Abstract

This study aimed to identify a symbiotic fungus strain HX-1 with anti-Vibrio harveyi activity and isolate and identify the active compound. The HX-1 strain was identified as Aspergillus fumigatus according to the morphological characteristics and internal transcribed spacer (ITS) sequence analysis. The compound was isolated from the fermentation product of HX-1 strain through ethyl acetate extraction, silica gel and Sephadex LH-20 column chromatography, and semi-preparative HPLC techniques using an antibacterial-guided fractionation method. According to its physicochemical properties and spectral characteristics, the compound was identified as trypacidin having the same anti-V. harveyi activity as streptomycin sulfate, with the minimum inhibitory concentration of 31.25 µg/mL.

Keywords: Aspergillus fumigatus, Antibacterial activity, Bioassay-guided isolation, Trypacidin

Introduction

The term symbiosis was first proposed in the nineteenth century by a German surgeon, Anton de Bary, to indicate the close interrelationship that occurs between two different organisms, and plays an important role in the generation and maintenance of biodiversity (Lu et al. 2000). Symbiotic microorganisms establish a stable reciprocal symbiotic relationship with the host due to their long-term co-evolution and are often associated with special metabolic pathways, which may produce secondary metabolites that have important effects on themselves and their hosts (Li et al. 2016; Sánchez-Cruz et al. 2019).

Vibrio harveyi is a halophilic Gram-negative bacterium widely found in marine habitats and is one of the most frequently detected pathogenic bacteria that cause vibriosis outbreaks particularly in marine aquaculture, thus leading to the high mortality of aquatic animals (Guo et al. 2019a; Morya et al. 2014; Guo et al. 2020a). At present, antibiotics are mainly used in marine aquaculture to control pathogenic bacteria, such as V. harveyi (Yang et al. 2019). However, the long-term application or abuse of these drugs has led to the emergence of drug-resistant strains, making antibiotics less effective and various pathogens causing serious diseases. Antibiotics residues in aquatic products also directly threaten human health and safety (Elmahdi et al. 2016; Tomova et al. 2015). In addition to comprehensive preventive and control measures, such as adjusting aquaculture structure and culture mode, selecting excellent aquatic animal seedlings and attaching importance to disease prevention mode, new substitutes of antibiotics for aquaculture industry, must be urgently to developed (Guo and Wang 2017).

At present, the development of antibiotic substitutes mainly includes the following aspects: essential oils (Manju et al. 2016), plant extracts (Rosa et al. 2019), phage (Doss et al. 2017), probiotics (Hai 2015) and secondary metabolites of microorganisms (Xu et al. 2014; Durairaj 2018). The Clam-symbiotic fungus HX-1 is a strain with remarkable antagonistic activity toward aquatic pathogen V. harveyi. This study identified the species of strain HX-1, isolated the active compound through antibacterial-guided fractionation method, and identified its structure.

Materials and methods

Materials and medium

Fungus HX-1 strain (CCTCC NO: M 2,018,377) was maintained on Sabour’s dextrose agar (SDA) plate and kept at the Laboratory of Marine Natural Products Chemistry in Jiangsu Ocean University, China. V. harveyi 1.8690 was stored in our laboratory.

Sabour’s dextrose (SD) medium was composed of glucose 4% and peptone 1%, and SDA medium was prepared by adding agar 2% into SD. The modified SD (MSD) medium was composed of glucose 3%, peptone 1%, CaCl2 0.05%, and MgSO4·7H2O 0.05%. Oligotrophic medium was composed of soluble starch 1% and peptone 0.1%. Czapek yeast extract (CY) medium was composed of glucose 3%, yeast extract 1%, NaNO3 0.3%, KCl 0.05%, MgSO4·7H2O 0.05%, FeSO4 0.001%, and K2HPO4 0.1%. Fungal No. 5 medium was composed of glucose 1%, maltose 2%, sodium glutamate 1%, yeast extract 0.3%, KH2PO4 0.05%, and MgSO4·7H2O 0.03%. Beef extract peptone (BP) medium was composed of beef extract 0.3%, peptone 1%, and agar 2%. All the above media were dissolved in natural aged seawater. Other reagents were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

Morphological features

The purified strain HX-1 was inoculated on SDA plate and cultured at 28 °C for 5–7 days, and the cultural characteristics of the colonies were observed and described. A small amount of strong charcoal was placed on a clean glass slide and stained by the blue droplets, and the conidiosporangium was observed under a microscope. The strains were streaked on the SDA medium and the coverslips were placed at an angle of 45°. The cells were cultured at 28 °C for 7 days. A glass coverslip with mycelium was finally obtained, and the conidiospores were observed under a Hitachi H-7650 scanning electron microscope.

Internal transcribed spacer (ITS) sequence analysis

The HX-1 strain was inoculated on SDA plate and cultured at 28 °C for 7 days and then sent for ITS sequence analysis (Beijing Sanbo Yuanzhi Biotechnology Co., Ltd). The ITS sequence of strain HX-1 was aligned manually with available nucleotide sequences retrieved from the GenBank and the multiple sequence alignment using CLUSTAL X (Ver.1.83). Phylogenetic tree was constructed using the Neighbor-joining method from MEGA (Ver.4.0). The resultant tree topologies were evaluated by bootstrap analysis based on 1000 replications (Song et al. 2014).

Fermentation medium screening

The spores of the activated HX-1 strain were inoculated into a 500 mL flask containing 200 mL of SD medium and cultured at 28 °C with 160 r/min for 24 h as the seed culture. The prepared seed culture was separately added into another 500 mL flask containing 200 mL of oligotrophic, SD, MSD, CY, and Fungal No. 5 medium in a ratio of 2% (v/v). The flasks were incubated at 28 °C with 160 r/min for 7 days. The fermentation products were extracted three times using 200 mL of ethyl acetate and ultrasonication for 1 h. The extracts were obtained and concentrated under reduced pressure to dryness. Each sample was mixed with methanol to produce a solution of 10 mg/mL, and the antibacterial activity against V. harveyi was tested. The type of fermentation medium was determined by the antibacterial activity.

Fermentation and preparation of active extracts

The prepared seed culture was separately added into a 500 mL flask containing 200 mL of fungal No. 5 medium in a ratio of 2% (v/v). Ninety-six bottles were incubated at 28 °C with 160 r/min for 7 days, separately added with 200 mL of ethyl acetate, and ultrasonicated for 1 h. The extraction steps were conducted three times. The extracts were combined and concentrated under reduced pressure to produce the active extract (35.2 g).

Bioactivity-guided fractionation of active compound

The active extract mixed with the appropriate amount of silica gel powder was added to a decompressed silica gel column (6 × 60 cm) pre-loaded with 10 times the amount of silica gel powder (200–300 mesh) for vacuum separation. The 500 mL of eluent consisting of petroleum ether: dichloromethane (100:0, 50:50, 0:100, v/v), dichloromethane: methanol (100:1, 75:1, 50:1, 25:1, 10:1, 5:1, 1:1, v/v) gradient elution was concentrated with a rotary evaporator under reduced pressure to obtain 10 fractions. The antibacterial activity of each fraction was determined, and fraction 6 (50:1) had substantial antibacterial activity (16.73 mm).

Fraction 6 were individually separated with Sephadex LH-20 column chromatography using 1:1 (v/v) of dichloromethane: methanol as the eluent under a flow rate of 10 mL/h. The eluents were analyzed by silica gel thin layer chromatography, and the same eluents were combined to obtain sub-fractions. Sub-fraction 6.2 with antibacterial activity was analyzed by HPLC. Compound 1 was prepared from sub-fraction 6.2 (MeOH: H2O = 7:3, 1.5 mL/min, tR = 16.6 min, 18.4 mg).

Antibacterial assay

The antibacterial activity of the sample against V. harveyi was determined by Oxford cup method (Guo et al. 2019b). In brief, 20 mL of BP medium was poured into 90 mm diameter Petri dish and allowed to settle at room temperature for 30 min. The medium was then added with 100 μL of V. harveyi suspensions (1 × 106 cells/mL) and smeared evenly. Oxford cups (outer diameter of approximately 8.0 mm) were placed on the medium, and 200 μL of the sample (10 mg/mL) was added in the cups with a pipette, and cultured triplicate at 37 °C for 24 h. The average value of the inhibition zone diameters was taken as the antibacterial activity (mm) of the tested sample.

Minimal inhibitory concentration assay

The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of the active compound against V. harveyi was determined by two-fold dilution method (Guo et al. 2019a). The compound and streptomycin sulfate were dissolved in methanol or distilled water and diluted to a serial concentration by two-fold dilution method. Antibacterial activities were measured by the above antibacterial assay. Each sample was prepared in two parallels and the MIC was defined as the amount of compound that produce the inhibition zone with complete consistency between results.

Results

Identification of strain HX-1

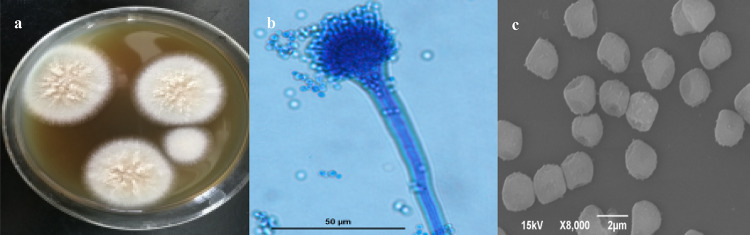

The colony diameter could reach 50–65 mm after the purified strain HX-1 was cultured on SDA plate at 28 °C for 7 days. The center is slightly convex, with irregular stripes and thin edges, and the center surface is fluffy. The hyphae are grayish white or milky white and light cyan on the back (Fig. 1a). The conidiophore is smooth and not branched, the top capsule is hemispherical under the microscope (Fig. 1b). Electron microscope scanning image showed that the sporangia of HX-1 consisted of many spores with conidial diameter of approximately 2 μm. The conidia are nearly spherical and rough (Fig. 1c).

Fig. 1.

a Colony morphology of strain HX-1; (b) Micrograph of conidiosporangium; (c) Scanning electron micrograph of conidiospore

The ITS sequence of strain HX-1 was generated and the size of amplified fragment was 593 bp. The results of the ITS gene sequence analysis were submitted to GenBank (access no. MH824433). Phylogenetic analysis of ITS gene sequence of the strain and related taxa revealed its 99% similarity to the Aspergillus fumigatus F35-02 and A. fumigatus RES1 (Genbank accession no. KX664380.1 and KY026061.1, respectively) (Fig. 2). On the basis of this result and the morphological features, the HX-1 strain was identified as A. fumigatus (Qi 1997).

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of strain HX-1. The sequence number in the bracket means the GenBank accession number of the strain. The number at the node means the percentage of occurrence in 1000 bootstrap trees. The scale bar represents 2 substitutions per nucleotide position

Determination of fermentation medium of strain HX-1

The antibacterial activities of the ethyl acetate extracts of the fermentation products under the five types of culture medium against V. harveyi are shown in Table 1. The culture effect of fungus No. 5 medium is the best, and the average inhibition zone diameter is 25.16 ± 0.02 mm. Thus, Fungus No. 5 medium was adopted as the most suitable medium for strain HX-1 to produce antibacterial active substances.

Table 1.

The antibacterial activity of the fermentation products under different fermentation medium

| Type of medium | Inhibition zone diameters (X ± SD, n = 3, mm) |

|---|---|

| Oligotrophic | 13.73 ± 0.90 |

| Sabour’s dextrose (SD) | 22.95 ± 0.68 |

| Modified Sabour's dextrose (MSD) | 23.20 ± 0.44 |

| Czapek yeast extract (CY) | 17.06 ± 0.68 |

| Fungal No. 5 | 25.16 ± 0.02 |

Structure identification of antibacterial compound

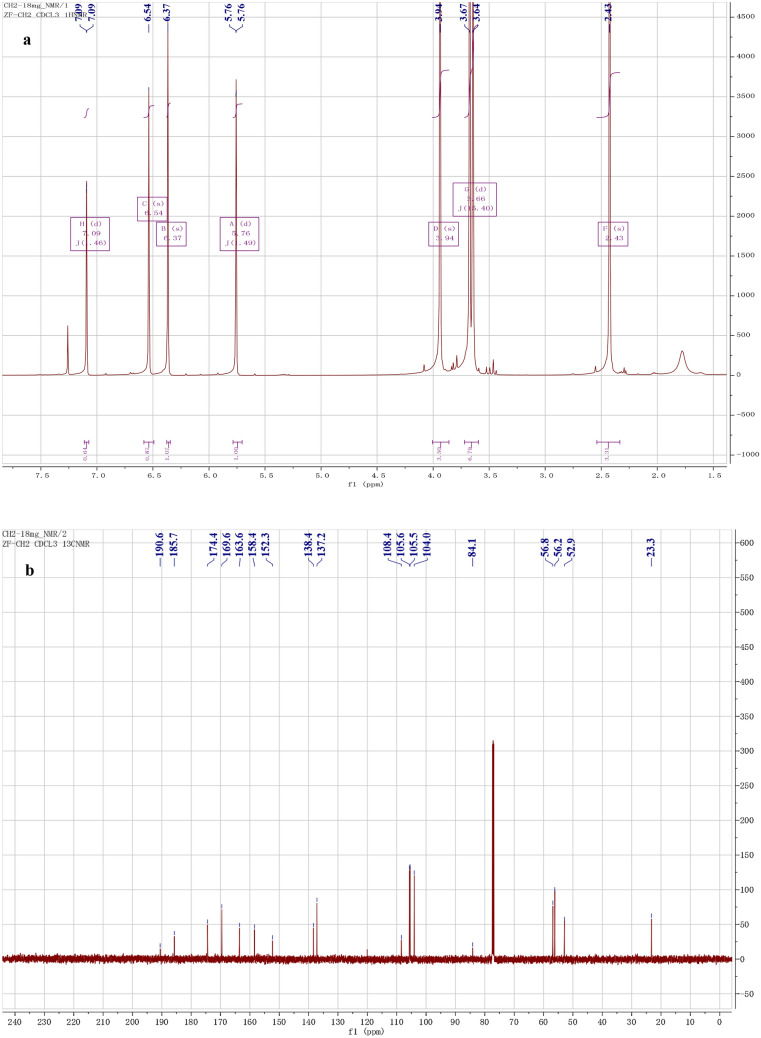

The active extract was successively subjected to silica gel vacuum column chromatography, Sephadex LH-20 column chromatography, and semi-preparative high-performance liquid chromatography technology with anti-V. harveyi activity as the guided method. Finally, a pure compound was isolated. On the basis of the spectral characteristics (1H- and 13C-NMR), the active compound was identified as trypacidin.

Trypacidin: white powder. 1H-NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): 6.37 (1H, s, H-5), 2.43 (3H, s, H-6a), 6.54 (1H, s, H-7), 7.09 (1H, d, J = 2.2, H-2′), 5.76 (1H, s, H-4′), 3.94 (3H, s, 4-OCH3), 3.67 (3H, s, 6′-OCH3), 3.64 (3H, s, 5′-OCH3) (Fig. 3a). 13C-NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): 84.1(C-2), 190.6 (C-3), 108.4 (C-3a), 158.4 (C-4), 105.5 (C-5), 152.3 (C-6), 23.3 (C-6a), 105.6 (C-7), 174.4 (C-7a), 138.4 (C-1′), 137.2 (C-2′), 185.7 (C-3′), 104.0 (C-4′), 169.6 (C-5′), 163.6 (C-6′), 56.2 (4-OCH3), 52.9 (6′-OCH3), 56.8 (5′-OCH3) (Fig. 3b). The above data are consistent with the literature report, so the compound was identified as trypacidin (Fig. 4) (Pinheiro et al. 2013).

Fig. 3.

1H-NMR spectrum (a) and 13C-NMR spectrum (b) of trypacidin

Fig. 4.

Chemical structure of trypacidin

Anti-V. harveyi activity of trypacidin

The in vitro bacteriostatic activity of trypacidin against V. harveyi was determined by two-fold dilution method. The MIC value of trypacidin against V. harveyi was 31.25 μg/mL, which was equivalent to that of streptomycin sulfate against V. harveyi.

Discussion

With the increasing resistance of pathogenic bacteria in the aquatic industry, the development of novel antibacterial agents is imminent. Owing to their unique living environment, marine microorganisms provide the possibility of producing new types of active metabolites. Among them, marine-derived fungi can produce promising metabolites with various pharmacological activities (Wang et al. 2020). Therefore, the discovery of antibacterial metabolites from marine-derived fungi to combat pathogenic bacteria has become crucial (Guo and Wang 2017). In this study, the fungus HX-1 strain was isolated and screened from the symbiotic microorganisms of marine cultured clams. This strain exhibits favorable antagonistic activity toward aquatic pathogenic V. harveyi. On the basis of its morphological characteristics and ITS analysis, strain HX-1 was identified as A. fumigatus.

The production of biologically active compounds in microorganisms may be strongly affected by many different factors, such as genetic or ecology potential and culture medium composition (Guo et al. 2020b). In this study, the fermentation medium of A. fumigatus HX-1 producing anti-V. harveyi active secondary metabolites was screened, and fungus No. 5 medium was selected as the optimal medium for the synthesis of antibacterial active secondary metabolites. With the use of the antibacterial-guided separation method, a compound was purified from the fermentation products of A. fumigatus HX-1 through solvent extraction, silica gel and Sephadex LH-20 column chromatography, and HPLC techniques. The compound was identified as trypacidin according to its spectral data.

Balan et al. first reported trypacidin, a polyketide that was isolated from A. fumigatus spores and is active against some protozoa and bacteria, including Trypanosoma cruzi, Toxoplasma gondii, Escherichia coli, Bacillus subtilis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus (Pinheiro et al. 2013; Parker and Jenner 1968; Mattern et al. 2015). In this study, trypacidin was found to exhibit the favorable bacteriostatic effect against aquatic pathogenic V. harveyi. Further research on its in vivo effects and mechanism against aquatic pathogens will help expand its usage in the prevention and control potential of bacterial diseases in aquaculture.

Conclusion

In summary, a symbiotic fungus strain HX-1 with anti-V. harveyi activity was identified as A. fumigatus according to the morphological and molecular properties. With the use of an antibacterial-guided fractionation method, an active compound was isolated from the fermentation product of HX-1 strain through ethyl acetate extraction, silica gel and Sephadex LH-20 column chromatography, and HPLC techniques. According to its spectral characteristics, the compound was identified as trypacidin having the same anti-V. harveyi activity as streptomycin sulfate with a MIC value of 31.25 µg/mL. The results suggested that trypacidin could be developed as potential therapeutic candidate for the treatment of vibriosis.

Acknowledgments

This work financially supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Provincial Department of Education (19KJB350007), Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD), Open-end Funds of Jiangsu Key Laboratory of Marine Bioresources and Environment (SH20201207) and Postgraduate Research & Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province (KYCX20_2896).

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that no conflict of interest.

References

- Doss J, Culbertson K, Hahn D, Camacho J, Barekzi N. A review of phage therapy against bacterial pathogens of aquatic and terrestrial organisms. Viruses. 2017;9:50. doi: 10.3390/v9030050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durairaj T, Ramasamy V, Chithravel V, Pushparaj K, Khurshid AKM. Isolation, structure elucidation and antibacterial activity of methyl-4,8-dimethylundecanate from the marine actinobacterium Streptomyces albogriseolus ecr64. Microb Pathog. 2018;121:166–172. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2018.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmahdi S, DaSilva LV, Parveen S. Antibiotic resistance of Vibrio parahaemolyticus and Vibrio vulnificus in various countries: a review. Food Microbiol. 2016;57:128–134. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2016.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo L, Wang C. Optimized production and isolation of antibacterial agent from marine Aspergillus flavipes against Vibrio harveyi. Biotech. 2017;7:383. doi: 10.1007/s13205-017-1015-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo L, Cao X, Yang S, Wang X, Wen Y, Zhang F, Chen H, Wang L. Characterization, solubility and antibacterial activity of inclusion complex of questin with hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin. Biotech. 2019;9:123. doi: 10.1007/s13205-019-1663-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo L, Zhang F, Wang X, Chen H, Wang Q, Guo J, Cao X, Wang L. Antibacterial activity and action mechanism of questin from marine Aspergillus flavipes HN4–13 against aquatic pathogen Vibrio harveyi. Biotech. 2019;9:14. doi: 10.1007/s13205-018-1535-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo L, Wang L, Li X, Xu X, Guo J, Wang X, Yang W, Xu F, Li F. Enhanced production of questin by marine-derived Aspergillus flavipes HN4–13. Biotech. 2020;10:54. doi: 10.1007/s13205-020-2067-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo L, Wang X, Feng J, Xu X, Li X, Wang W, Sun Y, Xu F. Extraction, identification and mechanism of action of antibacterial substances from Galla chinensis against Vibrio harveyi. Biotechnol Biotec Eq. 2020;34:1215–1223. doi: 10.1080/13102818.2020.1827980. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hai NV. The use of probiotics in aquaculture. J Appl Microbiol. 2015;119:917–935. doi: 10.1111/jam.12886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Song X, Yin Z, Jia R, Li Z, Zhou X, Zou Y, Li L, Yin L, Yue G, Ye G, Lv C, Shi W, Fu Y. The antibacterial activity and action mechanism of emodin from polygonum cuspidatum against haemophilus parasuis in vitro. Microbiol Res. 2016;186–187:139–145. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2016.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lira-Ruan V, Hernández G, Wong-Villarreal A, Folch-Mallol JL. Isolation and characterization of endophytes from nodules of Mimosa pudica with biotechnological potential. Microbiol Res. 2018;217:51–59. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2018.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H, Zou WX, Meng JC, Hu J, Tan RX. New bioactive metabolites produced by Colletotrichum sp., an endophytic fungus in Artemisia annua. Plant Sci. 2000;151:67–73. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9452(99)00199-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manju S, Malaikozhundan B, Withyachumnarnkul B, Vaseeharan B. Essential oils of Nigella sativa protects Artemia from the pathogenic effect of Vibrio parahaemolyticus Dahv2. J Invertebr Pathol. 2016;136:43–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2016.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattern DJ, Schoeler H, Weber J, Novohradská S, Kraibooj K, Dahse HM, Hillmann F, Valiante V, Figge MT, Brakhage AA. Identification of the antiphagocytic trypacidin gene cluster in the human-pathogenic fungus Aspergillus fumigatus. Appl Microbiol Biot. 2015;99:10151–10161. doi: 10.1007/s00253-015-6898-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morya VK, Choi W, Kim EK. Isolation and characterization of Pseudoalteromonas sp. from fermented Korean food, as an antagonist to Vibrio harveyi. Appl Microbiol Biot. 2014;98:1389–1395. doi: 10.1007/s00253-013-4937-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker GF, Jenner PC. Distribution of trypacidin in cultures of Aspergillus fumigatus. Appl Microbiol. 1968;16:1251–1252. doi: 10.1128/AM.16.8.1251-1252.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro EA, Carvalho JM, Santos DC, Feitosa AO, Marinho PS, Guilhon GM, Santos LS, Souza AL, Marinho AM. Chemical constituents of Aspergillus sp EJC08 isolated as endophyte from Bauhinia guianensis and their antimicrobial activity. An Acad Bras Cienc. 2013;85:1247–1253. doi: 10.1590/0001-3765201395512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi ZT. Flora Fungorum Sinicorum: Aspergillus and Related Sexual Types. Science Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Rosa IA, Rodrigues P, Bianchini AE, Silveira BP, Ferrari FT, Bandeira Junior G, Vargas APC, Baldisserotto B, Heinzmann BM. Extracts of Hesperozygis ringens (Benth.) Epling: in vitro and in vivo antibacterial activity against fish pathogenic bacteria. J Appl Microbiol. 2019;126:1353–1361. doi: 10.1111/jam.14219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Cruz R, Tpia Vázquez I, Batista-García RA, Méndez-Santiago EW, Sánchez-Carbente MDR, Leija A, Yang M, Zhang J, Liang Q, Pan G, Zhao J, Cui M, Zhao X, Zhang Q, Xu D. Antagonistic activity of marine streptomyces sp. s073 on pathogenic Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Fish Sci. 2019;85:533–543. doi: 10.1007/s12562-019-01309-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Song F, Ren B, Chen C, Yu K, Liu X, Zhang Y, Yang N, He H, Liu X, Dai H, Zhang L. Three new sterigmatocystin analogues from marine-derived fungus Aspergillus versicolor MF359. Appl Microbiol Biot. 2014;98:3753–3758. doi: 10.1007/s00253-013-5409-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomova A, Ivanova L, Buschmann AH. Antimicrobial resistance genes in marine bacteria and human uropathogenic Escherichia coli from a region of intensive aquaculture. Environ Microbiol Rep. 2015;4:7803–7809. doi: 10.1111/1758-2229.12327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Tang S, Cao S. Antimicrobial compounds from marine fungi. Phytochem Rev. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s11101-020-09705-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu HM, Rong YJ, Zhao MX, Song B, Chi ZM. Antibacterial activity of the lipopetides produced by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens M1 against multidrug-resistant Vibrio spp. isolated from diseased marine animals. Appl Microbiol Biot. 2014;98:127–136. doi: 10.1007/s00253-013-5291-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]