Abstract

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the leading causes of cancer death worldwide although its pathogenic mechanism remains to be fully understood. Unlike normal cells, most cancer cells rely on aerobic glycolysis and are more adaptable to the microenvironment of hypoxia and hypoglycemia. Bone Morphogenetic Protein 4 (BMP4) plays important roles in regulating proliferation, differentiation, invasion and migration of HCC cells. We have recently shown that BMP4 plays an important role in regulating glucose metabolism although the effect of BMP4 on glucose metabolic reprogramming of HCC is poorly understood. In this study, we found that BMP4 was highly expressed in HCC tumor tissues, as well as HCC cell lines that were tolerant to hypoxia and hypoglycemia. Mechanistically, we demonstrated that BMP4 protected HCC cells from hypoxia and hypoglycemia by promoting glycolysis since BMP4 up-regulated glucose uptake, the lactic acid production, the ATP level, and the activities of rate limiting enzymes of glycolysis (including HK2, PFK and PK). Furthermore, we demonstrated that BMP4 up-regulated HK2, PFKFB3 and PKM2 through the canonical Smad signal pathway as SMAD5 directly bound to the promoter of PKM. Collectively, our findings shown that BMP4 may play an important role in regulating glycolysis of HCC cells under hypoxia and hypoglycemia condition, indicating that novel therapeutics may be developed to target BMP4-regulated glucose metabolic reprogramming in HCC.

Keywords: BMP4, HCC, hypoxic and hypoglycemic, glycolysis, metabolic reprogramming, Smad signal pathway

Introduction

HCC is one of the leading causes of cancer death worldwide, and its incidence has been increasing in the last decade although its molecular pathogenesis remains to be fully understood [1]. Since the liver is an important organ of human in regulating glucose homeostasis and lipid metabolism, the changes of energy metabolism in liver cancer cells cannot been ignored [2,3]. One of the best characterized metabolic phenotypes observed in tumor cells is the phenomenon termed “the Warburg effect” [2,4,5]. In contrast to normal cells, which mainly rely on mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation to generate the energy, most cancer cells instead rely on aerobic glycolysis needed for cellular processes [2,5,6]. Rapidly growing tumors invariably contain hypoxic regions. Adaptive response to hypoxia through angiogenesis, enhanced glucose metabolism and diminished but optimized mitochondrial respiration provides survival and growth advantage to hypoxic tumor cells [7]. This abnormal glycolysis of tumor cells is thus usually accompanied with increased glucose uptake and lactic acid production, which is conducive to the occurrence and development of tumor [7].

Bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) belong to the transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) superfamily, and play important roles in regulating embryonic development, stem cell differentiation, and adult tissue homeostasis [8-13]. There are at least 14 types of BMPs in rodents and humans. BMP4 is highly expressed in the liver and plays multiple roles in the proliferation, invasion, migration and differentiation of HCC [14-17]. BMP4 preferentially binds to cytoplasm membrane receptor BMPR-II (type-II receptors), ALK-3 and/or ALK-6 (type-I receptors), and activates receptor-regulated Smads (R-Smads) Smad1, 5 and 8 located in the cytoplasm through phosphorylation activated by type-I receptors. The phosphorylated R-Smads interact with common-partner Smad (co-Smad) Smad4 to form Smad complex, which is then translocated into the nucleus to interact with specific transcription factors and regulate the expression of target genes [9,10,18]. Inhibitor Smad6 preferentially inhibits Smad signaling initiated by ALK-3 and ALK-6, whereas inhibitor Smad7 inhibits both TGF-β and Smad signaling [19]. It was shown that BMP4, among the 14 types of BMPs, played an important role in regulating glucose metabolism, and BMP4-BMPR1A signaling in β cells was required for and augmented glucose-stimulated insulin secretion [20]. It was reported that inhibition of BMP4 restored endothelial function in db/db diabetic mice [21]. Nonetheless, the direct impact of BMP4 on glucose metabolic reprogramming in HCC remains poorly understood.

In this study, we sought to investigate the effects and mechanism of BMP4 on HCC cell survival in the microenvironment of hypoxia and hypoglycemia from the view of glycolysis. We found that BMP4 was highly expressed in HCC tumor tissues, as well as HCC cell lines that were tolerant to hypoxia and hypoglycemia. Mechanistically, we demonstrated that BMP4 protected HCC cells from hypoxia and hypoglycemia by promoting glycolysis through a direct regulation of the rate limiting enzymes of glycolysis via the canonical Smad signal pathway. Thus, our findings strongly suggest that BMP4 may play an essential role in regulating glycolysis of HCC cells under hypoxia and hypoglycemia condition, indicating that novel therapeutics may be developed to target BMP4-regulated glucose metabolic reprogramming in HCC.

Materials and methods

The use of human/clinical samples

In this study, we isolated primary human hepatocytes from the surgically resected liver tissues from pediatric patients suffering from cholangiectasis, operated at the Children’s Hospital Affiliated to Chongqing Medical University. Furthermore, 40 cases of achieved HCC tissue blocks from the Department of Pathology of Chongqing Medical University were selected for immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis. The use of the clinical samples was approved by the Research Ethics and Regulations Committee of Chongqing Medical University, Chongqing, China.

Cell culture and chemicals

293pTP and RAPA cells were previously described [22,23]. Human HCC lines Hu7 and MHCC97H cells were provided by the Ministry of Education Key Laboratory of Diagnostic Medicine of Chongqing Medical University. Human primary hepatocytes (HPH) cells were isolated from the human liver tissues which surgically resected from the children with cholangiectasis. All cells were maintained in high glucose DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS (Lonsa Science SRL), 100 units of penicillin and 100 µg of streptomycin at 37°C in 5% CO2.

For the hypoxia and hypoglycemia culture conditions, cells were maintained in low glucose DMEM and hypoxia was chemically induced by cobalt chloride (100 μM CoCl2) as described [24,25]. All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA), Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA), or Solarbio (Beijing, China).

H&E and Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining

The paraffin sections of liver tumor tissue (T) and adjacent liver non-tumor tissue (ALNT) samples from 40 HCC patients were obtained from the Department of Pathology of Chongqing Medical University. H&E and IHC staining were conducted following the procedure as described [26-28]. The antibodies against BMP4 (1:200 dilution; Proteintech; Cat# 12492-1-AP), HK2 (1:200 dilution; Proteintech; Cat# 22029-1-AP), PFKFB3 (1:50 dilution; Bimake; Cat# A5593), PKM2 (1:50 dilution; Bimake; Cat# A5356), SMAD5 (1:50 dilution; Bimake; Cat# A5511) and p-SMAD5 phospho S463 + S465 (1:200 dilution; Abcam; Cat# ab92698). Control rabbit IgG (1:200; cat. no. 011-000-003; Jackson Immuno Research Laboratories, Inc.). The scoring standard and criteria of HCC tissue and adjacent liver non-tumor tissue samples for anti-BMP4 IHC were shown in Table S1 [29].

Construction and amplification of recombinant adenoviruses

Recombinant adenoviruses were generated by using the AdEasy technology [30]. The Ad-B4 that overexpresses human BMP4 was generated as described in previous studies [31,32]. Ad-siB4 that silence human Bmp4 was generated as described [33-37]. Three siRNA sites targeting human BMP4 were shown in Table S2. Adenoviral vector expresses RFP (Ad-RFP) or GFP (Ad-GFP) was used as a control [38,39].

Crystal violet cell viability assay

Crystal violet staining assay was conducted as described [40,41]. Briefly, cells were seeded into a 24-well plate at the density of 3×104/well and treated by different conditions. At the indicated time points, the cells were stained with 0.5% crystal violet/formalin solution. For quantitative measurement, the stained cells were dissolved in 10% acetic acid, followed by measuring absorbance at 592 nm.

WST-1 cell proliferation assay

WST-1 assay was conducted as described [40,41]. Briefly, cells were seeded into a 96-well plate at the density of 2000/well and treated by different conditions. At the indicated time points, the Premixed WST-1 Reagent (Clontech, Mountain View, CA) was added and incubated at 37°C for 120 min, followed by measuring absorbance at 450 nm.

Flow cytometry analysis of cell apoptosis

1×106 cells were treated with different conditions for 48 h and collected in 500 µl PBS. The collected cells were subjected to Annexin V-FITC and propidium iodide (PI) staining, or Annexin APC-A and DAPI staining. Followed by the cell flow screening and the apoptosis rates were calculated.

Biochemical index test of cells and tissues

The biochemical index were tested by using the Glucose Assay Kit (No. F006-1-1, Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute), the Lactic Acid assay kit (No. A019-2-1, Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute), the ATP assay kit (No. A095-1-1, Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute), the Hexokinase (HK) Assay Kit (No.BC0745, Solarbio), the Pyruvatekinase (PK) Assay Kit (No. BC0545, Solarbio) and the Phosphofructokinase (PFK) Assay Kit (No. BC0535, Solarbio).

Total RNA isolation and touchdown-quantitative real-time PCR (TqPCR) analysis

Total RNA was isolated by using the TRIZOL Reagent (Invitrogen, China) and subjected to reverse transcription into the cDNA products by using hexamer and M-MuLV reverse transcriptase (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA). TqPCR was carried out by using 2x SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix (Bimake, Shanghai, China) on the CFX-Connect unit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) as described [42]. TqPCR primers were shown in Table S3.

Western blotting analysis

Western blotting assay was carried out as previously described [39]. The primary antibodies against β-ACTIN (1:5000-1:20000 dilution; Proteintech; Cat# 60008-1-Ig), BMP4 (1:1000 dilution; Proteintech; Cat# 12492-1-AP), HK2 (1:2000 dilution; Proteintech; Cat# 22029-1-AP), PFKFB3 (1:1000 dilution; Bimake; Cat# A5593), PKM2 (1:1000 dilution; Bimake; Cat# A5356), SMAD5 (1:1000 dilution; Bimake; Cat# A5511), and p-SMAD5 (phospho S463 + S465; 1:1000 dilution; Abcam; Cat# ab92698), the secondary antibodies (1:5000 dilution; ZSGB-BIG; Peroxidase-Conjugated Rabbit anti-Goat IgG or Peroxidase-Conjugated Goat anti-Mouse IgG, Cat# ZB-2306 or 2305). Immune-reactive signals were visualized with the Enhanced Chemiluminescence (ECL) kit (Millipore, USA) and recorded by using the Bio-Rad ChemiDoc Imager (Hercules, CA). The blots were cropped and all original, full-length blot images were shown in Figure S3.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay

Consensus Smad1/Smad5 binding sites were previously characterized [43,44]. Numerous putative binding sites for Smad1/Smad5 were found in the promoter regions (e.g., within 2,000 bp upstream of exon 1) of human HK2, PFKM and PKM genes. ChIP assay was conducted to verify these potential binding sites as previously described [45]. Briefly, Hu7 cells were infected with Ad-B4 for 30 h, then cross-linked and subjected to ChIP analysis. Antibody for SMAD5 (1:20 dilution; Bimake; Cat# A5511) was used to pull down the protein-DNA complex. The goat IgG was used as a negative control. The presence of HK2, PFKM and PKM promoter fragments were detected with semi-quantitative PCR using multiple pairs of PCR primers, as listed in Table S4.

Subcutaneous and intrahepatic hepatoma cell implantation in athymic nude mice

The use and care of experimental animals was approved by the Research Ethics and Regulations Committee of Chongqing Medical University. All experimental procedures followed the approved guidelines. The cell implantation experiments were carried out as previously described [39,46]. Briefly, cells were treated with Ad-B4, Ad-siB4, Ad-GFP or Ad-RFP for 36 h, followed been injected into the flanks of athymic nude mice (5-week old, male, 5×106 cells/injection, 4 injections/mouse, 5 mice/group). At 14 days after injection, mice were sacrificed, the intrahepatic tumor masses were retrieved for biochemical indexes detection and IHC staining. Lung metastases nodules were retrieved for IHC staining.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed at least three times and/or repeated three batches of independent experiments. Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 7 and presented as the mean ± standard deviations (SD). Statistical significance was determined by one-way analysis of variance and the student’s t test for the comparisons between groups. A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

BMP4 is highly expressed in HCC and hepatoma cells tolerant to hypoxia and hypoglycemia

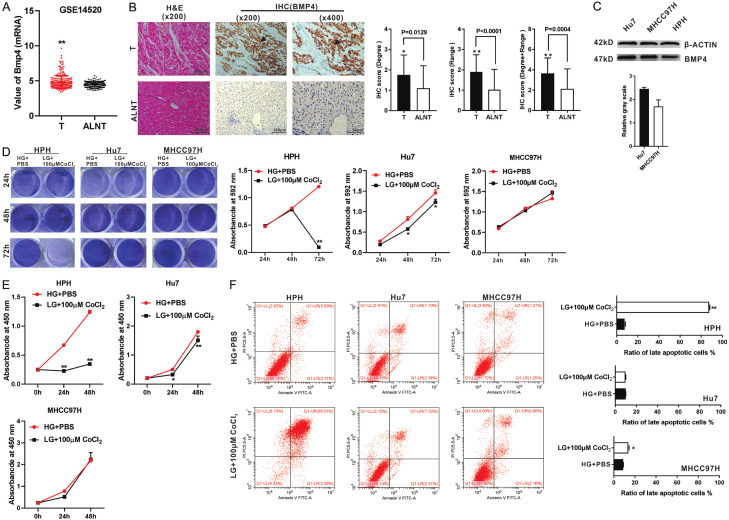

We first determined the expression of BMP4 in human HCC. By taking advantage of the GEO database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE14520), we found that the expression of BMP4 was markedly higher in HCC tumor tissues (T), compared with that in the adjacent liver non-tumor tissue (ALNT) (Figure 1A). We further evaluated the protein level of BMP4 in the HCC tumor (T) and ALNT regions in 40 HCC samples by IHC analysis, and found that the immunostaining for BMP4 was stronger and wider in the tumor regions than that in the ALNT regions (Figure 1B). As highly metastatic human HCC cell lines, Hu7 and MHCC97H cells have been shown to actively proliferate under the microenvironment of hypoxia and hypoglycemia [47,48]. We found that the expression of BMP4 was higher in Hu7 and MHCC97H cells than that in human primary hepatocyte (HPH) cells by Western blotting analysis (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

BMP4 is highly expressed in HCC tumor samples and HCC cells. A. BMP4 mRNA expression levels in 225 liver tumor tissues (T) and 220 adjacent liver non-tumor tissue (ALNT) in 225 surgical liver tumor cases (Data from GEO GSE14520). B. Paired HCC tumor samples (T) and ALNT samples from 40 patients were evaluated by H & E and IHC (BMP4) under a bright field microscope. Positive stainings were indicated by arrows. The scores of IHC were judged by degree or/and range of positive staining. “**” P < 0.01, “*” P < 0.05, “T” group vs. “ALNT” group. C. Levels of BMP4 protein expression in the Hu7, MHCC97H and HPH cells were assessed by Western blotting. The cropped blots were shown and Image Lab was used to quantitatively determine the densitometry of original blots. Relative gray scale was calculated by dividing the relative gray values (i.e., BMP4/β-ACTIN). D. Crystal violet staining. HPH, Hu7 and MHCC97H cells were cultured with low glucose (LG) DMED + 100 μM CoCl2, while the culture condition of high glucose (HG) DMED + equal volume PBS was set as a control. Crystal violet cell viability assay and quantitative analysis of crystal violet staining were conducted at 24 h, 48 h and 72 h. “**” P < 0.01, “*” P < 0.05, LG + 100 μM CoCl2 cultured group vs. HG + PBS cultured group. E. WST-1 assay. HPH, Hu7 and MHCC97H cells were cultured with LG DMED + 100 μM CoCl2, while the culture condition of HG DMED + equal volume PBS was set as a control. WST-1 was performed at 0 h, 24 h and 48 h. “**” P < 0.01, “*” P < 0.05, LG + 100 μM CoCl2 cultured group vs. HG + PBS cultured group. F. Flow cytometry analysis. HPH, Hu7 and MHCC97H cells were cultured with LG DMED + 100 μM CoCl2, while the culture condition of HG DMED + equal volume PBS was set as a control. Flow cytometry of cell apoptosis was tested and the ratio of late apoptotic cells (%) was calculated at 48 h. “**” P < 0.01, “*” P < 0.05, LG + 100 μM CoCl2 cultured group vs. HG + PBS cultured group.

We also determined the optimal concentration of CoCl2 for the chemical induction of hypoxia. As shown in Figure S1A, low glucose DMEM and 100 μM CoCl2 were optimal for simulating the hypoxia and hypoglycemia environment in cell culture. Using this culture condition, we validated the higher survival rate and proliferation rate of Hu7 and MHCC97H cells under hypoxia and hypoglycemia condition, compared with that in HPH cells by crystal violet cell viability assay (Figure 1D) and WST-1 cell proliferation assay (Figure 1E). Furthermore, much lower cell late apoptosis rates were found in Hu7 and MHCC97H cells, compared with that in HPH cells by flow cytometry analysis (Figure 1F). These results are supportive of the cell survival advantage of Hu7 and MHCC97H cells in hypoxia and hypoglycemia environment.

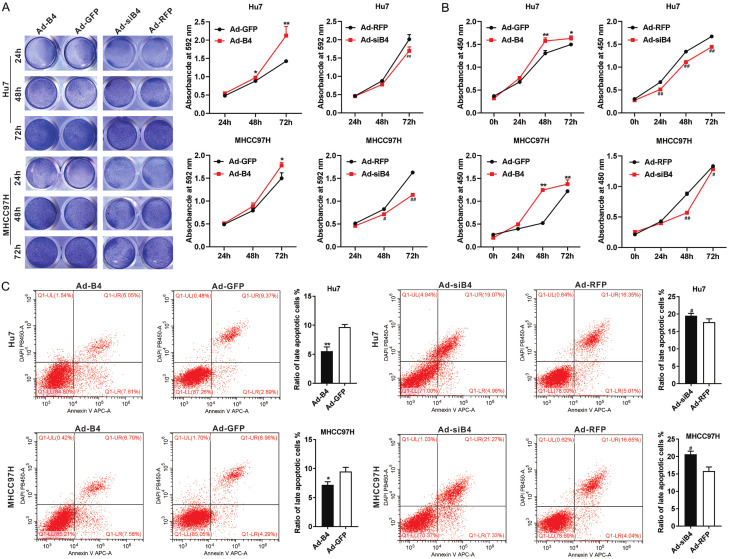

BMP4 protects HCC cells from hypoxia and hypoglycemia by promoting proliferation and inhibiting apoptosis

We engineered the recombinant adenoviruses Ad-B4 and Ad-siB4 to overexpress and silence BMP4 respectively. The level of BMP4 overexpression or silencing efficiency of BMP4 expression was firmly validated in Hu7 and MHCC97H cells (Figure S1B and S1C). When Hu7 and MHCC97H cells were cultured under hypoxia and hypoglycemia, and treated with Ad-B4 and Ad-siB4, respectively, crystal violet cell viability assay (Figure 2A) and WST-1 cell proliferation assay (Figure 2B) indicated that BMP4 promoted cell proliferation for both Hu7 and MHCC97H cells. Flow cytometry analysis revealed that BMP4 reduced cell late apoptosis rate of Hu7 and MHCC97H cells (Figure 2C). Thus, these results indicated that BMP4 could protect Hu7 and MHCC97H cells under hypoxia and hypoglycemia conditions.

Figure 2.

BMP4 promotes proliferation and inhibits apoptosis of HCC cells under hypoxia and hypoglycemia. A. Hu7 and MHCC97H cells were infected with Ad-B4, Ad-GFP, Ad-siB4 and Ad-RFP respectively, and cultured with low glucose (LG) DMED + 100 μM CoCl2, crystal violet cell viability assay and quantitative analysis of crystal violet staining were carried out at 24 h, 48 h and 72 h. “**” P < 0.01, “*” P < 0.05, Ad-B4 group vs. Ad-GFP group, “##” P < 0.01, “#” P < 0.05, Ad-siB4 group vs. Ad-RFP group. B. Hu7 and MHCC97H cells were infected with Ad-B4, Ad-GFP, Ad-siB4 and Ad-RFP respectively, and cultured with low glucose (LG) DMED + 100 μM CoCl2, WST-1 assay was done to at 0 h, 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h. “**” P < 0.01, “*” P < 0.05, Ad-B4 group vs. Ad-GFP group, “##” P < 0.01, “#” P < 0.05, Ad-siB4 group vs. Ad-RFP group. C. Hu7 and MHCC97H cells were infected with Ad-B4, Ad-GFP, Ad-siB4 and Ad-RFP respectively, and cultured with low glucose (LG) DMED + 100 μM CoCl2, flow cytometry analysis was conducted, and the ratio of late apoptotic cells (%) was calculated at 48 h. “**” P < 0.01, “*” P < 0.05, Ad-B4 group vs. Ad-GFP group, “#” P < 0.05, Ad-siB4 group vs. Ad-RFP group.

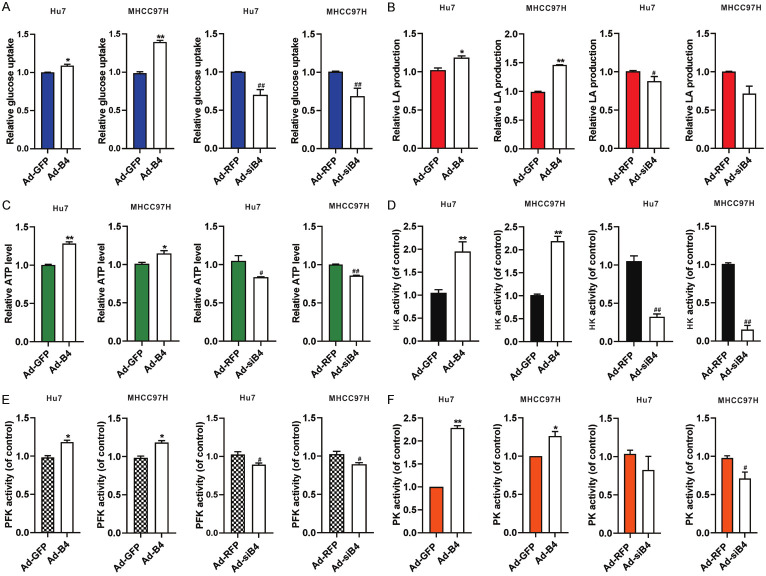

BMP4 promotes glycolysis of HCC cells under hypoxia and hypoglycemia

We next investigated the effect of BMP4 on glycolysis in HCC cells under hypoxia and hypoglycemia. Hu7 and MHCC97H cells were infected with Ad-B4 and Ad-siB4 respectively, under hypoxia and hypoglycemia. We found BMP4 promoted the glucose uptake (Figure 3A), LA (lactic acid) production (Figure 3B) and ATP level (Figure 3C) in the Hu7 and MHCC97H cells under hypoxia and hypoglycemia. We further tested the activities of rate limiting enzymes of glycolysis, and found that BMP4 also increased the activities of HK (Figure 3D), PFK (Figure 3E) and PK (Figure 3F). In sum, these results strongly suggest that BMP4 may promote glycolysis in Hu7 and MHCC97H cells to accommodate the demand of cellular energy consumption under hypoxia and hypoglycemia.

Figure 3.

BMP4 promotes glycolysis of HCC cells under hypoxia and hypoglycemia. Hu7 and MHCC97H cells were infected with Ad-B4, Ad-GFP, Ad-siB4 and Ad-RFP, respectively, and cultured with low glucose (LG) DMED + 100 μM CoCl2. The glucose uptake (A), LA (lactic acid) production (B), ATP level (C), activity of HK (D), activity of PFK (E) and activity of PK (F) were assessed at 48 h. “**” P < 0.01, “*” P < 0.05, Ad-B4 group vs. Ad-GFP group, “##” P < 0.01, “#” P < 0.05, Ad-siB4 group vs. Ad-RFP group.

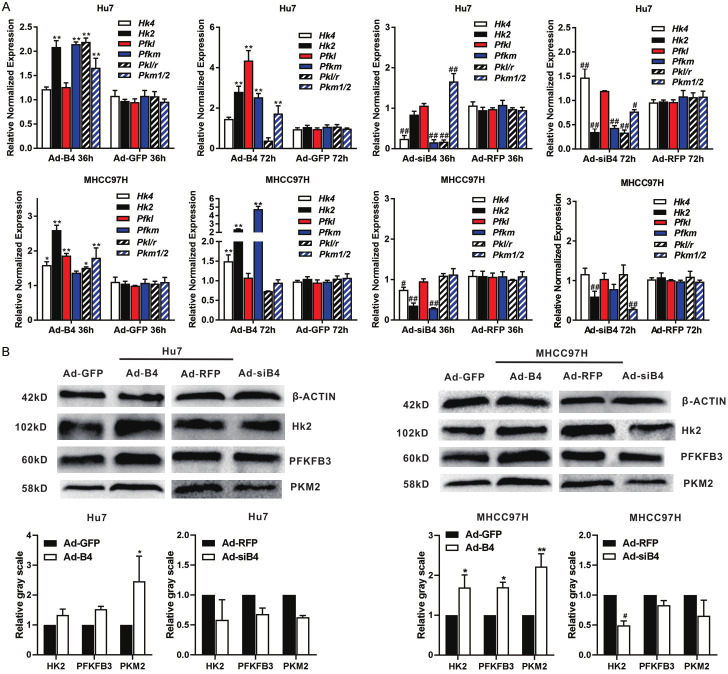

BMP4 up-regulates the expression of HK2, PFKFB3 and PKM2 through activating Smad signal pathway in HCC cells under hypoxia and hypoglycemia

To understand the possible mechanism underlying BMP4-regulated glycolysis, we first confirmed that the expression of HK2, PFKFB3 and PKM2 were much higher in the HCC tumor regions than that in the ALNT regions (Figure S1D). Then we found that BMP4 up-regulated the expression of HK2, PFK and PKM both at 36 h and 72 h in Hu7 and MHCC97H cells under hypoxia and hypoglycemia by using qPCR analysis (Figure 4A). Western blotting also shown that BMP4 up-regulated the protein levels of HK2, PFK and PKM in Hu7 and MHCC97H cells (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

BMP4 up-regulates the expression of glycolysis rate limiting enzymes in HCC cells under hypoxia and hypoglycemia. Hu7 and MHCC97H cells were infected with Ad-B4, Ad-GFP, Ad-siB4 and Ad-RFP, respectively, and cultured with low glucose (LG) DMED + 100 μM CoCl2. A. TqPCR analysis was carried out to detect the expression of glycolysis rate limiting enzymes at 36 h and 72 h. “**” P < 0.01, “*” P < 0.05, Ad-B4 group vs. Ad-GFP group, “##” P < 0.01, “#” P < 0.05, Ad-siB4 group vs. Ad-RFP group. B. Western blotting was used to assess the expression of HK2, PFKFB3 and PKM2 at 72 h. The cropped blots were shown and Image Lab was used to quantitatively determine the densitometry of original blots. Relative gray scale was calculated by dividing the relative gray values (i.e., HK2/ β-ACTIN) in “**” P < 0.01, “*” P < 0.05, Ad-B4 group vs. Ad-GFP group, “#” P < 0.05, Ad-siB4 group vs. Ad-RFP group.

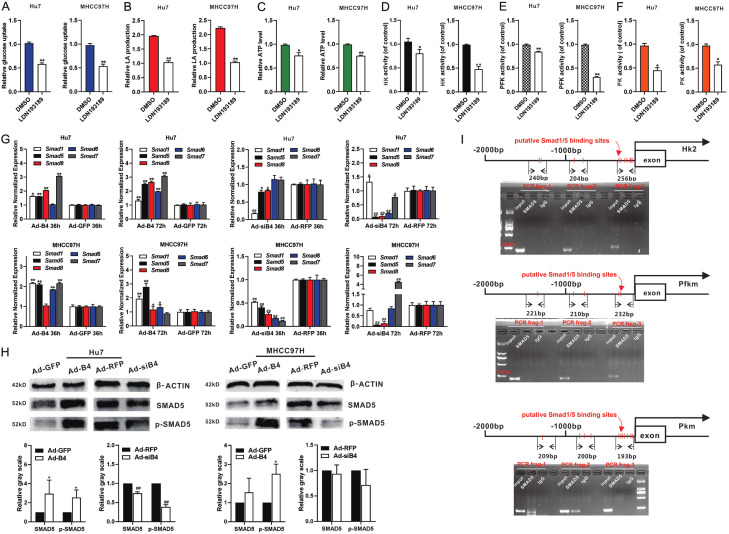

Conversely, we found that the BMP type I receptor inhibitor LDN193189 effectively blocked the BMP4-induced increase of glucose uptake (Figure 5A), LA (lactic acid) production (Figure 5B), ATP level (Figure 5C), activity of HK (Figure 5D), activity of PFK (Figure 5E) and activity of PK (Figure 5F) in Hu7 and MHCC97H cells under hypoxia and hypoglycemia. We found BMP4 up-regulated the expression of Smad1/5/8 and Smad6/7 in Hu7 and MHCC97H cells under hypoxia and hypoglycemia (Figure 5G). These results demonstrated that BMP4 induced the expression of HK2, PFKFB3 and PKM2 through activating Smad signal pathway in HCC cells under hypoxia and hypoglycemia.

Figure 5.

BMP4 up-regulates the expression of HK2, PFKFB3 and PKM2 through activating canonical BMP/SMAD signal pathway, and SMAD5 can directly bind to the promoter of PKM under hypoxia and hypoglycemia. Hu7 and MHCC97H cells were infected with Ad-B4 and LDN193189 under hypoxia and hypoglycemia. The glucose uptake (A), LA (lactic acid) production (B), ATP level (C), activity of HK (D), activity of PFK (E) and activity of PK (F) were measured at 48 h. “**” P < 0.01, “*” P < 0.05, LDN193189 group vs. DMSO group. (G) Hu7 and MHCC97H cells were infected with Ad-B4 and Ad-siB4 under hypoxia and hypoglycemia, TqPCR analysis was carried out to detect the expression of SMAD1, 5, 6, 7, 8 at 36 h and 72 h. “**” P < 0.01, “*” P < 0.05, Ad-B4 group vs. Ad-GFP group, “##” P < 0.01, “#” P < 0.05, Ad-siB4 group vs. Ad-RFP group. (H) Western blotting was used to detect the protein and phosphorylation level of SMAD5. The cropped blots were shown and Image Lab was used to quantitatively determine the densitometry of original blots. Relative gray scale was calculated by dividing the relative gray values (i.e., SMAD5/β-ACTIN) in “*” P < 0.05, Ad-B4 group vs. Ad-GFP group. “##” P < 0.01, Ad-siB4 group vs. Ad-RFP group. (I) For ChIP assay of Smad5, three pairs of PCR primers were designed to check the possible binding sites in the promoters of HK2, PFKM and PKM after Ad-B4 infection for 30 h in Hu7 cells with low glucose (LG) DMED + 100 μM CoCl2.

SMAD5 directly binds to the promoter of PKM in HCC cells under hypoxia and hypoglycemia

As SMAD1/5/8 function as important downstream transcription factors of BMP4 and regulate the expression of downstream genes, we demonstrated that BMP4 up-regulated the protein level and phosphorylation level of SMAD5 in the Hu7 and MHCC97H cells under hypoxia and hypoglycemia (Figure 5H). We performed ChIP analysis to determine whether Smad1/5 directly bound to the promoters of the rate-limiting glycolysis enzymes. Based on the reported consensus SMAD1/5 binding sites, we identified numerous putative binding sites in the 2kb promoter regions of HK2, PFKM and PKM. ChIP assay results shown that SMAD5 directly bound to the promoter region of PKM in the Hu7 cells under hypoxia and hypoglycemia (Figure 5I) although further in-depth analyses of SMAD binding ability to these genes’ promoter regions, including ChIP-seq and reporter assays, are warranted.

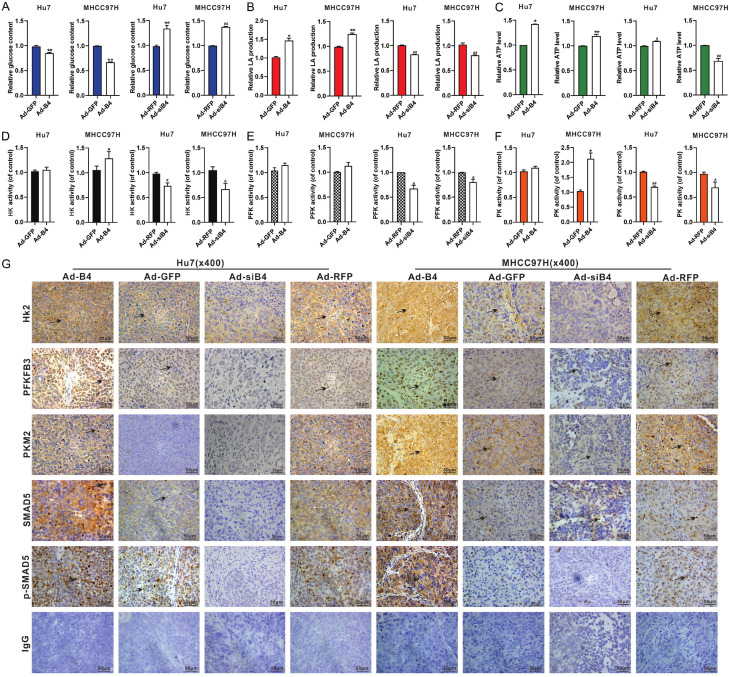

BMP4 promotes glycolysis of HCC cells in vivo

To further validate the impact of BMP4 on glucose metabolic reprogramming in HCC cells, Hu7 and MHCC97H cells infected with Ad-B4 or Ad-siB4 were injected intrahepatically and subcutaneous into athymic nude mice. And we found that in the freshly retrieved tumor samples BMP4 was shown to promote the glucose uptake (Figure 6A), LA (lactic acid) production (Figure 6B), ATP level (Figure 6C), HK activity (Figure 6D), PFK activity (Figure 6E) and the PK activity (Figure 6F). The retrieved tumor samples were subjected to IHC staining, and the expression of HK2, PFKFB3, PKM2, SMAD5 and p-SMAD5 were significantly up-regulated by BMP4, compared with that in the Ad-GFP control groups or the Ad-siB4 groups (Figure 6G). Furthermore, we found that the expression of PFKFB3, PKM2 in mouse lung Hu7 cells’ metastases, and the expression of HK2, PKM2 in mouse lung MHCC97H cells’ metastases were both increased by BMP4 (Figure S2).

Figure 6.

BMP4 promotes glycolysis of HCC cells in vivo. Hu7 and MHCC97H cells were infected with Ad-B4 and Ad-siB4, then injected intra-hepatically subcutaneously and into nude mice. The mice were sacrificed after 14 days. The retrieved tumor samples were subjected to assess the glucose content (A), LA (lactic acid) production (B), ATP level (C), activity of HK (D), activity of PFK (E) and activity of PK (F). “**” P < 0.01, “*” P < 0.05, Ad-B4 group vs. Ad-GFP group, “##” P < 0.01, “#” P < 0.05, Ad-siB4 group vs. Ad-RFP group. (G) The retrieved tumor samples were subjected to IHC staining to assess the expression of HK2, PFKFB3, PKM2, SMAD5 and p-SMAD5. Results were observed under a bright field microscope (×400), and positive staining were indicated by arrows. Representative results were shown.

Discussion

The mainly metabolic alternations in HCC include gluconeogenesis, elevated glycolysis, β-oxidation, and reduced of tricarboxylic acid cycle and Δ-12 desaturase by using a non-targeted metabolic profiling strategy [49]. Under aerobic condition, most normal cells metabolize glucose to carbon dioxide mainly through glycolysis and pyruvate oxidation in the mitochondrial tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle. This reaction produces NADH, which promotes oxidative phosphorylation to maximize ATP production and minimize lactic acid production. In contrast, most cancer cells produce large amounts of lactate regardless of the availability of oxygen, referred to as “aerobic glycolysis”. Thanks to the aerobic glycolysis of tumor cells, most tumor cells are relatively more tolerant to hypoxia and low glucose microenvironment [2,50]. In this study, we confirmed that the two aggressive HCC lines Hu7 and MHCC97H were tolerant to hypoxia and hypoglycemia.

Recent studies shown that BMP4 was highly expressed in liver among BMPs and play multiple effects on HCC. BMP4 enhanced HCC proliferation by promoting cell cycle via ID2/CDKN1B signaling, promoted metastasis of HCC by inducing EMT through up regulating ID2, provided cancer-supportive phenotypes to liver fibroblasts in patients with HCC, and increase proliferation and migration of HCC by active MEK/ERK signaling pathway [46,51-53]. However, BMP4 also induced differentiation of CD133+ hepatic cancer stem cells, blocked their contributions to HCC [54]. Here, we found BMP4 is highly expressed in HCC samples and the Hu7 and MHCC97H cells, and protects HCC cells from hypoxia and hypoglycemia by promotes proliferation and inhibits apoptosis. On the other hand, BMP4 plays an important role in the regulation of glucose metabolism. BMP4-BMPR1A signaling pathway in β cells is a necessary condition for regulating insulin secretion [20].

BMP4 can mediated brown fat-like changes into white adipose tissue to change the homeostasis of glucose and energy [55]. Nonetheless, the potential impact of BMP4 on glucose metabolic reprogramming HCC cells remains to be fully understood.

It is rather challenging to understand the precise mechanisms through which tumors adapt to hypoxia and hypoglycemia microenvironment. The structure and function of tumor vascular system are abnormal. In addition, the internal changes of tumor cell metabolism cause the creates spatial and temporal heterogeneity of oxygenation, pH value, glucose and many other metabolites [56]. In the process of tumorigenesis, the loss of tumor suppressor may lead to cell over metabolism and redox imbalance. It has been reported that NADPH is produced during the conversion of isocitric acid to α- ketoglutarate (αKG) catalyzed by isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1) and IDH2, and mutations in IDH1 and IDH2 are associated with tumorigenesis [57]. P53 can promote oxidative stress and induce apoptosis. Retinoblastoma (rb) normally participates in the antioxidant response. Myc not only promotes proliferation, but also promotes the production of accompanying macromolecules and antioxidants needed for growth and during the process of tumorigenesis. Loss of PTEN and overexpression of AKT1 resulted in FOXO inactivation and increased oxidative stress [58]. HIF1 amplification encodes gene transcription of glucose transporters and most glycolytic enzymes, increasing the ability of cells to carry out glycolysis. Loss of tumor suppressors may cause cells to become overloaded with the products of aberrant metabolism and redox imbalance [59-61]. In addition, mutations in oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes result in changes in many intracellular signaling pathways including PI3K pathway [62].

In our study, we found BMP4 promoted glycolysis of HCC cells under hypoxia and hypoglycemia, including increased the glucose uptake, lactic acid production and ATP level. The rate limiting enzymes of glycolysis play important role in liver cancer. HK2 mRNA expression was significantly higher in metastatic liver cancers [63]. HK2 is essential for glycolysis of HCC and HK2 depletion induces oxidative phosphorylation in [64]. Inhibited the expression of HK2 can reduce aerobic glycolysis and tumor growth in HCC [65]. Overexpression of PKM2 in tumor tissues is associated with poor prognosis in patients with HCC [66]. Inhibited the activity of PFK induced the apoptosis of HCC [67]. We further found BMP4 also increased the activities and expression of HK, PFK and PKM in Hu7 and HMCC97H cells under hypoxia and hypoglycemia.

BMP4 functions through binding to the receptors BMPR-II, ALK-3 and/or ALK-6, and activates Smad1, 5, 8 that interact with Smad4. The Smad complex is translocated into the nucleus, and interact with transcription factors to regulate the expression of downstream genes [68,69]. We found that BMP type I receptor inhibitor LDN193189 effectively blocked the effect of BMP4 on glycolysis and up-regulated expression of Smad1/5/8. ChIP assay results showed that SMAD5 directly bound to the promoter region of PKM in HCC cells.

In sum, we demonstrated that BMP4 protected HCC cells from hypoxia and hypoglycemia by promoting glycolysis through a direct regulation of the rate limiting enzymes of glycolysis via the canonical Smad signal pathway. Our findings suggest that BMP4 may play an important role in regulating glycolysis of HCC cells under hypoxia and hypoglycemia condition, indicating that novel therapeutics may be developed to target BMP4-regulated glucose metabolic reprogramming in HCC.

Acknowledgements

The reported study was supported in part by the 2019 Chongqing Support Program for Entrepreneurship and Innovation (Chongqing Human Resources and Social Security Bureau No.288) (JMF), the 2019 Science and Technology Research Plan Project of Chongqing Education Commission (KJQN201900410) (JMF), the 2019 Youth Innovative Talent Training Program of Chongqing Education Commission (CY200409) (JMF) and the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2016YFC1000803 and 2011CB707906).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

Authors’ contribution

Jiaming Fan and Tongchuan He: Conceived the project and oversaw the study, reviewed and approved the manuscript, provided the research funds; Jiamin Zhong: Performed most of the experiments in vitro and in vivo, collected and analysis data, original draft, wrote the manuscript; Piao Zhao and Yannian Gou: Performed part of the experiments in vitro; Yetao Luo: Data analysis and statistical analysis; Quan Kang, Youde Cao, and Baicheng He: Provided essential experimental supports and important research resources.

Abbreviations

- HCC

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- BMPs

Bone morphogenetic proteins

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- HPH

Human primary hepatocytes

- T

tumor tissue

- ALNT

Adjacent liver non-tumor tissue

- Ad-B4

Adenoviral vector expressing human BMP4

- Ad-GFP

Adenoviral vector expressing the green fluorescent protein (GFP)

- Ad-siB4

Adenoviral vector expressing three siRNAs that silence human Bmp4

- Ad-RFP

Adenoviral vector expressing the red fluorescent protein (RFP)

- H & E

hematoxylin and eosin

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- TqPCR

touchdown quantitative real-time PCR

- HK2

hexokinase 2

- PKM

pyruvate kinase M1/2

- PFK

Phosphofructokinase

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Ai-Wu S, Yuan-Sheng C, Li LIJG. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterologist. 2016;20:703–720. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC, Thompson CB. Understanding the warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science. 2009;324:1029–1033. doi: 10.1126/science.1160809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bechmann LP, Hannivoort RA, Gerken G, Hotamisligil GS, Trauner M, Canbay A. The interaction of hepatic lipid and glucose metabolism in liver diseases. J Hepatol. 2012;56:952–964. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cairns RA, Harris IS, Mak TW. Regulation of cancer cell metabolism. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2011;11:85–95. doi: 10.1038/nrc2981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pavlova NN, Thompson CB. The emerging hallmarks of cancer metabolism. Cell Metab. 2016;23:27–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vander Heiden MG, DeBerardinis RJ. Understanding the intersections between metabolism and cancer biology. Cell. 2017;168:657–669. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.12.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Semenza GL. Targeting HIF-1 for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:721–732. doi: 10.1038/nrc1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Derynck R, Zhang YE. Smad-dependent and Smad-independent pathways in TGF-beta family signalling. Nature. 2003;425:577–584. doi: 10.1038/nature02006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luu HH, Song WX, Luo X, Manning D, Luo J, Deng ZL, Sharff KA, Montag AG, Haydon RC, He TC. Distinct roles of bone morphogenetic proteins in osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. J Orthop Res. 2007;25:665–677. doi: 10.1002/jor.20359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang RN, Green J, Wang Z, Deng Y, Qiao M, Peabody M, Zhang Q, Ye J, Yan Z, Denduluri S, Idowu O, Li M, Shen C, Hu A, Haydon RC, Kang R, Mok J, Lee MJ, Luu HL, Shi LL. Bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling in development and human diseases. Genes Dis. 2014;1:87–105. doi: 10.1016/j.gendis.2014.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weiss A, Attisano L. The TGFbeta superfamily signaling pathway. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Dev Biol. 2013;2:47–63. doi: 10.1002/wdev.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salazar VS, Gamer LW, Rosen V. BMP signalling in skeletal development, disease and repair. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2016;12:203–221. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2016.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shimasaki S, Moore RK, Otsuka F, Erickson GF. The bone morphogenetic protein system in mammalian reproduction. Endocr Rev. 2004;25:72–101. doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ma J, Zeng S, Zhang Y, Deng G, Qu Y, Guo C, Yin L, Han Y, Shen H. BMP4 enhances hepatocellular carcinoma proliferation by promoting cell cycle progression via ID2/CDKN1B signaling. Mol Carcinog. 2017;56:2279–2289. doi: 10.1002/mc.22681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ma J, Zeng S, Zhang Y, Deng G, Qu Y, Guo C, Yin L, Han Y, Cai C, Li Y, Wang G, Bonkovsky HL, Shen H. BMP4 promotes oxaliplatin resistance by an induction of epithelial-mesenchymal transition via MEK1/ERK/ELK1 signaling in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2017;411:117–129. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2017.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li X, Gao L, Zheng L, Shi J, Ma J. BMP4-mediated autophagy is involved in the metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma via JNK/Beclin1 signaling. Am J Transl Res. 2020;12:3068–3077. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li X, Sun B, Zhao X, An J, Zhang Y, Gu Q, Zhao N, Wang Y, Liu F. Function of BMP4 in the formation of vasculogenic mimicry in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cancer. 2020;11:2560–2571. doi: 10.7150/jca.40558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mostafa S, Pakvasa M, Coalson E, Zhu A, Alverdy A, Castillo H, Fan J, Li A, Feng Y, Wu D, Bishop E, Du S, Spezia M, Li A, Hagag O, Deng A, Liu W, Li M, Ho SS, Athiviraham A, Lee MJ, Wolf JM, Ameer GA, Luu HH, Haydon RC, Strelzow J, Hynes K, He TC, Reid RR. The wonders of BMP9: from mesenchymal stem cell differentiation, angiogenesis, neurogenesis, tumorigenesis, and metabolism to regenerative medicine. Genes Dis. 2019;6:201–223. doi: 10.1016/j.gendis.2019.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miyazawa K, Miyazono K. Regulation of TGF-β family signaling by inhibitory smads. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2017;9:a022095. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a022095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goulley J, Dahl U, Baeza N, Mishina Y, Edlund H. BMP4-BMPR1A signaling in beta cells is required for and augments glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. Cell Metabolism. 2007;5:207–219. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang Y, Liu J, Tian XY, Wong WT, Huang Y. Inhibition of bone morphogenic protein 4 restores endothelial function in db/db diabetic mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34:152–159. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.302696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wei Q, Fan J, Liao J, Zou Y, Song D, Liu J, Cui J, Liu F, Ma C, Hu X, Li L, Yu Y, Qu X, Chen L, Yu X, Zhang Z, Zhao C, Zeng Z, Zhang R, Yan S, Wu X, Shu Y, Reid RR, Lee MJ, Wolf JM, He TC. Engineering the rapid adenovirus production and amplification (RAPA) cell line to expedite the generation of recombinant adenoviruses. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2017;41:2383–2398. doi: 10.1159/000475909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu N, Zhang H, Deng F, Li R, Zhang W, Chen X, Wen S, Wang N, Zhang J, Yin L, Liao Z, Zhang Z, Zhang Q, Yan Z, Liu W, Wu D, Ye J, Deng Y, Yang K, Luu HH, Haydon RC, He TC. Overexpression of Ad5 precursor terminal protein accelerates recombinant adenovirus packaging and amplification in HEK-293 packaging cells. Gene Ther. 2014;21:629–637. doi: 10.1038/gt.2014.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Piret JP, Mottet D, Raes M, Michiels C. CoCl2, a chemical inducer of hypoxia-inducible factor-1, and hypoxia reduce apoptotic cell death in hepatoma cell line HepG2. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;973:443–447. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04680.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Piret JP, Lecocq C, Toffoli S, Ninane N, Raes M, Michiels C. Hypoxia and CoCl2 protect HepG2 cells against serum deprivation- and t-BHP-induced apoptosis: a possible anti-apoptotic role for HIF-1. Exp Cell Res. 2004;295:340–349. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fan J, Wei Q, Liao J, Zou Y, Song D, Xiong D, Ma C, Hu X, Qu X, Chen L, Li L, Yu Y, Yu X, Zhang Z, Zhao C, Zeng Z, Zhang R, Yan S, Wu T, Wu X, Shu Y, Lei J, Li Y, Zhang W, Haydon RC, Luu HH, Huang A, He TC, Tang H. Noncanonical Wnt signaling plays an important role in modulating canonical Wnt-regulated stemness, proliferation and terminal differentiation of hepatic progenitors. Oncotarget. 2017;8:27105–27119. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang E, Bi Y, Jiang W, Luo X, Yang K, Gao JL, Gao Y, Luo Q, Shi Q, Kim SH, Liu X, Li M, Hu N, Liu H, Cui J, Zhang W, Li R, Chen X, Shen J, Kong Y, Zhang J, Wang J, Luo J, He BC, Wang H, Reid RR, Luu HH, Haydon RC, Yang L, He TC. Conditionally immortalized mouse embryonic fibroblasts retain proliferative activity without compromising multipotent differentiation potential. PLoS One. 2012;7:e32428. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cui J, Zhang W, Huang E, Wang J, Liao J, Li R, Yu X, Zhao C, Zeng Z, Shu Y, Zhang R, Yan S, Lei J, Yang C, Wu K, Wu Y, Huang S, Ji X, Li A, Gong C, Yuan C, Zhang L, Liu W, Huang B, Feng Y, An L, Zhang B, Dai Z, Shen Y, Luo W, Wang X, Huang A, Luu HH, Reid RR, Wolf JM, Thinakaran G, Lee MJ, He TC. BMP9-induced osteoblastic differentiation requires functional Notch signaling in mesenchymal stem cells. Lab Invest. 2019;99:58–71. doi: 10.1038/s41374-018-0087-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xian J, Cheng Y, Qin X, Cao Y, Luo Y, Cao Y. Progress in the research of p53 tumour suppressor activity controlled by Numb in triple-negative breast cancer. J Cell Mol Med. 2020;24:7451–7459. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.15366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luo J, Deng ZL, Luo X, Tang N, Song WX, Chen J, Sharff KA, Luu HH, Haydon RC, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, He TC. A protocol for rapid generation of recombinant adenoviruses using the AdEasy system. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:1236–1247. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peng Q, Chen B, Wang H, Zhu Y, Fan J. Bone morphogenetic protein 4 (BMP4) alleviates hepatic steatosis by increasing hepatic lipid turnover and inhibiting the mTORC1 signaling axis in hepatocytes. Aging. 2019;11:11520–11540. doi: 10.18632/aging.102552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kang Q, Song WX, Luo Q, Tang N, Luo J, Luo X, Chen J, Bi Y, He BC, Park JK, Jiang W, Tang Y, Huang J, Su Y, Zhu GH, He Y, Yin H, Hu Z, Wang Y, Chen L, Zuo GW, Pan X, Shen J, Vokes T, Reid RR, Haydon RC, Luu HH, He TC. A comprehensive analysis of the dual roles of BMPs in regulating adipogenic and osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal progenitor cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2009;18:545–559. doi: 10.1089/scd.2008.0130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luo Q, Kang Q, Song WX, Luu HH, Luo X, An N, Luo J, Deng ZL, Jiang W, Yin H, Chen J, Sharff KA, Tang N, Bennett E, Haydon RC, He TC. Selection and validation of optimal siRNA target sites for RNAi-mediated gene silencing. Gene. 2007;395:160–169. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2007.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deng F, Chen X, Liao Z, Yan Z, Wang Z, Deng Y, Zhang Q, Zhang Z, Ye J, Qiao M, Li R, Denduluri S, Wang J, Wei Q, Li M, Geng N, Zhao L, Zhou G, Zhang P, Luu HH, Haydon RC, Reid RR, Yang T, He TC. A simplified and versatile system for the simultaneous expression of multiple siRNAs in mammalian cells using Gibson DNA assembly. PLoS One. 2014;9:e113064. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shu Y, Wu K, Zeng Z, Huang S, Ji X, Yuan C, Zhang L, Liu W, Huang B, Feng Y, Zhang B, Dai Z, Shen Y, Luo W, Wang X, Liu B, Lei Y, Ye Z, Zhao L, Cao D, Yang L, Chen X, Luu HH, Reid RR, Wolf JM, Lee MJ, He TC. A simplified system to express circularized inhibitors of miRNA for stable and potent suppression of miRNA functions. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2018;13:556–567. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2018.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fan J, Feng Y, Zhang R, Zhang W, Shu Y, Zeng Z, Huang S, Zhang L, Huang B, Wu D, Zhang B, Wang X, Lei Y, Ye Z, Zhao L, Cao D, Yang L, Chen X, Liu B, Wagstaff W, He F, Wu X, Zhang J, Moriatis Wolf J, Lee MJ, Haydon RC, Luu HH, Huang A, He TC, Yan S. A simplified system for the effective expression and delivery of functional mature microRNAs in mammalian cells. Cancer Gene Ther. 2020;27:424–437. doi: 10.1038/s41417-019-0113-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang X, Yuan C, Huang B, Fan J, Feng Y, Li AJ, Zhang B, Lei Y, Ye Z, Zhao L, Cao D, Yang L, Wu D, Chen X, Liu B, Wagstaff W, He F, Wu X, Luo H, Zhang J, Zhang M, Haydon RC, Luu HH, Lee MJ, Moriatis Wolf J, Huang A, He TC, Zeng Z. Developing a versatile shotgun cloning strategy for single-vector-based multiplex expression of short interfering RNAs (siRNAs) in mammalian cells. ACS Synth Biol. 2019;8:2092–2105. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.9b00203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yu X, Chen L, Wu K, Yan S, Zhang R, Zhao C, Zeng Z, Shu Y, Huang S, Lei J, Ji X, Yuan C, Zhang L, Feng Y, Liu W, Huang B, Zhang B, Luo W, Wang X, Liu B, Haydon RC, Luu HH, He TC, Gan H. Establishment and functional characterization of the reversibly immortalized mouse glomerular podocytes (imPODs) Genes Dis. 2018;5:137–149. doi: 10.1016/j.gendis.2018.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang H, Cao Y, Shu L, Zhu Y, Peng Q, Ran L, Wu J, Luo Y, Zuo G, Luo J, Zhou L, Shi Q, Weng Y, Huang A, He TC, Fan J. Long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) H19 induces hepatic steatosis through activating MLXIPL and mTORC1 networks in hepatocytes. J Cell Mol Med. 2020;24:1399–1412. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.14818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang F, Li Y, Zhang H, Huang E, Gao L, Luo W, Wei Q, Fan J, Song D, Liao J, Zou Y, Liu F, Liu J, Huang J, Guo D, Ma C, Hu X, Li L, Qu X, Chen L, Yu X, Zhang Z, Wu T, Luu HH, Haydon RC, Song J, He TC, Ji P. Anthelmintic mebendazole enhances cisplatin’s effect on suppressing cell proliferation and promotes differentiation of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) Oncotarget. 2017;8:12968–12982. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Deng Y, Wang Z, Zhang F, Qiao M, Yan Z, Wei Q, Wang J, Liu H, Fan J, Zou Y, Liao J, Hu X, Chen L, Yu X, Haydon RC, Luu HH, Qi H, He TC, Zhang J. A Blockade of IGF signaling sensitizes human ovarian cancer cells to the anthelmintic niclosamide-induced anti-proliferative and anticancer activities. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2016;39:871–888. doi: 10.1159/000447797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang Q, Wang J, Deng F, Yan Z, Xia Y, Wang Z, Ye J, Deng Y, Zhang Z, Qiao M, Li R, Denduluri SK, Wei Q, Zhao L, Lu S, Wang X, Tang S, Liu H, Luu HH, Haydon RC, He TC, Jiang L. TqPCR: a touchdown qPCR assay with significantly improved detection sensitivity and amplification efficiency of SYBR green qPCR. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0132666. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martin-Malpartida P, Batet M, Kaczmarska Z, Freier R, Macias MJ. Structural basis for genome wide recognition of 5-bp GC motifs by SMAD transcription factors. Nat Commun. 2017;8:2070. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02054-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Masato M, Daizo K, Shuichi T, Eleftheria V, Yasuharu K, Carl-Henrik H, Hiroyuki A, Kohei M. ChIP-seq reveals cell type-specific binding patterns of BMP-specific Smads and a novel binding motif. Nucleic Acids Research. 2011;39:8712–8727. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang H, Hu Y, He F, Li L, Li PP, Deng Y, Li FS, Wu K, He BC. All-trans retinoic acid and COX-2 cross-talk to regulate BMP9-induced osteogenic differentiation via Wnt/β-catenin in mesenchymal stem cells. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019;118:109279. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.109279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ma J, Zeng S, Zhang Y, Deng G, Qu Y, Guo C, Yin L, Han Y, Shen H. BMP4 enhances hepatocellular carcinoma proliferation by promoting cell cycle progression via ID2/CDKN1B signaling. Mol Carcinog. 2017;56:2279–2289. doi: 10.1002/mc.22681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang MH, Chen CL, Chau GY, Chiou SH, Su CW, Chou TY, Peng WL, Wu JC. Comprehensive analysis of the independent effect of twist and snail in promoting metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2009;50:1464–1474. doi: 10.1002/hep.23221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yuan R, Wang K, Hu J, Yan C, Shao J. Ubiquitin-like protein FAT10 promotes the invasion and metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma by modifying β-catenin degradation. Cancer Res. 2014;74:5287. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang Q, Tan Y, Yin P, Ye G, Gao P, Lu X, Wang H, Xu G. Metabolic characterization of hepatocellular carcinoma using nontargeted tissue metabolomics. Cancer Res. 2013;73:4992–5002. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-0308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Koppenol WH, Bounds PL, Dang CV. Otto Warburg’s contributions to current concepts of cancer metabolism. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:325–337. doi: 10.1038/nrc3038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chiu CY, Kuo KK, Kuo TL, Lee KT, Cheng KH. The activation of MEK/ERK signaling pathway by bone morphogenetic protein 4 to increase hepatocellular carcinoma cell proliferation and migration. Mol Cancer Res. 2012;10:415–427. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-11-0293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zeng S, Zhang Y, Ma J, Deng G, Qu Y, Guo C, Han Y, Yin L, Cai C, Li Y. BMP4 promotes metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma by an induction of epithelial-mesenchymal transition via upregulating ID2. Cancer Lett. 2017;390:67–76. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mano Y, Yoshio S, Shoji H, Tomonari S, Aoki Y, Aoyanagi N, Okamoto T, Matsuura Y, Osawa Y, Kimura K. Bone morphogenetic protein 4 provides cancer-supportive phenotypes to liver fibroblasts in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol. 2019;54:1007–1018. doi: 10.1007/s00535-019-01579-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang L, Sun H, Zhao F, Lu P, Ge C, Li H, Hou H, Yan M, Chen T, Jiang G. BMP4 administration induces differentiation of CD133+ hepatic cancer stem cells, blocking their contributions to hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2012;72:4276–4285. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Qian SW, Tang Y, Li X, Liu Y, Zhang YY, Huang HY, Xue RD, Yu HY, Guo L, Gao HD, Liu Y, Sun X, Li YM, Jia WP, Tang QQ. BMP4-mediated brown fat-like changes in white adipose tissue alter glucose and energy homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:E798–807. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215236110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schornack PA, Gillies RJ. Contributions of cell metabolism and H+ diffusion to the acidic pH of tumors. Neoplasia. 2003;5:135–145. doi: 10.1016/s1476-5586(03)80005-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Atai NA, Renkema-Mills NA, Bosman J, Schmidt N, Rijkeboer D, Tigchelaar W, Bosch KS, Troost D, Jonker A, Bleeker FE. Differential activity of NADPH-producing dehydrogenases renders rodents unsuitable models to study IDH1R132 mutation effects in human glioblastoma. J Histochem Cytochem. 2011;59:489–503. doi: 10.1369/0022155411400606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chang CJ, Mulholland DJ, Valamehr B, Mosessian S, Sellers WR, Wu H. PTEN nuclear localization is regulated by oxidative stress and mediates p53-dependent tumor suppression. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:3281–3289. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00310-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hosako M, Ogino T, Okada S. Cell cycle arrest by physiological oxidant through the oxidation of retinoblastoma protein. Cell Struct Funct. 2005;30:29–29. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Maddocks OD, Berkers CR, Mason SM, Zheng L, Blyth K, Gottlieb E, Vousden KH. Serine starvation induces stress and p53-dependent metabolic remodelling in cancer cells. Nature. 2013;493:542–546. doi: 10.1038/nature11743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.K CS, Cárcamo JM, Golde DW. Antioxidants prevent oxidative DNA damage and cellular transformation elicited by the over-expression of c-MYC. Mutat Res. 2006;593:64–79. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2005.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bell HS, Ryan KM. Intracellular signalling and cancer: complex pathways lead to multiple targets. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:206–215. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yasuda S, Arii S, Mori A, Isobe N, Imamura M. Hexokinase II and VEGF expression in liver tumors: correlation with hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha and its significance. J Hepatol. 2004;40:117–123. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(03)00503-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dewaal D, Nogueira V, Terry AR, Patra KC, Jeon SM, Guzman G, Au J, Long CP, Antoniewicz MR, Hay N. Hexokinase-2 depletion inhibits glycolysis and induces oxidative phosphorylation in hepatocellular carcinoma and sensitizes to metformin. Nat Commun. 2018;9:2539. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04182-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dai W, Wang F, Lu J, Xia Y, Guo C. By reducing hexokinase 2, resveratrol induces apoptosis in HCC cells addicted to aerobic glycolysis and inhibits tumor growth in mice. Oncotarget. 2015;6:13703–13717. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhao R, Li L, Yang J, Niu Q, Wang H, Qin X, Zhu N, Shi A. Overexpression of pyruvate kinase M2 in tumor tissues is associated with poor prognosis in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Pathol Oncol Res. 2020;26:853–860. doi: 10.1007/s12253-019-00630-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Li S, Wu L, Feng J, Li J, Liu T, Zhang R, Xu S, Cheng K, Zhou Y, Zhou S. In vitro and in vivo study of epigallocatechin-3-gallate-induced apoptosis in aerobic glycolytic hepatocellular carcinoma cells involving inhibition of phosphofructokinase activity. Sci Rep. 2016;6:28479. doi: 10.1038/srep28479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang RN, Green J, Wang Z, Deng Y, Qiao M, Peabody M, Zhang Q, Ye J, Yan Z, Denduluri S, Idowu O, Li M, Shen C, Hu A, Haydon RC, Kang R, Mok J, Lee MJ, Luu HL, Shi LL. Bone Morphogenetic Protein (BMP) signaling in development and human diseases. Genes Dis. 2014;1:87–105. doi: 10.1016/j.gendis.2014.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bragdon B, Moseychuk O, Saldanha S, King D, Julian J, Nohe A. Bone morphogenetic proteins: a critical review. Cell Signal. 2011;23:609–620. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.