Abstract

A 43-year-old woman presented with postpartum haemorrhage necessitating uterine artery embolisation. Prior to embolisation, angiography demonstrated the presence of a persistent sciatic artery (PSA). Due to the possibility of embolic particles inadvertently traveling to the lower extremity via this variant arterial pathway, care was taken to only embolise the uterine artery. PSAs are uncommon but important vascular pathways to screen for during pelvic intervention and are associated with other genitourinary anomalies.

Keywords: radiology, interventional radiology, obstetrics and gynaecology

Background

Persistent sciatic arteries (PSAs) are a rare group of anatomical variants with an estimated incidence of 0.03%–0.06%.1 The sciatic artery originates from the umbilical artery in embryogenesis and supplies the lower limb until the superficial femoral artery develops. PSAs occur when the sciatic artery fails to disappear, often due to incomplete formation of the femoral artery. The following demonstrates a case of a female patient with an incidentally found PSA in the setting of postpartum haemorrhage.

Case presentation

A 43-year-old gravida 6 para 1 woman at 34.5 weeks gestation presented with preterm premature rupture of membranes complicated by breech presentation, necessitating emergent Caesarean section. She had a history of one prior ectopic pregnancy managed with laparoscopic resection and four early pregnancy losses each less than 10 weeks gestation. Her prior prenatal care was performed in her country of residence, which was separate from the country of this clinical episode. Intraoperatively, her anatomy was notable for uterine didelphys with pregnancy in the left uterine horn.

Two hours after delivery, she was found to have excessive vaginal bleeding and fundal bogginess, consistent with uterine atony. Despite administration of uterotonics and placement of a Bakri balloon, her total estimated blood loss was 3.5 L and her haemoglobin decreased from 120 g/L to 60 g/L. At that time, her blood pressure was 80/40 mm Hg. Aggressive resuscitation included bolused intravenous saline, six units packed red blood cells, one unit fresh frozen plasma, two units fibrinogen concentrate and one unit cryoprecipitate; a phenylephrine drip was also initiated. She was then transferred to interventional radiology for further management.

Treatment

An initial pelvic arteriogram revealed relatively small calibre uterine arteries bilaterally, suggestive of vasoconstriction. Selective angiography of the left internal iliac artery was performed to delineate the anatomy and assess for a source of haemorrhage. A pseudoaneurysm arising from the left uterine artery with brisk active extravasation was identified (figure 1). Additionally, a note was made of a continuation of the left internal iliac artery into the left lower extremity by way of a PSA. Considerations for therapy at this time included gelfoam embolisation of the anterior division of the left internal iliac artery, gelfoam or particle embolisation of the left uterine artery, or glue or coil embolisation of the left uterine artery pseudoaneurysm. Oftentimes in postpartum haemorrhage, a temporary embolic such as gelfoam is the preferred treatment, as this carries a theoretical benefit of increased likelihood of preservation of fertility. However, given the robust degree of active extravasation, a definitive treatment was preferred. Therefore, the left uterine artery pseudoaneurysm was successfully coil embolised to haemostasis (figures 2 and 3).

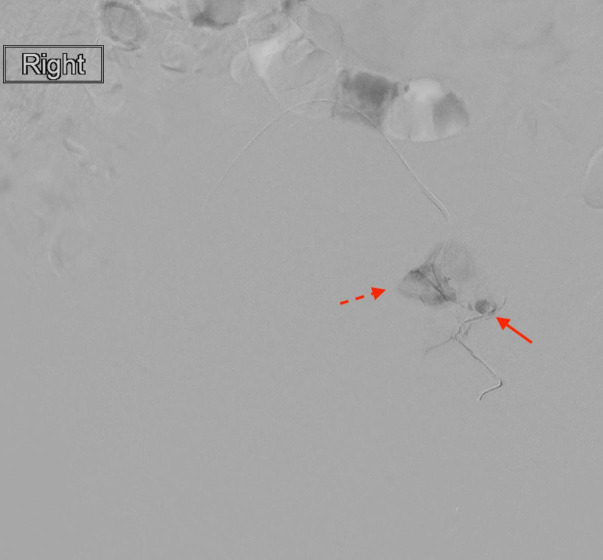

Figure 1.

Digital subtraction angiogram of the left uterine artery pseudoaneurysm (solid arrow) with blush of active extravasation (dotted arrow).

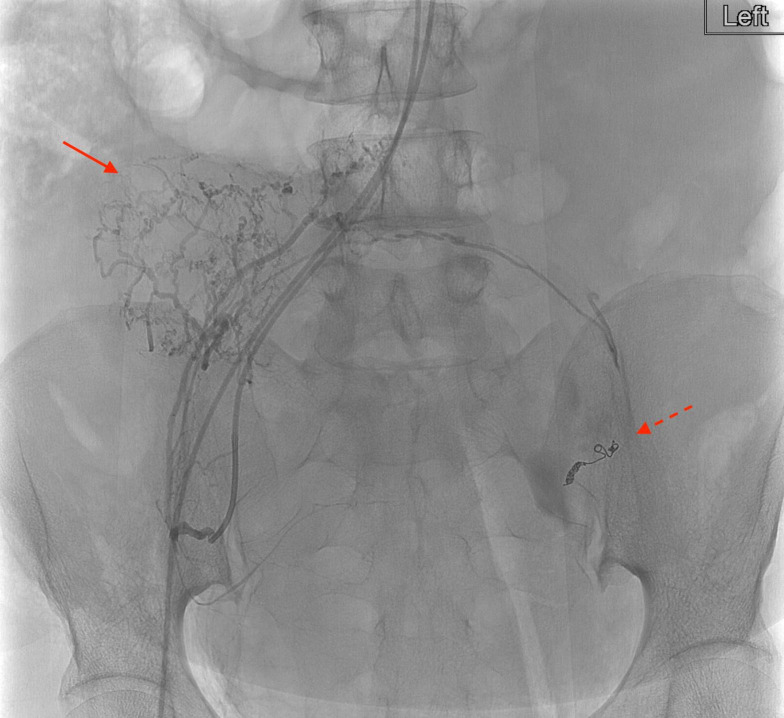

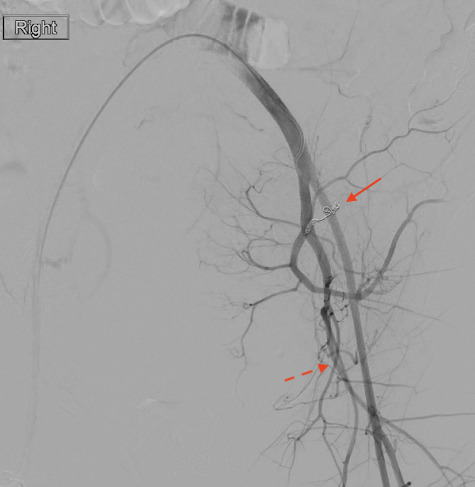

Figure 2.

Digital subtraction angiogram with catheter tip in the left common iliac artery demonstrating the coiled left uterine artery (solid arrow) and patent persistent sciatic artery (dotted arrow).

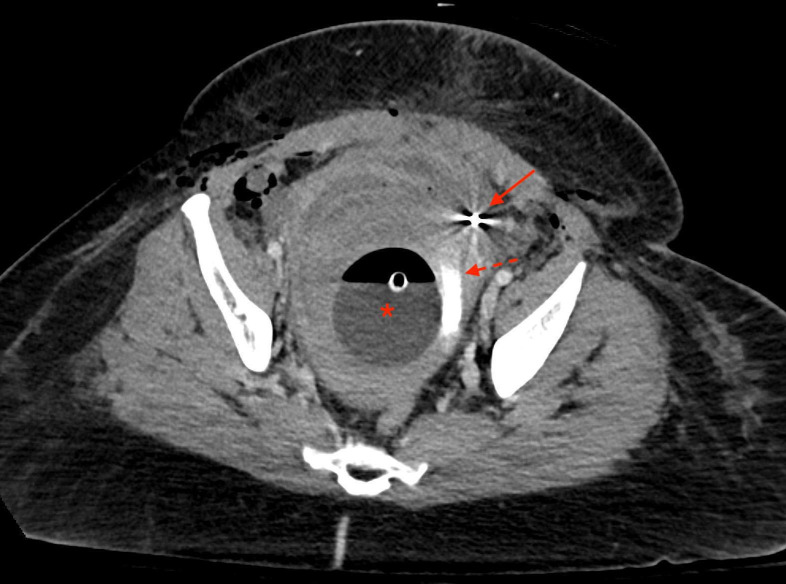

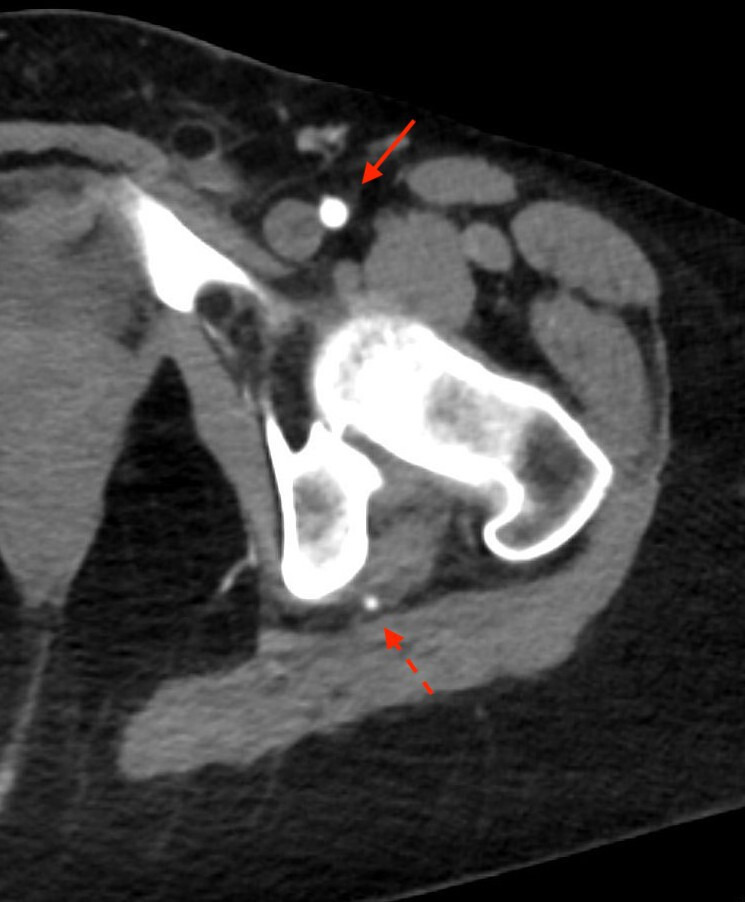

Figure 3.

Venous phase CT through the level of the pelvis performed immediately post partum and after embolisation. Bakri balloon is still in place (asterisk). Contrast staining can be seen within the uterine cavity (dotted arrow) consistent with recent extravasation. Left uterine artery embolic coils are also visualised (solid arrow).

There was a concern that the patient’s superimposed uterine atony may lead to persistent postpartum haemorrhage, despite the successful treatment of the pseudoaneurysm. Therefore, an additional gelfoam embolisation of the anterior division of the left internal iliac artery was a consideration. This would likely decrease the risk of recalcitrant haemorrhage supplied by collateralised arterial flow to the uterus. However, this was weighed against the risk of embolic material propagating into the left lower extremity by way of the PSA. The decision was made not to perform further embolisation of the left sided arteries. Attention was then turned to the right uterine artery, which demonstrated a normal branching pattern (figure 4). The right uterine artery was successfully embolised to stasis with gelfoam. At the conclusion of the procedure, there was significant improvement in the patient’s haemodynamic status, with relative normalisation of her blood pressure to 110/50 mm Hg off of all vasopressors.

Figure 4.

Selective arteriogram of the right uterine artery branch vessels prior to gel foam embolisation (solid arrow). Left uterine artery pseudoaneurysm coils are in place (dotted arrow).

Outcome and follow-up

In the immediate postoperative period, the patient remained haemodynamically stable without requiring vasopressors, and her haemoglobin stabilised to 90 g/L without additional blood products. No immediate complications occurred and she was discharged on postoperative day 3.

She returned for clinical and imaging follow-up 2 weeks after discharge which revealed a reduction in volume of intrauterine blood products and no residual filling of the left uterine artery pseudoaneurysm (figure 5A, B). She endorsed intermittent passage of vaginal clots but denied overt haemorrhage. Her lower extremities were well perfused and she denied signs or symptoms of ischaemia including numbness, pain or tissue loss. Again seen were the uterine didelphys and left sided PSA (figure 6). Also noted were aplasia of the right kidney, aplasia of the right adrenal gland and duplication of the inferior vena cava (figure 7).

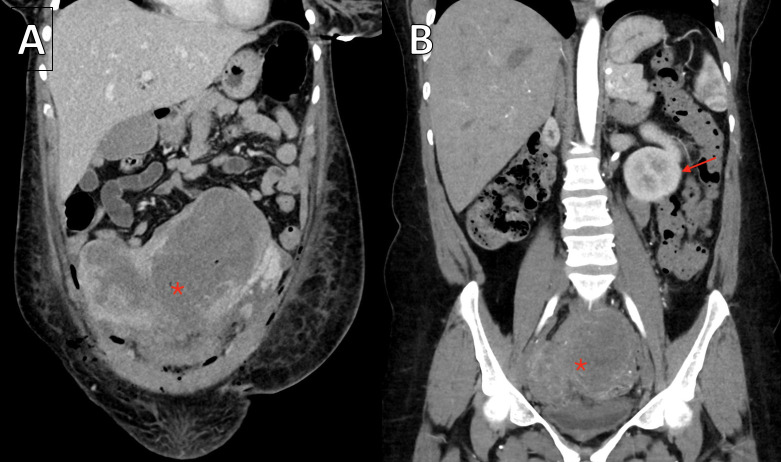

Figure 5.

(A) Venous phase coronal CT performed in the immediate postpartum phase demonstrates a didelphys uterus markedly distended with blood products (asterisk). (B) Arterial phase coronal CT performed 2 weeks after discharge demonstrates the didelphys uterus significantly reduced in size (asterisk). Partially visualised single left kidney (arrow).

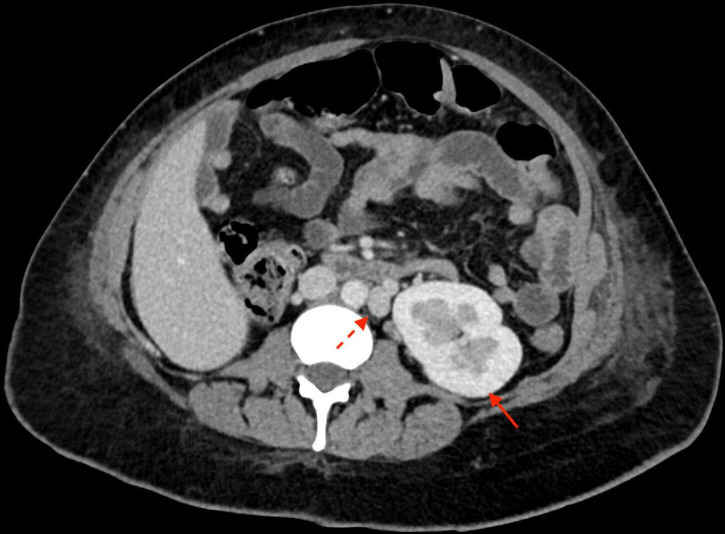

Figure 6.

Arterial phase CT demonstrates the left persistent sciatic artery (dotted arrow) in addition to the normal left common femoral artery (solid arrow).

Figure 7.

Venous phase CT through the level of the mid abdomen demonstrates a single left kidney (solid arrow) as well as a duplicated inferior vena cava (dotted arrow).

Discussion

Although many PSAs are asymptomatic, patients are typically considered at risk for stenosis or aneurysm formation at the site of direct compression between the piriformis muscle and adjacent structures such as the sacrospinous ligament or greater trochanter.2 This case illustrates a unique additional consideration for patients with PSAs in the setting of pelvic haemorrhage, which is occasionally treated with unilateral or bilateral internal iliac artery branch embolisation. Indiscriminate use of particle embolisation of the internal iliac artery in a patient with a PSA can conceivably result in inadvertent embolisation of the distal extremity in certain circumstances.

Five types of PSAs have been described in the Pillet-Gauffre classification, and they can be broadly grouped into complete or incomplete subtypes.3 The complete type of PSA accounts for approximately 80% of PSAs and is characterised by its direct communication with the popliteal artery, thus perfusing the distal lower extremity in the absence or hypoplasia of the ipsilateral superficial femoral artery.4 An incomplete PSA, which is seen as the type III variant in this case, does not directly communicate with the popliteal artery. Theoretically, incomplete subtypes of PSAs may have a lower risk of limb ischaemia and can tolerate some degree of inadvertent embolisation due to their distal termination in deep muscular branches, which are highly collateralised. To our knowledge, there has not been a proven association between incomplete PSA subtypes and lower rates of distal limb ischaemia. Nevertheless, prudent use of embolic material was a priority, and embolisation of the left internal iliac artery ipsilateral to the patient’s PSA was not performed in this case.

PSAs have been linked to genitourinary and Mullerian duct abnormalities.5 6 Embryologically, both the sciatic and primary renal arteries are branches of the common iliac artery, which may explain the association.5 Aside from this patient’s didelphys uterus (right sided rudimentary horn), she had concomitant aplasia of the right kidney, adrenal gland and a duplicated inferior vena cava discovered on a follow-up CT (figure 7).

Patient’s perspective.

Paraphrased from patient: I have been told before that my uterus was unique, but did not know that there were so many other variations elsewhere in my body too. I found it very interesting to look at the scans of my body with a radiologist explaining all of the unique features. I am glad that the physicians involved in my care were prioritising my safety, and I hope that this report will help inform other providers who may take care of similar patients in the future.

Learning points.

Pelvic arteriograms are critical to accurately delineate common and variant vascular anatomy prior to intervention in the setting of pelvic haemorrhage.

Persistent sciatic arteries must be identified and approached with caution—inadvertent embolisation during internal iliac artery embolisation can result in limb ischaemia.

Müllerian duct anomalies are often associated with renal anomalies, but may also predispose to variant vascular anatomy.

Footnotes

Twitter: @ScottPerkinsMD, @elena_drews

Contributors: SSP, ED and GL contributed to conceptualisation and design of the study, drafting the manuscript and approval of the final manuscript. JM participated in clinical and interventional management of the patient and approval of the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.van Hooft IM, Zeebregts CJ, van Sterkenburg SMM, et al. The persistent sciatic artery. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2009;37:585–91. 10.1016/j.ejvs.2009.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shaffer W, Maher M, Maristany M, et al. Persistent sciatic artery: a favorable anatomic variant in a setting of trauma. Ochsner J 2017;17:189–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gauffre S, Lasjaunias P, Zerah M. Sciatic artery: a case, review of literature and attempt of systemization. Surg Radiol Anat 1994;16:105–9. 10.1007/BF01627932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morisaki K, Yamaoka T, Iwasa K, et al. Persistent sciatic artery aneurysm with limb ischemia: a report of two cases. Ann Vasc Dis 2017;10:44–7. 10.3400/avd.cr.16-00119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang C-Y, Hsu H-L, Shen S-H, et al. Persistent sciatic artery associated with solitary kidney and maldevelopment of mesonephric duct and urogenital sinus. Vasc Med 2016;21:471–2. 10.1177/1358863X15624531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shortell CK, Illig KA, Ouriel K, et al. Fetal internal iliac artery: case report and embryologic review. J Vasc Surg 1998;28:1112–4. 10.1016/S0741-5214(98)70039-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]