Abstract

Palm oil production chain generates a greasy residue in the refining stage, the Palm Oil Deodorizer Distillate (PODD), mainly composed of free fatty acids. Palm oil is also used industrially to fry foods, generating a residual frying oil (RFO). In this paper, we aimed to produce lipase from palm agro-industrial wastes using an unconventional yeast. RFO_palm, from a known source, consisted of 0.11% MAG + FFA, 1.5% DAG, and 97.5 TAG, while RFO_commercial, from a commercial restaurant, contained 6.7% of DAG and 93.3% of TAG. All palm oil wastes were useful for extracellular lipase production, especially RFO_commercial that provided the highest activity (4.9 U/mL) and productivity (465 U/L.h) in 75 h of processing time. In 48 h of process, PODD presented 2.3 U/mL of lipase activity and 48.5 U/L.h of productivity. RFO_commercial also showed the highest values for lipase associated to cell debris (843 U/g). This naturally immobilized biocatalyst was tested on hydrolysis reactions to produce Lipolyzed Milk Fat and was quite efficient, with a hydrolysis yield of 13.1% and 3-cycle reuse. Therefore, oily palm residues seem a promising alternative to produce lipases by the non-pathogenic yeast Y. lipolytica and show great potential for industrial applications.

Keywords: Palm oil deodorizer distillate, Residual frying oil, Lipase, Natural immobilization, Cell debris, Waste valorization

Introduction

Palm tree is native in tropical forests in west and central Africa, but it speedily expanded in southeast Asia countries such as Malaysia and Indonesia, which are the major palm oil producers nowadays – almost 85% of the world’s production. Palm oil (Elaeis guineensis Jacq.) is extracted from the plant’s fruit mesocarp and it is mainly used in edible products, contributing to 30% of the world’s vegetable oil (Wahid et al. 2005; Sheil et al. 2009; Carter et al. 2007). Triacylglycerols (TAG) from palm oil are mainly composed of palmitic acid, followed by oleic, linoleic and stearic acids. Monoacylglycerols (MAG), diacylglycerols (DAG), carotenoids, tocopherols, sterols, phosphatides, triterpenic and aliphatic alcohols are minor constituents of palm oil that contribute to the stability of the oil and its nutritive value (Lai et al. 2020). The palm oil for cooking is obtained after refining processes that remove impurities to enable it for human consumption, eliminating free fatty acids (FFA) and other minor constituents, which may compromise the desired organoleptic characteristics (Gibon et al. 2007). The refining processes generates by-products such as soapstocks, deodorizer distillates, acid oil water, MAG, and DAG (Dumont et al. 2007).

Palm oil deodorizer distillate (PODD) is a by-product from the refining process of palm oil, generated in the physical refining route of the deodorization path (Echin et al. 2016). PODD is a light brown greasy residue composed mainly by free fatty acids, with palmitic acid as major compound, followed by oleic acid and linoleic acid. Other components present in PODD include tocopherols and tocotrienols, phytosterols and squalene, which are the unsaponifiable matter (Gibon et al. 2007; Aguieiras et al. 2017; Tan et al. 2007). Generally, 3–10% of PODD is derived from crude palm oil (CPO), and its commercial value is lower than the CPO and also the refined, bleached and deodorized palm oil (Raita et al. 2011; Malaysian Palm Oil Board 2019). Palm oil is also used commercially to fry foods and its residual frying oil (RFO) is broadly reused due to its high oxidative stability. The procedure of frying initiates the thermal oxidative deterioration, polymerization and hydrolysis of unsaturated fat acids (FA). RFO is constituted by TAG – the greater compound -, DAG, MAG and glycerol, besides a small amount of FFA (Choe and Min 2007; Mba et al. 2015).

Due to its high fatty acid content and the increasing need to provide alternative destinations to industrial wastes, PODD can be used as feedstock in several reactions to generate bioproducts. Valorizing palm oil refining by-products creates business opportunities for stakeholders and reinforces the relevance of sustainable development (Tan et al. 2007). PODD was applied to substitute more expensive refined oils in many industries and was considered a promising alternative in biofuel production by virtue of a successful methyl esters production (Outoye et al. 2014; Gupta and Rathod 2014). Another application of PODD is MAG and DAG production by esterification reactions using lipases and glycerol. These FFA can contribute to the emulsification of food products (Collaço et al. 2020). PODD was also converted into polyol esters with biolubricant properties using enzymes and desirable viscosity values and high oxidative stability were obtained (Fernandes et al. 2018). Lipase was applied to obtain wax esters via esterification reactions using PODD as FFA source, resulting in a bio-based wax with similar applications to natural waxes (Aguieiras et al. 2019).

RFO is also a rich carbon source, hence a variety of bioproducts can be obtained with this residue as feedstock. Biosurfactants were produced from RFO by filamentous bacteria isolated from lichens of Amazon region, showing no toxicity and great potential to reduce surface tension (Santos et al. 2018). A lipase produced with RFO as inducer was successfully applied to obtain lipolyzed milk fat, a vehicle for cheese flavors (Fraga et al. 2018). RFO was also efficiently used to produce biodiesel via transesterification reaction with heterogenous catalyst in mild conditions (Rehab et al. 2020).

Lipases are triacylglycerol hydrolases (E.C. 3.1.1.3) which catalyze hydrolysis of esters bonds in TAG, DAG and MAG, releasing glycerol, FFA, MAG and DAG as products. In absence or in low moisture content, this enzyme can synthesize TAG, DAG and MAG in esterification, interesterification and transesterification reactions (Treichel et al. 2010), transforming hydrophobic compounds without co-factors and in a wide pH range (Collaço et al. 2020; Souza et al. 2016). In comparison to chemical catalysts, lipases are more stable in organic solvents, show broad substrate specificity and high yields. Triacylglycerol hydrolases are present in plants, animals and microorganisms, the latter being the most used in biotechnology, mainly in detergent production, followed by food industry (Souza et al. 2016).

Souza et al. (2016) used canola cake and soybean meal to cultivate Yarrowia lipolytica and induce lipase production in solid-state fermentation, using mild conditions. Palm cake and fiber were also used as feedstock to Rhizomucor miehei growth and PODD was used for enzymatic bioemulsifiers synthesis, resulting in a low-cost technique (Collaço et al. 2020). To produce lipase and xylanase, palm-pressed fiber and palm kernel cake were used as support in solid-state fermentation using Aspergillus niger, A. oryzae and A. awamori, resulting in ruminant feed with improved nutritional value (Oliveira et al. 2018). These agro-industrial wastes were able to support lipase production and the biocatalyst presented versatile characteristics once they catalyzed hydrolysis in different conditions of pH and temperature (Souza et al. 2016).

Lipase is one of the most important metabolites produced by Yarrowia lipolytica, a strict aerobic yeast, which can assimilate and ferment different carbon sources, including hydrophilic and hydrophobic substrates. This species is considered generally regarded as safe (GRAS) by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) due to its non-growth in temperatures above 32 °C, which makes its metabolites good bioproducts for the food industry (Liu and Huang 2015; Coelho et al. 2010). Y. lipolytica produces extra and intracellular lipases, which can also be associated to cell wall, as reported in our previous study (Fraga et al. 2018). These lipases isoforms have different characteristics and thus can be applied in many processes, such as obtaining structured lipids (Akil et al. 2020) or Lipolyzed Milk Fat (LMF) (Fraga et al. 2018). Y. lipolytica is the most studied unconventional yeast, however, there is still a lack of data regarding the use of some agro-industrial wastes to produce lipase by this microorganism. Besides, PODD and RFO are promising residual substances to induce lipase production by Y. lipolytica, by virtue of their composition and low market value. In this present study, we used PODD and two different RFO from palm oil to produce lipase by Y. lipolytica growing in submerged media to disclose the best feedstock to produce lipase, and to obtain the profile of lipase isoform (extracellular, intracellular and cell associated) distribution. The applicability and reuse of this biocatalyst was tested as a proof-of-concept for this platform as a biotechnological process.

Methods

Materials

Palm Oil Deodorizer Distillate (PODD) originated from palm oil refining process was kindly provided by Companhia Refinadora da Amazônia (São Paulo, Brazil). A commercial residual frying oil (RFO_commercial) was obtained by Brazil Fast Food Corporation (from a fast-food restaurant) and was characterized as palm oil. A lab RFO (RFO_palm) was obtained after frying potatoes in a bench-scale for five times using a virgin palm oil (VPO). Peptone and yeast extract were obtained from Kasvi (Paraná, Brazil) and glucose from Vetec (St. Louis, MO, USA). p-nitrophenyl laurate (p-NPL) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Brazil (São Paulo, Brazil) and dimethyl sulfoxide obtained from Isofar (Rio de Janeiro, Brazil). Antifoam 204 was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) to reduce foaming.

Microorganism

Microorganism used was the wild type strain Yarrowia lipolytica strain (IMUFRJ 50,682) [28]. Cells were stored at 4 °C in YPD (Yeast extract, Peptone and Dextrose) medium containing (w/v): 1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% glucose and, 2% Agar–agar (Brígida et al. 2014).

Lipases production in stirring flasks

Pre-inoculum was carried out in 500 mL Erlenmeyer flask with 200 mL of YPD medium (2% peptone, 1% yeast extract and 2% dextrose) at 28 °C and 160 rpm for 75 h and an initial cell density of 1 g/L was used in each production medium. Lipase production was carried out, as described by Fraga et al (2018), in 1000 mL Erlenmeyer flasks with 200 mL of production medium (6.4 g/L peptone, 10 g/L yeast extract and 2.5 g/L PODD, RFO_commercial, RFO_palm or VPO) at 28 °C and 250 rpm for 75 h in shaker. Samples were collected during this period. During the lipase production process, the culture medium with the Y. lipolytica cells was centrifuged at 4 °C for 5 min (26,000 g). Extracellular lipase extract (supernatant) was separated in falcon tubes and stored at − 18 °C.

For RFOs and VPO, other lipase fractions were also obtained as follows: Cells were washed with distilled water and with 200 mM 3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid (MOPS) buffer pH 7.0 and centrifuged according to the previous condition. Cells were suspended in MOPS buffer and taken to the ultrasound (two steps in 150 W and frequency of 20 kHz for 9 min) in an ice bath followed by centrifugation. Supernatant, corresponding to intracellular enzymatic fraction, was placed in tubes, and stored at − 18 °C. The precipitate (cell debris), corresponding to lipase cell associated fraction, was suspended in MOPS buffer, and stored at −18 °C (Fraga et al. 2018).

Hydrolysis of anhydrous milk fat with Lipase

Pasteurized unsalted nonfermented butter was pretreated according to Fraga et al (2018). Water was removed using a separating funnel at 60 °C and fat was filtered in normal paper filter and dried in vacuum condition 800 mbar for 1 h in a boiling water bath. Anhydrous nitrogen was bubbled in the melted butterfat for 5 min to remove the residual oxygen and water. The dried milk fat was stored in 500 mL Scott flasks at 30 °C until characterization and hydrolysis reactions. The hydrolysis reactions of milk fat were carried out at 37 °C, following the procedure described by Regado et al. (2007), with some modifications. Anhydrous milk fat stored in Scott flasks was heated at 40 °C in water bath. This milk fat (0.5 mL) was transferred to an amber flask, where 15 mL of 50 mM of Tris–HCl buffer (pH 7.0) and enzyme (lipase associated to cell debris produced with RFO_commercial) were added. The reaction was performed in rotary incubator at 37 °C and at 250 rpm. The following reaction conditions were used: amount of lipase (0.75 g) and hydrolysis time (6 h).

Analytical methods

Cell concentration and pH

Cell growth was measured by optical density at 570 nm and these values were converted to g dry weigh/L using a conversion factor previously determined. pH was measured in a bench pH meter.

Determination of enzyme activity

Determination of enzymatic activity of lipase was performed by hydrolysis of p-NPL. In this method, 1.9 mL of 560 μM p-NPL dissolved in 50 mM potassium-phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) containing 1% (v/v) dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was mixed, at 37 ºC, with 0.1 mL of enzyme in crude extracts. The production of p-nitrophenol, which is a product of the enzymatic reaction, was followed by 100 s in a spectrophotometer at λ = 410 nm. One lipase unit (U) is defined as the amount of enzyme which releases 1 μmol of p-nitrophenol per minute at pH 7.0 and 37 ºC (Pereira et al. 2019).

Oils’ fatty acid composition by gas chromatography (GC)

The bands of free fatty acids scraped from the TLC plates were analyzed by gas chromatography. The free fatty acids were methylated according to Lepage and Roy (1986). A GC-2010 gas-chromatograph (Shimadzu, Japan) was used for all analyzes, and the split/splitless injector was operated with a 1:30 split ratio. A moderately polar capillary column (polyethylene glycol; Omegawax-320, 30 m, 0.32 mm i.d., 0.25 µm film thickness; Sigma-Aldrich, São Paulo, Brazil) was used to separate the fatty acid methyl esters, using He as carrier gas (25.0 cm/s). The injector and detector temperatures were set at 260 and 280 C, respectively. Column oven temperature was held at 40 °C for 3 min, then temperature programmed at 6.5 °C/min to 180 °C and held for 3 min, then temperature programmed at 2.0 °C/min to 210 °C and held for 15 min. Identification of fatty acid methyl esters (FAME) was made by comparison to relative retention times of commercial standards. The Equivalent Chain Lengths (Mhøs and Grahl-Nielsen (2006) and the mathematical method described by Torres et al. (2002) were used to complement the characterization of samples’ FAs, through analysis of FAME peaks absent in the standard mixture. The fatty acids were expressed as mol% of total fatty acids. All analyses were performed in duplicates.

Acyl-glycerols lipid profile by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)

Milk fat hydrolysis was monitored by determination of lipid classes following a procedure adapted from Tan and Brzuskiewicz (1989) in a HPLC (Pump LC-20at, Degasser DGU-20A5 and communicator module CBM-20A; Shimadzu®, Japan). Samples were dissolved in an injection solution, composed of acetonitrile:isopropanol:hexane (2:2:1, v/v/v) and a reversed-phase HPLC column (C18, 5 µm, 250 mm × 4.6 mm, Kromasil®; AkzoNobel®, Sweden) was used. The lipid analytes were eluted with a mobile phase gradient of acetonitrile (A) and isopropanol (B), at 1.0 mL/min, from 0 to 69% B from 0 to 60 min, followed by re-equilibration until 0% B, from 60 to 76 min. The eluate was monitored with an evaporative light scattering detector (ELSD-LT II; Shimadzu®, Japan), using N2 as nebulizer gas at 0.65 mL/min, and drift tube temperature at 40 °C. Lipid classes of TAGs-DAGs and FFAs-MAGs were identified comparing with commercial standards and quantified by internal normalization. Results were expressed in g/100 g of total lipids.

Results and discussion

Characterization of palm feedstocks

Virgin palm oil and different palm oil wastes (Residual Frying Oil from palm oil used to fry potatoes in a bench-scale – RFO_palm; Residual Frying Oil from commercial source – fast-food restaurant – RFO_commercial and Palm oil deodorizer distillate—PODD) were used to produce extracellular lipase by Y. lipolytica in submerged fermentation. Oily residues show great potential to produce lipolytic enzymes, because in addition to serve as carbon source, it also acts as an inducer to produce this class of enzymes (Fickers et al. 2004). These residues used here were characterized according to their lipid classes, because it can influence microbial metabolic response. Table 1 shows the results obtained in the identification of the lipid classes of the different studied residues.

Table 1.

Lipid classes and free fatty acids for different types of palm oil wastes

| Lipid Classes | Virgin palm oil (VPO) | Residual frying oil (RFO) | Palm oil deodorizer distillate (PODD) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RFO_palm | RFO_commercial | |||

| MAG + FFA (%) | 0.00 | 0.11 ± 0.06 | 0.00 | 83.00* |

| DAG (%) | 2.70 ± 0.99 | 1.51 ± 0.47 | 6.70 ± 2.29 | – |

| TAG (%) | 97.30 ± 0.99 | 97.51 ± 1.92 | 93.30 ± 2.29 | – |

FFA Free of Fatty Acids; MAG Monoacylglycerol; DAG Diacylglycerol; TAG Triacylglycerol; RFO_palm Residual Frying Oil from frying potatoes in a bench-scale with VPO; RFO_commercial Residual Frying Oil from commercial source (fast-food restaurant)

*Nascimento et al. (2011)

Table 1 shows that the VPO, RFO_palm and RFO_palm are mainly composed of triacylglycerol and small amounts of diacylglycerol, while the PODD is mostly composed of free fatty acids, as a result of being obtained in one of palm oil refining stages (Nascimento et al. 2011). The results point out a slightly inferior amount of TAG for RFO_commercial, indicating a superior stage of degradation.

Table 2 depicts the similarities and differences between the fatty acid composition of RFO and PODD. Most values are in the range of virgin palm oil, showing the similar profile. However, palmitic, linoleic and linolenic acids amount in RFO_commercial are the exceptions, with values 25% inferior for palmitic acid and 42% and 55% superior for linoleic and linolenic acids, respectively, in relation to PODD. These differences can influence microbial metabolism.

Table 2.

Fatty acid profile in different palm oil wastes

| Fatty acids | Palm oil deodorizer distillate (PODD)* | Residual frying oil RFO_commercial | Virgin Palm Oil (VPO)** |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lauric C12:0 | 0.2 | – | < 0.4 |

| Miristic C14:0 | 1.2 | – | 0.5–2.0 |

| Palmitic C16:0 | 47.4 | 35.47 ± 0.37 | 40.0–48.0 |

| Estearic C18:0 | 4.7 | 4.74 ± 0.03 | 3.5–6.5 |

| Oleic C18:1 | 36.5 | 42.48 ± 0.38 | 36.0–44.0 |

| Linoleic C18:2 | 9.6 | 16.41 ± 0.38 | 6.5–12.0 |

| Linolenic C18:3 | 0.4 | 0.90 ± 0.04 | < 0.5 |

*Data from Aguieiras et al. (2019)

**Data from AOCS; RFO_commercial Residual Frying Oil from commercial source (fast-food restaurant)

Production of lipase with palm oil wastes

The different types of palm oil wastes were used as carbon sources for lipase production by Y. lipolytica (Table 3). No inhibitory effect in cell growth during lipase production was detected for any of the waste tested, since in all assays Y. lipolytica was able to grow, being more prominent for RFO_palm after 75 h.

Table 3.

Cultivation parameters of Yarrowia lipolytica IMUFRJ 50,682 in 1 L stirred flasks containing PODD and RFO residues at 28 °C and 160 rpm for 75 h

| Time (h) | Palm oil wastes | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Palm oil deodorizer distillate (PODD) | Residual Frying Oil (RFO) | ||

| RFO_palm | RFO_commercial | ||

| Cell concentration (g Dry Weight Cells/L) | |||

| 0 | 1.34 ± 0.77 | 1.48 ± 0.09 | 1.08 ± 0.10 |

| 48 | 12.45 ± 1.70 | 19.71 ± 0.70 | 12.23 ± 1.18 |

| 75 | 11.91 ± 0.72 | 19.55 ± 0.51 | 18.47 ± 2.12 |

| pH | |||

| 0 | 6.67 ± 0.02 | 6.98 ± 0.05 | 6.56 ± 0.04 |

| 48 | 6.11 ± 0.01 | 6.18 ± 0.72 | 6.49 ± 0.04 |

| 75 | 7.18 ± 0.20 | 5.82 ± 0.46 | 5.99 ± 0.11 |

| Lipase (U/L) | |||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 48 | 2326.89 ± 439.12 | 1827.88 ± 166.98 | 102.40 ± 50.06 |

| 75 | 1588.31 ± 537.70 | 1430.24 ± 282.38 | 4879.92 ± 712.80 |

RFO_palm Residual Frying Oil from frying potatoes in a bench-scale with palm oil, RFO_commercial Residual Frying Oil from commercial source (fast-food restaurant)

Table 3 also shows that for the RFOs pH tends to decrease over time, which is possibly related to the hydrolysis of free fatty acids formed by the action of lipases produced during fermentation. As PODD are mainly composed of FFA, this tendency was not observed for this feedstock, on the contrary, a pH increase can be observed.

Lipase was produced with all residues tested (Table 3), and the enzymatic activity values were higher than that found in the literature for shake flasks experiments and oily sources (olive oil: 0.3 U/mL; soy frying oil: 0.03 U/mL) (Fickers et al. 2005), mainly for RFO_commercial (almost 5 U/mL). PODD could be pointed out as better feedstock considering 48 h of process, with higher production and productivity (48.5 U/L.h). However, increasing process time, RFO_commercial presented better results (65.1 U/L.h). It seems that the FFA present in PODD induces lipase production right in the beginning and, as FFA are obtained later for RFOs, this effect occurs soon after.

This is the first report in literature od lipase production by Y. lipolytica with PODD as carbon source. Despite great potential of all palm oil wastes for lipase production, RFO_commercial was chosen here to evaluate the production of different lipase fractions by Y. lipolytica, since this feedstock showed greater results of production and productivity. RFO_palm was also chosen for comparison.

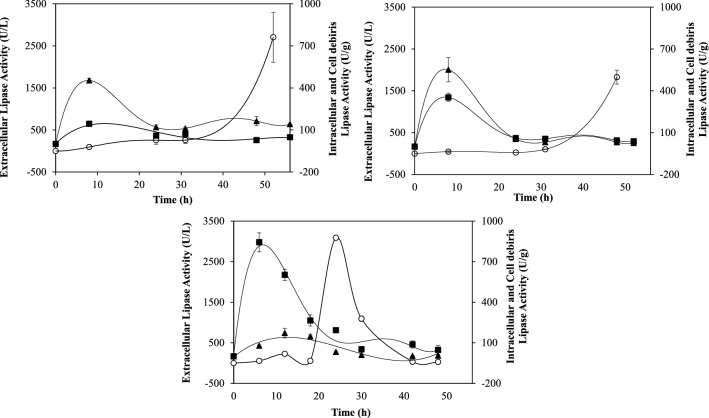

Production of lipases fractions with Residual Frying Oil from palm oil

Virgin palm oil and residual frying oils from palm source were tested to evaluate differential lipase fractions production by Y. lipolytica. Kinetic profiles of extracellular, intracellular and cell debris associated lipases depicts the effect of the feedstock in the production of these fractions (Fig. 1). Corroborating literature results (Pereira-Meirelles et al 2000; Fraga et al. 2020), the production of intracellular lipase fractions (free and cell associated forms) is more pronounced in the beginning of the process, when there is plenty of carbon source. Fickers et al. (2005) points out that part of these intracellular fractions starts to be secreted when carbon source becomes scarce. Despite the absence of substrate concentration data, this mechanism seems to be occurring with those palm oil sources (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Kinetic of lipase fractions produced by Y. lipolytica using (A) VPO (virgin palm oil); (B) RFO_palm (residual frying oil from an original virgin palm oil, fried in bench-scale); (C) RFO_commercial (residual frying oil from a palm oil obtained from a commercial fast-food restaurant). (○) Extracellular lipase fraction; (▲) Intracellular lipase fraction; (■) Lipase associated to cell debris

VPO and RFO_palm profiles are remarkably similar (Fig. 1), which might be related to the fact that RFO_palm was obtained in a controlled process in the lab and, therefore, their compositions are more alike as demonstrated by the lipid classes in Table 1. RFO_commercial, as a residual oil from a fast-food restaurant, is a more degraded oil, as shown by the lipid classes profile in Table 1. Therefore, the differential lipase fractions production profile depicts a possible secretion of the intracellular fractions (represented by the extracellular fraction) earlier than VPO and RFO_palm. Even so, a higher peak is also detected later (75 h) as shown in Table 3. These differences may also be related to FA composition, which was different for RFO_commercial, as shown in Table 2.

RFO_commercial induced a higher production of lipase associated to cell debris, with a productivity of 140 U/g.h, three times higher than RFO_palm and 8 times higher than VPO. RFO_commercial had already been tested by our group to obtain these lipase fractions by Y. lipolytica as reported in Fraga et al. (2018) and the lipase fraction associated to cell debris was also characterized in Fraga et al. (2020). However, in those studies, the kinetic profile was not accessed, and production was obtained in 24 h of bioprocess. In the present study, we could evaluate the production profile during time and obtain higher values in earlier times, improving productivity. Besides, the comparison to VPO and RFO_palm showed that the FA composition of this specific RFO improved productivity as well.

The main advantage of producing a lipase associated to the cell is that it is already immobilized, reducing costs and process time (Fraga et al. 2018, 2020). Therefore, lipase associated to cell debris produced with RFO_commercial was evaluated for its applicability to hydrolyze milk fat.

Hydrolysis of milk fat by lipase associated to cell debris produced with RFO_commercial

Lipase associated to cell debris was used in hydrolysis reactions of milk fat, aiming at the production of Lipolyzed Milk Fat (LMF). LMF is an important ingredient in the food industry and can be applied as an additive in bakery and dairy products (Fraga et al. 2018). Table 3 shows the results obtained in the hydrolysis reactions (Table 4).

Table 4.

Lipid classes observed after 6 h of milk fat hydrolysis with and without enzyme. The enzyme used was the lipase associated to cell debris obtained from the cultivation of Yarrowia lipolytica with commercial residual frying oil (RFO_commercial)

| Lipid Classes | Lipase-free | Added lipase |

|---|---|---|

| MAG/FFA (%) | 0.03 ± 0.04 | 13.1 ± 4.34 |

| DAG (%) | 0.54 ± 0.32 | 2.02 ± 1.39 |

| TAG (%) | 99.43 ± 0.28 | 84.8 ± 3.05 |

FFA Free of Fatty Acids; MAG Monoacylglycerol; DAGDiacylglycerol; TAG Triacylglycerol; LipImDebri Lipase Immobilized on cell Debris

It is noted that there was a significant hydrolysis of milk fat, with a yield of 13.1% of MAG/FFA. This result is considerably higher than that found in our previous study with the same enzyme (8.13%) (Fraga et al. 2018), that we could improve by altering the amount of enzyme and the procedure described in methodology section. This result was also better than that found by Regado et al. (2007) when studying the hydrolysis of milk fat with extracellular C. lipolytica lipase, in which they obtained a hydrolysis a yield of 5%. A control experiment was also carried out to identify whether the water in the reaction medium positively influenced the hydrolysis yield. The results showed that there was no production of significant amounts of MAG/FFA, which are the fraction that constitutes LMF, indicating that water does not promote the hydrolysis of milk fat.

The advantage of using an immobilized biocatalyst is the possibility to reuse it several time, reducing costs. Therefore, the reuse of the lipase associated to debris cells produced with RFO_commercial was tested in successive milk fat hydrolysis reactions (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Reuse of Yarrowia lipolytica lipase associated to cell debris produced with RFO_commercial (residual frying oil from a palm oil obtained from a commercial fast-food restaurant) in in the production of Lipolyzed Milk Fat (LMF). The production obtained of the first cycle was adjusted to 100%. aMean values followed by the same letter do not differ from each other with a confidence level of 95% by the Fisher test

The results show that there is no significant difference in the production of lipolyzed milk fat over the three reaction cycles studied. This indicates that lipase immobilized on cell debris is an excellent biocatalyst to be used in hydrolysis reactions.

Conclusions

Palm oil residues were able to induce lipase production by Y. lipolytica increasing the enzyme activity, including Palm oil deodorizer distillate (PODD). Waste oils have proven to be very efficient alternative carbon sources for lowering the process cost, which is an advantage for enzyme production. Residual frying oil obtained from a fast-food restaurant (RFO_commercial) with a specific FA profile, was the best inducer for extracellular lipase production and to obtain lipase associated to cell debris. This biocatalyst was efficient for the hydrolysis of anhydrous fat and also in successive reactions, showing its potential in industrial applications.

Abbreviations

- CPO

Crude palm oil

- DAG

Diacylglycerol

- DMSO

Dimethyl sulfoxide

- FA

Fatty acid

- FAME

Fatty acid methyl ester

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- FFA

Free fatty acid

- GC

Gas chromatography

- GRAS

Generally recognized as safe

- HPLC

High performance liquid chromatography

- LMF

Lipolyzed milk fat

- MAG

Monoacylglycerol

- MOPS

3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid

- PODD

Palm Oil Deodorizer Distillate

- RFO

Residual frying oil

- RFO_commercial

Residual frying oil from an original palm oil, obtained from a commercial fast-food restaurant

- RFO_palm

Residual frying oil from an original virgin palm oil, obtained by frying potatos for five times in a bench-scale

- TAG

Triacylglycerol

- VPO

Virgin palm oil

- YPD

Yeast Extract, Peptone, Dextrose

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization: PFFA, JF, ECGA; Data curation: PFFA; Formal analysis: LOS, JLF; Funding acquisition: AGT, PFFA, DGF; Investigation: CPLS, JLF; Methodology: CPLS, ASP, JLF, PFFA; Project administration: PFFA; Resources: AGT, PFFA, DGF; Software: JLF ASP; Supervision: PFFA; Validation: JLF; Visualization: CPLS, JLF, PFFA; Roles/Writing—original draft: CPLS, JLF, ASP; Writing—review & editing: PFFA, ECGA.

Funding

The financial support of Fundação Carlos Chagas Filho de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ—grant number E-26/202.870/2015 BOLSA), Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES–001/Bolsa) and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq—Bolsa).

Declartions

Conflict of interest

All authors declare no competing/ conflicts of interests. The funders had no decision on the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, and in the decision to publish the results.

Accession numbers

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Jully L. Fraga and Camila P. L. Souza share first authorship.

References

- Aguieiras ECG, De Barros DSN, Sousa H, Fernandez-Lafuente R, Freire DMG. Influence of the raw material on the final properties of biodiesel produced using lipase from Rhizomucor miehei grown on babassu cake as biocatalyst of esterification reactions. Renew Energy. 2017;113:112–118. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2017.05.090. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aguieiras ECG, Papadaki A, Mallouchos A, Mandala I, Sousa H, Freire DMG, Koutinas AA. Enzymatic synthesis of bio-based wax esters from palm and soybean fatty acids using crude lipases produced on agricultural residues. Ind Crops Prod. 2019;139:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2019.111499. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ai O, Phuah E, Lee Y, Basiron Y. Palm oil. In: Shahidi F, editor. Bailey’s industrial oil and fat products. John Wiley and Sons; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Akil E, Pereira AS, El-Bacha T, Amaral PFF, Torres AG. Efficient production of bioactive structured lipids by fast acidolysis catalyzed by Yarrowia lipolytica lipase, free and immobilized in chitosan-alginate beads, in solvent-free medium. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;163:910–918. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.06.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brígida AI, Amaral PFF, Gonçalves LR, Rocha-Leão MHM, Coelho MAZ. Yarrowia lipolytica IMUFRJ 50682: Lipase production in a multiphase bioreactor. Curr Biochem Eng. 2014;1:65–74. doi: 10.2174/22127119113019990005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carter C, Finley W, Fry J, Jackson D, Willis L. Palm oil markets and future supply. Eur J Lipid Sci Technol. 2007;109:307–314. doi: 10.1002/ejlt.200600256. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choe E, Min DB. Chemistry of deep-fat frying oils. J Food Sci. 2007;72(5):R77–R86. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2007.00352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coelho MAZ, Amaral PFF, Belo I. Yarrowia lipolytica: an industrial workhorse. In: Villas M, editor. Technology and education topics in applied microbiology and microbial biotechnology. Formatex Researcher Center; 2010. pp. 930–944. [Google Scholar]

- Collaço ACA, Aguieiras ECG, Cavalcanti EDC, Freire DMG. Development of an integrated process involving palm industry co-products for monoglyceride/diglyceride emulsifier synthesis: use of palm cake and fiber for lipase production and palm fatty-acid distillate as raw material. LWT. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2020.110039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dumont M, Narine SS. Soapstock and deodorizer distillates from North American vegetable oil: review on their characterization, extraction and utilization. Food Res Int. 2007;40:957–974. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2007.06.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Echim C, Verhé R, Stevens C, De Greyt W. Valorization of by-products for the production of biofuels. In: Luque R, Campelo J, Clark J, editors. Handbook of biofuels production. 7. Woodhead Publishing Series in Energy; 2016. pp. 581–610. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes KV, Papadaki A, Da Silva JAC, Fernandez-Lafuente R, Koutinas AA, Freire DMG. Enzymatic esterification of palm fatty-acid distillate for the production of polyol esters with biolubricant properties. Ind Crops Prod. 2018;116:90–96. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2018.02.058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fickers P, Nicaud JM, Gaillardin C, Destain J, Thonart P. Carbon and nitrogen sources modulate lipase production in the yeast Yarrowia lipolytica. J Appl Microbiol. 2004;96:742–749. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2004.02190.xv. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fickers P, Fudalej F, Le Dall MT, Casaregola S, Gaillardin C, Thonart P, Nicaud JM. Identification and characterisation of LIP7 and LIP8 genes encoding two extracellular triacylglycerol lipases in the yeast Yarrowia lipolytica. Fungal Genet Biol. 2005;42(3):264–274. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraga JL, Penha ACB, Pereira AS, Silva KA, Akil E, Torres AG, Amaral PFF. Use of Yarrowia lipolytica lipase immobilized in cell debris for the production of lipolyzed milk fat (LMF) Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(11):3413. doi: 10.3390/ijms19113413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraga JL, da Penha ACB, Akil E, et al. Catalytic and physical features of a naturally immobilized Yarrowia lipolytica lipase in cell debris (LipImDebri) displaying high thermostability. Biotech. 2020;10:454. doi: 10.1007/s13205-020-02444-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibon V, De Greyt W, Kellens M. Palm oil refining. Eur J Lipid Sci Technol. 2007;109:315–335. doi: 10.1002/ejlt.200600307. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta A, Rathod VK. Solar radiation as a renewable energy source for the biodiesel production by esterification of palm fatty acid distillate. Energy. 2019;182:795–801. doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2019.05.189. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haegler AN, Mendonça-Haegler LC. Yeast from marine and stuarine waters with different levels of pollution in the state of Rio de Janeiro Brazil. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1981;41(1):173–178. doi: 10.1128/AEM.41.1.173-178.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepage G, Roy CC. Direct transesterification of all classes of lipids in a one-step reaction. J Lipid Res. 1986;27(1):114–120. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2275(20)38861-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu HH, Ji XJ, Huang H. Biotechnological applications of Yarrowia lipolytica: past, present and future. Biotechnol Adv. 2015;33:1522–1546. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2015.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malaysian palm oil board (MPOB) (2019) Overview of the Malaysian oil palm industry 2019. http://bepi.mpob.gov.my/images/overview/Overview_of_Industry_2019.pdf (Accessed 20 June 2020)

- Mba OI, Dumont M-J, Ngadi M. Palm oil: Processing, characterization and utilization in the food industry – A review. Food Biosci. 2015;10:26–41. doi: 10.1016/j.fbio.2015.01.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mhøs S, Grahl-Nielsen O. Prediction of gas chromatographic retention of polyunsaturated fatty acid methyl esters. J Chromatogr A. 2006;11:171–180. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2006.01.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nascimento LAS, Angélica RS, Da Costa CEF, Zamian JR, Filho GNR. Conversion of waste produced by the deodorization of palm oil as feedstock for the production of biodiesel using a catalyst prepared from waste material. Bioresour Technol. 2011;102(17):8314–8317. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira AC, Amorim GM, Azevêdo JAG, Godoy MG, Freire DMG. Solid-state fermentation of co-products from palm oil processing: production of lipase and xylanase and effects on chemical composition. Biocatal Biotransform. 2018;36(5):381–388. doi: 10.1080/10242422.2018.1425400. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Outoye MA, Wong CP, Chin LH, Hameed BH. Synthesis of FAME from the methanolysis of palm fatty acid distillate using highly active solid oxide acid catalyst. Fuel Process Technol. 2014;124:54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.fuproc.2014.02.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira AS, Fontes-SantAna GC, Amaral PFF. Mango agro-industrial wastes for lipase production from Yarrowia lipolytica and the potential of the fermented solid as a biocatalyst. Food Bioprod Process. 2019;115:68–77. doi: 10.1016/j.fbp.2019.02.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira-Meirelles FV, Rocha-Leão MHM, SantAnna GL. Lipase location in Yarrowia lipolytica cells. Biotechnol Lett. 2000;22:71–75. doi: 10.1023/A:1005672731818. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raita M, Laothanachareon T, Champreda V, Laosiripojana N. Biocatalytic esterification of palm oil fatty acids for biodiesel production using glycine-based cross-linked protein coated microcrystalline lipase. J Mol Catal B Enzimatic. 2011;73:74–79. doi: 10.1016/j.molcatb.2011.07.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Regado MA, Cristóvão BM, Moutinho CG, Balcão VM, Aires-Barros R, Ferreira JPM, Malcata FX. Lipolysis of milkfats for flavour. Int J Food Sci Technol. 2007;42:961–968. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2006.01317.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rehab MA, Elkatory MR, Hamad HA. Highly active and stable magnetically recyclable CuFe2O4 as heterogenous catalyst for efficient conversion of waste frying oil to biodiesel. Fuel. 2020;2:117297. [Google Scholar]

- Santos APP, Silva MDS, Costa EVL, Rufino RD, Santos VA, Ramos CS, Sarubbo LA, Porto ALF. Production and characterization of biosurfactant produced by Streptomyces sp. DPUA 1559 isolated from lichens of the Amazon region. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2018;51(2):e6657. doi: 10.1590/1414-431x20176657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheil D, Casson A, Maijaard E, Noordwijk M, Gaskell J, Sunderland-groves J, Wertz K, Kanninen M. The impacts and opportunities of oil palm in Southeast Asia. Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR); 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Souza CEC, Farias MA, Ribeiro BD, Coelho MAZ. Adding value to agro-industrial co-products from canola and soybean oil extraction through lipase production using Yarrowia lipolytica in solid-state fermentation. Waste Biomass Valor. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s12649-016-9690-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tan B, Brzuskiewicz L. Separation of tocopherol and tocotrienol isomers using normal- and reverse-phase liquid chromatography. Anal Biochem. 1989;180:368–437. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(89)90447-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan Y, Sambanthamurthi R, Sundram K, Wahid MB. Valorisation of palm by-products as functional components. Eur J Lipid Sci Technol. 2007;109(4):380–393. doi: 10.1002/ejlt.200600251. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Torres AG, Trugo NM, Trugo LC. Mathematical method for the prediction of retention times of fatty acid methyl esters in temperature-programmed capillary gas chromatography. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50:4156–4163. doi: 10.1021/jf011259j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treichel H, Oliveira D, Mazutti DL. A review on microbial lipases production. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2010;3:182–196. doi: 10.1007/s11947-009-0202-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wahid MB, Abdullah SNA, Henson IE. Oil palm—achievements and potential. Plant Production Science. 2005;8(3):288–297. doi: 10.1626/pps.8.288. [DOI] [Google Scholar]