ABSTRACT

Seasonal influenza is an annually recurring threat to residents of long-term care facilities (LTCFs) since high age and chronic disease diminish immune response following vaccination. Although immunization of healthcare workers (HCWs) has proven to be an added value, coverage rates remain low. A ready-to-use instruction manual was designed to facilitate the implementation of interventions known to increase vaccination coverage in healthcare institutions. It includes easy-access vaccination, role model involvement, personalized promotional material, education and extensive communication. We evaluated this manual during the 2017-vaccination campaign in 11 LTCFs in Belgium. Vaccination coverage before and after the campaign was recorded by the LTCFs and the usefulness of the manual was assessed by interviewing the organizers of the local campaigns. Attitudes toward vaccination and reasons for vaccination were evaluated with a quantitative survey in HCWs before and after the campaign. The mean vaccination coverage reported by the LTCFs was 54% (range: 35–72%) in 2016 and 68% (range: 45–81%) in 2017. After the campaign, HCWs were less likely to expect side effects after influenza vaccination (OR (95%CI): 0.4 (0.2–0.9)) or to oppose vaccination (OR (95%CI): 0.3 (0.1–0.9)). The majority (>60%) indicated to be well informed about the risks of influenza and the efficacy of the vaccine. The main reason for vaccination in those who previously refused it was resident protection. The manual was found useful by the organizers of the campaigns. We conclude that the use of an intervention manual may support vaccination uptake and decrease perceived barriers toward influenza vaccination in countries without mandatory vaccination in HCWs.

KEYWORDS: Healthcare workers, influenza, vaccination, intervention manual, campaign, long-term care

Introduction

Institutionalized elderly often do not develop protective antibody titers after vaccination due to increased age, chronic disease or malnutrition.1,2 Hence, seasonal influenza remains an annual threat as well as complications such as pneumonia, exacerbation of underlying cardiopulmonary disease, hospitalization or even death.3 During nosocomial outbreaks, healthcare workers (HCWs) have an increased risk of acquiring influenza since they care for the infected residents.4 Since influenza can be transmitted even before the onset of symptoms, HCWs can unintentionally spread influenza. HCW vaccination is the most effective measure to prevent this. It may decrease morbidity and mortality in residents and can prevent HCW absenteeism.5–8 Despite these advantages and the recommendations made by public health authorities, vaccination coverage in HCWs remains generally low. It is about 65% in the United States and varies from 14% to 46% across Europe.9,10 Different strategies to improve the vaccination coverage have been explored, including extensive communication, education, free-of-charge vaccination, easy access to the vaccine and even mandatory vaccination.11–13 The latter has proven to be very effective and often leads to vaccination coverage rates of more than 90%.13 However, mandatory vaccination is not generally accepted as there are many ethical concerns. The duty not to harm or infect residents of LTCFs conflicts with the freedom to decide whether or not to have the vaccine. As long as this debate remains ongoing, well-prepared campaigns that include multiple interventions are the best available strategy to increase vaccination coverage.11 The World Health Organization (WHO) Regional office for Europe recommends an evidence-based approach to tailor seasonal influenza immunization programs to a specific setting.14 In this context, we developed a ready-to-use instruction manual to facilitate the implementation of interventions that are known to increase vaccination coverage and that target barriers toward vaccinations in healthcare institutions.15 We evaluated the usefulness of this manual and its impact on vaccination uptake, attitudes toward influenza vaccination and reasons for vaccine acceptance in 11 long-term care facilities (LTCFs) during the vaccination campaign preceding the 2017/2018 influenza season.

Methods

Development of the instruction manual for the organization of vaccination campaigns

The manual contains a stepwise approach with 24 possible interventions ranging from preparatory work to campaign evaluation (Table 1). Potential interventions were based on best practices in our previous study added with interventions from published studies and, campaign methodologies used in other countries and guidelines from health authorities.11–14,16-20 Studies were identified in Pubmed with the following keywords: “vaccine”, “vaccination”, “immunization”, “flu”, “influenza”, “healthcare workers”, “transmission”, “motivation” and “intervention”. Additional publications were found in references of those articles by the snowball effect. Subsequently, interventions to be included were chosen specifically to target determinants of vaccination uptake in Flemish LTCFs and to fit the Easy-Attractive-Social-Timely (EAST) model for behavioral change.15,21 The feasibility of implementing these interventions in Flemish healthcare institutions was discussed during round table sessions with flu campaign coordinators from LTCFs. Lastly, feedback from different stakeholders (health psychologist and campaign coordinators of LTCFs) was asked before finalizing the manual. The manual is available in Dutch on http://www.laatjevaccineren.be/hou-griep-uit-je-team.

Table 1.

Implemented interventions from the instruction manual in 11 participating LTCFs

| Category | Goal | Interventions | LTCF that used intervention in 2016 (n) | LTCF that used intervention in 2017 (n) | LTCFs that used intervention in 2016 and 2017 (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Campaign management | Counter organizational barriers | 1. Multidisciplinary organizational team consisting of at least three persons | 5 | 10 | 5 |

| 2. Evaluation of previous campaign with evaluation document attached in manual. | 0 | 4 | 0 | ||

| 3. Defining a campaign goal (e.g. 10% increase in vaccination coverage) | 5 | 7 | 5 | ||

| 4. Use of a step-wise action plan for the preparation of a vaccination campaign (attached in manual) | 0 | 5 | 0 | ||

| 5. Evaluation of campaign with evaluation document attached in manual | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||

| 6. Electronic registration of vaccination | 9 | 9 | 8 | ||

| 7. Providing feedback about campaign results to HCWs† | 1 | 10 | 1 | ||

| Education, communication and promotion |

Encourage vaccination, raise awareness about importance of vaccination for resident and own protection, increase knowledge about vaccination and combat myths and disbeliefs | 8. Vaccination campaign kickoff event (information session for staff at start of campaign, whether or not with vaccination moment involved) | 1 | 7 | 1 |

| 9. Personal incentives | 1 | 3 | 1 | ||

| 10. Group incentives (e.g. incentive for specific wards or whole LTCF‡ if predetermined goal is attained) | 6 | 6 | 5 | ||

| 11. Awarding wards or whole LTCFs with a certificate if a certain goal is reached | 0 | 7 | 0 | ||

| 12. Use of campaign image (vaccinated healthcare workers forming a protective circle around a vulnerable resident) | 0 | 10 | 0 | ||

| 13. Use of a personalized campaign with the own personnel as the main figures | 0 | 10 | 0 | ||

| 14. Communication messages with sufficient information (more than only vaccination data) | 6 | 9 | 6 | ||

| 15. Use of general communication channels (posters/flyers/screens) | 11 | 11 | 11 | ||

| 16. Use of personal communication channels (mail/letter) | 5 | 7 | 5 | ||

| 17. Education session for supervisors | 1 | 4 | 1 | ||

| 18. Education session for healthcare workers | 6 | 8 | 5 | ||

| 19. Use of educational material attached in manual (fact sheets and myth-busting sheets) | 0 | 8 | 0 | ||

| 20. Active involvement of supervisors or role models in the campaign (e.g. one to one vaccination encouragement by supervisor or visible vaccination of a supervisor) | 9 | 11 | 9 | ||

| Easy-access | Allow easy access vaccination and counter organizational barriers. | 21. Vaccination without prior enrollment | 3 | 5 | 3 |

| 22. Vaccination at easy-accessible and commonly used locations | 4 | 9 | 4 | ||

| 23. Multiple vaccination moments | 4 | 10 | 4 | ||

| 24. Peer vaccination | 7 | 10 | 7 |

†HCW: healthcare worker; ‡LTCF: long-term care facility.

Study population and design

All participating LTCFs of a previous study on determinants of vaccination were invited to participate in a follow-up study and 11 agreed.15 All long-term care facilities provide permanent residence and on site personal assistance with daily activities, nursing and other medical care, for persons above 65 years of age who can no longer live at home. The characteristics of the LTCFs and the institution-wide vaccination coverage data for the years 2014 to 2017 were obtained directly from the LTCFs. The implementation of vaccination promoting measures by the LTCF was assessed with a structured interview with the local campaign organizer before and after the intervention. One pre-intervention and one post-intervention interview were organized per participating LTCF. Pre-intervention interviews were scheduled in June 2017, before implementation of the manual, and post-intervention interviews in January 2018, after completion of the vaccination campaign. Attitudes toward vaccination and reasons for vaccine acceptance were attained with quantitative surveys in HCWs before and after the campaign. All HCWs from the participating LTCFs were asked to complete the pre-intervention survey between 31 August 2017 and 29 September 2017 and the post-intervention survey between 5 January 2018 and 2 February 2018. The surveys were anonymized using an allocation number and returned in sealed envelopes to ensure confidentiality of responses. Consent for use of the responses for scientific purposes was given on the first page of the survey, which also contained information about the design and aim of the study. Since the survey of adult healthcare workers was anonymous for the investigators, the interview with the institutional influenza campaign organizers only covered the practical organization of influenza campaigns (and no personal views on vaccination), and the intervention comprised regular practice, this study was exempt from a review by the ethical board of the university hospital.

Training and interviews with vaccination campaign coordinators

The structured pre-intervention interview in 2017 contained questions on the measures used during the vaccination campaign preceding the 2016/2017 influenza season. Afterwards, coordinators were trained on the use and content of the manual and the potential vaccination promoting actions listed in Table 1. During the structured post-intervention interview, we evaluated which interventions from the manual were actually implemented. In addition, the coordinators were asked to rate their satisfaction with the manual on 10-point Likert-scale and also to provide feedback on the usability. The pre-intervention interview took approximately 20 minutes while the evaluation interview lasted about 40 minutes since all interventions were assessed one by one.

Healthcare worker survey

The surveys were based on previously used questionnaires to ensure comparability.22–24 The pre-intervention survey consisted of three parts: (i) demographics; (ii) reasons for (non)vaccination (iii) attitudes toward influenza vaccination. Additionally, the post-intervention survey also contained questions on the visibility and utility of the vaccination campaign.

Statistical analysis

The pre- and post-intervention surveys were entered in an MS Access database. The distributions of characteristics pre- and post-intervention survey respondents were compared to the total sample and to census data using a chi-squared goodness of fit test. Census data concerned population data of adult healthcare workers employed in Flemish long-term care facilities of the same type (i.e elderly care) as those in our study. The change in vaccination uptake after the 2017-campaign compared to the three preceding years was tested with repeated measures ANOVA with Bonferroni correction for multiple testing. Linear regression was used to estimate the increase in vaccination coverage in relation to the number of newly implemented interventions. Attitudes regarding vaccination were recorded on a 5-point Likert scale which was dichotomized by combining (i) “strongly agree” and “agree” as a positive response and (ii) “do not agree/do not disagree”, “disagree” and “strongly disagree” as a negative response. Generalized linear mixed-effects models (mixed effects logistic regression) were used to determine the effect of the intervention on attitudes. The models included the subject nested within the relevant LTCF as a random factor and have the advantage over traditional pre-post intervention models like an(co)va that they use information from all participants, irrespective of whether they completed only one or both surveys. Since there was a substantial non-response to either survey, characteristics of the respondents of the first and second surveys were compared with the total sample using a chi-squared goodness of fit test. In addition, Pearson Chi-squared tests were used to compare the characteristics between the respondents of the first only, the second only or both surveys. A test probability of 5% was considered statistically significant. All data were analyzed with R. version 3.0.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2013).

Results

Characteristics of participating long-term care facilities and healthcare workers

The eleven participating LTCFs employed a median number of 120 HCWs (range: 40–170) and had a median number of 121 beds (range: 65–161). All LTCF participated in both surveys. Approximately 1250 HCWs received both surveys. In total 829 participants (response rate 66.1%) completed at least one of both surveys. The pre-intervention survey was completed by 645 HCWs (response rate: 51.4%), the post-intervention survey by 524 HCWs (response rate: 41.8%) and 340 HCWs completed both. Data from one pre-intervention participant were excluded from the analysis because the vaccination status was unclear which rendered most of the questionnaire unusable. Characteristics of survey respondents are listed in Table 2. No statistically significant difference was observed when respondents to the first and second surveys were compared to the total sample (Pearson Chi-squared goodness of fit test, all >0.05) (Table 2). When the characteristics were compared by response group (only the first, only the second or both surveys), females were more likely to answer both surveys (42.1% versus 36.7% in males, p = .02). All other characteristics did not significantly differ by response group (data not shown). A large majority were women and the median age was 44 years as well pre- and post-intervention. Participant characteristics were comparable to census data on LTCF staff, with the exception of a slightly larger proportion of participants >50 years of age (36% versus 25%; p < .001) and nurses (23% versus 19%;p < .01).25

Table 2.

Personal characteristics, occupation and vaccination status of survey participants

| All HCWs† (n = 828) |

Pre-intervention (N = 644) |

Post-intervention (N = 524) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | |

| Personal data ‡ | |||

| Female | 88.0 | 89.7 | 86.9 |

| Median age, years (range) § | - | 44 (18–65) | 44 (20–62) |

| Having chronic illness | 7.9 | 7.1 | 7.0 |

| Having children at home | 46.1 | 44.7 | 46.1 |

| Having elderly at home | 6.5 | 5.6 | 7.2 |

| Having chronically ill person at home | 6.4 | 5.6 | 6.9 |

| Occupation | |||

| Function | |||

| Nurse | 23.4 | 23.6 | 24.8 |

| Nursing Aides | 34.9 | 33.7 | 33.6 |

| Other HCWs with resident contact ¥ | 11.6 | 11.6 | 11.8 |

| Other HCWs without resident contact || | 27.5 | 28.6 | 28.2 |

| Other HCWs, unknown function | 2.5 | 2.5 | 1.5 |

| Daily contact with residents | 92.1 | 91.7 | 91.3 |

| Influenza vaccination status | % | % | |

| Vaccinated during the previous campaign (2016 or 2017, respectively) | - | 58.7 | 70.2 |

| Never been vaccinated | 14.6 | 18.5 ** | 13.9 |

| Annually vaccinated | 51.6 | 51.2 | 55.9 * |

†HCW: Healthcare worker

‡ For each item, between 1.2% and 1.7% of the respondents did not complete the particular question, except for item ‘having a chronically ill person at home’ and ‘having a child at home, it was 15.6% and 16.1%, respectively.

§ Median age for all HCWs group was not described as age changed between the two time points (pre- or post-intervention).

¥ Pharmacists, audiologists, physiotherapists, paramedics, psychologists, animation

||Medical technical staff, administrative, facilities and logistics

Chi2 goodness of fit test (pre or post intervention versus all respondents): *p < 0.05 **p < 0.01

Implementation and usability of the manual: results from structured interviews

The number of LTCFs that implemented a particular intervention from the manual in 2016 (before) and in 2017 (after the intervention) is shown in Table 1. The local campaign coordinators rated a median score of 8 (range 5–9.5) on a 10-point Likert-scale for satisfaction with the use of the manual. One LTCF preferred not to rate the manual as they had only implemented two new interventions. The LTCF that scored 5 had a pre-intervention vaccination coverage of 72% and considered the manual more useful for LTCFs with a low pre-intervention vaccine uptake. The other LTCFs were very positive about the use of the manual and stated that it was practical, encouraging and inspiring.

Vaccination uptake reported by the LTCF

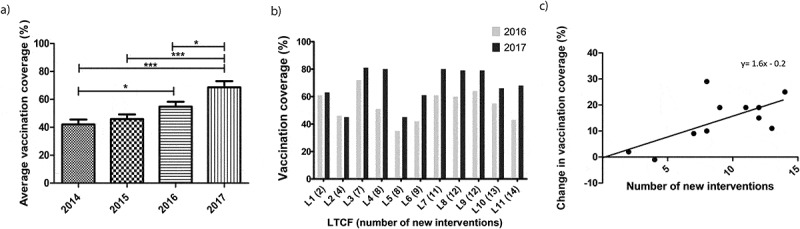

After implementation of the manual, the mean vaccination coverage reported by the 11 LTCFs significantly increased from 54% (range: 35–72%) in 2016 to 68% (range: 45–81%) in 2017 (p < .05, repeated measures ANOVA with Bonferroni correction). Conversely, no significant increase with the preceding year could be found in 2016 or 2015 (Figure 1A). A 10–30% increase is found in the 9 LTCFs that implemented 7 or more new interventions described in the manual (Figure 1B). In general, the vaccination coverage is estimated to increase 1.6% (95% confidence interval: 0.2–2.9; p < .05) per newly implemented intervention (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Influence of campaign organized with instruction manual on vaccination coverage. a) Mean vaccination coverage in participating LTCFs three years before and the year after the implementation of the manual. Change in coverage rates are determined with repeated measures ANOVA. One LTCF was excluded for this analysis due to missing data. This LTCF only opened in 2016. b) Vaccination coverage before and after implementation of the instruction manual. Participating LTCFs are ordered from L1 to L11 according to the number of implemented interventions. C) Change in vaccination coverage in relation to number of newly implemented interventions. Each data point represents one participating long-term care facility (LTCF). *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001

Vaccination uptake before and after implementation of the manual as reported by the HCW

The vaccination uptake reported by the survey respondents was 58.7% in 2016 and 70.2% in 2017. Of the 340 participants that completed both the pre- and post-intervention questionnaire, 140 were not vaccinated in 2016 but 52 (37.1%) of them were subsequently vaccinated in 2017. Among the in 2016 non-vaccinated HCWs, 64 (45.7%) had never been vaccinated against influenza and 18 (28.1%) of them received the vaccine for the first time in 2017.

Attitudes and beliefs regarding influenza vaccination before and after implementation of the instruction manual

Table 3 represents attitudes and beliefs in HCWs before and after the vaccination campaign. The first column shows the prevalence of agreement with a particular statement concerning vaccination before the campaign and the second column the prevalence after the campaign in all respondents who completed these surveys. The third column shows the odds ratio of agreeing with certain statement after the campaign compared to before the campaign as determined with the mixed model logistic regression. Positive changes in attitudes and beliefs were mostly observed in the domain of perceived barriers to influenza vaccination. HCWs were for example less likely to expect side effects after influenza vaccination (p = .03), to underestimate the danger of influenza (p = .001), or to oppose vaccination in general (p = .04). On the other hand, HCWs were less likely to consider themselves as a risk group for influenza (p = .01). Although the majority of HCWs (>90%) finds it important not to infect residents, they were less likely to agree with this after the campaign (p = .02). The statistical model used in Table 3 not only considers the pre- and post-intervention responses but also the correlated responses of respondents who completed both surveys, and those who belong to the same LCTF. The model may therefore indicate a change that goes in the opposite direction to what the prevalence data suggest. However, for the item “I oppose vaccination in general” the trend toward less agreement was confirmed when directly comparing responses in subjects who answered both surveys (data not shown). Also, the prevalence of those that agreed with the items ‘I am especially against vaccination in HCWs’ and ‘I think my employer only offers influenza vaccination to reduce costs’ is very low and does not differ much pre- and post-intervention. Therefore, the significance level of the odds ratios of these items should be interpreted with caution.

Table 3.

Attitudes and beliefs regarding influenza vaccination pre- and post-intervention (generalized linear mixed effect models)

| Survey respondents (N = 828) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-intervention | Post-intervention | OR† (95% CI) ‡ | |

| N: | 644 | 524 | |

| Attitude | (%) | (%) | |

| I find it important that: | |||

| • HCWs§ do not infect residents. | 91.6 | 90.2 | 0.2 (0.6–0.8)* |

| • All HCWs are vaccinated against influenza to ensure continuity of care. | 56.0 | 57.3 | 1.0 (0.7–1.4) |

| • HCWs have the freedom to decide whether or not to have the influenza vaccine. | 79.9 | 78.2 | 0.8 (0.4–1.7) |

| I consider influenza vaccination important as it is my duty not to harm residents | 54.8 | 55.8 | 1.1 (0.8–1.4) |

| I think influenza vaccination should be mandatory for HCWs | 20.6 | 22.4 | 1.8 (0.8–3.8) |

| Advantages of influenza vaccination | (%) | (%) | |

| Vaccination against influenza gives me confidence that: | |||

| • I will not get influenza | 58.4 | 50.4 | 1.1 (0.8–1.5) |

| • I will not infect residents | 57.3 | 59.8 | 1.2 (0.9–1.6) |

| • I will not infect my family | 58.1 | 59.6 | 1.1 (0.8–1.5) |

| I find it important that all HCWs are vaccinated in order to avoid increased workload | 52.5 | 57.5 | 1.3 (1.0–1.8)° |

| Perceived barriers against vaccination | (%) | (%) | |

| I think influenza is not dangerous to me | 21.2 | 15.0 | 0.2 (0.1–0.5)*** |

| Vaccination weakens my immune system | 25.3 | 23.3 | 0.7 (0.4–1.4) |

| I can get the flu from the vaccine | 29.8 | 25.7 | 0.8 (0.6–1.1) |

| I oppose vaccination in general | 10.8 | 11.3 | 0.3 (0.1–0.9)* |

| I am especially against vaccination in HCWs | 3.9 | 3.4 | 0.4 (0.1–2.0) |

| I think my employer only offers influenza vaccination to reduce costs | 6.1 | 5.3 | 1.8 (0.5–6.0) ¥ |

| If I take up influenza vaccination once, I have to do this every year | 26.0 | 19.1 | 0.2 (0.1–0.3)*** |

| I would expect to have side effects if I got vaccinated against influenza | 21.2 | 16.7 | 0.4 (0.2–0.9)* |

| I think HCW vaccination is of little use as residents frequently have visitors. | 17.0 | 14.0 | 0.3 (0.1–0.7)** |

| I think that LTCFs only implement influenza vaccination to prevent HWCs from being sick. | 28.2 | 20.9 | 0.6 (0.5–0.9)** |

| Perceived susceptibility to influenza | (%) | (%) | |

| I think I have a high chance of getting influenza | 37.2 | 37.2 | 1.0 (0.7 − 1.3) |

| I think influenza is very dangerous for my residents | 88.6 | 88.3 | 0.7 (0.4–2.0) |

| I think I have a high chance to infect residents | 73.0 | 74.4 | 1.0 (0.5–2.0) |

| I think HCWS have an increased risk of getting ill during an influenza epidemic | 79.0 | 73.1 | 0.4 (0.2–0.8)* |

| I think that when I am vaccinated against the flu, I have less chance to acquire influenza compared to vaccinated residents | 45.7 | 46.2 | 1.0 (0.8–1.3) |

† Odds Ratio (OR) from a generalized linear mixed effects model with subject ID nested within LTCF as a random factor, except for ¥ because the model with nested effects did not converge: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, °p < 0,1 (trend)

‡CI: confidence interval; §HCW: Healthcare worker.

For each item, between 1.7% and 5.4% of the pre-intervention respondents and between 2.7 and 5.3 of the post-intervention respondents did not complete the particular question.

Reasons for vaccination uptake after previous refusal or missing vaccination

The main motivators for vaccination uptake in 2017 in HCWs who were not vaccinated in 2016 were the protection of residents (69.2%), family members (59.6%) or themselves (53.8%). The main reasons for non-vaccination in the preceding year were concerns about efficacy (26.9%) usefulness (13.5%) and necessity of influenza vaccination (23.1%), forgot to get the vaccine (17.3%) or fear of side effects (13.5%).

Similarly, the main reasons for vaccination in those who received their first vaccine in 2017 were the protection of residents (72.2%), family members (50%) and themselves (38.9%) as well as recommendation by a supervisor (44.4%). The main reasons for the previous refusal were doubts about efficacy (33.3%) and the necessity of the vaccine (16.7%), never having had influenza (27.8%) and being afraid of needles (16.7%).

Perception of the campaign by the survey respondents

Of the HCW respondents, 68.8% found the campaign informative and most HCWs indicated to be well informed during the campaign about the risks of influenza (67.2%), transmitting influenza to residents (70.4%) and the safety and efficacy of the vaccine (63.3%). Moreover, half of the respondents (51.1%) stated that the campaign had made them think about the usefulness of influenza vaccination and 17.7% stated that the campaign had influenced their decision whether or not to get vaccinated.

Discussion

Higher vaccination uptake rates and decreased perceived barriers toward influenza vaccination were observed in LTCFS that used an instruction manual, which was aimed at facilitating the implementation of interventions to increase vaccination coverage. The vaccination uptake was significantly higher in 2017 compared to 2016 and the two preceding years, while in contrast no significant annual increase was observed between 2014 and 2015 and between 2015 and 2016. This assures us that the findings are not due to an ongoing trend of increasing coverage, but can be attributed to the use of the manual. Particularly, the coverage increased with 10–30% in LTCFs that implemented at least seven out of 24 possible interventions. Three LTCFs reached or exceeded the target of 80% set by the Flemish government and two approached it with a vaccination coverage of 79%. In line with the literature, we found that the degree of increase in vaccination uptake was proportional to the number of implemented measures.11,26 Reviews on intervention programs showed that a combination of education, promotion and improved access is more effective than single intervention programs.11–13 Therefore, we strongly focused on education, role models, personalized communication, easy access and resident- and self-protection. The added value of the manual is not only suggested by the increased coverage but even more so by the finding that nearly 40% of those not vaccinated in 2016 and nearly 30% of those who were never vaccinated before received the vaccine in 2017.

Furthermore, after implementing the manual, we observed a significant decrease in perceived barriers toward vaccination. HCWs were less likely to expect side effects, to oppose vaccination, to believe that influenza vaccination is used to decrease sick leave or to believe that vaccination is useless due to the many visitors the residents have. Strangely, we also found that HCWs were less likely to give importance to not infecting residents. However, a large majority (>90%) still agreed with this statement. Llupía et al.27 found that HCWs perceived influenza as a more severe disease after a multi-intervention campaign. Similarly, we found that HCWs were more likely to think that influenza might be dangerous. Contrariwise, they were less likely to believe they have a higher risk of falling ill from influenza. It is possible that HCWs realize that influenza can be dangerous but that they gained trust in the vaccine efficacy and hence do not expect to become infected. Trust might be gained through the educational part of the campaign. This is supported by the fact that most LTCFs implemented the educational material from the manual and that HCWs indicated to be well informed about the risk of influenza and the safety and efficacy of the vaccine. Additionally, we found that previously not vaccinated HCWs who were skeptic toward the vaccine, can change their mind toward vaccination. Interestingly, in those HCWs, resident protection was the mind-changing driver. This seems logical as 70% of HCWs indicated to be well informed about the risk of transmission to residents during influenza epidemics, but it is also surprising given that self-protection has consistently been reported as the most important driver for vaccine acceptance in HCWs.11 Given this, we believe that focusing on the combination of HCW and resident vaccination is the best available means of protecting residents.

A strength of the manual is that the interventions were specifically tailored to healthcare institutions. This is important as peer opinions, cultural and institutional factors influence knowledge and behavior in specific settings.11 Also, the organizers of the campaigns found the manual practical in use. This assures us that other LTCFs will equally be able to use it in a convenient way. The study also had a large number of study respondents, which reassures us that the data are robust. Moreover, the LTCF which did only use a limited number of interventions did not see an increase in vaccination coverage.

Nevertheless, there were also some limitations involved in this study. Firstly, we did not have a control group of LTCFs with similar pre-intervention vaccination uptake rates. We can therefore not rule out the possible effect of outside factors such as exposure to information in the media. However, both 2016–2017 and 2017–2018 were moderate influenza seasons with limited media attention. Another limitation is that there was heterogeneity between the campaigns. Since there were 24 possible interventions and only 11 participating LTCFs, the study was not sufficiently powered to analyze the impact of the individual interventions. Yet we believe that combining multiple interventions is effective to improve vaccination uptake.11–13 Thirdly, the response rate was limited and a large number of participants completed only one survey. Nevertheless, the response rate of 51.4% for the pre-intervention survey and 41.8% for the post-intervention survey is higher than the 29% observed in LTCF in a previous study and in line with what is seen in other studies.15,22-24 We also believe that the data are robust as the majority of characteristics of those who completed both surveys were not statistically different from those who completed only the first or second survey. Furthermore, the manual was only evaluated during one campaign. Therefore, we cannot ascertain that the findings are sustainable. However, previous influenza vaccination has shown to be a good predictor of future vaccination uptake.11 Additionally, evidence exists that maintained efforts go along with high and sustained vaccination rates.11 For example, a recent study on a multi-intervention program found an increase from 70% to 90% in two years time and a sustained coverage of 90% in the subsequent year.28 Although we did not assess long-term effects, flu coordinators showed the intention to continue using the manual to organize their campaigns because they observed a significant increase in vaccination coverage. Finally, there were small differences between the demographic profile of the survey participants and census data. This is not likely to have a large impact on the generalizability of our results because the census data relate to full-time equivalent HCWs whereas we counted all healthcare workers irrespective of working time.

In summary, we conclude that the intervention manual supports vaccination uptake and decreases perceived barriers toward influenza vaccination. This is especially true when LTCFs are motivated and willing to invest time and financial resources. These results should encourage competent authorities to create a similar ready-to-use manual to facilitate the implementation of interventions that are known to increase vaccination coverage in healthcare institutions. Even if vaccination is mandatory, this manual might still be useful to increase awareness and acceptance by the HCW, who may otherwise take exception to such a top-down policy.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all participating long-term care facilities and their healthcare workers for their contribution to this study.

Funding Statement

The development of the manual was supported by the Flemish Agency for Health and Care [AP/IZ-VAC/2016/3/20.07.2016].

Declaration of interest

CV was the principal investigator for influenza vaccine clinical trials from AdImmune and principal investigator for other vaccine clinical trials from GSK, Pfizer, MSD for which the university received grants. CV received no personal grants. LB and MR have nothing to disclose. The development of the manual was supported by the Flemish Agency for Care and Health (Grant: AP/IZ-VAC/2016/3/20.07.2016).

References

- 1.Fulop T, Pawelec G, Castle S, Loeb M.. Immunosenescence and vaccination in nursing home residents. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:443–48. doi: 10.1086/596475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haq K, McElhaney JE. Immunosenescence: influenza vaccination and the elderly. Curr Opin Immunol. 2014;29:38–42. doi: 10.1016/J.COI.2014.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iuliano AD, Roguski KM, Chang HH, Muscatello DJ, Palekar R, Tempia S, Cohen C, Gran JM, Schanzer D, Cowling BJ, et al. Estimates of global seasonal influenza-associated respiratory mortality: a modelling study. Lancet (London, England). 2017;1–16. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33293-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salgado CD, Farr BM, Hall KK, Hayden FG. Influenza in the acute hospital setting. Lancet Infect Dis. 2002;2:145–55. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(02)00221-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Potter J, Stott DJ, Roberts MA, Elder AG, O’Donnell B, Knight PV, Carman WF. Influenza vaccination of health care workers in long-term-care hospitals reduces the mortality of elderly patients. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:1–6. doi: 10.1093/infdis/175.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carman WF, Elder AG, Wallace LA, McAulay K, Walker A, Murray GD, Stott DJ. Effects of influenza vaccination of health-care workers on mortality of elderly people in long-term care: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2000;355:93–97. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)05190-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayward AC, Harling R, Wetten S, Johnson AM, Munro S, Smedley J, Murad S, Watson JM. Effectiveness of an influenza vaccine programme for care home staff to prevent death, morbidity, and health service use among residents: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2006;333:1241. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39010.581354.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lemaitre M, Meret T, Rothan-Tondeur M, Belmin J, Lejonc JL, Luquel L, Piette F, Salom M, Verny M, Vetel JM, et al. Effect of influenza vaccination of nursing home staff on mortality of residents: a cluster-randomized trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:1580–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.To KW, Lai A, Lee KCK, Koh D, Lee SS. Increasing the coverage of influenza vaccination in healthcare workers: review of challenges and solutions. J Hosp Infect. 2016;94:133–42. doi: 10.1016/J.JHIN.2016.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.ELu P, M-C H, AC O, Ding H, Srivastav A, WW W, JA S. Seasonal influenza vaccination coverage trends among adult populations, U.S., 2010–2016. Am J Prev Med. 2019;57:458–69. https://doi.10.1016/j.amepre.2019.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hollmeyer H, Hayden F, Mounts A, Buchholz U. Review: interventions to increase influenza vaccination among healthcare workers in hospitals. Influenza Other Respi Viruses. 2013;7:604–21. doi: 10.1111/irv.12002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lam PP, Chambers LW, MacDougall DM, McCarthy AE. Seasonal influenza vaccination campaigns for health care personnel: systematic review. Cmaj. 2010;182:E542–8. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.091304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lytras T, Kopsachilis F, Mouratidou E, Papamichail D, Bonovas S. Interventions to increase seasonal influenza vaccine coverage in healthcare workers: A systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12:671–81. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2015.1106656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.WHO Europe . Tailoring Immunization Programmes for Seasonal Influenza (TIP FLU) A guide for increasing health care workers’ uptake of seasonal influenza vaccination. Copenhagen (Denmark): WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2015. [Accessed 2019 March27]. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/290851/TIPGUIDEFINAL.pdf?ua=1. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boey L, Bral C, Roelants M, De Schryver A, Godderis L, Hoppenbrouwers K, Vandermeulen C. Attitudes, believes, determinants and organizational barriers behind the low seasonal influenza vaccination uptake in healthcare workers – A cross-sectional survey. Vaccine. 2018;36:3351–58. doi: 10.1016/J.VACCINE.2018.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Health Service UK . Flu fighter campaign. Leeds (United Kingdom): NHS Employers. Accessed; 2019. March 27. https://www.nhsemployers.org/campaigns/flu-fighter/nhs-flu-fighter [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for disease control and prevention (CDC) . Barriers and strategies to improving influenza vaccination among health care personnel | seasonal influenza (Flu) | CDC. Atlanta (GA./United States): Centers for disease control and prevention, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases (NCIRD); 2016. [[accessed 2019 March27]September7]. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/toolkit/long-term-care/strategies.htm [Google Scholar]

- 18.Institute of Preventive Medicine Environmental and Occupational Health Prolepsis . HProImmune: promotion of immunization for health professionals in Europe. Athens (Greece): Institute of Preventive Medicine Environmental and Occupational Health Prolepsis; 2013. [accessed 2019 March27]. http://hproimmune.eu/index.php/hproimmune/target [Google Scholar]

- 19.Massachusetts Medical Society . Employee flu immunization campaign kit. Maltham (MA./United States): Massachusetts Medical Society; 2006. [Accessed 2016 December19]. http://www.massmed.org/Patient-Care/Health-Topics/Colds-and-Flu/Employee-Flu-Immunization-Campaign-Kit/#.XJtA2FVKjIU. [Google Scholar]

- 20.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) . Influenza communication guide: how to increase influenza vaccination uptake and promote preventive measures to limit its spread. Stockholm (Sweden): ECDC; 2009. [Accessed 2019 March27]. https://ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/communication-guidelines-influenza-vaccination. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Service O, Hallsworth M, Halpern D, Algate F, Gallagher R, Nguyen S, Ruda S, Marcos Pelenur M, Gyani A, Harper H, et al. EAST Four simple ways to apply behavioral insights. London (United Kingdom): The behavioural insights team; 2014. https://www.bi.team/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/BIT-Publication-EAST_FA_WEB.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ofstead CL, Amelang MR, Wetzler HP, Tan L. Moving the needle on nursing staff influenza vaccination in long-term care: results of an evidence-based intervention. Vaccine. 2017;35:2390–95. doi: 10.1016/J.VACCINE.2017.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hopman CE, Riphagen-Dalhuisen J, den Akker I, Frijstein G, der Geest-blankert AD, Danhof-Pont MB, De Jager HJ, Bos AA, Smeets E, De Vries MJ, et al. Determination of factors required to increase uptake of influenza vaccination among hospital-based healthcare workers. J Hosp Infect. 2011;77:327–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2010.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Looijmans-van den Akker I, JJM VD, TJM V, GA VE, MAB VDS, ME H, Hak E. Which determinants should be targeted to increase influenza vaccination uptake among health care workers in nursing homes? Vaccine. 2009;27:4724–30. doi: 10.1016/J.VACCINE.2009.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.FeBi vzw . (Federale & Brusselse Maribel- en Vormingsfondsen binnen de private non-profit sector). Sectorfiche van PC 330 Gezondheidsinrichtingen- en diensten – Subsector 330.01.20 - Ouderenzorg. Brussels (Belgium): FeBi vzw;2014 [accessed 2019. August 2]. http://www.fe-bi.org/sectorfoto.

- 26.Yue X, Black C, Ball S, Donahue S, de Perio MA, Laney AS, Greby S. Workplace interventions and vaccination-related attitudes associated with influenza vaccination coverage among healthcare personnel working in long-term care facilities, 2015‒2016 influenza season. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019;20(6):718–24. doi: 10.1016/J.JAMDA.2018.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Llupià A, Mena G, Olivé V, Quesada S, Aldea M, Sequera VG, Ríos J, García-Basteiro AL, Varela P, Bayas JM, et al. Evaluating influenza vaccination campaigns beyond coverage: A before-after study among health care workers. Am J Infect Control. 2013;41(8):674–78. doi: 10.1016/J.AJIC.2013.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frisina PG, Ingraffia ST, Brown TR, Munene EN, Pletcher JR, Kolligian J. Increasing influenza immunization rates among healthcare providers in an ambulatory-based, University healthcare setting. Int J Qual Heal Care. 2019. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzy247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]