Abstract

In eukaryotes, 43S preinitiation complex (PIC) formation is a rate-determining step of translation. Ribosome recycling following translation termination produces free 40S subunits for re-assembly of 43S PICs. Yeast mutants lacking orthologs of mammalian eIF2D (Tma64), and either MCT-1 (Tma20) or DENR (Tma22), are broadly impaired for 40S recycling; however, it was unknown whether this defect alters the translational efficiencies (TEs) of particular mRNAs. Here, we conducted ribosome profiling of a yeast tma64∆/tma20∆ double mutant and observed a marked reprogramming of translation, wherein the TEs of the most efficiently translated (‘strong’) mRNAs increase, while those of ‘weak’ mRNAs generally decline. Remarkably, similar reprogramming was seen on reducing 43S PIC assembly by inducing phosphorylation of eIF2α or by decreasing total 40S subunit levels by depleting Rps26. Our findings suggest that strong mRNAs outcompete weak mRNAs in response to 43S PIC limitation achieved in various ways, in accordance with previous mathematical modeling.

Research organism: S. cerevisiae

Introduction

The initiation of translation in eukaryotes commences with assembly of a 43S preinitiation complex (PIC) on the small (40S) ribosomal subunit, containing the ternary complex (TC), comprised of GTP-bound eukaryotic initiation factor two and methionyl initiator tRNA (eIF2·GTP·Met-tRNAi), and additional eIFs (−1, −1A, and −3). The 43S PIC attaches to the 5’ end of mRNA, in a manner stimulated by the eIF4F complex bound to the m7G cap, and scans the mRNA 5’-untranslated region (5’UTR) for an AUG start codon, producing a stable 48S PIC on AUG selection by Met-tRNAi. The GTP bound to eIF2 can be hydrolyzed during scanning, stimulated by GTPase activating protein eIF5, but eIF1 impedes release of inorganic phosphate (Pi) at non-AUG codons. Start codon recognition triggers dissociation of eIF1 from the 40S subunit, enabling Pi release from eIF2·GDP·Pi and subsequent dissociation of eIF2·GDP and other eIFs from the 48S PIC. The eIF5B-catalyzed joining of the large (60S) subunit produces an 80S initiation complex (IC) ready to begin the elongation phase of protein synthesis (Hinnebusch, 2014; Hinnebusch, 2017).

Several different mRNA features influence the rate of translation initiation. The efficiency of 43S PIC attachment to mRNA and subsequent scanning of the 5’UTR are hindered by stable secondary structures, such that long, structure-laden 5’UTRs are generally inhibitory and impose a requirement for RNA helicases associated with eIF4F, including eIF4A and Ded1, to resolve mRNA structures near the cap, within the 5’UTR, and surrounding the start codon (Sen et al., 2015; Sen et al., 2016; Gupta et al., 2018; Gulay et al., 2020). The nucleotide sequence immediately surrounding the start codon—the ‘Kozak context’—particularly at the −3 and +4 positions (numbered from the A of AUG (+1)) also influences the efficiency of start codon selection, with A nucleotides upstream of the AUG codons enhancing initiation on yeast mRNAs (Shabalina et al., 2004; Zur and Tuller, 2013). Binding of eIF4F to the mRNA cap is stimulated by interaction of its eIF4G subunit with the poly(A)-binding protein (PABP) bound to the poly(A) tail, promoting circularization of the mRNA (Hinnebusch, 2011). Formation of this ‘closed-loop structure’ might facilitate reinitiation by ribosomal subunits released from the stop codon of the mRNA following termination of translation and ribosome recycling (Uchida et al., 2002). There is evidence that closed-loop formation is favored for shorter mRNAs (Amrani et al., 2008), which might help account for the negative correlation between mRNA coding sequence length and translation efficiencies observed in yeast and other eukaryotes (Arava et al., 2003; Thompson et al., 2016). However, theoretical modeling indicates that shorter mRNAs are capable of more efficient recycling of ribosomal subunits from the stop codon to the initiation codon without a mechanism for promoting circularization via end-to-end interactions (Fernandes et al., 2017). The abundance of mRNA is also associated with efficient translation, presumably reflecting the need for mRNAs encoding highly expressed proteins to be both abundant—highly transcribed and stable—and optimized for translation.

Translation initiation can also be modulated by altering the activities of general initiation factors. The function of eIF2 in Met-tRNAi recruitment is inhibited in response to various stresses by phosphorylation of serine-51 of its α-subunit, as phosphorylated eIF2·GDP acts as a competitive inhibitor of eIF2B, the guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) for eIF2. Inhibition of eIF2B reduces assembly of the TC and thereby decreases formation of 43S PICs, attenuating bulk translation initiation in the cell (Pavitt, 2018). Reducing TC levels also stimulates the translation of certain mRNAs by blunting the inhibitory effects of upstream open-reading-frames (uORFs) present in their 5’UTRs (Hinnebusch, 2005; Hinnebusch et al., 2016). Such uORFs are encountered by scanning 43S PICs first, and their translation generally diminishes the number of PICs that reach the main coding sequences (CDS) downstream owing to recycling of ribosomes following termination at the uORF stop codons. Limited reductions in TC by eIF2α phosphorylation allow uORF start codons to be skipped by scanning PICs with attendant increased translation of the main CDS, by various mechanisms. For yeast GCN4 mRNA, encoding a transcriptional activator of amino acid biosynthetic genes, translation of the first of four uORFs gives rise to 40S subunits that escape recycling at the uORF1 stop codon and resume scanning downstream. At high TC levels, they quickly rebind TC and reinitiate at uORFs 3 or 4, and are efficiently recycled from the mRNA following uORF translation. When TC levels are reduced by eIF2α phosphorylation, catalyzed by protein kinase Gcn2 on amino acid starvation, a fraction of scanning 40S subunits fails to rebind TC until after bypassing all four uORFs, but then bind TC in time to reinitiate at the main GCN4 CDS instead, thereby inducing GCN4 translation (Hinnebusch, 2005).

Ribosome recycling entails the splitting and release of 80S ribosomes from mRNA at the stop codon following polypeptide chain termination, and occurs in two stages. Dissociation of the 60S subunit from the 80S post-termination complex (post-TerC) occurs first, catalyzed by ABCE1 (Rli1 in yeast), leaving a 40S subunit with the stop codon in the A site and deacylated tRNA in the P site corresponding to the last translated codon of the ORF (Young et al., 2015; Hellen, 2018). The second stage of recycling, dissociation of the tRNA and 40S subunit from the mRNA, is stimulated in vitro by eIF2D, or by the heterodimer MCT-1/DENR, which exhibit homology to separate regions of eIF2D (Skabkin et al., 2010). eIF2D could also stimulate reinitiation of translation by reconstituted mammalian 40S post-TerCs by releasing the deacylated tRNA and making the P site available for recruiting Met-tRNAi via the TC (Skabkin et al., 2013). Structural analysis shows that human MCT-1/DENR can bind to the 40S decoding center and contact both ends of tRNAi in a model reinitiation intermediate (Weisser et al., 2017), suggesting their likely positions in a 40S post-TerC. Both DENR and MCT-1 have been shown to promote translation reinitiation downstream of uORFs with strong Kozak consensus sequences in Drosophila and HeLa cells, although the sensitive uORFs in human cells are extremely short, encoding only one amino acid (Schleich et al., 2014; Schleich et al., 2017). Other recent findings implicate DENR in promoting reinitiation following uORF translation on certain mRNAs in mouse cells, including that for the CLOCK gene, although the relevant uORFs were not the single-codon variety (Castelo-Szekely et al., 2019). Interestingly, in reconstituted mammalian systems, eIF2D and MCT-1/DENR were found capable of substituting for eIF2 in GTP-independent recruitment of Met-tRNAi to the 40S subunit during primary initiation events on certain mRNAs where the AUG codon is placed in the P site without prior scanning, including leaderless mRNAs, mRNAs containing an internal ribosome entry site, or mRNAs with unstructured A-rich 5’UTRs (Dmitriev et al., 2010; Skabkin et al., 2010).

Recently, we showed that yeast mutants lacking the genes for both eIF2D (Tma64) and either MCT-1 (Tma20) or DENR (Tma22) exhibit phenotypes consistent with a broad defect in 40S recycling, including a queuing of translating 80S ribosomes immediately upstream of main CDS stop codons, and increased reinitiation at AUG codons in 3’UTRs. At certain genes, it appeared that unrecycled 40S ribosomes could rejoin with 60S subunits and undergo unconventional 80S reinitiation events in the 3’UTRs (Young et al., 2018), a process observed previously for unrecycled 80S post-TerCs in cells depleted of ABCE1/Rli1 (Young et al., 2015). The ability of Tma64 or Tma20/Tma22 to promote recycling and block reinitiation was also demonstrated in cell extracts with uORF-containing reporter mRNAs (Young et al., 2018). Thus, ostensibly at odds with the findings from mammalian cells where MCT-1/DENR enhance reinititiation following uORF translation, the available evidence suggests that the yeast orthologs of these proteins impede reinitiation by promoting dissociation of 40S post-TerCs from the mRNA. It remains possible, however, that the yeast Tma proteins stimulate, rather than inhibit, reinitiation on particular uORF-containing mRNAs in vivo. It is unknown whether Tma64 or Tma20/Tma22 can substitute for eIF2 in Met-tRNAi recruitment during primary initiation events on any native mRNAs in yeast cells in the manner described for their mammalian orthologs in vitro (Dmitriev et al., 2010; Skabkin et al., 2010).

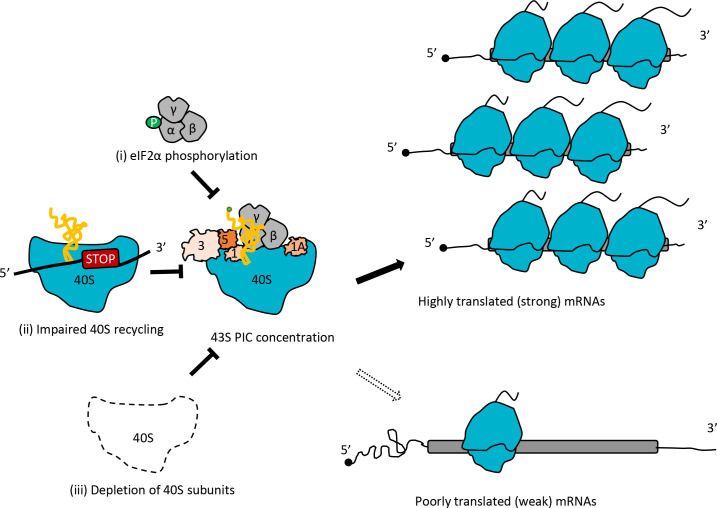

Because ribosome recycling is required to provide 40S subunits needed for assembly of 43S PICs to support new initiation events, we wondered whether defective recycling in yeast cells lacking the Tma proteins would reduce the formation of 43S PICs, which in turn, might differentially affect the translation of mRNAs with different inherent rates of initiation. In this view, changes in translation efficiencies (TEs) observed on depletion of the Tma proteins would result from altered competition among mRNAs for limiting PICs rather than loss of mRNA-specific functions of the Tma proteins in either reinitiation or eIF2-independent primary initiation. To explore this possibility, we conducted ribosome profiling on a tma64∆/tma20∆ double mutant, lacking the yeast orthologs of eIF2D and MCT-1, and compared the TEs of all expressed mRNAs in this mutant to their values in isogenic WT cells. The results indicate that eliminating Tma64/Tma20 leads to a reprogramming of translation that generally favors mRNAs that are more efficiently translated in WT cells and disfavors weakly translated mRNAs. Observing the same general reprogramming of TEs in response to eIF2α phosphorylation in WT cells, or to a reduction in WT 40S subunit levels, we propose that competition among mRNAs for limiting 43S PICs is an important driver of changes in TE in cells impaired for 40S recycling.

Results

Identification of mRNAs dependent on Tma64 or the Tma20/Tma22 heterodimer for efficient translation in yeast cells

Previously, we provided evidence that the yeast counterparts of eIF2D or the MCT-1/DENR heterodimer (Tma64 and Tma20/Tma22, respectively) act in ribosome recycling following the termination of polypeptide synthesis at stop codons. Analysis of a yeast tma64∆/tma20∆ double mutant (tma∆∆) suggested the accumulation of unrecycled 40S post-TerCs stranded at stop codons, with two main consequences: (i) queuing of translating 80S ribosomes immediately upstream of 40S post-TerCs stalled at stop codons; (ii) increased reinitiation by the stalled 40S post-TerCs and attendant translation in adjacent 3’UTRs (Young et al., 2018). Recently, profiling of 40S subunits (as opposed to 80S ribosomes) has confirmed the genome-wide accumulation of unrecycled 40S subunits at stop codons in the tma∆∆ mutant (D. Young, S. Meydan-Marks, and N. Guydosh, personal communication). We wondered whether the sequestration of 40S subunits in 40S post-TerCs stranded at stop codons, or otherwise engaged in scanning or translation within 3’UTRs, in the tma∆∆ mutant would reduce their availability to assemble new 43S preinitiation complexes and thereby diminish the relative translational efficiencies (TEs) of certain mRNAs in the cell.

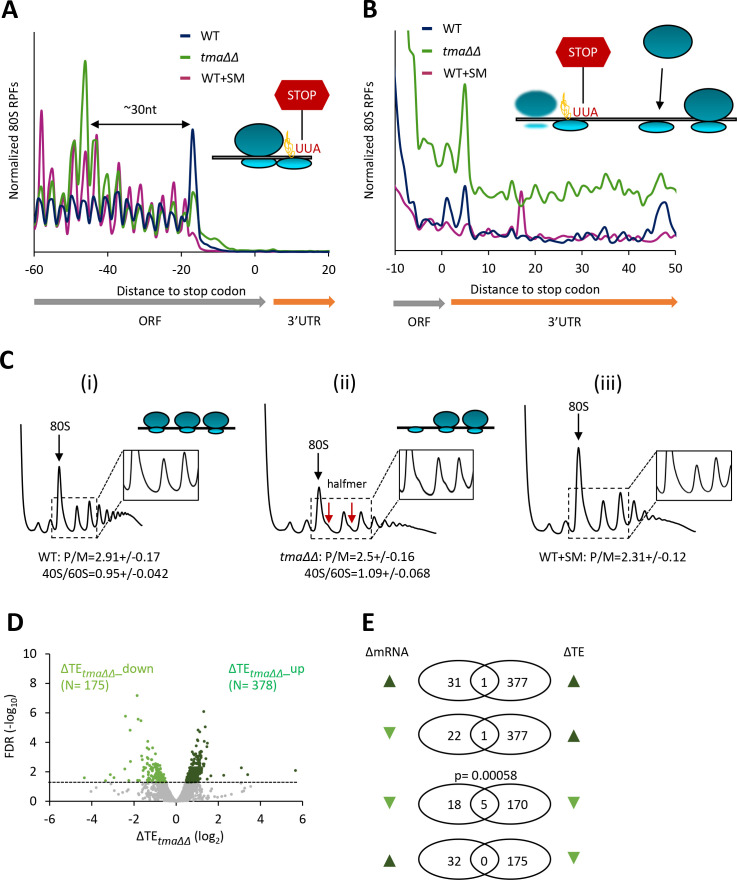

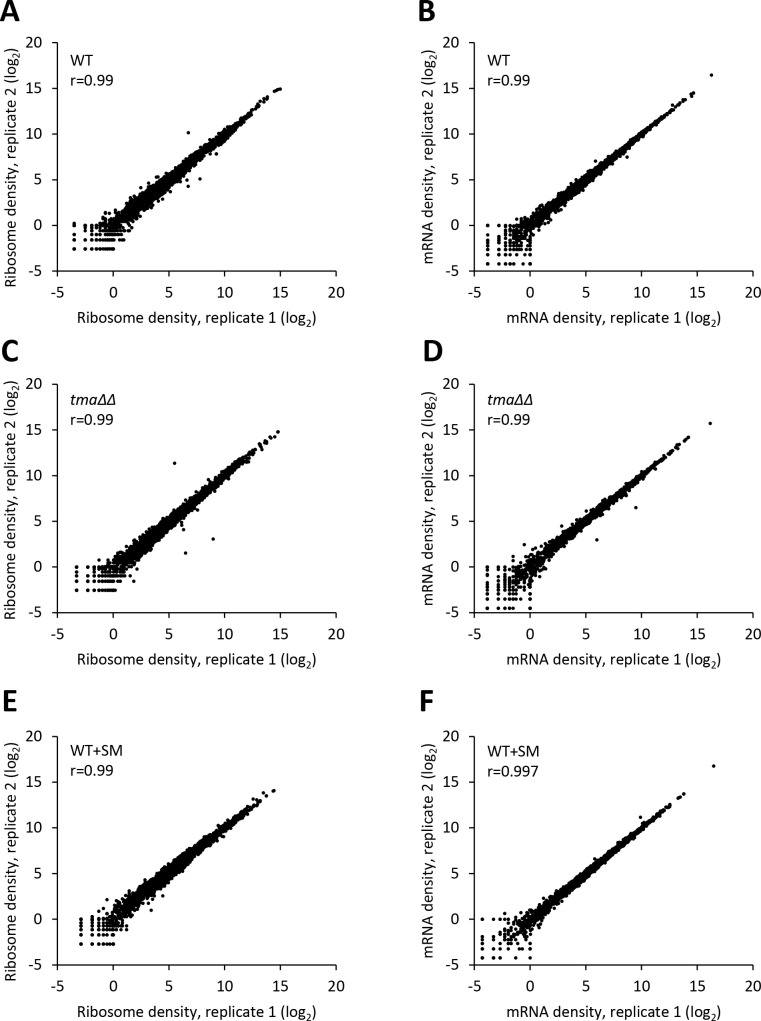

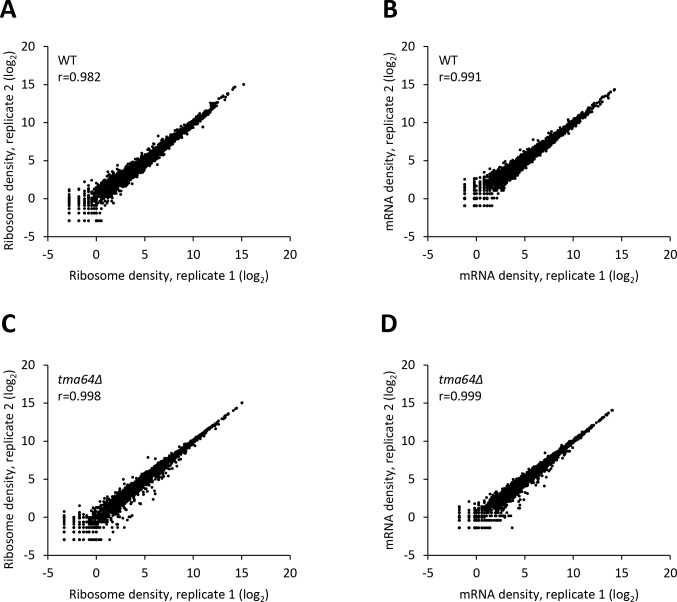

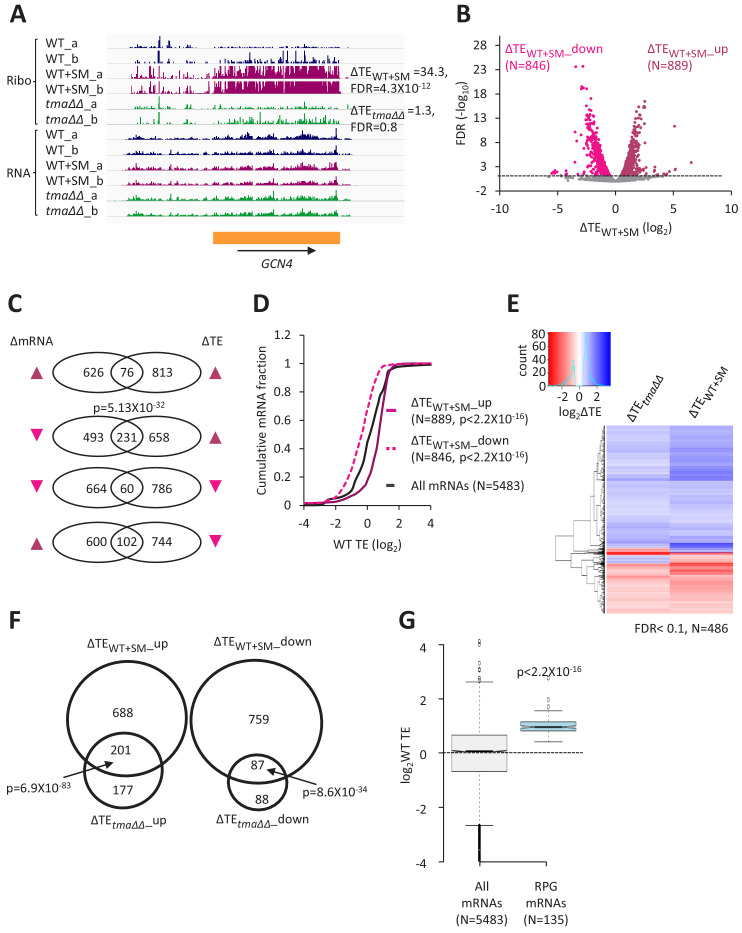

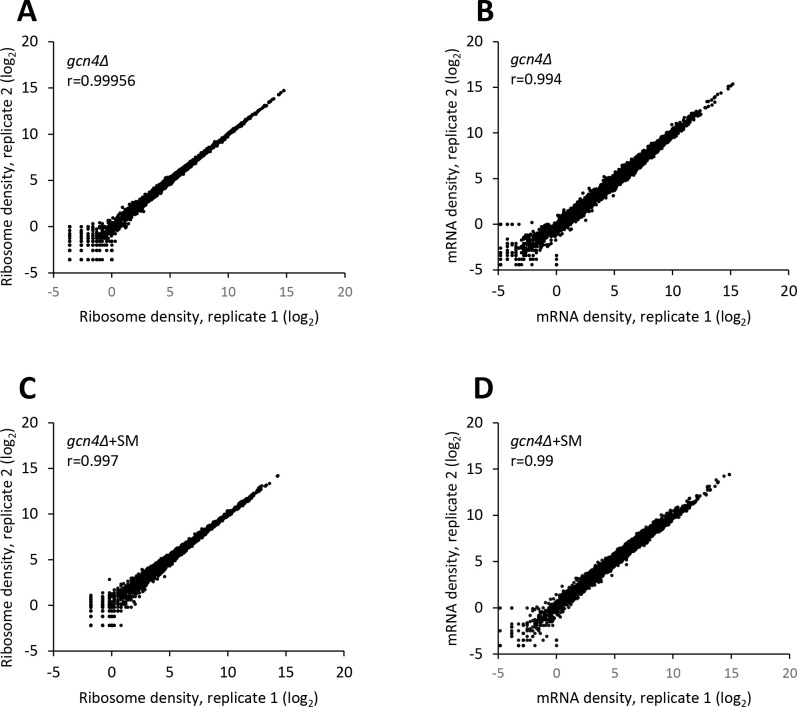

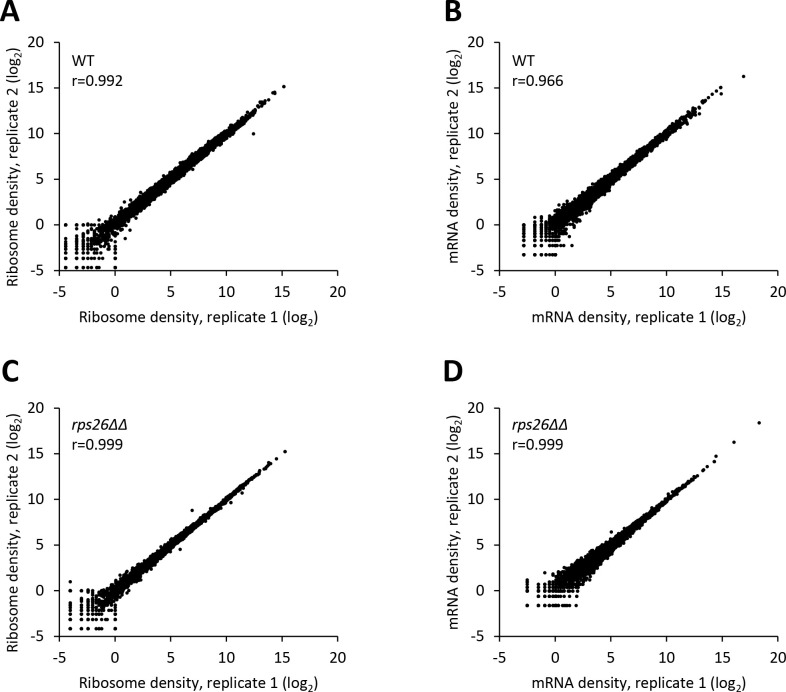

To address this possibility, we used ribosome profiling to measure the relative TEs of all expressed mRNAs in the tma∆∆ mutant compared to the isogenic WT, culturing both strains in synthetic complete (SC) medium. Ribosome profiling entails deep-sequencing of 80S ribosome-protected mRNA fragments (RPFs, or ribosome footprints) in parallel with total RNA. The ratio of sequencing reads of RPFs summed over the coding sequences to the total mRNA reads for the corresponding transcript provides a measure of TE for each mRNA (Ingolia et al., 2009). Owing to normalization of the data for total read number in each library, the RPF and mRNA reads and the calculated TEs are determined relative to the average values for each strain and do not indicate absolute levels of mRNA expression or translation. The RPF and RNA read counts between biological replicates for each strain were highly reproducible (Pearson’s r ≈ 0.99) (Figure 1—figure supplement 1A–D). The normalized RPF counts from all mRNAs aligned at their stop codons for the WT strain showed the expected three nucleotide periodicity and a peak at the stop codon (Figure 1A, blue). As we reported previously for cells cultured in undefined rich medium (YEPD) (Young et al., 2018), the corresponding metagene profile for the tma∆∆ mutant in defined (SC) medium differs from the WT profile in exhibiting a peak ~30 nt upstream of the stop codon (Figure 1A, green versus blue), attributed to queuing of a translating 80S ribosome behind an unrecycled 40S post-TerCs stalled at the stop codon following peptide release and recycling of the large 60S subunit (Figure 1A, schematic). The tma∆∆ mutant also exhibits genome-wide elevated 80S occupancies downstream of stop codons (Figure 1B, green versus blue), indicating increased translation reinitiation in 3’UTRs by unrecycled post-TerCs (Figure 1B, schematic). Thus, key defects associated with impaired 40S recycling following translation termination observed previously in the tma∆∆ mutant cultured in YEPD (Young et al., 2018) were reproduced here in the same mutant grown in SC medium.

Figure 1. Identification of mRNAs exhibiting altered relative TEs on deletion of TMA64/TMA20.

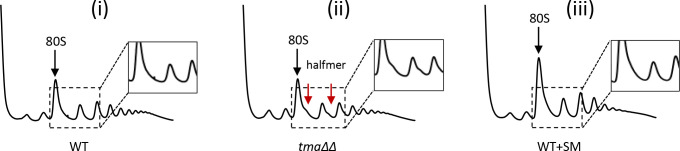

(A) Results from ribosome profiling showing the normalized 80S ribosome reads from all mRNAs aligned with respect to their stop codons, for WT strain BY4741 (blue), the tma∆∆ mutant H4520 (green), and SM-treated WT cells (maroon). Schematics depict queuing of 80S ribosomes 30 nt upstream of the stop codon in the tma∆∆ mutant attributed to 40S post-TerCs stalled at stop codons owing to defective recycling. (B) Expanded view of normalized 80S reads from all mRNAs shown in (A) for the first 50 nt of the 3’UTRs. The schematic depicts resumed scanning by 40S post-TerCs and reinitiation in 3’UTRs. (C) Polysome profiles of the strains in (A). (i)-(ii) Cells cultured in SC medium at 30°C to log-phase and treated with 50 μg/mL of CHX for 5 min before harvesting at 4°C. (iii) WT cells grown as in (i) except in SC-Ile/Val medium and treated with 1 µg/mL SM for 20 min before CHX addition. WCEs were resolved by sedimentation through sucrose gradients and scanned at 260 nm to visualize (from left to right) free 40S and 60S subunits, 80S monosomes, and polysomes. Tracings are magnified in the insets to show halfmer polysome positions (red arrows) in the tma∆∆ mutant, depicted in the schematic above (ii). The mean polysome/monosome (P/M) ratios and free 40S to 60S subunits ratios with ± standard error of the means (SEMs) from five biological replicates are shown. (D) Volcano plot showing the log2 ratios of relative TEs in the tma∆∆ mutant versus WT cells (∆TEtma∆∆ values) for each mRNA (x-axis) versus negative log10 of the False Discovery Rate (FDR) for the ∆TEtma∆∆ changes determined by DESeq2 analysis of ribosome profiling data for the 5405 mRNAs with evidence of translation (y-axis). The dotted line marks the 5% FDR threshold. mRNAs showing a significant increase (∆TEtma∆∆_up) or decrease (∆TEtma∆∆_down) in relative TE in the tma∆∆ mutant versus WT cells at FDR < 0.05, are plotted in dark or light green circles, respectively. (E) Venn diagrams of overlaps between differentially expressed mRNAs (ΔmRNA) (FDR < 0.05 and log2ΔmRNA >1 or <-1) or differentially translated mRNAs (ΔTE, FDR < 0.05) between the tma∆∆ mutant versus WT cells, with arrows indicating increased (up) or decreased (down) mRNA or TE in the tma∆∆ mutant versus WT cells. p values were calculated using Fisher's exact test and were shown only for over-enrichment compared to expectation by chance.

Figure 1—figure supplement 1. Reproducibility between biological replicates of ribosome footprint profiling and RNA-seq analyses for WT, the tma∆∆ mutant, and SM-treated WT.

Figure 1—figure supplement 2. Polysome profiles of WT, the tma∆∆ mutant, and SM-treated WT under the growth conditions used for ribosome profiling and RNA-seq.

Furthermore, we found that the tma∆∆ mutant exhibits a reduced ratio of bulk polysomes to monosomes (P/M) compared to that seen in WT cells (Figure 1C, (ii) versus (i)), consistent with a diminished rate of bulk translation initiation. This strain also exhibits an accumulation of halfmer polysomes, evident as shoulders on the 80S monosome and disome peaks in total polysome profiles, not found in the profiles from WT cells (Figure 1C, (ii) versus (i); Figure 1—figure supplement 2 (ii) versus (i)). The usual explanation for halfmer polysomes is a delay in joining of 60S subunits to 48S PICs at AUG start codons, such as conferred by reductions in the production or stability of 60S subunits. In fact, a tma20∆ single mutant was found to exhibit an abnormally high ratio of free 40S to free 60S subunits in the manner expected from a 60S biogenesis defect (Fleischer et al., 2006). An accumulation of unrecycled 40S subunits at stop codons or in 3’UTRs might also contribute to the halfmer formation we observed in the tma∆∆ mutant; however, the association of such 40S complexes with mRNA might be too labile to withstand sedimentation through sucrose gradients without the cross-linking step employed in 40S subunit profiling (Archer et al., 2016).

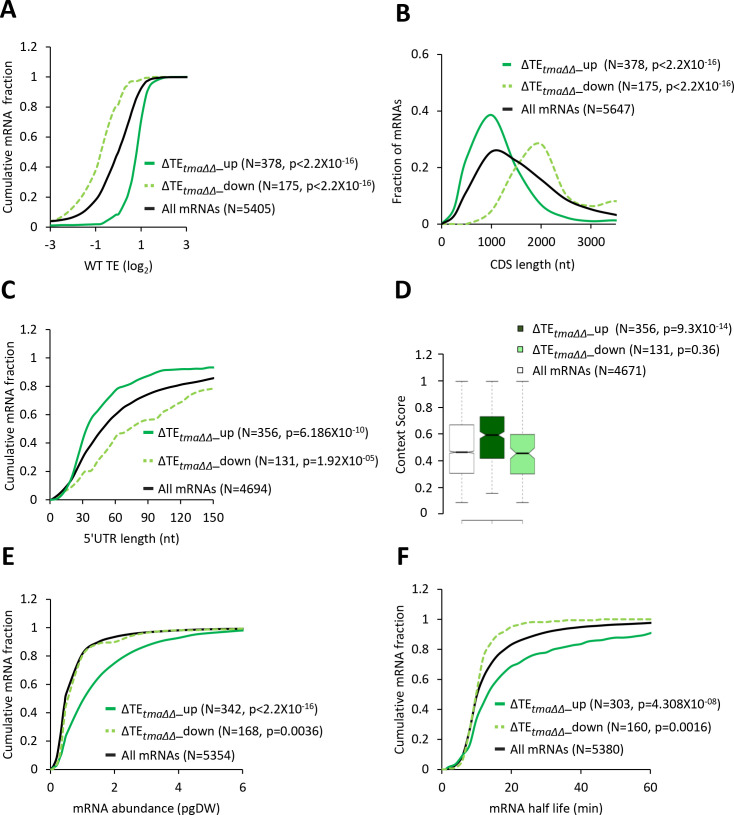

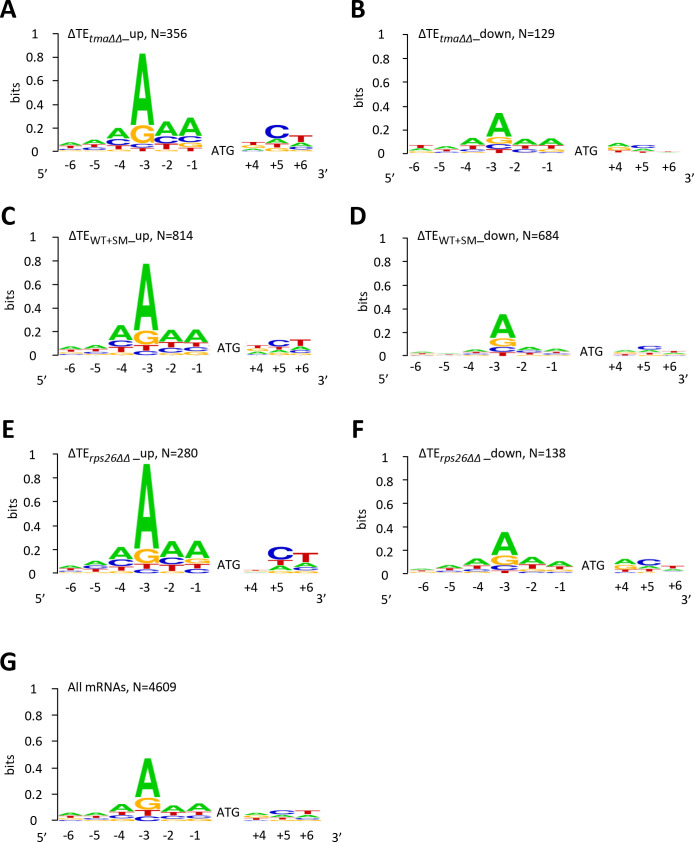

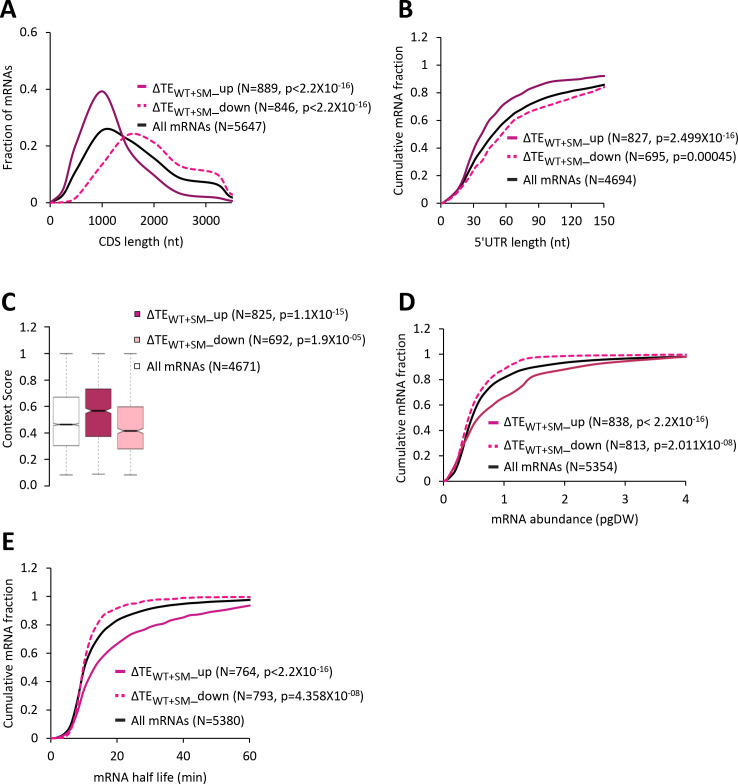

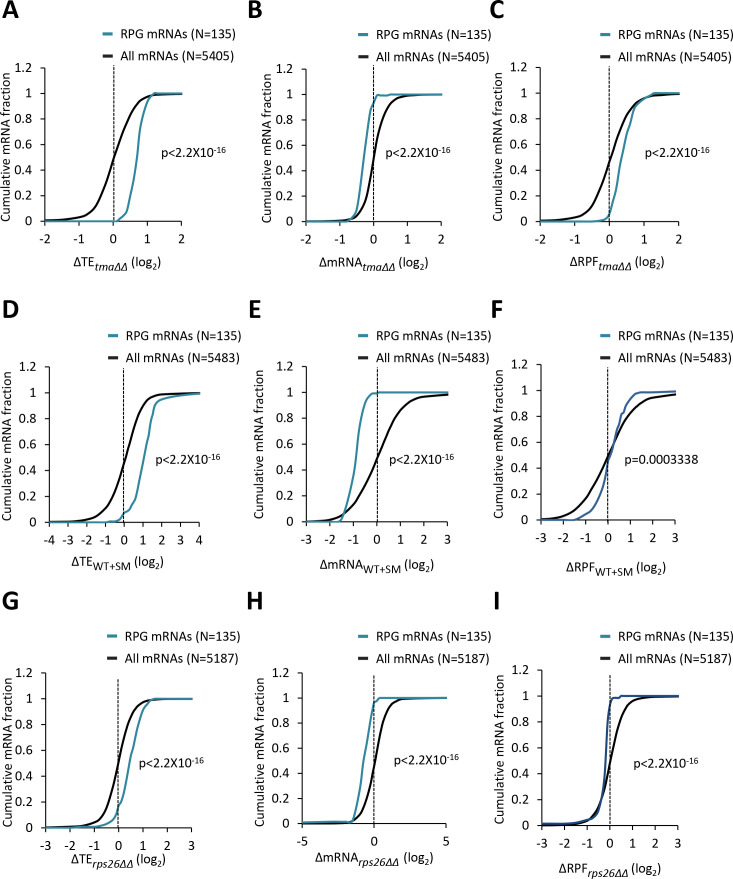

Interrogating the ribosome profiling data for possible changes in TEs of mRNAs associated with elimination of the Tma proteins, we identified a sizable group of 175 mRNAs showing significant reductions in relative TE (ΔTEtma∆∆_down), and a cohort of 378 mRNAs exhibiting relative TE increases (ΔTEtma∆∆_up), in the tma∆∆ mutant versus WT cells (at FDR < 0.05, Figure 1D). Importantly, these changes in translation were largely independent of changes in mRNA abundance, as very few mRNAs showing significant TE changes also displayed significant mRNA changes (Figure 1E), which is consistent with the idea that eIF2D or MCT-1/DENR directly or indirectly influence the translation of a fraction of cellular mRNAs. Interestingly, the mRNAs belonging to the ΔTEtma∆∆_up group tend to be highly translated in WT cells, showing a significantly higher median TE compared to all mRNAs (Figure 2A, solid green versus black). Consistent with this, these mRNAs exhibit multiple features characteristic of well-translated mRNAs, including short CDS and short 5’UTR lengths (Figure 2B–C), higher than average Kozak context scores for nucleotides surrounding the AUG start codons (Figure 2D), and greater than average transcript abundance and stability (Figure 2E–F). In sharp contrast, the group of ΔTEtma∆∆_down mRNAs tend to be poorly translated in WT cells in comparison to all mRNAs (Figure 2A, dotted versus black); and exhibit all the opposite features of the ΔTEtma∆∆_up group, which are characteristic of weakly translated mRNAs (Figure 2A–F). In accordance with these findings, sequence logos of the context nucleotides surrounding the initiation codons reveal that the ΔTEtma∆∆_up mRNAs show a higher occurrence of A nucleotides immediately upstream of the AUG codons, especially at the −3 position—a characteristic of the most highly translated mRNAs in yeast (Zur and Tuller, 2013)—in comparison to the ΔTEtma∆∆_down group (Figure 2—figure supplement 1A versus Figure 2—figure supplement 1B).

Figure 2. mRNAs with increased relative TEs in the tma∆∆ mutant exhibit multiple features of efficiently translated mRNAs.

(A, C, E, and F) Cumulative distribution function (CDF) plots of log2WT TE values (A), 5’UTR length (C), mRNA abundance in molecules per picogram of dry cellular weight (pgDW) (E), and mRNA half-life (F), for all mRNAs (black) and mRNAs exhibiting a significant increase (∆TEtma∆∆_up, solid dark green) or decrease (∆TEtma∆∆_down, dotted light green) in relative TE (at FDR < 0.05) in the tma∆∆ mutant versus WT cells. (B) Frequency distribution plots of CDS length for the groups of mRNAs examined in (A). p values in panels A-C and E-F were calculated using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. (D) Notched box plots of context scores calculated for positions −3 to −1 and +4 of main CDS AUGs for all mRNAs (white) and the ∆TEtma∆∆_up (dark green) and ∆TEtma∆∆_down (light green) mRNAs examined in (A). p values indicated in the panel were calculated using the Mann-Whitney U test. For this and all other box plots below, the upper and lower boxes contain the second and third quartiles and the band gives the median of the data. If the notches in two plots do not overlap, there is roughly 95% confidence that their medians are different.

Figure 2—figure supplement 1. mRNAs showing relative TE increases or decreases in response to the tma∆∆ mutations, increased eIF2α phosphorylation in WT, or 40S subunit depletion by rps26∆∆ tend to exhibit good or poor Kozak context surrounding their AUG start codons, respectively, compared to all mRNAs.

Figure 2—figure supplement 2. Correlations of genome-wide changes in relative TE evoked by different mutations or conditions with various mRNA attributes.

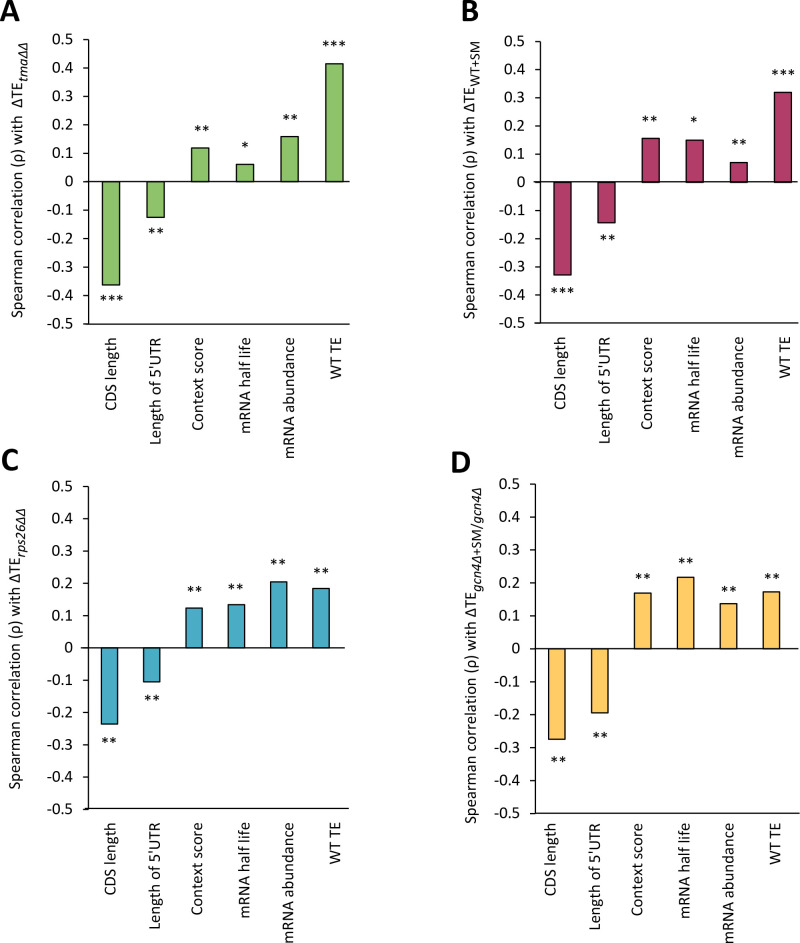

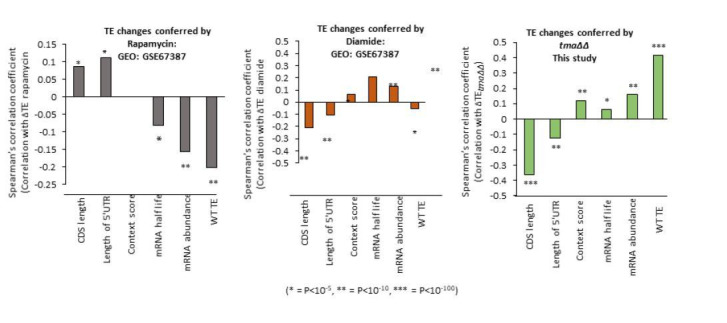

In agreement with the foregoing results obtained for the two sets of mRNAs showing TE changes that satisfy a specific FDR threshold of significance, the same trends were observed for the global TE changes measured for all expressed mRNAs in the tma∆∆ mutant versus WT cells. Thus, the ΔTEtma∆∆ values for all mRNAs show marked positive correlations with their TE values in WT cells (Figure 2—figure supplement 2A, column 6); and significant, albeit weaker, positive correlations with transcript abundance, mRNA half-life and Kozak context scores (Figure 2—figure supplement 2A, columns 3–5). A marked negative correlation with ΔTEtma∆∆ values was also observed for CDS length, and a lesser negative correlation was evident for 5’UTR length (Figure 2—figure supplement 2A, columns 1–2). Together, these findings suggest that, on deletion of the TMA64 and TMA20 genes, mRNAs that are strongly translated in WT cells tend to exhibit an increased relative TE, whereas weakly translated mRNAs tend to show a decrease in relative TE. One way to explain these results is to propose that a competition between ‘strong’ and ‘weak’ mRNAs for limiting translation components is skewed in favor of the strong mRNAs in the tma∆∆ mutant.

Evidence that relative TE changes observed in the tma∆∆ mutant do not arise from eliminating an alternative function of eIF2D

As mentioned above, studies in reconstituted mammalian systems revealed that eIF2D can promote binding of Met-tRNAi to AUG codons in specialized mRNAs in which ribosomal scanning is not required to place the AUG codon in the P site of the 40S subunit. Thus, it was conceivable that the yeast homolog of eIF2D (Tma64) promotes translation initiation on the subset of mRNAs whose TEs are reduced in the tma∆∆ mutant by complementing the function of eIF2 in delivering Met-tRNAi to the 40S subunit. The TE reductions for this group of mRNAs might then indirectly stimulate translation of the other group of mRNAs found to be upregulated in the tma∆∆ mutant owing to reduced competition for initiation machinery. In an effort to rule out this possibility, we conducted ribosome profiling of a tma64∆ single deletion mutant lacking the yeast homolog of eIF2D but still containing Tma20/Tma22, the homologs of MCT-1/DENR.

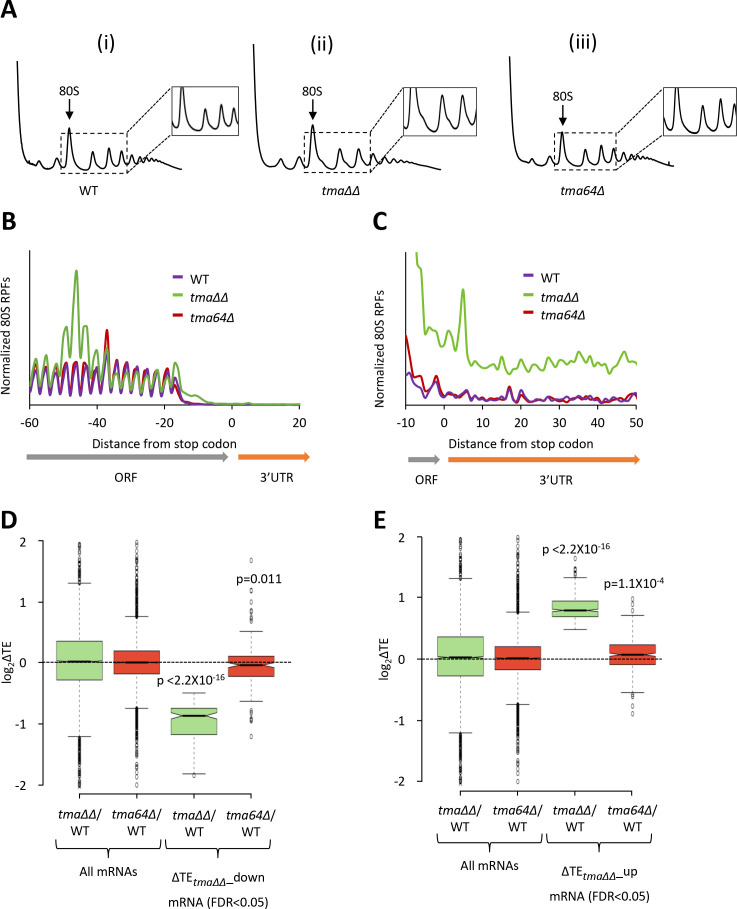

The ribosome footprint and RNA-seq results between biological replicates for the WT and tma64∆ single mutant strains were highly reproducible (Pearson’s r ≈ 0.99) (Figure 3—figure supplement 1A–D). Polysome profiles of the tma64∆ single mutant lack the halfmer polysomes observed in the tma∆∆ mutant (Figure 3A, (iii) versus (ii)), as expected if tma20∆ is responsible for halfmer formation in the double mutant. Also absent in the tma64∆ single mutant is the queuing of 80S ribosomes upstream of stop codons (Figure 3B), and the evidence of genome-wide elevated 3’UTR translation (Figure 3C), that are both evident in the tma∆∆ mutant. Thus, the tma64∆ single mutant lacks the key phenotypes associated with impaired 40S recycling observed in the tma∆∆ mutant, suggesting that either the MCT-1/DENR heterodimer is more important than eIF2D for 40S recycling, or that MCT-1/DENR and eIF2D are fully redundant for this activity in yeast. (The metagene profile for the WT strain in this experiment (Figure 3B) differs from that shown in Figure 1A in lacking an 80S peak at the stop codon. In our hands, this feature varies among independent experiments, whereas the queuing of 80S ribosomes ~ 30 nt upstream of stop codons in the tma∆∆ mutant is highly reproducible).

Figure 3. Relative TE changes in the tma∆∆ mutant do not result from elimination of eIF2D by the tma64∆ mutation.

(A) Polysome profiles of WT strain BY4741 (i), the tma∆∆ mutant H4520 (ii), and the tma64∆ mutant 4051 (iii). Cells were cultured in SC medium at 30°C to log-phase and treated with 50 μg/mL of CHX for 5 min before harvesting at 4°C. WCEs were resolved by sedimentation through sucrose gradients and scanned at 260 nm to visualize (from left to right) free 40S and 60S subunits, 80S monosomes, and polysomes. Tracings are magnified in the insets to show halfmer polysome positions in the tma∆∆ mutant (ii). (The polysome profile in (ii) was previously shown in Figure 1C (ii)). (B) Results from ribosome profiling showing the normalized 80S ribosome reads from all mRNAs aligned with respect to their stop codons for the WT (purple), the tma∆∆ mutant (green), and the tma64∆ mutant (red) described in (A). (Data for the tma∆∆ mutant was plotted previously in Figure 1A). (C) Expanded view of normalized 80S reads from all mRNAs shown in (B) for the first 50 nt of the 3’UTRs. (D–E) Notched box plots showing translation changes (log2(ΔTE)) in the indicated mutants versus WT for all mRNAs or for mRNAs exhibiting a significant decrease (∆TEtma∆∆_down, N = 175, panel D) or increase (∆TEtma∆∆_up, N = 378, panel E) in relative TE in the tma∆∆ mutant versus WT cells at a 5% FDR threshold. A few outliers were omitted from the plots to expand the y-axis scale. p values indicated in panels (D–E) were calculated using the Mann-Whitney U test for the differences between the TE changes for the indicated groups of mRNAs versus all mRNAs.

Figure 3—figure supplement 1. Reproducibility between biological replicates of ribosome footprint profiling and RNA-seq analyses for WT and the tma64∆ mutant.

Next, we interrogated the tma64∆ single mutant for changes in TE. In contrast to the tma∆∆ mutant, we found no mRNAs exhibiting significant relative TE changes in the tma64∆ single mutant versus WT cells (at FDR < 0.05, data not shown). Specifically, the group of 175 mRNAs exhibiting substantially reduced TEs in the tma∆∆ mutant (ΔTEtma∆∆_down, defined in Figure 1D) showed a relatively slight, albeit significant, decrease in median TE in the tma64∆ single mutant versus WT (Figure 3D column 4), indicating that elimination of yeast eIF2D alone has only a small impact on the translation of these mRNAs. Likewise, the TE increases for the 378 mRNAs in the ΔTEtma∆∆_up group were relatively small in the tma64∆ single mutant versus the tma∆∆ mutant (Figure 3E, column 4 versus 3). These findings are at odds with the possibility that elimination of eIF2D, and its possible role as an alternative to eIF2 for recruitment of Met-tRNAi, is responsible for the widespread TE changes observed in the tma∆∆ mutant. However, we cannot eliminate the possibility that eIF2D and the MCT-1/DENR heterodimer are completely interchangeable for eIF2-independent Met-tRNAi recruitment in vivo such that MCT-1/DENR is sufficient to provide a WT level of this non-canonical pathway in cells devoid of eIF2D. The correlation between recycling defects and marked TE changes observed on comparing the tma∆∆ and tma64∆ mutants is consistent with the model that the defect in 40S ribosome recycling conferred by the tma∆∆ mutations contributes to the reprogramming of TEs observed in this double mutant.

Reducing TC abundance by eIF2α phosphorylation and elimination of 40S recycling factors confers related reprogramming of relative TEs

Given the role of eIF2D and/or MCT-1/DENR in 40S recycling, we hypothesized that sequestering of 40S subunits in post-TerCs and in ribosomes engaged in aberrant 3’UTR scanning or translation in the tma∆∆ mutant would reduce the availability of free 40S subunits for assembling 43S PICs; which would contribute to a skewing of TEs to disproportionately favor strong over weak mRNAs. If this hypothesis is correct, then reducing assembly of 43S PICs by other means might elicit a similar global reprogramming of translation. As a first test of this prediction, we used ribosome profiling to examine the effects on genome-wide TEs rendered by phosphorylation of serine-51 of eIF2α by protein kinase Gcn2. This phosphorylation event is induced by various stresses and is known to reduce assembly of the eIF2·GTP·Met-tRNAi TC in yeast cells (Hinnebusch, 2005). Gcn2 can be activated by limiting biosynthesis of isoleucine and valine by treatment with sulfometuron methyl (SM), an inhibitor of the branched chain amino acid biosynthetic enzyme encoded by ILV2 (Jia et al., 2000).

Judging by the change in polysome:monosome ratio, inducing eIF2α phosphorylation by SM treatment of WT cells confers a reduction in bulk translation initiation similar to that given by the tma∆∆ mutations, but without the appearance of halfmer polysomes seen in untreated tma∆∆ cells (Figure 1C and Figure 1—figure supplement 2, (iii) versus (ii) and (i)). These same growth conditions were used to conduct ribosome profiling of WT treated with SM and compared to the results described above from isogenic untreated WT cells. The ribosome profiling and RNA-seq results between biological replicates of the SM-treated WT cells were highly reproducible (Pearson’s r ≈ 0.99) (Figure 1—figure supplement 1E–F). In addition to reduced bulk translation, a second well-known response to the reduction in TC assembly evoked by eIF2α phosphorylation is induction of GCN4 mRNA translation, owing to the specialized ‘delayed reinitiation’ mechanism imposed by the four upstream open-reading frames in this transcript (Hinnebusch, 2005). Ribosome profiling revealed the expected strong induction of GCN4 translation evoked by SM treatment of WT cells, as revealed by a large increase in RPF reads in the GCN4 coding sequence (CDS) with little or no change in GCN4 mRNA reads, yielding an increase in TE (ΔTE) of ~30-fold (Figure 4A, WT+SM versus WT, cf. replicate cultures a and b for Ribo-seq and RNA-seq data). In contrast, no significant increase in GCN4 translation was observed in the untreated tma∆∆ mutant (Figure 4A, the tma∆∆ mutant versus WT), indicating normal levels of TC assembly in this mutant. Furthermore, SM-treated WT cells did not exhibit the queuing of 80S ribosomes upstream of stop codons and elevated 80S occupancies in 3’UTRs observed in the tma∆∆ mutant (Figure 1A–B, maroon versus blue), indicating that increased eIF2α phosphorylation does not impair 40S recycling.

Figure 4. Relative TE changes evoked by increased eIF2α phosphorylation overlap substantially with those conferred by deletion of TMA64/TMA20.

(A) Genome browser view of ribosome profiling data for GCN4 mRNA, showing RPF reads (Ribo) and mRNA reads (RNA) mapping across the transcription unit in WT, with or without SM treatment, and in the tma∆∆ mutant, showing two replicates (a and b) for each genotype/condition. The main CDS is shown schematically (orange). The calculated ∆TEWT+SM and ∆TEtma∆∆ values are shown. (B) Volcano plot showing log2 ratios of relative TEs in SM-treated versus untreated WT cells (∆TEWT+SM values) for each mRNA (x-axis) versus negative log10 of the FDR for the ∆TEWT+SM changes determined by DESeq2 analysis of the 5483 mRNAs with evidence of translation (y-axis). The dotted line marks the 5% FDR threshold. mRNAs showing a significant increase (∆TEWT+SM_up) or decrease (∆TEWT+SM_down) in relative TE in SM-treated versus untreated WT cells, at FDR < 0.05, are plotted in dark or light pink circles, respectively. (C) Venn diagrams of overlaps between differentially expressed mRNAs (ΔmRNA) (FDR < 0.05 and log2ΔmRNA >1 or <-1) or differentially translated mRNAs (ΔTE, FDR < 0.05) in SM-treated versus untreated WT cells, with arrows indicating increased (up) or decreased (down) mRNA or TE in SM-treated versus untreated WT cells. p values were calculated using the Fisher’s exact test and were shown only for over-enrichment compared to expectation by chance. (D) Cumulative distribution function (CDF) plots of log2WT TE values for all mRNAs (black) and mRNAs exhibiting a significant increase (∆TEWT+SM_up, solid dark pink) or decrease (∆TEWT+SM_down, dotted light pink) in relative TE (at FDR < 0.05) in SM-treated versus untreated WT cells. p values were calculated using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. (E) Hierarchical clustering analysis of log2TE changes observed for 486 mRNAs that exhibit significant TE changes in the tma∆∆ mutant versus WT cells, and also in SM-treated versus untreated WT cells, at FDR < 0.1 for both comparisons. The color scale for log2ΔTE values ranges from 2.5 (dark blue) to −3.5 (dark red). One mRNA (YPR146C) with ∆TEtma∆∆ >10 fold and ∆TEWT+SM <10 fold was excluded to enhance the color differences among the remaining mRNAs analyzed in the heatmap. (F) Venn diagrams of overlaps between the groups of mRNAs defined in Figure 1D and B showing significantly increased or decreased TEs conferred by SM treatment of WT cells or by the tma∆∆ mutations. p values were calculated using the Fisher's exact test. (G) Notched box plots showing the log2WT TEs of the group of 135 RPG mRNAs or all expressed mRNAs. A few outliers were omitted from the plots to expand the y-axis scale. The p value was calculated using the Mann-Whitney U test.

Figure 4—figure supplement 1. Increased eIF2α phosphorylation in WT upregulates the relative TEs of mRNAs with attributes similar to mRNAs exhibiting relative TE increases in response to the tma∆∆ mutations.

Figure 4—figure supplement 2. Relative TE changes evoked by increased eIF2α phosphorylation in WT are broadly similar to those conferred by the tma∆∆ mutations.

Figure 4—figure supplement 3. Gene ontology (GO) analysis of relative TE changes evoked by the tma∆∆ mutations, increased eIF2α phosphorylation in WT, or the rps26∆∆ mutations.

Figure 4—figure supplement 4. Ribosomal protein mRNAs are translationally upregulated by the tma∆∆ mutations, increased eIF2α phosphorylation in WT, or the rps26∆∆ mutations.

Figure 4—figure supplement 5. Reproducibility between biological replicates of ribosome footprint profiling and RNA-seq analyses for the gcn4∆ mutant cultured with or without SM treatment.

Figure 4—figure supplement 6. Condition-specific changes in relative TE evoked by the tma∆∆ mutations, increased eIF2α phosphorylation in WT, or the rps26∆∆ mutations.

Interrogating the ribosome profiling data for changes in TE of specific mRNAs in SM-treated WT versus untreated WT cells (ΔTEWT+SM) uncovered 889 and 846 mRNAs whose TEs were relatively upregulated (ΔTEWT+SM_up) or relatively down-regulated (ΔTEWT+SM_down), respectively, under these conditions (FDR < 0.05, Figure 4B). The TE changes evoked by SM treatment were largely independent of changes in mRNA abundance (Figure 4C), except that ~ 1/4th of the 889 mRNAs exhibiting increased TEs also show decreased mRNA abundance (Figure 4C, 2nd row; more on this phenomenon below). This last finding, plus the considerably larger number of mRNAs whose TEs were significantly changed by SM treatment versus the tma∆∆ mutations, indicate a more widespread reprogramming of TEs evoked by increased eIF2α phosphorylation compared to loss of 40S recycling factors. Nevertheless, as observed for the tma∆∆ mutations, the mRNAs showing increased relative TE on SM treatment (ΔTEWT+SM_up) are enriched for mRNAs that are well-translated in untreated WT cells, whereas the ΔTEWT+SM_down group of mRNAs are enriched for weakly translated mRNAs (Figure 4D). Moreover, the ΔTEWT+SM_up group tend to exhibit all of the attributes of strongly translated mRNAs (short CDS and 5’UTR lengths, good Kozak context, greater mRNA abundance and stability, compared to the genome averages); whereas the ΔTEWT+SM_down mRNAs are enriched for the features of weakly translated mRNAs (Figure 4—figure supplement 1A–E). These opposite features for the ΔTEWT+SM_up and ΔTEWT+SM_down groups of mRNAs are mirrored by the greater preferences for A nucleotides upstream of the AUG codons of the ΔTEWT+SM_up group in comparison to the ΔTEWT+SM _down group (Figure 2—figure supplement 1C versus Figure 2—figure supplement 1D). Furthermore, the global ΔTE values for all expressed mRNAs on SM treatment of WT cells (ΔTEWT+SM) are positively correlated with mRNA half-life, transcript abundance, Kozak context score, and the TE in WT cells, while negatively correlated with 5’UTR and CDS lengths (Figure 2—figure supplement 2B). As in the case of TE changes in response to the tma∆∆ mutations, the strongest correlations with TE changes in response to SM are for CDS length and for TE in WT cells (Figure 2—figure supplement 2B versus Figure 2—figure supplement 2A).

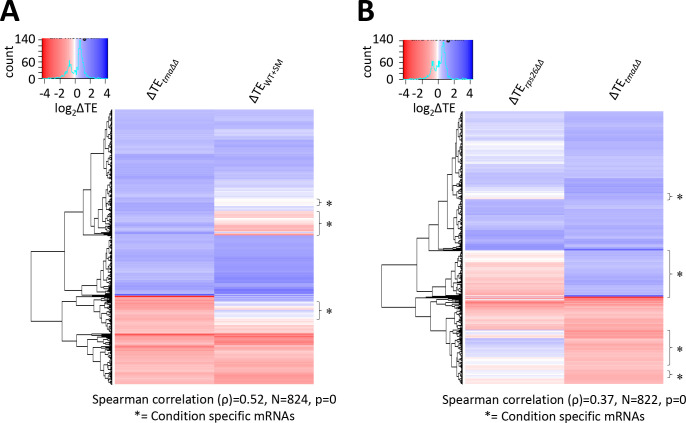

Additional support for the idea that eliminating the Tma proteins and increasing phosphorylation of eIF2α produce overlapping alterations in TEs was provided by hierarchical clustering of the TE changes in the two conditions for the group of 486 mRNAs showing significant TE changes, either relative increases or decreases, in response to both the tma∆∆ mutations and SM treatment of WT cells. The results are displayed in the heatmap of Figure 4E, where TE increases or decreases for each gene (shown from top to bottom) are indicated by blue or red hues, respectively. It can be seen that the majority of mRNAs showing significant TE changes in response to the tma∆∆ mutations or SM treatment of WT cells exhibit changes in the same direction (same color) in the two conditions (Figure 4E); albeit with a tendency for stronger changes (deeper hues) in the SM-treated WT cells. In accordance with these findings, we found highly significant overlaps between the mRNAs in the ΔTEtma∆∆_up and ΔTEWT+SM_up groups, and between the ΔTEtma∆∆_down and ΔTEWT+SM_down groups of mRNAs defined above (with changes in TE at FDR < 0.05) on elimination of the Tma proteins or SM treatment of WT cells (Figure 4F). Moreover, the median TEs of the groups of mRNAs that are translationally up- or down-regulated by the tma∆∆ mutations also show significant changes in median TE in the same direction, albeit of diminished magnitude, on SM treatment of WT cells (Figure 4—figure supplement 2A–B, columns 3–4). A similar conclusion emerges from comparing the changes in median TE between the two conditions for the groups of mRNAs up- or down-regulated by SM treatment of WT cells (Figure 4—figure supplement 2C–D, columns 3–4).

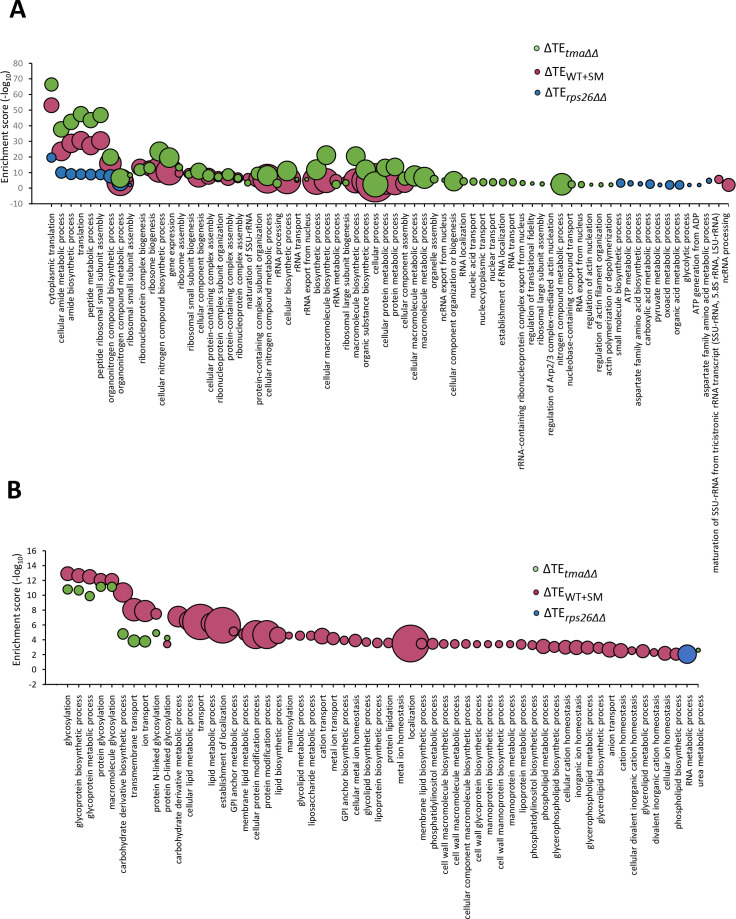

Further evidence that the TEs of many mRNAs change coherently on eliminating the Tma proteins or SM treatment of WT came from gene ontology (GO) analysis of the ΔTEtma∆∆_up and ΔTEWT+SM_up groups of mRNAs. This exercise revealed that the most significantly enriched functional groups for both sets of upregulated mRNAs are gene products involved in cytoplasmic translation, including ribosome biogenesis (Figure 4—figure supplement 3A, cf. maroon and green circles). Indeed, the group of 135 ribosomal protein gene (RPG) mRNAs shows highly significant TE increases in both conditions compared to all mRNAs (Figure 4—figure supplement 4A and D). At the same time, the abundance of this group of mRNAs declines under both conditions (Figure 4—figure supplement 4B and E), which partially offsets the increases in TEs and dampens the increase in translation levels (i.e. RPF reads uncorrected for mRNA abundance, Figure 4—figure supplement 4C and F). The repression of RPG mRNAs in response to starvation for individual amino acids has been described previously (Natarajan et al., 2001; Saint et al., 2014). The findings above, that the TEs of the RPG mRNAs are upregulated by both the tma∆∆ mutations and SM treatment of WT cells (Figure 4—figure supplement 4A and D), are in accordance with the fact that they comprise a group of particularly ‘strong’ mRNAs, exhibiting TEs in WT substantially above the genome average (Figure 4G). GO analysis of the ΔTEtma∆∆_down and ΔTEWT+SM_down groups of mRNAs also revealed common functional categories among those exhibiting the highest enrichments, including protein glycosylation, mannoprotein biosynthesis, and transmembrane transport (Figure 4—figure supplement 3B, cf. maroon and green circles).

Given that increased eIF2α phosphorylated induced by SM treatment increases translation of GCN4 mRNA and alters expression of hundreds of mRNAs owing to enhanced transcriptional activation by Gcn4 (Jia et al., 2000; Natarajan et al., 2001), the question arose as to whether the transcriptional changes evoked by Gcn4 induction are responsible for the translational reprogramming produced by SM treatment of WT cells. To test this, we conducted ribosome profiling of a gcn4∆ mutant treated with SM under the same conditions employed above for WT cells. The ribosome profiling and RNA-seq results between biological replicates for the gcn4∆ mutant cultured with or without SM treatment were highly reproducible (Pearson’s r ≈ 0.99) (Figure 4—figure supplement 5A–D). This experiment probably does not provide a perfect test of whether upregulating Gcn4 contributes to the translational reprogramming evoked by SM treatment because the absence of transcriptional changes produced Gcn4 renders the gcn4∆ mutant more sensitive to the growth-retarding effects of Ile/Val starvation by SM. Nevertheless, analyzing the TE changes produced by SM treatment of the gcn4∆ mutant revealed a strong reprogramming of TEs with features similar to those described above for SM-treated WT cells and untreated tma∆∆ mutant. In particular, the ΔTE values for all expressed mRNAs on SM treatment of the gcn4∆ mutant show significant positive correlations with TE in WT, transcript abundance, mRNA half-life and Kozak context score, but negative correlations with CDS and 5’UTR lengths (Figure 2—figure supplement 2D).

It is striking that eliminating Tma proteins and SM treatment both preferentially increase the TEs of strong mRNAs and disfavor weak mRNAs, and that the majority of mRNAs whose TEs are significantly altered under both of these conditions display changes in the same direction and are enriched for the same functional categories. However, there are also many condition-specific changes in TE that should not be overlooked. Thus, ~50% of the mRNAs whose TEs are upregulated or down-regulated by the tma∆∆ mutations are not significantly altered by SM treatment of WT cells (Figure 4F), even though the latter condition generally has a greater impact on the TEs of those mRNAs significantly affected by both conditions (Figure 4E). Condition-specific TE changes are also evident in a cluster analysis of TE changes conferred by the two conditions for all 824 mRNAs exhibiting significant TE changes in response to the tma∆∆ mutations (at FDR < 0.1; Figure 4—figure supplement 6A). While the TE changes conferred by the tma∆∆ mutations or SM treatment of WT cells are significantly correlated for this group of mRNAs (Spearman’s ρ = 0.52, p = 0), there are sizeable blocks of mRNAs that show changes of lesser magnitude (same color, lighter hue), or even changes in the opposite direction (different colors), on SM treatment versus the tma∆∆ mutations (see blocks of mRNAs bracketed in Figure 4—figure supplement 6A). Thus, numerous condition-specific changes in TE appear to be superimposed on the shared general trends of increased TEs for strong mRNAs and decreased TEs for weak mRNAs conferred by the tma∆∆ mutations or by SM treatment of WT.

Relative TE changes evoked by depleting 40S subunits are also related to those conferred by loss of 40S recycling factors and reduced TC assembly

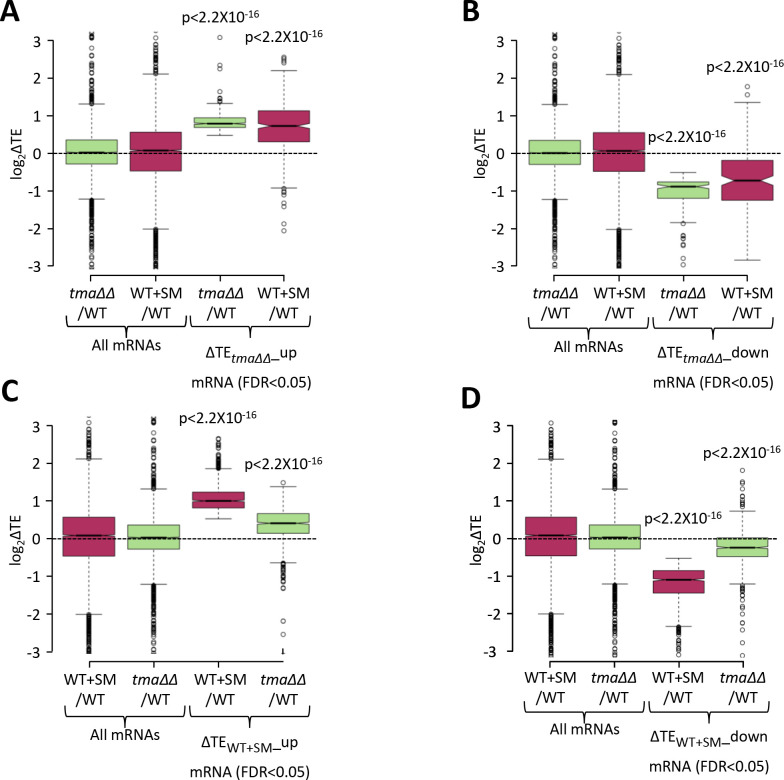

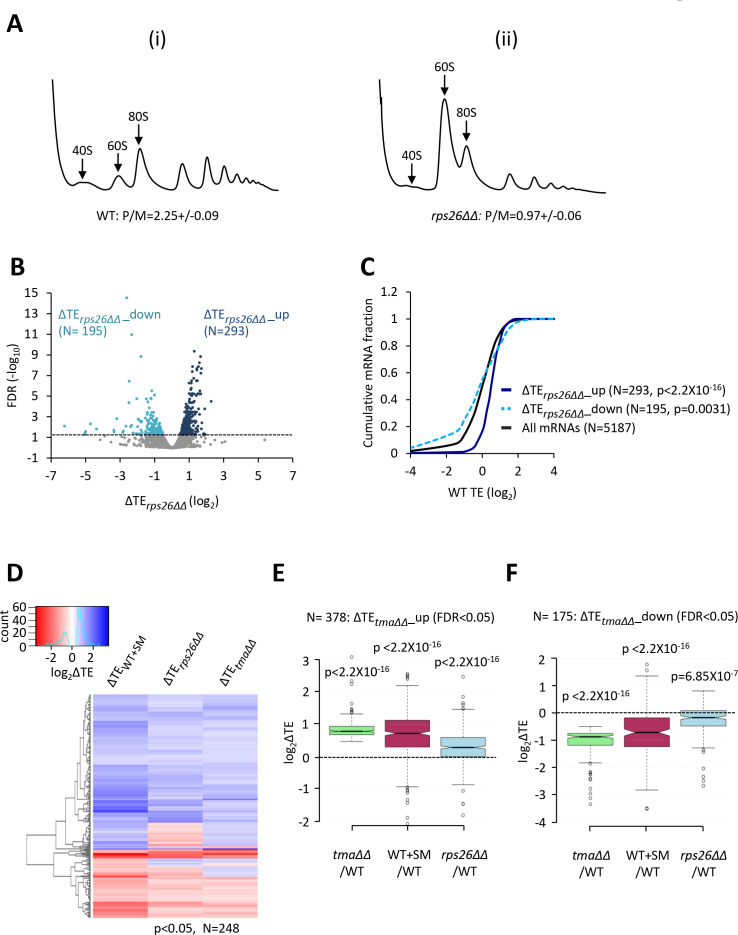

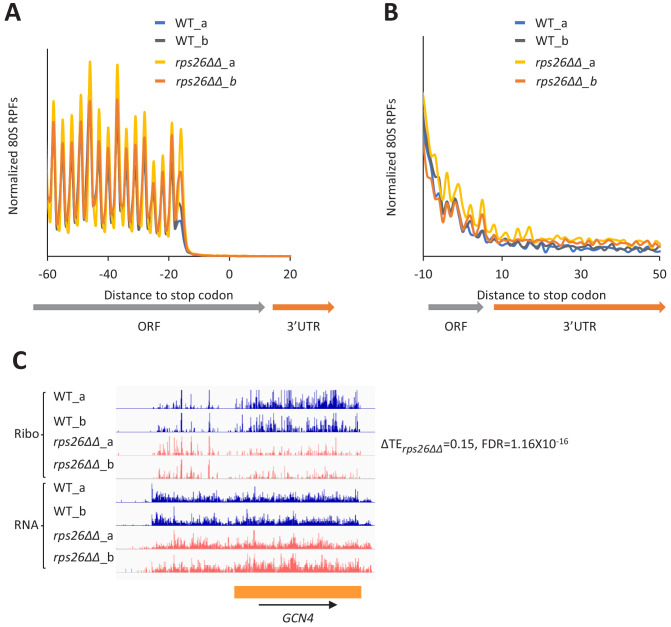

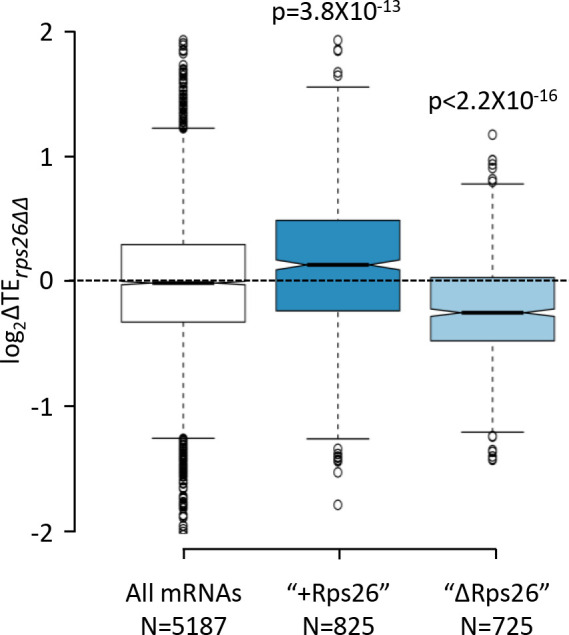

The results thus far suggest that the competition between strong and weak mRNAs is shifted in favor of strong mRNAs when eIF2D and MCT-1/DENR are both eliminated or when eIF2 function is impaired by phosphorylation. Given the role of eIF2D and/or MCT-1/DENR in supplying recycled free 40S subunits for initiation, and the effect of eIF2α phosphorylation in reducing the concentration of TC—a key constituent of initiation complexes—we considered the possibility that both conditions skew the competition among different mRNAs by limiting formation of 43S PICs. If so, then reducing the availability of free 40S subunits by reducing total 40S abundance should likewise diminish 43S PIC assembly and confer a similar reprogramming of TEs. To test this prediction, we depleted the 40S protein Rps26A from a strain lacking the paralog Rps26B by employing a rps26b∆ mutant in which RPS26A is transcribed from the galactose-dependent, glucose-repressible PGAL1 promoter (for brevity, dubbed rps26∆∆). Polysome profile analysis revealed a marked increase in the ratio of free 60S to 40S subunits 3 hr after shifting the rps26∆∆ mutant to glucose medium, compared to the WT strain cultured in parallel (Figure 5A), which is diagnostic of a reduction in 40S subunit levels in the mutant. Consistent with this, there was also a reduction in the polysome:monosome ratio in the rps26∆∆ mutant, indicating a reduced rate of translation initiation (Figure 5A). Thus, these same growth conditions were used to conduct ribosome profiling of the rps26∆∆ mutant and isogenic WT strain.

Figure 5. Relative TE changes evoked by depleting 40S subunits are broadly comparable to those evoked by the tma∆∆ mutations or by increased eIF2α phosphorylation.

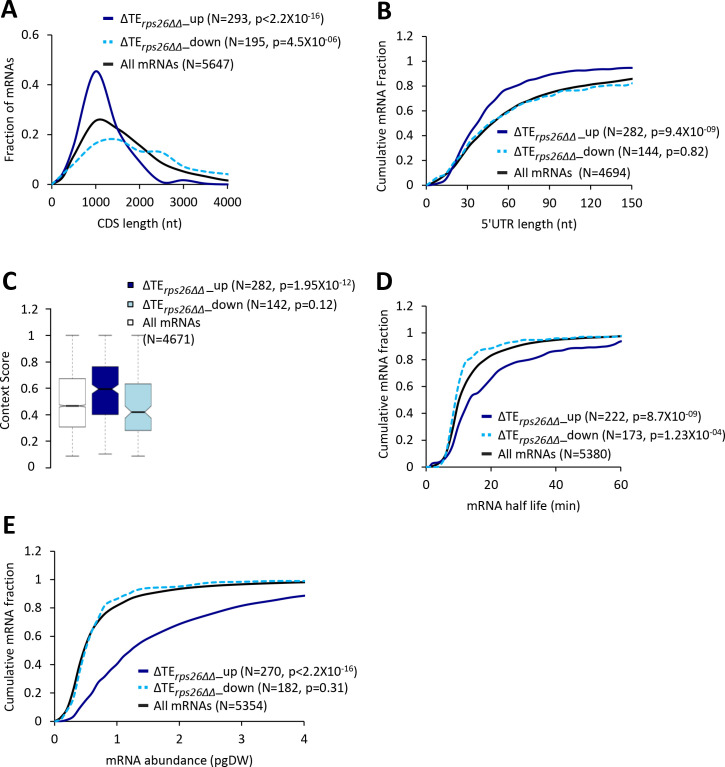

(A) Polysome profiles of WT strain H2994 and the rps26∆∆ mutant JVY09. Cells cultured in SC medium with 2% galactose and 2% raffinose instead of glucose at 30°C to log-phase were shifted to glucose-containing SC medium for 3 hr and treated with 50 μg/mL of CHX for 5 min before harvesting at 4°C. WCEs were resolved by sedimentation through sucrose gradients and scanned at 260 nm to visualize (from left to right) free 40S and 60S subunits, 80S monosomes, and polysomes. The mean polysome/monosome (P/M) ratios ± SEMs from five biological replicates are shown. (B) Volcano plot showing the log2 ratios of relative TEs in the rps26∆∆ mutant versus WT cells (∆TErps26∆∆ values) for each mRNA (x-axis) versus negative log10 of the FDR for the ∆TErps26∆∆ changes determined by DESeq2 analysis of ribosome profiling data for the 5187 mRNAs with evidence of translation (y-axis). The dotted line marks the 5% FDR threshold. mRNAs showing a significant increase (∆TErps26∆∆_up) or decrease (∆TErps26∆∆_down) in relative TE in the rps26∆∆ mutant versus WT cells at FDR < 0.05, are plotted in dark or light blue circles, respectively. (C) Cumulative distribution function (CDF) plots of log2WT TE values for all mRNAs (black) and mRNAs exhibiting a significant increase (∆TErps26∆∆_up, solid dark blue) or decrease (∆TErps26∆∆_down, dotted light blue) in relative TE (at FDR < 0.05) in the rps26∆∆ mutant versus WT cells. p values were calculated using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. (D) Hierarchical clustering analysis of log2TE changes observed for 248 mRNAs that exhibit significant TE changes in the tma∆∆ mutant versus WT cells, in SM-treated versus untreated WT cells, and also in the rps26∆∆ mutant versus WT cells, at p < 0.05 for all genotypes/conditions. The color scale for log2ΔTE values ranges from 3.5 (dark blue) to −2.5 (dark red). (E–F) Notched box plots showing translation changes (log2ΔTE) in the indicated mutant versus WT for mRNAs exhibiting a significant increase (∆TEtma∆∆_up, N = 385, panel E) or decrease (∆TEtma∆∆_down, N = 175, panel F) in relative TE in the tma∆∆ mutant versus WT cells at a 5% FDR threshold. A few outliers were omitted from the plots to expand the y-axis scale. p values were calculated using the Mann-Whitney U test for the differences between the indicated groups of mRNAs versus all mRNAs. (Columns 1–2 in panels (E–F) were previously compared in Figure 4—figure supplement 2A–B).

Figure 5—figure supplement 1. Reproducibility between biological replicates of ribosome footprint profiling and RNA-seq analyses for WT and the rps26∆∆ mutant.

Figure 5—figure supplement 2. The rps26∆∆ mutations do not derepress GCN4 mRNA translation or confer 40S recycling defects.

Figure 5—figure supplement 3. 40S subunit depletion in the rps26∆∆ mutant increases the relative TEs of mRNAs with attributes similar to mRNAs showing TE increases conferred by the tma∆∆ mutations.

Figure 5—figure supplement 4. Effects of the rps26∆∆ mutations on the relative TEs of the "+Rps26" and "ΔRps26" groups of mRNAs.

Figure 5—figure supplement 5. Effects of rps29b∆ and rps0b∆ mutations on relative TEs of different groups of mRNAs calculated from the ribosome footprint profiling and RNA-seq data of Cheng et al., 2019.

The ribosome footprint and RNA-seq results between biological replicates for each strain were highly reproducible (Pearson’s r ≈ 0.99) (Figure 5—figure supplement 1A–D). Metagene analysis of the ribosome profiling data did not reveal queuing of 80S subunits near stop codons, nor evidence of elevated 3’UTR translation in the rps26∆∆ mutant (Figure 5—figure supplement 2A–B). Nor did we observe derepression of GCN4 translation in the rps26∆∆ mutant versus WT cells; rather, the TE of GCN4 mRNA was significantly reduced (Figure 5—figure supplement 2C), which will be discussed below. Thus, depletion of Rps26 and the attendant reduction in 40S subunit levels should not alter TEs by impairing 40S recycling or reducing TC abundance.

We found that depleting free 40S subunits in the rps26∆∆ mutant upregulates (ΔTErps26∆∆_up) and downregulates (ΔTErps26∆∆_down) the relative TEs of 293 and 195 mRNAs, respectively, when compared to WT cells (FDR < 0.05; Figure 5B). Supporting our prediction, the attributes of the ΔTErps26∆∆_up mRNAs were very similar to those translationally stimulated by the tma∆∆ mutations or by eIF2α phosphorylation in SM-treated WT cells: they exhibit greater than average TEs in WT cells (Figure 5C, dark blue versus black), Kozak context scores, mRNA half-lives, and mRNA abundance, and shorter than average CDS and 5’UTR lengths (Figure 5—figure supplement 3A–E). The translationally repressed group of mRNAs, ΔTErps26∆∆_down, showed the opposite trends for at least a subset of these attributes, including lower than average TEs in WT (Figure 5C), larger than average CDS lengths (Figure 5—figure supplement 3A), and shorter mRNA half-lives (Figure 5—figure supplement 3D). In addition, the group of ΔTErps26∆∆_up mRNAs show greater enrichment for A nucleotides 5’ of the AUG start codons compared to the ΔTErps26∆∆_down group, and to all mRNAs (Figure 2—figure supplement 1E–G). Examination of the correlations between these mRNA attributes and the global ΔTE changes conferred by the rps26∆∆ mutations for all expressed mRNAs again revealed significant positive correlations with TE in WT, and with transcript abundance, mRNA half-life and Kozak context score, but negative correlations with CDS and 5’UTR lengths (Figure 2—figure supplement 2C).

The foregoing results suggest that the TE changes conferred by elimination of Rps26 might overlap substantially with those conferred by elimination of the Tma proteins or by induction of eIF2α phosphorylation by SM treatment of WT cells. Support for this idea is provided by hierarchical clustering of the TE changes for a group of 248 mRNAs showing TE changes in response to all three conditions of the tma∆∆ mutations, SM treatment of WT cells, or depletion of Rps26 in the rps26∆∆ mutant (at p < 0.05), where it can be seen that the majority of these mRNAs show TE changes in the same direction for all three conditions (Figure 5D). Furthermore, the group of mRNAs whose TEs were upregulated in the tma∆∆ mutant versus WT (ΔTEtma∆∆_up), and which also showed an increase in median TE in SM-treated versus untreated WT cells (Figure 5E, columns 1–2), likewise displayed an increased median TE in the rps26∆∆ mutant versus WT (Figure 5E, column 3). Similar results were observed for the group of mRNAs whose TEs were down-regulated in the tma∆∆ mutant versus WT (ΔTEtma∆∆_down), which also showed significant TE reductions in response to both SM treatment of WT cells and the depletion of Rps26 in the rps26∆∆ mutant (Figure 5F, columns 1–3). In addition, the mRNAs whose TEs are upregulated by the rps26∆∆ mutations are enriched for the GO categories of ribosomal components and ribosome biogenesis, just as observed for the responses to the tma∆∆ mutations and SM treatment (Figure 4—figure supplement 3A, blue versus green/maroon). Consistent with this, the group of 135 RPG mRNAs shows highly significant TE increases in the rps26∆∆ mutant compared to all mRNAs (Figure 4—figure supplement 4G). Also, in accordance with the aforementioned results on the tma∆∆ mutant and SM-treated WT, the abundance of the RPG mRNAs declines in response to depletion of Rps26 (Figure 4—figure supplement 4H), offsetting the increases in TEs and dampening the increase in translation levels (Figure 4—figure supplement 4I).

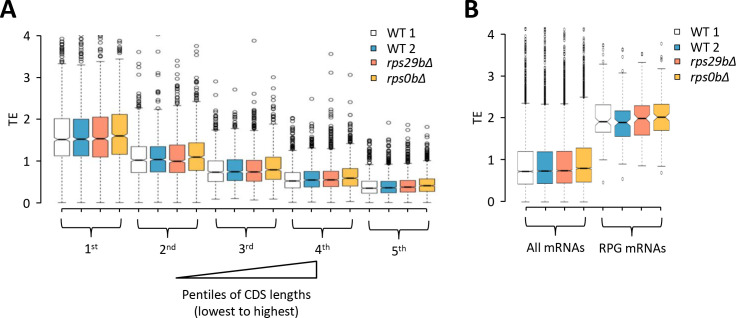

Despite these commonalities in TE changes, there are sizeable groups of mRNAs whose TEs are affected differently by the rps26∆∆ and tma∆∆ mutations. This is indicated by the relatively smaller changes in median TE conferred by the rps26∆∆ mutations versus the tma∆∆ mutations or SM treatment for the groups of mRNAs whose TEs are up- or down-regulated by the tma∆∆ mutations (Figure 5E–F, column 3 versus 1). It is also evident in the cluster analysis of the TE changes conferred by the rps26∆∆ or tma∆∆ mutations for the group of mRNAs showing significant TE changes in response to the tma∆∆ mutations. Although the TE changes for this group of mRNAs are significantly correlated between the rps26∆∆ and tma∆∆ mutations (ρ = 0.37, p = 0), there are several sets of mRNAs that change by markedly different amounts or in opposite directions in the two mutants (Figure 4—figure supplement 6B, see bracketed blocks). Moreover, the ΔTErps26∆∆_down mRNAs do not show significant enrichment for the GO categories shared by the mRNAs whose TEs are down-regulated by the tma∆∆ mutations and SM treatment (Figure 4—figure supplement 3B). Thus, as concluded above for the TE changes conferred by SM treatment, there are many TE changes specific to the depletion of Rps26 that appear to be superimposed on the tendency common to all three conditions for strong mRNAs to show increased TEs and weak mRNAs to show reduced TEs; and these differences are generally more pronounced for the rps26∆∆ mutations compared to the tma∆∆ mutations or SM treatment of WT. Below, we consider various explanations for the condition-specific changes in TE, and also explain that the shared trend is in accordance with mathematical modeling of how TEs of different groups of mRNAs should be altered by limiting concentrations of 43S PICs.

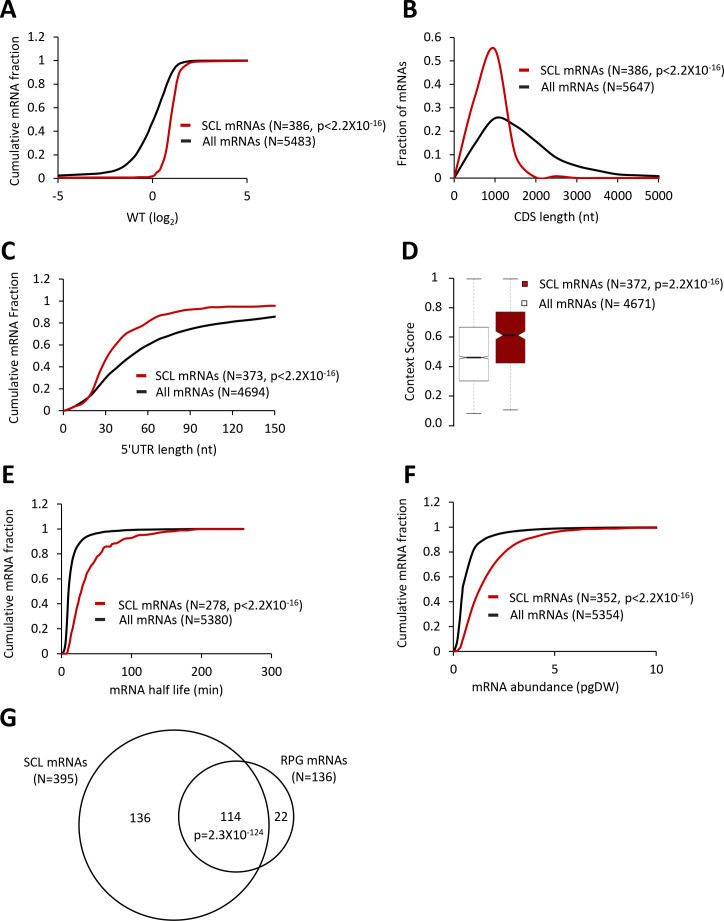

The group of mRNAs with a strong propensity to form the closed-loop intermediate is translationally upregulated by loss of 40S recycling factors, increased eIF2α phosphorylation or 40S subunit depletion

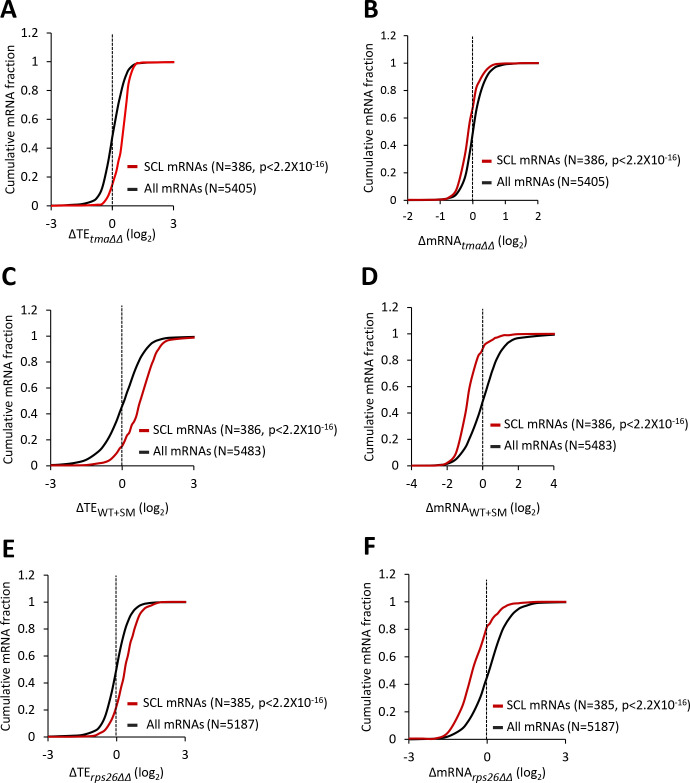

The 5’ cap of mRNA is recognized by the cap-binding complex eIF4F, and interaction of the scaffolding subunit eIF4G with the poly(A) binding protein (PABP) enables mRNA circularization. There is evidence that formation of this ‘closed-loop’ intermediate stabilizes eIF4F binding at the cap (Park et al., 2011), and facilitates recycling of 40S subunits from the stop codon to the mRNA 5’ end, to increase initiation frequencies (Uchida et al., 2002). Using RNA sequencing-immunoprecipitation (RIP-seq) analysis of eIF4F subunits, PABP and the inhibitory eIF4E-binding proteins (4EBPs), Costello et al. identified ‘Strong Closed-Loop’ (SCL) mRNAs as those enriched in occupancies of eIF4E, eIF4G, and PABP, while de-enriched for association with 4EBPs (Costello et al., 2015). This group of SCL mRNAs have shorter than average 5’UTRs and CDS lengths, higher than average Kozak context scores for nucleotides surrounding the AUG start codons, are more abundant, and more stable compared to all mRNAs, and are highly translated in WT cells (Figure 6—figure supplement 1A–F). Noting that these attributes are enriched among the mRNAs whose TEs are elevated by elimination of the Tma proteins, eIF2α phosphorylation, or depletion of Rps26 and 40S subunits, we interrogated the TE changes for the group of SCL mRNAs conferred by each of these three conditions. As shown in Figures 6A, C and E, the TEs of the group of SCL mRNAs are significantly elevated in each of the three conditions, whereas the abundance of these mRNAs is significantly reduced under the same conditions (Figures 6B, D and F). The inference that limiting 43S PICs upregulates the TEs of SCL mRNAs is also supported by data from Thompson et al., who reported a similar upregulation of SCL mRNAs in strains lacking a ribosomal protein, including rpp1a∆ and rps16b∆ mutants (Thompson et al., 2016). Thus, the SCL mRNAs represent a biochemically defined set of well-translated mRNAs that respond coherently to loss of 40S recycling factors, eIF2α phosphorylation, and a deficit in 40S subunit abundance.

Figure 6. mRNAs showing relative TE increases in response to deletion of TMA64/TMA20, increased eIF2α phosphorylation, or 40S subunit depletion have a strong propensity to form the closed-loop intermediate.

(A–F) Cumulative distribution function (CDF) plots of changes in TEs (log2∆TE) (A, C, E) or mRNA levels (log2∆mRNA) (B, D, F) for all mRNAs (black) or the 386 SCL mRNAs (red) in the tma∆∆ mutant versus WT cells (A–B), in SM-treated versus untreated WT cells (C–D), and in the rps26∆∆ mutant versus WT cells (E–F). p values were calculated using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test.

Figure 6—figure supplement 1. Strong Closed-Loop (SCL) mRNAs show attributes of highly translated mRNAs.

Figure 6—figure supplement 2. The tma∆∆ mutations exacerbate the inhibitory effect of cap-proximal stem-loop structures on expression of luciferase reporter mRNAs.

The tma∆∆ mutations preferentially impair expression of a reporter mRNA harboring a strong cap-proximal secondary structure

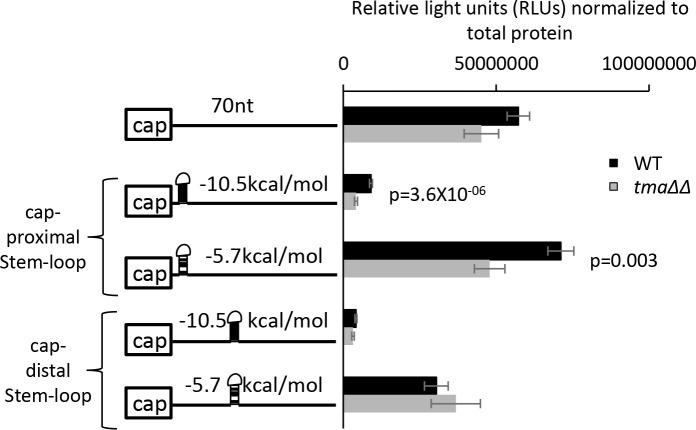

We reasoned that if the tma∆∆ mutations reduce the abundance of 43S PICs in the manner suggested above, then they should impair the translation of luciferase reporter mRNAs described previously (Sen et al., 2016) harboring insertions expected to form stable secondary structures close to the capped 5’ end predicted to impede 43S PIC attachment. Insertion of a stem-loop (SL) structure of predicted stability of −10.5 kcal/mol five nt from the transcription start site strongly impairs luciferase production in WT cells compared to expression of the parental LUC mRNA reporter lacking an insertion, and to the reporter harboring an insertion of lower predicted stability (−5.7 kcal/mol) at the same cap-proximal location (Figure 6—figure supplement 2, WT data, rows 1–3). An even greater reduction in luciferase expression in WT cells was conferred by the more stable −10.5 kcal/mol SL inserted at a cap-distal position 44 nt from the 5’ end, and a moderate reduction was observed for the weaker SL inserted at the same location (Figure 6—figure supplement 2, WT data, rows 4–5 versus 1), all in agreement with our previous findings (Sen et al., 2016). Importantly, the tma∆∆ mutations produced significant reductions in expression for the two reporters harboring cap-proximal SLs, with a particularly strong effect on the reporter bearing the more stable SL (Figure 6—figure supplement 2, cf. tma∆∆ versus WT data, rows 2–3 versus 1). In contrast, the tma∆∆ mutations had no significant effects on expression of the two reporters containing the cap-distal SLs, designed to impede ribosomal scanning versus PIC attachment (Figure 6—figure supplement 2, cf tma∆∆ versus WT data, rows 4–5), even though both of these SL insertions impaired expression in WT cells. These findings support the idea that eliminating the 40S recycling factors leads to a defect in translation initiation that preferentially affects mRNAs that are inefficiently translated owing to a reduced ability to recruit 43S PICs to the 5’ end.

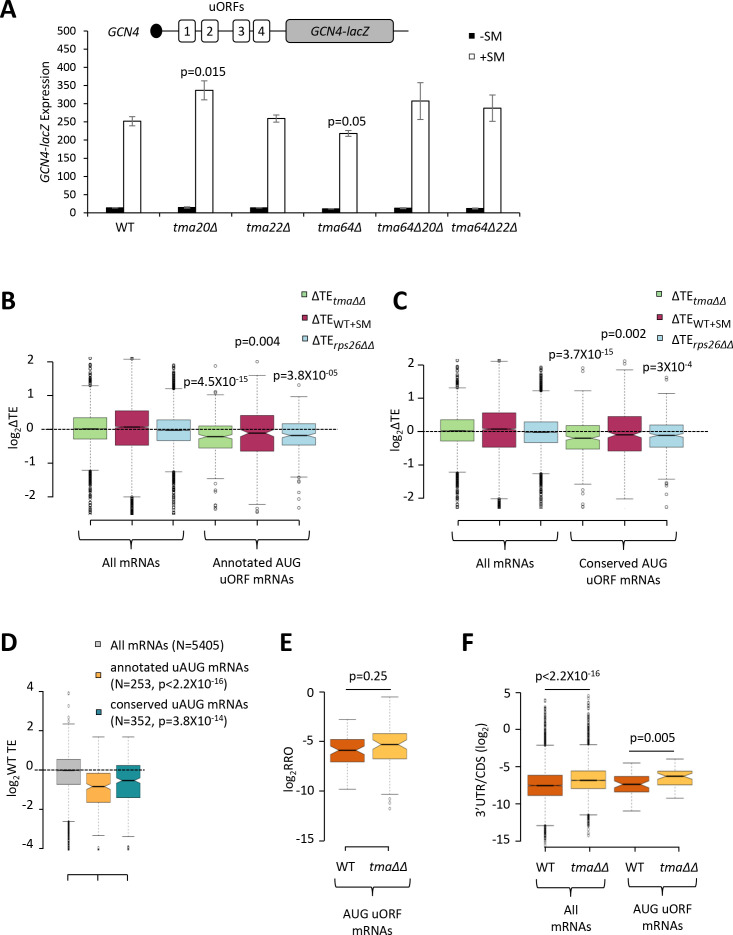

Examining the importance of Tma proteins for translational control by uORFs

The foregoing results support a role for Tma proteins in generating free 40S subunits to support 43S PIC assembly through their functions in ribosome recycling. We next examined whether the Tma proteins might be required for reinitiation at downstream CDSs following uORF translation in uORF-containing mRNAs, as noted above for MCT-1 and DENR in animal cells. GCN4 is the best characterized yeast mRNA exhibiting efficient reinitiation, as ~50% of the 40S subunits that initiate at uORF1 can resume scanning downstream after completing uORF1 translation. Under non-starvation conditions the majority of these 40S subunits reinitiate at uORFs 2–4 and undergo translation termination and ribosome recycling before reaching the GCN4 AUG. In starved cells where eIF2α is phosphorylated, ~50% of such ‘re-scanning’ 40S subunits can bypass the remaining uORFs 2–4 and reinitiate instead at the GCN4 AUG (Hinnebusch, 2005). If the Tma proteins enhance reinitiation on GCN4 mRNA, then either single or double deletions of the TMA genes should reduce translation of the GCN4 CDS in starved cells. To address this possibility, we examined a GCN4-lacZ reporter containing the native promoter and 5’UTR with all four uORFs intact, which has been used extensively to decipher the delayed reinitiation mechanism of GCN4 translational control (Hinnebusch, 2005). In WT cells, expression of this reporter is low in non-starved cells and increases >10-fold on starvation of WT cells for Ile/Val using SM treatment (Figure 7A, columns 1–2). It was previously shown that the starvation-induced increased expression of this reporter is completely dependent on the Gcn2 kinase and the uORFs (Mueller and Hinnebusch, 1986). Importantly, none of the single or double deletions of the three TMA genes produced a significant reduction in GCN4-lacZ expression in SM-treated cells, except for a small ~15% reduction in the tma64∆ single mutant (Figure 7A, white bars). The tma20∆ mutation conferred a ~33% increase in GCN4-lacZ expression; however, as the tma22∆ mutation had no effect, it is difficult to ascribe the modest expression change conferred by the tma20∆ mutation to inactivation of the Tma20/Tma22 heterodimer. Moreover, the fact that neither the tma64∆tma20∆ nor tma64∆tma22∆ double mutant showed significant changes in GCN4-lacZ induction (Figure 7A, white bars, columns 9–12 versus 1–2) suggests that neither the eIF2D nor MCT-1/DENR yeast orthologs are required for reinitiation at GCN4 following uORF1 translation when TC levels are reduced by eIF2α phosphorylation.

Figure 7. Effects of eliminating the 40S recycling factors on translational control by uORFs.

(A) The GCN4-lacZ reporter (depicted schematically) was introduced on plasmid p180 into WT and the indicated yeast mutant strains. Three independently transformed colonies for each strain were cultured in SC-Ura medium at 30°C to log-phase (-SM) or treated with SM at 0.5 μg/mL after 2 hr of growth in SC-Ura and cultured for an additional 4 hr before harvesting. Specific β-galactosidase activities (in units of nmoles of o-nitrophenyl-β-D-galactopyranoside (ONPG) cleaved per min per mg of total protein) were measured in WCEs. Error bars are ± SEMs, and p values were calculated using the student’s t-test. (B–C) Notched box plots showing the log2ΔTE values for all mRNAs or mRNAs containing annotated (B) or conserved (C) AUG uORFs, conferred by the tma∆∆ mutations (green), SM treatment of WT cells (maroon) or the rps26∆∆ mutations (cyan). A few outliers were omitted from the plots to expand the y-axis scale. p values were calculated using the Mann-Whitney U test for the differences between the AUG uORF-containing mRNAs and all mRNAs for each of the three mutations/conditions. (D) Notched box plots showing the log2WT TEs for all expressed mRNAs or for the groups of mRNAs with annotated or conserved AUG uORFs. A few outliers were omitted to expand the y-axis scale. p values were calculated using the Mann-Whitney U test for the differences between the AUG uORF-containing mRNAs and all mRNAs. (E) Notched box plot showing log2RRO values for all AUG uORFs and their corresponding main CDSs in WT and the tma∆∆ mutant. A few outliers were omitted to expand the y-axis scale. The p value was calculated using the Mann-Whitney U test. (F) Notched box plot showing log2(3’UTR:ORF) ratios for all mRNAs or all AUG uORF-containing mRNAs in WT and the tma∆∆ mutant. To interrogate the same number of mRNAs in WT and the tma∆∆ mutant, one footprint read (arbitrary value) was added to all the reads obtained after aligning the sequence data. A few outliers were omitted to expand the y-axis scale. p values were calculated using the Mann-Whitney U test for the differences between WT and the tma∆∆ mutant.

Figure 7—figure supplement 1. Effects of the tma∆∆ mutations on translational control by uORFs.

There was also no effect of the tma∆∆ mutations on GCN4-lacZ expression in non-starvation conditions (Figure 7A, black bars), consistent with results in Figure 4A for native GCN4 mRNA. These findings imply that the strong repression exerted by uORFs 3–4 in non-starved WT cells, which should depend on efficient recycling of post-TerCs following termination at these inhibitory uORFs, does not require the Tma proteins. Although this might seem surprising, eliminating the Tma proteins does not confer a recycling defect as severe as that given by depletion of ABCE1/Rli1, which impairs the first step of ribosome recycling (Young et al., 2015; Young et al., 2018), suggesting that the second step of recycling can occur at appreciable levels without the Tma factors. Presumably, this Tma-independent pathway is sufficient for robust 40S recycling at the stop codons of GCN4 uORFs 3 and 4.

Going beyond the case of GCN4, we next interrogated a previously identified group of mRNAs containing uORFs, initiating with either AUG (262 mRNAs) or one of the nine near-cognate triplets (with a single mismatch to AUG; 1044 mRNAs), which showed evidence of translation in multiple ribosome profiling datasets from various mutant and WT strains (Zhou et al., 2020). Based on previous findings that uORFs initiating with AUG codons are more likely to inhibit initiation at downstream CDSs compared to uORFs with near-cognate start codons (Arribere and Gilbert, 2013; Hinnebusch et al., 2016), we examined the TE changes of the main CDS for the group of 262 mRNAs containing AUG uORFs with evidence of translation in our ribosome profiling data for both the tma∆∆ and WT strains, and for a second set of 385 mRNAs harboring members of a group of 438 evolutionarily conserved AUG uORFs identified by McManus et al. (Spealman et al., 2018). Both groups of mRNAs exhibit significant reductions in CDS TE in the tma∆∆ mutant versus WT cells (Figure 7B–C, columns 4), consistent with the possibility that reinitiation at downstream CDSs following uORF translation is diminished in the tma∆∆ mutant. However, we found that these two groups of mRNAs also display a lower than average TE in WT cells (Figure 7D), and hence, might exhibit TE reductions in the tma∆∆ mutant owing to reduced competition for limiting 43S PICs. In addition to containing uORFs, these mRNAs could have other features, such as long or structured 5’UTRs, that impede 43S PIC attachment and confer reduced initiation rates when 43S PIC levels decline in the tma∆∆ mutant. Indeed, both groups of AUG uORF-containing mRNAs also exhibit TE reductions on SM treatment of WT cells or depletion of Rps26 (Figure 7–C, columns 5–6), conditions that are not predicted to impair possible functions of Tma proteins in reinitiation downstream of uORFs. Thus, it is difficult to ascribe the TE reductions conferred by the tma∆∆ mutations for mRNAs with AUG uORFs to diminished reinitiation following uORF translation.

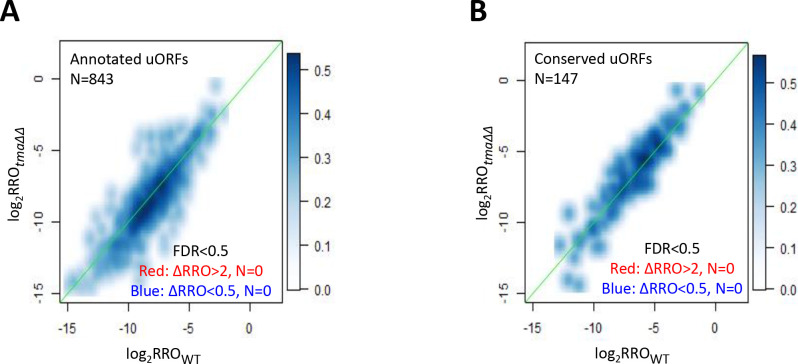

As an orthogonal approach to detecting a role for the Tma proteins in promoting reinitiation, we reasoned that a reduction in reinitiation following uORF translation in the tma∆∆ mutant should confer an increase in the ratio of RPFs in the uORF versus CDSs, which we termed relative ribosome occupancy (RRO). Applying differential expression analysis using DESeq2 to identify statistically significant changes in RRO values revealed that none of the 843 annotated uORFs initiating with either AUG or near-cognate start codons, nor any of the evolutionarily conserved translated uORFs identified by McManus et al. (Spealman et al., 2018), showing evidence of translation in our WT and tma∆∆ strains exhibited significant changes in RRO in the tma∆∆ mutant versus WT cells, even at a relatively non-stringent FDR of 0.5 (Figure 7—figure supplement 1A–B). Furthermore, the group of 63 mRNAs with 70 annotated AUG-initiated uORFs showed no significant difference in median RRO in the tma∆∆ mutant versus WT cells (Figure 7E). In contrast, the same group of AUG uORF-containing mRNAs displayed a significant increase in the ratio of RPFs in 3’UTRs versus the main CDS, indicative of increased (not decreased) reinitiation following termination at the main CDS stop codons in the tma∆∆ mutant (Figure 7F, column 4 versus 3), which is comparable in magnitude to that seen for all mRNAs (Figure 7F, column 2 versus 1). Thus, our results provide no evidence that the Tma proteins enhance reinitiation following uORF translation in yeast cells.

Previous findings on reporter mRNAs in cell extracts suggested that Tma proteins serve to inhibit, rather than promote, reinitiation downstream of uORFs, presumably by stimulating the recycling of 40S post-TerCs at uORF stop codons (Young et al., 2018). In this event, a decrease (rather than increase) in RRO might be expected for the AUG uORF-containing mRNAs in the tma∆∆ mutant owing to increased reinitiation at downstream CDS. As shown in Figure 7E, a decrease in RRO was not observed in the tma∆∆ mutant. Note, however, that the RPF densities might increase in the uORFs owing to queuing of 80S ribosomes behind the stalled 40S post-TerCs at the uORF stop codons, which could offset an increase in RPFs in the downstream CDSs conferred by enhanced reinitiation, and yield no net change in RRO between the tma∆∆ mutant and WT. If so, this would confound our ability to detect increased reinitiation at the main CDSs conferred by impaired recycling at uORF stop codons by examining RRO changes.

Discussion

In this study, we set out to determine whether impairing the second step of ribosome recycling by eliminating Tma64/Tma20, and the predicted sequestration of 40S subunits in either stalled 40S post-TerCs, in 43S PICs scanning 3’UTRs, or in 80S ribosomes translating 3’UTR ORFs, has an impact on global TEs in yeast cells. We also wondered whether eliminating Tma64 would alter the TEs of any mRNAs owing to loss of its possible function as an alternative to eIF2 for recruiting Met-tRNAi to AUG start codons in the manner demonstrated in vitro for its mammalian counterpart, eIF2D. We found that the tma∆∆ mutant lacking both Tma64 and Tma20 exhibits reduced bulk polysome assembly, consistent with a reduced rate of translation initiation on many mRNAs; and by ribosome profiling we observed altered TEs of specific mRNAs, with sizable groups undergoing increases or decreases in relative TE compared to their values in isogenic WT cells. These groups of upregulated and down-regulated mRNAs were enriched for diametrically opposed properties. The mRNAs translationally upregulated in the tma∆∆ mutant tend to be well-translated in WT cells and to have short CDS and 5’UTRs, strong Kozak AUG contexts, to be unusually abundant and to have longer than average half-lives—all attributes of well-translated ‘strong’ mRNAs. The mRNAs translationally down-regulated in the tma∆∆ mutant tend to be poorly translated in WT cells and to exhibit all of the opposite properties characteristic of ‘weak’ mRNAs. The tma64∆ single mutant, in contrast, displays none of the hallmarks of impaired 40S recycling, shows no reduction in bulk polysome assembly, and exhibits no statistically significant changes in TE for any mRNAs in our profiling experiments. These results suggest that the translation changes in the tma∆∆ mutant are associated with defective ribosome recycling rather than the absence of Tma64/eIF2D per se and any possible role it might play in Met-tRNAi recruitment in yeast. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that MCT-1/DENR can substitute completely for eIF2D in providing a WT level of eIF2-independent Met-tRNAi recruitment in the tma64∆ single mutant, and that complete loss of this function in the tma∆∆ mutant contributes to the reprogramming of TEs.

Strikingly, the pattern of TE changes conferred by the tma∆∆ mutations was also evident in the translational reprogramming that accompanies induction of eIF2α phosphorylation by Gcn2 on starvation for amino acids Ile/Val, and also that conferred by depletion of essential 40S subunit protein Rps26. In particular, the group of highly translated ‘SCL’ mRNAs with a heightened propensity for closed-loop formation, owing to their elevated occupancies of eIF4F and PABP, and the group of RPG mRNAs that are strongly enriched in the SCL group (Figure 6—figure supplement 1G), tend to show increased TEs in all three conditions of tma∆∆ mutations, SM treatment of WT cells, and depletion of Rps26. There was also a significant enrichment for ‘weak’ mRNAs among those down-regulated in all three conditions. These same trends were evident on SM treatment of the gcn4∆ mutant, showing that they occur independently of the widespread transcriptional changes conferred by Gcn4 in SM-treated WT cells. Given that eIF2α phosphorylation reduces TC assembly, a key component of 43S PICs, and that both the tma∆∆ mutations and depletion of Rps26 reduce the abundance of free 40S subunits available for PIC assembly, we suggest that the reduced concentration of 43S PICs that should exist in each case is a key factor that skews the competition between strong and weak mRNAs to favor strong mRNAs, and that this altered competition is an important driver of TE changes common to all three conditions. Supporting the idea that the tma∆∆ mutations impair translation initiation by limiting the availability of 43S PICs, they preferentially reduced expression of LUC reporter mRNAs harboring stem-loops inserted close to the mRNA 5’ end, which are expected to impair 43S PIC attachment, compared to reporters bearing cap-distal insertions or the parental reporter lacking a stem-loop insertion.

We note that the tma∆∆ mutant does not exhibit a reduction in the ratio of free 40S to 60S subunits (Figure 1C (ii) versus (i)), ostensibly at odds with our suggestion that the 40S recycling defect in this mutant limits the availability of free 40S subunits for 43S PIC assembly. It is expected that a fraction of the unrecycled 40S subunits will have moved from stop codons and are scanning the 3’UTR to generate the increased 3’UTR translation previously demonstrated in the tma∆∆ mutant (Young et al., 2018) and observed here (Figure 1B). Such 40S post-TerCs, located either at stop codons or scanning in 3’UTRs, may dissociate from mRNA during polysome fractionation by sucrose density gradient centrifugation because they lack base-pairing between a bound tRNA and an mRNA codon—a property which necessitated the use of formaldehyde fixation to capture scanning 40S subunits in 40S profiling experiments (Archer et al., 2016; Sen et al., 2019). If so, this dissociation would prevent us from observing the predicted reduction in free 40S subunits. We have also proposed that sequestration of 40S subunits in the 80S ribosomes engaged in abnormal 3’UTR translation in the tma∆∆ mutant, which occurs on essentially all 3’UTRs (Young et al., 2018), also contributes to the reduced availability of free 40S subunits for PIC assembly in this mutant; and this sequestration also will not reduce the free 40S/60S ratio. Finally, the tma20∆ deletion was shown to confer an elevated free 40S/60S ratio, which may result from a 60S biogenesis defect (Fleischer et al., 2006) and this could offset the depletion of free 40S subunits expected from accumulation of unrecycled 40S subunits at stop codons and in 3’UTRs in the tma∆∆ mutant. Nevertheless, we cannot eliminate the possibility that the impaired ribosome recycling in the tma∆∆ mutant is not the major defect responsible for the reprogramming of translation with features characteristic of a reduction in 43S PIC assembly. As noted above, the complete loss of eIF2-independent Met-tRNAi recruitment could be involved, or a defect in ribosome biogenesis that results in aberrant 40S subunits in addition to reduced 60S subunit levels might exist, either of which could be exacerbated by defective 40S recycling to confer the reprogramming of TEs observed in the tma∆∆ mutant.