Abstract

This paper examines critically the economic package announced by the Indian central government to counter the challenges of lives and livelihood in the Covid‐19 pandemic. This paper estimates the shares of the fiscal economic packages in two phases as per the shares of the vulnerable workers and number of Covid‐19 cases in the Indian states. The recent data on labour market are used from National Sample Survey Organization and data on Covid‐19 cases from Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. This paper recommends alternatively a fiscal stimulus package of Rs. 10 lakh crores (5% of GDP) with an immediate effect to counter the present problems of health, food and unemployment in the pandemic and should be extended to Rs. 24 lakh crores (12% of Indian GDP) to the Indian states for at least 1 year to protect the lives and livelihood of the most vulnerable, informal and migrant workers. The populous and poor states like Uttar Pradesh and Bihar have higher share of vulnerable workers and highly industrialized states like Maharashtra, Gujarat, Delhi and Tamil Nadu have higher number of Covid‐19 cases. Due to the unplanned lockdown in India, there has been a surge in Covid‐19 cases across the country that in turn led to an increase in vulnerable workers in poor states due to reverse migration from industrialized states to populous and poor states during the pandemic. Furthermore, the paper explains the five significant factors that justify the adoption of an expansionary fiscal policy rather than monetary policy.

Keywords: Covid‐19 pandemic, fiscal package, India, livelihood, lives, vulnerable workers

1. BACKGROUND

On May 12, 2020, the Indian Prime Minister announced a “big” economic package, under “Self Reliant India Campaign,” which was in response to addressing serious crisis in Covid‐19 pandemic, pertaining to “Land, Labour, Liquidity and Law,” of Rs.20 lakh crores (10% of GDP) (MoHFW, 2020). The package lacks government's social responsibility to protect lives and livelihood of the masses with higher public funding and this package had more liquidity, money, credit and loan instruments rather than fiscal policy instruments to provide health, education, food and decent work. This package has not adequately addressed the challenges and problems, emerged during Covid‐19 pandemic, faced by the vulnerable workers, especially informal and migrant workers in the Indian states and Union Territories. The problems and challenges are both from supply and demand side in the economy. On the one hand, GDP growth rate got hit by the pandemic and the unplanned lockdown resulted in −10.3% in Indian economy (IMF, 2020) while on the other hand, the job loss touched another level of rise with 20%–25% unemployment rate reported in the months of complete lockdown during April and May, 2020 (CMIE, 2020). However, the unemployment rate in India has now declined to 8.35% in August 2020, but it is still high.

The negative economic growth rates and higher unemployment rate reflect the extent of vulnerability of lives and livelihood. The rising number of Covid‐19 cases have pushed India to top second in the world and it has third global rank of the resulting deaths in the world (WHO, 2020). Khan (2020) and Narender and Vaishali (2020) state that countries with greater government's expenditure on health and health‐related infrastructure have successfully managed to flatten the curve of infected cases of Covid‐19. The situation in India thus demands more sincere and greater expenditure in public health care, which would in turn address the issues of lower GDP growth and higher unemployment rate. The International Labour Organization (ILO) report, 2020 estimated that an increase in fiscal package by 1% GDP would lead to 1% decline in the unemployment rate in the countries during Covid‐19 pandemic period. The economists like Prabhat Patnaik, Jayati Ghosh, Amartya Sen, Abhijit Banerjee and Raghuram Rajan argue for the fiscal stimulus package in the Keynesian economics context rather than monetarist economics context (Ghosh, 2020; Patnaik, 2020; The Hindu, 2020b). This is in view of considering the existence of larger share of people engaged in unorganized sector, more than 90% (ILO, 2018), many of whom have lost their jobs during the pandemic. India has higher shares of vulnerable workers who lost their jobs and livelihood in this critical time due to the nation‐wide lockdown. A survey reports that 92% of the workers in Gujarat and 59% workers in Maharashtra are not paid their wages by their employers in the lockdown period (Tirodkar, 2020). Another study showed that there are around 4,000 stranded, informal and migrant workers in 12 states in India, 8 of 10 workers lost their jobs in urban areas and 6 of 10 in rural areas in the lockdown period (The Hindu, 2020a). Thus, this paper highlights the urgent need to increase the fiscal stimulus as a fiscal expansionary policy of the central government from only 2% of GDP to 5% of GDP immediately for saving lives due to hunger and poverty. This can be further raised to 12% (Rs.24 lakh crores) in order to maintain minimum wages and generate aggregate demand in the economy. The raised fiscal stimulus will protect the lives and livelihood of 89% of the vulnerable workers including low‐paid regular, self‐employed and daily‐wage workers for at least 1 year in India. This paper is divided into six sections: (1) Background; (2) data and methodology; (3) need of expansionary Fiscal policy; (4) saving lives and livelihood in Indian states and union territories; (5) higher shares of vulnerable workers: benchmark for Fiscal stimulus and; (6) concluding remarks.

2. DATA AND METHODOLOGY

The present paper has critically examined the components of the economic package of Government of India to counter the problems of lives and livelihood due to the Covid‐19 pandemic. This paper has also examined the review of the literature to identify the nature and amount of relief package announced by government of India. The paper also examined the reports, papers and newspaper reports (CMIE, 2020; Rawal et al., 2020) on unemployment, deaths, distress and despair faced the workers and migrants during the unplanned full lockdown advocated by the central government in the months of March–June, 2020. For the recommendation of a fiscal stimulus to resolve more effectively the problems, this paper advocated the shares of Indian states in this fiscal stimulus package as per the shares of the vulnerable workers in these states and shares of Covid‐19 cases. For the estimation of the shares of the Indian states, we have used the recent data of (1) the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) 2017–18 at unit level of National Sample Survey Organization, Government of India, (2) Indian population census data are also used to estimate the percentage and actual number of vulnerable workers and (3) the number of Covid‐19 cases in Indian States from the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW, 2020). In order to estimate the extent of livelihood crisis and understand the urgent need of fiscal package, we have estimated the vulnerable workers by numbers and their shares in total workers state‐wise and union‐territory (UTs)‐wise by using periodic labour force survey (PLFS, 2019). The vulnerable workers include three categories of workers: (1) casual‐wage workers, (2) self‐employed workers excluding employers, and (3) regular salaried workers who earn less than Rs. 12000 per month as the average wage per day at Rs. 400, which is an estimate of the rural and urban stipulated wages, respectively, at Rs. 350 and Rs. 450 as per the VV Giri National Labour Institute of the central government of India—minimum wage committee report (Magazine, 2019). We are assuming that casual worker and regular worker without having any kinds of job contract have relatively high probability of job loss during COVID‐19. To estimate the number of the vulnerable workers, these three categories (a, b and c) were added and the percentage of vulnerable workers is multiplied by the population census data of the population to get the weighted average and thereafter the percentage shares of the Indian states. The estimated number of workers is adjusted to total Indian Census population. Furthermore, the reports of multilateral organizations, International Monetary Fund (IMF) are examined for the highest decline of GDP growth rate at global level in 2020–2021.

With the above‐mentioned data sources and literature, the paper reflects on three main aspects, which in turn become three objectives of this paper. The first objective is to emphasize on the need of expansionary fiscal policy in the health emergency of Covid‐19. The second objective aims to elaborate the challenges of saving lives and livelihood, especially the vulnerable workers. The third objective is to estimate and sustain the shares of fiscal stimulus with an immediate effect and for a year to stimulate the demand and supply in the Indian economy.

3. NEED OF EXPANSIONARY FISCAL POLICY FOR PROTECTION OF INFORMAL WORKERS

There are five prominent reasons to support the expansionary fiscal policy: (1) several economists argue Indian economy is suffering from demand crisis as well as supply shock and for raising the demand and reviving the supply, fiscal stimulus policy is more effective than monetary policy, (2) drawing lessons from capitalist economies like the US, which are spending more than 10% of GDP as the fiscal stimulus to counter the severe effects of Covid‐19 pandemic, (3) the higher share of the vulnerable workers (89%; see Figures 1 and A3 below) should be the benchmark for the allocation of the fiscal package to save them from the crash of the minimum wage during the lockdown as well as protection from hunger and despair. The estimated numbers and shares of the vulnerable workers as per the World Bank poverty line is $1.25 per day, which also justifies this allocation. The estimated share of the vulnerable informal and migrant workers, that is, 89% using PLFS (2019) data, which is also comparable to the estimates of 90%–95% by other studies and documents (BT, 2019; GOI, 2020; ILO, 2018), (4) the ranking order of the number of Covid‐19 cases found in different states and union territories by August 16, 2020 has correspondence with the ranking of the estimated shares of fiscal package of states and union territories, and (5) India, on reaching an all‐time high unemployment rate of 25% in the months of April–May, during the lockdown period (CMIE, 2020), stresses on the need of the higher fiscal stimulus. The government can also learn lessons from the economic history of the Great Depression during 1930s, which experienced 25% of unemployment rate, and Keynesian economics was used in that period to expand aggregate demand by more government spending to work in the multiplier process for higher GDP. The CMIE (2020) data estimated the job loss of 12.2 crores in the month of April, 2020 and unemployment rate by May 12, 2020 in India reached 25%.

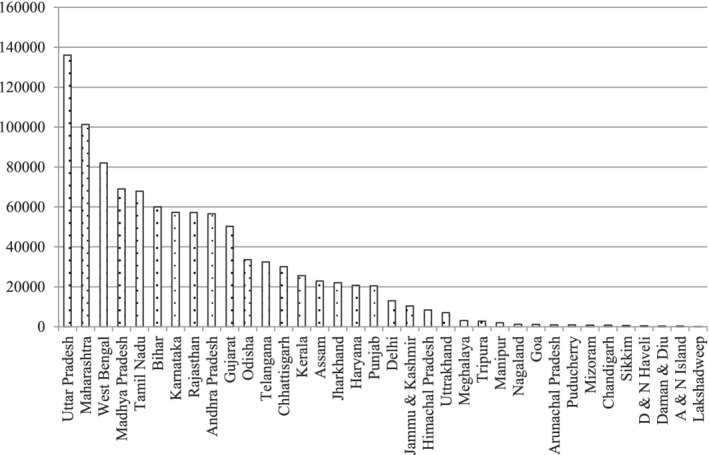

FIGURE 1.

Share of vulnerable workers in states and union territories (UTs) in India. Source: The authors constructed the figure from the data of PLFS (2019)

In the light of the above‐stated factors, the paper advocates 5% of GDP fiscal stimulus with an immediate effect rather than mere 2% as allocated by the Indian government to save the most vulnerable workers (57%) from hunger and starvation. The fiscal stimulus package should be extended to 12% of GDP to protect minimum wages of the vulnerable workers (89%) for at least 6 months, to fight the health and economic crises in a more decentralized manner with the leadership of the union government. This suggestion of fiscal stimulus corresponds to the recent ILO estimate on a positive impact of 1% increase in the government spending as a fiscal stimulus leads to a reduction in 1% in unemployment rate during the Covid‐19 pandemic (ILO, 2020). Furthermore, the informal and migrant workers in India are 400 million, who are severely hit by Covid‐19 as most of them are marginal on the basis of economic class, caste, gender, and region (Shah & Lerche, 2020). This implies they are super‐exploited on the basis of status of underpaid and over‐worked, reflecting their poor working and living conditions (Patnaik, 2020). In India, as per the Census 2011 data, 100 million workers are seasonally informal workers, they migrate for their seasonal employed work, mostly from rural areas to the urban areas of the poor economic states of India like Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh and Orissa. According to Bose and Azad (2020), this “big” economic package of 10% contains only 2% share of fiscal stimulus instruments and 8% share of liquidity and monetary instruments, which will not address the main challenge of deficiency of demand and the aggregate supply and a crash of supply‐chains and production in the economy. India's announced fiscal stimulus is much lower than the highest capitalist country, US ($2.7 trillion, 13% of its GDP, without bothering the increase in fiscal deficit in the US budget from $ 1trillion to $ 3.7 trillion in 2020), to counter the deficiency of aggregate demand and to improve the declined aggregate supply as well as the disturbed supply chains in the Covid‐19 pandemic.

Another contributing factor behind the urgency of introducing expansionary fiscal policy is the delayed response towards the deteriorating situation of the economy amidst a large number of stranded and dying migrant informal workers in various parts of the country. During the Covid‐19 pandemic, a critical issue of super‐exploitation of the workers under the neo‐liberal market reforms is observed. The central and state governments have been ignorant rather finding ways to extract the capital accumulation by increasing working hours, which is defined as a relative surplus for maximizing profits. This has resulted in super‐exploitation of the workers. The central government as well as the state governments, Rajasthan, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh and some other Indian states, have increased the working hours from 8 to 12 h. In addition to this, the composition of this big package, Rs. 8 lakh crores, is already released by the central bank of India (Reserve Bank of India—RBI) in the month of April, and the amount of Rs. 1.7 lakh crores is already issued by the central government. In order to generate additional money, loans and credit, the government has asked RBI to grant an additional Rs. 5 lakh crores with some government securities to support the Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs). Subsequently, from 13th May to 17th May, the Finance Minister provided the details of this economic package, which constituted of mere elaboration of monetary policy instruments and neoliberal market reforms and less of significant announcements of fiscal policy instruments.

The MSMEs and farmers are already in loan distress and especially during pre‐Covid‐19 pandemic period, they need more fiscal help to write‐off their earlier loans and reinitiate production and other activities to revive the employment opportunities. To counter the deficiency of demand due to alarming higher rate of unemployment and crash of wages and decline of production and destruction of the supply chains and productive activities in the nationwide lockdown at all India level, initiated by the central government in four phases during the time period between March 25, 2020 and May 31, 2020. The GDP growth rate is estimated to be negative in the economic year of 2020 (IMF, 2020), showing adverse conditions of productive and supply activities in the Indian economy. It was forecasted that the GDP would decline more at negative rate in the prevailing poor health Indian infrastructure conditions, with lowest public spending at 1% around at global level, as the cases of Covid‐19 virus are increasing and the curve could not be flattened up to August 15, 2020. The monetary measures have limited impact on aggregate demand, especially in the times of alarming higher rate of unemployment at 25% in the months of April and May, 2020 as per the CMIE data (2020). There is less need to use more monetary policy instruments and neo‐liberal market reforms to address the issues of the deficiency of aggregate demand and health crisis with low public funding. Along with lower demand, negative economic growth and production, there are issues of lower labour supply and shortage of the related inputs of the output in the critical health crisis. With negative growth rate, increasing unemployment, India is also entrapped in the vicious circle of poverty and hunger as the global hunger index of India is 102 of 117 countries, during 2019 (GHI, 2019). This reflects at the extent of vulnerable conditions for the marginal including migrant and informal workers and urban and rural poor people during Covid‐19 pandemic. In India, 90% of workers are informally employed or underemployed in all the three sectors, viz., agriculture, industrial and services sectors. The dominant numbers of workers are engaged in the agrarian sector, as 144 million are agriculture workers and 25 million are tenants (Padhee et al., 2020). These higher numbers of rural workers show the vulnerability of employment in rural areas, especially in times of covid‐19 pandemic as 70% of population live in rural India. On June 30, 2020, for containing hunger and starvation, the central government of India launched lately the free food grain and pulses transfer scheme to 810 million people for a 5‐month period, July–November 2020. However, other food items required for cooking are neglected in this distribution, like edible oil, spices, vegetables, salt, cooking gas, etc. Along with these late interventions to save people from hunger, there is also a need to ensure food security with more fiscal budget.

4. SAVING LIVES AND LIVELIHOOD

To contain the adverse effects of Covid‐19 in India, the central government initiated the lockdown at national level for 68 days, since March 22, 2020–June 30, 2020, continued in different phase that carried many social and physical restrictions on movement of people to contain the infections of Covid‐19 virus. The national unlock period was also started since July 1, 2020, with immediate implications for the disadvantaged groups due to the hike in the Covid‐19 cases in rural areas due to return migration and also in states, like Kerala, which has recovered very fast during the lockdown period. On August 16, 2020, there are 2.6 million cumulative cases of Covid‐19 virus in India and 50,122 people have died due to the Covid‐19 infections, though with 97% recovery rate in India (WHO, 2020), the curve of Covid‐19 cases is not flattening. The lockdown has slowed down the fatality rate in India to save lives amidst persisting uncertainties with increasing numbers of the infected cases of the Covid‐19 virus, especially in mega cities, like Mumbai, New Delhi, Ahmedabad, Indore, Pune, Chennai, etc. In the national lockdown period, the migrant workers were stopped by the central and state governments to move out from urban areas to rural areas, and so were at greater risk of being infected. This was the mistake or violation of the human rights of migrants' mobility to their home states done mainly by the developed states governments as well as central governments. The human mobility violation in the lockdown period delayed the infections but the spread of Covid‐19 virus is being transferred on a greater scale in the poor and underdeveloped states of India, especially in rural areas during the unlock period. In the unlock period, there are harsh implications for livelihood of the workers, especially of the vulnerable group of the workers—the lower section of informal and almost all migrant workers who work on casual basis in urban areas.

The Prime Ministerial package of Rs. 20 lakh crores (nearly 10% of GDP) includes the already allocated amount 0.8% of its GDP (Rs. 1.7 lakh crores) as a fiscal package to counter the challenges of lives (health‐crisis due to Covid‐19 pandemic) and livelihood (emerged food‐crisis due to increased unemployment especially for the migrant and informal workers). According to Indian GDP at current prices, it is Rs. 204 lakh crores. It is very important to understand the break‐up of the announced “mega” economic package of Rs. 20 lakh crores by the Prime Minister, as it has two broad components—fiscal and monetary measures. The fiscal package announced by government of India so far is still very low (i.e., 2% from the announced 10%) in comparison to other countries, as Japan allocated 21% of GDP, United States spent 13% of GDP, 9.9% in Australia, 8.4% in Canada, 6.5% in Brazil and so on and so forth (Das, 2020), showing the lowest share of India's fiscal package, that is, 0.8 of GDP (Das, 2020). On the name of fiscal stimulus, Prime Minister Modi announced Rs. 20 lakh crores (10% of GDP) which seem to be more as a monetary policy package with higher share of the credit and loan provisioning by the central bank—RBI. On the contrary, the suggested fiscal package in the paper could result in more protection for the informal migrant workers from their crash of wages and job‐losses as well as to address poverty and hunger during the Covid‐19 pandemic.

Das (2020) estimated empirically that 5% of fiscal stimulus in India can achieve 9% nominal GDP growth with 4% inflation rate (or 6% real GDP growth rate with 3% inflation rate), which can easily lead to 5% real GDP economic growth in 2020–2021. These estimates of real GDP with fiscal expansionary policy are possible through borrowing from RBI in the emergency of the Covid‐19 pandemics. The expansionary fiscal policy can be used by the central government to provide funds to the states to address the issues of lives and livelihood. This fiscal stimulus will lead to higher aggregate demand, which is very crucial to revive Indian economy.

The fiscal stimulus should be used for higher public health and education expenditure, support for micro, small and medium enterprises and universalization of MNREGA, universalization of public distribution system and universal public health care, revival of demand to facilitate supply or production in the Indian economy in post‐lockdown period, as the unemployment rate has touched the benchmark of the Great Depression of unemployment rate, that is, 25%. The status of migrant or informal workers should be the benchmark for the devolution of this proposed fiscal package by the union government. However, Modi government seems reluctant to use expansionary fiscal policy and so has more focus on expansionary monetary policy in the announced package, under “Self‐Reliant Indian Campaign”. It may be due to the issues of the fiscal deficit and thereafter the worry for the downgrading of credit‐rating for business environment by the international credit agencies and fear of outflows of foreign capital. But the government should not be worried if it adopts following four measures, the first measure is if RBI monetize the union government's fiscal stimulus followed by the second measure, by rationalizing public–private consumption expenditure, as the share of private consumption expenditure is significantly higher at 60% of GDP in 2019–2020 while the government expenditure is 12% (Das, 2020). It is suggested to increase government expenditure to 17%–24% by spending extra 5%–12% as fiscal stimulus to facilitate the crowding‐in effects as well as the multiplier effects for revival of the aggregate demand in the economy. The third measure is to optimally utilizing the huge foreign exchange reserve with India, that is $ 475 billion, and the fourth effective measure is to bring back our sinking economy by levying of wealth taxes on super‐rich Indians or an imposition of property tax on the wealthy economic class in India to revive supply as well as demand due to the shocks in covid‐19 pandemic and post‐covid‐19 pandemic periods (Neog & Gaur, 2020).

5. HIGHER SHARES OF VULNERABLE WORKERS: BENCHMARK OF FISCAL STIMULUS

In the lockdown period, there are a number of reports of despair and distress faced by the vulnerable workers, the most horrendous incidence happened on May 8, 2020, in which 16 migrant workers, while asleep on train tracks, died of crushing under a train. They were returning from Aurangabad in Maharashtra to their home state, Madhya Pradesh (IE, 2020). On 16 May, early morning at around 3.30 a.m., a trailer rammed into a stationary truck on a highway near Auraiya in Uttar Pradesh. The accident killed 24 people and injured 36 people, all migrants, some of whom were returning from Delhi and some were coming from Rajasthan and heading to Madhya Pradesh (HT, 2020a). Many migrant workers died while returning to their home states, especially belonging to Bihar and Uttar Pradesh from the cities of the highly developed states in India, Maharashtra and Gujarat. The authors observe some pull and push factors behind this reverse or return migration. The main push factor includes the loss of livelihood for regular worker in the informal sector and daily work in both formal and informal sectors due to the lockdown and health risks due to the higher reported cases and fatality rates in the cities and the developed states, like Maharashtra and Gujarat. The pull‐factor of reverse or return migration are as follows: (1) the hope of getting some source of livelihood in their village in terms of food or cash from the relatives/family members and (2) lower health risk due to lower number of Covid‐19 cases and lower fatality rates in rural areas. There are various reports about high number of deaths caused due to distress, hunger and starvation, that is, 181 in the period from March 18 to April 12, 2020, and Covid‐19 infection led to 334 deaths in this period (Rawal et al., 2020).

There is an urgent need for decentralization of governance as a bottom‐up approach under the leadership of the union government with local governance to be monitored by the chief‐ministers and district administration to counter the on‐going health and food crises in the times of Covid‐19 in India. The devolution of fiscal stimulus of 5% of GDP or Rs.10 lakh crores can be done by identifying and directly depositing a fixed (calculated) amount in their bank accounts or providing them basic necessities like food, fuel, shelter and medical aid to vulnerable workers in different states and union territories. For countering the Covid‐19, other states can learn lessons from Kerala, which has successfully flattened the curve of the cases of Covid‐19 infections and fatality. The share of vulnerable workers is estimated at 89% (33.1 crores) in total workforce (37.3 crores) at the all‐India level. Figure 1 shows the descending order of shares of the vulnerable workers out of total vulnerable workers in India. Out of 33.1 crores vulnerable workers in India, the two states have double‐digit higher shares, namely Uttar Pradesh (13.61%) and Maharashtra (10.13%). Eight states have more than 5% and less than 10% shares of the vulnerable workers, which are as follow: West Bengal (8.21%), Madhya Pradesh (6.90%), Tamil Nadu (6.79%), Bihar (6.01%), Karnataka (5.73%), Rajasthan (5.72%), Andhra Pradesh (5.66%) and Gujarat (5.03%).

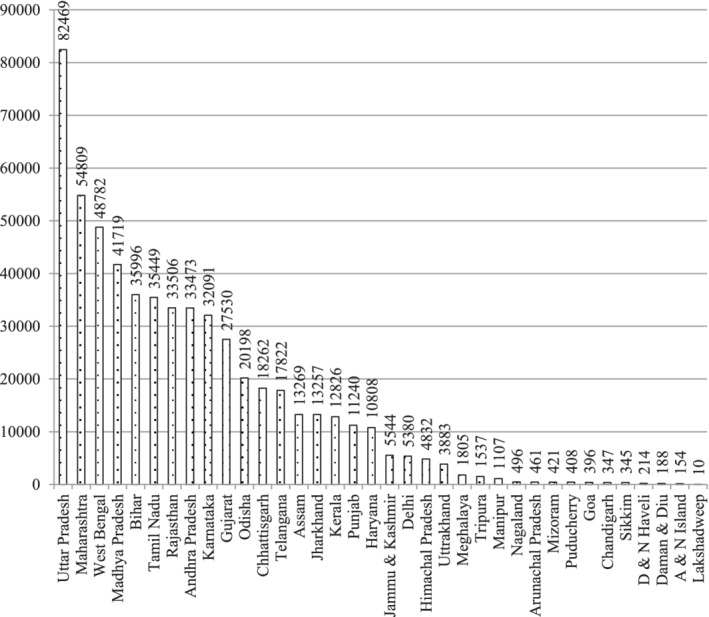

It can be observed that among the states, UP and Maharashtra have the highest share of vulnerable workers due to the highest population in UP and Covid‐19 cases are highest in Maharashtra, which necessitates the urgent need of the proposed fiscal stimulus to save lives and livelihood. In India, the number of Covid‐19 cases on May 11, 2020 was 67,152 (20,917 recovered and 2,206 deaths reported), the descending rank order of the states by number of cases as shown in Figure 2. Figures 3 and 4 show the recent shares of Covid‐19 cases and deaths in the Indian states, in descending order out of the total respective Indian cases (2.6 million) and deaths (50.8 thousand) due to Covid‐19 virus by August 16, 2020. Figure 5 shows that if the government of India allocates a fiscal package to the states and union territories 5% of GDP, viz., Rs. 10,00,000 crores, as per the shares of vulnerable workers then it can help these states and UTs to fight for the Covid‐19 health crisis as well as food and livelihood crisis in their respective economies, mainly for below poverty line and most vulnerable workers.

FIGURE 2.

Total number of Covid‐19 cases in Indian states and union territories as on May 11, 2020. Source: The authors constructed the figure by using the data of MOHFW (2020)

FIGURE 3.

Percentage shares of Covid‐19 Cases (2.62 million) in Indian states by August 16, 2020. Source: The authors used MOHFW (2020)

FIGURE 4.

Percentage shares of Covid‐19 deaths (50.8 thousand) in Indian states by August 16, 2020. Source: The authors used MOHFW (2020)

FIGURE 5.

Share of states in Fiscal package of Rs. 10 lakh crore (5% of GDP). Source: The authors constructed the figure by using the data of PLFS (2019)

As the CMIE (2020) data estimated 12.2 crores job loss in the month of April, 2020 during the lockdown period and the unemployment rate has touched the peak even on May 11, 2020 at 25% (rural unemployment rate is 24% and urban unemployment rate is 26%), the probability of higher job‐loss and higher unemployment rate is greater for the daily wage‐workers who are the most vulnerable sections in the Indian labour market. So, they should get priority in the protection of the workers, we have also estimated the share of the casual or daily‐wage workers in Indian labour market, which is 25% along with the respective shares of self‐employed and regular waged workers are 52% and 23%as given by region and gender in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Percentage share (%) of self‐employed, regular and casual/daily‐wage workers in Indian labour market by region and gender in 2017–2018

| Region/India | Gender | Self‐employed | Regular worker | Casual worker | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rural | Male | 57.83 | 13.96 | 28.21 | 100 |

| Female | 57.73 | 10.52 | 31.76 | 100 | |

| Person | 57.81 | 13.12 | 29.07 | 100 | |

| Urban | Male | 39.21 | 45.7 | 15.08 | 100 |

| Female | 34.74 | 52.14 | 13.12 | 100 | |

| Person | 38.3 | 47.02 | 14.68 | 100 | |

| India | Male | 52.31 | 23.38 | 24.31 | 100 |

| Female | 51.92 | 21.03 | 27.05 | 100 | |

| Person | 52.22 | 22.83 | 24.95 | 100 |

Source: The authors constructed the table by using the unit level data of PLFS (2017–2018).

The remaining share (amount) of the fiscal package is 43% (Rs.4.3 lakh crores), which should be given to the states for the public health expenditure related to Covid‐19 pandemic. The share for the minimum wage rate amount to the fiscal stimulus amount is 238% (Figure 6), showing the lower amount of Rs.10 lakh crores or 5% of GDP of the immediate fiscal stimulus proposed to sustain the lives of the most vulnerable migrant and informal workers at least for 1 year. This implies that the government has to increase the fiscal stimulus amount to stabilize the minimum income of 89% of the vulnerable workers in coming months with a larger fiscal amount of budget of Rs. 24 lakh crores, which is 12% of GDP, via generating other sources of revenue in the emergency period, like more monetized amount from RBI, taxation on the Indian super‐rich as wealth and inheritance taxes. There should not be more concerns about the fiscal‐deficit and credit rating in the times of the global emergency of Covid‐19 pandemic. Moreover, the Indian economy can work in the multiplier process so that the minimum wages can be assured in the coming months after sustaining the 1‐year poverty trap, especially for the daily‐wage workers.

FIGURE 6.

Shares of World Bank Poverty Line ($1.25 per day) and minimum wage (Rs.400 per day) amounts to Fiscal package of Rs. 10 lakh crores. Source: The authors constructed the figure by using the data of PLFS (2019)

On the basis of the above discussion, the paper suggests a fiscal package consisting of four components through universalization of public sectoral services and policies with the prominent role of central government funding to save lives and livelihood—(1) universalization of public health care system in India, (2) universalization of public distribution system (PDS), (3) universalization of Mahatma Gandhi Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MNREGA) and (4) universalization of secondary and vocational education. Moreover, the fiscal package should have public spending by the central government for assisting the states and union territories with Rs. 10 lakh crores (5% of GDP) to address the issues of hunger and poverty to cover every spheres of healthy and balanced diet via universalization of public distribution system (PDS) to all. This in turn should be extended to Rs.24 lakh crores (12% of Indian GDP) to ensure the minimum wage of Rs. 400 per day to 89% of the vulnerable workers) via universalization of MNREGA for 1 year from rural to urban areas, by the union government of India to its states and union territories. The duration of fiscal package should be 1 year, which should include the expenses of universalization of public health care including the research and development of vaccination for the Covid‐19 pathogen, universalization of secondary education and training to upgrade education, skill and training, especially for the vulnerable population in the post‐covid‐19 period. The fiscal package is required to fight the crises of lives and livelihood due to the nationwide lockdown during the Covid‐19 pandemic. The allocation of this package should be directly spent on the most affected population—the vulnerable workers, such as casual, self‐employed, low‐paid workers, small and marginal farmers; and the agricultural labour, which also include migrant and informal labourers.

6. CONCLUDING REMARKS

This paper examines the Prime Minister's announcement of “mega” economic package under “Self Reliant India Campaign” to release Rs. 20 lakh crores (10% of GDP) on May 12, 2020. The step is a part of the expansionary monetary policy while less of expansionary fiscal policy, as it is only 2% of GDP, which is the fiscal share out of the total 10% of the Modi government's economic package. Alternatively, this paper supports the recommendations and suggestions of the various economists and policymakers for the fiscal package of Rs. 10 lakh crores (5% of GDP) and its should be extended to Rs. 24 lakh crores (12% of Indian GDP) for the immediate disbursal to the Indian states and union territories for at least 1 year to protect both the most vulnerable, informal and migrant workers, by the union government to fight the crises of lives and livelihood due to the Covid‐19 pandemic. Furthermore, the above analysis in this paper has justified, verified and tested to advocate the expansionary fiscal policy to undertake immediate measures for the coming months for the following five significant factors: (1) The stated fiscal package is advocated as per the World Bank poverty line definition of $ 1.25 (see Figure A1 in Appendix A); it would maintain the minimum wage of Rs. 400 per day, while allocating the fiscal package with the multiplier effects in coming months (see Figure A2 in Appendix A); (2) the ranking in terms of incidences of Covid‐19 cases is also considered for the suggested amount of fiscal stimulus (see Figures 2, 3 and 4); (3) the share of informal workers as estimated by many economists in the range of 90%–95% corroborates with our estimate from PLFS data, that is 89%, which will resolve the livelihood problems for the next 1 year; (4) the “Great Depression” experience of 1930s of the alarming unemployment rate like today in India had reached 25%, consolidates the need of the higher fiscal stimulus and (5) looking at the higher spending, that is, more than 10% of GDP, made by the developed and capitalist economies in the times of Covid‐19 pandemic, the Indian central government should also adopt an expansionary fiscal policy by creating more avenues of taxes as well as violation of limits of fiscal deficits to expand aggregate demand and stability of GDP in the Indian economy. With higher fiscal stimulus packages by the Indian central government, there is also a need to ensure the proper utilization of the public funds. As per the report of SWAN—Stranded Workers Action Network (HT, 2020b), 80% of migrant daily‐wage stranded workers in the national lockdown period could not get governmental ration and 68% of these workers could not get cooked food supplied by the government. This implies that the only way out for Indian government to help the poor and also to stabilize the economy is by increasing the fiscal stimulus amount to protect the survival of the most vulnerable informal and migrant workers via four types of the universalization of public services to save lives and livelihood, especially marginal and migrant workers—universalization of public distribution system, MNREGA, health, and secondary education during the Covid‐19 period as well the post‐covid‐19 period. Direct cash transfers should also be used along with assurance of food availability and public provisioning of universal healthcare and education irrespective of the citizenship documents and socio‐economic categories. The fiscal stimulus of Rs. 10 lakh crores (5% of GDP) is required for the survival of the most vulnerable workers and stabilize minimum income of the vulnerable workers, with a greater fiscal amount of budget of Rs. 24 lakh crores, which is 12% of GDP, via generating other sources of revenue in the emergency period, like more monetized amount from RBI, taxation on the Indian super‐rich as wealth and inheritance taxes and utilizing the PM Care fund collected by the central government during the Covid‐19 pandemic.

Biographies

Narender Thakur teaches at Department of Economics, Bhim Rao Ambedkar College, University of Delhi, as an Assistant Professor and completed his Post‐doctoral fellowship from Indian Council for Social Science Research in Centre for Economic Studies and Planing (CESP) and Zakir Husain Centre for Educational Studies (ZHCES), Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, India. He did his Master of Science in Econometrics from University of Nottingham, United Kingdom. His teaching and research areas of specializations are Political Economy, Macro Economics, Economics of Education and Migration, and Econometrics.

Manik Kumar is working as a Policy Analyst with CBGA. His areas of research interest include informal economics (employment and enterprises), economics of discrimination, caste and gender economics. Prior to joining CBGA, he has worked as a Research Associate at Center for Entrepreneurship Development, National Institute of Rural Development, Ministry of Rural Development, Government of India, Hyderabad. He has been a consultant in “Programme on Poverty and Inequality” with Prof. Jens Lerche, School of Oriental and African Studies, Faculty of Law and Social Sciences, University of London. In the past, he had worked as a Research Assistant in an ICSSR Sponsored Project on “Rural Transformation and Changes in Living Condition in not so Dynamic States of India”. He has completed his Ph.D. in Economics from Banaras Hindu University (BHU), India.

Vaishali has completed her Doctorate of Philosophy in Education from Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi, India. She is presently working as Consultant in National Institute of Educational Planning and Administration, New Delhi, India. Her research interest areas include‐Education, Sociology, Gender and issues concerning Socio‐Economic Exclusion.

APPENDIX A.

FIGURE A1.

Budget in rupees based on World Bank Poverty Line $1.25 per day for 6 months in states. Source: The authors constructed the figure by using the data of PLFS (2019)

FIGURE A2.

Budget in rupees based on Rs.400 per day: Minimum wage for 6 months in states. Source: The authors constructed the figure by using the data of PLFS (2019)

FIGURE A3.

Percentage share of vulnerable workers out of total workers in India, states and union territories. Source: The authors constructed the figure by using the data of PLFS (2019)

Thakur N, Kumar M, Vaishali. Stimulating economy via fiscal package: The only way out to save vulnerable Workers' lives and livelihood in Covid‐19 pandemic. J Public Affairs. 2021;e2632. 10.1002/pa.2632

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

1. The data that support the findings of this study are available in PLFS (2019). These data were derived from the following resources available in the public domain (http://mospi.nic.in/sites/default/files/publication_reports/Quaterly_Bulletin_October_December_2019.pdf). 2. The data that support the findings of this study are available in MOHFW (2020) at (https://www.mohfw.gov.in).

REFERENCES

- Bose, P. , & Azad, R. (2020, May 14). India needs fiscal stimulus, Not Liquidity Infusion. The Wire . Retrieved from https://thewire.in/economy/liquiduty-fiscal-stimulus-covid-19-relief

- BT . (2019). Labor reforms: No one knows the size of India's informal workforce, not even the government; New Delhi. Business Today .

- CMIE . (2020). Unemployment rate in India, New Delhi: Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy. https://unemploymentinindia.cmie.com/. [Google Scholar]

- Das, S. (2020, May 6). An estimation of required fiscal stimulus to revive the economy in India. Vikalp . Retrieved from https://vikalp.ind.in/2020/05/an-estimation-of-required-fiscal/

- GHI . (2019). Mukerji R. Global Hunger Index 2019, (1–72). Dublin: Helvetas. https://www.globalhungerindex.org/pdf/en/2019.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, J. (2020). A critique of the Indian government's response to the Covid‐19 pandemic. Journal of Industrial and Business Economics, 47, 519–530. 10.1007/s40812-020-00170-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- GOI . (2020). Economic Survey 2018–19, New Delhi: Government of India. https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/budget2019-20/economicsurvey/index.php. [Google Scholar]

- HT . (2020a, May 16). 24 migrants killed in road accident in Uttar Pradesh Auraiya. The Hindustan Times .

- HT (2020b, May 12). Gaps in government's migrants' transfer plan highlighted, remedies sought: Stranded workers action network (SWAN) Report .

- IE . (2020, May 8). Aurangabad train accident: 16 migrant workers run over, probe ordered; Delhi. Indian Express‐Daily Newspaper .

- ILO . (2018). India labor market update 2017. Geneva: International Labor Organization. https://www.ilo.org/newdelhi/whatwedo/publications/WCMS_568701/lang-en/index.htm [Google Scholar]

- ILO (2020). Updated estimates and analysis. In ILO monitor: COVID‐19 and the world of work (6th ed.). International Labor Organization. [Google Scholar]

- IMF . (2020). Economic Outlook Update June, (1–20). Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2020/06/24/WEOUpdateJune2020. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, A. S. (2020, October 19). Socialism has been a handy weapon in successfully fighting COVID‐19 pandemic. Indian Express . https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/constitution-of-india-socialist-secular-preamble-supreme-court-plea-6779784/

- Magazine, A. (2019). Expert committee recommends Rs 9,750 monthly national minimum wage. The Indian Express . https://indianexpress.com/article/business/expert-committee-recommends-rs-9750-monthly-national-minimum-wage-5584848/

- MOHFW . (2020). COVID‐19 state wide status, New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. https://www.mohfw.gov.in/. [Google Scholar]

- Narender, & Vaishali. (2020, October 15). Health crisis in India during COVID‐19 pandemic: Indicator of failing neo‐liberal capitalism. Stree Mukti Blog . http://www.streemukti.in/2020/10/health-crisis-in-india-during-covid-19.html

- Neog, Y. , & Gaur, A. K. (2020). Tax structure and economic growth: A study of selected Indian states. Economic Structures, 9, 38. 10.1186/s40008-020-00215-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Padhee, A. , Kar, B. , & Choudhury, P. (2020). The lockdown revealed the extent of poverty and misery faced by migrant workers; New Delhi. The Wire . https://thewire.in/labour/covid-19-poverty-migrant-workers

- Patnaik, P. (2020, April 27). Covid‐19 crisis calls for universal delivery of food and cash transfers by the state. The Indian Express . https://indianexpress.com/profile/columnist/prabhat-patnaik/

- PLFS . (2019). Periodic Labor Force Survey‐PLFS‐July 2017 to June 2018. Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (MoSPI), National Statistical Office, Government of India, New Delhi.

- Rawal, V. , Manickum, A. , & Rawal, V. (2020, April 14). Are distress deaths necessary collateral damage of Covid‐19 response? News Click . https://www.newsclick.in/Are-Distress-Deaths-Necessary-Collateral-Damage-of-Covid-19-Response

- Shah, A. , & Lerche, J. (2020, July 13). The five truths about the migrant workers' crisis. The Hindustan Times . https://www.hindustantimes.com/analysis/the-five-truths-about-the-migrant-workers-crisis-opinion/story-awTQUm2gnJx72UWbdPa5OM.html

- The Hindu . (2020a). Data 80% of urban workers lost jobs during coronavirus lockdown: Survey; New Delhi. The Hindu Newspaper .

- The Hindu (2020b, May 5). Covid‐19 challenge: India must decide on a large stimulus package says professor Abhijit Banerjee. The Hindu .

- Tirodkar, A. (2020). During Lockdown, 59% Workers Not Paid Wages in Maharashtra, 92% in Gujarat: Study. News Click, https://www.newsclick.in/During-Lockdown-59%25-Workers-Not-Paid-Wages-Maharashtra-92%25-Gujarat-Study. [Google Scholar]

- WHO . (2020). Covid‐19 Data, Geneva: World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/data/gho. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

1. The data that support the findings of this study are available in PLFS (2019). These data were derived from the following resources available in the public domain (http://mospi.nic.in/sites/default/files/publication_reports/Quaterly_Bulletin_October_December_2019.pdf). 2. The data that support the findings of this study are available in MOHFW (2020) at (https://www.mohfw.gov.in).