Abstract

X-ray repair cross-complementing group 1 (XRCC1) plays a key role in the base excision repair pathway, as a scaffold protein that brings together proteins of the DNA repair complex. Several studies have reported contradictory results for XRCC1 exon 6 C>T (rs1799782) gene polymorphism and cancer risk in Indian population has provided inconsistent results. Therefore, we have performed this meta-analysis to evaluate the relationship between XRCC1 exon 6 C>T gene polymorphism and risk of cancer by published studies. We searched PubMed and Google scholar web databases to cover all studies published on association between XRCC1 exon 6 C>T gene polymorphism and cancer risk. The meta-analysis was carried out and pooled odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were used to appraise the strength of association. In order to derive a more precise estimation of the association, A total of 3197 confirmed cancer cases and 3819 controls were included from eligible seventeen case-controls studies. Results from overall pooled analysis demonstrated suggested that that variant allele (T vs. C: OR 1.301, 95% CI 1.003–1.688, p = 0.047) was associated with the risk of overall cancer. Other genetic models; heterozygous (TC vs. CC: OR 1.108, 95% CI 0.827–1.485, p = 0.491), homozygous (TT vs. CC: OR 1.479, 95% CI 0.877–2.493, p = 0.142), dominant (TT+TC vs. CC: OR 1.228, 95% CI 0.899–1.677, p = 0.196) and recessive (TT vs. TC+CC: OR 1.436, 95% CI 0.970–2.125, p = 0.071) did not reveal statistical association. Publication bias observation was also considered and none was detected during the analysis. The present meta-analysis suggested that the variant allele T of XRCC1 exon 6 gene polymorphism was associated with the risk of cancer. It is therefore pertinent to confirm this finding in a large sample size to divulge the mechanism of this polymorphism and cancer risk in Indian population.

Keywords: Cancer, DNA repair gene, Base excision repair pathway, Polymorphism, Meta-analysis, Indian population

Introduction

Cancer is still one of the most common dreadful disease across the world. New cases of virtually all types of cancer are rising and the burden of cancer in worldwide was estimated to have 18.1 million. new cases and 9.6 million. deaths in 2018 [1]. In India, cancer incidence is predicted to reach 1,148,757 cases in the year 2020 that may lead to a huge socio-economic burden [2]. The exact mechanism of initiation of cancer is still complicated because it is documented as a highly heterogeneous disease. Epidemiological studies have suggested the significant correlation between genetic factors and the risk of cancer [3]. Identification of genetic markers of cancer is essentially required which could be used clinically to predict the individual risk of progression and outcome. Recently genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have clearly revealed that single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) is the most common form of human genetic variation that play an important role in defining individual susceptibility to cancer [4]. Therefore, exploring genetic markers through genetic studies may assist in understanding the pathogenesis of carcinogenesis and may serve as a powerful tool of prevention and progression in future.

Human genome is constantly damaged by with endogenous and exogenous sources. Multiple DNA repair system exists to provide cellular defense mechanism against DNA damage exposure [5]. Evidence endorses cancer to be initiated by DNA damage, which if not repaired, can cause errors during DNA synthesis. Studies have suggested that inherited impairment due to genetic variant at one or more loci may altered individual’s DNA repair capacity and elevated the risk of developing cancer [6].

DNA repair gene involved in the base excision repair (BER) pathway, one of the main defense mechanisms, is generally considered to constitute the fundamental defense against small lesions such as single strand breaks (SSBs), non-bulky adducts, oxidative damage, alkylation, and methylation [7]. It has been well accepted that the SNPs in the base excision repair (BER) gene can change the individual repair capacity in response to DNA damage [8].

X-ray repair cross complementing group 1 (XRCC1) gene maps on chromosome 19q13.2 and play a key role in DNA repair involved in BER pathway [9]. XRCC1 acts as a scaffolding protein and interacts with enzymatic components of each stage of DNA strand break repair and involved to bring together poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP), DNA ligase III, and DNA polymerase β via its various domain and polynucleotide kinase at the site of DNA damage [10, 11].

Studies have demonstrated that the ability of DNA-repair genes (such as XRCC1) is correlated with the pathogenesis of malignant tumors and drug resistance [12]. Several polymorphisms have been identified in XRCC1 gene, among them one common genetic variant contributing to amino acid substitutions in XRCC1 at codon 194 (exon 6, base C>T, amino acid Arg to Trp, rs1799782) occurs at a conserved residue in humans have been studied widely [13]. Functional significance of XRCC1 exon 6 C>T is mainly due to its location in an evolutionarily conserved linker region. keeping in mind the significant role of XRCC1 gene in DNA repair and mutation, several studies have investigated the association between XRCC1 exon 6 C>T polymorphism and various cancer risk in Indian populations. However, individual published studies reveal inconclusive results [14–30]. It is possible that discrepancies in findings result from individual studies may have been underpowered to detect overall effects. With an aim of addressing inconsistencies in the findings of these individual studies, we performed a meta-analysis based on published studies to obtain better conclusion of the postulated genetic association between the XRCC1 exon 6 C>T and susceptibility to cancer in Indian population.

Materials and Methods

Identification and Eligibility of Studies

A series of literature search was performed in PubMed (Medline) and Google scholar database to identify studies that had investigated the association of XRCC1 exon 6 C>T polymorphism and cancer risk in Indian population, last updated searched was performed on June 2019. The following medical subject headings were used as key word for our search: “XRCC1 OR X-ray repair cross complementing group 1” and “polymorphism OR mutation OR variant” and “Cancer OR malignancy OR tumor” and “Indian OR India”. The search was focused on studies that had been carried out in humans. In addition, references of retrieved articles were also screened for other additional eligible studies.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria for this meta-analysis were the following: (1) must evaluated the association between XRCC1 exon 6 C>T polymorphism and cancer risk, (2) use a case–control design, (3) recruited histologically confirmed cancer patients and healthy controls, (4) Provided complete genotype distribution of case and control. In addition, the following exclusion criteria were used: (1) repeated or overlapping studies, (2) case only studies, (3) review articles, (4) animal studies, (5) no usable data reported.

Data abstraction and Quality Assessment

The data were abstracted using a standardized protocol of inclusion and exclusion criteria. The following data were extracted from each study: last name of the first author, publication year, study region, types of cancer, sample size of case and controls, genotype frequencies in both cases and controls and source of genotyping.

Statistical Analysis

Pooled odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated to assess the associations between XRCC1 exon 6 C>T gene polymorphism and cancer risk under the allele, heterozygous, homozygous, dominant, and recessive models [31]. Statistical heterogeneity between studies was performed by the chi-square-based Q-test [32]. Heterogeneity was considered significant at p value < 0.05, to avoid underestimation of the presence of heterogeneity. If p value (> 0.05) it means heterogeneity exists across articles, and random effects model (Mantel–Haenszel method) was used to measure the pooled OR; otherwise the fixed effects model (Mantel–Haenszel method) was used [33, 34]. Moreover, I2 statistics was also employed to efficiently test the heterogeneity. The degree of heterogeneity was expressed as I 2 and was divided into low (I2< 25%), medium (I2 ~ 50%), and high (I2 > 75%) heterogeneity groups. I2 > 50% was regarded as indicating substantial heterogeneity [35]. Potential publication bias was estimated by Begg’s tests and Egger’s test [36, 37]. p value < 0.05 was considered as representation of statistically significant publication bias. Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) was also tested in the control group, which was measured via chi-square test. A sensitivity analysis was conducted to test the impact of removing each single study on the pooled result. The statistical analysis involved in this meta-analysis was performed by Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (CMA) Version 2 software program (Biostat Inc., USA). All p values were two sided and statistical significance level was considered as p value < 0.05 for this meta-analysis.

Results

Description of Literature Search

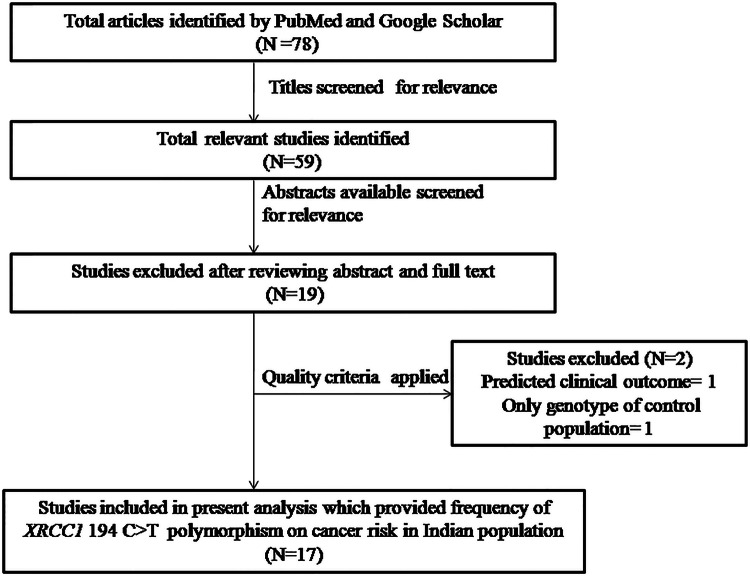

We identified a total of seventy eight studies by scrupulous literature search from the PubMed (Medline) and Google scholar. All retrieved articles were carefully examined according the preset selection (inclusion–exclusion) criteria. Finally, after reading the abstracts and the full texts, a total of seventeen research articles were included in the meta-analysis (Fig. 1). Furthermore, studies either showing XRCC1 polymorphism to predict survival OR as an indicator for response to therapy of patients were excluded straightaway. Similarly, research articles investigating the levels of XRCC1 mRNA or protein expression and relevant review articles were also excluded. Details of eligible studies, cancer types, publication year, distribution of genotypes and minor allele frequency (MAF) in the controls and cases have shown been shown in Tables 1 and 2.

Fig. 1.

Prisma flow diagram for inclusion and exclusion of studies in the meta-analysis on XRCC1 exon 6 C>T gene polymorphism

Table 1.

Main characteristics of all published studies included in the meta-analysis

| References | Cancer | Association | Control | Cases | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maqbool et al. [14] | Skin | Yes | 60 | 68 | Blood |

| Pavithra et al. [15] | Gastric | No | 400 | 200 | Blood |

| Konathala et al. [16] | Cervical | NM | 150 | 125 | Blood |

| Devi et al. [17] | Breast | No | 534 | 464 | Blood |

| Singh et al. [18] | Lung | No | 325 | 330 | Blood |

| Ghosh et al. [19] | Gastric | No | 82 | 70 | Blood |

| Bajpai et al. [20] | Cervical | Increased | 68 | 65 | Blood, Tissue |

| Annamaneni et al. [21] | CML | Increased | 350 | 350 | Blood |

| Kumar et al. [22] | SCCHN | Reduced | 278 | 278 | Blood |

| Mittal et al. [23] | Bladder | No | 250 | 212 | Blood |

| Mittal et al. [23] | Prostate | No | 250 | 195 | Blood |

| Srivastava et al. [24] | Gallbladder | No | 204 | 173 | Blood |

| Kiran et al. [25] | Hepatocellular carcinoma | Increased | 171 | 63 | Blood |

| Mitra et al. [26] | Breast | Reduced | 225 | 151 | Blood |

| Pachouri et al. [27] | Lung | Increased | 122 | 103 | Blood |

| Ramachandran et al. [28] | Oral | Increased | 110 | 110 | Blood |

| Joseph et al. [29] | Leukemia | Increased | 117 | 117 | Blood |

| Chacko et al. [30] | Breast | Increased | 123 | 123 | Blood |

NM not mentioned, CML chronic myeloid leukemia

Table 2.

Genotypic distribution of XRCC1 exon 6 C>T gene polymorphism included in meta-analysis

| References | Controls | Cancer cases | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype | Minor allele | Genotype | Minor allele | HWE | |||||

| CC | CT | TT | MAF | CC | CT | TT | MAF | p value | |

| Maqbool et al | 44 | 11 | 5 | 0.17 | 36 | 20 | 12 | 0.32 | 0.004 |

| Pavithra et al | 303 | 90 | 7 | 0.13 | 158 | 40 | 2 | 0.11 | 0.915 |

| Konathala et al | 40 | 85 | 25 | 0.45 | 82 | 36 | 7 | 0.20 | 0.076 |

| Devi et al | 338 | 166 | 30 | 0.21 | 263 | 178 | 23 | 0.24 | 0.114 |

| Singh et al | 267 | 55 | 3 | 0.09 | 256 | 72 | 2 | 0.11 | 0.928 |

| Ghosh et al | 58 | 24 | 0 | 0.14 | 50 | 14 | 6 | 0.18 | 0.120 |

| Bajpai et al | 44 | 11 | 13 | 0.27 | 11 | 16 | 38 | 0.70 | 0.001 |

| Annamaneni et al | 7 | 113 | 230 | 0.81 | 12 | 81 | 257 | 0.85 | 0.103 |

| Kumar et al | 121 | 131 | 26 | 0.32 | 144 | 111 | 23 | 0.28 | 0.263 |

| Mittal et al | 207 | 41 | 2 | 0.09 | 172 | 37 | 3 | 0.10 | 0.984 |

| Mittal et al | 203 | 43 | 4 | 0.10 | 157 | 29 | 9 | 0.12 | 0.334 |

| Srivastava et al | 162 | 40 | 2 | 0.10 | 145 | 26 | 2 | 0.08 | 0.786 |

| Kiran et al | 27 | 64 | 52 | 0.58 | 8 | 43 | 12 | 0.53 | 0.359 |

| Mitra et al | 6 | 53 | 166 | 0.85 | 2 | 15 | 134 | 0.93 | 0.481 |

| Pachouri et al | 52 | 47 | 23 | 0.38 | 40 | 39 | 24 | 0.42 | 0.042 |

| Ramachandran et al | 90 | 19 | 1 | 0.09 | 66 | 37 | 7 | 0.23 | 0.997 |

| Joseph et al | 91 | 22 | 4 | 0.12 | 77 | 32 | 8 | 0.20 | 0.085 |

| Chacko et al | 96 | 23 | 4 | 0.12 | 79 | 35 | 9 | 0.21 | 0.093 |

MAF minor allele frequency, HWE Hardy Weinberg equilibrium

Publication Bias

Publication bias was detected based on the symmetry of funnel plot and Begg’s and Egger’s tests. The shape of funnel plot did not elucidate any obvious asymmetry in all of the comparison models. Egger’s regression test, a linear regression approach for measuring funnel plot on the natural logarithm scale of the OR was used to provide statistical evidence to the funnel plot symmetry that also showed no evidence of publication bias (Table 3).

Table 3.

Statistics to test publication bias and heterogeneity in meta-analysis XRCC1 exon 6 C>T polymorphism

| Comparisons | Egger’s regression analysis | Heterogeneity analysis | Model used for meta-analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 95% confidence interval | p value | Q value | Pheterogeneity | I2 (%) | ||

| T Vs C | 3.43 | − 0.91–7.77 | 0.11 | 133.47 | 0.01 | 87.26 | Random |

| TT vs CC | 1.48 | − 0.94–3.92 | 0.21 | 66.80 | 0.01 | 74.55 | Random |

| TC vs CC | 0.50 | − 2.44–3.46 | 0.72 | 83.68 | 0.01 | 79.68 | Random |

| TT+TC vs CC | 1.43 | − 1.96–4.84 | 0.38 | 107.61 | 0.01 | 84.20 | Random |

| TT vs TC+CC | 0.49 | − 1.35–2.34 | 0.57 | 57.76 | 0.01 | 70.57 | Random |

Evaluation of Heterogeneity

For each genetic contrast, we estimated the between study heterogeneity across all of the eligible comparisons using Q-test and I2 statistics. Heterogeneity was observed in all genetic models, i.e., ***allele (T vs. C), homozygous (TT vs. CC), heterozygous (TC vs. CC), dominant (TT+TC vs. CC) and recessive (TT vs. TC+CC). Thus, random effect model was applied to synthesize the data for above these models (Table 3).

Association of XRCC1 exon 6 C>T Gene Polymorphism and Overall Cancer Susceptibility

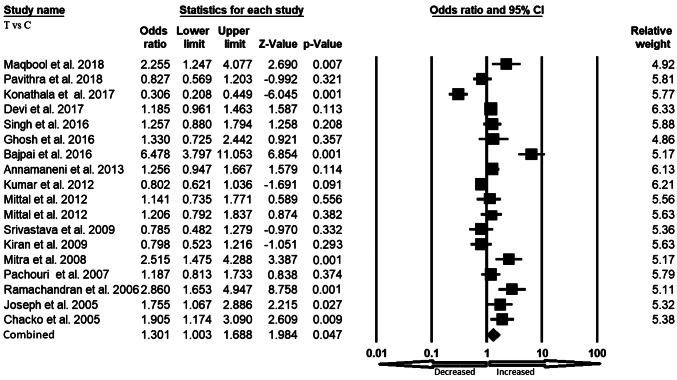

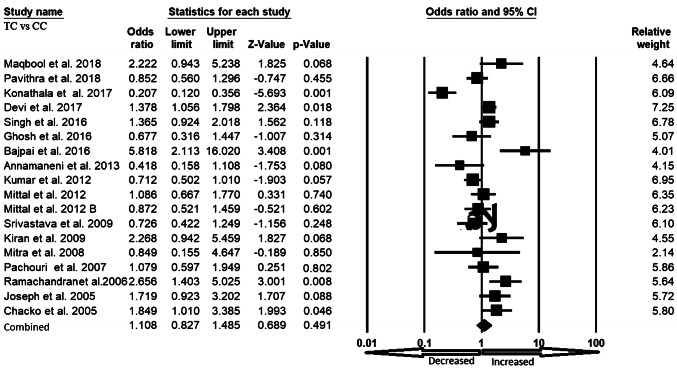

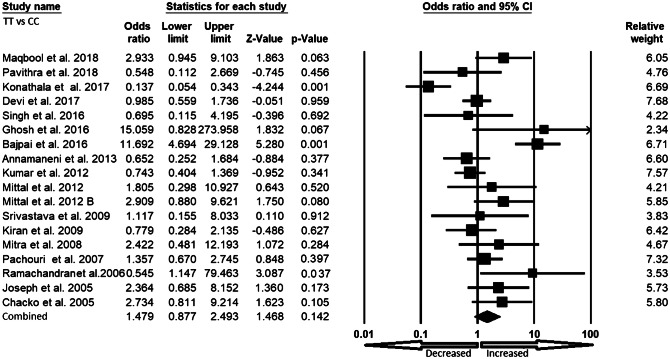

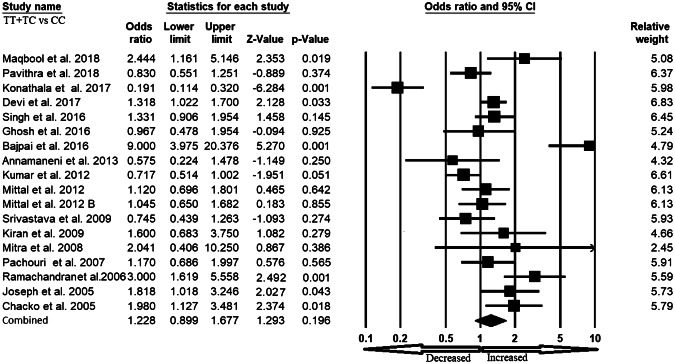

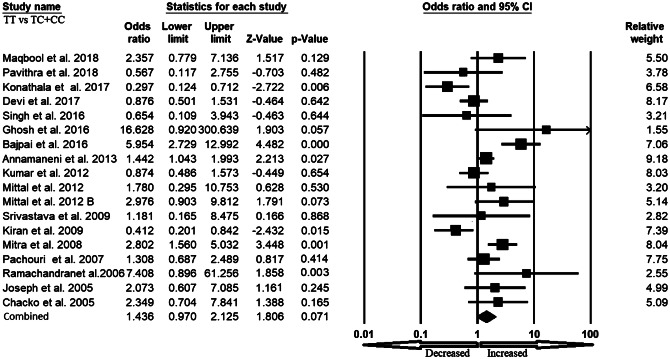

We pooled all seventeen studies together and included 3197 confirmed cases and 3819 controls to evaluate the relationship between the XRCC1 exon 6 C>T gene polymorphism and the risk of overall cancer. In a random model, pooled analysis revealed that variant allele (T vs. C: OR 1.301, 95% CI 1.003–1.688, p = 0.047) was associated with the risk of overall cancer. However, heterozygous (TC vs. CC: OR 1.108, 95% CI 0.827–1.485, p = 0.491), homozygous (TT vs. CC: OR 1.479, 95% CI 0.877–2.493, p = 0.142), dominant (TT+TC vs. CC: OR 1.228, 95% CI 0.899–1.677, p = 0.196) and recessive (TT vs. TC+CC: OR 1.436, 95% CI 0.970–2.125, p = 0.071) genetic models did not indicate statistical association (Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6).

Fig. 2.

Forest plot of allele (T vs. C) model for overall cancer risk. The squares and horizontal lines correspond to the study specific OR and 95% CI

Fig. 3.

Forest plot of heterozygous (TC vs. CC) model for overall cancer risk. The squares and horizontal lines correspond to the study specific OR and 95% CI

Fig. 4.

Forest plot of homozygous (TT vs. CC) model for overall cancer risk. The squares and horizontal lines correspond to the study specific OR and 95% CI

Fig. 5.

Forest plot of dominant (TT+TC vs. CC) model for overall cancer risk. The squares and horizontal lines correspond to the study specific OR and 95% CI

Fig. 6.

Forest plot of recessive (TT vs. TC+CC) model for overall cancer risk. The squares and horizontal lines correspond to the study specific OR and 95% CI

Sensitivity Analysis

Sensitivity analyses were performed by removing one individual study sequentially from the analysis at a time to evaluate the stability of the present meta-anlaysis. The results showed that no single study can significantly affect pooled OR before and after exclusion of the study (Figure not shown). Hence the result of the present meta-analysis is relatively stable.

Discussion

Currently, new biomarkers in genetics and molecular biology have gradually become important monitoring indicators in cancer prevention and early diagnosis and treatment. DNA repair mechanisms that are important factor in maintaining genomic stability of human genome is gradually being recognized as clues to individual’s susceptibility for cancer. It is therefore important to understand the mechanisms underlying the effects of genetic variants in DNA repair genes resulting in cancer susceptibility, which could be crucial to understand the molecular pathogenesis involved in cancer. From a clinical and scientific perspective, SNPs are potential biomarker for diagnostic and therapeutic in cancer.

BER is a versatile DNA repair system that eradicates a wide range of DNA lesions including endogenous DNA lesions as well as damages produced during episodes of inflammation and exposures to ionizing radiation or a variety of chemical carcinogen including UV-induced lesions [38]. Studies have reported a XRCC1 deletion mutation in null homozygous mice is embryonic lethal [39]. XRCC1 has two BRCA1 carboxyl-terminal (BRCT) domains (BRCT1 and BRCT2), located centrally and at the C-terminal end, respectively. BRCT2 is responsible for binding and stabilizing DNA ligase III and is required for single-strand breaks and gaps repair (SSBR), specifically during the G0/G1 phases of the cell cycle [40]. The centre of BRCT1 domain binds to and down-regulates the single-strand breaks and gaps recognition protein PARP1 and is required for efficient SSBR during both G1 and S/G2 phases of the cell cycle.

Based on the consideration of biological functions of XRCC1 exon 6 C>T. we undertook the present study to clarify the role played by the XRCC1 exon 6 C>T gene polymorphism in cancer among Indian population. Meta-analysis is a useful tool to summarizing inconsistent results from different studies because it increases sample size and statistical power and resolve discrepancy in genetic association studies [41, 42]. To our knowledge, this study is the first study which providing combined data on XRCC1 exon 6 C>T genetic variant and overall cancer risk of Indian population. The associations for the allele contrast, homozygous, heterozygous, dominant and recessive model were examined. After rigorous statistical analysis, we detected that individuals harboring variant allele of XRCC1 exon 6 C>T polymorphism might have an increased risk of cancer. It may biologically plausible that the T allele result in amino acid substitutions and henceforth may modify the wild-type protein function and alter cellular ability to repair endogenous and exogenous DNA damage, supporting to disease susceptibility. Studies reported that the SNPs in BER gene can change the individual repair capacity in response to DNA damage and modulate cancer risk [43]. Although, cancer is a complicated multi–genetic disease, a single genetic variant is usually inadequate to predict the risk of this deadly disease [44].

We have taken considerable effort and resources into testing possible association between XRCC1 exon 6 C>T gene polymorphisms and overall cancer risk, there are still some limitations in this meta-analysis. Heterogeneity is an important issue while interpreting the results of meta-analysis, although, it can be minimized by applying random-effects model [45]. In the present study we detected inter-study heterogeneity. The source of heterogeneity may arise possibly due to regional lifestyle varied among populations from different parts of India [46], another point could be recruitment of control subjects. Gene environment interaction and adjusted OR have not been performed due to the limited number of data.

The current meta-analysis suggested some key advantages in several aspects. (1) Funnel plot and Egger linear regression in the present meta-analyses indicated that the whole pooled result is unbiased. (2) Substantial number of cases and controls being pooled from different studies, significantly increased statistical power of the analysis. (3) the quality of case–control studies included in current meta-analysis was good and met our inclusion criterion. And lastly sensitivity analysis also showed that the results were robust and were not influenced by any single study.

In summary, the research of the association of XRCC1 exon 6 C>T gene polymorphism is very prevalent but conflicting simultaneously presently for Indian population. Our meta-analysis suggested that XRCC1 exon 6 C>T variant play a role in the overall cancer risk in Indian population. Further, public-health implications of our finding should be carefully considered. However, replicative studies with larger sample size are desirable to authenticate the risk associated with this variant allele of DNA repair as potential contributors to cancer risk.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takiar R, Nadayil D, Nandakumar A. Projections of number of cancer cases in India (2010–2020) by cancer groups. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2010;11:1045–1049. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pharoah PD, Dunning AM, Ponder BA, Easton DF. Association studies for finding cancer-susceptibility genetic variants. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:850–860. doi: 10.1038/nrc1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lichtenstein P, Holm NV, Verkasalo PK, Iliadou A, Kaprio J, Koskenvuo M, Pukkala E, Skytthe A, Hemminki K. Environmental and heritable factors in the causation of cancer-analyses of cohorts of twins from Sweden, Denmark, and Finland. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:78–85. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200007133430201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Friedberg EC. DNA damage and repair. Nature. 2003;421:436–440. doi: 10.1038/nature01408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bernstein C, Bernstein H, Payne CM, Garewal H. DNA repair/pro-apoptotic dual-role proteins in five major DNA repair pathways: fail-safe protection against carcinogenesis. Mutat Res. 2002;511:145–178. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5742(02)00009-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wood RD, Mitchell M, Sgouros J, Lindahl T. Human DNA repair genes. Science. 2001;291:1284–1289. doi: 10.1126/science.1056154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tudek B. Base excision repair modulation as a risk factor for human cancers. Mol Aspe Med. 2007;28:258–275. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caldecott KW. XRCC1 and DNA strand break repair. DNA Repair (Amst) 2003;2:955–969. doi: 10.1016/s1568-7864(03)00118-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Whitehouse CJ, Taylor RM, Thistlethwaite A, Zhang H, Karimi-Busheri F, Lasko DD, Weinfeld M, Caldecott KW. XRCC1 stimulates human polynucleotide kinase activity at damaged DNA termini and accelerates DNA single-strand break repair. Cell. 2001;104:107–117. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00195-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caldecott KW, Aoufouchi S, Johnson P, Shall S. XRCC1 polypeptide interacts with DNA polymerase beta and possibly poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase, and DNA ligase III is a novel molecular ‘nick-sensor’ in vitro. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:4387–4394. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.22.4387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kirschner K, Melton DW. Multiple roles of the ERCC1-XPF endonuclease in DNA repair and resistance to anticancer drugs. Anticancer Res. 2010;30:3223–3232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shen MR, Jones IM, Mohrenweiser H. Nonconservative amino acid substitution variants exist at polymorphic frequency in DNA repair genes in healthy humans. Cancer Res. 1998;58:604–608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maqbool R, Amin S, Majeed S, Bhat A, Rasool SA, Nabi M. XRCC1 Arg194Trp polymorphism is no risk factor for skin cancer development in Kashmiri population. Egypt J Med Hum Genet. 2018;19:9–95. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pavithra D, Gautam M, Rama R, Swaminathan R, Gopal G, Ramakrishnan AS, Rajkumar T. TGFβ C-509T, TGFβ T869C, XRCC1 Arg194Trp, IKBα C642T, IL4 C-590T genetic polymorphisms combined with socio-economic, lifestyle, diet factors and gastric cancer risk: a case control study in South Indian population. Cancer Epidemiol. 2018;53:21–26. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2018.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Konathala G, Mandarapu R, Godi S. Data on polymorphism of XRCC1 and cervical cancer risk from South India. Data Brief. 2016;10:11–13. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2016.11.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Devi KR, Ahmed J, Narain K, Mukherjee K, Majumdar G, Chenkual S, Zonunmawia JC. DNA repair mechanism gene, XRCC1A (Arg194Trp) but not XRCC3 (Thr241Met) polymorphism increased the risk of breast cancer in premenopausal females: a case-control study in northeastern region of India. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2017;16:1150–1159. doi: 10.1177/1533034617736162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh A, Singh N, Behera D, Sharma S. Association and multiple interaction analysis among five XRCC1 polymorphic variants in modulating lung cancer risk in North Indian population. DNA Repair (Amst) 2016;47:30–41. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2016.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghosh S, Ghosh S, Bankura B, Saha ML, Maji S, Ghatak S, Pattanayak AK, Sadhukhan S, Guha M, Nachimuthu SK, Panda CK, Maity B, Das M. Association of DNA repair and xenobiotic pathway gene polymorphisms with genetic susceptibility to gastric cancer patients in West Bengal. India Tumour Biol. 2016;37:9139–9149. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-4780-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bajpai D, Banerjee A, Pathak S, Thakur B, Jain SK, Singh N. Single nucleotide polymorphisms in the DNA repair genes in HPV-positive cervical cancer. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2016;25:224–231. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0000000000000159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Annamaneni S, Gorre M, Kagita S, Addepalli K, Digumarti RR, Satti V, Battini MR. Association of XRCC1 gene polymorphisms with chronic myeloid leukemia in the population of Andhra Pradesh. India Hematol. 2013;18:163–168. doi: 10.1179/1607845412Y.0000000040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumar A, Pant MC, Singh HS, Khandelwal S. Associated risk of XRCC1 and XPD cross talk and life style factors in progression of head and neck cancer in north Indian population. Mutat Res. 2012;729:24–34. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mittal RD, Mandal RK, Gangwar R. Base excision repair pathway genes polymorphism in prostate and bladder cancer risk in North Indian population. Mech Ageing Dev. 2012;133:127–132. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Srivastava A, Srivastava K, Pandey SN, Choudhuri G, Mittal B. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms of DNA repair genes OGG1 and XRCC1: association with gallbladder cancer in North Indian population. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:1695–1703. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0354-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kiran M, Saxena R, Chawla YK, Kaur J. Polymorphism of DNA repair gene XRCC1 and hepatitis-related hepatocellular carcinoma risk in Indian population. Mol Cell Biochem. 2009;327:7–13. doi: 10.1007/s11010-009-0035-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mitra AK, Singh N, Singh A, Garg VK, Agarwal A, Sharma M, Chaturvedi R, Rath SK. Association of polymorphisms in base excision repair genes with the risk of breast cancer: a case-control study in North Indian women. Oncol Res. 2008;17:127–135. doi: 10.3727/096504008785055567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pachouri SS, Sobti RC, Kaur P, Singh J. Contrasting impact of DNA repair gene XRCC1 polymorphisms Arg399Gln and Arg194Trp on the risk of lung cancer in the north-Indian population. DNA Cell Biol. 2007;26:186–191. doi: 10.1089/dna.2006.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramachandran S, Ramadas K, Hariharan R, Rejnish Kumar R, Radhakrishna PM. Single nucleotide polymorphisms of DNA repair genes XRCC1 and XPD and its molecular mapping in Indian oral cancer. Oral Oncol. 2006;42:350–362. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Joseph T, Kusumakumary P, Chacko P, Abraham A, Pillai MR. DNA repair gene XRCC1 polymorphisms in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Lett. 2005;217:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.06.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chacko P, Rajan B, Joseph T, Mathew BS, Pillai MR. Polymorphisms in DNA repair gene XRCC1 and increased genetic susceptibility to breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2005;89:15–21. doi: 10.1007/s10549-004-1004-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Woolf B. On estimating the relation between blood group and disease. Ann Hum Genet. 1955;19:251–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.1955.tb01348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu R, Li B. A multiplicative-epistatic model for analyzing interspecific differences in outcrossing species. Biometrics. 1999;2:355–365. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.1999.00355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mantel N, Haenszel W. Statistical aspects of the analysis of data from retrospective studies of disease. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1959;4:719–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50:1088–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta- analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wallace SS, Murphy DL, Sweasy JB. Base excision repair and cancer. Cancer Lett. 2012;327:73–89. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.12.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tebbes RS, Flannery ML, Meneses JJ, Hartmann A, Tucker JD, Thompson LH, Cleaver JE, Pedersen RA. Requirement for the Xrcc1 DNA base excision repair gene during early mouse development. Dev Biol. 1999;208:513–529. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moore DJ, Taylor RM, Clements P, Caldecott KW. Mutation of a BRCT domain selectively disrupts DNA single-strand break repair in noncycling Chinese hamster ovary cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:13649–13654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.250477597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lohmueller KE, Pearce CL, Pike M, Lander ES, Hirschhorn JN. Meta-analysis of genetic association studies supports a contribution of common variants to susceptibility to common disease. Nat Genet. 2003;33:177–182. doi: 10.1038/ng1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mandal RK, Mittal RD. Genetic variant Arg399Gln G%3eA of XRCC1 DNA repair gene enhanced cancer risk among Indian population: evidence from meta-analysis and trial sequence analyses. Indian J Clin Biochem. 2018;33:262–272. doi: 10.1007/s12291-017-0669-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tudek B. Base excision repair modulation as a risk factor for human cancers. Mol Asp Med. 2007;28:258–275. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100:57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Munafò MR, Flint J. Meta-analysis of genetic association studies. Trends Genet. 2004;20:439–444. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2004.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Indian Genome Variation Consortium Genetic landscape of the people of India: a canvas for disease gene exploration. J Genet. 2008;87:3–20. doi: 10.1007/s12041-008-0002-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]