Abstract

Since the first nationwide movement control order was implemented on 18 March 2020 in Malaysia to contain the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak, to what extent the uncertainty and continuous containment measures have imposed psychological burdens on the population is unknown. This study aimed to measure the level of mental health of the Malaysian public approximately 2 months after the pandemic’s onset. Between 12 May and 5 September 2020, an anonymous online survey was conducted. The target group included all members of the Malaysian population aged 18 years and above. The Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS-21) was used to assess mental health. There were increased depressive, anxiety and stress symptoms throughout the study period, with the depression rates showing the greatest increase. During the end of the data collection period (4 August–5 September 2020), there were high percentages of reported depressive (59.2%) and anxiety (55.1%) symptoms compared with stress (30.6%) symptoms. Perceived health status was the strongest significant predictor for depressive and anxiety symptoms. Individuals with a poorer health perception had higher odds of developing depression (odds ratio [OR] = 5.68; 95% confidence interval [CI] 3.81–8.47) and anxiety (OR = 3.50; 95%CI 2.37–5.17) compared with those with a higher health perception. By demographics, young people–particularly students, females and people with poor financial conditions–were more vulnerable to mental health symptoms. These findings provide an urgent call for increased attention to detect and provide intervention strategies to combat the increasing rate of mental health problems in the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

Introduction

In March 2020, the World Health Organization declared coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), a pandemic [1, 2]. COVID-19 has since caused major disruptions throughout the world, including in Malaysia. On 25 January 2020, Malaysian authorities reported the first SARS-CoV-2 infection; subsequently, on 17 March 2020, the first death was reported. Henceforth, the number of infections and deaths has increased exponentially in Malaysia. In the absence of pharmaceutical treatments and a vaccine for COVID-19, community containment measures are essential to limit the spread of SARS-CoV-2. The Malaysian government has implemented several movement control orders (MCOs) based on the current COVID-19 situation in the country. The first MCO included the closure of schools, higher education institutions and non-essential businesses (namely businesses that geared toward recreation or entertainment and those that provide services beyond the basic necessities), as well as a general prohibition of mass movements and gatherings across the country, including religious, sports, social and cultural activities. The first nationwide MCO was implemented on 18 March 2020. Since then, the country has gone through four MCO phases, all of which include the strict actions recommended by the WHO. A conditional movement control order (CMCO) was implemented from 13 May to 9 June 2020, and a recovery movement control order (RMCO) took effect from 10 June 2020 and lasted until 31 August 2020; it had more lenient restrictions. Subsequently, the RMCO was extended until 31 December 2020. To date, the Malaysian government has continuously stressed to the general public the use of face masks in public spaces, frequent hand washing and social distancing in the current ongoing pandemic. Large-scale gatherings are prohibited, but social and recreational activities and businesses are allowed to operate with social distancing measures and temperature checks in place.

Worldwide, measures to fight the COVID-19 outbreak have had tremendous social and economic impacts at both individual and country levels [3, 4]. Social distancing, self-isolation and travel restrictions have led to a reduced workforce across all economic sectors and employment loss. Closure of schools and working from home have impacted business operations, with a consequent decrease in the demand for commodities. In Malaysia, like other countries around the world, the COVID-19 pandemic has caused catastrophic economic and social disruptions [5–7]. The distancing measures, together with employment and financial insecurity, represent a massive mental health crisis affecting the wellbeing of populations throughout the world [8]. In Malaysia, the negative impact on mental health was evident during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic [5, 9, 10]. To date, nearly a year after the onset of the pandemic, to what extent the unpredictability and uncertainty of the COVID-19 pandemic and its prolonged physical distancing and containment measures, along with the resulting impact of the economic breakdown, has affected the mental health of the Malaysian public has never been investigated.

Therefore, the main aim of this study was to examine the level and temporal trend of mental health of the Malaysian public during the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, factors potentially contributing to poor mental health were investigated. These findings will provide insights for the formulation of mitigation measures to help the public cope with the negative mental health effects in the currently unpredictable situation of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Materials and methods

An anonymous Internet-based, cross-sectional survey was commenced on 12 May 2020 and ended on 5 September 2020. The inclusion criteria were that the respondents were from the general Malaysian public and ≥ 18 years old. The exclusion criteria were as follow: having chronic medical conditions, pregnancy or breastfeeding, and have never had SARS-CoV-2 infection. The researchers used social network platforms (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and WhatsApp) to disseminate and advertise the survey, entitled ‘COVID-19 Health and Wellbeing Survey’, to the public. Questions were presented in both English and Bahasa Malaysia in the survey link. Pilot testing was performed with 30 participants to ensure the clarity of the items and also gather suggestions for improvement. A minor revision was made based on the results of the pilot. Subsequently, the revised questionnaire was further pretested before field administration.

The first section of the survey collected demographic characteristics, participants’ health status and their COVID-19 experience. Health status included participants’ existing chronic diseases and self-perceived overall health status. The participants were asked to indicate whether they know of friends, neighbours or colleagues who had been diagnosed with COVID-19.

The second section assessed mental health using the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS-21) [11], which is a well-established instrument for measuring depression, anxiety and stress with good reliability and validity. Scores on three subscales–namely Depression (DASS-21-D), Anxiety (DASS-21-A) and Stress (DASS-21-S)–were generated. There are seven items in each subscale; the score of each subscale ranges from 0 to 21. The cut-offs for depression (moderate 7–10, severe 11–13 and extremely severe ≥ 14), anxiety (moderate 6–7, severe 8–9 and extremely severe ≥ 10) and stress (moderate 10–12, severe 13–16 and extremely severe ≥ 17) were calculated [12]. The English version of the DASS-21 has been validated for use in many Asian populations, including Malaysia [13]. The DASS-21 English version has been translated into Bahasa Malaysia and validated [14]; the Bahasa Malaysia DASS-21 has been used in many studies in Malaysia. A recent study evaluated the psychometric properties of the Bahasa Malaysia DASS-21 among non-Malays in Malaysia and revealed good reliability and validity, implying the scales can be used in a multiethnic population in Malaysia [15].

Data analysis

Cronbach’s alpha was calculated for the overall scale and the three subscales to assess reliability in terms of internal consistency. In this study, the DASS-21 had adequate to very good internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alphas of 0.956 for the overall scale, 0.927 for the DASS-21-D, 0.865 for the DASS-21-A and 0.882 for the DASS-21-S.

The temporal trend of the DASS-21-D, DASS-21-A and DASS-21-S scores over the 16-week data collection period was computed. The mean and standard deviation (SD) of the DASS-21 subscale scores were divided into four equal time periods of 4-week intervals: 12 May–7 June, 8 June–5 July, 6 July–3 August and 4 August–5 September. Univariable analyses followed by multivariable logistic regression analyses, using a simultaneous forced-entry method, was used to determine the factors influencing depression, anxiety and stress. Significant predictors at p < 0.05 in a bivariate analysis were exported to the multivariable logistic regression model. The DASS-21-D, DASS-21-A and DASS-21-S scores were grouped into two categories: 1 = moderate/severe/extremely severe and 0 = mild/normal. Odds ratios (ORs), 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) and p values were calculated for each independent variable. The model fit was assessed using the Hosmer−Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test [16]. Small p values (< 0.05) mean that the model is a poor fit. All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The level of significance was set at p < 0.05.

Ethical considerations

This research was approved by the University of Malaya Research Ethics Committee (UM.TNC2/UMREC– 884). Participants were informed that their participation was voluntary, and consent was implied by completing the questionnaire.

Results and discussion

Demographics

A total of 1,163 complete responses were received in the 16-week data collection period. Table 1 shows the demographics of the study participants compared with the general adult population in Malaysia [17, 18]. Compared with the general Malaysian population, there was a higher percentage of female respondents, Malay ethnicity, those from the central region and those in the bottom 40% (B40) income group (< MYR4850 [USD1200] per month). The age of the participants ranged from 18 to 84 years (M = 35.2, SD = 11.9). As shown in the first and second columns in Table 2, the majority of the study participants had a diploma or were university graduates. Based on the occupation categories, nearly half were in professional and managerial occupations (50.6%), while general workers and students comprised 7.2% and 29.2%, respectively, of the participants. For all participants, 44.9% reported an average monthly household income of < MYR4000, while 31.8% reported an average monthly household income of MYR4001–8000. The majority of participants were from urban (66.1%) and suburban (26.1%) areas. The majority perceived their overall health as very good/good (85.9%) and the majority (91.5%) did not have any chronic diseases. Only 23.4% reported knowing someone (family members, friends, neighbours or colleagues) who had been diagnosed with or died from COVID-19.

Table 1. Comparison of demographic characteristics of the study population and the general adult population in Malaysia, 2019.

| Characteristics | n | % Study population, n = 1163 | % Total population, n = 24510400 * |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age group (years) | |||

| 18–29 | 425 | 36.5 | 38.0 |

| 30–39 | 357 | 30.7 | 22.0 |

| 40–49 | 217 | 18.7 | 15.3 |

| ≥ 50 | 164 | 14.1 | 24.7 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 217 | 18.7 | 51.6 |

| Female | 946 | 81.3 | 41.4 |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Malay | 882 | 75.8 | 59.1 |

| Chinese | 100 | 8.6 | 37.4 |

| Indian | 108 | 9.3 | 29.4 |

| Others | 73 | 6.3 | 11.3 |

| Average monthly household income (MYR) (Income category group) † | |||

| Below MYR4850 (B40) | 651 | 56.0 | 16.0 |

| MYR4850-10959 (M40) | 365 | 31.4 | 37.2 |

| MYR 10600 and above (T20) | 147 | 12.6 | 46.8 |

| Region‡ | |||

| Northern | 157 | 13.5 | 20.9 |

| Central | 697 | 59.9 | 29.7 |

| East coast | 186 | 16.0 | 13.8 |

| Southern | 80 | 6.9 | 14.5 |

| Borneo | 43 | 3.7 | 21.1 |

*Total number of adults 15 to 79 years of age as of 31 December 2019. Source: The 2019 Population and Housing Census of Malaysia (Census 2010) Department of Statistics Malaysia.17

†Three category of income groups: Top 20% (T20), Middle 40% (M40), and Bottom 40% (B40) in Malaysia. Source: Department of Statistics Malaysia. Household Income and Basic Amenities Survey Report 2019.18

‡Northern region (Perlis, Kedah, Perak, Penang); Central (Wilayah Persekutuan Kuala Lumpur, Selangor, Negeri Sembilan, Putrajaya); East coast (Terengganu, Kelantan, Pahang); Southern (Melaka, Johor); Borneo (Sabah, Sarawak, Labuan)

Table 2. Univariable and multivariable analyses of factors associated with symptoms of depression, anxiety and stress (N = 1163).

| Depression | Anxiety | Stress | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Socio demographic characteristics | Overall N(%) | Moderate/ Severe/ Extremely severe (n = 344) | p-value | Adjusted OR (95%CI)a | Moderate/ Severe/ Extremely severe (n = 461) | p-value | Adjusted OR (95%CI)b | Moderate/ Severe/ Extremely severe (n = 202) | p-value | Adjusted OR (95%CI)c |

| Age group (years) | ||||||||||

| 18–25 | 322 (27.7) | 156 (48.4) | 2.03 (1.06–3.91)* | 182 (56.5) | 1.35 (0.76–2.39) | 96 (29.8) | 2.73 (1.19–6.23)* | |||

| 26–45 | 592 (50.9) | 155 (26.2) | p<0.001 | 2.07 (1.30–3.30)** | 219 (37.0) | p<0.001 | 1.43 (0.99–2.08) | 93 (15.7) | p<0.001 | 3.23 (1.72–6.31)*** |

| > 45 | 249 (21.4) | 33 (13.3) | Ref | 60 (24.1) | Ref | 13 (5.2) | Ref | |||

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Male | 217 (18.7) | 56 (25.8) | 0.188 | 73 (33.6) | 0.046 | Ref | 27 (12.4) | 0.037 | Ref | |

| Female | 946 (81.3) | 288 (30.4) | 388 (41.0) | 1.49 (1.06–2.10)* | 175 (18.5) | 1.83 (1.14–2.95)* | ||||

| Ethnicity | ||||||||||

| Malay | 882 (75.8) | 254 (28.8) | 362 (41.0) | 1.09 (0.64–1.86) | 154 (17.5) | |||||

| Chinese | 100 (8.6) | 34 (34.0) | 0.320 | 39 (39.0) | 0.039 | 0.69 (0.35–1.36) | 22 (22.0) | 0.202 | ||

| Indian | 108 (9.3) | 29 (26.9) | 29 (26.9) | 0.50 (0.25–0.99)* | 12 (11.1) | |||||

| Bumiputera Sabah/ Sarawak/ Others | 73 (6.3) | 27 (37.0) | 31 (42.5) | Ref | 14 (19.2) | |||||

| Marital Status | ||||||||||

| Never married | 490 (42.1) | 223 (45.5) | p<0.001 | 1.71 (0.92–3.16) | 262 (53.5) | p<0.001 | 1.40 (0.82–2.40) | 136 (27.8) | p<0.001 | 2.05 (0.94–4.46) |

| Ever married | 673 (57.9) | 121 (18.0) | Ref | 199 (29.6) | Ref | 66 (9.8) | Ref | |||

| Have child/ children | ||||||||||

| Yes | 595 (51.2) | 104 (17.5) | p<0.001 | Ref | 172 (28.9) | p<0.001 | Ref | 58 (9.7) | p<0.001 | Ref |

| No | 568 (48.8) | 240 (42.3) | 1.17 (0.65–2.09) | 289 (50.9) | 1.17 (0.71–1.92) | 144 (25.4) | 0.93 (0.44–1.96) | |||

| Highest educational level | ||||||||||

| Secondary and below | 78 (6.7) | 12 (15.4) | 0.004 | Ref | 18 (23.1) | 0.002 | Ref | 6 (7.7) | 0.019 | Ref |

| Tertiary | 1085 (93.3) | 332 (30.6) | 1.82 (0.89–3.71) | 443 (40.8) | 1.80 (0.99–3.250 | 196 (18.1) | 1.85 (0.72–4.71) | |||

| Occupation type | ||||||||||

| Professional and managerial | 589 (50.6) | 116 (19.7) | Ref | 187 (31.7) | Ref | 66 (11.2) | Ref | |||

| General worker | 84 (7.2) | 16 (19.0) | p<0.001 | 0.85 (0.45–1.62) | 21 (25.0) | p<0.001 | 0.71 (0.41–1.23) | 4 (4.8) | p<0.001 | 0.39 (0.13–1.14) |

| Housewife/ Retired/ Other | 150 (12.9) | 38 (25.3) | 1.20 (0.73–1.96) | 51 (34.0) | 1.04 (0.68–1.60) | 21 (14.0) | 1.39 (0.77–2.52) | |||

| Student | 340 (29.2) | 174 (51.2) | 1.79 (1.12–2.86)* | 202 (59.4) | 1.84 (1.19–2.85)** | 111 (32.6) | 2.03 (1.18–3.56)* | |||

| Monthly average household income (MYR) | ||||||||||

| 4000 and below | 522 (44.9) | 199 (38.1) | 0.90 (0.59–1.39) | 244 (46.7) | 1.03 (0.70–1.52) | 113 (21.6) | 0.49 (0.30–0.80)** | |||

| 4001–8000 | 370 (31.8) | 76 (20.5) | p<0.001 | 0.81 (0.53–1.24) | 120 (32.4) | p<0.001 | 0.92 (0.64–1.32) | 36 (9.7) | p<0.001 | 0.43 (0.26–0.71)** |

| >8000 | 271 (23.3) | 69 (25.5) | Ref | 97 (35.8) | Ref | 53 (19.6) | Ref | |||

| Perceived current financial status | ||||||||||

| Poor | 125 (10.7) | 71 (56.8) | 2.63 (1.51–4.59)** | 67 (53.6) | 1.28 (0.76–2.14) | 40 (32.0) | 1.93 (1.03–3.61)* | |||

| Medium | 732 (62.9) | 211 (28.8) | p<0.001 | 1.36 (0.93–1.98) | 296 (40.4) | p<0.001 | 1.27 (0.92–1.76) | 124 (16.9) | p<0.001 | 1.46 (0.93–2.29) |

| Good | 306 (26.3) | 62 (20.3) | Ref | 98 (32.0) | Ref | 38 (12.4) | Ref | |||

| Locality | ||||||||||

| Urban | 723 (62.2) | 212 (29.3) | 268 (37.1) | 126 (17.4) | ||||||

| Sub-urban | 304 (26.1) | 91 (29.9) | 0.969 | 137 (45.1) | 0.053 | 54 (17.8) | 0.919 | |||

| Rural | 136 (11.7) | 41 (30.1) | 56 (41.2) | 22 (16.2) | ||||||

| Region | ||||||||||

| Northern | 157 (13.5) | 56 (35.7) | 0.70 (0.36–1.33) | 61 (38.9) | 33 (21.0) | |||||

| Southern | 80 (6.9) | 23 (28.8) | 0.95 (0.62–1.45) | 34 (42.5) | 11 (13.8) | |||||

| Central | 697 (59.9) | 214 (30.7) | 0.042 | 0.66 (0.38–1.14) | 278 (39.9) | 0.877 | 127 (18.2) | 0.212 | ||

| East Coast | 186 (16.0) | 39 (21.0) | 1.12 (0.49–2.55) | 69 (37.1) | 23 (12.4) | |||||

| Borneo Island | 43 (3.7) | 12 (27.9) | Ref | 19 (44.2) | 8 (18.6) | |||||

| Health status | ||||||||||

| Diagnosed with any chronic diseases | ||||||||||

| Yes | 99 (8.5) | 35 (35.4) | 0.205 | 45 (45.5) | 0.238 | 21 (21.2) | 0.331 | |||

| No | 1064 (91.5) | 309 (29.0) | 416 (39.1) | 181 (17.0) | ||||||

| Perceived health status | ||||||||||

| Very good/ Good | 999 (85.9) | 233 (23.3) | p<0.001 | Ref | 351 (35.1) | p<0.001 | Ref | 133 (13.3) | p<0.001 | Ref |

| Fair/ Poor/ Very poor | 164 (14.1) | 111 (67.7) | 5.68 (3.81–8.47)*** | 110 (67.1) | 3.50 (2.37–5.17)*** | 69 (42.1) | 3.66 (2.46–5.45)*** | |||

| COVID-19 experience | ||||||||||

| Ever known anyone infected or died of COVID-19 | ||||||||||

| Yes | 272 (23.4) | 70 (25.7) | 0.129 | 114 (41.9) | 0.396 | 38 (14.0) | 0.100 | |||

| No | 891 (76.6) | 274 (30.8) | 347 (38.9) | 164 (18.4) |

*,p<0.05

**p<0.01

***p<0.001

aHosmer–Lemeshow test, chi-square: 8.048, p-value: 0.429; Nagelkerke R2: 0.280

bHosmer–Lemeshow test, chi-square: 9.609, p-value: 0.294; Nagelkerke R2: 0.180

cHosmer–Lemeshow test, chi-square: 6.584, p-value: 0.582; Nagelkerke R2: 0.229

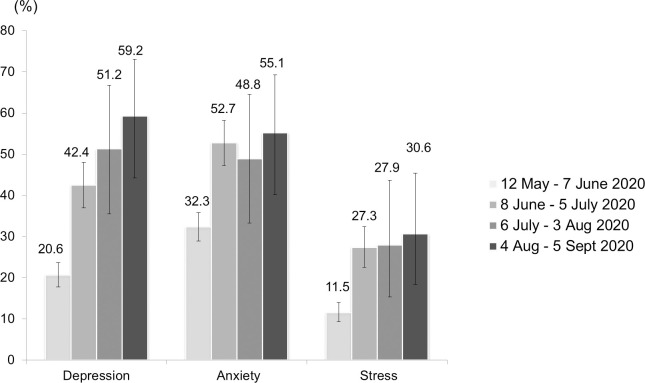

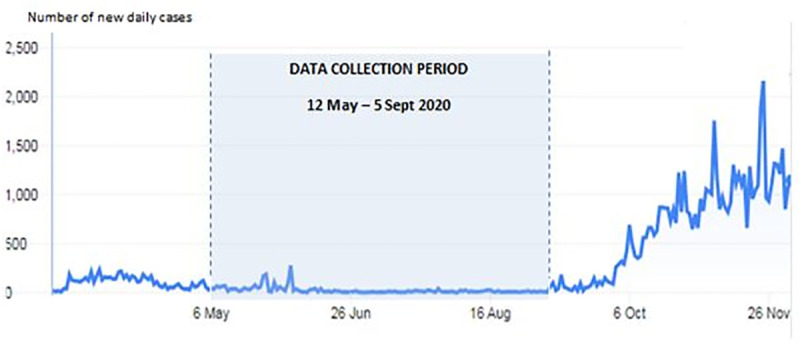

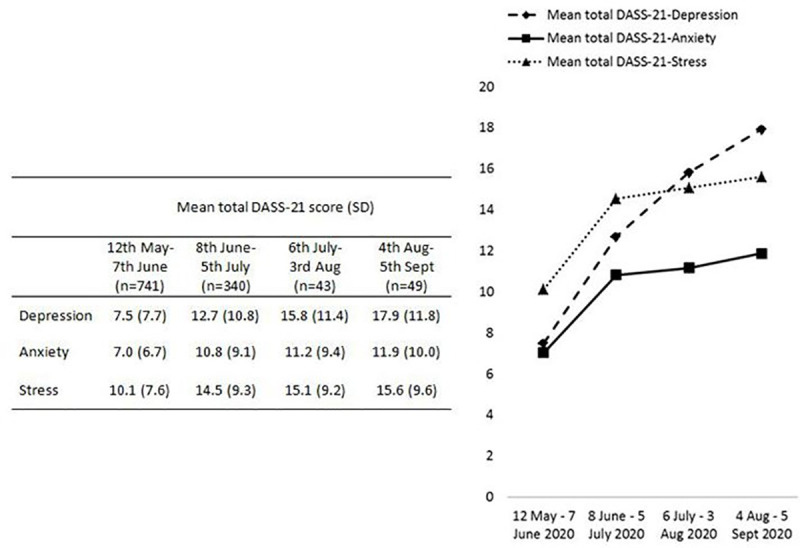

Fig 1 shows the trend of confirmed COVID-19 cases in Malaysia and the recruitment period. Fig 2 shows the temporal trend of the average DASS-21-D, DASS-21-A and DASS-21-S subscale scores across the four successive time periods in the 16-week data collection period. The average DASS-21-S score (M = 10.1, SD = 7.6) during the first four weeks of data collection was higher than the average DASS-21-D (M = 7.5, SD = 7.7) and DASS-21-A (M = 7.0, SD = 6.7) scores. The average DASS-21-D score was markedly elevated across the data collection period. The average DASS-21-D score (M = 17.9, SD = 11.8) was highest in the last four weeks of the data collection period, followed by the DASS-21-S (M = 15.6, SD = 9.6) and DASS-21-A (M = 11.9, SD = 10.0) scores. Fig 3 shows the percentage of participants with depressive, anxiety and stress symptoms according to the DASS-21 scores for each time period. The highest percentage of respondents reported anxiety (32.3%), followed by depressive (20.6%) and stress (11.5%) symptoms in the first time period (12 May–7 June 2020). In the fourth time period (4 August–5 September 2020), a higher percentage reported depressive (59.2%) and anxiety (55.1%) symptoms compared with stress (30.6%) symptoms.

Fig 1. Data collection period and the trend of confirmed cases of COVID-19 in Malaysia.

Fig 2. Temporal changes in mean total DASS-21 score at different time point.

Fig 3. Proportion of participants with the presence of depressive, anxiety and stress symptoms by the four time point of the study period.

Table 2 shows the percentage of participants with depressive, anxiety and stress symptoms and their associated factors during the 16-week study period. On average, depressive, anxiety and stress symptoms were reported in 21.3% (n = 344), 28.6% (n = 461) and 12.5% (n = 202), respectively, of the participants during the study period. Multivariable logistic regression analysis showed that the 18–25-year-old and 26–45-year-old groups had twice the odds for depressive symptoms than the > 45-year-old group. Students and participants who perceived a poor financial status reported a significantly higher likelihood of depressive symptoms. Females reported a significantly higher likelihood of having anxiety disorder than males (OR = 1.49, 95% CI 1.06–2.10). Students had higher odds of anxiety symptoms than the professional and managerial occupational groups (OR = 1.84, 95% CI 1.19–2.85).

In the multivariable regression analysis of factors influencing stress symptoms, the 25–45-year-old group (OR = 3.23, 95% CI 1.72–6.31) and the 18–25-year-old group (OR = 2.73, 95% CI 1.19–6.23) showed higher odds of stress symptoms than the > 45-year-old group. Those who perceived a poor financial status (OR = 1.93, 95% CI 1.03–3.61) had nearly 2 times higher odds of stress symptoms than those who perceived a good financial status. Although a higher percentage of participants with a monthly income < MYR4000 reported stress symptoms, in the multivariable logistic regression analysis, the highest income group had higher odds of stress symptoms. Perceived health status was the strongest significant predictor for depressive and anxiety symptoms. The odds of depression (OR = 5.68, 95% CI 3.81–8.47) and anxiety (OR = 3.50, 95% CI 2.37–5.17) were markedly higher in respondents who perceived a poorer health status.

This study examined the depressive, anxiety and stress symptoms of the Malaysian public during the implementation of a CMCO and RMCO and explored its associated factors using a cross-sectional study design. The data collection period was between the second and third waves of the COVID-19 pandemic in Malaysia, and the country is still facing the continuous threat of the disease.

In this study, responses were obtained during the period when the government imposed more lenient containment measures, and the results revealed increasing levels of depressive, anxiety and stress symptoms throughout the study duration. In line with previous studies from Hong Kong [19] and the United Kingdom [20], the public seemed to experience increased symptoms of mental illness as the pandemic progressed over time. Although psychological well-being of the public is expected to improve when restrictions were lifted, nonetheless, the negative mental impact of the people in this study did not decline despite the shift from CMCO to RMCO. The psychological impact continues to rise across the CMCO and RMCO phase. The increase in mental disorders over time can perhaps be seen as part of the continuous economic and societal consequences as the pandemic has progressed. Many countries, including Malaysia, continue to adopt unprecedented physical distancing policies. As the banning of mass gatherings, work-from-home policies and virtual meetings have been put into place during the COVID-19 pandemic, many industries have been affected negatively. Many individuals continue to suffer mentally as economic consequences continue, in addition to restrictions on social activities and prolonged confinement to their homes.

It is worth highlighting the marked increase in depressive symptoms compared with anxiety and stress symptoms. This finding implies that the Malaysian public became increasingly vulnerable to depressive disorder as the pandemic continued. Furthermore, during the last four weeks of data collection, when the COVID-19 pandemic moved into its seventh month in Malaysia, the percentage of participants with depressive symptoms was highest: the prevalence of depression among the study participants was close to 60% based on the DASS-21-D score. Of note, depression is a leading cause of disability around the world and contributes greatly to the global burden of disease [21]. In addition, the percentage of anxiety (55.1%) and stress (30.6%) symptoms were highest at the end of the data collection period. These findings further indicate the seriousness of overall mental health problems as the COVID-19 pandemic has progressed. There is evidence that mental disorders are associated with suicidal ideations and attempts [22]. Specifically, depression was found to be the main risk factors associated with suicidal behaviours [23, 24]. Malaysia has seen a rise in suicide cases and attempts during the COVID-19 pandemic [25, 26]. These findings warrant urgent monitoring of the Malaysian population’s mental health and prompt provision of counselling to mitigate the detrimental impact on society.

In this study, the 18–25-year-old group, followed by the 26–45-year-old group, reported more anxiety, depressive and stress symptoms. Most of the 18–25-year-old respondents were college or university students. Several population-based surveys have also revealed that students report a higher prevalence of depressive, anxiety and stress symptoms [27, 28]. Studies on student populations throughout the world [29–31], including in Malaysia [32], have shown that the COVID-19 pandemic has put a strain on their mental health. The main reasons for students experiencing heightened psychological distress include economic effects, changes in academic activities, difficulties adapting to online distance learning methods and uncertainty about the future with regard to academics and careers. Given the unprecedented COVID-19 crisis and uncertainly with regard to how long schools will remain closed, the findings suggest the importance of closely monitoring students’ mental health status and providing psychological counseling or mental health services. Schools and health authorities should work together to deliver prompt psychological support to affected students.

This study found a higher prevalence of depressive, anxiety, stress symptoms in women compared with men. Specifically, the multivariable analyses revealed a significant increased risk of anxiety and stress in females compared with males. These findings are in line with previous studies from around the world [33–36] as well as Malaysia [5], where women seem to have experienced elevated psychological symptoms related to the COVID-19 pandemic compared with men. The sex difference is in line with evidence suggesting that women are generally more vulnerable to stress and anxiety disorders in response to traumatic events, while men show better resilience [37, 38]. It has been suggested that intervention strategies and policies for public health emergencies should consider a gender-specific approach to address mental health inequities [39].

Financial distress due to the pandemic has been reported as a key correlate of poor mental health [40]. In this study, univariable analyses revealed that higher income and perceived financial status were well associated with better mental health outcomes. However, in the multivariable analyses, only perceived financial status was a significant predictor of better mental health outcomes. This could possibly be explained because being a high-income earner does not necessarily imply a strong financial situation. By contrast, people with strong financial situations–for example, with adequate savings–showed stronger resilience to the financial crisis during the COVID-19 pandemic. The findings indicate that minimising financial disruption during the COVID-19 pandemic should be a central goal of public health policy.

In this study, people with a fair, poor or very poor health status were more likely to report negative mental health impacts compared with those with a very good or good health status. In addition, health status was the strongest predictor for depressive and anxiety symptoms in the multivariable regression findings. These findings are in line with a recent study reporting that individuals with more medical comorbidities were more likely to report elevated depressive symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic [41]. A study found that reduced access to routine medical care during the pandemic resulted in greater mental health among people with medical comorbidities [41]. This could be the indicator that psychological strain of pre-existing medical comorbidities may have been further increased during the COVID-19 pandemic. Other unprecedented life situations during the pandemic, including job loss, financial hardship and sedentary behaviours, may also worsen preexisting comorbidities and thereby exacerbate mental health problems. The consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of people with pre-existing health conditions warrant ensuring patients’ are sufficiently self-aware to realise when they need to seek help. In addition, family members and providers should be encouraged to support individuals to promote help-seeking behaviour. People with pre-existing comorbidities would need extra support to cultivate resilience, coping, mindfulness and healthy adjustment with the change to an inactive, sedentary lifestyle to enhance their mental wellbeing during the pandemic.

Some limitations of our study should be noted. The first limitation is the cross-sectional design: we identified associations but could not infer cause and effect. Another potential issue is the influence of selection bias on the prevalence of mental health problems seen in this sample. We were careful to ensure that the recruitment advertisement did not mention the topic of mental health; we advertised the study as a ‘COVID-19 Health and Wellbeing Survey’. Nonetheless, it is possible that people experiencing psychological distress or mental health consequences were more likely to respond to the survey. It is also important to note that online survey methods may lead to a biased response towards people who have good Internet literacy and access as well as those who are more educated. This bias may have a disproportionate impact on subsections of the population, such as high percentage of participants in this study who have a diploma or are university graduates. The study also has a higher representation of female participants. Nonetheless, we did obtain a sample that was relatively representative of the Malaysian population based on age and location. It is also important to note that our study used both the English and the Bahasa Malaysia version of DASS-21 in the same questionnaire. To our best knowledge, the measurement of invariance across the English and Bahasa Malaysia version of DASS-21 has never been examined before. Unfortunately, the measurement invariance across the English and Bahasa Malaysia version of DASS-21 was unable to be determined in our bilingual survey link. In the absence of measurement invariance procedures across the English and Bahasa Malaysia version of DASS-21 in this study, the psychometric robustness associated with different interpretations of items in the two languages was unknown. Testing for and assuring measurement invariance across different languages, culture or group comparisons is essential [42–44]. Future studies on DASS-21 should include validation across different group comparisons and testing of invariance of all versions. Lastly, the study is also limited by the small number of responses in the last two time periods, hence results should be interpreted with caution. Despite these limitations, our results are in line with many previous studies.

Conclusion

Our study shows that mental health symptoms, especially depression and anxiety, have been overwhelmingly prevalent in the Malaysian population as the COVID-19 pandemic has progressed. Although the number of COVID-19 cases during the data collection period was relatively low, there was a continuous increase in the percentage of respondents with depressive, anxiety and stress symptoms, implying a cumulative mental health burden. The increase in the rate of depression was most rapid, and the rate of depression was dramatically high as the COVID-19 pandemic moved into its seventh month in Malaysia. Poor health status was the strongest significant predictor for depressive and anxiety symptoms. By demographics, young people, particularly students, females and people with poor financial conditions, were more vulnerable to mental health symptoms. These findings emphasise the necessity of monitoring mental health disorders among the public during the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequently providing targeted interventions for people at elevated risks, as identified in this study.

Acknowledgments

We thank the assistance provided by all members in the Caring Together team.

Data Availability

All data files are available in the Kaggle database (www.kaggle.com/dataset/47a1daa9618fcb790d61e4c5cfa20363f2404c334e982d5499bf73aa8966179a).

Funding Statement

This research was supported by Universiti Malaya COVID-19 Implementation Research Grant (RG564-2020HWB), which was granted to Ivy Chung. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.WHO Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. [Cited 2020 Nov 27] Available from https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019

- 2.CDC. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). [Cited 2020 Nov 27]. Available from https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/summary.html

- 3.Nicola M, Alsafi Z, Sohrabi C, Kerwan A, Al-Jabir A, Iosifidis C, et al. The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): A review. International journal of surgery (London, England). 2020;78:185. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.04.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ibn-Mohammed T, Mustapha KB, Godsell JM, Adamu Z, Babatunde KA, Akintade DD, et al. A critical review of the impacts of COVID-19 on the global economy and ecosystems and opportunities for circular economy strategies. Resources, Conservation and Recycling. 2020:105169. 10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.105169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wong LP, Alias H (2020) Temporal changes in psychobehavioural responses during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic in Malaysia. J. Behav. Med. 10.1007/s10865-020-00172-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adnan N, Nordin SM. How COVID 19 effect Malaysian paddy industry? Adoption of green fertilizer a potential resolution. Environment, development and sustainability. 2020. September 30:1–41. 10.1007/s10668-020-00978-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Osterrieder A, Cuman G, Pan-ngum W, Cheah PK, Cheah PK, Peerawaranun P, et al. Economic and social impacts of COVID-19 and public health measures: results from an anonymous online survey in Thailand, Malaysia, the United Kingdom, Italy and Slovenia. Preprint. medRxiv. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xiong J, Lipsitz O, Nasri F, Lui LM, Gill H, Phan L, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. Journal of affective disorders. 2020; 277: 55–64. 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elengoe A. COVID-19 Outbreak in Malaysia. Osong Public Health and Research Perspectives. 2020; 11(3):93. 10.24171/j.phrp.2020.11.3.08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perveen A, Hamzah H, Ramlee F, Othman A, Minhad M. Mental Health and Coping Response among Malaysian Adults during COVID-19 Pandemic Movement Control Order. Journal of Critical Reviews. 2020;7(18):653–60. 10.31838/jcr.07.18.90 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henry JD, Crawford JR. The short‐form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS‐21): Construct validity and normative data in a large non‐clinical sample. British journal of clinical psychology. 2005;44(2):227–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lovibond SH, Lovibond PF. Manual for the depression anxiety stress scales. Psychology Foundation of Australia; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oei TP, Sawang S, Goh YW, Mukhtar F. Using the depression anxiety stress scale 21 (DASS‐21) across cultures. International Journal of Psychology. 2013;48(6):1018–29. 10.1080/00207594.2012.755535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Musa R, Fadzil MA, Zain ZA. Translation, validation and psychometric properties of Bahasa Malaysia version of the Depression Anxiety and Stress Scales (DASS). ASEAN Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;8(2):82–9. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Musa R, Maskat R. Psychometric Properties of Depression Anxiety Stress Scale 21-item (DASS-21) Malay Version among a Big Sample Population. Mediterranean Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2020;8(1). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hosmer DW Jr, Lemeshow S, Sturdivant RX. Applied logistic regression. John Wiley & Sons; 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Department of Statistics Malaysia. Population Quick Info. Population by states and age, Malaysia, 2019. [Cited 2020 December 2]. Available from http://pqi.stats.gov.my/result.php?token=ead145b6134eacd515fcbbb52b79fcd1. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Department of Statistics Malaysia. Household Income And Basic Amenities Survey Report 2019. [Cited 2020 December 2]. Available from from https://www.dosm.gov.my/v1/uploads/files/1_Articles_By_Themes/Prices/HIES/HIS-Report/HIS-MALAYSIA.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wong SY, Zhang D, Sit RW, Yip BH, Chung RY, Wong CK, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on loneliness, mental health, and health service utilisation: a prospective cohort study of older adults with multimorbidity in primary care. British Journal of General Practice. 2020;70(700):e817–24. 10.3399/bjgp20X713021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pierce M, Hope H, Ford T, Hatch S, Hotopf M, John A, et al. Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(10):883–92. 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30308-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.WHO. Depression. [Cited 2020 December 5]. Available friom https://www.who.int/health-topics/depression#tab=tab_1

- 22.Chesney E, Goodwin GM, Fazel S. Risks of all‐cause and suicide mortality in mental disorders: a meta‐review. World psychiatry. 2014;13(2):153–60. 10.1002/wps.20128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cavanagh JTO, Carson AJ, Sharpe M, Lawrie SM. Psychological autopsy studies of suicide: a systematic review. Psychol Med. 2003;33(3):395–405. 10.1017/s0033291702006943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li Z, Page A, Martin G, Taylor R. Attributable risk of psychiatric and socio-economic factors for suicide from individual-level, population-based studies: a systematic review. Soc Sci Med 2011;72(4):608–16. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kamel H. The Malaysian Reserve. Suicide cases on the rise amid pandemic. 2020. November 11. [Cited 2020 December 5]. Available from https://themalaysianreserve.com/2020/11/11/suicide-cases-on-the-rise-amid-pandemic/. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Express Daily. 266 commit suicide during movement restrictions (one everyday). 2020. November 18. [Cited 2020 Dec 5]. https://www.dailyexpress.com.my/news/161783/266-commit-suicide-during-movement-restrictions-one-everyday-/ [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, Tan Y, Xu L, Ho CS, et al. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2020;17(5):1729. 10.3390/ijerph17051729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rajkumar RP. COVID-19 and mental health: A review of the existing literature. Asian journal of psychiatry. 2020:102066. 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hasan N, Bao Y. Impact of “e-Learning crack-up” perception on psychological distress among college students during COVID-19 pandemic: A mediating role of “fear of academic year loss”. Children and Youth Services Review. 2020;118:105355. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burns D, Dagnall N, Holt M. Assessing the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on student wellbeing at universities in the UK: a conceptual analysis. InFrontiers in Education 2020. October 14 (Vol. 5). Frontiers Media. 10.3389/feduc.2020.582882 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kecojevic A, Basch CH, Sullivan M, Davi NK. The impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on mental health of undergraduate students in New Jersey, cross-sectional study. PloS one. 2020;15(9):e0239696. 10.1371/journal.pone.0239696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sundarasen S, Chinna K, Kamaludin K, Nurunnabi M, Baloch GM, Khoshaim HB, et al. Psychological impact of Covid-19 and lockdown among university students in Malaysia: Implications and policy recommendations. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2020. January;17(17):6206. 10.3390/ijerph17176206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salari N, Hosseinian-Far A, Jalali R, Vaisi-Raygani A, Rasoulpoor S, Mohammadi M, et al. Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Globalization and health. 2020. December;16(1):1–1. 10.1186/s12992-019-0531-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hou F, Bi F, Jiao R, Luo D, Song K. Gender differences of depression and anxiety among social media users during the COVID-19 outbreak in China: a cross-sectional study. BMC public health. 2020;20(1):1–1. 10.1186/s12889-019-7969-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blbas HT, Aziz KF, Nejad SH, Barzinjy AA. Phenomenon of depression and anxiety related to precautions for prevention among population during the outbreak of COVID-19 in Kurdistan Region of Iraq: based on questionnaire survey. Journal of Public Health. 2020:1–5. 10.1007/s10389-020-01325-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schäfer S, Sopp R, Schanz C, Staginnus M, Göritz AS, Michael T. Impact of COVID-19 on public mental health and the buffering effect of sense of coherence. Psychother Psychosom 2020;89:386–392. 10.1159/000510752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McLean CP, Asnaani A, Litz BT, Hofmann SG. Gender differences in anxiety disorders: prevalence, course of illness, comorbidity and burden of illness. J. Psychiatr. Res 2011; 45:1027–35. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.03.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Axinn WG, Ghimire DJ, Williams NE, Scott KM. Gender, traumatic events, and mental health disorders in a rural Asian setting. Journal of health and social behavior. 2013. December;54(4):444–61. 10.1177/0022146513501518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jacques-Aviñó C, López-Jiménez T, Medina-Perucha L, de Bont J, Gonçalves AQ, Duarte-Salles T, et al. Gender-based approach on the social impact and mental health in Spain during COVID-19 lockdown: a cross-sectional study. BMJ open. 2020;10(11):e044617. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-044617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dawel A, Shou Y, Smithson M, Cherbuin N, Banfield M, Calear AL, et al. The effect of COVID-19 on mental health and wellbeing in a representative sample of Australian adults. Frontiers in psychiatry. 2020;11:1026. 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.579985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sherman AC, Williams ML, Amick BC, Hudson TJ, Messias EL. Mental health outcomes associated with the COVID-19 pandemic: Prevalence and risk factors in a southern us state. Psychiatry research. 2020;293:113476. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scholten S, Velten J, Bieda A, Zhang XC, Margraf J. Testing measurement invariance of the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scales (DASS-21) across four countries. Psychological Assessment. 2017;29:1376. 10.1037/pas0000440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bibi A, Lin M, Zhang XC, Margraf J. Psychometric properties and measurement invariance of Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scales (DASS‐21) across cultures. International Journal of Psychology. 2020;55:916–25. 10.1002/ijop.12671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leung H, Pakpour AH, Strong C, Lin YC, Tsai MC, Griffiths MD, et al. Measurement invariance across young adults from Hong Kong and Taiwan among three internet-related addiction scales: Bergen social media addiction scale (BSMAS), smartphone application-based addiction scale (SABAS), and internet gaming disorder scale-short form (IGDS-SF9)(study Part A). Addictive Behaviors. 2020;101:105969. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.04.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]