Abstract

Background & Aims:

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a significant clinical event in cirrhosis yet contemporary population-based studies on the impact of AKI on hospitalized cirrhotics are lacking. We aimed to characterize longitudinal trends in incidence, healthcare burden and outcomes of hospitalized cirrhotics with and without AKI using a nationally representative dataset.

Methods:

: Using the 2004–2016 National Inpatient Sample (NIS), admissions for cirrhosis with and without AKI were identified using ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes. Regression analysis was used to analyze the trends in hospitalizations, costs, length of stay and inpatient mortality. Descriptive statistics, simple and multivariable logistic regression were used to assess associations between individual characteristics, comorbidities, and cirrhosis complications with AKI and death.

Results:

In over 3.6 million admissions for cirrhosis, 22% had AKI. AKI admissions were more costly (median $13,127 [IQR $7,367-$24,891] vs. $8,079 [IQR $4,956–$13,693]) and longer (median 6 [IQR 3–11] days vs. 4 [IQR 2–7] days). Over time, AKI prevalence doubled from 15% in 2004 to 30% in 2016. CKD was independently and strongly associated with AKI (adjusted odds ratio 3.75; 95% CI 3.72–3.77). Importantly, AKI admissions were 3.75 times more likely to result in death (adjusted odds ratio 3.75; 95% CI 3.71–3.79) and presence of AKI increased risk of mortality in key subgroups of cirrhosis, such as those with infections and portal hypertension-related complications.

Conclusions:

The prevalence of AKI is significantly increased among hospitalized cirrhotics. AKI substantially increases the healthcare burden associated with cirrhosis. Despite advances in cirrhosis care, a significant gap remains in outcomes between cirrhotics with and without AKI, suggesting that AKI continues to represent a major clinical challenge.

Keywords: Cirrhosis, Portal hypertension, Renal failure, Chronic kidney disease, National inpatient sample

Lay summary

Sudden damage to the kidneys is becoming more common in people who are hospitalized and have cirrhosis. Despite advances in cirrhosis care, those with damage to the kidneys remain at higher risk of dying.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is an abrupt decrease in kidney function; it is reported to occur in approximately 20% of hospitalized patients with cirrhosis.1–3 AKI in cirrhosis is associated with high short-term mortality4,5 and poor outcomes post liver trans-plantation.6 Conventional risk factors for AKI and its associated mortality have been linked to certain complications of cirrhosis (e.g. ascites,7 gastrointestinal bleeding,8 spontaneous bacterial peritonitis [SBP]9) and with advancing stages of cirrhosis.1,2 There have been recent shifts in the epidemiology of cirrhosis-related hospitalizations10,11 and improved cirrhosis-related care,12 as well as an increased recognition of chronic kidney disease (CKD) and non-SBP infections as prognostic factors and risk factors for AKI.13–16 It is unclear, however, if these conventional determinants are still valid.

Population-based studies describing the current trends of AKI epidemiology, risk factors, and outcomes in hospitalized patients with cirrhosis are sparse. Prior studies on the trends and outcomes of AKI are based on a sub-selection of patient population studies or are limited to tertiary care referral centers,4,5,17–20 thus limiting the generalizability of findings. Furthermore, the additive risk of AKI for mortality within the spectrum of common cirrhosis-related complications, particularly at a population level, is currently unknown. Thus, using a contemporary national database, the aims of this study were to i) estimate trends in AKI prevalence and outcomes in hospitalized patients with cirrhosis; ii) identify risk factors associated with AKI in hospitalized patients with cirrhosis and (iii) determine the impact of AKI on inpatient mortality within various cirrhosis-related complications.

Patients and methods

Data source

Hospital discharges were selected from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) National Inpatient Sample (NIS) databases, from 2004 through 2016.21 The NIS is the largest all-payer inpatient database in the US, containing data from a sample of discharges covering 97% of the US population, estimating more than 35 million hospitalizations nationally. From 2004–2011, the NIS includes 100% of discharges from a sample of approximately 1,000 hospitals. Starting 2012, the NIS captures a 20% stratified sample of discharges from all U.S. community hospitals. The NIS excludes rehabilitation and long-term acute care hospitals. Further details on the NIS design are available through HCUP’s online resources.22 For all years, each individual hospitalization is de-identified and carries demographic details including age, sex, race, race/ethnicity, insurance provider, zip code-based income quartile. We also extracted hospital characteristics, discharge status, total charges, and length of stay. Reason for admission, etiology of cirrhosis, complications related to cirrhosis or portal hypertension, and presence of AKI and comorbidities were extracted through ICD-9 or 10 codes (ICD-10 was used from the 4th quarter of 2015). We primarily identified diagnosis codes by searching prior literature,11,23–25 as well as www.ICD9Data.com and www.ICD10Data.com, which crosswalk between ICD-9 and ICD-10. These codes are summarized in Table S1.

Inclusion criteria

Admission records from 2004 to 2016 for all hospital discharges for individuals >18 years-old were assessed for inclusion. Within these records, we considered both primary and secondary diagnosis to identify admission records with cirrhosis. Similar to prior NIS studies,23,26,27 admissions were included in the cirrhosis cohort if they contained at least 1 cirrhosis- or portal hypertension-related complication (SBP, ascites, hepatic encephalopathy [HE], variceal hemorrhage [VH], hepatocellular carcinoma [HCC] and hepatorenal syndrome, Table S1). The cirrhosis cohort was further categorized into admissions with AKI and those without AKI based again on primary and secondary diagnosis codes (Table S1).

Risk factors and outcomes definitions

Risk factors for AKI included patient-level demographics (age, gender, race, zip code-based income quartile, admission payer type, origin of admission, type of hospital, hospital region), comorbid conditions (e.g. diabetes, hypertension, CKD of any stage, and Elixhauser comorbidity index [EI]),28,29 and complications related to cirrhosis (SBP, non-SBP infections, sepsis, ascites, HE, VH, and HCC). Clinical variables were defined using the presence of ICD codes as described above and delineated in Table S1. Analyzed outcomes were in-hospital death, length of hospital stay, and total hospitalization cost.

Statistical analysis

The unit of analysis is each unique hospitalization. Individuals with repeated admissions are represented on multiple occasions. For each hospitalization record, admission characteristics were compared by AKI status (no-AKI and AKI) and by inpatient mortality (Alive and Dead). Continuous variables were assessed as weighted median with IQR and categorical variables were reported using weighted proportions. The overall effect of each categorical variable on AKI status or death was assessed using simple logistic regression. All of the analyses incorporated sampling weights provided by HCUP.30 Cost-to-Charge Ratio files published by HCUP were used to calculate costs from the charges provided in the NIS database. All costs are reported using 2016 average inflation-adjusted dollars.

We examined trends in in-hospital mortality, length of stay and cost of hospitalization. For in-hospital mortality, the trend in probability (proportion) over time was modeled using logistic regression. For cost, the trend in median cost over time was modeled using quantile regression. Because length-of-stay is integer valued with primarily small numbers, we initially modeled the mean length-of-stay using Poisson regression; however, we observed overdispersion relative to the Poisson, so overdispered Poisson regression was used. For all analyses we included effects of time and AKI as well as the time-AKI interaction effect. Because of the large time span covered, we did not assume a constant (linear) trend over time, but, instead, explored up to 5th-order polynomial effects over time for all models. For each outcome, the final model (i.e., the order of the polynomial) was selected via a combination of visual inspection of model-fit (comparing the observed to model-predicted values) and either the Akaik einformatio ncriterio n(AIC) (fo rin-hospita lmortality) or, because neither overdispersed-Poisson nor quantile regression are likelihood based (thus AIC cannot be calculated), examination of the statistical significance of higher-order terms.

Next, we explored predictors of AKI and death via a multivariable logistic model where the response was the presence/absence of the outcome and predictors were selected based on associations with the outcome on univariate analysis and prior literature. Variables included age, gender, race/ethnicity, median income by zip code (AKI model only), causes of liver disease, EI, CKD, infections (pneumonia, urinary tract infection, SBP), sepsis, mechanical ventilation, and cirrhosis complications (ascites, HE, VH and HCC) and AKI (death model only). Observations with missing values for gender and race were excluded from this analysis. For non-binary categorical variables, categories are listed in their respective tables.

We then examined the effect of AKI on in-hospital mortality for groups with various complications using multivariable logistic regression where the response was death (yes/no) and predictors included AKI as well as age and EI as quantitative variables. For each complication examined, we subset the data to only those individuals with that complication. Odds ratios for in-hospital mortality for those with vs. without AKI are given, adjusted for age and EI.

Data management and analysis were performed using SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R Core Team (2016).

For further details regarding the materials used, please refer to the CTAT table and supplementary information.

Results

Trends in burden and outcomes

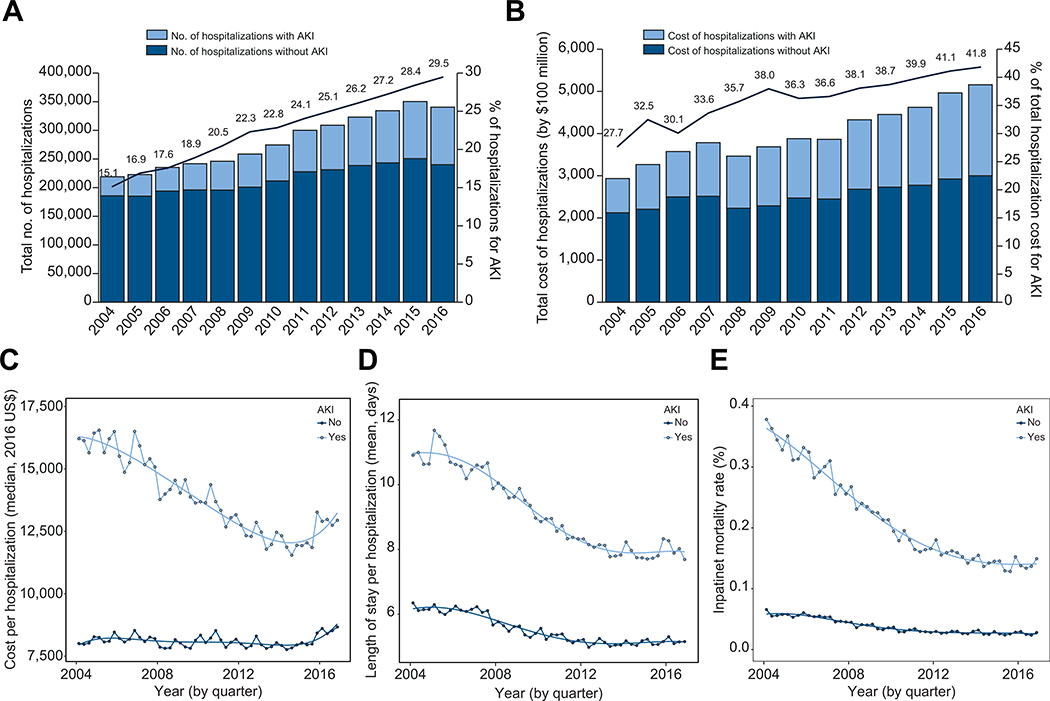

During the study period, the total weighted number of admissions for patients with cirrhosis was 3,673,711, of whom 2,847,666 (78%) did not have AKI and 826,044 (22%) had AKI. The incidence and overall cost of AKI-related hospitalizations increased steadily from 2004 to 2016 (Fig. 1A,B). By 2016, AKI-related hospitalizations made up 29.5% of all cirrhosis admissions compared to 15.1% in 2004 (Fig. 1A). In addition, AKI-related hospitalizations made up 41.8% of total hospitalization costs among cirrhotics in 2016 compared to 27.7% in 2004. Costs per admission for those with AKI were substantially higher than for those without AKI (AKI $13,127 [IQR $7,367–$24,891] vs. no AKI $8,079 [IQR $4,956–$13,693]) (Table 1). Accordingly, AKI admissions were associated with higher median length of stay (LOS) than admissions without AKI (AKI 6 days [IQR 3–11] vs. no AKI 4 days [IQR 2–7]) (Table 1). For those without AKI, cost per admission was relatively unchanged but decreased dramatically over the study period for those with AKI (Fig. 1C). At the end of the study period, cost per admission for both admissions with and without AKI increased slightly at the end of 2015 into 2016. Similar to costs, LOS for admissions without AKI was relatively unchanged while decreasing over time for those with AKI over the study period (Fig. 1D).

Fig 1. Trends in cirrhosis-related hospitalizations and outcomes by AKI status.

(A) Number of hospitalizations by AKI status and percentage of hospitalizations with AKI over time; (B) cumulative hospitalization costs by AKI status and percentage of costs due to AKI over time; (C) observed and estimated median cost by AKI status based on a 5th order polynomial quantile regression; (D) observed and estimated mean LOS per hospitalization by AKI status based on a 5th order polynomial overdispersed Poisson regression; (E) observed and estimated inpatient mortality rate by AKI status based on a 5th order polynomial logistic regression. AKI, acute kidney injury; LOS, length of stay.

Table 1.

Cohort characteristics and hospital outcomes stratified by AKI status.

| Total cohort N = 3,655,181 (%) | No-AKI n = 2,801,317 (%) | AKI n = 853,864 (%) | p value^ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age* | 57 (50, 66) | 57 (50, 66) | 59 (52, 66) | <0.001 |

| 18–44 | 11.2 | 12.0 | 8.8 | |

| 45–64 | 60.2 | 61.0 | 57.8 | |

| >65 | 28.6 | 27.1 | 33.4 | |

| Male gender | 62.6 | 62.3 | 63.6 | <0.001 |

| Race/ethnicity# | <0.001 | |||

| White | 58.3 | 58.1 | 58.8 | |

| Black | 8.6 | 8.1 | 10.2 | |

| Hispanic | 16.5 | 16.9 | 15.2 | |

| Other | 5.7 | 5.7 | 6.0 | |

| Zip-code based income | <0.001 | |||

| Quartile 1 (lowest) | 32.2 | 32.6 | 31.0 | |

| Quartile 2 | 25.5 | 25.7 | 25.0 | |

| Quartile 3 | 22.2 | 22.0 | 22.9 | |

| Quartile 4 (highest) | 17.0 | 16.5 | 18.3 | |

| Insurance/payer | <0.001 | |||

| Medicaid | 23.5 | 24.0 | 21.6 | |

| Medicare | 41.1 | 40.3 | 43.7 | |

| Private/HMO | 22.6 | 22.1 | 24.3 | |

| Other | 12.6 | 13.3 | 10.1 | |

| Origin of admission | ||||

| Emergency department | 74.6 | 75.3 | 72.2 | <0.001 |

| Transfer | 6.2 | 5.3 | 9.5 | <0.001 |

| Hospital type | ||||

| Teaching hospital | 55.1 | 53.2 | 61.5 | <0.001 |

| Rural hospital | 8.7 | 9.3 | 6.6 | <0.001 |

| Hospital region | <0.001 | |||

| Northeast | 18.2 | 18.1 | 18.6 | |

| Midwest | 18.7 | 18.5 | 19.2 | |

| South | 39.1 | 39.5 | 37.8 | |

| West | 24.0 | 23.9 | 24.4 | |

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| Etiology of cirrhosis | ||||

| Hepatitis C | 27.1 | 27.9 | 24.3 | <0.001 |

| Alcohol | 51.9 | 51.9 | 52.0 | <0.001 |

| NASH | 20.6 | 20.9 | 19.7 | <0.001 |

| Other | 5.0 | 5.1 | 4.7 | <0.001 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Diabetes | 28.8 | 29.4 | 27.0 | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 26.3 | 29.2 | 16.8 | <0.001 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 15.7 | 11.0 | 30.9 | <0.001 |

| Elixhauser index$ | ||||

| 0–2 | 37.2 | 38.6 | 32.6 | <0.001 |

| 3–4 | 46.4 | 45.3 | 50.1 | |

| >5 | 16.4 | 16.1 | 17.2 | |

| Infections (any) | 25.1 | 22.2 | 34.6 | <0.001 |

| Pneumonia | 6.7 | 5.8 | 9.6 | <0.001 |

| Urinary tract infection | 11.8 | 10.3 | 16.6 | <0.001 |

| SBP | 3.6 | 2.7 | 6.6 | <0.001 |

| Sepsis | 9.2 | 6.1 | 19.3 | <0.001 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 9.3 | 6.2 | 19.6 | <0.001 |

| Hemodialysis | 5.3 | 4.1 | 9.0 | <0.001 |

| Cirrhosis complication | ||||

| Ascites | 58.1 | 55.3 | 67.0 | <0.001 |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 32.8 | 30.1 | 41.8 | <0.001 |

| Variceal hemorrhage | 12.2 | 13.2 | 9.2 | <0.001 |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 4.9 | 4.5 | 6.2 | <0.001 |

| Hospital outcome | ||||

| Disposition of patient | <0.001 | |||

| Home | 57.8 | 64.1 | 37.3 | |

| Transfer to another hospital | 3.8 | 3.2 | 5.6 | |

| Transfer to SNF, intermediate care or another facility | 15.5 | 14.2 | 20.0 | |

| Home health care | 13.2 | 12.2 | 16.4 | |

| In-hospital mortality | 7.3 | 3.7 | 19.2 | |

| Cost per admission* | $8,955 (5,357, 15,888) | $8,107 (4,983, 13,695) | $13,219 (7,434, 25,015) | – |

| Length of stay* | 4 (3, 7) | 4 (2, 7) | 6(3,11) | – |

AKI, acute kidney injury; HMO, health maintenance organization; NASH, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis; SNF, skilled nursing facility.

(median, IQR).

About 10% missing.

Modified to exclude liver and renal disease categories.

p value calculated using simple logistic regression p <0.001 considered significant.

Importantly, AKI contributed significantly to inpatient mortality in cirrhotics. While overall mortality was 7.3% in our cohort, patients with AKI had significantly higher mortality compared to patients without AKI, 19.2% vs. 3.7%, p <0.001, respectively (Table 1). Unlike the rising incidence of AKI, however, inpatient mortality decreased from 35.3% in 2004 to 10.0% by 2016 (Fig. 1E). This is in comparison to a smaller decline in mortality seen in cirrhotics without AKI from 5.9% in 2004 to 3.1% in 2016.

Individual and hospitalization characteristics

Individual and hospitalization characteristics for the entire cohort stratified by AKI status are listed in Table 1. The median age for the entire cohort was 57 years (IQR 50–66); the majority were Caucasian (58.3%), male (62.6%), and the most common etiology of cirrhosis was alcohol (51.9%) followed by HCV (27.1%). Compared to admissions without AKI, patients with AKI were older (59 vs. 57 years), more likely to be Black (8.1% vs. 10.2%, p <0.001), and less likely to have HCV (24.3% vs. 27.9%, p <0.001) (Table 1). Interestingly, patients who were transferred for admission or admitted to a teaching hospital had higher percentages of AKI compared to patients without AKI, 9.5% vs. 5.3%, p <0.001 and 61.5% vs. 53.2%, p <0.001, respectively.

Characteristics of comorbid conditions and complications of cirrhosis

Patients with AKI had a higher degree of comorbidities, as measured by EI, compared to those without AKI (Table 1). Specifically, patients with AKI were more likely to have CKD compared to those without AKI (25.8% vs. 6.5%, p <0.001). However, patients with AKI were less likely to have diabetes and hypertension compared to patients without AKI, 27.0% vs. 29.4%, p <0.001 and 16.8% vs. 29.2%, p <0.001, respectively. When considering complications specific to cirrhosis, such as infections, sepsis, ascites, HE, and HCC, admissions with these complications were associated with higher rates of AKI than admissions without these complications (Table 1). However, cases admitted with VH were less likely to have AKI compared to admissions without VH (9.2% vs. 13.2%, p <0.001).

Factors independently associated with AKI

Table 2 describes the independent association between AKI and demographic and clinical characteristics. Older age, male gender, black race, high income by zip code, EI >2, CKD, pneumonia, UTI, SBP, sepsis, mechanical ventilation and complications related to cirrhosis (ascites, HE, VH, and HCC) were found to be independently associated with AKI. Of these variables, CKD had the strongest association with AKI (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 3.75; 95% CI 3.72–3.77) followed by mechanical ventilation (aOR 3.25; 95% CI 3.22–3.28), sepsis (aOR 2.64; 95% CI 2.62–2.67), SBP (aOR 1.90; 95% CI 1.88–1.93), ascites (aOR 1.68; 95% CI 1.67–1.69) and HE (aOR 1.60; 95% CI 1.59–1.61).

Table 2.

Independent predictors of AKI.

| Variable in model* | Adjusted odds ratio^ | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 18–44 | Ref | – |

| 45–64 | 1.15 | (1.14–1.17) |

| >65 | 1.35 | (1.34–1.37) |

| Male gender | 1.10 | (1.10–1.11) |

| Race/Ethnicity | (0.90–0.91) | |

| White | Ref | – |

| Black | 1.10 | (1.09–1.11) |

| Hispanic | 0.89 | (0.88–0.89) |

| Other | 1.00 | (0.99–1.01) |

| Zip-code based income# | ||

| Quartile 1 (lowest) | Ref | – |

| Quartile 2 | 1.04 | (1.03–1.05) |

| Quartile 3 | 1.09 | (1.09–1.10) |

| Quartile 4 (highest) | 1.14 | (1.13–1.15) |

| Etiology of cirrhosis | ||

| Hepatitis C | 0.92 | (0.91–0.93) |

| Alcohol | 1.03 | (1.02–1.04) |

| NASH | 0.84 | (0.83–0.85) |

| Other | 1.00 | (0.99–1.01) |

| Elixhauser index$ | ||

| 0–2 | Ref | – |

| 3–4 | 1.22 | (1.22–1.23) |

| >5 | 1.16 | (1.15–1.17) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 3.75 | (3.72–3.77) |

| Infections | ||

| Pneumonia | 1.05 | (1.04–1.07) |

| Urinary tract infection | 1.52 | (1.51–1.53) |

| Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis | 1.89 | (1.86–1.91) |

| Sepsis | 2.52 | (2.50–2.54) |

| Mechanical ventilation | 3.18 | (3.15–3.21) |

| Cirrhosis complication | ||

| Ascites | 1.67 | (1.66–1.68) |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 1.62 | (1.61–1.62) |

| Variceal hemorrhage | 0.84 | (0.83–0.84) |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 1.57 | (1.55,1.59) |

AKI, acute kidney injury; aOR, adjusted odds ratio; NASH, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis.

If no reference indicated, variable was treated as yes vs. no (i.e. Female, yes vs. no).

Missing in 3.1%, aOR for AKI in missing group 0.95, 95% CI (0.93–0.97).

Modified to exclude liver and renal disease categories.

Adjusted odds ratio calculated using multiple logistic regression, 95% CI which does not include 1.0 was considered significant.

Patient and hospitalization characteristics of patients who died

Of our cohort, 7.3% did not survive the hospitalization. Of all cirrhosis admissions resulting in death (n = 267,091), 61.4% had AKI. Table S2 describes the differences in patient and hospitalization characteristics between those who survived the hospitalization vs. those who died. Those who died had similar demographic characteristics but were more likely to be transferred in (10.6% vs. 5.9%, p <0.001), have alcoholic liver disease (57.9% vs. 51.5%, p <0.001) and were less likely to have nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (11.6% vs. 21.3%, p <0.001). Those who died were also more likely have infections and complications of cirrhosis (Table S3).

Factors independently associated with inpatient mortality

Table 3 describes the independent associations between death and demographic as well as clinical characteristics. Older age, male gender, black race, presence of infections, sepsis, mechanical ventilation and complications related to cirrhosis including ascites, HE, VH, and HCC were found to be independently associated with death. Interestingly, when EI was modified to remove liver and renal disease, a higher EI was not associated with death (EI >5 aOR 0.79; 95% CI 0.78–0.80). Importantly, AKI remained independently associated with death in this model (aOR 3.75; 95% CI 3.71–3.79).

Table 3.

Independent predictors of death.

| Variable in model* | Adjusted odds ratio^ | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 18–44 | Ref | – |

| 45–64 | 1.22 | (1.20–1.24) |

| >65 | 1.79 | (1.75–1.82) |

| Male | 1.03 | (1.02–1.04) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | Ref | – |

| Black | 1.12 | (1.10–1.14) |

| Hispanic | 0.91 | (0.90–0.92) |

| Other | 0.99 | (0.97–1.01) |

| Etiology: alcohol | 1.22 | (1.20–1.23) |

| Elixhauser index# | ||

| 0–2 | Ref | – |

| 3–4 | 0.83 | (0.82–0.84) |

| >5 | 0.67 | (0.66–0.68) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 0.79 | (0.78–0.80) |

| Infections | ||

| Pneumonia | 1.00 | (0.98–1.01) |

| Urinary tract infection | 0.79 | (0.78–0.81) |

| Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis | 1.16 | (1.13–1.18) |

| Sepsis | 3.06 | (3.03–3.10) |

| Mechanical ventilation | 12.95 | (12.81–13.10) |

| Cirrhosis complication | ||

| Ascites | 1.06 | (1.05–1.07) |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 1.52 | (1.50–1.53) |

| Variceal hemorrhage | 1.06 | (1.04–1.08) |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 2.05 | (2.01–2.09) |

| Acute kidney injury | 3.75 | (3.71–3.79) |

If no reference indicated, variable was treated as yes vs. no (i.e. male, yes vs. no).

Modified to exclude liver and renal disease categories.

Adjusted odds ratio calculated using multiple logistic, 95% CI which does not include 1.0 was considered significant.

Impact of AKI on inpatient mortality in cirrhosis subgroups

We looked at the impact of having AKI in different subgroups of cirrhosis admissions. AKI dramatically increased the risk of death in each subgroup (Table 4). Increased odds of death were seen in those with CKD, infections, sepsis or those needing mechanical ventilation when AKI was present. In those with ascites, VH, HE, HCC, and SBP, AKI increased the odds of mortality over 5-fold (Table 4). Notably, after adjusting for age and EI, patients with VH and AKI were over 8 times more likely to die compared to patients with VH without AKI (5.0% vs. 29.1%; aOR 8.05; 95% CI 7.88–8.23).

Table 4.

Risk of death by complication and AKI status.

| Died with complication without AKI (%) | Died with complication and AKI (%) | Adjusted odds ratio* | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full cohort | 3.7 | 19.2 | 6.37 | (6.31–6.42) |

| CKD | 4.5 | 10.4 | 2.43 | (2.38–2.48) |

| Infections | ||||

| Any infection | 5.0 | 21.7 | 5.25 | (5.18–5.33) |

| Pneumonia | 10.0 | 33.9 | 4.50 | (4.40–4.60) |

| Urinary tract infection | 3.8 | 17.8 | 5.46 | (5.34–5.59) |

| SBP | 5.2 | 24.8 | 5.89 | (5.67–6.11) |

| Sepsis | 15.9 | 43.6 | 4.00 | (3.93–4.06) |

| Mechanical ventilation | 30.3 | 57.9 | 3.07 | (3.03–3.11) |

| Cirrhosis complication | ||||

| Ascites | 3.8 | 17.8 | 5.63 | (5.57–5.70) |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 5.5 | 23.9 | 5.54 | (5.47–5.61) |

| Variceal hemorrhage | 5.0 | 29.1 | 8.05 | (7.88–8.23) |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 6.0 | 23.3 | 5.03 | (4.87–5.19) |

AKI, acute kidney injury; CKD, chronic kidney disease; SBP, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.

Adjusted for Age and modified Elixhauser index (excluding liver and renal disease); calculated using multiple logistic regression, 95% Cl which does not include 1.0 was considered significant.

Given the impact of AKI on mortality, we explored factors associated with death within the subgroup with cirrhosis and AKI (Table S3). Patients who died within this subgroup were younger, more often had alcoholic cirrhosis, Medicaid insurance, and were more likely to be transferred from another facility. On univariate analysis, comorbidities were less common in cirrhotics with AKI who died (Table S3). In addition, infections were more common in those who died, most notably pneumonia (16.9% vs. 7.8%, p <0.001). As expected, rates of sepsis and mechanical ventilation are significantly higher in those who died (43.8% vs. 13.5%, p 0.001< and 59.0% vs. 10.2%, p 0.001,< respectively). Looking at complications of cirrhosis, HE and HCC were more common in those with cirrhosis and AKI who died compared to those who survived.

Discussion

Our study looks at over 3.5 million cirrhosis-related admissions over the past 12 years in a large nationally representative sample in the US. Within this sample, we show high healthcare burden associated with cirrhosis-related AKI as well as significant association with inpatient mortality. Our study also highlights differences between cirrhosis admissions with vs. without AKI while providing insight into key trends in cirrhosis admissions by AKI status over time. Importantly, this is the first study describing cirrhosis admissions using the NIS after conversion to ICD-10 codes and provides the most recent national perspective on individuals hospitalized with cirrhosis both with and without AKI.

Over the study period, we document an increasing prevalence of AKI-related admissions from 15% of cirrhosis admissions in 2004 to 30% by 2016. These data are in line with prior studies showing increasing rates of AKI in various large databases in patients without cirrhosis18,31 and with cirrhosis.19,32 Further-more,this increased prevalence is paralleled by increasing total healthcare costs. Our data and prior studies show more healthcare dollars are being spent on cirrhosis admissions over time,11,27 however, we show that a greater proportion of costs are attributed to AKI-related admissions. Specifically, in 2016, 42% or $2.16 billion of the $5.16 billion spent on all admissions with cirrhosis were on those with AKI, compared to only 28% in 2004. Interestingly, our data show that while prevalence and overall costs are increasing, per hospitalization cost and LOS are decreasing. It is possible that our observed trends could be attributed to higher hospitalization rates for milder AKI. The recognition of AKI as a complication of cirrhosis has improved over the past decade; therefore, cases with early or easily reversed AKI may not have been labeled as such in 2004 but are coded for AKI in 2016. In addition, AKI is known to recur; therefore, we may be seeing more readmissions for AKI than previously due to improved survival from each individual hospitalization. While these trends may be partially explained by these coding-related phenomenon, our data continue to show higher costs associated with AKI. Specifically, we show a persistent and substantial gap between LOS and healthcare costs between those with and without AKI. Taken together, our findings show a rising burden of cirrhosis and AKI and emphasize the need to better understand mechanisms driving AKI in the setting of cirrhosis while improving recognition and access to specialty management.

Another important finding of the current study was that cirrhotic patients with AKI were 6 times more likely die in the hospital compared to patients without AKI. After adjusting for relevant clinical predictors of death, AKI remained independently and strongly associated with death. Taking this US-based national sample as a whole, AKI was present in over 60% of cirrhosis admissions that resulted in death. Prior studies have shown that development of AKI portends a significant change in prognosis for those with cirrhosis.4,5 Notably, our study shows that AKI-related in-hospital mortality rates have decreased over time. This is in line with studies in the general hospitalized population with AKI33 and those with cirrhosis.12 In 2016, we note a mortality rate of 10% for AKI-related admissions. This is a lower mortality rate than seen in other tertiary care center-based studies, our estimates are derived for a national sample of all US hospitals including non-teaching urban and rural hospitals where hospital acuity and case complexity have been shown to be lower.23 Furthermore, improved inpatient mortality is likely attributed to improved cirrhosis-related care, in particular, care related to SBP,12 ascites,34 and increased recognition of AKI. Early identification likely promoted earlier initiation of AKI-related care such as resuscitation, nephrology consultation, changing dialysis treatment patterns35 and improved intensive unit care36 over the time period of the study, which could also account for these improvements. Despite these advances in medical care, we observe that a significant gap in mortality remains between those with vs. without AKI further emphasizing the need for continued recognition and management of AKI in cirrhotics.

Besides showing AKI in cirrhosis is a strongly linked with in-hospital death, we have also identified several risk factors that were independently associated with AKI in this large cohort. Noteworthy demographic factors were age, black race, and higher income zip code. The latter is an interesting finding and likely due to access to care37 and therefore early recognition of AKI. While we note that male gender was independently associated with AKI, it is possible that AKI was over-diagnosed in males due to higher serum creatinine compared to women.38 A high burden of comorbidities was strongly associated with AKI, particularly CKD. We found CKD of any stage to be the strongest risk factor, where patients with CKD are 3.75 times more likely to have AKI. Notably, the prevalence of CKD in patients with AKI was 30%. These findings are consistent with those reported form the general population of patients hospitalized with AKI39,40 and in patients with decompensated cirrhosis.15–17 Interestingly, our analysis would indicate that diabetes and hypertension are associated with lower odds of AKI. These findings are in line with others and possibly related to under-coding of certain comorbid conditions such as diabetes and hypertension during a complex hospitalization.27,29,41,42 Moreover, our study confirmed that conventional risk factors for AKI in cirrhosis, particularly infections9,14 and ascites,5,7 continue to remain relevant despite shifts in epidemiology in cirrhosis-related hospitalizations.

Given the substantial risk for mortality in patients with AKI, identifying risk factors for mortality in this sub-population will be crucial for improving survival (e.g. transfer to tertiary care liver transplant center43,44). We found that AKI significantly increases the risk of death in those with infections and sepsis. Surprisingly, the impact of AKI on those with variceal hemorrhage is striking with an 8-fold increase in mortality in those with variceal hemorrhage and AKI vs. those with variceal hemorrhage alone. We suspect that the latter is related to the presence of severe bacterial infections as it is well established that bleeding predisposes to the development of bacterial infections, especially SBP.45,46 Furthermore, it is also likely that AKI may serve as a predictor of mortality and is substantial in these patients as they are often admitted to intensive care unit with hemorrhagic shock and multiorgan failure.43

The current study has several strengths worth highlighting. First, out study cohort included a large number of hospitalized patients with cirrhosis admitted over a decade. Having this large sample size allowed us to perform in-depth analysis on the changing epidemiology, risk factors, and outcomes related to AKI in cirrhosis. Second, we are able to build on prior literature by describing trends in outcomes in cirrhotics, both with and without AKI, using the most recent years of the NIS available. In addition, with the inclusion of all hospitals in rural and urban areas in our data set, our findings are generalizable and therefore reflective of the hospitalized US population with cirrhosis and AKI.

Despite these strengths, we acknowledge several limitations, particularly in relation to the use of an administrative dataset. While discharge codes have been validated to identify groups of admission with cirrhosis, only the first 15 diagnostic codes are captured, subjecting our results to coding bias. In addition, our study spans the transition from ICD-9 to ICD-10 coding. While all codes were carefully cross-mapped between ICD-9 and ICD-10 by the authors, the transition to ICD-10 may introduce variations in coding whose impact may not be understood until more data in the ICD-10 era are available.47 This retrospective dataset limits our ability to comment only on associations between AKI and inpatient outcomes. Moreover, the NIS lacks laboratory data, which is crucial in determining baseline kidney function, stage and severity of AKI as well as severity of liver disease. We could not account for these important variables in our multivariable model. CKD, in particular, is a heterogenous disease and it is not possible to determine duration, etiology, or pathophysiology of renal disease using this dataset. Additionally, it is not known how many patients had renal recovery. However, neither point diminishes the prognostic information captured for this cohort. Finally, as the data are de-identified, we were unable to define the impact of AKI beyond each individual hospitalization or account for re-hospitalizations. These limitations are inherent to datasets such as the NIS and offset by the strengths of the study.

In conclusion, our study provides key insight in the national landscape of hospitalized cirrhotics with and without AKI. AKI is increasingly prevalent in those with cirrhosis and substantially increases the inpatient mortality and healthcare costs associated with cirrhosis. Inpatient mortality is decreasing in those with cirrhosis both with and without AKI. Despite improved recognition of AKI and its impact on cirrhosis, AKI continues to increase mortality in various subgroups of cirrhosis. Furthermore, our study highlights a significant gap in mortality between cirrhotics with and without AKI, suggesting that AKI continues to represent a major clinical challenge for clinicians managing cirrhotics. Future studies are needed to identify strategies which allow for earlier identification of this high-risk group, triggering earlier, potentially preventive, management.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

of an estimated 3.6 million US cirrhosis admissions, 22% had acute kidney injury.

Over time, acute kidney injury prevalence has doubled.

Acute kidney injury admissions were costlier than admissions without the condition.

Chronic kidney disease is strongly associated with acute kidney injury.

Chances of dying were higher for those with acute kidney injury.

Acknowledgments

Financial support

APD is funded by the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease Foundation’s 2017 Career Development Award. ESO is funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health, K23 DK109202. PG has been funded by grant number PI16/00043, integrated in the Plan Nacional I+D+I and co-funded by ISCIII-Subdirección General de Evaluación and European Regional Development Fund FEDER. He is also supported by the AGAUR SGR −01281 Grant. PG is a recipient of an ICREA Academia Award. This work was independent of the funding.

Conflicts of interest

Dr. Naga Chalasani has ongoing paid consulting activities (or had in preceding 12 months) with NuSirt, Abbvie, Afimmune (DS Biopharma), Allergan (Tobira), Madrigal, Siemens, Foresite, Galectin, Zydus, and La Jolla. These consulting activities are generally in the areas of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and drug hepatotoxicity. Dr. Chalasani receives research grant support from Exact Sciences, Intercept, and Galectin Therapeutics where his institution receives the funding. Over the last decade, Dr. Chalasani has served as a paid consultant to more than 35 pharmaceutical companies and these outside activities have regularly been disclosed to his institutional authorities. Dr. Pere Ginès declares that he has received research funding from Mallinckrodt, Grifols and Gilead S.A. He has participated on Advisory Boards for Novartis, Promethera, Sequana, Gilead, Martin Pharmaceuticals, Ferring Pharmaceuticals and Grifols.Remaining authors have no disclosures to report. None of the aforementioned disclosures are related to the study. Please refer to the accompanying ICMJE disclosure forms for further details.

Abbreviations

- AHRQ

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

- AIC

Akaike information criteria

- AKI

acute kidney injury

- aOR

adjusted OR

- CKD

chronic kidney disease

- EI

Elixhauser index

- HCUP

Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- HE

hepatic encephalopathy

- LOS

length of stay

- NIS

National Inpatient Sample

- NASH

non-alcoholic steatohepatitis

- OR

odds ratio

- SBP

spontaneous bacterial peritonitis

- VH

variceal hemorrhage

Footnotes

Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2020.04.043.

References

Author names in bold designate shared co-first authorship

- [1].Garcia-Tsao G, Parikh CR, Viola A. Acute kidney injury in cirrhosis. Hepatology 2008;48:2064–2077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Gines P, Schrier RW. Renal failure in cirrhosis. N Engl J Med 2009;361:1279–1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Angeli P, Gines P, Wong F, Bernardi M, Boyer TD, Gerbes A, et al. Diagnosis and management of acute kidney injury in patients with cirrhosis: revised consensus recommendations of the International Club of Ascites. J Hepatol 2015;62:968–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Fede G, D’Amico G, Arvaniti V, Tsochatzis E, Germani G, Georgiadis D, et al. Renal failure and cirrhosis: a systematic review of mortality and prognosis. J Hepatol 2012;56:810–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Belcher JM, Garcia-Tsao G, Sanyal AJ, Bhogal H, Lim JK, Ansari N, et al. Association of AKI with mortality and complications in hospitalized patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology 2013;57:753–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Nair S, Verma S, Thuluvath PJ. Pretransplant renal function predicts survival in patients undergoing orthotopic liver transplantation. Hepatology 2002;35:1179–1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Gines P, Sola E, Angeli P, Wong F, Nadim MK, Kamath PS. Hepatorenal syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2018;4:23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Cardenas A, Gines P, Uriz J, Bessa X, Salmeron JM, Mas A, et al. Renal failure after upper gastrointestinal bleeding in cirrhosis: incidence, clinical course, predictive factors, and short-term prognosis. Hepatology 2001;34:671–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Terra C, Guevara M, Torre A, Gilabert R, Fernandez J, Martin-Llahi M, et al. Renal failure in patients with cirrhosis and sepsis unrelated to spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: value of MELD score. Gastroenterology 2005;129:1944–1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Asrani SK, Hall L, Hagan M, Sharma S, Yeramaneni S, Trotter J, et al. Trends in chronic liver disease-related hospitalizations: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol 2019;114:98–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Kim D, Cholankeril G, Li AA, Kim W, Tighe SP, Hameed B, et al. Trends in hospitalizations for chronic liver disease-related liver failure in the United States, 2005–2014. Liver Int 2019;39:1661–1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Schmidt ML, Barritt AS, Orman ES, Hayashi PH. Decreasing mortality among patients hospitalized with cirrhosis in the United States from 2002 through 2010. Gastroenterology 2015;148:967–977 e962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Moreau R, Jalan R, Gines P, Pavesi M, Angeli P, Cordoba J, et al. Acute-on-chronic liver failure is a distinct syndrome that develops in patients with acute decompensation of cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 2013;144:1426–1437. 1437.e1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Wong F, OĽeary JG, Reddy KR, Patton H, Kamath PS, Fallon MB, et al. New consensus definition of acute kidney injury accurately predicts 30-day mortality in patients with cirrhosis and infection. Gastroenterology 2013;145:1280–1288 e1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Wong F, Reddy KR, OĽeary JG, Tandon P, Biggins SW, Garcia-Tsao G, et al. Impact of chronic kidney disease on outcomes in cirrhosis. Liver Transpl 2019;25:870–880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Bassegoda O, Huelin P, Ariza X, Sole C, Juanola A, Gratacos-Gines J, et al. Development of chronic kidney disease after acute kidney injury in patients with cirrhosis is common and Impairs clinical outcomes. J Hepatol 2020;72:1132–1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Wong F, OĽeary JG, Reddy KR, Garcia-Tsao G, Fallon MB, Biggins SW, et al. Acute kidney injury in cirrhosis: baseline serum creatinine predicts patient outcomes. Am J Gastroenterol 2017;112: 1103–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Nadkarni GN, Patel A, Simoes PK, Yacoub R, Annapureddy N, Kamat S, et al. Dialysis-requiring acute kidney injury among hospitalized adults with documented hepatitis C Virus infection: a nationwide inpatient sample analysis. J Viral Hepat 2016;23:32–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Nadkarni GN, Simoes PK, Patel A, Patel S, Yacoub R, Konstantinidis I, et al. National trends of acute kidney injury requiring dialysis in decompensated cirrhosis hospitalizations in the United States. Hepatol Int 2016;10:525–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Karagozian R, Bhardwaj G, Wakefield DB, Verna EC. Acute kidney injury is associated with higher mortality and healthcare costs in hospitalized patients with cirrhosis. Ann Hepatol 2019;18:730–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Introduction to HCUP National Inpatient Sample (NIS) [cited December 20, 2019]; Available at, Dec 17, 2019. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nis/nisdbdocumentation.jsp; Dec 17, 2019.

- [22].HCUP Sample Design: National Databases [cited April 1, 2020]; Available at, Nov 15, 2018. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/tech_assist/sampledesign/508_compliance/index508_2018.jsp; Nov 15, 2018.

- [23].Mellinger JL, Richardson CR, Mathur AK, Volk ML. Variation among United States hospitals in inpatient mortality for cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;13:577–584. quiz e530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Mapakshi S, Kramer JR, Richardson P, El-Serag HB, Kanwal F. Positive predictive value of international classification of diseases, 10th revision, codes for cirrhosis and its related complications. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;16:1677–1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Nehra MS, Ma Y, Clark C, Amarasingham R, Rockey DC, Singal AG. Use of administrative claims data for identifying patients with cirrhosis. J Clin Gastroenterol 2013;47:e50–e54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Nguyen GC, Segev DL, Thuluvath PJ. Nationwide increase in hospitalizations and hepatitis C among inpatients with cirrhosis and sequelae of portal hypertension. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007;5:1092–1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Desai AP, Mohan P, Nokes B, Sheth D, Knapp S, Boustani M, et al. Increasing Economic burden in hospitalized patients with cirrhosis: analysis of a national database. Clin Transl Gastroenterol 2019;10:e00062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care 1998;36:8–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Myers RP, Quan H, Hubbard JN, Shaheen AA, Kaplan GG. Predicting in-hospital mortality in patients with cirrhosis: results differ across risk adjustment methods. Hepatology 2009;49:568–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Producing National HCUP Estimates [cited 2020 April 1]; Available at, Dec 13, 2018. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/tech_assist/nationalestimates/508_course/508course_2018.jsp#nis; December 13, 2018.

- [31].Pavkov ME, Harding JL, Burrows NR. Trends in hospitalizations for acute kidney injury - United States, 2000–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67:289–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Bajaj JS, Reddy KR, Tandon P, Wong F, Kamath PS, Garcia-Tsao G, et al. The 3-month readmission rate remains unacceptably high in a large North American cohort of patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology 2016;64:200–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Brown JR, Rezaee ME, Marshall EJ, Matheny ME. Hospital mortality in the United States following acute kidney injury. Biomed Res Int 2016;2016:4278579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Orman ES, Hayashi PH, Bataller R, Barritt AS. Paracentesis is associated with reduced mortality in patients hospitalized with cirrhosis and ascites. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;12:496–503.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Brown JR, Rezaee ME, Hisey WM, Cox KC, Matheny ME, Sarnak MJ. Reduced mortality associated with acute kidney injury requiring dialysis in the United States. Am J Nephrol 2016;43:261–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Zimmerman JE, Kramer AA, Knaus WA. Changes in hospital mortality for United States intensive care unit admissions from 1988 to 2012. Crit Care 2013;17:R81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Nicholas SB, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Norris KC. Socioeconomic disparities in chronic kidney disease. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 2015;22:6–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Neugarten J, Golestaneh L. Female sex reduces the risk of hospital-associated acute kidney injury: a meta-analysis. BMC Nephrol 2018;19:314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Grams ME, Sang Y, Ballew SH, Gansevoort RT, Kimm H, Kovesdy CP, et al. A meta-analysis of the association of estimated GFR, albuminuria, age, race, and sex with acute kidney injury. Am J Kidney Dis 2015;66: 591–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Pannu N, James M, Hemmelgarn BR, Dong J, Tonelli M, Klarenbach S, et al. Modification of outcomes after acute kidney injury by the presence of CKD. Am J Kidney Dis 2011;58:206–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Jencks SF, Williams DK, Kay TL. Assessing hospital-associated deaths from discharge data. The role of length of stay and comorbidities. JAMA 1988;260:2240–2246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Hughes JS, Iezzoni LI, Daley J, Greenberg L. How severity measures rate hospitalized patients. J Gen Intern Med 1996;11:303–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Rosenblatt R, Shen N, Tafesh Z, Cohen-Mekelburg S, Crawford CV, Kumar S, et al. The North American Consortium for the study of end-stage liver disease-acute-on-chronic liver failure score accurately predicts survival: an external validation using a national cohort. Liver Transpl 2020;26:187–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Hernaez R, Kramer JR, Liu Y, Tansel A, Natarajan Y, Hussain KB, et al. Prevalence and short-term mortality of acute-on-chronic liver failure: a national cohort study from the USA. J Hepatol 2019;70:639–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Thalheimer U, Triantos CK, Samonakis DN, Patch D, Burroughs AK. Infection, coagulation, and variceal bleeding in cirrhosis. Gut 2005;54:556–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Follo A, Llovet JM, Navasa M, Planas R, Forns X, Francitorra A, et al. Renal impairment after spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhosis: incidence, clinical course, predictive factors and prognosis. Hepatology 1994;20:1495–1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Utter GH, Cox GL, Atolagbe OO, Owens PL, Romano PS. Conversion of the agency for healthcare research and quality’s quality indicators from ICD-9-CM to ICD-10-CM/PCS: the process, results, and implications for users. Health Serv Res 2018;53:3704–3727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.