Abstract

Objective

Scientific authorship is a vital marker of achievement in academic careers and gender equity is a key performance metric in research. However, there is little understanding of gender equity in publications in biomedical research centres funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). This study assesses the gender parity in scientific authorship of biomedical research.

Design

Descriptive, cross-sectional, retrospective bibliometric study.

Setting

NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre (BRC).

Data

Data comprised 2409 publications that were either accepted or published between April 2012 and March 2017. The publications were classified as basic science studies, clinical studies (both trial and non-trial studies) and other studies (comments, editorials, systematic reviews, reviews, opinions, book chapters, meeting reports, guidelines and protocols).

Main outcome measures

Gender of authors, defined as a binary variable comprising either male or female categories, in six authorship categories: first author, joint first authors, first corresponding author, joint corresponding authors, last author and joint last authors.

Results

Publications comprised 39% clinical research (n=939), 27% basic research (n=643) and 34% other types of research (n=827). The proportion of female authors as first author (41%), first corresponding authors (34%) and last author (23%) was statistically significantly lower than male authors in these authorship categories (p<0.001). Of total joint first authors (n=458), joint corresponding authors (n=169) and joint last authors (n=229), female only authors comprised statistically significant (p<0.001) smaller proportions, that is, 15% (n=69), 29% (n=49) and 10% (n=23) respectively, compared with male only authors in these joint authorship categories. There was a statistically significant association between gender of the last author with gender of the first author (p<0.001), first corresponding author (p<0.001) and joint last author (p<0.001). The mean journal impact factor (JIF) was statistically significantly higher when the first corresponding author was male compared with female (Mean JIF: 10.00 vs 8.77, p=0.020); however, the JIF was not statistically different when there were male and female authors as first authors and last authors.

Conclusions

Although the proportion of female authors is significantly lower than the proportion of male authors in all six categories of authorship analysed, the proportions of male and female last authors are comparable to their respective proportions as principal investigators in the BRC. These findings suggest positive trends and the NIHR Oxford BRC doing very well in gender parity in the senior (last) authorship category. Male corresponding authors are more likely to publish articles in prestigious journals with high impact factor while both male and female authors at first and last authorship positions publish articles in equally prestigious journals.

Keywords: natural science disciplines, education & training (see medical education & training), change management, health policy, organisational development, statistics & research methods

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to investigate gender parity in six categories of scientific authorship: first authors, first corresponding authors, last authors and three joint authorship categories, that is, joint first authors, joint corresponding authors and joint last authors in biomedical research.

The proportions of male and female last (senior) authors are comparable to their respective proportions as principal investigators in the NIHR Oxford BRC, suggesting strong evidence of attainment of gender parity in this category of scientific authorship in the BRC.

This study offers an important benchmark on gender equity in scientific authorship for other NIHR funded BRCs and organisations in England.

This study provides evidence that male first corresponding authors are more likely to publish articles in prestigious journals with high impact factors compared to female first corresponding authors, whilst both male and female authors at first and last authorship positions publish articles in prestigious journals with almost equal impact factors.

The generalisability of these findings may be limited due to differences in medical specialities, research areas, institutional cultures and levels of support to individual researchers.

Introduction

Promoting responsible research and innovation (RRI) is a major strategy of the ‘Science with and for Society’ work programme of the European Union’s (EU) Horizon 2020 Framework Programme for Research and Innovation (R&I).1 RRI aims to build capacity and develop innovative ways to connect science and society.2 The RRI approach enables all societal members (such as researchers, citizens, policymakers, businesses and third sector organisations) to work together during the R&I process in order to better align R&I with the values, needs and expectations of the society.1 2 The RRI framework includes public engagement, open access, gender equity, ethics and science education as the main ‘keys’ for governance, and two further ‘keys’: sustainability and social justice/inclusion for general policy.3 The idea is that by prioritising these key components of RRI, it would help make science more attractive to young people and society, and raise awareness of the meaning of responsible science.2

We have focused on the ‘gender equity’ element of the RRI because it is imperative to advance gender equality within research institutions, as well as within the design and content of R&I.1 The issue of enhancing female participation in economic decision-making has become prominent in the national, European and international spheres, with a particular focus on the economic dimension of gender diversity.4 In order to achieve a fair female participation within positions of power, it is recommended that women should hold half of the total seats in board rooms;5 however, a ratio between 40% and 60%, also known as a ‘gender balance zone’,6 is considered acceptable—a threshold that is set by the European Commission.4

From the perspective of gender equity in academia and scientific research, gender parity in scientific authorship is an important measure of achievement.7 The term gender parity refers to ‘the equal contribution of women and men to different dimensions of life’ and it is operationalised as a ‘relative equality in terms of numbers and proportions of women and men’ for a particular indicator.8 Gender (dis)parity in scientific authorship has important implications for gender equity in academic advancement9 because scientific authorship is commonly used as a measure of academic productivity that is used for performance management, reward and recognition.10 11 The acceleration of women’s advancement and leadership in research is one of the stated objectives of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) in the UK and it is imperative for RRI in the wider European research area. Yet, there is limited research concerning gender equity in scientific authorship of translational research funded through NIHR biomedical research centres (BRCs).

In the UK, women currently outnumber men in medical schools;12 however, a persistent gender disparity in scientific publications remains.11 13–24 While the proportion of women as first and senior (last) authors of original medical research has increased over the past few decades,25 women are still significantly underrepresented as authors of research articles in medical journals, especially as first and senior (last) authors,19–21 23 which are considered as prestigious authorship positions.11 15 For example, in radiology the proportion of women as first author increased from 8% in 1978 to 32% in 2013 and senior author increased from 7% in 1978 to 22% in 2013.21 Similarly, in gastroenterology the proportion of women as first author increased from 9% in 1992 to 29% in 2012, and senior author increased from 5% in 1992 to 15% in 2012.23

The profile of gender equity in higher education and research has been raised by the introduction of Athena SWAN-linked funding incentives by the NIHR.26–29 While Athena SWAN awards are useful markers of achievement for higher education institutions and research centres and institutes, they alone are insufficient to assess and monitor the progress of NIHR BRCs towards gender equity.30 In this regard, tracking of the proportion of women and rate of their achievements is important; however, it is not routinely recorded in NIHR BRCs. It is therefore important to examine the acceleration of women’s advancement and leadership in translational research in line with the stated objectives of the NIHR within the UK and RRI within the wider European research area through the collection of gender-disaggregated bibliometric data and analysis of scientific authorship by gender.

The primary objective of this study was to assess the gender parity in six types of scientific authorship in biomedical research. The secondary objective was to assess whether male and female authors publish articles in journals with different prestige levels.

Methods

Study design

Descriptive, cross-sectional, retrospective bibliometric study.

Setting

This study was conducted at the NIHR Oxford BRC, which is a research collaboration between the Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and the University of Oxford.31 The NIHR BRCs support translational research and innovation to improve healthcare for patients.32 During the study period (April 2012–March 2017), the NIHR Oxford BRC was awarded £96m to support research across nine research themes, five cross-cutting themes and a range of underpinning platforms. The research themes included blood, cancer, cardiovascular, dementia and cerebrovascular disease, diabetes, functional neuroscience and imaging, infection, translational physiology, and vaccines. The crosscutting themes included genomic medicine, immunity and inflammation, surgical innovation and evaluation, biomedical informatics and technology, and prevention and population care. The major underpinning platforms included a biorepository, education and training, public engagement, and research governance. Staff who have all or part of their salary funded through the BRC award are members of the NIHR faculty. During the study period (April 2012–March 2017), there were 74% (n=1268) male and 26% (n=454) female principal investigators (scientists that have won research grants and are ultimately responsible for the conduct of research studies); 60% (n=600) male and 40% (n=404) female NIHR investigators (scientists leading and undertaking research, lead researchers, other senior researchers and research assistants); and 53% male (n=446) and 47% (396) female NIHR trainees (those engaged in research training leading to a higher degree by research). It is a contractual requirement to report the number of BRC supported publications published by researchers funded or supported by the NIHR research funds on an annual basis. Additionally, the NIHR uses bibliometric analyses to inform eligibility for its funding.33 34 This study was carried out as part of a wider programme of research on the markers of achievement for assessing and monitoring gender equity in translational research organisations.7 30

Data

Data comprised translational research publications published by researchers funded or supported by the NIHR Oxford BRC. The eligibility criteria for inclusion of a publication were: funding or support by the NIHR Oxford BRC and publication or acceptance between April 2012 and March 2017. Based on these criteria, 2409 publications were identified. These publications were classified as: basic science studies, clinical studies (both trial and non-trial studies) and other studies (comments, editorials, systematic reviews, reviews, opinions, meeting reports, guidelines and protocols) (table 1).

Table 1.

Number and types of publication by year of acceptance

| Year (accepted) | Types of publication, count (%) | Total, count (%) | |||

| Basic science | Clinical trial | Clinical study—not a trial | Other* | ||

| 2012† | 75 (27.6) | 18 (6.6) | 90 (33.1) | 89 (32.7) | 272 (100) |

| 2013‡ | 151 (28.2) | 27 (5.0) | 183 (34.2) | 174 (32.5) | 535 (100) |

| 2014‡ | 122 (22.2) | 29 (5.3) | 204 (37.2) | 194 (35.3) | 549 (100) |

| 2015‡ | 137 (24.7) | 48 (8.7) | 158 (28.5) | 211 (38.1) | 554 (100) |

| 2016‡ | 137 (31.8) | 31 (7.2) | 120 (27.8) | 143 (33.2) | 431 (100) |

| 2017§ | 21 (30.9) | 5 (7.4) | 26 (38.2) | 16 (23.5) | 68 (100) |

| Total | 643 (26.7) | 158 (6.6) | 781 (32.4) | 827 (34.3) | 2409 (100) |

*Systematic reviews, reviews, research protocols, editorials, guidelines, opinions, comments and meeting reports.

†April–December.

‡January–December.

§January–March.

Main outcome measures

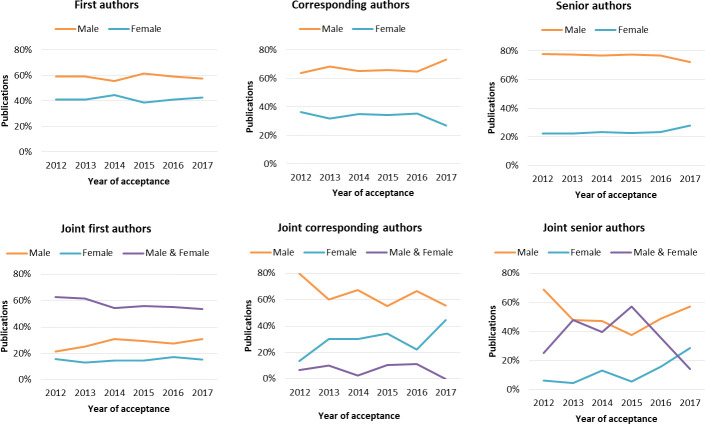

The main outcome measures were: (1) gender of authors, defined as a binary variable comprising either male or female categories, (2) six categories of scientific authorship: first author, joint first authors, first corresponding author, joint corresponding authors, last author and joint last authors (figure 1). These categories are conventionally associated with the highest amount of contribution, credit and prestige.11 15

Figure 1.

Publication analysis workflow. The workflow shows the process of extracting data according to gender from six types of authorship.

First author was defined as the first-named author of the publication. Publications that consisted of single authors were categorised as first authors. We considered the first author to be the main intellectual contributor in the publication, in terms of study design, data collection and analysis, and manuscript writing. Joint first authors were defined as two or more authors who were named as equal contributors and mentioned as joint first authors of the publication. The first corresponding author was defined as the only author who was reported as a corresponding author in the publication and his/her contact details such as an institutional address and/or an email address were provided for correspondence in the publication. Joint corresponding authors were defined as two or more authors who were listed or marked as corresponding authors and their contact details were provided for correspondence in the publication. Last author was defined as the last-named author of a publication. The last author was considered to be a group leader or principal investigator who may have provided significant intellectual contribution or supervision of the research work as well as acquisition of research funding.15 35 Joint last authors were defined as two or more authors who were named as equal contributors in the publication and their names were mentioned as joint last authors in the publication. A major confounding factor, for which we could not control, was the informal nature of the conventions for the sequence and role of authors.35 Although conventions for scientific authorship are well established in biomedical sciences,36 37 they may vary between different research areas and even between different research groups within the same area.

Determination of gender of authors

The gender of the authors, (defined as a binary variable comprising either male or female categories) was determined based on the first name of authors in all six categories of authorship. When the first names of authors were initialled in the publication or were difficult to associate with either male or female gender, further information was sought through searching their institutional webpages and online social network sites such as the LinkedIn and ResearchGate. We also used two novel application programming interfaces (APIs) for determining gender of first name. These APIs were gender-api.com and genderapi.io. In addition, we contacted five authors directly via email to ascertain their gender. After completing data coding by two researchers (MJM and RD), to ensure the accuracy of data coding, 10% of the data were checked independently (CRH). Consensus was achieved through discussion between the researchers on data fields that did not match the assigning of the gender of authors and types of authorship (figure 1).

Gender of authors and journal prestige

For assessing whether male and female authors publish articles in less, equal or more prestigious journals, we used journal impact factor as a proxy for the prestige of a journal. We extracted data on journal impact factors from the Journal Citation Report 2019; and for a few articles we used the latest available impact factor reported on the journal websites.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using frequencies including counts and percentages. χ2 tests were used for identifying statistically significant differences and associations between male and female authors in various categories of authorship. Cochrane linear trend test was used to determine trends over time using a Microsoft Excel add-in tool by Slezák et al.38 T-tests were used to determine differences in the mean impact factor of journals with publications by male and female authors in three authorship categories: first, first corresponding and last authors. The level of significance was set at p<0.05. Data were analysed using the IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, V.25.0 (IBM Corp.). Visualisations were created in the Microsoft Excel and BoxPlotR—a free online tool.39

Patient and public involvement statement

There was no patient or public involvement in the study design.

Results

Types of publication

Types of publications included clinical research studies (both trial and non-trial studies) 39% (n=939), basic science research 27% (n=643) and a third of publications (34%, n=827) included other types of publication, such as systematic reviews, reviews, research protocols, editorials, guidelines, opinions, comments and meeting reports (table 1).

Authorship type and gender

Table 2 presents an overview of gender of authors by types of authorship. Male authors were more likely to be first authors (59%, p<0.001), first corresponding authors (66%, p<0.001) and last authors (77%, p<0.001) (table 2). In the three joint authorship categories analysed, the proportion of ‘female only’ authors was statistically significantly lower than ‘male only’ authors in two categories: joint corresponding authors (29%, p<0.001) and joint last authors (10%, p<0.001) (table 2). However, in the joint first authors category, the proportion of ‘male and female’ as joint first authors (57%, p<0.001) was statistically significantly higher than ‘male only’ and ‘female only’ joint first authors (table 2).

Table 2.

Authorship type and gender of authors

| Authorship type (number of publications in the category) |

Gender of authors, count (%) | Significance P value |

||

| Male only | Female only | Male and female | ||

| First author (n=2407) | 1413 (58.7) | 994 (41.3) | N/A | <0.001 |

| First corresponding author (n=2371) | 1565 (66.0) | 806 (34.0) | N/A | <0.001 |

| Last author (n=2406) | 1853 (77.0) | 553 (23.0) | N/A | <0.001 |

| Joint first authors (n=458) | 127 (27.7) | 69 (15.1) | 262 (57.2) | <0.001 |

| Joint corresponding authors (n=169) | 107 (63.3) | 49 (29.0) | 13 (7.7) | <0.001 |

| Joint last authors (n=229) | 108 (47.2) | 23 (10.0) | 98 (42.8) | <0.001 |

N/A, not applicable.

Gender of authors by type of publication

Table 3 shows gender of authors by type of publication (ie, basic science, clinical trials, non-trial clinical studies and other research). The proportions of ‘male only’ authors were statistically significantly higher than the proportions of ‘female only’ authors in three authorship categories: first authors (p=0.035), first corresponding authors (p<0.001) and last authors (p=0.016) (table 3). There were no significant differences between the proportions of ‘male only’ and ‘female only’ authors in all three joint authorship categories: joint first authors (p=0.476), joint corresponding authors (p=0.172) and joint last authors (p=0.208). Only the statistically significant associations are shown in table 3.

Table 3.

Gender of authors by publication type

| Type of research | Publication type, count (%) | Significance P value |

|||

| Basic science | Clinical trial | Clinical study—not a trial | Other | ||

| First author | 0.035 | ||||

| Male | 371 (57.8) | 92 (58.6) | 433 (55.4) | 517 (62.5) | |

| Female | 271 (42.2) | 65 (41.4) | 348 (44.6) | 310 (37.5) | |

| First corresponding author | <0.001 | ||||

| Male | 446 (70.0) | 100 (64.1) | 465 (60.2) | 554 (68.7) | |

| Female | 191 (30.0) | 56 (35.9) | 307 (39.8) | 252 (31.3) | |

| Last author | 0.016 | ||||

| Male | 503 (78.3) | 125 (79.6) | 570 (73.1) | 655 (79.2) | |

| Female | 139 (21.7) | 32 (20.4) | 210 (26.9) | 172 (20.8) | |

Yearly trends in authorship by gender

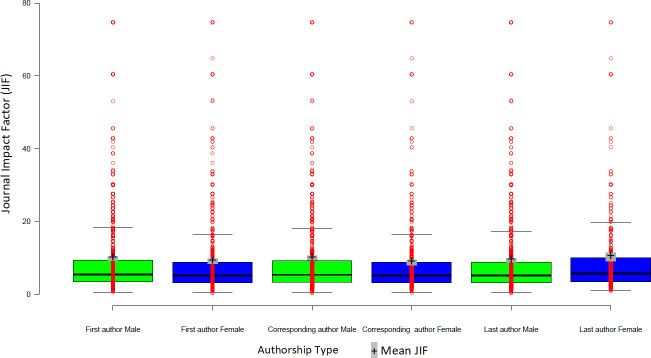

Figure 2 presents the yearly trends in scientific authorship by gender. In all six authorship types and across all 5 years of publication (April 2012–March 2017), the proportions of male and female authors varied (figure 2). Women were significantly underrepresented across all years and authorship types. Interestingly, joint first authorship indicated a higher proportion of ‘male and female’ authors compared with ‘male only’ and ‘female only’ authors (figure 2). The results of Cochrane linear trend test revealed no statistically significant change over time for all six authorship types over the years of publication.

Figure 2.

Yearly trends in scientific authorship by gender (male and female), April 2012–March 2017. This plot represents the yearly variation of the proportion of male and female authors according to six types of authorship between the years of publication/acceptance from 2012 to 2017.

Association between same gender across authorship categories

There was a statistically significant association (p<0.001) between the same gender, that is, male gender in first author and first corresponding author categories and female gender in first author and joint first authors categories (table 4A).

Table 4A.

Association between same genders across authorship categories

| First author, count (%) | Significance P value |

||

| Male | Female | ||

| First corresponding author | <0.001 | ||

| Male | 1236 (79) | 329 (21) | |

| Female | 158 (19.6) | 648 (80.4) | |

| First joint authors | <0.001 | ||

| Male only | 124 (97.6) | 3 (2.4) | |

| Female only | 10 (14.5) | 59 (85.5) | |

| Both male and female | 140 (53.6) | 121 (46.4) | |

Furthermore, there were statistically significant associations (p<0.001) between the same gender in the last author category with the same gender of first author, first corresponding author, joint corresponding author and joint last author categories (table 4B).

Table 4B.

Association between same genders across authorship categories

| Authorship type | Last author, count (%) | Significance P value |

|

| Male | Female | ||

| First author | <0.001 | ||

| Male | 1146 (61.8) | 267 (48.3) | |

| Female | 707 (38.2) | 286 (51.7) | |

| First corresponding author | <0.001 | ||

| Male | 1429 (78.4) | 136 (24.7) | |

| Female | 394 (21.6) | 412 (75.3) | |

| Joint corresponding authors | <0.001 | ||

| Male only | 104 (84.5) | 3 (6.7) | |

| Female only | 13 (10.6) | 36 (80) | |

| Both male and female | 6 (4.9) | 6 (13.3) | |

| Joint last authors | <0.001 | ||

| Male only | 106 (63.9) | 2 (3.2) | |

| Female only | 2 (1.2) | 21 (33.3) | |

| Both male and female | 58 (34.9) | 40 (63.5) | |

However, there was no statistically significant association between male and female last authors with the respective gender of joint first authors (p=0.117). Only the statistically significant associations are shown in tables 4A and 4B.

Gender of authors and journal prestige

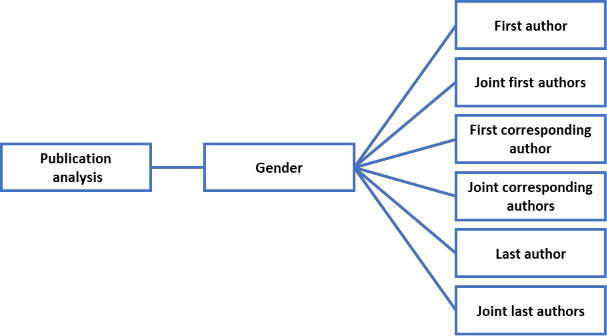

Of 2388 journal articles, 96.6% (n=2307) were published in journals having an impact factor (mean=9.58 (±12.16), median=5.36, minimum=0.39, maximum=74.7) while only 3.4% (n=81) articles were published in journals having no impact factor. There was no statistically significant difference in the mean journal impact factor (JIF) by gender of first and last authors; however, the mean JIF was statistically significantly higher for male first corresponding authors compared with female first corresponding authors (table 5 and figure 3).

Table 5.

Journal impact factor (JIF) and authorship categories by gender

| Authorship type | Mean JIF | SD | 95% CI | P value |

| First author | 0.171 | |||

| Male | 9.88 | 12.46 | 9.18 to 10.58 | |

| Female | 9.14 | 11.73 | 8.37 to 9.92 | |

| First corresponding author | 0.020 | |||

| Male | 10.00 | 12.72 | 9.34 to 10.67 | |

| Female | 8.77 | 10.95 | 7.97 to 9.57 | |

| Last author | 0.115 | |||

| Male | 9.34 | 11.76 | 8.77 to 9.91 | |

| Female | 10.40 | 13.38 | 9.21 to 11.59 |

Figure 3.

Authorship type by gender and impact factor of journals. This figure shows the boxplots of impact factors of journals in which male and female authors published articles.

Discussion

We studied gender parity in the authorship of translational research publications (n=2409) produced by researchers affiliated with the NIHR Oxford BRC, which is one of the largest of 20 NIHR BRCS in England. We determined gender of authors in six different categories of authorship that included three types of joint authorships in biomedical research, which is the most unique feature of this study and to our best knowledge it has been done for the first time in this study.

In the first author category, we found proportions of female authors and male authors within the 40%–60% ‘gender balance zone’.6 In the last (senior) author category, the observed proportion of female last authors (23%) was lower than male last authors (77%) but it was higher than reported in other studies.12 14 25 In the context of biomedical research in the UK, principal investigators (PIs) are typically last authors.40 In the current study setting, that is, NIHR Oxford BRC, the proportion of male PIs was 74% and the remaining 26% were female PIs during the period of analysis. Thus, it appears that the representation of male and female last authors was proportionate to their respective proportions as PIs in the BRC. These findings suggest positive trends and the NIHR Oxford BRC doing very well in gender parity in the senior (last) authorship category.

This study extends understanding of gender-based trends in scientific authorship (figure 2) by showing encouraging incremental changes in gender parity in authorship in a biomedical research setting. Previous research examined the gender gap in authorship within the medical literature reporting an upward trend for female first authors from 6% in 1970 to 29% in 2004 and female last authors from 4% in 1970 to 19% 2004. However, it was limited to US based institutions.13 A similar UK based study covering the same period (ie, 1970–2004) also showed upward trends for female first authors increasing (from 11% in 1970 to 37% in 2004) and female last authors (from 12% in 1970 to 17% in 2004).25 In addition, a recent study by Filardo et al14 examined the prevalence of female first authorship of original research published in six high impact general medical journals between February 1994 and June 2014, which revealed that the adjusted probability of an article having a female first authorship increased significantly from 27% in 1994 to 37% in 2014.14 However, despite the proportion of female first authors varied greatly by journal, men were generally more likely to be first authors than women.14 Compared with previous studies mentioned above, our study provides evidence of higher and increasing gender equity in the first authors, last authors and other four categories of scientific authorship in biomedical research (table 2).

We found a strong association between same gender and authorship types showing if the first author of a publication was male, it was highly likely that the first corresponding author of the same publication would also be male. Similarly, the likelihood of the first author being female was higher, if the first corresponding author was also female.41 Likewise, there appeared to be a significant association of male and female last authors with the respective gender of first authors. Previous research has highlighted males and females were more likely to be first authors on papers if the last authors were of the same gender;21 42–44 however, these were not conducted in a translational research setting. Our findings also revealed a strong association of male and female last authors with the respective gender of corresponding authors.44

However, due to the differences in gender equity between different research areas and medical specialities, where a centre-specific mix of research themes is likely to influence gender equity in scientific authorship, it is difficult to make direct comparisons across the literature.

In regards to gender parity in authorship of scientific publications, which is an important marker of achievement for gender equity,7 our study builds an important evidence base in biomedical research settings and our results support previous studies.13 25 45–47

We found that male first corresponding authors were more likely to publish articles in high impact factor journals compared with female first corresponding authors (table 6). The practice of corresponding author varies between institutions, academic disciplines and countries48 but usually the first corresponding author is either a researcher who has done major research work or a senior investigator who is overall responsible for the research study/project.15 35 49 We do not have sufficient information to ascertain whether male first corresponding authors in our study were investigators or junior researchers or doctoral candidates. However, our findings suggest that female first corresponding authors are less likely to publish articles in high impact journals.

More importantly, our study shows that both the male and the female biomedical researchers publish articles at prestigious authorship positions, that is, first and last authors in journals with high impact factors (figure 3) and no statistically significant associations between the gender of first and last authors and the journal impact factor were identified.50 In contrast, Bendels et al reported that female researchers were less likely to publish in high impact factor journals at prestigious authorship positions.45 This could be due to the differences in journals analysed, research disciplines included and the time period covered. Our analysis included a wide range of journals in which researchers affiliated with the NIHR Oxford BRC published translational research from April 2012 to March 2017 while Bendels et al analysed only the Nature Index journals in four disciplines, that is, life science, multidisciplinary, earth and environmental and chemistry covering publication period from January 2008 to May 2016.45

Implications for policy and practice

While NIHR BRCs routinely collect bibliometric data on publications arising from the NIHR-funded research, and report to the NIHR (the funder), to the best of our knowledge, this data is not routinely analysed by gender. Our study provides the feasibility of using NIHR BRCs funded or supported research publications for analysing scientific authorship by gender. While retrospective analysis of the gender of authors in scientific publications is labour-intensive and has limitations, there is an opportunity to begin to track this prospectively. As more data become available, this would enable longitudinal analysis of gender in scientific authorship, which could be useful for tracking progress towards gender equity and related issues such as markers of achievement across all NIHR BRCs.7

In addition, since the acceleration of women’s advancement and leadership in translational research is one of the stated objectives of the NIHR, investigating the extent of gender equity in scientific authorship may usefully inform strategies to accelerate women’s advancement and leadership in NIHR-funded research. Moreover, bibliometric analyses used by the NIHR to inform competition for NIHR funding may incorporate the gender dimension into the analysis, which could provide additional information on the competitiveness for NIHR funding.51 52

Conclusion

Although, the proportions of female authors is significantly lower than the proportions of male authors in all six categories of authorship included in our analysis, first authorship is within the 40%–60% gender balance zone and the proportion of male and female last authors is proportionate to their respective proportions as principal investigators in the NIHR Oxford BRC. This may suggest a positive trend in gender parity in the senior (last) author category in scientific publications produced by the BRC during April 2012–March 2017. This study provides evidence that both male and female authors at first and last authorship positions publish articles in journals with almost equal impact factor; however, male first corresponding authors are more likely to publish articles in prestigious journals with high impact factor. We also conclude that it is feasible to analyse bibliometric data on publications arising from NIHR funding by gender and consider establishing processes for monitoring gender equity in scientific authorship as an important marker of achievement in the context of NIHR BRCs.7

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the editors and reviewers who provided constructive feedback and suggestions which improved this work. The authors also wish to thank Professor Helen McShane for reviewing the initial draft manuscript and making comments and suggestions for improving it.

Footnotes

Twitter: @SarwarShahUK, @rinitadam

SGSS and RD contributed equally.

Contributors: LDE conceived the study. RD and MJM coded the data. SGSS analysed the data and created visualisations. RD and SGSS drafted and finalised the manuscript. PVO contributed to the conception of the study. PVO and LRH co-wrote parts of the manuscript. CRH and OC participated in data collection. VK, LRH and AMB contributed to the conception of the study, facilitated access to the publications and coordinated the study. All authors read, contributed to and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This study was funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme award STARBIOS2 under grant agreement No. 709517 and by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Oxford Biomedical Research Centre, grant BRC-1215-20008 to the Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and the University of Oxford. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Competing interests: VK is Chief Operating Officer and LRH is Clinical Research Manager at the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Oxford Biomedical Research Centre (BRC). AMB is a senior medical science advisor and co-founder of Brainomix, a company that develops electronic ASPECTS (e-ASPECTS), an automated method to evaluate ASPECTS in stroke patients. MJM, LDE and PVO were funded by STARBIOS2 and the NIHR Oxford BRC. PVO is a member of the NIHR Advisory Group on Equality, Diversity, and Inclusion, a member of the European Association of Science Editors Gender Policy Committee, and a member of the Athena SWAN Self-Assessment Team of the Radcliffe Department of Medicine, University of Oxford.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The University of Oxford Clinical Trials and Research Governance Team reviewed the study and deemed it exempt from full ethics review on the grounds that it falls outside of the Governance Arrangements for Research Ethics Committees (GAfREC), which stipulate which publications are required to have ethics review. A wider programme of research on the activities of the NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre from 2017 to 2022 received ethics clearance through the University of Oxford Central University Research Ethics Committee (R51801/ RE001), the Health Research Authority (IRAS ID 228049) and the Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust Management (PID 12779).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available upon reasonable request from authors.

References

- 1.Colizzi V, Mezzana D, Ovseiko PV, et al. Structural transformation to attain responsible biosciences (STARBIOS2): protocol for a horizon 2020 funded European multicenter project to promote responsible research and innovation. JMIR Res Protoc 2019;8:e11745. 10.2196/11745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elster D, Barendziak T, Birkholz J. Towards a sustainable and open science: recommendations for enhancing responsible research and innovation in the biosciences at the University of Bremen. Duren, Germany: Shaker Verlag, 2019. ISBN: 978-3-8440-7076-7 [Google Scholar]

- 3.European Commission . Indicators for promoting and monitoring responsible research and innovation. Report from the expert group on policy indicators for responsible research and innovation, 2015. Available: http://ec.europa.eu/research/swafs/pdf/pub_rri/rri_indicators_final_version.pdf [Accessed 19 Feb 2020].

- 4.European Commission . Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on improving the gender balance among non-executive directors of companies listed on stock exchanges and related measures, 2012. Available: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52012PC0614 [Accessed 19 Feb 2020].

- 5.European Commission . Report on equality between women and men in the European Union. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2019: 1–78. ISBN: 978-92-76-00028-0. 10.2838/776419 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuhlmann E, Ovseiko PV, Kurmeyer C, et al. Closing the gender leadership gap: a multi-centre cross-country comparison of women in management and leadership in academic health centres in the European Union. Hum Resour Health 2017;15:1–7. 10.1186/s12960-016-0175-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Henderson LR, Shah SGS, Ovseiko PV, et al. Markers of achievement for assessing and monitoring gender equity in a UK National Institute for health research biomedical research centre: a two-factor model. PLoS One 2020;15:e0239589. 10.1371/journal.pone.0239589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.European Institute for Gender Equality. gender parity, 2020. Available: https://eige.europa.eu/thesaurus/terms/1195 [Accessed 19 Feb 2020].

- 9.Rexrode KM. The gender gap in first authorship of research papers. BMJ 2016;1130:i1130. 10.1136/bmj.i1130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bloch C, Graversen EK, Pedersen HS. Competitive research grants and their impact on career performance. Minerva 2014;52:77–96. 10.1007/s11024-014-9247-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bendels MHK, Müller R, Brueggmann D, et al. Gender disparities in high-quality research revealed by nature index journals. PLoS One 2018;13:e0189136–21. 10.1371/journal.pone.0189136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jefferson L, Bloor K, Maynard A. Women in medicine: historical perspectives and recent trends. Br Med Bull 2015;114:5–15. 10.1093/bmb/ldv007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jagsi R, Guancial EA, Worobey CC, et al. The "gender gap" in authorship of academic medical literature--a 35-year perspective. N Engl J Med 2006;355:281–7. 10.1056/NEJMsa053910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Filardo G, da Graca B, Sass DM, et al. Trends and comparison of female first authorship in high impact medical journals: observational study (1994-2014). BMJ 2016;352:i847. 10.1136/bmj.i847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bendels MHK, Wanke E, Schöffel N, et al. Gender equality in academic research on epilepsy-a study on scientific authorships. Epilepsia 2017;58:1794–802. 10.1111/epi.13873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bendels MHK, Brüggmann D, Schöffel N, et al. Gendermetrics of cancer research: results from a global analysis on lung cancer. Oncotarget 2017;8:101911–21. 10.18632/oncotarget.22089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bendels MHK, Dietz MC, Brüggmann D, et al. Gender disparities in high-quality dermatology research: a descriptive bibliometric study on scientific authorships. BMJ Open 2018;8:e020089. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bendels MHK, Costrut AM, Schöffel N, et al. Gendermetrics of cancer research: results from a global analysis on prostate cancer. Oncotarget 2018;9:19640–9. 10.18632/oncotarget.24716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sing DC, Jain D, Ouyang D. Gender trends in authorship of spine-related academic literature-a 39-year perspective. Spine J 2017;17:1749–54. 10.1016/j.spinee.2017.06.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schisterman EF, Swanson CW, Lu Y-L, et al. The changing face of epidemiology: gender disparities in citations? Epidemiology 2017;28:159–68. 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Piper CL, Scheel JR, Lee CI, et al. Gender trends in radiology authorship: a 35-year analysis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2016;206:3–7. 10.2214/AJR.15.15116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mueller CM, Gaudilliere DK, Kin C, et al. Gender disparities in scholarly productivity of US academic surgeons. J Surg Res 2016;203:28–33. 10.1016/j.jss.2016.03.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Long MT, Leszczynski A, Thompson KD, et al. Female authorship in major academic gastroenterology journals: a look over 20 years. Gastrointest Endosc 2015;81:1440–7. 10.1016/j.gie.2015.01.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fishman M, Williams WA, Goodman DM, et al. Gender differences in the authorship of original research in pediatric journals, 2001-2016. J Pediatr 2017;191:244–9. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.08.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sidhu R, Rajashekhar P, Lavin VL, et al. The gender imbalance in academic medicine: a study of female authorship in the United Kingdom. J R Soc Med 2009;102:337–42. 10.1258/jrsm.2009.080378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ovseiko PV, Chapple A, Edmunds LD, et al. Advancing gender equality through the Athena Swan charter for women in science: an exploratory study of women's and men's perceptions. Health Res Policy Syst 2017;15:12. 10.1186/s12961-017-0177-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ovseiko PV, Pololi LH, Edmunds LD, et al. Creating a more supportive and inclusive university culture: a mixed-methods interdisciplinary comparative analysis of medical and social sciences at the University of Oxford. Interdiscip Sci Rev 2019;44:166–91. 10.1080/03080188.2019.1603880 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmidt EK, Ovseiko PV, Henderson LR. Understanding the Athena Swan Award scheme for gender equality as a complex social intervention in a complex system: analysis of silver Award action plans in a comparative European perspective. bioRxiv 2019:555482 10.1101/555482 10.1101/555482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ovseiko PV, Taylor M, Gilligan RE, et al. Effect of Athena SWAN funding incentives on women's research leadership. BMJ 2020;371:m3975. 10.1136/bmj.m3975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ovseiko PV, Edmunds LD, Pololi LH, et al. Markers of achievement for assessing and monitoring gender equity in translational research organisations: a rationale and study protocol. BMJ Open 2016;6:e009022. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.NIHR Oxford BRC . About the NIHR Oxford biomedical research centre, 2019. Available: https://oxfordbrc.nihr.ac.uk/about-us-intro/ [Accessed 19 Dec 2019].

- 32.Greenhalgh T, Ovseiko PV, Fahy N, et al. Maximising value from a United Kingdom biomedical research centre: study protocol. Health Res Policy Syst 2017;15:70. 10.1186/s12961-017-0237-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gunashekar S, Parks S, Calero-Medina C, Visser M, van Honk J, Wooding S. Bilbliometric analysis of highly cited publications of biomedical and health research in England, 2004--2013. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2015: 1–83. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR1363.html 10.7249/RR1363 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gunashekar S, Wooding S, Guthrie S. How do NIHR peer review panels use bibliometric information to support their decisions? Scientometrics 2017;112:1813–35. 10.1007/s11192-017-2417-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tscharntke T, Hochberg ME, Rand TA, et al. Author sequence and credit for contributions in multiauthored publications. PLoS Biol 2007;5:0013–14. 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wren JD, Kozak KZ, Johnson KR, et al. The write position. A survey of perceived contributions to papers based on byline position and number of authors. EMBO Rep 2007;8:988–91. 10.1038/sj.embor.7401095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.ICMJE . Defining the role of authors and contributors, 2019. Available: http://www.icmje.org/recommendations/browse/roles-and-responsibilities/defining-the-role-of-authors-and-contributors.html [Accessed 23 Dec 2019].

- 38.Slezák P, Bokes P, Námer P, et al. Microsoft Excel add-in for the statistical analysis of contingency tables. Int J Innov Educ Res 2014;2:90–100. 10.31686/ijier.vol2.iss5.188 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spitzer M, Wildenhain J, Rappsilber J, et al. BoxPlotR: a web tool for generation of box plots. Nat Methods 2014;11:121–2. 10.1038/nmeth.2811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Patel VM, Panzarasa P, Ashrafian H, et al. Collaborative patterns, authorship practices and scientific success in biomedical research: a network analysis. J R Soc Med 2019;112:245–57. 10.1177/0141076819851666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ouyang D, Harrington RA, Rodriguez F. Association between female corresponding authors and female Co-Authors in top contemporary cardiovascular medicine journals. Circulation 2019;139:1127–9. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.037763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fox CW, Burns CS, Muncy AD, et al. Gender differences in patterns of authorship do not affect peer review outcomes at an ecology Journal. Funct Ecol 2016;30:126–39. 10.1111/1365-2435.12587 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Salerno PE, Páez-Vacas M, Guayasamin JM, et al. Male principal investigators (almost) don’t publish with women in ecology and zoology. PLoS One 2019;14:e0218598–14. 10.1371/journal.pone.0218598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Edwards HA, Schroeder J, Dugdale HL. Gender differences in authorships are not associated with publication bias in an evolutionary Journal. PLoS One 2018;13:e0201725 10.1371/journal.pone.0201725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bendels MHK, Müller R, Brueggmann D, et al. Gender disparities in high-quality research revealed by nature index journals. PLoS One 2018;13:e0189136. 10.1371/journal.pone.0189136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Feramisco JD, Leitenberger JJ, Redfern SI, et al. A gender gap in the dermatology literature? cross-sectional analysis of manuscript authorship trends in dermatology journals during 3 decades. J Am Acad Dermatol 2009;60:63–9. 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.06.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bhattacharyya N, Shapiro NL. Increased female authorship in otolaryngology over the past three decades. Laryngoscope 2000;110:358–61. 10.1097/00005537-200003000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Duffy MA. Last and corresponding authorship practices in ecology. Ecol Evol 2017;7:8876–87. 10.1002/ece3.3435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu C, Fuller S, Shi Z, et al. The gender gap in commenting: women are less likely than men to comment on (men's) published research. PLoS One 2020;15:e0230043. 10.1371/journal.pone.0230043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fox CW, Ritchey JP, Paine CET. Patterns of authorship in ecology and evolution: first, last, and corresponding authorship vary with gender and geography. Ecol Evol 2018;8:11492–507. 10.1002/ece3.4584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.van Leeuwen T, Hoorens S, Grant J. Using bibliometrics to support the procurement of NIHR biomedical research centres in England. Res Eval 2009;18:71–82. 10.3152/095820209X414178 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.van Leeuwen T, Grant J. Bibliometric analysis of highly cited publications of health research in England, 1995-2004. Santa Monica, CA:RAND Corporation; 2007. https://www.rand.org/pubs/working_papers/WR368.html[Accessed 19 Feb 2020]. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.