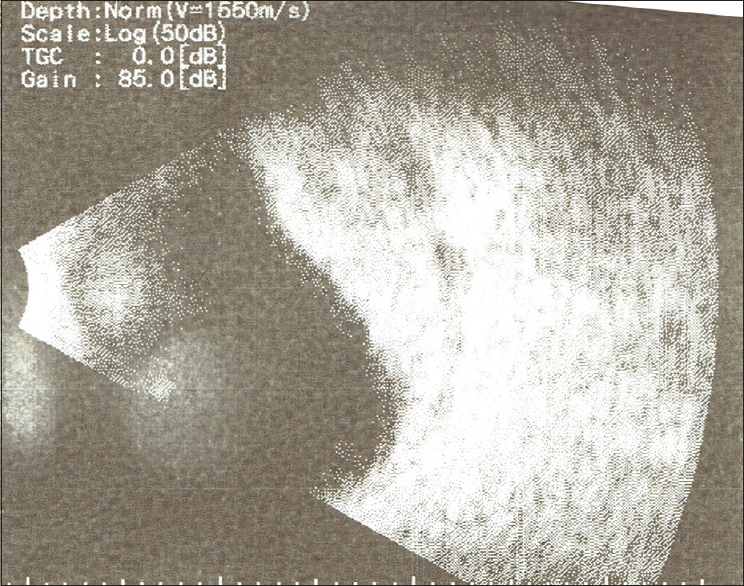

Figure 2.

B-scan ultrasonography showing the hyperechoic subretinal mass

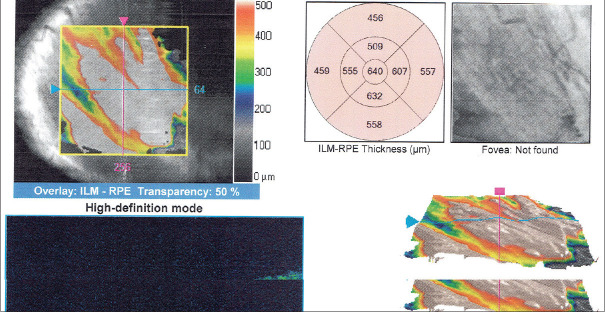

Figure 3.

Macula optical coherence tomography of the right eye pre-treatment with systemic steroids

The patient was admitted and placed on intravenous methylprednisolone to treat a suspected nodular posterior scleritis. She was subsequently discharged and received oral prednisone, 1 mg/kg initially, and subsequently over 1 month. The patient responded well with complete resolution of the mass as well as the subretinal fluid [Figure 1C]. At her 1-month follow-up postadmission, she was no longer complaining of any eye pain and had a best-corrected visual acuity of counting fingers in her right eye and 6/6 in her left eye. She had full extraocular movements in both of her eyes, but a RAPD was still present in her right eye. Of note, there was no subretinal mass visible on clinical examination, B-scan ultrasound, or OCT [Figure 4]. She had optic disc pallor with loss of the foveal reflex and nonspecific mottling at her macula [Figure 1D].

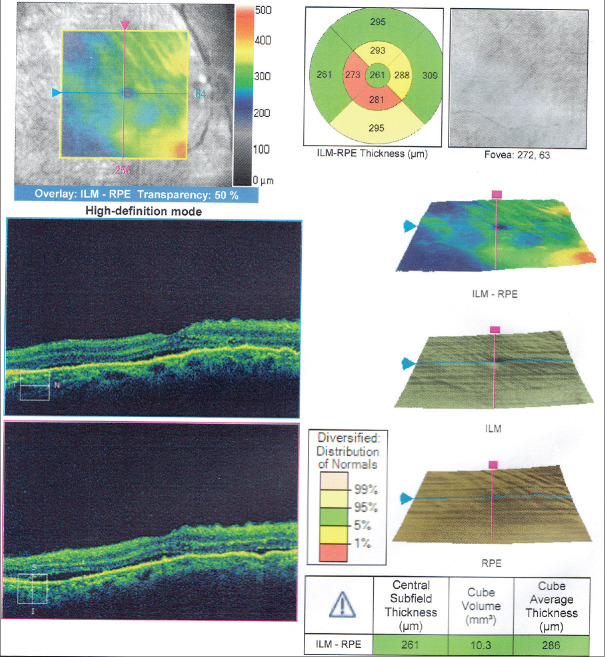

Figure 4.

Macula optical coherence tomography of the right eye post-treatment with systemic steroids

Discussion

Posterior scleritis occurs mainly in females during the fifth decade of life.[1,2,5,6] The nodular form of posterior scleritis, however, has a slightly older mean age with onset occurring in the sixth decade of life.[2] Most cases of posterior scleritis are unilateral (two-thirds) and idiopathic (>70%).[1,6] The most common clinical signs of posterior scleritis are optic disc swelling, choroidal folds, a visible subretinal mass, elevated IOP, and an associated anterior scleritis.[1,3,6] A nodular posterior scleritis as seen in our patient can mimic a subretinal mass, often with an overlying retinal detachment.[1] This variant is, however, very rare with few case reports published in the literature.[6,7,8] Optic disc swelling and macular involvement usually result in central visual loss as with our patient. Agrawal et al. showed that no patients in their case series with the nodular variant of posterior scleritis presented with optic disc swelling.[2] Optic disc swelling was, however, seen in our patient and we attribute this to the large size of the mass as well as the juxtapapillary location which was different to the series by Agrawal et al. Nodular posterior scleritis is usually pale in color; however, this can be confused with an amelanotic choroidal melanoma.[2] A high IOP can be caused by uveal effusions causing secondary angle closure.[1] The presence of vitritis is not a reliable sign as it has been reported by McCluskey et al. to be exceedingly rare, occurring in only 2% of patients with posterior scleritis, while Agrawal et al. have reported it to be 40%.[1,2] It must, however, be noted that the former series included both nodular and diffuse subtypes, while the latter series focused on only the nodular subtype.

Imaging is a critical aid in the diagnosis of posterior scleritis as it is possible to differentiate it from other subretinal masses. On B-scan ultrasonography, posterior nodular scleritis is usually sessile and single lobed as opposed to other tumors which can be dome/collar-stud shaped and multilobed. There is also no choroidal excavation present in contrast to choroidal melanoma in which it is present.[2] Fluorescein angiography (FA) usually shows no dual circulation that can be seen with melanomas and the tumors in nodular posterior scleritis are usually hypofluorescent.[1,2] A FA was not performed in the case of our patient as it was not deemed necessary since the diagnosis had been made with a great degree of certainty. OCT is of limited value in nodular posterior scleritis due to the size and location of the lesions.[2] It is, however, an easy and inexpensive test to perform. OCT in our patient showed a retinal detachment with underlying subretinal fluid.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a useful adjunct for the diagnosis of nodular posterior scleritis, especially when the diagnosis of choroidal melanoma is considered. MRI shows thickening of the sclera with a low signal intensity of the tumor on both T1- and T2-weighted images when compared to the vitreous. In contrast, in melanoma, a high signal intensity is shown on T1-weighted images and a low signal intensity is shown on T2-weighted images.[2]

The most commonly associated systemic disease with posterior scleritis is rheumatoid arthritis, although other autoimmune diseases (e.g., systemic lupus erythematosus) and even systemic malignancies (e.g., lymphoma) can be associated with posterior scleritis.[1,2] If the diagnosis is still unclear after all investigations, then a choroidal biopsy can be considered. A choroidal biopsy can be performed both transsclerally and through pars plana vitrectomy.[2,9] This must, however, be undertaken with due consideration since there are potential complications such as retinal tears, retinal detachments, and even phthisis bulbi.[9]

Options for treatment include systemic nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, systemic steroids in either local, oral or intravenous forms, and immunomodulatory therapy, especially if long-term treatment is required.[1,2] Systemic steroids are usually reserved for cases in which the scleritis is threatening the central vision.[2] In our case, the patient already had poor vision from the disc and macular involvement and we opted for intravenous steroid administration as we thought that this would lead to the most speedy resolution of the nodular posterior scleritis. There have been mixed reports in the literature regarding the complete resolution of the subretinal mass with some reports showing complete resolution most notably the case series by Agrawal et al. showing a fluctuating course in terms of the size of the mass.[2,4,10] After systemic steroid therapy (both intravenous and oral steroid), our patient had complete resolution of her signs. Her optic disc, however, was pale with a poor final visual outcome.

In conclusion, nodular posterior scleritis is a rare and potentially blinding visual condition. It can, however, be managed effectively if the diagnosis is made timeously. Clinical examination with directed imaging investigations is critical to making the diagnosis. Although most cases are idiopathic, the most commonly associated disease is rheumatoid arthritis. Management should be instituted early, although complete resolution of the mass does not always occur.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to acknowledge the help and assistance of Ms. Linda Malan for acquiring the images and scans on the patient.

References

- 1.McCluskey PJ, Watson PG, Lightman S, Haybittle J, Restori M, Branley M. Posterior scleritis: Clinical features, systemic associations, and outcome in a large series of patients. Ophthalmology. 1999;106:2380–6. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90543-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agrawal R, Lavric A, Restori M, Pavesio C, Sagoo MS. Nodular posterior scleritis: Clinico-sonographic characteristics and proposed diagnostic criteria. Retina. 2016;36:392–401. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000000699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tanaka R, Kaburaki T, Ohtomo K, Takamoto M, Komae K, Numaga J, et al. Clinical characteristics and ocular complications of patients with scleritis in Japanese. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2018;62:517–24. doi: 10.1007/s10384-018-0600-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shukla D, Kim R. Giant nodular posterior scleritis simulating choroidal melanoma. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2006;54:120–2. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.25835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sainz de la Maza M, Jabbur NS, Foster CS. Severity of scleritis and episcleritis. Ophthalmology. 1994;101:389–96. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(94)31325-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gonzalez-Gonzalez LA, Molina-Prat N, Doctor P, Tauber J, Sainz de la Maza M, Foster CS. Clinical features and presentation of posterior scleritis: A report of 31 cases. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2014;22:203–7. doi: 10.3109/09273948.2013.840385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Derby GS. Massive granuloma of the sclera (Brawny Scleritis), with the report of an unusual case: Pathologic examination by Dr. F. H. Verhoeff. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1915;14:110–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Finger PT, Perry HD, Packer S, Erdey RA, Weisman GD, Sibony PA. Posterior scleritis as an intraocular tumour. Br J Ophthalmol. 1990;74:121–2. doi: 10.1136/bjo.74.2.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnston RL, Tufail A, Lightman S, Luthert PJ, Pavesio CE, Cooling RJ, et al. Retinal and choroidal biopsies are helpful in unclear uveitis of suspected infectious or malignant origin. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:522–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2002.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pérez-Campagne E, Guex-Crosier Y, Schalenbourg A, Uffer S, Zografos L. Giant nodular posterior scleritis compatible with ocular sarcoidosis simulating choroidal melanoma. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol. 2007;82:563–6. doi: 10.4321/s0365-66912007000900010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]