Abstract

This research aimed to examine the efficacy of the early initiation of breastfeeding within 1 h of birth, early skin-to-skin contact, and rooming-in for the continuation of exclusive breastfeeding until 6 months postpartum. The research used data from the Japan Environment and Children’s Study (JECS), a nationwide government-funded birth cohort study. A total of 80,491 mothers in Japan between January 2011 and March 2014 who succeeded or failed to exclusively breastfeed to 6 months were surveyed in JECS. Multiple logistic regression model was used to analyse the data. The percentage of mothers who succeeded in exclusively breastfeeding to 6 months is 37.4%. Adjusted odds ratios were analysed for all 35 variables. Early initiation of breastfeeding (adjusted odds ratio [AOR]: 1.455 [1.401–1.512]), early skin-to-skin contact (AOR: 1.233 [1.165–1.304]), and rooming-in (AOR: 1.567 [1.454–1.690]) affected continuation of exclusive breastfeeding. Regional social capital (AOR: 1.133 [1.061–1.210]) was also discovered to support the continuation of breastfeeding. In contrast, the most influential inhibiting factors were starting childcare (AOR: 0.126 [0.113–0.141]), smoking during pregnancy (AOR: 0.557 [0.496–0.627]), and obese body type during early pregnancy (AOR: 0.667 [0.627–0.710]).

Subject terms: Nutrition, Public health, Health care, Health policy

Introduction

Breastfeeding has been reported to lower a child’s risk of infectious disease and allergic illness while also being beneficial to the health of the mother1. Given that it contributes to the lifelong health of both mother and child, breastfeeding is widely encouraged throughout the world. The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the World Health Organization (WHO), and the American Academy of Pediatrics all recommend exclusive breastfeeding (EBF)2,3 for the first 6 months postpartum. During EBF, breast milk must be the infant’s only intake, without additional food or drink, including water.

According to surveys conducted by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare in Japan, more than 90% of pregnant women hope to breastfeed their children. Nevertheless, only 50% of mothers are able to continue EBF with their children up to even 3 months postpartum4.

Factors influencing breastfeeding rates include social demographic factors such as the mother’s age5, race6, level of education7, smoking habits8 and presence or absence of obesity9. The list of “Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding” proposed by the WHO and UNICEF contains additional items such as early initiation of breastfeeding (within 30 min of birth), early skin-to-skin contact (Step 4) and 24-h rooming-in (Step 7). Rooming-in entails placing the infant in a stand-alone cot by the bedside of the mother or bed-sharing by attached side-car crib as opposed to keeping the infant in a hospital nursery or separate room (in case of home-deliveries). Large-scale surveys investigating whether these kinds of early postpartum mother–child care practices affect EBF up to 6 months postpartum are rare worldwide and do not exist within Japan.

Using data from the Japan Environment and Children’s Study (JECS), the present study aims to examine the efficacy of early initiation of breastfeeding, early skin-to-skin contact, and rooming-in for the continuation of EBF through to 6 months postpartum, and moreover this study aims to contribute to increasing the rate of EBF up to 6 months postpartum by identifying factors that sustain and inhibit EBF.

Materials and methods

Study population

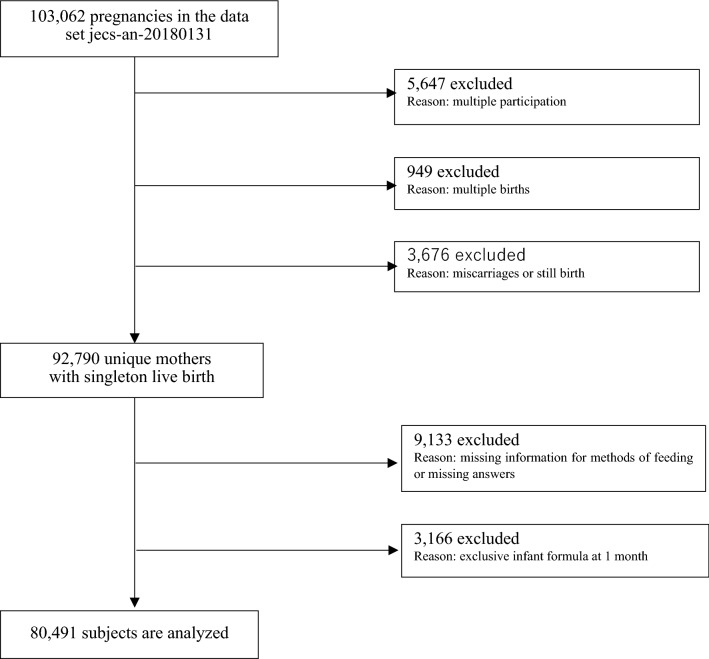

JECS is a nationwide government-funded birth cohort study that evaluates the impact of various environmental factors on children’s health and development. The pregnant women participating in JECS were recruited from 15 areas in Japan between January 2011 and March 201410,11. Further information on the methods utilised within JECS have been previously published10,11. The present study is based on a dataset (jecs-an-20180131) that was released in March 2018. The full dataset contained 103,062 pregnancies. Of these, 5,647 data points were excluded because of multiple registrations, 949 were excluded because of multiple births, and 3676 were excluded because of miscarriages or stillbirths. Among the remaining 92,790 unique mothers with singleton live births, 9133 were excluded because of missing information for methods of feeding or missing answers and 3166 were excluded because of the exclusive use of infant formula at one month. As a result, data from 80,491 mothers were analysed in this study (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Participants flow diagram. See text for details.

Materials

The JECS self-administered questionnaire is an instrument provided to enrolled mothers and their partners during the first trimester and second/third trimester of pregnancy. One month after birth, a questionnaire is answered by the mothers and/or partners. Thereafter, questionnaires are administered every six months. Each questionnaire contains a section designated to collect information about chemical exposure, socioeconomic status, lifestyle factors, and physical environment10.

JECS data items used

Data from medical record transcription forms were acquired for the following variables: maternal age, parity, fertilisation method, delivery method, presence or absence of obstetric complications, BMI before pregnancy (less than 18.5 kg/m2, 18.5 to 25 kg/m2, greater than 25 kg/m2), gestational period of the child, gender of the child, presence or absence of birth defects, and presence or absence of analgesia use during delivery. In addition, the cut-off point for obesity in this study, that is, BMI > 25 kg/m2 was the same as that in the profile paper11.

Daily caloric intake in the second/third trimester of pregnancy was determined by the Food Frequency Questionnaire, which is semi-quantitative and has been validated for use in large-scale Japanese epidemiologic studies12. Data were taken from maternal self-administrated questionnaires for the following variables: child nutrition method (e.g., breast milk, mixed, or formula), marital status, drinking habits, smoking habits, exercise habits, presence or absence of second-hand smoke exposure, use of cellular phone or SMS messaging while nursing, presence or absence of early initiation of breastfeeding within one hour of birth, presence or absence of early skin-to-skin contact, presence or absence of rooming-in, depression as assessed by the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) at 1 month postpartum13, presence or absence of negative emotions related to pregnancy, social connections, presence or absence of an opportunity to return to one’s parents, person responsible for household work, presence or absence of starting childcare by the age of 6 months, father’s participation in parenting, presence or absence of confidence in the surroundings, regional social capital, mother’s employment status, household income and education levels of mother and father.

Data were also taken from maternal self-administrated questionnaires at 1 month postpartum for the presence or absence of experiences where the child’s condition worsened while breastfeeding. Worsening of the child’s condition was defined as urticaria, skin changes, redness in and around the mouth, and pallor within an hour of breastfeeding.

Data were also taken from maternal self-administrated questionnaires at 6 months postpartum for the presence or absence of a pet in the household. Presence of a pet was considered to be a factor that would increase the burden on mothers and also affect breastfeeding.

Measurements

Exclusive breastfeeding (EBF)

Mothers who indicated on the JECS self-administered questionnaire form at 6 months postpartum that they practiced continued, uninterrupted exclusive breastfeeding from the first month postpartum to the sixth were placed in the EBF group.

Early initiation of breastfeeding, early skin-to-skin contact, rooming-in

Mothers who responded with answer (1) to the following question on the JECS self-administered questionnaire at 1 month postpartum were regarded as having performed early initiation of breastfeeding: ‘When did you first hold your nipple in your child’s mouth? (1) Within 1 h of birth (2) More than one hour after birth (3) I have not yet had the chance to hold my nipple in my child’s mouth’.

Similarly, individuals who responded with answer (1) to the following question were regarded as having performed early skin-to-skin contact: ‘Did you hold your new-born baby in your arms soon after giving birth? (1) I held my baby so that our skin would touch. (2) I held my baby, but our skin did not touch. (3) I did not hold my baby soon after birth’.

Finally, we used the following question as a scale assessment of rooming-in: ‘In the facility in which you gave birth, how long were you able to stay in the same room as your new-born? (1) Almost no time (2) About a quarter of a day (3) About half of a day (4) About three-quarters of a day (5) We were nearly always together’.

Regional social capital

Social capital is a characteristic—similar to trust, norms, and network—of social organisations that refers to their ability to induce cooperative action in pursuit of a common goal.

The total point value of the responses of pregnant women to the following two questions on the JECS self-administered questionnaire was used to measure social capital: ‘1. The people of my neighbourhood trust each other’ and ‘2. The people of my neighbourhood help each other’. Both questions were asked during the second/third trimester and had the following four potential responses: ‘(1) I believe so (1 point); (2) I would assume so (2 points); (3) I would not assume so (3 points) (4) I do not believe so (4 points)’. Social capital was divided into the following four categories according to the total point values measured: high social capital—2–3 points; medium social capital—4 points; low social capital—5–6 points; very low social capital—7–8 points14.

Analysis

Multiple logistic regression model was used to analyse the data. SAS version 9.4 (SAS institute Inc., Cary, NC) was used for all analyses. Adjusted odds ratios were analysed for all 35 variables. The threshold for statistical significance was 5%, and we performed two-tailed tests. Risk indices have been listed with odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals in the results tables.

Results

Subject characteristics

The 80,491 individuals included in the study had an average age of 31.1 years (± 4.97 years). Of these, 43% were first-time mothers, 81.7% had a vaginal delivery, and 10.0% were obese. Of the total sample, 30,070 individuals (37.4%) continued EBF through to 6 months postpartum (EBF group). The average age of the EBF group was 30.9 years (± 4.74 years). In the EBF group, 36.3% were first-time mothers, 84.6% had a vaginal delivery, and 7.2% were obese.

Of the 35 items postulated to be factors affecting continuing EBF, statistically significant differences were found for 31 items.

Early postpartum nursing prolonged the period of EBF

According to Table 1, the factors related to early postpartum mother–child care were early skin-to-skin contact, early initiation of breastfeeding, and rooming-in; these were extracted as continuation factors for EBF. Initiation of breastfeeding within one hour of birth contributed more strongly to the continuation of EBF than did initiation of breastfeeding more than one hour after birth. Rooming-in for 18–24 h also contributed to the continuation of EBF.

Table 1.

Factors related to early postpartum mother–child care influencing EBF rates until 6 months postpartum in Japan.

| Total number (n) | Percent EBF to 6 months | Odds ratio | 95% confidence interval | Adjusted odds ratio | 95% confidence interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors related to early postpartum mother–child care | ||||||

| Early skin-to-skin contacta (n = 79,822) | ||||||

| No early skin-to-skin contact | 18,315 | 30.1 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Early skin-to-skin contact | 46,349 | 41.5 | 1.647 | (1.588–1.709) | 1.233 | (1.165–1.304) |

| Carried baby against clothes | 15,158 | 33.7 | 1.181 | (1.127–1.236) | 0.994 | (0.932–1.059) |

| Rooming-ina (n = 79,693) | ||||||

| Mother and child separated | 5919 | 26.3 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Roomed-in for one-quarter of a day | 4863 | 29.0 | 1.145 | (1.052–1.246) | 0.923 | (0.834–1.022) |

| Roomed-in for half a day | 7853 | 29.8 | 1.188 | (1.102–1.281) | 1.002 | (0.915–1.098) |

| Roomed-in for three-quarters of a day | 10,781 | 32.7 | 1.356 | (1.264–1.455) | 1.099 | (1.009–1.198) |

| Roomed-in all day | 50,277 | 41.8 | 2.008 | (1.890–2.133) | 1.567 | (1.454–1.690) |

| Early nursinga (n = 79,729) | ||||||

| Not nursed until 1 mo. postpartum | 380 | 16.1 | 0.409 | (0.311–0.538) | 0.637 | (0.410–0.990) |

| Within 1 h of birth | 35,050 | 44.7 | 1.732 | (1.682–1.783) | 1.455 | (1.401–1.512) |

| After 1 h of birth | 44,299 | 31.9 | Reference | Reference | ||

Data acquisition.

a1 month postpartum.

The child started childcare by the age of 6 months shortened the period of EBF

Table 2 shows that the following social factors possibly affected continuation of EBF: presence or absence of confidence in the surroundings, regional social capital, degree of second-hand smoke exposure, whether one’s child had started childcare by 6 months of age, whether there was a return to one’s parents’ house, degree of paternal participation in parenting and who in the household did most of the housework.

Table 2.

Environmental factors influencing EBF rates until 6 months postpartum in Japan.

| Total number (n) | Percent EBF to 6 months | Odds ratio | 95% confidence interval | Adjusted odds ratio | 95% confidence interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child-related factors | ||||||

| Gender of the childd (n = 80,491) | ||||||

| Female | 39,254 | 38.2 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Male | 41,237 | 36.6 | 0.935 | (0.909–0.962) | 0.964 | (0.932–0.997) |

| Gestational periodd (in weekly intervals) | 80,491 | 1.067 | (1.056–1.077) | 1.044 | (1.029–1.059) | |

| Birth defects in the childd (n = 80,491) | ||||||

| Absent | 78,850 | 37.6 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Present | 1641 | 27.7 | 0.638 | (0.572–0.711) | 0.764 | (0.669–0.873) |

| Social factors | ||||||

| Confidencea (n = 79,490) | ||||||

| Never available | 1692 | 37.1 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Rarely available | 5902 | 32.0 | 0.797 | (0.712–0.892) | 0.864 | (0.755–0.990) |

| Somewhat available | 15,960 | 34.3 | 0.884 | (0.797–0.981) | 0.874 | (0.771–0.989) |

| Nearly always available | 8202 | 37.0 | 0.996 | (0.894–1.110) | 0.912 | (0.802–1.039) |

| Always available | 47,734 | 39.2 | 1.094 | (0.990–1.210) | 0.983 | (0.872–1.109) |

| Regional social capitala (n = 78,820) | ||||||

| Extremely low | 16,462 | 34.5 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Low | 22,392 | 35.5 | 1.043 | (1.000–1.088) | 0.992 | (0.943–1.043) |

| Medium | 31,489 | 39.5 | 1.235 | (1.187–1.284) | 1.084 | (1.033–1.138) |

| High | 8477 | 41.2 | 1.328 | (1.259–1.402) | 1.133 | (1.061–1.210) |

| Second-hand smokeb (n = 79,921) | ||||||

| Absent | 38,928 | 39.5 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Smoked outside of the presence of the baby | 39,192 | 35.6 | 0.845 | (0.821–0.870) | 0.952 | (0.917–0.988) |

| Smoked in the presence of the baby | 1801 | 31.4 | 0.699 | (0.632–0.774) | 0.906 | (0.797–1.029) |

| Child attends childcare at 6 monthsc (n = 80,345) | ||||||

| Absent | 74,919 | 39.5 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Present | 5426 | 8.4 | 0.14 | (0.127–0.155) | 0.126 | (0.113–0.141) |

| Returning to one’s parents’ houseb (n = 79,614) | ||||||

| Did not return to parents’ house | 30,608 | 38.2 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Returned home for no more than 1 month | 18,457 | 39.2 | 1.039 | (1.001–1.079) | 1.032 | (0.985–1.081) |

| Returned home for longer than 1 month | 20,871 | 36.6 | 0.930 | (0.897–0.965) | 0.930 | (0.881–0.981) |

| Live together | 9678 | 33.5 | 0.815 | (0.776–0.855) | 0.795 | (0.746–0.848) |

| Did you send your child to a nursery?b (n = 79,193) | ||||||

| No | 61,110 | 39.0 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 18,083 | 32.3 | 0.748 | (0.722–0.774) | 0.712 | (0.683–0.743) |

| Paternal participation in parentingb (n = 79,009) | ||||||

| No participation | 2490 | 37.8 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Participates often | 30,455 | 35.8 | 0.914 | (0.840–0.995) | 0.852 | (0.769–0.945) |

| Participates occasionally | 36,983 | 38.1 | 1.012 | (0.931–1.100) | 0.921 | (0.832–1.018) |

| Almost never participates | 9081 | 41.1 | 1.147 | (1.047–1.257) | 1.043 | (0.935–1.163) |

| Person doing most of the houseworkb (n = 79,919) | ||||||

| Mother herself | 35,168 | 38.0 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Father | 4023 | 35.1 | 0.885 | (0.827–0.948) | 0.961 | (0.886–1.043) |

| Siblings | 228 | 27.6 | 0.625 | (0.467–0.835) | 0.794 | (0.547–1.153) |

| Maternal grandmother | 33,749 | 37.5 | 0.983 | (0.953–1.014) | 0.971 | (0.928–1.015) |

| Maternal grandfather | 364 | 31.3 | 0.746 | (0.597–0.932) | 0.739 | (0.565–0.967) |

| Paternal grandmother | 5219 | 36.8 | 0.953 | (0.897–1.012) | 0.928 | (0.859–1.001) |

| Paternal grandfather | 55 | 36.4 | 0.934 | (0.539–1.619) | 0.799 | (0.415–1.536) |

| Other, not listed above | 1113 | 31.6 | 0.756 | (0.665–0.860) | 0.854 | (0.731–0.999) |

Data acquisition.

aDuring mid-pregnancy/ b1 month postpartum/ c6 months postpartum/ dattending physician diagnosed just after delivery.

Among the 35 factors examined, the child starting childcare by the age of 6 months was found to be the most inhibiting. ‘Rarely available’ and ‘somewhat available’ confidences as compared to the absence of a confidence, were also inhibitory factors for EBF continuation. Further, close relatives’ smoking outside of the baby’s presence was an inhibiting factor. With regard to return to one’s parents’ house, a return for longer than 1 month or situations in which the mother lived with her parents were found to inhibit continuation of EBF. The greater the father’s participation in parenting, the more inhibitory it was for EBF continuation. Finally, situations in which the maternal grandfather was primarily responsible for housework were found to be inhibitory for EBF. The only social factor found to contribute to EBF continuation was medium to high regional social capital.

Full term and female babies were more likely to be breastfed

According to Table 2, the following child related variables were found to support EBF continuation: gender, gestational period, and presence or absence of birth defects. Males were less likely than females to be exclusively breastfed to 6 months. The presence of birth defects was also found to be an inhibitory factor of EBF continuation. Additionally, the longer a child’s gestational period (measured in weeks), the more it contributed to the continuation of EBF.

Negative social demographic factors obstructed EBF

Table 3 shows that the following social demographic factors contributed to the continuation of EBF: maternal age, maternal education level, paternal education level, maternal employment status, and parental marital status. The higher a mother’s age was (to the nearest year), the more it contributed to the inhibition of EBF continuation. With regard to maternal education level, mothers that graduated from vocational school, community college or a university were more likely to continue EBF. Paternal education level was associated in the same way with EBF. Mothers who were housewives and on leave from work were more likely to continue EBF than full-time employed mothers. Finally, divorce from or death of the husband was an inhibitory factor of EBF continuation compared to being married.

Table 3.

Personal factors influencing EBF rates until 6 months postpartum in Japan.

| Total number (n) | Percent EBF to 6 months | Odds ratio | 95% confidence interval | Adjusted odds ratio | 95% confidence interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social demographic factors | ||||||

| Age of the mothere (by year) | 79,950 | 0.984 | (0.981–0.987) | 0.957 | (0.953–0.961) | |

| Household incomeb (n = 74,424) | ||||||

| Less than 4 million yen | 29,078 | 35.9 | Reference | Reference | ||

| 4–6 million yen | 24,858 | 38.5 | 1.117 | (1.079–1.157) | 1.022 | (0.980–1.066) |

| Greater than 6 million yen | 20,488 | 39.3 | 1.156 | (1.114–1.199) | 1.049 | (0.998–1.102) |

| Mother’s level of educationb (n = 79,533) | ||||||

| Middle/High school graduate | 27,207 | 32.7 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Vocational school/ Community college graduate | 34,396 | 38.4 | 1.285 | (1.243–1.328) | 1.188 | (1.138–1.240) |

| College/University graduate or higher | 17,930 | 42.7 | 1.535 | (1.476–1.596) | 1.322 | (1.253–1.395) |

| Father’s level of educationb (n = 79,066) | ||||||

| Middle/High school graduate | 33,685 | 34.1 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Vocational school/Community college graduate | 18,153 | 38.6 | 1.213 | (1.169–1.259) | 1.079 | (1.031–1.129) |

| College/University graduate or higher | 27,228 | 41.0 | 1.342 | (1.298–1.387) | 1.104 | (1.057–1.154) |

| Mother’s employment statusb (n = 79,277) | ||||||

| Full‐time | 25,313 | 36.8 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Self‐employed or its assistant | 2765 | 35.8 | 0.956 | (0.881–1.038) | 1.074 | (0.972–1.186) |

| Temporary staff | 1038 | 30.2 | 0.741 | (0.648–0.849) | 0.863 | (0.733–1.015) |

| Housewife or on leave | 34,696 | 40.4 | 1.163 | (1.125–1.202) | 1.045 | (1.000–1.092) |

| Part‐time/Side job/Commission | 12,890 | 33.1 | 0.848 | (0.811–0.887) | 0.954 | (0.902–1.009) |

| Unemployed | 1035 | 29.7 | 0.724 | (0.632–0.830) | 0.927 | (0.777–1.107) |

| Other | 1540 | 31.5 | 0.790 | (0.707–0.882) | 0.852 | (0.746–0.972) |

| Marital statusa (n = 79,685) | ||||||

| Married | 76,349 | 37.8 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Unmarried | 2751 | 30.4 | 0.718 | (0.661–0.780) | 0.997 | (0.889–1.119) |

| Divorced/widowed | 585 | 23.3 | 0.500 | (0.412–0.606) | 0.683 | (0.523–0.892) |

| Maternal lifestyle factors | ||||||

| Daily calorie intakeb (per 1000 kcal) | 79,951 | 1.020 | (1.001–1.039) | 0.995 | (0.971–1.019) | |

| Drinking habitsb (n = 79,355) | ||||||

| None | 26,513 | 38.3 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Stopped before pregnancy | 13,069 | 39.8 | 1.068 | (1.023–1.115) | 1.039 | (0.988–1.094) |

| Stopped after discovering pregnancy | 37,621 | 36.1 | 0.910 | (0.881–0.940) | 0.967 | (0.930–1.006) |

| Continued during pregnancy | 2152 | 36.3 | 0.918 | (0.838–1.006) | 0.995 | (0.892–1.110) |

| Smoking habitsc (n = 79,851) | ||||||

| None | 47,750 | 39.5 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Stopped before pregnancy | 18,092 | 38.5 | 0.960 | (0.927–0.995) | 1.016 | (0.973–1.061) |

| Stopped after discovering pregnancy | 11,361 | 30.3 | 0.666 | (0.637–0.696) | 0.796 | (0.751–0.842) |

| Continued during pregnancy | 2648 | 22.1 | 0.434 | (0.395–0.477) | 0.557 | (0.496–0.627) |

| Exercise habitsb (n = 79,704) | ||||||

| No exercise habits | 19,189 | 35.4 | Reference | Reference | ||

| At least 10 min of exercise (walking) weekly | 60,515 | 38.1 | 1.12 | (1.082–1.158) | 1.074 | (1.031–1.118) |

| Household petd (n = 80,194) | ||||||

| Absent | 60,435 | 38.6 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Present | 19,759 | 33.9 | 0.817 | (0.79–0.845) | 0.907 | (0.870–0.946) |

| Factors related to maternal behavior during nursing | ||||||

| Experience of child’s condition worsening during breastfeedingc (n = 79,200) | ||||||

| Absent | 77,568 | 37.5 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Present | 1632 | 39.9 | 1.107 | (1.002–1.224) | 1.144 | (1.014–1.290) |

| Activities of the mother during nursingc (n = 79,143) | ||||||

| Looked into the eyes of and talked with child | 57,340 | 36.7 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Often watch TV or a DVD | 12,299 | 37.0 | 1.014 | (0.974–1.056) | 0.954 | (0.910–1.001) |

| Reading newspapers or magazines | 510 | 44.7 | 1.394 | (1.170–1.662) | 1.130 | (0.924–1.381) |

| Used cellphones or a PC | 6037 | 40.0 | 1.148 | (1.087–1.212) | 1.101 | (1.031–1.175) |

| Did housework | 74 | 18.9 | 0.405 | (0.227–0.724) | 0.420 | (0.203–0.868) |

| Something other than the above | 2883 | 46.5 | 1.500 | (1.391–1.617) | 1.136 | (1.039–1.242) |

Data acquisition.

aDuring early pregnancy/ bduring mid-pregnancy/ c1 month postpartum/ d6 months postpartum/ eattending physician diagnosed just after delivery.

Having a household pet reduced the period of EBF

Based on Table 3, the following maternal lifestyle factors were found to be involved in the continuation of EBF: smoking habits, exercise habits, and having a household pet. Smoking was found to be an inhibitory factor of EBF continuation, even if the mother stopped smoking after discovering pregnancy. Engaging in a minimum of 10 min per week of light exercise (e.g., walking) was found to be a supporting factor of EBF continuation. Finally, the presence of a household pet was associated with a lower prevalence of EBF continuation. Each factor was tested for multicollinearity, and domestic violence was removed from the results because of the multicollinear relationship between smoking and domestic violence.

EBF mothers were more likely to have looked at a computer or cell phone while breastfeeding

Table 3 shows experience of the child’s condition worsening during breastfeeding, and the use of one’s mobile phone or PC during nursing were found to support the continuation of EBF. On the other hand, housework during nursing was found to be an inhibitory factor of EBF continuation.

Obesity in pregnancy reduced the period of EBF

Table 4 shows that the following maternal physical factors were found to influence EBF continuation: BMI and Parity. A BMI of 25 or greater indicating obesity was an inhibitory factor for EBF continuation. Multiparity was found to support EBF continuation.

Table 4.

Maternal physical, psychological and medical factors influencing EBF rates until 6 months postpartum in Japan.

| Total number (n) | Percent EBF to 6 months | Odds ratio | 95% confidence interval | Adjusted odds ratio | 95% confidence interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal physical factors | ||||||

| BMIc (n = 80,435) | ||||||

| 18.5–25 kg/m2 | 59,392 | 38.5 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Less than 18.5 kg/m2 | 13,033 | 38.6 | 1.005 | (0.966–1.045) | 0.983 | (0.938–1.030) |

| Greater than 25 kg/m2 | 8010 | 27.0 | 0.592 | (0.562–0.623) | 0.667 | (0.627–0.710) |

| Parityc (n = 78,507) | ||||||

| Primipara | 33,725 | 31.7 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Multipara | 44,782 | 41.8 | 1.550 | (1.505–1.597) | 1.812 | (1.737–1.891) |

| Obstetrical complicationsc (n = 79,874) | ||||||

| Absent | 68,071 | 37.7 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Present | 11,803 | 35.4 | 0.905 | (0.869–0.943) | 1.028 | (0.979–1.079) |

| Maternal psychological factors | ||||||

| Edinburgh scale scoreb (n = 79,000) | ||||||

| Less than 9 | 68,200 | 38.9 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Greater than or equal to 9 | 10,800 | 28.3 | 0.622 | (0.595–0.651) | 0.716 | (0.678–0.756) |

| Negative emotions towards pregnancya (n = 79,655) | ||||||

| Absent | 74,029 | 37.8 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Present | 5626 | 32.1 | 0.778 | (0.734–0.824) | 0.906 | (0.844–0.972) |

| Medical factors | ||||||

| Delivery methodc (n = 80,352) | ||||||

| Vaginal delivery | 65,672 | 38.7 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Caesarean section | 14,680 | 31.5 | 0.730 | (0.702–0.758) | 1.161 | (1.092–1.233) |

| Analgesics during deliveryc (n = 79,069) | ||||||

| Absent | 77,177 | 37.6 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Present | 1892 | 29.0 | 0.678 | (0.613–0.749) | 0.814 | (0.723–0.916) |

| Infertility treatmentsa (n = 79,649) | ||||||

| Absent | 72,276 | 38.0 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Present | 7373 | 31.3 | 0.744 | (0.706–0.783) | 0.853 | (0.802–0.908) |

Data acquisition.

aDuring early pregnancy/ b1 month postpartum/ cattending physician diagnosed just after delivery.

An unsettled state of mind in pregnancy reduced the period of EBF

According to Table 4, the following maternal psychological factors were found to be inhibitory toward EBF continuation: negative emotions toward pregnancy and a score of 9 or greater on the EPDS.

Medical intervention during the perinatal period tended to restrict EBF

Based on Table 4, the following medical factors were found to be involved in EBF continuation: delivery method, use of analgesics during delivery, and engagement in infertility treatments. Caesarean section delivery (more so than vaginal delivery) tended to be positively associated with EBF at 6 months. Analgesic use during delivery and infertility medications were found to be inhibitory factors of EBF continuation.

Discussion

This large-scale cohort study clarified the factors involved in EBF continuation through to 6 months postpartum. In particular, the early initiation of breastfeeding—within one hour of birth—was shown to contribute greatly. Many previous studies15 have shown that early initiation of breastfeeding and early skin-to-skin contact are the keys to successful breastfeeding, and this study showed similar results. In addition, previously published research has indicated various factors as being effective in promoting the continuation of EBF including rooming-in16,17, education level18, presence of a child supporter19 and Parity20 and so on. In this study, as in the previous studies, the above factors were found to contribute to breastfeeding.

The higher the rate of EBF at 6 months, the greater the benefit to maternal and infant health and the greater the significance from a public health perspective. Therefore, the Global Breastfeeding Collective of UNICEF/WHO aims to increase the percentage of babies under 6 months old exclusively breastfed from 4421 to 70% by 203022. The prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding in Japan at 3 months is 54.7%4 and at 6 months is 37.4%. These percentages are not high. However, the results of this study have provided several hints to increase the percentage of EBF.

The results of the present study revealed newly discovered factors influencing the continuation of EBF, such as regional social capital during pregnancy and ownership of a household pet. High regional social capital tends to associate with high levels of health among the residents of the region23. This study has revealed that high regional social capital was associated with a high breastfeeding rate, meaning that high regional social capital influences mother–child health. This discovery indicates that activities that seek to promote regional social capital may also have beneficial effects for maternal and child health.

Besides, previous research has shown that dog ownership has a positive effect on child development, so we considered it as a variable24. However, we found that pet ownership interfered with breastfeeding. Raising pets increases the burden on mothers, which results in mothers spending less time with their children. This also reduces the amount of time spent slowly feeding breast milk, which may have been extracted as a factor in reducing breastfeeding rates.

Regarding other factors, as reported in previously published research, our study found that the mother’s education level is positively associated with the continuation of EBF. According to literature, mothers who decide to engage in EBF inform themselves to a greater degree about nutrition and diet, consult more frequently with their doctors, and have better access to information on the health of nursing children than mothers who do not engage in EBF25. It may be the case that the higher a mother’s education level, the more aware she is of the merits of EBF and, therefore, her motivation to implement it is higher.

Regarding support in the parenting process, our research indicated that the father’s participation in parenting is negatively associated with continued EBF. This runs contrary to associations reported by other researchers26. It is very common for parents to supplement milk with a baby bottle, and this situation can make it easy for fathers to help with feeding. Therefore, it is thought that bottle feeding resulted in a higher rate of father participation in childcare, including with feeding. Nevertheless, in the context of the continuation of EBF, the importance of a childcare supporter has been made clear by previously published work27.

Regarding activities while nursing, it is generally believed that looking into the eyes of the child is beneficial from the perspective of forming an attachment with the child28, but the results of this study, there was no association between looking into the eyes of the child and the duration of EBF. Instead, we saw a trend that mothers who breastfed while looking at the newspaper or a mobile phone continued to EBF for longer. This suggests that for mothers who continue to EBF, breastfeeding itself is as integrated into their lives as looking at the newspaper or mobile phone. Since one hand is free while breastfeeding, simple actions that can be done with one hand can be done at the same time. However, for parents who are mixed feeding, it becomes difficult to look at the newspaper or a phone while feeding because both hands are required (to hold the baby and to hold the bottle). This may explain why the percentage of the EBF group who looked at a newspaper or mobile phone with one free hand while breastfeeding was higher than that for the mixed feeding group.

In this study, Caesarean sections were found to be positively associated with EBF at 6 months, which is inconsistent with the direction of association reported in most other studies. Many studies examining Caesarean sections and breastfeeding rates have examined breastfeeding rates less than 3 months postpartum as an endpoint29, but our study examined a relatively long breastfeeding period, with 6 months as an endpoint. The results of this study suggest that the period during which Caesarean section interferes with breastfeeding may be a relatively short period after delivery. In other words, mothers who gave birth by Caesarean section are likely to have difficulties in breastfeeding during the first 3 months after delivery, but after 3 months, they may be able to continue breastfeeding and the fact that they have undergone a Caesarean section does not interfere with EBF.

Reports on factors involved in the inhibition of EBF continuation include the following: low household income30, obesity31,32, engagement in smoking33, presence of domestic violence34, low birth weight35, use of epidural anaesthetics36 and a high EPDS score37. These factors were found to inhibit EBF in our research as well.

Other factors found to inhibit EBF continuation in this study were that the child started childcare, mother smoking, and obesity in early pregnancy. Among these, the child starting childcare by the age of 6 months or younger was found to inhibit EBF continuation most profoundly. Previously published research has indicated that even if a mother is employed full-time—a factor known to affect breastfeeding—giving one’s child over to another’s care before 6 months of age is associated with the cessation of breastfeeding37,38. The primary reason that necessitates the handing over of one’s child to another’s care is a mother’s need to return to her workplace39. The Japanese maternity leave system offers 8 weeks after giving birth, with the possibility of focusing on childcare for up to 1 year with some degree of paid salary if the mother is able to obtain childcare leave. The International Labour Organization recommends providing mothers with at least 18 weeks of maternity leave and 100% payment of salary during that period40, but this practice is yet to be enforced within Japan41. The child starting childcare makes the continuation of EBF quite difficult; mothers should receive at least 6 months of maternal leave. Alternatively, arrangements ought to be made to allow mothers who return to work before 6 months postpartum to bring their children with them to the workplace. This is because children that are breastfed rely exclusively on breast milk for their nutrition and require frequent feeding. Besides, many nurseries do not accept breast milk for hygiene reasons in Japan42. This makes exclusive breastfeeding difficult. Furthermore, the main reason for starting childcare is the mother's return to work. While a mother's return to work is not in itself an impediment to breastfeeding, the fact that she will no longer be able to breastfeed as often as she has been able to in the workplace is a problem for her to continue breastfeeding.

The potential implications of providing new mothers with an environment in which they can respond to their infants’ needs quickly include the rise of birth rates. Society at large—not just mothers and children—will benefit greatly from the windfall of such a change. If Japan truly intends to bring its EBF rate in line with the global benchmark, it is necessary to improve early postpartum care and overhaul the current maternity leave system.

There were several limitations in our research. First, the questions polling about initiation of breastfeeding within one hour of delivery, early skin-to-skin contact, and mother–child rooming-in were asked one month after birth; the answers were therefore subject to errors in recall, and their accuracy cannot be guaranteed. Similarly, mothers were asked to declare whether they engaged in EBF 6 months postpartum—they needed to look back on 6 months of childcare and remember their habits. This, too, may have introduced some unreliability into our data. However, because the number of cases we examined is quite large, the unreliability of a few answers should not affect our results in any meaningful way. Second, our participants were all mothers living in Japan; thus, generalising our findings to the global situation is difficult. Third, because the answers to the factor items (the independent variables) and the answers reporting EBF (the dependent variable) were collected at different times, caution regarding their cause-and-effect relationship is essential to the proper interpretation of our results. Finally, because this was a large-scale survey, it is possible that some spurious findings were discovered.

In conclusion, early postpartum mother–child care—initiation of breastfeeding within one hour of birth, early skin-to-skin contact, and rooming-in—was found to contribute greatly to the continuation of EBF till 6 months postpartum. In addition, high social capital was found to effectively promote continuation of EBF. On the other hand, the child starting childcare was found to greatly inhibit continuation of EBF. Hence, these findings suggest a necessity to provide a minimum of 6 months maternity leave and to provide mother–child support in care protocols in order to raise the rate of Japanese EBF during 0–5 months of age up to 70%.

Ethics approval

The study protocol was approved by the Ministry of the Environment’s Institutional Review Board on Epidemiological Studies and by the Ethics Committee of all participating institutions. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the participants of JECS and to all individuals involved in data collection. The Japan Environment and Children’s Study was funded by the Ministry of the Environment, Japan. The findings and conclusions of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official views of the above government agency.

Author contributions

H.I. and A.T. drafted the paper. M.K., T.H., K.S., and H.I. conceived and designed the study. K.M. and A.T. analysed the data. A.T., K.M., H.I., K.H., and JECS group critically reviewed the draft and checked the analysis. JECS group collected the data and obtained the funding. All authors approved the submission of the manuscript in its current form.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

A list of authors and their affiliations appears at the end of the paper.

Contributor Information

Tomomi Hasegawa, Email: thase@med.u-toyama.ac.jp.

The Japan Environment and Children’s Study (JECS) Group:

Michihiro Kamijima, Shin Yamazaki, Yukihiro Ohya, Reiko Kishi, Nobuo Yaegashi, Koichi Hashimoto, Chisato Mori, Shuichi Ito, Zentaro Yamagata, Takeo Nakayama, Hiroyasu Iso, Masayuki Shima, Youichi Kurozawa, Narufumi Suganuma, Koichi Kusuhara, and Takahiko Katoh

References

- 1.Victora CG, et al. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: Epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet. 2016;387:475–490. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Academy of Pediatrics Section on breastfeeding: Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2012;129(3):e827–e841. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Protecting, Promoting and Supporting Breastfeeding in Facilities Providing Maternity and Newborn Services. https://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/guidelines/breastfeeding-facilities-maternity-newborn/en/ (2017). [PubMed]

- 4.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. National Nutrition Survey on Preschool Children, https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/0000134208.html (2015).

- 5.Dubois L, Girard M. Social determinants of initiation, duration and exclusivity of breastfeeding at the population level: The results of the Longitudinal Study of Child Development in Quebec (ELDEQ 1998–2002) Can. J. Public Health. 2003;94:300–305. doi: 10.1007/BF03403610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonuck KA, Freeman K, Trombley M. Country of origin and race/ethnicity: Impact on breastfeeding intentions. J. Hum. Lact. 2005;21:320–326. doi: 10.1177/0890334405278249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Di Napoli A, Di Lallo D, Pezzotti P, Forastiere F, Porta D. Effects of parental smoking and level of education on initiation and duration of breastfeeding. Acta Paediatr. 2006;95:678–685. doi: 10.1080/08035250600580578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Napierala M, Mazela J, Merritt TA, Florek E. Tobacco smoking and breastfeeding: Effect on the lactation process, breast milk composition and infant development. A critical review. Environ. Res. 2016;151:321–338. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2016.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mangrio E, Persson K, Bramhagen AC. Sociodemographic, physical, mental and social factors in the cessation of breastfeeding before 6 months: a systematic review. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2017;32(2):451–465. doi: 10.1111/scs.12489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kawamoto T, et al. Rationale and study design of the Japan environment and children's study (JECS) BMC Public Health. 2014;14:25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Michikawa T, et al. Baseline profile of participants in the Japan Environment and Children's Study (JECS) J. Epidemiol. 2018;28:99–104. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20170018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yokoyama Y, et al. Validity of short and long self-administered food frequency questionnaires in ranking dietary intake in middle-aged and elderly Japanese in the Japan Public Health Center-Based Prospective Study for the Next Generation (JPHCAESARIANNEXT) protocol area. J. Epidemiol. 2016;26:420–432. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20150064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okano T, et al. Validation and reliability of Japanese version of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) Arch. Pychiatr. Diagn. Clin. Eval. 1996;7(4):523–533. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mizuno S, et al. Association between social capital and the prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus: An interim report of the Japan Environment and Children's Study. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2016;120:132–141. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2016.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Righard L, Alade MO. Effect of delivery room routines on success of first breast-feed. Lancet. 1990;336:1105–1107. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)92579-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jaafar SH, Ho JJ, Lee KS. Rooming-in for new mother and infant versus separate care for increasing the duration of breastfeeding. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006641.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamauchi Y, Yamanouchi I. The relationship between rooming-in/not rooming-in and breast-feeding variables. Acta Paediatr. Scand. 1990;79:1017–1022. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1990.tb11377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oakley LL, Henderson J, Redshaw M, Quigley MA. The role of support and other factors in early breastfeeding cessation: An analysis of data from a maternity survey in England. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:88. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rousseau EH, Lescop JN, Fontaine S, Lambert J, Roy CC. Influence of cultural and environmental factors on breast-feeding. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 1982;127:701–704. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tarrant M, et al. Breastfeeding and weaning practices among Hong Kong mothers: A prospective study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2010;10:27. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-10-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.UNICEF Data: Infant and young child feeding, https://data.unicef.org/topic/nutrition/infant-and-young-child-feeding/ (2019).

- 22.UNICEF & Word Health Organization. Enabling Women to Breastfeed Through Better Policies and Programmes; Global Breastfeeding Scorecard, 2018. https://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/infantfeeding/global-bf-scorecard-2018.pdf?ua=1 (2018).

- 23.Kawachi I, Kennedy BP, Glass R. Social capital and self-rated health: A contextual analysis. Am. J. Public Health. 1999;89:1187–1193. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.8.1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Minatoya M, et al. Cat and dog ownership in early life and infant development: A prospective birth cohort study of Japan Environment and Children's Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2019;17:205. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17010205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raissian KM, Su JH. The best of intentions: Prenatal breastfeeding intentions and infant health. SSM Popul. Health. 2018;5:86–100. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2018.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mahesh PKB, et al. Effectiveness of targeting fathers for breastfeeding promotion: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:1140. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-6037-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaneko A, et al. Factors associated with exclusive breast-feeding in Japan: For activities to support child-rearing with breast-feeding. J. Epidemiol. 2006;16:57–63. doi: 10.2188/jea.16.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robson KS. The role of eye-to-eye contact in maternal–infant attachment. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 1967;8(1):13–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1967.tb02176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hobbs AJ, Mannion CA, McDonald SW, Brockway M, Tough SC. The impact of Caesarean section on breastfeeding initiation, duration and difficulties in the first four months postpartum. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16:90. doi: 10.1186/s12884-016-0876-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hauck YL, Fenwick J, Dhaliwal SS, Butt J. A Western Australian survey of breastfeeding initiation, prevalence and early cessation patterns. Matern. Child Health J. 2011;15:260–268. doi: 10.1007/s10995-009-0554-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kronborg H, Vaeth M, Rasmussen KM. Obesity and early cessation of breastfeeding in Denmark. Eur. J. Public Health. 2013;23:316–322. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cks135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ayton J, van der Mei I, Wills K, Hansen E, Nelson M. Cumulative risks and cessation of exclusive breast feeding: Australian cross-sectional survey. Arch. Dis. Child. 2015;100:863–868. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2014-307833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu J, Rosenberg KD, Sandoval AP. Breastfeeding duration and perinatal cigarette smoking in a population-based cohort. Am. J. Public Health. 2006;96:309–314. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.060798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moraes CL, de Oliveira AS, Reichenheim ME, Lobato G. Severe physical violence between intimate partners during pregnancy: A risk factor for early cessation of exclusive breast-feeding. Public Health Nutr. 2011;14:2148–2155. doi: 10.1017/S1368980011000802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khanal V, Scott JA, Lee AH, Karkee R, Binns CW. Factors associated with early initiation of breastfeeding in Western Nepal. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2015;12:9562–9574. doi: 10.3390/ijerph120809562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dozier AM, et al. Labor epidural anesthesia, obstetric factors and breastfeeding cessation. Matern. Child Health J. 2013;17:689–698. doi: 10.1007/s10995-012-1045-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bick DE, MacArthur C, Lancashire RJ. What influences the uptake and early cessation of breast feeding? Midwifery. 1998;14:242–247. doi: 10.1016/s0266-6138(98)90096-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Avery M, Duckett L, Dodgson J, Savik K, Henly SJ. Factors associated with very early weaning among primiparas intending to breastfeed. Matern. Child Health J. 1998;2:167–179. doi: 10.1023/a:1021879227044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chuang CH, et al. Maternal return to work and breastfeeding: A population-based cohort study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2010;47:461–474. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.UNICEF & World Health Organization. Tracking Progress for Breastfeeding Policies and Programmes; Global Breastfeeding Scorecard, 2017. https://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/infantfeeding/global-bf-scorecard-2017.pdf?ua=1 (2017).

- 41.International Labor Organization. C183—Maternity Protection Convention, 2000 (No. 183), https://www.ilo.org/tokyo/standards/list-of-conventions/WCMS_239185/lang--ja/index.htm (2000).

- 42.Ohyama M, Furuya M. Treatment of stored breast milk in public day care centers—Results from a Questionnaire Survey on Local Municipality Officers in Kanagawa Prefecture. Pediatr. Health Res. 2006;65:348–356. [Google Scholar]