Abstract

Ovarian cancer has been emerged as a most common and lethal gynecological malignancy in India. High serum insulin and low adiponectin have been associated with increased risk of ovarian cancer. But their role in development of ovarian cancer is conflicting and little evidence is available. We aimed to evaluate blood levels of insulin and adiponectin in epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) patients and their association with the risk to develop EOC. The study included following three groups; Group 1: fifty cases of cytohistopathologically confirmed cases of EOC, Group 2: fifty age matched cases of benign ovarian conditions and Group 3: fifty ages matched healthy controls with no evidence of any benign or malignant ovarian pathology as ruled out by clinical examination and relevant investigations. Cytohistopathologically confirmed and newly diagnosed cases of EOC and benign ovarian cancer were included in this study. The median value of fasting serum insulin was significantly high (15.0 µlU/ml, P = 0.02) and adiponectin were significantly low (5.1 µg/ml, P < 0.001) in ovarian cancer patients compared to benign ovarian tumors and healthy controls group. A significant increase risk of ovarian cancer was found in high tertile (≥ 18.7 µlU/ml) of serum insulin level (OR = 2.7; 95% CI = 1.00–6.67, P = 0.04) and lower tertile (≤ 5.45 µg/ml) of adiponectin level (OR = 3.2; 95% CI = 1.10–9.71, P = 0.03). High serum insulin level and low adiponectin levels were significantly associated with increased risk for development of ovarian cancer.

Keywords: Ovarian cancer, Hyperinsulinemia, Hypoadiponectinemia, Non-diabetic women

Introduction

Ovarian cancer is the third most common gynecological malignancy after breast and cervix in India according to National Cancer Registry Programme (NCRP) report [1]. It is also a leading cause of death among gynecological malignancy as it caused around 14,000 deaths every year globally [2]. Overall survival rate remains around less than 30% as 70% cases diagnosed at advanced stage with metastasis which have unfavorable prognosis [3]. Intrinsic molecular heterogeneity during tumorigenesis causes development of heterogeneous ovarian cancer with different histological type and different clinical presentation, etiology and prognosis [4]. Epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) involves most common (around 90%) ovarian tumor [5]. Due to frequent drug resistance and relapse, still survival rate remains low despite availability of standard therapy [6]. There is a need to understand pathogenesis of ovarian cancer development which help in identification of blood marker for early diagnosis ovarian cancer and further improves clinical outcome.

Obesity and longevity are proven major risk factors of ovarian cancer [7]. Obesity cause hyperinsulinemia or insulin resistance, variations in circulating levels of adipokines, chronic low grade inflammation and abnormalities in insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-I). All these mechanisms in obesity increases risk of cancer development [8, 9]. Adiponectin is a major adipokines secreted by adipose tissue and it has anti-apoptotic, anti-inflammatory and anti-angiogenesis properties. Adiponectin has been associated with decreased risk of various cancer development like endometrial, breast and colon by diminishing the growth, angiogenesis and invasiveness of cancer cells. But some in vitro study reported that adiponectin promotes the oncogenesis [10]. Thus adiponectin can be acts as a tumor-suppressing or tumor-promoter, depending upon environmental factor like inflammatory state and type of organ or tissues [11].

Insulin resistance causes hyperinsulinemia and signal transduction through IGF-1 receptor, result in cancer development and metastasis by cell proliferation and by suppressing apoptosis [12]. High circulating insulin level has been associated with increased risk of rectum, endometrium and colon cancer [13]. Hyperinsulinemia has been found to be associated with increased risk of ovarian cancer particularly in post menopausal women [14].

Thus role of adiponectin in development of ovarian cancer is conflicting and little evidence is available. Based on above background, objective of this study is to evaluate blood levels of adiponectin and insulin in EOC patients and their association with the risk to develop EOC.

Materials and Methods

The study has been carried out in Department of Biochemistry and Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Maulana Azad Medical College and associated Lok Nayak Hospital, New Delhi.

Study Population

The study included following three groups; Group 1: Fifty cases of cytohistopathologically confirmed cases of EOC, Group 2: Fifty age matched cases of benign ovarian conditions and Group 3: age matched healthy controls with no evidence of any benign or malignant ovarian pathology as ruled out by clinical examination and relevant investigations. Patients diagnosed with non-malignant ovarian conditions on cytohistopathologically examination of the biopsy samples were included in group 2. All the study participants were adjusted for alcohol drinking, BRCA gene mutation and cigarette smoking. Well deigned questionnaire format was used to collect medical lifestyle, reproductive and demographic information from all the study participants. The detailed history of ovarian cancer and clinical examination were taken along with anthropometric measurements. Staging of cancer was done according to International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging system. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Inclusion Criteria

Cytohistopathologically confirmed and newly diagnosed cases of EOC and benign ovarian cancer were included in this study.

Exclusion Criteria

Study participants present with malignancies other than ovarian cancer, metastasized cancer from other site, past history of any other cancer, on steroid therapy, chronic inflammatory diseases and pre existing diabetes mellitus were excluded from the study.

Blood Sample Collection and Analysis

Five ml of venous blood was taken after 10–12 h overnight fast from antecubital vein by venepuncture following universal standard precaution from all study participants. Adiponectin was measured by commercially available kit of Biovendor Research and Diagnostic Products based on sandwich ELISA principle. Insulin was measured by Insulin kit on ELECSYS 2010 of Roche Diagnostic based on electrochemiluminescence principle.

Statistical Analysis

SPSS PC version 17 was used to analyze all data. Mean and standard deviation (SD) were used for non-skewed data and median and range were used for skewed data. One way ANOVA and Kruskal Wallis test were used to find difference between mean and median respectively. Odds ratio with its 95% CI was used to evaluate risk factor. P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Table 1 depicts baseline characteristics of study participants. Highest numbers of participants had age of > 40 years in all three groups and difference of age in all three groups was not significant (P = 0.70). Postmenopausal women were high in group of both malignant and benign ovarian tumor and there was no significant different in menopausal status in all three groups (P = 0.25). The prevalence of a family history of ovarian cancer was highest in malignant ovarian tumors (54%) followed by benign ovarian tumors (28%) and controls (8%) and the difference of prevalence was significant (P < 0.001). There were no significant differences of parity (P < 0.10) and oral contraceptive (OCP) use (P = 0.48) in study participants. Most of the ovarian malignant cases have mucinous type (44%) histopathology followed by serous (40%), clear cell (10%) and endometroid/cyst type (6%). Highest numbers of cases (64%) were in late FIGO staging (Stage III and IV).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristic of study participants

| Variables | Malignant ovarian tumor n (%) | Benign ovarian tumor n (%) | Controls n (%) | P valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| ≤ 40 years | 17 (34%) | 23 (46%) | 22 (44%) | 0.70 |

| > 40 years | 33 (66%) | 27 (56%) | 28 (56%) | |

| Menopausal status | ||||

| Premenopausal | 17 (34%) | 20 (40%) | 25 (50%) | 0.25 |

| Postmenopausal | 33 (66%) | 30 (60%) | 25 (50%) | |

| Family history | ||||

| Yes | 27 (54%) | 14 (28%) | 4 (8%) | < 0.001 |

| No | 23 (46%) | 36 (72%) | 46 (92%) | |

| Parity | ||||

| 0 | 14 (28%) | 16 (32%) | 10 (20%) | 0.10 |

| 1–2 | 26 (52%) | 25 (50%) | 28 (56%) | |

| > 2 | 10 (20%) | 9 (18%) | 12 (24%) | |

| OCP used | ||||

| Yes | 10 (10%) | 15 (30%) | 14 (28%) | 0.48 |

| No | 40 (80%) | 35 (70%) | 36 (72%) | |

| Histopathology | ||||

| Mucinous | 22 (44%) | 11 (22%) | – | – |

| Serous | 20 (40%) | 26 (52%) | – | |

| Clear cell | 5 (10%) | 13 (26%) | – | |

| Endometroid/cyst | 3 (6%) | – | – | |

| FIGO staging | ||||

| Early stage (I and II) | 18 (36%) | – | – | – |

| Late stage (III and IV) | 32 (64%) | – | – | |

aChi-square test

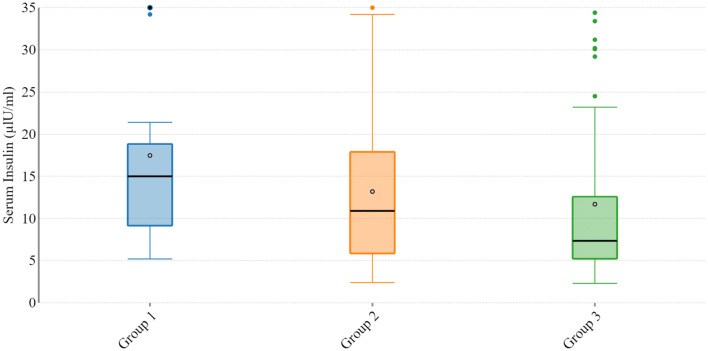

Table 2 depicts baseline features, serum level of insulin (Fig. 1) and adiponectin (Fig. 2) in study participants. There was no significant difference of age (P = 0.76), BMI (P = 0.91) and HbA1C (P = 0.69) in study participants. The median of fasting insulin in healthy controls was 7.3 µlU/ml, in benign ovarian conditions it was 10.9 µlU/ml and in malignant ovarian condition it was 15.0 µlU/ml. The difference of insulin level among three group was significant (P = 0.02). The median of serum adiponectin in healthy controls was 13.6 µg/ml, in benign ovarian conditions it was 8.0 µg/ml and in malignant ovarian conditions the median was 5.1 µg/ml. Data was found to be non parametric by kolmogrov-smirnov analysis and these three groups were compared using Kruskal Wallis test and groups were found to be significantly different (P < 0.001).

Table 2.

Baseline features and serum level of insulin and adiponectin in study participants

| Variable | Malignant ovarian tumor (Group 1) | Benign ovarian tumor (Group 2) | Controls (Group 3) | P valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In Mean ± SD | ||||

| Age (years) | 50.1 ± 10.7 | 48.6 ± 15.9 | 48.5 ± 9.2 | 0.76 |

| BMI (Kg/m2) | 26.0 ± 3.6 | 25.7 ± 3.5 | 25.8 ± 2.5 | 0.91 |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.7 ± 0.7 | 5.6 ± 0.8 | 5.6 ± 0 .5 | 0.69 |

| In median and range | ||||

| Serum insulin (µlU/ml) | 15.0 (5.2–100.2) | 10.9 (2.4–38.4) | 7.3 (2.3–34.4) | 0.02 |

| Serum adiponectin (µg/ml) | 5.1 (1.9–10.4) | 8.0 (2.3–13.0) | 13.6 (10.5–17.8) | < 0.001 |

aP value is calculated by one was ANOVA test and Kruskal–Wallis test

Fig. 1.

Serum insulin level in malignant ovarian tumor (group 1), benign ovarian tumor (group 2) and controls (group 3)

Fig. 2.

Serum adiponectin level in malignant ovarian tumor (group 1), benign ovarian tumor (group 2) and controls (group 3)

Table 3 depicts Odds ratio (OR) and CI of insulin and adiponectin in malignant ovarian tumor cases and controls, calculated by unconditional logistic regression. All study participants were adjusted for age, BMI, menopausal status, OCP use, and parity. Low tertile of insulin and high tertile of adiponectin were taken as reference. A significant increase risk of ovarian cancer was found in high tertile (≥ 18.7 µlU/ml) of serum insulin level (OR = 2.7; 95% CI = 1.00–6.67, P = 0.04). A significantly increased risk of ovarian cancer was found in lower tertile (≤ 5.45 µg/ml) of adiponectin level (OR = 3.2; 95% CI = 1.10–9.71, P = 0.03).

Table 3.

Odds ratio and 95% CI of Insulin and Adiponectin for malignant ovarian tumor cases and controls

| Malignant Cases (n) | Controls (n) | ORa | CI | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insulin (µlU/ml) | |||||

| ≤ 6.27 | 12 (24%) | 16 (32%) | 1 (ref) | – | – |

| 6.27–18.6 | 15 (30%) | 22 (44%) | 0.9 | 0.33–2.46 | 0.85 |

| ≥ 18.7 | 25 (50%) | 12 (24%) | 2.7 | 1.00-.6.67 | 0.04 |

| Adiponectin (µg/ml) | |||||

| ≥ 9.25 | 17 (34%) | 26 (52%) | 1 (ref) | – | – |

| 5.46–9.24 | 18 (36%) | 17 (54%) | 1.6 | 0.65–3.98 | 0.29 |

| ≤ 5.45 | 15 (300%) | 07 (14%) | 3.2 | 1.10–9.71 | 0.03 |

aOR and 95% CI were calculated by unconditional logistic regression

Table 4 depicts serum level of insulin and adiponectin in different staging and histopathological types.

Table 4.

Distribution of serum insulin and adiponectin according to FIGO staging and histopathological types in malignant ovarian tumors

| Early stage (I and II) Median and range |

Advanced stage (III and IV) Median and range |

Pa value | Serous histopathology | Non-serous histopathology | Pa value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insulin (µlU/ml) | 11.3 (5.2–17.3) | 12.2 (6.2–100.2) | 0.16 | 11.9 (5.2–18.5) | 14.0 (6.8–100.0) | 0.10 |

| Adiponectin (µg/ml) | 5.3 (3.1–10.4) | 4.8 (1.8–8.9) | 0.19 | 4.6 (2.9–10.4) | 3.9 (1.9–7.8) | 0.20 |

ap value calculated by Mann–Whitney test

Median value of serum insulin was high in advanced stage of malignant ovarian tumor (12.2 (6.2–100.2), P = 0.16) and non-serous histopathological types (14.0 (6.8–100.0), P = 0.10), but there was no statistical difference. Median value of serum adiponectin was low in advanced stage of malignant ovarian tumor (4.8 (1.8–8.9), P = 0.16) and non-serous histopathological types (3.9 (1.9–7.8), P = 0.20), but there was no statistical difference.

Discussion

More than 75% cases of ovarian cancer are diagnosed at late stage due to non specific symptoms, absence of effective screening tests or standard therapy for ovarian cancer [15, 16]. We investigate the association of serum insulin and adiponectin with the risk for development of epithelial ovarian cancer in non-diabetics individuals. We found significantly high level of serum insulin in malignant ovarian tumors and hyperinsulinemia is associated with increased risk for development of ovarian cancer. We found significantly low level of serum adiponectin in malignant ovarian tumors and low level of adiponectin is associated with increased risk of development of ovarian cancer. There were no significant associations of insulin and adiponectin with stating and histopathological types of ovarian cancers.

Very limited studies and information are available on association of insulin and adiponectin with ovarian cancer. Insulin receptors are localized in the ovarian stroma, granulose cells and theca cells of the ovary. Insulin signaling pathways like insulin receptor substrates (IRS), mitogen- activated protein kinase (MAPK), and phosphoinositide kinase (PI3K) interact with luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) signaling pathways and further modulate the development, growth and maturation of oocyte [17–19]. Insulin stimulates ovarian steroidogenesis through insulin receptors and interaction on insulin with FSH further produce additional estrogens and regulates ovarian cell differentiation [20]. Insulin resistance produces chronic low grade inflammation by generating inflammatory molecules like TNF-α, IL-6, leptin and MCP-1 which further stimulates caner progression [21]. Insulin stimulates hepatic synthesis of insulin growth factor-1 which further induces tumor growth by its anti-apoptotic and mitogenic properties [22]. Thus our results are biologically acceptable based on above facts. Similar results had been reported by Otokozawa Seiko, et al. in which high tertile of serum insulin level was associated with increased risk of ovarian cancer compared to low tertile of serum insulin level [23] But Serin IS, et al. reported that that insulin resistance index by homeostasis model assessment was not a valid indicator for ovarian malignancy [24].

Adiponectin is also known as ‘guardian angel cytokine’, as it play crucial role in pathogenesis of obesity related cancers like ovarian cancer. Adiponectin has been associated with anti-neoplastic effects by increasing receptor mediated signaling pathway directly on tumor cells and indirectly by regulating inflammatory response, insulin sensitivity in target tissues and tumor angiogenesis [25]. Hypoadiponectinemia may cause aberrant ovarian cancer development via abnormal and persistent activation of PIK3 pathway [26]. Adiponectin antagonizes the consequences of TNF-α as its structure belongs to TNF-α and produce anti-inflammatory environment. Thus hypoadiponectinemia can cause chronic inflammation by generating chronic inflammatory mediators and chronic inflammation play crucial role in development and progression of ovarian cancer [27]. Adiponectin also interacts with hormonal signals like leptin and sex steroid, which further regulates in vivo oncogenesis process [28]. Adiponectin also acts as a insulin sensitizer by directly acting on pancreatic beta cells via mediator of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPAR-γ) action. Thus it enhances the survival of pancreatic beta cells and surpasses the action of insulin [29]. So our findings of hyperinsulinemia and hypoadiponectinemia in ovarian cancer are biologically acceptable. Similar results had been reported by Otokozawa et al. [23] in which low tertile of serum adiponectin level was associated with increased risk of ovarian cancer compared to high tertile of serum adiponectin level. Jin et al. [30] also reported low adiponectin level in patients of ovarian cancer and there was no significant association of adiponectin with staging of ovarian cancer.

In summary, hyperinsulinemia (OR = 2.7, 95% CI = 1.00–6.67) and hypoadiponectinemia (OR = 3.2, 95% CI = 1.10–9.71) were significantly associated with the increased risk for development of ovarian cancer. We had strictly excluded patients of diabetes and chronic inflammatory disorders to prevent false positive low level of adiponectin and false positive high level of insulin. All study participants were adjusted for age, BMI, menopausal status, OCP use, and parity. Hospital based study and small sample size are limitations of study. Multicentric study and population based study should be done along with sex hormone profile, leptin and other inflammatory markers to validate our findings.

Conclusion

Serum insulin was significantly high and adiponectin was significantly low in ovarian cancer patients compared to benign ovarian tumors and healthy controls. High serum insulin level and low adiponectin levels were significantly associated with increased risk for development of ovarian cancer. Serum adiponectin can be included in blood markers panel of screening and diagnosis of ovarian cancer.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to members of ethical committee, Maulana Azad Medical College, New Delhi for giving opportunity to conduct study.

Author’s Contribution

RKG designed research, collection and analysis of data, clinical monitoring and laboratory detection and reviewed the manuscript; SJD performed collection and analysis of data and helped in manuscript preparation. SK, SKG, RT and SLJ helped in discussion, designing research strategies and crafting the manuscript. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research and/or publication of this article.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethics Approval

Study has been approved by ethical committee of Maulana Azad Medical College, New Delhi and hospital based case–control study has been performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was taken from all participants.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.NCRP Report. Three year report of population based cancer registries 2012–14. National cancer registry program, Indian Council of Medical Research 2016

- 2.Marth C, Reimer D, Zeimet AG. Front-line therapy of advanced epithelial ovarian cancer: standard treatment. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:viii36–viii39. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peres LC, Cushing-Haugen KL, Kobel M, Harris HR, Berchuck A, Rossing MA, et al. Invasive epithelial ovarian cancer survival by histotype and disease stage. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;111:60–68. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djy071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matulonis UA, Sood AK, Fallowfield L, Howitt BE, Sehouli J, Karlan BY. Ovarian cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16061. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhan Q, Wang C, Ngai S. Ovarian cancer stem cells: a new target for cancer therapy. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:916819. doi: 10.1155/2013/916819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:7–34. doi: 10.3322/caac.21551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Momenimovahed Z, Tiznobaik A, Taheri S, Salehiniya H. Ovarian cancer in the world: epidemiology and risk factors. Int J Womens Health. 2019;11:287–299. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S197604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Booth A, Magnuson A, Fouts J, Foster M. Adipose tissue, obesity and adipokines: role in cancer promotion. Horm Mol Biol Clin Investig. 2015;21:57–74. doi: 10.1515/hmbci-2014-0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tworoger SS, Huang T. Obesity and ovarian cancer. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2016;208:155–176. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-42542-9_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katira A, Tan PH. Evolving role of adiponectin in cancer-controversies and update. Cancer Biol Med. 2016;13:101–119. doi: 10.20892/j.issn.2095-3941.2015.0092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Di Zazzo E, Polito R, Bartollino S, Nigro E, Porcile C, Bianco A, et al. Adiponectin as link factor between adipose tissue and cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:E839. doi: 10.3390/ijms20040839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu HL, Fang H, Xu WH, Qin GY, Yan YJ, Yao BD, et al. Cancer incidence in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a population-based cohort study in Shanghai. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:852. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1887-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gallagher EJ, LeRoith D. Obesity and diabetes: the increased risk of cancer and cancer-related mortality. Physiol Rev. 2015;95:727–748. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00030.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joung KH, Jeong JW, Ku BJ. The association between type 2 diabetes mellitus and women cancer: the epidemiological evidences and putative mechanisms. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:920618. doi: 10.1155/2015/920618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grayson K, Gregory E, Khan G, Guinn BA. Urine biomarkers for the early detection of ovarian cancer—are we there yet? Biomark Cancer. 2019;11:1179299X19830977. doi: 10.1177/1179299X19830977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chandra A, Pius C, Nabeel M, Nair M, Vishwanatha JK, Ahmad S, et al. Ovarian cancer: current status and strategies for improving therapeutic outcomes. Cancer Med. 2019;8:7018–7031. doi: 10.1002/cam4.2560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dupont J, Scaramuzzi RJ. Insulin signalling and glucose transport in the ovary and ovarian function during the ovarian cycle. Biochem J. 2016;473:1483–1501. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20160124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kong L, Wang Q, Jin J, Xiang Z, Chen T, Shen S, et al. Insulin resistance enhances the mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway in ovarian granulosa cells. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0188029. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0188029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Das D, Arur S. Conserved insulin signaling in the regulation of oocyte growth, development, and maturation. Mol Reprod Dev. 2017;84:444–459. doi: 10.1002/mrd.22806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stocco C, Baumgarten SC, Armouti M, Fierro MA, Winston NJ, Scoccia B, et al. Genome-wide interactions between FSH and insulin-like growth factors in the regulation of human granulosa cell differentiation. Hum Reprod. 2017;32:905–914. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dex002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Giovannucci E, Harlan DM, Archer MC, Bergenstal RM, Gapstur SM, Habel LA, et al. Diabetes and cancer: a consensus report. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:1674–1685. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Orgel E, Mittelman SD. The links between insulin resistance, diabetes, and cancer. Curr Diabetes Rep. 2013;13:213–222. doi: 10.1007/s11892-012-0356-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Otokozawa S, Tanaka R, Akasaka H, Ito E, Asakura S, Ohnishi H, Saito S, et al. Associations of serum isoflavone, adiponectin and insulin levels with risk for epithelial ovarian cancer: results of a case-control study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16:4987–4991. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2015.16.12.4987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Serin IS, Tanriverdi F, Yilmaz MO, Ozcelik B, Unluhizarci K. Serum insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I, IGF binding protein (IGFBP)-3, leptin concentrations and insulin resistance in benign and malignant epithelial ovarian tumors in postmenopausal women. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2008;24:117–121. doi: 10.1080/09513590801895559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gelsomino L, Naimo GD, Catalano S, Mauro L, Ando S. The emerging role of adiponectin in female malignancies. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:E2127. doi: 10.3390/ijms20092127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheaib B, Auguste A, Leary A. The PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway in ovarian cancer: therapeutic opportunities and challenges. Chin J Cancer. 2015;34:4–16. doi: 10.5732/cjc.014.10289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Savant SS, Sriramkumar S, O'Hagan HM. The role of inflammation and inflammatory mediators in the development, progression, metastasis, and chemoresistance of epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2018;10:E251. doi: 10.3390/cancers10080251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grossmann ME, Cleary MP. The balance between leptin and adiponectin in the control of carcinogenesis-focus on mammary tumorigenesis. Biochimie. 2012;94:2164–2171. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2012.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ruan H, Dong LQ. Adiponectin signaling and function in insulin target tissues. J Mol Cell Biol. 2016;8:101–109. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjw014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jin JH, Kim HJ, Kim CY, Kim YH, Ju W, Kim SC. Association of plasma adiponectin and leptin levels with the development and progression of ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2016;59:279–285. doi: 10.5468/ogs.2016.59.4.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]