Abstract

The hypothalamus contains catecholaminergic neurons marked by the expression of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH). As multiple chemical messengers coexist in each neuron, we determined if hypothalamic TH-immunoreactive (ir) neurons express vesicular glutamate or GABA transporters. We used Cre/loxP recombination to express enhanced GFP (EGFP) in neurons expressing the vesicular glutamate (vGLUT2) or GABA transporter (vGAT), then determined whether TH-ir neurons colocalized with native EGFPVglut2- or EGFPVgat-fluorescence, respectively. EGFPVglut2 neurons were not TH-ir. However, discrete TH-ir signals colocalized with EGFPVgat neurons, which we validated by in situ hybridization for Vgat mRNA. To contextualize the observed pattern of colocalization between TH-ir and EGFPVgat, we first performed Nissl-based parcellation and plane-of-section analysis, and then mapped the distribution of TH-ir EGFPVgat neurons onto atlas templates from the Allen Reference Atlas (ARA) for the mouse brain. TH-ir EGFPVgat neurons were distributed throughout the rostrocaudal extent of the hypothalamus. Within the ARA ontology of gray matter regions, TH-ir neurons localized primarily to the periventricular hypothalamic zone, periventricular hypothalamic region, and lateral hypothalamic zone. There was a strong presence of EGFPVgat fluorescence in TH-ir neurons across all brain regions, but the most striking colocalization was found in a circumscribed portion of the zona incerta (ZI)—a region assigned to the hypothalamus in the ARA—where every TH-ir neuron expressed EGFPVgat. Neurochemical characterization of these ZI neurons revealed that they display immunoreactivity for dopamine but not dopamine β-hydroxylase. Collectively, these findings indicate the existence of a novel mouse hypothalamic population that may signal through the release of GABA and/or dopamine.

Keywords: zona incerta, dopamine, hypothalamus, GABA, tyrosine hydroxylase, catecholamine, atlas

List of RRiDs: AB_514500, AB_572229, AB_11214044, AB_221570, AB_2314774, AB_653610, AB_2201528, AB_2340375, AB_2336933, AB_2313584, AB_141708, AB_2534013, AB_2535864, AB_2536183

Graphical Abstract

Nissl-based maps of the distribution of tyrosine hydroxylase immunoreactivity in hypothalamic neurons that coexpress the vesicular GABA transporter revealed striking colocalization within the zona incerta. These neurons also express dopamine immunoreactivity but not dopamine beta hydroxylase, thus dopamine is the likely terminal catecholamine produced by these cells.

1. INTRODUCTION

The prevailing view of neurotransmission is that multiple chemical messengers can coexist, in various combinations, within single neurons and in some cases can even be co-stored in synaptic vesicles (Hökfelt et al., 1986). These chemical messengers may be neurotransmitters like glutamate and GABA that rapidly initiate and terminate discrete synaptic events, or neuromodulators like neuropeptides and catecholamines that can have varied release probabilities, time courses of release, or long-range target sites. In fact, virtually all neuropeptidergic neurons also harbor a neurotransmitter, as exemplified by brain structures in the hypothalamus. For example, neurons in the arcuate hypothalamic nucleus coexpress the neuropeptides Agouti-related protein and neuropeptide Y (Broberger, de Lecea, Sutcliffe, & Hökfelt, 1998; Broberger, Johansen, Johansson, Schalling, & Hökfelt, 1998; Hahn, Breininger, Baskin, & Schwartz, 1998) as well as the neurotransmitter GABA (Tong, Ye, Jones, Elmquist, & Lowell, 2008).

Colocalized neurotransmitters and neuromodulators may work in tandem or opposition to prolong or suppress neuronal functions (van den Pol, 2012). For instance, neurons in the lateral hypothalamus that express either melanin-concentrating hormone (MCH) or hypocretin/orexin (H/O) have transcripts encoding the machinery for vesicular storage of glutamate (Mickelsen et al., 2017). Both of these neuronal populations can release glutamate and produce transient excitatory glutamatergic events (Chee, Arrigoni, & Maratos-Flier, 2015; Schöne, Apergis-Schoute, Sakurai, Adamantidis, & Burdakov, 2014), but MCH inhibits (Sears et al., 2010; Wu, Dumalska, Morozova, van den Pol, & Alreja, 2009) whereas H/O stimulates neuronal activity (Schöne et al., 2014). Additionally, these coexpressed messengers may also serve distinct functions. For example, MCH, but not glutamate from MCH neurons, promotes rapid eye movement sleep (Naganuma, Bandaru, Absi, Chee, & Vetrivelan, 2019), while glutamate has been shown to encode the nutritive value of sugars (Schneeberger et al., 2018).

The colocalization between neuropeptides and catecholamines is also well-studied. The catecholamines are a major class of monoamine messengers that include dopamine, norepinephrine, and epinephrine. Their presence in neurons can indirectly be suggested by the detection of immunoreactivity for tyrosine hydroxylase (TH; EC 1.14.16.2), which mediates the rate-limiting step in catecholamine biosynthesis (Nagatsu, Levitt, & Udenfriend, 1964; Udenfriend & Wyngaarden, 1956). Discrete populations of catecholamine-containing neurons (A Björklund & Lindvall, 1984; A Björklund & Nobin, 1973; Dahlström & Fuxe, 1964), and specifically TH-immunoreactive (ir) neurons (Hökfelt, Johansson, Fuxe, Goldstein, & Park, 1976; Hökfelt, Märtensson, Björklund, Kleinau, & Goldstein, 1984; van den Pol, Herbst, & Powell, 1984), have been detailed in the rat brain and include neurons in the hypothalamus. Hypothalamic TH-ir neurons are primarily found within the zona incerta (ZI) and periventricular parts of the hypothalamus (Hökfelt et al., 1976; Ruggiero, Baker, Joh, & Reis, 1984), which is composed of neurochemically and functionally diverse gray matter regions. For example, hypothalamic dopamine neurons may colocalize with galanin and neurotensin as well as with markers for GABA synthesis (Everitt et al., 1986). Furthermore, recent work has demonstrated that dopaminergic neurons in the arcuate nucleus corelease GABA (Zhang & van den Pol, 2015), and that both neurotransmitters regulate feeding in response to circulating metabolic signals (Zhang & van den Pol, 2016).

Single-cell RNA sequencing has revealed that neurochemically defined populations, such as hypothalamic TH-expressing neurons, can be further sorted into transcriptionally distinct subgroups (Romanov et al., 2017). Gene expression-based cluster analysis is a powerful tool for identifying subpopulations within seemingly homogeneous cell groups (Romanov et al., 2017). However, it is necessary for these transcriptomic studies to be supported and framed by accurate structural information (Crosetto, Bienko, & van Oudenaarden, 2015; Khan et al., 2018). Consideration of basic properties, such as morphology, connectivity, and spatial distributions can reveal groupings (Bota & Swanson, 2007), which would likely remain undetected by high-throughput transcriptomic analyses alone. Indeed, for the hypothalamus, most published transcriptomic and proteomic analyses have ignored cytoarchitectonic boundary conditions of the diverse gray matter regions in this structure, opting instead to report gene expression patterns from the whole hypothalamus (Khan et al., 2018).

We therefore examined the spatial distributions of hypothalamic TH neurons and quantified the extent of their colocalization with other neurotransmitters or neuropeptides. We first determined whether hypothalamic TH-ir neurons may be either GABAergic or glutamatergic. By combining multi-label immunohistochemistry and enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) reporter expression with cytoarchitectural analysis to obtain high spatial resolution maps of TH-ir neuronal subpopulations, we found that most hypothalamic TH-ir neurons coexpressed EGFP reporter expression for the vesicular GABA transporter (EGFPVgat), and that this colocalization was especially prevalent within a specific region of the rostral ZI. We further characterized the neurochemical identity of ZI EGFPVgat TH-ir neurons and showed that these are dopamine-containing neurons, and that they do not appear to colocalize with known neuropeptides in the ZI region.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

All animal care and experimental procedures were completed in accordance with the guidelines and approval of the Animal Care Committee at Carleton University. Mice were housed in ambient temperature (22–24°C) with a 12:12 light dark cycle with ad libitum access to water and standard mouse chow (Teklad Global Diets 2014, Envigo, Mississauga, Canada).

2.1. Generation of Vgat-cre;L10-Egfp and Vglut2-cre;L10-Egfp mice

To visualize GABAergic and glutamatergic neurons, respectively, we labeled neurons expressing the vesicular GABA transporter (vGAT; Slc32a1) or vesicular glutamate transporter 2 (vGlut2; Slc17a6) with an EGFP reporter by crossing a Vgat-ires-cre (Stock 028862, Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) or Vglut2-ires-cre mouse (Stock No. 16963, Jackson Laboratory) with a Cre-dependent lox-STOP-lox-L10-Egfp reporter mouse (Krashes et al., 2014), kindly provided by Dr. B. B. Lowell (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA) to produce Vgat-cre;L10-Egfp and Vglut2-cre;L10-Egfp mice.

2.2. Antibody characterization

Table 1 lists the following primary antibodies we used for immunohistochemistry (IHC).

Table 1.

List and details of primary antibodies

| Antibody | Immunogen | Clonality, Isotype | Source, Catalogue no., Lot no. | RRID | Titer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sheep anti-DIG | Isolated from sheep immunized with DIG steroid molecule | Polyclonal, IgG | Roche, 11207733910, 28557000 | AB_514500 | 1:100 |

| Goat anti-dopamine | Dopamine-glutaraldehyde-thyroglobulin conjugate | Polyclonal, IgG | Dr. H. W. M. Steinbusch, Maastricht University | N/A | 1:2,000 |

| Rabbit anti-DBH | Purified enzyme from bovine adrenal medulla | Polyclonal, IgG | Immunostar, 22806, 1233001 | AB_572229 | 1:5,000 |

| Chicken anti-GFP | His-tagged GFP isolated from Aequorea victoria | Polyclonal, IgY | Millipore, 06–896, 3022861 | AB_11214044 1:2,000 | |

| Rabbit anti-GFP | Isolated from Aequorea victoria | Polyclonal, IgG | Invitrogen, A6455, 52630A | AB_221570 | 1:1,000 |

| Rabbit anti-MCH | Full length MCH peptide | Polyclonal,| IgG | Dr. E. Maratos-Flier, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center |

AB_2314774 | 1:5,000 |

| Goat anti-orexin-A | Amino acid residue 48–66 at C-terminus of human orexin precursor | Polyclonal, IgG | Santa Cruz, sc-8070, J2414 | AB_653610 | 1:4,000 |

| Mouse anti-TH | Purified from N-terminus of PC12 cells | Monoclonal, IgG | Millipore, MAB318, 2677893 | AB_2201528 | 1:2,000 |

DIG, digoxigenin; DBH, dopamine beta-hydroxylase; GFP, green fluorescent protein; MCH, melanin-concentrating hormone; TH, tyrosine hydroxylase.

Sheep anti-digoxigenin (DIG) antibody.

When compared to tissue incubated with a DIG-labeled riboprobe followed with the anti-DIG antibody, no hybridization signals were detected when the tissue was incubated with the anti-DIG antibody only (Vazdarjanova et al., 2006).

Goat anti-dopamine antibody.

The polyclonal anti-dopamine antibody was made and generously provided by Prof. H. W. M. Steinbusch (Maastricht University, Maastricht, Netherlands). Specificity was determined through a gelatin model system and nitrocellulose sheets. The anti-dopamine antibody showed immunoreactivity to even low concentrations of dopamine, with cross-reactivity of less than 10% to noradrenaline, less than 1% to other monoamines, and low levels of cross-reactivity to L-DOPA at higher concentrations (Steinbusch, van Vliet, Bol, & de Vente, 1991).

Rabbit anti-dopamine β-hydroxylase (DBH).

Specificity was determined by the absence of staining when the antibody was preadsorbed by the DBH peptide (Sockman & Salvante, 2008). The distribution of DBH immunoreactivity was confirmed in the locus coeruleus (data not shown), a region known to express DBH, as previously shown (Yamaguchi, Hopf, Li, & de Lecea, 2018). This antibody has also been reported to reveal a distribution of hindbrain DBH-immunoreactive neurons that is similar to that revealed by a DBH antibody of different origin (Halliday & McLachlan, 1991).

Chicken anti-GFP antibody.

Wild type brain tissue does not endogenously express the GFP transgene and incubating wild type brain tissue with this antibody did not produce any GFP-ir signals (data not shown).

Rabbit anti-GFP antibody.

Specificity was determined by the absence of GFP immunoreactivity in the brain of wild type Drosophila melanogaster, which does not endogenously produce endogenous GFP molecules (Busch, Selcho, Ito, & Tanimoto, 2009).

Rabbit anti-melanin-concentrating hormone (MCH) antibody.

The polyclonal anti-MCH antibody was made and generously provided by Dr. E. Maratos-Flier (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA). Specificity was determined by the lack of MCH immunoreactivity after preadsorption with MCH peptide (Elias et al., 1998) or after application to brain tissue from MCH knockout mice (Chee, Pissios, & Maratos-Flier, 2013).

Goat anti-orexin-A antibody.

Specificity was demonstrated by preadsorption with orexin peptide, which abolished all specific staining shown with this antibody (Florenzano et al., 2006).

Mouse anti-tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) antibody.

This antibody recognizes a single 62 kDa band that corresponds to the molecular weight of TH in Western blots of TH isolated from synaptosomal preparations (Wolf & Kapatos, 1989), brain homogenates (Carrera, Anadón, & Rodríguez-Moldes, 2012), or micropunches from frozen brain tissue sections (Shepard, Chuang, Shaham, & Morales, 2006). This antibody did not detect TH immunoreactivity following unilateral lesion of the compact part of the substantia nigra with 6-hydroxydopamine (Bourdy et al., 2014; Chung, Chen, Chan, & Yung, 2008) or ventral tegmental area with ibotenic acid (Bourdy et al., 2014) compared to the control, non-lesioned side. Knockdown of th1 gene that encodes Th in the central nervous system of the zebrafish reportedly abolished detectable immunoreactivity from this antibody (Kuscha, Barreiro-Iglesias, Becker, & Becker, 2012).

All secondary antibodies (Table 2) were raised in donkey against the species of the conjugated primary antisera (mouse, goat, rabbit, or sheep).

Table 2.

List and details of secondary antibodies

| Antibody | Isotype | Source, Catalogue no., Lot no. | RRID | Titer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AffiniPure donkey anti-chicken Alexa Fluor 488 |

IgY (H+L) |

Jackson ImmunoResearch, 703–545-155, 139424 |

AB_2340375 | 1:500 |

| AffiniPure donkey anti-goat Alexa Fluor 488 |

IgG (H+L) |

Jackson ImmunoResearch, 705–545-147, 103943 |

AB_2336933 | 1:500 |

| AffiniPure donkey anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 |

IgG (H+L) |

Jackson ImmunoResearch, 711–545-152, 125719 |

AB_2313584 | 1:200 |

| Donkey anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 |

IgG (H+L) |

Thermo Fisher Scientific, A-21206, 19107512 |

AB_141708 | 1:500 |

| Donkey anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 568 |

IgG (H+L) |

Thermo Fisher Scientific, A-10037, 1827879 |

AB_2534013 | 1:500 |

| Donkey anti-goat Alexa Fluor 647 |

IgG (H+L) |

Thermo Fisher Scientific, A-21447, 1977345 |

AB_2535864 | 1:500 |

| Donkey anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 647 |

IgG (H+L) |

Thermo Fisher Scientific, A-31573, 1903516 |

AB_2536183 | 1:300 |

2.3. Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

2.3.1. Tissue processing

Male and female Vgat-cre;L10-Egfp, Vglut2-cre;L10-Egfp, and wild type mice on a mixed C57BL/6, FVB, and 129S6 background (8–15 weeks old) were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal (ip) injection of urethane (1.6 g/kg) and transcardially perfused with cold (4°C) 0.9% saline followed by 10% neutral buffered formalin (4°C), unless indicated otherwise. The brain was removed from the skull, post-fixed with 10% formalin for 24 hours at 4°C, and then cryoprotected in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4, 0.01 M) containing 20% sucrose and 0.05% sodium azide for 24 hours at 4°C. Brains were cut into four or five series of 30 μm-thick coronal-plane sections using a freezing microtome (Leica SM2000R, Nussloch, Germany) and stored in an antifreeze solution containing 50% formalin, 20% glycerol, and 30% ethylene glycol.

To examine dopamine immunoreactivity, Vgat-cre;L10-Egfp brains were perfused with cold (4°C) saline and then 1% glutaraldehyde:9% formalin mixture (4°C). The brains were post-fixed in the perfusion solution for 30 minutes and cryoprotected with 30% sucrose solution for 24 hours (4°C). Brains were cut into five series of 30 μm-thick sections and collected into a PBS-azide solution containing 1% formalin. All aforementioned perfusion and incubation solutions contained 1% sodium metabisulfite to prevent the oxidation of dopamine.

2.3.2. Procedure

Single- and dual-label IHC were completed as previously described (Chee et al., 2013), unless indicated otherwise, using the antibodies and dilution combinations listed in Tables 1 and 2. In brief, brain tissue sections were washed with six 5-minute PBS exchanges and then blocked for 2 hours at room temperature (RT, 20–21 °C) with 3% normal donkey serum (NDS; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc., West Grove, PA) dissolved in PBS-azide containing 0.25% Triton X-100 (PBT-azide). Unless indicated otherwise, primary antibodies were concurrently added to the blocking serum and incubated with the brain sections overnight (16–18 hours, RT). After washing with six 5-minute PBS rinses, the appropriate secondary antibodies were diluted in PBT containing 3% NDS and applied to the brain tissue sections for 2 hours (RT). The sections were rinsed with three 10-minute PBS washes before being mounted on SuperFrost Plus glass microscope slides (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) and coverslipped (#1.5 thickness) using ProLong Gold antifade reagent containing DAPI (Fisher Scientific).

To examine dopamine immunoreactivity, Vgat-cre;L10-Egfp brain tissues were incubated in PBS containing 0.5% sodium borohydride for 30 minutes at RT, followed by six 5-minute washes in PBS. The brain sections were then blocked with 3% NDS in PBT-azide for 2 hours prior to the simultaneous overnight-incubation (RT) of primary antibodies against GFP (anti-chicken) and TH, then washed with six 5-minute exchanges in PBS, and incubated with the corresponding Alexa Fluor 488- and Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated secondary antibodies in 3% NDS for 2 hours. After three 10-minute PBS rinses of the tissue sections, we diluted the dopamine primary antibody into a 3% NDS, PBT-azide solution and incubated the sections in this solution overnight at RT. The sections were rinsed with PBS six times for 5 minutes each before incubating them with the corresponding Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated secondary antibody in 3% NDS-PBT. Following three 10-minute washes in PBS, the brain sections were mounted and coverslipped. All solutions used to process the visualization of dopamine immunoreactivity contained 1% sodium metabisulfite to prevent the oxidation of dopamine.

2.4. Dual fluorescence in situ hybridization (fISH) and IHC

2.4.1. Tissue preparation for fISH

Vgat-cre;L10-Egfp mice were anesthetized with urethane (1.6 g/kg, ip), and their brains were rapidly removed and snap-frozen on powdered dry ice. The brains were thawed to −16°C and sliced into ten series of 16 μm-thick coronal sections through the entire hypothalamus using a cryostat (CM3050 S, Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL). Each section was thaw-mounted on Superfrost Plus slides (Fisher Scientific), air-dried at RT, and then stored at −80°C until processed for fISH.

2.4.2. fISH and IHC procedure

The antisense vGAT riboprobe corresponds to nucleotide 875–1,416 of mouse Slc32a1 mRNA (Vgat; NM_009508.2) (Agostinelli et al., 2017). Using a plasmid linearized with SacI (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA), it was transcribed with T7 polymerase (Promega, Madison, WI) in the presence of digoxigenin (DIG)-conjugated UTP (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany).

fISH for Vgat mRNA was performed according to the protocol previously described for fresh frozen sections (Wittmann, Hrabovszky, & Lechan, 2013). In brief, prior to hybridization, the sections were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 minutes and rinsed with two 3-minute PBS washes; acetylated with 0.25% acetic anhydride in 0.1 M triethanolamine and rinsed with two PBS washes; then dehydrated in an ethanol gradient starting from 80%, 95%, to 100% for 1 minute each, chloroform for 10 minutes, and again in 100% and 95% ethanol for 1 minute each. The riboprobe (650 pg/μl) was mixed with hybridization buffer containing 50% formamide, 2× sodium citrate buffer (SSC), 1× Denhardt’s solution (MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA), 0.25 M Tris buffer (pH 8.0), 10% dextran sulfate, 3.5% dithiothreitol, 265 μg/ml denatured salmon sperm DNA (MilliporeSigma), and applied directly to each slide under a plastic Fisherbrand coverslip (Fisher Scientific). Hybridization occurred overnight at 56°C in humidity chambers. Following hybridization, we removed the coverslip and the sections were washed in 1× SSC for 15 minutes; treated with 25 μg/ml RNase A (MilliporeSigma) dissolved in 0.5 M NaCl, 10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA (pH 8.0) for 1 hour (37°C); sequentially washed at 65°C with 1× SSC for 15 minutes, 0.5× SSC for 15 minutes, and 0.1× SSC for 1 hour. Subsequently, the sections were treated with PBS containing 0.5% Triton X-100 and 0.5% H2O2 (pH 7.4) for 15 minutes, rinsed in three 10-minute PBS washes, then immersed in 0.1 M maleate buffer (pH 7.5) for 10 minutes before blocking in 1% Blocking Reagent (Roche) for 10 minutes. The sections were incubated in horseradish peroxidase-conjugated, sheep anti-DIG antibody in blocking reagent and enclosed over sections with a CoverWell incubation chamber (Grace Bio-Labs Inc., Bend, OR) overnight at 4°C. After rinsing with three 10-minute PBS washes, the hybridization signal was amplified with a TSA Plus Biotin Kit (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA), by diluting the TSA Plus biotin reagent (1:400) in 0.05 M Tris (pH 7.6) containing 0.01% H2O2, for 30 minutes. The sections were incubated with streptavidin-conjugated Alexa Fluor 555 (1:500; S32355, Invitrogen; RRID: AB_2571525) in 1% Blocking Reagent for 2 hours (RT) to label the Vgat mRNA hybridization signal.

Following fISH, we processed the sections for immunofluorescence by incubating them with a GFP (rabbit) antibody, rinsing with three 10-minute PBS washes, and labeling with an Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary (Table 2). Finally, the sections were washed in PBS and coverslipped with Vectashield mounting medium containing DAPI (H-1200, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA).

2.5. Nissl staining

Free-floating brain sections were mounted onto dust-free gelatin-coated slides and air dried overnight at RT. Sections were dehydrated using ascending concentrations of ethanol (50%, 70%, 95%, and 3× 100% for 3 minutes each) and delipidized in mixed-isomer xylenes for 25 minutes. Sections were then rehydrated in decreasing concentrations of ethanol (100%, 95%, 70%, and 50% for 3 minutes each) and rinsed with distilled water (3 minutes) before staining with 0.25% w/v solution of the thiazine dye, thionine (Kiernan, 2001), made from thionin acetate (Lenhossék, 1895) (861340, MilliporeSigma; pH 4.5, RT) for 30 seconds. Immediately after thionine staining, the sections were rinsed in water; differentiated with 0.4% glacial acetic acid in deionized water by dipping the slides for up to one minute until the gray and white matter were distinguished clearly from each other; then dehydrated in ascending concentrations of ethanol (50%, 70%, 95%, and 3× 100% for 3 minutes each). The brain tissue sections were cleared in mixed-isomer xylenes for 25 minutes, and the slides were coverslipped with DPX Mountant (Millipore Sigma).

2.6. Microscopy

All images were exported as TIFF files into Adobe Illustrator CS4 (Adobe Systems Inc., San Jose, CA) for assembly into multi-panel figures and to add text labels and arrowheads.

2.6.1. Epifluorescence imaging

Images showing the colocalization between Vgat mRNA and GFP-ir in Vgat-cre;L10-Egfp tissue were captured using a Zeiss Axioplan 2 microscope (Carl Zeiss Inc., Göttingen, Germany) equipped with a RT SPOT digital camera (Diagnostic Instruments, Sterling Heights, MI). Adobe Photoshop CS4 (Adobe) was used to create composite images and to modify brightness or contrast to increase the visibility of lower level signals.

Large field-of-view images of whole brain sections were acquired with a fully motorized Nikon Ti2 inverted microscope (Nikon Instruments Inc., Mississauga, Canada) mounted with a Prime 95B CMOS camera (Photometrics, Tucson, AZ) using a CF160 Plan Apochromat ×20 objective lens (0.75 numerical aperture). Images were stitched using NIS Elements software (Nikon), which was also used to adjust image brightness and contrast.

2.6.2. Confocal imaging

High-magnification confocal stacks (2048 × 2048 pixels) involving two- or three-color fluorescence channels were viewed using a Nikon C2 confocal microscope fitted with Plan Apochromat ×20 (0.75 numerical aperture) or ×40 (0.95 numerical aperture) objective lenses and acquired using NIS Elements software (Nikon). The excitation light was provided by 488-nm, 561-nm, and 640-nm wavelength lasers for the visualization of Alexa Fluor 488, Alexa Fluor 568, and Alexa Fluor 647, respectively. We used NIS Elements to stitch overlapping frames, flatten confocal stacks by maximum intensity projection, and adjust the brightness or contrast of flattened images. Two-color images were coded in green (Alexa Fluor 488) and pseudo-colored magenta (Alexa Fluor 568). Three-color images were coded in green (Alexa Fluor 488), red (Alexa Fluor 568), and pseudo-colored light blue (Alexa Fluor 647).

2.7. Nissl-based parcellations, plane-of-section analysis, and atlas-based mapping

An Olympus BX53 microscope (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) was used to examine Nissl-stained tissue sections. Photomicrographs were produced with an Olympus DP74 color camera powered by CellSens Dimension software (Version 2.3). Contrast enhancements and brightness adjustments were made with Photoshop (Version CS6; Adobe) before analyses. Photomicrographs of Nissl-stained tissue were imported to Adobe Illustrator (Version CC 2014, Adobe) and regional boundaries were drawn on a separate data layer. Line parcellations were made using the nomenclature and boundary definitions of the Allen Reference Atlas (ARA; Dong, 2008). To the extent that was applicable, cytoarchitectural criteria outlined in Swanson’s rat brain atlas (Swanson, 2018) were also used to clarify delineations. Parcellations were then carefully superimposed on corresponding fluorescence images to precisely reveal the spatial distributions of TH- and vGAT-ir neurons. We photographed fluorescently-immunostained tissue sections using a Zeiss Axio Imager M.2 microscope (Carl Zeiss Corporation, Thornwood, NY) using ×10 (0.3 numerical aperture) and ×20 (0.8 numerical aperture) Plan Apochromat objective lenses. An EXi Blue monochrome camera (Teledyne Qimaging, Inc., Surrey, British Columbia, Canada) was used to capture multi-channel fluorescence images and a motorized stage controlled by Volocity Software (Version 6.1.1; Quorum Technologies, Inc., Puslinch, Ontario, Canada) aided in generating stitched mosaic images. Image files were then exported in TIFF format to allow further processing using Adobe Photoshop.

Using the parcellations that were superimposed onto the corresponding epifluorescence image, cells that existed within the parcellated boundaries were marked using the Blob Brush tool in Adobe Illustrator. A red circle represented a TH-positive cell, and a blue circle represented a TH- and vGAT-positive cell. Plane-of-section analysis (Zséli et al., 2016) was performed to assign each photographed tissue section or portion thereof to the appropriate ARA reference atlas level(s). The cell representations were then superimposed onto the corresponding ARA reference atlas template (Dong, 2008) for each atlas level, thus creating atlas-based maps of the tissue of interest.

2.8. Cell counting

The numbers of cells counted from the procedures below are semi-quantitative measures meant to provide data for relative comparisons rather than absolute cell numbers within the hypothalamus.

2.8.1. Quantification of Vgat hybridization signals

We acquired stitched epifluorescence images for whole hypothalamic sections using a ×10 objective on a fully motorized Olympus BX61VS microscope running VS-ASW-FL software (Olympus). We viewed the images offline using OlyVIA software (Olympus) in order to quantify the colocalization of Vgat hybridization signals, which expressed red fluorescence, in GFP-ir neurons from Vgat-cre;L10-Egfp brain tissue. Cells were counted using a grid comprising 1-inch × 1-inch squares that was printed on a transparency such that each square, when overlaid onto the magnified image on the computer screen, encompassed a 2.4-mm2 area of the hypothalamus. We counted from one hemisphere and placed the first counting square starting at the ventral edge of the base of the brain, i.e., at the median eminence, then working up to 1.7 mm dorsally (or until the ventral edge of the thalamus where no GFP-ir neurons were observed) and up to 1.4 mm laterally and away from the third ventricle until the cerebral peduncle. We counted the total number of GFP-ir neurons from every brain section within one series (out of 10), as prepared in Section 2.4.1. To avoid double-counting, cells that landed on the gridlines were not included in the count.

We applied the Abercrombie formula to correct for oversampling error (Abercrombie, 1946) in our total cell count using the equation P = A(M/(L+M)) where P is the corrected cell count reported; A is the original cell count; M is the mean tissue thickness; and L is the mean cell diameter (in μm). We determined the tissue thickness following tissue processing by confocal imaging using the ×40 objective, and the mean tissue thickness from this experiment was 11 μm. The diameter of each of 100 neurons throughout the hypothalamus of Vgat-cre;L10-Egfp brain tissue was determined by calculating the mean length of two perpendicular line vectors placed across the soma of each neuron using NIS Elements (Nikon); the mean cell diameter is 12.7 μm. The percentage of colocalization was calculated by determining the total number of Vgat mRNA neurons relative to the total number of GFP-ir neurons in the whole hypothalamus of one brain.

2.8.2. Quantification of EGFPVgat or EGFPVglut2 fluorescence and TH immunoreactivity

We acquired stitched epifluorescence images using a ×10 objective (0.3 numerical aperture) on an Olympus BX53 microscope mounted with the Olympus DP74 camera, and mean cell counts were determined using Adobe Illustrator CS5 (Adobe) across three brains. In every brain section within one series (out of five), as prepared in Section 2.3.1, we counted all neurons displaying TH immunoreactivity, which exhibited red fluorescence, and determined the proportion of these neurons that also displayed EGFPVgat or EGFPVglut2 fluorescence.

We applied the Abercrombie correction for oversampling as described in Section 2.8.1. The mean tissue thickness for this experiment was 20 μm. The mean cell diameter was determined from 3–6 TH-ir neurons from Vgat-cre;L10-Egfp brain tissue within each parcellated region of the hypothalamus. The mean cell diameter used for applying the Abercrombie correction factor for that region ranged between 9.3 μm and 16.4 μm. The values reported reflect the corrected mean number of neurons counted in each region. The percentage of colocalization was calculated with respect to the parcellation-based cytoarchitectural boundaries and only the neurons that fell within the defined boundaries were counted, unless indicated otherwise in the Results.

2.9. Statistics

Line of best-fit for linear regressions was determined using Prism 6.07 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA). All frequency distribution histograms were generated with Prism. All data are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Catecholaminergic neurons in the hypothalamus may be GABAergic

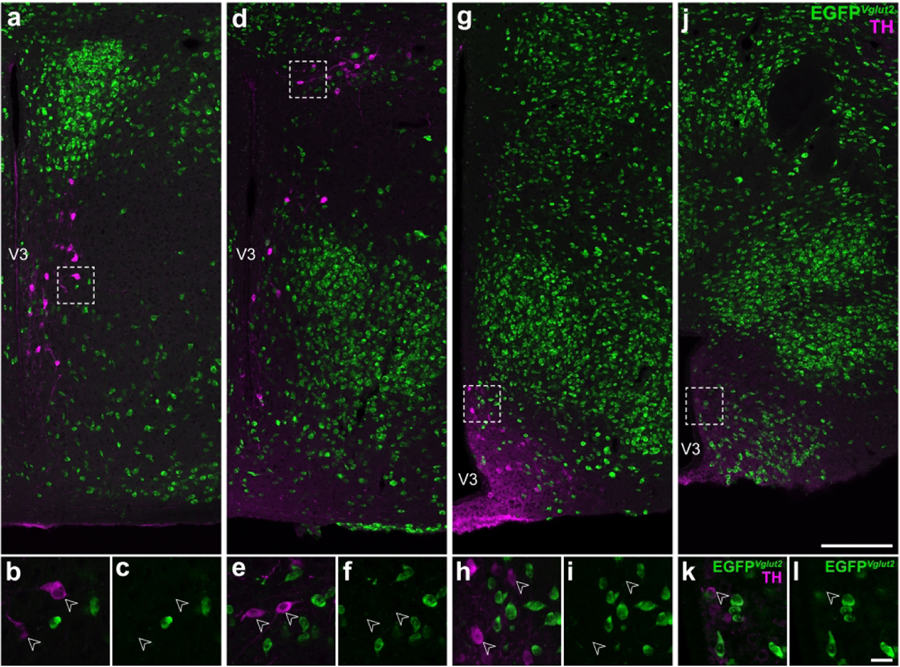

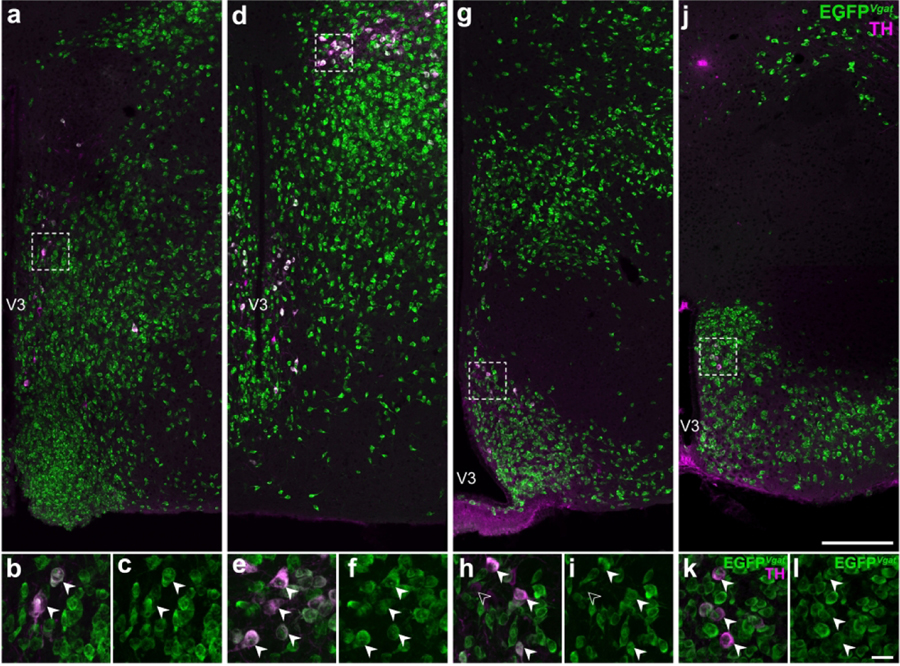

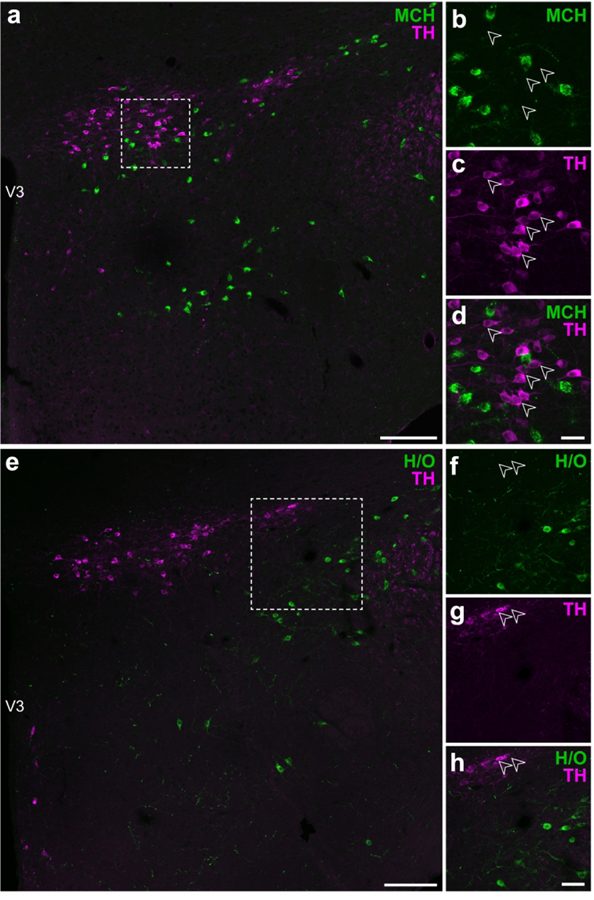

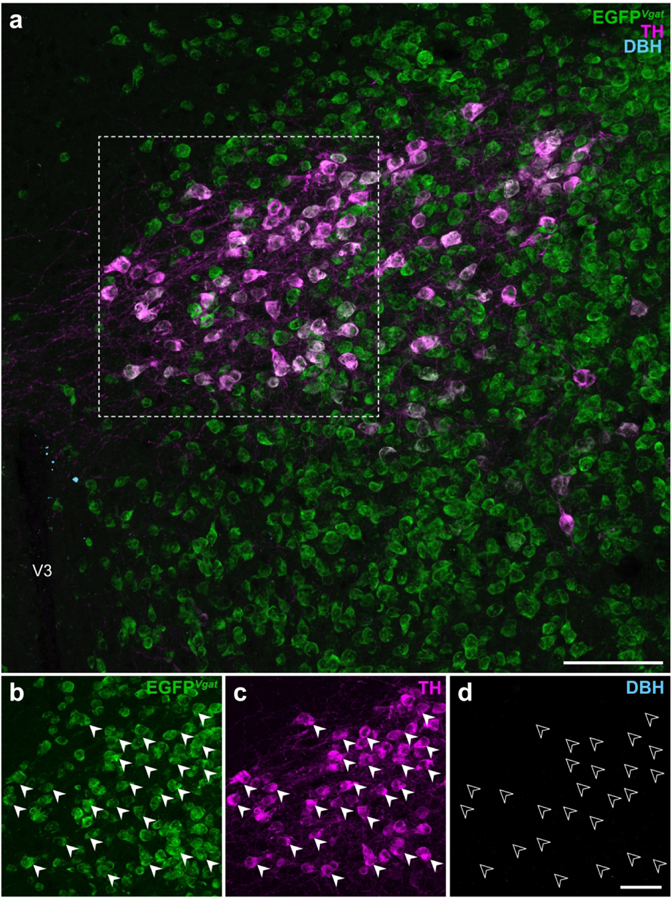

Catecholaminergic neurons are distributed throughout the hypothalamus (A Björklund & Lindvall, 1984; Dahlström & Fuxe, 1964; Hökfelt et al., 1976; Ruggiero et al., 1984; van den Pol et al., 1984), and we determined if they may coexpress the neurotransmitter glutamate or GABA, which can be marked by their expression of vGLUT2 or vGAT, respectively. We therefore examined if TH-ir neurons in Vglut2-cre;L10-Egfp and Vgat-cre;L10-Egfp mouse brain tissue, respectively, also express native EGFP fluorescence (EGFPVglut2 or EGFPVgat). Interestingly, we did not observe any colocalization between TH-ir and EGFPVglut2 neurons from the hypothalamus (Figure 1); in contrast, colocalization between TH-ir and EGFPVgat was readily evident (Figure 2). These observations suggested that hypothalamic TH-ir neurons may be GABAergic.

Figure 1. Hypothalamic TH-expressing neurons do not colocalize with EGFPVglut2 fluorescence.

Representative stitched confocal photomicrographs showing the medial hypothalamic zone within 600 μm of the third ventricle (V3) in Vglut2-cre;L10-Egfp mice at the inferred anteroposterior positions (in mm) from Bregma: −0.5 (a), −1.3 (d), −1.6 (g), and −2.2 (j). Merged-channel confocal photomicrographs (b, e, h, k) from the respective outlined areas (from a, d, g, j) indicate that TH-ir neurons (open arrowheads) do not express EGFPVglut2 (green; c, f, i, l). Scale bars: 200 μm in j also applies to a, d, g; 20 μm in l also applies to b, c, e, f, h, i, k. Label in j applies to a, d, g; k applies to b, e, h; l applies to c, f, i. V3, third ventricle.

Figure 2. Some hypothalamic TH-expressing neurons colocalize with EGFPVgat fluorescence.

Representative stitched confocal photomicrographs showing the medial hypothalamic zone within 600 μm of the third ventricle (V3) in Vgat-cre;L10-Egfp mice at the inferred anteroposterior positions (in mm) from Bregma: −0.5 (a), −1.3 (d), −1.6 (g), and −2.2 (j). Merged-channel confocal photomicrographs (b, e, h, k) from the respective outlined areas in (a, d, g, j) indicate that the vast majority of TH-ir neurons (filled arrowheads) coexpress EGFPVgat (green; c, f, i, l). Open arrowheads (h, i) mark TH-ir neurons that do not coexpress EGFPVgat. Scale bars: 200 μm in j also applies to a, d, g; 20 μm in l also applies to b, c, e, f, h, i, k. Label in j applies to a, d, g; k applies to b, e, h; l applies to c, f, i. V3, third ventricle.

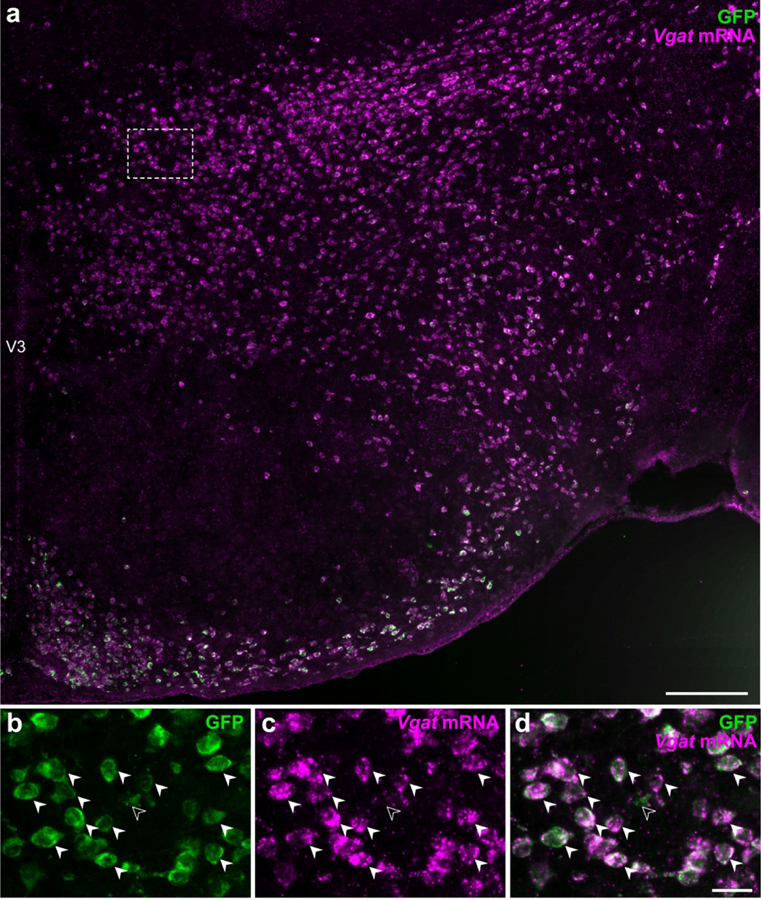

We evaluated the efficacy and specificity of native EGFP fluorescence to indicate vGAT-expressing neurons in Vgat-cre;L10-Egfp mice by assessing the colocalization of Vgat mRNA hybridization signal (Vgat-ISH) in EGFPVgat neurons labeled with an anti-GFP antibody to identify GFP immunoreactivity (Figure 3). We counted GFP-ir neurons from one hemisphere of the hypothalamus and found that more than 99% of GFP-ir neurons (8,855 out of 8,906) expressed Vgat-ISH signals. Thus, EGFPVgat-positive neurons have nearly complete one-to-one correspondence with Vgat-ISH signal in the hypothalamus. Furthermore, less than 1% of the Vgat-ISH neurons (64 out of 8,919) counted were not GFP-ir in the hypothalamus, so the likelihood of under-reporting a Vgat-positive neuron was minimal. These findings validated the use of the Vgat-cre;L10-Egfp mouse model for unambiguous detection of EGFPVgat hypothalamic neurons by native EGFP fluorescence.

Figure 3. Visualization of vGAT-expressing neurons by GFP fluorescence.

Epifluorescence photomicrograph showing Vgat mRNA hybridization signals in GFP-ir neurons from Vgat-cre;L10-Egfp mice. High magnification photomicrographs from the outlined area (from a) show that almost all GFP-ir neurons (b) express Vgat mRNA hybridization signal (c) in the merged-channel image (d). Filled arrowheads indicate representative Vgat-ISH and GFP-ir colocalized neurons while open arrowheads point to a GFP-ir neuron that is Vgat-negative. Scale bars: 200 μm (a); 25 μm (b–d). V3, third ventricle.

3.2. Distribution of EGFPVgat TH-ir neurons in the hypothalamus

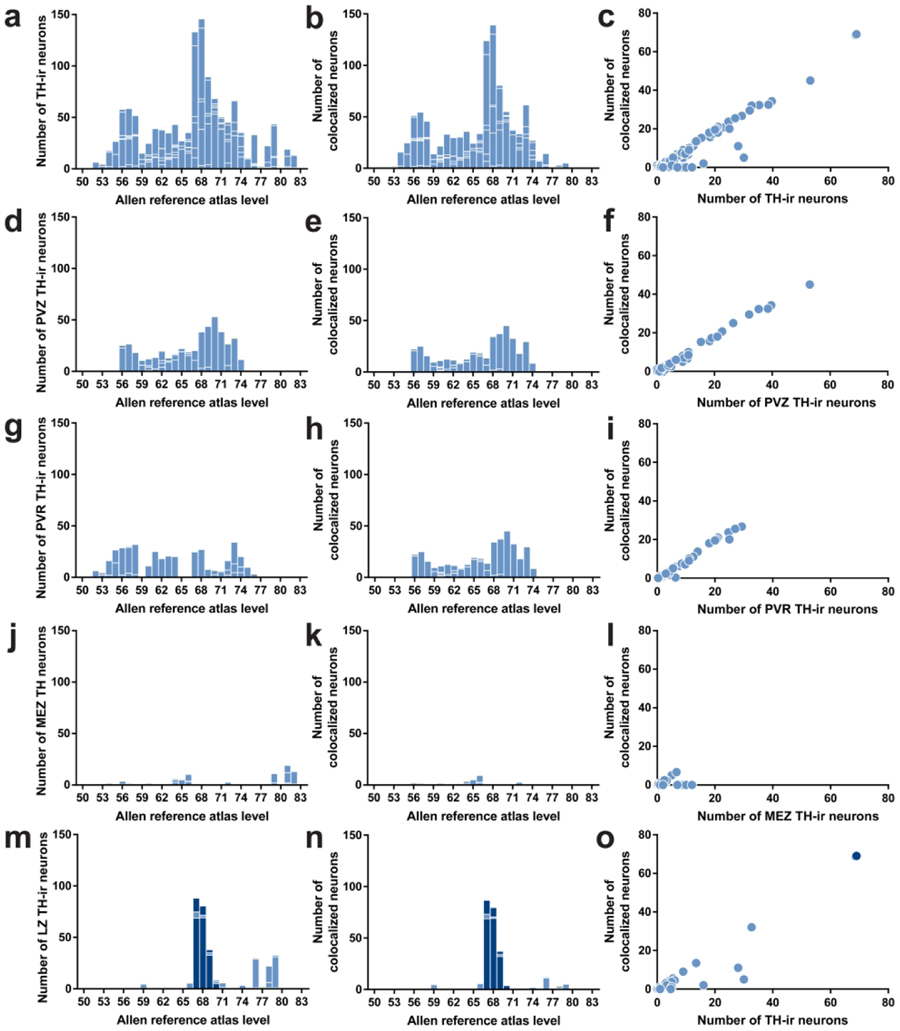

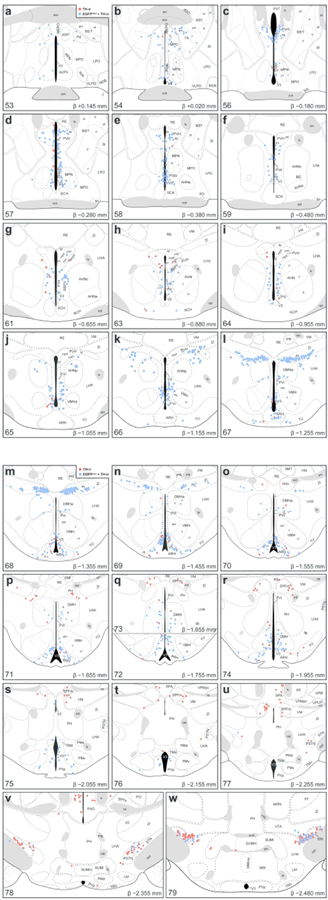

The hypothalamus includes gray matter regions starting rostrally at the level of the anteroventral periventricular nucleus (AVP) and proceeding caudally until the emergence of the ventral tegmental area. In the mouse, the hypothalamus extends approximately 3 mm along the anteroposterior axis (+0.445 to −2.48 mm from Bregma), and this distance is represented across 33 levels (L; L50–L83) in the reference space of the ARA (Dong, 2008). We observed TH-ir neurons throughout the entire rostrocaudal extent of the hypothalamus, where they were dispersed in numerous gray matter regions. We evaluated the distributions of TH-ir neurons across the ARA reference space (Figure 4a), including EGFPVgat TH-ir neurons (Figure 4b). Overall, there was a strong linear relationship between the total number of TH-ir neurons and the number of EGFPVgat TH-ir neurons (r = 0.973, R2 = 0.947; Figure 4c).

Figure 4. Distributions of TH-ir neurons with the colocalization of EGFPVgat in Vgat-cre;L10-Egfp brain tissue.

Number of TH-ir neurons (a, d, g, j, m) that coexpress EGFPVgat (b, e, h, k, n) at each atlas level throughout the whole hypothalamus (a, b), periventricular hypothalamic zone (PVZ; d, e), periventricular hypothalamic region (PVR; g, h), hypothalamic medial zone (MEZ; j, k), and hypothalamic lateral zone (LZ; m, n). Correlation between the coexpression of EGFPVgat in TH-ir neurons at all brain regions in each atlas level of the whole hypothalamus (c), PVZ (f), PVR (i), MEZ (l), and LZ (o). Dark blue bars in m and n and the dark blue filled circles in o correspond to regions within the zona incerta.

In order to increase the spatial resolution for visualizing the distribution of TH-ir neurons in the hypothalamus, we mapped their locations onto ARA atlas templates that are available as electronic vector-object files (Dong, 2008) (Figure 5) and quantified the proportion of EGFPVgat TH-ir neurons in each parcellated gray matter region of the hypothalamus (Table 3). All regions with detectable labeling of TH-ir neurons are tabulated using the hierarchical organization of brain structures presented by the ARA (Allen Institute for Brain Science, 2011b). The colocalization of TH immunoreactivity with EGFPVgat occurred at low (<50%), moderate (50–80%), or high frequencies (>80%) of colocalization.

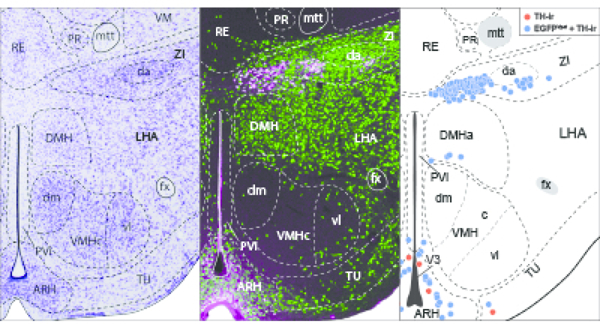

Figure 5. Mapped distributions of EGFPVgat TH-ir neurons in the hypothalamus.

Representative coronal maps, arranged from rostral to caudal order (a–w), show the distributions of TH-ir neurons that colocalize (blue circles) or do not colocalize (red circles) with EGFPVgat from Vgat-cre;L10-Egfp mice. Consultation of Nissl-stained tissue guided the assignment of neurons to parcellated cytoarchitectonic boundaries in the TH-ir tissue, and plane-of-section analysis facilitated their mapping to gray matter regions of the ARA reference atlas templates. Each panel includes a portion of the atlas template for a given ARA level, the numerical designation of the atlas level (bottom left), the corresponding inferred stereotaxic coordinate from Bregma (β; bottom right), and the brain region labels adopted from formal nomenclature of the ARA (Dong, 2008).

Table 3.

Quantification of EGFPVgat-labeled TH-immunoreactive neurons from Vgat-cre;L10-Egfp mouse brain tissue

| Brain region1 | Abbrev.2 | ARA Level3 | Number of neurons4 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TH-ir | EGFPVgat + TH-ir5 | Coloc.6 (%) | |||

| Periventricular zone | |||||

| Supraoptic nucleus | SO | 56–63 | 07 | 0 | |

| Accessory supraoptic group | ASO | n/a8 | n/a | ||

| Paraventricular hypothalamic nucleus | |||||

| Magnocellular division | |||||

| Anterior magnocellular part | PVHam | n/a | n/a | ||

| Medial magnocellular part | PVHmm | 60–65 | 2 ± 1 | 1 ± 1 | |

| Posterior magnocellular part | |||||

| Lateral zone | PVHpml | 60–65 | 0 | 0 | |

| Medial zone | PVHpmm | 63 | 0 | 0 | |

| Parvicellular division | |||||

| Anterior parvicellular part | PVHap | 56–59 | 37 ± 5 | 33 ± 6 | 90 |

| Dorsal zone | PVHmpd | 60–66 | 5 ± 2 | 3 ± 2 | 63 |

| Periventricular part | PVHpv | 56–65 | 3 ± 2 | 2 ± 1 | 60 |

| Periventricular hypothalamic nucleus | |||||

| Anterior part | PVa | 59–61 | 8 ± 4 | 6 ± 4 | 90 |

| Intermediate part | PVi9 | 62–64 | 7 ± 1 | 6 ± 1 | 91 |

| 65–67 | 27 ± 4 | 23 ± 3 | 87 | ||

| 68–74 | 4 ± 2 | 3 ± 1 | 84 | ||

| Arcuate hypothalamic nucleus | ARH9 | 65–67 | 5 ± 3 | 4 ± 3 | 73 |

| 68–71 | 85 ± 18 | 74 ± 16 | 87 | ||

| 72–74 | 27 ± 9 | 23 ± 9 | 88 | ||

| Periventricular region | |||||

| Anteroventral preoptic nucleus | ADP | 51–53 | 0 | 0 | |

| Anterior hypothalamic area | AHA | n/a | n/a | ||

| Anteroventral preoptic nucleus | AVP | 50–54 | 1 ± 1 | 1 ± 1 | |

| Anteroventral periventricular nucleus | AVPV | 51–53 | 5 ± 4 | 1 ± 0 | 13 |

| Dorsomedial nucleus of the hypothalamus | |||||

| Anterior part | DMHa9 | 67–69 | 29 ± 8 | 27 ± 8 | 92 |

| 70–74 | 5 ± 3 | 4 ± 2 | 93 | ||

| Posterior part | DMHp | 70–74 | 11 ± 3 | 9 ± 3 | 81 |

| Ventral part | DMHv | 71–74 | 10 ± 2 | 9 ± 2 | 87 |

| Median preoptic nucleus | MEPO | n/a | n/a | ||

| Medial preoptic area | MPO9 | 50–55 | 9 ± 5 | 9 ± 4 | 98 |

| 56–58 | 4 ± 3 | 3 ± 2 | 73 | ||

| Vascular organ of the lamina terminalis | OV | n/a | n/a | ||

| Posterodorsal preoptic nucleus | PD | 0 | 0 | ||

| Parastrial nucleus | PS | 0 | 0 | ||

| Suprachiasmatic preoptic nucleus | PSCH | n/a | n/a | ||

| Periventricular hypothalamic nucleus | |||||

| Posterior part | PVp | 75–79 | 8 ± 2 | 5 ± 2 | 72 |

| Preoptic part | PVpo | 54–66 | 54 ± 4 | 50 ± 5 | 93 |

| Subparaventricular zone | SBPV | 60–63 | 32 ± 1 | 30 ± 0 | 93 |

| Subfornical organ | SFO | n/a | n/a | ||

| Ventrolateral preoptic nucleus | VLPO | 53–55 | 0 | 0 | |

| Hypothalamic medial zone | |||||

| Anterior hypothalamic nucleus | |||||

| Anterior part | AHNa | 58–64 | 0 | 0 | |

| Central part | AHNc | 59–64 | 1 ± 1 | 1 ± 0 | |

| Dorsal part | AHNd | n/a | n/a | ||

| Posterior part | AHNp | 63–66 | 6 ± 1 | 6 ± 1 | 88 |

| Mammillary body | |||||

| Lateral mammillary nucleus | LM | 78–81 | 0 | 0 | |

| Medial mammillary nucleus | MM | 79–82 | 0 | 0 | |

| Supramammillary nucleus | |||||

| Lateral part | SUMl | 78–82 | 4 ± 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Medial part | SUMm | 78–82 | 6 ± 6 | 0 | 0 |

| Tuberomammillary nucleus | |||||

| Dorsal part | TMd | 75–77 | 0 | 0 | |

| Ventral part | TMv | 77–79 | 0 | 0 | |

| Medial preoptic nucleus | |||||

| Central part | MPNc | 53–55 | 0 | 0 | |

| Lateral part | MPNl | 54–58 | 1 ± 0 | 1 ± 0 | |

| Medial part | MPNm | 54–58 | 3 ± 1 | 1 ± 0 | 57 |

| Dorsal premammillary nucleus | PMd | ||||

| Ventral premammillary nucleus | PMv | ||||

| Paraventricular hypothalamic nucleus, descending | |||||

| Dorsal parvicellular part | PVHdp | 60–65 | 0 | 0 | |

| Forniceal part | PVHf | n/a | n/a | ||

| Lateral parvicellular part | PVHlp | 66 | 4 ± 2 | 4 ± 2 | 95 |

| Medial parvicellular part, ventral | PVHmpv | 64–65 | 0 | 0 | |

| Ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus | |||||

| Anterior part | VMHa | 65–66 | 0 | 0 | |

| Central part | VMHc | 67–73 | 1 ± 1 | 1 ± 1 | |

| Dorsomedial part | VMHdm | 67–71 | 0 | 0 | |

| Ventrolateral part | VMHvl | 66–73 | 0 | 0 | |

| Hypothalamic lateral zone | |||||

| Lateral hypothalamic area | LHA | 59–79 | 15 ± 11 | 6 ± 5 | 37 |

| Lateral preoptic area | LPO | 50–59 | 1 ± 1 | 1 ± 1 | |

| Posterior hypothalamic nucleus | PH | 70–82 | 8 ± 4 | 1 ± 0 | 12 |

| Preparasubthalamic nucleus | PST | n/a | n/a | ||

| Parasubthalamic nucleus | PSTN | 75–78 | 8 ± 5 | 2 ± 1 | 18 |

| Retrochiasmatic area | RCH | n/a | n/a | ||

| Subthalamic nucleus | STN | 75–78 | 8 ± 4 | 2 ± 2 | 30 |

| Tuberal nucleus | TU ZI9 | 65–75 | 8 ± 4 | 3 ± 1 | 43 |

| Zona incerta | 61–66 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 67–69 | 86 ± 19 | 86 ± 18 | 100 | ||

| 70–83 | 4 ± 1 | 2 ± 1 | 57 | ||

| Dopaminergic group | ZIda | 67–69 | 10 ± 5 | 10 ± 5 | 100 |

| Fields of Forel | FF | 78–79 | 1 ± 1 | 0 | |

Organization of brain regions based on hierarchical structure presented by the Allen Reference Atlas (ARA; Allen Institute for Brain Science, 2011).

Nomenclature and atlas level based on the ARA (Dong, 2008).

Each brain region may span several atlas levels.

The total number of tyrosine hydroxylase-immunoreactive (TH-ir) neurons counted bilaterally from parcellated brain regions. Data are reported as mean ± SEM (n = 3 mice), rounded to nearest whole number. Number of neurons reported is corrected for oversampling using the Abercrombie formula P = A(M/(L+M)) (Abercrombie, 1946), where P is the corrected number of neurons counted, A is the original number of neurons counted, M is the mean tissue thickness (20 μm), L is the mean cell diameter (in μm). The cell diameter may vary between each parcellated hypothalamic region, thus a distinct Abercrombie correction factor is applied for each respective region.

Quantification of TH-ir neurons that coexpress native EGFP fluorescence (EGFPVgat) in TH-ir neurons.

Percentage of TH-ir neurons that colocalized (Coloc.) with EGFP-f indicate the proportion of GABAergic TH neurons. No value will be provided if the mean of two or less than two TH-ir neurons was counted.

Parcellated brain regions that did not contain a TH-ir neuron.

Data are not available (n/a) from brain regions that either did not emerge following Nissl-based parcellations or were not parcellated in the ARA.

Distribution of TH-ir neuron within this region revealed noticeable breakpoints or clustering within ARA levels.

3.2.1. The periventricular zone

The TH-ir neurons in the periventricular zone were distributed within three main brain regions: the paraventricular hypothalamic nucleus (PVH), periventricular hypothalamic nucleus (PV), and arcuate hypothalamic nucleus (ARH) (Table 3). These neurons were distributed across L56–L74 and were moderately to highly (63–91%) colocalized with EGFPVgat, which showed a very strong linear relationship with the overall numbers of TH-ir neurons in this zone (r = 0.995, R2 = 0.990; Figure 4d–f).

TH-ir neurons in the PVH were largely confined to its parvicellular division and were most numerous within the anterior parvicellular part (PVHap), and 90% of PVHap TH-ir neurons were EGFPVgat-positive (Table 3; L56–L59; Figure 5c–f). In contrast, the dorsal zone (PVHmpd; Table 3) or periventricular part (PVHpv; L56–59; Figure 5c–f; Table 3) of the parvicellular PVH contained much fewer TH-ir neurons, and 60% and 63% of PVHmpd and PVHpv neurons, respectively, were also EGFPVgat-positive (Table 3).

Most of the TH-ir neurons in the periventricular zone abutted the third ventricle. Within this zone, the entire periventricular hypothalamic nucleus that was mapped extended through 15 atlas levels, including the anterior (PVa) and intermediate (PVi) parts, and 84–90% of TH-ir neurons in this region were also EGFPVgat-positive (L59–74; Figure 5f–r; Table 3). Notably, the middle anteroposterior portion of the PVi (L65–L67) expressed the most EGFPVgat TH-ir neurons (Figure 5j–l). In the ARH, TH-ir neurons were distributed throughout the entire rostrocaudal extent of the structure but were most abundant within the dorsomedial aspect of the ARH at L68–L71 (Figure 5m–p). TH-ir neurons were distributed in varying densities through the ARH along its anteroposterior expanse, and 73–88% of these neurons were also EGFPVgat-positive (Table 3).

3.2.2. The periventricular region

The periventricular region included brain regions across virtually the entire rostrocaudal extent of the hypothalamus, though TH-ir neurons were clustered either toward its rostral (L52–L63) or caudal portions (L67–L76) (Figure 4g–h). Overall, most TH-ir neurons in the periventricular region were also EGFPVgat-positive (r = 0.992, R2 = 0.983; Figure 4i), but we found regional differences at several atlas levels.

Within the rostral periventricular region, TH-ir neurons were most abundant in the preoptic part of the periventricular hypothalamic nucleus (PVpo; L54–58), and 93% of these neurons were also EGFPVgat-positive (Table 3; Figure 5b–e). Colocalized neurons that fell on or immediately outside the parcellated boundaries of PVpo in L57 were provisionally included in the cell counts for PVpo (Figure 5d). There were also notable TH-ir neurons in the subparaventricular zone (SBPV; L60–63) that displayed very high colocalization with EGFPVgat (Table 3; Figure 5g–h). Other areas in the periventricular hypothalamic region contained a few TH-ir neurons in the anteroventral periventricular nucleus (AVPV) and medial preoptic area (MPO). Colocalization of EGFPVgat at TH-ir neurons in the AVPV was low (13%; Table 3; Figure 5a) but moderate to high (73–98%) in the MPO (Table 3; Figure 5b–e).

Within the caudal periventricular region, TH-ir neurons were found in the posterior part of the periventricular hypothalamic nucleus (PVp; L75–79), where 72% of them colocalized with EGFPVgat (Table 3; Figure 5s–w). In the dorsomedial nucleus of the hypothalamus (DMH; Table 3), aside from a small cluster of cells lining the dorsomedial tip of its anterior part (DMHa) at L67 (Figure 5l), TH-ir neurons were sparsely distributed throughout the remaining DMHa (L68–74), as well as the ventral (DMHv; L71–74), and posterior (DMHp; L70–74) parts of the DMH. TH-ir neurons throughout the entire DMH showed between 80–90% colocalization with EGFPVgat (Table 3).

3.2.3. The hypothalamic medial zone

The hypothalamic medial zone rarely contained TH-ir neurons (Figure 4j–k), and overall, there was only a weak correlation between EGFPVgat and TH-ir neurons (r = 0.593, R2 = 0.352; Figure 4l). There were few, if any, TH-ir neurons within the anterior (AHNa) or central (AHNc) parts of the anterior hypothalamic nucleus, but the posterior part (AHNp) contained distinct TH-ir neurons that colocalized with EGFPVgat (Table 3; Figure 5f–k). A few TH-ir neurons resided more caudally in the supramammillary nucleus (SUM) between L78–L82, but none of these neurons colocalized with EGFPVgat (Table 3; Figure 5v, w).

Notably, the PVH, which contained a moderate density of colocalized EGFPVgat and TH-ir neurons within the periventricular zone, only displayed few such neurons within the hypothalamic medial zone (in its descending division), specifically in the lateral parvicellular part (PVHlp) (L66; Figure 5k).

3.2.4. The lateral hypothalamic zone

With the exception of the zona incerta (ZI), which accounted for most of the positive lateral hypothalamic zone TH-ir neurons between L66–69, the brain regions in this zone primarily contained a low density of TH-ir neurons (Figure 4m), but there was a strong correlation between EGFPVgat and TH-ir neurons (r = 0.953, R2 = 0.908). In the anterior region of the lateral hypothalamic zone, the lateral hypothalamic and lateral preoptic areas contained few, if any, TH-ir neurons that colocalized EGFPVgat. Posterior levels of the hypothalamus (L70–82), which include the posterior hypothalamic nucleus (PH), parasubthalamic nucleus (PSTN), subthalamic nucleus (STN), and tuberal nucleus (TU), contained few TH-ir neurons. These regions displayed low (12–43%) colocalization with EGFPVgat (Table 3).

In contrast, we found a high density of TH-ir neurons in the ZI, particularly within L67–L69 (Figure 5l–n), and every TH-ir neuron in this space displayed EGFPVgat (Figure 5k–n). The majority of these TH-ir EGFPVgat neurons lined the ventral edge of the ZI at L67 and clustered within the medial aspect of the ZI at L68. Interestingly, the majority of these neurons resided outside the cytoarchitectural boundaries of a cell group labeled in ARA reference atlas templates (Dong, 2008) as the dopaminergic group within the ZI (ZIda), although those that fell within its boundaries also displayed EGFPVgat (Figure 5l–n).

3.3. Striking distribution pattern of GABAergic TH-ir neurons within the zona incerta

While several hypothalamic regions displayed strong colocalization between TH immunoreactivity and EGFPVgat, the distribution pattern of neurons with such colocalization was the most prominent and specific within the ZI. The ZI is a relatively expansive region that spans 2.33 mm along the rostrocaudal axis of the mouse brain, as represented within the ARA reference space at L61–L83. EGFPVgat colocalized with all TH-ir ZI neurons found from L67 to L69 (Figure 5l–n). The ZI was notable among brain regions because the degree of colocalization of TH-ir neurons with EGFPVgat was the most complete among all brain regions analyzed at each atlas level (see right- and upper-most data points in Figure 4, panels c and o). In contrast, there were very few TH-ir neurons anterior to L67 that were within the cytoarchitectonic boundaries of the ZI (Figure 5g–k), only a few TH-ir ZI neurons that were located between L70–L83 (see Figure 5o–w for L70–79), and only 57% of ZI neurons residing outside L67–L69 colocalized with EGFPVgat (Table 3).

3.4. Neurochemical characterization of EGFPVgat TH-ir neurons

The hypothalamus is enriched by the expression of diverse neuropeptides, including those residing within or surrounding the ZI within the lateral hypothalamic zone, such as MCH and H/O. We performed dual-label IHC reactions for TH and either MCH or H/O, but we could not detect either MCH (Figure 6a–d) or H/O (Figure 6e–h) immunoreactivity with TH-ir neurons.

Figure 6. TH-ir neurons in the ZI do not show detectable MCH or H/O immunoreactivities.

Confocal photomicrographs from the lateral hypothalamic zone of wild type mouse tissue illustrating the distributions of MCH-ir (a–d) and H/O-ir neurons (e–h) relative to TH-ir neurons. Open arrowheads show lack of detectable MCH- (b) or H/O-positive labeling (f) in TH-ir neurons (c, g) in merged-channel, high-magnification photomicrographs (d, h) from the outlined areas in a and e, respectively. Scale bars: 100 μm (a, e); 30 μm (b–d); 50 μm (f–h).

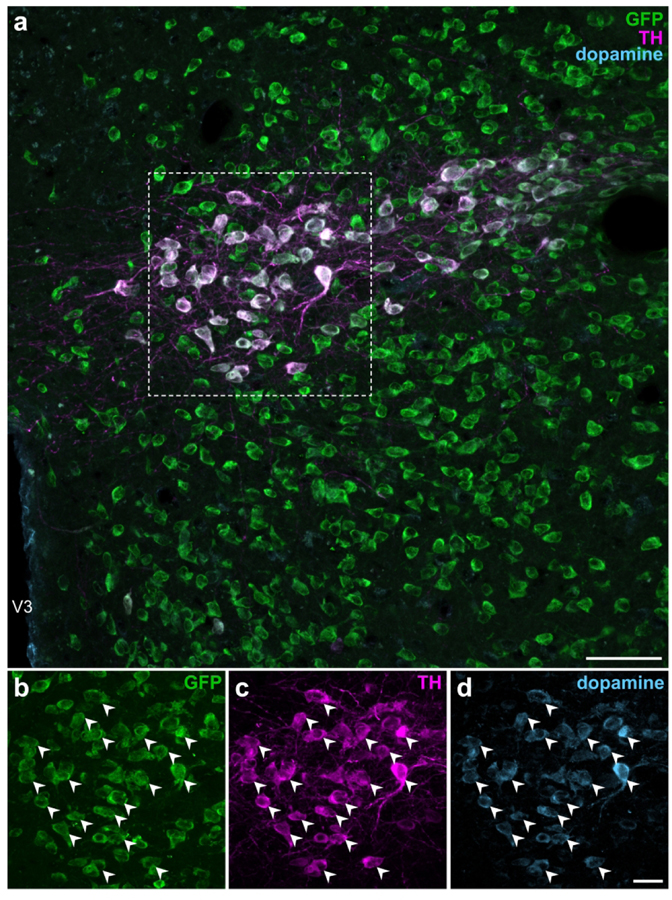

TH is the rate-limiting enzyme for all catecholamine neurotransmitter synthesis (Udenfriend & Wyngaarden, 1956) in mammals and is commonly used as a marker of catecholaminergic neurons. However, it does not further specify the terminal catecholamine (i.e., dopamine, norepinephrine, or epinephrine) synthesized by the neuron. Within the catecholamine biosynthesis pathway, dopamine is hydroxylated by dopamine β-hydroxylase (DBH; EC 1.14.17.1) into norepinephrine which, in turn, can be methylated to become epinephrine. Dual-label IHC for DBH and TH immunoreactivities in Vgat-cre;L10-Egfp tissue did not reveal DBH-ir neurons within the ZI (Figure 7) or any other region of the hypothalamus (data not shown). These results show that TH-ir ZI neurons lack the enzymatic machinery to synthesize norepinephrine, and hence also epinephrine. Therefore, we determined if TH-ir ZI neurons would display immunoreactivity to dopamine. To this end, we performed triple-label IHC for dopamine, TH, and GFP in the ZI of Vgat-cre;L10-Egfp mouse brain tissue and found that almost all GFP-and TH-ir neurons also displayed dopamine immunoreactivity (Figure 8).

Figure 7. EGFPVgat TH-ir neurons in the ZI do not express dopamine β-hydroxylase.

Confocal photomicrographs from the ZI of Vgat-cre;L10-Egfp brain tissue (a) show EGFPVgat (b) in TH-ir neurons (c) but not immunoreactivity for dopamine β-hydroxylase (DBH; d). Filled arrowheads mark a representative sample of EGFPVgat TH-ir neurons (b, c) from the outlined area (a) that do not express DBH, as indicated by open arrowheads (d). Scale bars: 100 μm (a); 50 μm (b–d). V3, third ventricle.

Figure 8. EGFPVgat TH-ir neurons in the ZI contain immunoreactivity for dopamine.

Confocal photomicrographs from the ZI of Vgat-cre;L10-Egfp brain tissue (a) show the colocalization of GFP (b), TH (c), and dopamine (d) immunoreactivities at high magnification within the same neuron. Filled arrowheads indicate representative GFP-, TH-, and dopamine-ir neurons. Scale bars: 50 μm (a); 20 μm (b–d). V3, third ventricle.

4. DISCUSSION

We examined the distribution and neurochemical identity of TH-ir hypothalamic neurons in a transgenic EGFP-reporter mouse line expressing vGAT; portions of these data have been presented in preliminary form (Chee, Negishi, Schumacker, Butler, & Khan, 2017, 2018). First, we found that most hypothalamic TH-ir neurons coexpress vGAT, with the greatest concentration of these neurons located in a portion of the rostral ZI. Second, we found that these rostral ZI coexpressing TH and vGAT display immunoreactivity for dopamine but not for the norepinephrine-synthesizing enzyme DBH. Collectively, the results suggest that rostral ZI neurons synthesize dopamine as their terminal releasable catecholamine and may also release the neurotransmitter GABA. Below, we discuss these results in relation to the known neuroanatomy and neurochemistry of these neurons.

Neuroanatomy.

We mapped the locations of TH-ir neurons onto atlas templates from ARA (Dong, 2008) to provide high-spatial resolution maps of their distribution throughout the mouse hypothalamus. Several hypothalamic regions, including the arcuate and paraventricular hypothalamic nuclei, contained a high density of EGFPVgat TH-ir neurons. Notably, the use of a standardized neuroanatomical framework to visualize and map the distribution of TH-ir neurons onto atlas templates revealed their remarkably specific and robust localization in a discrete portion of the ZI. The ZI spans more than 2.3 mm rostrocaudally, but almost all TH-ir neurons were found to reside specifically within a 0.2 mm-long segment of the ZI between L67–L69. Furthermore, these TH-ir neurons appear to be homogeneous in their neurochemical makeup based on their colocalization of vGAT and dopamine, but not MCH or H/O neuropeptides, or DBH. Together, the evidence in the present study indicates that these neurons likely produce dopamine as their terminal catecholamine in this biosynthetic pathway.

Our Nissl stains in the mouse brain highlight the presence of a compact region within the ZI, which was also labeled ZIda according to ARA nomenclature (Dong, 2008), but it is notable that the observed EGFPVgat TH-ir neurons in our study were medial and ventral to this compact cell group. It has been previously reported that distributions of TH -ir neurons in the ZI may be differentiated by cell diameter (Ruggiero et al., 1984), but we only considered cell location and not cell size in our observations. Commonly used mouse brain atlases (Dong, 2008; Franklin & Paxinos, 2012) make reference to the A13 or dopaminergic cell group of the ZI, respectively, based on cytoarchitectural features. However, given that EGFPVgat TH-ir neurons in the mouse ZI fall outside of the compact region assigned to these labels, the compact cell group in the mouse ZI may only approximate the location of dopaminergic neurons. It is noteworthy that the most recent iteration of the ARA nomenclature and online atlas levels (Allen Institute for Brain Science, 2011a) has removed the cytoarchitectonic boundaries originally assigned in the ZI to the compact A13 region. However, we have used ARA digital reference atlas templates (Dong, 2008), which still contain this region as a discrete structure (ZIda), to map our TH-ir neuronal distributions—as these are, at the time of this writing, the only electronically available vector-object templates for ARA reference space. As subsequent versions of the ARA become available, we hope that accompanying vector-object templates will be available for the community to use to map their datasets.

Neurochemistry.

Although TH immunoreactivity is a useful marker for dopaminergic cell populations, its presence alone is not sufficient to identify these populations, but needs to be considered in relation to the presence or absence of other molecular markers of dopaminergic transmission and/or the specific catecholamine produced by the neurons being examined (A. Björklund & Dunnett, 2007; Tritsch, Granger, & Sabatini, 2016). In the hypothalamus, transcriptomic analysis of neurons in the lateral hypothalamic area has provided evidence in support of the GABAergic and dopaminergic profile of TH neurons, which express genes encoding enzymes to synthesize GABA (Gad1 and Gad2) and dopamine (Ddc and Th), as well as their respective vesicular transporters vGAT (Slc32al) and vMAT2 (Slc18a2) (Mickelsen et al., 2019). ZI TH-ir neurons may transport dopamine into synaptic vesicles, as they also express the vesicular monoamine transporter, vMAT2 (Sharma, Kim, Mayr, Elliott, & Whelan, 2018). Moreover, microspectrofluorometric studies have demonstrated that catecholaminergic ZI neurons in the rat display emission spectra exclusively for dopamine (A Björklund & Nobin, 1973), and our own detection of dopamine immunoreactivity in these neurons supports this observation. Taken together, the presence of TH, dopamine, and vMAT2 in these ZI neurons suggests that these neurons package and release dopamine for neurotransmission. The detection of TH and dopamine immunoreactivity also suggests that these neurons probably express aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC; EC 4.1.1.28) (Lovenberg, Weissbach, & Udenfriend, 1962), which has been shown in ZI neurons of the prairie vole (Ahmed, Northcutt, & Lonstein, 2012), and that both AADC and TH are catalytically active for dopamine synthesis.

Similarly, ZI TH-ir neurons also express glutamate decarboxylase (GAD) to synthesize GABA (Shin et al., 2007) and we show in the present study that all ZI TH-ir neurons express vGAT, which facilitates the transport of GABA into synaptic vesicles (Figures 7, 8). Collectively, these observations show that in addition to dopaminergic neurotransmission, ZI TH-ir neurons also possess the molecular machinery to mediate GABAergic neurotransmission. By contrast, we did not detect the colocalization of TH and EGFPVglut2 in the ZI or elsewhere in the hypothalamus, and while it is possible that hypothalamic TH-ir neurons may harbor an alternative transporter for glutamate, such as Vglut3 (Schäfer, Varoqui, Defamie, Weihe, & Erickson, 2002), the expression of Vglut1 in the hypothalamus has not been reported (Fremeau et al., 2001).

We also did not detect the colocalization of ZI TH-ir neurons with at least two major neuropeptidergic cell groups in the lateral hypothalamic zone. Unlike ZI TH-ir neurons, both MCH and H/O neurons coexpress Vglut2 but not Vgat (Mickelsen et al., 2019) and can release glutamate (Chee et al., 2015; Schöne et al., 2012). In light of recent transcriptomic analysis, we also do not expect that ZI TH neurons would colocalize with another neuropeptide, as they do not show enriched gene expression for neuropeptides such as cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript protein, galanin, neuropeptide W, neuropeptide Y, neurotensin, somatostatin, and tachykinin produced by Vgat-expressing neurons in the lateral hypothalamus (Mickelsen et al., 2019).

We identified GABAergic neurons based on vGAT expression, which we visualized by cre-dependent EGFP expression in Vgat-cre;L10-Egfp neurons. As gross, qualitative comparison of Vgat hybridization signals had shown its expression in expected brain regions (Vong et al., 2011), we performed quantitative analyses to address any possible ectopic EGFP expression at the neuronal level. Nearly all (>99%) EGFPVgat neurons expressed Vgat mRNA, thus confirming robust and accurate labeling of vGAT neurons in the hypothalamus of Vgat-cre;L10-Egfp mice. Furthermore, fewer than 1% of Vgat neurons do not express EGFPVgat, so it is unlikely that there would be a cluster of detectable TH-ir Vgat neurons that is not revealed by colocalization with EGFPVgat. GABA is often reported as a co-transmitter in dopaminergic cells. For example, dopaminergic neurons in the ventral tegmental area may transport GABA and dopamine via vMAT2, thus these two chemical messengers may be co-packaged (Tritsch, Ding, & Sabatini, 2012). However, in the olfactory bulb, GABA and dopamine are not necessarily co-packaged, and they may utilize independent modes of vesicular release that occur over different time courses (Borisovska, Bensen, Chong, & Westbrook, 2013). We are pursuing further neuroanatomical studies to identify the projection targets of ZI TH-ir neurons (Mejia et al., 2019), as well as functional studies to determine if these ostensibly GABAergic and dopaminergic ZI neurons do in fact release GABA and/or dopamine at downstream neurons.

GABAergic neurons within the ZI have recently been shown to modulate the motivational and hedonic aspects of feeding through direct projections to the paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus (PVT) (Zhang & van den Pol, 2017), but it is not known if dopamine also acts at the PVT to stimulate feeding. The PVT receives projections from ZI TH neurons (Li, Shi, & Kirouac, 2014) and expresses D2-subtype dopamine receptors, which are linked to a role for the PVT in drug addiction (Clark et al., 2017). There is at least a foundational basis for dopamine- and GABA-mediated neurotransmission in the PVT, but it remains to be determined if these chemical messengers would exert similar influences upon behavior by acting in the PVT or elsewhere. For instance, another ZI GABAergic pathway targets the periaqueductal gray (PAG) and is implicated in the control of flight and freezing responses (Chou et al., 2018). A neuroanatomical tracing study reported ZI TH-ir neuronal projections to the PAG in rats (Messanvi, Eggens-Meijer, Roozendaal, & van der Want, 2013) allowing for the possibility of a role for dopamine in mediating defensive behaviors.

Our work broadly supports the emerging view that GABA co-transmission is a hallmark of dopaminergic neurons (Tritsch et al., 2016). Overall, we found EGFPVgat signals colocalized in 82% of hypothalamic TH-ir neurons, though some regions showed higher or lower levels of colocalization (Table 3). Outside the ZI, the largest numbers of EGFPVgat TH-ir neurons were distributed through the PVH, PV, and ARH, regions which harbor neurons that project to the pituitary (Ju, Liu, & Tao, 1986) and mediate neurosecretory functions (Markakis & Swanson, 1997). For example, TH-expressing neurons send projections to the median eminence to enable dopamine-mediated inhibition of prolactin release from the anterior pituitary gland (Ben-Jonathan & Hnasko, 2001; Ben-Jonathan, Oliver, Weiner, Mical, & Porter, 1977). Moreover, cells in the anterior pituitary express all GABA receptor subtypes (Anderson & Mitchell, 1986) and GABA administration can also inhibit prolactin release (Grandison & Guidotti, 1979). Thus, in addition to mediating local neurocircuitry to regulate behavior, colocalized GABA and dopamine in neurons could work synergistically to mediate neuroendocrine functions.

Hypothalamic TH-ir neurons in the rat and mouse have been reported since the 1970s (Hökfelt et al., 1976; Hökfelt et al., 1984; Ruggiero et al., 1984; van den Pol et al., 1984), and the present study extends this work by providing high spatial-resolution atlas-based maps of TH-ir neurons in the mouse hypothalamus. Further, this dataset is enriched by defining and mapping the distribution of TH neuron subpopulations that may also be GABAergic. Importantly, these maps constitute a standardized dataset that can be used to derive precise stereotaxic coordinates to target these discrete neuronal subpopulations in functional studies.

Acknowledgments:

This work is supported by NSERC Discovery Grant RGPIN-2017–06272 (MJC), NIH grants GM109817 and GM127251 (AMK), research incentive funds from the UTEP Office of Research and Sponsored Projects (AMK), and funds from an NIH center grant (MD007592) awarded to the Border Biomedical Research Center at UTEP.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Data availability statement: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- Abercrombie M (1946). Estimation of nuclear population from microtome sections. Anat Rec, 94, 239–247. 10.1002/ar.1090940210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agostinelli LJ, Ferrari LL, Mahoney CE, Mochizuki T, Lowell BB, Arrigoni E, & Scammell TE (2017). Descending projections from the basal forebrain to the orexin neurons in mice. J Comp Neurol, 525(7), 1668–1684. 10.1002/cne.24158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed EI, Northcutt KV, & Lonstein JS (2012). L-amino acid decarboxylase- and tyrosine hydroxylase-immunoreactive cells in the extended olfactory amygdala and elsewhere in the adult prairie vole brain. J Chem Neuroanat, 43(1), 76–85. 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2011.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen Institute for Brain Science. (2011a). Allen Mouse Brain Atlas. Retrieved from http://atlas.brain-map.org/

- Allen Institute for Brain Science. (2011b). Technical white paper: Allen reference atlas, version 1 (2008) (PDF file). from Allen Institute for Brain Science http://help.brain-map.org/display/mousebrain/Documentation

- Anderson RA, & Mitchell R (1986). Effects of gamma-aminobutyric acid receptor agonists on the secretion of growth hormone, luteinizing hormone, adrenocorticotrophic hormone and thyroid-stimulating hormone from the rat pituitary gland in vitro. J Endocrinol, 108(1), 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Jonathan N, & Hnasko R (2001). Dopamine as a prolactin (PRL) inhibitor. Endocr Rev, 22(6), 724–763. 10.1210/edrv.22.6.0451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Jonathan N, Oliver C, Weiner HJ, Mical RS, & Porter JC (1977). Dopamine in hypophysial portal plasma of the rat during the estrous cycle and throughout pregnancy. Endocrinology, 100(2), 452–458. 10.1210/endo-100-2-452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Björklund A, & Dunnett SB (2007). Dopamine neuron systems in the brain: an update. Trends Neurosci, 30(5), 194–202. 10.1016/j.tins.2007.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Björklund A, & Lindvall O (1984). Dopamine-containing systems in the CNS. In Björklund A & Hökfelt T (Eds.), Handbook of Chemical Neuroanatomy, Volume 2: Classical Transmitters in the CNS, Part I (pp. 55–122). Amsterdam: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Björklund A, & Nobin A (1973). Fluorescence histochemical and microspectrofluorometric mapping of dopamine and noradrenaline cell groups in the rat diencephalon. Brain Res, 51, 193–205. 10.1016/0006-8993(73)90372-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borisovska M, Bensen AL, Chong G, & Westbrook GL (2013). Distinct modes of dopamine and GABA release in a dual transmitter neuron. J Neurosci, 33(5), 1790–1796. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4342-12.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bota M, & Swanson LW (2007). The neuron classification problem. Brain Res Rev, 56(1), 79–88. 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourdy R, Sánchez-Catalán M-J, Kaufling J, Balcita-Pedicino JJ, Freund-Mercier M-J, Veinante P, … Barrot M (2014). Control of the Nigrostriatal Dopamine Neuron Activity and Motor Function by the Tail of the Ventral Tegmental Area. Neuropsychopharmacology, 39(12), 2788. 10.1038/npp.2014.129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broberger C, de Lecea L, Sutcliffe JG, & Hökfelt T (1998). Hypocretin/orexin- and melanin-concentrating hormone-expressing cells form distinct populations in the rodent lateral hypothalamus: relationship to the neuropeptide Y and agouti gene-related protein systems. J Comp Neurol, 402(4), 460–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broberger C, Johansen J, Johansson C, Schalling M, & Hökfelt T (1998). The neuropeptide Y/agouti gene-related protein (AGRP) brain circuitry in normal, anorectic, and monosodium glutamate-treated mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 95(25), 15043–15048. 10.1073/pnas.95.25.15043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch S, Selcho M, Ito K, & Tanimoto H (2009). A map of octopaminergic neurons in the Drosophila brain. J Comp Neurol, 513(6), 643–667. 10.1002/cne.21966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrera I, Anadón R, & Rodríguez-Moldes I (2012). Development of tyrosine hydroxylase-immunoreactive cell populations and fiber pathways in the brain of the dogfish Scyliorhinus canicula: new perspectives on the evolution of the vertebrate catecholaminergic system. J Comp Neurol, 520(16), 3574–3603. 10.1002/cne.23114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chee MJ, Arrigoni E, & Maratos-Flier E (2015). Melanin-concentrating hormone neurons release glutamate for feedforward inhibition of the lateral septum. J Neurosci, 35(8), 3644–3651. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4187-14.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chee MJ, Negishi K, Schumacker KS, Butler RB, & Khan AM (2017). Immunohistochemical study and atlas mapping of neuronal populations that co-express tyrosine hydroxylase and the vesicular GABA transporter in the hypothalamus. Program 604.04. Poster presented at the Society for Neuroscience, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Chee MJ, Negishi K, Schumacker KS, Butler RB, & Khan AM (2018). Identification and atlas mapping of mouse hypothalamic neurons that co-express tyrosine hydroxylase and the vesicular GABA transporter in in situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry studies. Program No. 680.27. Poster presented at the Society for Neuroscience, San Diego, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Chee MJ, Pissios P, & Maratos-Flier E (2013). Neurochemical characterization of neurons expressing melanin-concentrating hormone receptor 1 in the mouse hypothalamus. J Comp Neurol, 521(10), 2208–2234. 10.1002/cne.23273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou XL, Wang X, Zhang ZG, Shen L, Zingg B, Huang J, … Tao HW (2018). Inhibitory gain modulation of defense behaviors by zona incerta. Nat Commun, 9(1), 1151. 10.1038/s41467-018-03581-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung EKY, Chen LW, Chan YS, & Yung KKL (2008). Downregulation of glial glutamate transporters after dopamine denervation in the striatum of 6-hydroxydopamine-lesioned rats. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 511(4), 421–437. 10.1002/cne.21852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark AM, Leroy F, Martyniuk KM, Feng W, McManus E, Bailey MR, … Kellendonk C (2017). Dopamine D2 receptors in the paraventricular thalamus attenuate cocaine locomotor sensitization. eNeuro, 4(5). 10.1523/ENEURO.0227-17.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosetto N, Bienko M, & van Oudenaarden A (2015). Spatially resolved transcriptomics and beyond. Nat Rev Genet, 16(1), 57–66. 10.1038/nrg3832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlström A, & Fuxe K (1964). Evidence for the existence of monoamine-containing neurons in the central nervous system. I. Demonstration of monoamines in the cell bodies of brain stem neurons. Acta Physiol Scand Suppl, Suppl 232, 1–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong HW (2008). The Allen reference atlas: A digital color brain atlas of the C57BL/6J male mouse. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Elias CF, Saper CB, Maratos-Flier E, Tritos NA, Lee C, Kelly J, … Elmquist JK (1998). Chemically defined projections linking the mediobasal hypothalamus and the lateral hypothalamic area. J Comp Neurol, 402(4), 442–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everitt BJ, Meister B, Hökfelt T, Melander T, Terenius L, Rokaeus A, … et al. (1986). The hypothalamic arcuate nucleus-median eminence complex: immunohistochemistry of transmitters, peptides and DARPP-32 with special reference to coexistence in dopamine neurons. Brain Res, 396(2), 97–155. 10.1016/s0006-8993(86)80192-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florenzano F, Viscomi MT, Mercaldo V, Longone P, Bernardi G, Bagni C, … Carrive P (2006). P2X2R purinergic receptor subunit mRNA and protein are expressed by all hypothalamic hypocretin/orexin neurons. J Comp Neurol, 498(1), 58–67. 10.1002/cne.21013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin KB, & Paxinos G (2012). The mouse brain in stereotaxic coordinates (4th ed.). New York, NY: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fremeau RT Jr., Troyer MD, Pahner I, Nygaard GO, Tran CH, Reimer RJ, … Edwards RH (2001). The expression of vesicular glutamate transporters defines two classes of excitatory synapse. Neuron, 31(2), 247–260. 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00344-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandison L, & Guidotti A (1979). gamma-Aminobutyric acid receptor function in rat anterior pituitary: evidence for control of prolactin release. Endocrinology, 105(3), 754–759. 10.1210/endo-105-3-754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn TM, Breininger JF, Baskin DG, & Schwartz MW (1998). Coexpression of Agrp and NPY in fasting-activated hypothalamic neurons. Nat Neurosci, 1(4), 271–272. 10.1038/1082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliday GM, & McLachlan EM (1991). A comparative analysis of neurons containing catecholamine-synthesizing enzymes and neuropeptide Y in the ventrolateral medulla of rats, guinea-pigs and cats. Neuroscience, 43(2–3), 531–550. 10.1016/0306-4522(91)90313-d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hökfelt T, Holets VR, Staines W, Meister B, Melander T, Schalling M, … et al. (1986). Coexistence of neuronal messengers--an overview. Prog Brain Res, 68, 33–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hökfelt T, Johansson O, Fuxe K, Goldstein M, & Park D (1976). Immunohistochemical studies on the localization and distribution of monoamine neuron systems in the rat brain. I. Tyrosine hydroxylase in the mes- and diencephalon. Med Biol, 54(6), 427–453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hökfelt T, Märtensson R, Björklund A, Kleinau S, & Goldstein M (1984). Distributional maps of tyrosine hydroxylase-immunoreactive neurons in the rat brain. In Björklund A & Hökfelt T (Eds.), Handbook of Chemical Neuroanatomy, vol. 2. Classical Transmitters in the CNS, Part I. (pp. 277–379). Amsterdam: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Ju G, Liu S, & Tao J (1986). Projections from the hypothalamus and its adjacent areas to the posterior pituitary in the rat. Neuroscience, 19(3), 803–828. 10.1016/0306-4522(86)90300-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]