Abstract

Purpose

We sought to assess the impact of disruptions due to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) on caregivers of childhood cancer survivors.

Methods

A 13‐question survey containing multiple‐choice, Likert‐type, and free‐text questions on experiences, behaviors, and attitudes during the COVID‐19 outbreak was sent to childhood cancer caregivers and completed between April 13 and May 17, 2020. Ordered logistic regression was used to investigate relationships between demographics, COVID‐related experiences, and caregiver well‐being.

Results

Caregivers from 321 unique families completed the survey, including 175 with children under active surveillance/follow‐up care and 146 with children no longer receiving oncology care. Overall, caregivers expressed exceptional resiliency, highlighting commonalities between caring for a child with cancer and adopting COVID‐19 prophylactic measures. However, respondents reported delayed/canceled appointments (50%) and delayed/canceled imaging (19%). Eleven percent of caregivers reported struggling to pay for basic needs, which was associated with greater disruption to daily life, greater feelings of anxiety, poorer sleep, and less access to social support (p < .05). Caregivers who were self‐isolating reported greater feelings of anxiety and poorer sleep (p < .05). Respondents who expressed confidence in the government response to COVID‐19 reported less disruption to their daily life, decreased feelings of depression and anxiety, better sleep, and greater hopefulness (p < .001)

Conclusions

Caregivers are experiencing changes to medical care, financial disruptions, and emotional distress due to COVID‐19. To better serve caregivers and medically at‐risk children, clinicians must evaluate financial toxicity and feelings of isolation in families affected by childhood cancer, and work to provide reliable information on how COVID‐19 may differentially impact their children.

Keywords: access to care, childhood cancer, COVID‐19, parental distress, psychological harm, SARS‐CoV‐2

Abbreviations

- ALSF

Alex's Lemonade Stand Foundation

- CCS

survivors of childhood cancer

- COVID‐19

coronavirus disease 2019

- MCC

My Childhood Cancer

- SARS‐CoV‐2

severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

1. INTRODUCTION

Early 2020 saw the emergence of a global pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19), caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2). 1 Existing evidence in the general population indicates older individuals and those with comorbid chronic conditions are at higher risk for SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, severe disease, and death. 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 Cancer patients may also be at increased risk of adverse outcomes if infected, 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 though morbidity and mortality appear to vary across tumor histology and treatment status. 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 While recent small studies suggest that pediatric patients with cancer may not be more vulnerable than other children to infection or morbidity from SARS‐CoV‐2, 17 , 18 other studies suggest that children with hematologic malignancies may have a more severe course of COVID‐19 illness. 19

There is less evidence on the physical and mental effects of COVID‐19 in cancer survivors and their caregivers. 20 Emerging evidence indicates cancer survivors are experiencing persistent, increased psychological distress and reduced access to social support as a result of COVID‐19. 21 , 22 , 23 However, there are scarce data on this topic in survivors of childhood cancer (CCS), who frequently have multiple treatment‐related chronic conditions, including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and reduced immune function, 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 and who are at increased risk of both infection and postinfection complications relative to the general population. 29 , 30 While evidence from a cohort of 281 CCS in New York City observed low overall rates of infection and hospitalization, 31 the financial and psychosocial impacts of COVID‐19 in CCS and their caregivers remains poorly described. 32 This presents challenges for communicating risks to caregivers and to coordinating surveillance and follow‐up care in this vulnerable population.

Several pediatric cancer consortia have published COVID‐19 guidance for CCS and health care providers. 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 Pediatric oncology teams have responded by limiting off‐therapy clinical evaluations, resulting in postponement of long‐term surveillance and follow‐up appointments. 32 Delayed tumor diagnosis has been indicated elsewhere as a potential collateral effect of necessary COVID‐19 care modifications. 37 Likewise, delays in routine imaging and follow‐up care could impede diagnosis of surfacing late effects and may negatively impact patient health and caregiver psychological distress. 38 , 39 Caregivers of CCS may be experiencing increased anxiety, distress, and exacerbated posttraumatic symptoms during COVID‐19. 40 Therefore, how the pandemic continues to impact CCS and their caregivers—from changes in clinical care to financial and emotional consequences—merits targeted evaluation. We partnered with the Alex's Lemonade Stand Foundation (ALSF) to conduct a rapid survey of the US‐based caregivers of CCS. We explored how the pandemic has impacted CCS medical care, health behaviors, household finances, and caregiver psychosocial well‐being. We also examined relationships between caregiver psychosocial outcomes and several potential correlates, including CCS and caregiver demographic factors, financial distress, social isolating behaviors, primary sources of information on the pandemic, and confidence in the government and medical community's responses to COVID‐19.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study population

To explore the physical and emotional consequences of a childhood cancer diagnosis and cancer therapy on the family unit, we partnered with ALSF to conduct an ongoing series of longitudinal surveys of families affected by childhood cancer. Initiated in 2011, the ALSF My Childhood Cancer (MCC) Survey Series explores families’ experiences and attitudes from diagnosis, throughout treatment and follow‐up care, and after bereavement. MCC targets parental respondents whose child was diagnosed with cancer before their 18th birthday. Participation in MCC is not limited by the child's current age, only their age at diagnosis. To date, 3150 unique families have participated in the MCC Survey Series.

Families were eligible to participate in the COVID‐19 survey if they had a child diagnosed with cancer who was still living, had previously completed the MCC registration survey, and had logged into the MCC portal at least once since January 1, 2019 (N = 1089). Only one survey response was recorded per family. In the event that more than one caregiver from the same family completed the questionnaire, the first completed survey was retained. Analyses presented here are limited to the US‐based respondents whose child was not actively being treated for cancer. MCC registration survey data include cancer type, family structure, and patient and caregiver demographics. This study was approved by the Duke University institutional review board (Pro00100771).

2.2. Survey development

We developed a 13‐question survey to collect information on respondents’ experiences, behaviors, and attitudes during the COVID‐19 outbreak. The short survey was distributed via an emailed link to eligible MCC participants. The survey was sent on April 13 and closed on May 17, 2020 (34 days). Survey questions explored ways in which the COVID‐19 outbreak had affected or was anticipated to affect the child's medical care, steps respondents were taking to reduce SARS‐CoV‐2 infection risks, primary sources of information on COVID‐19, and indicators of mental and somatic well‐being. Questions included multiple‐choice, Likert‐type, and free‐text questions adapted from a COVID‐related update to the “Parenting Across Cultures” survey—a longitudinal study of mothers, fathers, and youth in nine countries. 41 The full questionnaire is available in Supporting Resource 1.

Both dependent and independent variables were derived from survey questions. Dependent variables included six measures of parental psychosocial experiences during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Parents were asked to rate on a 1–9 scale how disruptive the COVID‐19 outbreak had been to their daily routines, work, and family life. Parents also rated their level of agreement (strongly disagree, somewhat disagree, somewhat agree, strongly agree), with five statements regarding their attitudes and behaviors during the COVID‐19 outbreak compared to those before the outbreak, including feeling more sad/depressed, feeling more anxious, sleeping about as well as before the outbreak, experiencing reduced access to social support, feeling hopeful that the outbreak will resolve, and having a good outlook toward the future.

Independent variables included the child's treatment status (“surveillance/follow‐up care” vs. “treatment/surveillance completed”), child's cancer type, the caregiver respondent's sex, whether the family was self‐isolating, whether the child had transitioned to telehealth visits, caregivers’ primary sources of information for COVID‐19 (e.g., government, social media, cancer care professionals), whether the family was experiencing difficulty paying for basic needs, whether their child was receiving care exclusively at a freestanding children's hospital, caregiver confidence in the government response to COVID‐19, and caregiver confidence in hospitals’ and physicians’ responses to COVID‐19.

Additional data collected in the survey but not included in regression models either did not show substantial variability across respondents or were collected for purposes outside the scope of this analysis (e.g., an ALSF COVID‐19 needs assessment, travel difficulties of caregivers with children in active treatment).

2.3. Statistical analysis

Relationships between independent and dependent variables were assessed using ordered logistic regression. The proportional odds model assumes that the effects of predictor variables are consistent across levels of the outcome variable (e.g., when moving from “strongly disagree” to “somewhat disagree,” from “somewhat disagree” to “somewhat agree,” etc.). To test appropriateness of model fit, we performed logistic regression with the four‐level responses (e.g., strongly disagree, somewhat disagree, somewhat agree, strongly agree) and ordinary least squares regression for the disruption outcome (i.e., 1–9). Given that this assumption was met, our models have improved statistical power when outcomes are treated as ordinal rather than binary variables (i.e., agree vs. disagree) and were analyzed accordingly.

For all statistical tests, α = .05 was used to determine nominal statistical significance. p‐Values < 5.56 × 10–4 (representing a Bonferroni correction for 90 total tests) are specifically noted in tables. Stata 16.1 was used for data analysis and R3.6.3 for data visualization. Confidence limits for binomial proportions were estimated using the Wilson score interval.

Free‐text responses were analyzed by two investigators to identify common themes. The investigators met interactively to refine themes and develop a codebook for qualitative analysis. 42 Free‐text responses were coded in parallel and differences were resolved through discussion. 43 Final themes were reviewed and supportive responses de‐identified for publication.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Study population

A total of 360 caregivers completed the survey over the 34‐day window (33%). After excluding non‐US respondents (N = 15) and caregivers with children in active treatment (N = 24), 321 responses remained for analysis. Slightly more than half of respondents’ children were currently in surveillance or follow‐up care with their oncology team (54.5%), while 45.5% had completed all treatments and posttreatment surveillance and were no longer receiving cancer center‐based care (but could still be attending late‐effects clinics) (Table 1). Respondents were majority female (94.2%) and household incomes were broadly distributed, with 20% of families earning <$50,000 annually and 30% earning >$100,000 annually. The greatest proportion of primary cancer diagnoses were hematologic malignancies (49.5%). Half of respondents’ children received care exclusively at a standalone children's hospital (48%). Children were an average of 4.4 years old at diagnosis and 13.9 years old at time of survey.

TABLE 1.

Respondent characteristics of caregivers and their survivor of childhood cancer

| Number of respondents (n = 321) | Percentage of study population | |

|---|---|---|

| Respondent sex | ||

| Female | 302 | 94 |

| Male | 19 | 5.9 |

| Child treatment status | ||

| Surveillance/follow‐up care only | 175 | 55 |

| All treatment/surveillance completed | 146 | 45 |

| Exclusively treated at freestanding children's hospital | 154 | 48 |

| Mean (SD) child age at diagnosis | 4.40 (4.43) | – |

| Mean (SD) child age at survey completion | 13.73 (6.51) | – |

| Mean (SD) years diagnosis to survey | 9.53 (5.99) | – |

| Child cancer type | ||

| Hematologic | 159 | 50 |

| CNS | 45 | 14 |

| Other solid tumor | 117 | 36 |

| Annual household income ($) | ||

| <$20,000 | 12 | 3.7 |

| $20,000–49,999 | 53 | 16 |

| $50,000–74,999 | 71 | 22 |

| $75,000–99,999 | 76 | 24 |

| $100,000–149,999 | 52 | 16 |

| $150,000+ | 43 | 13 |

| Prefer not to say | 13 | 4.0 |

| Missing | 1 | <1.0 |

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

3.2. Information sources for COVID‐19

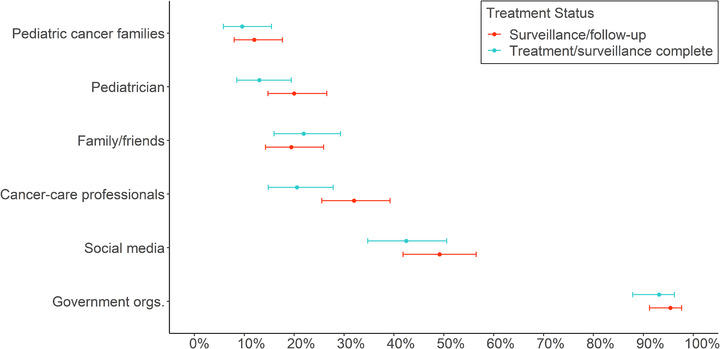

The most common sources from which caregivers were obtaining information on the COVID‐19 outbreak included government organizations (94%), social media (46%), cancer care professionals (27%, including: hospital's resource center, child's oncologist, child life specialist, or case worker), family or friends (21%), pediatricians (17%), and other parents of children with cancer (11%) (Figure 1). Proportions were similar for families with children in surveillance/follow‐up care as for families that had completed posttreatment surveillance, although the former were likelier to get information from cancer care professionals and pediatricians.

FIGURE 1.

Primary sources of information on COVID‐19 selected by caregivers of childhood cancer survivors, by child's treatment status (N = 321). The information source “cancer care professionals” includes the child's oncologist, hospital's resource center, Child Life Specialists, and oncology case workers. The abbreviation “Government orgs.” indicates “government organizations”

3.3. Impact on medical care

The COVID‐19 outbreak impacted the medical care of CCS, with 50% of caregivers reporting delayed/canceled appointments, 19% reporting delayed/canceled imaging, 26% converting to telehealth visits, and 9% reporting logistical challenges traveling to appointments (Figure S1). When asked how respondents anticipated the COVID‐19 outbreak would impact their child's medical care, these proportions rose; 68% expected appointments would be delayed/canceled, 30% expected delayed/canceled imaging, 37% expected to convert to telemedicine, and 14% expected logistical challenges while traveling to appointments (Figure S1).

3.4. Behavioral modifications due to COVID‐19

Caregivers reported taking steps to protect their families from infection, including additional handwashing (95%), self‐isolating (92%), frequently disinfecting surfaces (86%), avoiding sick people (84%), keeping other children in the household home from school (79%), and working from home (69%) (Figure S2). We did not ask about use of masks or face coverings because this was uncommon behavior at the time our survey was distributed and ran counter to the CDC's recommendations at that time (https://archive.is/o3oJp). However, several respondents reported using face coverings when leaving the home and experiencing difficulty obtaining N95 masks.

3.5. Financial impact of COVID‐19

Twenty‐eight percent of respondents reported an adult in the household had lost wages, 16% reported an adult had been laid off from work, and 7% reported an adult had become unemployed due to COVID‐19. The effects of lost income were variable, with 11% struggling to pay for basic needs and 5% struggling to pay for their child's medical care. Four families (1%) reported having lost health insurance (Figure S3).

3.6. Psychosocial effects of COVID‐19

Ordered logistic regression was used to evaluate a number of factors potentially associated with COVID‐related caregiver psychosocial measures. The distribution of caregiver responses for Likert‐type items used as either independent predictor variables or outcome variables are displayed in Table 2 and results of regression modeling in Table 3. Overall, 91% of caregivers expressed confidence in how hospitals and physicians’ offices were handling the COVID‐19 response and 48% expressed confidence in how the government was handling the COVID‐19 response.

TABLE 2.

Distributions of caregiver respondents’ answers for Likert‐type items

| Number of respondents (n = 321) | Percentage of study population | |

|---|---|---|

| Confidence in government response | ||

| Strongly disagree | 85 | 26 |

| Somewhat disagree | 83 | 26 |

| Somewhat agree | 126 | 39 |

| Strongly agree | 27 | 8.4 |

| Confidence in hospital/doctor's office response | ||

| Strongly disagree | 9 | 2.8 |

| Somewhat disagree | 20 | 6.2 |

| Somewhat agree | 126 | 39 |

| Strongly agree | 166 | 52 |

| Hopeful virus will resolve w/good future outlook | ||

| Strongly disagree | 4 | 1.3 |

| Somewhat disagree | 41 | 13 |

| Somewhat agree | 155 | 48 |

| Strongly agree | 121 | 38 |

| Feel more anxious than before outbreak | ||

| Strongly disagree | 30 | 9.4 |

| Somewhat disagree | 45 | 14 |

| Somewhat agree | 135 | 42 |

| Strongly agree | 111 | 35 |

| Feel more sad/depressed than before outbreak | ||

| Strongly disagree | 55 | 17 |

| Somewhat disagree | 62 | 19 |

| Somewhat agree | 140 | 44 |

| Strongly agree | 64 | 20 |

| Sleep about as well now as before outbreak | ||

| Strongly disagree | 65 | 20 |

| Somewhat disagree | 97 | 30 |

| Somewhat agree | 92 | 29 |

| Strongly agree | 67 | 21 |

| Less access to social support than before outbreak | ||

| Strongly disagree | 36 | 11 |

| Somewhat disagree | 30 | 9.4 |

| Somewhat agree | 115 | 36 |

| Strongly agree | 140 | 44 |

| Mean level of personal disruption (SD) | 7.46 (1.50) | – |

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

TABLE 3.

Relationships between covariates and COVID‐19‐related changes in psychosocial measures among caregivers from multivariable regression models (OR, 95% CI)

| Disruptive | Depressed | Anxious | Sleeping well | Less social support | Hope | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respondent gender | ||||||

| Female | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| Male | 0.65 | 0.42 * | 0.37 * | 2.09 | 1.57 | 1.52 |

| (0.23, 1.50) | (0.18, 0.99) | (0.15, 0.88) | (0.90, 4.88) | (0.61, 4.06) | (0.55, 4.19) | |

| Child cancer type | ||||||

| CNS | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| Hematologic | 1.40 | 0.66 | 0.75 | 1.16 | 1.70 | 0.85 |

| (0.74, 2.57) | (0.34, 1.27) | (0.39, 1.44) | (0.63, 2.16) | (0.91, 3.14) | (0.43, 1.67) | |

| Other solid tumor | 1.52 | 0.78 | 0.70 | 1.12 | 2.02 * | 0.90 |

| (0.79, 2.93) | (0.39, 1.55) | (0.36, 1.39) | (0.58, 2.14) | (1.05, 3.91) | (0.45, 1.83) | |

| Child treatment status | ||||||

| All surveillance/follow‐up complete | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| Surveillance/follow‐up | 1.07 | 1.32 | 1.11 | 0.96 | 1.14 | 0.91 |

| (0.68, 1.64) | (0.85, 2.05) | (0.71, 1.72) | (0.62, 1.47) | (0.73, 1.79) | (0.57, 1.46) | |

| Change to telemedicine visits | 1.07 | 1.26 | 1.14 | 1.19 | 1.49 | 0.71 |

| (0.63, 1.81) | (0.74, 2.15) | (0.67, 1.39) | (0.71, 2.01) | (0.95, 2.63) | (0.41, 1.24) | |

| Self‐isolating | 1.09 | 2.12 | 3.22 * | 0.36 * | 0.74 | 0.52 |

| (0.52, 2.28) | (0.99, 4.53) | (1.49, 6.96) | (0.16, 0.80) | (0.34, 1.62) | (0.21, 1.26) | |

| Information source | ||||||

| Government | 1.73 | 1.06 | 0.65 | 1.07 | 1.28 | 0.76 |

| (0.73, 4.06) | (0.41, 2.70) | (0.25, 1.69) | (0.43, 2.67) | (0.48, 3.38) | (0.28, 2.03) | |

| Social media | 1.44 | 1.45 | 1.36 | 1.06 | 1.59 * | 1.33 |

| (0.92, 2.25) | (0.92, 2.78) | (0.86, 2.14) | (0.68, 1.64) | (1.01, 1.62) | (0.82, 2.15) | |

| Cancer care professionals | 0.58 * | 1.23 | 1.61 | 1.22 | 0.51 * | 1.08 |

| (0.36, 0.95) | (0.75, 2.02) | (0.97, 2.68) | (0.75, 1.98) | (0.31, 0.83) | (0.64, 1.83) | |

| Pediatrician | 1.21 | 0.84 | 0.71 | 0.82 | 1.29 | 1.06 |

| (0.68, 2.18) | (0.48, 1.48) | (0.39, 1.28) | (0.47, 1.44) | (0.72, 2.33) | (0.57, 1.97) | |

| Family/friends | 0.70 | 1.03 | 1.24 | 1.15 | 0.89 | 1.38 |

| (0.41, 1.18) | (0.59, 1.78) | (0.71, 2.18) | (0.67, 1.96) | (0.51, 1.56) | (0.76, 2.52) | |

| Other parents of children w/cancer | 1.80 | 1.00 | 1.34 | 0.34 * | 1.28 | 0.90 |

| (0.89, 3.62) | (0.50, 1.97) | (0.66, 2.72) | (0.14, 0.61) | (0.62, 2.65) | (0.43, 1.86) | |

| Struggling to pay for basic needs | 2.49 * | 1.57 | 2.50 * | 0.29 * | 2.41 * | 0.50 |

| (1.27, 4.91) | (0.77, 3.21) | (1.19, 5.23) | (0.14, 0.61) | (1.16, 5.03) | (0.24, 1.02) | |

| Confidence in response | ||||||

| Government | 0.56 ** | 0.61 ** | 0.63 ** | 1.58 ** | 0.85 | 2.30 ** |

| (0.44, 0.70) | (0.48, 0.77) | (0.50, 0.79) | (1.27, 1.98) | (0.68, 1.08) | (1.77, 2.98) | |

| Hospital/doctor's offices | 1.17 | 0.98 | 1.19 | 1.10 | 0.85 | 1.59 * |

| (0.87, 1.56) | (0.73, 1.32) | (0.88, 1.61) | (0.63, 1.43) | (0.63, 1.15) | (1.15, 2.19) | |

| Freestanding children's hospital | 1.45 | 0.75 | 0.68 | 0.95 | 1.06 | 0.89 |

| (0.96, 2.18) | (0.49, 1.14) | (0.44, 1.04) | (0.63, 1.43) | (0.70, 1.62) | (0.57, 1.39) |

Note. Bold values indicate significance at α = .05.

*p < .05.

**p < 5.56 × 10–4, representing a Bonferroni correction for 90 total tests.

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

The mean value of “disruption to daily life” was 7.5 (SD = 1.5; range 1–9) on a 1–9 scale, with a mode of 9 (N = 98). Struggling to pay for basic needs was associated with greater disruption to daily life (p = .0082), while obtaining information on COVID‐19 from cancer care professionals (p = .030) and expressing confidence in the government response to COVID‐19 (p = 5.6 × 10–7) were associated with reporting less disruption to daily life.

A majority of respondents (64%) reported feeling more sad or depressed than before the COVID‐19 outbreak. Men (p = .046) and those expressing confidence in the government response to COVID‐19 (p = 3.7 × 10–5) reported less sadness/depression.

Most caregivers (77%) reported increased feelings of anxiety due to the outbreak. Factors associated with increased feelings of anxiety were greater self‐isolation (p = .0030) and struggling to pay for basic needs (p = .015), while male sex (p = .026) and expressing confidence in the government response to COVID‐19 (p = 8.3 × 10–5) were associated with decreased anxiety. Obtaining care exclusively at a freestanding children's hospital was also associated with decreased anxiety, although this did not reach statistical significance (p = .077).

Half of the respondents reported sleeping about as well as before the outbreak. Factors associated with sleep disruptions included struggling to pay for basic needs (p = .0095), self‐isolating (p = .012), and obtaining COVID‐19 information from other parents of children with cancer (p = .0020). The only factor associated with unaltered sleep quality was expressing confidence in the government response to COVID‐19 (p = 5.3 × 10–5).

A majority of respondents (79%) reported diminished access to social support during the outbreak. Struggling to pay for basic needs (p = .019), obtaining COVID‐19 information from social media (p = .046), and having a child with a non‐CNS solid tumor (p = .036) were associated with reduced access to social support, while those obtaining COVID‐19 information from cancer care professionals reported similar access to social support as before the outbreak (p = .0072).

Finally, most respondents (86%) agreed that they were “hopeful that the COVID‐19 virus will resolve over time” and “have a good outlook toward the future.” Factors significantly associated with increased hopefulness were greater confidence in how hospital and physicians’ offices are handling the COVID‐19 response (p = .0045) and greater confidence in the government response to COVID‐19 (p = 2.9 × 10–10), with confidence in government having a nearly two‐fold larger magnitude of effect than confidence in the medical community.

3.7. Qualitative analysis of free‐text responses

Four primary themes emerged from qualitative analysis of free‐text responses, including lack of information, interruptions to care, educational disruptions, and similarities between parenting a child with cancer and parenting during COVID‐19 (Table S1 and Table 4, including supportive quotes). Lack of COVID‐19 information tailored to CCS was a recurrent theme in free‐text responses and a source of caregiver frustration; for example, “There is absolutely NO INFORMATION with respect to childhood cancer survivors and their risks with respect to COVID‐19.” Several caregivers expressed concern over delays in care in free‐text responses, for example, “I'm mad that our children's hospital refuses to schedule his routine echocardiogram right now.” Educational disruptions were also a frequent cause of concern, and were particularly acute in caregivers of children with special learning needs, for example, “[My son] is doing work at home but the IEP cannot be followed during distance learning” and “My child is 6 years off treatment but also has Down syndrome. During treatment it was a fight to get him to go back to school and I know that will happen when this is over.” Free‐text responses also indicated that caregivers perceived similarities between parenting a child with cancer and parenting during COVID‐19 as it related to infection precautions. As one respondent succinctly put it, “The general population is doing what cancer families have been doing since diagnosis.”

TABLE 4.

Free‐text response themes with sample corresponding quotes

| Themes and quotes | |

|---|---|

| Similarities between parenting a child with cancer and parenting during COVID‐19 | |

| As a cancer family, I feel it's a little easier to deal with the restrictions from the virus because we have had to make restrictions before in order to keep safe. | |

| Because of treatment, I know what to do (following neutropenic guidelines). But, the hermit life is not sustainable. | |

| Since we've been in quarantine before due to her transplant, it doesn't faze us as much. We were well prepared with cleaning supplies and plenty of hand sanitizer due to her health needs. | |

| Having a cancer kid has prepared us better since during treatment, we did the isolation, sanitizing, limiting exposure routine. It is strange to have to go back to it, but necessary. | |

| I find having other people being more careful has helped my daughter. Our family has been super careful for years. | |

| I think having a child with cancer and already being on high alert regarding germs, hand washing, sanitizing, being cautious of being around others who are sick or don't feel well, etc. have prepared our family for trying to keep well during this pandemic. | |

| It makes us feel like we are back in active treatment and we have to make sure no one is sick that comes around at all because of the risks of my son's lowered immune system. | |

| The general population is doing what cancer families have been doing since diagnosis. | |

| The isolation is very much the same as what we lived during treatment. | |

| The isolation we are experiencing has been easier to endure because we already know how to make “living in the bubble” work for our family. That said, this experience is bringing back some very hard memories for our family. | |

| We actually feel that our daughter's experience with cancer has helped her prepare for social distancing. There were many times during her treatment where she had to be isolated at home due to a weakened immune system. Even though it has been a few years, she has adjusted very well to being at home during this time (more so than some of her peers). | |

| We are a posttransplant family and have practiced many of the social distancing and health‐related measures already, but it definitely has affected my husband and daughter who lived a “somewhat” normal life prior to COVID. I am basically continuing what I've always done. | |

| Working through chemo, toxic diapers from radiation and central line care has prepared us well for pandemic living. It really isn't that different for us. We were already really stocked up. |

Note. Included here are those relating to similarities between parenting a child with cancer and parenting during COVID‐19. Quotes corresponding to lack of information, interruption to care, and educational disruptions appear in Table S1.

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

4. DISCUSSION

The COVID‐19 pandemic is a dynamic situation subject to change as new information arises. Both medical professionals and patients have adapted to it in various ways, including transitioning to telehealth visits and altering follow‐up schedules. These disruptions, though necessary, may compound the existing distress of caregivers of CCS. Such stressors may further interfere with coping strategies and reduce caregiver emotional resilience, with potentially negative impacts on the physical and emotional well‐being of the child and their family. To assess the impact of COVID‐19, we deployed a rapid survey to caregivers of CCS between April 13 and May 17, 2020. We observed a broad impact of COVID‐19 on the psychosocial well‐being of caregivers. This impact was modified by financial distress, social isolating behaviors, primary sources of information on the pandemic, and confidence in the government and medical community's responses to COVID‐19.

Childhood cancer families obtained COVID‐19 information from a variety of sources, primarily government organizations, social media, and cancer care professionals. Although not all families had interacted with a medical professional during the pandemic, the high utilization of social media for information gathering suggests there may be opportunities to engage and effectively communicate with these families online between visits. Caregivers expressed frustration about a perceived lack of available information about the effects of COVID‐19 on CCS. Such data are beginning to emerge, 17 , 18 , 19 , 44 and effectively communicating these results to caregivers should be prioritized.

Respondents were generally proactive in protecting their families from infection, with 91% self‐isolating and 69% working from home. Free responses highlighted that this relatively high uptake of prophylactic measures was not a major departure from actions families had previously taken to protect their CCS, with sanitization procedures and persistent social isolation emphasized. Indeed, caregivers emphasized many similarities between managing infection risks during their child's treatment and during the COVID‐19 pandemic. While some caregivers expressed that these similarities evoked difficult memories, the majority expressed tremendous resilience due to their previously acquired proficiency with managing infection risks.

More than one‐fourth of respondents reported that an adult in the household had lost wages as a result of COVID‐19 and 11% were struggling to pay for basic needs. These respondents reported greater disruption to daily life, greater feelings of anxiety, poorer sleep, and less access to social support. Costs of daily living are important drivers of financial toxicity for families of children with cancer, 45 , 46 , 47 and financial assistance programs may need to engage with families that have completed treatment but who may continue to struggle with cancer‐related financial toxicity.

Respondents who expressed confidence in the government response to COVID‐19 reported significantly less disruption to their daily life, decreased feelings of depression and anxiety, better sleep, and higher levels of hopefulness. It is important to note that while respondents who endorsed low confidence in the government response may be at increased risk of poorer psychosocial outcomes, other variables, like high baseline anxiety, may mediate or moderate this relationship. Though baseline data for caregiver anxiety and depressive symptoms were not available, this underscores the importance of routine needs assessments for the CCS and caregiver populations throughout the pediatric cancer journey so that opportunities for prevention and intervention may be identified expediently—in line with evidence‐based standards of care. 48 , 49 While confidence in hospitals and physicians was also associated with caregiver hopefulness, the magnitude of effect was substantially smaller than that of confidence in government. Because these families are heavily engaged with the medical community, our results highlight not only the important role that health care teams can play in educating families and addressing concerns, but also that these impacts appear secondary to those of government agencies. Although our survey did not distinguish the level of government (i.e., local, state, federal), free‐text responses indicate respondents were primarily focused on pandemic response at the federal level, which seems reasonable in the context of a global pandemic.

Our study has several limitations. While the ALSF MCC cohort is representative of the US population in terms of family income distribution, it is composed primarily of female, non‐Hispanic White participants. Moving forward, it will be important to understand how caregivers of CCS from other backgrounds may be differentially impacted by COVID‐19. Also, while our survey questions about social distancing and disinfecting surfaces reflected public health consensus at the time the survey was issued, we did not ask about the use of masks or face coverings. At the time the survey was sent, mask use was uncommon behavior and the CDC explicitly recommended that only those who were caring for the ill should wear masks to maintain a supply reserve (https://archive.is/o3oJp). Finally, the questions in our survey evaluating COVID‐specific psychosocial outcomes were adapted from an ongoing longitudinal study, but were not rigorously externally validated due to time constraints given the emergent nature of this pandemic.

Qualitative analysis of free‐text responses highlighted caregiver concerns around lack of information, interruptions to care, educational disruptions, and similarities between parenting a child with cancer and parenting during COVID‐19. Both regression analyses and qualitative analyses underscored the immense impact of COVID‐19 on the psychosocial well‐being of caregivers. This has clear relevance for the medical community as it cares for families negotiating the pandemic and potentially encountering increasing infection rates in their local communities. The negative financial and psychosocial impacts on caregivers of CCS should spur clinicians to conduct ongoing assessment of distress during the pandemic. Given the added stress of parenting a CCS during COVID‐19, clinical staff should prioritize screening caregivers for emotional distress and financial toxicity, and should ensure availability of social workers when appropriate. Additionally, as follow‐up visits are increasingly converted to telehealth appointments that may be less amenable to identifying caregiver distress, we encourage pediatric oncology teams to creatively integrate psychosocial team members into telehealth encounters and to be attentive to these issues when interacting with caregivers of CCS.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Supporting Information

SUPPLEMENTAL TABLE S1 Free‐text response themes with sample corresponding quotes

FIGURE S1 Proportions of MCC families reporting actual versus anticipated effect of COVID‐19 on child's health care

FIGURE S2 Proportions of MCC families reporting actions taken to reduce SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, by child's treatment status

FIGURE S3 Proportions of MCC families reporting COVID‐19′s impact on economic and lifestyle factors, by child's treatment status

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Alex's Lemonade Stand Foundation (Courtney E. Wimberly, Lisa Towry, Emily E. Johnston, Kyle M. Walsh), the National Institutes of Health R21CA242439‐01 (Kyle M. Walsh), and the Children's Health and Discovery Initiative of Translating Duke Health (Kyle M. Walsh).

Wimberly CE, Towry L, Caudill C, Johnston EE, Walsh KM. Impacts of COVID‐19 on caregivers of childhood cancer survivors. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2021;68:e28943. 10.1002/pbc.28943

Funding information

Alex's Lemonade Stand Foundation; National Institutes of Health, Grant Number: R21CA242439‐01; Children's Health and Discovery Initiative of Translating Duke Health

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

De‐identified, individual‐level data are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Lai C‐C, Wang C‐Y, Wang Y‐H, et al. Global epidemiology of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19): disease incidence, daily cumulative index, mortality, and their association with country healthcare resources and economic status. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020;55:105946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Guan W, Liang W, Zhao Y, et al. Comorbidity and its impact on 1590 patients with COVID‐19 in China: a nationwide analysis. Eur Respir J. 2020;55:2000547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Simonnet A, Chetboun M, Poissy J, et al. High prevalence of obesity in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus‐2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) requiring invasive mechanical ventilation. Obesity. 2020;28:1195–1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zhang J, Wang X, Jia X, et al. Risk factors for disease severity, unimprovement, and mortality in COVID‐19 patients in Wuhan, China. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26:767–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID‐19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dai M, Liu D, Liu M, et al. Patients with cancer appear more vulnerable to SARS‐CoV‐2: a multicenter study during the COVID‐19 outbreak. Cancer Discov. 2020;10:783–791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Liang W, Guan W, Chen R, et al. Cancer patients in SARS‐CoV‐2 infection: a nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:335–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yu J, Ouyang W, Chua ML, Xie C. SARS‐CoV‐2 transmission in cancer patients of a tertiary hospital in Wuhan. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6(7):1108‐1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhang L, Zhu F, Xie L, et al. Clinical characteristics of COVID‐19‐infected cancer patients: a retrospective case study in three hospitals within Wuhan, China. Ann Oncol. 2020;31:894–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zheng Z, Peng F, Xu B, et al. Risk factors of critical & mortal COVID‐19 cases: a systematic literature review and meta‐analysis. J Infect. 2020;81:e16–e25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Robilotti EV, Babady NE, Mead PA, et al. Determinants of COVID‐19 disease severity in patients with cancer. Nat Med. 2020;26:1218–1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lee LYW, Cazier J‐B, Starkey T, et al. COVID‐19 prevalence and mortality in patients with cancer and the effect of primary tumour subtype and patient demographics: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:1309–1316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Susek KH, Gran C, Ljunggren H‐G, et al. Outcome of COVID‐19 in multiple myeloma patients in relation to treatment. Eur J Haematol. 2020;105:751–754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hultcrantz M, Richter J, Rosenbaum C, et al. COVID‐19 infections and outcomes in patients with multiple myeloma in New York City: a cohort study from five academic centers. medRxiv. 2020. 10.1101/2020.06.09.20126516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lièvre A, Turpin A, Ray‐Coquard I, et al. Risk factors for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) severity and mortality among solid cancer patients and impact of the disease on anticancer treatment: a French nationwide cohort study (GCO‐002 CACOVID‐19). Eur J Cancer. 2020;141:62–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. de Joode K, Dumoulin DW, Tol J, et al. Dutch oncology COVID‐19 consortium: outcome of COVID‐19 in patients with cancer in a nationwide cohort study. Eur J Cancer. 2020;141:171–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Boulad F, Kamboj M, Bouvier N, et al. COVID‐19 in children with cancer in New York City. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6(9):1459–1460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ferrari A, Zecca M, Rizzari C, et al. Children with cancer in the time of COVID‐19: An 8‐week report from the six pediatric onco‐hematology centers in Lombardia, Italy. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2020;67(8):e28410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hamdy R, El‐Mahallawy H, Ebeid E. COVID‐19 infection in febrile neutropenic pediatric hematology oncology patients. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2021;68(2):e28765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jammu AS, Chasen MR, Lofters AK, Bhargava R. Systematic rapid living review of the impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on cancer survivors: update to August 27, 2020. Support Care Cancer. 2020. 10.1007/s00520-020-05908-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ng D, Chan F, Barry T, et al. Psychological distress during the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID‐19) pandemic among cancer survivors and healthy controls. Psychooncology. 2020;29(9):1380–1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Han J, Zhou F, Zhang L, et al. Psychological symptoms of cancer survivors during the COVID‐19 outbreak: a longitudinal study. Psychooncology. 2020. 10.1002/pon.5588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Papautsky EL, Hamlish T. Emotional response of US breast cancer survivors during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Cancer Invest. 2021;39(1):3–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chao C, Bhatia S, Xu L, et al. Chronic comorbidities among survivors of adolescent and young adult cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:3161–3174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bhakta N, Liu Q, Ness KK, et al. The cumulative burden of surviving childhood cancer: an initial report from the St Jude Lifetime Cohort Study (SJLIFE). Lancet. 2017;390:2569–2582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Feijen EAML, Font‐Gonzalez A, Van der Pal HJH, et al. Risk and temporal changes of heart failure among 5‐year childhood cancer survivors: a DCOG‐LATER study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:09122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Meacham LR, Chow EJ, Ness KK, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors in adult survivors of pediatric cancer–a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:170–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Huang TT, Chen Y, Dietz AC, et al. Pulmonary outcomes in survivors of childhood central nervous system malignancies: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61:319–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kurt BA, Nolan VG, Ness KK, et al. Hospitalization rates among survivors of childhood cancer in the childhood cancer survivor study cohort. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;59:126–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lorenzi MF, Xie L, Rogers PC, et al. Hospital‐related morbidity among childhood cancer survivors in British Columbia, Canada: report of the childhood, adolescent, young adult cancer survivors (CAYACS) program. Int J Cancer. 2011;128:1624–1631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kurlander L, Antal Z, DeRosa A, et al. COVID‐19 in pediatric survivors of childhood cancer and hematopoietic cell transplantation from a single center in New York City. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2021;68(3):e28857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Verbruggen LC, Wang Y, Armenian SH, et al. Guidance regarding COVID‐19 for survivors of childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancer: a statement from the International Late Effects of Childhood Cancer Guideline Harmonization Group. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2020;67:e28702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Forster VJ, Schulte F. Unique needs of childhood cancer survivors during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29(1):17–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. International Guideline Harmonization Group . IGHG COVID‐19 Statement. 2020. https://www.ighg.org/ighg-statement-covid-19/. Accessed December 3, 2020.

- 35. Children's Oncology Group . Long‐Term Follow‐Up Guidelines for Survivors of Childhood, Adolescent, and Young Adult Cancers. Version 5.0 (October 2018). http://www.survivorshipguidelines.org/. Accessed December 3, 2020.

- 36. Children's Cancer and Leukaemia Group . Coronavirus Advice for Long Term Survivors. https://www.cclg.org.uk/coronavirus-advice/survivors. Accessed December 3, 2020.

- 37. Chiaravalli S, Ferrari A, Sironi G, et al. A collateral effect of the COVID‐19 pandemic: delayed diagnosis in pediatric solid tumors. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2020;67(10):e28702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yan AP, Chen Y, Henderson TO, et al. Adherence to surveillance for second malignant neoplasms and cardiac dysfunction in childhood cancer survivors: a Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:1711–1722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. McLoone J, Wakefield CE, Taylor N, et al. The COVID‐19 pandemic: distance‐delivered care for childhood cancer survivors. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2020;67(12):e28715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Guido A, Marconi E, Peruzzi L, et al. Psychological impact of COVID‐19 on parents of pediatric cancer patients. Authorea. 10.22541/au.160645871.12621982/v1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lansford JE, Al‐Hassan SM, Bacchini D, et al. Parenting and positive adjustment for adolescents in nine countries. In: Well‐Being of Youth and Emerging Adults across Cultures. 2017:235–248. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Macqueen KM, Mclellan E, Kay K, et al. Codebook development for team‐based qualitative analysis. Cult Anthropol Methods. 1998;10:31–36. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Malterud K. Qualitative research: standards, challenges, and guidelines. Lancet. 2001;358:483–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lipshultz SE, Lipsitz SR, Sallan SE, et al. Chronic progressive cardiac dysfunction years after doxorubicin therapy for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2629–2636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bona K, London WB, Guo D, et al. Trajectory of material hardship and income poverty in families of children undergoing chemotherapy: a prospective cohort study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;63:105–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bona K, Blonquist TM, Neuberg DS, et al. Impact of socioeconomic status on timing of relapse and overall survival for children treated on Dana‐Farber Cancer Institute ALL Consortium Protocols (2000–2010). Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;63:1012–1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Pelletier W, Bona K. Assessment of financial burden as a standard of care in pediatric oncology: assessment of financial burden in pediatric oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62:S619–S631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lown EA, Phillips F, Schwartz LA, et al. Psychosocial follow‐up in survivorship as a standard of care in pediatric oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62:S514–S584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wiener L, Kazak AE, Noll RB, et al. Standards for the psychosocial care of children with cancer and their families: an introduction to the special issue. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62:S419–S424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information

SUPPLEMENTAL TABLE S1 Free‐text response themes with sample corresponding quotes

FIGURE S1 Proportions of MCC families reporting actual versus anticipated effect of COVID‐19 on child's health care

FIGURE S2 Proportions of MCC families reporting actions taken to reduce SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, by child's treatment status

FIGURE S3 Proportions of MCC families reporting COVID‐19′s impact on economic and lifestyle factors, by child's treatment status

Data Availability Statement

De‐identified, individual‐level data are available from the authors upon reasonable request.