Abstract

Purpose of review:

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) are increasingly understood to play a central role in tumor progression. Growing evidence implicates tumor microenvironments as a source of signals that regulate or even impose CSC states on tumor cells. This review explores points of integration for microenvironment-derived signals that are thought to regulate CSCs in carcinomas.

Recent findings:

CSC states are directly regulated by the mechanical properties and extra cellular matrix (ECM) composition of tumor microenvironments that promote CSC growth and survival, which may explain some modes of therapeutic resistance. CSCs sense mechanical forces and ECM composition through integrins and other cell surface receptors, which then activate a number of intracellular signaling pathways. The relevant signaling events are dynamic and context-dependent.

Summary:

CSCs are thought to drive cancer metastases and therapeutic resistance. Cells that are in CSC states and more differentiated states appear to be reversible and conditional upon the components of the tumor microenvironment. Signals imposed by tumor microenvironment are of a combinatorial nature, ultimately representing the integration of multiple physical and chemical signals. Comprehensive understanding of the tumor microenvironment-imposed signaling that maintains cells in CSC states may guide future therapeutic interventions.

Keywords: Cancer stem cell, tumor microenvironment, mechano-signaling, extracellular matrix, signaling integration

Introduction

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) are thought to be a subpopulation of tumor cells that have the capacity to self-maintain and give rise to the other cells that comprise the bulk of the tumor. CSCs are central players in therapeutic resistance, and they are imbued with the potential to spread and initiate growth in distant locations. CSC have been identified in many cancers, but it is not clear if all cancer types have CSC. Part of the confusion surrounding CSCs is a lack of consistency in the markers used to enrich for them, for even within one type of cancer there is little consensus as to the identity of the entity. An explanation of this could be that CSCs and more differentiated cancer cells represent transition states, and that any cancer cell can occupy those states given the correct set of equilibrium conditions [reviewed in (1)]. Thus, CSCs may be better conceptualized as having a functional state rather than as definable entities.

Tissue-specific stem cells are maintained in specialized microenvironments, often called niches, and this is a reasonable expectation also for CSCs. We have speculated that one impact of heterogeneity within a tumor is variability in microenvironments leading to some that maintain cells with CSC functions and others that impose more differentiated states (2). Such heterogeneity may underlie the wide variations of reported frequencies of CSCs which range from 0.0001% to 40% of cells in a tumor (3). The more traditionally held view that CSCs comprise a relatively rare sub-population of tumor cells is also challenged by a study of aggressive breast cancers in which it was found that adaptation of all tumor cell populations could mediate chemo resistance, not just one specific subpopulation (4). Similarly, in sporadic melanomas, expression of batteries of genes made some cells tolerant to targeted therapeutics, but this expression pattern was not limited to a specific sub-population (5). In a diverse collection of combinatorial microenvironments comprised of different combinations of tumor microenvironment components, epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) and stem cell marker expression, and tolerance to anti-cancer drugs in cancer cells were determined by specific combinations of microenvironment components (6,7). Thus, tumor cells in multiple cancers exhibit properties of CSCs, and expression of genes and proteins that are often synonymous with CSC states are heavily influenced by the tumor ME.

The microenvironment is defined as the sum of cell-cell, cell-extracellular matrix (ECM), cell-soluble factor and chemical interactions, physical forces, and geometric constraints that are experienced by cells. That cell phenotypes and functions seem inextricably linked to their microenvironment suggests that it is essential to cells to sense and interact with their microenvironment. It is not well understood how cells integrate these very different types of microenvironment signals. In this review, we focus on two of the most stable microenvironment factors: mechanical forces and ECM.

ECM is a structural component of tissues and tumors, and it provides a scaffold where cells attach, however, the cell-ECM relationship is not one of inert interactions. ECM binds also to soluble ligands and acts as a reservoir for growth factors and cytokines. ECM can chemically and physically prevent cytotoxic drugs from penetrating deep within tumors (8). ECM is consists of structural proteins, such as collagens; cell-adhesion proteins, such as laminins and fibronectin; proteoglycans and polysaccharides, such as hyaluronan. Fibrillary collagens provide mechanical support, whereas proteoglycans and polysaccharides bind water and increase the viscosity of the matrix. These structural factors together determine the ECM stiffness, porosity and spatial organization, whereas the composition of cell adhesion proteins in ECM are central to cell-ECM interactions.

ECM composition and organization undergoes radical transformation during carcinoma progression. Remodeling of basement membrane proteins is among the first ECM transformations to occur during cancer progression and it may be crucial to enabling epithelial cell invasion into the stromal compartment. Further, collagen fibers are linearized and type I collagen and fibronectin are highly often abundant in tumor microenvironments. Most tumors are stiffer than normal parental tissues. Increased stiffness in tumors is generated by ECM crosslinking, elevated deposition, and altered organization. Solid tumors grow in confined spaces that also results in elevated pressure and interstitial fluid flow. Even though ECM is the principle mediator of mechanical forces in tissues, the mechanically generated and biochemically initiated signals are distinct, but must be integrated into a cellular response.

Regulation of CSC states by mechanical forces and ECM

CSCs exhibit activities that are reminiscent of stem cells; self-maintenance, differentiation and metabolic adaptation. Self-maintenance of CSCs is achieved through balancing proliferation, differentiation, quiescence, and apoptosis. Microenvironment stiffness is a key regulator of CSC proliferation in multiple tumor contexts (9–12). Interestingly, this regulation is tissue-specific and the tissue of origin of CSCs seems to establish the range of optimal stiffness for growth (13). Two of the most abundant ECM components of the tumor microenvironment, fibronectin and type 1 collagen, increase CSC proliferation and inhibit chemotherapy-imposed apoptosis (14–16). Thus, CSC self-maintenance can be regulated by ECM components of the tumor microenvironment.

A CSC hallmark characteristic is the ability to differentiate into the different types of cells within a tumor. A prominent tumor microenvironment ECM component, hyaluronan, supports CSC multipotent states in gliblastoma (17), and depletion of hyaluronan matrix in vivo by 4-methyl umbelliferon (4-MU) radically decreased CSC markers expression level in hepatocarcinogenesis (18). Profiling combinatorial microenvironments for their ability to impose CSC phenotypes in breast cancer cells showed that type I collagen, osteopontin and collagen VIA3 induced expression of CSC markers in breast cancer cells, the receptor tyrosine kinases Axl and cKit plus a number of EMT genes. Conversely, type IV collagen, a basement membrane component, repressed CSC marker expression (6). Vitronectin promoted CSC differentiation leading to decreased (CD44+/CD24−) CSC population in prostate and breast CSC cultures (19). These are examples whereby CSC cell fate decisions are dynamically regulated by tissue stiffness and ECM composition.

EMT is an example of epithelial plasticity, which is coopted during cancer development. Classically this cooptation is thought to pertain to a cancer cell’s ability to migrate and invade tissue, however the involvement of EMT-like states in stem cells raises the likelihood that it is involved in maintaining cancer cells in specific CSC states (e.g. epithelial vs. mesenchymal) (20). EMT is promoted by increasing tissue stiffness and by interaction with multiple ECM components, like fibronectin, proteoglycans and hyaluronan (21–23). Fibrillary type I collagen and fibronectin matrix promotes EMT by inhibiting epithelial differentiation during embryogenesis and in cancer (24). Thus, the equilibrium between epithelial and mesenchymal cancer cell phenotypes is regulated by mechanical and biochemical stimuli.

CSC growth and drug resistance properties are supported by aberrant metabolic states. CSCs across multiple tumor types show differing metabolic phenotypes, likely caused by differential effects from the tumor microenvironment, especially oxygen tension (25). Mechanical and ECM cues transmitted by signaling pathways also regulate metabolic processes (26). Stiff substrata activate, whereas compliant substrata inhibit, glycolysis in epithelial cells. Cancer cells sustained high glycolysis rates even in heterogeneous mechanical microenvironments (27). Altered CSC metabolic states combined with anti-apoptotic signals also lead to drug resistance. Tissue stiffness and fibronectin matrix promotes drug resistance and together they have a synergistic effect (7). Taken together, defining activities of stem cell states are imposed and regulated in CSCs by components and physical properties of tumor microenvironments.

The signalling toolbox for integrating mechanical and ECM cues

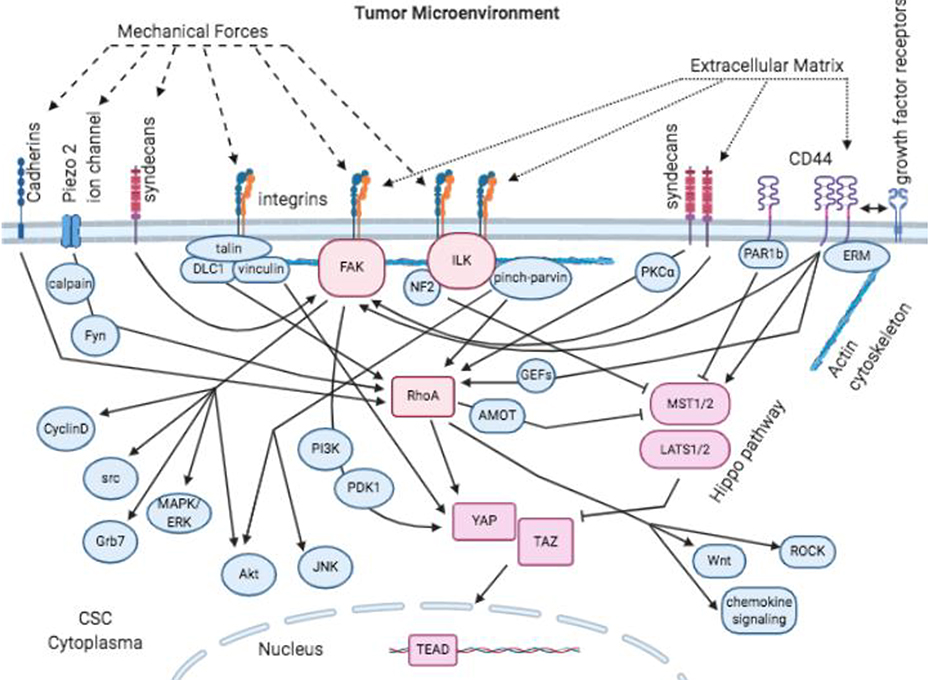

Understanding how mechanical properties and ECM composition regulate CSC states is a burgeoning field. Plasma membrane receptors and channels couple the microenvironment to intracellular signaling pathways. ECM composition sensing goes through receptors including integrins, syndecans and CD44. Cells sense mechanical forces via these same receptors, but mechanical forces can also stretch the plasma membrane to activate cadherin receptors and open mechanosensitive ion channels. Here we examine some of the receptors, signaling pathways and transcription factors that interact with both ECM and mechano-sensing processes in signal integration. A summary of the pathways is shown in Figure 1, in which the proteins that we found to have the most evidence of integration are colored in hues of red whereas other intermediates are in blue.

Figure 1. Integration of mechanical- and ECM-based tumor microenvironment-imposed signals.

Cancer stem cells sense mechanical forces and ECM to activate intracellular signaling through the indicated cell surface receptors. FAK, ILK, RhoA and hippo pathway (YAP/TAZ) are points of integration for these different types of signals that regulate CSC states.

Integrins

Integrins are heterodimeric transmembrane receptors that form a physical connection between the microenvironment and intracellular space. Integrins are comprised of 18α and 8β subunits that pair to form at least 24 different heterodimeric receptors. Each integrin subunit has unique binding sites to interact with different types of ECM, and the combination of subunits in each heterodimeric integrin determines a range of ECM binding specificities. Integrins are expressed in all human tissues, with each tissue having its own integrin subtype profile. Integrins play multiple roles in tumor progression as mediators of survival, migration and stemness (28). Integrin β1, β3, β4 and β6 subunits have been specifically implicated as CSC markers in breast, prostate, squamous cell, colorectal, lung and ovarian tumors, and mediate CSC self-maintenance and drug resistance (28,29).

When integrins bind to target ECMs they undergo conformational changes, which promote intracellular signaling via a physical linkage to the actin cytoskeleton. Their ability to respond to mechanical stimuli also is mediated through connections to the actin network. β subunits bind to α-actin or interact with linker proteins, like talin. Mechanical force unfolds the talin protein rod-domain and, depending on the unfolded state, talin will interact with different signaling molecules. For example, DLC1 attaches only within the folded rod-domain, whereas vinculin prefers to bind the unfolded rod-domain but detaches from the fully unloaded domain (30,31).

Integrin clustering within the plasma membrane amplifies the strength of an intracellular signal. Clustering is an active and spatially regulated process, and clusters form cell adhesion sites. Clusters are stabilized by cytoplasmic adhesion proteins that also link integrins to the actin cytoskeleton. Cluster stabilization leads to maturation of adhesion sites, and eventual formation of mature focal adhesions. Mature focal adhesions anchor cells to the substratum and functions as a signal carrier by activating intracellular signaling pathways (32). Integrin clustering also is promoted by ligand-independent mechanisms, such as by galectins (28), which are proteins that bind β-galactose sugars. Interestingly, galectin-3 is highly expressed by gastrointestinal CSC and promotes chemoresistance (33), suggesting a role for the glycocalyx more generally in integrin-mediated CSC regulation. Integrins are essential to so many mechanical- and ECM-triggered signaling pathways that we consider them to be essential to understanding how CSCs integrate different types of microenvironment cues.

Syndecans and CD44

Both syndecans and CD44 are associated with different CSC states. CD44 is used widely as a CSC biomarker, and syndecan-1 expression correlates with the presence of other CSC markers, including notch 1&3 and ALDH1 activity (34). Syndecan extracellular domains contain numerous glucosamine glycan chains that equip them to bind different ECMs and growth factors. Syndecans are linked closely to mechanical signaling (35, 36), and it is likely that syndecans have a role in CSC mechanosensing. Syndecan-1 knockdown reduced mammosphere and colony formation by breast cancer cells. Syndecan-1 and CD44 are co-expressed in breast CSCs, and syndecan-1 knockouts reduced CD44 expression (34) suggesting a regulatory relationship between the proteins.

CD44 is a receptor for hyaluronan polysaccharides and it also can bind the ECM protein osteopontin. CD44 has multiple transcript variants and is often subject to posttranslational modifications, and CD44 splice variants have determinative roles in breast CSC states. Deletion of the most common CD44 isoform (comprised of exons 1–5 and 16–20) impairs CSC self-renewal (37). CD44 spatial localization in cell membranes regulates its activity, colocalization and interaction with cell surface receptors like EGFR and ErbB2 leads to cancer cell migration and chemoresistance (38, 39). Homodimeric CD44 receptor clustering modulates signal transduction and increases leucocyte binding by causing extracellular hyaluronan matrix crosslinking (40). CD44 interacts with the actin cytoskeleton through ERM family proteins (ezrin, radixin and moesin). ERM protein conformations and functionality are regulated by phosphorylation states and modulate cell responses to extracellular stimuli (41). It is likely that CD44-ERM protein interactions modulate ECM- and mechanically activated signaling pathways.

Integrins, syndecans, and CD44 represent essential tools used by CSCs to integrate molecular and mechanical information from the tumor microenvironment.

Signaling pathways

FAK

Focal adhesion kinase (FAK) is a cytoplasmic tyrosine kinase and it is one of the main signaling mediators in integrin-enriched cell adhesion sites. FAK kinase integrates extracellular signals initiated by growth factors, ECM, and mechanical stimuli (42). FAK directly binds to intracellular tails of β-integrins, and integrin mediated adhesions to ECM allows rapid auto phosphorylation of Y397-FAK. FAK is activated also by several growth factor receptors, CD44 and syndecans (42–44). ECM-integrin linkages work as mechanical sensors that can activate FAK (45). Direct mechanical propagation within the plasma membrane activates FAK, for as the plasma membranes stretch the FAK domain structure unfolds in the presence of PIP2 and reveals the Y397 auto-phosphorylation site, making kinase activation possible (46). Activated FAK associates with several SH2 domain containing proteins, including Src, PI3K and Grb7. Moreover, Src kinase binding to Y397-phosphorylated FAK promotes FAK activation and signaling by contributing several additional tyrosine phosphorylation sites (47). FAK activation is known to trigger several intracellular signaling pathways including Akt, MAPK/ERK, and cyclinD1. Through these pathways it is thought to act as a regulator of cancer cell proliferation, survival, and invasion (42).

FAK expression is upregulated in many epithelial cancers, and FAK regulates a number of CSC-related functions (42). Deletion of FAK in a conditional knock out mouse mammary tumor model reduced the frequency of CSC and suppressed tumor progression (48). Type 1 collagen-integrin mediated activation of FAK increased the frequency of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma CSCs and increased tumor initiation potential (49). ECM-triggered CD44 signaling through FAK mediated resistance against drug-induced apoptosis (43). Also, potentially relevant to the CSC differentiation states, TGFβ-induced EMT is mediated by FAK-Src signaling (50), and integrin-FAK-Src signaling inhibits epithelial differentiation by interruption of E-cadherin mediated epithelial adherens junctions (42). These reports support the concept that FAK signaling has a central role in maintenance of CSC states (51).

ILK

Integrin-linked kinase (ILK) is part of the Raf-like kinase family. ILK binds to integrins and works as a scaffold protein by coupling integrin with the actin cytoskeleton, but ILK transmits signals as well. ILK localizes mainly in focal adhesion sites, but also resides in cell-cell adhesion sites, centrosomes and in the nucleus (52). ILK transmits ECM and mechanically initiated signals from integrins to intracellular signaling pathways (52–54).

ILK binds directly to integrin β1 and β3 cytoplasmic domains or via the pinch-parvin complex (IPP). Human cells express several isoforms of pinch and parvin proteins and they form distinct IPP complexes. Each distinct IPP complex that forms with ILK results in different signaling outputs. IPP complexes mediate signals to the actin cytoskeleton, RhoA, Akt, and JNK (52). Whereas ILK clearly plays a role as a signal transducer (52), the exact mechanism is still not known, for it is not clear if ILK has kinase activity, since reports have shown that its kinase-domain lacks catalytic activity (52). ILK may function by controlling subcellular localization of signaling molecules and in that way, regulate their activity, for example by recruiting Akt to the plasma membrane (55). Furthermore, the IPP proteins that associate with ILK can bind to and inhibit the activity of protein phosphatases (56).

ILK expression is upregulated in stiff regions of tumors (57), and ILK expression is associated with CSC and EMT marker expression in vivo (58). In vitro ILK signaling through Akt is necessary for the induction of CSC marker expression and self-maintenance in breast cancer cells in response to matrix stiffness (57). Moreover, ILK expression was upregulated during EMT in colorectal and breast tumor CSCs, whereas ILK signaling inhibition reduced the expression of stem cell and EMT markers (58,59). The mechanism by which ILK signaling regulates CSC activities may become clearer when its signal transduction mechanisms are laid bare.

RhoA

The Ras homolog family member A (RhoA) is a small GTPase protein, with inactive GDP-bound, and active GTP bound conformational states. RhoA is strongly associated with signaling responses to extracellular stimuli. RhoA activity can be increased by soluble molecules binding to cell surface receptors, cell-cell adhesion, mechanical stimuli (60) and by cell attachment to ECMs, like fibronectin and hyaluronan (61,62). Like iother GTPases, RhoA activation is regulated by three classes of molecules: guanine-nucleotide-exchange factors (GEFs), GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs) and guanine nucleotide dissociation inhibitors (GDIs). GAPs and GEFs are responsible for nucleotide exchange-dependent activation and inhibition of RhoA. GDIs maintain a cytosolic pool of inactive RhoA.

RhoA activation by ECM goes through integrins, syndecans or CD44 receptors. Mechanical stimuli can go through these same receptors but are also mediated by cadherins and ion channels. Initial cell-adhesion to fibronectin decreases RhoA activity, while in later stages of cell spreading integrin heterodimer composition determines if RhoA is activated or inactivated (63). Integrin receptor organization and heterodimer composition has a significant role in regulation of RhoA signaling. Syndecan-4 clustering in the plasma membrane leads to PKCα-mediated RhoA activation (64). Hyaluronan binding to CD44 activates RhoA through GEFs (62). Mechanical stimuli unfold the rod-(R8)-domain of integrin to bind talin. Talin unfolding releases and inactivates DLC1, which then loses the ability to inactivate RhoA (30). Additionally, mechanical stimuli opens piezo2 ion channels and allows Ca2+ influx, which leads to Ca2+ activated calpain and tyrosine kinase-Fyn mediated RhoA activation (60). Active GTP bound-RhoA binds to and stimulates downstream signaling factors. One of the most dynamic RhoA signals is ROCK activation. ROCK directly increases phosphorylation of myosin and activates myosin contractility: which is required for cell migration.

RhoA is overexpressed in many cancers, however there are reports showing that RhoA can act as a tumor suppressor or promoter in different tunor types (65–68). RhoA is required for efficient cell adhesion and migration, since active RhoA induces maturation of focal adhesions and actin cytoskeleton function. RhoA activation is linked to activities that are important for cells in a CSC state, like proliferation (69) and EMT (70). However, RhoA inactivation can enhance Wnt-signaling and chemokine signaling in breast and colorectal tumor CSCs, and both promote tumor progression (65,67). There is a dearth of information that directly connects CSC states with

RhoA signaling, however we felt it was important to mention in this context because RhoA is a key point of integration for microenvironment mechanical and ECM signals.

Hippo pathway and YAP/TAZ

The hippo pathway in mammalian cells consists of core kinases (MST1/2 & LATS1/2), other kinase cascade factors, transcription coactivators (YAP & TAZ) and transcription factors (TEAD1–4) - altogether there are over 30 known components. Several soluble ligands, G-protein-coupled receptors, ECM, as well as mechanical stimuli regulate the hippo pathway (reviewed in (71)). When the hippo pathway is activated core kinases MST and LATS phosphorylate YAP and TAZ, which causes them to remain in the cytoplasm. Hippo pathway inactivation leads to YAP/TAZ dephosphorylation and translocation to the nucleus where they associate with TEADs and activate expression of gene programs relevant to cell survival, basal differentiation, and EMT-related processes. Many of the same receptors and signaling proteins that were discussed previously in this review are known also to interact with the hippo pathway, suggesting that the hippo pathway is a signaling integrator for CSC function.

The hippo pathway is responsive to multiple ECM and mechanical cues. Increased matrix stiffness inactivates the hippo pathway and YAP/TAZ expression levels themselves also are responsive to microenvironment stiffness (13). Differential ECM composition modulates hippo pathway activation, for example cell attachment to fibronectin and arginine rich ECMs inactivate the hippo pathway (71–73), whereas attachment to high molecular weight hyaluronan or laminin-111 activates the hippo pathway, inhibiting YAP and TAZ nuclear localization (74,75). Experiments that examined the role of laminins in YAP/TAZ activation also implicated integrins and CD44 as hippo control elements. Stiff or fibronectin-rich microenvironments inactivate LATS through β1-integrin (71). Laminin-511 through integrin α6Bβ1 triggered TAZ nuclear localization, whereas laminin-111 binding favored TAZ cytoplasmic localization, independent of LATS (75). High molecular weight hyaluronan drove CD44 clustering to activate hippo pathway, whereas low molecular weight hyaluronan cannot stimulate receptor clustering and this leads to inactivation of hippo pathway (74). Responses to mechanical stimuli or ECM signaling via FAK activates the Src-PI3K-PDK1 signaling cascade, which inhibits LATS phosphorylation (72). Compliant matrices inactivate RhoA through GAPs leading to LATS activation (76). Conversely, activated RhoA mediates LATS inactivation by binding angiomotin (AMOT), which together with NF2 is a LATS activator (77). ILK inhibits MST and LATS phosphorylation through inactivation of NF2 (78). Clustered CD44 receptors bind MST kinase inhibitor PAR1b and this leads to MST phosphorylation and hippo pathway activation, whereas non clustered CD44 receptors release PAR1b and this inhibits MST phosphorylation (74). Ridgid matrices increase vinculin association with the cytoskeleton triggering nuclear translocation of YAP and TAZ in a LATS independent manner (79). It is also possible that mechanical stimuli alone can trigger YAP/TAZ import into the nucleus by stretching actin and myosin fibers which flattens the nucleus and opens nuclear pores (71).

The hippo pathway may present another example of a dynamic and reciprocal relationship with the microenvironment that has specific implications for CSC regulation. While mechanical forces and ECM composition regulate hippo-pathway activation, the reverse also is known to happen. YAP/TAZ driven fibronectin and laminin-511 expression induced stiffening of the surrounding matrix. Laminin-511 and fibronectin-rich, stiff microenvironments then supported maintenance of CSCs (71,75). Further, YAP and TAZ together with TEADs promotes the transcription of multiple integrin and other focal adhesion-related genes (80) and in this way, establishes a dynamic and reciprocal cell-microenvironment sensing and modification circuit.

The hippo pathway is known for its role in modulating organ size by regulating cell proliferation, apoptosis, and stem cell self-maintenance -the pathway ostensibly exists to constrain growth (81). Inactivation of the hippo pathway, causing YAP and TAZ translocation to the nucleus, is related to enhanced expression of stem cell-related genes in CSCs (82,83). YAP and TAZ promote tumor spheroid growth in both in vitro and in vivo models (84–86) and facilitates resistance to anoikis in CSCs (87). The timing of hippo activation also may be a key consideration in CSC self-renewal because LATS1-mediated phosphorylation just before cell division was essential for tumorsphere formation in a mode of aggressive oral cancer (88). YAP mediated transcription caused de-differentiation of adult hepatocytes and resulted in accumulation of CSCs (89). Taken together, YAP and TAZ are transcriptional drivers of genes that are essential to the CSC state, which are regulated by microenvironmental signals that are both mechanical and biomolecular in nature. That YAP and TAZ are examples of transcription factors that are both regulated by and are producers of regulatory ECMs suggests these factors are key sculptors of the CSC niche microenvironments.

Conclusions

Physical and biochemical features of tumor microenvironments have a key role as managers of the CSC state. Here we reviewed several receptors and intracellular signaling agents that transduce and integrate mechanical and ECM-triggered signals and in this way, regulate CSC states. CSC and their progeny are thought to transit between different states (20), and perhaps the integration of mechanical and ECM signals determines the equilibrium of the states that are achieved. While dynamic signaling pathways integrate acute microenvironmental signals, probably equally important is the signal integration that happens at the epigenetic level. Epigenetic cell memory guides CSCs to adapt and survive in changing tumor microenvironments and may, for instance establish, the mechanical rheostats in CSCs that seem to be determined by the tissue of origin. It is not yet comprehensively studied, but shreds of evidence support the contention that microenvironment cues underlie epigenetic states (90).

There is a great challenge ahead to reveal how combinatorial and highly heterogeneous tumor microenvironments regulate CSC states. High throughput cell-based microenvironment assays (6,91) provide tools for addressing this challenge and by combining these assays with computational models (92) it may be possible to make in silico reconstructions of complex tissue microenvironments in order to more efficaciously establish testable hypotheses. If CSCs are indeed representative of a transient cell state, then therapeutic targeting of CSCs as entities will be extremely challenging. However, if the CSC state is regulated by specific microenvironment components then perhaps targeting the key integrators of microenvironment directives will lead to durable decreases in CSC activities.

Acknowledgments

Funding: We are grateful for support from our sponsors: CDMRP BCRP Era of Hope Award (BC141351) and associated expansion (BC181737), NIH (R01EB024989, U54HG008100), Conrad N. Hilton Foundation, and City of Hope Center for Cancer and Aging to ML.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

Tiina Jokela and Mark LaBarge declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

• Of importance

•• Of major importance

- 1.LaBarge MA. The difficulty of targeting cancer stem cell niches. Clin Cancer Res 2010. June 15;16(12):3121–3129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mora-Blanco EL, Lorens JB, Labarge MA. The tumor microenvironment as a transient niche: a modulator of epigenetic states and stem cell functions. In: Resende RR, Ulrich H, editors. Trends in Stem Cell Proliferation and Cancer Research. 1st ed. Dordrecht: Springer; 2013. p. 463–478. [Google Scholar]

- 3.dos Santos RV, da Silva LM. The noise and the KISS in the cancer stem cells niche. J Theor Biol 2013. 10/21;335:79–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Echeverria GV, Ge Z, Seth S, Zhang X, Jeter-Jones S, Zhou X, et al. Resistance to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in triple-negative breast cancer mediated by a reversible drug-tolerant state. Sci Transl Med 2019. April 17;11(488): 10.1126/scitranslmed.aav0936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shaffer SM, Dunagin MC, Torborg SR, Torre EA, Emert B, Krepler C, et al. Rare cell variability and drug-induced reprogramming as a mode of cancer drug resistance. Nature 2017. June 15;546(7658):431–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jokela TA, Engelsen AST, Rybicka A, Pelissier Vatter FA, Garbe JC, Miyano M, et al. Microenvironment-Induced Non-sporadic Expression of the AXL and cKIT Receptors Are Related to Epithelial Plasticity and Drug Resistance. Front Cell Dev Biol 2018. April 17;6:41.* Demonstrates that combinatorial microenvironment regulates CSC marker expression, which is correlated with tolerance to chemotherapeutics.

- 7.Lin CH, Jokela T, Gray J, LaBarge MA. Combinatorial Microenvironments Impose a Continuum of Cellular Responses to a Single Pathway-Targeted Anti-cancer Compound. Cell Rep 2017. October 10;21(2):533–545.** Demonstrates synergistic effects of mechanical forces and ECM-composition in imposing drug tolerant states in multiple cancer cell lines.

- 8.Senthebane DA, Rowe A, Thomford NE, Shipanga H, Munro D, Mazeedi MAMA, et al. The Role of Tumor Microenvironment in Chemoresistance: To Survive, Keep Your Enemies Closer. Int J Mol Sci 2017. July 21;18(7): 10.3390/ijms18071586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li Y, Fanous MJ, Kilian KA, Popescu G. Quantitative phase imaging reveals matrix stiffness-dependent growth and migration of cancer cells. Sci Rep 2019. January 22;9(1):248- 018-36551-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paszek MJ, Zahir N, Johnson KR, Lakins JN, Rozenberg GI, Gefen A, et al. Tensional homeostasis and the malignant phenotype. Cancer Cell 2005. September;8(3):241–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tian B, Luo Q, Ju Y, Song G. A Soft Matrix Enhances the Cancer Stem Cell Phenotype of HCC Cells. Int J Mol Sci 2019. June 10;20(11): 10.3390/ijms20112831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hui L, Zhang J, Ding X, Guo X, Jiang X. Matrix stiffness regulates the proliferation, stemness and chemoresistance of laryngeal squamous cancer cells. Int J Oncol 2017. April;50(4):1439–1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jabbari E, Sarvestani SK, Daneshian L, Moeinzadeh S. Optimum 3D Matrix Stiffness for Maintenance of Cancer Stem Cells Is Dependent on Tissue Origin of Cancer Cells. PLoS One 2015. July 13;10(7):e0132377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu Q, Xue Y, Liu J, Xi Z, Li Z, Liu Y. Fibronectin Promotes the Malignancy of Glioma Stem-Like Cells Via Modulation of Cell Adhesion, Differentiation, Proliferation and Chemoresistance. Front Mol Neurosci 2018. April 13;11:130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu X, Cai J, Zuo Z, Li J. Collagen facilitates the colorectal cancer stemness and metastasis through an integrin/PI3K/AKT/Snail signaling pathway. Biomed Pharmacother 2019. June; 114:108708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aoudjit F, Vuori K. Integrin signaling inhibits paclitaxel-induced apoptosis in breast cancer cells. Oncogene 2001. August 16;20(36):4995–5004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hyaluronic Acid Mediated Enrichment of CD44 Expressing Glioblastoma Stem Cells in U251MG Xenograft Mouse Model. J stem Cell Res Ther 2017. 7(384) 2 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sukowati CHC, Anfuso B, Fiore E, Ie SI, Raseni A, Vascotto F, et al. Hyaluronic acid inhibition by 4-methylumbelliferone reduces the expression of cancer stem cells markers during hepatocarcinogenesis. Sci Rep 2019. March 11;9(1):4026-019–40436-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hurt EM, Chan K, Serrat MA, Thomas SB, Veenstra TD, Farrar WL. Identification of vitronectin as an extrinsic inducer of cancer stem cell differentiation and tumor formation. Stem Cells 2010. March 31;28(3):390–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gupta PB, Chaffer CL, Weinberg RA. Cancer stem cells: mirage or reality? Nat Med 2009. 09/01;15(9):1010–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rice AJ, Cortes E, Lachowski D, Cheung BCH, Karim SA, Morton JP, et al. Matrix stiffness induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition and promotes chemoresistance in pancreatic cancer cells. Oncogenesis 2017. July 3;6(7):e352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wei SC, Fattet L, Tsai JH, Guo Y, Pai VH, Majeski HE, et al. Matrix stiffness drives epithelial-mesenchymal transition and tumour metastasis through a TWIST1-G3BP2 mechanotransduction pathway. Nat Cell Biol 2015. May;17(5):678–688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tzanakakis G, Kavasi RM, Voudouri K, Berdiaki A, Spyridaki I, Tsatsakis A, et al. Role of the extracellular matrix in cancer-associated epithelial to mesenchymal transition phenomenon. Dev Dyn 2018. March;247(3):368–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scott LE, Weinberg SH, Lemmon CA. Mechanochemical Signaling of the Extracellular Matrix in Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition. Front Cell Dev Biol 2019. July 19;7:135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Snyder V, Reed-Newman TC, Arnold L, Thomas SM, Anant S. Cancer Stem Cell Metabolism and Potential Therapeutic Targets. Front Oncol 2018. June 5;8:203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DelNero P, Hopkins BD, Cantley LC, Fischbach C. Cancer metabolism gets physical. Sci Transl Med 2018. May 23;10(442): 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaq1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park JS, Burckhardt CJ, Lazcano R, Solis LM, Isogai T, Li L, et al. Mechanical regulation of glycolysis via cytoskeleton architecture. Nature 2020. February;578(7796):621–626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seguin L, Desgrosellier JS, Weis SM, Cheresh DA. Integrins and cancer: regulators of cancer stemness, metastasis, and drug resistance. Trends Cell Biol 2015. April;25(4):234–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wei L, Yin F, Zhang W, Li L. STROBE-compliant integrin through focal adhesion involve in cancer stem cell and multidrug resistance of ovarian cancer. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017. March;96(12):e6345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haining AWM, Rahikainen R, Cortes E, Lachowski D, Rice A, von Essen M, et al. Mechanotransduction in talin through the interaction of the R8 domain with DLC1. PLoS Biol 2018. July 20;16(7):e2005599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goult BT, Yan J, Schwartz MA. Talin as a mechanosensitive signaling hub. J Cell Biol 2018. November 5;217(11):3776–3784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Changede R, Sheetz M. Integrin and cadherin clusters: A robust way to organize adhesions for cell mechanics. Bioessays 2017. January;39(1):1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ilmer M, Mazurek N, Byrd JC, Ramirez K, Hafley M, Alt E, et al. Cell surface galectin-3 defines a subset of chemoresistant gastrointestinal tumor-initiating cancer cells with heightened stem cell characteristics. Cell Death Dis 2016. August 11;7(8):e2337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ibrahim SA, Gadalla R, El-Ghonaimy EA, Samir O, Mohamed HT, Hassan H, et al. Syndecan-1 is a novel molecular marker for triple negative inflammatory breast cancer and modulates the cancer stem cell phenotype via the IL-6/STAT3, Notch and EGFR signaling pathways. Mol Cancer 2017. March 7;16(1):57–017-0621-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Elfenbein A, Simons M. Syndecan-4 signaling at a glance. J Cell Sci 2013. September 1;126(Pt 17):3799–3804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Voyvodic PL, Min D, Liu R, Williams E, Chitalia V, Dunn AK, et al. Loss of syndecan-1 induces a pro-inflammatory phenotype in endothelial cells with a dysregulated response to atheroprotective flow. J Biol Chem 2014. April 4;289(14):9547–9559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang H, Brown RL, Wei Y, Zhao P, Liu S, Liu X, et al. CD44 splice isoform switching determines breast cancer stem cell state. Genes Dev 2019. February 1;33(3–4):166–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wobus M, Rangwala R, Sheyn I, Hennigan R, Coila B, Lower EE, et al. CD44 associates with EGFR and erbB2 in metastasizing mammary carcinoma cells. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol 2002. March;10(1):34–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang SJ, Bourguignon LYW. Hyaluronan and the Interaction Between CD44 and Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor in Oncogenic Signaling and Chemotherapy Resistance in Head and Neck Cancer. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2006;132(7):771–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jokela T, Oikari S, Takabe P, Rilla K, Kärnä R, Tammi M, et al. Interleukin-1beta-induced Reduction of CD44 Ser-325 Phosphorylation in Human Epidermal Keratinocytes Promotes CD44 Homomeric Complexes, Binding to Ezrin, and Extended, Monocyte-adhesive Hyaluronan Coats. J Biol Chem 2015. May 8;290(19):12379–12393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Neisch AL, Fehon RG. Ezrin, Radixin and Moesin: key regulators of membrane-cortex interactions and signaling. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2011. August;23(4):377–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tai YL, Chen LC, Shen TL. Emerging roles of focal adhesion kinase in cancer. Biomed Res Int 2015;2015:690690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fujita Y, Kitagawa M, Nakamura S, Azuma K, Ishii G, Higashi M, et al. CD44 signaling through focal adhesion kinase and its anti-apoptotic effect. FEBS Lett 2002. September 25;528(1–3):101–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wilcox-Adelman SA, Denhez F, Goetinck PF. Syndecan-4 modulates focal adhesion kinase phosphorylation. J Biol Chem 2002. September 6;277(36):32970–32977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Seong J, Tajik A, Sun J, Guan JL, Humphries MJ, Craig SE, et al. Distinct biophysical mechanisms of focal adhesion kinase mechanoactivation by different extracellular matrix proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013. November 26;110(48):19372–19377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhou J, Aponte-Santamaria C, Sturm S, Bullerjahn JT, Bronowska A, Grater F. Mechanism of Focal Adhesion Kinase Mechanosensing. PLoS Comput Biol 2015. November 6;11(11):e1004593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Calalb MB, Polte TR, Hanks SK. Tyrosine phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase at sites in the catalytic domain regulates kinase activity: a role for Src family kinases. Mol Cell Biol 1995. February;15(2):954–963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Luo M, Fan H, Nagy T, Wei H, Wang C, Liu S, et al. Mammary epithelial-specific ablation of the focal adhesion kinase suppresses mammary tumorigenesis by affecting mammary cancer stem/progenitor cells. Cancer Res 2009. January 15;69(2):466–474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Begum A, Ewachiw T, Jung C, Huang A, Norberg KJ, Marchionni L, et al. The extracellular matrix and focal adhesion kinase signaling regulate cancer stem cell function in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. PLoS One 2017. July 10;12(7):e0180181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cicchini C, Laudadio I, Citarella F, Corazzari M, Steindler C, Conigliaro A, et al. TGFbeta-induced EMT requires focal adhesion kinase (FAK) signaling. Exp Cell Res 2008. January 1;314(1):143–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guan JL. Integrin signaling through FAK in the regulation of mammary stem cells and breast cancer. IUBMB Life 2010. April;62(4):268–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Widmaier M, Rognoni E, Radovanac K, Azar SB, Fassler R. Integrin-linked kinase at a glance. J Cell Sci 2012. April 15;125(Pt 8):1839–1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kunschmann T, Puder S, Fischer T, Perez J, Wilharm N, Mierke CT. Integrin-linked kinase regulates cellular mechanics facilitating the motility in 3D extracellular matrices. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res 2017. March;1864(3):580–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Traister A, Li M, Aafaqi S, Lu M, Arab S, Radisic M, et al. Integrin-linked kinase mediates force transduction in cardiomyocytes by modulating SERCA2a/PLN function. Nat Commun 2014. September 11;5:4533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kimura M, Murakami T, Kizaka-Kondoh S, Itoh M, Yamamoto K, Hojo Y, et al. Functional molecular imaging of ILK-mediated Akt/PKB signaling cascades and the associated role of beta-parvin. J Cell Sci 2010. March 1;123(Pt 5):747–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Eke I, Koch U, Hehlgans S, Sandfort V, Stanchi F, Zips D, et al. PINCH1 regulates Akt1 activation and enhances radioresistance by inhibiting PP1alpha. J Clin Invest 2010. July;120(7):2516–2527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pang MF, Siedlik MJ, Han S, Stallings-Mann M, Radisky DC, Nelson CM. Tissue Stiffness and Hypoxia Modulate the Integrin-Linked Kinase ILK to Control Breast Cancer Stem-like Cells. Cancer Res 2016. September 15;76(18):5277–5287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tsoumas D, Nikou S, Giannopoulou E, Champeris Tsaniras S, Sirinian C, Maroulis I, et al. ILK Expression in Colorectal Cancer Is Associated with EMT, Cancer Stem Cell Markers and Chemoresistance. Cancer Genomics Proteomics 2018. Mar-Apr;15(2):127–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shibue T, Brooks MW, Weinberg RA. An integrin-linked machinery of cytoskeletal regulation that enables experimental tumor initiation and metastatic colonization. Cancer Cell 2013. October 14;24(4):481–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pardo-Pastor C, Rubio-Moscardo F, Vogel-Gonzalez M, Serra SA, Afthinos A, Mrkonjic S, et al. Piezo2 channel regulates RhoA and actin cytoskeleton to promote cell mechanobiological responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018. February 20;115(8):1925–1930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li Y, Chen Y, Tao Y, Wang Y, Chen Y, Xu W. Fibronectin increases RhoA activity through inhibition of PKA in the human gastric cancer cell line SGC-7901. Mol Med Rep 2011. Jan-Feb;4(1):65–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bourguignon LY. Hyaluronan-mediated CD44 activation of RhoGTPase signaling and cytoskeleton function promotes tumor progression. Semin Cancer Biol 2008. August;18(4):251–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Danen EH, Sonneveld P, Brakebusch C, Fassler R, Sonnenberg A. The fibronectin-binding integrins alpha5beta1 and alphavbeta3 differentially modulate RhoA-GTP loading, organization of cell matrix adhesions, and fibronectin fibrillogenesis. J Cell Biol 2002. December 23;159(6):1071–1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dovas A, Yoneda A, Couchman JR. PKCbeta-dependent activation of RhoA by syndecan-4 during focal adhesion formation. J Cell Sci 2006. July 1;119(Pt 13):2837–2846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kalpana G, Figy C, Yeung M, Yeung KC. Reduced RhoA expression enhances breast cancer metastasis with a concomitant increase in CCR5 and CXCR4 chemokines signaling. Sci Rep 2019. November 8;9(1):16351–019-52746-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bellizzi A, Mangia A, Chiriatti A, Petroni S, Quaranta M, Schittulli F, et al. RhoA protein expression in primary breast cancers and matched lymphocytes is associated with progression of the disease. Int J Mol Med 2008. July;22(1):25–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rodrigues P, Macaya I, Bazzocco S, Mazzolini R, Andretta E, Dopeso H, et al. RHOA inactivation enhances Wnt signalling and promotes colorectal cancer. Nat Commun 2014. November 21;5:5458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang HB, Liu XP, Liang J, Yang K, Sui AH, Liu YJ. Expression of RhoA and RhoC in colorectal carcinoma and its relations with clinicopathological parameters. Clin Chem Lab Med 2009;47(7):811–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jeong D, Park S, Kim H, Kim CJ, Ahn TS, Bae SB, et al. RhoA is associated with invasion and poor prognosis in colorectal cancer. Int J Oncol 2016. February;48(2):714–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wang Q, Yang X, Xu Y, Shen Z, Cheng H, Cheng F, et al. RhoA/Rho-kinase triggers epithelial-mesenchymal transition in mesothelial cells and contributes to the pathogenesis of dialysis-related peritoneal fibrosis. Oncotarget 2018. January 12;9(18):14397–14412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dobrokhotov O, Samsonov M, Sokabe M, Hirata H. Mechanoregulation and pathology of YAP/TAZ via Hippo and non-Hippo mechanisms. Clin Transl Med 2018. August 13;7(1):23–018-0202–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kim NG, Gumbiner BM. Adhesion to fibronectin regulates Hippo signaling via the FAK-Src-PI3K pathway. J Cell Biol 2015. August 3;210(3):503–515.* Shows that ECM composition regulates hippo pathway, which is also an important mechanoresponsive signaling pathway.

- 73.Chakraborty S, Hong W. Linking Extracellular Matrix Agrin to the Hippo Pathway in Liver Cancer and Beyond. Cancers (Basel) 2018. February 6;10(2): 10.3390/cancers10020045.* Shows that ECM composition regulates hippo pathway, which is also an important mechanoresponsive signaling pathway.

- 74.Ooki T, Murata-Kamiya N, Takahashi-Kanemitsu A, Wu W, Hatakeyama M. High-Molecular-Weight Hyaluronan Is a Hippo Pathway Ligand Directing Cell Density-Dependent Growth Inhibition via PAR1b. Dev Cell 2019. May 20;49(4):590–604.e9.* Shows that ECM composition regulates hippo pathway, which is also an important mechanoresponsive signaling pathway.

- 75.Chang C, Goel HL, Gao H, Pursell B, Shultz LD, Greiner DL, et al. A laminin 511 matrix is regulated by TAZ and functions as the ligand for the alpha6Bbeta1 integrin to sustain breast cancer stem cells. Genes Dev 2015. January 1;29(1):1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rausch V, Hansen CG. The Hippo Pathway, YAP/TAZ, and the Plasma Membrane. Trends Cell Biol 2020. January;30(1):32–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shi X, Yin Z, Ling B, Wang L, Liu C, Ruan X, et al. Rho differentially regulates the Hippo pathway by modulating the interaction between Amot and Nf2 in the blastocyst. Development 2017. November 1;144(21):3957–3967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Serrano I, McDonald PC, Lock F, Muller WJ, Dedhar S. Inactivation of the Hippo tumour suppressor pathway by integrin-linked kinase. Nat Commun 2013;4:2976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kuroda M, Wada H, Kimura Y, Ueda K, Kioka N. Vinculin promotes nuclear localization of TAZ to inhibit ECM stiffness-dependent differentiation into adipocytes. J Cell Sci 2017. March 1;130(5):989–1002.** Demonstrates that the ECM molecule vinculin inhibits mechanical force imposed cell differentiation; anexample of signaling integration.

- 80.Nardone G, Oliver-De La Cruz J, Vrbsky J, Martini C, Pribyl J, Skladal P, et al. YAP regulates cell mechanics by controlling focal adhesion assembly. Nat Commun 2017. May 15;8:15321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Aragona M, Panciera T, Manfrin A, Giulitti S, Michielin F, Elvassore N, et al. A mechanical checkpoint controls multicellular growth through YAP/TAZ regulation by actin-processing factors. Cell 2013. August 29;154(5):1047–1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Park JH, Shin JE, Park HW. The Role of Hippo Pathway in Cancer Stem Cell Biology. Mol Cells 2018. February 28;41(2):83–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hao J, Zhang Y, Jing D, Li Y, Li J, Zhao Z. Role of Hippo signaling in cancer stem cells. J Cell Physiol 2014. March;229(3):266–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Paquet-Fifield S, Koh SL, Cheng L, Beyit LM, Shembrey C, Molck C, et al. Tight Junction Protein Claudin-2 Promotes Self-Renewal of Human Colorectal Cancer Stem-like Cells. Cancer Res 2018. June 1;78(11):2925–2938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lei QY, Zhang H, Zhao B, Zha ZY, Bai F, Pei XH, et al. TAZ promotes cell proliferation and epithelial-mesenchymal transition and is inhibited by the hippo pathway. Mol Cell Biol 2008. April;28(7):2426–2436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Li J, Li Z, Wu Y, Wang Y, Wang D, Zhang W, et al. The Hippo effector TAZ promotes cancer stemness by transcriptional activation of SOX2 in head neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cell Death Dis 2019. August 9;10(8):603–019-1838–0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sugiura K, Mishima T, Takano S, Yoshitomi H, Furukawa K, Takayashiki T, et al. The Expression of Yes-Associated Protein (YAP) Maintains Putative Cancer Stemness and Is Associated with Poor Prognosis in Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma. Am J Pathol 2019. September;189(9):1863–1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Nozaki M, Yabuta N, Fukuzawa M, Mukai S, Okamoto A, Sasakura T, et al. LATS1/2 kinases trigger self-renewal of cancer stem cells in aggressive oral cancer. Oncotarget 2019. February 1;10(10):1014–1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yimlamai D, Christodoulou C, Galli GG, Yanger K, Pepe-Mooney B, Gurung B, et al. Hippo pathway activity influences liver cell fate. Cell 2014. June 5;157(6):1324–1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Crowder SW, Leonardo V, Whittaker T, Papathanasiou P, Stevens MM. Material Cues as Potent Regulators of Epigenetics and Stem Cell Function. Cell Stem Cell 2016. January 7;18(1):39–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ranga A, Gobaa S, Okawa Y, Mosiewicz K, Negro A, Lutolf MP. 3D niche microarrays for systems-level analyses of cell fate. Nat Commun 2014. July 14;5:4324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sun M, Spill F, Zaman MH. A Computational Model of YAP/TAZ Mechanosensing. Biophys J 2016. June 7;110(11):2540–2550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]