Abstract

Introduction

In this meta-analysis, we aimed to systematically compare the 10-year outcomes of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) versus coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) suffering from left main coronary artery disease (LMCD).

Methods

Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online (MEDLINE), http://www.ClinicalTrials.gov, Excerpta Medica dataBASE (EMBASE), Cochrane Central, Web of Science, and Google scholar were searched for publications comparing 10-year outcomes of PCI versus CABG in patients with T2DM suffering from LMCD. Cardiovascular outcomes were considered as the clinical endpoints. Statistical analysis was carried out using RevMan software (version 5.4). Risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were used to represent the data after analysis.

Results

Eight studies (three randomized trials and five observational studies) with a total number of 3835 participants with T2DM were included in this analysis; 2340 participants were assigned to the PCI group and 1495 participants were assigned to the CABG group. Results of this analysis showed that mortality (RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.73–1.00; P = 0.05), myocardial infarction (RR 0.53, 95% CI 0.35–0.80; P = 0.002), repeated revascularization (RR 0.34, 95% CI 0.26–0.46; P = 0.00001), and target vessel revascularization (RR 0.26, 95% CI 0.18–0.38; P = 0.00001) were significantly higher with PCI when compared to CABG in these patients with diabetes and LMCD. Major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events were also significantly higher with PCI at 10 years (RR 0.67, 95% CI 0.49–0.92; P = 0.01). However, CABG was associated with a significantly higher risk of stroke (RR 2.16, 95% CI 1.39–3.37; P = 0.0007).

Conclusions

During a long-term follow-up time period of 10 years, PCI was associated with worse clinical outcomes compared to CABG in these patients with T2DM suffering from LMCD. However, a significantly higher risk of stroke was observed with CABG. This piece of information might be vital in order to carefully choose and prevent complications following revascularization in such patients.

Keywords: Cardiovascular disease, Coronary artery bypass grafting, Left main coronary disease, Long-term outcomes, Percutaneous coronary intervention, Revascularization therapies, Type 2 diabetes mellitus

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| Diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease often co-exist. |

| Until now, no meta-analysis has assessed 10-year outcomes of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) versus coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) suffering from left main coronary disease (LMCD). |

| What was learned from this study? |

| During a long-term follow-up time period of 10 years, PCI was associated with worse clinical outcomes compared to CABG in these patients with T2DM suffering from LMCD. However, a significantly higher risk of stroke was observed with CABG in patients with T2DM at 10-year follow-up. |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including a summary slide, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.13721461.

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and cardiovascular diseases (CVD) often co-exist [1]. Silent myocardial infarction and left main coronary artery disease (LMCD) have often been observed as cardiovascular complications in patients with T2DM [2]. It should be highlighted that a significant lesion in the left main coronary artery is considered as the most prognostically important coronary lesion because this artery supplies blood to approximately 70% of the left ventricular myocardial tissues [3].

Fortunately, owing to advances in medical and invasive treatments, both coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG) and percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) are possible revascularization techniques which have been used to prevent further cardiovascular events in these patients with T2DM [4].

Several meta-analyses have been carried out to compare PCI versus CABG [5, 6]. However, several limitations were also noted in those studies. For example, many meta-analyses were based on patients with multivessel coronary disease [7], while other meta-analyses were restricted to a follow-up time period of up to 5 years only [8]. In addition, only a few studies comprised specifically patients with T2DM.

Results from previous meta-analyses are controversial. A most comprehensive and updated meta-analysis which was published in 2017 demonstrated no difference between PCI and CABG for LMCD [9]. The authors stated that both revascularization procedures could be used to manage and treat patients. In another meta-analysis which was published during the same year, the authors concluded that PCI was non-inferior to CABG during the short term; however, CABG was more safe and effective in patients with LMCD during the long-term follow-up [10]. Still in 2017, another study demonstrated that PCI was associated with less major cardiac events during the short term but with increased cardiac events during the long term in comparison to CABG [11]. It was not clear whether the outcomes increased with increased duration of follow-up.

However, this trend changed in the year 2020 with upcoming new studies. A study comparing 5-year outcomes with PCI versus CABG for LMCD showed CABG to have a significant advantage over PCI in terms of major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events [12]. Nevertheless, all these studies were carried out in the general population with LMCD.

In this meta-analysis, we aimed to systematically compare the 10-year outcomes of PCI versus CABG in patients with T2DM suffering from LMCD.

Methods

Data Sources

Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online (MEDLINE), http://www.ClinicalTrials.gov, Excerpta Medica dataBASE (EMBASE), Cochrane Central, Web of science and Google scholar were searched for publications comparing 10-year outcomes of PCI versus CABG in patients with T2DM suffering from LMCD.

Search Strategy

The search terms or phrases included:

Percutaneous coronary intervention versus coronary artery bypass grafting and left main coronary disease

Percutaneous coronary intervention versus coronary artery bypass grafting and left coronary artery disease

Percutaneous coronary intervention versus coronary artery bypass grafting and left main coronary disease and diabetes mellitus

PCI, CABG, left main coronary disease

Coronary stenting, coronary artery bypass grafting, and left main coronary disease

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria were:

Studies that compared PCI versus CABG for LMCD

Studies that consisted of participants with T2DM

Studies that involved a follow-up time period of 10 years

Studies that were published in English

The exclusion criteria were:

Studies that compared PCI versus CABG for LMCD with a follow-up time period of less than 10 years

Studies that did not comprise patients with T2DM

Studies that were review articles or case studies

Studies that were published in a different language apart from English

Studies that were repeatedly obtained in different search databases, or duplicated studies involving the same trial

Definitions, Outcomes, and Follow-Up

Table 1 lists the outcomes which were reported in the original studies. All the studies consisted of patients with T2DM suffering from LMCD and had a follow-up time period of 10 years.

Table 1.

Outcomes reported

| Studies | Outcomes reported | Type of participants | Follow-up time period (years) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benedetto 2014 [16] | Mortality, revascularization, TVR | T2DM with LMCD | 10 |

| Goy 2008 [17] | Mortality, MI, TLR, TVR, MACEs | T2DM with LMCD | 10 |

| Lee 2020 [18] | Mortality, MACEs, TVR | T2DM with LMCD | 10 |

| Li 2017 [19] | Mortality, stroke, revascularization, MI, MACCEs | T2DM with LMCD | 10 |

| Merkle 2014 [20] | Mortality, revascularization | T2DM with LMCD | 10 |

| Park 2010 [21] | Mortality, MI, stroke, MACCEs, revascularization, TVR, TLR | T2DM with LMCD | 10 |

| Park 2020 [22] | MACCEs, mortality, MI, stroke, revascularization, stent thrombosis | T2DM with LMCD | 10 |

| Thuijs 2019 [23] | Mortality | T2DM with LMCD | 10 |

TVR target vessel revascularization, MI myocardial infarction, TLR target lesion revascularization, MACE major adverse cardiac event, MACCE major adverse cardiac and/or cerebrovascular event, T2DM type 2 diabetes mellitus, LMCD left main coronary disease

The outcomes which were analyzed in this study included:

Mortality (cardiac and non-cardiac)

Myocardial infarction (MI) including fatal and non-fatal MI

Major adverse cardiac and/or cerebrovascular events (MACCEs) consisting of mortality (cardiac and all-cause mortality), fatal or non-fatal MI, fatal or non-fatal stroke (both ischemic and hemorrhagic) and/or revascularization

Stroke including both ischemic and hemorrhagic

Target vessel revascularization (TVR) defined as any repeated PCI or CABG due to re-stenosis or re-occlusion in/of the target vessel

Repeated revascularization consisting of target lesion revascularization and TVR

Data Extraction and Methodological Quality Assessment

The authors independently extracted data. Any disagreement which occurred during the data extraction process was resolved by consensus.

The following data were extracted: the authors’ names, the year of publication, the total number of participants who were assigned to the PCI and CABG groups respectively, the cardiovascular outcomes which were reported, the duration of follow-up time period, the types of participants and the types of studies which were involved, the participants’ enrollment time period, the baseline features of the participants including age, gender, and comorbidities, and the total number of events associated with each outcome.

The methodological quality assessment of the randomized trial was carried out on the basis of the recommendations of the Cochrane Collaboration [13], whereas the quality assessment of the observational cohorts was carried out using the Newcastle Ottawa Scale (NOS) [14]. A grade ranging from A to C was allotted to each study, whereby a grade A denoted a low risk of bias, and a grade C denoted a high risk of bias.

Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis was carried out using the latest version of RevMan software (version 5.4). Heterogeneity was assessed by two statistical methods: (a) the Q statistic test whereby an analysis was considered to be statistically significant if the associated P value was less or equal to 0.05, and (b) the I2 statistical test whereby the heterogeneity increased with an increasing I2 value.

A fixed or a random statistical model was used during the analysis and based on the I2 value. A fixed effect model was used if the I2 value was less than 50%, whereas a random effect model was used if the I2 value was above 50%.

Risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were used to represent the data following analysis.

A sensitivity analysis was also carried out by an exclusion method and the result obtained was finally compared with the main result of this analysis to observe for any significant change. In addition, publication bias was also visually estimated by assessing funnel plots.

Compliance with Ethical Guidelines

This article was based on previously conducted studies and did not contain any study with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Results

Search Outcomes

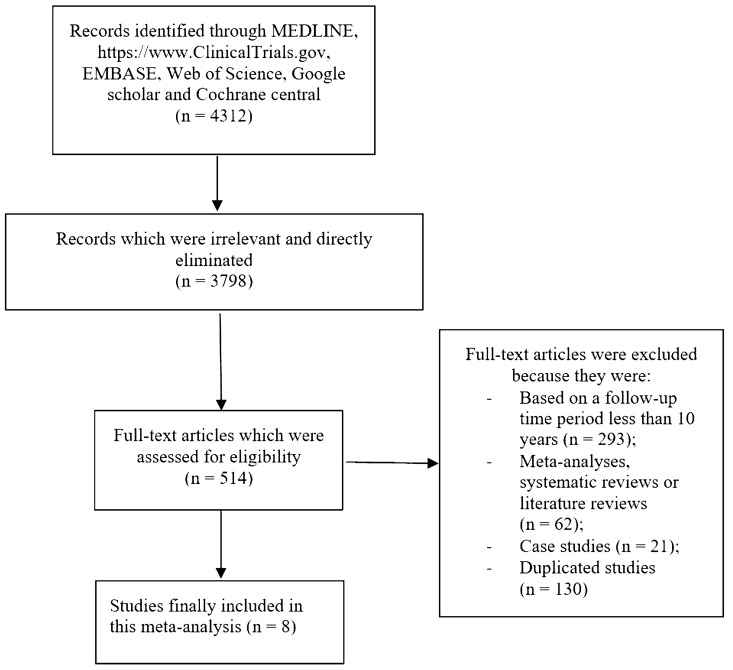

The Preferred Reporting Items in Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guideline was followed [15]. A total number of 4312 publications were obtained. Following an initial check, 3798 publications were eliminated because of irrelevance. Therefore, 514 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. The abstracts and titles were again carefully assessed.

On the basis of the inclusion and exclusion criteria, further eliminations were carried out: 293 articles were eliminated because they were based on a follow-up time period less than 10 years; 62 publications were meta-analyses, systematic reviews, or literature reviews; 21 articles were case studies; and 130 articles were duplicated studies. Finally, only eight studies [16–23] including three randomized trials and five observational cohorts were selected for this analysis as shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram showing the study selection

Main and Baseline Features of the Studies

Eight studies with a total number of 3835 participants with T2DM were included in this analysis; 2340 participants were assigned to the PCI group whereas 1495 participants were assigned to the CABG group as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Main features of the studies

| Studies | Type of study | Enrollment time period | No. of participants with T2DM assigned to PCI (n) | No. of participants with T2DM assigned to CABG (n) | Bias risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benedetto 2014 | OC-retrospective | 2001–2013 | 45 | 58 | B |

| Goy 2008 | RCT | 1994–1998 | 7 | 8 | B |

| Lee 2020 | OC | 2000–2006 | 327 | 395 | B |

| Li 2017 | OC | 2006–2016 | 1501 | 517 | B |

| Merkle 2014 | OC-retrospective | 2006–2012 | 17 | 31 | B |

| Park 2010 | OC-retrospective | 2003–2004 | 21 | 82 | B |

| Park 2020 | RCT | 2004–2009 | 102 | 90 | B |

| Thuijs 2019 | RCT | 2005–2007 | 320 | 314 | B |

| Total no of patients (n) | 2340 | 1495 |

T2DM type 2 diabetes mellitus, PCI percutaneous coronary intervention, CABG coronary artery bypass grafting, OC observational cohort, RCT randomized controlled trials

The baseline features of the participants are listed in Table 3. The mean age of the participants varied from 41.9 to 67.0 years. The study by Merkle [20] consisted of the eldest participants in the PCI group with a mean age of 67.0 years, whereas the study by Thuijs [23] consisted of the eldest participants who underwent CABG with a mean age of 65.0 years. In contrast, the study by Li [19] involved the youngest participants with a mean age of 41.9 years for those who were categorized in the PCI group and 42.0 years for those who were categorized within the CABG group. The mean percentage of male participants ranged between 60.0% and 90.9%. The study by Li [19] consisted of the highest number of male participants (> 90%) in both groups in comparison to the other studies. In addition, the percentages of participants with comorbidities such as hypertension (23.0–86.8%), dyslipidemia (33.6–81.5%), and current smoker (4.00–66.0%) have also been listed. As shown in Table 3, the study by Merkle [20] consisted of the highest percentage of patients with hypertension, whereas the study by Park [21] consisted of the lowest number of participants with hypertension. In addition, dyslipidemia was highest in the study by Thuijs [23], whereas cigarette smoking was lowest in this same study.

Table 3.

Baseline features

| Studies | Age (years) | Males (%) | HBP (%) | DL (%) | CS (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCI/CABG | PCI/CABG | PCI/CABG | PCI/CABG | PCI/CABG | |

| Benedetto 2014 | 73.7/82.8 | 53.6/70.0 | 63.6/81.5 | 14.5/7.60 | |

| Lee 2020 | 63.5/63.6 | 69.7/74.4 | 60.2/57.7 | 33.6/35.2 | 22.0/27.1 |

| Li 2017 | 41.9/42.0 | 90.1/90.9 | 60.8/63.5 | – | 66.0/65.3 |

| Merkle 2014 | 67.0/64.0 | 78.0/84.0 | 73.7/86.8 | 41.4/79.2 | 20.2/23.6 |

| Park 2010 | 55.1/60.7 | 60.0/74.4 | 23.0/50.0 | 34.0/46.0 | 36.0/27.2 |

| Park 2020 | 61.8/62.7 | 76.0/77.0 | 54.3/51.3 | 42.3/40.0 | 29.7/27.7 |

| Thuijs 2019 | 65.2/65.0 | 76.0/79.0 | 69.0/64.0 | 79.0/77.0 | 4.00/5.00 |

PCI percutaneous coronary intervention, CABG coronary artery bypass grafting, HBP high blood pressure, DL dyslipidemia, CS current smoker

Main Results of this Analysis

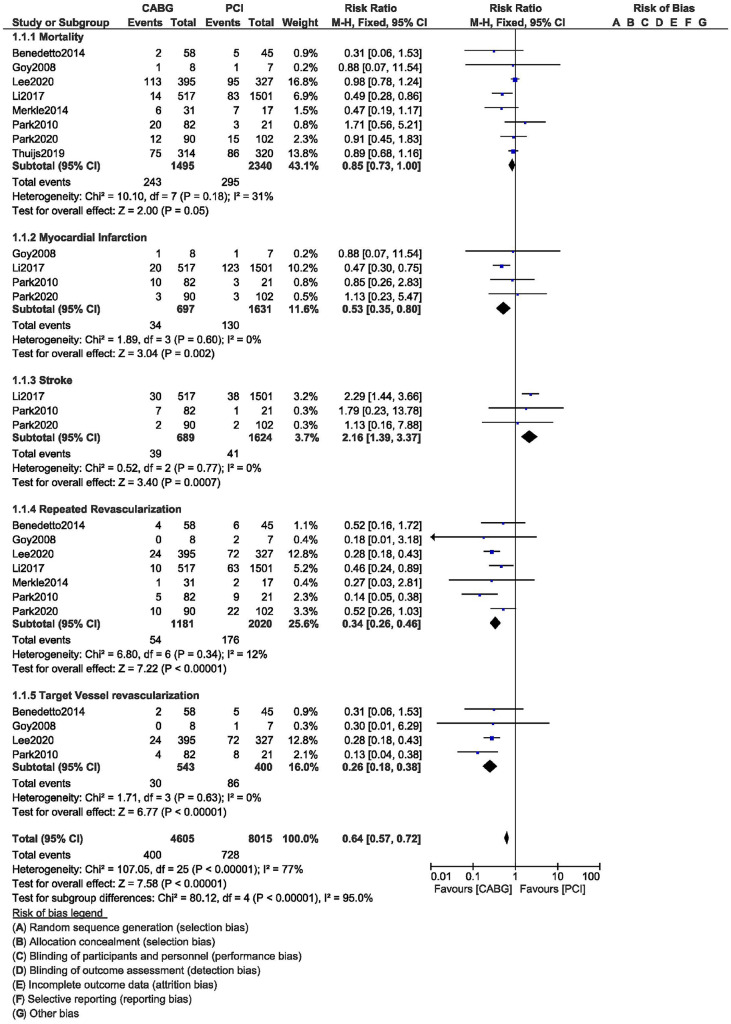

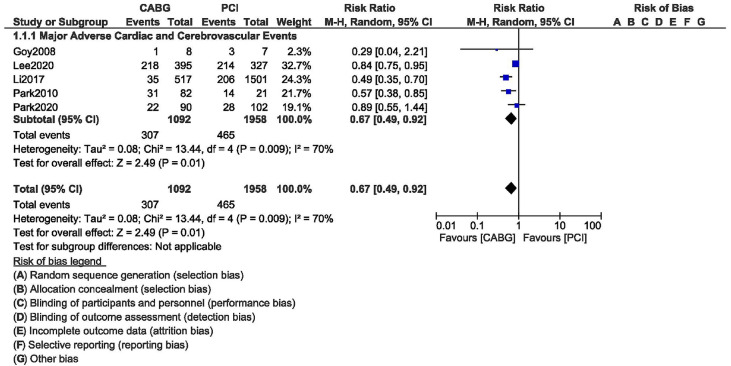

Results of this current analysis showed that, during this 10-year follow-up time period, mortality (RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.73–1.00; P = 0.05), MI (RR 0.53, 95% CI 0.35–0.80; P = 0.002), repeated revascularization (RR 0.34, 95% CI 0.26–0.46; P = 0.00001), and TVR (RR 0.26, 95% CI 0.18–0.38; P = 0.00001) were significantly higher with PCI when compared to CABG in these patients with T2DM as shown in Fig. 2. MACCEs were also significantly higher with PCI at 10 years (RR 0.67, 95% CI 0.49–0.92; P = 0.01) as shown in Fig. 3. However, CABG was associated with a significantly higher risk of stroke (RR 2.16, 95% CI 1.39–3.37; P = 0.0007) in these patients with T2DM at 10 years as shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Ten-year outcomes of PCI versus CABG in patients with T2DM and left main coronary disease

Fig. 3.

Ten-year major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events between PCI versus CABG in patients with T2DM and left main coronary disease

The results are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Results of this analysis

| Outcomes | RR with 95% CI | P value | I2 value (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality | 0.85 [0.73–1.00] | 0.05 | 31 |

| Myocardial infarction | 0.53 [0.35–0.80] | 0.002 | 0 |

| Stroke | 2.16 [1.39–3.37] | 0.0007 | 0 |

| MACCEs | 0.67 [0.49–0.92] | 0.01 | 70 |

| Repeated revascularization | 0.34 [0.26–0.46] | 0.00001 | 12 |

| Target vessel revascularization | 0.26 [0.18–0.38] | 0.00001 | 0 |

RR risk ratios, CI confidence intervals, MACCEs major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events

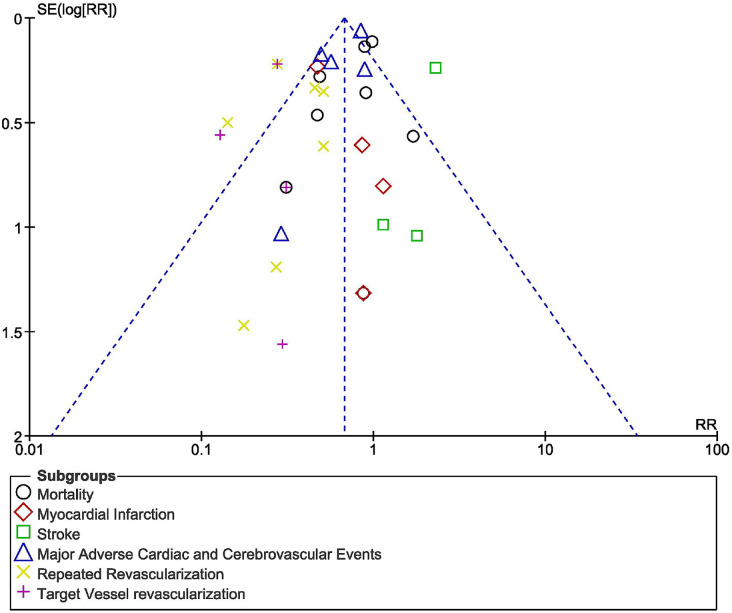

Sensitivity analysis led to consistent results throughout. There was little evidence of publication bias among the studies that assessed 10-year clinical outcomes between CABG and PCI according to visual assessment of the funnel plot shown in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Funnel plot for visualization of potential publication bias

Discussion

Currently available randomized and observational data comparing PCI with CABG for the treatment of LMCD lacks statistical power because of a limited number of patients. This analysis compared 10-year outcomes of PCI versus CABG in 3835 patients with T2DM suffering from LMCD.

A pooled analysis of individual patient-level data including patients with LMCD from the PRECOMBAT (Bypass Surgery Versus Angioplasty Using Sirolimus-Eluting Stent in Patients with Left Main Coronary Artery Disease) and SYNTAX (Synergy Between PCI with TAXUS and Cardiac Surgery) trials showed 5-year outcomes in 1305 participants to be similar, more specifically in mortality, MI, or stroke [24]. However, outcomes with even longer follow-up (10 years) were assessed in this current analysis.

Our current analysis showed that during a long-term follow-up time period of 10 years, CABG was associated with a significantly lower risk of mortality, MI, and repeated revascularization in patients with T2DM suffering from LMCD. However, it was associated with a significantly higher risk of stroke when compared to PCI.

Similarly, a recent meta-analysis comparing drug-eluting stents with CABG for patients with diabetes and LMCD showed that PCI was associated with a significantly higher risk of all-cause death, MI, and repeated revascularization compared to CABG [25]. In addition, similar to our current result, the study also showed CABG to be associated with a higher risk of stroke in these patients with T2DM.

Further supporting our current results, in another recently published meta-analysis based on patients with non-insulin-treated T2DM, the authors demonstrated CABG to be associated with significantly lower mortality rate, MI, repeated revascularization, and MACCEs in comparison to PCI for LMCD [26]. However, PCI was associated with a significantly lower risk of stroke when compared to CABG. When we classified T2DM according to insulin and non-insulin therapy, another meta-analysis based on patients with insulin-treated T2DM favored CABG with significantly lower mortality, MI, and MACCEs [27]. However, the patients were studied for a duration of only 1 year or more. The study also showed CABG to be associated with a higher stroke rate in comparison to PCI; however, even if their result was not statistically significant, this current result showed significant outcome for stroke during a longer follow-up time period of 10 years.

According to the Society of Thoracic Surgeons CABG Adult Cardiac Surgery Database (STS ACSD), there is a 1.3% incidence of stroke after CABG [28]. Our analysis showed CABG to be associated with a significantly increased risk of stroke in patients with T2DM. Several studies have shown cerebral atherosclerosis to be associated with a higher risk of post-CABG stroke [29]. Dyslipidemia in most of our participants could have resulted in undiagnosed cerebral atherosclerosis which might have finally increased the risk of stroke after CABG. Another reason for the occurrence of stroke after CABG could be due to the manipulation of the atherosclerotic aortic arch which could result in early embolism, thereby increasing the chances for stroke immediately after CABG [30]. Stresses including physical trauma and inflammation might trigger plaque rupture or platelet aggregation in patients with advanced atherosclerosis in the cervical and cranial vessels. Thus, stress post CABG might cause delayed embolism in patients with severe coronary artery disease [31]. Another reason for the increased in post-CABG stroke could be due to atrial fibrillation, MI, and coagulopathy after the surgery [30]. Moreover, CABG is indicated in severe coronary artery disease whereby PCI would not be useful, for example, in patients with severe LMCD, triple-vessel diseases, with associated conditions such as dialysis dependency, severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and so on [32]. Nevertheless, when on-pump and off-pump CABG were considered, an 11-year statewide analysis from New Jersey showed on-pump CABG to be associated with significantly higher stroke compared to off-pump CABG [33].

This meta-analysis is a pooled analysis comparing 10-year outcomes of CABG versus PCI in patients with T2DM and LMCD. Long-term outcomes of CABG versus PCI in patients with T2DM and LMCD have seldom been analyzed, and most of the previously published meta-analyses reported outcomes only for up to 5 years. Including a total number of 3835 participants with diabetes and LMCD, this analysis already shows a positive difference when compared to other respective original studies or other meta-analyses.

Limitations

This analysis also has limitations. First of all, the original studies which were included in this analysis consisted of patients with T2DM and different grades of CVD: stable coronary artery disease, acute coronary syndrome, coronary artery disease, and chronic kidney disease. However, all of the studies consisted of participants with LMCD. The duration of diabetes mellitus was not reported and this could be another limitation of this study. Another limitation was the fact that participants which were extracted from randomized trials and observational cohorts were both mixed together and analyzed. Also, one important outcome, more specifically stent thrombosis, was not reported in the original studies and therefore could not be assessed in our current analysis. Furthermore, because patients with T2DM were seldom classified into insulin-treated and non-insulin treated T2DM, we could not carry out any separate analysis based on 10-year outcomes in patients with or without insulin treatment in these patients. Finally, the effect and types of antidiabetic medications or the duration of antidiabetic drugs and their effects on the outcomes were ignored in this analysis.

Conclusions

During a long-term follow-up time period of 10 years, PCI was associated with worse clinical outcomes compared to CABG in these patients with T2DM suffering from LMCD. However, a significantly higher risk of stroke was observed with CABG. This piece of information might be vital in order to carefully choose and prevent complications following revascularization in such patients.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This study was supported by Guangxi Medical and Health Appropriate Technology Development and Promotion Application Project (S2017077) and the Guangxi Nanning Qingxiu District Science and Technology Development Project (Grant no. 2014S06). No Rapid Service Fee was received by the journal for the publication of this article.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Authorship Contributions

Dr HW, Dr HW, Dr YW, Dr XL, Dr VJ and Dr MAA were responsible for the conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the initial manuscript and revising it critically for important intellectual content. Dr HW wrote the final draft. All the authors approved the final manuscript as it has been written.

Disclosures

Hong Wang, Hongli Wang, Yuyuan Wei, Xinxin Li, Vineet Jhummun and Mohamad Anis Ahmed have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethical Guidelines

This meta-analysis is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. References of the original papers involving the data source which have been used in this paper have been listed in the main text of this current manuscript. All data are publicly available in electronic databases.

References

- 1.Kovacic JC, Castellano JM, Farkouh ME, Fuster V. The relationships between cardiovascular disease and diabetes: focus on pathogenesis. Endocrinol Metab Clin N Am. 2014;43(1):41–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2013.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Naito R, Miyauchi K. Coronary artery disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Int Heart J. 2017;58(4):475–480. doi: 10.1536/ihj.17-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leaman DM, Brower RW, Meester GT, Serruys P, van den Brand M. Coronary artery atherosclerosis: severity of the disease, severity of angina pectoris and compromised left ventricular function. Circulation. 1981;63(2):285–299. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.63.2.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Naito R, Kasai T. Coronary artery disease in type 2 diabetes mellitus: recent treatment strategies and future perspectives. World J Cardiol. 2015;7(3):119–124. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v7.i3.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bundhun PK, Pursun M, Teeluck AR, Bhurtu A, Soogund MZS, Huang W-Q. Adverse cardiovascular outcomes associated with coronary artery bypass surgery and percutaneous coronary intervention with everolimus eluting stents: a meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2016;6:35869. doi: 10.1038/srep35869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bundhun PK, Yanamala CM, Huang F. Percutaneous coronary intervention, coronary artery bypass surgery and the SYNTAX score: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2017;7:43801. doi: 10.1038/srep43801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li X, Kong M, Jiang D, Dong A. Comparing coronary artery bypass grafting with drug-eluting stenting in patients with diabetes mellitus and multivessel coronary artery disease: a meta-analysis. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2014;18(3):347–354. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivt509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Athappan G, Vinodhkumaradithyaa A, Srinivasan M, Jeyaseelan L, Ponniah T. Meta-analysis of 5-year outcomes of CABG vs PCI with stenting in patients with multivessel disease. Minerva Cardioangiol. 2008;56(5):453–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Rosa S, Polimeni A, Sabatino J, Indolfi C. Long-term outcomes of coronary artery bypass grafting versus stent-PCI for unprotected left main disease: a meta-analysis. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2017;17(1):240. doi: 10.1186/s12872-017-0664-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gao L, Liu Y, Sun Z, Wang Y, Cao F, Chen Y. Percutaneous coronary intervention using drug-eluting stents versus coronary artery bypass graft surgery in left main coronary artery disease an updated meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Oncotarget. 2017;8(39):66449–66457. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.20142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laukkanen JA, Kunutsor SK, Niemelä M, Kervinen K, Thuesen L, Mäkikallio TH. All-cause mortality and major cardiovascular outcomes comparing percutaneous coronary angioplasty versus coronary artery bypass grafting in the treatment of unprotected left main stenosis: a meta-analysis of short-term and long-term randomised trials. Open Heart. 2017;4(2):e000638. doi: 10.1136/openhrt-2017-000638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang J, Jiang T, Hou Y, et al. Five-year outcomes comparing percutaneous coronary intervention with drug-eluting stents versus coronary artery bypass grafting in patients with left main coronary artery disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Atherosclerosis. 2020;308:50–56. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2020.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Higgins JP, Altman DG. Assessing risk of bias in included studies. In: Higgins JP, Green S, editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Chichester: Wiley; 2008. p. 187–241.

- 14.Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle–Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25(9):603–605. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;21(339):b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benedetto U, Raja SG, Soliman RFB, et al. Minimally invasive direct coronary artery bypass improves late survival compared with drug-eluting stents in isolated proximal left anterior descending artery disease: a 10-year follow-up, single-center, propensity score analysis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;148(4):1316–1322. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.12.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goy J-J, Kaufmann U, Hurni M, et al. 10-year follow-up of a prospective randomized trial comparing bare-metal stenting with internal mammary artery grafting for proximal, isolated de novo left anterior coronary artery stenosis the SIMA (Stenting versus Internal Mammary Artery grafting) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52(10):815–817. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee K, Ahn J-M, Yoon Y-H, et al. Long-term (10-year) outcomes of stenting or bypass surgery for left main coronary artery disease in patients with and without diabetes mellitus. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(8):e015372. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.015372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li Y, Dong R, Hua K, et al. Outcomes of coronary artery bypass graft surgery versus percutaneous coronary intervention in patients aged 18–45 years with diabetes mellitus. Chin Med J (Engl) 2017;130(24):2906–2915. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.220305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Merkle J, Zeriouh M, Sabashnikov A, et al. Minimally invasive direct coronary artery bypass graft surgery versus percutaneous coronary intervention of the LAD: costs and long-term outcome. Perfusion. 2019;34(4):323–329. doi: 10.1177/0267659118820771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park D-W, Kim Y-H, Yun S-C, et al. Long-term outcomes after stenting versus coronary artery bypass grafting for unprotected left main coronary artery disease: 10-year results of bare-metal stents and 5-year results of drug-eluting stents from the ASAN-MAIN (ASAN Medical Center-Left MAIN Revascularization) Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56(17):1366–1375. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.03.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park D-W, Ahn J-M, Park H, et al. Ten-year outcomes after drug-eluting stents versus coronary artery bypass grafting for left main coronary disease: extended follow-up of the PRECOMBAT trial. Circulation. 2020;141(18):1437–1446. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.046039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thuijs DJFM, Kappetein AP, Serruys PW, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention versus coronary artery bypass grafting in patients with three-vessel or left main coronary artery disease: 10-year follow-up of the multicentre randomised controlled SYNTAX trial. Lancet. 2019;394(10206):1325–1334. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31997-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cavalcante R, Sotomi Y, Lee CW, et al. Outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention or bypass surgery in patients with unprotected left main disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68(10):999–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cui K, Lyu S, Song X, et al. Drug-eluting stent versus coronary artery bypass grafting for diabetic patients with multivessel and/or left main coronary artery disease: a meta-analysis. Angiology. 2019;70(8):765–773. doi: 10.1177/0003319719839885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang Y, Wen M, Zhou J, Chen Y, Zhang Q. Coronary artery bypass grafting versus percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with non-insulin treated type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2018. 10.1002/dmrr.2951. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Bundhun PK, Wu ZJ, Chen M-H. Coronary artery bypass surgery compared with percutaneous coronary interventions in patients with insulin-treated type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 6 randomized controlled trials. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2016;15:2. doi: 10.1186/s12933-015-0323-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.ElBardissi AW, Aranki SF, Sheng S, O'Brien SM, Greenberg CC, Gammie JS. Trends in isolated coronary artery bypass grafting: an analysis of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons adult cardiac surgery database. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;143:273–281. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gorelick P, Han J, Huang Y, et al. Epidemiology. In: Kim JS, Caplan LR, Wong KSL, et al., editors. Intracranial atherosclerosis. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell; 2008. pp. 33–44. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Selim M. Perioperative stroke. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:706–713. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra062668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scott J. Pathophysiology and biochemistry of cardiovascular disease. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2004;14:271–279. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2004.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shahian DM, O’Brien SM, Filardo G, et al. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons 2008 cardiac surgery risk models: part 1—coronary artery bypass grafting surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;88:S2–S22. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.05.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moreyra AE, Maniatis GA, Gu H, et al. Frequency of stroke after percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary artery bypass grafting (from an eleven-year statewide analysis) Am J Cardiol. 2017;119:197–202. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2016.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. References of the original papers involving the data source which have been used in this paper have been listed in the main text of this current manuscript. All data are publicly available in electronic databases.