Abstract

Background:

Diethyl phthalate (DEP) is widely used in many commercially available products including plastics and personal care products. DEP has generally not been found to share the antiandrogenic mode of action that is common among other types of phthalates, but there is emerging evidence that DEP may be associated with other types of health effects.

Objective:

To inform chemical risk assessment, we performed a systematic review to identify and characterize outcomes within six broad hazard categories (male reproductive, female reproductive, developmental, liver, kidney, and cancer) following exposure of nonhuman mammalian animals to DEP or its primary metabolite, monoethyl phthalate (MEP).

Methods:

A literature search was conducted in online scientific databases (PubMed, Web of Science, Toxline, Toxcenter) and Toxic Substances Control Act Submissions, augmented by review of online regulatory sources as well as forward and backward searches. Studies were selected for inclusion using PECO (Population, Exposure, Comparator, Outcome) criteria. Studies were evaluated using criteria defined a priori for reporting quality, risk of bias, and sensitivity using a domain-based approach. Evidence was synthesized by outcome and life stage of exposure, and strength of evidence was summarized into categories of robust, moderate, slight, indeterminate, or compelling evidence of no effect, using a structured framework.

Results:

Thirty-four experimental studies in animals were included in this analysis. Although no effects on androgen-dependent male reproductive development were observed following gestational exposure to DEP, there was evidence including effects on sperm following peripubertal and adult exposures, and the overall evidence for male reproductive effects was considered moderate. There was moderate evidence that DEP exposure can lead to developmental effects, with the major effect being reduced postnatal growth following gestational or early postnatal exposure; this generally occurred at doses associated with maternal effects, consistent with the observation that DEP is not a potent developmental toxicant. The evidence for liver effects was considered moderate based on consistent changes in relative liver weight at higher dose levels; histopathological and biochemical changes indicative of hepatic effects were also observed, but primarily in studies that had significant concerns for risk of bias and sensitivity. The evidence for female reproductive effects was considered slight based on few reports of statistically significant effects on maternal body weight gain, organ weight changes, and pregnancy outcomes. Evidence for cancer and effects on kidney were judged to be indeterminate based on limited evidence (i.e., a single two-year cancer bioassay) and inconsistent findings, respectively.

Conclusions:

These results suggest that DEP exposure may induce androgen-independent male reproductive toxicity (i.e., sperm effects) as well as developmental toxicity and hepatic effects, with some evidence of female reproductive toxicity. More research is warranted to fully evaluate these outcomes and strengthen confidence in this database.

Keywords: Phthalates, Diethyl phthalate, Systematic review, Risk assessment

1. Introduction

Diethyl phthalate (DEP), a colorless, odorless oily substance, is used to improve the performance and durability of many products (Consumer Product Safety Commission 2011; World Health Organization 2003). As a plasticizer, it is added to plastic polymers to help maintain flexibility. It has been used in a variety of products including plastic films, rubber, tape, toothbrushes, automotive components, tool handles and toys. In addition to plastics, DEP is present in a wide range of personal care products (e.g., cosmetics, perfume, hair spray, nail polish, soap, detergent, and lotions), industrial materials (e.g., rocket propellant, dyes, packaging, sealants and lubricants), and medical products (e.g., enteric coatings on tablets and in dental impression materials).

Phthalates including DEP are not covalently bound to products, and therefore are readily released into the environment where they may be absorbed orally, by inhalation, or dermally (Clark et al. 2011; Wormuth et al. 2006). Following oral exposure in rats, DEP primarily locates to the kidneys and liver followed by deposition in fat (Singh et al. 1975). DEP is rapidly metabolized into the active metabolite monoethyl phthalate (MEP), which is ultimately excreted into the urine and serves as a biomarker of DEP exposure. Exposure assessment data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) show that MEP was detected in the urine of at least 98% of participants in the US general population in each survey cycle between 2001 and 2010; urinary concentrations of MEP declined significantly over that time, with a more pronounced trend towards decreased urinary MEP in adults and adolescents compared to children, perhaps reflecting a trend towards decreased use of DEP in personal care products (Zota et al. 2014). Despite this trend, MEP levels tended to remain higher compared to other phthalate metabolites in urine across age groups in this study (Zota et al. 2014). Other analyses of biomonitoring data have similarly found that DEP is among the highest phthalate exposures for women of childbearing age, with personal care products being a major source (Consumer Product Safety Commission 2014; National Research Council 2008).

Unlike multiple other phthalates, DEP has not been found to inhibit fetal testosterone production (Consumer Product Safety Commission 2014), which is one of the major mechanisms underlying the “phthalate syndrome” phenotype that is observed in male rats following gestational exposure to certain phthalates. Phthalate syndrome is characterized by a spectrum of effects including underdevelopment of male reproductive organs, decreased anogenital distance (AGD), female-like nipple retention, cryptorchidism, and germ cell toxicity (Consumer Product Safety Commission 2014; National Research Council 2008). These effects are driven not only by a phthalate-induced decrease in testicular testosterone production, but also by decreased production of insulin-like-3 hormone and disrupted seminiferous cord formation, Sertoli cells, and germ cell development, which occur independently of changes in androgen production (Johnson et al. 2012; Martino-Andrade and Chahoud 2010; National Research Council 2008). A recent review by a Chronic Hazard Advisory Panel (CHAP), which focused on phthalates and phthalate alternatives used in children’s toys and child care products, found that DEP does not cause phthalate syndrome in rats, although decreased testosterone and effects on sperm were observed in some studies in adult and peripubertal animals, and there were some associations between urinary MEP and male reproductive outcomes in humans (Consumer Product Safety Commission 2014). Based on these findings, the CHAP did not recommend that DEP be banned from children’s toys and childcare products, particularly because these products are considered a negligible source of DEP exposure. However, the CHAP concluded that since exposures from personal care products, diet, and some pharmaceuticals can be substantial, exposure to DEP remains a concern and warrants further evaluation (Consumer Product Safety Commission 2014).

The aim of this study is to characterize the range of health outcomes associated with DEP exposure in animal toxicology studies using systematic review methods, which were not used in the CHAP review of phthalates. Our analysis includes evaluation of effects in both males and females and for all life stages of exposure, focusing on six broad hazard categories: male reproductive, female reproductive, developmental, liver, kidney, cancer. These hazard categories have been identified by our group as being broadly associated with phthalate exposure and were selected a priori due to the likelihood that they would have sufficient data available for hazard identification. The results can inform chemical risk assessment by providing a more comprehensive understanding of the effects of DEP exposure and identifying gaps in the currently available literature.

2. Methods

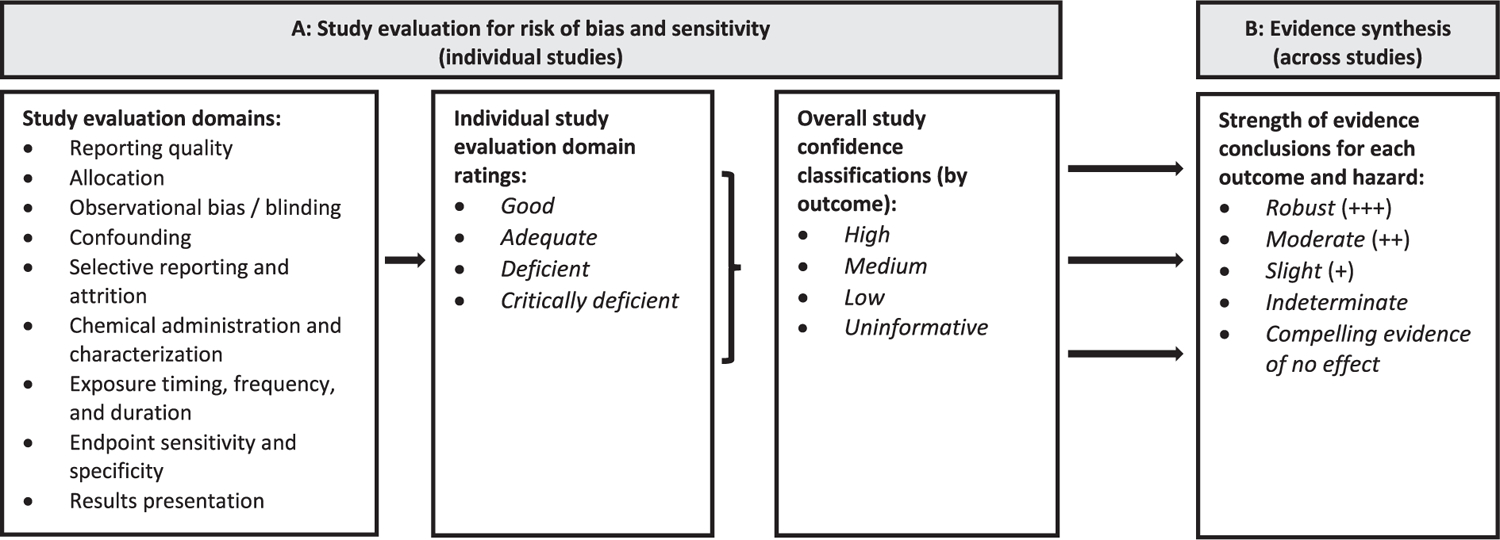

Our group has published several systematic reviews of epidemiological and animal toxicological studies describing health effects following exposure to phthalates (Radke et al. 2018; Radke et al. 2019a, 2019b; Radke et al. 2020; Yost et al., 2019). This systematic review continues the evaluation of health effects after exposure to phthalates by focusing on animal studies of DEP. The literature searches and screening, study evaluation, data extraction, and evidence synthesis methods are described in detail in the systematic review protocol (provided as a supplementary file) and summarized here. The systematic review protocol also provides detailed definitions for the terminology used to describe study evaluation and evidence synthesis, which are summarized in Fig. 1. For easier reference, these definitions and key methods from the protocol related to study evaluation and evidence synthesis are also summarized in a separate supplementary file (“key methods supplement”). The systematic review methodology used here has been reviewed previously by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2018) and was used in the systematic review of animal studies for diisobutyl phthalate (Yost et al. 2019), and reporting is in accordance with the checklist from PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) (http://www.prisma-statement.org/).

Fig. 1.

(A) Study evaluation criteria and (B) strength of evidence characterization for DIBP animal toxicology studies.

2.1. Literature searches and screening

A literature search was conducted in online scientific databases [PubMed, Web of Science, Toxline, Toxcenter] and Toxic Substances Control Act Test Submissions (TSCATS),2 using search terms designed to capture all potentially pertinent studies. Initial database searches were conducted as early as March 2012, with updates of PubMed, Web of Science, and Toxline performed periodically through January 2020 (see protocol Section 3). The literature search strings used for PubMed and Web of Science evolved over time, but the final literature update in January 2020 was conducted using additional chemical synonyms and with topical terms removed and with no date limitations in order to capture a broader array of studies. The results of this literature search were supplemented by forward and backward searches, searching citations from key references, manual search of citations from key regulatory documents, and by addition of references that had been previously identified from an earlier DEP review effort and added to EPA’s Health and Environmental Research Online (HERO) database (https://hero.epa.gov/hero/index.cfm/project/page/project_id/1097). The number of studies identified from each source and literature update can be found on the HERO project page.

A PECO (Population, Exposure, Comparator, Outcome) was developed to frame the research question and guide the screening of relevant studies. The PECO identifies the following as the inclusion criteria for the systematic review of DEP animal toxicology studies (see protocol Section 2 for the full PECO):

Population: Nonhuman mammalian animal species (whole organism) of any life stage.

Exposure: Any administered dose of DEP or MEP as singular compounds, via oral, dermal, or inhalation routes of exposure.

Comparator: Exposure to vehicle-only or untreated control

Outcome: Any examination of male reproductive, female reproductive, developmental, liver, kidney, or cancer outcomes.

Title/abstract and full text screening were performed by two reviewers, and all identified animal toxicology studies underwent full-text screening to determine compliance with the PECO. Peer-reviewed studies that contained original data and complied with the PECO were selected for inclusion and were moved forward for study evaluation. Studies providing supporting health effects data (e.g. mechanistic, genotoxic, or toxicokinetic studies) were also compiled in HERO and annotated during the screening process.

2.2. Study evaluation

For each study selected for inclusion, the quality and informativeness of the evidence was rated by evaluating domains related to reporting quality, risk of bias, and sensitivity (see protocol Section 4; abbreviated version available in the key methods supplement). Evaluations first considered reporting quality, which refers to whether the study has reported sufficient details to conduct a risk of bias and sensitivity analysis; if a study does not report critical information (e.g. species, test article name) it may be excluded from further consideration. Risk of bias, sometimes referred to as internal validity, is the extent to which the design or conduct of a study may alter the ability to provide accurate (unbiased) evidence to support the relationship between exposure and effects (Higgins 2011). Sensitivity refers to the extent to which a study is likely to detect a true effect caused by exposure (Cooper et al. 2016; Higgins 2011).

All study evaluation ratings are documented and publicly available in EPA’s version of Health Assessment Workspace Collaborative (HAWC), a free and open source web-based software application (https://hawcprd.epa.gov/assessment/552/). Study evaluation was conducted in the following domains: reporting quality; allocation; observational bias/blinding; confounding; selective reporting and attrition; chemical administration and characterization; exposure timing, frequency and duration; endpoint sensitivity and specificity; and results presentation. For each domain, core questions and basic considerations provided guidance on how a reviewer might evaluate and judge a study for that domain (see Table 9 of the protocol or Table A of the key methods supplement).

At least two reviewers independently assessed each study, and any conflicts were resolved through discussion among reviewers or other technical experts. When information needed for the evaluation was missing from a key study, an attempt was made to contact the study authors for clarification. All communication with study authors was documented and is available in HERO (tagged as Personal Correspondence with Authors) and was annotated in HAWC whenever it was used to inform a study evaluation.

For each study, in each evaluation domain, reviewers reached a consensus on a rating of Good, Adequate, Deficient, or Critically Deficient. These individual ratings were then combined to reach an overall study confidence classification of High, Medium, Low, or Uninformative. The evaluation process was performed separately for each outcome reported in a study, as the utility of a study may vary for different outcomes.

2.3. Data extraction

Data from included studies were extracted into HAWC (https://hawcprd.epa.gov/assessment/552/). Dose levels are presented as mg/kg-day. For dietary exposure studies that reported dose levels as concentrations, dose conversions to mg/kg-day were made using US EPA default food or water consumption rates and body weights for the species/strain and sex of the animal of interest (US EPA 1988).

2.4. Evidence synthesis

For each outcome, the available evidence from the included animal studies was synthesized using a narrative approach, using the following considerations to articulate the strengths and weaknesses of the available evidence [adapted from (Hill 1965)]: consistency, biological gradient (dose–response), strength (effect magnitude) and precision, biological plausibility, and coherence. These considerations are defined in Table 10 of the protocol, and Table 11 of the protocol provides more information about how they were used to characterize the strength of evidence. When possible, an effort was made to evaluate the data according to the age and developmental stage of exposure to account for life stage-specific windows of susceptibility, as recommended by EPA’s Framework for Assessing Health Risk of Environmental Exposures to Children (US EPA 2006) and by Makris et al. (2008). When available, informative mechanistic data were used to augment the qualitative syntheses.

Based on this synthesis, each outcome was assigned a strength of evidence conclusion of Robust, Moderate, Slight, Indeterminate, or Compelling evidence of no effect (see definitions of these terms in Table 13 of the protocol or Table B of the key methods supplement). Robust and Moderate describe evidence that supports a hazard, differentiated by the quantity and quality of information available to rule out alternative explanations for the results (Robust describes an evidence base for which there is reasonable confidence that results are not due to chance, bias, or confounding; whereas Moderate describes an evidence base that has greater uncertainty, e.g. due to a smaller number of studies or some heterogeneity in results). Slight evidence includes situations in which there is some evidence that supports a hazard, but a conclusion of Moderate does not apply. Indeterminate describes a situation where the evidence is limited or inconsistent and cannot provide a basis for making a conclusion in either direction, or if the available studies are largely null but do not reach the level required to conclude there is compelling evidence of no effect. Compelling evidence of no effect represents a situation where extensive evidence across a range of populations and exposures identified no association between exposure and hazard. The ratings for individual outcomes were then summarized into an overall strength of evidence conclusion for each of the six hazards (male reproductive, female reproductive, developmental, liver, kidney, cancer). Rationales for strength of evidence conclusions are presented in evidence profile tables using a structured format based on the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach for evaluating certainty in the evidence (Guyatt et al. 2011; Schünemann et al. 2011).

3. Results

3.1. Study selection

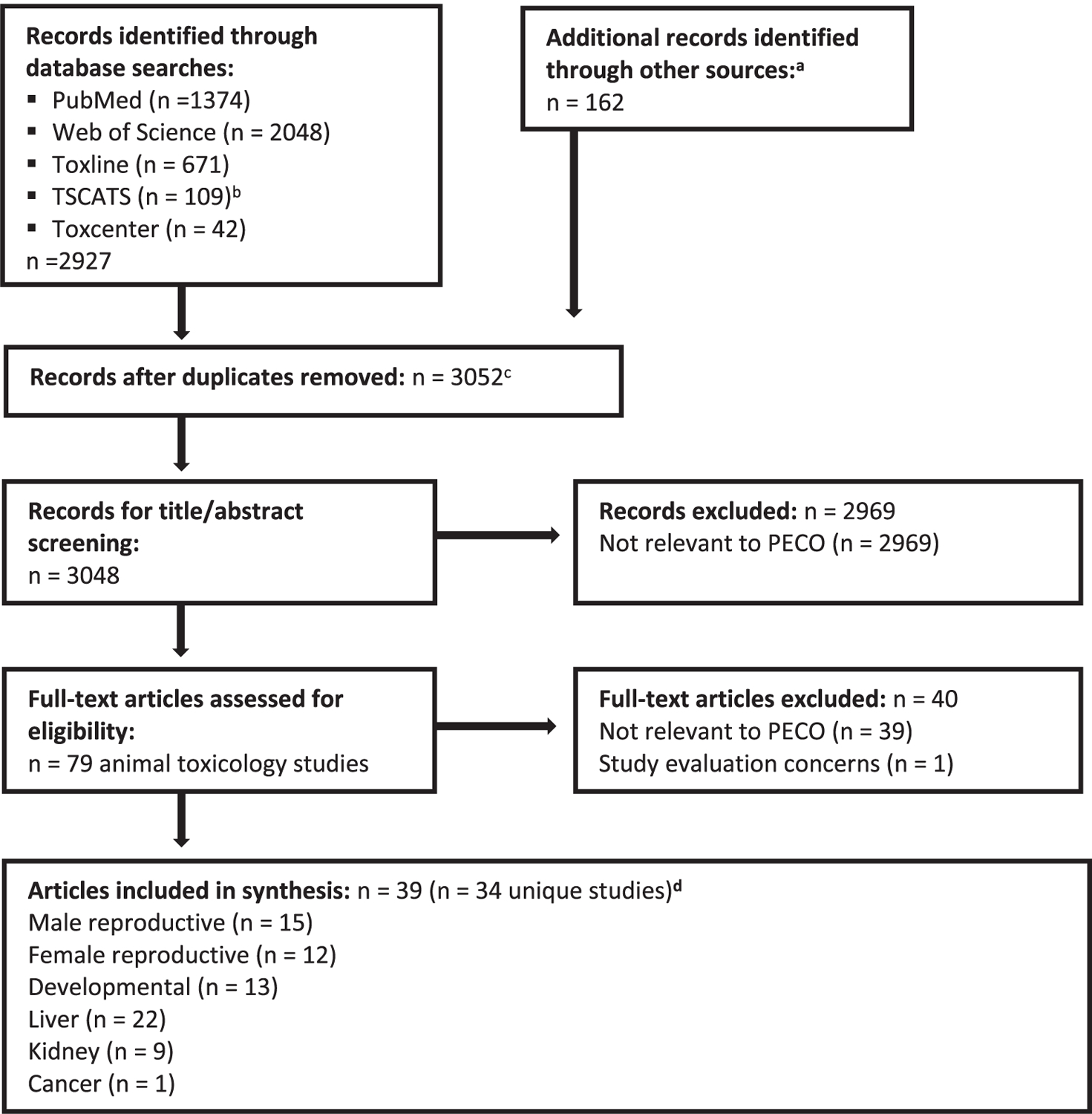

Literature search and screening results are summarized in Fig. 2. The literature search retrieved a total of 3,052 unique records for DEP, of which 79 were identified as animal health effect studies. Of the animal health effect studies, 39 were excluded for not meeting PECO criteria, e.g. skin and eye irritation studies and studies that used non-mammalian species. Three sets of the included studies were found to be multiple publications of the same data [Hazleton Laboratories America Inc (1983a, 1983b, 1992) and Hardin et al. (1987); Lamb et al. (1987) and RTI International (1984); and Field et al. (1993) and NTP (1988)] and were considered thereafter to be a single study [cited here as Hardin et al. (1987), RTI International (1984), and NTP (1988)]. At the study evaluation phase, one study was found to be uninformative due to critical deficiencies in the presentation of results and was excluded from further analysis (Hu et al. 2018). Therefore, a total of 34 studies were included this analysis (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Literature flow diagram (based on PRISMA flow diagram) for identifying DEP animal toxicology studies. aOther sources consisted of forward and backward searches, searching citations from key references, manual search of citations from key regulatory documents, and references that had been previously identified from an earlier DEP review effort. bIncludes records identified from TSCATS2, TSCATS1 (searched via Toxline), and TSCA section 8e recent notices identified via Google search, as described in the protocol. cIncludes 4 supplementary materials (not main text articles) that were tagged as records during the literature search. These supplementary materials were not included in the count of records for title/abstract screening. dMost studies reported data on multiple hazards; see Table 1.

Table 1.

List of studies and overall study confidence by outcome.a

| Male reproductiveb |

Female reproductivec |

Dev.d |

Liver |

Kidney |

||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author (year) | Species (strain) | Exposure life stage and duration | Exposure route | Testosterone | Morphological development | Sperm | Fertility | Organ weight | Histopathology | Pregnancy outcomes | Maternal body weight | Organ weight | Histopathology | Hormones | Estrous cyclicity | Morphological development | Survival | Growth | Structural alterations | Organ weight | Histopathology | Biochemistry | Tumors | Organ weight | Histopathology | Biochemistry |

| Fujii et al. (2005) | Rat [Crj:CD (SD)] | Multigenerational study; F0 and F1 each exposed for 10 weeks + mating, gestation, and weaning (∼15–17 weeks total) | Diet | H | H | H | H | H | M | H | M | H | M | – | H | H | H | H | – | H | M | H | – | H | M | – |

| RTI International (1984), Lamb et al. (1987) | Mouse (CD-1) | Multigenerational study (continuous breeding protocol) | Diet | – | – | H | H | H | – | H | – | H | – | – | – | – | H | H | – | H | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Pereira and Rao (2007) | Rat (Wistar) | Multigenerational study; F0 and F1 each exposed for 100 days + mating, gestation, and weaning (150 days total)]; F2 exposed for 150 days after weaning | Diet | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | L | – | L | L | L | – | – | – | – |

| Pereira et al. (2007c) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | L | L | L | – | – | – | – | |||

| Pereira et al. (2007d) | - | – | – | – | L | – | – | – | L | – | – | - | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |||

| Pereira et al. (2007a) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | L | L | L | – | – | – | – | |||

| Hardin et al. (1987), Hazleton Laboratories America Inc (1983a, 1983b, 1992) | Mouse (CD-1) | GD 6–13 | Gavage | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | M | – | – | – | – | – | H | H | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| NTP (1988), Field et al. (1993) | Rat (CD) | GD 6–15 | Diet | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | H | H | – | – | – | – | H | H | H | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Procter & Gamble (1994) | Rabbit (New Zealand White) | GD 6–18 | Dermal | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | L | H | H | – | – | – | H | H | H | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Howdeshell et al. (2008) | Rat (Sprague -Dawley) | GD 8–18 | Gavage | H | – | – | – | – | – | – | M | – | – | – | – | – | H | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Liu et al. (2005) | Rat (Sprague -Dawley) | GD 12–19 | Gavage | – | H | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Furr et al. (2014) | Rat (Sprague -Dawley) | GD 14–18 | Gavage | H | – | – | – | – | – | – | L | – | – | – | – | – | M | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Gray et al. (2000) | Rat (Sprague -Dawley) | GD 14 - PND 3 | Gavage | M | H | – | – | H | – | – | M | – | – | – | – | H | M | H | – | H | – | – | – | H | – | – |

| Setti Ahmed et al. (2018) | Rat (Wistar) | GD 8 – PND 30 | Gavage | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | L | L | L | L | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Manservisi et al. (2015) | Rat (Sprague -Dawley) | PND 1–181 (females) | Gavage | – | – | – | – | – | – | L | – | – | L | – | – | – | – | L | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Hu et al. (2016) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | L | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |||

| Mapuskar et al. (2007) | Mouse (Swiss) | 2–3 weeks old (females); 90- day exposure | Diet | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | L | L | L | – | – | – | – |

| Oishi and Hiraga (1980) | Rat (Wistar) | 5 weeks old (males); 7-day exposure | Diet | L | – | – | – | M | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | L | – | – | – | – | – | M | – | – |

| Kwack et al. (2009) * | Rat (Sprague -Dawley) | 5 weeks old (males); 28-day exposure | Gavage | – | – | H | – | L | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | H | – | H | – | H | – | H |

| Kwack et al. (2010) * | Rat (Sprague -Dawley) | 5 weeks old (males); 14-day exposure | Gavage | – | – | – | – | L | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | H | – | H | – | H | – | H |

| Brown et al. (1978) | Rat (CD) | Age not reported, but likely pre-pubertal, based on body weight (males and females); 42-day and 112-day exposures | Diet | – | – | – | – | L | L | – | – | L | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | M | L | – | – | M | L | M |

| NTP (1995) | Mouse (B6C3 F1), Rats (F344/N) | 6 weeks old (males and females); 28-day or 104–105- week exposure | Dermal | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | H | H | H | H | H | H | – |

| Pereira et al. (2006) | Rat (Wistar) | 6–7 weeks old (males); 150- day exposure | Diet | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | L | L | L | – | – | – | – |

| Sonde et al. (2000) | Rat (Sprague-Dawley) | 7 weeks old (males); 120-day exposure | Drinking water | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | L | – | L | – | – | – | – |

| Pereira and Rao (2006b) | Rat (Wistar) | 6–7 weeks old (females); 150- day exposure | Diet | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | L | – | – | – | – |

| Pereira and Rao (2006a) | Rat (Wistar) | 7–8 weeks old (males and females); 150-day exposure | Diet | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | L | L | L | – | – | – | – |

| Pereira et al. (2008a) | Rat (Wistar) | 7–8 weeks old (males); 150- day exposure | Diet | L | – | – | – | L | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Pereira et al. (2008b) | Rat (Wistar) | 7–8 weeks old (males); 150- day exposure | Diet | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | L | L | L | – | – | – | – |

| Jones et al. (1993) | Rat (Wistar) | 6–8 weeks old (males); 2-day exposure | Gavage | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Moody and Reddy (1978) | Rat (F334) | Age not reported (males); 21- day exposure | Diet | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | M | M | M | – | – | – | – |

| Moody and Reddy (1982) | Rat (F334) | Age not reported (males); 21- day exposure | Diet | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | M | – | – | – | – |

| Shiraishi et al. (2006) | Rat (Sprague-Dawley | 8 weeks old (males and females); 28-day exposure | Gavage | H | – | M | – | L | M | – | – | H | M | H | L | – | – | – | – | – | M | M | – | H | M | – |

| Mondal et al. (2019) | Mice (Swiss abino) | 8 weeks old (males); 90-day exposure | Diet | M | – | M | – | – | L | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Sinkar and Rao (2007) | Rat (Wistar) | 12 weeks old (males and females); 180-day exposure | Drinking water | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | L | L | – | – | – | – |

Kwack et al. (2009 and 2010) tested both DEP and MEP. The remaining studies tested DEP.

High confidence (H), Medium confidence (M), Low confidence (L). Dash (–) indicates endpoints that were not included in a study.

Male reproductive endpoints: Testosterone (testicular production or level measured in testis or serum), morphological development (AGD, nipple retention, time to puberty), sperm (sperm counts, motility, morphology), fertility (copulation and ability to produce offspring), organ weights (testis, epididymides, prostate, seminal vesicles), histopathology (general histopathological evaluations of male reproductive organs).

Female reproductive endpoints: Pregnancy outcomes (copulation, litter size, gestation length), maternal body weight (body weight gain during gestation or lactation), organ weight (uterus, vagina, ovary), histopathology (general histopathological evaluations of female reproductive organs), hormones (any measurement of reproductive hormones), estrous cyclicity, morphological development (AGD, time to puberty).

Developmental endpoints: Survival (fetal viability, fetal mortality, resorptions, pre- or post-implantation loss, postnatal survival), growth (pre- or postnatal body weight), structural alterations (external, skeletal, or visceral malformations or variations).

3.2. Summary of included studies

The included studies are summarized in Table 1. The database of DEP studies is diverse and consists of multigenerational studies, gestational exposure studies, and studies in peripubertal or adult animals. All studies were either oral or dermal exposures conducted in rats, rabbits or mice. Kwack et al. (2009) and Kwack et al. (2010) exposed animals to either DEP or MEP, and all other studies used DEP.

Eight studies assessed multigenerational effects of DEP exposure. Of these, reproductive and developmental effects were evaluated in the continuous breeding study in mice by RTI International (1984) and in the two-generation reproduction study in rats by Fujii et al. (2005), which exposed animals beginning prior to the mating of F0 parental animals and continuing through the weaning of F2 offspring. Four multigenerational studies report data from the same group of animals exposed to a low dose of DEP (approximately 2.85 mg/kg-day) from the F0 to F2 generations, focusing on either hepatic toxicity (Pereira et al., 2007a, 2007c; Pereira and Rao, 2007) or reproductive toxicity (Pereira et al., 2007b). The remaining two multigenerational studies (Hu et al. 2016; Manservisi et al. 2015) exposed F1 female rats to a low dose (0.173 mg/kg-day) of DEP beginning at postnatal day (PND) 1 via lactation, and continuing through PND 181 via oral gavage; Manservisi et al. (2015) reported on mammary gland effects and fertility in F1 females and growth and survival of F2 offspring, and Hu et al. (2016) reported body weight data for a subset of these same F1 female rats at PNDs 62 and 181.

Effects in developing animals were also evaluated in studies that exposed animals during gestation and/or early postnatal life. Of these, the studies by Gray et al. (2000), Howdeshell et al. (2008), Furr et al. (2014), and Liu et al. (2005) exposed rats during late gestation [gestation day (GD) 14 – PND 3, GD 8–18, GD 14 – 18, and GD 12–19, respectively] and focused on male reproductive development and phthalate syndrome effects. These exposures coincide with the critical window of male sexual differentiation (~GD 14–18), which is known to be the sensitive window of exposure for the induction of phthalate syndrome. Hardin et al. (1987) evaluated fetal survival and growth in mice exposed to a single high dose of DEP from gestation day (GD) 6–13. NTP (1988) and Procter & Gamble (1994) evaluated fetal survival, growth, and structural alterations in rats and rabbits following exposure from GD 6–15 and 6–18, respectively. Setti Ahmed et al. (2018) evaluated intestinal morphology and organ weight changes in rats exposed from GD 8 – PND 30. Most of these developmental exposure studies also provided relevant data on maternal reproductive endpoints (e.g. maternal body weight gain, pregnancy outcomes) in addition to effects on the developing animals.

The remaining studies evaluated rats or mice following peripubertal or adult exposure. Oishi and Hiraga (1980), Mondal et al. (2019), and Jones et al. (1993) focused on male reproductive effects (testosterone, sperm parameters, and/or testicular histology), and Shiraishi et al. (2006) evaluated reproductive effects in both male and female rats including hormone levels, sperm parameters, and estrous cyclicity. Kwack et al. (2010) and Kwack et al. (2009) evaluated general toxicity (organ weights, serum biochemistry, urinalysis) in DEP- and MEP-exposed rats, with a sperm evaluation also conducted in Kwack et al. (2009). A two-year dermal exposure study in rats and mice by NTP (1995) provided information on tumor incidence. Other studies focused on general toxicity and hepatic effects, including organ weight, histopathology, and biochemical changes. This includes a series of low dose studies in rats or mice performed by the same laboratory (Mapuskar et al., 2007; Pereira et al., 2006, 2008a, 2008b, Pereira and Rao, 2006a, 2006b, 2007; Sinkar and Rao, 2007; Sonde et al., 2000), as well as the studies in rats by Moody and Reddy (1978), Moody and Reddy (1982), and Brown et al. (1978).

3.3. Study evaluation

Overall study confidence classifications by outcome are summarized in Table 1, and heat maps summarizing study evaluation ratings by domain are provided in the Supplementary Materials (Fig. S1). Fig. S1 provides links to an interactive figure in HAWC, where rationale for the study evaluation ratings is documented.

Based on the study evaluation considerations outlined in the systematic review protocol, confidence was reduced in some studies that had incomplete reporting of experimental designs or results. For example, dose-related histopathological findings were frequently reported qualitatively, with no quantitative data provided on the incidence or severity of lesions; such outcomes were considered low confidence. Additionally, some study outcomes were rated medium or low confidence due to sensitivity concerns with certain endpoint measurements. For instance, for evaluation of maternal body weight gain, rabbits were not considered an appropriate test species since body weight changes in rabbits are more variable compared to other species (US EPA 1991); and, for all species, confidence was reduced in the maternal body weight gain measurements in studies that did not adjust for gravid uterine weight, which facilitates the interpretation of maternal toxicity relative to effects on fetal body weight (US EPA 1991). For organ weights, it was considered best practice for studies to report both absolute and relative (adjusted to body weight) measurements, although relative organ weight as a standalone measurement was generally considered to be acceptable for most organs (Bailey et al. 2004). For testis, however, studies only reporting relative organ weight were considered low confidence, since testis weight is not proportionate to body weight (Bailey et al. 2004).

Specific concerns were raised regarding studies from two laboratory groups that tested relatively low doses of DEP; these include concerns about exposure characterization as well as other concerns for risk of bias and sensitivity. The studies by Manservisi et al. (2015) and Hu et al. (2016), both of which reported data on the same group of animals, dosed rats with 0.173 mg/kg-day three times per week from birth through PND 181 and stated via personal correspondence that they verified the concentration of DEP in the dosing solutions but did not evaluate background levels of DEP that may be present due to the use of phthalate in plastics or other environmental sources. This is potentially problematic because a separate dose range-finding study by these authors (Teitelbaum et al. 2016) reported elevated levels of MEP in the urine of control animals, which suggests the potential for background exposures or contamination that could significantly impact the nominal dose levels. A series of studies by another laboratory exposed rats or mice to low doses of DEP in diet (0.57–6.25 mg/kg-day) (Mapuskar et al., 2007; Pereira et al., 2006, 2007a, 2007b, 2007c, 2008a, 2008b, Pereira and Rao, 2006a, 2006b, 2007) or to 50 ppm DEP in drinking water (Sinkar and Rao 2007; Sonde et al. 2000) without verifying the nominal doses. Again, concerns were raised that undetected background levels of phthalates in control groups could mask true effects and reduce study sensitivity. Moreover, several of these studies by Pereira and coauthors stated that the concentration of DEP in the diet was increased on a weekly basis to maintain the dose in proportion with the animals’ body weight but did not provide additional information on this dose adjustment, which raises separate questions about the accuracy of the nominal doses in these studies. Studies by these two laboratory groups also had other concerns raised during study evaluation; for instance, data from littermates were presented as the average of individual pups, which has the potential to overestimate the statistical significance of experimental findings (Haseman et al. 2001). Most of these studies also described histopathological changes in the exposed animals without providing quantitative data to support their findings. Overall, due to these cumulative concerns, these studies were rated as low confidence for all reported outcomes.

3.4. Male reproductive effects

Male reproductive effects were evaluated according to the life stage of exposure (US EPA 2006). Figs. indicating the doses at which statistically significant male reproductive effects occurred are provided in Supplemental Materials (Figs. S2–S4).

3.4.1. Summary of gestational and early postnatal exposure studies (including F1 or F2 offspring from multigenerational studies)

Three high or medium confidence studies investigated effects on testosterone production or levels in male rats following gestational exposure (Furr et al. 2014; Howdeshell et al. 2008) or exposure from gestation through PND 3 (Gray et al. 2000). These studies all used exposure periods that included the critical window of male sexual differentiation in late gestation (which occurs between ~ GD 14–18), and therefore are considered relevant for the evaluation of fetal testosterone production and other phthalate syndrome effects. No statistically significant effects on fetal testicular testosterone production were observed at GD 18 following exposure from GD 14–18 (Furr et al. 2014) or GD 8–18 (Howdeshell et al. 2008) at doses up to 750 and 900 mg/kg-day, respectively. Likewise, there was no statistically significant effect on serum testosterone levels in adult male rats that had been exposed to 750 mg/kg-day DEP from GD 14 – PND 3 (Gray et al. 2000). Additional supporting mechanistic evidence was provided by Liu et al. (2005), who did not report testosterone production but evaluated global gene expression in the fetal rat testis after exposure to 500 mg/kg-day from GD 12–19; gene expression in DEP-treated animals was similar to controls, whereas known antiandrogenic phthalates (e.g. dibutyl phthalate, diethylhexyl phthalate) downregulated expression of genes involved in cholesterol homeostasis and steroidogenesis (Liu et al. 2005). A follow-up study by Clewell et al. (2010) evaluated testicular MEP levels in a subset of male fetuses from the study by Liu et al. (2005) and found MEP present at relatively high levels, indicating that the lack of effect of DEP in the study by Liu et al. (2005) was not due to the dose not reaching the testis. Taken together, these studies consistently suggest lack of effect on fetal testosterone production. Rats have been found to be more sensitive to the anti-androgenic effects of phthalates compared to mice (Johnson et al. 2012), so the lack of effects in rats strengthens the evidence that DEP does not affect fetal testosterone production; however, additional evidence (e.g. studies in other species besides rat) would be needed to have confidence in a conclusion of compelling evidence of no effect. The evidence for effects on testosterone levels after gestational exposure was therefore considered indeterminate.

Male reproductive organ weights and other biomarkers of androgen-dependent reproductive development were evaluated in F1 peripubertal and adult rats after exposure from GD 14 – PND 3 (Gray et al. 2000) and in F1 and F2 weanling rats in the two-generation reproduction study (Fujii et al. 2005). Additionally, AGD was evaluated in fetal rats after exposure from GD 12–19 (Liu et al. 2005). All of these studies were judged to be high confidence for these outcomes. There were no statistically significant effects on male reproductive organ weights (Fujii et al. 2005; Gray et al. 2000), with the exception of a 20% decrease in absolute prostate weights and 17% increase in relative seminal vesical weight observed in F1 weanlings exposed to 1016 mg/kg-day DEP (Fujii et al. 2005). Prostate and seminal vesicle weights were not affected in F2 weanlings from the same study (Fujii et al. 2005). There were no effects on AGD (Fujii et al. 2005; Gray et al. 2000; Liu et al. 2005) or nipple retention (Gray et al. 2000), both of which are biomarkers of androgen-dependent reproductive development. Gestational exposure to DEP did not affect the timing of sexual maturation, as measured by the age at onset of preputial separation (Fujii et al. 2005; Gray et al. 2000). The lack of effect on these outcomes is consistent with the observation that DEP does not affect testosterone in rats exposed during gestation. However, since a larger body of evidence would be needed to conclude there was compelling evidence of no effect, the evidence for effects on male reproductive organ weights and morphological development were both considered indeterminate.

3.4.2. Summary of peripubertal and adult exposure studies (including F0 or F1 parental animals from multigenerational studies)

In contrast with results observed after gestational exposure, several studies reported decreased testosterone levels following peripubertal or adult exposure to DEP in male rats. In a high confidence two-generation reproduction study, Fujii et al. (2005) observed decreased serum testosterone in F0 males following 14 weeks of exposure in all dose groups, reaching statistical significance in the two highest dose groups (197 and 1016 mg/kg-day); however, this evaluation was performed on a relatively small subset of the animals (n = 6/group) and results showed a large amount of variability with a nonmonotonic magnitude of change (decreased by 80% in the 197 mg/kg-day group and 50% in the 1016 mg/kg-day group). This study did not evaluate hormone levels in F1 animals, so it is not clear whether this effect was present across other generations; however, it is notable that there was minimal or no effect in these animals on male reproductive organ weights (discussed below), which are known to be sensitive to changes in androgen levels (US EPA 1996). Dose-related statistically significant decreases in serum testosterone and androstenedione were also observed in adult male rats exposed to 0.57 mg/kg-day to 2.85 mg/kg-day DEP for 150 days in the study by Pereira et al. (2008a), which is considered low confidence for this outcome due to the study design concerns described in Section 3.3. In addition, serum and testicular testosterone levels were statistically significantly decreased in young rats exposed to DEP for 7 days (Oishi and Hiraga 1980), although this data was presented as a percentage of control without a measure of variance and is considered low confidence. In contrast to other findings, no effect on serum testosterone or gonadotropin levels was observed in a high confidence study in Wistar rats following exposures up to 1000 mg/kg-day DEP for 28 days (Shiraishi et al. 2006), although those authors did observe a statistically significant decrease in serum estradiol for males in the 1000 mg/kg-day dose group. No effects on serum testosterone were observed in a medium confidence study in Swiss albino mice following exposures up to 10 mg/kg-day in diet for 3 months (Mondal et al. 2019). Additionally, mechanistic evidence to support a lack of effect on testicular steroidogenesis was available in the study in rats by Foster et al. (1983), which found that peripubertal exposure to ~ 1600 mg/kg-day DEP for up to 4 days did not affect the activity of testicular steroidogenic enzymes, whereas exposure to a known antiandrogenic phthalate (dipentyl phthalate) decreased the enzyme activity in a time-dependent manner; and Jones et al. (1993) reported that MEP did not decrease testosterone production in an in vitro culture of rat Leydig cells. Overall, although decreased testosterone was observed in three studies, two of these studies had significant concerns for bias and the results are not supported by mechanistic evidence or other coherent effects (e.g. effects on testis weight) in the high confidence study by Fujii et al. (2005). The evidence for effects on testosterone after peripubertal or adult exposure was considered slight.

Four high or medium confidence studies that evaluated sperm parameters in rats or mice found statistically significant effects on sperm count, motility, or morphology following multigenerational exposure to DEP (Fujii et al. 2005; RTI International 1984), peripubertal exposure to DEP or MEP (Kwack et al. 2009), or adult exposure to DEP (Mondal et al. 2019). The high confidence study by Fujii et al. (2005) observed a statistically significant increase in abnormal or tailless sperm in both F0 and F1 rats, although the magnitude of effect was low (abnormal sperm rate was 1.52% in F1 animals in the 1150 mg/kg-day group versus 0.6% in control animals) and effects in F0 animals were nonmonotonic (occurring at 197 mg/kg-day group but not 1016 mg/kg-day). Sperm counts and motility were not affected in this study. The high confidence study by Kwack et al. (2009) observed that epididymal sperm count and percent motility were statistically significantly decreased in rats following exposure to 250 mg/kg-day MEP for four weeks, while percent linearity was statistically significantly decreased at 500 mg/kg-day DEP, with no effects on other sperm parameters. The high confidence study by RTI International (1984) reported that epididymal sperm counts were statistically significantly decreased in F1 mice dosed with 3640 mg/kg-day, with no effects on percent motility, abnormal sperm, or tailless sperm. The medium confidence study by Mondal et al. (2019) reported a statistically significant decrease in epididymal sperm count, motility, and viability and increased sperm morphological abnormalities in adult mice dosed with 1 or 10 mg/kg-day for three months, and provided supporting mechanistic evidence demonstrating oxidative stress in germ cells and apoptosis in testicular sections. Conversely, the medium confidence study by Shiraishi et al. (2006) reported no effects on epididymal sperm counts or morphology in adult rats following 28-day DEP exposure at doses up to 1000 mg/kg-day, although the authors provided no quantitative data. Although effects varied across studies, alterations in sperm quality were observed across most studies including three considered high confidence, and therefore the evidence for effects on sperm parameters is considered moderate.

No effects on copulation or fertility in F0 or F1 mating pairs were observed in two multigenerational studies that are considered high confidence for this endpoint (Fujii et al. 2005; RTI International 1984). Since only two studies were available, the evidence for effects on male fertility is considered indeterminate.

Reproductive organ weights in males following adult exposure to DEP were measured in several studies. In high confidence studies that reported absolute organ weights, DEP generally did not affect testosterone-dependent male reproductive organ weights (e.g., testes, epididymides, prostate, seminal vesicles) in F0 and F1 parental rats and mice (Fujii et al. 2005; RTI International 1984), although Fujii et al. (2005) reported a slight (5%) but statistically significant decrease in epididymal weights in F0 males at 1016 mg/kg-day. The medium confidence study by Oishi and Hiraga (1980) found no effect on absolute or relative testis weight in young rats exposed to DEP for 7 days. In low confidence studies, effects were inconsistent. The multigenerational study in rats by Pereira et al. (2007d) reported statistically significantly decreased absolute testis weights in F0 parental males but not adult F1 males exposed to 2.85 mg/kg-day in diet, and Pereira et al. (2008a) reported a statistically significant dose-related decrease in absolute testis and epididymis weights in adult male rats after exposure to 0.57 to 2.85 mg/kg-day. Brown et al. (1978) reported a statistically significant increase in relative testis weights in rats after 2, 6, or 16 weeks of exposure to 3160 mg/kg-day; however, it is possible that this is an artifact of decreased body weight in these animals, since testis and body weights are not proportional (Bailey et al. 2004). In other studies that did not observe significant effects on body weight, relative testis weights were not affected by DEP (Kwack et al. 2009; Kwack et al. 2010; Shiraishi et al. 2006). Given that absolute organ weights were largely unaffected in high confidence studies in rats and mice, the evidence for effects on male reproductive organ weights is considered indeterminate.

In addition, five studies performed histopathological evaluations of male reproductive organs. The low confidence study by Mondal et al. (2019) reported altered testicular histoarchitecture (azoospermia, loss of tubular compactness and increased vacuolization, thinning of basement membrane), which is coherent with effects on epididymal sperm in this study. The medium confidence study by Jones et al. (1993) reported no changes in seminiferous tubular structure or Leydig cell morphology in rats exposed to 2000 mg/kg-day for two days, although there were effects on Leydig cell cytoplasmic ultrastructure (mitochondrial swelling, focal dilation and vesiculation of the smooth endoplasmic reticulum). The three remaining medium or low confidence studies did not observe any treatment-related effects (Brown et al. 1978; Fujii et al. 2005; Shiraishi et al. 2006). None of these studies provided quantitative data to support their observations. Given this limited and inconsistent dataset, the evidence for histopathological effects in male reproductive organs is considered indeterminant.

3.4.3. Synthesis of results for male reproductive effects

Overall, the available studies suggest that there is moderate evidence that DEP is a male reproductive toxicant (Table 2). Decreased sperm quantity or quality was observed across almost all studies that evaluated sperm parameters, although the magnitude of effect was low in some cases and there was variation in the parameters affected across studies. The observed effects on sperm are nevertheless compelling because similar effects have been reported for other phthalates, and are thought to result from direct targeting of Sertoli cells that occurs via an androgen-independent mode of action (Johnson et al. 2012; National Research Council 2008). It is plausible that DEP may operate through a similar mechanism, leading to effects on sperm in absence of an effect on steroidogenesis. It is also possible that this reproductive toxicity is mediated by an androgen-dependent mechanism, given that decreased testosterone was also observed in three peripubertal or adult exposure studies; however, there is less confidence in the finding that DEP exposure may affect hormone levels. Gestational exposure studies did not show effects of DEP on testosterone production, biomarkers of male reproductive development, sexual maturation, or (to any great extent) male reproductive organ weights.

Table 2.

Evidence profile table for male reproductive effects of DEP or MEP.

| Male reproductive

effects | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Available Studies | Factors that increase confidence | Factors that decrease confidence | Confidence judgement for outcome | Confidence judgement for overall hazard | |

| Gestational or postnatal exposure (including F1 and F2 offspring from multigenerational studies | Testosterone |

High Confidence: Howdeshell et al. (2008), Furr et al. (2014)

Medium Confidence: Gray et al. (2000) |

• Consistency Lack of effect in

sensitive species (rat) • Minimal concern for bias and sensitivity |

• Few studies | ◯◯◯ INDETERMINATE There were no effects on fetal testosterone production at GD 18 (Howdeshell et al. 2008, Furr et al. 2014) or serum testosterone levels at PND 3 (Gray et al. 2000) following gestational exposure. |

⊕⊕◯ MODERATE Based on moderate evidence for adverse effects on sperm and decreased testosterone in peripubertal or adult exposure studies. |

| Male morphological development | High Confidence: Fujii et al. (2005), Gray et al. (2000), Liu et al. (2005) | • Consistency • Minimal concern for bias and sensitivity |

• Few studies | ◯◯◯ INDETERMINATE There were no effects on nipple retention or AGD (Gray et al. 2000, Liu et al. 2005) or on the age of preputial separation (Fujii et al. 2005, Gray et al. 2000) following gestational exposure. |

||

| Reproductive organ weights | High Confidence: Fujii et al. (2005), Gray et al. (2000) | • Consistency • Minimal concern for bias and sensitivity |

• Few studies | ◯◯◯ INDETERMINATE There were no effects on male reproductive organ weights following gestational exposure, except for a decrease in absolute prostate weight and increase in relative seminal vesicle weight in F1 weanlings (Fujii et al. 2005). |

||

| Peripubertal or adult exposure (including F0 and F1 parental animals from multigenerational studies) | Testosterone |

High Confidence:

Fujii et al. (2005), Shiraishi et al. (2006)

Medium Confidence: Mondal et al. (2019) Low Confidence: Oishi and Hiraga (1980), Pereira et al. (2008a) |

• Consistency in the direction of effect across three studies | • Low precision in the high confidence

study by Fujii et al. 2005

• Concerns for bias and sensitivity • Mechanistic evidence indicating lack of effect on steroidogenesis |

⊕◯◯

SLIGHT Significantly decreased testosterone was observed in rats exposed as adults/young adults in the studies by Fujii et al. 2005, Pereira et al. (2008a), and Oishi and Hiraga 1980, although Fujii et al. 2005 tested a relatively small sample size and had high variability, and the latter two studies are considered low confidence for this outcome. No effects on testosterone were observed in adult male rats after a 28-day exposure (Shiraishi et al. 2006) or in mice after a 3-month exposure (Mondal et al. 2019). |

|

| Sperm |

High Confidence:

Fujii et al. (2005), RTI International (1984), Kwack et al. (2009)

Medium Confidence: Shiraishi et al. (2006), Mondal et al. (2019) |

• Minimal concern for bias and

sensitivity • Biological plausibility (mechanistic evidence of oxidative stress in germ cells) |

• Unexplained inconsistency | ⊕⊕◯ MODERATE Decreased sperm number, increased incidence of abnormal sperm, and/or decreased sperm motility were observed in multiple studies that exposed adult rats or mice (Fujii et al. 2005, Kwack et al. 2009, RTI International 1984, Mondal et al. 2019), although effects differed somewhat between studies and were not consistently observed. Shiraishi et al. 2006 used a similar study design as Kwack et al. 2009 but did not observe any effects. |

||

| Fertility | High Confidence: Fujii et al. (2005), RTI International (1984) | • Consistency • Minimal concern for bias and sensitivity |

• Few studies | ◯◯◯ INDETERMINATE No effects on fertility in mating pairs were observed in two multigenerational reproductive studies. |

||

| Reproductive organ weights |

High Confidence:

RTI International (1984), Fujii et al. (2005)

Medium Confidence: Oishi and Hiraga (1980) Low Confidence: Brown et al. (1978), Kwack et al. (2009, 2010), Pereira et al. (2007d, 2008a), Shiraishi et al. (2006) |

• Unexplained

inconsistency • Concerns for bias and sensitivity |

◯◯◯ INDETERMINATE Absolute organ weights (testes, epididymides, prostate, seminal vesicles) were generally not affected in high or medium confidence studies in mice and rats. Effects on relative testis weight were inconsistent across the remaining low confidence studies, although this is considered a less reliable measurement compared to absolute testis weight. |

|||

| Histopathology |

Medium Confidence:

Fujii et al. (2005), Shiraishi et al. (2006), Jones et al. (1993)

Low Confidence: Mondal et al. (2019), Brown et al. (1978) |

• Coherent with effects on sperm | • Unexplained

inconsistency • Concerns for bias and sensitivity • Quantitative data not reported in any study |

◯◯◯ INDETERMINATE Altered testicular histoarchitecture (Mondal et al. 2019) and altered Leydig cell cytoplasmic ultrastructure (Jones et al., 1993) were reported, but no effects on histopathology of male reproductive organs was observed in three other studies. |

||

Despite the effects on sperm parameters, there is no evidence that fertility was affected in the two-generation study by Fujii et al. (2005) or the continuous breeding study by RTI International (1984). However, it has been demonstrated that rodents can remain fertile even after dramatic reductions in sperm counts, whereas a relatively small change in sperm count may impact human fertility (Mangelsdorf et al. 2003; Sharpe 2010). Therefore, the findings of decreased sperm quality in animal models is of potential relevance for human health risk assessment.

Strengths of this evidence base include the availability of several high confidence gestational exposure studies, with two large multigenerational studies that assessed multiple outcomes in postnatal and adult animals (Fujii et al. 2005; RTI International 1984). Other strengths are the availability of studies in both rats and mice that assessed similar outcomes, although the majority of evidence was from studies in rats.

3.5. Female reproductive effects

Figs. indicating the doses at which statistically significant female reproductive effects occurred are provided in the Supplementary Materials (Figs. S5–S7 and S18).

3.5.1. . Summary of available studies

Effects on pregnancy outcomes (including mating, fertility, fecundity, and gestation length) were evaluated in two high confidence studies following continuous DEP exposure across multiple generations in rats (Fujii et al. 2005) and mice (RTI International 1984), and in one low confidence study that evaluated effects in F1 female rats that had been exposed to a low dose of DEP (0.173 mg/kg-day) since birth (Manservisi et al. 2015). In the two-generation study in rats, Fujii et al. (2005) observed that F1 parental females had a slight but statistically significant decrease in gestation length after exposure to 1375 mg/kg-day DEP. This effect was not observed in F0 parental females, and there were no effects on copulation, fertility, or litter size in either generation. In the continuous breeding study in mice (RTI International 1984), litter size was statistically significantly reduced by 14% in F1 parental females following exposure to 3640 mg/kg-day. There were no effects on litter size or number of litters per mating pair for F0 parental females, and no effect on fertility (number fertile per number cohabited) in either F0 or F1 animals. Manservisi et al. (2015) found that pregnancy rate was not affected, and that litter size was statistically significantly increased in DEP-treated females compared to controls, although the finding for litter size is considered low confidence due to the concerns described in Section 3.3. Given that some effects on litter size and gestation length in F1 parental females were observed in two high confidence studies, the evidence for effects on pregnancy outcomes was considered slight.

Maternal body weight parameters were assessed in the two-generation study in rats by Fujii et al. (2005) and in several studies that exposed animals during gestation only. In rats exposed to DEP from GD 6–15, NTP (1988) reported a decreasing trend in maternal body weight gain after correcting for gravid uterine weight, indicating that the effect was maternal rather than fetal. In contrast, the multigenerational exposure study by Fujii et al. (2005) reported a statistically significant increase in F0 maternal body weight gain in several dose groups, but no effects on maternal weight gain in the F1 generation. No effects on maternal weight gain were observed in the remaining studies in mice (Hardin et al. 1987), rats (Furr et al. 2014; Gray et al. 2000; Howdeshell et al. 2008), or rabbits (Procter & Gamble 1994), although the latter study should be interpreted with additional caution, since maternal body weight during pregnancy can be highly variable in rabbits (US EPA 1991). Taken together, DEP may affect maternal weight gain at high doses in the rat, but effects were inconsistent, possibly due to interspecies sensitivity differences or differences in experimental design. Therefore, the evidence for effects on maternal body weight gain are considered indeterminate.

Multiple studies evaluated organ weights in females that had been exposed to DEP during development or as adults. No DEP-related effects were reported for gravid uterine weights in adult pregnant rats or rabbits (NTP 1988; Procter & Gamble 1994) or absolute or relative uterine or ovarian weights in adult rats (Brown et al. 1978; Shiraishi et al. 2006), F0 or F1 adult rats (Fujii et al. 2005), or F1 adult mice (RTI International 1984). In contrast, absolute uterine weights were statistically significantly reduced in F1 and F2 weanling female rats after gestational exposure to 1297 mg/kg-day and 1375 mg/kg-day, respectively, although this effect appears to be transient, since effects on uterine weight were not observed in adult F1 females at necropsy (Fujii et al. 2005). Statistically significant increases in relative ovary weights in F0 and F1 female rats following exposure to 2.85 mg/kg-day and 1.425 mg/kg-day, respectively, were reported in the multigenerational study by Pereira et al. (2007d), although this study is considered low confidence due to the concerns discussed in Section 3.3. Taken together, while there is some evidence for effects on various organ weights from both high and low confidence studies, most studies do not support that DEP induces permanent, adverse effects. The evidence for effects on female reproductive organ weight is considered slight.

In a histopathological evaluation, the low confidence study by Manservisi et al. (2015) reported mammary gland effects (decreases in the size of lobular structures and a darker and denser appearance of these structures due to the lower dilation of the secretory alveoli) in parous F1 females that had been exposed to 0.173 mg/kg-day DEP since birth, although the sample size was small (n = 3/group) and only semi-quantitative results were presented; corresponding effects in nulliparous females after lactational and direct DEP exposure were not observed. Other high or medium confidence studies that evaluated gross and histopathological alterations in ovaries, uteri, vaginas, or mammary glands did not observe DEP-induced effects (Fujii et al. 2005; Procter & Gamble 1994; Shiraishi et al. 2006). Since effects were only observed in one low confidence study, the evidence for histopathological effects on female reproductive organs is considered indeterminate.

In adolescent F1 female rats exposed to DEP at 1375 mg/kg-day, the onset of puberty as measured by the age at vaginal opening was delayed by 6% compared to control (Fujii et al. 2005). Animals in this dose group had decreased growth in early postnatal life but had reached similar body weights compared to controls at the time puberty was attained, which suggests that the delay in puberty was related to delayed growth. AGD in F1 or F2 female pups was not affected in this study (Fujii et al. 2005) or in F1 females in the study by Gray et al. (2000). There were no effects on estrous cyclicity in F0 or F1 females (Fujii et al. 2005). Likewise, Shiraishi et al. (2006) evaluated serum hormone levels in adult female rats exposed to DEP for 28 days and found no effects on estradiol, testosterone, or gonadotropins. Shiraishi et al. (2006) also reported no abnormalities in estrous cycles measured during the last week of the 28-day exposure period, but this outcome was considered low confidence due to a short observation duration and lack of quantitative data. Taken together, evidence for effects on female morphological development, estrous cyclicity, and hormones were all considered to be indeterminate.

3.5.2. Synthesis of results for female reproductive effects

The available studies suggest there is slight evidence that DEP is a female reproductive toxicant (Table 3). Some statistically significant effects were reported for decreased gestation length, decreased litter size, maternal body weight gain, organ weight changes, and age at puberty from two high confidence multi-generational studies in rats and mice. Effects on gestation length (Fujii et al. 2005) and litter size (RTI International 1984) in these studies were observed in F1 parental animals but not in F0, possibly suggesting that the F1 animals may have increased sensitivity due to their developmental exposure to DEP; however, in all cases, the magnitude of effect was small and was observed only at high dose levels. Otherwise, except for some organ weight and histopathological changes in low confidence studies, results across studies were largely negative. It is possible that differences in test animal species/strains and experimental designs may contribute to some of these inconsistencies across studies.

Table 3.

Evidence profile table for female reproductive effects of DEP.

| Female reproductive

effects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Available studies | Factors that increase confidence | Factors that decrease confidence | Confidence judgement for outcome | Confidence judgement for overall hazard |

| Pregnancy outcomes |

High Confidence:

Fujii et al. (2005), RTI International (1984)

Low Confidence: Manservisi et al. (2015) |

• Minimal concern for bias and sensitivity in most studies | • Few studies • Small magnitude of effect in high confidence studies |

⊕◯◯ SLIGHT Statistically significantly decreased gestation length (Fujii et al. 2005) and decreased litter size (RTI International 1984) were observed in F1 parental females in two high confidence studies, and increased litter size was observed in one low confidence study (Manservisi et al. 2015). Otherwise, no effects were observed. |

⊕◯◯ SLIGHT Based on few reported effects across studies, including effects on gestation length, litter size, and organ weights or histopathology. |

| Maternal body weight |

High Confidence:

NTP

(1988) Medium Confidence: Howdeshell et al. (2008), Hardin et al. (1987), Gray et al. (2000), Fujii et al. (2005) Low Confidence: Furr et al. (2014), Procter & Gamble (1994) |

• Minimal concerns for bias and sensitivity in two studies that observed effects | • Unexplained inconsistency | ◯◯◯

INDETERMINATE NTP (1988) reported a trend towards decreased maternal body weight gain (corrected for gravid uterine weight), whereas Fujii et al. (2005) reported increased maternal body weight gain in F0 females. Otherwise, no effects on maternal body weight gain were observed in rats, mice, or rabbits. |

|

| Reproductive organ weights |

High Confidence:

Fujii et al. (2005), RTI International (1984), Procter & Gamble (1994), NTP (1988), Shiraishi et al.

(2006) Low Confidence: Brown et al., 1978; Pereira et al., 2007d |

• Concerns for bias and sensitivity in one out of two studies that observed effects | ⊕◯◯ SLIGHT Decreased absolute and relative uterine weights was observed in F1 and F2 weanling rats in a high confidence two-generation study (Fujii et al. 2005), although the effect was not observed in adult F1 animals so may be transient. A significant decrease in relative ovary weights was reported in a low confidence study in F0 and F1 adult rats (Pereira et al., 2007c). Otherwise, no organ weight changes were observed. |

||

| Histopathology |

High Confidence:

Procter & Gamble (1994)

Medium Confidence: Fujii et al. (2005), Shiraishi et al. (2006) Low Confidence: Manservisi et al. (2015) |

• Concerns for bias and sensitivity in the only study that observed effects | ⊕◯◯ SLIGHT A reduction in the size of the lobular structures of the mammary gland was observed in a low confidence study in parous F1 female rats (Manservisi et al. 2015). Otherwise, no histopathological changes were observed in ovaries, uteri, vaginas, or mammary glands. |

||

| Hormones | High Confidence: Shiraishi et al. (2006) | • Minimal concern for bias and sensitivity | • Single study | ◯◯◯ INDETERMINATE No effects were observed on steroid hormone or gonadotropin levels in female rats after subchronic exposure (Shiraishi et al. 2006). |

|

| Estrous cyclicity |

High Confidence:

Fujii et al. (2005)

Low Confidence: Shiraishi et al. (2006) |

• Minimal concern for bias and sensitivity | • Few studies | ◯◯◯ INDETERMINATE No effects were observed on estrous cyclicity in F0 or F1 females in a two-generation study (Fujii et al. 2005) or after subchronic exposure (Shiraishi et al. 2006). |

|

| Female morphological development | High Confidence: Fujii et al. 2005, Gray et al. 2000 | • Minimal concern for bias and sensitivity | • Single study | ◯◯◯ INDETERMINATE A statistically significant delay in the age at vaginal opening was observed in F1 rats in a two-generation study, likely related to decreased growth. No DEP- related effects on AGD were observed in F1 or F2 animals in this study (Fujii et al. 2005). |

|

3.6. Developmental effects

Figs. indicating the doses at which statistically significant developmental effects occurred are provided in the Supplementary Materials (Figs. S8–S12 and S18). The effects described in this section are limited to survival, growth, and structural alterations; other effects in developing animals (e.g. reproductive effects) are described in respective sections.

3.6.1. Summary of available studies

Four studies evaluated fetal survival following gestational exposure to DEP (Furr et al. 2014; Howdeshell et al. 2008; NTP 1988; Procter & Gamble 1994), and five studies evaluated the number of live pups at birth following gestational (Gray et al. 2000; Hardin et al. 1987; Setti Ahmed et al. 2018) or multigenerational (Fujii et al. 2005; RTI International 1984) exposure to DEP. Of these, only the continuous breeding study in CD-1 mice (RTI International 1984) observed a dose-related effect. The number of live F2 offspring at birth (males and females combined) was statistically significantly decreased by 14% in the 3640 mg/kg-day DEP exposure group relative to controls, whereas no effects on survival were observed in the F1 offspring. In a gestational exposure study in Sprague-Dawley rats, Howdeshell et al. (2008) reported a statistically significant increase in resorptions and fetal mortality at 600 mg/kg-day DEP, but this effect was not observed in any other higher or lower DEP dose groups and thus did not appear to be treatment-related. Otherwise, in the rat two-generation study and in the remaining gestational exposure studies in rats, mice, and rabbits, there were no effects on the number of implantations or resorptions (Fujii et al. 2005; NTP 1988; Procter & Gamble 1994), viability of fetuses (Furr et al. 2014; NTP 1988; Procter & Gamble 1994), or viability of pups at birth (Fujii et al. 2005; Gray et al. 2000; Hardin et al. 1987; Setti Ahmed et al. 2018). There was no effect on offspring sex ratio in any of the studies that assessed this endpoint, which included studies in rats, mice, and rabbits (Fujii et al. 2005; NTP 1988; Procter & Gamble 1994; RTI International 1984). Given the evidence of decreased fetal survival in the high confidence continuous breeding study in mice but lack of effect in all other studies, the evidence for DEP effects on fetal survival following gestational exposure is considered indeterminate.

The three studies that reported postnatal survival found differing results. In F1 female rats exposed to a low dose of DEP (0.173 mg/kg-day) from birth (PND 1) through sacrifice, there was a statistically significant increase in the postnatal mortality of F2 pups through PND 14 (Manservisi et al. 2015), although this result is considered low confidence due to the concerns discussed in Section 3.3. In contrast, no significant effects were observed in high confidence studies. The two-generation study in rats from Fujii et al. (2005) indicated a non-significant trend towards lower survival of F1 offspring at PND 21 in the DEP treatment groups, but this trend was not observed in F2 offspring and it is not clear that it is treatment-related. There was no effect on F1 offspring viability through PND 3 in mice exposed to 4,500 mg/kg-day DEP from GD 6–13 (Hardin et al. 1987). Taken together, the evidence for the effects of DEP on postnatal survival is considered indeterminate.

No effects on fetal growth were observed in seven studies conducted in rats, mice, and rabbits, of which all but one were considered high confidence for this outcome. The two-generation reproductive study in rats (Fujii et al. 2005) and the continuous breeding study in mice (RTI International 1984) both reported that F1 and F2 offspring body weights at birth were similar between DEP-treated animals and controls. Likewise, four gestational exposure studies indicated that fetal body weights of rats and rabbits (NTP 1988; Procter & Gamble 1994) or body weights of rats or mice at birth (Gray et al. 2000; Hardin et al. 1987; Setti Ahmed et al. 2018) were similar between DEP-treated animals and controls. While this data suggests that DEP does not impact fetal growth across multiple species, it was decided among reviewers that there were not enough studies available to support a judgement of compelling evidence of no effect. The evidence for effects of DEP on prenatal growth is therefore considered indeterminate.

Conversely, decreased postnatal growth was reported in multiple studies that evaluated this endpoint. In the high confidence two-generation reproduction study, Fujii et al. (2005) observed that F1 and F2 Sprague-Dawley rat offspring exposed to 1,297 mg/kg-day and 1,375 mg/kg-day DEP, respectively, had lower body weights relative to controls at PND 4, 7, 14, and 21. The decrease in body weight was statistically significant for F1 female pups at all time points, and for F1 and F2 male pups and F2 female pups at PND 21. These pups also had a delay in pinna detachment (a developmental biomarker) relative to controls, which was statistically significant for F1 males. Similarly, the high confidence continuous breeding study in mice by RTI International (1984) found that F1 male and female pup body weights at the time of weaning (PND 21) were lower in DEP-treated groups (3,640 mg/kg-day) compared to controls and remained lower than controls at the time of mating (PND 74 ± 10), although the authors did not perform a statistical analysis. Additionally, the low confidence multigenerational studies in rats observed statistically significant reductions in F1 weanling body weights (Pereira and Rao 2007), F1 adult body weights (Hu et al. 2016), and F2 body weights at PNDs 7 and 14 (Manservisi et al. 2015). The low confidence study by Setti Ahmed et al. (2018) that exposed rats from GD 8 – PND 30 reported a statistically significant decrease in F1 body weights beginning at PND 15. There was no effect on F1 offspring growth in the gestational exposure studies in mice by Hardin et al. (1987) (evaluated through PND 3) and in rats by Gray et al. (2000) (evaluated as adults), although these studies used shorter exposure duration (GD 6–13 and GD 14-PND 3, respectively). In peripubertal males exposed to DEP for 7 days, no effects on body weight were observed (Oishi and Hiraga 1980). Given the consistent reductions in offspring postnatal growth across all multigenerational studies including the high confidence studies by Fujii et al. (2005) and RTI International (1984), there is robust evidence that DEP exposure can affect postnatal growth.

The two high confidence studies that examined the incidence of fetal external, skeletal, and visceral malformations in rats (NTP 1988) and rabbits (Procter & Gamble 1994) found little to no effects of DEP exposure during gestation. However, the study in rats by NTP (1988) observed a dose-related statistically significant increase in the mean percent of fetuses with a rudimentary or full extra (supernumerary) lumbar rib, which is a skeletal variation (US EPA 1991). The study by Procter & Gamble (1994) in rabbits observed two malformed fetuses in two different litters in the highest DEP dose group (out of 80 total fetuses and 12 total litters in this dose group) and no malformed fetuses in the controls or lower DEP dose groups (out of 77–91 total fetuses and 12 litters per group); the observed malformations consisted of one fetus with fused and split ribs and missing lumbar and coccygeal vertebrae, and one with acrania, hernia umbilicalis, and incurved ribs. The authors did not consider this finding to be treatment-related because the malformations were of different types and the incidence was within the rate of historical controls, although historical control data were not provided as part of this study. There were no dose-related effects on skeletal variations in the rabbit fetuses, including on the number of ribs. Additionally, the low confidence study by Setti Ahmed et al. (2018) evaluated the morphological development of the intestines in F1 rats exposed from GD 8 – PND 30 and found alterations in enterocytes as well as supporting mechanistic evidence indicating decreased cell proliferation and enzyme activities but did not provide any quantitative data. Altogether, the evidence for DEP effects on fetal morphological development is considered slight.

3.6.2. Synthesis of results for developmental effects