Abstract

Using the ongoing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic as a case study, this paper engages with debates on the assimilation of Asian Americans into the US mainstream. While a burgeoning scholarship holds that Asians are “entering into the dominant group” or becoming “White,” the prevalent practices of othering Asians and surging anti‐Asian discrimination since the pandemic outbreak present a challenge to the assimilation thesis. This paper explains how anger against China quickly expands to Asian American population more broadly. Our explanation focuses on different forms of othering practices, deep‐seated stereotypes of Asians, and the role of politicians and media in activating or exacerbating anti‐Asian hatred. Through this scrutiny, this paper augments the theses that Asian Americans are still treated as “forever foreigners” and race is still a prominent factor in the assimilation of Asians in the United States. This paper also sheds light on the limitations of current measures of assimilation. More broadly, the paper questions the notion of color‐blindness or post‐racial America.

Keywords: Asian Americans, assimilation, model minority, othering, pandemic, racial discrimination, yellow peril

1. INTRODUCTION

Andrew Yang, an Asian American and former Democratic presidential candidate who famously claimed that he is the opposite of Donald Trump, an “Asian man who likes math,” confessed that he felt a bit ashamed of being Asian when being starred at and frowned upon at a grocery store in March 2020 (Yang, 2020). This happened just weeks after he quit the presidential run and at a moment when he just thought his place in this nation “was more than ever assured.” Yang's discriminatory experience was not unique. Since the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19), across the United States, many Asian ethnics have suffered various forms of discrimination, from physical attacks to verbal harassment to vandalism. For instance, in Midland, Texas, a Burmese American family, including a 2‐ and 6‐year‐old, were stabbed during grocery shopping because the suspect thought they were Chinese (Melendez, 2020). According to a recent survey, more than 30% of Americans have witnessed someone blaming Asians for the coronavirus pandemic, whereas 60% of Asian Americans said they have seen the same behavior (Ellerbeck, 2020). As of 3 June 2020, as many as 2066 instances of harassment against Asians have been reported since mid‐March (Borja et al., 2020).

Disease threat often gives rise to discrimination and scapegoating “others,” for example, foreigners, immigrants, and marginalized groups. For instance, during the Ebola outbreak of 2013, West African immigrants became victims of racial discrimination and harassment. On the other hand, Black Americans were not folded into Ebola‐based targeting, suggesting the accepted “Americanness” of Black Americans and the willingness to selectively distinguish between Black Americans and West African immigrants. By contrast, in the pandemic brought on by COVID‐19, it is not just Chinese immigrants, but any Asian American perceived as having connections to China (e.g., some Southeast Asians and other East Asians) due to false stereotypes that Asians “look‐alike” and anti‐Asian/Chinese sentiment (e.g., the “yellow peril” stereotype as discussed later), have become potential targets (Tessler, Choi, & Kao, 2020). 1 This contrast raises the following questions: Why do Asian Americans become the target of racial aggression related to COVID‐19? What does the rising anti‐Asian discrimination tell us about the assimilation of Asian Americans into the US mainstream? Indeed, no group should face discrimination, regardless of their immigration status or ethnic background. However, the COVID‐19 related discrimination facing Asian Americans as a collective certainly sheds light on their “foreign” status in the American society.

Scholars have been debating about whether Asians are joining the American mainstream. A burgeoning scholarship has shown that the boundaries between some Asian Americans 2 and Whites are blurring or becoming more flexible (for reviews, see Kim, 2007; Song, 2019). As one side of the debate argues, some Asian ethnics (e.g., East Asians and South Asians) are becoming “honorary Whites” and are changing the racial hierarchy in the United States, despite never “achieving” full acceptance as “Whites” (Bonilla‐Silva, 2004). According to common measures of assimilation, Asian Americans have been or will soon integrate into the dominant group. In some forecasts, certain Asian ethnics (e.g., East Asians) will ultimately be perceived and counted as Whites before the mid‐century (Gans, 2012).

Contradictory to the assimilation thesis, other scholars have argued that Asians are still considered “forever foreigners” (Zhou, 2004). Despite being proclaimed as “model minority,” Asian Americans' economic mobility often engenders less social acceptance and intensifies racism towards them (Kim, 2007). At times, Asians are suspected as foreign foes, attached to the long‐standing “yellow peril” stereotype. In this sense, Asians' improved status alone does not bring them into the US mainstream.

We find that the surge of anti‐Asian discrimination during the COVID‐19 pandemic provides a good opportunity to engage with the dialog about the assimilation of Asian Americans. The swift racialization of the coronavirus, we argue, is a strong case that exemplifies the perpetual marginalized and conditional status of Asian Americans. In what follows, we first briefly review scholarship on the assimilation of Asians, the racialization of Asians, and “othering”; then we draw upon the ongoing pandemic crisis as a case study to understand the dramatic rise of anti‐Asian racism and evaluate the Asian assimilation thesis.

2. ARE ASIAN AMERICANS ASSIMILATING INTO THE US MAINSTREAM?

A large body of scholarship contends that some Asian ethnics are assimilating into the American mainstream or becoming “White” (Alba & Nee, 2003; Gans, 2005; Nee & Holbrow, 2013). As pointed out, Whites view Asians as being culturally more similar to them than Blacks and are more willing to accept Asians' entry into the majority group (Gallagher, 2004; J. Lee & Bean, 2007). Hence, Asians appear to “blend” more easily with Whites, and group boundaries appear to be fading more rapidly for Asians than for Blacks (Jennifer Lee & Bean, 2010; Warren & Twine, 1997). To facilitate their closeness to Whites and expedite the assimilation process, some Asians engage in “Whitening behaviors” such as anglicizing their names or distancing themselves away from Blacks (Dhingra, 2003; Zhao & Biernat, 2018). In this sense, Asian Americans are aligning with Whites in a new Black/non‐Black divide and appear to be undergoing a process of social “whitening” (Gans, 2005) in ways akin to the incorporation of European immigrants (Jennifer Lee & Bean, 2010; Warren & Twine, 1997). As social and cultural distances separating Asians and Whites have been reduced, ethnic origins are not considered to be especially relevant for most interactions (Alba & Nee, 2003, p. 287).

When evaluating the incorporation of Asians Americans into the mainstream, previous studies often rely on commonly used measures of immigrant assimilation, including socioeconomic status (SES), spatial concentration, language assimilation, and intermarriage (Waters & Jiménez, 2005). According to these measures, Asian Americans, as a group, are “blending in” with the mainstream society. As argued by Jiménez and Horowitz (2013), Asian Americans, not Whites, are in some cases associated with success. Put differently, Asian's ability to move up the socioeconomic ladder, their educational achievements, and their growing rates of residential integration and intermarriage with Whites are often viewed as evidence of Asians' assimilation (Drouhot & Nee, 2019; Gans, 2012; Jennifer Lee & Bean, 2010). Thus, compared to class, the significance of race is declining in the post‐civil rights era (Sakamoto, Goyette, & Kim, 2009).

3. FOREVER FOREIGNERS AND THE RACIALIZATION OF ASIAN AMERICANS

Contrary to the assimilation thesis, numerous other studies have maintained that Asians Americans are still seen as “forever foreigners” (Okihiro, 2014; Tuan, 1998; Xu & Lee, 2013; Zhou, 2004). Unlike people of European descent, Asians are perceived as unassimilable and their loyalty to the United States is often questioned (Ancheta, 2006; Kim, 1999). In a 2008 study, participants, who are all Americans, implicitly regarded Lucy Liu, a New York‐born star of Chinese heritage, as being less American than Kate Winslet, an English actress, even when they were informed of each actress's nationality (Devos & Ma, 2008). Moreover, Asians are continuously subject to various forms of racialization, marginalization, and civic ostracism (Lee & Kye, 2016). Viewed as being clumsy, lacking appropriate social and communication skills, and having extremely low levels of warmth and social desirability, Asian Americans are the most likely to be left out in the socialization process, rejected by peers, and least likely to be initiated friendship with (Fiske, Cuddy, Glick, & Xu, 2002; Zhang, 2010). Asians are also an easy target of racial harassment, hostility, discrimination, and violence (Chou & Feagin, 2015). In the workplace, while they may be perceived to be competent workers, they are seldom viewed as visionary leaders—confronted with an invisible barrier to career advancement called “bamboo ceiling” (Chin, 2016; Jennifer Lee & Zhou, 2020).

In effect, the racialization of Asians have long been under the influence of a pervasive Western tradition called “Orientalism,” in which the West constructs itself as a superior civilization in opposition to an “exotic” but inferior “Orient” and frames “those” Orientals as a constant threat to the well‐being of “us” Westerns (Said, 2003). Correspondingly, immigrants from Oriental countries—not matter how long they reside in the United States—are cast as inferior yet perpetual threatening foreigners to Whites (Smith, 2016).

Considered not truly “American,” Asian Americans are stereotyped as either “model minority” or “yellow peril.” The model minority trope, which began to gain traction during the 1960s, stresses Asians' high achievements in SES and focuses on Asian culture to explain their “success” (Zhou, 2004).Yet, no matter how Asian Americans are successful in upward mobility, they, at best, are model minorities (Lee & Kye, 2016). Given that the notion is culturally based, some scholars simply regard the model minority trope as a “camouflaged Orientalism” (Chou, 2008). In her influential racial triangulation theory, Kim (1999) elaborates on how Whites Americans valorize Asian Americans—for example, as “model minority”—relative to subordinate Blacks and meanwhile they construct Asians as immutably foreign and unassimilable with Whites to ostracize them from politics and civic membership; the conjunction of the two processes—relative valorization and civic ostracism, both based on cultural and/or racial groups—helps protect White privileges from both Black and Asian American encroachment and ensures the domination of Whites over the two minority groups (Kim, 1999, pp. 107, 112). The model minority myth, thus, is actually instrumental to racializing and marginalizing Asian ethnics (Ancheta, 2006). It also helps divide racial minority groups by pitting Asians and other minorities against each other and leads to discounting structural and cumulative disadvantages that other minority communities face and to denigrate other racial minorities as “problem” minorities (Kawai, 2005; Kim, 1999; Xu & Lee, 2013).

Yellow peril, by comparison, is a more negative and conspicuously racist trope—as a more direct reflection of Orientalism and with a much longer history. Here, Asians are denigrated as dishonest, diseased invaders, viewed culturally and politically inferior to Whites, and framed as a great threat to Whites (Del Visco, 2019). White Americans perceive Asians as inassimilable foreigners who “would eventually overtake the nation and wreak social and economic havoc” (Fong, 2002, p. 189). Throughout history, Asian immigrants have long been associated with disease and filth and considered a threat to Whites. Over a century ago, the press, politicians, and even public health experts portrayed Asian immigrants (including Chinese and Filipinos) as a menace to the nation's health morals, technological superiority, and the well‐being of Whites (Eichelberger, 2007; Gee & Ro, 2009).

The stereotypes of Asians often swing between yellow peril and model minority—the seemingly opposite stereotypes coexist, featuring dialectical relationships (Hurh & Kim, 1989; Kawai, 2005; Okihiro, 2014). In particular, at moments of crisis or competition, the yellow peril discourse frequently comes to the fore. When Japan was blamed for US economic difficulties in the 1980s and early 1990s, the perceived threat of this Asian country was quickly linked to Asian Americans and triggered a spike of anti‐Asian aggression in the United States (Tuan, 1998). One case in point is the brutal killing of Chinese American Vincent Chin in Detroit in 1982 by two White autoworkers who called Vincent a “Jap” (Kim, 1999). The quick association of competition with an Asian nation (Japan) to anti‐Asian violence exemplifies that Asian Americans were regarded as outsiders and potential foes to America. This conspicuous anti‐Asian racism reflects Whites’ sense of entitlement to “defend” what they assume “belongs” to them and to fight against groups who deemed a threat to Whites' privilege and well‐being.

Likewise, more recently, with the rise of China and the increasingly intensified US–China competition, the target to blame has shifted from Japan to China. A number political ads, which accuse China for stealing American manufacturing jobs or imagine a scenario in which Chinese professor and students gloat over and laugh at the downfall of the US empire (Chin, 2010; Weiner, 2012), explicitly cast China and its people as a significant threat and abominable enemy to the United States. Correspondingly, the American government has frequently suspected Chinese nationals and Chinese Americans alike as spies who steal technology from America. Senator Tom Cotton has even famously suggested that Chinese students should be banned from studying technology and science in the United States. 3 A study finds that the Department of Justice has disproportionately charging Chinese and other Asian Americans—no matter guilty or innocent—with espionage (Kim, 2018), and many charges against Chinese American scientists were later dropped without full explanation and accountability. High‐profile victims of racial profiling include Dr. Wen Ho Lee and Dr. Xiaoxing Xi. Even after prosecutors have dropped all charges, some scientists still got fired for reasons that they were originally prosecuted for, as seen in the case of hydrologist Sherry Chen (Wang, 2017). Distrust of people of Chinese heritage has long been driving decision‐making at the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and other US security agencies since the Cold War—even American‐born Chinese considered “Chinese at heart” (Bloomberg Businessweek, 2019). The readiness of security agencies to view Chinese Americans as potential spies rather than loyal American citizens can be seen as modern manifestations of the “yellow peril” trope and the continuous marginalization of Asian Americans, despite their achievements.

Therefore, both the yellow peril and model minority tropes characterize Asians' marginalized status in the United States as perpetual “outsiders” or unassimilable “others.” The deep‐seated culturally based racism renders them vulnerable to racial discrimination, aggression, and even violence, especially during times of crises.

4. OTHERING

In the face of a crisis such as public health threat, people tend to resort to “othering”—dissociating themselves from the threat and blaming others—other countries, foreigners, stigmatized groups or other minorities, which helps reduce the powerlessness experienced during the crisis (Eichelberger, 2007). Over a century ago when Irish and Jews had not become “White” in the United States, impoverished Irish immigrants were stigmatized as the bearers of cholera, whereas tuberculosis was dubbed the “Jewish disease” (Kraut, 2010). Indeed, othering can be seen in the way how diseases are named. In the 15th century, syphilis was variously referred to as “French pox” by the English, morbus Germanicus by the French, or “Chinese disease” by the Japanese (Joffe, 1999). Through othering, the outgroup and their “immoral” behavior or cultural norms—perceived as inferior to ingroup—should be to blame for the origins and spread of disease (Briggs & Mantini‐Briggs, 2003; Nelkin & Gilman, 1988). This is evident in linking Africa and African culture to the outbreak of Ebola and blaming “unhygienic” Chinese cultural habits for the emergence of severe acute respiratory syndrome (Gilles et al., 2013; Kapiriri & Ross, 2020).

Furthermore, “the other” can be depicted as villains who actively plot for a crisis and maliciously set out to disseminating diseases (Joffe, 1999). An example of the “evil‐other” conspiracy theories is the belief that the Black Death was caused by Jews who conspired with the Devil to poison Christian wells (Wagner‐Egger et al., 2011). More recently, the H1N1 outbreak was framed as a plot planned by terrorists to attack America by using Mexican immigrants as walking, talking weapons of germ warfare (McCauley, Minsky, & Viswanath, 2013).

Disease threat can not only lead to avoidance or stigmatization of outgroups, but can inspire violent xenophobic reactions (Joffe, 1999). Although foreigners and immigrants are consistently associated with germs and contagion (Faulkner, Schaller, Park, & Duncan, 2004), in the COVID‐19 pandemic, it is not only immigrants but also American citizens—Asian Americans—who suffer racist harassment and attacks. Below we flesh out how the pandemic is racialized and the othering of Asians in the United States.

5. CASE STUDY: DISCRIMINATION AGAINST ASIANS IN THE COVID‐19 PANDEMIC

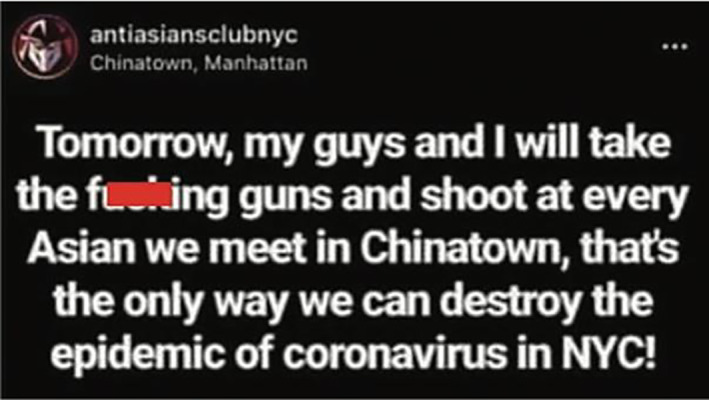

Since the COVID‐19 outbreak in Wuhan, China, in early 2020, anti‐Asian discrimination has been on the rise. Asian Americans from all walks of lives, including the presidential candidate, journalists, college professors, students, and supermarket cashiers, have become the target of racial hostility. On the front lines fighting the coronavirus, doctors and nurses of Asian ancestry have heard verbal slurs or patients refuse treatment from Asian professionals (Jan, 2020). As people have avoided Chinatowns since the outbreak, Asian businesses have also been hit hard, with many being shut down; as a result, the unemployment rate among Asians is skyrocketing (Liao, 2020). Sinophobia and hostility against Asians also surged in social media, including Twitter and 4chan (an extremist Web community; Schild et al., 2020). Figure 1 is an example of a violent threat against Asians in New York Chinatown, which appeared on Instagram.

FIGURE 1.

A threat of anti‐Asian violence on Instagram, 1 April 2020 (Zannettou et al., 2020)

In the COVID‐19 era, Asian nationals and Asian Americans alike can be victims of xenophobia and racial hatred. In March, the FBI warned of a spike in hate crimes against Asian Americans “based on their assumption that a portion of the U.S. public will associate COVID‐19 with China and Asian American populations” (Thorbecke & Zaru, 2020). Many Americans simply blame all Asians as a group for COVID‐19. This then begs the question: why does the hostility and anger against China expand to the Asian American population more broadly? This expansion, first, suggests that Asian Americans are outsiders, not Americans. Members of the dominant society perceive Asians as a threat to American society, taking valued resources and opportunities “reserved” for Americans. This outsider status also assumes that, regardless of whether they were born in the United States, Asians are loyal to other nations. Asians, in this sense, are not truly “American,” and therefore, cannot be trusted. Second, it demonstrates the visceral stereotype that all Asian Americans “look alike” or are of Chinese ancestry. Because many Americans hold this false idea, this likely adds to the belief that Asians, no matter their actual ethnic origins, are “taking away” valued resources from the “true Americans” and hold stronger ties to other countries in competition with the United States. (e.g., China).

5.1. Othering and the revival of “yellow peril” trope

The association of Asians with virus is emblematic of the “othering” practices, fitting easily with the deep‐seated “yellow peril” stereotype. Although the exact origin of the virus remains unclear, Chinese and their “unhygienic” or “immoral” eating practices are quickly under attack for its surge (Zhang, 2020, 2020, February 16). Images and videos of Chinese or other Asians eating insects, snakes, or mice, which are uncommon in China and is irrelevant to the current outbreak, frequently circulate on social media or in clickbait news stories (Palmer, 2020). Among them is a widely‐shared video showing a woman eating bat soup. Though the video did not actually take place in China, it became a convenient showcase to spout untruths about Chinese culture and the imagined origins of COVID‐19 (Barrow, 2020). Such imagination has swiftly reignited the yellow peril trope that portrays Chinese as “uncivilized, barbaric others” (Zhang, 2020, 2020, February 16). Words and actions that dehumanize Chinese people and treat their lives as less worthy consequently abound in physical and virtual worlds (Schild et al., 2020). A post on Facebook by a PhD candidate at a well‐recognized university is revealing: “There is a special place in hell reserved for the f‐‐king Chinese and their archaic culture…I wish it had wiped the whole country off the planet…China will learn nothing and will continue to consume wildlife into extinction. What a horrible, backwards culture and way of thinking” (Zannettou et al., 2020).

“Evil‐other” conspiracy theories, the variant of “othering” narratives, have also been popular since the early stages of the coronavirus outbreak. In one version, the virus is part of a Chinese “covert biological weapons program,” targeting the West including the United States (Sardarizadeh & Robinson, 2020). In Dallas, a lawyer even filed lawsuits against China for such claims (Krause, 2020). The baseless claim has also been pushed by numerous groups on Facebook and Twitter accounts. Terms such as “biowepon” (sic) and “bioattack” proliferated on 4chan′s “politically incorrect” board (a popular extremist Web community)—as a user posted, “Anyone that doesn't realize this is a Chinese bioweapon by now is either a brainlet or a chicom noodle nigger” (Schild et al., 2020). The depiction that Chinese are villains who intentionally created and spread the virus fits squarely with the yellow peril rhetoric in which Asians are framed as “devils” and “invaders” to overtake nations dominated by Whites. Although the conspiracy theories lack evidence and have been dismissed by scientists, they help fan the flames of racist hatred.

The various forms of othering and racial discrimination since the pandemic, thus, illustrate that Asians are still considered “unAmerican.”

5.2. Othering Asians by politicians and the media

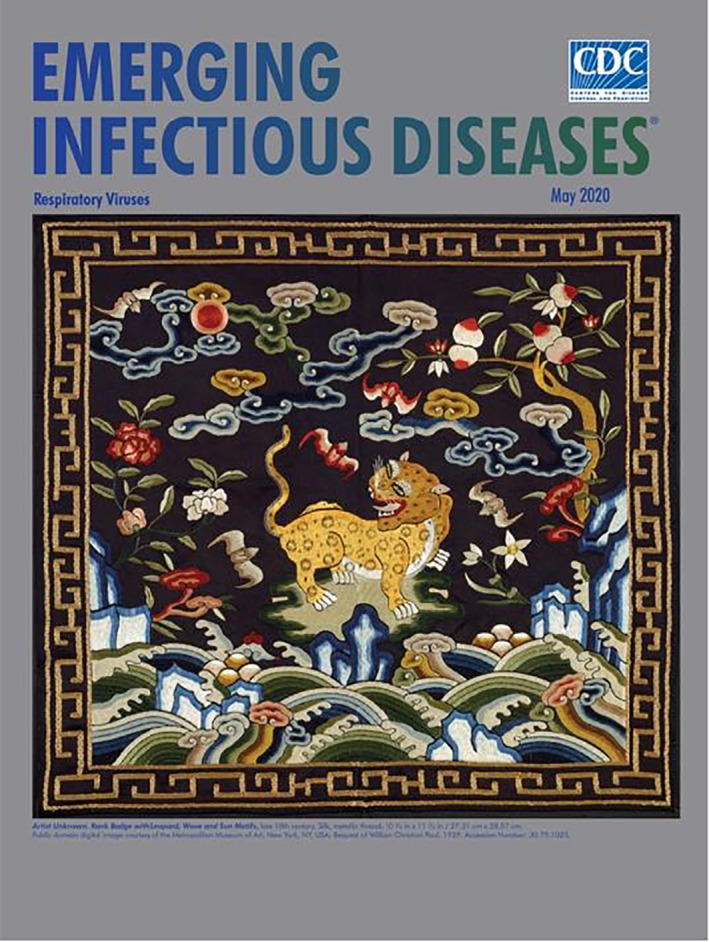

Politicians and the media played an important role in the racialization of the pandemic. Even after the World Health Organization specifically naming the disease COVID‐19 to avoid regional or ethnic stigma, political leaders, administrative officials, and media commentators have frequently referred to the ailment the “Chinese virus” or “Wuhan virus.” President Donald Trump has repeatedly and deliberately called it the “Chinese virus” (Orbey, 2020) or "kung flu” (Guardian, 2020). Secretary of State Mike Pompeo went with “Wuhan virus” (Finnegan, 2020) and claimed without evidence that the virus emerged from a Wuhan lab (Pamuk & Brunnstrom, 2020). A Republican strategy memo advised Senate candidates to justify that it is right to name it Chinese or Wuhan virus (O'Donnell Associates, 2020). Such message echoed or exacerbated the public sentiment—more than 50% of Americans said they somewhat or strongly agreed with Trump using the term “Chinese virus” (Carpenter, 2020). Although Democrats slammed Republican rhetoric as xenophobia (Muwahed, 2020), an ad released by Joe Biden's presidential campaign, which criticizes Trump's travel ban of travelers (many are American citizens) from China into America as not airtight as Trump claims, brought disapproval that it can also spur anti‐Asian bias (Myerson, 2020). Amid the surge of anti‐Asian racism, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's journal, Emerging Infectious Diseases, selected a Chinese work of art on the cover of its May issue on respiratory viruses (see Figure 2), which seems to implicitly link the pandemic with Chinese culture.

FIGURE 2.

The cover image of a CDC journal

Politicians have also echoed or spearheaded the “evil‐other” conspiracy theories. For example, Senator Tom Cotton embraced the fringe theory that the coronavirus was manmade by Chinese scientists as a biowarfare weapon (Sharma, 2020). Peter Navarro, a White House adviser, accused China of sending “hundreds of thousands of Chinese” to “seed” the coronavirus around the world (Porter, 2020). When the US authorities associated the disease with Chinese, implicitly or explicitly, they sided with the message that COVID‐19 is a Chinese problem—the other's problem. Such narrative can powerfully activate or stoke xenophobia, empowering anti‐Asian hostility from top down.

While the media have reported incidents of racial violence and harassment of Asians, its coverage and commentaries on the pandemic also contribute to anti‐Asian discrimination. Major news outlets such as the New York Times and Forbes have chosen pictures of Chinatown or Asian people in masks to accompany their news coverage of coronavirus, even when the news is irrelevant to Chinatown or China (Kamb, 2020). More explicitly, derogatory or offensive headlines such as “China is the real sick man of Asia”—an op‐ed in Wall Street Journal—were seen not only as insensitive of China's painful colonial history, but also perpetuating the stereotype that Chinese are disease‐ridden (Zhang, 2020, 2020, February 16). As for conservative media, Fox News and the Washington Times ran stories about conspiracy theories, either calling “Wuhan coronavirus” China's “coronavirus distraction campaign” or suspecting the virus' origin from a lab involved in China's “covert biological weapons programme” (Carlson, 2020; Gertz, 2020). Rush Limbaugh, a conservative radio host, claimed the coronavirus was being weaponized to bring down Trump (Sharma, 2020). The conspiracy theories and Sinophobic slurs went viral on social media, as shown in various identified combinations of Asian‐ethnic slurs decorating COVID‐19, including “chinkiepox,” “kungflu,” and “chinaids” (indicating “China” “engineered” the virus) (Schild et al., 2020; Zannettou et al., 2020). Both mass media and social media, thus, facilitates the dissemination of derogatory content, conspiracy theories, and hateful speech towards Asians.

6. CONCLUSION

No doubt, the status of Asian Americans, once described as the derisive designation “yellow horde,” has been improved dramatically in the post‐civil rights era (Gans, 2005). Today, Asian Americans are high‐ranking government officials, big corporation leaders, and elite college presidents. According to frequently used measures of assimilation, Asian Americans appear to be assimilating into the US mainstream. Nonetheless, the swift surge of anti‐Asian racism and “othering” practices during the COVID‐19 pandemic exposed the marginalized and conditional status of Asian Americans. The quick shift in labels attached to Asians from “model minority” to “yellow peril” presents a prime example of their “unAmericaness.” In this sense, this paper casts doubt on the assimilation of Asians into the American mainstream and points out limitations of current measures of assimilation. Contrary to previous studies arguing that race has become a weakening role in the assimilation of Asians, this paper augments the thesis that race is still vital and Asians are still treated as “perpetual foreigners” in the United States. Asians' improved status has not fundamentally changed their marginalization as a racial minority in the country. Additionally, the persistent racialization of Asian Americans despite their considerable gains in socioeconomic advancement and other indicators of assimilation suggests some limitations of existing measures of assimilation.

This paper also challenges the notion of the United States as a post‐racial society or the color‐blindness thesis. Typical colorblind narratives such as claims that racism is something belonging to the past (Bonvilla‐Silva, 2014; Omi & Winant, 2015) are proved to be untenable as seen in the racial hostility against Asians during the COVID‐19 outbreak. The proliferation of incidents racially targeting Asians in the pandemic clearly amplifies discrimination that Asians have been experiencing for long. In the near future, considering coronavirus not disappearing overnight, the resulting economic fallout and mass unemployment, the intensifying competition between the United States and China, and both Democratic and Republican parties competing to outflank the other in anti‐China rhetoric, harassment, and attacks against Asian Americans will probably continue to be part of the dark reality.

Finally, the pandemic and other circumstances facing Asian Americans may influence both intra and interracial group solidarity. Asian Americans of various ethnic backgrounds have faced attacks, harassment, and racial hostility due to COVID‐19. Panethnic linked fate, the feeling that what occurs to a member of one's own racial group can affect individual group members (Haynes & Skulley, 2012), is increasing among Asian ethnics due to the anti‐Asian rhetoric of the Trump Administration (Le, Arora, & Stout, 2020). Such rhetoric, coupled with shared COVID‐19 related discrimination, is fostering the emergence of grassroots movements led by Asian Americans. Such stark increases in the levels of anti‐Asian discrimination may also move Asian Americans to organize and mobilize with other communities of color. For example, during the 2020 Black Lives Matter movement reignited after police killing of George Floyd, Asian American activists joined in solidarity to combat anti‐Black discrimination within their own communities and in recognition that their “White adjacent” social position is indeed tenuous and used to diminish the plight of Blacks and Latinxs (Lang, 2020). Overall, anti‐Asian and anti‐Chinese discrimination is likely to enhance these activities, as experiences of discrimination among minority groups is often the catalyst to cross‐racial solidarity and political mobilization (Craig & Richeson, 2012).

On the other hand, a splintering may be emerging within the Asian American community among some Asian ethnics. For example, although the majority (70%) of Asian Americans support affirmative action, support among Chinese Americans is the lowest (56%) compared to other Asian ethnic subgroups (Yam, 2020). There also appears to be a growth in support of conservative political ideologies and candidates among Vietnamese Americans (Asian and Pacific Islander American Vote, 2020), primarily due to fears of Communism, Trump's “tough on China” talk, and disagreement over liberal policies (Nguyen, 2020). While the forging of ties with other marginalized racial groups and the Asian American community at large may not emerge as simply for a small subgroup of Chinese and Vietnamese Americans, it is unlikely to impede intra‐ and interracial group solidarity among most members of these groups. In order to increase feelings of solidarity across all Asian ethnics and other racial minority populations (e.g., Blacks), it is important to find ways to develop a sense of linked fate, which enhances both intra and inter‐racial solidarity among Asians, Blacks, and Latinx (Nicholson, Carter, & Restar, 2020; Sanchez & Masuoka, 2010). In this sense, to what extent the COVID‐19 pandemic can affect collective action among Asian Americans and between Asians and other minority groups remains to be seen.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors received no financial support for the research.

Biographies

Yao Li is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Sociology and Criminology and Law at the University of Florida. She holds a Ph.D. in Sociology from Johns Hopkins University. Before coming to UF, She was a postdoctoral fellow at Harvard University's Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation and was a lecturer at the University of Kansas. She is the author of Playing by the Informal Rules—Why the Chinese Regime Remains Stable Despite Rising Protests (Cambridge 2019; Cambridge Studies in Contentious Politics). Her research combines quantitative and qualitative methods to address debates in the fields of social movements, environmental studies, political sociology, and development. She is currently working on a new book project on waste management with a focus on China, Taiwan, and the United States.

Harvey L. Nicholson Jr. is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Sociology and Criminology & Law at the University of Florida. He holds a Ph.D. in Sociology from the University of Central Florida. His research focuses on racial and ethnic minority health, substance use, and racial attitudes between minority groups. His work has been published in various peer‐reviewed journals, including, but not limited to, Sociology of Race & Ethnicity, Ethnicity & Health, and Race and Social Problems.

ENDNOTES

Asians of South Asian ancestry, while included in the Asian racial category, may not be targeted by COVID‐19 related discrimination for these reasons.

We recognize diversity within Asian Americans. Different Asian groups differ in socioeconomic and educational achievements, among other things (Lee & Kye, 2016; Sakamoto et al., 2009). Certain segments of Asians such as Filipinos are considered as part of “collective blacks,” whereas Eastern Asians such as Chinese are regarded as “Honorary Whites” (Bonilla‐Silva, 2004).

REFERENCES

- Alba, R. , & Nee, V. (2003). Remaking the American mainstream: Assimilation and contemporary America. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ancheta, A. N. (2006). Race, rights, and the Asian American experience. Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barrow, H. (2020). The West’s double standards are on full display as it racialises the coronavirus pandemic. Euronews. Retrieved from https://www.euronews.com/2020/04/09/the-west-s-double-standards-are-on-full-display-racialises-the-coronavirus-pandemic-view [Google Scholar]

- Bloomberg Businessweek . (2019, December). Mistrust and the hunt for spies among Chinese Americans. Retrieved from https://www.bloombergquint.com/businessweek/the-u-s-government-s-mistrust-of-chinese-americans [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla‐Silva, E. (2004). From bi‐racial to tri‐racial: Towards a new system of racial stratification in the USA. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 27(6), 931–950. 10.1080/0141987042000268530 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bonvilla‐Silva, E. (2014). Racism without racists: Colour‐blind racism and the persistence of racial inequality in America (4th ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Borja, M. , Jeung, R. , Gibson, J. , Gowing, S. , Lin, N. , Navins, A. , & Power, E. (2020). Anti‐Chinese rhetoric tied to racism against Asian Americans stop AAPI hate report. Asian Pacific Policy & Planning Council. [Google Scholar]

- Briggs, C. L. , & Mantini‐Briggs, C. (2003). Stories in the time of cholera: Racial profiling during a medical nightmare. University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, T. (2020, April). Tucker Carlson: China is waging coronavirus distraction campaign. Fox News. Retrieved from https://www.foxnews.com/opinion/tucker-carlson-china-coronavirus-origin [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter, T. G. (2020, April). Beijing’s coronavirus blunder empowers anti‐China hawks. The Hill. Retrieved from https://thehill.com/blogs/congress-blog/politics/493424-beijings-coronavirus-blunder-empowers-anti-china-hawks [Google Scholar]

- Chin, J. (2010). Fear mongering 101: Anti‐China campaign ads. Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/BL-CJB-11316 [Google Scholar]

- Chin, M. M. (2016). Asian Americans, bamboo ceilings, and affirmative action. Contexts, 15(1), 70–73. [Google Scholar]

- Chou, C.‐C. (2008). Critique on the notion of model minority: An alternative racism to Asian American? Asian Ethnicity, 9(3), 219–229. [Google Scholar]

- Chou, R. S. , & Feagin, J. R. (2015). Myth of the model minority: Asian Americans facing racism. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, M. A. , & Richeson, J. A. (2012). Coalition or derogation? How perceived discrimination influences intraminority intergroup relations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102(4), 759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Visco, S. (2019). Yellow peril, red scare: Race and communism in National Review. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 42(4), 626–644. 10.1080/01419870.2017.1409900 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Devos, T. , & Ma, D. S. (2008). Is Kate Winslet more American than Lucy Liu? The impact of construal processes on the implicit ascription of a national identity. British Journal of Social Psychology, 47(2), 191–215. 10.1348/014466607X224521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhingra, P. H. (2003). Being American between Black and White: Second‐generation Asian American professionals’ racial identities. Journal of Asian American Studies, 6(2), 117–147. [Google Scholar]

- Drouhot, L. G. , & Nee, V. (2019). Assimilation and the second generation in Europe and America: Blending and segregating social dynamics between immigrants and natives. Annual Review of Sociology, 45(1), 177–199. 10.1146/annurev-soc-073117-041335 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eichelberger, L. (2007). SARS and New York’s Chinatown: The politics of risk and blame during an epidemic of fear. Social Science & Medicine, 65(6), 1284–1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellerbeck, A. (2020, April). Over 30 percent of Americans have witnessed COVID‐19 bias against Asians, poll says. NBC News. Retrieved from https://www.nbcnews.com/news/asian-america/over-30-americans-have-witnessed-covid-19-bias-against-asians-n1193901 [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner, J. , Schaller, M. , Park, J. H. , & Duncan, L. A. (2004). Evolved disease‐avoidance mechanisms and contemporary xenophobic attitudes. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 7(4), 333–353. 10.1177/1368430204046142 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Finnegan, C. (2020, March). Pompeo pushes “Wuhan virus” label to counter Chinese disinformation. Retrieved from https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/pompeo-pushes-wuhan-virus-label-counter-chinese-disinformation/story?id=69797101 [Google Scholar]

- Fiske, S. T. , Cuddy, A. J. , Glick, P. , & Xu, J. (2002). A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: Competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(6), 878–902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong, T. P. (2002). The contemporary Asian American experience: Beyond the model minority. Pearson College Division. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher, C. A. (2004). Racial redistricting: Expanding the boundaries of Whiteness. In Dalmage H. M. (Eds.), The politics of multiracialism: Challenging racial thinking (pp. 59–76). State University of New York Press Albany. [Google Scholar]

- Gans, H. J. (2005). Race as class. Contexts, 4(4), 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Gans, H. J. (2012). “Whitening” and the changing American racial hierarchy, New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gee, G. C. , & Ro, A. (2009). Racism and discrimination. In Chau Trinh‐Shevrin, Nadia Shilpi Islam, & Mariano Jose Rey (Eds.), Asian American communities and health: Context, research, policy, and action (pp. 364–402). Jossey‐Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Gertz, B. (2020, January). Coronavirus may have originated in lab linked to China’s biowarfare program. Retrieved from https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2020/jan/26/coronavirus-link-to-china-biowarfare-program-possi/ [Google Scholar]

- Gilles, I. , Bangerter, A. , Clémence, A. , Green, E. G. T. , Krings, F. , Mouton, A. , … Wagner‐Egger, P. (2013). Collective symbolic coping with disease threat and othering: A case study of avian influenza. British Journal of Social Psychology, 52(1), 83–102. 10.1111/j.2044-8309.2011.02048.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guardian (2020, June). Donald Trump calls Covid‐19 “kung flu” at Tulsa rally. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/jun/20/trump-covid-19-kung-flu-racist-language [Google Scholar]

- Haynes, C. , & Skulley, C. (2012). Linked fate and the inter‐ethnic differences among Asian Americans. Portland, Oregon: Annual Meeting of the Western Political Science Association. [Google Scholar]

- Hurh, W. M. , & Kim, K. C. (1989). The ‘success’ image of Asian Americans: Its validity, and its practical and theoretical implications. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 12(4), 512–538. [Google Scholar]

- Jan, T. (2020). Asian American doctors and nurses are fighting racism and the coronavirus. Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2020/05/19/asian-american-discrimination/?fbclid=IwAR0oTAHU_aoLxI7KVdwwYKnzBp6vvzE51Stmb8dj_Zd5P0cAEuPohUA-C9U [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez, T. R. , & Horowitz, A. L. (2013). When White is just alright: How immigrants redefine achievement and reconfigure the ethnoracial hierarchy. American Sociological Review, 78(5), 849–871. [Google Scholar]

- Joffe, H. (1999). Risk and “the other”. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kamb, A. (2020). Coronavirus & bias: Media responsibility in a time of crisis. Columbia Public Health. Retrieved from https://www.publichealth.columbia.edu/public-health-now/news/coronavirus-bias-media-responsibility-time-crisis [Google Scholar]

- Kapiriri, L. , & Ross, A. (2020). The politics of disease epidemics: A comparative analysis of the SARS, Zika, and Ebola outbreaks. Global Social Welfare, 7(1), 33–45. 10.1007/s40609-018-0123-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai, Y. (2005). Stereotyping Asian Americans: The dialectic of the model minority and the yellow peril. Howard Journal of Communications, 16(2), 109–130. 10.1080/10646170590948974 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, A. C. (2018). Prosecuting “Chinese Spies”: Empirical analysis of economic espionage. Cardozo Law Review, 40(2). Retrieved from http://cardozolawreview.com/prosecuting-chinese-spies-an-empirical-analysis-of-the-economic-espionage-act/ [Google Scholar]

- Kim, C. J. (1999). The racial triangulation of Asian Americans. Politics & Society, 27(1), 105–138. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, N. Y. (2007). Critical thoughts on Asian American assimilation in the whitening literature. [Google Scholar]

- Krause, K. (2020). Lawsuit in Dallas federal court accuses Chinese government of creating coronavirus as ‘biological weapon. Dallas Morning News. Retrieved from https://www.dallasnews.com/news/public-health/2020/03/18/dallas-federal-lawsuit-accuses-chinese-government-of-creating-coronavirus-as-biological-weapon/ [Google Scholar]

- Kraut, A. M. (2010). Immigration, ethnicity, and the pandemic. Public Health Reports, 125, 123–133. 10.1177/00333549101250S315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang, C. (2020, June 26). Asian Americans’ response to black lives matter is part of a complicated history. Time. Retrieved from https://time.com/5851792/asian-americans-black-solidarity-history/ [Google Scholar]

- Le, D. , Arora, M. , & Stout, C. (2020). Are you threatening me? Asian‐American panethnicity in the Trump era. Social Science Quarterly.101(6), 2183–2192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J. , & Bean, F. D. (2007). Reinventing the color line immigration and America’s new racial/ethnic divide. Social Forces, 86(2), 561–586. 10.1093/sf/86.2.561 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J. C. , & Kye, S. (2016). Racialized assimilation of Asian Americans. Annual Review of Sociology, 42(1), 253–273. 10.1146/annurev-soc-081715-074310 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J. , & Bean, F. D. (2010). The diversity paradox: Immigration and the color line in twenty‐first century America. Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J. , & Zhou, M. (2020). The reigning misperception about culture and Asian American achievement. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 43(3), 508–515. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, S. (2020, May). Unemployment claims from Asian Americans have spiked 6,900% in New York. Here’s why. CNN Business. Retrieved from https://www.cnn.com/2020/05/01/economy/unemployment-benefits-new-york-asian-americans/index.html [Google Scholar]

- McCauley, M. , Minsky, S. , & Viswanath, K. (2013). The H1N1 pandemic: Media frames, stigmatization and coping. BMC Public Health, 13(1). 10.1186/1471-2458-13-1116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melendez, P. (2020, March 31). Stabbing of Asian‐American 2‐year‐old and her family was a virus‐fueled hate crime: Feds. Daily Beast. Retrieved from https://www.thedailybeast.com/stabbing-of-asian-american-2-year-old-and-her-family-was-a-coronavirus-fueled-hate-crime-feds-say [Google Scholar]

- Muwahed, J. (2020, March). Democrats demand apology after McCarthy tweets about “Chinese coronavirus”.ABC News. Retrieved from https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/democrats-demand-apology-mccarthy-tweets-chinese-coronavirus/story?id=69513372 [Google Scholar]

- Myerson, J. A. (2020, April 22). An anti‐China message didn’t work for democrats in 2018—and it won’t work for Biden now. The intercept. Retrieved from https://theintercept.com/2020/04/22/biden-china-campaign-ad-trump/ [Google Scholar]

- Nee, V. , & Holbrow, H. (2013). Why Asian Americans are becoming mainstream. Dædalus, 142(3), 65–75. 10.1162/DAED_a_00219 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nelkin, D. , & Gilman, S. L. (1988). Placing blame for devastating disease. Social Research, 361–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson Jr, H. L. , Carter, J. S. , & Restar, A. (2020). Strength in numbers: Perceptions of political commonality with African Americans among Asians and Asian Americans in the United States. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity, 6(1), 107–122. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T. (2020, October 30). 4. 8% of Vietnamese Americans say they’re voting for Trump. Here’s why. Retrieved from https://www.vox.com/first-person/2020/10/30/21540263/vietnamese-american-support-trump-2020 [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell Associates . (2020). Corona big book. O’Donnell Associates. Retrieved from O’Donnell Associates website: https://static.politico.com/80/54/2f3219384e01833b0a0ddf95181c/corona-virus-big-book-4.17.20.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Okihiro, G. Y. (2014). Margins and mainstreams: Asians in American history and culture. University of Washington Press. [Google Scholar]

- Omi, M. , & Winant, H. (2015). Racial formation in the United States. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Orbey, E. (2020, March). Trump’s “Chinese virus” and what’s at stake in the coronavirus’s name. The New Yorker. Retrieved from https://www.newyorker.com/culture/cultural-comment/whats-at-stake-in-a-viruss-name [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, J. (2020). Don’t blame bat soup for the coronavirus. Foreign policy. Retrieved from https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/01/27/coronavirus-covid19-dont-blame-bat-soup-for-the-virus/ [Google Scholar]

- Pamuk, H. , & Brunnstrom, D. (2020). Pompeo blames China for hundreds of thousands of virus deaths, denies inconsistency. Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-china-pompeo-idUSKBN22I27K [Google Scholar]

- Porter, T. (2020, May 18). Trump official Navarro accuses China of plot to “seed” coronavirus. Business Insider. Retrieved from https://www.businessinsider.com/trump-official-navarro-accuses-china-of-plot-to-seed-coronavirus-2020-5 [Google Scholar]

- Said, E. W. (2003). Orientalism. Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto, A. , Goyette, K. A. , & Kim, C. (2009). Socioeconomic Attainments of Asian Americans. Annual Review of Sociology, 35(1), 255–276. 10.1146/annurev-soc-070308-115958 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez, G. R. , & Masuoka, N. (2010). Brown‐utility heuristic? The presence and contributing factors of Latino linked fate. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 32(4), 519–531. [Google Scholar]

- Sardarizadeh, S. , & Robinson, O. (2020). China and the US trade coronavirus conspiracy theories. BBC. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-52224331 [Google Scholar]

- Schild, L. , Ling, C. , Blackburn, J. , Stringhini, G. , Zhang, Y. , & Zannettou, S. (2020). “Go eat a bat, Chang!”: An early look on the emergence of sinophobic behavior on Web communities in the face of COVID‐19. Retrieved from http://arxiv.org/abs/2004.04046 [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, G. (2020, March 5). Why are there so many conspiracy theories around the coronavirus? China News Al Jazeera. Retrieved from https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/03/conspiracy-theories-coronavirus-200303170729373.html [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A. (2016). Heeropatriarchy and the three pillars of white supremacy: Rethinking women of color organizing. In Dickinson T. D. & Schaeffer R. K. (Eds.), Transformations: Feminist pathways to global change (2nd ed., pp. 264–272). Paradigm Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Song, M. (2019). Is there evidence of ‘Whitening’ for Asian/White multiracial people in Britain? Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 1–17. 10.1080/1369183X.2019.1654163 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tessler, H. , Choi, M. , & Kao, G. (2020). The anxiety of being Asian American: Hate crimes and negative biases during the COVID‐19 pandemic. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 45, 636–646. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s12103-020-09541-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorbecke, C. , & Zaru, D. (2020, May). Asian Americans face coronavirus “Double Whammy”: Skyrocketing unemployment and discrimination. ABC News. Retrieved from https://abcnews.go.com/Business/asian-americans-face-coronavirus-double-whammy-skyrocketing-unemployment/story?id=70654426 [Google Scholar]

- Tuan, M. (1998). Forever foreigners or honorary Whites? The Asian ethnic experience today. Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner‐Egger, P. , Bangerter, A. , Gilles, I. , Green, E. , Rigaud, D. , Krings, F. , … Clémence, A. (2011). Lay perceptions of collectives at the outbreak of the H1N1 epidemic: Heroes, villains and victims. Public Understanding of Science, 20(4), 461–476. 10.1177/0963662510393605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F. K.‐H. (2017, March). Government scientist fired after dropped spying charges petitions for reinstatement. NBC News. Retrieved from https://www.nbcnews.com/news/asian-america/government-scientist-fired-after-dropped-spying-charges-petitions-reinstatement-n733281 [Google Scholar]

- Warren, J. W. , & Twine, F. W. (1997). White Americans, the new minority? Non‐Blacks and the ever‐expanding boundaries of whiteness. Journal of Black Studies, 28(2), 200–218. [Google Scholar]

- Waters, M. C. , & Jiménez, T. R. (2005). Assessing immigrant assimilation: New empirical and theoretical challenges. Annual Review of Sociology, 31(1), 105–125. 10.1146/annurev.soc.29.010202.100026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner, R. (2012, February 6). Pete Hoekstra’s China ad provokes accusations of racism. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/the-fix/post/pete-hoekstras-china-ad-provokes-accusations-of-racism/2012/02/06/gIQAPD6buQ_blog.html [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J. , & Lee, J. C. (2013). The marginalized “Model” minority: An empirical examination of the racial triangulation of Asian Americans. Social Forces, 91(4), 1363–1397. 10.1093/sf/sot049 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yam, K. (2020, November 14). 70% of Asian Americans support affirmative action. Here’s why misconceptions persist. NBC News. Retrieved from https://www.nbcnews.com/news/asian-america/70-asian-americans-support-affirmative-action-here-s-why-misconceptions-n1247806?icid=recommended [Google Scholar]

- Yang, A. (2020). Andrew Yang: We Asian Americans are not the virus, but we can be part of the cure The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2020/04/01/andrew-yang-coronavirus-discrimination/ [Google Scholar]

- Zannettou, S. , Baumgartner, J. , Finkelstein, J. , Goldenberg, A. , Farmer, J. , Donohue, J. K. , & Goldenberg, P. (2020). Weaponized information outbreak: A case study on COVID‐19, bioweapon myths, and the Asian conspiracy meme. Network Contagion Research Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J. G. (2020). Pinning coronavirus on how Chinese people eat plays into racist assumptions. Eater. Retrieved from https://www.eater.com/2020/1/31/21117076/coronavirus-incites-racism-against-chinese-people-and-their-diets-wuhan-market [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L. (2020, February 16). Coronavirus triggers an ugly rash of racism as the old ideas of ‘Yellow Peril’ and ‘sick man of Asia’ return. South China Morning Post. Retrieved from https://www.scmp.com/comment/opinion/article/3050542/coronavirus-triggers-ugly-rash-racism-old-ideas-yellow-peril-and [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q. (2010). Asian Americans beyond the model minority stereotype: The nerdy and the left out. Journal of International and Intercultural Communication, 3(1), 20–37. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X. , & Biernat, M. (2018). “I Have two names, Xian and Alex”: Psychological correlates of adopting Anglo names. Journal of Cross‐Cultural Psychology, 49(4), 587–601. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, M. (2004). Are Asian Americans becoming “White? Contexts, 3(1), 29–37. 10.1525/ctx.2004.3.1.29 [DOI] [Google Scholar]