Abstract

Context

Active surveillance (AS) of thyroid cancer with serial ultrasounds is a newer management option in the United States.

Objective

This work aimed to understand factors associated with the adoption of AS.

Methods

We surveyed endocrinologists and surgeons in the American Medical Association Masterfile. To estimate adoption, respondents recommended treatment for 2 hypothetical cases appropriate for AS. Established models of guideline implementation guided questionnaire development. Outcome measures included adoption of AS (nonadopters vs adopters, who respectively did not recommend or recommended AS at least once; and partial vs full adopters, who respectively recommended AS for one or both cases).

Results

The 464 respondents (33.3% response) demographically represented specialties that treat thyroid cancer. Nonadopters (45.7%) were significantly (P < .001) less likely than adopters to practice in academic settings, see more than 25 thyroid cancer patients/year, be aware of AS, use applicable guidelines (P = .04), know how to determine whether a patient is appropriate for AS, have resources to perform AS, or be motivated to use AS. Nonadopters were also significantly more likely to be anxious or have reservations about AS, be concerned about poor outcomes, or believe AS places a psychological burden on patients. Among adopters, partial and full adopters were similar except partial adopters were less likely to discuss AS with patients (P = .03) and more likely to be anxious (P = .04), have reservations (P = .03), and have concerns about the psychological burden (P = .009) of AS. Few respondents (3.2%) believed patients were aware of AS.

Conclusion

Widespread adoption of AS will require increased patient and physician awareness, interest, and evaluation of outcomes.

Keywords: thyroid cancer, active surveillance, surveillance, microcarcinoma, survey, thyroid cancer

Clinical practice guidelines are systematically developed to support clinical decision making and decrease the gap between innovative research and clinical practice. Guidelines can reduce unwarranted variability in practice patterns, improve patient outcomes, and decrease costs of care. However, clinical guidelines are often adopted into practice slowly or not at all (1). In the United States, adoption of guidelines supporting active surveillance for small, low-risk thyroid cancer appears to be no different and remains in the early stages. The American Thyroid Association (ATA) guidelines endorsed active surveillance as appropriate management for “very low-risk thyroid cancer (eg, papillary microcarcinomas without clinically evident metastases or local invasion, and no convincing cytologic or molecular evidence of aggressive disease)” in late 2015, based largely on observational data and successful long-term outcomes from Japan (2-4). The National Comprehensive Cancer Network and other guidelines also now support this practice, which involves observation of small cancers with serial ultrasound imaging and laboratory monitoring rather than traditional surgical resection (5, 6). Whereas active surveillance has become an established practice in Japan and other countries, there is no evidence suggesting similar adoption of this approach in the United States (7-16).

In an effort to identify and address barriers to adopting active surveillance, we previously surveyed high-volume providers who were members of 3 large national organizations—the ATA, American Association of Endocrine Surgeons, and American Head and Neck Surgeons (17, 18). These providers most likely represented innovators and early adopters of this nonoperative management strategy (19). While respondents generally supported active surveillance, only 23% recommended this management for a hypothetical patient with a 0.8-cm low-risk papillary thyroid cancer (19, 20). Main barriers to adopting surveillance appeared to be concerns about research supporting the approach as well as guideline and protocol development (19). While these data on high-volume providers are necessary to direct implementation efforts, little is known about adoption of active surveillance by the majority of providers across the United States, many of whom are lower in volume and often are not members of national subspecialty organizations.

In the present study, we aimed to understand adoption of active surveillance in the United States by surveying a large, diverse, nationally representative sample of physicians who treat patients with thyroid cancer. Using adoption of innovation as a framework for analysis, we focused on characterizing nonadopters or those who would not currently recommend active surveillance in clinical practice by comparing them to adopters, those physicians who would recommend surveillance to an appropriate patient. We also examined differences among respondents who recommended active surveillance by characterizing those who likely represent early or full adopters, meaning those physicians who adopt a practice after a smaller population of innovators have pioneered the approach, but before the majority do so. This analytic framework allowed identification of specific areas on which to focus future implementation efforts.

Materials and Methods

Population

This cross-sectional study surveyed 1500 physicians registered with the American Medical Association (AMA). The sample was stratified by specialty to include all physicians who might recommend active surveillance for thyroid cancer: endocrinologists (n = 500), general surgeons (n = 500), and otolaryngologists (n = 500). Prior to mailing the survey, offices of physicians in the sample were contacted by telephone to verify their address and confirm they treat patients with thyroid disease. Physicians were excluded if they were retired (n = 5), entered practice after release of the 2015 guidelines (n = 1), or had not treated a patient with thyroid cancer since 2015 (n = 22).

Study design

Physicians were mailed a cover letter, pretested questionnaire, and $5 cash on August 10, 2018. A reminder postcard was sent to all physicians 5 days following the initial mailing. Those who did not respond within 3 weeks were mailed a second questionnaire. This study was determined to be exempt by the University of Wisconsin (UW) Institutional Review Board (2018-0263).

Instrument development

The UW Survey Center assisted with development of the survey instrument, which included standard demographics and practice characteristics, such as age, years in practice, and patient volume. A copy of the survey is available online at http://digital.library.wisc.edu/1793/80823. Questions about adoption and use of active surveillance were based on 2 well-described models of guideline adherence and implementation, results from a previous survey of high-volume thyroid specialists, qualitative interviews with the target population, and published surveys about active surveillance for prostate cancer (17, 19-25). Respondents were asked to what extent they agreed with 9 statements about active surveillance, such as “I have reservations about active surveillance” and “I have the appropriate resources to perform active surveillance” with response options on a 5-point, unipolar Likert scale ranging from “not at all” to “a great deal.” Respondents’ awareness of active surveillance as a management option and discussion of the option were also assessed with yes/no questions. The likelihood of 3 different interventions making respondents more likely to offer active surveillance in their practice was assessed with yes/no/maybe response options.

Two clinical cases were used to assess adoption of active surveillance: (1) a 45-year-old woman with a solitary, node-negative 0.8-cm papillary thyroid cancer with no adverse clinical features or family/medical history and (2) the same case adding that “the patient prefers active surveillance.” Response options included active surveillance, thyroid lobectomy, total thyroidectomy, and total thyroidectomy with central neck dissection.

An established group of clinician stakeholders from academic (n = 4) and community (n = 6) practices in rural and urban Wisconsin and Illinois reviewed the overall survey content and individual questions. Stakeholders’ specialties represented the target audience and were from endocrinology (n = 5), endocrine surgery (n = 3), radiology (n = 1), and otolaryngology (n = 1). The clinician stakeholders unanimously agreed the 2 cases used to assess adoption were appropriate for active surveillance. All questions were cognitively tested by interviewing members of the target population while they took the survey and probing to ensure the questions were clear, consistent, and interpreted as intended. Prior to mailing, the instrument was piloted by a multidisciplinary group of 6 clinicians and researchers at the UW including members of all 3 specialties surveyed and revised accordingly.

Analysis

To examine response bias, we compared the demographics available from the AMA for those who responded to the initial mailing (early responders) to those who responded to later mailings (late responders). We also compared all survey responders to nonresponders.

To examine the study cohort, respondent demographics and questions about barriers to guideline implementation were analyzed with standard descriptive statistics. For the primary analysis, we compared nonadopters, defined as those who did not recommend active surveillance for either clinical case scenario, to adopters, referring to all other respondents who recommended active surveillance for at least 1 of the 2 clinical cases first using Fisher exact and t tests as appropriate for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. We then estimated associations using weighted logistic regression using inverse probability weighting adjusted for age and sex as these 2 variables were available from the AMA on nonresponders. Results of the initial unweighted bivariate comparisons are reported except where noted. Using the same statistical methods, we also examined the adopters based on whether they recommended surveillance for both cases or only the case in which the patient in the scenario preferred active surveillance. We respectively refer to these groups as full adopters (recommended active surveillance for both cases) and partial adopters (recommended surveillance only when the patient prefers active surveillance). Analyses were performed using R software, version 3.6.1. P less than .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

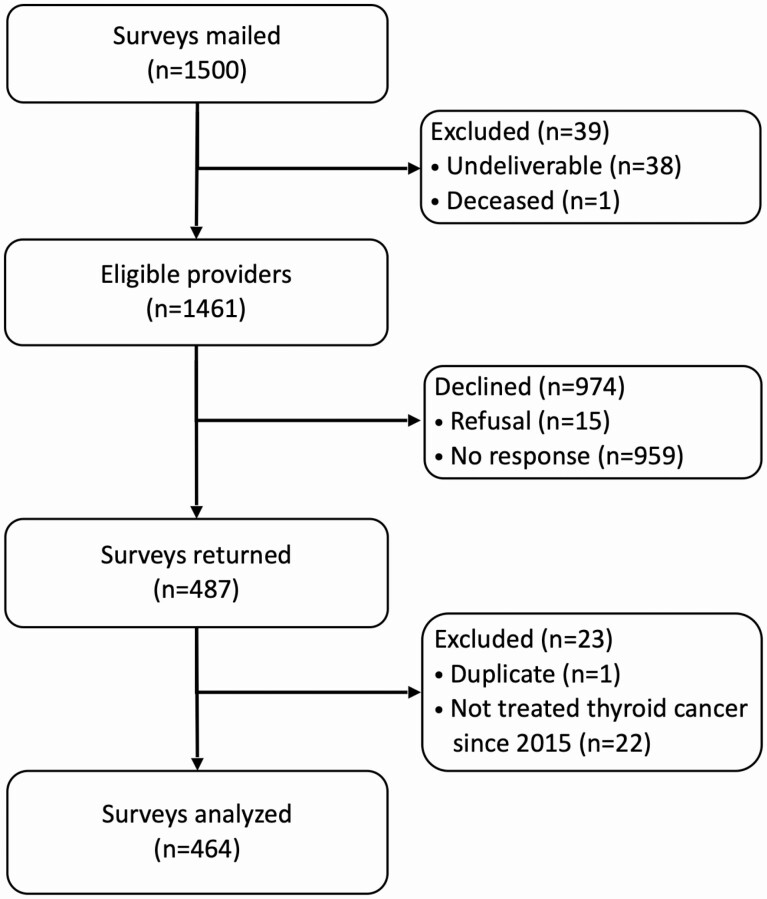

Questionnaires were returned by 487 (33.3%) physicians, of whom 464 met inclusion criteria and were analyzed (Fig. 1). The cohort included 144 endocrinologists, 122 general surgeons, and 198 otolaryngologists who were age 53.6 ± 9 years and practiced 20.7 ± 9 years; 78.2% (n = 347) were male, and 76.1% (n = 334) White. Survey respondents were demographically similar to published American Association of Medical Colleges data available about active physicians in each specialty (26). Analyses for response bias comparing respondents based on the timing of survey response (early vs late) showed no significant differences in age, sex, specialty, years in practice, or type of practice. When respondents were compared to nonrespondents using demographic data obtained from the AMA, respondents were similar in age, but were more likely than nonrespondents to be male (79.7% vs 73.2%, P = .008).

Figure 1.

Summary of survey response. Overall response rate was 33.3%, calculated as (surveys returned ÷ eligible providers).

Characteristics of nonadopters

Overall, 45.7% of physicians (n = 212) were categorized as nonadopters and did not recommend active surveillance for either case scenario (Table 1). When compared to adopters who recommended active surveillance for at least one case, nonadopters were similar in age, sex, race/ethnicity, years in practice, and access to a tumor board in the unweighted bivariate analysis. However, nonadopters of active surveillance were significantly less likely to practice in an academic tertiary setting, see more than 25 thyroid cancer patients annually, or personally perform cervical ultrasound. Nonadopters also tended to be more likely to agree “quite a bit” or “a great deal” that uncertainty made them uneasy (P = .06).

Table 1.

Respondent demographics and clinical characteristics by adoption of active surveillance (unweighted percentage)

| Nonadopters n (%) | Adopters (n = 252, 54.3%) | P a | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Partial adopters n (%) | Full adoptersb n (%) | |||

| N = 464 | 212 (45.7) | 196 (42.2) | 53 (11.4) | – |

| Age, y (mean ± SD) | 53.9 ± 8.9 | 53.0 ± 9.2 | 55.1 ± 9.1 | .55 |

| Male | 160 (81.6) | 146 (76.0) | 40 (76.9) | .21d |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Caucasian | 152 (77.2) | 146 (78.5) | 34 (65.4) | .91 |

| Black | 3 (1.5) | 3 (1.6) | 1 (1.9) | |

| Asian | 26 (13.2) | 26 (14.0) | 11 (21.2) | |

| Other | 16 (8.2) | 11 (5.9) | 6 (11.5) | |

| Years in practice | 20.7 ± 8.7 | 20.6 ± 9.4 | 21.7 ± 9.1 | .88 |

| Practice setting | ||||

| Academic tertiary | 17 (8.6) | 40 (20.6) | 8 (15.1) | < .001 |

| Academic affiliated | 17 (8.6) | 19 (9.8) | 6 (11.3) | |

| Private practice | 57 (28.8) | 94 (48.5) | 29 (54.7) | |

| Community hospital | 105 (53) | 34 (17.5) | 7 (13.2) | |

| Other | 2 (1) | 7 (3.6) | 3 (5.7) | |

| Treats > 25 thyroid cancer patients/y | 49 (24.4) | 83 (42.8) | 22 (41.5) | < .001 |

| Has access to tumor board | 141 (70.9) | 139 (71.6) | 38 (71.7) | .87 |

| Personally performs US | 54 (27.1) | 75 (38.7) | 22 (41.5) | .007 |

| Rates US quality as excellent or very good | 154 (76.6) | 154 (79.0) | 42 (78.8) | .47 |

| Uncertainty in patient care makes them uneasyc | 64 (33.0) | 51 (26.6) | 8 (15.7) | .06d |

| Rarely takes risks in their own lifec | 57 (30.0) | 51 (26.7) | 13 (25.0) | .60 |

Abbreviation: US, ultrasound.

a P values represent unweighted chi-square and t test comparison between nonadopters and adopters.

b Three respondents were not categorized as partial or full adopter because they did not answer the hypothetical case scenario about patient preference.

c Proportion of respondents who agree “quite a bit” or “a great deal.”

d Respondent sex and uncertainty were significantly associated with adoption of active surveillance on multivariable, weighted regression analysis, P equal to .006 and P equal to .002, respectively.

Barriers to active surveillance for nonadopters

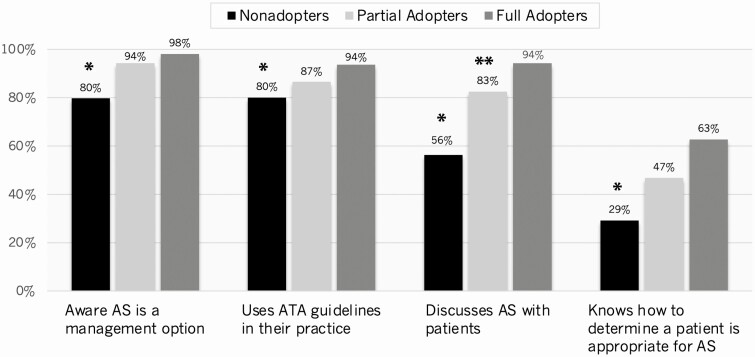

Fig. 2 presents respondents’ awareness, knowledge, and use of active surveillance in unweighted comparisons. Nonadopters were significantly less likely than adopters to be aware active surveillance is a management option for select patients with low-risk thyroid cancer, report using the 2015 ATA guidelines in their practice, or report ever discussing surveillance with patients. Nonadopters were also significantly less likely to agree “quite a bit” or “a great deal” that they know how to determine whether a patient is appropriate for surveillance.

Figure 2.

Histograms show respondents’ awareness, knowledge, and discussion of active surveillance (AS) in their clinical practice (unweighted %). For symbols, “*” indicates P less than .05 for nonadopters compared to adopters (both partial and full adopters) and “**” indicates P less than .05 for partial vs full adopters.

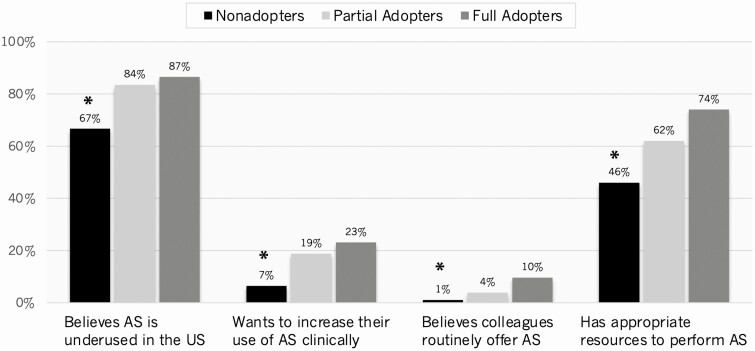

When questioned about use of active surveillance, 76.8% of all respondents (n = 325) believed active surveillance is underused in the United States, as opposed to appropriately or overused. Nonadopters were significantly less likely than adopters to believe surveillance is underused (Fig. 3). Nonadopters were also significantly less likely to agree “quite a bit” or “a great deal” that they want to increase their use of active surveillance in their own clinical practice, believe their colleagues routinely offer surveillance, or have the appropriate resources to perform surveillance.

Figure 3.

The histograms illustrate respondents’ beliefs about the use of active surveillance (AS) in the United States and factors impacting their motivation to increase use of AS (unweighted %). For symbols, “*” indicates P less than .05 for nonadopters vs adopters (both partial and full adopters).

Although the majority of all respondents believed active surveillance is underused, only 14.1% (n = 61) agreed “quite a bit” or a “great deal” that they want to increase their use of active surveillance clinically. Most respondents agreed they would be more likely to offer active surveillance if patients signed a standardized consent form to enroll in surveillance (53.6%; n = 237), had informational materials about surveillance for their patients (52.9%; n = 234), or had more information for themselves (46.5%; n = 205). There were no significant differences in unweighted analyses between respondents with respect to interventions that would increase their use of active surveillance, though nonadopters tended to be less likely to want informational materials for their patients (46.9% vs 57.1%, P = .078).

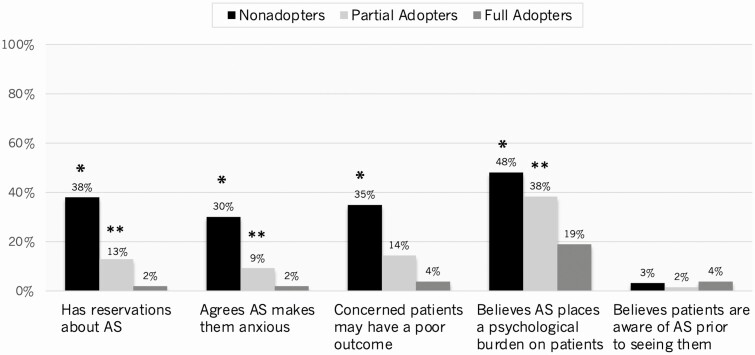

Fig. 4 presents respondents’ attitudes and beliefs about active surveillance. Nonadopters were significantly more likely than adopters to agree “quite a bit” or “a great deal” that they have reservations about active surveillance and surveillance makes them anxious. Nonadopters were also significantly more likely to agree that they are concerned patients undergoing active surveillance may have a poor outcome or believe surveillance places a psychological burden on patients. Very few respondents agreed “quite a bit” or “a great deal” that patients are aware of active surveillance before seeing them (nonadopters 3.2% vs all adopters 2.0%, P = .70).

Figure 4.

Histograms depicting respondents’ attitudes and beliefs about active surveillance (AS) (unweighted %). For symbols, “*” indicates P less than .05 for nonadopters vs adopters (both partial and full); “**” indicates P less than .05 for partial vs full adopters.

Adjusted analyses performed to model nonresponse using weighted regression confirmed all the significant differences found between nonadopters and adopters on unweighted comparisons. However, in weighted models, uncertainty in patient care (P = .002) and age (P = .006) were also significantly associated with nonadoption. Meanwhile, having informational materials for patients about active surveillance (P < .001) or having patients sign a standardized consent (P = .028) was associated with increased likelihood of offering active surveillance.

Adopters only: partial adopters vs full adopters

Unweighted analyses of only the adopters (n = 252) showed that there were no differences with respect to age, sex, race/ethnicity, years in practice, volume of thyroid cancer patients seen annually, practice setting, tumor board access, and self-reported uncertainty with patient care when comparing partial adopters (n = 196; 42.2%), who recommended surveillance only when the case stated the “patient prefers active surveillance,” to full adopters (n = 53; 11.4%), who recommended active surveillance for both cases. Fig. 2 shows there also were no statistically significant differences between partial and full adopters with respect to awareness that active surveillance is a management option for select patients with low-risk thyroid cancer, use of the 2015 ATA guidelines in their practice, or knowing how to determine whether a patient is appropriate for active surveillance. However, partial adopters were less likely than full adopters to report ever discussing active surveillance clinically (P < .05).

Fig. 4 depicts that partial adopters were also more likely to agree “quite a bit” or “a great deal” that they have reservations about active surveillance and that active surveillance makes them anxious (P < .05). Partial adopters were additionally more likely to agree “quite a bit” or “a great deal” that active surveillance places a psychological burden on patients (P < .01) and tended to be more concerned that patients undergoing active surveillance may have a poor outcome (P = .06). No differences existed on unweighted comparisons between the 2 groups of adopters with respect to any of the other barriers assessed or the use of potential interventions.

These differences observed between full and partial adopters on unweighted analyses were again confirmed to be significant when modeling with nonresponse weighted regression adjusted for age and sex. However, several additional variables were significant in weighted models. Increased uncertainty in patient care (P = .002), not using the ATA guidelines (P = .049), reporting low ultrasound quality for clinical decision making (P = .028), not having appropriate resources to perform active surveillance (P = .016), and having concerns about poor patient outcomes (P < .001) and the psychological burden on patients (P = .002) were also associated with partial adoption, whereas wanting to increase the use of active surveillance clinically (P = .048) was associated with full adoption. Having information materials about active surveillance was also significant on weighted regression (P = .006).

Discussion

In this large, nationally representative survey of thyroid cancer providers, fewer than 1 in 7 respondents recommended active surveillance for a hypothetical patient with a low-risk papillary cancer measuring less than a centimeter. The proportion of providers recommending active surveillance increased to nearly 4 in 7 if the hypothetical patient with a solitary microcarcinoma preferred active surveillance. These data suggest that adoption of active surveillance in the United States is still in the early stages and approaches that increase patient awareness of this option, including standardized educational materials, may be effective. Major barriers to adopting active surveillance among physicians in the United States include lack of knowledge and awareness of guidelines supporting active surveillance, not knowing when a patient is appropriate for surveillance, not having appropriate resources, and not wanting to increase their use of surveillance. Additional barriers even for those physicians most likely to use this nonoperative approach include concerns about adverse patient outcomes, the psychological burden of active surveillance on patients, and physician’s own anxiety and reservations about active surveillance. Similar patient-related barriers to active surveillance were recently identified in a survey of physicians from Georgia and Los Angeles, California (27). These concerns likely arise from the difficulty in identifying patients who are at risk for progression and development of metastasis during surveillance because not all papillary microcarcinomas are indolent.

Implementation of guidelines such as the 2015 ATA guideline for active surveillance are known to be challenging because barriers like the ones identified in this study and other studies often exist (27). Not surprisingly, similar barriers have been identified for active surveillance of patients with low-risk prostate cancer (28-30). Identifying these barriers and constructing targeted implementation strategies is key, as is learning from our urologic and radiation oncology colleagues who have faced similar challenges. Classic models of guideline implementation describe 4 key domains into which barriers can be categorized, including physicians’ knowledge, physician attitudes, guideline-related factors, and external factors (1, 21). When physicians consider adopting a new practice or technology, they often confront these barriers in their implementation efforts. The results of this study suggest barriers to adopting guidelines related to active surveillance fall into all 4 domains. Therefore, multiple strategies will be necessary to facilitate adoption of active surveillance in the United States and should be aimed at addressing known barriers.

In terms of barriers related to physician knowledge and attitudes, although the majority of the respondents in this study were aware active surveillance is appropriate, 20% of nonadopters were not aware that surveillance is supported by guidelines. Additionally, fewer than 3 out of 4 respondents reported discussing active surveillance with appropriate patients and even fewer recommended this option to an appropriate hypothetical patient. A similar survey study recently published by Hughes et al of 448 physicians found that while 3 out of 4 physicians agree active surveillance is an appropriate management option, only 44% currently recommend it (27). The findings of our study and that by Hughes et al are important because they both have a high proportion of respondents from nonacademic and lower-volume practices, which was associated with a lower likelihood of believing active surveillance is an appropriate management in the study by Hughes and colleagues. In the present study, one reason for the lack of support for active surveillance was that less than half of respondents agreed they knew how to determine whether a patient is appropriate for surveillance. This lack of knowledge may be in part due to limitations of the guidelines for not specifying what constitutes appropriate surveillance in terms of frequency and type of imaging or how thyroglobulin should be measured and interpreted. The lack of an optimal surveillance strategy and unknown length of follow-up were cited in the Hughes et al study as barriers to implementation (27). We also previously showed that many physicians find the guidelines about active surveillance too vague (20). In addition to clarifying written guidelines, useful approaches to improve physicians’ knowledge of a guideline include active learning from highly experienced experts at conferences, workshops, and other continuous medical education events, but this approach still relies on providers attending these events (31-33). Therefore, online dissemination via webinars, web-based learning or clinical decision-making modules, videos, emails, and other targeted promotion from national, state, and specialty societies may be necessary to support adoption (33, 34). Physician attitudes, on the other hand, are often better addressed with individualized audit and feedback systems or establishing evidence that changes their beliefs (1, 33, 35, 36). With active surveillance, this tactic would entail establishing data that show patients do not have adverse medical or psychological outcomes, research that is fortunately well under way (13, 16, 37-42).

Additional implementation strategies exist to address physicians who face external barriers to implementing active surveillance like lack of appropriate resources or guideline-related factors. Close to half of respondents in this study did not agree that they have the appropriate resources to perform active surveillance in their practice. Given that this study included a large national cohort, this proportion is not that surprising. It has been suggested that active surveillance may be best performed at centers of excellence (43). Such centralization of surveillance services could aid in more widespread implementation, though logistical transportation and follow-up issues may emerge as patient-related barriers.

Other methods to move past organizational constraints include multiprofessional collaboration with other health care professionals who perform active surveillance and establishing clear roles in the surveillance process (1). Multi-institutional or organizational-based collaboratives could support such efforts, as could partnership among endocrinologists, radiologists, surgeons, advanced practice providers, and others involved in surveilling patients. Dedicated education and training of providers as to when and how to perform active surveillance as well as standardization of processes, procedures, and protocols can also help overcome organizational constraints. Although this survey did not focus on guideline-related factors, our prior work suggests that guidelines could be clearer and include suggested protocols, which is supported by the findings of others (17, 27).

The results of this survey should be considered in the context of its limitations. First, survey studies are at risk for social desirability bias whereby respondents select what they believe is the “correct” answer. The finding that less than 15% of respondents recommended active surveillance for all cases where it was appropriate indicates that this form of bias was minimal. Second, the response rate was low. While the demographic similarity of responders and nonresponders as well as early and late responders suggests nonresponse bias was minimal, bias may still exist and limit the generalizability of results. The only difference between responders and nonresponders was that responders were more likely to be male, which differs from common patterns in survey response bias for which women are more likely to respond. This finding was likely due to otolaryngologists, who are predominantly male, representing more than a third of the analyzed cohort. While only 1 in 3 physicians responded to the survey, responders were similar to American Association of Medical Colleges–published averages for each specialty, which suggests the cohort was representative of physicians who treat thyroid cancer in the United States. In addition, weighted analyses that modeled nonresponse confirmed the bivariate results. The national sampling strategy and sample size are strengths of this study, as are the proportion of responders in private and community practices and the proportion who were low-volume surgeons who perform the majority of thyroid surgery in the United States (44).

Adoption of a new, innovative approach such as active surveillance for thyroid cancer involves multiple steps for physicians. These steps include awareness and knowledge of the approach, interest in actually performing surveillance, evaluation of the practice including data supporting its use and outcomes, a period of trialing, and finally full integration into routine practice. The results of this survey suggest that barriers exist at all 5 of these stages of adoption and particularly at stages involving awareness and knowledge, interest, and evaluation. In addition to physicians not being aware of guidelines supporting active surveillance, many are not interested in or motivated to adopt active surveillance into their clinical practice. Beliefs and concerns about potential adverse patient outcomes are also prevalent, because not all microcarcinomas are indolent. Until implementation strategies address each of these barriers and resources are allocated for this purpose, active surveillance is unlikely to be widely adopted by physicians across the United States. Because physicians in this study were responsive to patient preference, implementation strategies aimed at increasing patient awareness will likely also be important and complement physician-focused efforts.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the efforts of Margarete Wichman, PhD, Griselle Sanchez-Diettert, BA, and Kelly M. Elver, PhD, from the UW Survey Center for their assistance with survey preparation and critical review.

Financial Support: This work was supported by the UW Carbone Cancer Center (support grant No. P30 CA014520, principal investigator S.C.P.); the National Cancer Institute (NCI) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (award No. K08CA230204 to S.C.P.); and the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (support grant No. P30 CA008748 from the NIH/NCI to B.R.R.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. In addition, the NIH did not play a role in the design or conduct of the study; data collection, management, analysis or interpretation; manuscript preparation, review, or approval; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AMA

American Medical Association

- AS

active surveillance

- ATA

American Thyroid Association

- UW

University of Wisconsin

Additional Information

Disclosures: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Data Availability

The data sets generated during and/or analyzed during the present study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1. Fischer F, Lange K, Klose K, Greiner W, Kraemer A. Barriers and strategies in guideline implementation—a scoping review. Healthcare (Basel). 2016;4(3):1-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, et al. 2015 American Thyroid Association Management guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer: the American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Thyroid. 2016;26(1):1-133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ito Y, Miyauchi A, Kihara M, Higashiyama T, Kobayashi K, Miya A. Patient age is significantly related to the progression of papillary microcarcinoma of the thyroid under observation. Thyroid. 2014;24(1):27-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ito Y, Miyauchi A, Inoue H, et al. An observational trial for papillary thyroid microcarcinoma in Japanese patients. World J Surg. 2010;34(1):28-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Thyroid carcinoma (version 2.2020). Published 2020. Accessed August 26, 2020. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/thyroid.pdf

- 6. Filetti S, Durante C, Hartl D, et al. ; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Thyroid cancer: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(12):1856-1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Alhashemi A, Goldstein DP, Sawka AM. A systematic review of primary active surveillance management of low-risk papillary carcinoma. Curr Opin Oncol. 2016;28(1):11-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cho SJ, Suh CH, Baek JH, et al. Active surveillance for small papillary thyroid cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thyroid. 2019;29(10):1399-1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Choi JB, Lee WK, Lee SG, et al. Long-term oncologic outcomes of papillary thyroid microcarcinoma according to the presence of clinically apparent lymph node metastasis: a large retrospective analysis of 5,348 patients. Cancer Manag Res. 2018;10:2883-2891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ito Y, Miyauchi A, Kudo T, et al. Trends in the implementation of active surveillance for low-risk papillary thyroid microcarcinomas at Kuma hospital: gradual increase and heterogeneity in the acceptance of this new management option. Thyroid. 2018;28(4):488-495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ito Y, Miyauchi A, Oda H. Low-risk papillary microcarcinoma of the thyroid: a review of active surveillance trials. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2018;44(3):307-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kwon H, Oh HS, Kim M, et al. Active surveillance for patients with papillary thyroid microcarcinoma: a single center’s experience in Korea. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(6):1917-1925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Molinaro E, Campopiano MC, Pieruzzi L, et al. Active surveillance in papillary thyroid microcarcinomas is feasible and safe: experience at a single Italian center. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105(3):e172-e180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Oh HS, Ha J, Kim HI, et al. Active surveillance of low-risk papillary thyroid microcarcinoma: a multi-center cohort study in Korea. Thyroid. 2018;28(12):1587-1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sanabria A. Active surveillance in thyroid microcarcinoma in a Latin-American cohort. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;144(10):947-948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sawka AM, Ghai S, Yoannidis T, et al. A prospective mixed-methods study of decision-making on surgery or active surveillance for low-risk papillary thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2020;30(7):999-1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McDow AD, Brito JP, Saucke MC, et al. Factors influencing endocrinologists’ and surgeons’ recommendation for active surveillance. Thyroid. 2018;28:P-1-A-158. [Google Scholar]

- 18. McDow AD, Roman BR, Saucke MC, et al. Factors associated with physicians’ recommendations for managing low-risk papillary thyroid cancer. Am J Surg. Published online November 12, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2020.11.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jensen C, Roman BR, Brito JP, et al. Barriers to active surveillance: a survey of endocrinologists and surgeons. Thyroid. 2018;28:P-1-A-158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Roman BR, Brito JP, Saucke MC, et al. National survey of endocrinologists and surgeons regarding active surveillance for low risk papillary thyroid cancer. Endocr Pract. Published online November 16, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.eprac.2020.11.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, et al. Why don’t physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA. 1999;282(15):1458-1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cane J, O’Connor D, Michie S. Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implement Sci. 2012;7:37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fowler FJ Jr, McNaughton Collins M, Albertsen PC, Zietman A, Elliott DB, Barry MJ. Comparison of recommendations by urologists and radiation oncologists for treatment of clinically localized prostate cancer. JAMA. 2000;283(24): 3217-3222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. McNaughton Collins M, Barry MJ, Zietman A, et al. United States radiation oncologists’ and urologists’ opinions about screening and treatment of prostate cancer vary by region. Urology. 2002;60(4):628-633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kim SP, Gross CP, Nguyen PL, et al. Perceptions of active surveillance and treatment recommendations for low-risk prostate cancer: results from a national survey of radiation oncologists and urologists. Med Care. 2014;52(7):579-585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. American Association of Medical Colleges. 2018 Physician Specialty Data Report. 2018. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/interactive-data/2018-physician-specialty-report-data-highlights. Accessed March 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hughes DT, Reyes-Gastelum D, Ward KC, Hamilton AS, Haymart MR. Barriers to the use of active surveillance for thyroid cancer: results of a physician survey. Ann Surg. Published online October 16, 2020. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kim SP, Gross CP, Shah ND, et al. Perceptions of barriers towards active surveillance for low-risk prostate cancer: results from a national survey of radiation oncologists and urologists. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019;26(2):660-668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pickles T, Ruether JD, Weir L, Carlson L, Jakulj F; SCRN Communication Team . Psychosocial barriers to active surveillance for the management of early prostate cancer and a strategy for increased acceptance. BJU Int. 2007;100(3):544-551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Loeb S, Curnyn C, Fagerlin A, et al. Qualitative study on decision-making by prostate cancer physicians during active surveillance. BJU Int. 2017;120(1):32-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Barosi G. Strategies for dissemination and implementation of guidelines. Neurol Sci. 2006;27(Suppl 3):S231-S234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Harris MF, Parker SM, Litt J, et al. ; Preventive Evidence into Practice Partnership Group . Implementing guidelines to routinely prevent chronic vascular disease in primary care: the Preventive Evidence into Practice cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2015;5(12):e009397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tomasone JR, Kauffeldt KD, Chaudhary R, Brouwers MC. Effectiveness of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies on health care professionals’ behaviour and patient outcomes in the cancer care context: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2020;15(1):41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Likhterov I, Tuttle RM, Haser GC, et al. Improving the adoption of thyroid cancer clinical practice guidelines. Laryngoscope. 2016;126(11):2640-2645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hysong SJ, Best RG, Pugh JA. Audit and feedback and clinical practice guideline adherence: making feedback actionable. Implement Sci. 2006;1:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hysong SJ, Teal CR, Khan MJ, Haidet P. Improving quality of care through improved audit and feedback. Implement Sci. 2012;7:45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Davies L, Roman BR, Fukushima M, Ito Y, Miyauchi A. Patient experience of thyroid cancer active surveillance in Japan. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;145(4):363-370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jeon MJ, Lee YM, Sung TY, et al. Quality of life in patients with papillary thyroid microcarcinoma managed by active surveillance or lobectomy: a cross-sectional study. Thyroid. 2019;29(7):956-962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kong SH, Ryu J, Kim MJ, et al. Longitudinal assessment of quality of life according to treatment options in low-risk papillary thyroid microcarcinoma patients: active surveillance or immediate surgery (Interim Analysis of MAeSTro). Thyroid. 2019;29(8):1089-1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Haser GC, Tuttle RM, Su HK, et al. Active surveillance for papillary thyroid microcarcinoma: new challenges and opportunities for the health care system. Endocr Pract. 2016;22(5):602-611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sawka AM, Ghai S, Tomlinson G, et al. A protocol for a Canadian prospective observational study of decision-making on active surveillance or surgery for low-risk papillary thyroid cancer. BMJ Open. 2018;8(4):e020298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Moon JH, Kim JH, Lee EK, et al. Study protocol of multicenter prospective cohort study of active surveillance on papillary thyroid microcarcinoma (MAeSTro). Endocrinol Metab (Seoul). 2018;33(2):278-286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Brito JP, Ito Y, Miyauchi A, Tuttle RM. A clinical framework to facilitate risk stratification when considering an active surveillance alternative to immediate biopsy and surgery in papillary microcarcinoma. Thyroid. 2016;26(1):144-149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Adam MA, Thomas S, Youngwirth L, et al. Is there a minimum number of thyroidectomies a surgeon should perform to optimize patient outcomes? Ann Surg. 2017;265(2):402-407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data sets generated during and/or analyzed during the present study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.