Abstract

Complex multicellular life in mammals relies on functional cooperation of different organs for the survival of the whole organism. The kidneys play a critical part in this process through the maintenance of fluid volume and composition homeostasis, which enables other organs to fulfil their tasks. The renal endothelium exhibits phenotypic and molecular traits that distinguish it from endothelia of other organs. Moreover, the adult kidney vasculature comprises diverse populations of mostly quiescent, but not metabolically inactive, endothelial cells (ECs) that reside within the kidney glomeruli, cortex and medulla. Each of these populations supports specific functions, for example, in the filtration of blood plasma, the reabsorption and secretion of water and solutes, and the concentration of urine. Transcriptional profiling of these diverse EC populations suggests they have adapted to local microenvironmental conditions (hypoxia, shear stress, hyperosmolarity), enabling them to support kidney functions. Exposure of ECs to microenvironment-derived angiogenic factors affects their metabolism, and sustains kidney development and homeostasis, whereas EC-derived angiocrine factors preserve distinct microenvironment niches. In the context of kidney disease, renal ECs show alteration in their metabolism and phenotype in response to pathological changes in the local microenvironment, further promoting kidney dysfunction. Understanding the diversity and specialization of kidney ECs could provide new avenues for the treatment of kidney diseases and kidney regeneration.

Subject terms: Kidney, Circulation, Kidney, Kidney, Metabolism

The adult kidney vasculature comprises diverse populations of endothelial cells that support specific functions according to their microenvironment. This Review summarizes our current understanding of the phenotypic, molecular and metabolic heterogeneity of renal endothelial cells in relation to their microenvironment and the potential application of targeting renal endothelial cell metabolism as a therapeutic strategy for kidney diseases or kidney regeneration.

Key points

The endothelium differs between different organs, probably to support distinct organ functions.

Multiple specialized endothelial cell phenotypes coexist within the renal glomeruli, cortex and medulla; these function to support glomerular filtration, the reabsorption and secretion of ions and metabolites, and urine concentration.

The different local microenvironments in the kidney shape the molecular and metabolic heterogeneity of the renal endothelium; conversely, endothelial cell-derived angiocrine factors sustain the niches of different kidney microenvironments.

The metabolism of renal endothelial cells can be altered in the context of kidney injury and diseases, partly as a result of changes in the microenvironment.

Greater understanding of the phenotypic diversity and metabolic specialization of renal endothelial cells may aid identification of new targets for the treatment of kidney diseases and kidney regeneration.

Introduction

The mammalian vascular system consists of two connected and highly branched networks that pervade the whole body — each with specific roles. The blood vascular system delivers oxygen and nutrients to parenchymal tissues, and facilitates waste removal, immune surveillance and immune cell trafficking, coagulation, and the production of angiocrine signals for tissue maintenance and regeneration1. By contrast, the lymphatic vascular system drains the extravasated interstitial fluid from permeable blood capillaries back to the veins, and facilitates immune cell trafficking and lipid transport2. All blood vessels are lined with blood endothelial cells (BECs, referred to as ECs hereafter), whereas lymphatic endothelial cells (LECs) form the innermost layer of lymphatic vessels — with each population supporting its vasculature-specific tasks. However, endothelial heterogeneity extends far beyond the broad differences between blood and lymphatic endothelium. In particular, ECs from different organs exhibit unique molecular profiles that support the specific functions of the organ3–6. The kidney benefits from a highly specialized vasculature, which is tightly linked to the kidney epithelial system7. Specifically, phenotypically distinct populations of renal endothelial cells (RECs) coexist within the three anatomical and functional compartments of the kidney, the glomeruli, cortex and medulla — where they support specific kidney tasks8,9. Importantly, technological advances have enabled the study of REC heterogeneity at the single-cell level, providing new insights into their specialized roles in kidney health and disease6,10,11.

The kidney is critical for the maintenance of organismal homeostasis, regulating the volume and composition of body fluids7. Kidneys receive 20–25% of cardiac output and exhibit a stereotypic blood vessel architecture. This architecture not only enables the delivery of oxygen and nutrients to the kidneys, but also enables participation in the filtration of blood plasma, the reabsorption of ions and metabolites from the filtrate, the secretion of ions and metabolites in the primary urine, and urine concentration7,8. These highly orchestrated processes enable fine-tuning of extracellular fluid volume, blood pressure, osmolality and ion concentration7,8. The kidneys also regulate circulating metabolite levels, not only by excreting metabolic waste, but also by releasing glucose (via gluconeogenesis) and amino acids, for example12. Mammalian organs continually exchange metabolites via the circulation, with selective usage to support their own metabolic activities12. Accordingly, the metabolic functions of ECs within different organs probably demonstrate organ-specific differences, as supported by findings from metabolic transcriptome analyses of ECs in different organs6. Furthermore, the metabolic plasticity of ECs allows them to adapt and respond to environmental changes with respect to their metabolic needs and functions3,13. Emerging evidence suggests that the specialized RECs of the kidney tailor their metabolic transcriptome to support kidney function10.

REC dysfunction accompanies the acute or progressive loss of kidney function14,15. This dysfunction is associated with an increase in arterial vasoconstriction and a reduction in renal blood flow, the acquisition of pro-inflammatory and pro-thrombotic phenotypes that favour immune cell adhesion and infiltration and the formation of microthrombi, the dissociation of mural pericytes from the endothelial layer, breakdown of the endothelial barrier resulting in interstitial oedema, rarefaction of peritubular capillaries (thereby promoting kidney hypoxia), and endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition, which contributes to kidney fibrosis16,17, suggesting that the endothelium could be targeted to protect against kidney injury and/or to regenerate kidney function.

This Review summarizes our current understanding of the kidney vasculature, focusing on recent advances in our understanding of the phenotypic, molecular and metabolic heterogeneity of RECs in relation to their microenvironment. We also discuss the potential application of targeting REC metabolism as a therapeutic strategy in kidney diseases or for kidney regeneration.

Renal endothelium heterogeneity

Renal vascular anatomy

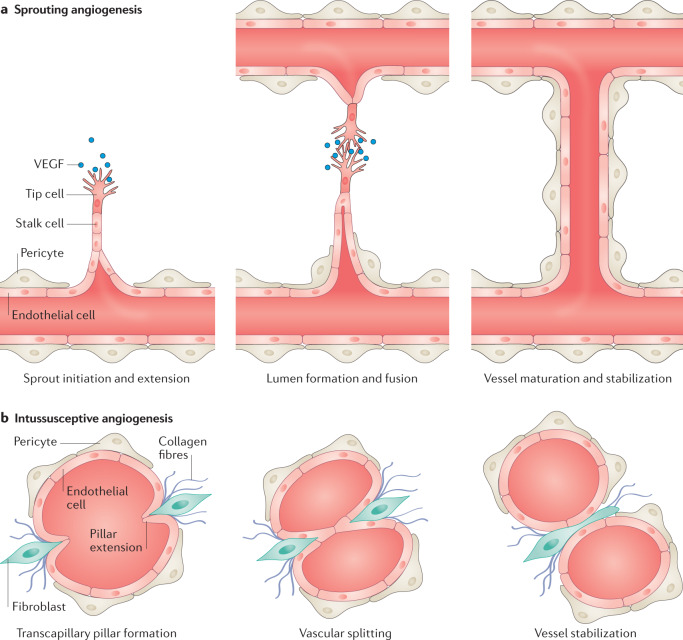

The kidney is supplied with blood via the renal artery, which after entering the kidney via the renal hilum, branches into segmental, interlobar, arcuate and interlobular arteries (Fig. 1a), and ultimately, afferent arterioles, which are high-resistance vessels responsible for the control of the glomerular blood flow and glomerular filtration rate (GFR)18. From the afferent arterioles the blood enters the glomerular tuft — a network of highly fenestrated glomerular capillaries where ultrafiltration of blood plasma occurs at a rate of ~120–140 ml/min in adult humans, enabling low molecular weight solutes to pass from the glomerular capillaries to the Bowman’s space19. After a fraction of the plasma has been filtered, blood leaves the glomerular tuft through efferent arterioles to vascularize the distal and proximal convoluted tubules, forming the cortical peritubular capillary network. Blood within the peritubular capillaries is enriched with high molecular weight solutes and has a low fluid content owing to the loss of fluid during glomerular ultrafiltration. Thus, peritubular capillaries are dedicated to the reabsorption of water, ions and essential nutrients from the proximal7,20 and distal tubules21. Several ions such as H+ (ref.22) and K+ (ref.23) as well as molecules such as creatinine24 and drug metabolites25 — which were not completely filtered by the glomerular capillaries but still need to be eliminated from the body — move from the peritubular capillaries into the epithelial cells of the proximal20 or distal tubules to be secreted and eliminated in the urine21. The efferent arterioles from the juxtamedullary nephrons give rise to the descending vasa recta (DVR), which interconnects with the ascending vasa recta (AVR) through capillary plexuses. The AVR and DVR run countercurrent to the loop of Henle, and participate in medullary countercurrent exchange, which as described later, is necessary to maintain an osmolarity gradient for urine concentration26. Eventually, the cortical and medullary capillary systems together with the AVR coalesce into a venous system at the corticomedullary junction. More specifically, the renal venous vasculature drains the blood from the peritubular capillaries and AVR into the interlobular and arcuate veins and then interlobar veins, ultimately forming the renal vein that emerges from the kidney hilum and finally branches into the inferior vena cava7.

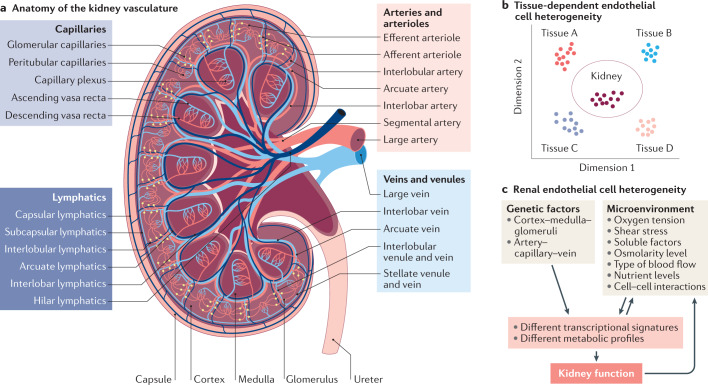

Fig. 1. Anatomy and heterogeneity of the kidney vasculature.

a | The human kidney contains a highly specialized vasculature that is closely linked to the kidney epithelial system. The blood vascular system delivers oxygen and nutrients to parenchymal tissues, and facilitates waste removal, immune surveillance and immune cell trafficking, coagulation, and the production of angiocrine signals for tissue maintenance and regeneration, whereas the lymphatic vascular system drains the extravasated interstitial fluid from permeable blood capillaries back to the veins, and facilitates immune cell trafficking and lipid transport. b | Endothelial cells (ECs) are characterized by their tissue-specific transcriptional heterogeneity. The plot shows a representative dimensionality reduction of the transcriptome profiles of ECs isolated from kidney and four other hypothetical tissues or organs. c | EC heterogeneity within the kidney is dictated by a combination of genetic factors and exposure to different microenvironments, which ultimately contribute to kidney function.

The kidney is also supplied by lymphatic vessels, which follow the overall topography of the kidney blood vasculature27 (Fig. 1a). They are mainly present in the kidney cortex where their primary role is to remove fluid and macromolecules (such as albumin) from the interstitial space between the tubules and capillaries28. They also have a role in the infiltration of immune cells and subsequent inflammation29. In the glomeruli, they surround the Bowman’s capsule without penetrating into the glomerular tuft28. By contrast, traditional lymphatic vessels are rarely present in the kidney medulla; in this region, interstitial fluid and macromolecules are removed by the AVR, which represents a type of hybrid blood vessel with lymphatic-like features28,30.

Renal endothelial cell phenotypes

ECs from different organs are phenotypically heterogeneous3–6,31. The unique properties of RECs, and in particular glomerular ECs, have long been appreciated. Global transcriptional profiling of ECs from mice has confirmed the existence of organ-specific transcriptome signatures3,4,6. Of note, these studies have demonstrated that RECs are the most dissimilar to ECs from other organs including the brain, heart, lung, muscle and testis4 (Fig. 1b) through their expression of genes associated with interferon signalling, as well as genes that encode the angiocrine factors FGF1 and IL-33 (refs4,6). The organ-specific heterogeneity of ECs probably underlies their molecular adaptation to fulfil specific functional roles3–6,31.

However, the heterogeneity of RECs extends beyond the organotypic level, with remarkable diversity of the kidney vasculature, as demonstrated initially by electron microscopy and microarray studies and subsequently by single-cell analyses6,32,33. The kidney cortex, glomeruli and medulla contain unique EC populations (cRECs, gRECs and mRECs, respectively). This diversity in EC populations might arise from exposure to the different microenvironments of these regions. For example, the glomerular endothelium is exposed to a high vascular pressure and interacts tightly with podocytes to regulate ultrafiltration, whereas mRECs are exposed to high osmolarity and hypoxia, which are related to the maintenance of an osmolarity gradient and urine concentration6,9,10,32 (Fig. 1c).

Beyond inter-compartmental heterogeneity, RECs also demonstrate intra-compartmental heterogeneity, which is probably determined by a number of genetic and environmental factors, including the type of vascular bed (arterial, capillary, venous), their interactions with other cell types (for example, smooth muscle cells, pericytes, granular cells, podocytes and tubule epithelial cells) and their exposure to different microenvironments within the same compartment, such as exposure to different types of flow or different levels of osmolarity34 (Fig. 1c). Developments in single-cell transcriptomics technologies have enabled the heterogeneity of mouse RECs to be mapped at very high resolution6,10,11, revealing up to 24 transcriptionally different REC populations6,10,11. Of note, the findings from single-cell RNA-seq studies summarized below remain to be confirmed at the protein level, both to comprehensively verify the spatial localization of the predicted proteins and also to integrate knowledge of the post-translational changes and/or signalling mechanisms that may affect protein activity. Also of note is the fact that the relative enrichment of a gene within a particular REC population as determined by single-cell sequencing does not necessarily imply that the expression of that gene is restricted to that specific cell population.

Heterogeneity of glomerular renal endothelial cells

The kidney glomerulus is a highly specialized structure that is responsible for the filtration of blood plasma to generate a primary urine filtrate while ensuring that essential plasma proteins are retained in the blood. It is composed of glomerular capillaries that lie between afferent and efferent arterioles, which are resistance vessels that control both capillary blood flow and pressure. The arterioles of a nephron are in partial contact with the juxtaglomerular apparatus (JGA) — a specialized structure that comprises the macula densa of the distal convoluted tubule, granular renin-producing cells that are associated with the afferent arteriole and extraglomerular mesangial cells (Fig. 2a). The JGA regulates single-nephron GFR and blood pressure through the tubuloglomerular feedback, the myogenic response and the release of renin19,35–37.

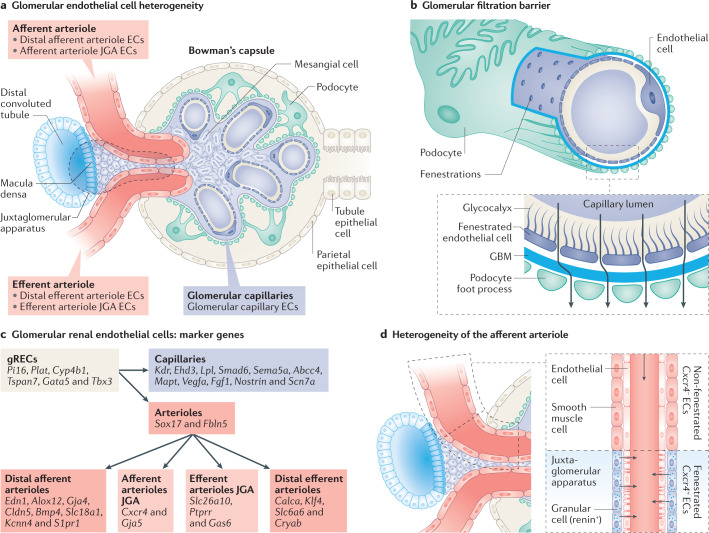

Fig. 2. Phenotypic and molecular heterogeneity of the glomerular endothelium.

a | The glomerular vasculature comprises the glomerular capillaries connected to the afferent and efferent arterioles. The arterioles are in partial contact with the juxtaglomerular apparatus (JGA), which comprises the macula densa of the distal convoluted tubule, granular renin-producing cells and extraglomerular mesangial cells. b | The glomerular filtration barrier is composed of glomerular capillary endothelial cells (ECs) and podocytes, separated by a glomerular basement membrane (GBM). The glomerular capillary endothelium encompasses non-diaphragmed fenestrations and a thick glycocalyx, which sustain glomerular filtration and permselectivity. c | The heterogeneity of glomerular renal ECs (gRECs) is demonstrated by the differential expression of genes by different gREC types. Pink and purple reflect arteriole and capillary EC phenotypes, respectively. Since REC subpopulations express a combination of several markers, these are indicated following a hierarchical system. More detailed information can be found in Supplementary Table 1. d | The layer of vascular smooth muscle cells from the afferent arteriole is progressively replaced by renin-expressing granular cells within the JGA at the entrance of the glomerular tuft. A switch from a non-fenestrated and Cxcr4-negative endothelium to a fenestrated and Cxcr4-positive endothelium within the JGA is also observed.

The glomerular capillary endothelium is composed of unique ECs with non-diaphragmed fenestrations that allow the filtration of high volumes of fluid38 (Fig. 2b). The fenestrations are 50–100 nm in size and occupy around 20% of the cell surface area, appearing on electron microscopic imaging as trans-cellular holes38. The diameter of these fenestrations is theoretically large enough to allow the passage of fluid and large proteins into the tubules. However, capillary gRECs also produce a thick layer of glycocalyx comprising negatively charged glycoproteins and polysaccharides that act as a barrier to protein passage39,40. Moreover, plasma components are adsorbed in the glycocalyx and form a broader coat called the endothelial surface layer41, which with its filamentous structure further enhances the permselectivity of the glomerular endothelial barrier42. Indeed, albuminuria and proteinuria are observed upon glycocalyx impairment39,43,44. Together with podocytes, capillary gRECs also synthesize and share a common extracellular matrix known as the glomerular basement membrane (GBM), which comprises mainly collagen type IV, laminin and sulfated proteoglycans42. Mutations affecting the synthesis of any of the components of the GBM lead to proteinuria45,46. Thus, capillary gRECs, podocytes and the GBM form an efficient glomerular filtration barrier. Of note, the glomerular capillary endothelium lacks a diaphragm and therefore does not express the type II transmembrane glycoprotein plasmalemma vesicle-associated protein 1 (PV1), which is encoded by Plvap10 and is a typical marker of fenestrated ECs associated with the bridging diaphragms of endothelial fenestrae and caveolae47.

The development and maintenance of the capillary gREC fenestrations require podocyte-derived vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which acts in a paracrine manner through endothelial VEGF receptor 2 (VEGFR2, also known as KDR)48. Overexpression of VEGF causes glomerular collapse, rapid loss of capillary gRECs and massive proteinuria49. Thus, tight regulation of podocyte VEGF is needed to establish the glomerular vasculature during embryonic development, and for the maintenance of fenestrations in mature glomerular capillaries38,42. Similarly, tubular epithelial cell-derived VEGF allows maintenance of the peritubular capillary network50.

Unlike other capillary ECs, gRECs are exposed to a high blood pressure and high blood flow, which drives the glomerular filtration process and exposes gRECs to substantial shear stress51. Accordingly, gRECs express high levels of the shear stress-regulated transcript Pi16 (refs6,10,11,52) (Fig. 2c; Supplementary Table 1). Capillary gRECs also express a number of other markers10,11,32,53, including Ehd3, which encodes a member of the EHD protein family10,11,38,54,55 that regulates endocytic recycling and is thought to regulate the recycling of VEGFR2 in capillary gRECs (Fig. 2c), together with EHD4 (ref.54). Thus, EHD3 might contribute to the maintenance of glomerular capillary fenestrations. Capillary gRECs also show enriched expression of genes associated with the TGFβ–BMP signalling pathway (Eng, Smad6, Smad7, Xiap and Hipk2 (refs10,56–58)), which is involved in glomerular capillary formation. Overexpression of TGFβ induces proteinuria and glomerulosclerosis59, and thus the presence of inhibitory SMADs, such as those encoded by Smad6 and Smad7 in gRECs may prevent excessive TGFβ signalling and glomerular dysfunction. By contrast, podocyte-derived BMP is crucial for normal glomerular capillary formation60. Capillary gRECs also specifically express Nostrin32, the protein product of which binds endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) to trigger its translocation from the plasma membrane to vesicle-like subcellular structures, and attenuates the production of nitric oxide (NO) — an important regulator of GFR32. Moreover, the restricted expression of lipoprotein lipase (Lpl) to capillary gRECs suggests that the glomerular endothelium may be essential for the release of fatty acids into the ultrafiltrate, which could subsequently be used as an energy source by tubule epithelial cells or for the regulation of blood lipid content, or could contribute to the accumulation of glomerular lipids as observed in pathological contexts6,10,61,62. Interestingly, renal expression of genes involved in lipid metabolism correlates with GFR and inflammation in patients with diabetic kidney disease, whereas defective fatty acid oxidation (FAO) in tubular cells contributes to the development of kidney fibrosis61,62.

Transcription factors, such as SOX17 and COUP-TFII (encoded by Nr2f2) in arterial and venous RECs, respectively, drive transcriptomic signatures and the identity of specific vascular beds63,64. The identity of gRECs relies on the activity of at least two transcription factors: GATA5 and TBX3 (refs10,11,32) (Fig. 2c), which mediate the acquisition of a gREC-like gene expression profile when overexpressed together in human umbilical vein ECs (HUVECs), a commonly used EC model11. The GATA5 regulon is upregulated in gRECs but not in other REC populations10,11 and selective deletion of Gata5 in ECs causes glomerular lesions65. Moreover, EC-specific deletion of Tbx3 causes morphogenic defects such as microaneurysms in subsets of glomeruli, reduced numbers of capillary gREC fenestrations and deformed podocyte foot processes, suggesting a role for this transcription factor in maintaining the structural organization of glomerular capillaries11. In addition, both GATA5 and TBX3 are involved in the regulation of blood pressure. GATA5 affects typical vascular function, protein kinase A and NO signalling pathways65, whereas TBX3 is thought to modulate blood pressure via the regulation of renin secretion in the kidney11.

Regulation of the vascular tone of afferent and efferent arterioles is required to maintain the constantly high glomerular capillary pressure needed for glomerular filtration18. This regulatory process enables a constant GFR to be maintained despite changes in systemic pressure and cardiac output66. Afferent arterioles have one to three layers of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs), which, in proximity to the JGA, are partially replaced by renin-producing granular cells67 (Fig. 2d). EC heterogeneity also exists within the afferent arteriole, with non-diaphragmed fenestrations of the endothelium nearest to the JGA68,69 — similar to that of the glomerular capillary endothelium — probably to facilitate the rapid transport of renin into the blood18 (Fig. 2d). Expression of Gja5 (encoding connexin 40), is enriched in this subset of gRECs10,70, and has an important role in communication between the endothelium and granular cells in the JGA to regulate renin release35,70,71. These ECs are also enriched in other genes involved in cell-to-cell interaction, such as those related to the Wnt and Notch signalling pathways, Ephrin and cytokines and chemokines (Fig. 2c), which might mediate crosstalk between mesangial cells and/or granular cells and gRECs in the JGA, and potentially contribute to autoregulation and blood pressure modulation10.

By contrast, gRECs in the upstream (most distal) part of the afferent arterioles express genes involved in vasotone regulation such as Edn1 (which encodes endothelin 1), Alox12 (arachidonate 12-lipoxygenase) and S1pr1 (sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1)10,72,73 (Fig. 2c). The S1P–S1PR1 signalling pathway potently regulates afferent arteriole vasotone by activating the eNOS system74–76. In line with this role, the S1P receptor is enriched in gRECs in the afferent arterioles and is not detected in efferent arterioles10.

In contrast to gRECs in the afferent arterioles, gRECs in the efferent arterioles show lower connexin expression77, especially connexin 37 and connexin 40 (encoded by Gja4 and Gja5, respectively)10. Similar to ECs from the afferent arterioles, however, transcriptome analyses of ECs from the efferent arterioles indicate the presence of two gREC populations: one presumably associated with the JGA (expressing genes associated with immune cell adhesion and extravasation, and EC permeability) and a second that corresponds to the distal portion of the efferent arteriole (enriched in genes involved in hyperosmolarity responses)10 (Fig. 2c).

These insights suggest that the phenotypic and functional diversity of gRECs underlies the ability of these endothelia to maintain GFR through the active modulation of glomerular blood flow and by ensuring glomerular filtration efficiency. Through the integration of tubuloglomerular feedback and myogenic signals, gRECs associated with the JGA in particular are probably critical regulators of GFR.

Heterogeneity of cortical renal endothelial cells

In addition to the glomerular capillary endothelium and the pre-glomerular and post-glomerular afferent and efferent arterioles, the kidney cortex contains lymphatic vessels, and large arteries and veins together with their associated vasa vasora, postcapillary venules and peritubular capillaries. In line with their role in the reabsorption and secretion of solutes, ions and water, cortical peritubular capillaries are thin-walled capillaries comprising ECs that are functionally coupled to the tubular epithelium9 (Fig. 3a). Compared with gRECs and mRECs, cRECs — in particular peritubular capillary ECs — express high levels of Igfbp3 (encoding insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 3), and Npr3 (encoding natriuretic peptide receptor 3)10,11 (Fig. 3b).

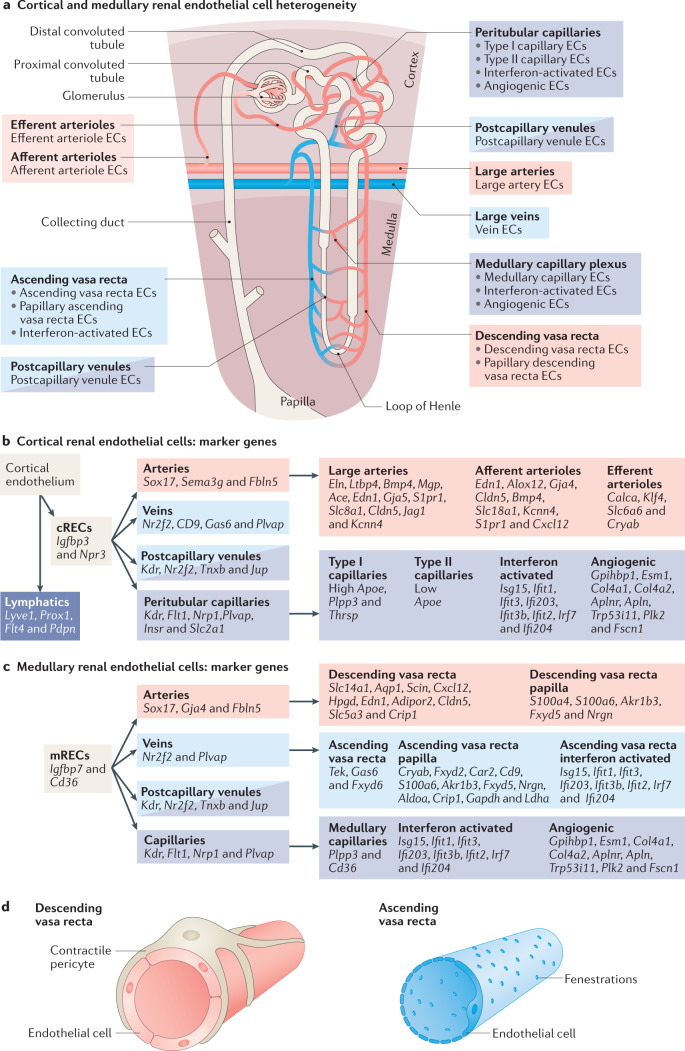

Fig. 3. Phenotypic and molecular heterogeneity of the cortical and medullary renal endothelium.

a | Phenotypically distinct renal endothelial cell (REC) phenotypes coexist within the two main anatomical compartments of the kidney, the cortex and medulla. b | Markers of different cortical REC (cREC) phenotypes. Since REC subpopulations express a combination of several markers, these are indicated following a hierarchical system. c | Markers of different medullary REC (mREC) populations. Since REC subpopulations express a combination of several markers, these are indicated following a hierarchical system. More detailed information regarding the expression and function of genes expressed in cortical and medullary RECs can be found in Supplementary Table 1. d | Phenotypic differences exist between the descending vasa recta (DVR) and the ascending vasa recta (AVR). The arterial-like ECs of the DVR are non-fenestrated and covered by a pericyte layer that regulates the medullary blood flow. By contrast, the venous-like ECs of the AVR are highly fenestrated and lack pericyte coverage, which facilitates water reuptake.

The cortical peritubular capillaries arise from the efferent arterioles and surround the proximal and distal convoluted tubules (Fig. 3a), providing oxygen and nutrients, and contributing to the uptake of solutes and water reabsorption from the tubular lumen9. Unlike glomerular capillaries, peritubular capillary ECs express Plvap, the protein product of which (PV1) spans the peritubular capillary EC fenestrae. These diaphragmed fenestrae are 62–68 nm in diameter and probably facilitate the exchange of water, ions and small solutes with proximal and distal tubules9,10.

Glomeruli filter approximately 180 g of glucose per day78 and under physiological conditions, almost all of it is reabsorbed in the proximal tubules. Filtered glucose is first reabsorbed from the lumen of the proximal tubules inside the epithelial cells through sodium–glucose cotransporters (SGLTs). Once the intracellular glucose concentration exceeds that of the interstitium, it diffuses into the interstitial space through specific facilitated glucose transporters (GLUTs), from where it is reabsorbed into the bloodstream79. In line with their role in this process, peritubular capillary ECs express higher levels of Slc2a1 (encoding GLUT1) than ECs of other renal vascular beds11 (Fig. 3b), suggesting that glucose reabsorption might be facilitated by GLUT1 in peritubular capillary ECs.

Cortical peritubular capillaries include two EC populations — one that expresses high levels of Apoe (encoding apolipoprotein E) and one that expresses little or no Apoe10 (Fig. 3b). The Apoe-high population shows enriched expression of other genes related to lipid metabolism such as Plpp3 and Thrsp10,80,81. By contrast, the Apoe-low population expresses genes encoding VEGF receptors (Kdr, Flt1 and Nrp1, encoding VEGFR2, VEGFR1 and neuropilin 1, respectively), insulin-like growth factor-binding proteins and receptor (Igfbp5, Igfbp3 and Insr), and Npr3, which encodes a receptor for natriuretic peptide, which regulates blood volume and sodium excretion10,82–85. Whether these two EC populations exist in separate capillaries that interact with proximal convoluted tubules or distal tubules, or whether they exist in the same capillaries is currently unknown.

Surprisingly, two additional capillary EC populations have also been described in the mouse renal cortex — an angiogenic-like EC population and a population that is characterized by the expression of interferon-stimulated genes and genes involved in antigen processing and presentation10 (Fig. 3b). The angiogenic-like ECs might have a role in the regeneration of damaged RECs, whereas the interferon-activated ECs might participate in immune surveillance, although further studies are needed to investigate these possibilities10.

cRECs in large arteries are characterized by the expression of the arterial transcription factor gene Sox17 and the tight junction gene Cldn5 (claudin 5), whereas cRECs in large veins are characterized by the expression of the transcription factor Nr2f2 (COUP-TFII), and the fenestration marker Plvap6,10,11,47,63,64,86 (Fig. 3b). Arterial cRECs express the semaphorin-encoding gene Sema3g, which has autocrine and paracrine effects on ECs and VSMCs, respectively, the connexin-encoding genes Gja4 and Gja5, which are components of myoendothelial junctions, and the Notch family member Jag1 (refs6,10,11,87–90) (Fig. 3b). Large arteries are exposed to high blood pressure and their vascular tone is modulated in response to changes in blood pressure. Their ability to respond to mechanical signals is enabled by the presence of an elastic layer in the tunica media that is rich in elastic fibres9,91, and through the expression of genes related to elastic fibre assembly such as Eln (elastin), Ltbp4 (latent-transforming growth factor-β-binding protein 4), Fbln5 (fibulin 5) and Bmp4 (refs6,10,11,92–95). They also express high levels of Mgp (matrix Gla protein)6,10, which suppresses vascular calcification probably through inhibition of BMP2 and BMP4 signalling96. Consistent with their role in regulating renal blood flow, cRECs of the large arteries also express genes that are responsible for vasotone regulation such as Ace, Edn1 and S1pr1 (refs6,10,97–99) (Fig. 3b).

The delivery of oxygen and nutrients and the removal of waste products released within the vascular wall of large arteries and veins are facilitated by the vasa vasora100. Vasa vasora RECs were not identified in the published studies of mouse single-cell RECs, presumably because vessels with a lumen diameter of <0.5 mm (the diameter of normal vessels in mice) do not normally have vasa vasora6,10,11,100. Performing such studies in larger animals or in humans, which have larger renal vessels, may increase the likelihood of capturing vasa vasora RECs. There are currently no markers described for RECs derived from vasa vasora.

Beyond the blood vascular system, the renal cortex also contains two sets of renal lymphatic vessels. Both of these originate as blind-ended capillaries in the renal lobule from where one set follows the arteries towards the hilum to connect the hilar and capsular system and the other penetrates the capsule to join the capsular lymphatics28,101 (Fig. 1a). The renal lymphatic capillaries can be distinguished from blood vessel capillaries as they are mainly present in the interstitium, are blind-ended and lack pericytes28,29. Renal lymphatic capillaries consist of single-layered, ‘oak-leaf’-shaped, partially overlapping LECs28,29, which can be distinguished from BECs by the expression of several markers6, of which the best-known are Pdpn (podoplanin)102, the hyaluronan receptor-encoding gene Lyve1 (ref.103), Flt4 (which encodes VEGFR3)104 and the transcription factor gene Prox1 (ref.105) (Fig. 3b). Although these markers are also expressed in other cell types, they can be used to distinguish between the two major EC types29. In the human kidney, podoplanin has been described as being the most reliable marker of LECs28,29. Nonetheless, neither of the two known kidney LEC populations have been identified in published single-cell RNA-seq studies6,10,11, possibly owing to their loss during technical processing steps (for example, during enzymatic digestion or EC purification), and/or because they represent too small an EC fraction compared with the population of renal BECs. Further studies are therefore needed to characterize the heterogeneity of the renal lymphatic endothelium.

Heterogeneity of the medullary renal endothelial cells

The primary role of the renal medulla is urine concentration9. The anatomical arrangement of the vasa recta and low blood flow of the renal medulla (10% of total renal blood flow9), prevent wash-out of solutes, such as urea and NaCl, creating an osmolarity gradient from the outer medulla to the renal papilla, which is essential for urine concentration26,106. This gradient varies according to hydration status106.

The renal medullary endothelium is characterized by the expression of Igfbp7 (refs10,11), a urinary marker of kidney injury that predicts renal recovery after acute kidney injury (AKI)107, and Cd36 (refs10,32), which encodes a scavenger receptor that is responsible for the uptake of long-chain fatty acids from the circulation108 (Fig. 3c). Hence, lipids might shuttle in a CD36-dependent manner through the medullary endothelium to medullary interstitial cells, a fibroblast-like cell population that is characterized by lipid droplets, the abundance of which correlates with the state of diuresis109. Deletion of Cd36 in mice was associated with an increased kidney-dependent risk of spontaneous hypertension10,110, but attenuated the development of kidney fibrosis in response to a high-fat diet111 (Fig. 3c), therefore suggesting both a protective and a pathological role for lipid transport in these processes.

Like the cortical and glomerular endothelia, the renal medullary endothelium exhibits extensive intra-compartmental heterogeneity10,11. The DVR are arterial-like vessels comprising a continuous endothelium surrounded by smooth muscle-like pericytes or VSMCs that respond to vasoactive stimuli to control renal medullary blood flow. Consistent with their arteriolar-like phenotype, DVR ECs express Sox17 (refs10,55), Cldn5 (refs10,55,86,112), Fbln5, Gja4 and Cxcl12 (CXCL12, also known as SDF1 — a chemokine protein that acts as a ligand for CXCR4 and CXCR7 expressed by VSMCs and pericytes)10,63,113. DVR ECs also express Slc14a1 and Aqp1 which encode the urea transporter B (UTB)10,11,112 and the water channel aquaporin 1 (refs10,11,55), both of which are required for urine concentration114,115 (Fig. 3c,d). These ECs also express Scin, which encodes scinderin — a protein that binds aquaporin 2 in a multiprotein complex in collecting duct epithelial cells, presumably to facilitate aquaporin 2 trafficking116. The co-expression of Aqp1 and Scin in DVR ECs suggests a similar interaction in the medullary endothelium10.

The osmolarity gradient establishes a hostile environment for cells of the renal medulla, especially for those in the renal papilla, where osmolarity is highest (corresponding to a condition of physiological hyperosmolarity in which the osmolarity is higher than in the systemic plasma)117. Mouse DVR ECs can be separated into two main phenotypes according to their location in the renal papilla or in the outer or inner medulla10, and distinguished by the expression of hyperosmolarity-induced and of vasotone-regulatory genes10 (Fig. 3c). Renal papilla DVR ECs express hyperosmolarity-responsive genes, including target genes of the hyperosmolarity-inducible transcription factor NFAT5, such as S100a4 and S100a6 (refs10,118), whereas DVR ECs from the inner and outer medulla show enriched expression of Hpgd, which encodes a major enzyme involved in the catabolism of vasoactive prostaglandins, Edn1, which encodes the vasoconstrictor endothelin 1, and Adipor2, which encodes a receptor for adiponectin that induces vasodilator effects119,120 (Fig. 3c). This expression pattern is consistent with the more prominent presence of smooth muscle-like pericytes in the outer medullary portion of the DVR and hence the greater responsiveness of this region to vasoactive factors, as compared with lower DVR portions9,121.

Unlike the DVR, AVR are fenestrated venous-like vessels (Fig. 3d). These vessels reabsorb water from the renal medullary interstitium that accumulates during urine concentration by the collecting ducts, the loop of Henle and the DVR, collecting it back into the general circulation in a manner akin to the function of lymphatic vessels30. In line with this role, AVR ECs express the venous transcription factor Nr2f2 (refs10,11,64) and Plvap — probably to sustain their role in water reabsorption10,11,47,122 (Fig. 3c). AVR ECs also express Tek, encoding the angiopoietin Tie2 receptor, which is necessary for AVR formation during development. Deletion of Tek in mice triggers the rapid accumulation of fluid and cysts in the medullary interstitium and loss of medullary vascular bundles, and results in decreased urine concentrating ability30.

Similar to DVR, the AVR can be separated into two transcriptomically different EC populations located in the papilla and in the outer and inner medulla. Those in the papilla are characterized by the expression of hyperosmolarity-responsive genes (Cryab, Fxyd2 and Cd9 (refs10,123,124)), glycolytic genes (Ldha, Aldoa and Gapdh10,125,126), and Car2, which encodes the carbonic anhydrase 2 enzyme, the absence of which impairs urine concentration and triggers polyuria in mice127 (Fig. 3c). Papillary AVR ECs specifically express the Na+/K+ ATPase subunit-encoding gene Fxyd2, whereas an alternative subunit-encoding gene Fxyd6 is upregulated in AVR ECs in the outer and inner medulla10 (Fig. 3c).

The papillary portions of the AVR and DVR display distinct gene expression profiles, but share the expression of several hyperosmolarity-responsive genes, including Akr1b3, which encodes aldose reductase — the rate-limiting enzyme of the polyol pathway that is responsible for the conversion of glucose into sorbitol, an inert organic osmolyte that is important for cell volume maintenance under conditions of hyperosmolarity117. They also express S100a6, as well as other genes — such as Fxyd5 (which encodes another Na+/K+ ATPase subunit), Nrgn (which encodes the calmodulin-binding protein neurogranin) and Crip1 (which encodes cysteine-rich protein 1)10,118 — that might potentially be linked to the hyperosmotic environment (Fig. 3c).

The renal medullary capillary plexus, which connects the DVR and AVR (Fig. 3a), is characterized by a Plvap-positive fenestrated endothelium and the enriched endothelial expression of genes that encode VEGF receptors, such as Kdr, Flt1 and Nrp1, as well as genes involved in fatty acid transport and metabolism (Cd36 and Plpp3)10 (Fig. 3c). mRECs also include ECs from postcapillary venules, as well as angiogenic and interferon-activated EC populations, similar to the capillaries of the renal cortex10.

REC heterogeneity and kidney disease

Under physiological conditions the endothelium is quiescent — a state that is maintained in large part through the S-nitrosylation of proteins and transcription factors by eNOS-derived NO128,129. The activity of eNOS itself is regulated by shear stress130 and intracellular metabolites, such as the eNOS substrate, l-arginine and its cofactor, tetrahydrobiopterin131. Under particular conditions — for example, in response to infection — this quiescent state can be switched off, inducing the activation of ECs and the recruitment of the immune cells. Redox signalling and in particular, uncoupling of the eNOS enzyme resulting in the production of superoxide instead of NO is critical to this activation process. The uncoupling of eNOS sets in motion a cascade that leads to remodelling of the endothelial surface layer and induces the expression of receptors that can interact with platelets and immune cells132. Although endothelial activation forms part of the host defence system, this molecular machinery can be inappropriately activated in disease conditions such as autoimmune disease or in the setting of cardiovascular risk factors or infection. Of note, heterogeneity exists in the response of RECs to injurious signals133. For example, in atypical haemolytic uraemic syndrome, mutations in the complement inhibitory factor H are associated with reduced factor H binding to glomerular endothelial heparan sulfate134, thus inducing a glomerular thrombotic microangiopathy. Another example is chronic humoral allograft rejection in which the peritubular capillaries seem to be the primary target of injury135; the associated loss of the peritubular capillary network predicts the occurrence of kidney failure136. In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is of note that AKI is frequently observed in patients with severe disease (affecting up to 50% of patients in intensive care units)137, in whom widespread EC dysfunction might promote disease escalation as a result of vascular leakage, coagulopathy and exacerbated inflammation138,139.

In addition to heterogeneity in the endothelial activation response, the response of RECs to environmental cues from the circulation may be site-specific. For example, gRECs from patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus demonstrate a dysregulated angiogenic response resulting in glomerular growth and secondary podocytopathy140,141. In ischaemic injury — in peritubular capillaries in particular — endothelial activation and sloughing off of ECs result in the so-called ‘no-reflow’ phenomenon, whereby perfusion is not restored even upon restoration of patency, resulting in tubular epithelial cell injury and AKI142. The clinical pathology induced by REC activation is discussed in detail elsewhere8.

The emergence of high-resolution techniques such as single-cell RNA-seq has provided new insights into the molecular regulation of endothelial phenotypic heterogeneity and the processes involved in kidney injury. A number of studies over the past few years, from our group and others, have advanced the concept that endothelial heterogeneity is interlinked with the intracellular metabolism3,6,10,143–145. As described below, the different microenvironments to which RECs are exposed help establish both their phenotypic diversity and metabolic specialization.

Metabolic specialization of RECs

ECs exhibit an active metabolism even when quiescent to sustain processes such as energy production, biomass synthesis and redox homeostasis, which are necessary for the maintenance of vascular barrier integrity, vasoregulatory function, solute transport, and inhibition of thrombosis and vascular inflammation. For instance, quiescent ECs sustain high levels of FAO, which helps maintain vascular barrier integrity in part through the regeneration of NADPH, which provides protection against reactive oxygen species (ROS)146. In line with this role, inhibition of FAO in ECs increases oxidative stress, endothelial barrier permeability, leukocyte infiltration146 and endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition147, suggesting that FAO is required for the maintenance of endothelial function and phenotype. RECs show different metabolic profiles and transcriptomes to ECs isolated from other organs in mice3,6. In particular, they are characterized by upregulation of genes involved in amino acid and pyrimidine biosynthesis as well as glucose metabolism6. Moreover, some metabolic genes are selectively enriched in arterial, capillary or venous ECs, indicative of intra-organ metabolic heterogeneity6. As discussed below, different microenvironmental conditions to which different REC populations are exposed might also affect their metabolic profiles, and support REC phenotypic heterogeneity as well as their response to disease stimuli.

REC responses to changes in oxygen tension

Although kidneys are the most perfused organs in the body, less than 10% of circulating oxygen is consumed during the passage of blood through the kidneys148. The kidney medulla is exposed to low oxygen tension, with a pO2 of 10–20 mmHg (hypoxia) compared with 50 mmHg in the kidney cortex117 (Fig. 4a). The oxygen gradient that follows the corticopapillary axis is the consequence of several factors, including an arteriovenous oxygen shunt that results from the parallel arrangement of the AVR and DVR in the medulla, the limited blood flow to and within the medulla to minimize the washout of solutes, and the use of oxidative phosphorylation to produce the high levels of energy required for the Na+/K+ ATPase to reabsorb Na+ and to enable the proper functioning of other cell membrane solute transporters117. Thus, hypoxia is inherent to the urine concentration mechanism of the medulla10,117. It is also required for appropriate kidney development149. However, hypoxia can be detrimental and is considered a major cause of AKI150, and a risk factor for chronic kidney disease (CKD)151 (Fig. 4a). Kidney hypoxia can result from ischaemic events, such as can occur during kidney transplantation or as a result of abnormal renal perfusion due to peritubular capillary rarefaction, glomerular injury, atherosclerosis, dysregulation of arterial vascular tone, anaemia and impaired oxygen diffusion due to fibrosis152 (Fig. 4a). Within the vascular system, short-term exposure to hypoxia causes reversible modulation of vascular tone and blood flow, whereas long-term exposure results in irreversible remodelling of the vasculature and the surrounding tissues with VSMC proliferation and fibrosis153.

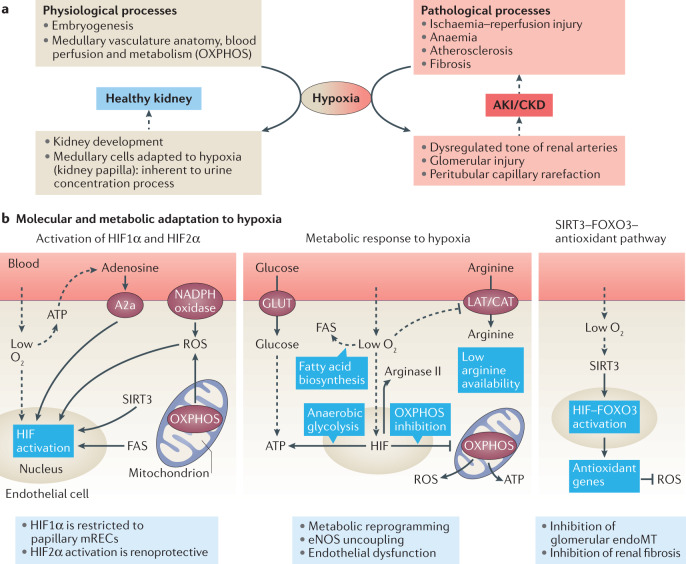

Fig. 4. Exposure of the renal endothelium to changes in oxygen tension.

a | The kidney is exposed to hypoxia under both physiological and pathological circumstances, such as in acute kidney injury (AKI) and chronic kidney disease (CKD). b | Endothelial cells (ECs) adapt to hypoxia by stabilizing and activating the transcription factor hypoxia inducible factor (HIF) through the direct effects of low O2 levels, the release of ATP and downstream activation of the adenosine A2a receptors, the production of NADPH-derived and oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS)-derived reactive oxygen species (ROS), and as a consequence of sirtuin 3 (SIRT3) activation and the upregulation or activation of fatty acid synthase (FAS) (left panel). Exposure to hypoxia affects the metabolism of ECs by enhancing anaerobic metabolism and fatty acid biosynthesis while repressing aerobic metabolism (OXPHOS). Levels of the metalloenzyme arginase II are increased whereas arginine uptake is repressed, leading to low intracellular arginine availability, which results in endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) uncoupling and the production of ROS (central panel). ECs counteract ROS produced as a result of the exposure to hypoxia by activating a SIRT3–forkhead box 3 (FOXO3)-dependent antioxidant gene expression pathway (right panel). CAT, cationic amino acid transporter; endoMT, endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition; GLUT, glucose transporter; LAT, large neutral amino acid transporter.

The cellular response to hypoxia depends on the inactivation of Fe2+-dependent oxygenases and 2-oxoglutarate (2-OG)-dependent oxygenases152, and the subsequent activation of hypoxia-inducible transcription factor (HIF)-dependent and HIF-independent pathways. Exposure to hypoxia triggers the activation of both HIF1α and HIF2α in ECs154 (Fig. 4b). In the kidney, RECs widely express HIF2α upon hypoxia, while protein expression of HIF1α is limited to mRECs in the papilla155–157, where it probably stimulates glycolysis (Fig. 4b). Activation of HIF2α in RECs in general mediates protection and recovery from ischaemic kidney injury by promoting erythropoiesis, and by suppressing renal inflammation, capillary rarefaction and fibrosis156 (Fig. 4b). Exposure of RECs to hypoxia in the context of kidney disease might therefore induce different responses in gRECs and cRECs than in mRECs. For example, hypoxia promotes HIF1α-dependent proliferation and migration of cultured ECs158,159; however, in non-confluent conditions, cultured gRECs undergo mitochondria-dependent apoptosis upon exposure to hypoxia155,160,161, suggesting a maladaptation of gRECs to hypoxia. Although gRECs seem to be quite resistant to hypoxia in vivo, probably owing to the paracrine effect of podocyte-derived VEGF161, hypoxia can induce a progressive loss of the tight junction proteins occludin and ZO-1 in gRECs in a HIF2α-dependent manner, ultimately increasing endothelial barrier permeability162. Little is known about the response of mRECs to hypoxia. mRECs in the AVR and DVR in particular are exposed to low oxygen tension in the papilla under physiological conditions, and the Epas1 regulon (encoding HIF2α) is upregulated in mRECs upon water deprivation, probably in response to an increase in hypoxia driven by the urine concentration process10.

Metabolic adaptation of ECs to changes in oxygen tension

Under normoxic conditions, ECs rely primarily on glycolysis for ATP production rather than mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation163. In response to hypoxia, these metabolic responses are exacerbated, with further enhancement of glycolysis and suppression of mitochondrial respiration (Fig. 4b), explaining why ECs are resistant to hypoxia as long as glucose remains available164. Upon exposure to acute hypoxia such as an ischaemic event, ECs show a rapid increase in mitochondrial and/or NAD(P)H oxidase-derived ROS, which stabilizes HIF1α and enables higher glycolytic flux164 — responses that are consistent with a HIF1α-induced upregulation of glucose metabolism and a downregulation of mitochondrial activity164,165 (Fig. 4b). Moreover, metabolic pathway analyses of ECs exposed to chronic hypoxia, such as can occur in the medulla or in the context of CKD, revealed a HIF2α-dependent upregulation of glycolytic genes166. Interestingly, some glycolytic genes such as Eno1 and Aldoa, which encode the enzymes enolase 1 and aldolase A that are necessary to produce ATP and pyruvate from glucose, were upregulated to a greater extent in mRECs than in cRECs and gRECs10. More specifically, mRECs from the papillary portion of the AVR — that is the portion of the renal vascular bed that is most exposed to hypoxia — showed the highest expression of the glycolytic genes Aldoa, Ldha and Gapdh among all mRECs in mice10. Thus, papillary mRECs might demonstrate higher anaerobic glycolytic flux than other RECs as a result of their hypoxic microenvironment. Similarly, medullary epithelial cells have a higher capacity for anaerobic glycolytic ATP production than proximal tubular cells117. mRECs also upregulate several glycolytic genes upon water deprivation, concurrent with the increased HIF2α activity mentioned above10.

In ECs, HIF2α is upregulated in part following activation of the mitochondrial NAD+-dependent deacetylase sirtuin 3 (SIRT3) (ref.167) (Fig. 4b). Loss of SIRT3 impairs hypoxic signalling in ECs, and results in defective angiogenesis and microvascular dysfunction, secondary to a metabolic switch from oxygen-independent glycolysis to mitochondrial respiration. This metabolic switch is associated with a decrease in the expression of 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase (PFKFB3), an enzyme that acts as a positive regulator of glycolysis and ROS formation167 (Fig. 4b). Upon hypoxia, SIRT3 upregulates mitochondrial antioxidant enzymes in a manner dependent on FOXO3 (ref.168) — a transcription factor that is also upregulated by HIF1α169 (Fig. 4b). Interestingly, the SIRT3–FOXO3 antioxidant pathway is operational in gRECs, preventing endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition and kidney fibrosis in an animal model of angiotensin-II-induced hypertension170 (Fig. 4b). Pharmacological approaches that increase SIRT3 also limit cisplatin-induced AKI by protecting against tubular injury and by improving kidney function171. By contrast, Sirt3-knockout mice exhibit more severe AKI, although the contribution of RECs to these effects has not been determined171. Whether this SIRT3–FOXO3 antioxidant pathway is also involved in the physiological response of mRECs to hypoxia in the medulla remains to be determined.

The metabolism of fatty acids is also affected by oxygen availability, since hypoxia triggers an increase in the expression and activity of fatty acid synthase (FAS), a key rate-controlling enzyme of the fatty acid biosynthesis pathway, resulting in a reduction of the malonyl-coA pool and an augmentation of palmitate levels in ECs172 (Fig. 4b). In human pulmonary artery ECs, inhibition of FAS leads to impairment of HIF1α stabilization, and subsequent HIF1α-mediated changes in glucose transport and metabolism and to the restoration of eNOS function, suggesting that the inhibition of fatty acid synthesis may be beneficial for EC function in hypoxia172 (Fig. 4b). In the kidney, Fasn — which encodes FAS — was upregulated in an experimental model of chronic kidney failure and contributed to hypertriglyceridaemia173. Upregulation of Fasn and other hypoxia-responsive genes was also observed in the kidney cortex of a mouse model of sickle cell anaemia that exhibited progressive glomerular and tubular damage174. Altered lipid metabolism is a characteristic of proteinuric CKD and both clinical and experimental evidence support the notion that altered lipid metabolism might contribute to the pathogenesis and progression of kidney disease175. Nonetheless, the role of RECs in dysregulated fatty acid metabolism in the context of kidney disease remains to be further clarified.

Hypoxia also induces the upregulation of arginase II in a manner dependent on the activation of HIF2α176 or HIF1α177, and decreases the synthesis and transport of its substrate, arginine, in ECs178,179 (Fig. 4b). Arginase II is a metalloenzyme that is particularly expressed in the kidneys and catalyses the hydrolysis of l-arginine into urea and l-ornithine. The increase in arginase II activity lowers arginine bioavailability, which dampens eNOS activity, decreasing endothelial NO production and triggering eNOS uncoupling, ultimately leading to the production of ROS and nitrosative stress176. These steps are critical in promoting endothelial dysfunction, diabetic kidney disease and kidney inflammation in the context of diet-induced obesity180,181. Under physiological conditions, arginase II is mainly expressed in the outer medulla, suggesting that this metabolic adaptation probably does not occur in the mRECs that are most exposed to hypoxia181.

Finally, exposure of papillary mRECs to acute hypoxia triggers the release of purines and ATP, together with UTP and UDP, in the extracellular space182–184. ATP activates endothelial P2Y receptors, resulting in NO production, vasodilation and increased tissue perfusion185. ATP also forms adenosine following metabolism of the ATP by ectoenzymes185,186. Importantly, hypoxia triggers a HIF2α-dependent upregulation of adenosine A2a receptor (encoded by ADORA2A) in ECs187,188, the activation of which increases HIF1α protein synthesis, further promoting glycolytic gene expression and glycolytic flux187 (Fig. 4b). In most instances, activation of A2a and A2b receptors expressed by ECs and VSMCs mediates the vasodilator effects of adenosine released during hypoxia185. In the kidney, different adenosine receptors are present in the different parts of the vasculature189, and extracellular ATP and adenosine exert key roles in the regulation of renal haemodynamics and the microcirculation185,190. In the medulla, adenosine is produced in the medullary thick ascending limb of the loop of Henle (TALH) after oxidative stress191 and acts as a vasodilator, inducing an increase in medullary blood flow via a mechanism that may involve DVR mRECs192. However, contrary to its effects in most other vessels, adenosine-mediated activation of A2a receptors, which are particularly expressed in the afferent arterioles, triggers vasoconstriction of the renal vasculature, thereby potentially affecting renal blood flow and glomerular filtration185,193. Of note, a role for purinergic receptors in CKD progression has been identified194.

REC responses to changes in shear stress

ECs are constantly exposed to a force of stretch induced by the pulsatility of blood flow and a frictional force parallel to the vessel wall, the fluid shear stress195. These cells are equipped to sense these forces and to transduce them into biochemical signals that can affect vessel homeostasis by regulating vascular tone and EC remodelling, which adjusts the blood flow to meet tissue requirements195. Interestingly, ECs from different portions of the vascular bed are exposed to specific flow types and respond accordingly195 (Fig. 5a). In arteries and arterioles, blood flow is highly pulsatory, whereas in capillaries it is of similar magnitude but less pulsatory, and in venules and veins blood flow is about threefold to tenfold lower and pulsatility is minimal195. In the kidney, the vasculature of the cortex receives >94% of renal blood flow196 suggesting that the medullary vasculature is exposed to a relatively low shear stress environment. By contrast, gRECs are exposed to a relatively high shear stress environment (estimated to be from 1 dyn/cm2 to as high as 95 dyn/cm2), as a result of high blood flow and pressure combined with increasing blood viscosity as a result of the filtration process197 (Fig. 5b). Exposure of gREC to shear stress is critical since it prevents platelet aggregation, in part by inducing the conformational unfolding of the blood glycoprotein von Willebrand factor (vWF) which enhances its susceptibility to cleavage by the ADAMTS13 metalloprotease198,199. The importance of this phenomenon to gREC health is demonstrated by the pro-thrombotic phenotype observed in Shiga toxin-associated haemolytic uraemic syndrome. Shiga toxin promotes the secretion of vWF by gRECs and the formation of ultra-large vWF multimers that are resistant to cleavage by ADAMTS13 and induce thrombotic microangiopathy in glomeruli and the kidney microvasculature200, eventually leading to AKI. In thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, low ADAMTS13 activity results in a similar outcome199.

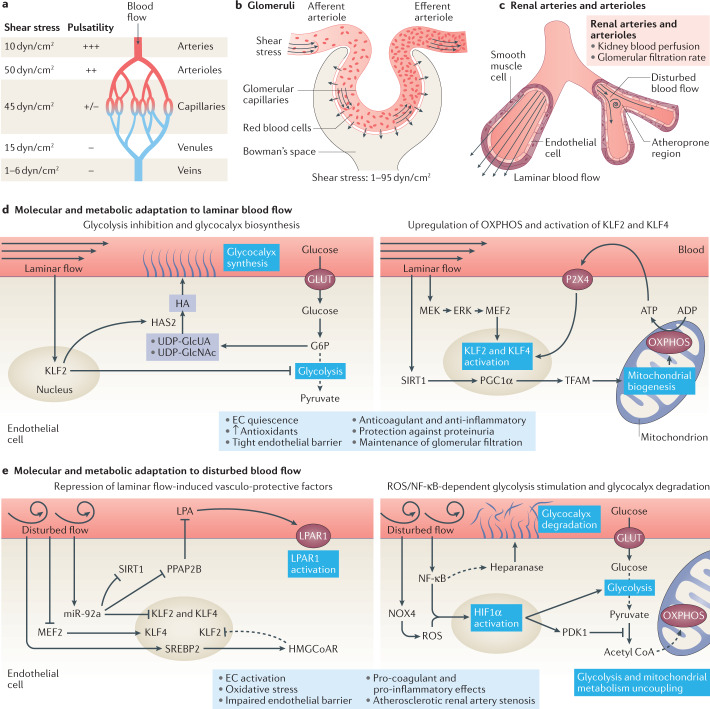

Fig. 5. Response of the renal endothelium to changes in blood flow and shear stress.

a | Arteries, arterioles, capillaries, venules and veins are exposed to different types of blood flow as defined by its pulsatility and the level of shear stress. b | Glomerular capillaries are exposed to high shear stress as a result of high blood flow and pressure together with increasing blood viscosity due to the filtration process. c | Some regions of renal arteries and arterioles — which control kidney blood perfusion and glomerular filtration rate — are exposed to laminar blood flow, whereas other regions — particularly regions of vessel bifurcation — are exposed to disturbed blood flow. Regions of disturbed blood flow are more likely to develop atherosclerotic lesions. d | Endothelial cells (ECs) exposed to laminar blood flow inhibit glycolytic metabolism in a KLF2-dependent manner and divert glycolytic intermediates to pathways involved in glycocalyx biosynthesis (left panel). Laminar flow also induces SIRT1–PGC1α–TFAM-mediated mitochondrial biogenesis, and stimulates the production of oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS)-derived ATP, which activates purinergic P2X4 receptors and further induces the activation of KLF2 and KLF4 transcription factors. Moreover, Krüppel-like factor 2 (KLF2) and KLF4 are upregulated in response to MEK5–ERK5 pathway activation (right panel). Laminar blood flow promotes EC quiescence, the production of antioxidants, the formation of a tight endothelial barrier and the acquisition of an anticoagulant and anti-inflammatory phenotype, and protects against proteinuria while maintaining glomerular filtration. e | Disturbed blood flow represses the protective pathways induced by laminar blood flow. Induction of microRNA (miR)-92a by disturbed flow represses the endothelial expression of KLF2, KLF4 and SIRT1 and PPAP2B, releasing the inhibitory effect of PPAP2B on circulating lysophosphatidic acid (LPA). Binding of LPA to its receptor LPAR1 induces pro-inflammatory signalling. The induction of SREBP2 upregulates HMG-CoA reductase, which increases intracellular cholesterol levels, and further upregulates miR-92a. Hypermethylation of the KLF4 promoter prevents MEF2 binding and subsequent KLF4 transcription (left panel). ECs exposed to disturbed blood flow also demonstrate an uncoupling of glycolysis from mitochondrial metabolism, with an upregulation of glycolysis. Disturbed flow also induces the production of NOX4-derived reactive oxygen species (ROS) and activates nuclear factor κB (NF-κB), leading to the upregulation and stabilization of hypoxia inducible factor 1α (HIF1α). Activation of the NF-κB pathway has been linked to heparanase activity and consequent glycocalyx degradation (right panel). Disturbed blood flow ultimately triggers EC activation and oxidative stress, impairs the endothelial barrier, induces a procoagulant and pro-inflammatory EC phenotype, and favours the development of atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis. ERK, extracellular signal regulated kinase; G6P, glucose-6-phosphate; GLUT, glucose transporter; HA, hyaluronan; HAS2, hyaluronan synthase 2; HMGCoAR, hydroxymethylglutaryl CoA reductase; MEF2, myocyte enhancer factor-2; MEK, mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase; NOX4, NADPH oxidase 4; PDK1, pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1; PGC1α, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1α; PPAP2B, phosphatidic acid phosphatase type 2B; SIRT1, sirtuin 1; SREBP2, sterol regulatory element binding protein 2; TFAM, mitochondrial transcription factor A; UDP-GlcNAc, uridine diphosphate-N-acetylglucosamine; UDP-GlcUA, uridine diphosphate–glucuronic acid.

The importance of shear stress is also illustrated by the development of atherosclerotic lesions in renal arteries, which can result in renal artery stenosis — the single largest cause of secondary hypertension201,202. These lesions develop in atheroprone regions in the arteries and arterioles that are exposed to lower laminar shear stress than other regions, such as regions of arterial bifurcation, where blood flow is typically disturbed201 (Fig. 5c).

Effects of laminar shear stress on ECs

Laminar shear stress induces upregulation of the transcription factors Krüppel-like factor 2 (KLF2) and KLF4 in ECs, in part through the release of ATP and subsequent activation of P2X4 purinergic receptors203, and in part via activation of the MEK5–ERK5–MEF2 signalling pathway204,205 (Fig. 5d). In the kidney, Klf2 and Klf4 together with the KLF4 target gene, Thbd (which encodes thrombomodulin), have been reported to be markers of gRECs derived from the efferent arterioles in adult mice10,11 (Fig. 3b). The location of these flow-responsive markers is consistent with the fact that RECs located at the immediate exit site of glomeruli are exposed to a high laminar shear stress, potentially related to the high blood viscosity of this region. The upregulation and activation of KLF2 mediates EC quiescence, characterized by an increase in the expression of VE-cadherin and β-catenin to aid the maintenance of a tight vascular barrier206, the alignment of ECs in the direction of flow207, the inhibition of inflammation and maintenance of an anti-atherogenic phenotype, an upregulation of antioxidants and a decrease in vascular tone secondary to the endothelial production of NO and prostacyclins208–210 (Fig. 5d). Activation of KLF2 in gRECs protected them against injury and disease progression in animal models of CKD211,212. Accordingly, KLF2 is upregulated in the glomerular endothelium in response to shear stress in vitro, where it promotes an anticoagulant and anti-inflammatory phenotype and triggers an endothelial-dependent decrease in podocyte barrier resistance, required for proper filtration function204. The upregulation of gREC KLF2 secondary to glomerular hyperfiltration conferred protection against EC dysfunction and attenuated the progression of CKD in a model of unilateral nephrectomy212. Conversely, loss of endothelial KLF2 exacerbated glomerular hypertrophy and proteinuria in a model of streptozotocin-induced diabetic kidney disease211. Endothelial KLF4 is also renoprotective in AKI213. EC-specific loss of KLF4 exacerbated kidney injury in a model of ischaemic AKI by promoting EC acquisition of a pro-inflammatory phenotype213. However, it is worth noting that KLF2 and KLF4 have context-specific roles in the endothelium214. For instance, they can promote the activation of ECs and the formation of lesions leading to cerebral cavernous malformations in development214,215.

Exposure to laminar shear stress reduces glucose uptake216 and stimulates mitochondrial biogenesis in ECs217–219. KLF2 activation downregulates the expression of PFKFB3 together with that of other glycolytic genes such as HK2 (which encodes hexokinase 2) and PFK1 (which encodes phosphofructokinase 1 (PFK1)), resulting in a decrease in glycolysis216, and the shuttling of available early glycolytic intermediates to the hexosamine and glucuronic acid biosynthetic pathway for UDP-GlcUA and UDP-GlcNAc synthesis, respectively, which are the limiting substrates of hyaluronan synthase (HAS2)133,220–222. KLF2 also induces the expression and membrane translocation of HAS2, and the consequent synthesis of the glycocalyx component hyaluronan133,222. Thus, ECs exposed to laminar flow display a much thicker glycocalyx than ECs exposed to disturbed flow133 (Fig. 5d,e). EC-specific deletion of Has2 has profound effects on the kidney, including impairment of the glycocalyx structure of capillary gRECs, disruption of the glomerular endothelial fenestrations40, albuminuria indicative of filtration barrier dysfunction, disturbed glycocalyx-dependent angiopoietin 1 signalling, and abnormal podocyte structures as a result of abnormal EC–podocyte crosstalk, resulting in glomerular capillary rarefaction and glomerulosclerosis40.

Mitochondrial respiration and ATP generation are also increased in ECs under unidirectional flow compared with those exposed to disturbed flow223,224. Blockade of mitochondrial ATP generation inhibits shear stress-induced ATP release whereas by contrast, inhibition of glycolysis has no effect, suggesting that EC mitochondrial respiration is required for purinergic receptor activation, which in turn induces KLF2 expression in response to shear stress203,218,224. Furthermore, mitochondrial biogenesis is upregulated in response to shear stress, owing to the activation of a SIRT1–PGC1a–TFAM signalling cascade217,219, whereas the expression of antioxidant genes, such as haem oxygenase 1 and glutaredoxin 1, are increased to protect ECs from ROS225,226 (Fig. 5d). Inhibiting the electron transport chain in ECs exposed to laminar flow resulted in EC inflammation, suggesting that mitochondrial respiration prevents EC activation223. In the kidney, activation of the 5-HT1F receptor to stimulate mitochondrial biogenesis in RECs may reduce vascular rarefaction and promote recovery from injury as has been shown in a model of AKI227.

KLF4 also induces the upregulation of cholesterol-25-hydroxylase (CH25H) and liver X receptor upon exposure to an atheroprotective pulsatile shear stress228. CH25H catalyses the production of 25-hydroxycholesterol, which prevents the activation of sterol regulatory element binding protein 2 (SREBP2), an important mediator in the EC response to disturbed blood flow (see below)229,230. Hence, modulation of KLF2 and KLF4 expression and activation by laminar shear stress and their consequent metabolic responses may have a critical role in the maintenance of REC quiescence and glomerular filtration (Fig. 5d).

Effects of a disturbed blood flow on ECs

ECs exposed to disturbed blood flow such as in arterial bifurcations or curvatures are activated and exhibit a pro-inflammatory and atherogenic phenotype231 (Fig. 5e). Thus, the activation of arterial and afferent arteriolar RECs located in such atheroprone regions might promote the development of atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis.

KLF4 expression is repressed by disturbed blood flow, with increased methylation of the KLF4 promoter region preventing MEF2 binding and subsequent KLF4 transcription232. Furthermore, microRNA (miR)-92a, which is induced in atheroprone regions in response to low shear stress, represses endothelial expression of KLF2, KLF4 and SIRT1, and downregulates phosphatidic acid phosphatase type 2B (PPAP2B)216,233,234. Under conditions of normal laminar shear stress, PPAP2B dephosphorylates circulating lysophosphatidic acid (LPA), preventing its binding to the LPAR1 receptor, which otherwise induces pro-inflammatory signalling233 (Fig. 5e). Endothelial loss of PPAP2B leads to exacerbated local and systemic inflammation associated with an increase in endothelial permeability235. LPA signalling is involved in kidney disease through the induction of ROS, inflammatory cytokines and fibrosis236.

Endothelial exposure to low shear stress and disturbed flow induces the expression of glycolytic enzymes and of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1 (PDK1), thereby uncoupling glycolysis from mitochondrial metabolism and decreasing mitochondrial respiration in ECs223,237 (Fig. 5e). Mechanistically, disturbed flow induces the production of NAD(P)H oxidase 4 (NOX4)-derived ROS and activates NF-κB, leading to upregulation and stabilization of HIF1α by preventing its degradation223,237. Activation of the NF-κB pathway has been linked to heparinase activity and consequent glycocalyx degradation238. In line with these findings, activation of NF-κB is repressed by chronic shear stress in the glomerular endothelium239. HIF1α activation in response to disturbed flow enhances arterial EC proliferation and expression of inflammatory markers, whereas inhibition of glycolysis prevents these responses223,237. Moreover, activation of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation prevents the pro-inflammatory phenotype induced by disturbed flow in arterial ECs223.

Disturbances in low shear stress also induce activation of the pro-inflammatory transcription factors YAP and TAZ, whereas laminar shear stress inhibits these in an integrin-dependent manner240,241. Activation of YAP and TAZ modulates EC metabolism by stimulating glycolysis and mitochondrial activity in a MYC-dependent manner242, and by upregulating glutaminolysis243. Conversely, the glycolytic enzyme PFK1 stimulates YAP and TAZ activity in a positive feedback loop244. YAP and TAZ are mechanoregulators of the TGFβ–SMAD signalling pathway in the kidney. They have been demonstrated to promote kidney fibrosis in an experimental model of unilateral ureteral obstruction, although the role of RECs in this fibrotic response as a result of endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition has been poorly investigated245,246.

Interestingly, ECs exposed to a disturbed blood flow also show activation of SREBP2, which upregulates genes involved in cholesterol synthesis including the rate-limiting enzyme of the mevalonate pathway HMG-CoA reductase (Fig. 5e), and decreases cholesterol efflux230,247, increasing the intracellular level of cholesterol in ECs230,247. Interestingly, inhibition of HMG-CoA reductase by statins induces an endothelial increase in KLF2 expression, and reduces pro-inflammatory signalling by NF-κB, HIF1α and YAP–TAZ, thereby inducing an EC-like response to laminar flow241,248,249. Furthermore, SREBP2 activation promotes the transcription of miR-92a, upregulates the expression of NOX2, which induces production of ROS, and increases the expression of the NLRP3 inflammasome, ultimately promoting endothelial inflammation and atherosclerosis216,230. Thus, SREBP2 may be one of the key drivers in the renal arterial and afferent arteriolar endothelial response to a disturbed flow.

REC responses to changes in osmolarity

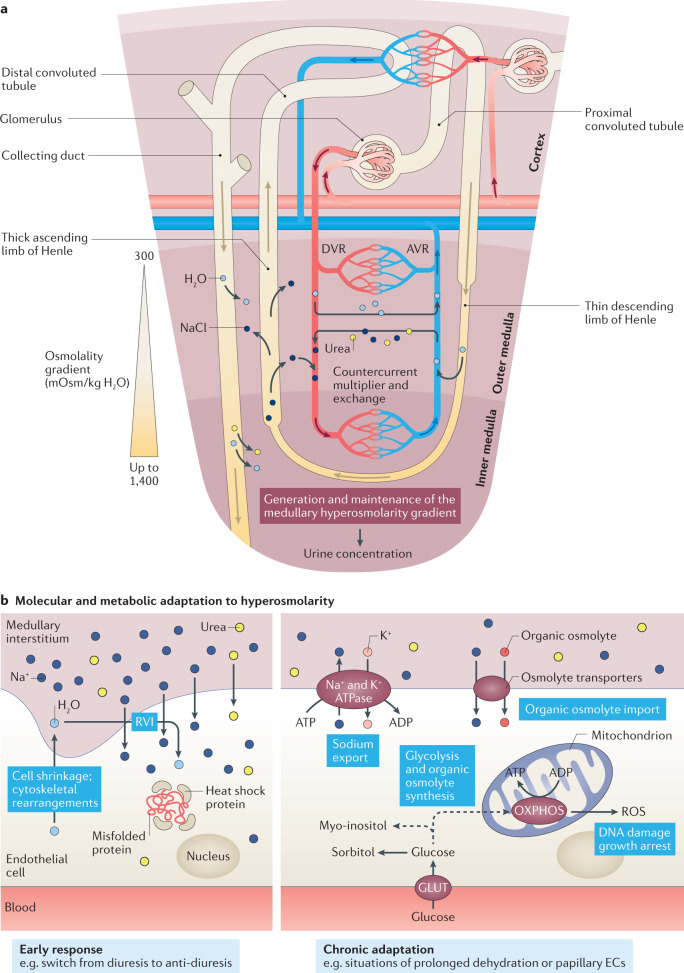

The kidneys can produce urine of widely varying osmolarity depending on hydration status. The countercurrent multiplier of the loop of Henle generates a medullary osmolarity gradient that underlies the urine concentration mechanism and determines the final urine osmolarity. Briefly, the TALH — a tubule segment that is mostly impermeable to water — actively shuttles NaCl from the filtrate to the medullary interstitium, establishing a 20 mOsm/kg H2O osmolality difference across the ascending and descending flow250 (Fig. 6a). As an osmotic response, water is reabsorbed through the thin descending limb of Henle (TDLH), thereby increasing filtrate osmolarity250. As this filtrate progresses from the TDLH to the TALH, active reabsorption of NaCl by the TALH re-establishes the 20 mOsm/kg H2O osmolality difference between the TALH and interstitium, further increasing medullary interstitium osmolarity250. The multiplication of these small osmolality differences between countercurrent flows leads to a large corticomedullary osmolality gradient (a countercurrent multiplier)250. At the level of the vasa recta, water efflux facilitated by aquaporins occurs in parallel with the reabsorption of urea and NaCl within the DVR, driven by the difference between the blood and medullary osmolarity, resulting in an increased blood osmolarity towards the papilla250 (Fig. 6a). By contrast, the highly fenestrated AVR reabsorb medullary water and release NaCl into the interstitium, since the blood coming from the papilla is of higher osmolarity than the medullary interstitium250 (Fig. 6a). This countercurrent exchange between the DVR and AVR maintains the medullary osmolarity gradient created by the countercurrent multiplier system (Fig. 6a). The high osmolarity of the medulla is also sustained by the collecting ducts, which actively export urea within the inner medullary interstitium, while concentrating urine according to the medullary osmolarity gradient via aquaporin-facilitated water transport. As a consequence, medullary cells including mRECs are exposed to extreme levels of hyperosmolarity, especially under conditions of dehydration wherein osmolality can rise as high as 1,400 mOsm/kg in humans250 (Fig. 6a). As described below, available evidence suggests that mRECs have adapted to these extreme conditions by activating protective mechanisms and developing a specific metabolic profile10. Of note, other (R)ECs can be exposed to hyperosmolar conditions as a consequence of hyperglycaemia in the context of diabetes mellitus251.

Fig. 6. Response of the renal endothelium to changes in osmolarity.

a | The renal medullary and papillary regions of the kidney are exposed to hyperosmolarity as a consequence of the countercurrent multiplier and exchange mechanisms, which generates and maintains the medullary hyperosmolarity gradient (ranging from 300 mOsm/kg H2O at the corticomedullary junction to up to 1,400 mOsm in the papilla) that drives the process of urine concentration. b | In response to a rapid increase in osmolarity (for example, following a switch from diuresis to anti-diuresis) endothelial cells (ECs) tend to shrink as a consequence of water loss. This response results in cytoskeletal rearrangements and activation of a regulatory volume increase (RVI) compensatory mechanism, characterized by an accumulation of intracellular Na+ and urea followed by osmotic water reabsorption. Moreover, the expression of heat shock proteins is induced to preserve the correct folding of proteins from high levels of denaturing urea (left panel). Prolonged exposure to hyperosmolarity, such as occurs in the papilla or during situations of prolonged dehydration, induces ECs to promote the production of ATP from oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS), and stimulate active Na+ export through the Na+/K+ ATPase as well as the import and synthesis of inert organic osmolytes (such as glucose-derived polyols) to protect the cell from hyperosmolarity-induced cell damage (right panel). AVR, ascending vasa recta; DVR, descending vasa recta; GLUT, glucose transporter; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

The response of ECs to conditions of hyperosmolarity has been poorly investigated, with most of the research in this field focusing on renal epithelial cells, in which hyperosmolarity triggers cell cycle arrest, the production of ROS and DNA damage252. Specifically, the epithelial response to hyperosmolarity is characterized by a reorganization of the cytoskeletal actin via a process dependent on integrins and the Rho family of GTPases253, activation of the Na+ channels NHE4 (ref.254), NKCC1 and NKCC2 (ref.255), and the resulting influx of Na+ ions for maintenance of cell volume. These responses trigger the expression of heat shock proteins to maintain the correct folding of proteins and activation of the hyperosmolarity-sensitive transcription factor TonEBP (also known as NFAT5); under conditions of prolonged hyperosmolarity, such as in the papilla, these responses ultimately result in the accumulation of inert organic osmolytes252.