Abstract

During COVID‐19 lockdown, individuals were asked to leave their home only to meet the most urgent needs, such as grocery purchases and medical emergencies. This study aimed to know the consumers' health safety practices and their concerns toward grocery shopping and to know their adoption of healthier food as a result of the outbreak. An online survey was conducted during the second month of the COVID‐19 lockdown. This study includes 212 respondents. Appropriate statistical tools were used to analyze the data. The findings of the study revealed that females were ahead compared to males in pursuing health safety practices during grocery shopping, but the frequency of following physical distancing for both males and females was not up to the mark. The most important concern about grocery shopping was fear of unavailability of stocks and fear of getting infected from grocery storekeepers. It was also found that, compared to earlier, people had reduced their frequency of grocery shopping and tried to shop quickly and efficiently. People bought more packaged foods and also made purchases from brands that were new to them. As a result of the COVID‐19 pandemic, the adoption of healthier food habits varied significantly with gender, age, and household income of the respondents. This study indicates that there is a need to raise awareness among people on how to shop safely in grocery stores and that good hygiene practice should be followed in grocery stores to mitigate the risk of infection to consumers.

Keywords: consumer behavior, Coronavirus, COVID‐19 lockdown, grocery shopping, healthy eating

1. INTRODUCTION

The COVID‐19 pandemic is an unprecedented event in the past 100 years of human history. COVID‐19 is an extremely infectious virus for which no proven and known vaccine yet exists. This virus has caused a disruption that has led to shuttering of economic and business activity on a scale that is almost unparalleled. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, 2020a) stated that COVID‐19 appears to be disseminating primarily from individual to individual, readily and easily, resulting in the respiratory disease, and deaths of elderly adults and individuals of any age who have severe underlying medical conditions (Jribi et al., 2020). The first case of COVID‐19 was reported in Wuhan, China in December 2019, since then COVID‐19 has been spreading exponentially around the globe, leading to an epidemic impacting 210 countries. In less than 6 months, World Health Organization (WHO, 2020a) reported over more than 600,000 deaths across the world. In India, the first COVID‐19 case was confirmed on January 30, 2020 in the state of Kerala, when a Wuhan University student travelled back to the state (Ward, 2020). By March 24, 2020, as the number of positive cases grew, the Indian government had issued complete lockdown orders in the entire country to contain the spread of the coronavirus. In India, the nationwide lockdown was implemented in four phases and lasted till 31 May. This shutdown was the biggest in the world, forcing 1.3 billion people to remain at home (Statista, 2020). Due to the lack of effective vaccines or treatments for COVID‐19, several countries, such as India, have preferred a shutdown approach to contain the transmission of the novel coronavirus and protect their people. This strategy intends to break the chain of coronavirus, reduce the number of cases to a low level by social distancing the entire nation, and stopping all unessential economic and business activities including shutting schools and universities, To handle the COVID‐19 effectively and to manage the burden on healthcare services, Ferguson et al., 2020 proposes that lockdowns will need to be carried out on a fairly regular basis for more than a year. Throughout lockdown, individuals are appealed to remain at home and leave only to meet the most urgent needs like food purchasing and in case of medical emergencies. In many countries like India, the lockdown allowed free movement of “essential” commodities and was supposed to allow food markets to function without impediments (Rawal & Kumar, 2020). In many countries, government declarations of shutdown have led to a panic buying of food items (Jribi et al., 2020). Wang et al., 2020 stated psychological effects, fear, anxiety, and stress among Chinese participants during the preliminary phases of the epidemic of COVID‐19. The COVID‐19 shutdown has triggered significant changes in the approach of individuals' everyday lives in several countries across the globe including the ways people buy food (Martin‐Neuninger & Ruby, 2020). A consumer adopts the habits over time about what to consume, when and where (Sheth, 2020). Apparently, this is not limited to consumption; it is also true of purchasing and searching for information (Jribi et al., 2020). In this lockdown, customers are getting almost all of their food from grocery shops, as online delivery services were not permitted in many regions of the country and many grocery shops have altered their hours of operation in accordance with the lockdown rules (Food and Drug Administration (FDA), 2020a, 2020b).

At the time of study period, there is absolutely no proof that the novel coronavirus can be transmitted by interaction with food or food packaging (CDC, 2020b). As of 17 April, World health organization report, there was not any reported case of COVID‐19 transmitted via food or food packaging. However, it is always vital to practice decent hygiene when handling food in order to avoid any food‐borne illness (UNICEF, 2020). As food or grocery shopping remains a necessity during this pandemic, many people have concerns about how to shop safely (Food and Drug Administration (FDA), 2020a, 2020b). In response to the COVID‐19 outbreak, consumers are drastically changing their food buying habits (Kolodinsky et al., 2020; Schmidt et al., 2020; Worstell, 2020). Also, visiting a grocery store in person implies risk of becoming infected. Therefore, COVID‐19 caused a shift in people's life and shopping and eating habits (Criteo Coronavirus Survey 2020). Eating a healthy diet is always vital, but it is much more vital during this particular outbreak because a well‐balanced diet of healthy foods helps to maintain a strong immune system. Eating a healthy diet can significantly impact our body's ability to resist, conquer, and recuperate from infection (WHO, 2020b). WHO also suggested that good nutrition and hydration are important for adults in these pandemics times, while no food or nutritional supplements can protect or cure COVID‐19 infection, healthier diets are useful in helping immune systems. Individuals who eat well‐balanced diets appear to be safer with improved body's immune system and a reduced risk of chronic illnesses and contagious diseases. Food is the least of all the infectious agents. So, when it comes to the groceries, it is the shopping and washing practices that we really need to focus on these pandemic times (UNICEF, 2020). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, 2020b) report states that “because of poor surface survival of coronavirus, there is likely to be a very low risk of spread from food items or packaging that are delivered over days or weeks at normal, refrigerated, or frozen temperatures. Prior studies have revealed that consumers' buying behavior varies with time restraints (Iyer, 1989; Liu et al., 2017; Park et al., 1989); therefore, it is likely that consumers' buying behavior will change as a consequence of the ongoing COVID‐19 crisis. Although grocery shopping is a vital activity, not much is known about the relationship of the COVID‐19 epidemic to the behavior of grocery shoppers. Therefore, it would be imperative to know the relationship between the traumatic event (COVID‐19 pandemic) and changes in grocery shopping behavior, and the adoption of eating healthy habits during this pandemic. During the period of data collection, the movement of individuals was restricted, and individuals were only to leave home if they work in essential services or if they had to purchase essential goods (groceries or medicines) within their cities. The present study mainly focuses on knowing consumers' health safety practices and their concerns while they go for grocery shopping, whether they have adopted healthy eating habits since the pandemic began, and to know whether this COVID‐19 lockdown has changed their grocery shopping behavior.

2. METHODOLOGY

It was a cross‐sectional analysis conducted in India. An online standardized questionnaire was created using Google forms. The reliability of the questionnaire was tested through Cronbach's alpha for which the value came out as 0.84, which is greater than the cutoff value of 0.70 (Dillon et al., 1994; Santos, 1999), whereas the validity was checked through content validity by consulting with domain experts and academicians. The questionnaire was connected to the researcher's contacts using emails, WhatsApp, and other social media. Participants were urged to take the survey accessible to as many people as possible. It has been an online study. Participants with access to the Internet could take part in the survey. Participants over 18 years of age who were able to understand English were included in the study. The first part of the questionnaire sought information on demographic variables such as gender, age, educational qualifications, monthly household income, and the profession of respondents. The second part of the questionnaire had questions related to precautionary steps taken by customers to stay safe during grocery shopping. It also included questions requesting the consumer's answer to the concerns of shoppers during the time of the pandemic regarding grocery shopping. To know what concerns the consumer most about grocery shopping since COVID‐19 pandemic began, rank order scale was developed. The rank order scale consisted of five items. The respondents were asked to rank their concerns about grocery shopping. The third part of the questionnaire seeks information on consumer grocery shopping behavior and about adoption of healthier foods since the COVID‐19 pandemic began. The data analysis has been carried on using SPSS (Version 22) software tool. To assess the frequency of responses, descriptive statistics was used. Chi‐square test was used to understand the relationship between gender and their health safety practices. Mann–Whitney U test was used to establish if a significant difference existed between genders in their rankings of each considered concern about grocery shopping. Finally, the influence of demographic variables on the consumer adoption of healthier food was tested using logistic regression. For this purpose, each demographic characteristic has been partitioned into binary independent variable and consumers' response to the question on “whether COVID‐19 pandemic influenced you to adopt healthier food habits?” was used as a binary dependent variable.

3. FINDINGS

A total of 212 responses were collected and the same were analyzed. The key findings of the survey were as follows.

4. DEMOGRAPHIC PROFILE OF THE CONSUMERS

The demographic characteristics of the sample respondents are shown in Table 1. Out of 212 respondents, 66% were “male” and 34% were “female”. More than 90% of the respondents were below 50 years and most of them were graduates (34.4%) and postgraduates (26.4%) followed by doctorate (24.1%), secondary/intermediate (8.5%), and post‐doctorate (6.6%). More than 60% of the respondents were having monthly household income above INR 40,000 and most of the respondents were students (42%) and employed (24.5%) followed by homemaker (12.7%), business (11.8%), and retired/unemployed (9%).

TABLE 1.

Consumer demographics profiles

| Characteristics | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 140 | 66 |

| Female | 72 | 34 |

| Age group (years) | ||

| 18–29 | 97 | 45.8 |

| 30–39 | 74 | 34.9 |

| 40–49 | 28 | 13.2 |

| 50–59 | 6 | 2.8 |

| ≥60 | 7 | 3.3 |

| Education | ||

| Up to 12th | 18 | 8.5 |

| Graduate | 73 | 34.4 |

| Postgraduate | 56 | 26.4 |

| Doctorate | 51 | 24.1 |

| Postdoctorate | 14 | 6.6 |

| Monthly household income | ||

| Up to 20,000 | 22 | 10.4 |

| 20,000–40,000 | 55 | 25.9 |

| 40,000–60,000 | 54 | 25.5 |

| 60,000–75,000 | 61 | 28.8 |

| ≥75,000 | 20 | 9.4 |

| Profession | ||

| Student | 89 | 42 |

| Employed | 52 | 24.5 |

| Unemployed/retired | 19 | 9 |

| Business | 25 | 11.8 |

| Homemaker | 27 | 12.7 |

5. CONSUMER SAFETY PRACTICES TO STAY SAFE WHILE BUYING GROCERIES

Respondents were asked about the safety practices they are pursuing to stay safe and protect themselves from COVID‐19 while shopping for groceries in grocery stores (Table 2), it was measured through six items on a three‐point Likert scale (1 = never; 2 = sometimes; 3 = always).

TABLE 2.

Self‐reported survey results on the consumers' health safety practices while shopping for groceries

| Male | Female | Total | χ 2 | p value a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | N (%) | |||

| Washing or sanitizing hands after grocery shopping | |||||

| Always | 81 (57.9) | 55 (76.4) | 136 (64.2) | ||

| Sometimes | 43 (30.7) | 12 (16.7) | 55 (25.9) | 7.127 | .028 |

| Never | 16 (11.4) | 5 (6.9) | 21 (9.9) | ||

| Wearing mask at the grocery store | |||||

| Always | 90 (64.3) | 53 (73.6) | 143 (67.5) | ||

| Sometimes | 38 (27.1) | 13 (18.1) | 51 (24.1) | 2.248 | .325 |

| Never | 12 (8.6) | 6 (8.3) | 18 (8.5) | ||

| Clean the bought packaged goods after coming from grocery store | |||||

| Always | 47 (33.6) | 44 (61.1) | 91 (42.9) | ||

| Sometimes | 64 (45.7) | 20 (27.8) | 84 (39.6) | 14.774 | .001 |

| Never | 29 (20.7) | 8 (11.1) | 37 (17.5) | ||

| Maintain or follow physical distancing at grocery store | |||||

| Always | 41 (29.3) | 38 (52.8) | 79 (37.3) | 11.615 | .003 |

| Sometimes | 81 (57.9) | 26 (36.1) | 107 (50.5) | ||

| Never | 18 (12.9) | 8 (11.1) | 26 (12.3) | ||

| Avoid touching surfaces unnecessarily at grocery store | |||||

| Always | 27 (19.3) | 34 (47.2) | 61 (28.8) | ||

| Sometimes | 89 (63.6) | 27 (37.5) | 116 (54.7) | 18.903 | .000 |

| Never | 24 (17.1) | 11 (15.3) | 35 (16.5) | ||

| Changing clothes after coming from grocery shopping | |||||

| Always | 35 (25) | 24 (33.3) | 59 (27.8) | 6.851 | .033 |

| Sometimes | 67 (47.9) | 21 (29.2) | 88 (41.5) | ||

| Never | 38 (27.1) | 27 (37.5) | 65 (30.7) | ||

Chi‐square test for homogeneity of proportions between male and female.

Findings revealed that majority (64.2%) of the respondents ‘always’ wash or sanitize their hands after grocery shopping and among them majority (76.4%) were female consumers. While 25.9% of the respondents reported washing or sanitizing their hands “sometimes” and only 9.9% of the respondents stated they “never” wash or sanitize their hands after grocery shopping. A significant difference between male and female was found with the help of the chi‐square test (p = .028, p < .05) in terms of washing or sanitizing hands after grocery shopping. Regarding wearing a mask at the grocery store, more than half (67.5%) of the respondents affirmed they “always” wore a mask at the grocery store, while 24.1% of the respondents reported wearing a mask “sometimes” and 8.5% of the respondents said they “never” did so. Among respondents who “always” wore a mask at the grocery store, the majority of them (73.6%) were female respondents; however, no significant difference was found between male and female respondents regarding wearing a mask at the grocery store.

Furthermore, respondents were asked to answer whether they cleaned the bought packaged goods after coming home from the grocery store: 42.9% of the respondents affirmed they “always” cleaned the bought packaged goods, while 39.6% of the respondents reported cleaning the bought packaged goods “sometimes,” and 17.5% of the respondents stated they “never” cleaned the packaged goods, which they have bought from grocery stores. Among respondents who “always” cleaned the bought packaged goods, the majority of them were female respondents. Also, a significant difference of p = .001 (p < .05) was established between male and female consumers with respect to cleaning the bought packaged goods after coming home from grocery stores.

Regarding following physical distancing at the grocery store, only 37.3% of the respondents affirmed “always” following physical distancing, while just over half (50.4%) of the respondents stated they followed physical distancing “sometimes,” and 12.3% of the respondents reported they “never” followed physical distancing while buying groceries at the grocery store. Female consumers had a higher frequency in following physical distancing “always” at grocery store than that of male consumers, and significant difference of p = .003 (p < .05) was found between male and female respondents in following physical distancing during grocery shopping at grocery store.

Respondents were also asked to respond whether they avoid touching surfaces unnecessarily at the grocery store, the findings showed that only 28.8% of the respondents “always” avoided touching surfaces at grocery store, while 54.7% of the consumer stated avoided touching surfaces “sometimes,” and 16.5% of the respondents reported they “never” avoided touching surfaces at the grocery store. A significant difference (p < .05) was noticed between male and female consumers on avoiding touching surfaces unnecessarily in grocery stores. The findings also revealed that, compared to male consumers, female consumers were more likely to avoid touching surfaces unnecessarily.

Regarding changing clothes after coming home from the grocery store, only 27.8% of the respondents reported they “always” changed clothes and among them majority were female consumers. While 41.5% of respondents reported “sometimes” doing this, and 30.7% of respondents stated they “never” did so. A significant difference was found (p = .33, p < .05) between male and female with respect to changing clothes after coming home from grocery shopping.

6. CONSUMER CONCERNS ABOUT GROCERY SHOPPING

To the question “Since the COVID‐19 lockdown began, what concerns you the most about grocery shopping?” respondents were asked to assign to rank their concern. They were asked to assign rank 1 to the “most important concern” and rank 5 to the “least important concern.” Five concerns were considered for this purpose, which are as follows: Fear of nonavailability of grocery stocks, fear of getting infected from grocery storekeepers, fear of getting infected from other shoppers at the store, safety of the foods that I am purchasing, and nonavailability of fresh food products. The responses were analyzed by comparing mean score of male and female respondents. As ranked data are ordinal and nonparametric, Mann–Whitney U test was applied to know the relationship between male and female respondents and their grocery shopping concerns.

The analysis of mean scores (Table 3) indicates that most important concern for male respondents was “fear of nonavailability of grocery stocks” (2.05) and “fear of getting infected from grocery storekeepers” (2.25) followed by “fear of getting infected from other shoppers” (3.24). While for female respondents, the most important concern was “safety of foods that I am purchasing” (2.15) and “nonavailability of fresh food products” (2.87) followed by “fear of nonavailability of grocery stocks” (3.0). The least important concerns among male respondents were “safety of the foods that I am purchasing” (3.27) and “nonavailability of fresh food products” (4.16), while for female respondents “fear of getting infected from grocery storekeepers” (3.22) and “fear of getting infected from other shoppers” (3.72) were the least important concerns. With the help of Mann–Whitney U test, significant differences (p < .05) were established between male and female consumers in their rankings of each of the above‐considered concerns.

TABLE 3.

Consumer concerns about grocery shopping during COVID‐19 lockdown

| Male | Female | Total | Mann–Whitney U | Z | p value a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||||

| Fear of nonavailability of grocery stocks | 2.05 | 1.279 | 3.00 | 1.289 | 2.37 | 1.355 | 3,073.500 | −4.840 | .000 |

| Fear of getting infected from grocery storekeepers | 2.25 | 1.000 | 3.22 | 1.345 | 2.58 | 1.219 | 2,976.00 | −.5.046 | .000 |

| Fear of getting infected from other shoppers | 3.24 | 1.291 | 3.72 | 1.116 | 3.40 | 1.252 | 4,014.00 | −2.500 | .012 |

| Safety of the foods that I am purchasing | 3.27 | 1.291 | 2.15 | 1.479 | 2.89 | 1.454 | 2,891.00 | −5.217 | .000 |

| Nonavailability of fresh food products | 4.16 | 1.049 | 2.87 | 1.393 | 3.72 | 1.324 | 2,530.00 | −6.213 | .000 |

Note: Most important concern = 1, least important concern = 5.

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

Mann‐Whitney U test for homogeneity of proportion between male and female.

7. CONSUMER GROCERY SHOPPING BEHAVIOR

In order to assess consumer grocery shopping behavior, respondents were asked about their grocery shopping habits, frequency, and preferences (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Self‐reported survey results of respondents' grocery shopping behavior during COVID‐ 19 outbreak

| Male | Female | Total | χ 2 | p value a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | N (%) | |||

| Changes in shopping habits | |||||

| Yes | 112 (80) | 64 (88.9) | 176 (83) | 2.66 | .103 |

| No | 28 (20) | 8 (11.1) | 36 (17) | ||

| Frequency of grocery shopping | |||||

| Every day | 12 (8.6) | 6 (8.3) | 18 (8.5) | ||

| Two or three times a week | 13 (9.3) | 9 (12.5) | 22 (10.4) | 1.93 | .749 |

| Once a week | 92 (65.7) | 41 (56.9) | 133 (62.7) | ||

| Once every two weeks | 16 (11.4) | 11 (15.4) | 27 (12.7) | ||

| Once a month | 7 (5) | 5 (6.9) | 12 (5.7) | ||

| Do shopping list | |||||

| Always | 89 (63.6) | 58 (80.6) | 147 (69.3) | ||

| Sometimes | 35 (25) | 8 (11.1) | 43 (20.3) | 6.93 | .031 |

| Never | 16 (11.4) | 6 (8.3) | 22 (10.4) | ||

| Avoid buying unpackaged items | |||||

| Always | 112 (80) | 59 (81.9) | 171 (80.7) | ||

| Sometimes | 21 (15) | 7 (9.7) | 28 (13.2) | 1.887 | .389 |

| Never | 7 (5) | 6 (8.3) | 13 (6.1) | ||

| Using Cashless transaction to make payments at grocery shop | |||||

| Always | 107 (76.4) | 41 (56.9) | 148 (69.8) | ||

| Sometimes | 22 (15.7) | 26 (36.1) | 48 (22.6) | 11.375 | .003 |

| Never | 11 (7.9) | 5 (6.9) | 16 (7.5) | ||

| Purchased new brand of food products | |||||

| Yes, purchased more new brand | 74 (52.9) | 35 (48.6) | 109 (51.4) | ||

| No, purchased same brand as usual | 52 (37.1) | 26 (36.1) | 78 (36.8) | 1.304 | .521 |

| Not sure | 14 (10) | 11 (15.3) | 25 (11.8) | ||

| Try to shop quickly and efficient | |||||

| Always | 102 (72.9) | 51 (70.8) | 153 (72.2) | ||

| Sometimes | 26 (18.6) | 16 (22.2) | 42 (19.8) | .504 | .777 |

| Never | 12 (8.6) | 5 (6.9) | 17 (8) | ||

| Plan to do online grocery shopping more | |||||

| Yes | 92 (65.7) | 45 (62.5) | 137 (64.6) | ||

| Maybe | 24 (17.1) | 16 (22.2) | 40 (18.9) | ||

| No | 15 (10.7) | 6 (8.3) | 21 (9.9) | 1.01 | .797 |

| Not sure | 9 (6.4) | 5 (6.9) | 14 (6.6) | ||

Chi‐square test for homogeneity of proportions between male and female.

When respondents were asked has COVID‐19 lockdown changed your grocery shopping habits, 83% of the respondents have answered positively and among them majority were female respondents. However, no significant differences were found between male and female with respect to change in habits of grocery shopping. To the question of the frequency for grocery shopping, 62.7% of the respondents reported once a week, once every two weeks reported by 12.7%, two or three times a week reported by 10.4%, and 8.5% respondents reported every day, and once a month declared by 5.7%. A statistically significant difference was not achieved between male and female on the frequency of grocery shopping. Regarding doing a shopping list, 69.3% of the respondents declared they “always” made shopping list, while 20.3% of respondents declared doing this “sometimes,” and 10.4% stated they “never” made shopping list during COVID‐19 lockdown while going for grocery shopping. Among respondents who did shopping list ‘always,’ the majority of them were “female”. Also, significant differences were measured (p = .031, p < .05) between male and female on doing a shopping list during ongoing COVID‐19 lockdown.

To the question of avoiding unpackaged item, respondents were asked whether they are avoiding buying unpackaged items since the COVID‐19 pandemics began, a large majority (80.7%) of respondents affirmed “always” avoiding unpackaged items, while 13.2% stated doing this “sometimes,” and only 6.1% reported they “never” avoided buying unpackaged items. No statistically significant difference was observed between male and female on avoiding buying unpackaged items. Regarding cashless transactions to make payments at the grocery stores, 69.8% of the respondents declared that they “always” made payments using cashless methods, while 22.6% of respondents reported doing this “sometimes,” and 7.5% of respondents affirmed they “never” made payments through cashless methods. Among them who ‘always’ made payments through cashless methods, the majority of them were “male” and also a statistically significant value of p = .003 was found between male and female in using cashless methods to make payments at the grocery stores as a result of COVID‐19 pandemic.

The study revealed that over half (51.4%) of the respondents had made purchases of food products from brands that were new to them since the pandemic began, while 36.8% respondents reported purchasing of same usual brand of food products, and 11.8% respondents declared they were not sure about it. No statistical difference was noticed between male and female on purchasing new brands of food products since the COVID‐19 pandemic began. Also, the majority (72.2%) of the respondents affirmed since the pandemic began they “always” tried to shop quickly and efficiently, while 19.8% of respondents declared doing this “sometimes,” and only 8% of respondents reported they “never” tried doing this. A statistically significant difference was not found between male and female to try to shop quickly and efficiently. Respondents were further asked whether they will plan to shop online more as a result of COVID‐19, majority (64.6%) of the respondents affirmed “yes,” while 18.9% stated “maybe,” 9.9% reported “No,” and 6.6% declared they are “not sure”. The statistically significant difference was not established between male and female in their plan to do online shopping more as a result of COVID‐19.

8. CONSUMER ADOPTION OF HEALTHIER FOOD

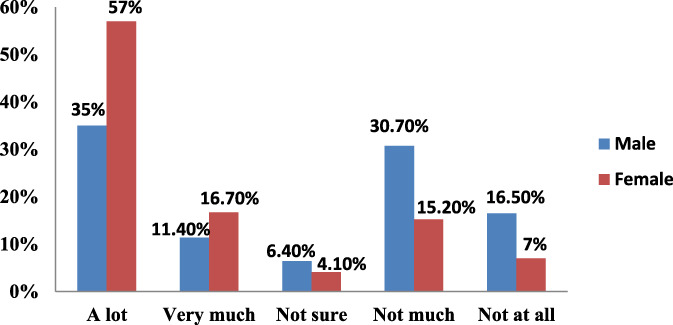

When respondents were asked whether COVID‐19 influenced them to adopt healthier food habits, 55.7% of the respondents stated COVID‐19 influenced them to eat healthier food (Figure 1), while 38.7% of the respondents declared they were not influenced, and 5.6% respondents reported they were “not sure” about it. The statistical significance difference between demographic variables and the influence of COVID‐19 pandemic on the adoption of healthier eating was tested using logistic regression. The results are given in Table 5. Among the demographic indicators of the respondents, the estimated coefficients of gender, age, and monthly household income were found statistically significant, indicating that these factors are likely to influence the adoption of healthier eating. The model is reasonably a good fit, approximately 66% of the observations are correctly predicted. The chi‐square test of the measure of overall significance of the model with 5° of freedom is significant at 1% level. The log‐likelihood model, which measures the goodness of fit, is 225.954. This ratio is relatively low, implying that the model fit is perfect.

FIGURE 1.

Consumer response on adoption of healthier food habits as a result of COVID‐19 pandemic

TABLE 5.

Estimated results of logistic regression

| Dependent variables A lot or very much influenced by COVID‐19 to eat healthier food = 1, otherwise = 0 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | β | SE | Sig | Exp(β) |

| Constant | .679** | 0.317 | 0.032 | 1.971 |

| Gender (male = 1, female = 0) | 1.333* | 0.342 | 0.000 | 3.791 |

| Age (Below 40 = 1, otherwise = 0) | −.809** | 0.344 | 0.019 | .445 |

| Education (Postgraduate and above =1, otherwise = 0) | .301 | 0.312 | 0.335 | 1.351 |

| Monthly household Income (INR above 40,000 = 1, otherwise =0) | −1.086* | 0.317 | 0.001 | .338 |

| Profession (Employed and Business =1, otherwise = 0) | −.513 | 0.323 | 0.112 | .599 |

| Log‐likelihood | 255.954 | |||

| Cox and Snell R 2 | .153 | |||

| Nagelkerke R 2 | .205 | |||

| Chi‐square (df = 5) | 35.218* | |||

| Corrected prediction (%) | 66.5 | |||

Statistically significant at the .01 level, respectively.

Statistically significant at the .05 level, respectively.

The results suggest that females are more likely to adopt healthier eating habits as compared to males. Consumers who are below age 40 years are more likely to adopt healthier eating habits as compared to those who are above 40 years. The results also suggest that consumers who have a monthly household income of INR 40,000 and above are more likely to adopt healthy eating habits.

9. DISCUSSION

The findings of this study showed that majority of the sample participants “always” wore masks at the grocery store and ‘always’ washed or sanitized their hands after grocery shopping. The study also revealed that females are more consistent and taking the significance of hand hygiene and wearing a mask more seriously than male. It may be due to the fact that males more than females believe that they will be relatively unaffected by the infection, but this is extremely ironic since official statistics show that the coronavirus (COVID‐19) actually affects males more seriously than females (Capraro & Barcelo, 2020). Since hand hygiene and wearing masks are one of the most effective actions suggested by World Health Organization (WHO, 2020b) to reduce the spread of COVID‐19 virus, more encouragement is needed to indulge in proper hand washing or sanitizing, especially for males. 42.9% of the respondents “always” cleaned the bought packaged items, which they have bought from grocery stores, and only 28.8% of the respondents declared ‘always’ tried to avoid touching surfaces unnecessarily during grocery shopping.

This study showed that as compared to males, females are more frequent in cleaning the bought packaged goods and in avoiding touching surfaces unnecessarily at the grocery stores. It may partly be explained by the fact that females are traditionally more involved in house cleaning and hygiene, as it relates to image and perception (Jackson & Newall, 2018). However, it is not known how long the virus coronavirus survives on surfaces, and it is important to note that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization have stressed that regular cleaning of frequently touched surfaces are helpful in preventing the spread of Covid‐19 (Gray, 2020). The risk of contracting virus from foodstuffs, packaged food, or other packages has been stated as low, but following good food safety practices is always pertinent (CDC, 2020a). While following physical distancing is a well‐known suggestion for protecting oneself from COVID‐19, only 37.3% of the respondents stated following physical distancing ‘always’ during grocery shopping at the grocery store, and most of them were female respondents, which are consistent with the survey study of Altrum (2020). Over one‐fourth of the respondents claimed that they ‘always’ changed their clothes after coming from the grocery. In this perspective, it would be important to note that it is presently unclear how long the COVID‐19 virus can sustain on the clothes, but many clothing items have metal and plastic components on which it could last for a few hours to few days (UNICEF, 2020).

Taken together, it can be said that female consumers are more aware of the significance of wearing masks and washing or sanitizing their hands as compared to male consumers but frequency of following physical distancing for both male and female respondents was not up to the mark. This raises concerns about consumer health safety practices while grocery shopping in the ongoing COVID‐19 pandemic.

As a result of COVID‐19 pandemic, the most important concern for male respondents about grocery shopping was “fear of nonavailability of grocery stocks” and “fear of getting infected from grocery store keepers,” while for female respondents the most important concerns were “safety of the foods that I am purchasing” and “nonavailability of fresh food products.” It can be explained by the fact that male shoppers consider convenience and efficiency to be the most significant factors during grocery shopping and, in contrast, female shoppers pursue cleanliness and quality characteristics (Mortimer & Clarke, 2011).

A large majority of respondents affirmed that their shopping habits have changed as a result of COVID‐19 lockdown, which corresponds to the findings of Jribi et al. (2020). Regarding the frequency of grocery shopping, majority (62.7%) of the consumers declared that they performed grocery shopping once a week and only 8.5% of respondents reported doing grocery shopping every day. In contrast, in the study of Sassi et al. (2016), 34.5% of participants stated that they were shopping daily. As a result, our study findings have shown the influence of the COVID‐19 epidemic on the frequency of grocery shopping. The majority (69.3%) of the respondents declared that they “always” did shopping lists in the ongoing pandemic. However, in the study of Inman et al. (2009), 54% were shopping list users and in the study of Hui et al. (2013), 37% carried shopping lists. Thus, our results also showed an influence of COVID‐19 epidemic on doing shopping lists.

The findings of the study also showed that female respondents are more frequent on doing shopping list as compared to male respondents, it may be noted that Gardner (2004) and Piron (2002) have observed that males use less shopping list and also do less preplanning compared to females. Also, the majority of the respondents claimed that since the pandemic began, they try to shop quickly and efficiently. It is worth mentioning here that previous studies (Hui et al., 2013; Inman et al., 2009; Schmidt, 2012; Thomas & Garland, 2004) suggest that shopping lists keep consumers focused on and reduce the likeliness of unplanned purchases, thus facilitating efficient shopping. The majority of the respondents stated that they were avoiding buying unpackaged food products that indicate consumers have bought more packaged food as a result of the COVID‐19 pandemic, which is similar to the findings of Bhutani et al. (2020) and IFIC Consumer Survey (2020a).

In response to the ongoing pandemic, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, 2020) have encouraged the individuals to make use of digital payment options. In this context, it is also worth mentioning that, in India, digital payment firms have registered a spike in digital transactions for the purchase of essential products since the lockdown commenced (Surabhi, 2020). The Indian e‐commerce payment company “Paytm” announced a fourfold increase in their services, both in terms of new users and the total number of daily transactions during the ongoing COVID‐19 lockdown (PTI, 2020). This study revealed that majority of the respondents stated performing cashless transactions to make payment at the grocery stores as a result of COVID‐19 lockdown, which is consistent with the findings of Baig et al. (2020). The frequency of male respondents in using cashless transaction was higher than females' respondents, it may be due to less practice of using internet services like digital payment wallets, as has been noted by Singh et al. (2017), that females in developing countries are 16% less likely than male to use the internet services on average. Over half (51.4%) of respondents had made purchases from brands that were new to them, consistent with the results of Knowles et al. (2020), where 54% had made purchases from brands that were new to them, while just over one‐fourth of the respondents declared they had purchased the same brand as they usually do.

The majority of respondents said they were planning to shop online more as a result of ongoing COVID‐19 epidemic, which matches the result of the Criteo Coronavirus Survey (CDC, 2020c). In this context, it is significant to note that online grocery shopping can provide discerning benefits to consumers, including comfort and home delivery and, from the perspective of COVID‐19, physical distancing, which is highly encouraged by the governments to follow in this COVID‐19 crisis to stop the spread of the virus. WHO (2020b) suggested that eating healthy food is always important for the immune system of our body. During this COVID‐19 pandemic, consumption of healthy food can positively affect our body's ability to prevent, fight, and recover from coronavirus infection. A recent study done by Food, Media, and Society (FOOMS, n.d.) Unit at the University of Antwerp, Belgium found out that the lockdown put back the focus on a healthy lifestyle in a lot of people.

This study revealed that gender, age, and household income significantly impact the adoption of healthy eating habits. Females were more likely to adopt healthy eating habits as compared to males that indicate females are more aware about the significance of eating healthy food which is in harmony with the previous studies (Arganini et al., 2012; Wardle et al., 2004). More generally, females are more inclined toward the intake of fruits and vegetables and high fiber and less inclined in consuming fat and salts (Manippa et al., 2017). Higher‐income respondents were more related to adopting healthier eating habits, it may be due to the fact that income mediates food purchasing pattern, as lower‐income household purchase less healthy food compared with higher‐income household (French et al., 2019). Respondents who were aged below 40 years were more likely to adopt eating healthy habits (Gustafson, 2017), this is likely due to the fact that, now younger generations are more health conscious than previous generations, and they are tech‐savvy peoples, and are frequently exposed to the global trends, and lifestyle, and are willing to spend more money for healthier food (Nielsen, 2018).

10. CONCLUSION

This study provides insights on consumers' health safety practices and their changed habits toward grocery shopping as a result of the COVID‐19 outbreak with the help of primary survey data. This study clearly indicates that respondents are taking significant health safety measures while shopping for groceries in grocery store, but frequency of following physical distancing at grocery store was not up to the mark; therefore, there is a need to raise awareness among people about the risk of being infected by not following physical distancing. Our findings suggest that females are forging ahead compared to males in pursuing safety practices during grocery shopping in the ongoing COVID‐19 pandemic. As a result of the COVID‐19 lockdown, the most important concern for people regarding grocery shopping was fear of the nonavailability of grocery stocks, which indicate governments and business entities need to ensure people that there will be no shortage of food and grocery stocks in the ongoing pandemic. It is envisaged that grocery store owners will need to deliver a customer‐centric experience including cleaning and disinfecting frequently touched surfaces and practice proper hygiene at the store that should send a message that consumer safety has been prioritized. Now more people are doing shopping list, many have reduced their frequency of grocery shopping, and try to shop quickly and efficiently. Most of the people have bought more packaged food and also made purchases from brands that were new to them as a result of COVID‐19 pandemic.

This study also brings out the fact that people are embracing digital payment options, which facilitate physical distancing and mitigate the risk of infection; however, compared to males, females lag behind in this context; therefore, e‐payment companies ought to ensure hassle‐free services and connect their services to every possible grocery store to make it more convenient for every group of people. It was also found that people were intending to shop groceries online more as a result of COVID‐19 outbreaks. E‐commerce based companies have to create a system that would facilitate contactless deliveries and delivery of groceries more timely as well as safely. Based on the findings of our study, it can be safely concluded that people have adopted healthier food habits but still there is need to make people aware of the benefits of eating healthy food that supports the immune system of our body and helps in preventing, fighting, and recovering from COVID‐19 infection. Gender, age, and household income of the respondents were found significant in adopting the healthier food habits as a result of COVID‐19 pandemic. It is expected that these findings will help policymakers, communities, and companies to better deal with ongoing COVID‐19 crises and similar crises in the future.

11. LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY

The data collection process and the small sample size are the main limitations of the study as online survey cannot reach the people who are not comfortable with technology or who do not have access to technology or the internet; therefore, it also raises the limits of the sampling methods. Moreover, this study was based on self‐reported data, in which the respondents may tend to behave ideally rather than being realistic while answering questions in the questionnaire. Therefore, generalizations cannot be made. The behavior and perceived changed habits may also vary region‐wise and product category‐wise. To validate these findings further research is needed. Further studies may be taken with larger samples and with the variation in their place of residence and demographic variables.

Biographies

Khalid Shamim is a doctoral student in the department of Agricultural Economics & Business Management, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh. His research interest includes food marketing, green marketing, and consumer behavior. He has a Masters in Business Administration with major in Agribusiness.

Shamim Ahmad is a professor in the department of Agricultural Economics & Business Management, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh. His research interest traverses agribusiness marketing, ICT application, Commodity, and Food Marketing. He has a teaching and research experience of 38 years.

Md Ashraf Alam is a doctoral student in the department of Industrial and Management Engineering, Indian Institute of Technology, Kanpur. His research interest varies widely from modeling of supply chains to doing research on market trends and consumer behavior. He has a Masters in Industrial Engineering from Indian Institute of Technology Delhi, New Delhi.

Shamim K, Ahmad S, Alam MA. COVID‐19 health safety practices: Influence on grocery shopping behavior. J Public Affairs. 2021;21:e2624. 10.1002/pa.2624

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

REFERENCES

- Altrum Institute . (2020). Survey of Michigan residents. Retrieved from https://altarum.org/news/men-lag-behind-women-following-social-distancing-measures-according-survey-michigan-residents

- Arganini, C. , Turrini, A. , Saba, A. , Virgili, F. , & Comitato, R. (2012). Gender differences in food choice and dietary intake in modern western societies. In Maddock J. (Ed.), Public Health—Social and Behavioral Health (pp. 85–102). IntechOpen. [Google Scholar]

- Baig, A. , Hall, B. , Jenkins, P. , Lamarre, E. , & McCarthy, B. (2020). The COVID‐19 recovery will be digital: A plan for the first 90 days. McKinsey Digital. [Google Scholar]

- Bhutani, S. , Cooper, J. A. , & Vandellen, M. R. (2020). Self‐reported changes in energy balance behaviors during COVID‐19 related home confinement: A cross‐sectional study. medRxiv. 10.1101/2020.06.10.20127753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capraro, V. , & Barcelo, H. (2020). The effect of messaging and gender on intentions to wear a face covering to slow down COVID‐19 transmission; arXiv preprint arXiv:2005. p. 05467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Centre for Disease Control and prevention (CDC) (2020). What grocery and food retail workers need to know about COVID‐19 Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019‐ncov/community/organizations/grocery‐food‐retail‐workers.html

- Criteo Coronavirus Survey. CDC . (2020a). Coronavirus (COVID‐19). Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/index.html

- Criteo Coronavirus Survey. CDC . (2020b). Coronavirus consumer trends: Consumer electronics, pet supplies, and more. Retrieved from https://www.criteo.com/insights/coronavirus-consumer-trends/

- Criteo Coronavirus Survey. CDC . (2020c). Coronavirus (COVID‐19). Retrieved from https://www.criteo.com/insights/coronavirus‐consumer‐behavior/

- Dillon, W. R. , Madden, T. J. , & Firtle, N. H. (1994). Marketing research in a marketing environment: Irwin. Richard D. Irwin, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, N. M. , Laydon, D. , Nedjati‐Gilani, G. , Imai, N. , Ainslie, K. , Baguelin, M. , Bhatia, S. , Boonyasiri, A. , Cucunubá Z., Cuomo‐Dannenburg, G. , Dighe, A. , Dorigatti, I. , Fu, H. , Gaythorpe, K. , Green, W. , Hamlet, A. , Hinsley, W. , Okell, L. C. , van Elsland, S. , …, Ghani, A. C. (2020). Impact of non‐pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to reduce COVID‐19 Mortality and Healthcare Demand. Imperial College; London.

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (2020a). Retrieved from https://www.fda.gov/food/food-safety-during-emergencies/shopping-food-during-covid-19-pandemic-information-consumers

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA) . (2020b). COVID‐19 shopping for food during the COVID‐19 pandemic‐information for consumers. Retrieved from https://www.fda.gov/food

- Food, Media and Society (FOOMS) . (n.d.). Corona Cooking Survey 2020. Retrieved from https://www.uantwerpen.be/en/projects/food-media-society/corona-cooking-survey/

- Foundation IFIC . 2020a. Consumer Survey: COVID‐19's impact on food purchasing, eating behaviors and perceptions of food safety . Retrieved from https://foodinsight.org/consumer-survey-covid-19s-impact-on-food-purchasing/

- French, S. A. , Tangney, C. C. , Crane, M. M. , Wang, Y. , & Appelhans, B. M. (2019). Nutrition quality of food purchases varies by household income: The SHoPPER study. BMC Public Health, 19, 231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, M. (2004). What men want—in the supermarket. The Christian Science Monitor, 23(1), 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, R . (2020). Covid‐19: How long does the coronavirus last on surfaces? BBC FUTURE. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20200317-covid-19-how-long-does-the-coronavirus-last-on-surfaces

- Gustafson, R. D. T. (2017). Younger consumers are more health conscious than previous generations. Huffpost. Retrieved from https://www.huffingtonpost.ca/timi‐gustafson/younger‐consumers‐are‐mor_b_14290774.html

- Hui, S. K. , Huang, Y. , Suher, J. , & Inman, J. J. (2013). Deconstructing the “First Moment of Truth”: Understanding unplanned consideration and purchase. Journal of Marketing Research, 50(4), 445–462. [Google Scholar]

- Inman, J. J. , Winer, R. S. , & Ferraro, R. (2009). The interplay among category characteristics, customer characteristics, and customer activities on in‐store decision making. Journal of Marketing, 73, 19–29. [Google Scholar]

- Iyer, E. S. (1989). Unplanned purchasing: Knowledge of shopping environment and time pressure. Journal of Retailing, 65(1), 40. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, C. , & Newall, M. (2018). Ipsos public affairs; hygiene and cleanliness in the U.S . Retrieved from https://www.ipsos.com/en-us/news-polls/Hygiene-and-Cleanliness

- Jribi, S. , Ben Ismail, H. , Doggui, D. , & Debbabi, H. (2020). COVID‐19 virus outbreak lockdown: What impacts on household food wastage? Environment, Development and Sustainability, 22, 3939–3955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles, J. , Ettenson, R. , Lynch, P. , & Dollens, J. (2020). Growth opportunities for brands during the COVID‐19 crisis. MIT Sloan Management Review, 61(4), 2–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kolodinsky, J. , Sitaker, M. , Chase, L. , Smith, D. , & Wang, W. (2020). Food systems disruptions: Turning a threat into an opportunity for local food systems. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development, 9(3), 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C. W. , Hsieh, A. Y. , Lo, S. K. , & Hwang, Y. (2017). What consumers see when time is running out: Consumers' browsing behaviors on online shopping websites when under time pressure. Computers in Human Behavior, 70, 391–397. [Google Scholar]

- Manippa, V. , Padulo, C. , van der Laan, L. N. , & Brancucci, A. (2017). Gender differences in food choice: Effects of superior temporal sulcus stimulation. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 11, 597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin‐Neuninger, R. , & Ruby, M. B. (2020). What does food retail research tell us about the implications of Coronavirus (COVID‐19) for grocery purchasing habits? Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortimer, G. , & Clarke, P. (2011). Supermarket consumers and gender differences relating to their perceived importance levels of store characteristics. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 18, 575–585. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen . 2018. Nielsen Global Health and Wellness Report. Retrieved from https://www.nielsen.com/in/en/news-center/2019/nielsen-releases-2nd-annual-global-well-report/

- Park, C. W. , Iyer, E. S. , & Smith, D. C. (1989). The effects of situational factors on in‐store grocery shopping behavior: The role of store environment and time available for shopping. Journal of Consumer Research, 15(4), 422–433. [Google Scholar]

- Piron, F. (2002). Singaporean husbands and grocery shopping: An investigation into claims of changing spousal influence. Singapore Management Review, 24(1), 51–66. [Google Scholar]

- Press Trust of India . (2020). COVID‐19. Firstpost. Retrieved from https://www.firstpost.com/health/coronavirus‐outbreak‐paytm‐records‐4‐timesgrowth‐inpayments‐made‐to‐merchants‐during‐lockdown‐8393701.html

- Rawal, V. , & Kumar, A. (2020). Agricultural supply chains during the COVID‐19 lockdown: A study of market arrivals of Seven Key Food commodities in India, SSER Monograph. Society for Social and Economic Research, 20, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, J. R. A. (1999). Cronbach's alpha: A tool for assessing the reliability of scales. Journal of Extension, 37(2), 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Sassi, K. , Capone, R. , Abid, G. , Debs, P. , El Bilali, H. , Daaloul, B. O. , Bottalico, F. , & Driouech, N. (2016). Food wastage by Tunisian households. International Journal AgroFor, 1(1), 172–181. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, C. , Goetz, S. , Rocker, S. , & Tian, Z. (2020). Google searches reveal changing consumer food sourcing in the COVID‐19 pandemic. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development, 9(3), 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, M. (2012). Retail shopping lists: Reassessment and new insights. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 19, 36–44. [Google Scholar]

- Sheth, J. (2020). Impact of Covid‐19 on consumer behavior: Will the old habits return or die? Journal of Business Research, 117, 280–283. 10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.05.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh, N. , Srivastava S., & Sinha N. (2017). Consumer preference and satisfaction of M‐wallets: a study on North Indian consumers. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 35(6), 944–965. 10.1108/ijbm-06-2016-0086. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Statista . (2020). India opinion on coronavirus fear and concerns . Retrieved from https://www.statista.com/statistics/1111149/india-opinion-on-coronavirus-fears-andconcerns/

- Surabhi. (2020). Customer prefer Contactless shopping. The Hindu Business Line. Retrieved from https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/money-and-banking/more-kirana-shops-acceptdigital-payments-as-customers-prefer-contactless-shopping/article31677347.ece

- Thomas, A. , & Garland, R. (2004). Grocery shopping: List and non‐list usage. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 22, 623–635. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF (2020); Cleaning and hygiene tips to help keep the COVID‐19 virus out of your home . Retrieved from https://www.unicef.org/

- Wang, C. , Pan, R. , Wan, X. , Tan, Y. , Xu, L. , Ho, C. S. , & Ho, R. C. (2020). Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID‐19) epidemic among the general population in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(5), 1729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward, A. (2020). India's coronavirus lockdown and its looming crisis, explained. Vox.com. Retrieved from https://www.vox.com/March242020/21190868/coronavirus-india-modilockdownkashmir

- Wardle, J. , Haase, A. M. , Steptoe, A. , Nillapun, M. , Jonwutiwes, K. , & Bellisie, F. (2004). Gender differences in food choice: The contribution of health beliefs and dieting. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 27(2), 107–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2020a); Retrieved from https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/events-as-they-happen

- World Health Organization (WHO) . (2020b). Retrieved from https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public

- Worstell, J. (2020). Ecological Resilience of Food Systems in Response to the COVID‐19 Crisis. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development, 9(3), 23–30. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.